Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 1, 2025, 161-173Original Article

NETWORK PHARMACOLOGY-BASED COMPUTATIONAL STUDY TO INVESTIGATE THE POTENTIAL MECHANISM OF SYZYGIUM CARYOPHYLLATUM AGAINST COLON CANCER

RAMADEVI PEMMEREDDY1, AJAY MILI1, BHARATH HAROHALLI BYREGOWDA2, JYOTHI GIRIDHAR3, SREEDHARA RANGANATH PAI K.2, ANNA MATHEW1, VASUDEV PAI1, CHANDRASHEKAR K. S.1*

1,2Department of Pharmacognosy, Manipal College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal-576104, Karnataka, India. 3Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, Manipal College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal-576104, Karnataka, India

*Corresponding author: Chandrashekar K. S.; *Email: cks.bhat@manipal.edu

Received: 28 Aug 2024, Revised and Accepted: 04 Nov 2024

ABSTRACT

Objective: Syzygium caryophyllatum, a traditional medicinal plant from the Myrtaceae family, is rich in potential phytoconstituents. Based on its ethnobotanical uses and documented pharmacological activities, present work was conducted to evaluate the probable mechanism of action of S. caryophyllatum to manage colon cancer by integrating network pharmacology and computational studies.

Methods: The plant extract was prepared by Soxhlet extraction method and in vitro screening was performed using Sulforhodamine (SRB) Assay on HT 29 cancer cell lines. We have used super-PRED database, Cytoscape network analyser tool, string database and CytoHubba for performing network analysis for the extract compounds reported in GC-MS analysis. The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway and DAVID databases were used for gene set enrichment analysis. We have used Schrödinger suite Version 11.4's to perform computational studies.

Results: The extract has demonstrated significant in vitro cytotoxic activity (IC50 value is 49.01 µg/ml) and the GC-MS analysis identified seventy-six distinct compounds. The Gene Ontology (GO) and KEGG demonstrated that the shared targets were strongly associated with key processes involved in colon cancer. The current study has identified Estrogen Receptor Alpha (ESR1), Heat Shock Protein 90 Alpha Family Class A Member 1 (HSP90AA1), Mitogen-activated protein kinase 3 (MAP3K), Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) and Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) proteins as essential targets and 5,7-Dihydroxy-2-undecyl-4H-chromen-4-one, 7a,12-Dihydroindolo[2,3-a] quinolizine, 5-hydroxy-7-methoxy-2-methyl-8-(3-methylbutyl) chromen-4-one as key compounds. Docking studies of the compounds with core proteins completely supplemented their binding affinity and suggested strong interactions at the binding site.

Conclusion: These outcomes highlight the multi-target, multi-compound, and multi-pathway approaches of S. caryophyllatum against colon cancer.

Keywords: Syzygium caryophyllatum, GC-MS analysis, SRB assay, Network pharmacology, Molecular docking

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i1.52490 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Cancer is the most commonly occurring disease in the world. In accordance with World Health Organization (WHO) data from 2023 reports, colorectal cancer comes in second in terms of cancer-related fatalities globally, with more than 1.9 million new instances and 930,000 deaths predicted for the disease in 2020. By 2040, there would be 3.2 million new instances of colorectal cancer and 1.6 million deaths annually [1].

The lethality of colon cancer remains a cause for concern, in spite of existence of current therapeutic alternatives, including intensive resection surgeries, radiotherapy, palliative care, neoadjuvant chemotherapies, and intensive laparoscopic surgeries for primary tumors [2, 3]. However natural compounds/agents used as chemotherapeutic medications have shown numerous advantages compared to synthetic ones, mostly due to their lower risk of adverse effects, and greater therapeutic efficacy [4, 5]. Today's most effective and curative anticancer treatments are obtained from plant-based sources. Since the NCI program began, approximately 35,000 plant species have been studied, leading to the development of anticancer medications, including Etoposide analogues, Vincristine, Vinblastine, Camptothecin, Indicine–N-oxide, and Taxol [6].

Syzygium caryophyllatum, belonging to the family Myrtaceae, is a folkloric herb. The tender leaves of this plant have been used traditionally in India to cure wounds, ulcers, diarrhea, and stomatitis [7]. The traditional practitioners in Sri Lanka use this plant for treatment of diabetes mellitus and inflammation [8]. Studies conducted on this plant revealed that the plant has shown antimicrobial activity [9], antidiabetic [10, 11], antioxidant and anticancer activities [12]. The anticancer study conducted on the methanolic extract of S. caryophyllatum plant by rohit et al. has led to the isolation of few phytocompounds such as 3,7-Dihydroxy-4-methoxy flavones, quercetin, and 6,4 dihydroxy 3’propen chalcone, claimed to possess cytotoxic activity on HeLa cancer cell lines [12], However, It's yet unclear how the therapeutic targets and the beneficial phytoconstituents interact. Additionally, there may be some undiscovered chemical moieties present in the plant that may have anticancer activities.

The current strategy of drug discovery, which focuses on using one medicine to treat one specific ailment, is currently encountering significant problems in terms of safety, effectiveness, and long-term survivability. Bioinformatics advancements have transformed medication design and discovery by integrating network biology and polypharmacology to create medicines targeting multiple diseases. Network pharmacology, a combination of network biology and polypharmacology has evolved as an efficient method for elucidating the pharmacological mechanisms underlying multitarget drugs in a variety of disorders [13, 14].

In the current investigation, the ethanolic extract of S. caryophyllatum leaves was screened using the Sulforhodamine (SRB) Assay and then subjected to GC-MS analysis to identify the phytoconstituents. Secondly, we predicted the putative active constituents, associated target genes and the pathways of the compounds against colon cancer by network pharmacology. Finally, we conducted docking and simulation studies to evaluate the therapeutic potential of S. caryophyllatum plant constituents in Colon cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of ethanolic leaf extract

The leaves of S. caryophyllatum were collected from Manipal, Karnataka, India in the month of March to August and authenticated. The voucher specimen (PP 652) was deposited in Manipal College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Department of Pharmacognosy. The leaves of the plant S. caryophyllatum were shade-dried, coarsely ground, and then extracted using ethanol in a Soxhlet extractor, the excess solvent was extracted and concentrated.

Evaluation of cytotoxic activity by SRB assay

To test the cytotoxicity of the extract, 5,000 cells per well were seeded in 96-well plates using 100 µl media. Following a 24-hour period of cell seeding, the cells were exposed to treatment with extract at various concentrations (500 to 15.62 µg/ml). Meanwhile, cells that were not exposed to any treatment were added with an equivalent volume of media, functioning as the control group. Using the SRB assay, cell growth inhibition was performed following a 48 h incubation period. The cell monolayer formed is coloured for 60 min after being fixed with 10% trichloroacetic acid. Following the incubation period, trichloroacetic acid was removed and the wells were dried after three rounds of washing with distilled water. 100 µl** of 0.057% sulforhodamine B solution in acetic acid (1% v/v) was added, kept in dark for 30 min. 200 µl** of Tris base (10 mmol) was added to the wells to dissolve the dye bound to the protein. A multiplate reader (BioTek Instruments Inc. ELx800) was used to examine the absorbance at 540 nm. The IC50 values were calculated using graph pad prism 7 [15, 16].

GC-MS analysis

GC-MS Analysis of S. caryophyllatum extract was analysed using GC/MS Clarus 500 (Perkin Elmer) equipment coupled with Restek RtxR – 5 column having dimensions of 30 mm X 0.25 mm. The oven temperature was set as follows: 40 degrees Celsius for 5 min, then gradually increased to 280 degrees Celsius after 15 min and the injector was set to 280 degrees Celsius. The chemicals were identified using the National Institute Standard and Technology (NIST) database coupled with the GC-MS instrument.

Prediction of compound targets and colon cancer targets

Total 76 compounds obtained from GC-MS analysis of the extract (after removing the duplicates) are selected for network pharmacology. The probable targets were identified using Super-PRED, an online compound target prediction engine. The PubChem Compound names were used as search input. Uniprot ID mapping tool was then used to match the predicted chemical targets to their standard gene names [17]. Gene Cards database was used to find the Colon cancer target genes using the phrase "Colon cancer" with a relevance score ≥20 [18].

Building a protein-protein interaction (PPI) network

The PPI network was depicted by Cytoscape v3.10.1. and its topological parameters were examined using Cytoscape Network Analyzer tool [19]. Using the String database v2.0.1, the PPI network of shared targets between the active drugs and colon cancer was constructed; a confidence score of 0.7 is determined as the optimum score. The software extension CytoHubba was subsequently employed to compute the hub targets based on network node's topological characteristics and target genes [20].

Gene set enrichment analysis

Enrichment analysis was performed using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway (updated 1st May 2021) and DAVID ver. 6.8 was used to perform pathway and functional annotation [21].

Molecular docking studies

Molecular docking investigations were conducted to comprehend the mechanism of binding of the chemical constituents discovered in S. caryophyllatum to five hub Colon cancer targets, identified by network pharmacology. For the study, the modules of Schrödinger suite Version 11.4's were utilized.

The co-crystallized protein-ligand complex structures of colon cancer targets namely Estrogen Receptor Alpha (ESR1), Heat Shock Protein 90 Alpha Family Class A Member 1 (HSP90AA1), Mitogen-activated protein kinase 3 (MAP3K), Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR), Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), bearing PDB ID’s 5GTR, 4BQG, 2ZOQ, 6VHN and 6NJS, respectively were downloaded from RCSB protein data bank. The protein structure was processed using "protein preparation wizard" in the Schrodinger suite. It consists of subsequent phases: “import and process”, “review and modify”, and “refine”. The missing atoms and the sidechains were substituted using Prime tool during the initial stage, required pH adjustments were made for individual proteins, following this, the hydrogen bonds were optimized and assigned and water molecules larger than 3 Å were eliminated. A low-energy state protein was generated through Restrain minimization utilizing the “OPLS3e (optimization potential for liquid simulation) force field”. The energy optimization methodology employed in this stage of protein preparation generates the protein in its most energy-efficient state, thereby facilitating subsequent in silico investigations [22]. Utilizing the "Receptor grid generation" interface, a grid representing the chosen protein structures was generated [23]. The structures of the compounds were downloaded from the PubChem database. The “LigPrep” tool was used to prepare ligands. Structures with the lowest energy and associated chirality at pH specific to the proteins were built using the OPLS3e force field. Tautomerization, H-bond addition, ionization Epik, neutralization of charged group, and optimisation of ligand geometry were performed for all the selected ligands [24]. The "Glide module" was utilized for all docking experiments. The Glide module attached prepared ligands on the protein's selected site. In extreme precision (XP) mode, prepared ligands were docked and docking score was calculated [25].

