Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 1, 2025, 48-58Review Article

AN EMERGING ERA IN DRUG DELIVERY SYSTEM FOR TREATMENT OF MALARIA: WAVE FROM CONVENTIONAL TO ADVANCED TECHNOLOGY

TAMNNA SHARMA, ABHISHEK SHARMA*

University Institute of Pharma Sciences, Chandigarh University, Gharuan, Punjab, India

*Corresponding author: Abhishek Sharma; *Email: abhideeps21@gmail.com

Received: 07 Aug 2024, Revised and Accepted: 23 Nov 2024

ABSTRACT

Colonization of the erythrocytic stages of Plasmodium falciparum has become a challenging aspect in every drug delivery system because it is responsible for each clinical manifestation and life-threatening complication in malaria. With the emergence of resistance in malarial parasites in the recent past, developing a vaccine against malaria is still a long-drawn-out affair. However, recent reports of the recombinant protein-based vaccine against malaria vaccine from Glaxo Smith Kline have initiated a new ray of hope. In such a scenario, the onus of developing a reliable drug against the disease remains the mainstay in fighting against malaria. This review delves into the various attempts carried out by researchers in the past to develop a drug against the erythrocytic stages of the malaria parasite and throws light on a very recent outcome that provides targeted delivery of the drug to the infected erythrocyte using a nanotechnology-based approach. Considering the eventful journey in the beginning, it was the discovery of chloroquine that created an epoch in the treatment of malaria. Due to its low cost and high efficacy, it became the most widely used antimalarial. Until the 1960s, Chloroquine (CQ) was the best solution against malaria, but the scenario changed in the 1970s due to widespread clinical resistance in Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax in various parts of the world. This, in turn, led to the development of novel drug delivery systems using liposomes and Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLN) for more effective and site-specific delivery of chloroquine to the infected erythrocytes. Such attempts led to a later use of the nanotechnology-based approach which included the use of nanospheres and nanoparticulate drug carriers.

Keywords: Malaria, Novel drug approaches, Nanotechnology, Artificial intelligence

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i1.52285 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Malaria is a serious and sometimes fatal disease caused by a parasite that commonly infects a certain type of mosquito that feeds on humans. People who get malaria are typically very sick with high fevers, shaking chills, and flu-like illness [1]. Although a variety of antimalarial drugs are available for treatment, public health emergencies regarding malaria are increasing due to the spread of specific types of malaria parasites that are resistant to these drugs. In part because of the moderate to high costs of these drugs and the often uncontrolled counterfeit antimalarial market, most people in malaria-endemic countries have no immediate access to affordable, effective antimalarial therapy [2]. Also, the prevention of malaria with chemoprophylactic drugs is often not successful and is accompanied by many problems. Lastly, large-scale efforts for eradicating malaria through vector control strategies have met with little success and are not feasible against the persistence of the disease in many parts of the world today. Malaria is a disease that is both preventable and curable. However, it remains a serious public health problem in many countries. Malaria presents a risk for 3.2 billion people globally and caused 576,000 deaths in 2015 [3]. The following malaria data for 2022 were highlighted in the World Malaria Report 2023. In 2022, there were around 249 million malaria cases worldwide, an increase of 5 million over 2021. An anticipated 608,000 people will die from malaria worldwide in 2022, an almost 6% rise from 2019. In 2022, the African continent bore the brunt of the malaria load, accounting for 94% of global cases and 95% of malaria-related deaths, with children under the age of five accounting for approximately 78% of these deaths [4]. Around 1.27 billion people on the African continent were susceptible to malaria infection, with 186 cases and 47 fatalities per 100,000 people. Africa has seen a 7.6% decrease in malaria incidence and mortality since 2015 [5]. The disease is caused by parasites of the Plasmodium species and is transmitted to humans through the bites of infected mosquitoes. Most deaths are caused by Plasmodium Falciparum, which is the most prevalent and the most fatal malaria parasite in Africa. 90% of all malaria deaths occur in sub-Saharan Africa. Other high-risk groups include pregnant women and children less than 5 years of age [6]. In non-endemic countries, imported cases of malaria occur frequently due to human migration and travel. Malaria can be fatal if not treated promptly with an effective antimalarial medicine. However, an accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment of malaria, particularly Plasmodium falciparum infection, is complex [7]. This is because the clinical symptoms of malaria are nonspecific and can be mistaken for other febrile illnesses and access to healthcare and effective antimalarial treatment is poor in many endemic regions. This all leads to increased drug pressure and resistance of the parasites to antimalarial medicines, making malaria control significantly more difficult and furthering the burden of the disease [8]. Due to these factors, malaria is a continual threat to the developing world and can have a significant impact on economic development. Malaria viruses are spread by Anopheles mosquitoes. The mosquito bites are used as host to mature the parasites in the mosquito's stomach [9]. These parasites then travel to the salivary glands of mosquitoes, and the cycle is repeated during the next mosquito bite. Various research have been conducted previously that undoubtedly attests to numerous therapeutics used in treating malaria. From 1990 to 2024 there have been more than 988 reviews and research articles in the PubMed database indicating their significant significance. The systemic review inclusion of 222 studies indicated the therapeutic advantages in the treatment of malaria.

Epidemiology

The epidemiology of malaria is tightly related to transmission intensity, acquired immunity, and clinical symptoms. Malaria is caused by Plasmodium parasites, which are spread through the bite of infected female Anopheles mosquitoes [10]. Immunity is highest in locations with intense transmission, with children under the age of five being the most vulnerable group, particularly in Africa, where the majority of malaria-related deaths occur. Displaced populations from low-transmission areas are more vulnerable due to a lack of acquired immunity, needing extensive intervention measures to prevent morbidity and mortality. Plasmodium parasites, which are spread by Anopheles mosquitoes carrying the infection, cause malaria. Plasmodium falciparum is the deadliest of the four primary species that infect people, along with Plasmodium vivax, Plasmodium ovale, and Plasmodium malaria [11]. Around the equator, malaria is endemic throughout a large area, mostly in tropical and subtropical parts of Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Globally, there were predicted to be 247 million cases of malaria in 2021, with 619,000 fatalities from the disease; 94% of cases and deaths were in the African region as per the reports from the World Health Organization (WHO). Each region has a different level of malaria transmission; some have high, moderate, or low transmission [12]. The spleen rate, yearly parasite incidence, and entomologic inoculation rate are examples of epidemiologic metrics. Since malaria immunity is developed via repeated exposure, young children under the age of five in high-transmission regions have the greatest fatality rates. As the rate of transmission declines, more people of all ages fall sick, and cerebral malaria becomes more prevalent than severe anemia [13]. Due to a lack of immunity, displaced persons migrating from low-to-high-transmission zones are most vulnerable to serious illness. Chronic impacts of malaria can include anemia and unfavorable pregnancy outcomes [14]. The genetic variety of Plasmodium species, climatic change, and interruptions to prevention and control efforts, as shown during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic are the factors that affect the epidemiology of malaria. To address the changing global malaria load, ongoing surveillance, research into parasite resistance, and coordinated control techniques are crucial.

Etiology

Malaria is caused by the complex lifecycle of Plasmodium parasites, which results in typical cyclical fevers and varied incubation times among species. Malaria can cause symptoms ranging from moderate to severe, including paroxysmal fever, anemia, and potentially fatal consequences such as cerebral malaria and multi-organ failure [15]. The female Anopheles mosquito, which requires a blood meal to produce eggs, is the vector of human malaria, with distinct species preferences and behaviors determining transmission dynamics. The illness's etiology also includes aspects such as the genetic variety of Plasmodium species, the evolution of drug-resistant strains, and the effects of climate change on disease distribution, emphasizing the need for complete understanding and effective control techniques [16]. Plasmodium is the genus of single-celled parasites that cause malaria. Human infections are most frequently caused by plasmodium falciparum, plasmodium vivax, plasmodium ovale, and plasmodium malariae. The way these parasites infect people is by biting by a female Anopheles mosquito carrying the infection. The parasites enter the circulation from an infected mosquito bite and go to the liver where they develop. The adult parasites re-enter the systemic circulation and infect Red Blood Cells (RBC) after a few days [17]. The parasites grow quickly inside the RBC, rupturing the infected cells. Depending on the species, this cycle continues with the parasites infecting new RBC every 48 to 72 h. Certain Plasmodium species, including Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium ovale can lie dormant in the liver for months or even years before springing back to life and inducing another illness relapse [18]. Additionally, organ transplants, blood transfusions, and mother-to-child transmission during pregnancy and childbirth can all result in malaria transmission. Depending on the variety of Plasmodium involved, malaria can vary in severity. The deadliest strain Plasmodium falciparum, can result in serious side effects such as organ failure, respiratory distress, and brain malaria. Generally, the sickness is caused by other species such as Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium ovale in lesser forms [19].

