Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 6, 2025, 38-48Reviewl Article

ADVANCEMENTS IN LIPID-BASED NANOTHERANOSTICS FOR MANAGING ATHEROSCLEROSIS: A REVIEW

MANIGANDAN DHORAI1, IMRANKHAN NIZAM1, KALAISLEVI AASAITHAMBI2, GOWTHAMARJAN KUPPUSAMY1*

1Department of Pharmaceutics, JSS College of Pharmacy, JSS AHER, Ooty, Nilgiris, Tamil Nadu, India. 2Divison of Biotechnology, School of Life Sciences (Ooty Campus), JSS Academy of Higher Education and Research, Mysuru, Karataka, India.

*Corresponding author: Gowthamarjan Kuppusamy; *Email: gowthamsang@jssuni.edu.in

Received: 06 May 2024, Revised and Accepted: 20 Sep 2025

ABSTRACT

Atherosclerosis, a complicated and chronic inflammatory disorder, is the main cause of various cardiovascular issues, including coronary heart assaults and strokes. Acute myocardial infarction and stroke can be partially prevented with current clinical measures, such as statin medications, but the risk is still very high. The concept of combinatorial therapy using both diagnosis and therapeutics through a single platform is known as theranostics. As evident from pre-clinical and clinical studies, nano-based theranostics are widely used in cancer detection and treatment. Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs), nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs), and nanoliposomes are examples of synthetic/natural lipid-based delivery systems that have drawn much interest as nano-scaled drug delivery system due to their potential benefits, which include easy large-scale production, relatively low toxicity, and composition accessibility. Traditionally, for the study and evaluate the effects of therapy on atherosclerosis, x-ray angiography was used.

Nevertheless, measuring the amount of stenosis brought on by plaques remains the main objective of clinical studies for atherosclerosis. Several high-risk plaque features, such as a thin fibrous cap, a big necrotic core, macrophage infiltration, neovascularization, and intraplaque bleeding, can now be investigated using cutting-edge imaging methods. This review summarises nanotheranostic for diagnosing and treating atherosclerosis and the different strategies for targeting atherosclerotic plaque.

Keywords: Atherosclerosis, Lipid-based nanotheranostics, Targeted therapy, Cardiovascular diseases, Nanomedicine, Diagnostic imaging

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i6.51321 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

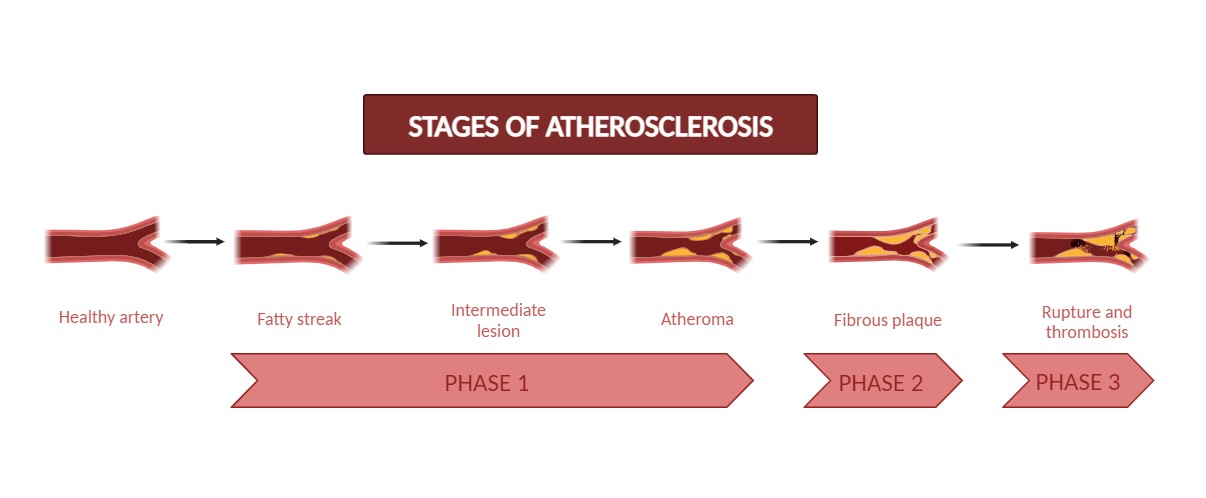

Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory condition that stems from the narrowing of arteries. The slow development of atherosclerosis is caused by plaque formed by blood components such as cholesterol, fat, and red blood cells. The accumulation of plaque narrows your arteries. As a result, the body's essential organ tissues receive less blood that is rich in oxygen. This narrowing of the arteries is characterized by the deposition of lipids, especially modified lipids such as oxidized-low density lipoproteins (ox-LDL), which trigger responses such as macrophage and platelet aggregation in the intima layer of the blood vessel. This plaque formation makes it difficult for blood flow. Plaque formation hinders blood flow, posing a challenge [1]. Plaque formation hinders blood flow, posing a challenge [1]. As atherosclerosis progresses, phagocytic cells boost the secretion of adhesion molecules, which leads to heightened production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) [2, 3]. This process eventually causes the oxidation of low-density lipoproteins (LDL) within blood vessels, thus aiding in forming foam cells. Macrophages then recognize oxidised low-density lipoprotein (ox-LDL) within the smooth plaque and become phagocytic cells. Due to the ongoing loss of smooth muscle cells and lack of collagen fibres in the fibrous cap [4], this eventually leads to the breakdown of cartilage, and the ruptured vessel forms a blood clot, leading to thrombosis.

Fig. 1: Different stages of atherosclerosis

The rupture of the plaque may lead to complications such as coronary artery diseases, carotid artery diseases, and stroke [1]. Two major types of plaque are non-stable or vulnerable and stable. Asymptomatic, stable plaques have a thick fibrous cap and a lipid core, whereas susceptible plaques are macrophage-enriched, having a thin fibrous cap and big necrotic cores with lipids.

It is now widely acknowledged that the atherosclerotic plaques that cause thrombus formation do not always have the greatest impact on the vessel's lumen. Nevertheless, measuring the amount of stenosis brought on by plaques remains the main goal of clinical studies for atherosclerosis.

The majority of clinical studies on atherosclerosis indicate the degree of stenosis brought on by the plaque. The initial findings from angiography and results from randomized controlled trials using HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) demonstrated a dissociation between the degree of stenosis and clinical outcomes. While statins significantly lower acute cardiovascular events, they only slightly reduce stenosis. Statins cause significant alterations in plaque composition, yet this does not consistently affect plaque size or the resulting stenosis [5].

Novel imaging techniques are now available to probe all of these traits, each with advantages and disadvantages of their own. Certain approaches, such as intravascular ultrasound of the coronary arteries and ultrasound imaging of the carotid intima-media thickness, are already being used in clinical settings. Other methods, such as positron emission tomography (PET) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), have been applied in studies to analyze the chemical characteristics of carotid artery plaque and may prove useful in clinical settings.

Nanotheranostic aims to implement and further develop advanced nanotherapeutic strategies, using different nanocarriers for fewer side effects and better therapeutic effects, such as polymer conjugates, nanoparticles of bio-degradable polymers for controlled delivery, sustained delivery and targeted co-delivery (diagnostic, therapeutic agents, micelles, dendrimers, liposomes, metallic and inorganic nanoparticles, carbon nanotubes). Nanotechnology, which is used for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of disease at the cellular level, is called nanomedicine. It is also effective in creating a cure by combining diagnosis and treatment simultaneously [6]. Colloidal nanoparticles between 10 nm and 1000 nm (1m) in size are theranostic nanomedicines. These nanoparticles' macromolecular materials/polymers absorb, conjugate, entrap, and encapsulate the diagnostic and therapeutic agents. A few advanced capabilities of theranostic nanomedicine that can be performed on a single platform include [Controlled/Sustained Release, Targeted delivery, higher endocytosis transport efficiency, Stimulus-responsive agent release (also known as smart delivery), and synergetic performance (e.g., combination therapy, siRNA co-delivery)] [7]. Quality performances (such as oral administration, evading the multi-drug resistance (MDR) protein, and autism), among others, are multimodality diagnosis and therapy [8]. In this review, the different targeting strategies and diagnostic and therapeutic modalities of the nanoparticles for atherosclerotic plaque were discussed.

Peptides, proteins, genetic materials, and hydrophobic organic medicines are the therapeutic agents in theranostic nanomedicine. Diagnostic agents are widely employed in theranostic nanomedicine in addition to therapeutic agents. These include agents for optical imaging (Quantum Dots or Fluorescent Dyes), magnetic resonance imaging MRI (superparamagnetic metals, such as iron oxides), nuclear imaging (radionuclides), and Computed Tomography (CT) (heavy elements, such as iodine). When external energy sources stimulate semiconductor crystals, known as quantum dots, they release signals. Because they have several benefits over organic dyes, quantum dots are a common nanomaterial among diagnostic agents utilized in therapeutic nanomedicine. In addition, quantum dots have photostable properties, higher absorption coefficients, great brightness, and extremely strong signals [9].

Theranostic is a cutting-edge medical branch offering customized therapy based on precise, targeted diagnostic testing. The advantage of combining diagnostic and treatment in a single agent has accelerated the development of theranostic nanoparticles in recent decades, even though theranostic research on CVDs is still in its infancy [10]. As a result, they represent a potent strategy for patient-centred, safe, and tailored medication.

Search Criteria: The review was constructed using articles from Elsevier, Pubmed, Science Direct, springer, New England journal of medicine (NEJM), Scopus, Google scholar within a range of 2000-2024 using the keywords Atherosclerosis, Cardiovascular diseases(CVDs), lipid nanoparticles, theranostics, images techniques, targeting strategies.