ADME analysis

The docking score, ligand interactions were utilized to determine the five most optimal ligands for each protein. The QikProp tool was used to perform ADME analysis. Using this procedure, the following parameters were established: QPlogPo/w (predicted octanol/water coefficient), QPlogBB (predicted brain/blood partition coefficient), QPlogS (predicted aqueous solubility), QPPCaco (cell permeability), QPlogHERG (cardiotoxicity), and Lipinski's rule of five [26, 27].

Induced-fit docking studies (IFD)

The IFD procedure involved specification of 20 poses for an individual ligand and 0.50 Van der Waals scaling. Energy minimization and estimation of the Prime side chain were subsequently conducted. Every residue in the side chain and ligand conformation was refined to a value of 5 Å. All ligand poses were docked thoroughly, and IFD was determined for each pose [28].

Molecular dynamic simulations (MDS)

Protein-ligand complex dynamics and functionality can often be studied using MDS. Based on the ADME profile, IFD data, and ligand docking score, one compound for each protein will be chosen for MDS. Before starting the MDS, the complete system was submerged in a simple point charge/E solvent model. The counter ions were included to maintain overall electrical neutrality. The buffer box size calculation procedure was applied during the building process; the distance (Å) was a = 10, b = 10, and c = 10, and the corresponding angles were α = 90, β = 90, and γ = 90. The system was configured for MD simulation using the System Builder tool, with the OPLS2005 force field being used constantly throughout the procedure. For system minimization, a minimization tool was employed. Simulation time was set to 100 ns with one frame taken from the trajectory every 100 picoseconds, and 1000 frames produced throughout the process. The NPT ensemble (constant particle number (N), pressure (P) 1.01325 bar, and temperature (T) 310 K) was utilized in the production run, with the force field being OPLS2005. Finally, MDS report was created using the Simulation interaction diagram [29, 30].

RESULTS

SRB assay and GC-MS results

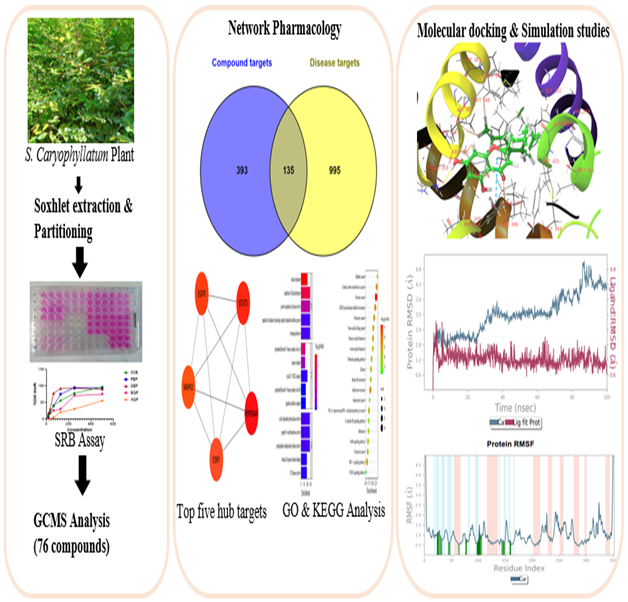

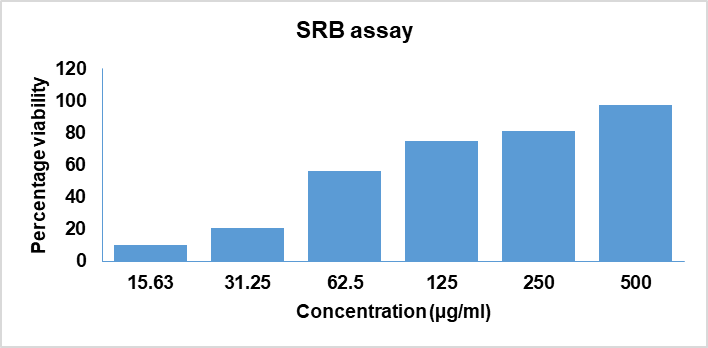

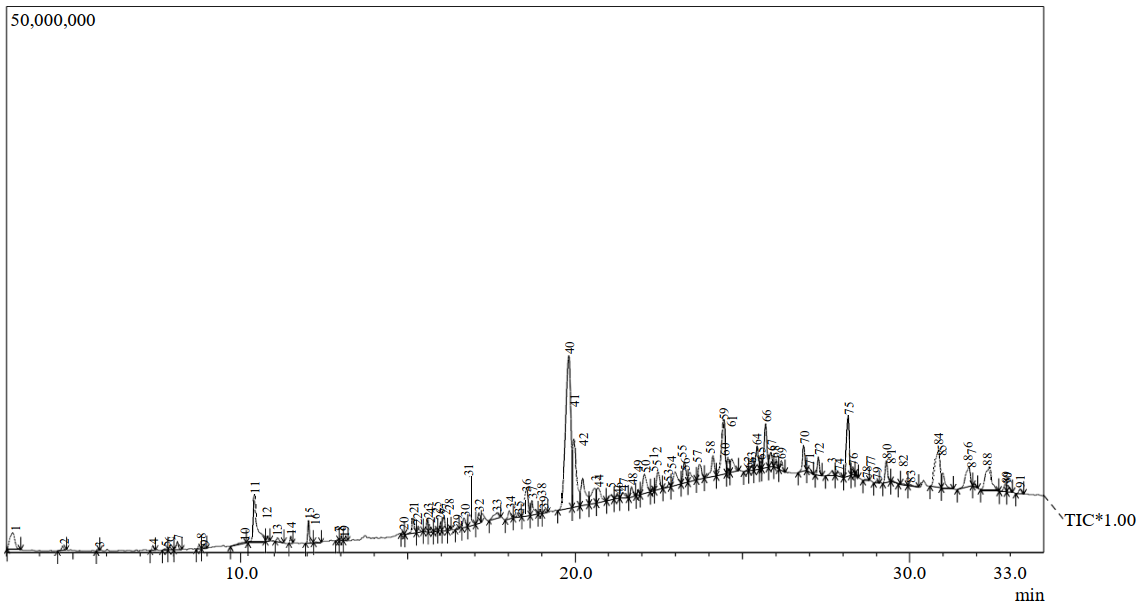

The experimental procedure is depicted in fig. 1. The extract is assessed for cytotoxicity by SRB assay on HT-29 cancer cell lines. The extract has demonstrated a significant and dose-dependent cytotoxic effect (IC50 value of 49.01 µg/ml). The fig. 2 illustrates the viability of HT-29 cell lines following treatment with S. caryophyllatum leaf extract at various concentrations. GC-MS chromatogram of the extract, shown in fig. 3 confirmed the presence of 76 compounds. Table 1 illustrates the names of the compounds, retention times and percentage area.

Fig. 1: The framework of study

Fig. 2: Cell viability of S. caryophyllatum ethanolic extract at various concentrations on HT-29 cancer cell lines

Fig. 3: GCMS Chromatogram of S. caryophyllatum leaf extract

Table 1: GC-MS data of S. caryophyllatum plant leaf extract

| Peak no | Name of the compound | CID | Retention time | Percentage area |

| 1 | 7-Tetradecenal, (Z)- | CID: 5364468 | 3.193 | 1.89 |

| 2 | Glycerin | CID: 753 | 4.683 | 0.26 |

| 3 | 2-Pyrrolidinone, 1-methyl- | CID: 13387 | 5.746 | 0.07 |

| 4 | Ethyl hydrogen succinate | CID: 70610 | 7.38 | 0.18 |

| 5 | 5-Hydroxymaltol | CID: 70627 | 7.738 | 0.08 |

| 6 | 1,2-Benzenediol | CID: 289 | 7.887 | 0.13 |

| 7 | Benzofuran, 2,3-dihydro- | CID: 10329 | 8.114 | 0.39 |

| 8 | Butanedioic acid, hydroxy-, diethyl ester, (.+/-.)- | CID: 24197 | 8.757 | 0.16 |

| 9 | Malic Acid | CID: 525 | 8.906 | 0.07 |

| 10 | Hexadecanoic acid, 2,3-dihydroxypropyl ester | CID: 14900 | 10.094 | 0.24 |

| 11 | 1,2,3-Benzenetriol | CID: 1057 | 10.4 | 4.44 |

| 12 | 3,5-Dimethyl-1-dimethylphenylsilyloxybenzene | CID: 532641 | 10.747 | 0.24 |

| 13 | Trehalose | CID: 7427 | 11.112 | 0.28 |

| 14 | 5-Isopropenyl-3-isopropyl-2,2-dimethyl-2,5-dihydrofuran | CID: 596568 | 11.497 | 0.27 |

| 15 | Butylated Hydroxytoluene | CID: 31404 | 12.035 | 0.88 |

| 16 | Eicosane | CID: 8222 | 12.243 | 0.08 |

| 17 | 1-Chloroeicosane | CID: 39150 | 12.932 | 0.06 |

| 18 | Methyl 9-(2-[(2-butylcyclopropyl)methyl]cyclopropyl)nonanoate | CID: 544392 | 12.983 | 0.08 |

| 19 | N-Methyl-3,5-dihydroxyaniline | CID: 587240 | 13.115 | 0.08 |

| 20 | Tricyclo [3.1.0.0(2,4)] hexane, 3,3,6,6-tetraethyl-, trans-- | CID: 572173 | 14.842 | 0.07 |

| 21 | (1E)-2-(2,2,6-Trimethyl-7-oxabicyclo [4.1.0]hept-1-yl)-1-propenyl acetate | CID: 5363712 | 15.153 | 0.97 |

| 22 | 2-Cyclohexen-1-one, 4-hydroxy-3,5,6-trimethyl-4-(3-oxo-1-butenyl)- | CID: 5371378 | 15.309 | 0.33 |

