Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 4, 2025, 435-443Original Article

FORMULATION OF ANTI-DIABETIC ULCER GEL ENRICHED WITH ALOE VERA EXTRACT AND FISH COLLAGEN: AN IN VIVO STUDY

JULIA REVENY1, SONY EKA NUGRAHA2*, ADIRA KAMILIA3, NURATIKA3

1Department of Pharmaceutical Technology, Faculty of Pharmacy, Universitas Sumatera Utara, Medan, Indonesia. 2Department of Pharmaceutical Biology, Faculty of Pharmacy, Universitas Sumatera Utara, Medan, Indonesia. 3Undergratuate Program, Faculty of Pharmacy, Universitas Sumatera Utara, Medan, Indonesia

*Corresponding author: Sony Eka Nugraha; *Email: sonyekanugraha@usu.ac.id

Received: 16 Apr 2024, Revised and Accepted: 23 Apr 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: Diabetic ulcers are a common complication of diabetes mellitus, with a significantly increased risk of infection, delayed healing, and potential limb amputation. This study aimed to develop and evaluate a novel anti-diabetic ulcer gel containing Aloe vera extract and fish collagen, focusing on its formulation, stability, and wound healing efficacy in a diabetic rat model.

Methods: Aloe vera extract and fish collagen were extracted and characterized using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) for collagen verification and antioxidant testing for Aloe vera. Three different gel formulations (F1, F2, F3) were prepared and assessed for homogeneity, pH, viscosity, and stability over 12 w at varying temperatures. The in vivo study was conducted using streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rats to evaluate wound healing efficacy, with wound size reduction, histopathological analysis (fibroblast proliferation and collagen density), and statistical comparisons performed using Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with GraphPad Prism 9.

Results: Aloe vera extract demonstrated strong antioxidant properties, with an half-maximal inhibitory concentration IC50 value of 39.976 μg/ml. Fish collagen met standard collagen characteristics based on FTIR analysis, confirming its structural integrity. The gel formulations remained stable over 12 w, maintaining homogeneity, pH, and viscosity within acceptable ranges. In vivo experiments showed that rats treated with Formula F2 (Group 4) exhibited the highest wound healing rate, achieving 100% wound closure by day 12. Fibroblast proliferation and collagen deposition were significantly higher in the F2-treated group compared to control groups (p<0.05). Histopathological analysis confirmed enhanced tissue regeneration and reduced inflammation, demonstrating the gel’s effectiveness in accelerating diabetic wound healing.

Conclusion: The combination of Aloe vera and fish collagen in a gel formulation effectively accelerates diabetic wound healing, demonstrating antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and tissue-regenerative properties.

Keywords: Aloe vera, Collagen, Diabetic, Gels, Ulcer, Wound

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i4.51149 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Diabetic ulcers, particularly foot ulcers, are a common and serious complication of diabetes. They occur due to a combination of factors such as poor circulation, neuropathy, and high blood sugar levels, which can impair the body's ability to heal and fight infections [1]. The prevalence of diabetic ulcers is significant, affecting approximately 15% of individuals with diabetes at some point in their lives. The impact of diabetic ulcers is profound both on individual health and healthcare systems [2]. These ulcers can lead to severe infections, hospitalizations, and in severe cases, amputations. The risk of amputation is notably higher in diabetic individuals with foot ulcers compared to those without ulcers [3]. The healing process for these ulcers is often prolonged and complicated, requiring comprehensive wound care and often intervention to manage blood sugar levels and improve circulation [4]. The need for effective treatments is critical due to the high risk of complications, including infections that are resistant to antibiotics, and the potential for significant morbidity. Effective treatment strategies typically involve a multidisciplinary approach, including regular wound care, control of infection, optimization of blood glucose levels, and measures to reduce pressure on the affected area. Innovations in treatment, such as advanced wound dressing materials, growth factor therapies, and stem cell treatments, are also being explored to improve healing outcomes. Given the increasing prevalence of diabetes globally, the burden of diabetic ulcers is likely to rise, underscoring the necessity for effective prevention strategies, early detection, and improved treatment modalities.

Aloe vera, known for its medicinal properties, plays a significant role in wound healing. Its effectiveness in promoting wound healing is well-documented, making it a favored addition to wound dressings [5]. Aloe vera contains complex constituents and exhibits various pharmacological activities beneficial for skin regeneration [6]. It has been historically used for its therapeutic properties in skin injuries, providing both physical and mental health benefits. The addition of Aloe vera in wound dressings and skin care products is informed by its ability to enhance the healing process of skin injuries.

A study examining the influence of Aloe vera on collagen in dermal wounds found that Aloe vera increases the collagen content in the granulation tissue, which is crucial for wound healing [7]. This increase also enhances the crosslinking of collagen, indicated by a rise in aldehyde content and a decrease in acid solubility [8]. Moreover, the study observed a lower type I/type III collagen ratio in Aloe vera-treated groups compared to untreated controls, suggesting a boost in type III collagen levels [9]. These effects were consistent whether Aloe vera was applied topically or administered orally, underscoring its efficacy in improving wound healing through its impact on collagen.

Collagen, as a key component of the extracellular matrix, plays an essential role in wound healing [10]. It is involved in various phases of the healing process, including the inflammatory, proliferative, and remodeling phases. Collagen's presence in its native, fibrillar form, or as soluble components, significantly influences the healing process [11]. Chronic, non-healing wounds often suffer from impairments in these phases, and collagen is central to regulating several processes within wound healing [12]. Its significance in various biological processes relevant to wound healing makes it a valuable component in wound therapy, with numerous studies and literature reviews highlighting its critical role. Moreover, the combination of Aloe vera and collagen in gel formulations for wound healing leverages the unique properties of both components. Aloe vera enhances the healing process and positively influences collagen characteristics, while collagen plays a crucial role in regulating the healing phases. This synergy makes their combination highly effective for therapeutic applications in wound care.