Nanoparticles as prevention and treatment devices

Lipid-based nanoparticles

SLNs, NLCs, and nanoliposomes are examples of synthetic or natural lipid-based delivery systems that have attracted interest as nanoscale drug delivery systems due to potential advantages, including accessibility and size, low toxicity, and ease of formulation.

Liposomes

Among the lipid-based nanoparticles, liposomes have been the most studied spherical particles composed of one or more phospholipid layers. Liposomes can be single, oligo-or multilamellar vesicles depending on their lamellarity. Both hydrophilic and hydrophobic substances can be incorporated into the lipid layer or core. Liposomes are made of cationic lipids and are likely to be loaded with polyanions (nucleic acids like DNA and RNA) [11]. The main disadvantage of these carriers as drug delivery system is phagocytosis by macrophages, resulting in biological/physical half-life failure occurring from enzymatic degradation and effective chemical defence, although liposomes have potential advantages like high bio-compatibility, minimal immunogenicity, and effective drug protection due to enzymatic destruction [12, 13]. To overcome such issues, the surface of liposomes can be modified with organic and semi-organic polymers, peptides, or antibodies. A common modification uses a hydrophilic polymer called the biodegradable Poly Ethylene Glycol (PEG) and the liposome exterior to produce a stealth carrier.

Joner et al. evaluated TRM-484, a novel drug containing prednisolone nanoparticles targeting chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPGs), aiming to suppress neointimal growth while avoiding systemic side effects. Atherosclerotic rabbits with stents received intravenous TRM-484 or controls. TRM-484 localized exclusively at stent injury sites, significantly increasing in stented arteries within 24 h. At 1 mg/kg, TRM-484 notably reduced stenosis compared to controls. This targeted approach may offer a cost-effective strategy for preventing in-stent restenosis by focusing treatment precisely on injured atherosclerotic areas, potentially enhancing therapeutic efficacy while minimizing systemic adverse effects [14].

Calin and their group developed a Teijin-loaded Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule-1 (VCAM-1) directed TSL (target-sensitive liposome), a CCR-2 antagonist, to target the early inflammation process while reducing adhesion of monocytes and transmigration, which are frequent key events in atherosclerosis. An amalgam of DOPA and DOPE was used to create PEG-stabilized TSLs, and a functionalized (Mal-PEG-DSPE) phospholipid anchor was attached to the surface of the liposome to pair with VCAM-1 binding peptide. The study found that monocyte adherence was more enhanced in targeted TSL when compared to intact Teijin and non-targeted TSL [15].

Homem de Bittencourt et al. introduced endothelium formulations targeting lipocardium using cyclopentenone (CP)-prostaglandins (PG). It was found that male LDL receptor deletion mice responded better to negatively charged liposomes containing anti-VCAM-1 antibody and PGA-2. Lipocardium has proven to be a reliable method for cardioprotection due to its effects on anti-proliferative (specifically pro-apoptotic to foam cells), anti-inflammatory, anti-lipogenic properties, and cytoprotection through heat shock protein activation [16]. Hosseini et al. synthesized phosphatidylserine liposomes (PSLs), which inhibited vascular lesion progression by 42% and reduced macrophage accumulation by 47% in mice. As a result, PSLs resemble apoptotic cells by activating atheroprotective peritoneal B1a lymphocytes, and they produce a more specific type of antibody that subsequently reduces the local inflammation during atherosclerosis development, called polyreactive IgM [17].

Valk et al. synthesized Prednisolone phosphate as an atherosclerosis treatment encapsulated inside a liposome and covered in polyethylene glycol (LN-PLP). On analysis, LN-PLP showed enough circulation time to reach atherosclerotic lesions and accumulate in atherosclerotic plaques and macrophages. The data highlight the possibility of a vehicle for drug delivery to atherosclerotic lesions, even though the short-term administration of LN-PLP to atherosclerotic patients didn’t affect the inflammation of the arterial wall and its permeability [18].

In addition, liposome-based formulations containing cyclopentenone prostaglandin (CyPG) and serum-amyloid A (SAA) peptide fragments, both acting as potent antioxidants, were developed and have shown significant anti-atherogenic effects in the in vivo study [16, 19].

Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs)

SLNs are created as viable options for enhancing biocompatible colloidal drug delivery system and lipophilic bioactive substances' bioactivity and bioavailability [20]. Three basic techniques are used to create SLNs: homogenization, solventevaporation, and microemulsion. SLNs are produced without synthetic chemicals, making them a better option than other lipid-based formulations that may require such chemicals. Moreover, SLNs benefit frominert drug targeting, which means they can be incorporated at the proper spot in the body without the requirement for specific targeting agents, increasing the concentration of the medication at the vital point. Furthermore, SLNs shield the ingested medicine from chemical breakdown, ensuring the molecule's stability and efficacy until it reaches its target site in the body [21].

To increase the stability and the biological efficacy of tea polyphenols (TPPs) in CVDs, Kulandaivelu et al. reported using TPP-SLNs. TPP-SLNs were given orally, and they showed a significant decrease in various biochemical markers like triglyceride, cholesterol, bilirubin, urea, alanine aminotransferase, total protein, aspartate transaminase and alkaline phosphatase. These changes indicate that the treatment is positively affecting the body, particularly in heart health (cardioprotective). Furthermore, it was found that encapsulating cardioprotective agents protect SLNs from oxidation. While encapsulating marrubin in SLNs enhanced its ability to protect the cells from the harmful effects of Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (TNF-α). It made it a more effective and potentially safer option as a food additive or cardioprotective [22].

Paliwal et al. developed Low Molecular Weight Heparin (LMWH) lipid conjugates. To overcome the limitations of the oral administration of LMWH for the treatment of vascular disorders, they were encapsulated in phosphatidylcholine-stabilized biomimetic SLNs. They reported that the nanoparticle is a safe and effective way to give the medication orally it increases the bioavailability of LMWH [23].

Gao et al. also created daidzein iso-flavonoid SLNs to improve their oral absorption and bioavailability. Compared to regular medicine, it more effectively enhanced circulation time, decreased myocardial oxygen use, and reduced coronary resistance [24].

Nano-emulsions

Lipid nano-emulsions (LNE) are small particles made up of liquid fats, offering a safe and effective way of drug delivery [25]. These nano-emulsions are considered a good option for delivering drugs because of their various advantages, such as targeted delivery, sustained release, reduced toxicity, and flexible drug placement, and it is also suitable for unstable drugs or drugs that are poorly soluble in water. Therapeutic agents could be reconciled in the oil-water interface or the interior oil phase of the particles [26].

Tavares et al. researched the downgrading of lesions and the inflammation process in atherosclerotic rabbits using cholesterol-rich LNE combined with etoposide. Lesions in the blood vessels and intima width were reduced by 85%, and 50% was observed. Furthermore, it decreased receptors for lipoproteins, proliferation markers, and pro-inflammatory factors [27].

Bulgarelli et al. developed di-dodecyl-methotrexate (dd-MTX) nano-emulsions to research the impacts of abrasion and the expression of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory factors. There was a reduction in intimal macrophages (67%) and apoptotic cells (88%), a 65% reduction in the extent of lesions and a 2-fold increase in the intima-media ratio. LNE-dd-MTX down-regulated six pro-inflammatory genes (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-18, MCP-1, MMP-9, and MMP-12) and up-regulated other inflammatory genes (TNF-α, IL-1β, VAP-1, and CXCL2) in vitro. There was no movement of smooth muscle cells into the intima [28].

To enhance the anti-atherosclerosis benefits of etoposide-LNE and methotrexate compared to a single drug, Leite et al. designed a combined therapy. This method offers excellent promise for clinical use in people with CVDs [29].

Nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs)

The NLCs are another type of lipidic nanocarrier with numerous uses as drug delivery systems due to their enhanced drug-loading capacity, protection, and tiny size. They have a similar formulation to SLNs, but instead of solid lipids, they use liquid versions [30].

Using a nanoprecipitation/solvent diffusion technique, Zhang et al. created a drug carrier called Tanshinone 11A-loaded HDL-like NLC (TA-NLC) [31]. They discovered that TA-NLC can specifically bind to apolipoprotein A-1(apoA-1) and can effectively reach the target site without being attacked or excreted from the body. In a separate study, TA-d-rHDL and TA-s-rHDL(recombinant HDL containing tanshinone 11A (TA) loaded in discoidal and spherical shapes) were produced. Although s-rHDL demonstrated more targeted effects, both NLCs are more effective against atherosclerotic lesions than normal artery walls [32].