| 23,26,27 | cis-9-Hexadecenal | CID: 5364643 | 15.576, 15.982, 16.078 | 3.54 |

| 24 | 2-Pentadecanone, 6,10,14-trimethyl- | CID: 10408 | 15.643 | 0.3 |

| 25 | Stigmasta-5,24(28)-dien-3-ol, (3 beta) | CID: 5281326 | 15.831 | 0.11 |

| 28,31 | l-(+)-Ascorbic acid 2,6-dihexadecanoate | CID: 54722209 | 16.245, 16.837 | 2.46 |

| 29 | tert-Hexadecanethiol | CID: 109858 | 16.457 | 0.07 |

| 30 | Cyclopentadecanone, 2-hydroxy-$$ 2-Hydroxycyclopentadecanone | CID: 543400 | 16.678 | 0.58 |

| 32 | Hexadecanoic acid, ethyl ester | CID: 12366 | 17.123 | 0.61 |

| 33 | Cholest-5-en-3-ol (3. beta.)- | CID: 5997 | 17.663 | 0.67 |

| 34 | 9-Undecen-2-one, 6,10-dimethyl- | CID: 102604 | 18.033 | 0.47 |

| 35,36 | Phytol | CID: 5280435 | 18.288, 18.383 | 0.76 |

| 37 | Octadecanoic acid | CID: 5281 | 18.708 | 0.93 |

| 38 | Octadecanoic acid, ethyl ester | CID: 8122 | 18.964 | 0.09 |

| 39 | 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid (Z, Z)-, 2,3-dihydroxypropyl ester | CID: 5283469 | 19.076 | 0.15 |

| 40 | E, Z-1,3,12-Nonadecatriene | CID: 5365680 | 19.808 | 18.41 |

| 41 | Methyl alpha linolinate | CID: 5319706 | 19.957 | 6.04 |

| 42, 43 | Gamma.-Tocopherol | CID: 92729 | 20.223, 20.583 | 4.59 |

| 44,54,66,75 | Gamma.-Sitosterol | CID: 457801 | 20.682, 22.985, 25.689, 28.156 | 9.6 |

| 45 | Cholestane-3,6-diol, (3. beta.,5. alpha.,6. alpha.,17. alpha.,20S)- | CID: 22213509 | 21.054 | 0.47 |

| 46 | E, E, Z-1,3,12-Nonadecatriene-5,14-diol | CID: 5364768 | 21.268, 25.284, 25.846 | 1.46 |

| 47 | Linoleoyl-rac-glycerol | CID: 5365676 | 21.418 | 0.47 |

| 48 | Tetracosamethyl-cyclododecasiloxane | CID: 167767 | 21.682 | 0.62 |

| 49 | 2,6,10,14,18,22-Tetracosahexaene, 2,6,10,15,19,23-hexamethyl-, (all-E)- | CID: 638072 | 21.887 | 0.25 |

| 50,57,69 | Vitamin E acetate $$ dl-. alpha.-Tocopherol acetate | CID: 2117 | 22.071, 23.718, 26.16 | 3.5 |

| 51 | 9-Octadecenoic acid, 1,2,3-propanetriyl ester, (E, E, E)- | CID: 5364673 | 22.342 | 0.13 |

| 52 | Ergost-5-en-3-ol, (3. beta.)- | CID: 5283637 | 22.477, 24.119 | 3.19 |

| 53 | 2,6-Heptadienal, 2,4-dimethyl- | CID: 5370098 | 22.819 | 0.25 |

| 55 | Stigmasterol | CID: 5280794 | 23.269 | 1.54 |

| 56 | 2H-1-Benzopyran-6-ol, 3,4-dihydro-2,8-dimethyl-2-(4,8,12-trimethyltridecyl)-, [2R-[2R* | CID: 12444418 | 23.429 | 0.74 |

| 59 | Lanosterol | CID: 246983 | 24.427 | 4.34 |

| 60 | Beta.-Tocopherol | CID: 6857447 | 24.566 | 0.9 |

| 61 | Stigmasta-4,22-dien-3. beta.-ol | CID: 15215516 | 24.681, 27.269 | 2.05 |

| 62 | Stigmast-5-en-3-ol, oleate | CID: 20831071 | 25.152 | 0.1 |

| 64 | Alpha-tocopherol-beta-D-mannoside | CID: 597057 | 25.435 | 1.5 |

| 65 | 4,4,8-Trimethyl-non-5-enal | CID: 5365831 | 25.535 | 0.31 |

| 68 | Triacontane, 1-bromo- | CID: 521082 | 26.01 | 0.41 |

| 70 | Lupeol | CID: 259846 | 26.831 | 1.5 |

| 71 | Cholestanol | CID: 6665 | 26.981 | 0.28 |

| 73 | Linoleic acid ethyl ester | CID: 5282184 | 27.671 | 0.33 |

| 74 | (R)-(-)-14-Methyl-8-hexadecyn-1-ol | CID: 10944926 | 27.865 | 0.26 |

| 76 | Stigmastanol | CID: 241572 | 28.296 | 0.33 |

| 77 | Fucosterol | CID: 5281328 | 28.399 | 0.15 |

| 78,81 | 9,19-cyclolanost-24-en-3-ol, (3 beta)- | CID: 129660864 | 28.696, 29.484 | 0.1 |

| 79 | Dihydrochondrillaterol | CID: 5283639 | 29.006 | 0.09 |

| 80 | 12-oleanen-3yl acetate, (3 alpha)- | CID: 45044112 | 29.297 | 1.24 |

| 82 | 2,3-Benzocyclododecenedimethanol, 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14-tetradecahydro-, (2 | CID: 569165 | 29.792 | 0.13 |

| 83 | alpha-Amyrin acetate | CID: 293754 | 30.021 | 0.12 |

| 84 | 2-Ethyl-4-(2-methylcyclohexyl)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-4H-1,3,2-benzodioxaborinine | CID: 609622 | 30.861 | 4.59 |

| 85 | 5,7-Dihydroxy-2-undecyl-4H-chromen-4-one | CID: 5375797 | 30.987 | 1.03 |

| 86 | Dihydroindolo[2,3-a] quinolizine | CID: 613040 | 31.772 | 2.28 |

| 87 | 4-Methyl-1-(2,6,6-trimethyl-2-cyclohexen-1-yl) pent-1-en-3-one | CID: 5376281 | 31.93 | 0.09 |

| 88 | 5-hydroxy-7-methoxy-2-methyl-8-(3-methylbutyl)chromen-4-one | CID: 613101 | 32.384 | 3.4 |

| 89 | 2-piperaine-4-amino-6,7-dimethoxyquinaoline | CID: 616267 | 32.848 | 0.54 |

| 90 | D; B-Friedo-B; A-neogammacer-5-en-3-ol, (3-beta)- | CID: 12442794 | 32.934 | 0.37 |

| 91 | Friedelan-3-one | CID: 91472 | 33.296 | 0.31 |

CID: Compound identifier

Network pharmacology analysis

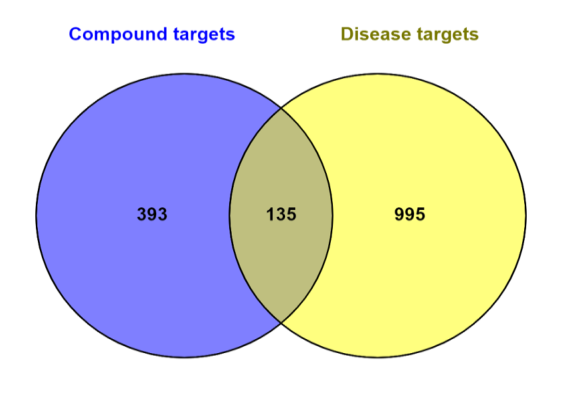

Network Pharmacology has been performed for the 76 chemicals found in the extract and the putative targets of the Colon cancer. The Super-PRED server identified a total of 528 distinct targets from 76 compounds found in the S. caryophyllatum plant leaf extract. In the same manner, A total of 1131 targets relevant to colon cancer were found, having a relevance threshold score of 20 or above. A total of 135 overlapping targets between the chemicals and the Colon cancer were determined using an online Venn Diagram tool shown in fig. 4A.

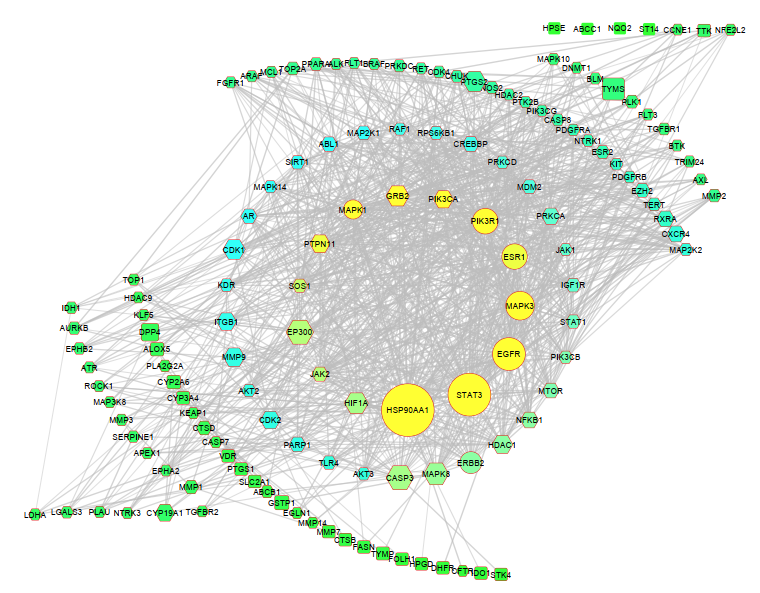

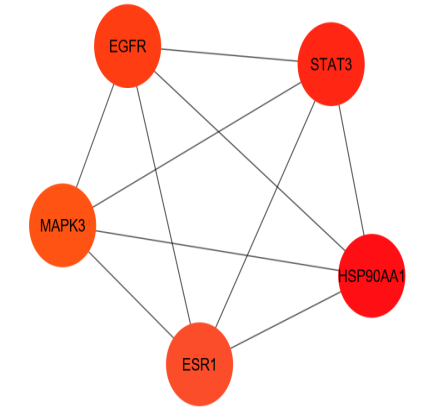

A PPI network was constructed utilizing String Database v2.0.1 to reveal the interactive connection among the 135 shared targets. In the PPI network, all 135 targets displayed interactions with a confidence score exceeding 0.70. In this experimental investigation, the degree of a node denotes the count of its immediate neighbours. It is widely accepted that the influence exerted by a node increases in proportion to the number of nodes that are directly connected to it. Betweenness centrality quantifies the shortest path traversed by a given node between every pair of nodes. Closeness centrality is a metric that quantifies the centrality of a node in a network [31]. A higher number of closeness centrality denotes a greater centrality of node, suggesting that signals are transmitted more quickly from that node to other nodes. As shown in fig. 4B, the degree of interaction between the targets is represented by the distinct colours of the nodes of PPI network (green ˂ blue˂ yellow), the size of the nodes shows their betweenness centrality, and their shape shows their closeness centrality (Square ˂hexagon ˂circle). The network consisted of 135 nodes and 962 edges. The CytoHubba software was used to determine the network's five most important targets, as determined by the degree of interactions, betweenness centrality and closeness centrality; the targets are HSP90AA1, STAT3, EGFR, MAPK3 and ESR1(fig. 4C). Table 2 represents the data values of top five targets of network analysis.

