Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 4, 2025, 1-9Review Article

THE SAFETY OF EXCIPIENTS AS A KEY FACTOR IN SUCCESSFUL DRUG DEVELOPMENT

NATALIA DEMINA, ELENA BAKHRUSHINA, MARIA ANUROVA, SALMA ABUELEZ*, IRINA ZUBAREVA, IVAN KRASNYUK

Department of Pharmaceutical Technology, A. P. Nelyubin Institute of Pharmacy, Sechenov First Moscow State University, Bolshaya Pirogovskaya Str., 2, p. 4-119435, Moscow, Russia

*Corresponding author: Salma Abuelez; *Email: abuelezsalma@gmail.com

Received: 05 Sep 2024, Revised and Accepted: 21 May 2025

ABSTRACT

Until recently, the safety of excipients had not received much attention, as they were considered pharmacologically indifferent and were included in medicinal products solely to facilitate production or to enhance ease of use. In recent years, excipients have come under greater scrutiny regarding their potential adverse effects on the body, which may have implications for patient safety during routine and long-term use. This article addresses certain aspects of the regulatory framework for excipients in the United States as well as in the countries of the European and Eurasian Unions. Various sources of information on the physicochemical and biological properties of pharmaceutical excipients are examined, along with examples of adverse effects associated with several widely used excipients. Descriptions of electronic databases containing information on excipients in the context of their application are provided, considering dosage, route of administration, dosage forms, and potential biological targets. A comparison of these databases is also provided.

Keywords: Excipients, Dosage forms, Excipient dosage, Excipient safety, Biological targets of excipients, Electronic databases

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i4.52587 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

To gather information, an analysis of scientific databases such as PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar was conducted. The search was performed using the following keywords: excipients adverse effects, excipients safety, excipient toxicity, excipients biological targets. The included articles cover the period from 2000 to 2024. The main selection criteria were the presence of information on adverse reactions and clinically or pharmacovigilance-confirmed data. To evaluate existing excipient databases, a search was conducted using Google using the following keywords: excipient databases and European excipient databases. The goal was to identify publicly available and specialized resources that provide comprehensive information on excipients, including their safety profiles and regulatory status.

Excipients are included in the formulations of almost all drugs, performing specific and very important tasks related to the quality of the drugs. The main groups of excipients and their functions are presented in table 1.

Table 1: Excipients functions in drug products

| Excipient function | Examples | Ref. |

| Creation of the actual dosage form. For several dosage forms, the use of such excipients is mandatory | Bases in soft dosage forms and suppositories Fillers in tablets Propellants in aerosols |

[1] |

| Ensuring pharmaceutical technology | Anti-adhesion excipients to prevent tablet mass from sticking to punches Lubricants to ensure the flowability of tablet mass |

[1] |

| Ensuring stability of pharmaceutical forms during storage and use | Preservatives to ensure microbiological purity Antioxidants to inhibit oxidative processes Plasticizers and Opacifiers for coatings on solid dosage forms Surfactants in liquid dosage forms |

[1] |

| Improvement of organoleptic characteristics | Dyes, sweeteners, flavorings, etc. | [1] |

| Modification of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs)release | Polymeric and high molecular weight excipients necessary for creating the desired structure of pharmaceutical forms (e. g., matrix, coatings on solid dosage forms, etc.) Absorption promoters that enhance the absorption of APIs |

According to the Biopharmaceutical (BP) Doctrine proposed in the second half of the 20th century, excipients are not entirely indifferent substances. The data in the table shows that while performing their functions in dosage forms, they can influence not only the manufacturing process and stability but also the release and absorption of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs), thereby determining the efficacy of the drug. The mass of excipients in a dosage form often significantly exceeds the mass of the APIs. As essential components of drugs, excipients must meet certain quality criteria and be standardized and stable.