Polymeric nanocarriers

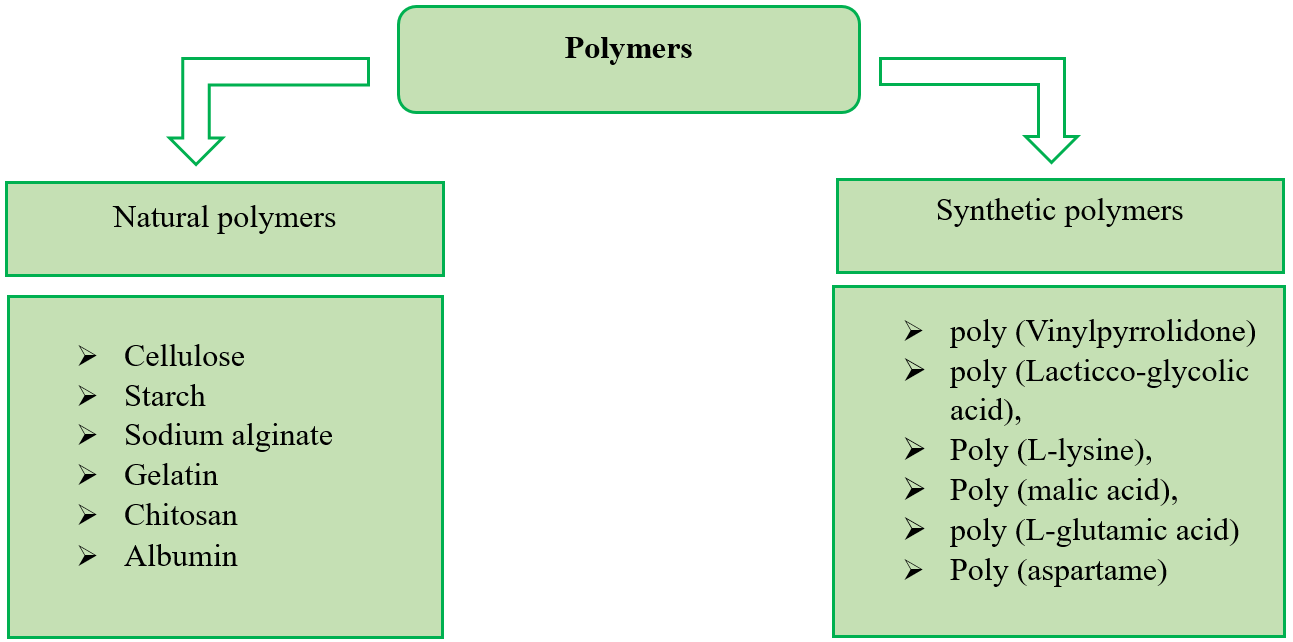

Polymeric nanocarriers are a different class of NPs used for medication delivery. It comprises a variety of artificial or organic macromolecules that come in various shapes, such as polymeric micelles and solid nanoparticles [33]. Like other nanocarriers, the surface of NP can be conjugated with various moieties employing the active functional groups of polymers. The development of polymeric NPs has specifically made use of biocompatible synthetic polymers like poly (vinylpyrrolidone), poly-(lactic-co-glycolic acid), poly-(L-lysine), poly-(malic acid), poly-(L-glutamic acid) and poly-(aspartame), and natural polymers like cellulose, alginate, gelatin, and chitosan [34]. Recently, significant effort has been made to create polymer-based targeted nanomedicines to effectively treat atherosclerosis. The following is a list of some of the developments. Different polymers used in the development of nanoparticles are shown in fig. 2.

Fig. 2: Different polymers are used in the development of nanoparticles

Poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid)

Poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) is a biocompatible and biodegradable polymer. Multiple compounds, including hydrophilic, hydrophobic macromolecules or macromolecules, have been used with PLGA in various drug delivery systems. They can regulate the release of medications as PLGA is FDA-approved and used in CVD drug delivery studies and other drug delivery investigations. These studies focus on employing PLGA NPs to deliver the cargo to atherosclerotic lesions spatially and temporally, and some of their applications are addressed [35].

To produce paclitaxel-loaded PLGA NPs, Feng et al. used the solvent extraction/evaporation method using emulsifiers such as d-α-tocopheryl polyethylene glycol 1000 succinate (TPGS) and Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA). Comparing NPs manufactured with TPGS emulsifier to plain medicines and PVA emulsified NPs after 6 h of cellular absorption revealed higher drug encapsulation, cytotoxicity, and cellular uptake [36].

In a different study, Golub et al. created an injectable containing PLGA NPs that were VEGF-encapsulated and had a controlled release system through a modified double W/O/W emulsion. They then employed this injectable to stimulate angiogenesis. According to the study, continuous-release therapy is more effective at treating atherosclerosis than pure vasculogenic protein delivery at lower overall dosages [37].

By encapsulating PLGA in a lipid/apolipoprotein coating, Sanchez-Gaytan et al. created synthetic high-density lipoproteins-like nanoparticles (PLGA-HDL-NPs) that interacted cordially with monocytes and macrophages in the aorta. These PLGA-HDL NPs were stabilized with the attachment of Apo A-1 to target atherosclerosis plaque macrophages [38].

Chitosan

Chitosan is another popular natural biocompatible polymer. It is desirable for drug delivery applications due to its beneficial properties, including regulated and gradual drug release, improved solubility, stability, and low toxicity [39].

Yu et al. examined the effects of Chitosan microspheres (COS) on the stability of atherosclerotic plaque using mice with a condition known as apolipoprotein E deficiency (apoE-/-). They discovered that COS therapy could prevent high-fat diet-induced atherosclerosis, and further plaque stability in apo E-/-mice was developed.

According to Xiying et al., who also created a DNA vaccine for the prevention and attenuation of atherosclerosis, chitosan cholesteol esterase transfer protein nanoparticles (CETP NPs) were completely able to provoke anti-CETP and slow the process of atherosclerotic plaque formation in rabbits by controlling the plasma lipoprotein profile. As a result, they may perform as novel platforms for nasal drug/vaccine delivery systems [41].

Cellulose

Numerous materials include cellulose, a naturally occurring polymer[cotton, hemp, wood, wheat straw, flax, sugar beet, mulberry, bark, potato tubers, algae, ramie, cellulose whiskers, and cellulose nanofibers, are some of the different types of nano-cellulose [42]. A few distinguishing features of nano-cellulose include its geometrical dimensions and distinct morphology, crystalline structure, rheology, liquid crystalline behavior, orientation and alignment, mechanical reinforcement characters, barrier properties, surface chemical reactivity, lack of/minimal toxicity[43].

Li et al. conducted research employing poly(L-lactic acid) (PLLA) and cellulose acetate butyrate (CAB) as the vehicle for borneol to overcome obstacles such as low water solubility and sublimation in treating CVD. They created a 200-m-long composite film made of pure PLLA nanofibers and CAB-borneol. Due to their low porosity, PLLA-CAB nano-fibrous composite nonwoven membranes are a viable contender and a cutting-edge drug delivery system for CVDs. Drug analysis for CAB-borneol revealed that 80% of the drug remained in the film, more than 70% of borneol was released in the case of pure PLLA, and 70% of the drug stayed in the membrane in the case of PLLA-CAB combination [44].

Gelatin

Gelatin, because of its biodegradability and biocompatibility, which is generated from collagen, is frequently employed in pharmaceutical and medical applications. Gelatin is a good choice for drug delivery due to its increased physicochemical properties and ease of modification and cross-linking [45].

Zhang et al. delivered nitric oxide (NO) to vascular cells using gelatin-siloxane (GS) NPs to regulate the behavior of the cells and prevent restenosis. After 2 h of GS-NO NP determination utilizing Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) analysis, the human aortic smooth muscle cells (AoSMCs) were able to internalize the particles. The new GS-NO-NP inhibited the primary factors contributing to restenosis, such as the excessive proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells, by releasing nitric oxide under controlled conditions [46].

Vogt et al. created a nanofibrous matrix with the property of light-responsive NO release using gelatin. They functionalized the surface of the matrix with SNAP to achieve a light-controlled release characteristic. They continued by implying that the SNAP could release NO when exposed to light. Divalent metal ions were also removed, which improved the gelatin's ability to hold onto NO and created a finer, more porous structure [47].

Alginate

Alginates are linearly linked 1,4-glycosidic connections between β-D-mannuronic acid (M) and α-L-guluronic acid (G) residues. The composition and sequence of the G and M residues directly affect the characteristics of alginates. The physicochemical properties of alginate make it a viable drug delivery vehicle, and its advantages for the production/encapsulation of numerous pharmaceuticals include non-toxicity, cost-effectiveness, high availability, biocompatibility, and non-immunogenicity. Alginate can also be chemically altered to increase specificity and efficiency in creating tailored nanoparticles [48].

Ruvinov et al. utilized the hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) along with an injectable alginate matrix possessing heparin-binding capabilities to make microbeads of affinity-binding alginate for treating ischemic CVDs. Finally, they discovered it offers excellent delivery and a milieu for temporary passive tissue repair support [49].

Metal-based nanoparticles

Widely used nano-sized metals have dimensions between 1 and 100 nm, and they can be altered by adding different chemical functional groups to make it easier for them to be conjugated with different therapeutic and targeted moieties (such as antibodies and aptamers). Magnetic iron oxide (Fe3 O4), gold, and silver nanoparticles, among other metals, have significantly affected medical sciences [50].

Colloidal gold or a suspension of nano-sized gold particles known as gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) have a reddish hue for particles less than 100 nm. However, the morphological shape and other physicochemical characteristics of AuNPs determine their properties and use. The unique optical characteristics of the AuNPs make them an excellent choice for various biomedical applications, including bio-imaging [51].

Roma-Rodrigues et al. created peptides and attached them to AuNPs to selectively interact with the angiogenesis cellular receptors. Following their synthesis, oligoethylene glycol (OEG) was used to functionalize and stabilize the gold nanoparticles before distinct peptides-activator, inhibitor, and scramble were attached to the OEG-AuNPs. It was discovered that inhibitor peptide-NP significantly reduced the number of new arterioles that formed around scramble peptide-NP. In contrast, activator peptide-NP significantly increased the production of new arterioles and showed that AuNPs have the potency as effective targeted DDSs, cause neo-vascularization, and improve CVDs [52].

AgNPs(Silver nanoparticles) are used more frequently in the biomedical industry. They comprise Ag particles with nano-sizes ranging between 1 and 100 nm. AgNPs stand out among other nano-materials for molecular labelling due to their huge effective scattering cross-section and potential for usage in surface plasmon resonance (SPR) [53].

When AgNPs (Silver nanoparticles) and rosuvastatin were compared for their effects on hyperlipidemic rats, Al-Dujaili et al. discovered that AgNPs significantly reduced endothelin and serum levels of obestatin compared to rosuvastatin [54].

Shi et al. concluded that AgNPs accelerate the onset of atherosclerosis by causing endothelial damage and through activation of IKK/NF-B; endothelial dysfunction happens in their study of the toxicity and effects of EC injury [55].