A

B

C

Fig. 4: (A) Venn diagram depicts the most commonly targeted genes for chemical compounds and disease. (B) PPI network of 135 colon cancer targets of S. caryophyllatum. (C) The top five targets of PPI networks

Table 2: Data values of top five targets of network analysis

| Protein name | Degree | Betweenness centrality | Closeness centrality |

| HSP90AA1 | 60 | 0.12588496 | 0.610328638 |

| STAT3 | 55 | 0.09496326 | 0.616113744 |

| EGFR | 45 | 0.060568805 | 0.587777778 |

| MAPK3 | 45 | 0.053612779 | 0.580357143 |

| ESR1 | 44 | 0.040844799 | 0.555555556 |

The DAVID ver 6.8 database was used to perform GO analysis on 135 gene targets. There were 567 identified biological processes (BP), 86 cell compositions (CC), and 150 molecular functions (MF). Based on fold enrichment values (P ˂ 0.01), the top five BP, CC, and MF were chosen and are listed in table 3. BPs were primarily associated with regulation of Golgi inheritance, positive regulation of cyclase activity and control of APC-dependent catabolic process in colon cancer. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) complex-class IA caspase complex, cyclin E1-CDK2 complex, PI3K complex-class IB, peptidase inhibitor complex is among the CCs. The MF are primarily involved in cyclin-dependent protein kinase activity, peptide N-acetyltransferase activity, prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase activity, vitamin D response element binding, JUN kinase activity. The KEGG pathway evaluation of the shared targets identified the specific path in which the common targets are significantly enriched. The top 20 signalling pathways include various cancer-related pathways: prolactin, Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), Fc epsilon RI, Erythroblastic leukaemia viral oncogene homologue (ErbB), Hypoxia-Inducible Factor (HIF-1), and EGFR signalling pathways (table 3).

Table 3: GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of S. caryophyllatum compound targets

| ID | Category | Description | Fold enrichment | P value | Count |

| GO: 0060440 | GO Biological Process | Trachea formation | 102.7195767 | 7.47e-08 | 5 |

| GO: 0090170 | GO Biological Process | Regulation of Golgi inheritance | 143.8074074 | 1.28e-06 | 4 |

| GO: 0031281 | GO Biological Process | Positive regulation of cyclase activity | 143.8074074 | 1.41e-04 | 3 |

| GO: 1905784 | GO Biological Process | Regulation of anaphase-promoting complex-dependent catabolic process | 143.8074074 | 0.013757 | 2 |

| GO: 0036269 | GO Biological Process | Swimming behaviour | 143.8074074 | 0.013757 | 2 |

| GO: 0097134 | GO Cell Compositions | Cyclin E1-CDK2 complex | 101.8469136 | 0.019366 | 2 |

| GO: 1904090 | GO Cell Compositions | Peptidase inhibitor complex | 76.38518519 | 0.025739 | 2 |

| GO: 0005944 | GO Cell Compositions | Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complex, class IB | 76.38518519 | 0.025739 | 2 |

| GO: 0005943 | GO Cell Compositions | Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complex, class IA | 67.89794239 | 2.19e-05 | 4 |

| GO: 0008303 | GO Cell Compositions | Caspase complex | 65.47301587 | 8.61e-04 | 3 |

| GO: 0004666 | GO Molecular Functions | Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase activity | 140.3333333 | 0.014097 | 2 |

| GO: 0034212 | GO Molecular Functions | Peptide N-acetyltransferase activity | 140.3333333 | 0.014097 | 2 |

| GO: 0097472 | GO Molecular Functions | Cyclin-dependent protein kinase activity | 140.3333333 | 0.014097 | 2 |

| GO: 0004705 | GO Molecular Functions | JUN kinase activity | 93.55555556 | 0.021071 | 2 |

| GO: 0070644 | GO Molecular Functions | Vitamin D response element binding | 93.55555556 | 0.021071 | 2 |

| hsa05219 | KEGG Pathways | Bladder cancer | 23.64085 | 4.82e-16 | 15 |

| hsa05230 | KEGG Pathways | Central carbon metabolism in cancer | 23.07797 | 6.23e-27 | 25 |

| hsa05215 | KEGG Pathways | Prostate cancer | 22.64972 | 7.26e-37 | 34 |

| hsa01521 | KEGG Pathways | EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance | 22.08474 | 1.33e-28 | 27 |

| hsa05212 | KEGG Pathways | Pancreatic cancer | 21.25603 | 6.20e-26 | 25 |

| hsa05223 | KEGG Pathways | Non-small cell lung cancer | 20.64196 | 1.84e-23 | 23 |

| hsa05220 | KEGG Pathways | Chronic myeloid leukemia | 20.40579 | 2.17e-24 | 24 |

| hsa05221 | KEGG Pathways | Acute myeloid leukemia | 20.2535 | 3.65e-21 | 21 |

| hsa04917 | KEGG Pathways | Prolactin signaling pathway | 19.3855 | 9.79e-21 | 21 |

| hsa05214 | KEGG Pathways | Glioma | 18.95471 | 1.58e-21 | 22 |

| hsa05211 | KEGG Pathways | Renal cell carcinoma | 18.72995 | 2.12e-19 | 20 |

| hsa01522 | KEGG Pathways | Endocrine resistance | 18.46238 | 2.60e-27 | 28 |

| hsa05213 | KEGG Pathways | Endometrial cancer | 17.82574 | 4.71e-15 | 16 |

| hsa05235 | KEGG Pathways | PD-L1 expression and PD-1 checkpoint pathway in cancer | 17.42517 | 1.26e-22 | 24 |

| hsa04664 | KEGG Pathways | Fc epsilon RI signaling pathway | 17.10485 | 1.13e-16 | 18 |

| hsa05218 | KEGG Pathways | Melanoma | 17.05206 | 1.35e-17 | 19 |

| hsa04012 | KEGG Pathways | ErbB signaling pathway | 16.72474 | 2.87e-20 | 22 |

| hsa05210 | KEGG Pathways | Colorectal cancer | 16.53027 | 3.74e-20 | 22 |

| hsa04066 | KEGG Pathways | HIF-1 signaling pathway | 16.00637 | 1.60e-24 | 27 |

| hsa04370 | KEGG Pathways | VEGF signaling pathway | 15.33316 | 3.20e-12 | 14 |

GO: Gene ontology, KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes

Molecular docking results

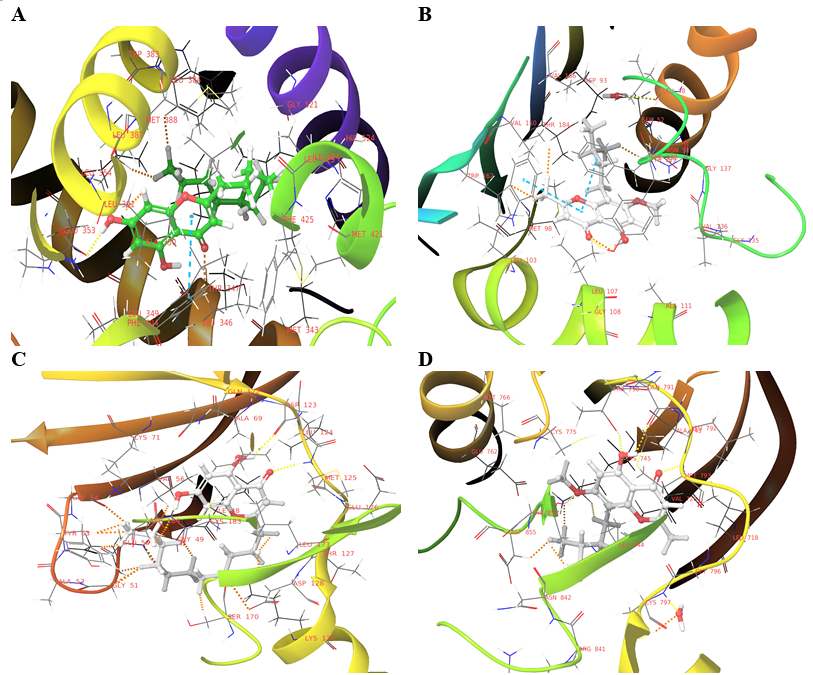

Molecular docking studies were performed to determine the binding affinity of bioactive compounds and the core colon cancer targets. The top five colon cancer target proteins after network pharmacology (5GTR, 4BQG, 2ZOQ, 6VHN and 6NJS) were docked with the 76 compounds of S. caryophyllatum plant. A greater negative docking score indicates high binding affinity of the ligand to the target protein [32]. Table 4 illustrates the docking score and the interactions of ligands with the proteins of the top five compounds for top five targets. The amino acids GLU353, ARG394 and HIE524 are the key target residues of estrogen receptor antagonists [33]. The compound5375797 showed the highest docking score of-11.823 kcal/mol and hydrogen bond interactions with GLU353, ARG 394 residues of 5GTR protein. The key residues LEU48, SER52, ASP93, GLY97, LEU107, PHE138, TYR139, TRP162, THR184 present in the ATPaseN-terminal domain of HSP90AA1 protein form the active site of HSP90AA1 protein [34]. With the residues at the active site, compound 613040 has demonstrated the highest docking score of-10.523 kcal/mol and has established stable H-bond interactions and Pi-Pi interactions. The aminoacids ASP123, MET125, SER170 and ASP184 serves as active sites for MAPK3 inhibitors [35]. The molecule 5375797 forms H-bonds with ASP123, MET125, and ASP184 of the protein 2ZOQ (MAPK3), showed a docking score of-8.130 kcal/mol. The residues THR790, MET793, and CYS797 serve as the active sites for EGFR inhibitors [36, 37]. The compound 5371378 shows hydrogen bonds with THR790 MET793 residues of 6VHN (EGFR) protein. The amino acid residues ARG609, SER611, SER613, SER636, GLU638 present in the SH2 domain of 6NJS protein are the key targets for STAT3 inhibitors [38]. The compound 597057 forms stable H-bond interaction with GLU594, ARG595, SER636 residues with a docking score of-7.542 kcal/mol.