Quality of excipients

The quality of many excipients is regulated by pharmacopoeias. Thus, the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) includes a whole section dedicated exclusively to excipients, the United States Pharmacopeia–National Formulary (USP-NF). European Pharmacopoeia, Japanese Pharmacopoeia and Pharmacopoeia of the Eurasian Economic Union contain monographs on several excipients. Specific pharmacopoeia monographs on excipients include standards of their physicochemical parameters and test methods. The quality of excipients not described by pharmacopoeias is generally regulated by the manufacturer's standards. However, modern requirements for the quality of pharmaceutical products no longer fit within the framework of pharmacopoeia standards alone.

Certain aspects of the regulatory framework for excipients

When submitting documents on drugs to regulating authorities for examination, information on excipients is a mandatory part of the dossier. In the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), in addition to certificates and specifications with justification and description of test methods, the following is required: justification for the use of excipients in the formulation, reports on the study of compatibility of excipients with APIs and for buffering agents, substances with antimicrobial activity-confirmation of the effective concentration [2]. For new excipients a complete description of production, properties, and control, as well as preclinical and clinical safety data is required.

In the United States, excipients do not have a regulatory status and cannot be used in pharmaceutical products without Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval. The pharmaceutical product dossier includes a section related to the manufacturing of inactive ingredients, covering key technical details. The submission of a separate Drug Master File (DMF) for excipients is not required by law. The approval of a pharmaceutical product's formulation considers the excipient dosage, which, without strong justification, cannot exceed the dosage specified in the database maintained by the FDA since 1987. This database contains information on each excipient included in the formulations of approved pharmaceutical products. In drug development, priority is given to excipients listed in this database [3].

In the EU, manufacturers are responsible for the safety of their products and must ensure that these undergo a scientific safety assessment by experts before being sold [4]. As in the United States, the pharmaceutical product dossier includes an excipient data file in the ICH Common Technical Document (CTD) format. This file typically contains specifications, test methods for raw materials, intermediates, and the final excipient, safety data, packaging description, and labeling information. Manufacturers and suppliers of excipients are also advised to monitor safety-related aspects such as raw material origin, viral safety, degradation products, residual catalysts (heavy metals), preservatives, and processing aids [5].

There is no official list of excipients approved across the European Union (EU). During pharmaceutical development, priority is given to excipients whose quality is described in pharmacopoeias. However, since pharmacopoeias do not provide information on the safety of substances or their suitability for specific routes of administration, pharmaceutical developers must refer to scientific literature. In some European Union (EU) member states, national reference collections list approved excipients and their applications. For example, in France, this is the Dictionnaire Vidal; in Germany, Die Rote Liste; and in the UK, The Electronic Medicines Compendium (EMC). European manufacturers are also recommended to use the FDA Inactive Ingredient Database and the Handbook of Pharmaceutical Excipients as reference guides [1].

In Japan, the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare prioritizes the use of ingredients described in the Japanese Pharmacopoeia and in a reference book known as the Japanese Pharmaceutical Excipients Dictionary. These manuscripts provide information on the various excipients previously used in drugs in the country, describing their characteristics and maximum doses for different routes of administration [6].

Development and harmonization of standards, provision of useful information about new excipients, development, implementation and manufacturing conditions, transfer of experience and recommendations on excipients are the areas of activity of the International Pharmaceutical Excipients Council (IPEC).

IPEC includes manufacturers, distributors, end-users of excipients and pharmaceutical products, and regulatory authorities. Regional associations of pharmaceutical excipients manufacturers are located in North and South America, Europe, Japan, China and India. IPEC includes Quality and Regulatory Committee, Good Distribution Practice Committee, and Events Committee [7].

The strict quality requirements for excipients make it a challenge to manufacture them in accordance with Good Manufacturing Practice GMP. IPEC has developed Guidelines regarding the quality, standardization, stability, manufacturing, and distribution of excipients. The Guidelines consider physical, chemical, microbiological properties, composition, and stability as criteria for the evaluation of excipients [8-14].

The Guidelines are intended to be used on a voluntary basis and are not regulatory requirements. They are developed to achieve a modern level of quality assurance of excipients and to demonstrate the best international practices to provide manufacturers with up-to-date directions on this topic.

