Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 2, 2025, 53-64Review Article

AN OVERVIEW OF NANO-CRYSTALLINE CELLULOSE NANOFIBERS AND THEIR APPLICATIONS IN DRUG DELIVERY

NAWZAT D. ALJBOURa*, ENAS A. ALKHADERa, MOHAMMAD D. BEGb

aFaculty of Pharmacy, Middle East University, Amman, Jordan. bSchool of Engineering, University of Waikato, Private Bag 3105, Hamilton-3240, New Zealand

*Corresponding author: Nawzat D. Aljbour; *Email: naljbour@meu.edu.jo

Received: 18 Aug 2024, Revised and Accepted: 15 Jan 2025

ABSTRACT

Made from a variety of natural sources, Nano Crystalline Cellulose (NCC) is a unique renewable nanomaterial with a wide range of applications due to its high stiffness and strength, low weight, biodegradability, and environmental benefits. Because of its special inherent qualities, NCC is one of the most renewable materials to be addressed by nanomaterials. The origins, manufacture, characteristics, and applications of nanomaterials, including NCC and nanofibers, have been extensively studied by a large number of researchers throughout the years. Strong chemical reactivity, crystallinity, strength and stiffness, biocompatibility, biodegradability, shape, and nanoscale dimensions are just a few of the remarkable properties that these nanomaterials have been shown to possess in countless investigations. These characteristics enable the application of these nanoparticles in a number of fields, including medicine. Among the most traditional and popular techniques. Electrospinning is one of the earliest and most popular techniques for producing nanofibers. This method works well and can be modified to produce continuous nanofibers. NCC-based nanofibers are novel materials in the biomaterials industry. Recent studies demonstrated that electrospun nanofibers could be efficiently loaded with a wide range of drugs, such as proteins, chemotherapeutic agents, antibiotics, and analgesics with anti-inflammatory qualities. One application of NCC and nanofibers in the medical field is drug delivery. This review highlights a number of issues related to NCC nanofibers and their use in drug delivery applications, beginning with discussing the various natural polymer types used in drug delivery applications, the physicochemical and biological properties of NCC, its various applications, its significance, and its preparation techniques.

Keywords: Nanofibers, Nanocrystalline cellulose, Drug delivery applications, Electrospinning process

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i2.52561 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

A great deal of research interest has been placed on the application of nanocrystalline cellulose-based materials in medical procedures like dressing of wound, drug delivery, medical implants as well as framework for tissue engineering and vascular grafts in recent years [1]. The rising environmental awareness in recent years has further sparked a high request for materials that are environment-friendly with terms like ‘biodegradable’, ‘renewable’, ‘recyclable’, ‘biodegradable’, ‘sustainable’, etc., to achieve the desired design and structural requirements [2]. The most essential structural element found in the cell wall of plants is cellulose and in general, the mechanical characteristics of naturally occurring fibers depend on it [3]. Natural fibers give materials that contain them certain advantages over conventional engineering fibers like carbon and glass fibers as well as mineral fibers, including low density, which is approximately 1.4 g cc−1 when compared to the density of E-glass, which is approximately 2.5 g cc−1, parallel specific moduli and strength to the glass fibers, as well as high flexibility property [4]. Natural fibers have their pros and cons; notwithstanding, greater natural fibers loading in materials that bear them is possible compared to the traditional inorganic fillers because of the softer, nonabrasive nature of natural fibers [5]. Molecular chains of cellulose are generally arranged in an organized manner to create a consolidated microfibrils that are made stable by intramolecular and intermolecular hydrogen bonds [6]. Cellulose molecular chains are bio-synthesized and auto-assembled to form micro fibrils with amorphous regions alternating with crystalline regions [7]. In terms of size, cellulose micro fibrils range from 10–30 nm in diameter and they consist of thirty to one hundred molecules of cellulose in long chains conformation and gives the fiber strength mechanically [8]. The three alcoholic hydroxyl groups account for the hydrophobic nature of cellulose macromolecules [9].

As a result, an unbounded-OH group, which is present mainly in the noncrystalline or amorphous area of cellulose, performs a key function in their pattern of reaction in the course of hydrolysis; the cellulose crystalline part however remains integral. Since one of the properties of medical biocomposites is biocompatibility or the ability to properly function in the body of human beings to give expected medical outcomes without causing side effects, cellulose Nanocrystals as biomaterials can be promising biomaterials [10].

Search criteria

Based on specified keywords, a systematic literature search for all relevant studies up to 2024 in Google Scholar (https://scholar.google.com), Pub Med (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), ResearchGate (https://www.researchgate.net) and Web of Science (http://www.webofknowledge.com). Text words and phrase words were utilized. Nanofibers was one of the major keywords used, nanocrystal line cellulose, electrospinning process, and finally, nanofibers in different drug delivery applications.

Natural polymers in drug delivery

Increased research interest has been devoted toward advanced drug delivery technologies in recent decades, owing to their superior attributes in comparison to conventional drug delivery systems [11]. These advantages encompass controlled drug release, the ability to sustain therapeutic drug concentrations throughout the treatment duration, targeted drug delivery, enhanced pharmacokinetics, reduced side effects, improved patient adherence, prolonged drug half-lives, and various other benefits [11].

Among these advanced drug delivery technologies, micro and nanocarriers, liposomes have gained immense interest, particularly polymeric-based advanced Drug Delivery Systems (DDS) [12, 13]. Synthetic and natural polymers have garnered high interest due to their bio-adhesive properties, biodegradability, biocompatibility-controlled release properties, and low toxicity [14].

Chitosan

Chitosan is a widely used polymer derived from the shells of marine organisms such, including lobsters and crab shells, as well as insects, fungi, and yeast [15]. The process of N-deacetylation of chitin produces chitosan, a polysaccharide characterized by the presence of 2-deoxy-2-(acetylamino) glucose units connected through 1,4-glycosidic linkages [16, 17].

Chitosan have elicited considerable interest due to its biocompatibility, biodegradability, non-toxicity, nan-carcinogenicity, antibacterial properties, unique behavior due to its positive charge, high encapsulation properties, good mechanical strength, high cellular uptake, absorption enhancing and mucoadhesive properties [18]. In addition, chitosan’s structure resembles the biologically occurring glycosaminoglycans, degraded by biological enzymes, and supports haemostasis [19].

Chitosan has been employed in the drug delivery in various contexts such as micro and nanocarriers as well as in the formulation of coating materials [20, 21]. Recent investigations have revealed diverse innovations and uses of chitosan in the domain of drug delivery. Chitosan has been employed in bio-printing in tissue engineering and drug delivery applications as chitosan-based inks for 3D/four-dimensional (4D) (bio) printing [22]. In addition, Chitosan has been employed in nucleic acid delivery owing to its capacity to form complexes with nucleotides through electrostatic interactions with the phosphoric groups of DNA/RNA [23]. Crossing the blood-brain barrier is considered one of the major challenges in delivering drugs to the brain. Clonazepam was carried in chitosan-coated niosomes (chitosomes) [24], vinpocetine carried in chitosan containing nanoparticles [25], and protein-loaded chitosan nanoparticles were fabricated [26] for nose to brain delivery of the drugs. Chitosan has been immensely used for oral colon-specific delivery of several medications including irinotecan and quercetin [27], paclitaxel [28], and 5-fluorouracil [29].

Alginate

Alginates comprise a category of unbranched, water-soluble polysaccharide anionic polymers derived from brown seaweeds, algae, and soil bacteria [30]. The structure of alginates includes a linear biopolymer of two uronic acids, namely, αguluronic acid (G) and 1,4-linked-β-D-mannuronic acid (M) [31]. The chemical characteristics of alginate, including its solubility and hydrophobicity, render it an appropriate polymer for chemical functionalization [32].

Alginate’s derivatives have gained increased interest in drug delivery as well due to their high mechanical strength, permeability, low toxicity, biocompatibility, high affinity with drugs, among others [33]. In addition, alginates have unique properties of gel forming which aids in its use in targeted drug delivery [34], suitable for sustained drug release, and have the ability to stabilize formulations [35].

In vivo pharmacokinetics of alginate nanoparticles were investigated for the delivery of anti-tuberculosis drugs [36, 37]. Alginate-based formulations designed for pulmonary delivery were scrutinized for the delivery of d-cycloserine [38], paclitaxel [39], rofulmilast [40], ropinirole [41], and budesonide [42]. Alginate nanoparticles were examined for the delivery of antifungal drugs delivery [43].

Albumin

Albumin, a water-soluble globular protein, comprises three primary domains and two binding sites [44]. Almost 50% of the total plasma mass of the body is comprised of albumin, which holds maintains the blood pH and holds fatty acids in the blood [45]. The blood compatibility of albumin attracted interest towards employing albumin in advanced drug delivery systems. Albumin is available in three forms including Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), Ovalbumin (OVA), and Human Serum Albumin (HAS) [46].

Albumin has attracted increased research interest because it is non-toxic, economical, stabilizes formulations, sensitive to pH or temperature changes, provides sustained drug release, biodegradable, has several reactive functional groups, and improves circulation profiles [47, 48].

Nanoparticles containing paclitaxel bound to albumin were examined for the treatment of metastatic breast cancer, showing reduced cytotoxicity [49, 50]. Albumin nanocarriers were investigated as a carrier of curcumin to increase its solubility [51]. Furthermore, albumin nanocarriers were examined for the delivery of many drugs, including berberine [52], docetaxel [53], palmitic acid [54], colistin [55], and arsenite [56].