Table 4: Docking score, and interactions of top five compounds for top five target proteins

| Protein | Compound id | Docking score (kcal/mol) | Interactions |

| ESR1 (5GTR) | 5375797 | -11.823 | Hydrogen bond interaction: LEU346, GLU353, ARG 394 |

| 569165 | -11.229 | Hydrogen bond interaction: GLU353, ARG394, Pi-Pi stacking: PHE404 | |

| 5988 | -10.286 | Hydrogen bond interaction: THR347, GLU353, GLY521, HIE524 | |

| 5371378 | -8.324 | Hydrogen bond interaction: LEU346, ARG204 | |

| 5365831 | -7.314 | Hydrogen bond interaction: ARG394 | |

| HSP90AA1 (4BQG) | 613040 | -10.523 | Hydrogen bond interaction: ASP93, PHE 138, Pi-Pi stacking: PHE138 Pi-cation: PHE 138 |

| 5283469 | -8.356 | Hydrogen bond interaction: ASP54, LYS58, PHE138 | |

| 613101 | -7.988 | Hydrogen bond interaction: TYR139, Pi-Pi stacking: PHE138, TRP162 | |

| 616267 | -7.603 | Pi-Pi stacking: PHE138, Pi-cation: PHE138, | |

| 12444418 | -6.757 | Water mediated hydrogen bond interaction: SER52. | |

| MAPK3(2ZOQ) | 5375797 | -8.130 | Hydrogen bond interaction: ASP123, MET125, ASP184 |

| 70627 | -7.0 | Hydrogen bond interaction: GLN122, ASP123, MET125 | |

| 613040 | -6.164 | Hydrogen bond interaction: ASP128, Salt bridge: ASP184 | |

| 14900 | -4.213 | Hydrogen bond interaction: MET125 | |

| 587240 | -3.177 | Hydrogen bond interaction: GLN122, ASP123, MET125 | |

| EGFR (6VHN) | 613101 | -9.302 | Hydrogen bond interaction: LYS745, THR790, GLN791, MET793 |

| 5371378 | -7.202 | Hydrogen bond interaction: THR790, MET793 | |

| 569165 | -7.026 | Hydrogen bond interaction: MET793, Water mediated hydrogen bond interaction: CYS797, ASP800 | |

| 5376281 | -6.308 | Hydrogen bond interaction: MET793 | |

| 616267 | -6.203 | Hydrogen bond interaction: MET793, ASN842, ASP855 | |

| STAT3(6NJS) | 597057 | -7.542 | Hydrogen bond interaction: GLU594, ARG595, SER636 |

| 5988 | -5.202 | Hydrogen bond interaction: LYS591, ARG609, SER636, GLU638 | |

| 587240 | -4.714 | Hydrogen bond interaction: GLN635, SER636, Pi-Pi stacking: TRP623 | |

| 1057 | -4.095 | Hydrogen bond interaction: GLU612, SER613, Pi-cation: LYS591 | |

| 13387 | -3.023 | Hydrogen bond interaction: LYS591, SER636 |

ADME analysis

Drug-like characteristics and ADME properties are important filtration criteria in the drug-design process, and these properties for the top five compounds for each targetted protein were assessed using QikProp tool of maestro module are shown in tables 5 and 6. According to the predicted data, all of the chosen compounds exhibited favorable human oral absorption and both the H-bond donor and acceptor atoms are within the acceptable range. There were no substantial violations of the Lipinski rule of five, with only two compounds, 7427 and 597057, found to violate the rule. With the exception of compound 7427, the Caco-2 permeability of all the compounds was satisfactory (values ˃ 25). The acceptable range for QPlogBB is-3.0 to 1.2, and these values for all the compounds were witin the range. The compound 12444418 has showed higher QlogKhsa and QlogPo/w than the recommended range, while the acceptable range of QlogKhsa and QlogPo/w is-1.5 to 1.5 and-2.0 to 6.5, respectively. The compounds 12444418 and 597057 has shown lower QlogS values than the acceptable limit of-6.5 to 0.5.

Table 5: ADME analysis of compounds

| Compound ID | Molecular weight (g/mol) |

Hydrogen bond donor | Hydrogen bond acceptor | Psa | Metab | % Human oral absorption | Rule of five |

| 569165 | 280.45 | 2 | 3.4 | 44.119 | 6 | 100 | 0 |

| 5375797 | 332.439 | 1 | 3 | 78.349 | 3 | 100 | 0 |

| 7427 | 342.299 | 6 | 16.8 | 186.758 | 8 | 100 | 2 |

| 5371378 | 222.283 | 1 | 4.75 | 75.482 | 3 | 85.653 | 0 |

| 5365831 | 182.305 | 0 | 2 | 38.322 | 2 | 100 | 0 |

| 613040 | 220.273 | 1 | 0.5 | 8.984 | 2 | 100 | 0 |

| 5283469 | 354.529 | 2 | 5.4 | 80.995 | 6 | 100 | 0 |

| 613101 | 276.332 | 0 | 3 | 61.048 | 4 | 100 | 0 |

| 14900 | 330.507 | 2 | 5.4 | 79.764 | 3 | 100 | 0 |

| 616267 | 289.336 | 3 | 6 | 78.823 | 3 | 78.408 | 0 |

| 70627 | 142.111 | 2 | 4 | 79.634 | 3 | 70.818 | 0 |

| 587240 | 139.154 | 3 | 2.5 | 58.879 | 5 | 78.44 | 0 |

| 12444418 | 402.659 | 1 | 1.5 | 28.129 | 3 | 100 | 1 |

| 5376281 | 220.354 | 0 | 2 | 25.854 | 4 | 100 | 0 |

| 597057 | 592.855 | 4 | 10 | 97.374 | 8 | 83.757 | 2 |

| 1057 | 126.112 | 3 | 2.25 | 65.652 | 3 | 73.803 | 0 |

| 13387 | 99.132 | 0 | 3 | 32.942 | 1 | 81.208 | 0 |

Psa: Polar Surface Area, Metab: Number of possible metabolic reactions

Table 6: ADME characteristics

| Compound ID | QPlog Po/w | QPlogS | QPlog HERG | QPP Caco | QP logBB | QPlogKhsa |

| 569165 | 3.368 | -4.4 | -3.544 | 1156.859 | -0.53 | 0.49 |

| 5375797 | 4.867 | -6.391 | -5.931 | 376.67 | -1.849 | 0.871 |

| 7427 | -3.669 | -0.134 | -2.924 | 14.831 | -2.597 | -1.118 |

| 5371378 | 1.498 | -2.624 | -3.288 | 616.461 | -0.663 | -0.203 |

| 5365831 | 3.064 | -3.204 | -3.505 | 2039.601 | -0.423 | 0.16 |

| 613040 | 2.792 | -2.976 | -4.833 | 7591.505 | 0.456 | 0.032 |

| 5283469 | 4.962 | -6.328 | -5.989 | 432.399 | -2.346 | 0.592 |

| 613101 | 3.502 | -3.651 | -4.121 | 1252.582 | -0.58 | 0.386 |

| 14900 | 4.49 | -5.732 | -5.73 | 482.566 | -2.264 | 0.395 |

| 616267 | 1.333 | -2.501 | -5.188 | 274.904 | -0.163 | -0.114 |

| 70627 | -0.338 | -0.521 | -2.907 | 364.597 | -0.708 | -0.751 |

| 587240 | 0.408 | -0.964 | -3.47 | 554.264 | -0.668 | -0.674 |

| 12444418 | 8.298 | -9.538 | -5.928 | 3005.087 | -0.863 | 2.111 |

| 5376281 | 3.97 | -4.431 | -3.72 | 4731.596 | 0.087 | 0.557 |

| 597057 | 6.096 | -7.351 | -5.642 | 424.508 | -2.342 | 0.98 |

| 1057 | 0.093 | -0.323 | -3.225 | 387.014 | -0.738 | -0.812 |

| 13387 | -0.362 | 1.015 | -1.15 | 1412.992 | 0.14 | -1.228 |

QPlog Po/w: Predicted octanol/water partition coefficient, QPlogS: Predicted aqueous solubility, QPlog HERG: Predicted IC50 value for blockage of HERG Kþ channels, QPP Caco: Predicted apparent Caco-2 cell permeability, QP logBB: Predicted brain/blood partition coefficient, QPlogKhsa: Prediction of binding to human serum albumin

IFD analysis

Top five compounds for each protein have been chosen for IFD depending on their interactions with the protein targets docking score. After IFD, the compound 5375797 has been chosen for MD simulation studies for the proteins 5GTR and 2ZOQ, as this compound has shown highest negative IFD score and also retained bonds. The compounds 613040 and 613101 are selected for MD analysis for 4BQG and 6VHN, respectively based on their IFD scores and bond retention. For the protein target 6NJS, MD analysis was not carried out as the compounds did not retain bonds during IFD analysis. The 3D interaction image of the compounds seleced for MD simulation studies are displayed in fig. 5.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation study results