As already mentioned, neither pharmacopoeias nor IPEC recommendations provide information on the biological properties of excipients, their safe dosages, permissible routes of drug administration, and dosage forms in which formulations a particular excipient can be used. Pharmacopoeias and regulatory documents do not provide data on how excipients interact with other excipients or Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs).

These aspects of excipients become particularly relevant for researchers and professionals involved in pharmaceutical development and drug manufacturing. They are also important for clinicians and consumers, as there is an increasing number of publications in scientific literature reporting adverse events caused by excipients. Since drug products typically contain multiple excipients, there is concern that their combined presence may increase undesirable effects in sensitive patients.

Until recently, the safety issues of excipients have not been paid attention to, as they were considered pharmacologically indifferent and were included in medicinal products only to facilitate manufacturing or to enhance the convenience of use.

Modern drug products are often not simple mixtures of ingredients. They are complex products that have been technologically processed to impart specific properties to the drug. Their structure varies and may represent an engineered design combining several ingredients, such as therapeutic systems, Nano drugs, modified-release forms, and so on. Inactive components of the dosage form may interact with each other, change their properties during the production of dosage forms under high temperatures, crystallization processes, hydrolysis, oxidation, and improper storage conditions and as a result have effects on consumers that will increase with prolonged administration in large quantities [6].

Therefore, excipients have received more attention in recent years in the context of studying their adverse effects on the body, which may have implications for patient safety during routine and long-term use. The causes of adverse effects from excipients include the toxic effect of the excipient itself, improper substitution with a cheaper substance, patient intolerance, and allergic reactions.

Examples of adverse effects of some excipients

Classic examples of excipients with inherent toxic effects include preservatives and some antioxidants.

The antimicrobial preservative thimerosal isa mercury compound registered in 1929 and marketed under the trade name Merthiolate [15, 16]. It has toxic effects when ingested and in contact with the skin. Despite being removed from children's vaccines in the United States in 1999, it is still used in some countries, including the U. S., in the industrial production of influenza vaccines for adults, and in some developing countries, it is even used in vaccines for children [17-19]. Recent studies have shown that thimerosal and ethylmercury have an affinity for the dopamine D3 receptor. Rats receiving thimerosal postnatally had impaired motor functions, increased anxiety in the open-field test, and changes in social behavior, i. e., all side effects that are well known for dopamine receptor ligands were demonstrated [20].

Butylparaben, or butyl p-hydroxybenzoate, a preservative widely used in cosmetic and pharmaceutical products, has been known as a pharmaceutical ingredient since 1924. It may decrease sperm function and cause endocrine disruption with undesirable effects on reproductive function [21].

Propyl gallate, a propyl ester of gallic acid, is used as an antioxidant in food and pharmaceutical industries. It hasan antiproliferative effect on β-and T-cells, smooth muscle cells of coronary arteries, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts. Propyl gallate has cellular activity associated with inflammation and immunosuppressant activity and is an estrogen antagonist [22].

Glycerin is a classic example of an excipient that, in some cases, is replaced by a cheaper "analog"—Diethylene Glycol (DEG). DEG is a colorless, sweet-tasting, odorless liquid used as a cheap filler in brake fluids, paints, and household chemicals. In 1937, the poisoning of children with a sulfanilamide elixir containing DEG as a solvent resulted in the death of 105 patients. This case received widespread public attention and as a result, The United States Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act was passed. Unfortunately, the use of DEG in pediatric formulations did not stop.

Between 1992 and 2022, poisoning incidents occurred in Nigeria, Bangladesh, Indonesia, the Marshall Islands, Pakistan, Panama, Gambia, India (twice), Uzbekistan, and Cameroon, following the use of cough syrups and other medications containing cheap DEG instead of glycerin. It is now well known that diethylene glycol is nephrotoxic and can lead to Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome (MODS), particularly in children [23]. Due to its physical properties, it can serve as a cheap substitute for propylene glycol.