Hyaluronic acid

Hyaluronic acid, conjointly termed as Hyaluronan, is a mucopolysaccharide composed of linearly repeated units of disaccharides of D-glucuronic acid and N-acetyl-D glucosamine linked by β-1,3 or β-1,4-glycosidic bonds [57]. Hyaluronic acid has carboxyl and hydroxyl functional groups in addition to its negative surface charge that help in its modification with hydrophobic macromolecules [58]. Hyaluronic acid is extracted from synovial fluids in the skin and vertebrate tissues of the body [59].

Hyaluronic acid has garnered heightened attention in research as it has high viscoelasticity, biodegradability, biocompatibility, mucoadhesion, ease of chemical modification, and ability to combine with several receptor ligands [60].

Hyaluronic acid can enhance the dermal transport of diverse molecules, particularly those with a high molecular weight that can be readily encapsulated in the pores. These systems aid in the regulated release of molecules, consequently mitigating dose-dependent toxicity and enhancing bioavailability [61]. Hyaluronic acid has been fabricated in advanced dermal drug delivery systems for the delivery of biomacromolecules [62], human growth hormones [63], sodium ascorbyl sulphates [64], and diclofenac [61]. Furthermore, the low viscosity of the ophthalmic preparations of hyaluronic acid and due to its bioadhesive properties, research has investigated the fabrication of hyaluronic-based ophthalmic preparations [65, 66]. Moreover, Hyaluronic acid has been utilized as a means for the nasal delivery of small molecular drugs to enhance their bioavailability and bioadhesion [67, 68].

Gelatin

Gelatin is a blend of protein and peptide materials found in two types; type A is obtained by acidic treatment, whereas type B is obtained by alkaline treatment of collagen extracted from the skin, bones, and connective tissues. Gelatin is characterized by the abundance of amino acids proline, glycine, and alanine which are responsible of the triple helical structure [69].

Gelatin was regarded as a compelling material for formulations in drug delivery due to its availability, non-toxicity, biocompatibility, biodegradability, inexpensiveness, low antigenicity, ease of chemical alteration, ability to bind to drugs, and lack of pyrogens [70-72].

Gelatin nanoparticles have been examined for the delivery of antibiotics, anti-inflammatory agents, antivirals, antifungals, among others [73]. pH-sensitive gelatin-based hydrogels were fabricated and examined for the delivery of riboflavin which showed non-cytotoxic and sustained release of the drug [74]. Moreover, the viscoelastic stress relaxation in colloidal hydrogels composed of gelatin nanoparticles were examined and demonstrated rapid stress relaxation within physiologically relevant strains of 10-50%, linked to cellular activity, potentially promoting the migration and proliferation of cells in colloidal hydrogels [75].

Pectin

Pectin is linear polysaccharide consists of α-1,4-linked D-galacturonic acid residues with 1,2-linked L-rhamnose residues. Its abundant of neutral sugars including galactose, rhamnose, arabinose, glucose, and xylose [76-78]. The pectin composition varies depending on the source, pectin can be obtained from apples and citrus fruits via acid hydrolysis of the inner portion of their peels [76].

Pectin has sparked growing research attention as a hydrophilic polymeric material due to its biocompatibility, biodegradability, availability, non-toxicity, and the fact that pectin itself has beneficial health benefits such as lipid and cholesterol-lowering activity, protecting against gastric ulcers, and apoptogenic effects in the malignant tumor cells [79].

Pectin has been extensively explored as a carrier for targeted delivery to the colon, liver, and topical and transdermal drug delivery [80, 81].

Carrageenan

Carrageenan is an anionic sulphated polysaccharide composed of alternate units of 3,6-anhydrogalactose and D-galactose joined by β-1,4 and α-1,3 glycosidic linkages [82]. “Carrageenan” is derived from the Irish word “carrageen” which means “little rock” as it’s obtained from red seaweed of Rhodophyceae family [83].

Carrageenan has seen a surge in interest as drug carrier due to its interesting characteristics including thickening, gelling, stabilizing, and emulsifying properties. In addition, it possesses a variety of therapeutic properties such as anticoagulant, antihyperlipidemic, anticancer, and immunomodulatory properties [84].

Biomedically, carrageenan has been employed in tissue engineering [85], wound healing, and drug delivery [86].

Cellulose and cellulose derivatives

Cellulose stands out as one of the most significant natural biopolymers due to their widespread occurrence in nature. Cellulose consists of repeating glucose units linked together via β-1,4 glycosidic linkages in an unbranched natural polymer structure [87]. Cellulose can be derived from various sources such as wood, plants, bacteria, algae, and tunicates, with wood and plants being the most commonly utilized [88].

Cellulose derivatives have been derived from cellulose via chemical functionalization and treatment, the purpose was to enhance the expanding flexibility of cellulose [89, 90]. Properties of cellulose derivatives depend on several factors, including the type and degree of substitution and the pattern of functionalization along the polymer chain [91].

Methyl cellulose is the simplest cellulose ethers synthesized by the addition of methylating agent in alkaline medium. Methyl cellulose can be used in gels formation; the characteristic of the gel depends on several factors, including molecular weight, the degree of cellulose substitution, and the concentrations of additives. In pharmaceutical formulations, methyl cellulose has been used as an emulsifying agent as well as its employment in drug delivery systems [92].

Carboxy Methyl Cellulose (CMC) has gained increased interest in pharmaceutical industries due to its hydrophilicity, stability, non-toxicity, biodegradability, and biocompatibility [93]. CMC has been utilized in pharmaceutical formulations as thickening agent, stabilizer, binder, film former, and in advanced drug delivery systems [94, 95].

The chemical composition of ethyl cellulose involves the conversion of certain hydroxyl groups on the repeating glucose units into ethyl ether groups [96]. Ethyl cellulose has gained interest in its use in drug delivery systems due to its biodegradability, non-toxicity, barrier-forming characteristics, and water resistance properties [97, 98].

Reacting ethylene oxide with alkali cellulose results in the synthesis of hydroxyethyl cellulose, which can be further modified to its reactive hydroxyl groups [99]. Hydroxyethyl cellulose has several interesting properties, such as its solubility in water and many organic solvents, non-toxicity, compatibility, and drug encapsulation properties. These characteristics have increased the interest towards employing hydroxyethyl cellulose in drug delivery [100, 101].

Partial or complete substitution of the free hydroxyls in cellulose to hydroxypropyl groups via the reaction with 1,2-propylene oxide results in the formation of hydroxypropyl cellulose [102]. Hydroxypropyl cellulose has been used in pharmaceutical formulations as tablets binder, viscosity enhancer, film coating, and in modified-release formulations [103, 104].

Cellulose acetate, a biodegradable polymer, is created through the esterification of cellulose [105]. Its exploration in various biomedical applications, such as tissue engineering [106], wound healing [107], and drug delivery systems [108], is attributed to its resource availability, cost-effectiveness, and straightforward isolation techniques.

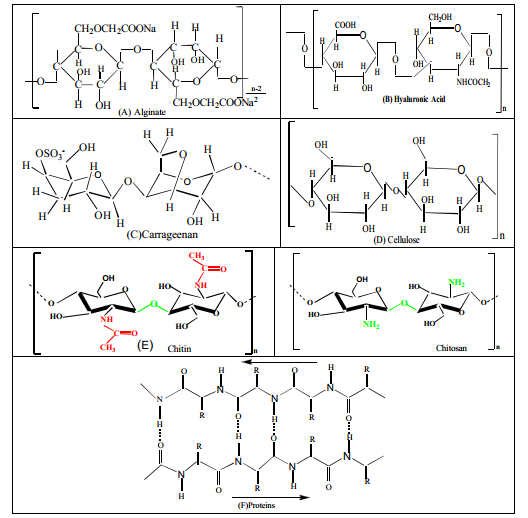

Fig. 1: Chemical structures of some natural polymers of potential to electrospinning: (A) Alginate, (B) Hyaluronic acid, (C) Carrageenan, (D) Cellulose, (E) Chitin and Chitosan, (F) Proteins [109]

Physicochemical properties of nanocrystalline cellulose

Nanocrystalline Cellulose (NCC) is a nanometer-sized rod-like particle with high crystallinity, obtained in the form of a stable aqueous colloidal suspension [110]. NCC has received increased interest as biomedical nano-carrier [111]. Its renewability, biocompatibility, biodegradability, abundance of active functional groups, and stability are the factors contributing to this interest [112]. Furthermore, NCC has interesting properties, including liquid crystallinity, colloidal behavior, self-assembling properties [113].

NCC stands out as the stiffest and strongest among natural materials [114], showcasing a range of notable properties such as high hardness, elevated tensile strength [114, 115], extensive surface area, high aspect ratio, and low density [115, 116], optical transparency, gas barrier properties [117], among other characteristics.

Thermally, NCC degrades or its mechanical properties decline at high temperatures, which limit its use; however, this property can be taken in advantage in some industries [118, 119].

NCC are characterized by their tensile properties, high crystallinity index, large surface area [120]. Moreover, NCC are characterized by their biocompatibility, biodegradibility, dispersion and water retention ability [121].

On the other hand, NCC possesses a range of remarkable optical, chemical, and electrical attributes attributed to its needle-like structure, expansive surface area, elevated aspect ratio (length-to-diameter ratio), exceptional crystallinity, nanoscale dimensions, impressive strength and rigidity, low density, and a pronounced negative charge. These distinctive qualities result in NCC exhibiting unique behaviors in solution.

Additionally, the high chemical reactivity of its surface renders NCC highly adaptable for diverse applications, complemented by its capacity to withstand high temperatures. Furthermore, NCC features abundant surface hydroxyl (OH) groups that serve as active sites for hydrogen bonding, facilitating interactions with polar matrices.