Fe3 O4 and Fe2 O3, the superparamagnetic and paramagnetic forms of iron (III) oxide, respectively, are found in nature. Superparamagnetic metal oxide NPs (SPIONs), with their biocompatibility, ultrafine size, and magnetic characteristics, are prime candidates for several biological applications. They have been used in targeted drug administration, imaging, hyperthermia, gene therapy, stem cell tracking, molecular/cellular tracking, magnetic separation technologies like quick DNA sequencing and enhanced resolution contrast agents for MRI. Inflammation, cancer, diabetes, and atherosclerosis can all be detected early [56].

To determine the impact of Ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide (USPIO) nanoparticles on the cardiovascular system and thrombosis, Nemmar et al. [57] undertook evaluation research. They found that the administration of USPIO increases plasma PAI-1, induces platelet aggregation in vitro, and stimulates the prothrombotic effect in the venules and arterioles in vivo. Moreover, particles raised plasma levels of troponin-I, LDH (lactate dehydrogenase), and CK-MB isoenzyme (creatine phosphokinase-MB), but USPIO lowered prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (PTT). These particles also elevated oxidative stress indicators in the heart, such as lipid peroxidation, ROS, and superoxide dismutase activity. Administering USPIO may not be the most effective targeting strategy for treating and diagnosing CVD overall because of its detrimental effects on thrombosis, DNA integrity, and cardiac oxidative stress. On the other hand, Xiong et al. [58] suggested Fe2 O3 NPs as a possibly helpful approach to treat CVD after reporting that Fe2 O3 NPs demonstrate no substantial toxicity on normal cardiomyocytes.

Zheng et al. synthesized Platinum nanoparticles (PtNPs) to function as antioxidants on microfluidic chips that simulate blood vessels. Under hyperlipidemic, hyperglycemic, and proinflammatory conditions, these nanoparticles showed superoxide dismutase (SOD)-like activities, scavenged reactive oxygen species (ROS), and strengthened cell-cell junctions. They presented PtNPs as a potential antioxidant carrier representing an exciting new therapeutic option for vascular disorders, including atherosclerosis [59].

Diagnostic modalities in lipid-based nanotheranostics

Imaging techniques for atherosclerosis diagnosis

Atherosclerosis is a slowly progressing ailment in which blood cells, fat, cholesterol, and other materials accumulate in the arteries to create a plaque. This constriction of the arteries lowers the amount of oxygen-rich blood that reaches the body's essential organs. Traditionally, clinical studies have concentrated on measuring the amount of plaque-induced stenosis; however, it is now known that the plaques that cause thrombus development might not be the ones that are most invasive on the arterial lumen. Because statins affect the content of the plaque without appreciably reducing its size or stenosis, angiograms, and statin studies have shown a dissociation between the degree of stenosis and clinical results. With potential clinical uses, novel imaging modalities such as PET, MRI, and ultrasound provide insights into plaque characteristics. Other biomedical imaging techniques include optical imaging, computed tomography, single-photon emission computed tomography, two-photon excited fluorescence, and photoacoustic imaging.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

MRI shows high resolution, and it has no depth limit. Also, it doesn’t require any radiation and can generate excellent soft tissue contrast (micrometres). High-risk morphological plaque features such as intra-plaque hemorrhage (IPH), thin fibrous caps, and large lipid-rich/necrotic core (LR/NC) can be identified by using MRI. High-resolution MRI can assess the lumen while assessing the plaque burden and differentiating plaque components in a non-invasive and accurate manner. Thus, it has emerged as the leading non-invasive imaging modality of atherosclerosis disease [60].

Nandwana et al. developed a magnetic nanostructure resembling High-Density Lipoprotein (HDL-MNS) for detecting, preventing, and treating atherosclerosis [61]. Phospholipids and Apo A-1 are coated with iron oxide magnetic nano-structures to mimic nature. High-density lipoprotein-MNS has an effective MRI contrast, and these particles show cholesterol efflux values likely to natural HDL at 4.8%.

(SLN) loaded with Ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxides (USPIOs) and the medication prostacyclin, created by Ouzmil et al. [62]. This article inhibited platelet aggregation and showed a 2.6-fold greater MRI contrast than clinically used superparamagnetic agents.

Wu. Y. et al. created aniron oxide nanoparticle by coating cerium oxide (FeO3@CeO2 NP) and Chit-FeO3@CeO2 NP(chitosan nano-cocktail comprising both CeO2and FeO3) for the clearance of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in inflamed macrophages [63, 64]. Cerium oxide is exploited as regenerative anti-ROS capability when Ce shifts between the Tri valence and tetravalence states. Cerium oxide and iron oxide were used as effective contrasting agents, and chitosan was used as a carrier [65, 66].

Another study by Wu Y et al. [67] created nanocomposites employing layered double hydroxide as carriers containing CeO2 and Fe3O4 and found that they effectively quenched ROS while producing a strong MRI signal. Additionally, fumagillin was created and linked to paramagnetic perfluorocarbon nanoparticles for targeted drug administration and improved MRI signals. According to these results, paramagnetic perfluorocarbon nanoparticles have a lower MRI sensitivity than iron oxide nanoparticles [68].

Fluorescence-based theranostic nanoparticles for atherosclerosis

Fluorescent chemicals are another frequently used tool for locating and identifying atherosclerotic lesions. Inflammatory macrophages contribute to atherosclerosis by forming plaques, enhancing the necrosis core, and weakening the fibrous cap. As a result, medicines t targeting inflammatory macrophages may also be a successful approach for atherosclerosis [69]. Recent research has demonstrated the viability of treating inflammatory macrophages with near-infrared light by activating nano-materials.

Lu and his group created photodynamic selenium nanoparticles (Se NPs) that target inflamed macrophages by conjugating chitosan (CS) with Rose Bengal (RB) (the photosensitizer), selenium (Se) and glutathione (GSH), resulting in RB-CS-GDH as the primary coating layer. The layer was then recoated with the carbonyl group from folic acid (FA) and hyaluronic acid (HA) covalently coupled with EDA to form HA-EDA-FA. HA and FA were ligands to bind CD44 and folate receptor-β[FR-β] on the surface of the inflamed macrophages. Selenium nanoparticles reduced inflammation by lowering the amounts of H2O2 and activated macrophages by converting H2O2 to O2. According to the study, LDL-stimulated macrophages provide stronger signals to RB than unstimulated macrophages, and these nanoparticles do not affect the non-active macrophages [70].

Yi et al. loaded chlorin e6 with dextran sulfate deoxycholic acid to develop a photosensitizer nanomaterial (DS-DOCA). Methyl thiazolyl tetrazolium (MTT) was used to investigate the cytotoxicity of Ce6/DS-DOCA-treated nano-material, and the results showed that after 2 min of laser irradiation, 80% of treated macrophages died compared to 20% of untreated macrophages [71].

By utilizing curcumin as a photosensitizer and oHA-TKL-Fc named HASF [oligomeric hyaluronic acid-2´-[propane-2,2-diyllbls (thio)-diacetic-acl-hydroxymethyl ferrocene] an amphiphilic carrier material, a nanomicelle was prepared [HASF@Cur micelles] to lower ROS in macrophages, Hou et al. created a nanogel. When administered to atherosclerotic rat models, HASF@Cur produced fewer lesions and greater fluorescence in macrophages. The fluorescence of curcumin allowed for the detection of the nanoparticles. According to this study, curcumin has potential applications as an imaging agent and an anti-ROS medication. The research, however, could not provide a clear explanation of how curcumin affects macrophages [72].

Kosuge et al. (73) created a single-walled carbon nanotube (SWNT) modified with Cy5.5 dye for performing NIR imaging and photothermal ablation of inflamed cells. Studies have revealed that SWNT can glow and photothermally destroy vascular macrophages. Ex vivo thermal ablation tests and confocal imaging demonstrated SWNT's capacity to induce macrophage death [73].

Marrache et al. and Sun et al. discussed two alternative quantum dot models separately. They used triphenyl phosphonium [TPP], the Apo A-1 mimetic 4F peptide (four phenylalanine residues), and the Q-dot® 705 ITKTM amino PEG Q-dot core to create a synthetic HDL nanoparticle for detecting and treating atherosclerosis [74]. Targeted nanoparticles in ApoE (-/-) mice produced a fluorescent signal in the plaques that was three times stronger than non-targeted nanoparticles. To transport the hirulog peptide, Sun et al. created a unique, trifunctional simian virus 40-based nanoparticle [75]. To target P32 protein on macrophages, the nano-system was also filled with NIR Q-dots and labeled with cyclic peptides. The resulting SV40 nanoparticles in Apo-E mutant mice were highly selective in their ability to deliver hirulog to atherosclerotic plaques.

Computed tomography (CT)

In their study, Qin et al. [76] developed Au-nanorods as a basis for inflammatory macrophage theranostics. Macrophages were observed using micro-CT imaging, and higher concentrations of Au-nanorod were found to produce more signals. Apo E knockout mice underwent in vivo heat treatment, and when the drug was administered intravenously, there was an improvement in CT power in the dilated femoral arteries. This suggests that the drug has potential as an alternative nontoxic therapy for atherosclerosis. Moreover, the ability of gold computed tomography agents to diagnose vascular disease was demonstrated. This suggests that the synthesized Au-nanorods can be useful tools for diagnosing and treating arthritis, providing new perspectives in the treatment of arthritis [77].