The primary objective of this study is to develop and evaluate the synergistic effects of Aloe vera and fish collagen in a novel gel formulation for diabetic ulcer treatment. While Aloe vera is well known for its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, and fish collagen provides structural and regenerative support, their combined effects on diabetic wound healing remain largely unexplored. This study integrates phytochemical screening, FTIR analysis for collagen characterization, and long-term stability testing, ensuring both biological effectiveness and pharmaceutical feasibility. Unlike previous studies that focus solely on Aloe vera or collagen individually, this research systematically examines the interaction of both components in a controlled STZ-induced diabetic rat model, assessing wound healing progression, fibroblast proliferation, and collagen density. Additionally, the gel formulation undergoes extensive stability evaluation over 12 w, which is a crucial step for clinical translation. By bridging biological efficacy with formulation stability, this study introduces a promising bio-based wound treatment for diabetic patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tools and materials

The study implemented a variety of standard laboratory instruments, such as thermal shoves, blenders, laboratory glassware, hot plates, drying cabinets, and individually housed enclosures for each mouse, which were supported by drinking bottles. Knives, mortars and pestles, analytical balances, pH meters, rotary evaporators, stopwatches, UV-Visible spectrophotometers, vortex mixers, Brookfield viscometers, miscellaneous glassware, water baths, needle-nose forceps, autoclaves, glucometers, and scissors were among the additional equipment. Aloe vera and catfish epidermis were the biological materials employed. The chemical reagents comprised distilled water, ethanol (pharmaceutical grade), hematoxylin-eosin stain, methanol (pharmaceutical grade), Hydroxypropyl Methylcellulose (HPMC), pH buffer solutions of pH 4 and neutral pH 7, methyl paraben, propylene glycol, propyl paraben, sodium phosphate, sodium carbonate, chlorine acid, Bouchardat's reagent, Dragendorff's reagent, Mayer's reagent, lead(II) acetate, chloroform, isopropanol, Molisch's reagent, concentrated sulfuric acid, magnesium powder, amyl alcohol, iron(III) chloride reagents, n-hexane, acetic anhydride, Folin-Ciocalteu's reagent, sodium bicarbonate, sodium nitrite, and sodium hydroxide.

Preparation Aloe vera extract

The extraction of Aloe vera commences with thorough cleansing of the plant material under running water. Subsequently, the Aloe vera is segmented into smaller sections and the exudate is segregated. The resultant exudate is subjected to centrifugation, post which the supernatant is carefully extracted. This supernatant is then treated with activated charcoal in a proportion corresponding to 10 percent of the supernatant's weight. Following this, a vacuum filtration is conducted employing Whatman no. 4 filter paper. The final product, the Aloe vera gel extract, is then augmented with 0.5% ascorbic acid and 1% citric acid to enhance stability and prevent oxidation [13].

Extraction collagen from catfish (Pangasianodon hypophthalmus) skin

The catfish skin was meticulously cleaned to remove any adherent debris and then sectioned into smaller fragments. The removal of non-collagen proteins was accomplished by immersing the cut samples in a 0.3 M NaOH solution for 24 h. The ratio of catfish skin to the solution volume was maintained at 1:10 (w/v). Following this treatment, the catfish skin was thoroughly rinsed with distilled water until the pH of the samples was neutralized to a pH of 7. Subsequent hydrolysis was performed using a 0.1% acetic acid (CH3COOH) solution, at a ratio of 1:10 (w/v), and the skin was left to react for 48 h. Post-acetic acid immersion, the skin was again washed with running water until a neutral pH was achieved. The final extraction step involved treating the sample with distilled water at a 1:2 (w/v) ratio for 2 h at a controlled temperature of 45 °C to prevent the degradation of collagen into gelatin. The collagen extract obtained was then dried in an oven set at 50 °C for a period of 48 h [14]. Moreover, the obtained collagen was characterized using FTIR.

Screening phytochemicals extract and determination total phenols and flavonoids

The analytical evaluation of the Aloe vera extract entailed the qualitative detection of secondary metabolites, including alkaloids, flavonoids, glycosides, tannins, saponins, and terpenoids/steroids [15]. Subsequent quantitative analyses were conducted to ascertain the phenolic and flavonoid content, utilizing standardized methodologies [16, 17].

Preparation formula composition and evaluation preparation

Aloe vera gel preparation combination collagen made in 3 formulas with concentration different extracts. The composition of the gel preparation formula can be seen in table 1.

Table 1: Formula composition of aloe vera gel and collagen preparations

| Gel preparation formula composition (%w/w) | Formula 1 (%) | Formula 2 (%) | Formula 3 (%) |

| Extract Aloe vera | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Collagen | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| HPMC | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Propylene glycol | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| Methyl paraben | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0.075 |

| Propyl paraben | 0.025 | 0.025 | 0.025 |

| Distilled water | ad 100 | ad 100 | ad 100 |

The gel formulation was prepared by incorporating the extract and fish collagen into individual mortars, using three selected concentrations. Each mixture was gradually added to a gel base until the total weight reached 100 g, followed by trituration until a homogenous gel was obtained. The physical evaluation of the gel included organoleptic assessment, homogeneity, pH, and viscosity measurements. These evaluations were conducted over a 12 w storage period and subjected to a cycling test. The gel was considered stable if no significant changes were observed in these parameters from the first week through the fourth week of storage [18].

Testing gel preparations against wound healing in diabetic rats

The experimental animals, male Wistar rats (Rattus norvegicus), 150-180 g, were procured from the Animal Research Center at Universitas Sumatera Utara. The study received ethical approval from the Animal Research Ethics Committees (AREC) of Universitas Sumatera Utara, with the assigned approval number 0505/KEPH-FMIPA/2023. Furthermore, all animals were acclimated for one week before the experiments in a controlled environment with a temperature of 22±2 °C, relative humidity of 50–60%, and a 12 h light/dark cycle. They were provided with standard laboratory chow and water ad libitum.

Diabetes was induced in rats using intraperitoneal injection of streptozotocin (STZ) at a dose of 60 mg/kg body weight, following pre-treatment with nicotinamide (110 mg/kg body weight) to partially protect pancreatic beta cells. After three days, fasting blood glucose levels were measured, and rats with blood glucose levels exceeding 200 mg/dL were considered diabetic. The study investigates an open wound model in diabetic rats to evaluate the wound healing efficacy of Aloe vera and fish collagen gel. A total of 25 male diabetic rats were randomly divided into five groups (n=5 per group):

G1: Negative control group of diabetic mice (without gel administration).

G2: Normal group (healthy mice without diabetes, no gel administration).

G3: Diabetic rat group treated with F1 gel formulation.

G4: Diabetic rat group treated with F2 gel formulation.

G5: Diabetic rat group treated with F3 gel formulation.