These elongated or whisker-shaped particles, measuring between 3 to 20 nanometers in width and 50 to 2000 nanometers in length, exhibit an extraordinary combination of attributes. They possess high axial stiffness, estimated at approximately 150 Giga Pascal (GPa), along with a remarkable tensile strength, believed to be around 7.5 GPa. Furthermore, they have a low coefficient of thermal expansion, approximately 1 part per million per degree Kelvin (ppm/K), and can maintain thermal stability up to approximately 300 °C.

With an impressive aspect ratio ranging from 10 to 100, these particles are characterized by low density, about 1.6 gs per cubic centimeter (g/cm³), display lyotropic liquid crystalline behavior, and exhibit shear-thinning rheology in Cellulose Nano Crystal (CNC) suspensions. Their exposed hydroxyl (–OH) groups on the CNC surfaces are easily modifiable, enabling the achievement of various surface properties. This adaptability has been harnessed to influence CNC self-assembly and dispersion across a broad spectrum of suspensions and matrix polymers. Additionally, it allows for the control of interfacial properties within composites, such as CNC-CNC and CNC-matrix interactions.

However, it's crucial to note that the dimensions and degree of crystallinity of these particles vary depending on the source of the cellulose and the specific extraction conditions. This variability has been documented in studies by researchers such as Habibi et al. (2010), Abdul-Khalil et al. (2014), and Abitol et al. (2016) [122-124].

Biological properties of nano-crystalline cellulose

Nano-crystalline cellulose exhibits several biological properties. This is because nanocrystalline cellulose are derived from biological materials such as plants, bacteria, tunicate, etc. Some of the most notable biological properties of nanocrystalline cellulose include the following fields:

Antibacterial properties

In a study by Eyley and Thielemans (2014), nanocrystalline cellulose was shown to have inherent antibacterial properties, suggesting its potential in the development of antibacterial materials for medical applications.

Biocompatibility

Nanocrystalline cellulose has been recognized for its excellent biocompatibility, making it appropriate for a wide array of biomedical applications. A study by Chen et al. (2018), revealed that nanocrystalline cellulose is not cytotoxic and is well tolerated by different types of cells, making it a promising material for application in drug delivery systems [125].

Wound healing applications

The ability of nanocrystalline cellulose to boost wound healing has been extensively explored. The researchers, cited by Klemm et al. (2011) investigated the use of nanocrystalline cellulose-based materials in wound dressings, attributing their success to the material's hemostatic properties and its ability to support cell adhesion [126].

Immunomodulatory effects

Recent research, as highlighted by Zhang et al. (2022), suggested that nanocrystalline cellulose may possess immunomodulatory effects, positively influencing the immune response. This opens up new possibilities for its use in immunotherapy and related fields [50].

Drug delivery systems

The high surface area of nanocrystalline cellulose and its gel-forming ability have given rise to its exploration in drug delivery systems. In a review by Habibi et al. (2010), the authors discuss the prospective of nanocrystalline cellulose-based nanocomposites in controlled drug release applications [122].

Uses of nanocrystalline cellulose

The potential uses of nanocrystalline cellulose can be broadly categorized according to distinctive combinations of their characteristics, and a selection of these categories is presented below.

Rheology modifiers

The incorporation of nanocrystalline cellulose can modify the rheological properties of diverse substances, including liquids, polymer melts, and particle mixtures, which are employed in a wide array of industrial sectors. These sectors encompass paints, coatings, adhesives, lacquers, as well as the production of food, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, and cement [127].

Reinforcement for polymer materials

Incorporating nanocrystalline cellulose into different polymer matrices brings about changes in the mechanical characteristics of the resulting composites. This alteration can be harnessed for creating resilient, pliable, long-lasting, lightweight, transparent, and dimensionally stable films, suitable for applications in packaging or structural composite materials.

Barrier films

Composites based on nanocrystalline cellulose, where nanocrystalline cellulose surface chemistry and the spacing between nanocrystalline cellulose are carefully customized, have generated attention as barrier films. These films show promise in applications like selective filtration, batteries, and packaging, as indicated by Hubbe et al., in 2008 [128].

Optical films or coatings

The liquid crystalline properties of nanocrystalline cellulose suspensions, combined with the birefringent characteristics of the particles, give rise to fascinating optical effects that can be harnessed to create distinctive pearlescent and iridescent optical patterns on surfaces.

Nano-crystalline cellulose-hybrid composites

nanocrystalline cellulose composites that incorporate inorganic nanoparticles or chemical compounds onto nanocrystalline cellulose surfaces and/or within nanocrystalline cellulose networks gain additional chemical functionalities. These functionalities have potential applications in biosensors, catalysis, photovoltaics, drug delivery, filtration, and antimicrobial technologies, as mentioned in Lin et al., 2012 [129].

Nanocrystalline cellulose foams

nanocrystalline cellulose foams, such as aerogels, exhibit a high degree of porosity with densities ranging from 0.01 to 0.4 g/cm3 and surface areas spanning from 30 to 600 m2/g, as documented previously [130]. These materials hold promise for utilization in lightweight packaging, core-skin structures for lightweight applications, and as insulation materials for thermal or vibration control.

Nanocrystalline cellulose continuous fibers

Continuous CNC-composite fibers, have been successfully manufactured using customary fiber spinning methods, such as electrospinning dry and wet spinning, as referenced in Peresin et al., study in 2010 [131]. These fibers offer potential applications in textile innovation and as reinforcements in both long and short fiber-reinforcement applications.

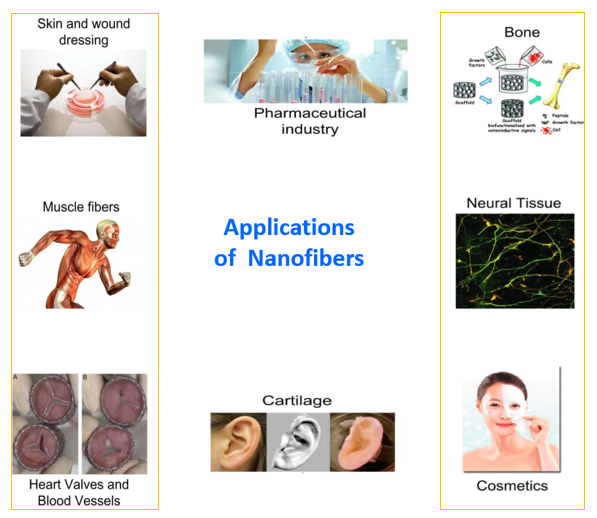

Importance of nanofibers

The production of nanofibers is noteworthy due to their significant attributes, such as a substantial aspect ratio, heightened porosity, and the potential to integrate active elements on a nanoscale. These qualities render them versatile for a broad spectrum of industries, encompassing semiconductors, protective materials like chemical-resistant cosmetics and sound absorption, water purification, and applications in clean energy, enzyme immobilization, and biosensor immunoassay. Among these applications, the biomedical sector stands out as particularly promising, embracing functions such as drug delivery carriers, dressing of wounds and tissue engineering. In tissue engineering, nanofiber scaffolds are intertwined with seeded cells. The porous structure, crucial for wound healing, facilitates the efficient diffusion of drug particles out of the matrix. The modulation of the rate of release of the drug can be achieved by regulating the thickness of the nanofibrous mat synthesized [132, 133].

Fig. 2: Applications of nanofibers

Production of nanofibers

Cellulose nanofibers can simply be obtained by pretreating the breaking down of the cellulose fibers followed by mechanical delimination. Cellulose nanofiber was first isolated by Turbak et al. in 1983 through the use of bleached softwood fibers through high pressure homogenization [134]. Cellulose nanofibers have also been obtained from cassava peel [135], banana [136], oil palm tree [137], “Helicteres isora plant” [138], seeds of “Citrullus colocynthis” [139], as well as, pear and apple [140]. There was little scientific and industrial interest because of the high energy requirement of the preparation procedure. As a result, successful pre-treatments have been researched over the years. These include partial carboxymethylation [141], enzymatic hydrolysis [142] and TEMPO catalytic oxidation [143]. Ul-Islam et al. (2015) reported that the advantages of TEMPO-mediated oxidation include mophological stability, high crystalinity maintenance and product yield, simple and eco-friendly operations, selectivity of primary alcohol, and profitability [144]. After pretreatment, the fibres are then passed through a process of mechanical decomposition at “high pressure, micro fluidization, friction grinding, extrusion, cryopressure, and high-intensity ultrasonication” [145]. Further research on work of has led to cellulose nanofibers being extracted from fibres from curauá and sugarcane pulp [146], lignocellulosic biomassof lemon grass [142].

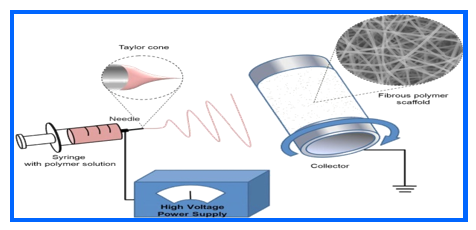

Electrospinning for nanofibers preparation

Electrospinning is a largely adopted procedure for the preparing cellulose-based composite nanofibers [148]. This technique involves the use of a high-voltage power source to create a liquid jet. Solid fibers are formed as this electrified jet consists of a high-viscosity polymer blend and is endlessly stretched due to the electrostatic repulsion resulting from surface charges and evaporation of solvent.

Nanofibers are generated by introducing a liquid polymer blend to form high electric field with the use of a capillary or tube syringe needle. When the electrostatic forces surpass the surface tension of the liquid, a Taylor cone is formed, propelling the thin jet rapidly towards various collecting plates. Instabilities in the jet cause a whipping motion that elongates and narrows the jet, allowing for the evaporation of some solvent or cooling of the melt, resulting in the deposition of nanofibers on the collecting plates. Consequently, this process yields random non-woven films, electrospun nanofibers, and uniaxially aligned sheets [149].