Life-cycle of malaria

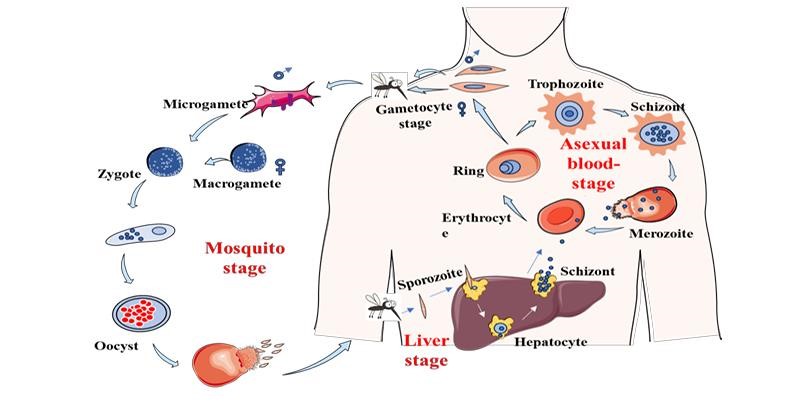

Malaria's life cycle (fig. 1) begins when a female Anopheles mosquito carrying Plasmodium parasites bites a human host. During its blood meal, the mosquito injects sporozoites into the bloodstream. These sporozoites travel to the liver, where they infect hepatocytes and undergo replication, resulting in thousands of merozoites. Once mature, the merozoites enter the bloodstream and begin the symptomatic phase of malaria. Merozoites multiply rapidly within RBC, causing the cells to rupture and release additional parasites [20].

Fig. 1: Life cycle of malaria [20]

This cycle of invasion, replication, and rupture causes malaria's characteristic symptoms, such as fever, chills, and anemia. Some merozoites mature into sexual forms known as gametocytes, which can be consumed by another mosquito during a blood meal, completing the cycle [21].

Challenges in malaria treatment

Cluster and shady environments such as pools, lagoons, slow-moving streams, or rice fields are the most common places where mosquitoes live. These types of mosquitoes are very vicious because they tend to bite humans during the night. Humans are attracted to these places because they are looking for places to perform various activities, like setting up a new village or moving to open a new estate for their livelihood. During the opening activities of the new village or estate, the shelter is a temporary wooden house that can be used for a certain period before they decide to make it permanent [22]. A lot of people's density is one of the reasons this layout phase is too inviting for mosquitoes. Malaria itself is a disease that thrives among the poor. The general pattern is that poor livelihood usually means a conducive environment for malaria. This is because of the development of the area where they live and the malaria parasites share the same characteristic of temporary residence [23]. In today's situation, the movement of humans and the rising increase of global tourist employees, apart from the various levels of societies that live or work in undeveloped areas, are potential vectors for malaria transmission. The protective immunity to symptomatic malaria is acquired slowly over several years and may be lost after leaving an endemic area [24]. This also applies to people residing in undeveloped areas. Lack of immunity to malaria symptoms in general non-immune persons may increase the chance of getting severe disease and can lead to death. This is due to a mistaken perception that malaria is a disease that only affects people at a certain level of society and that protection from severe diseases and death has never been a main priority of malaria control and treatment, especially for the poor. Nowadays, antimalarial drugs are not only taken for malaria treatment but also for prevention from getting malaria during their journey, especially for global tourist employees, and may be taken for a long time for people in the high-risk group to avoid severe diseases. This situation indicates that the drug is not only used under malaria diagnosis and the cost may be expensive for some prevention methods [25].

Traditional drug delivery methods for the treatment of malaria

The traditional methods for drug delivery include oral administration, intramuscular injection, and intravenous injection (table 1). For intramuscular injection, the surface area of the injection and the state of the blood circulation are too varied to provide a clear and predictable pathway for the drug to follow [26].

Table 1: Drugs traditionally available for the treatment of malaria

| Drug | Route of administration | Type of dosage form | Applications | References |

| Arteether/Lumefantrine | Oral | Tablet | Uncomplicated plasmodium falciparum malaria | [27-29] |

| Artesunate | Parenteral | Injection | Severe malaria | [30, 31] |

| Atovaquone | Oral | Tablet | Malaria prophylaxis | [32, 33] |

| Atovaquone/proguanil | Oral | Tablet | Malaria prophylaxis, uncomplicated malaria | [34] |

| Chloroquine | Oral | Tablet | Plasmodium vivax, Plasmodium malaria, Plasmodium ovale malaria | [35] |

| Hydroxy chloroquine sulfate | Oral | Tablet | Malaria prophylaxis, treatment of malaria | [36] |

| Primaquine | Oral | Tablet | Radical cure of Plasmodium vivax, Plasmodium ovale malaria. | [37] |

| Pyrimethamine sulfadoxine | Oral | Tablet | Radical cure of Plasmodium vivax, Plasmodium ovale malaria | [38] |

| Quinine | Oral, parenteral | Tablet | Severe malaria, uncomplicated malaria | [39, 40] |

| Pyrimethamine | Oral | Tablet | Malaria prophylaxis, treatment of malaria | [41] |

| Tafenoquine | Oral | Tablet | Radical cure of Plasmodium vivax. | [42] |

This results in inconsistent drug absorption and can lead to ineffective treatment. Intravenous injection has a more reliable drug administration mechanism. Despite increased access to blood circulation, however, where the malaria parasite resides, the drugs need to pass through numerous metabolic and physical barriers which still leave the efficacy of treatment questionable. In both cases, the traditional delivery methods offer no targeting of the drug to the infected cells and as a result, show partially effective methods of treatment. This often results in the need for large doses of drug, which can lead to toxicity, especially in the case of intravenous injection, where access to the bloodstream can result in high drug levels in the blood. Oral administration is the simplest method of drug delivery and is still the most commonly used today. Usually, tablets or capsules are administered incorporating the drug into a binding agent which will dissolve when it reaches the stomach [43].

Oral administration

Oral administration is the most used route for the delivery of drugs. Its popularity stems from its ease, convenience, and patient compliance, and its capacity for controlled dosing and good distribution characteristics make it an attractive route for drug administration. The digestive system and liver can act as a site for drug metabolism [44]. Though this may render some drugs inactive, others are altered into more therapeutically active forms. Thus, oral administration is a favorable option for drug delivery to the liver using antimalarial agents to treat liver-stage malaria. Oral drug delivery aims to release the drug at a specific site in the body and release the drug in a controlled manner to ensure maximum efficacy in treatment with minimum dosage. This can be accomplished using specific targeting and timed release of drugs. Based on drug properties and form, drugs can be targeted to release in the stomach, lymph, or liver. The high biological availability of drugs in the stomach may be ideal for toxic drugs to kill parasites in erythrocytes; however, it may cause stomach irritation and inflammation. Drugs targeted to release in Kupffer cells can target parasites in Kupffer cells and prevent hepatic schizogony [45]. Malaria infection is caused by the inoculation of sporozoites into the dermis, while female Anopheles mosquitoes ingest blood from human beings. The sporozoites are carried by the blood to the liver, where they invade hepatocytes. After undergoing one or more multiplication cycles, each resulting in the release of hundreds or thousands of merozoites, the infected hepatocytes rupture and release the merozoites into the blood. The merozoites then invade RBC where they develop and eventually multiply, resulting in generating more merozoites, which cause malaria-associated morbidity. The blood-stage parasites are responsible for the clinical manifestations of the disease. The objective of treatment is to prevent and cure the disease and stop transmission. Current shortcomings of drugs include drug resistance, limited effectiveness in gametocyte and liver stages, high toxicity, low patient compliance, and prevention of post-treatment mosquitoes. Many antimalarial drugs have been developed; however, only a minority have been developed specifically for treating malaria. This minority of drugs, specifically antimalarial agents, can be delivered using targeted drug delivery systems, unwrapping the potential of these drugs [46].

Intravenous injection

Traditional methods of drug delivery are currently the most prevalent form of treatment for malaria. These methods are dangerous and difficult to use but can also carry substantial risks to the patient's health and recovery. In severe cases of malaria, intravenous administration has been the preferred option for treatment [47]. This method increases the bioavailability of the drug and is effective when treating severe cases. It can be difficult to use in field situations or for widespread treatment. Intravenous treatment requires healthcare personnel to be available for multiple doses over 24-48 h, making it difficult for patients in remote or rural areas to access treatment. This form of treatment is also risky as the wrong administration of a drug can cause severe systemic toxicity or even death to the patient. These risks and difficulties associated with traditional drug delivery for malaria are the driving factors behind the development of novel drug delivery systems [48].