Prior to treatment, all rats underwent streptozotocin (STZ) induction to develop diabetes [19]. A full-thickness wound (~2 cm in diameter) was created on the dorsal skin [20], and treatments were applied once daily for 14 days. Wound healing was monitored daily, and the wound area was analyzed using ImageJ software to determine the percentage of wound closure. Statistical comparisons were performed using ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test to assess significant differences among groups. Moreover, the percentage of wound healing was determined using the following formula:

Percentage healing injuries (%) = x 100%

x 100%

Note:

I0 = area in days beginning treatment

Ix = area in days observation

Histopathological observation

Histological examination was conducted following standard hematoxylin and eosin (H and E) staining protocols. Skin and underlying tissues were fixed and subjected to a graded dehydration process using alcohol concentrations of 70%, 80%, 90%, followed by two absolute alcohol steps (Alcohol Absolute I and II). The tissues were then cleared in two xylene solutions (Xylol I and II). The paraffinization process involved infiltration with Paraffin I and II. Following embedding, tissue sections were stained using hematoxylin and eosin solutions for microscopic examination. Observations included the density of collagen fibers and the thickness of the epidermis. These parameters were examined under a microscope at 400x magnification, with ImageJ software facilitating the quantitative interpretation of data [21].

Statistic analysis

All experimental data were statistically analyzed using GraphPad Prism 9. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was conducted to determine significant differences among treatment groups. Data are expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD). A p-value of less than 0.05 (p<0.05) was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Phytochemical screening of Aloe vera extract

Phytochemical analysis of both fresh Aloe vera and its extract was performed to determine the presence of various bioactive compounds. The results in table 2 indicated that flavonoids, alkaloids (with the exception of a negative result for Bouchardat's reagent), saponins, tannins, and steroids or terpenoids were present in both forms. The absence of reactivity with Bouchardat's reagent suggests the absence of certain alkaloid subclasses in the samples. Notably, these findings demonstrate the retention of significant phytochemical constituents in Aloe vera when comparing its fresh and extracted states.

Antioxidant Aloe vera extract

The IC50 value is an important parameter in determining the efficacy of an antioxidant. A lower IC50 value indicates less need for a substance to inhibit the oxidation process by 50%, which means higher efficacy. Table 3 shows the IC50 value of antioxidant activity of Aloe vera extract is 39.976 μg/ml, which indicates the amount of extract required to inhibit 50% of free radicals.

Table 2: Phytochemical screening test results

| No. | Compound | Reagent | Fresh samples | Extract |

| 1 | flavonoids | HCL(c), Mg powder. amyl alcohol | + | + |

| 2 | alkaloids | Mayer | + | + |

| Bouchardat | - | - | ||

| Dragendorf | + | + | ||

| 3 | saponins | Foam Test | + | + |

| 4 | tannins | FeCl 3 | + | + |

| 6 | steroids/terpenoids | Liberman Burchard | + | + |

Information:+(Present);-(Absence).

Table 3: IC 50 Antioxidant activity of Aloe vera extract

| No | Concentration (µg/ml) | Absorbance | % Inhibition | Regression equation | IC50 (µg/ml) |

| 1 | Blank | 0.9967 | 0 | y = 0.8152x+19.374 r² = 0.9584 |

39.976 |

| 2 | 6.25 | 0.8642 | 18.77529 | ||

| 3 | 12.5 | 0.7521 | 25.86492 | ||

| 4 | 25 | 0.5301 | 48.98527 | ||

| 5 | 50 | 0.2984 | 71.97528 | ||

| 6 | 100 | 0.0523 | 95.69785 |

Other studies on Aloe vera show variability in antioxidant activity depending on the extraction method and part of the plant used. One study showed that Aloe vera byproduct (bark) contained significant phytochemicals and antioxidants, and oven-dried samples showed the highest contents [22]. Other research states that methanol extract from the base of Aloe vera leaves shows high antioxidant activity with an IC50 value of 0.65 mg/ml for 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) and 0.052 mg/ml for 2,2'-Azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid (ABTS) [22].

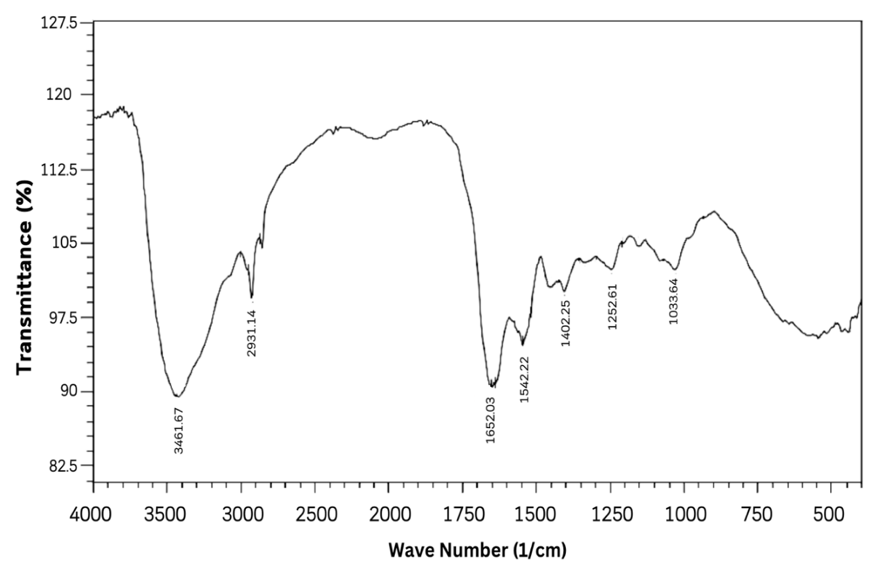

Analysis of catfish skin collagen function groups

Functional Group Analysis with FTIR Functional Group Analysis with FTIR was carried out [23]. FTIR analysis was used to determine the typical functional groups of collagen. FTIR analysis was carried out by weighing 100 mg KBr and 2 mg test sample mixed, then ground until smooth and mixed evenly in an agate mortar. Test sample measurements were carried out at wave numbers between 4000-500 cm-1. The resulting FTIR spectrum in fig. 1 and table 4 shows the wave number absorption peaks of the test sample. The functional group of the test sample is determined based on the wave number absorption peak detected with the absorption region for the protein functional group.