Nanofibers produced through electrospinning find a wide array of use in the medical industry. By integrating nanoparticles, antimicrobial agents, and drug molecules into nanofibrous dressings, the risk of infection can be reduced, making them a promising solution for inflammation control and antibacterial properties [150, 151].

Fig. 3: Preparation of nanofibers by electrospinning

Preparation of nanocrystalline cellulose nanofibers

Nanocrystalline cellulose is one of the most studied type of nanocellulose. The colloidal sulphuric acid-crystalysed breakdown of cellulose fibers was first reported by Ranby in 1951 [152]. An array of nanocrystiline cellulose preparations were made from various sources, including wood [153], olive tree [154, 155], cotton [156], tunicate [157], sisal [158], bacterial [159], microcrystalline cellulose [160], and from waste material and biomass. Nanocrystalline cellulose obtained from acid hydrolysis of native cellulose has different morphological properties depending on its origin as well as the hydrolysis conditions [161]. According to Elazzouzi-Hafraoui et al. (2008), the separation of nanocrystalline cellulose from cellulose is founded on controlled hydrolysis of sulfuric acid, leading to a suspension that is moderately stable [162]. The weakest amorphous regions of local cellulose are hydrolyzed by acid treatment, and the resulting material changes its crystalline form. Besides sulfuric acid, high-temperature hydrochloric, phosphoric and hydrobromic acids were also used to create aqueous structures at elevated temperatures [163, 164].

The common acid hydrolysis method for the preparation of individual cellulose entails the use of acid acids to treat cellulose at elevated temperatures under uninterrupted stirring. Dilution with water followed by centrifugation and then washing with water to get rid of too much acid can bring the reaction to end. Dong et al. (1998) gave a detail technique for hydrolysis of cellulose by sulfuric acid application [165]. In 2011, a preparation of surface Carboxylated NCC (c-NCC) by oxidation of cotton linter pulp using “2, 2, 6, 6-Tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl (TEMPO)-NaBr-NaClO” method with ultrasonic treatment, was done [166]. In like-manner, Leung et al. (2011) prepared c-NCC, oxidation through the application of ammonium per-sulfate at 60 °C [167].

Nanocrystalline cellulose nanofibers for drug delivery applications

Oral drug delivery

According to Jackson et al. (2011), a great deal of research has been carried out on the oral application of various kinds of nanocellulose [168]. Burt et al. (2014) used nanocrystalline cellulose as a booster for some anticancer medications like paclitaxel, docetaxel and etoposide. The modification of the nanocrystalline cellulose surface was done by binding CTAB, a cationic surfactant, leading to a rise in the zeta potential of nanocrystalline cellulose in manner that was dependent on concentration [169]. The outcomes indicated a guided release of drugs for many days. Emaraa and colleagues (2016) conducted an investigation into the impact of NCC (nanocellulose crystals) and “Micro Crystalline Cellulose (MCC)” transporters on the solubility of a low water-soluble drug. Their findings revealed that an elevation in the NCC loading led to an augmentation in drug solubility. As a result, this research substantiates the suitability of NCC as a carrier for drugs with low water solubility [170].

Cellulose Nanofiber (CNF) is a captivating material owing to its distinct physicochemical attributes across various interfaces. CNF offers a substantial specific surface area that fosters favorable interactions with drugs, enhancing their efficacy. Additionally, cellulose nanofiber exhibits mechanical properties that bolster the structural integrity of pharmaceutical dosage forms. Furthermore, as a result of the robust nanofiber-nanofiber interactions and high crystallinity, cellulose nanofiber films display exceptional oxygen barrier capabilities, particularly under low humidity conditions [171]. This improvement in oxygen barrier properties enhances the oxidative stability of drugs that are oxygen-sensitive during storage, making cellulose nanofiber an effective choice as a pharmaceutical excipient. Cellulose nanofiber has also been applied for instant release of drugs in paricles [172], “tablets” [173], and “capsules” as well as in form of film for regulated release of drugs [174].

In various research studies, Cellulose Nanofiber (CNF) combined with non-edible surfactants has been effectively employed through the Pickering method to enclose air bubbles, forming stable air bubble structures. This innovative approach has been documented by several authors, including Kolakovic et al. (2012), Cervin, et al. (2016) [172, 175]. These three-dimensional closed-cell structures have demonstrated their utility as promising systems for the controlled and continuous release of drugs in medical applications. Notably, these aerogels can rapidly fill with liquid if their pockets are interlinked, leading to an enhanced medication release as a result of their larger surface area, as highlighted by Häbel et al. (2016) [176].

Guo et al. (2017) developed two types of beads for metformin hydrochloride release: CNF/alginate and MCC/alginate. CNF enhanced both mechanical properties and swelling, while alginate acted as the carrier for drug delivery. Notably, the aggregate release from the CNF/alginate beads surpassed that of MCC/alginate by 10%. Furthermore, the CNF/alginate beads exhibited a sustained release profile lasting up to 240 min [177].

A controlled release scheme for dimethyl phthalate was introduced by Patil et al. (2018), utilizing nanocomposites composed of urea-formaldehyde and gelatinized corn starch with the addition of cellulose nanofiber. While the first release of “dimethyl phthalate” was notably inhibited by CNF, it effectively facilitated the regulated release of the drug. The researchers concluded that the presence of a network within the starch matrix created an indirect pathway, resulting in a prolonged release, with approximately eighty to ninety-five percent of the drug being released over the course of a week [178]. In a related study, Supramaniam et al. (2018) developed nanocellulose alginate magnetic hydrogel beads, denoted as m-NCC, designed for the controlled and extended release of ibuprofen over a period of 30 to 330 min. These m-NCC beads not only held promise for targeted drug delivery and detection, particularly in cancerous tissue using MRI, but they also contributed to enhancing the release characteristics and mechanical strength of the drug [179]. Another noteworthy development in this field was reported by Thomas and colleagues, who prepared a nano-sized alginate-nanocrystalline hybrid polymer formulation with high “Encapsulation Efficiency” (EE). This formulation was designed for guided oral medication of rifampicin, showing potential for improved outcomes in treating “Mycobacterium tuberculosis” [180].

Hivechi et al. (2019) described the synthesis of nanofibers made from Poly Capro Lactone (PCL) reinforced with Nano Crystalline Cellulose (NCC). Their research primarily examined the guided release of Tetra Cycline Hydrochloride (TCH). Notably, they found that augmenting the concentration of NCC in the PCL nanofibers led to a reduction in the rate of drug release [181].

Transdermal drug delivery

Transdermal Drug Delivery Systems (TDDS) are designed to administer drugs through the skin, allowing for systemic absorption to accomplish therapeutic concentrations. This method by passes the digestive tract and liver metabolism, resulting in a therapeutic effect with lower doses of the drug. As a significant benefit, TDDS reduces the likelihood of hepatic and gastrointestinal side effects [182]. Nevertheless, it's important to note that TDDS has limitations, as it is not suitable for delivering larger drugs. Its application is primarily restricted to small drugs that can effectively enter the skin [183].

Cellulose Nanofibers (CNF) hold significant potential for transdermal drug delivery systems (TDDS). Sarkar et al. (2017) for instance, developed a CNF/chitosan transcutaneous film for the delivery of ketorolac tromethamine, with cellulose nanofiber serving as a supportive component, making it a promising candidate for controlled TDDS [16]. In a separate study, Kolković et al. (2012) investigated the use of cellulose nanofiber as a base material in the production of sustained-release transdermal devices incorporating drugs such as indomethacin, beclomethasone and itraconazole. Using filtration techniques, they loaded the drug into the membrane matrix system at concentrations ranging from 20% to 40%. Their observations showed that drug release was sustained over a period of three months. This emphasizes the appeal of CNF as a material to control the release of drugs with low water solubility.

Various formulations based on nanocellulose, like the NFC/hydroxypropyl methylcellulose nanocomposite (Orasugh et al., 2018) and the nanogold-nanocellulose composite (GNPNC) (Anirudhan and Nair, 2017), have exhibited potential in regulating drug release within transdermal drug delivery systems (TDDS). Furthermore, Bhandari et al. (2017) devised drug-loaded CNF aerogels deliberately engineered to encapsulate water-soluble drugs via physical adsorption. During in vitro assessments, both DCNF and CNF aerogels demonstrated their efficacy in facilitating drug delivery through the skin, showcasing the adaptability of CNF in this particular domain.

Local drug delivery

Local drug applications systems aim to administer drugs precisely at or in proximity to the target site, thereby improving treatment efficacy while reducing the necessary dosage. This strategy confines drug exposure to the specific area, decreasing the likelihood of systemic exposure and potential toxicity to healthy tissues [163].

In a research conducted by Laurén et al. (2014), cellulose nanofibers hydrogels emerged as a potentially potent matrix for controlled release or localized delivery of large molecules like peptide and proteins drugs [115]. Additionally, Laurén et al. (2018) developed adhesive films for drug delivery using biodegradable and atoxic polymers. These membranes use a combination of binder components, incorporating cellulose nanofibers and Anionic CNF (ACNF) as the film-forming material [117]. Functional bioadhesion activators such as mucin, pectin and chitosan were used for controlled application of metronidazole. The findings indicated a swift drug release, which proved advantageous in treating oral conditions like periodontitis. This rapid release ensured the patch became inactive upon detachment, making it well-suited for localized drug administration, where a quick and potent local dose is often preferred. Furthermore, a recent study by Bertsch et al. (2019) highlighted the synthesis of hydrogels derived from cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs) via a salt-induced charge screening method. These hydrogels demonstrated sustained release patterns for proteins “(such as Bovine Serum Albumin or BSA)”, low water-soluble tetracycline, and moderately soluble doxorubicin. In the case of tetracycline, the initial release was within 2 days, while BSA and doxorubicin demonstrated sustained release over a period of up to two weeks.