Intramuscular injection

The second most common mode of drug administration is via intramuscular injection. It is often used for drugs that cannot be digested as in oral administration or when a more localized effect is desired that cannot be obtained through intravenous administration. The injection is a bolus dose that slowly gets absorbed at the injection site. Since blood flow in muscle tissue is lower than that in veins, absorption of the drug may be delayed. However, the bioavailability of intramuscular administration is complete and there is no risk of immediate alteration of the drug by the body [49]. The slow absorption and sustained release of the drug from muscle tissue can be useful in treating malaria. Drugs like quinacrine, which is no longer used in the Western world, have a high solubility in lipids and would remain in fatty tissue for several weeks. Other drugs that can crystallize and cause irritation at the injection site are less suited for this method of delivery. High levels of blood flow are also required as in the case of artesunate and artemether which are less suited for intramuscular injection. Overall, this mode of delivery is not specially tailored for treating malaria and has not been studied extensively for this disease [50].

Combination therapies and drug delivery

Antimalarial combination therapy has a potential role in fulfilling the postulated requirement. Its successful application and subsequent resistance management can provide a superior solution to the current situation and change the expected course of antimalarial drug resistance. In theory, antimalarial drug resistance can be managed by changing the drug pressure equation in favor of host immunity. Resistance is an inevitable outcome of the repeated use of any antimalarial monotherapy. Its emergence and rate of subsequent spread are determined by the duration of post-treatment prophylaxis and the force of infection [51]. It has a devastating impact on malaria morbidity and mortality, increasing both outcomes more than the original disease burden. The last half-century has seen the rapid spread of antimalarial drug resistance. This process was initiated with CQ resistance on the Thailand-Cambodia border in the late 1950s. CQ use had a massive impact on reducing malaria burdens in many parts of the world, but resistance substantially increased disease burdens compared to pre-CQ levels. Subsequent uses of antifolate drugs (sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine), 4-aminoquinolines (amodiaquine, chloroquine, and mefloquine), and more latterly atovaquone have seen similar substantial increases in malaria morbidity and mortality in areas of their use. Between 1989 and 2003, resistance to insider reduced child survival in sub-Saharan Africa by 1-6% in areas of drug use. The overall multiplicative effect of antimalarial drug resistance is an increase in all-cause childhood mortality [52].

Novel drug delivery approaches

Targeted drug delivery (fig. 2) of the anti-malarial drugs using site-specific drug delivery systems is one of the major advantages of the drug delivery system-based approaches to improving the efficacy of prophylaxis and the treatment of malaria. The most ambitious aim of treatment or prevention of the disease is complete eradication of the parasite in the body and prevention of re-infection. To achieve this goal, effective killing of the parasite without damage to the host should be carried out [53]. Antimalarial drugs act mainly on the infected RBC; free or hemozoin-bound drugs are at best only partially effective and at worst, toxic to the host. Thus, the drug must be actively or passively targeted to infect RBC. Christoph and his colleagues developed a novel in vivo targeting system based on the high affinity of infected RBC for endothelial receptors. This was achieved by administration of drug-loaded carrier erythrocytes which bound to the site of infection and released the drug, resulting in specific and highly effective therapy in animal models. Advance in this type of strategy was the development of carrier RBC which were infected in vitro with Plasmodium and thus acquired high affinity for infected RBC. Although this approach had outstanding potential it was not pursued, presumably due to safety concerns and the fact that it would not be relevant to human infections. An alternative method of RBC drug targeting is binding of the drug to RBC ghosts, which are then re-infused into the patient.

Fig. 2: Novel drug delivery approaches in malaria [54, 55]

This would also be an effective system albeit costly. A summary and appraisal of the various methods of RBC drug targeting are available, including an exhaustive review of the first-generation targeted antimalarial drugs. Carriers for targeted drug delivery for treating severe disease are another attractive option, although the potential for adverse effects on the parasite and not the host in this case, will necessitate special precautions [56].

Targeted drug delivery

Targeted drug delivery is a cutting-edge strategy in innovative medication delivery that seeks to deliver pharmacologically active substances to a particular target place within the body. Reducing medications adverse effects and improving treatment are the main goals of targeted delivery systems. Passive targeting and active targeting are the two basic approaches for targeted medication delivery. Drug-loaded nanoparticles are passively accumulated in the tumor via increased permeability, retention, and other special physiological properties of the drug delivery system. As a result, concentration of the medicine at the tumor location is better than in healthy tissues. Targeting ligands, such as antibodies, peptides, or small molecules can attach to over-expressed receptors on target and are used to functionalize the drug carrier in active targeting. This makes it possible for the medication payload to be delivered to the targeted target more precisely. The medication's effectiveness and selectivity may be further improved by active targeting. The creation of several nano-carrier systems, such as liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles, and inorganic nanoparticles for targeted medication administration, has been made possible by advancements in nanotechnology. It is possible to design these nanocarriers to enhance the pharmacokinetics, biodistribution, and intracellular absorption of medications [57]. By carefully delivering lethal medications to cancerous growths with the least amount of damage to healthy tissues targeted drug delivery has demonstrated the potential to enhance therapy. Overcoming biological obstacles, increasing penetration, and optimizing carrier design are ongoing difficulties. The combined use of passive and active targeting techniques can improve treatment efficacy in a complementary manner. Tailored drug delivery is an effective strategy for new medication delivery, which makes use of the distinct biology of disease and nanotechnology to enhance the efficacy and selectivity of pharmacotherapy [58].

Nanoparticles in malaria treatment

The nanoparticles have become a viable new medication delivery method in the treatment of malaria. Plasmodium parasites produce malaria a difficult illness with limited treatment options due to issues with medication resistance, low bioavailability, short half-lives, and non-specific targeting. By strengthening targeted delivery, lowering side effects, and boosting pharmacokinetic profile, nanostructured drug delivery devices can assist in overcoming these constraints [59]. Using both passive and active targeting techniques, nanoparticles may be designed to specifically target the malaria parasite's home, the infected RBC. The increased permeability and retention effect allows nanoparticles to collect preferentially in the tumor-like vasculature of infected tissues and provides the basis for passive targeting. To facilitate more targeted distribution of the antimalarial drug payload, active targeting entails functionalizing the nanoparticle surface with ligands that can bind to receptors over-expressed on infected RBC. Many nano-carrier systems have been studied for the treatment of malaria, including liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles, and inorganic nanoparticles. By encapsulating antimalarial medications, these nanocarriers can increase the medicine’s solubility, stability, and control in improving therapeutic efficacy and lowering toxicity. The promise of nanotechnology to overcome the drawbacks of traditional malaria treatments has been shown by ongoing research in this area. To reach their full potential in treating this worldwide health burden, these nano-based drug delivery technologies still require research and clinical translation [60].

Microneedles for transdermal delivery

A potential method for new medication delivery intended for transdermal administration is use of microneedles. Microneedles are tiny needles that can pierce the stratum corneum, the skin's outermost layer, to allow for less invasive transdermal medication administration. The transdermal medication delivery method with microneedles has several significant benefits. First off, in contrast to conventional transdermal patches, microneedles can temporarily generate microchannels in the skin, which facilitates medication penetration through the skin barrier. Because microneedles may penetrate via the stratum corneum, the primary barrier to skin penetration results in better medication administration and increased bioavailability. Furthermore, compared to hypodermic needles, microneedles are tiny enough to be inserted into the skin without generating a great deal of discomfort, which improves patient compliance. Additionally, microneedles are a versatile platform for innovative drug delivery techniques because they may be constructed in various shapes, such as solid, coated, dissolving, and hollow to fit diverse drug compositions and delivery needs. Transdermal administration using microneedles has been investigated for a variety of medications, including vaccines, small compounds, peptides, proteins, and even nanoparticles. The goal of ongoing research is to further improve drug delivery efficiency, stability, and patient acceptance by refining microneedles design, materials, and production. Research on microneedles-based transdermal drug delivery systems is ongoing and several candidates have advanced through clinical trials. Microneedles are a clever and extremely promising new drug delivery method that might enhance transdermal administration [61].