Fig. 1: FTIR spectrum of catfish collagen, The FTIR spectrum of catfish skin collagen has typical absorption peaks in the amide region, namely amide A, amide B, amide I, amide II, amide III

Table 4: Characteristics of collagen functional groups

| Amide group | Peak absorbance (wave number FTIR) | Amide characteristics | |

| Condition | Fish Collagen | ||

| Amide A | 3350-3550 | 3332.29 | NH¹ Stretch |

| Amide B | 2935-2915 | 2924.09 | CH2² asymmetric stretching |

| Amide I | 1600-1700 | 1647.21 | C=O³ stretching |

| Amide II | 1480-1575 | 1546.91 | NH bending, CN³ stretching |

| Amide III | 1229-1301 | 1334. 74 | NH bending, CN³ stretching |

Table 3 presents the absorption peaks of various amide groups, essential for identifying collagen's structure via FTIR spectroscopy. The observed peaks for Amides A, B, I, II, and III in Catfish collagen align with the characteristic absorption ranges for these functional groups, affirming the protein's structure. Notably, Amide I's peak at 1647.21 cm-1 suggests the presence of secondary structures like alpha helices or beta sheets. A slight deviation in Amide III's peak suggests further investigation may be warranted to elucidate implications on collagen's structure or purity [24]. FTIR spectroscopy proves crucial for comparing collagen structures, processing modifications, or verifying protein identities, with broad applications in biomaterials, food science, and biomedical research.

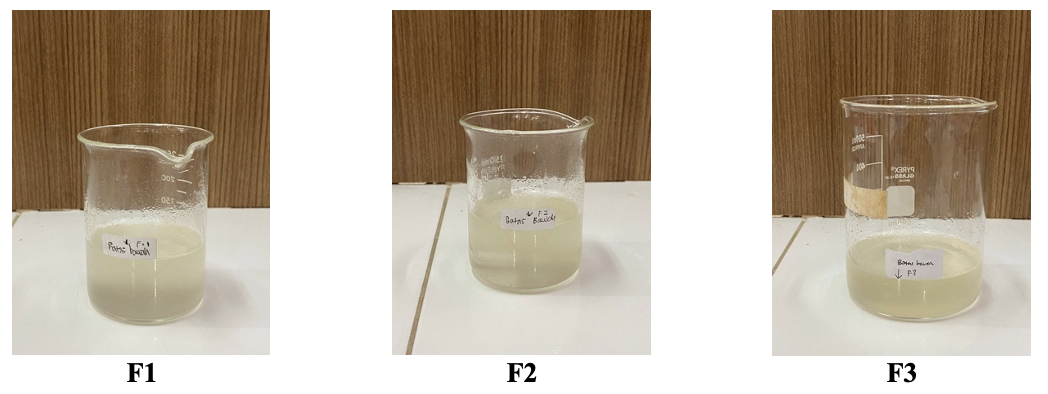

Organolectic gel evaluation

The gel base formulation consists of HPMC, propylene glycol, propyl paraben, methyl paraben, and distilled water. The basic components refer to the standard formula with modifications to the percent HPMC which has been selected based on research orientation. The gel base formulation can be seen in fig. 2.

Fig. 2: Gel preparation, organoleptic examination of preparations includes shape, color and odor, which are observed visually. The organoleptic test results can be seen in table 5

Table 5: Organoleptic test results for gel preparations

| Formulas | Form | Smell | Color |

| F1 | Thick | Typical of Aloe Vera | clear colorless |

| F2 | Thick | Typical of Aloe Vera | clear colorless |

| F3 | Thick | Typical of Aloe Vera | clear colorless |

Storage stability

The preparation was stored at low temperature (4±2 °C) in the freezer for 12 w. Observations are carried out once a week and visual evaluation (shape, color and smell). The results of the evaluation of the stability of the gel preparation can be seen in table 6.

Gel preparation pH test results

pH measurements on gel preparations were carried out by measuring the pH of gel preparations every week during a storage period of 12 w. The pH test results of the gel preparation can be seen in table 8.

Table 6: Effect of low temperature on the stability of gel preparations

Storage time (Week) |

Organoleptic | ||||||||

| Form | Color | Smell | |||||||

| F1 | F2 | F3 | F1 | F2 | F3 | F1 | F2 | F3 | |

| 0 | T | T | T | C | C | C | Aloe typical | Aloe typical | Aloe typical |

| 1 | T | T | T | C | C | C | Aloe typical | Aloe typical | Aloe typical |

| 2 | T | T | T | C | C | C | Aloe typical | Aloe typical | Aloe typical |

| 3 | T | T | T | C | C | C | Aloe typical | Aloe typical | Aloe typical |

| 4 | T | T | T | C | C | C | Aloe typical | Aloe typical | Aloe typical |

| 5 | T | T | T | C | C | C | Aloe typical | Aloe typical | Aloe typical |

| 6 | T | T | T | C | C | C | Aloe typical | Aloe typical | Aloe typical |

| 7 | T | T | T | C | C | C | Aloe typical | Aloe typical | Aloe typical |

| 8 | T | T | T | C | C | C | Aloe typical | Aloe typical | Aloe typical |

| 9 | T | T | T | C | C | C | Aloe typical | Aloe typical | Aloe typical |

| 10 | T | T | T | C | C | C | Aloe typical | Aloe typical | Aloe typical |

| 11 | T | T | T | C | C | C | Aloe typical | Aloe typical | Aloe typical |

| 12 | T | T | T | C | C | C | Aloe typical | Aloe typical | Aloe typical |

Information: T: thick; C: Clear, Additionally, The preparation was stored at high temperature (40±2 °C) in a climatic chamber for 12 w. Observations are carried out once a week and visual evaluation (shape, color and smell). The results of the evaluation of the stability of the gel preparation can be seen in table 7.

Table 7: Effect of high temperature on the stability of gel preparations

Storage time (week) |

Organoleptic | ||||||||

| Form | Color | Smell | |||||||

| F1 | F2 | F3 | F1 | F2 | F3 | F1 | F2 | F3 | |

| 0 | T | T | T | C | C | C | Aloe typical | Aloe typical | Aloe typical |

| 1 | T | T | T | C | C | C | Aloe typical | Aloe typical | Aloe typical |

| 2 | T | T | T | C | C | C | Aloe typical | Aloe typical | Aloe typical |

| 3 | T | T | T | C | C | C | Aloe typical | Aloe typical | Aloe typical |

| 4 | T | T | T | C | C | C | Aloe typical | Aloe typical | Aloe typical |

| 5 | T | T | T | C | C | C | Aloe typical | Aloe typical | Aloe typical |

| 6 | T | T | T | C | C | C | Aloe typical | Aloe typical | Aloe typical |

| 7 | T | T | T | C | C | C | Aloe typical | Aloe typical | Aloe typical |

| 8 | T | T | T | C | C | C | Aloe typical | Aloe typical | Aloe typical |

| 9 | T | T | T | C | C | C | Aloe typical | Aloe typical | Aloe typical |

| 10 | T | T | T | C | C | C | Aloe typical | Aloe typical | Aloe typical |

| 11 | T | T | T | C | C | C | Aloe typical | Aloe typical | Aloe typical |

| 12 | T | T | T | C | C | C | Aloe typical | Aloe typical | Aloe typical |

Information: T: thick; C: Clear

Table 8: pH test results for gel preparations in storage for 6 cycles (per 2 w)