Near-infrared fluorescence imaging

McCarthy et al. [78] developed magnetic fluorescent nanoparticles for atherosclerosis and inflammatory theranostics. Meso-tetra(m-hydroxyphenyl) chlorin (THPC) and Alexa Fluor 750 were utilized to redesign dextran-coated iron oxide nanoparticles, which were then employed to treat inflammatory cells with near-infrared fluorescence phototoxically. Near-infrared imaging experiments showed that high numbers of macrophages and foam cells could cause THPC-based nanomaterials to congregate in particular areas. Research suggests that atherosclerotic vascular disorders might be treated with this therapeutic nano-material. Atherosclerosis can be treated using hydrophilic photosensitizers based on magnetic nanoparticles and 5-(4-carboxyphenyl)-10,15,20-triphenyl2,3-dihydroxychlorin (TPC) through the induction of macrophage. TPC nanoparticles were found to kill human macrophages up to 100% in in vitro studies [79].

Photoacoustic-based nanotheranostic particles

Gao et al. attached a monoclonal antibody to copper sulphur to target the transient receptor potential cation channel. CuS-TRPV1 provided a significant photoacoustic signal of the heart's vascular system during imaging. The atherosclerotic accumulation was dramatically reduced with IV injection of the nano-materials after 12 w [80].

Targeting strategies for atherosclerotic plaques

Passive targeting

Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory disease that initiates with endothelial cell (EC) activation [81]. Chemical, immunological, and mechanical interactions in the artery wall trigger this activation, causing an increase in the expansion of molecules such as VCAM-1, ICAM-1, E-selectin, and P-selectin [82]. These adhesion molecules are essential for the differentiation of intimal macrophages and the adherence of monocytes. The functionalized ECs and the heightened presence of adhesion molecules enable the passive penetration of nanoparticles selectively into ECs. The crucial physiological change facilitating the accumulation of passively targeted NPs is increased vascular permeability in the inflamed area. Under normal circumstances, endothelial cells act as barriers with tight junctions, maintaining the body's balance. The EPR effect, resulting from the change in endothelial cell phenotype, leads to an increased passive accumulation of large-molecular-weight macromolecules and nanoparticles (NPs) [83]. Recent studies have demonstrated that cyclodextrin NPs exhibit a buildup in atherosclerotic plaques compared to non-targeting cyclodextrin molecules [83]. However, this effect has not been extensively explored in various vascular disorders. The cyclodextrin polymer-based NPs, with a diameter of approximately 10 nm, have the advantage of prolonged circulation time and bypass the renal clearance system, enabling them to aggregate at the site of atherosclerotic plaques.

On the other hand, the bloodstream rapidly clears cyclodextrin. These findings suggest that nanoparticle formulations could effectively target the lesion area through a passive targeting strategy, leveraging phenotypic changes in leaky junctions caused by activated endothelial cells and the prolonged circulation period of the NPs. Targets and contrast agents for molecular imaging of atherosclerosis are shown in table 2.

Active targeting

The buildup of inflammatory, lipid-rich plaques and cholesterol particles within the arterial walls is known as atherosclerosis, the main cause of cardiovascular disease. Like the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, these plaques cause inflammation in the endothelial cells, which increases their susceptibility to leakage. As a result, nanoparticles (NPs) have great potential for detecting atherosclerosis and passive medication administration [85]. Based on the vessel wall permeability, NPs have already shown their potential to target atherosclerotic plaques passively; however, active targeting is projected to be even more successful at penetrating the plaque and capturing target cells [86].

Various ligands, such asVCAM-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), interleukin-10 (IL-10), and E-selectin, have been employed in active targeting strategies to combat atherosclerosis. The main objective is to increase the drugs' delivery and retention time and reduce inflammation and plaque size. The use of active-targeted nanoparticles (NPs) has shown promising results with higher accumulation rates within the plaques and considerably extended retention time, suggesting the potential for improved therapeutic efficacy [87-91].

Inflamed cells within the plaques have been actively targeted using hyaluronic acid (HA) nanoparticles. HA plays a crucial role in the inflammatory process by facilitating interactions with immune cells [92]. Nano formulated HA can also be a therapeutic agent, showing promising anti-inflammatory effects [93]. Therefore, HA plays a pivotal role in achieving the necessary NP size to enable passive accumulation, actively target specific cells through interactions, and act as a therapeutic agent with athero protective properties.

An immunoglobulin superfamily glycoprotein, VCAM-1, is expressed on activated endothelial cells, macrophages, and smooth muscle cells (SMCs) [94]. Atherosclerotic plaques and inflammation are both impacted by it. The VHPK peptide (VHPKQHR) has been mostly used for targeting and imaging atherosclerosis lesions because of its affinity and high specificity to VCAM-1 on the endothelium in the plaque [95].

Kheirolomoom et al. created lipid nanoparticles incorporating a VCAM-1 targeted peptide to target the atherosclerosis plaque on ECs [96]. Using MRI, VHPKQHR peptide-compromised NPs have been utilized to diagnose atherosclerosis non-invasively. The results indicated that targeting the atherosclerotic plaque with VHPKQHR peptide conjugation may be an excellent strategy, and VHPK-conjugated Poly (β-amino ester) nanoparticles were utilized to deliver anti-miR-712 to inflamed endothelial cells, resulting in the downregulation of plaque development. Nanoparticles showed an increased therapeutic effect in the mouse model where the atherosclerotic plaque was developed. The conjugation of VCAM-1-targeting peptide was investigated and proved a promising and efficient strategy against inflamed ECs.

Another active targeting technique is using biomimetic particles to target atherosclerotic plaque. Rapamycin-loaded NPs [97] with leukosomes with a leukocyte surface membrane were employed to lessen vascular inflammation. Following rapamycin-loaded with the leukosomenanoparticle injection, there was a reduction in the number of proliferating macrophages in the aorta as well as the levels of MCP-1, IL-1b, and MMP (matrix metalloproteinases) activity. To generate the magnetic nanoclusters, leukocyte membrane fragments were utilized, which were then loaded with the anti-inflammatory medication simvastatin [98]. This study demonstrated the ability of biomimetic NPs to target atherosclerosis. These nanoparticles demonstrated an effective anti-atherosclerotic effect by reducing the amount of inflammation and oxidative stress and encouraging cholesterol efflux.

To create a direct interface between the nanoparticles and activated endothelial cells, additional biomimetic liposomes were created utilizing a platelet membrane (platelet-mimetic hybrid liposomes) [99]. To cling to activated endothelial cells, platelets play a crucial role in the onset of atherosclerosis. These findings suggested that platelet membrane fragments and leukocytes can be an effective targeting method against activated endothelial cells. Platelet-mimetic hybrid liposomes significantly increased plaque accumulation and plaque penetration.

As previously reported, the cyclic oligosaccharide 2-hydroxypropyl-cyclodextrin produces higher cholesterol crystal solubility, reducing atherosclerosis and making cyclodextrin-based NPs a viable targeting molecule for targeted CVD treatment. Because of the hydrophobic cavity, Cyclodextrin was employed as a hydrophobic drug carrier to reduce plaque size and facilitate regression. Simvastatin, a common cholesterol-lowering medication that lowers the risk of CVDs, was placed into the hydrophobic cavity of the cyclodextrin. Cargo-switching after the lipid coating and homogenizing to prepare nanoparticles. At the site of the atherosclerotic plaque, they demonstrated the ability to swap their cargo, and this boosted the therapeutic efficacy at the plaque site because of its selective statin release mechanism. These findings suggested that cyclodextrin could be employed as a potential atherosclerotic plaque-targeting substance [100, 101].

Therapeutic modalities in lipid-based nanotheranostics

Anti-inflammatory agents

Many anti-inflammatory drugs have been developed to inhibit plaque inflammation because macrophage accumulation appears to be a key event contributing to the buildup of atherosclerotic plaques within the arterial vessel walls. One of the drug classes is corticosteroids, and apart from their poor pharmacokinetic profile, they can trigger rapid anti-inflammatory responses. Lobatto et al. incorporated glucocorticoids into long-circulating PEG-liposomes to enhance their circulation half-life and enable them to extravasate from the circulation and accumulate in the atherosclerotic lesions. Their results showed efficient delivery of these liposomes, with evident therapeutic efficacy evaluated by FDG-PET/CT within two days, lasting up to two weeks [102].

Anti-angiogenic agents

Winter et al. developed multifunctional perfluorocarbon NPs to target the neovascular vasa vasorum of the plaque using a peptidomimetic vitronectin antagonist, and these NPs contain gadolinium, which helps for MRI imaging and the anti-angiogenic drug ‘fumagillin.’ The results showed that paramagnetic NPs loaded with anti-angiogenic factors can inhibit plaque angiogenesis and reduce size. At the same time, molecular imaging can be used as a non-invasive interpretation of therapeutic efficacy [103].

Statins and lipid-lowering agents

In clinical practice, to assess statin treatment in dyslipidemic people with high risk, in addition to the dose-dependent effects of atorvastatin on carotid plaques, USPIO has been used. The continuation of high-dose statin treatment for 12 w reduced USPIO uptake in carotid plaques, while low-dose treatment had no potential effect. Tang et al. observation is one of the first clinical examples of nanoparticle-assisted noninvasive imaging for pharmacological therapy evaluation in patients with atherosclerosis [104].

Thrombolytic drugs

A recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA) was covalently conjugated to polyacrylic acid-coated nanoparticles (NPs) by MA et al. to study the utilization of iron oxide NPs for magnetically targeted administration of thrombolytic medicines. This tactic runs the danger of causing the primary adverse impact of a rtPA, intracerebral hemorrhage, because rtPA selective delivery is not present. The thrombolytic conjugate demonstrated a five-fold higher efficacy than free rtPA in the in vivo investigation employing a rat hind limb ischemia model [105].

CONCLUSION

The review highlights passive and active targeting mechanisms and microtargeting tactics in these nanotheranostics. Increasing medication distribution to lymph nodes, enhancing therapeutic efficacy, and decreasing off-target effects are the primary objectives of these approaches. There has been an evolution in the treatment of atherosclerosis due to the therapeutic alternatives available in lipid-based nanotheranostics, which include antioxidants, lipid-lowering medicines, antioxidants, and complex gene treatments. This is a comprehensive strategy that can both prevent the disease from developing and reduce its existing impact. It is the physical manifestation of possibility.