Nanocarriers for the treatment of malaria

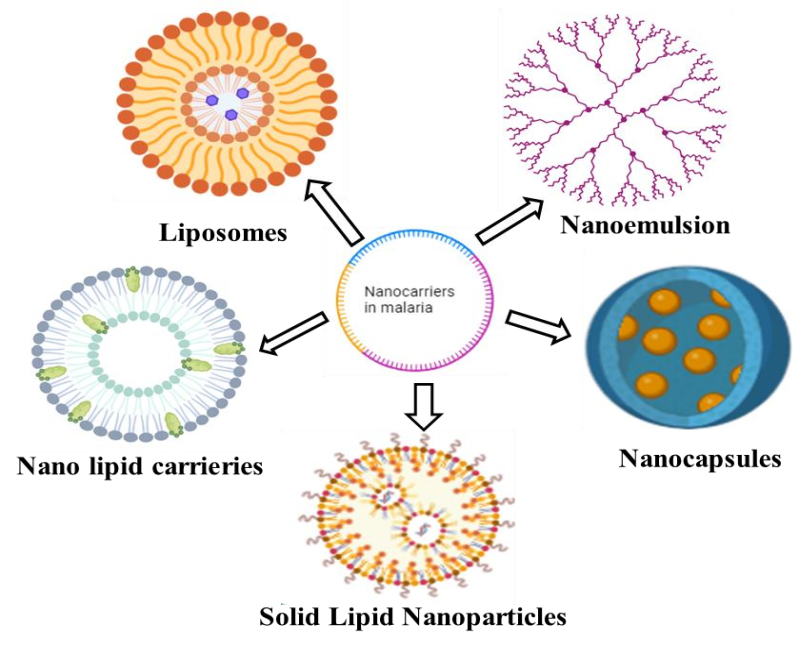

The pharmacokinetic profile of beneficial medications that have not been widely used in pharmacotherapy because of their high toxicity, low bioavailability, and poor water solubility can be improved using nanocarriers. Nanocarriers have been suggested for the diagnosis and treatment of malaria as well as the creation of vaccines. It's also possible that using inefficient pharmaceutical doses of antimalarials drug could contributes resistance in malaria parasites. Because nanotechnology systems can precisely target medications to their site of action, they may provide a better therapeutic effect. Due to the administration of low medication concentrations in the presence of a high parasitic load, malaria parasites frequently acquire treatment resistance. Furthermore, by altering their biodistribution and lowering toxicity, nanotechnology may revive the usage of outdated and harmful medications. This benefit is especially significant for the treatment of malaria because, especially for the antimalarial used in clinical settings, there is a need to find novel dosage forms that can effectively deliver medications to parasite-infected cells [62]. In addition to enabling the use of harmful antimalarial drugs, nanocarriers may improve vaccine formulation ability to elicit an immunological response. The goal of this review is to clarify some biological elements of malaria and connect them to nanotechnology as a potentially effective therapy approach. Taking into consideration the unique characteristics of malaria parasites, several methods for delivering antimalarial drugs as well as the processes that enable their targeted administration to Plasmodium-infected cells will be highlighted. In particular, the focus will be on polymeric-based nanosystems (fig. 3), like nanocapsules and nanospheres for the treatment of malaria, as well as lipid-based nanocarriers, like liposomes, SLN, nanoemulsions, and microemulsions. These nanocarriers are spherical vesicles made of phospholipid bilayers and are viable carriers for innovative drug delivery strategies since they can successfully encapsulate hydrophilic and hydrophobic medicines. This nanocarrier shape enables them to dissolve in water in their aqueous core and dissolve in fat in their phospholipid bilayer. As medication delivery systems, nanocarriers have several benefits. By altering drug absorption, lowering metabolism, and directing the medication to the site of action, they can raise the therapeutic index of pharmaceuticals. Because of their different biodistribution, liposomal formulations of pharmaceuticals are more effective in treating patients in preclinical models and people than traditional formulations [63]. These nanocarriers have less toxicity and adverse consequences since their composition is made up of lipids that are non-immunogenic, biodegradable, and inert to biology. Targeting ligands may be easily included on the liposome surface to enable active targeting to certain locations. Nanocarriers have less toxicity and adverse consequences since their composition is made up of lipids that are non-immunogenic, biodegradable, and inert to biology. Targeting ligands may be easily included on the carrier’s surface to enable active targeting to certain locations. The preparation process affects the entrapment efficiency of medicines in nanocarriers. For the transport of a broad variety of physiologically active substances, including tiny molecules, proteins, peptides, and nucleic acids, liposomes have been thoroughly studied. Their potential has been demonstrated in several therapeutic applications, including administration of antibiotics and antifungal drugs, gene therapy, and cancer treatment.

Fig. 3: Nanocarriers for the treatment of malaria [64, 65]

Despite the benefits, there are still some obstacles to be overcome in the development of nano-carrier drug delivery systems, including enhancing stability, raising drug loading, and getting through biological barriers to enable targeted delivery. Research is still being done to overcome these obstacles and maximize liposomes' potential as sophisticated and adaptable nanocarriers for cutting-edge drug delivery strategies. Recent studies on nanotechnology in malaria treatment. Over time, there have been more and more papers on nanoparticles to cure malaria. One search on the National Library of Medicine databases is only one article between 1990 and 2000 and eight between 2001 and 2010. This article analyzes 103 papers in total that discuss the use of nanoparticles in the treatment of malaria. Each year, they are broken into the following numbers: 5 articles in 2017, 9 articles in 2018, 13 articles in 2019, 24 articles in 2020, and 21 articles in 2021. There will be a substantial increase in the number of papers in 2022 that discuss research on the use of nanoparticles to treat malaria. 31 publications on this topic may be consulted in 2022. Numerous researches focused on the use of nanotechnology in treating malaria from 2019 to 2022 confirmed encouraging findings indicating the potential of nanosystems. On the other hand, there are surprisingly few documented active medication delivery-based clinical studies for the treatment of malaria. Over the past ten years, dendrimers have attracted attention for a variety of biological uses including the transport of drugs, genes as well as agents for diagnostic imaging [66]. Preclinical research in treating malaria with nanotechnology in the intra-erythrocytic stage of Plasmodium falciparum in both phases of parasite growth (asexual and sexual) for example, small gold nanoparticles based on glucose or nano gold clusters were produced without nonspecific connections or destruction of RBC. The antibacterial impact of ciprofloxacin loaded into glucose or nano gold clusters were 50% more than that of the drug alone, indicating its potential for use in medicine. In Plasmodium falciparum cultures, silver nanoparticles formed from Artemisia leaf extract showed strong antimalarial efficacy. In an experimental malaria model, silver nanoparticles from salvia officinalis leaf extract showed hepatoprotective and antiplasma actions, lowering parasitemia and liver oxidative stress indicators. To overcome issues in the treatment of malaria, such as the severity of the disease, the critical studies based on nanotechnology are being conducted. These studies are primarily concerned with reducing drug toxicity, stopping Plasmodium sp. transmission, increasing drug efficacy, and preventing multidrug resistance [67].

New drugs in clinical and preclinical development

Antimalarial medicines in clinical and preclinical development under development globally are analyzed in the WHO study from 2021. For the first time, antimalarial medication candidates in clinical development including biological agents and unconventional therapies-are evaluated in the clinical pipeline review. The preclinical development of vaccines, biological agents, direct-acting small compounds, and non-traditional medications is the main emphasis of the preclinical pipeline section. However, the preclinical pipeline reveals an unstable environment with significant turnover, protracted timelines, and difficult benchmarks before possibly entering the market [68, 69].