Allergic reactions to excipients are real and can have serious consequences for patient safety. Information on such reactions is extremely important for clinicians and patients themselves and can severely limit the choice of drugs for appropriate drug therapy.

In [18], a review of scientific publications is presented, describing allergic reactions in patients to excipients after the administration of drugs containing Polyoxyethylene (PEG) and its derivatives: PEG-sorbitans (polysorbates), PEG-castor oil (e. g., Cremophor), and PEG copolymers with propylene glycol (poloxamers), as well as carboxymethylcellulose (CMC), gelatin, and Propylene Glycol (PG). It has been shown that these excipients can cause an immediate hypersensitivity reaction-anaphylactic reaction. Although the incidence of such reactions to excipients is extremely low, it raises serious concerns for patients due to the high risk associated with their occurrence.

Polyoxyethylene (PEG) is a water-soluble nonionic polymer also known as Macrogol. It is widely used in pharmaceuticals as a component of bases for suppositories, soft dosage forms, and in the formulations of PEGylated nanomedicines [24]. PEG is present in many products. There have been reports of anaphylactic reactions to PEG 3350, PEG 4000, and PEG 6000. It has been shown that antibody avidity increases with the molecular weight of PEG. For a patient, there may be a lower molecular weight limit below which they do not react to PEG; for example, a skin test for PEG 300 may show a negative result, while PEG with a higher molecular weight triggers an anaphylactic reaction. Therefore, the use of medications containing PEG with a higher molecular weight is contraindicated in such patients. PEGylated liposomes may be relevant allergens and a contraindication for the use of this class of drugs in patients allergic to PEG. Cases of anaphylaxis have been reported with the use of PEGylated perflutren [25].

Polysorbates (PS) are nonionic surfactants that are esters of fatty acids (hydrophobic part) and polyoxyethylated sorbitan (hydrophilic part). They are widely used in the food, cosmetic, and pharmaceutical industries. Structurally similar to PEG, they can cause anaphylactic reactions, inflammation, and urticaria at the injection site. Despite their stabilizing effect on APIs, polysorbates themselves are susceptible to oxidative degradation, leading to the formation of residual peroxides and other active oxidation forms [26]. Polysorbates also act as photoenhancers, which can lead to photooxidation, meaning they are subject to degradation due to the combined effects of light and oxygen [27, 28].

During the pandemic, Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines containing SARS-CoV-2 mRNA received emergency use authorization. Since the nature of cross-reactivity among excipient allergens remains largely unknown, the presence of PS80 and PEG-2000 in the lipid nanoparticle, which acts as a carrier system for the SARS-CoV-2 spike, may have been one of the reasons for hypersensitivity reactions in patients. Moreover, the mRNA of the protein itself may also act as an allergen [29].

Colliphor, also known as Cremophor, is polyoxyethylated castor oil, used as a surfactant in dosage forms with poorly soluble APIs. It can cause severe immediate anaphylactic reactions, potentially hyperlipidemia, neurological complications, and encephalopathy [29-31].

Carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) is a semi-synthetic water-soluble polymer used to regulate viscosity in liquid and soft pharmaceutical formulations, as well as in food products. It has been associated with immediate anaphylaxis as an allergen in barium sulfate suspensions (a contrast medium for X-rays) and topical gels [29]. It can also trigger anaphylaxis when consuming ice cream [32].

Propylene glycol, structurally different from PEG, is used as an emulsifier and emollient in cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, and food products. It also serves as a non-aqueous solvent in liquid pharmaceutical formulations, including injectable solutions, and is included in intravenous nitroglycerin solutions in many countries (e. g., the UK, Netherlands, USA, France, etc.). When taken orally in low and moderate concentrations used in pharmaceuticals, it is safe for human health. However, when administered intravenously, it can cause Central Nervous System (CNS) depression, hypotension, bradycardia, ECG changes, hemolysis, and seizures [33]. It is often found in formulations that cause delayed hypersensitivity reactions. For this reason, it was named "Allergen of the Year" in 2018 by the American Contact Dermatitis Society [18].