| Storage time (Cycle) | pH Mean±SD | ||

| F1 | F2 | F3 | |

| 0 | 6.39±0.2 | 6.34±0.18 | 6.27±0.13 |

| 1 | 6.38±0.12 | 6.32±0.12 | 6.25±0.15 |

| 2 | 6.36±0.21 | 6.30±0.08 | 6.22±0.22 |

| 3 | 6.34±0.11 | 6.28±0.14 | 6.20±0.25 |

| 4 | 6.34±0.12 | 6.25±0.16 | 6.17±0.13 |

| 5 | 6.31±0.12 | 6.23±0.18 | 6.15±0.14 |

| 6 | 6.39±0.12 | 6.34±0.26 | 6.27±0.23 |

Information: Data given in mean±SD (n = 3)

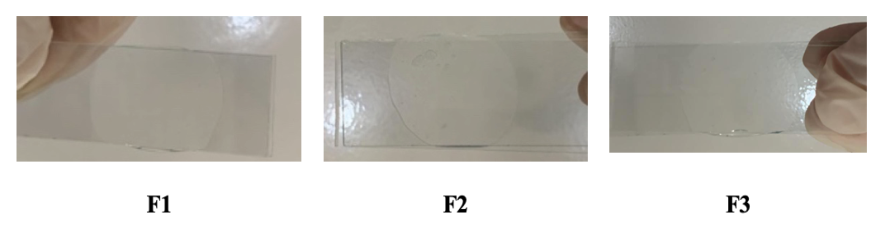

Fig. 3: Homogeneity test

Table 9: Gel viscosity test results before and after the clicking test

| Timeline | Formula | Results |

| Before | F1 | 591.1±15.2 cP |

| F2 | 566.8± 13.1 cP | |

| F3 | 591.4±14.3 cP | |

| After | F1 | 556.0± 11.4 cP |

| F2 | 566.5± 9.3 cP | |

| F3 | 589.7±6.4 cP |

Information: data given in mean±SD (n = 3)

Gel preparation, viscosity and homogeneity test results

Viscosity testing aims to determine the resistance of a preparation to flow. The viscosity test results of the gel preparation can be seen in table 9.

Homogeneity test

From the images, it seems that all three gel samples (F1, F2, F3) show similar transparency, which could be a good initial indicator of homogeneity. No signs of phase separation or agglomeration were visually visible. All samples appear to have similar consistencies based on their appearance. This suggests that the gelling process may have been carried out by a method that resulted in a uniform distribution of the ingredients in each formula. There were no visible inclusions or trapped air "pockets" in the samples, indicating a good mixing process and possibly high efficiency in providing homogeneity.

Rat diabetic animal model development

Testing of the wound healing activity of the combination of Aloe vera extract and fish collagen was carried out by first measuring the fasting blood glucose levels of the mice, then the mice were induced with Nicotinamide 110 mg/kgBW i. p. after 15 min followed by induction of Streptozotocin 60 mg/kgBW i. p., after three days the blood glucose was measured. Treatment begins when the rat's blood glucose level exceeds 200 mg/dL [25]. The blood glucose results obtained can be seen in table 10.

Table 10: Blood glucose levels of test animals

| Rat No | G1 | G2 | G3 | G4 | G5 |

| Blood glucose (mg/dl) | |||||

| 1 | 356 | 110 | 276 | 232 | 321 |

| 2 | 311 | 121 | 352 | 242 | 256 |

| 3 | 298 | 138 | 362 | 292 | 287 |

| 4 | 291 | 147 | 288 | 321 | 299 |

| 5 | 327 | 156 | 298 | 285 | 367 |

| Mean±SD | 316.6±25.9* | 134.4± 18.8 | 315.2±39.1* | 274.4±36.8* | 306±41.4* |

Information: Data given in mean±SD (n = 5). G1: negative control group of DM mice (without gel administration); G2: normal group (without gel administration); G3: DM Rat group (F1 gel administration); G4: DM Rat group (F2 gel administration); G5: DM Rat group (F3 gel administration); *: Significantly different to G1 (P<0.05).

In this research, treatment with a combination of Aloe vera extract and fish collagen was tested as an effort to determine its effectiveness in accelerating wound healing in mice. Through this testing, a number of factors are then taken into consideration, such as fasting blood glucose levels and cholesterol levels, all of which have been shown to have a significant impact on wound healing. Mice were induced with nicotinamide and streptozotocin (STZ) to simulate diabetic conditions. These two substances function to damage pancreatic beta cells in mice, which causes an increase in blood glucose levels [26]. This is necessary so that researchers can see the effect of the combination of Aloe vera extract and fish collagen on wound healing under conditions influenced by diabetes.

Wound healing efficacy in diabetic rats

Observation of the effectiveness of wound healing in diabetic mice was carried out visually, seen from the decreasing diameter of the wound and the increasing percentage of reduction in wound area. In the wound healing process there are several phases, one of which is the inflammatory phase. Anti-inflammatory activity is found in flavonoid, phenol and tannin compounds. The mechanism of flavonoid compounds in inhibiting the process of inflammation in wounds is through various methods, namely inhibiting capillary permeability, inhibiting the release of serotonin and histamine to the site of inflammation, arachidonic acid metabolism by inhibiting the work of cyclooxygenase, and the secretion of lysosomal enzymes which are inflammation mediators [27]. Meanwhile, phenolic compounds function in inhibiting inflammation by capturing free radicals, which can cause tissue damage, which will trigger the biosynthesis of arachidonic acid into inflammatory mediators, namely prostaglandins, and can inhibit the cyclooxygenase enzyme [28]. The saponin contained in the extract is efficacious as a cleanser and antiseptic, which can accelerate the wound healing process, characterized by the ability to form persistent foam. It has the ability to act as a cleaner and antiseptic, which functions to kill and prevent the growth of microorganisms [29]. Average data on the percentage of wound healing in diabetic mice can be seen in table 11.