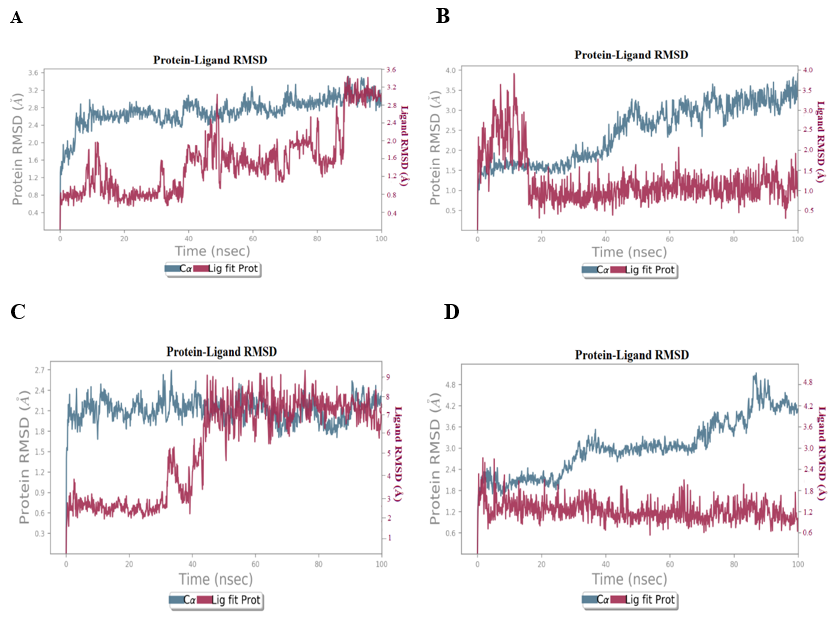

The primary goal of MD studies is to subject the receptor-ligand complex to physiologic settings that were not possible with ligand docking or IFD. Four protein-compound complexes (5375795-5GTR complex, 613040-4BQG complex, 5375797-2ZOQ complex, 613101-6VHN complex) were subjected to MD studies. During MDS, a trajectory frame was generated every 100 ps. 1000 frames were generated when MDS was performed for 100 ns. Analysis of “Root mean square deviation (RMSD),” and “Root mean square fluctuation (RMSF)” was also carried out. By aligning generated frames of protein and ligand-protein complex with the reference frame, the RMSD was computed. The plot of RMSD of proteins on the Y-axis indicates that the variations in protein RMSD are in the range of 1-3Å, which is widely acknowledged as a measure of protein stability during the simulation [39]. For complex 5375797-5GTR, some modest and considerable deviations were seen at about 40-45 ns, and the complex remained stable after 90 ns and no significant conformational change was seen (fig. 6A). In 613040-4BQG complex, significant deviations were observed till 20ns, following that, it remained stable throughout the simulation run, with no significant conformational changes seen (fig. 6B). The complex 5375797-2ZOQ exhibited an initial deviation at around 30–45 ns, following that, it remained stable throughout the simulation run, with no significant conformational changes (fig. 6C). The complex 613101-6VHN remains stable throughout the simulation run (fig. 6D).

Fig. 5: IFD 3D interaction diagram (A) 5375797-5GTR (IFD score:-487.09), (B) 613040-4BQG (IFD score:-450.20), (C) 5375797-2ZOQ (IFD score:-737.56), (D) 613101-6VHN (-587.54)

Fig. 6: RMSD Plots (A) 5375797-5GTR complex, (B) 613040-4BQG complex, (C) 5375797-2ZOQ complex, (D) 613101-6VHN complex

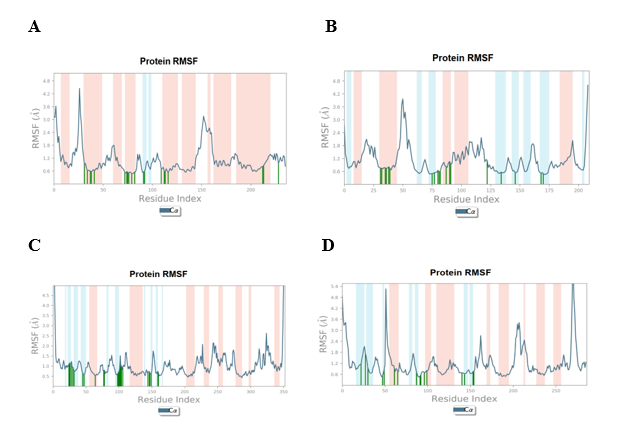

RMSF determines the residues responsible for fluctuations in the complexes and illustrates localized variations throughout the protein chain. The RMSF of the protein in relation to all ligands was shown in fig. 7A, 7B, 7C, and 7D. Our analysis revealed that all the four protein-ligand complexes (5375797-5GTR complex, 613040-4BQG complex, 5375797-2ZOQ complex, 613101-6VHN complex) exhibit several regions of significant flexibility, as shown by the peaks in their RMSF profiles. The RMSF values of the interacting residues, represented by green lines, in all the complexes, are below 1.8 Å. This suggests that the interactions formed between the ligands and the proteins are stable.

Fig. 7: RMSF Plots (A) 5375797-5GTR complex, (B) 613040-4BQG complex, (C) 5375797-2ZOQ complex, (D) 613101-6VHN complex

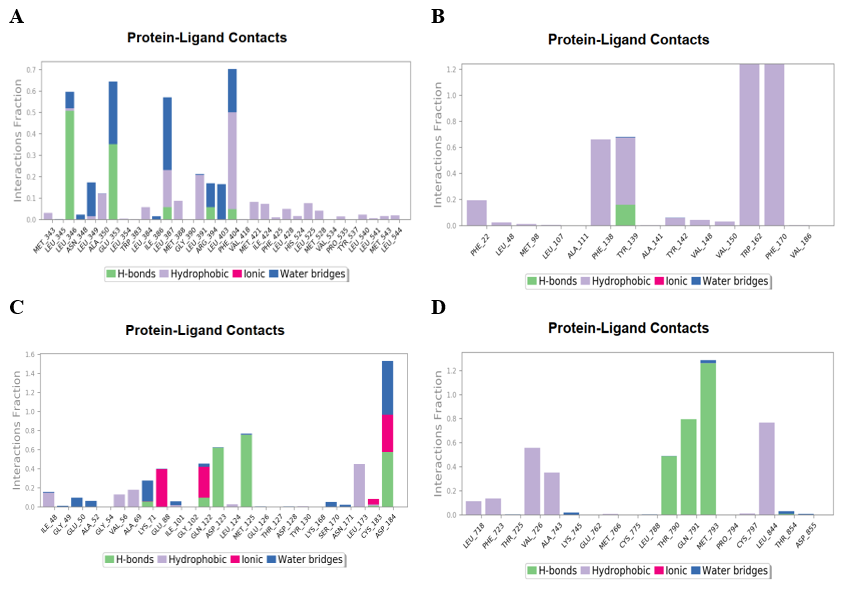

The protein-ligand contact pertains to the length of time during which the protein and the ligand interact during MD simulation run. A value of 0.4 signifies that the contact persisted for 40% of the total duration of the simulation, but value higher than 1 implies that there may be more interactions between the ligand and the protein's amino acid residue. The compound 5375797 demonstrated H-bond interactions with LEU349 and GLU 353 of 5GTR protein, which persisted for 60% and 65% of the simulation run, respectively. The compound 5375797 also formed a pi-pi interaction with PHE 404 residue of 5GTR protein, which lasted for 70% of the simulation run (fig. 8A). Several sustained interactions occurred between compound 613040 and residues TRP 162 and PHE 170 of 4BQG throughout the experiment. Pi interactions were also established between compound 613040 and PHE 138 and TYR 139 of 4BQG for a duration of 65% (fig. 8B). The compound 5375797 shared H-bond interactions with ASP123 and MET125 of 2ZOQ and these interactions lasted for 40% of simulation run. The compound 5375797 had multiple interactions with the residues ASP 184 of 2ZOQ that lasted throughout the experiment (fig. 8C). The compound 613101 formed hydrogen bonds with the key amino acid residues THR 790 and MET 793. These interactions were present for 50% and 100% of the entire simulation duration, respectively (fig. 8D).

Fig. 8: Histogram of Protein-ligand complex (A) 5375797-5GTR complex, (B) 613040-4BQG complex, (C) 5375797-2ZOQ complex, (D) 613101-6VHN complex

DISCUSSION

Network pharmacology research focuses on the identification of genes associated to compounds and diseases, the building of a PPI network, and the subsequent analysis and visualization of the network [40, 41]. Constructing molecular networks from extensive databases is a straightforward beginning. Subsequently, by employing network analysis, crucial nodes are determined, and essential biological pathways are forecasted [42, 43]. In the current research, we examined the possible molecular mechanisms of the active constituents present in S. caryophyllatum leaf extract responsible for its anticancer activity by integrating the network pharmacology and computational approach. In vitro cytotoxic assay conducted on the extract revealed that it has shown significant cytotoxic activity against HT 29 cell lines and subsequent GC-MS analysis indicated that the extract contained 76 compounds. The network analysis identified 528 targets of 76 compounds, and a total of 1131 gene targets linked to colon cancer were extracted from the Gene cards database. The Cytoscape software was utilized to identify the five most important hub targets selected based on the degree of interaction, closeness centrality and betweenness centrality and the targets include ESR1, HSP90AA1, MAP3K, EGFR and STAT3. ESR1 is involved in the signalling cascade associated with NOD-like receptors (NLR) in cancer. By inhibiting NLRP3 expression and inflammasome activity, a selective ER antagonist might drastically reduce pro-inflammatory cytokine expression, inhibit cell proliferation, and promote apoptosis [44, 45]. The MAPK pathway is a key target for developing colon cancer therapies. Abnormal MAPK pathway activation in colon cancer can lead to uncontrolled proliferation, resistance to therapy, and the spread of cancer cells to other tissues and organs [46, 47]. According to several studies, MAPK3 overexpression has been linked to the beginning, development and metastasis of several carcinomas, including colon cancer [48]. The HSP90, encoded by HSP90AA1 gene is overexpressed in a number of malignancies, including CRC, and promotes neoplastic transformation by preventing cancer cell invasiveness [49, 50]. Since the discovery of the first Hsp 90 inhibitors, natural compounds have shown enormous potential as a source for creating new inhibitors for Hsp90. As a result, several innovative natural and semi-synthetic HSP90 inhibitors have been developed and are currently being tested in clinical studies [51, 52]. In colitis-associated cancer (CRC), STAT3 over-activates and promotes tumour development, angiogenesis, cancer cell invasion, and migration [53–55].