Table 2: Drugs in clinical and pre-clinical development

| Name of drug | Mechanism of action | Safety | Efficacy | Development stage | References |

| Artemisinin and derivatives | Inhibition of parasite calcium ATPase | Generally well-tolerated; concerns about resistance | Highly effective against Plasmodium falciparum; rapid reduction in parasitemia | Approved | [70, 71] |

| Lumefantrine | Inhibition of beta-haematin formation | Generally safe; common side effects include headache | Highly effective when combined with Artemether | Approved | [72] |

Atovaquone/ Proguanil |

Disruption of mitochondrial electron transport (Atovaquone) and folate synthesis (Proguanil) | Mild side effects like nausea; liver toxicity rare | High efficacy against Plasmodium falciparum | Approved | [73] |

| Fosmidomycin | Inhibits isoprenoid biosynthesis | Generally well tolerated; few side effects | Shows promise in multi-drug resistant malaria | Clinical Phase II | [74] |

KAF156 (Lumefantrine analog) |

Acts on the apicoplast, inhibiting protein synthesis | Not fully established; ongoing studies on safety | Promising efficacy in early trials | Clinical Phase II | [75] |

| P218 | Targets the Plasmodium falciparum 4-quinolones resistance transporter | Safety profile under investigation | Promising early results against resistant strains | Preclinical | [76] |

| Tafenoquine | Inhibition of parasite development and replication | Risk of hemolysis in G6PD-deficient patients | Effective in preventing relapse of Plasmodium vivax | Approved | [77] |

| Dihydroartemisinin-Piperaquine (DHP) | Similar to Artemisinin, with prolonged action of Piperaquine | Generally well tolerated; some GI disturbances | High cure rates; effective against multi-drug resistant strains | Approved | [78] |

| NITD609 | Inhibits Plasmodium falciparum Plasmepsin IV | Safety data pending from ongoing trials | Effective against asexual stages of Plasmodium. falciparum | Preclinical | [79] |

| Nioxin | Inhibits various stages of the Plasmodium life cycle | Safety profile under investigation | Preliminary efficacy observed | Preclinical | [80] |

Pyramax (artesunate/ amodiaquine) |

Combination therapy enhancing efficacy | Generally well tolerated; some side effects noted | Effective against uncomplicated malaria | Approved | [81] |

| Methylene blue | Inhibition of the heme detoxification pathway e | Concerns regarding potential toxicity | Potential activity against malaria | Preclinical | [82] |

Challenges in treatment of malaria

Finally, it is difficult to predict the long-term safety and effectiveness of a new drug formulation. New adverse effects could emerge and in some cases, the newer drugs might not be as well tolerated as the older drugs. All these issues are relevant to the global public sector and malaria control programs but are especially pertinent to developing private-sector aims to develop new antimalarial drugs. An understanding of how the characteristics of new drugs will impact their use and how the drugs will fit into the larger global antimalarial landscape is critical to the private sector's success in bringing new therapies to market. High rates of compliance and proper use of the antimalarial drugs are critical. The best drug in the world will not have a large impact on public health if it is not used correctly. Malaria patients in many contexts are difficult to reach and difficult to treat. This makes drug administration and patient monitoring quite difficult [83]. Another issue from the standpoint of the communities being treated is the perception of new drug formulations as compared to the traditional drugs that they are accustomed to using. The newer drugs may not be accepted immediately, and in some cases, the new drugs may not be as effective in all of the same contexts as the traditional drugs. This might create a temptation to continue using the older drugs in some situations, especially if the newer drugs are not cost-prohibitive. Although major advances have been made in the realm of antimalarial drug delivery systems but not all facts of these systems have been fully explored. The caveat to new drug formulations is perhaps their implementation. Even if a new effective and inexpensive drug therapy becomes available, it may be of limited value if it cannot be deployed easily and inexpensively. It is important that these new therapies reach the target populations and in many cases, this has not yet been accomplished with existing therapies [84].

Regulatory considerations

The main objective of regulatory authorities is to ensure the drugs that are available to patients are safe, effective, and of good quality. In general, pre-clinical studies (toxicology, pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics, and efficacy studies) including clinical trials in humans are required to show that the drug is safe and effective. Data from the clinical studies are used as a basis for the regulatory authority to decide whether the drug should be approved and granted marketing authorization/distribution in the specific country. Comprehensive studies to show that the drug is effective and safe in a field setting are not required, but it is often difficult for a new antimalarial drug to be accepted based on results from studies conducted outside of areas where malaria is endemic. Clinical trials provide evidence that the drug benefits outweigh the risks. There is a consensus that drugs should not be harmful, but for the treatment of malaria, a drug should have a high benefit-to-risk ratio because the disease is potentially fatal. High standards for quality and manufacture are also set by regulatory authorities to ensure that drugs are consistently and properly made. The drug regulatory authorities, such as the Food and Drug Administration in the United States of America the medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency in the United Kingdom, and similar agencies in other countries have set requirements for approving a drug that is intended to be used in humans to diagnose, prevent, or treat a disease. The requirements for regulatory approval of antimalarial drugs are not different from other drugs. However, there could be some variations in the requirements depending on the endemicity of malaria in the region and the perceived public health value of the drug in that specific region [85].

Drug resistance

Anti-malarial drugs have been the basis for treatment and control of the disease for over 50 years. The increase of drug resistance by the parasite species to the available drugs has results in increased morbidity and mortality of the disease. The main thrust of drug research up to this period was the identification of cheap, safe, and effective treatment that would alleviate symptoms and cure the infection in a single dose. This would be of most benefit to the patient and negate the need for complicated and costly drug administration involving a cocktail of different drugs to circumvent resistance and achieve a radical cure for the different parasite species. A single-dose cure would also be the ideal tool for the large-scale elimination of malaria from a region. Currently, the most advanced anti-malarial drug in trials is the novel arteether-mefloquine combination (artemisone) developed with the specific goal of reducing the time for resistance to develop compared to existing drugs in the artemisinin group [86].

List of recent antimalarial drugs with patent granted

Antimalarial drugs with patent granted are highlighting those medications in the table that are currently protected by patents indicating that their developers or manufacturers have secured legal monopolies on their production and distribution. This distinction is important in understanding the landscape of antimalarial medications as it reflects the ongoing commercial and legal status of these drugs in the market [87].

Table 3: Patent on antimalarial drugs

| S. No. | Patent number | Application number | Title of Invention | Patent grant date | References |

| 1 | 281417 | 1507/KOLNP/2010 | Antimalarial compounds with flexible side chains | 17/03/2017 | 88 |

| 2 | 288805 | 131/KOLNP/2009 | Vaccines for malaria | 27/10/2017 | 89 |

| 3 | 289775 | 2074/DEL/2004 | The antimalarial compound from ghomphostema given | 21/11/2017 | 90 |

| 4 | 289823 | 1181/MUM/2009 | Combined measles malaria vaccine | 22/11/2017 | 91 |

| 5 | 293596 | 32/MUM/2013 | Intranasal microemulsion of an antimalarial drug artemether | 28/02/2018 | 92 |

| 6 | 298988 | 2798/MUM/2011 | Bioactive composition for the prophylaxis and treatment of malaria, method of manufacturing and using the same | 19/07/2018 | 93 |

| 7 | 310142 | 1773/MUM/2011 | Novel plasmodium protein as malarial vaccine and drug target | 27/03/2019 | 94 |

| 8 | 310371 | 7489/CHENP/2014 | Green chemistry synthesis of the malarial drug amodiaquine and analogs thereof | 29/03/2019 | 95 |

Integration of technology and drug delivery

An entirely different technology with the potential to revolutionize malaria vaccine delivery is the use of particle-based delivery systems. These systems can be designed to deliver the vaccine to specific cells such as macrophages or dendritic cells by selection of optimal particle and surface properties. For example, a recent study using virus-like particles showed that a vaccine targeting liver stages of malaria can provide unprecedented protection (>95%) using only a single dose. Additional benefits of particle-based vaccines are needle-free administration and the potential for thermal stability removing the need for cold storage and distribution, a major issue for vaccines in the developing world [96]. A multidisciplinary approach to drug and vaccine delivery technologies for malaria spanning the fields of material science, protein engineering, and biomechanics is essential for optimal prophylaxis and treatment. For example, targeting anti-malarial drugs to infected erythrocytes, the disease-causing cell, is a promising strategy being explored by several research labs. Successful targeting would increase drug localized drug concentration several-fold while avoiding healthy erythrocytes and reducing drug concentrations and side effects. Profiling the mechanical and shape-changing properties of these infected erythrocytes promises new methods for targeting drugs and vaccines. Simulation and measurement of the forces exerted by infected cells as they attempt to pass through inter endothelial slits in the spleen, as well as the altered cell and membrane stiffness, are providing valuable information for the design of effective drug targeting strategies prohibitive [97].