The best wound healing percentage graph is aimed at data from groups G5 and G4, who were given treatment gel with a combination of Aloe vera extract and fish collagen as a wound healer, compared to the control group G1 with diabetes, which had the lowest percentage of wound healing. This proves that administering a gel combination of Aloe vera extract and fish collagen can accelerate the wound healing process. This cannot be separated from the phytochemical content of the combination of Aloe vera extract and fish collagen, which has the potential to heal wounds. Several studies state that the combination of Aloe vera extract and fish collagen contains various active phytochemicals that promote the wound healing process. These active ingredients include flavonoids, tannins and terpenoids, which have been shown to have anti-inflammatory, antibacterial and antioxidant activities [30, 31].

With diabetes and a high-fat diet, wounds are often difficult to heal because high blood sugar levels can damage blood vessels and inhibit the transport of nutrients and oxygen to damaged tissue. Therefore, the fact that a combination gel of Aloe vera extract and fish collagen can improve wound healing rates in these conditions is of great importance and shows its potential as an alternative or additional wound treatment for these conditions. Apart from that, the antioxidant content in the combination of Aloe vera extract and fish collagen also plays an important role in the healing process. Antioxidants help protect cells and tissues from oxidative damage and free radicals, which can speed the healing process and reduce the risk of complications.

Table 11: Data on the percentage of wound healing

| Days to- | Wound healing percentage (%) (Mean±SD) | ||||

| G1 | G2 | G3 | G4 | G5 | |

| 1 | 0.00±0.00 | 0.00±0.00 | 0.00±0.00 | 0.00±0.00 | 0.00±0.00 |

| 2 | 7.89±0.54 | 6.31±0.42 | 5.87±0.63 | 15.72±0.81 | 12.44±0.56 |

| 3 | 12.28±0.69 | 13.06±0.75 | 24.91±0.85 | 35.47±0.88 | 32.79±0.73 |

| 4 | 21.16±0.51 | 16.82±0.49 | 30.67±0.62 | 44.81±0.95 | 37.68±0.78 |

| 5 | 25.03±0.78 | 21.94±0.47 | 39.58±0.91 | 54.69±0.57 | 45.12±0.88 |

| 6 | 24.88±0.66 | 34.91±0.86 | 47.74±0.71 | 60.25±0.93 | 49.89±0.61 |

| 7 | 32.19±0.74 | 45.12±0.98 | 62.08±0.86 | 69.51±0.64 | 65.43±0.58 |

| 8 | 42.77±0.63 | 56.88±0.71 | 67.81±0.43 | 79.26±0.86 | 70.54±0.69 |

| 9 | 47.81±0.87 | 64.62±0.57 | 73.94±0.79 | 87.93±0.93 | 75.19±0.65 |

| 10 | 52.34±0.76 | 73.11±0.65 | 78.66±0.74 | 94.81±0.41 | 81.68±0.59 |

| 11 | 62.75±0.53 | 80.47±0.69 | 92.83±0.67 | 98.92±0.35 | 93.75±0.42 |

| 12 | 72.19±0.44 | 95.36±0.64 | 96.41±0.29 | 100.00±0.00 | 97.89±0.37 |

| 13 | 74.96±0.33 | 100.00±0.00 | 100.00±0.00 | 100.00±0.00 | 100.00±0.00 |

| 14 | 83.15±0.48 | 100.00±0.00 | 100.00±0.00 | 100.00±0.00 | 100.00±0.00 |

Information: Data given in mean±SD (n = 5). G1: negative control group of DM mice (without gel administration); G2: normal group (without gel administration); G3: DM Rat group (F1 gel administration); G4: DM Rat group (F2 gel administration); G5: DM Rat group (F3 gel administration).

Fig. 4: Graphic presentation of wound healing, data given in mean±SD (n = 5)

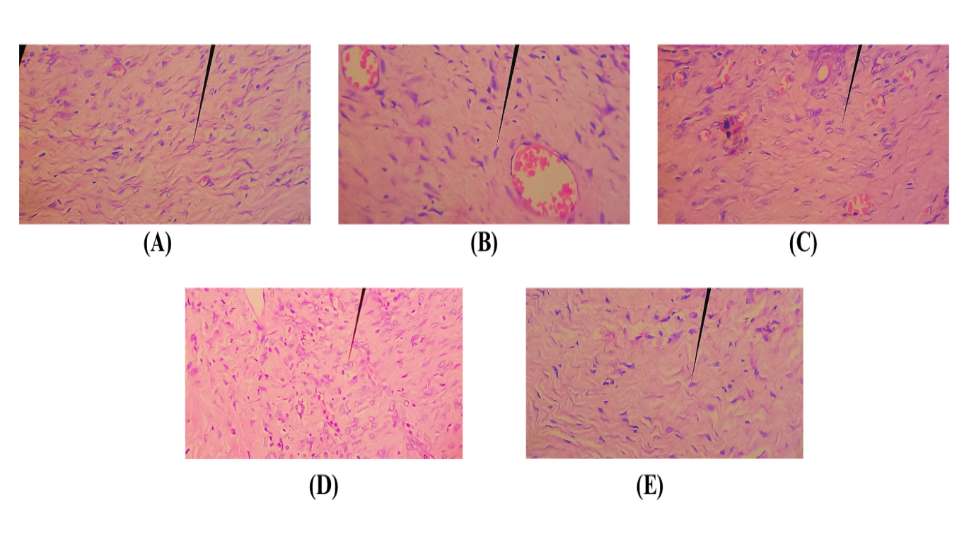

Histopathological examination results

Histopathological examination was carried out after dissection of rat skin tissue. This was carried out by examining histological tissue by staining using Hematoxylin-Eosin (HE) on the skin of mice that had been treated. Histopathological observations were carried out to see fibroblast tissue and collagen density in test animals for each group. Fibroblast tissue examination was carried out by observation using a microscope with 40x magnification. The results of observations of fibroblast tissue growth observed in each treatment group can be seen in table 12.