Our study utilized the KEGG and GO functional enrichment analysis to examine 135 targets. The analysis revealed that the genes are involved in various signalling pathways such as EGFR, PD-L1 expression, Fc epsilon RI, ErbB, HIF-1 and VEGF, which had a role in the development of colon cancers [56]. This suggests that the phytocompounds present in S. caryophyllatum plant have a multi-faceted impact on many pathways involved in the genesis of colon cancer.

Furthermore, using the Schrodinger suite Version 11.4 software, an in silico docking analysis of the 76 compounds with the target proteins (ESR1, HSP90AA1, MAP3K, EGFR and STAT3) was done to validate the findings of network pharmacology. Further, the results of molecular docking confirmed the presence of a high binding energy between the selected compounds and the prospective targets. Based on their interactions with the protein targets, docking score, ADME characteristics, IFD score and bond retention, a single compound has been selected for each target protein for simulation studies. The compound 5,7-Dihydroxy-2-undecyl-4H-chromen-4-one (CID: 5375797) was selected for MD simulation research for the proteins 2ZOQ and 5GTR. Based on their IFD scores and bond retention, the compounds 7a,12-Dihydroindolo[2,3-a]quinolizine (CID: 613040) and 5-hydroxy-7-methoxy-2-methyl-8-(3-methylbutyl)chromen-4-one (CID: 613101) are chosen for MD analysis for 4BQG and 6VHN, respectively. The compound 5,7-Dihydroxy-2-undecyl-4H-chromen-4-one (CID: 5375797). The ADME predicted by the QikProp tool indicates that the three compounds (CID: 5375797, CID: 613040 and CID: 613101) adhere to Lipinski's rule of five in terms of druggability, transport properties, and pharmacokinetics. The two compounds 5,7-Dihydroxy-2-undecyl-4H-chromen-4-one and 5-hydroxy-7-methoxy-2-methyl-8-(3-methylbutyl) chromen-4-one are chromone derivatives. Chromones are a type of heterocyclic compounds that include oxygen. Previous research findings show that the chromone derivatives exhibit anticancer activity through a varied array of pathways, including anti-metastasis, cytotoxicity, chemoprevention, anti-angiogenesis, and immune modulation properties [57, 58]. Therefore, to create novel approaches for cancer prevention and treatment, more investigation is necessary to pinpoint the precise molecular pathways underlying the anticancer activity of the bioactive compounds studied in this work.

This study was based on the application of a network pharmacology approach to explore the possible anticancer compounds discovered in the plant S. caryophyllatum, an area that had previously been unexplored. Regrettably, the inaccessibility of the compounds for commercial utilization rendered comprehensive in vitro and in vivo analysis impracticable for our research.

CONCLUSION

The present investigation employed the network pharmacology approach to analyse possible molecular mechanisms of 76 active compounds present in the S. caryophyllatum plant leaf extract and the analysis has identified five significant hub target proteins, namely, ESR1, HSP90AA1, MAP3K, EGFR and STAT3. Further Molecular docking studies revealed that the compound 5,7-Dihydroxy-2-undecyl-4H-chromen-4-one docked favourably with the MAPK3 and ESR-1 proteins, the compound 7a,12-Dihydroindolo[2,3-a] quinolizine docked effectively with HSP90AA1 protein, and the compound 5-hydroxy-7-methoxy-2-methyl-8-(3-methylbutyl)chromen-4-one docked with EGFR protein active site. Thus, these findings indicate that the three identified compounds may have a significant role in mitigating colon cancer by affecting the key protein targets that are involved in colon carcinogenesis. Therefore, network pharmacology and computational investigations provide a diverse array of applications and hold immense potential as a strategy for future drug development aimed at reducing the occurrence of colon cancer. Nevertheless, it is crucial to note that further clinical and pharmacological investigation is necessary to substantiate the findings of this study.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

All authors express gratitude to Manipal College of Pharmaceutical Sciences (MCOPS) and Manipal Academy of Higher Education (MAHE) for their provision of facilities for this research. The authors express their gratitude to the Manipal-Schrödinger Centre for Molecular Simulations. Ms. Ramadevi Pemmereddy acknowledges the Manipal Academy of Higher Education (MAHE) for providing Dr. T. M. A. Pai Doctoral Fellowship. Mr. Jyothi Giridhar acknowledges the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), Government of India, for providing the Junior Research Fellowship.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: Ramadevi Pemmereddy and Chandrashekar K. S; Methodology: Ramadevi Pemmereddy and Ajay Mili; Software: Ramadevi Pemmereddy, Bharath Harohalli Byregowda, Jyothi Giridhar and Ajay Mili; Formal analysis: Ramadevi Pemmereddy, Chandrashekar K. S and Sreedhara Ranganath Pai K; Data curation: Ramadevi Pemmereddy, Anna Mathew and Vasudev Pai; Writing-original draft preparation: Ramadevi Pemmereddy and Chandrashekar K. S; Writing, review and editing: Ramadevi Pemmereddy, Ajay Mili, Bharath Harohalli Byregowda and Jyothi Giridhar. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors confirm that they do not have any competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have impacted the work provided in this study.

REFERENCES

World Health Organization. World health statistics 2023: monitoring health for the SDGS sustainable development goals. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240074323. [Last accessed on 10 Dec 2023].

Kumar A, Gautam V, Sandhu A, Rawat K, Sharma A, Saha L. Current and emerging therapeutic approaches for colorectal cancer: a comprehensive review. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2023 Apr 4;15(4):495-519. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v15.i4.495, PMID 37206081.

Negarandeh R, Salehifar E, Saghafi F, Jalali H, Janbabaei G, Abdhaghighi MJ. Evaluation of adverse effects of chemotherapy regimens of 5-fluoropyrimidines derivatives and their association with DPYD polymorphisms in colorectal cancer patients. BMC Cancer. 2020 Dec;20(1):560. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-06904-3, PMID 32546132.

Wang M, Liu X, Chen T, Cheng X, Xiao H, Meng X. Inhibition and potential treatment of colorectal cancer by natural compounds via various signaling pathways. Front Oncol. 2022 Sep 8;12:956793. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.956793, PMID 36158694.

Atanasov AG, Zotchev SB, Dirsch VM, International Natural Product Sciences Taskforce, Supuran CT. Natural products in drug discovery: advances and opportunities. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2021 Mar;20(3):200-16. doi: 10.1038/s41573-020-00114-z, PMID 33510482.

Dias DA, Urban S, Roessner U. A historical overview of natural products in drug discovery. Metabolites. 2012 Apr 16;2(2):303-36. doi: 10.3390/metabo2020303, PMID 24957513.

Shaikh AM, Shrivastava B, Apte KG, Navale SD. Medicinal plants as potential source of anticancer agents: a review. J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2016;5(2):291-5.

Ediriweera ER, Ratnasooriya WD. A review on herbs used in treatment of diabetes mellitus by Sri Lankan ayurvedic and traditional physicians. Ayu. 2009 Oct 1;30(4):373-91.

Shilpa KJ, Krishnakumar G. Nutritional fermentation and pharmacological studies of Syzygium caryophyllatum (L.) Alston and Syzygium zeylanicum (L.) DC fruits. Cogent Food Agric. 2015 Dec 31;1(1):1018694. doi: 10.1080/23311932.2015.1018694.

NS, P SS. Screening of phytochemical and pharmacological activities of Syzygium caryophyllatum (L.) Alston. Clin Phytosci. 2018 Dec 1;4(1). doi: 10.1186/s40816-017-0059-2.

Rabeque CS, Padmavathy S. Hypoglycaemic effect of Syzygium caryophyllatum (L.) Alston on alloxan-induced diabetic albino mice. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2013;6(4):203-5.

Raj R, Chandrashekar KS, Pai V. In vitro anticancer activity of Syzygium caryophyllatum L. on hela cell lines using MTT assay. Lat Am J Pharmacol. 2018 Jan 1;37(5):1046-8.

Patwardhan B, Chandran U. Network ethnopharmacology approaches for formulation discovery. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2015;14:574-80.

Zhao L, Zhang H, LI N, Chen J, XU H, Wang Y. Network pharmacology a promising approach to reveal the pharmacology mechanism of Chinese medicine formula. J Ethnopharmacol. 2023 Jun 12;309:116306. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2023.116306, PMID 36858276.

Orellana EA, Kasinski AL. Sulforhodamine B (SRB) assay in cell culture to investigate cell proliferation. Bio Protoc. 2016 Nov 5;6(21):e1984. doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.1984, PMID 28573164.

Houghton P, Fang R, Techatanawat I, Steventon G, Hylands PJ, Lee CC. The sulphorhodamine (SRB) assay and other approaches to testing plant extracts and derived compounds for activities related to reputed anticancer activity. Methods. 2007 Aug 1;42(4):377-87. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.01.003, PMID 17560325.

Omoboyede V, Onile OS, Oyeyemi BF, Aruleba RT, Fadahunsi AI, Oke GA. Unravelling the anti-inflammatory mechanism of Allium cepa: an integration of network pharmacology and molecular docking approaches. Mol Divers. 2024 Apr;28(2):727-47. doi: 10.1007/s11030-023-10614-w, PMID 36867320.

YU JW, Yuan HW, Bao LD, SI LG. Interaction between piperine and genes associated with sciatica and its mechanism based on molecular docking technology and network pharmacology. Mol Divers. 2021 Feb;25(1):233-48. doi: 10.1007/s11030-020-10055-9, PMID 32130644.

Mutiah R, Rachmawati E, Zahiro SR, Milliana A. Elucidating the active compound profile and mechanisms of Dendrophthoe pentandra on colorectal cancer: LCMS/MS identification and network pharmacology analysis. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2024 Feb 5;14(2):222-31. doi: 10.7324/JAPS.2024.152900.

Sachdeo R, Khanwelkar C, Shete A. In silico exploration of berberine as a potential wound healing agent via network pharmacology molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation. Int J App Pharm. 2024;16(2):188-94. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2024v16i2.49922.