Role of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) in malaria

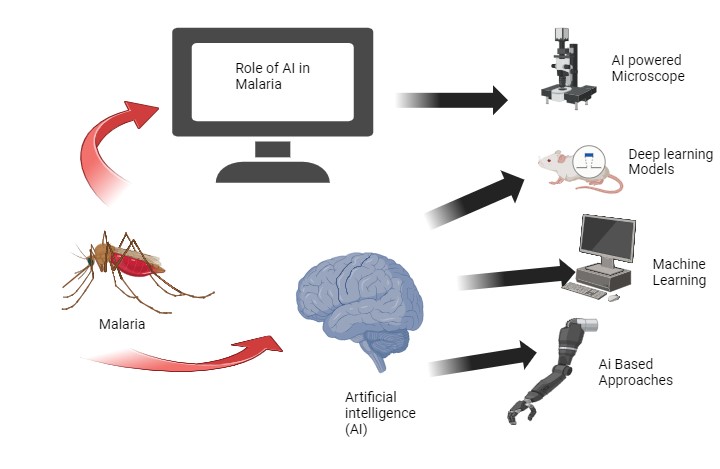

AI and ML are playing a significant role in improving malaria diagnosis and treatment in several ways. AI-powered microscopes can accurately detect malaria parasites in blood samples, meeting WHO standards. These systems can scan blood films and use detection algorithms to identify parasites, reducing the burden on microscopists and increasing patient capacity. Studies show the AI system can identify malaria parasites with 88% accuracy compared to expert microscopists [98, 99].

Fig. 4: AI-ML in treatment of malaria [100, 101]

Deep learning models are being used to analyze microscope images and determine the type and stage of malaria infection. This is particularly useful in remote areas with limited resources as the AI can interpret results even if a trained provider is not available. The models identify key characteristics in the images that indicate malaria. Machine learning algorithms are being developed to predict malaria outbreaks by analyzing atmospheric, epidemiological, geographic, and other data from remote sensors. This allows health officials to proactively notify at-risk populations, implement mosquito control measures, and allocate resources to areas likely to see outbreaks. Factors like temperature, humidity, and rainfall patterns are used to predict hotspots [102, 103]. AI-based approaches are being integrated with current malaria microscopy methods to strengthen surveillance and diagnostic capabilities, which is crucial for malaria elimination efforts. Investing in AI microscopy can improve sensitivity and accuracy, which are prerequisites for elimination. In summary, AI is bridging gaps in malaria diagnosis, treatment, and prevention by automating microscopy, predicting outbreaks and enhancing current methods. As AI continues to advance, it will play an increasingly important role in reducing the global malaria burden [104, 105].

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the emergence of novel drug delivery mechanisms for the treatment of malaria has presented a promising prospect for resource-poor countries by improving patient compliance and reducing the likelihood of developing drug-resistant malarial parasites. The newer drug delivery systems provide a potentially useful means to addressing the problem of under-treatment of the most vulnerable malaria patient populations-pregnant women and young children. The advent of microfabrication technologies and the understanding of malarial pathogenesis have enabled researchers to engineer highly sophisticated and more targeted drug delivery systems to combat the disease. However, most of the technologies are still in the developmental phase and it's estimated that it will take 10-15 years before putting them into practical use. Thus, implementation of these new drugs and technologies will require a long-term sustained commitment from governments and private sectors to ensure that people afflicted with malaria will benefit from these new drugs shortly. It is also important for the current and future generations of scientists and researchers in this field to maintain a high level of enthusiasm in hopes of eventually eradicating the disease that has plagued the world for centuries. Considering the unrelenting pressures of poverty, the return on investment for the effort to cure malaria is arguably higher than for virtually any other disease. For these reasons, new tools and drugs must continue to be developed to combat malaria.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Tamnna Sharma: performed the literature search, conceptualized the review, and wrote the original draft preparation. Dr. Abhishek Sharma: Contributed to manuscript writing, provided critical revisions, and editing the final version of the paper.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declared no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

REFERENCES

Fikadu M, Ashenafi E. Malaria: an overview. Infect Drug Resist. 2023 May 29;16:3339-47. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S405668, PMID 37274361.

White NJ, Pukrittayakamee S, Hien TT, Faiz MA, Mokuolu OA. Malaria DAM. Lancet. 2014 Mar;9918:723-35.

Phillips MA, Burrows JN, Manyando C, Van Huijsduijnen RH, Van Voorhis WC, Wells TN. Malaria. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017 Mar 3;3:17050. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.50, PMID 28770814.

Ashley EA, Pyae Phyo A. Malaria. Lancet. 2018 Mar 21;391(10130):1608-21. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30324-6. PMID 29631781.

Menard D, Dondorp A. Antimalarial drug resistance: a threat to malaria elimination. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2017 Jul 5;7(7):a025619. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a025619, PMID 28289248.

Olliaro P, Wells TN. The global portfolio of new antimalarial medicines under development. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2009 Jun;85(6):584-95. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2009.51, PMID 19404247.

Delves MJ, Angrisano F, Blagborough AM. Antimalarial transmission-blocking interventions: past present and future. Trends Parasitol. 2018 Sep;34(9):735-46. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2018.07.001, PMID 30082147.

Greenwood BM, Targett GA. Malaria vaccines and the new malaria agenda. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011 Nov 17;17(11):1600-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03612.x, PMID 21883665.

Doolan DL, Dobano C, Baird JK. Acquired immunity to malaria. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009 Jan 22;22(1):13-36. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00025-08, PMID 19136431.

Tilley L, Dixon MW, Kirk K. The plasmodium falciparum infected red blood cell. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2011 Jun;43(6):839-42. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.03.012, PMID 21458590.

Amaratunga C, Lim P, Suon S, Sreng S, Mao S, Sopha C. Dihydroartemisinin piperaquine resistance in plasmodium falciparum malaria in Cambodia: a multisite prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016 Mar 16;16(3):357-65. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00487-9, PMID 26774243.

Fairhurst RM, Dondorp AM. Artemisinin resistant plasmodium falciparum malaria. Microbiol Spectr. 2016 Jun;4(3). doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.EI10-0013-2016, PMID 27337450.

Price RN, Tjitra E, Guerra CA, Yeung S, White NJ, Anstey NM. Vivax malaria: neglected and not benign. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77(6)Suppl:79-87. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2007.77.79, PMID 18165478.

Miller LH, Ackerman HC, SU XZ, Wellems TE. Malaria biology and disease pathogenesis: insights for new treatments. Nat Med. 2013 Feb 19;19(2):156-67. doi: 10.1038/nm.3073, PMID 23389616.

Baird JK. Resistance to therapies for infection by plasmodium vivax. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009 Jul 22;22(3):508-34. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00008-09.

Fidock DA, Rosenthal PJ, Croft SL, Brun R, Nwaka S. Antimalarial drug discovery: efficacy models for compound screening. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004 Jun 3;3(6):509-20. doi: 10.1038/nrd1416, PMID 15173840.

Hoffman SL, Vekemans J, Richie TL, Duffy PE. The march toward malaria vaccines. Vaccine. 2015;49 Suppl 4:S319-33.

White NJ. Malaria parasite clearance. Malar J. 2017 May 16;16(1):88. doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-1731-1.

Rieckmann KH, Davis DR, Hutton DC. Plasmodium vivax resistance to chloroquine. Lancet. 1989 Jun 2;8673:1183-4. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)91792-3.

Bousema T, Drakeley C. Epidemiology and infectivity of plasmodium falciparum and plasmodium vivax gametocytes in relation to malaria control and elimination. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011 Apr 24;24(2):377-410. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00051-10, PMID 21482730.

Arama C, Troye Blomberg M. The path of malaria vaccine development: challenges and perspectives. J Intern Med. 2014 May;275(5):456-66. doi: 10.1111/joim.12223, PMID 24635625.

Tatem AJ, Smith DL, Gething PW, Kabaria CW, Snow RW, Hay SI. Ranking of elimination feasibility between malaria-endemic countries. Lancet. 2010 Oct;376(9752):1579-91. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61301-3, PMID 21035838.

Trape JF, Tall A, Diagne N, Ndiath O, Ly AB, Faye J. Malaria morbidity and pyrethroid resistance after the introduction of insecticide treated bednets and artemisinin based combination therapies: a longitudinal study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011 Dec 11;11(12):925-32. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70194-3, PMID 21856232.

Cowman AF, Healer J, Marapana D, Marsh K. Malaria: biology and disease. Cell. 2016 Oct;167(3):610-24. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.07.055, PMID 27768886.

Snow RW, Guerra CA, Noor AM, Myint HY, Hay SI. The global distribution of clinical episodes of plasmodium falciparum malaria. Nature. 2005 Feb;434(7030):214-7. doi: 10.1038/nature03342, PMID 15759000.

Sharma A, Patel T. Overview of antimalarial drugs: clinical and traditional perspectives. J Trop Med. 2024 Oct 15;4:123-30.

Pongvongsa T, Phommasone K, Phongmany P, Paboriboune P, Van Leth F, White NJ. Therapeutic efficacy of chloroquine for treatment of plasmodium vivax in Southern Laos. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2019 Sep;101(3):553-7.