ABBREVIATIONS

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| RNS | Reactive nitrogen species |

| SLNs | Solid lipid nanoparticles, |

| NLCs | Nanostructured lipid carriers |

| LMWH | Low molecular weight heparin |

| DVT | Deep vein thrombosis |

| PE | Pulmonary embolism |

| PLGA | Poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) |

| TPGS | D-tocopheryl polyethylene glycol 1000 succinate |

| PVA | Polyvinyl alcohol |

| COS | Chitosan oligosaccharides |

| CNC | Cellulose nanocrystals |

| CNF | Cellulose Nanofibrils |

| NFC | Nano Fibrillated Cellulose |

| BCN | Bacterial Cellulose Nanocomposites |

| SSA | Specific surface area |

| PLLA | Poly (L-lactic acid) |

| CAB | Cellulose acetate-butyrate |

| SNAP | S-nitroso-N-acetyl-D-penicillamine |

| USPIO | Ultra-small superparamagnetic iron oxide |

| PAI-1 | Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 |

| PT | Prothrombin time |

| PTT | Partial thromboplastin time |

| EDA | Ethylenediamine |

| rtPA | Recombinant Tissue Plasminogen Activator |

| HA | Hyaluronic Acid |

| EPR | Enhanced Permeability And Retention |

| SWCN | Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| HDL-MNS | Magnetic nanostructure resembling High-Density Lipoprotein |

| CVD | Cardiovascular Disease |

| CETP NPs | Cholesteol Esterase Transfer Protein Nanoparticles |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Grants from the JSS-AHER DBT BUILDER supported our study: Sanction order No: BT/INF/22/SP43045/2021.

The authors would like to thank the Department of Science and Technology-Fund for Improvement of Science and Technology Infrastructure (DST-FIST) and Promotion of University Research and Scientific Excellence (DST-PURSE) for the facilities provided for conducting the research.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTS

Not applicable

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization, K. A., G. K., and I. N.; writing-original draft preparation, M. D, I. N.; supervision, G. K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

Martel J. How heart disease is diagnosed. Healthline; 2021 Oct 21. Available from: https://www.healthline.com/health/how-heart-disea. [Last accessed 06 May 2024].

Patel RP, Moellering D, Murphy Ullrich J, Jo H, Beckman JS, Darley Usmar VM. Cell signaling by reactive nitrogen and oxygen species in atherosclerosis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;28(12):1780-94. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00235-5, PMID 10946220.

Chinetti Gbaguidi G, Colin S, Staels B. Macrophage subsets in atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015;12(1):10-7. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2014.173, PMID 25367649.

Ross R. Atherosclerosis an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(2):115-26. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400207, PMID 9887164.

Owen DR, Lindsay AC, Choudhury RP, Fayad ZA. Imaging of atherosclerosis. Annu Rev Med. 2011;62:25-40. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-041709-133809, PMID 21226610.

Muthu MS, Leong DT, Mei L, Feng SS. Nanotheranostics application and further development of nanomedicine strategies for advanced theranostics. Theranostics. 2014;4(6):660-77. doi: 10.7150/thno.8698, PMID 24723986.

Zhao J, Mi Y, Feng SS. siRNA-based nanomedicine. Nanomedicine (Lond). 2013;8(6):859-62. doi: 10.2217/nnm.13.73, PMID 23730692.

Lammers T, Aime S, Hennink WE, Storm G, Kiessling F. Theranostic nanomedicine. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44(10):1029-38. doi: 10.1021/ar200019c, PMID 21545096.

Muthu MS, Leong DT, Mei L, Feng SS. Nanotheranostics application and further development of nanomedicine strategies for advanced theranostics. Theranostics. 2014;4(6):660-77. doi: 10.7150/thno.8698, PMID 24723986.

Wu Y, Vazquez Prada KX, Liu Y, Whittaker AK, Zhang R, Ta HT. Recent advances in the development of theranostic nanoparticles for cardiovascular diseases. Nanotheranostics. 2021;5(4):499-514. doi: 10.7150/ntno.62730, PMID 34367883.

Majzoub RN, Ewert KK, Safinya CR. Cationic liposome nucleic acid nanoparticle assemblies with applications in gene delivery and gene silencing. Philos Trans A Math Phys Eng Sci. 2016;374(2072):20150129. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2015.0129, PMID 27298431.

Safinya CR, Ewert KK, Majzoub RN, Leal C. Cationic liposome nucleic acid complexes for gene delivery and gene silencing. New J Chem. 2014;38(11):5164-72. doi: 10.1039/C4NJ01314J, PMID 25587216.

Zhang YY, Chen JM. Existing problems and strategies in liposome mediated nucleic acid delivery. Yao Xue Xue Bao. 2011;46(3):261-8. PMID 21626778.

Joner M, Morimoto K, Kasukawa H, Steigerwald K, Merl S, Nakazawa G. Site-specific targeting of nanoparticle prednisolone reduces in stent restenosis in a rabbit model of established atheroma. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28(11):1960-6. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.170662, PMID 18688017.

Calin M, Stan D, Schlesinger M, Simion V, Deleanu M, Constantinescu CA. VCAM-1 directed target sensitive liposomes carrying CCR2 antagonists bind to activated endothelium and reduce adhesion and transmigration of monocytes. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2015;89:18-29. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2014.11.016, PMID 25438248.

Homem De Bittencourt Jr PI, Lagranha DJ, Maslinkiewicz A, Senna SM, Tavares AM, Baldissera LP. Lipocardium: endothelium directed cyclopentenone prostaglandin-based liposome formulation that completely reverses atherosclerotic lesions. Atherosclerosis. 2007;193(2):245-58. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.08.049, PMID 16996518.

Hosseini H, Li Y, Kanellakis P, Tay C, Cao A, Tipping P. Phosphatidylserine liposomes mimic apoptotic cells to attenuate atherosclerosis by expanding polyreactive IgM producing B1a lymphocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 2015;106(3):443-52. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvv037, PMID 25681396.

Van Der Valk FM, Van Wijk DF, Lobatto ME, Verberne HJ, Storm G, Willems MC. Prednisolone-containing liposomes accumulate in human atherosclerotic macrophages upon intravenous administration. Nanomedicine. 2015;11(5):1039-46. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2015.02.021, PMID 25791806.

Homem De Bittencourt PI, Lagranha DJ, Maslinkiewicz A, Senna SM, Tavares AM, Baldissera LP. Lipocardium: endothelium directed cyclopentenone prostaglandin based liposome formulation that completely reverses atherosclerotic lesions. Atherosclerosis. 2007;193(2):245-58. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.08.049, PMID 16996518.

Eskandani M, Nazemiyeh H. Self-reporter shikonin act loaded solid lipid nanoparticle: formulation physicochemical characterization and geno/cytotoxicity evaluation. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2014;59:49-57. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2014.04.009, PMID 24768857.

Ezzati Nazhad Dolatabadi J, Omidi Y. Solid lipid based nanocarriers as efficient targeted drug and gene delivery systems. Trac Trends in Analytical Chemistry. 2016;77:100-8. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2015.12.016.

Kulandaivelu K, Mandal AK. Positive regulation of biochemical parameters by tea polyphenol encapsulated solid lipid nanoparticles at in vitro and in vivo conditions. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2016;10(6):419-24. doi: 10.1049/iet-nbt.2015.0113, PMID 27906144.

Paliwal R, Paliwal SR, Agrawal GP, Vyas SP. Biomimetic solid lipid nanoparticles for oral bioavailability enhancement of low molecular weight heparin and its lipid conjugates: in vitro and in vivo evaluation. Mol Pharm. 2011;8(4):1314-21. doi: 10.1021/mp200109m, PMID 21598996.

Gao Y, Gu W, Chen L, Xu Z, Li Y. The role of daidzein-loaded sterically stabilized solid lipid nanoparticles in therapy for cardio-cerebrovascular diseases. Biomaterials. 2008;29(30):4129-36. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.07.008, PMID 18667234.

Hormann K, Zimmer A. Drug delivery and drug targeting with parenteral lipid nanoemulsions a review. J Control Release. 2016;223:85-98. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.12.016, PMID 26699427.

Souto EB, Nayak AP, Murthy RS. Lipid nanoemulsions for anti-cancer drug therapy. Pharmazie. 2011;66(7):473-8. PMID 21812320.

Tavares ER, Freitas FR, Diament J, Maranhao RC. Reduction of atherosclerotic lesions in rabbits treated with etoposide associated with cholesterol-rich nanoemulsions. Int J Nanomedicine. 2011;6:2297-304. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S24048, PMID 22072867.

Bulgarelli A, Leite Jr AC, Dias AA, Maranhao RC. Anti-atherogenic effects of methotrexate carried by a lipid nanoemulsion that binds to LDL receptors in cholesterol-fed rabbits. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2013;27(6):531-9. doi: 10.1007/s10557-013-6488-3, PMID 24065615.

Leite AC, Solano TV, Tavares ER, Maranhao RC. Use of combined chemotherapy with etoposide and methotrexate both associated to lipid nanoemulsions for atherosclerosis treatment in cholesterol fed rabbits. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2015;29(1):15-22. doi: 10.1007/s10557-014-6566-1, PMID 25672520.

Beloqui A, Solinis MA, Rodriguez Gascon A, Almeida AJ, Preat V. Nanostructured lipid carriers: promising drug delivery systems for future clinics. Nanomedicine. 2016;12(1):143-61. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2015.09.004, PMID 26410277.

Zhang WL, Gu X, Bai H, Yang RH, Dong CD, Liu JP. Nanostructured lipid carriers constituted from high-density lipoprotein components for delivery of a lipophilic cardiovascular drug. Int J Pharm. 2010;391(1-2):313-21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2010.03.011, PMID 20214958.