CONCLUSION

This review has attempted to provide general information on the many characteristics and functions of nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC) and nanofibers. It has been established that nanocrystalline cellulose obtained by synthetic methods (mechanical and chemical) have more excellent dimensions and greater heat resistance. Due to the properties of nanocrystalline such as size, lack of immune response in the body, biodegradability, low cytotoxicity and hydrophilic properties caused by hydroxyl groups, its potential to be used in different drug delivery systems have been increased. The available hydroxyl groups in its structure make its surface as well as nanocrystalline nanofibers surface, very flexible for adding different chemical groups, leading to effective drug release in the body. This also makes nanocrystalline nanofibers very useful in targeted drug delivery, in addition to different applications in the biomedical fields such as diagnostics and biosensing, vascular graft replacement, tissue engineering, antibacterial and antiviral applications, regenerative medicine, printing applications, wound healing and optical applications.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The author is grateful to the Middle East University, Amman, Jordan for the financial support granted to cover the publication fee of this article.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Nawzat D. AlJbour is the principle investigator contributed in writing, revising, and formatting the manuscript. Enas A. Alkhader contributed in writing the manuscript. Mohammad D. Beg contributed in revising the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Jorfi M, Foster EJ. Recent advances in nanocellulose for biomedical applications. J Appl Polym Sci. 2015 Apr 10;132(14). doi: 10.1002/app.41719.

Satyanarayana KG, Arizaga GG, Wypych F. Biodegradable composites based on lignocellulosic fibers an overview. Prog Polym Sci. 2009;34(9):982-1021. doi: 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2008.12.002.

Majeed K, Jawaid M, Hassan A, Abu Bakar A, Abdul Khalil HP, Salema AA. Potential materials for food packaging from nanoclay/natural fiber-filled hybrid composites. Mater Des. 2013 Apr;46:391-410. doi: 10.1016/j.matdes.2012.10.044.

Herrera Franco PJ, Valadez Gonzalez A. A study of the mechanical properties of short natural fiber reinforced composites. Composites Part B: Engineering. 2005;36(8):597-608. doi: 10.1016/j.compositesb.2005.04.001.

Kim IY, Seo SJ, Moon HS, Yoo MK, Park IY, Kim BC. Chitosan and its derivatives for tissue engineering applications. Biotechnol Adv. 2008;26(1):1-21. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2007.07.009, PMID 17884325.

Correa AC, DE Morais Teixeira E, Pessan LA, Mattoso LH. Cellulose nanofibers from curaua fibers. Cellulose. 2010;17(6):1183-92. doi: 10.1007/s10570-010-9453-3.

Mohamad Haafiz MK, Eichhorn SJ, Hassan A, Jawaid M. Isolation and characterization of microcrystalline cellulose from oil palm biomass residue. Carbohydr Polym. 2013;93(2):628-34. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.01.035, PMID 23499105.

Kalia S, Dufresne A, Cherian BM, Kaith BS, Averous L, Njuguna J. Cellulose-based bio and nanocomposites: a review. Int J Polym Sci. 2011;2011:1-35. doi: 10.1155/2011/837875.

Oksman K, Mathew AP, Langstrom R, Nystrom B, Joseph K. The influence of fibre microstructure on fibre breakage and mechanical properties of natural fibre reinforced polypropylene. Compos Sci Technol. 2009;69(11-12):1847-53. doi: 10.1016/j.compscitech.2009.03.020.

Puri VP. Effect of crystallinity and degree of polymerization of cellulose on enzymatic saccharification. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1984;26(10):1219-22. doi: 10.1002/bit.260261010, PMID 18551639.

LI C, Wang J, Wang Y, Gao H, Wei G, Huang Y. Recent progress in drug delivery. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2019;9(6):1145-62. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2019.08.003, PMID 31867161.

Amgoth C, Phan C, Banavoth M, Rompivalasa S, Tang G. Polymer properties: functionalization and surface modified nanoparticles. In: role of novel drug delivery vehicles in nanobiomedicine. 1st ed. Intech Open; 2019.

Chander A, Santhosh R, Avinash S, Priyanka M, Guping T, Murali B. Polymeric nanoparticles: preparation and surface modification. In: Kumar V, Guleria P, Dasgupta N, Ranjan S, editors. Functionalized nanomaterials. 1st ed. Vol. I. CRC Press; 2020. p. 161-70. doi: 10.1201/9781351021623-10.

Bharadwaz A, Jayasuriya AC. Recent trends in the application of widely used natural and synthetic polymer nanocomposites in bone tissue regeneration. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2020;110:110698. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2020.110698, PMID 32204012.

Luckachan GE, Pillai CK. Biodegradable polymers a review on recent trends and emerging perspectives. J Polym Environ. 2011;19(3):637-76. doi: 10.1007/s10924-011-0317-1.

Sarkar T, Ahmed AB. Development and in vitro characterization of chitosan-loaded paclitaxel nanoparticle. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2016;9(9) Suppl 3:145-8. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2016.v9s3.12894.

Moussa A. Synthesis and characterization of chitosan oligomers for biomedical applications. 1st ed. Universite De Lyon; 2019.

Kashyap PL, Xiang X, Heiden P. Chitosan nanoparticle based delivery systems for sustainable agriculture. Int J Biol Macromol. 2015;77:36-51. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.02.039, PMID 25748851.

Islam MM, Shahruzzaman M, Biswas S, Nurus Sakib MN, Rashid TU. Chitosan-based bioactive materials in tissue engineering applications a review. Bioact Mater. 2020;5(1):164-83. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2020.01.012, PMID 32083230.

Mikusova V, Mikus P. Advances in chitosan-based nanoparticles for drug delivery. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(17):9652. doi: 10.3390/ijms22179652, PMID 34502560.

Parhi R. Drug delivery applications of chitin and chitosan: a review. Environ Chem Lett. 2020;18(3):577-94. doi: 10.1007/s10311-020-00963-5.

Agarwal T, Chiesa I, Costantini M, Lopamarda A, Tirelli MC, Borra OP. Chitosan and its derivatives in 3D/4D (bio) printing for tissue engineering and drug delivery applications. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023 Aug 15;246:125669. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.125669, PMID 37406901.

Karayianni M, Sentoukas T, Skandalis A, Pippa N, Pispas S. Chitosan based nanoparticles for nucleic acid delivery: technological aspects applications and future perspectives. Pharmaceutics. 2023;15(7):1849. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics15071849, PMID 37514036.

Nerli G, Robla S, Bartalesi M, Luceri C, D Ambrosio M, Csaba N. Chitosan coated niosomes for nose to brain delivery of clonazepam: formulation stability and permeability studies. Carbohydrate Polymer Technologies and Applications. 2023 Dec;6:1-9. doi: 10.1016/j.carpta.2023.100332.

Hard SA, Shivakumar HN, Redhwan MA. Development and optimization of in situ gel containing chitosan nanoparticles for possible nose to brain delivery of vinpocetine. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;253(6):127217. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.127217, PMID 37793522.

Gabold B, Adams F, Brameyer S, Jung K, Ried CL, Merdan T. Transferrin modified chitosan nanoparticles for targeted nose to brain delivery of proteins. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2023;13(3):822-38. doi: 10.1007/s13346-022-01245-z, PMID 36207657.

Bhaskaran NA, Jitta SR, Salwa KL, Kumar L, Sharma P, Kulkarni OP. Folic acid chitosan functionalized polymeric nanocarriers to treat colon cancer. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;253(5):127142. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.127142, PMID 37797853.

Alsadooni JF, Haghi M, Barzegar A, Feizi MA. The effect of chitosan hydrogel containing gold nanoparticle complex with paclitaxel on colon cancer cell line. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023 Aug 30;247:125612. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.125612, PMID 37390995.

Leonard TE, Liko AF, Gustiananda M, Putra AB, Juanssilfero AB, Hartrianti P. Thiolated pectin chitosan composites: potential mucoadhesive drug delivery system with selective cytotoxicity towards colorectal cancer. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023 Jan15;225:1-12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.12.012, PMID 36481327.

Hasnain MS, Jameel E, Mohanta B, Dhara AK, Alkahtani S, Nayak AK. Alginates: sources structure and properties. In: Alginates in drug delivery. Elsevier; 2020. p. 1-17. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-817640-5.00001-7.

Pagliaccia B. Insights on the recovery characterization and valorization of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) from granular sludge applied in innovative wastewater treatment systems. INSA De Toulouse. Universite DE Florence; 2022.

Rosiak P, Latanska I, Paul P, Sujka W, Kolesinska B. Modification of alginates to modulate their physic-chemical properties and obtain biomaterials with different functional properties. Molecules. 2021;26(23):7264. doi: 10.3390/molecules26237264, PMID 34885846.

Hariyadi DM, Islam N. Current status of alginate in drug delivery. Adv Pharmacol Pharm Sci. 2020;2020:8886095. doi: 10.1155/2020/8886095, PMID 32832902.

Severino P, DA Silva CF, Andrade LN, DE Lima Oliveira D, Campos J, Souto EB. Alginate nanoparticles for drug delivery and targeting. Curr Pharm Des. 2019;25(11):1312-34. doi: 10.2174/1381612825666190425163424, PMID 31465282.

Chuang JJ, Huang YY, LO SH, Hsu TF, Huang WY, Huang SL. Effects of pH on the shape of alginate particles and its release behavior. Int J Polym Sci. 2017;2017:1-9. doi: 10.1155/2017/3902704.