Tan S, Yulandi A, Tjandrawinata RR. Network pharmacology study of Phyllanthus niruri: potential target proteins and their hepatoprotective activities. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2023 Dec 5;13(12):232-42. doi: 10.7324/JAPS.2023.146937.

Gadewar MA, Lal BH. Molecular docking and screening of drugs for 6lu7 protease inhibitor as a potential target for COVID-19. Int J App Pharm. 2022;14(1):100-5. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2022v14i1.43132.

Nurhasanah NE, Fadilah FA, Bahtiar AN. Prediction of active compounds of Muntingia calabura as potential treatment for chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases by network pharmacology integrated with molecular docking. Int J App Pharm. 2023 Jan 1;15(1):274-9. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2023v15i1.46281.

Mili A, Birangal S, Nandakumar K, Lobo R. A computational study to identify sesamol derivatives as NRF2 activator for protection against drug-induced liver injury (DILI). Mol Divers. 2024 Jun;28(3):1709-31. doi: 10.1007/s11030-023-10686-8, PMID 37392347.

Mehta SI, Pathak SR. In silico drug design and molecular docking studies of novel coumarin derivatives as anticancer agents. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2017;10(4):335-40. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2017.v10i4.16826.

Sahayarayan JJ, Rajan KS, Vidhyavathi R, Nachiappan M, Prabhu D, Alfarraj S. In silico protein-ligand docking studies against the estrogen protein of breast cancer using pharmacophore-based virtual screening approaches. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2021 Jan 1;28(1):400-7. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.10.023, PMID 33424323.

Suresh AJ, Devi R, Noorulla KM, Surya PR. Insights into thioridazine for its antitubercular activity from molecular docking studies. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2015;7(3):344-6.

Bhat NB, Das S, Sridevi BV, H RC, Nayaka S, SN. Molecular docking and dynamics supported investigation of antiviral activity of lichen metabolites of roccella montagnei: an in silico and in vitro study. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2023 Dec 29;41(21):11484-97. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2023.2180666, PMID 36803674.

Vanajothi R, Hemamalini V, Jeyakanthan J, Premkumar K. Ligand based pharmacophore mapping and virtual screening for identification of potential discoidin domain receptor 1 inhibitors. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2020 Jun 12;38(9):2800-8. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2019.1640132, PMID 31269869.

Kumar S, Sharma PP, Shankar U, Kumar D, Joshi SK, Pena L. Discovery of new hydroxyethylamine analogs against 3CLpro protein target of SARS-CoV-2: molecular docking molecular dynamics simulation and structure-activity relationship studies. J Chem Inf Model. 2020 Jun 2;60(12):5754-70. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.0c00326, PMID 32551639.

Mahgoub MA, Alnaem A, Fadlelmola M, Abo Idris M, Makki AA, Abdelgadir AA. Discovery of novel potential inhibitors of TMPRSS2 and Mpro of SARS‐CoV‐2 using E-pharmacophore and docking-based virtual screening combined with molecular dynamic and quantum mechanics. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2023 Sep 22;41(14):6775-88. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2022.2112080, PMID 35997154.

Gao Y, Nan Z. Mechanistic insights into the use of rhubarb in diabetic kidney disease treatment using network pharmacology. Medicine. 2022 Jan 7;101(1):e28465. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000028465, PMID 35029893.

Pang X, FU W, Wang J, Kang D, XU L, Zhao Y. Identification of estrogen receptor α antagonists from natural products via in vitro and in silico approaches. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2018;2018(1):6040149. doi: 10.1155/2018/6040149, PMID 29861831.

Brasca MG, Mantegani S, Amboldi N, Bindi S, Caronni D, Casale E. Discovery of NMS-E973 as novel selective and potent inhibitor of heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90). Bioorg Med Chem. 2013 Nov 15;21(22):7047-63. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.09.018, PMID 24100158.

Kinoshita T, Yoshida I, Nakae S, Okita K, Gouda M, Matsubara M. Crystal structure of human mono phosphorylated ERK1 at Tyr204. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008 Dec 26;377(4):1123-7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.10.127, PMID 18983981.

Heppner DE, Gunther M, Wittlinger F, Laufer SA, Eck MJ. Structural basis for EGFR mutant inhibition by trisubstituted imidazole inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2020 Apr 3;63(8):4293-305. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00200, PMID 32243152.

Heppner DE, Wittlinger F, Beyett TS, Shaurova T, Urul DA, Buckley B. Structural basis for inhibition of mutant EGFR with lazertinib (YH25448). ACS Med Chem Lett. 2022 Nov 10;13(12):1856-63. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.2c00213, PMID 36518696.

Bai L, Zhou H, XU R, Zhao Y, Chinnaswamy K, Mc Eachern D. A potent and selective small molecule degrader of STAT3 achieves complete tumor regression in vivo. Cancer Cell. 2019 Nov 11;36(5):498-511.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2019.10.002, PMID 31715132.

Patel R, Kumar A, Lokhande KB, Swamy KV, Sharma NK. Molecular docking and simulation studies predict lactyl-CoA as the substrate for P300-directed lactylation; 2020.

Zhang Y, Yuan T, LI Y, WU N, Dai X. Network pharmacology analysis of the mechanisms of compound herba sarcandrae (Fufang Zhongjiefeng) aerosol in chronic pharyngitis treatment. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2021 Jun 28;15:2783-803. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S304708, PMID 34234411.

Adrian MF, Lubis MF, Syahputra RA, Astyka R, Sumaiyah S, Yudha Harahap MA. The potential effect of aporphine alkaloids from Nelumbo nucifera gaertn. As anti-breast cancer based on network pharmacology and molecular docking. Int J App Pharm. 2024;16(1):280-7. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2024v16i1.49171.

Sachdeo R, khanwelkar C, Shete A. In silico exploration of berberine as a potential wound healing agent via network pharmacology molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation. Int J App Pharm. 2024;16(2):188-94. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2024v16i2.49922.

LI L, Yang L, Yang L, HE C, HE Y, Chen L. Network pharmacology: a bright guiding light on the way to explore the personalized precise medication of traditional Chinese medicine. Chin Med. 2023 Nov 8;18(1):146. doi: 10.1186/s13020-023-00853-2, PMID 37941061.

Sakle NS, More SA, Mokale SN. A network pharmacology-based approach to explore potential targets of Caesalpinia pulcherima: an updated prototype in drug discovery. Sci Rep. 2020 Oct 14;10(1):17217. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-74251-1, PMID 33057155.

Fan W, Gao X, Ding C, LV Y, Shen T, MA G. Estrogen receptors participate in carcinogenesis signaling pathways by directly regulating NOD-like receptors. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019 Apr 2;511(2):468-75. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.02.085, PMID 30797557.

Das PK, Saha J, Pillai S, Lam AK, Gopalan V, Islam F. Implications of estrogen and its receptors in colorectal carcinoma. Cancer Med. 2023 Feb;12(4):4367-79. doi: 10.1002/cam4.5242, PMID 36207986.

Urosevic J, Nebreda AR, Gomis RR. MAPK signaling control of colon cancer metastasis. Cell Cycle. 2014 Sep 2;13(17):2641-2. doi: 10.4161/15384101.2014.946374, PMID 25486343.

Slattery ML, Lundgreen A, Wolff RK. MAP kinase genes and colon and rectal cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2012 Dec 1;33(12):2398-408. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs305, PMID 23027623.

Baba Y, Nosho K, Shima K, Meyerhardt JA, Chan AT, Engelman JA. Prognostic significance of AMP-activated protein kinase expression and modifying effect of MAPK3/1 in colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2010 Sep;103(7):1025-33. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605846, PMID 20808308.

Szczuka I, Wierzbicki J, Serek P, Szczesniak Siega BM, Krzystek Korpacka M. Heat shock proteins HSPA1 and HSP90AA1 are upregulated in colorectal polyps and can be targeted in cancer cells by anti-inflammatory oxicams with arylpiperazine pharmacophore and benzoyl moiety substitutions at thiazine ring. Biomolecules. 2021 Oct 27;11(11):1588. doi: 10.3390/biom11111588, PMID 34827586.

Lacey T, Lacey H. Linking hsp90’s role as an evolutionary capacitator to the development of cancer. Cancer Treat Res Commun. 2021 Jan 1;28:100400. doi: 10.1016/j.ctarc.2021.100400, PMID 34023771.

Mitra S, Dash R, Munni YA, Selsi NJ, Akter N, Uddin MN. Natural products targeting Hsp90 for a concurrent strategy in glioblastoma and neurodegeneration. Metabolites. 2022 Nov 21;12(11):1153. doi: 10.3390/metabo12111153, PMID 36422293.

Gargalionis AN, Papavassiliou KA, Papavassiliou AG. Targeting STAT3 signaling pathway in colorectal cancer. Biomedicines. 2021 Aug 15;9(8):1016. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9081016, PMID 34440220.

Wei N, LI J, Fang C, Chang J, Xirou V, Syrigos NK. Targeting colon cancer with the novel STAT3 inhibitor bruceantinol. Oncogene. 2019 Mar 7;38(10):1676-87. doi: 10.1038/s41388-018-0547-y, PMID 30348989.

Lin HC, HO AS, Huang HH, Yang BL, Shih BB, Lin HC. STAT3 mediated gene expression in colorectal cancer cells derived cancer stem-like tumorspheres. Adv in Digestive Medicine. 2021 Dec;8(4):224-33. doi: 10.1002/aid2.13223.

Wan ML, Wang Y, Zeng Z, Deng B, Zhu BS, Cao T. Colorectal cancer (CRC) as a multifactorial disease and its causal correlations with multiple signaling pathways. Biosci Rep. 2020 Mar;40(3). doi: 10.1042/BSR20200265, PMID 32149326.

Duan YD, Jiang YY, Guo FX, Chen LX, XU LL, Zhang W. The antitumor activity of naturally occurring chromones: a review. Fitoterapia. 2019;135:114-29. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2019.04.012, PMID 31029639.

Maicheen C, Phosrithong N, Ungwitayatorn J. Docking study on anticancer activity of chromone derivatives. Med Chem Res. 2013 Jan;22(1):45-56. doi: 10.1007/s00044-012-0009-y.