Rathore D, McCutchan TF, Sullivan M, Kumar S. Antimalarial drugs: current status and new developments. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2005 Jul 14;14(7):871-83. doi: 10.1517/13543784.14.7.871, PMID 16022576.

Meshnick SR. Artemisinin antimalarials: mechanisms of action and resistance. Med Trop (Mars). 1998;58(3) Suppl :13-7. PMID 10212891.

Dondorp AM, Fanello CI, Hendriksen IC, Gomes E, Seni A, Chhaganlal KD. Artesunate versus quinine in the treatment of severe falciparum malaria in African children (AQUAMAT): an open label randomised trial. Lancet. 2010 Nov;376(9753):1647-57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61924-1, PMID 21062666.

Krishna S, Planche T, Agbenyega T, Woodrow C, Agranoff D, Bedu Addo G. Bioavailability and preliminary clinical efficacy of intrarectal artesunate in Ghanaian children with moderate malaria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001 Feb;45(2):509-16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.2.509-516.2001, PMID 11158748.

Pefanis A, Giamarellou H, Karayiannakos P, Donta I. Efficacy of ceftazidime and aztreonam alone or in combination with amikacin in experimental left sided pseudomonas aeruginosa endocarditis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37(2):308-13. doi: 10.1128/AAC.37.2.308, PMID 8452362.

Looareesuwan S, Wilairatana P, Glanarongran R, Indravijit KA, Supeeranontha L, Chinnapha S. Atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride followed by primaquine for treatment of plasmodium vivax malaria in Thailand. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1999 Nov;93(6):637-40. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(99)90079-2, PMID 10717754.

Blanshard A, Hine P. Atovaquone proguanil for treating uncomplicated plasmodium falciparum malaria. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 Jan 15;1(1):CD004529. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004529.pub3, PMID 33459345.

White N. Antimalarial drug resistance and combination chemotherapy. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1999 Apr 29;354(1384):739-49. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1999.0426, PMID 10365399.

Schrezenmeier E, Dorner T. Mechanisms of action of hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine: implications for rheumatology. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2020;16(3):155-66. doi: 10.1038/s41584-020-0372-x, PMID 32034323.

Baird JK, Hoffman SL. Primaquine therapy for malaria. Clin Infect Dis. 2004 Nov;39(9):1336-45. doi: 10.1086/424663, PMID 15494911.

Gutman J, Kachur SP, Slutsker L, Nzila A, Mutabingwa T. Combination of probenecid sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine for intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy. Malar J. 2012 Feb 11;11:39. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-11-39, PMID 22321288.

Achan J, Tibenderana JK, Kyabayinze D, Wabwire Mangen F, Kamya MR, Dorsey G. Effectiveness of quinine versus artemether-lumefantrine for treating uncomplicated falciparum malaria in Ugandan children: randomised trial. BMJ. 2009 Jul 21;339:b2763. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2763, PMID 19622553.

Achan J, Talisuna AO, Erhart A, Yeka A, Tibenderana JK, Baliraine FN. Quinine an old anti-malarial drug in a modern world: role in the treatment of malaria. Malar J. 2011 May 24;10:144. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-144, PMID 21609473.

Plowe CV, Kublin JG, Dzinjalamala FK, Kamwendo DS, Mukadam RA, Chimpeni P. Sustained clinical efficacy of sulfadoxine pyrimethamine for uncomplicated falciparum malaria in Malawi after 10 y as first-line treatment: five-year prospective study. BMJ. 2004 Mar 6;328(7439):545. doi: 10.1136/bmj.37977.653750.EE, PMID 14757706.

Markus MB. Safety and efficacy of tafenoquine for plasmodium vivax malaria prophylaxis and radical cure: overview and perspectives. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2021 Sep 8;17:989-99. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S269336, PMID 34526770.

Das S, Saha B, Hati AK, Roy S. Evidence of artemisinin resistant plasmodium falciparum malaria in eastern India. N Engl J Med. 2018 Nov;379(20):1962-4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1713777, PMID 30428283.

LE Minh G, Peshkova AD, Andrianova IA, Sibgatullin TB, Maksudova AN, Weisel JW. Impaired contraction of blood clots as a novel prothrombotic mechanism in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Sci (Lond). 2018 Feb;132(2):243-54. doi: 10.1042/CS20171510, PMID 29295895.

Qiu F, Liu J, MO X, Liu H, Chen Y, Dai Z. Immunoregulation by artemisinin and its derivatives: a new role for old antimalarial drugs. Front Immunol. 2021 Sep 12;12:751772. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.751772, PMID 34567013.

Tiwari MK, Chaudhary S. Artemisinin derived antimalarial endoperoxides from bench side to bedside: chronological advancements and future challenges. Med Res Rev. 2020 Jul;40(4):1220-75. doi: 10.1002/med.21657, PMID 31930540.

Akpa PA, Ugwuoke JA, Attama AA, Ugwu CN, Ezeibe EN, Momoh MA. Improved antimalarial activity of caprol-based nanostructured lipid carriers encapsulating artemether-lumefantrine for oral administration. Afr Health Sci. 2020 Dec 20;20(4):1679-97. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v20i4.20, PMID 34394228.

Guo W, LI N, Ren G, Wang RR, Chai L, LI Y. Murine pharmacokinetics and antimalarial pharmacodynamics of dihydroartemisinin trimer self-assembled nanoparticles. Parasitol Res. 2021 Jul;120(8):2827-37. doi: 10.1007/s00436-021-07208-6, PMID 34272998.

Snow RW, Guerra CA, Noor AM, Myint HY, Hay SI. The global distribution of clinical episodes of plasmodium falciparum malaria. In: Mendis KN, editor. Malaria: biology and disease. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Academic Press; 2009. p. 201-22.

Mandai SS, Francis F, Challe DP, Seth MD, Madebe RA, Petro DA. High prevalence and risk of malaria among asymptomatic individuals from villages with high rates of artemisinin partial resistance in Kyerwa District North Western Tanzania. J Trop Med. 2024 Jun 26;23(1):197. doi:

10.1186/s12936-024-05019-5.Damme W. Malaria control during mass population movements and natural disasters. J Refugee Stud. 2004 Jun 17:145-6.

Al Awadhi M, Ahmad S, Iqbal J. Current status and the epidemiology of malaria in the middle east region and beyond. Microorganisms. 2021 Feb 9;9(2):1-20. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9020338, PMID 33572053.

Elyazar IR, Hay SI, Baird JK. Malaria distribution prevalence drug resistance and control in Indonesia. Adv Parasitol. 2011;74:41-175. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385897-9.00002-1, PMID 21295677.

Woodbury DJ, Miller C. Nystatin induced liposome fusion a versatile approach to ion channel reconstitution into planar bilayers. Biophys J. 1990 Apr;58(4):833-9. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(90)82429-2, PMID 1701101.

Venugopal K, Hentzschel F, Valkiunas G, Marti M. Plasmodium asexual growth and sexual development in the haematopoietic niche of the host. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2020 Mar 18;18(3):177-89. doi: 10.1038/s41579-019-0306-2, PMID 31919479.

Breman JG, Alilio MS, White NJ. Defeating malaria in Asia the pacific Americas middle east and Europe. 1st ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2011. p. 203-20.

Warrell DA, Gilles HM, editors. Essential malariology. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2002. p. 122-43.

Carter R, Mendis KN. Evolutionary and historical aspects of the burden of malaria. 1st ed. Bethesda: National Institutes of Health; 2002. p. 78-102.

Wernsdorfer WH, McGregor I, Editors. Malaria: principles and practice of malariology. 2nd ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1988. p. 45-67.

Ashley EA, White NJ, Krishna S. The pathophysiology of malaria. 3rd ed. Berlin: Springer; 2014. p. 101-34.

Snow RW, Omumbo JA. Malaria. In: Warrell DA, Cox TM, Firth JD, editors. Oxford textbook of medicine. 5th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2010. p. 960-70.

White NJ, Nosten F. Malaria treatment and control: principles and practice. In: Mansons tropical diseases. 23rd ed. London: Elsevier; 2014. p. 178-90.

Van Den Berg H, Kyaw A, Huxley R. Global burden of disease due to malaria. In: Allen D, editor. Global health and diseases: current trends. 1st ed. New York: Wiley; 2018. p. 100-30.

Tiwari MK, Chaudhary S. Artemisinin derived antimalarial endoperoxides from bench side to bed side: chronological advancements and future challenges. In: Sharma V, editor. Antimalarial drug development: challenges and opportunities. 1st ed. Berlin: Springer; 2020. p. 112-45.