Ahmad Z, Sharma S, Khuller GK. Chemotherapeutic evaluation of alginate nanoparticle encapsulated azole antifungal and antitubercular drugs against murine tuberculosis. Nanomedicine. 2007;3(3):239-43. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2007.05.001, PMID 17652032.

Ahmad Z, Sharma S, Khuller GK. Inhalable alginate nanoparticles as antitubercular drug carriers against experimental tuberculosis. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2005;26(4):298-303. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2005.07.012, PMID 16154726.

Shaji J, Shaikh M. Formulation optimization and characterization of biocompatible inhalable d-cycloserine loaded alginate chitosan nanoparticles for pulmonary drug delivery. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2016;9(2):82-95. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2016.v9s2.11814.

Alipour S, Montaseri H, Tafaghodi M. Preparation and characterization of biodegradable paclitaxel loaded alginate microparticles for pulmonary delivery. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2010;81(2):521-9. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2010.07.050, PMID 20732796.

Mahmoud AA, Elkasabgy NA, Abdelkhalek AA. Design and characterization of emulsified spray-dried alginate microparticles as a carrier for the dually acting drug Roflumilast. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2018 Sep 15;122:64-76. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2018.06.015, PMID 29928985.

Hussein N, Omer H, Ismael A, Albed Alhnan M, Elhissi A, Ahmed W. Spray dried alginate microparticles for potential intranasal delivery of ropinirole hydrochloride: development characterization and histopathological evaluation. Pharm Dev Technol. 2020;25(3):290-9. doi: 10.1080/10837450.2019.1567762, PMID 30626225.

Mali AJ, Pawar AP, Bothiraja C. Improved lung delivery of budesonide from biopolymer-based dry powder inhaler through natural inhalation of rat. Materials Technology. 2014;29(6):350-7. doi: 10.1179/1753555714Y.0000000163.

Nami S, Aghebati Maleki A, Aghebati Maleki L. Current applications and prospects of nanoparticles for antifungal drug delivery. Excli J. 2021 Mar 8;20:562-84. doi: 10.17179/excli2020-3068, PMID 33883983.

Belinskaia DA, Voronina PA, Batalova AA, Goncharov NV. Serum albumin. Encyclopedia. 2020;1(1):65-75. doi: 10.3390/encyclopedia1010009.

Van Der Vusse GJ. Albumin as fatty acid transporter. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2009;24(4):300-7. doi: 10.2133/dmpk.24.300, PMID 19745557.

Spada A, Emami J, Tuszynski JA, Lavasanifar A. The uniqueness of albumin as a carrier in nano-drug delivery. Mol Pharm. 2021;18(5):1862-94. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.1c00046, PMID 33787270.

Kianfar E. Protein nanoparticles in drug delivery: animal protein plant proteins and protein cages albumin nanoparticles. J Nanobiotechnology. 2021;19(1):159. doi: 10.1186/s12951-021-00896-3, PMID 34051806.

Tayyab S, Feroz SR. Serum albumin: clinical significance of drug binding and development as drug delivery vehicle. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol. 2021;123:193-218. doi: 10.1016/bs.apcsb.2020.08.003, PMID 33485484.

Lee H, Park S, Kang JE, Lee HM, Kim SA, Rhie SJ. Efficacy and safety of nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel compared with solvent-based taxanes for metastatic breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):530. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-57380-0, PMID 31953463.

Zhang S, Zhou Y, Zhang W, LU W. Immunomodulatory effects of cellulose nanocrystals: a review. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2022;10:103-26.

Kumari P, Paul M, Bobde Y, Soniya K, Kiran Rompicharla SV, Ghosh B. Albumin based lipoprotein nanoparticles for improved delivery and anticancer activity of curcumin for cancer treatment. Nanomedicine (Lond). 2020;15(29):2851-69. doi: 10.2217/nnm-2020-0232, PMID 33275041.

Solanki R, Patel K, Patel S. Bovine serum albumin nanoparticles for the efficient delivery of berberine: preparation characterization and in vitro biological studies. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects. 2021;608:125-50. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2020.125501.

YU Z, LI X, Duan J, Yang XD. Targeted treatment of colon cancer with aptamer guided albumin nanoparticles loaded with docetaxel. Int J Nanomedicine. 2020 Sep 11;15:6737-48. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S267177, PMID 32982230.

Gong T, Tan T, Zhang P, LI H, Deng C, Huang Y. Palmitic acid modified bovine serum albumin nanoparticles target scavenger receptor a on activated macrophages to treat rheumatoid arthritis. Biomaterials. 2020;258:120296. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.120296, PMID 32781326.

Scutera S, Argenziano M, Sparti R, Bessone F, Bianco G, Bastiancich C. Enhanced antimicrobial and antibiofilm effect of new colistin loaded human albumin nanoparticles. Antibiotics (Basel). 2021;10(1):57. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10010057, PMID 33430076.

Zhang K, LI D, Zhou B, Liu J, Luo X, Wei R. Arsenite loaded albumin nanoparticles for targeted synergistic chemo photothermal therapy of HCC. Biomater Sci. 2021;10(1):243-57. doi: 10.1039/d1bm01374b, PMID 34846385.

Giri S, Dutta P, Kumarasamy D, Giri TK. Natural polysaccharides: types basic structure and suitability for forming hydrogels. In: Plant and algal hydrogels for drug delivery and regenerative medicine. 1st ed. Elsevier; 2021. p. 1-35. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-821649-1.00007-6.

Burke SE, Barrett CJ. pH-responsive properties of multilayered poly(L-lysine)/hyaluronic acid surfaces. Biomacromolecules. 2003;4(6):1773-83. doi: 10.1021/bm034184w, PMID 14606908.

Kulkarni SS, Patil SD, Chavan DG. Extraction purification and characterization of hyaluronic acid from rooster comb. JANS. 2018;10(1):313-5. doi: 10.31018/jans.v10i1.1623.

Kotla NG, Mohd Isa IL, Larranaga A, Maddiboyina B, Swamy SK, Sivaraman G. Hyaluronic acid based bioconjugate systems scaffolds and their therapeutic potential. Adv Healthc Mater. 2023;12(20):e2203104. doi: 10.1002/adhm.202203104, PMID 36972409.

Vasvani S, Kulkarni P, Rawtani D. Hyaluronic acid: a review on its biology aspects of drug delivery route of administrations and a special emphasis on its approved marketed products and recent clinical studies. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;151:1012-29. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.11.066, PMID 31715233.

Witting M, Boreham A, Brodwolf R, Vavrova K, Alexiev U, Friess W. Interactions of hyaluronic acid with the skin and implications for the dermal delivery of biomacromolecules. Mol Pharm. 2015;12(5):1391-401. doi: 10.1021/mp500676e, PMID 25871518.

Yang JA, Kim ES, Kwon JH, Kim H, Shin JH, Yun SH. Transdermal delivery of hyaluronic acid human growth hormone conjugate. Biomaterials. 2012;33(25):5947-54. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.05.003, PMID 22632765.

Fallacara A, Marchetti F, Pozzoli M, Citernesi UR, Manfredini S, Vertuani AS. Formulation and characterization of native and crosslinked hyaluronic acid microspheres for dermal delivery of sodium ascorbyl phosphate: a comparative study. Pharmaceutics. 2018;10(4):254. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics10040254, PMID 30513791.

Schulz A, Rickmann A, Wahl S, Germann A, Stanzel BV, Januschowski K. Alginate and hyaluronic acid based hydrogels as vitreous substitutes: an in vitro evaluation. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2020;9(13):34. doi: 10.1167/tvst.9.13.34, PMID 33384888.

Jiang JL, Zhang WZ, NI WX, Shao JW. Insight on structure-property relationships of carrageenan from marine red algal: a review. Carbohydr Polym. 2021;257:117642. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.117642, PMID 33541666.

Gomes Dos Reis L, Ghadiri M, Young P, Traini D. Nasal powder formulation of tranexamic acid and hyaluronic acid for the treatment of epistaxis. Pharm Res. 2020;37(10):186. doi: 10.1007/s11095-020-02913-w, PMID 32888133.

Tratnjek L, Simic L, Vukelic K, Knezevic Z, Kreft ME. Novel nasal formulation of xylometazoline with hyaluronic acid: in vitro ciliary beat frequency study. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2023 Nov;192:136-46. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2023.10.002, PMID 37804998.

Naomi R, Bahari H, Ridzuan PM, Othman F. Natural based biomaterial for skin wound healing (gelatin vs. collagen): expert review. Polymers. 2021;13(14):2319. doi: 10.3390/polym13142319, PMID 34301076.

Arun A, Malrautu P, Laha A, Ramakrishna S. Gelatin nanofibers in drug delivery systems and tissue engineering. Eng Sci. 2021;16:71-81. doi: 10.30919/es8d527.

ReferencesHussain A, Hasan A, Babadaei MM, Bloukh SH, Edis Z, Rasti B. Application of gelatin nanoconjugates as potential internal stimuli responsive platforms for cancer drug delivery. J Mol Liq. 2020 Nov 15;318:114053. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.114053.

Raza F, Siyu L, Zafar H, Kamal Z, Zheng B, SU J. Recent advances in gelatin-based nanomedicine for targeted delivery of anti-cancer drugs. Curr Pharm Des. 2022;28(5):380-94. doi: 10.2174/1381612827666211102100118, PMID 34727851.

Madkhali OA. Drug delivery of gelatin nanoparticles as a biodegradable polymer for the treatment of infectious diseases: perspectives and challenges. Polymers. 2023;15(21):4327. doi: 10.3390/polym15214327, PMID 37960007.