Zhang W, He H, Liu J, Wang J, Zhang S, Zhang S. Pharmacokinetics and atherosclerotic lesions targeting effects of tanshinone IIA discoidal and spherical biomimetic high density lipoproteins. Biomaterials. 2013;34(1):306-19. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.09.058, PMID 23069716.

Banik BL, Fattahi P, Brown JL. Polymeric nanoparticles: the future of nanomedicine. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol. 2016;8(2):271-99. doi: 10.1002/wnan.1364, PMID 26314803.

Lim EK, Chung BH, Chung SJ. Recent advances in pH-sensitive polymeric nanoparticles for smart drug delivery in cancer therapy. Curr Drug Targets. 2018;19(4):300-17. doi: 10.2174/1389450117666160602202339, PMID 27262486.

Kapoor DN, Bhatia A, Kaur R, Sharma R, Kaur G, Dhawan S. PLGA: a unique polymer for drug delivery. The Deliv. 2015;6(1):41-58. doi: 10.4155/tde.14.91, PMID 25565440.

Feng SS, Zeng W, Teng Lim Y, Zhao L, Yin Win K, Oakley R. Vitamin E TPGS-emulsified poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles for cardiovascular restenosis treatment. Nanomedicine (Lond). 2007;2(3):333-44. doi: 10.2217/17435889.2.3.333, PMID 17716178.

Golub JS, Kim YT, Duvall CL, Bellamkonda RV, Gupta D, Lin AS. Sustained VEGF delivery via PLGA nanoparticles promotes vascular growth. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298(6):H1959-65. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00199.2009, PMID 20228260.

Sanchez Gaytan BL, Fay F, Lobatto ME, Tang J, Ouimet M, Kim Y. HDL-mimetic PLGA nanoparticle to target atherosclerosis plaque macrophages. Bioconjug Chem. 2015;26(3):443-51. doi: 10.1021/bc500517k, PMID 25650634.

Masotti A, Ortaggi G. Chitosan micro and nanospheres: fabrication and applications for drug and DNA delivery. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2009;9(4):463-9. doi: 10.2174/138955709787847976, PMID 19356124.

Yu Y, Luo T, Liu S, Song G, Han J, Wang Y. Chitosan oligosaccharides attenuate atherosclerosis and decrease non-HDL in ApoE−/− mice. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2015;22(9):926-41. doi: 10.5551/jat.22939, PMID 25843117.

Yuan X, Yang X, Cai D, Mao D, Wu J, Zong L. Intranasal immunization with chitosan/pCETP nanoparticles inhibits atherosclerosis in a rabbit model of atherosclerosis. Vaccine. 2008;26(29-30):3727-34. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.04.065, PMID 18524427.

Trache D, Hussin MH, Haafiz MK, Thakur VK. Recent progress in cellulose nanocrystals: sources and production. Nanoscale. 2017;9(5):1763-86. doi: 10.1039/c6nr09494e, PMID 28116390.

Wang S, Lu A, Zhang L. Recent advances in regenerated cellulose materials. Prog Polym Sci. 2016;53:169-206. doi: 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2015.07.003.

Li L, Luo X, Leung PH, Law HK. Controlled release of borneol from nano-fibrous poly(L-lactic acid)/ cellulose acetate butyrate membrane. Text Res J. 2016;86(11):1202-9. doi: 10.1177/0040517515603812.

Yasmin R, Shah M, Khan SA, Ali R. Gelatin nanoparticles: a potential candidate for medical applications. Nanotechnol Rev. 2017;6(2):191-207. doi: 10.1515/ntrev-2016-0009.

Zhang QY, Wang ZY, Wen F, Ren L, Li J, Teoh SH. Gelatin siloxane nanoparticles to deliver nitric oxide for vascular cell regulation: synthesis cytocompatibility and cellular responses. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2015;103(3):929-38. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.35239, PMID 24853642.

Vogt C, Xing Q, He W, Li B, Frost MC, Zhao F. Fabrication and characterization of a nitric oxide releasing nanofibrous gelatin matrix. Biomacromolecules. 2013;14(8):2521-30. doi: 10.1021/bm301984w, PMID 23844781.

Ruvinov E, Cohen S. Alginate biomaterial for the treatment of myocardial infarction: progress translational strategies and clinical outlook: from ocean algae to patient bedside. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2016;96:54-76. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2015.04.021, PMID 25962984.

Ruvinov E, Leor J, Cohen S. The promotion of myocardial repair by the sequential delivery of IGF-1 and HGF from an injectable alginate biomaterial in a model of acute myocardial infarction. Biomaterials. 2011;32(2):565-78. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.097, PMID 20889201.

Manojkumar K, Sivaramakrishna A, Vijayakrishna K. A short review on stable metal nanoparticles using ionic liquids supported ionic liquids and poly(ionic liquids). J Nanopart Res. 2016;18(4):106. doi: 10.1007/s11051-016-3409-y.

Cao Milan R, Liz Marzan LM. Gold nanoparticle conjugates: recent advances toward clinical applications. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2014;11(5):741-52. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2014.891582, PMID 24559075.

Roma Rodrigues C, Heuer Jungemann A, Fernandes AR, Kanaras AG, Baptista PV. Peptide coated gold nanoparticles for modulation of angiogenesis in vivo. Int J Nanomedicine. 2016;11:2633-9. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S108661, PMID 27354794.

Abbasi E, Milani M, Fekri Aval S, Kouhi M, Akbarzadeh A, Tayefi Nasrabadi H. Silver nanoparticles: synthesis methods bio-applications and properties. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2016;42(2):173-80. doi: 10.3109/1040841X.2014.912200, PMID 24937409.

Al Dujaili AN, Al Shemeri MK. Effect of silver nanoparticles and rosuvastatin on endothelin and obestatin in rats induced by high fat diet. Res J Pharm Biol Chem Sci. 2016;7(3):1022-30.

Shi J, Sun X, Lin Y, Zou X, Li Z, Liao Y. Endothelial cell injury and dysfunction induced by silver nanoparticles through oxidative stress via IKK/NF-κB pathways. Biomaterials. 2014;35(24):6657-66. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.04.093, PMID 24818879.

El Sherbiny IM, Elbaz NM, Sedki M, Elgammal A, Yacoub MH. Magnetic nanoparticles based drug and gene delivery systems for the treatment of pulmonary diseases. Nanomedicine (Lond). 2017;12(4):387-402. doi: 10.2217/nnm-2016-0341, PMID 28078950.

Nemmar A, Beegam S, Yuvaraju P, Yasin J, Tariq S, Attoub S. Ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles acutely promote thrombosis and cardiac oxidative stress and DNA damage in mice. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2016;13(1):22. doi: 10.1186/S12989-016-0132-X, PMID 27138375.

Xiong F, Wang H, Feng Y, Li Y, Hua X, Pang X. Cardioprotective activity of iron oxide nanoparticles. Sci Rep. 2015;5:8579. doi: 10.1038/srep08579, PMID 25716309.

Zheng W, Jiang B, Hao Y, Zhao Y, Zhang W, Jiang X. Screening reactive oxygen species scavenging properties of platinum nanoparticles on a microfluidic chip. Biofabrication. 2014;6(4):045004. doi: 10.1088/1758-5082/6/4/045004, PMID 25215884.

Kramer CM, Anderson JD. MRI of atherosclerosis: diagnosis and monitoring therapy. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2007;5(1):69-80. doi: 10.1586/14779072.5.1.69, PMID 17187458.

Nandwana V, Ryoo SR, Kanthala S, McMahon KM, Rink JS, Li Y. High-density lipoprotein like magnetic nanostructures (HDL-MNS): theranostic agents for cardiovascular disease. Chem Mater. 2017;29(5):2276-82. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.6b05357.

Oumzil K, Ramin MA, Lorenzato C, Hemadou A, Laroche J, Jacobin Valat MJ. Solid lipid nanoparticles for image guided therapy of atherosclerosis. Bioconjug Chem. 2016;27(3):569-75. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.5b00590, PMID 26751997.

Wu Y, Yang Y, Zhao W, Xu ZP, Little PJ, Whittaker AK. Novel iron oxide cerium oxide core-shell nanoparticles as a potential theranostic material for ROS related inflammatory diseases. J Mater Chem B. 2018;6(30):4937-51. doi: 10.1039/c8tb00022k, PMID 32255067.

Wu Y, Zhang R, Tran HD, Kurniawan ND, Moonshi SS, Whittaker AK. Chitosan nano-cocktails containing both ceria and superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for reactive oxygen species related theranostics. ACS Appl Bio Mater. 2021;4(4):3604-18. doi: 10.1021/acsanm.1c00141.

Das S, Dowding JM, Klump KE, McGinnis JF, Self W, Seal S. Cerium oxide nanoparticles: applications and prospects in nanomedicine. Nanomedicine (Lond). 2013;8(9):1483-508. doi: 10.2217/nnm.13.133, PMID 23987111.

Jakupec MA, Unfried P, Keppler BK. Pharmacological properties of cerium compounds. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;153:101-11. doi: 10.1007/s10254-004-0024-6, PMID 15674649.

Ta HT, Dunstan DE, Dass CR. Anticancer activity and therapeutic applications of chitosan nanoparticles. In: Kim SK, Dass CR, editors. Chitin chitosan oligosaccharides and their derivatives: biological activities and applications. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2010. p. 271-84. doi: 10.1201/EBK1439816035-c21.

Liu Y, Wu Y, Zhang R, Lam J, Ng JC, Xu ZP. Investigating the use of layered double hydroxide nanoparticles as carriers of metal oxides for theranostics of ROS-related diseases. ACS Appl Bio Mater. 2019;2(12):5930-40. doi: 10.1021/acsabm.9b00852, PMID 35021514.