Fig. 5: Histopathological image of fibroblast network. (a) G1; (b) G2; (c) G3; (d) G4; (e) G5; (→) part of fibroblast tissue

Table 12: Average results of fibroblast tissue

| Treatment group | Number of fibroblast tissues |

| G1 | 26.33±13.62 |

| G2 | 33.00±6.00* |

| G3 | 45.33±4.78*# |

| G4 | 66.00±12.42*# |

| G5 | 62.67±21.47*# |

Information: data given in mean±SD (n = 5). G1: negative control group of DM mice (without gel administration); G2: normal group (without gel administration); G3: DM Rat group (F1 gel administration); G4: DM Rat group (F2 gel administration); G5: DM Rat group (F3 gel administration); *: Significantly different to G1 (P<0.05); #: Significantly different toG2 (P<0.05)

The histopathological images (fig. 5) provide a visual assessment of fibroblast networks correlating with the quantitative data from table 11. The negative control DM mice group (G1) and normal group (G2) show less dense fibroblast networks. Groups treated with F1 (G3), F2 (G4), and F3 (G5) gels display progressively denser and more organized fibroblast structures, with G4 and G5 showing the most pronounced improvement. These observations are statistically significant when compared to G1 and G2, indicating the potential of F2 and F3 gels to enhance fibroblast proliferation and potentially improve diabetic wound healing. Further research is warranted to optimize these gels for therapeutic use. Phytochemical compounds found in various plants, including Aloe vera, are known to have various prominent biological activities, one of which is increasing fibroblast cell proliferation. Phytochemicals can influence the wound healing process through various mechanisms, all of which contribute to optimal fibroblast function and proliferation. First, several polyphenolic phytochemical compounds are able to stimulate the growth and development of cells, including fibroblasts [32]. They achieve this by interacting with diverse signaling pathways in cells, which trigger vital processes such as cell division and differentiation. Then their powerful anti-inflammatory activity can reduce inflammation; they create a more favorable environment for fibroblast proliferation and wound healing. Then, polyphenol compounds act as antioxidants, which are able to neutralize free radicals that can damage cells and tissues. By protecting fibroblasts from oxidative damage, these compounds contribute to maintaining cell integrity and function. Lastly, phytochemicals can stimulate fibroblasts to increase the production of extracellular matrix (ECM), a structure that provides structural and nutritional support for tissues, thereby speeding up the wound healing process [33].

Collagen density results

The results of observations of collagen density in the wound healing process using a microscope with 10x magnification can be seen in table 13.

Table 13: Average collagen density results

| Treatment group | Collagen density |

| G1 | 1.00±0.00 |

| G2 | 2.00±0.21* |

| G3 | 2.00±1.00*# |

| G4 | 3.00±0.13*# |

| G5 | 2.00±1.00*# |

Information: Data given in mean±SD (n = 5). G1: negative control group of DM mice (without gel administration); G2: normal group (without gel administration); G3: DM Rat group (F1 gel administration); G4: DM Rat group (F2 gel administration); G5: DM Rat group (F3 gel administration); *: Significantly different to G1 (P<0.05); #: Significantly different to G2 (P<0.05). Score 0: No collagen fibers; Score 1: ˂10% collagen density; Score 2: 10-50% collagen density; Score 3: 50%-90% collagen density; Score 4: ˃90% collagen density.

Fig. 6: Histopathological picture of collagen density (a) G1; (b) G2; (c) G3; (d) G4; (e) G5; (→) collagen part

Based on fig. 6, the histopathological results of collagen density clearly show differences in each group. Group 4 has the highest score, namely 3, where G4 has 50%-90% collagen density. Meanwhile, G1 has the lowest collagen density score, namely 1 (˂10% collagen density). Collagen is the most abundant protein in the skin's extracellular matrix, and functions to fill the extracellular matrix. In the wound healing process, collagen is formed from the 3rd day and will become visible in quantity on the 7th day after the wound, and begins to stabilize and organize around the 14th d. In the wound healing process, the secondary metabolite content of plants is able to activate various pathways to increase the number of fibroblasts that migrate to the wound, proliferate, and produce collagen matrix. As the number of fibroblasts increases, the density of collagen fibers also increases [34].

CONCLUSION

Aloe vera extract shows strong antioxidant activity and potential for wound healing. IR spectral analysis confirms the collagen extract meets standard characteristics. The formulated gel passes homogeneity testing, and physical evaluation, stability tests, and in vivo studies on STZ-induced rats yield positive results. Notably, formulation F2 in Group 4 demonstrates the most effective wound healing.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Author thanks to Lembaga Penelitian Universitas Sumatera Utara for providing research grant under Grant Number: 98/UN5.2.3.1/PPM/KP-TALENTA/R/2023 Dated: 29 August 2023

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Julia Reveny led the experimental design, execution, and manuscript composition. Sony Eka Nugraha, as the corresponding author, was pivotal in theoretical development, methodological verification, and manuscript finalization. Adira and Nuratika contributed significantly to conducting the experiments and preparing samples. All team members collaborated on refining the study and the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Authors declare no conflict of interest

REFERENCES

Irawan HE, Mooy DZ, Yasa KP. Short-term result of percutaneous transluminal angioplasty on ischemia diabetic foot ulcer. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2018;11(5):4-6. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2018.v11i5.24759.

MC Dermott K, Fang M, Boulton AJ, Selvin E, Hicks CW. Etiology, epidemiology and disparities in the burden of diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(1):209-21. doi: 10.2337/dci22-0043, PMID 36548709.

Lin C, Liu J, Sun H. Risk factors for lower extremity amputation in patients with diabetic foot ulcers: a meta-analysis. Plos One. 2020;15(9):e0239236. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239236, PMID 32936828.

Burgess JL, Wyant WA, Abdo Abujamra B, Kirsner RS, Jozic I. Diabetic wound healing science. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57(10):1072. doi: 10.3390/medicina57101072, PMID 34684109.

Loggenberg SR, Twilley D, De Canha MN, Lall N. Medicinal plants used in South Africa as antibacterial agents for wound healing. In: Medicinal Plants as Anti-infectives. Elsevier; 2022. p. 139-82. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-323-90999-0.00018-5.

Liang J, Cui L, LI J, Guan S, Zhang K, LI J. Aloe vera: a medicinal plant used in skin wound healing. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2021;27(5):455-74. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEB.2020.0236, PMID 33066720.

Razia S, Park H, Shin E, Shim KS, Cho E, Kang MC. Synergistic effect of aloe vera flower and aloe gel on cutaneous wound healing targeting MFAP4 and its associated signaling pathway: in vitro study. J Ethnopharmacol. 2022;290:115096. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2022.115096, PMID 35182666.

Sapula P, Bialik Wąs K, Malarz K. Are natural compounds a promising alternative to synthetic cross-linking agents in the preparation of hydrogels? Pharmaceutics. 2023;15(1):253. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics15010253, PMID 36678882.

Chithra P, Sajithlal GB, Chandrakasan G. Influence of aloe vera on collagen characteristics in healing dermal wounds in rats. Mol Cell Biochem. 1998;181(1-2):71-6. doi: 10.1023/a:1006813510959, PMID 9562243.