Wan Ishak WH, Rosli NA, Ahmad I, Ramli S, Mohd Amin MC. Drug delivery and in vitro biocompatibility studies of gelatin nanocellulose smart hydrogels cross-linked with gamma radiation. J Mater Res Technol. 2021;15:7145-57. doi: 10.1016/j.jmrt.2021.11.095.

Bertsch P, Andree L, Besheli NH, Leeuwenburgh SC. Colloidal hydrogels made of gelatin nanoparticles exhibit fast stress relaxation at strains relevant for cell activity. Acta Biomater. 2022 Jan 15;138:124-32. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2021.10.053, PMID 34740854.

Freitas CM, Coimbra JS, Souza VG, Sousa RC. Structure and applications of pectin in food biomedical and pharmaceutical industry: a review. Coatings. 2021;11(8):922. doi: 10.3390/coatings11080922.

Wusigale L, Liang L, Luo Y. Casein and pectin: structures interactions and applications. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2020;97:391-403. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2020.01.027.

Ropartz D, Ralet MC. Pectin structure. In: Kontogiorgos V, editor. Pectin: technological and physiological properties. 1st ed. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 17-36. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-53421-9_2.

Khotimchenko M. Pectin polymers for colon targeted antitumor drug delivery. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020 Sep 1;158:1110-24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.05.002, PMID 32387365.

Shehata EM, Gowayed MA, El Ganainy SO, Sheta E, Elnaggar YS, Abdallah OY. Pectin-coated nanostructured lipid carriers for targeted piperine delivery to hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Pharm. 2022;619:121712. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2022.121712, PMID 35367582.

Lee S, Woo C, KI CS. Pectin nanogel formation via thiol norbornene photo click chemistry for transcutaneous antigen delivery. J Ind Eng Chem. 2022 Apr 25;108:159-69. doi: 10.1016/j.jiec.2021.12.038.

Guo Z, Wei Y, Zhang Y, XU Y, Zheng L, Zhu B. Carrageenan oligosaccharides: a comprehensive review of preparation isolation purification structure biological activities and applications. Algal Res. 2022;61:102-52. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2021.102593.

Shafie MH, Kamal ML, Zulkiflee FF, Hasan S, Uyup NH, Abdullah S. Application of carrageenan extract from red seaweed (Rhodophyta) in cosmetic products: a review. J Indian Chem Soc. 2022;99(9):100613. doi: 10.1016/j.jics.2022.100613.

Liu F, Duan G, Yang H. Recent advances in exploiting carrageenans as a versatile functional material for promising biomedical applications. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;235:123787. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.123787, PMID 36858089.

Yegappan R, Selvaprithiviraj V, Amirthalingam S, Jayakumar R. Carrageenan based hydrogels for drug delivery tissue engineering and wound healing. Carbohydr Polym. 2018;198:385-400. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.06.086, PMID 30093014.

Neamtu B, Barbu A, Negrea MO, Berghea Neamtu CS, Popescu D, Zahan M. Carrageenan-based compounds as wound healing materials. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(16):9117. doi: 10.3390/ijms23169117, PMID 36012381.

Heinze T. Cellulose: structure and properties. In: Rojas Oj, editor. Cellulose chemistry and properties: fibers nanocelluloses and advanced materials. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2015. p. 1-52. doi: 10.1007/12_2015_319.

Lukova P, Katsarov P, Pilicheva B. Application of starch cellulose and their derivatives in the development of microparticle drug delivery systems. Polymers. 2023;15(17):3615. doi: 10.3390/polym15173615, PMID 37688241.

HU W, Chen S, Yang J, LI Z, Wang H. Functionalized bacterial cellulose derivatives and nanocomposites. Carbohydr Polym. 2014;101:1043-60. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.09.102, PMID 24299873.

Rana AK, Frollini E, Thakur VK. Cellulose nanocrystals: pretreatments preparation strategies and surface functionalization. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021;182:1554-81. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.05.119, PMID 34029581.

Jedvert K, Heinze T. Cellulose modification and shaping a review. J Polym Eng. 2017;37(9):845-60. doi: 10.1515/polyeng-2016-0272.

Siepmann J, Peppas NA. Modeling of drug release from delivery systems based on hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC). Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;48(2-3):139-57. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00112-0, PMID 11369079.

Pourmadadi M, Rahmani E, Shamsabadipour A, Samadi A, Esmaeili J, Arshad R. Novel carboxymethyl cellulose-based nanocomposite: a promising biomaterial for biomedical applications. Process Biochem. 2023;130:211-26. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2023.03.033.

Paria A, Rai VK. The fate of carboxymethyl cellulose as a polymer of pharmaceutical importance. biolsciences. 2022;2(2):204-15. doi: 10.55006/biolsciences.2022.2204.

Rahman MS, Hasan MS, Nitai AS, Nam S, Karmakar AK, Ahsan MS. Recent developments of carboxymethyl cellulose. Polymers. 2021;13(8):1345. doi: 10.3390/polym13081345, PMID 33924089.

Arca HC, Mosquera Giraldo LI, BI V, XU D, Taylor LS, Edgar KJ. Pharmaceutical applications of cellulose ethers and cellulose ether esters. Biomacromolecules. 2018;19(7):2351-76. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.8b00517, PMID 29869877.

Gunduz O, Ahmad Z, Stride E, Edirisinghe M. Continuous generation of ethyl cellulose drug delivery nanocarriers from microbubbles. Pharm Res. 2013;30(1):225-37. doi: 10.1007/s11095-012-0865-7, PMID 22956171.

Rani AP, Archana N, Teja PS, Vikas PM, Kumar MS, Sekaran CB. Formulation and evaluation of orodispersible metformin tablets: a comparative study on isphagula husk and cross povidone as superdisintegrants. Int J Appl Pharm. 2010;2(3):15-21.

Abdel Halim ES. Chemical modification of cellulose extracted from sugarcane bagasse: preparation of hydroxyethyl cellulose. Arab J Chem. 2014;7(3):362-71. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2013.05.006.

Bekaroglu MG, Isci Y, Isci S. Colloidal properties and in vitro evaluation of hydroxy ethyl cellulose coated iron oxide particles for targeted drug delivery. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2017;78:847-53. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2017.04.030, PMID 28576058.

Mianehrow H, Afshari R, Mazinani S, Sharif F, Abdouss M. Introducing a highly dispersed reduced graphene oxide nano biohybrid employing chitosan/hydroxyethyl cellulose for controlled drug delivery. Int J Pharm. 2016;509(1-2):400-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2016.06.015, PMID 27286635.

Abdel Halim ES, Al Deyab SS. Utilization of hydroxypropyl cellulose for green and efficient synthesis of silver nanoparticles. Carbohydr Polym. 2011;86(4):1615-22. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2011.06.072.

Lee BJ, Ryu SG, Cui JH. Formulation and release characteristics of hydroxypropyl methylcellulose matrix tablet containing melatonin. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 1999;25(4):493-501. doi: 10.1081/DDC-100102199, PMID 10194604.

Takeuchi Y, Umemura K, Tahara K, Takeuchi H. Formulation design of hydroxypropyl cellulose films for use as orally disintegrating dosage forms. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2018 Aug;46:93-100. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2018.05.002.

Kumar V, Yang D. Oxidized cellulose esters: I. Preparation and characterization of oxidized cellulose acetates a new class of biodegradable polymers. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2002;13(3):273-86. doi: 10.1163/156856202320176529, PMID 12102594.

Nosar MN, Salehi M, Ghorbani S, Beiranvand SP, Goodarzi A, Azami M. Characterization of wet electrospun cellulose acetate based 3-dimensional scaffolds for skin tissue engineering applications: influence of cellulose acetate concentration. Cellulose. 2016;23(5):3239-48. doi: 10.1007/s10570-016-1026-7.

Dos Santos AE, Dos Santos FV, Freitas KM, Pimenta LP, De Oliveira Andrade L, Marinho TA. Cellulose acetate nanofibers loaded with crude annatto extract: preparation characterization and in vivo evaluation for potential wound healing applications. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2021 Jan;118:111322. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2020.111322, PMID 33254960.

Wsoo MA, Shahir S, Mohd Bohari SP, Nayan NH, Razak SI. A review on the properties of electrospun cellulose acetate and its application in drug delivery systems: a new perspective. Carbohydr Res. 2020;491:107978. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2020.107978, PMID 32163784.

Al Jbour ND, Beg MD, Gimbun J, Alam AK. An overview of chitosan nanofibers and their applications in the drug delivery process. Curr Drug Deliv. 2019;16(4):272-94. doi: 10.2174/1567201816666190123121425, PMID 30674256.

Rubentheren V, Ward TA, Chee CY, Nair P. Physical and chemical reinforcement of chitosan film using nanocrystalline cellulose and tannic acid. Cellulose. 2015;22(4):2529-41. doi: 10.1007/s10570-015-0650-y.

Karimian A, Yousefi B, Sadeghi F, Feizi F, Najafzadehvarzi H, Parsian H. Synthesis of biocompatible nanocrystalline cellulose against folate receptors as a novel carrier for targeted delivery of doxorubicin. Chem Biol Interact. 2022 Jan 5;351:109731. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2021.109731, PMID 34728188.

Thomas P, Duolikun T, Rumjit NP, Moosavi S, Lai CW, Bin Johan MR. Comprehensive review on nanocellulose: recent developments challenges and future prospects. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2020;110:103884. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2020.103884, PMID 32957191.

Rana AK, Thakur VK. Impact of physic-chemical properties of nanocellulose on rheology of aqueous suspensions and its utility in multiple fields: a review. Vinyl Additive Technology. 2023;29(4):617-48. doi: 10.1002/vnl.22006.