Baird JK, Sudimac W. Malaria in Indonesia: epidemiology and control strategies. In: Kurniawan M, Editor. Tropical infectious diseases: principles pathogens and practice. 1st ed. Jakarta: University of Indonesia Press; 2015. p. 305-20.

Gething PW, Smith DL, Patil AP. A new approach to malaria mapping and model selection. In: Smith DL, Editor. Malaria: progress and prospects. 1st ed. New York: Springer; 2011. p. 155-80.

Cotter C, Sturrock HJ, Hsiang MS, Liu J, Phillips AA, Hwang J. The changing epidemiology of malaria elimination: new strategies for new challenges. In: Hay SI, Guerra CA, Tatem AJ. editors. Malaria: a global perspective. 1st ed. London: Imperial College Press; 2016. p. 79-97.

Kahn K, Collinson MA, Sayed R. Health and demographic surveillance in the agincourt health and socio-demographic surveillance system. In: Dorrington R, Bradshaw D, editors. The epidemiology of malaria in South Africa: a review. 1st ed. Cape Town: South African Medical Research Council; 2014. p. 45-60.

Sharma A, Patel T. Agents in clinical and pre-clinical for treatment of malaria. Advances in antimalarial research. 3rd ed. Boston: Global Health Press; 2024. p. 102-4.

McIntosh HM, Olliaro P. Artemisinin derivatives for treating uncomplicated malaria. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000 Apr;1999(2):CD000256. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000256, PMID 10796519.

Elizabeth A Ashley, Aung Pyae Phyo, Charles J Woodrow. Malaria WNJ. Lancet. 2018 Apr;391(10130):299-310.

Siqueira Neto JL, Wicht KJ, Chibale K, Burrows JN, Fidock DA, Winzeler EA. Antimalarial drug discovery: progress and approaches. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2023 Oct 22;22(10):807-26. doi: 10.1038/s41573-023-00772-9, PMID 37652975.

Tse EG, Korsik M, Todd MH. The past present and future of anti-malarial medicines. Malar J. 2019 Mar 18;18(1):93. doi: 10.1186/s12936-019-2724-z, PMID 30902052.

Dondorp A, Nosten F, Stepniewska K, Day N, White N, South East Asian Quinine Artesunate Malaria Trial (SEAQUAMAT) Group. Artesunate versus quinine for treatment of severe falciparum malaria: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9487):717-25. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67176-0, PMID 16125588.

Gamo FJ, Sanz LM, Vidal J, DE Cozar C, Alvarez E, Lavandera JL. Thousands of chemical starting points for antimalarial lead identification. Nature. 2010;465(7296):305-10. doi: 10.1038/nature09107, PMID 20485427.

Alaithan H, Kumar N, Islam MZ, Liappis AP, Nava VE. Novel therapeutics for malaria. Pharmaceutics. 2023 Jun 15;15(7):1800. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics15071800, PMID 37513987.

Chu CS, Hwang J. Tafenoquine: a toxicity overview. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2021;20(3):349-62. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2021.1859476, PMID 33306921.

Maiga FO, Wele M, Toure SM, Keita M, Tangara CO, Refeld RR. Artemisinin based combination therapy for uncomplicated plasmodium falciparum malaria in mali: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Malar J. 2021 Aug 20;20(1):356. doi: 10.1186/s12936-021-03890-0, PMID 34461901.

Gamo FJ, Sanz LM, Vidal J, DE Cozar C, Alvarez E, Lavandera JL. Thousands of chemical starting points for antimalarial lead identification. Nature. 2010 May 20;465(7296):305-10. doi: 10.1038/nature09107, PMID 20485427.

Charman SA, Andreu A, Barker H, Blundell S, Campbell A, Campbell M. An in vitro toolbox to accelerate anti-malarial drug discovery and development. Malar J. 2020 Aug;19(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s12936-019-3075-5, PMID 31898492.

Akinbo OF. Safety and efficacy of pyramax in uncomplicated Malaria. J Infect Dis. 2022 Mar;225(6):1061-8.

Schmitt M. Methylene blue and its derivatives in the treatment of malaria. Curr Pharmacol Rep. 2017 Jan 3;1:20-5.

White NJ. Antimalarial drug resistance. In: Denny P, editor. Malaria: global status and challenges. 1st ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. p. 15-34.

Rieckmann KH, Davis DR, Hutton DC. Drug resistance in plasmodium falciparum: a new challenge for malaria control. In: Wernsdorfer WH, McGregor I, editors. Malaria: principles and practice of malariology. 2nd ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1988. p. 775-93.

Chethan Kumar HB, Hiremath J, Yogisharadhya R, Balamurugan V, Jacob SS, Manjunatha Reddy GB. Animal disease surveillance: its importance & present status in India. Indian J Med Res. 2021;153(3):299-310. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_740_21, PMID 33906992.

Okech B, Muga H, Nyabera J. Factors influencing the effectiveness of malaria treatment in rural Kenya. Malar J. 2022 Mar 21;1:123.

Dondorp AM, Nosten F, YI P, Das D, Phyo AP, Tarning J. Artemisinin resistance in plasmodium falciparum malaria. N Engl J Med. 2009 Jul;361(5):455-67. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808859, PMID 19641202.

Njaria PM, Okombo J, Njuguna NM, Chibale K. Chloroquine containing compounds: a patent review (2010-2014). Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2015 Jun 25;25(9):1003-24. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2015.1050791, PMID 26013494.

Mariano RM, Goncalves AA, Oliveira DS, Ribeiro HS, Pereira DF, Santos IS. A review of major patents on potential malaria vaccine targets. Pathogens. 2023 Feb 3;12(2):247. doi: 10.3390/pathogens12020247, PMID 36839519.

Costantini C, Aisien MS, Bogh C. Malaria vector control in West Africa: current status and future perspectives. Malar J. 2015 Sep 14;218.

Nguetse CN, Tchoua R, Djouaka R. The role of insecticide resistance in malaria transmission dynamics: a systematic review. PLOS Negl Trop Dis. 2020 May 14;5.

Tayade NG, Nagarsenker MS. Development and evaluation of artemether parenteral microemulsion. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2010 Sep;72(5):637-40. doi: 10.4103/0250-474X.78536, PMID 21694999.

Lin J, LI T, Yang Y. Advances in the research of malaria vaccines. Infect Dis Pover. 2020 Mar 9;1:19.

Arendse LB, Wyllie S, Chibale K, Gilbert IH. Plasmodium kinases as potential drug targets for malaria: challenges and opportunities. ACS Infect Dis. 2021 Mar 12;7(3):518-34. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.0c00724, PMID 33590753.

Gohain M, Malefo MS, Kunyane P, Scholtz C, Burah S, Zitha A. Process development for the manufacture of the antimalarial amodiaquine dihydrochloride dehydrate. Org Pros Res Develop. 2024 Dec 28;1:124-31.

Kokwaro G. Ongoing challenges in the management of malaria. Malar J. 2009 Aug 8;8 Suppl 1(S1):1-6.

Rosenthal PJ. Malaria in 2022: challenges and progress. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2022 Jun;106(6):1565-7. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.22-0128, PMID 35413687.

Umeyor C, Kenechukwu F, Uronnachi E, Chime S, Reginald Opara J, Attama A. Recent advances in particulate antimalarial drug delivery systems: a review. Int J Drug Deliv. 2013 Jan;5(1):1-14.

Mendis KN, Sina BJ, Marchesini P, Carter R. The neglected burden of plasmodium vivax malaria. In: Snow RW, Guerra CA, Tatem AJ. editors. Malaria: a global perspective. 1st ed. London: Imperial College Press; 2016. p. 37-54.

Baird JK. Malaria: overview and impact on public health. In: Warrell DA, Gilles HM, Editors. Essential malariology. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2002. p. 1-20.

Kotepui M, Kirdmanee C, Koonboon S. Advances in malaria diagnosis and treatment: a review. Malar J. 2020 Jan 19;1:335.

Sturrock HJ, Ntshalintshali N, Mthembu DJ. The effect of environmental change on malaria transmission in South Africa: a systematic review. Malar J. 2021 Jan 20;1:201.

Patel DM, Shah HR, Doshi H, Shastri DD. Herbal plants with antimalarial potential: a review. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2018 Jan 11;1:45-50.

Singh MP, Kalita B. Plant based antimalarial agents: an overview. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2020 Mar 12;3:67-72.

Roy R, Biswas P, Mehta S. Antimalarial drug resistance: a growing challenge in India. Int J Curr Pharm Res. 2020 Jan 12;1:33-9.