Marchianti AC, Prameswari MC, Sakinah EN, Ulfa EU. The enhancement of collagen synthesis process on diabetic wound by Merremia mammosa (Lour.) extract fraction. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2018;11(2):47-50. doi: 10.22159/ijpps.2019v11i2.30170.

Pawelec KM, Best SM, Cameron RE. Collagen: a network for regenerative medicine. J Mater Chem B. 2016;4(40):6484-96. doi: 10.1039/c6tb00807k, PMID 27928505.

Qing C. The molecular biology in wound healing and non-healing wound. Chin J Traumatol. 2017;20(4):189-93. doi: 10.1016/j.cjtee.2017.06.001, PMID 28712679.

Varshney AK CV. Effect of centrifuge speed on gel extraction from aloe vera leaves. J Food Process Technol. 2013;5(1):295. doi: 10.4172/2157-7110.1000295.

Fabella N, Herpandi H, Widiastuti I. Pengaruh metode ekstraksi terhadap karakteristik kolagen dari kulit ikan patin (Pangasius pangasius). Fishtec H. 2018;7(1):69-75. doi: 10.36706/fishtech.v7i1.5982.

DE Silva GO, Abeysundara AT, Aponso MM. Extraction methods qualitative and quantitative techniques for screening of phytochemicals from plants. Am J Essent Oils Nat Prod. 2017;5(2):29-32.

Kaur C, Kapoor HC. Anti‐oxidant activity and total phenolic content of some Asian vegetables. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2002;37(2):153-61. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2621.2002.00552.x.

Sen S, DE B, Devanna N, Chakraborty R. Total phenolic total flavonoid content and antioxidant capacity of the leaves of Meyna spinosa roxb an Indian medicinal plant. Chin J Nat Med. 2013;11(2):149-57. doi: 10.1016/S1875-5364(13)60042-4, PMID 23787182.

Abdassah M, Rusdiana T, Subghan A, Hidayati G. Formulasi gel pengelupas kulit mati yang mengandung etil vitamin c dalam sistem penghantaran macrobead. J Ilmu Kefarmasian Indones. 2009;7(2):107.

Cruz PL, Moraes Silva IC, Ribeiro AA, Machi JF, De Melo Md, Dos Santos F. Nicotinamide attenuates streptozotocin-induced diabetes complications and increases survival rate in rats: role of autonomic nervous system. BMC Endocr Disord. 2021;21(1):133. doi: 10.1186/s12902-021-00795-6, PMID 34182970.

Hajiaghaalipour F, Kanthimathi MS, Abdulla MA, Ihsan M, Rahmadian R, Raymond B. Comparison of burn wound histopathology imaging between epidermal growth factor spray and silver sulfadiazine application: an in vivo study. Bioscientia Medicina. J Biomed Transl Res. 2022;6(5):1749-56. doi: 10.37275/bsm.v6i5.509.

Slaoui M, Fiette L. Histopathology procedures: from tissue sampling to histopathological evaluation. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;691:69-82. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-849-2_4, PMID 20972747.

Maliehe TS, Nqotheni MI, Shandu JS, Selepe TN, Masoko P, Pooe OJ. Chemical profile antioxidant and antibacterial activities mechanisms of action of the leaf extract of aloe arborescens mill. Plants (Basel). 2023;12(4):869. doi: 10.3390/plants12040869, PMID 36840217.

Zhu HM, Yan JH, Jiang XG, Lai YE, Cen KF. Study on pyrolysis of typical medical waste materials by using TG-FTIR analysis. J Hazard Mater. 2008;153(1-2):670-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.09.011, PMID 17936504.

Zaelani B, Safithri M, Tarman K, Setyaningsih I, Meydia. Collagen isolation with acid-soluble method from the skin of red snapper (lutjanus sp.). IOP Conf Ser: Earth Environ Sci. 2019;241:012033. doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/241/1/012033.

Prasetyo MR, Ghalib QM, Ahsani DN, Fidianingsih I. Consumption of cassava extract (manihot esculenta) improves pancreatic histology and seminiferous tubules in wistar rats induced diabetes mellitus with streptozotocin. Jurnal Aisyah Jurnal Ilmu Kesehatan. 2023;8(2):563-8. doi: 10.30604/jika.v8i2.1929.

Szkudelski T. Streptozotocin nicotinamide induced diabetes in the rat characteristics of the experimental model. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2012;237(5):481-90. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2012.011372, PMID 22619373.

Rios JL. Mechanisms of action of anti-inflammatory phytochemicals. In: Watson RR, Preedy VR, editors. Botanical Medicine in Clinical Practice. UK: CAB International; 2008. p. 524-34. doi: 10.1079/9781845934132.0524.

Arulselvan P, Fard MT, Tan WS, Gothai S, Fakurazi S, Norhaizan ME. Role of antioxidants and natural products in inflammation. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016:5276130. doi: 10.1155/2016/5276130, PMID 27803762.

Men SY, Huo QL, Shi L, Yan Y, Yang CC, YU W. Panax notoginseng saponins promotes cutaneous wound healing and suppresses scar formation in mice. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19(2):529-34. doi: 10.1111/jocd.13042, PMID 31267657.

Yatoo MI, Gopalakrishnan A, Saxena A, Parray OR, Tufani NA, Chakraborty S. Anti-inflammatory drugs and herbs with special emphasis on herbal medicines for countering inflammatory diseases and disorders a review. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2018;12(1):39-58. doi: 10.2174/1872213X12666180115153635, PMID 29336271.

Melo LF, Aquino Martins VG, Silva AP, Oliveira Rocha HA, Scortecci KC. Biological and pharmacological aspects of tannins and potential biotechnological applications. Food Chem. 2023;414:135645. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.135645, PMID 36821920.

Pham DC, Shibu MA, Mahalakshmi B, Velmurugan BK. Effects of phytochemicals on cellular signaling: reviewing their recent usage approaches. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2020;60(20):3522-46. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2019.1699014, PMID 31822111.

Merecz Sadowska A, Sitarek P, Kucharska E, Kowalczyk T, Zajdel K, Ceglinski T. Antioxidant properties of plant-derived phenolic compounds and their effect on skin fibroblast cells. Antioxidants (Basel). 2021;10(5):726. doi: 10.3390/antiox10050726, PMID 34063059.

Lodhi SA, Vadnere GP. Relevance and perspectives of experimental wound models in wound healing research. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2017;10(7):57-62. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2017.v10i7.18276.