Cao Z, Li B, Sun L, Li L, Xu ZP, Gu Z. 2D layered double hydroxide nanoparticles: recent progress toward preclinical/clinical nanomedicine. Small Methods. 2020;4(2):1900343. doi: 10.1002/smtd.201900343.

Moore KJ, Tabas I. Macrophages in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Cell. 2011;145(3):341-55. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.04.005, PMID 21529710.

Lu KY, Lin PY, Chuang EY, Shih CM, Cheng TM, Lin TY. H2O2-depleting and O2-generating selenium nanoparticles for fluorescence imaging and photodynamic treatment of proinflammatory activated macrophages. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9(6):5158-72. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b15515, PMID 28120612.

Yi BG, Park OK, Jeong MS, Kwon SH, Jung JI, Lee S. In vitro photodynamic effects of scavenger receptor targeted photoactivatable nanoagents on activated macrophages. Int J Biol Macromol. 2017;97:181-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.01.037, PMID 28082222.

Hou X, Lin H, Zhou X, Cheng Z, Li Y, Liu X. Novel dual ROS-sensitive and CD44 receptor targeting nanomicelles based on oligomeric hyaluronic acid for the efficient therapy of atherosclerosis. Carbohydr Polym. 2020;232:115787. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115787, PMID 31952595.

Kosuge H, Sherlock SP, Kitagawa T, Dash R, Robinson JT, Dai H. Near infrared imaging and photothermal ablation of vascular inflammation using single walled carbon nanotubes. J Am Heart Assoc. 2012;1(6):e002568. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.112.002568, PMID 23316318.

Marrache S, Dhar S. Biodegradable synthetic high density lipoprotein nanoparticles for atherosclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(23):9445-50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301929110, PMID 23671083.

Sun X, Li W, Zhang X, Qi M, Zhang Z, Zhang XE. In vivo targeting and imaging of atherosclerosis using multifunctional virus like particles of simian virus 40. Nano Lett. 2016;16(10):6164-71. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b02386, PMID 27622963.

Qin JB, Peng ZY, Li B, Ye KC, Zhang YX, Yuan FK. Gold nanorods as a theranostic platform for in vitro and in vivo imaging and photothermal therapy of inflammatory macrophages. Nanoscale. 2015;7(33):13991-4001. doi: 10.1039/c5nr02521d, PMID 26228112.

Wu J, Niu S, Bremner DH, Nie W, Fu Z, Li D. A tumor microenvironment-responsive biodegradable mesoporous nanosystem for anti-inflammation and cancer theranostics. Adv Healthc Mater. 2020;9(2):e1901307. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201901307, PMID 31814332.

McCarthy JR, Jaffer FA, Weissleder R. A macrophage targeted theranostic nanoparticle for biomedical applications. Small. 2006;2(8-9):983-7. doi: 10.1002/smll.200600139, PMID 17193154.

Bagalkot V, Badgeley MA, Kampfrath T, Deiuliis JA, Rajagopalan S, Maiseyeu A. Hybrid nanoparticles improve targeting to inflammatory macrophages through phagocytic signals. J Control Release. 2015;217:243-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.09.027, PMID 26386437.

Gao W, Sun Y, Cai M, Zhao Y, Cao W, Liu Z. Copper sulfide nanoparticles as a photothermal switch for TRPV1 signaling to attenuate atherosclerosis. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):231. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02657-z.

Villa Roel N, Gu L, Fernandez Esmerats J, Kang DW, Kumar S, Jo H. Hypoxia inducible factor-1α inhibitor, PX-478, reduces atherosclerosis in vivo. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2020;40:A366.

Cybulsky MI, Gimbrone MA. Endothelial expression of a mononuclear leukocyte adhesion molecule during atherogenesis. Science. 1991;251(4995):788-91. doi: 10.1126/science.1990440, PMID 1990440.

Claesson Welsh L, Dejana E, McDonald DM. Permeability of the endothelial barrier: identifying and reconciling controversies. Trends Mol Med. 2021;27(4):314-31. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2020.11.006, PMID 33309601.

Kim H, Han J, Park JH. Cyclodextrin polymer improves atherosclerosis therapy and reduces ototoxicity. J Control Release. 2020;319:77-86. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2019.12.021, PMID 31843641.

Wang Y, Li L, Zhao W, Dou Y, An H, Tao H. Targeted therapy of atherosclerosis by a broad spectrum reactive oxygen species scavenging nanoparticle with intrinsic anti-inflammatory activity. ACS Nano. 2018;12(9):8943-60. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b02037, PMID 30114351.

Lobatto ME, Calcagno C, Millon A, Senders ML, Fay F, Robson PM. Atherosclerotic plaque targeting mechanism of long-circulating nanoparticles established by multimodal imaging. ACS Nano. 2015;9(2):1837-47. doi: 10.1021/nn506750r, PMID 25619964.

Iiyama K, Hajra L, Iiyama M, Li H, DiChiara M, Medoff BD. Patterns of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression in rabbit and mouse atherosclerotic lesions and at sites predisposed to lesion formation. Circ Res. 1999;85(2):199-207. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.2.199, PMID 10417402.

Bruckman MA, Jiang K, Simpson EJ, Randolph LN, Luyt LG, Yu X. Dual-modal magnetic resonance and fluorescence imaging of atherosclerotic plaques in vivo using VCAM-1 targeted tobacco mosaic virus. Nano Lett. 2014;14(3):1551-8. doi: 10.1021/nl404816m, PMID 24499194.

Kao CW, Wu PT, Liao MY. Magnetic nanoparticles conjugated with peptides derived from monocyte chemoattractant protein1 as a tool for targeting atherosclerosis. Pharm Res. 2016;33(6):1391-400.

Kamaly N, Fredman G, Fojas JJ, Subramanian M, Choi WI, Zepeda K. Targeted interleukin-10 nanotherapeutics developed with a microfluidic chip enhance resolution of inflammation in advanced atherosclerosis. ACS Nano. 2016;10(5):5280-92. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.6b01114, PMID 27100066.

Ma S, Tian XY, Zhang Y, Mu C, Shen H, Bismuth J. E-selectin targeting delivery of microRNAs by microparticles ameliorates endothelial inflammation and atherosclerosis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:22910. doi: 10.1038/srep22910, PMID 26956647.

Beldman TJ, Senders ML, Alaarg A, Perez Medina C, Tang J, Zhao Y. Hyaluronan nanoparticles selectively target plaque-associated macrophages and improve plaque stability in atherosclerosis. ACS Nano. 2017;11(6):5785-99. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b01385, PMID 28463501.

Stern R, Asari AA, Sugahara KN. Hyaluronan fragments: an information rich system. Eur J Cell Biol. 2006;85(8):699-715. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2006.05.009, PMID 16822580.

O Brien KD, Allen MD, McDonald TO, Chait A, Harlan JM, Fishbein D. Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 is expressed in human coronary atherosclerotic plaques. Implications for the mode of progression of advanced coronary atherosclerosis. J Clin Invest. 1993;92(2):945-51. doi: 10.1172/JCI116670, PMID 7688768.

Nahrendorf M, Jaffer FA, Kelly KA, Sosnovik DE, Aikawa E, Libby P. Noninvasive vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 imaging identifies inflammatory activation of cells in atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2006;114(14):1504-11. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.646380, PMID 17000904.

Kheirolomoom A, Kim CW, Seo JW, Kumar S, Son DJ, Gagnon MK. Multifunctional nanoparticles facilitate molecular targeting and miRNA delivery to inhibit atherosclerosis in ApoE(-/-) mice. ACS Nano. 2015;9(9):8885-97. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b02611, PMID 26308181.

Boada C, Zinger A, Tsao C, Zhao P, Martinez JO, Hartman K. Rapamycin loaded biomimetic nanoparticles reverse vascular inflammation. Circ Res. 2020;126(1):25-37. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.315185, PMID 31647755.

Wu G, Wei W, Zhang J, Nie W, Yuan L, Huang Y. A self-driven bioinspired nanovehicle by leukocyte membrane hitchhiking for early detection and treatment of atherosclerosis. Biomaterials. 2020;250:119963. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.119963, PMID 32334199.

Song Y, Zhang N, Li Q, Chen J, Wang Q, Yang H. Biomimetic liposomes hybrid with platelet membranes for targeted therapy of atherosclerosis. Chem Eng J. 2021;408:127296. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2020.127296.

Kaplan RN, Riba RD, Zacharoulis S, Bramley AH, Vincent L, Costa C. VEGFR1-positive haematopoietic bone marrow progenitors initiate the pre-metastatic niche. Nature. 2005;438(7069):820-7. doi: 10.1038/nature04186, PMID 16341007.

Zimmer S, Grebe A, Bakke SS, Bode N, Halvorsen B, Ulas T. Cyclodextrin promotes atherosclerosis regression via macrophage reprogramming. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8(333):333ra50. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad6100, PMID 27053774.

Chourpiliadis C, Aeddula NR. Physiology, glucocorticoids. Tresure island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

Day RA, Sletten EM. Perfluorocarbon nanomaterials for photodynamic therapy. Curr Opin Colloid Interface Sci. 2021;54:101454. doi: 10.1016/j.cocis.2021.101454, PMID 34504391.

Han X, Xu K, Taratula O, Farsad K. Applications of nanoparticles in biomedical imaging. Nanoscale. 2019;11(3):799-819. doi: 10.1039/c8nr07769j, PMID 30603750.

Rethi L, Rethi L, Liu CH, Hyun TV, Chen CH, Chuang EY. Fortification of iron oxide as sustainable nanoparticles: an amalgamation with magnetic/photo responsive cancer therapies. Int J Nanomedicine. 2023;18:5607-23. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S404394, PMID 37814664.