Zhao X, Bhagia S, Gomez Maldonado D, Tang X, Wasti S, LU S. Bioinspired design toward nanocellulose based materials. Mater Today. 2023;66:409-30. doi: 10.1016/j.mattod.2023.04.010.

Samarasekara AM, Kumara SP, Madhusanka AJ, Amarasinghe DA, Karunanayake L. Study of thermal and mechanical properties of microcrystalline cellulose and nanocrystalline cellulose based thermoplastic material. In: Moratuwa Engineering Research Conference (MERCon); 2018. doi: 10.1109/MERCon.2018.8421906.

Flauzino Neto WP, Mariano M, Da Silva IS, Silverio HA, Putaux JL, Otaguro H. Mechanical properties of natural rubber nanocomposites reinforced with high aspect ratio cellulose nanocrystals isolated from soy hulls. Carbohydr Polym. 2016 Nov 20;153:143-52. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.07.073, PMID 27561481.

Cranston ED, Gray DG. Morphological and optical characterization of polyelectrolyte multilayers incorporating nanocrystalline cellulose. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7(9):2522-30. doi: 10.1021/bm0602886, PMID 16961313.

Gan PG, Sam ST, Abdullah MF, Omar MF. Thermal properties of nanocellulose reinforced composites: a review. J Appl Polym Sci. 2020;137(11):48544. doi: 10.1002/app.48544.

Omran AA, Mohammed AA, Sapuan SM, Ilyas RA, Asyraf MR, Rahimian Koloor SS. Micro and nanocellulose in polymer composite materials: a review. Polymers. 2021;13(2):231. doi: 10.3390/polym13020231, PMID 33440879.

Karimian A, Parsian H, Majidinia M, Rahimi M, Mir SM, Samadi Kafil H. Nanocrystalline cellulose: preparation physicochemical properties and applications in drug delivery systems. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019 Jul 15;133:850-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.04.117, PMID 31002901.

Julkapli NM, Bagheri S. Progress on nanocrystalline cellulose biocomposites. React Funct Polym. 2017 Mar;112:9-21. doi: 10.1016/j.reactfunctpolym.2016.12.013.

Habibi Y, Lucia LA, Rojas OJ. Cellulose nanocrystals: chemistry self-assembly and applications. Chem Rev. 2010;110(6):3479-500. doi: 10.1021/cr900339w, PMID 20201500.

Abdul Khalil HP, Davoudpour Y, Islam MN, Mustapha A, Sudesh K, Dungani R. Production and modification of nanofibrillated cellulose using various mechanical processes: a review. Carbohydr Polym. 2014 Jan;99:649-65. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.08.069, PMID 24274556.

Abitbol T, Rivkin A, Cao Y, Nevo Y, Abraham E, Ben Shalom T. Nanocellulose a tiny fiber with huge applications. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2016;39:76-88. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2016.01.002, PMID 26930621.

Chen Y, Zhang Y, Zhang H, Shen G, Zhang Z. Biocompatibility of nanocellulose based materials. J Nanomater. 2018.

Klemm D, Kramer F, Moritz S, Lindstrom T, Ankerfors M, Gray D. Nanocelluloses: a new family of nature based materials. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2011;50(24):5438-66. doi: 10.1002/anie.201001273, PMID 21598362.

De Souza Lima MM, Borsali R. Rodlike cellulose microcrystals: structure properties and applications. Macromol Rapid Commun. 2004;25(7):771-87. doi: 10.1002/marc.200300268.

Hubbe MA, Rojas OJ, Lucia LA, Sain M. Cellulosic nanocomposites. A review. Bio Resources. 2008;3(3):929-80. doi: 10.15376/biores.3.3.929-980.

Lin N, Huang J, Dufresne A. Preparation properties and applications of polysaccharide nanocrystals in advanced functional nanomaterials: a review. Nanoscale. 2012;4(11):3274-94. doi: 10.1039/c2nr30260h, PMID 22565323.

Capadona JR, Van Den Berg OV, Capadona LA, Schroeter M, Rowan SJ, Tyler DJ. A versatile approach for the processing of polymer nanocomposites with self-assembled nanofibre templates. Nat Nanotechnol. 2007;2(12):765-9. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.379, PMID 18654428.

Peresin MS, Habibi Y, Zoppe JO, Pawlak JJ, Rojas OJ. Nanofiber composites of polyvinyl alcohol and cellulose nanocrystals: manufacture and characterization. Biomacromolecules. 2010;11(3):674-81. doi: 10.1021/bm901254n, PMID 20088572.

Ghajarieha A, Habibib S, Talebianb A. Biomedical applications of nanofibers. Russ J Appl Chem. 2021 Oct 5;94(7):847-72. doi: 10.1134/S1070427221070016.

Wadhwa A, Mathura V, Lewis SA. Emerging novel nanopharmaceuticals for drug delivery. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2018;11(7):35-42. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2018.v11i7.25149.

Turbak AF, Snyder FW, Sandberg KR. Microfibrillated cellulose a new cellulose product: properties uses and commercial potential. Int J Appl Polym Sci. 1983;37(2).

Czaikoski A, Da Cunha RL, Menegalli FC. Rheological behavior of cellulose nanofibers from cassava peel obtained by combination of chemical and physical processes. Carbohydr Polym. 2020;248:116744. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116744, PMID 32919552.

Khawas P, Deka SC. Isolation and characterization of cellulose nanofibers from culinary banana peel using high-intensity ultrasonication combined with chemical treatment. Carbohydr Polym. 2016 Feb 10;137:608-16. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.11.020, PMID 26686170.

Okahisa Y, Furukawa Y, Ishimoto K, Narita C, Intharapichai K, Ohara H. Comparison of cellulose nanofiber properties produced from different parts of the oil palm tree. Carbohydr Polym. 2018;198:313-9. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.06.089, PMID 30093004.

Chirayil CJ, Joy J, Mathew L, Mozetic M, Koetz J, Thomas S. Isolation and characterization of cellulose nanofibrils from Helicteres isora plant. Ind Crops Prod. 2014;59:27-34. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2014.04.020.

Kouadri I, Satha H. Extraction and characterization of cellulose and cellulose nanofibers from Citrullus colocynthis seeds. Ind Crops Prod. 2018;124:787-96. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2018.08.051.

Ifuku S, Adachi M, Morimoto M, Saimoto H. Fabrication of cellulose nanofibers from parenchyma cells of pears and apples. Sen’i Gakkaishi. 2011;67(4):86-90. doi: 10.2115/fiber.67.86.

ReferencesFall AB, Lindstrom SB, Sundman O, Odberg L, Wagberg L. Colloidal stability of aqueous nanofibrillated cellulose dispersions. Langmuir. 2011;27(18):11332-8. doi: 10.1021/la201947x, PMID 21834530.

Paakko M, Ankerfors M, Kosonen H, Nykanen A, Ahola S, Osterberg M. Enzymatic hydrolysis combined with mechanical shearing and high-pressure homogenization for nanoscale cellulose fibrils and strong gels. Biomacromolecules. 2007;8(6):1934-41. doi: 10.1021/bm061215p, PMID 17474776.

Shibata I, Isogai A. Nitroxide mediated oxidation of cellulose using TEMPO derivatives: HPSEC and NMR analyses of the oxidized products. Cellulose. 2003;10(4):335-41. doi: 10.1023/A:1027330409470.

Ul Islam M, Khan S, Ullah MW, Park JK. Bacterial cellulose composites: synthetic strategies and multiple applications in biomedical and electro-conductive fields. Biotechnol J. 2015;10(12):1847-61. doi: 10.1002/biot.201500106, PMID 26395011.

Espinosa E, Rol F, Bras J, Rodriguez A. Production of lignocellulose nanofibers from wheat straw by different fibrillation methods. Comparison of its viability in cardboard recycling process. J Clean Prod. 2019 Dec 1;239:118083. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118083.

De Campos A, Correa AC, Cannella D, De M Teixeira EM, Marconcini JM, Dufresne A. Obtaining nanofibers from curaua and sugarcane bagasse fibers using enzymatic hydrolysis followed by sonication. Cellulose. 2013;20(3):1491-500. doi: 10.1007/s10570-013-9909-3.

Kumari P, Pathak G, Gupta R, Sharma D, Meena A. Cellulose nanofibers from lignocellulosic biomass of lemongrass using enzymatic hydrolysis: characterization and cytotoxicity assessment. Daru. 2019;27(2):683-93. doi: 10.1007/s40199-019-00303-1, PMID 31654377.

De Simone JM, Samulski ET, Rolland JP. Methods and apparatus for continuous liquid interface production with rotation. U.S. Patent 10589512B2; 2020.

Chang PR, Lin N, Huang J, Dufresne A. Polysaccharide based nanocrystals: chemistry and applications. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons; 2014.

Miguel SP, Figueira DR, Simoes D, Ribeiro MP, Coutinho P, Ferreira P. Electrospun polymeric nanofibres as wound dressings: a review. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2018 Sep 1;169:60-71. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2018.05.011, PMID 29747031.

Ambekar RS, Kandasubramanian B. Advancements in nanofibers for wound dressing: a review. Eur Polym J. 2019;117:304-36. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2019.05.020.

Ranby BG. Fibrous macromolecular systems cellulose and muscle the colloidal properties of cellulose micelles. Discuss Faraday Soc. 1951;11:158-64. doi: 10.1039/DF9511100158.

Basile R, Bergamonti L, Fernandez F, Graiff C, Haghighi A, Isca C. Bio inspired consolidants derived from crystalline nanocellulose for decayed wood. Carbohydr Polym. 2018 Dec 15;202:164-71. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.08.132, PMID 30286989.