Additionally, some examples of adverse effects of commonly used excipients in pharmaceuticals are provided in table 2.

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has compiled a list of 115 excipients with known biological effects, along with patient information that must be included in the package leaflet for pharmaceutical products in the EU. Warning labels are provided for pharmaceutical products with different excipient dosages, routes of administration and for patients of various age groups. For pediatric pharmaceutical products, age categories are specified as follows: under 2 y, 2 to 12 y, 12 to 18 y, and over 18 y, if necessary. The information is available in 26 European languages and is periodically updated. Unfortunately, this list covers only a small part of the current excipient nomenclature [37].

The EMA also provides a list of allergens and fragrances used in the EU, the names of which must be included in the labeling of cosmetic and cleaning products. This list includes many essential oils, as well as anisyl alcohol, benzyl alcohol, benzyl benzoate, benzyl cinnamate, benzyl salicylate, and citral, which are used in pharmaceutical products as preservatives and flavoring agents [37].

In pediatric dosage forms, the safety of excipients is of particular importance. Due to the specific metabolism of children and the age-related heterogeneity of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic parameters, some excipients that are acceptable in adult pharmaceutical products may not be suitable for use in pediatrics. In the absence of pediatric-specific dosage forms, a pediatrician prescribes medication for a child by dividing the adult dosage based on the child's age and weight. However, certain excipients used in adult pharmaceutical products (such as benzyl alcohol, ethanol, propylene glycol, and parabens) cannot be used in the treatment of children, even at the lowest concentrations, as they have toxicological effects on a child's body. Some examples of excipients that cause adverse reactions in a child's body are provided in table 3.

It should be noted that in the USA, EU countries, and EAEU countries, guidelines have been adopted regarding the development of pediatric medicinal products [42]. A more detailed discussion of the issue of creating medicines for childrenas well as for the elderly deserves considerable attention and could be presented in a separate publication.

Biological activity of excipients

Not all approved excipients have obvious toxicity or cause appreciable side effects at the dosages used in dosage form. However, this does not mean that they are completely indifferent to the organism. Approved excipients with no obvious physiologic effects may have specific activity against molecular targets, impairing their function and the function of the cellular networks in which they are involved.

Various popular artificial intelligence methods are used to assess the predictive potential of excipient activity and drug safety [43]. The authors of the study [29] applied the chemoinformatics Similarity Ensemble Approach (SEA) [44, 45], which is based on the study of the interaction of excipients with the target according to the target-ligand principle.

More than 600 molecular excipients were computer screened and a list of potential protein targets was compiled for each of them based on its value in SEA. Next, commonly used excipients were experimentally tested against clinical toxicity targets. The authors studied the interaction of 73 commonly used excipients with 28 targets related to clinical drug safety, including biologically relevant targets involved in drug pharmacokinetics. Among the investigated excipients were palmitic acid, oleic acid, propylparaben, methylene blue, sodium lauryl sulfate, tartrazine (FD and C Yellow No. 5), aspartame, cetylpyridinium chloride, etc. It was shown that 38 excipients are active against one or more targets. In total, 134 activities were identified among the excipients studied, specifically; butylparaben showed activity related to inflammatory processes. Propyl gallate was found to potentially cause sinus congestion and pain, and to exhibit immunomodulatory and inflammatory cellular activity.

A key observation from this study is that many “inactive ingredients” commonly found in pharmaceuticals have direct activity against biologically relevant enzymes, receptors, ion channels and transporters under in vitro conditions. Consequently, excipients, which are often present in large quantities in drug formulations, can have significant effects on medically relevant targets. Therefore, excipients that demonstrate biological activity in vitro and reach significant systemic concentrations upon administration require more detailed study for a comprehensive assessment of their safety."

Meanwhile, regulatory authorities allow substitution of approved excipients in drug formulations as long as they do not affect the pharmacokinetics of APIs. However, such substitution may affect the activity of the drug, as different excipients are expected to have different target activities, affecting the overall side effects of the drug.

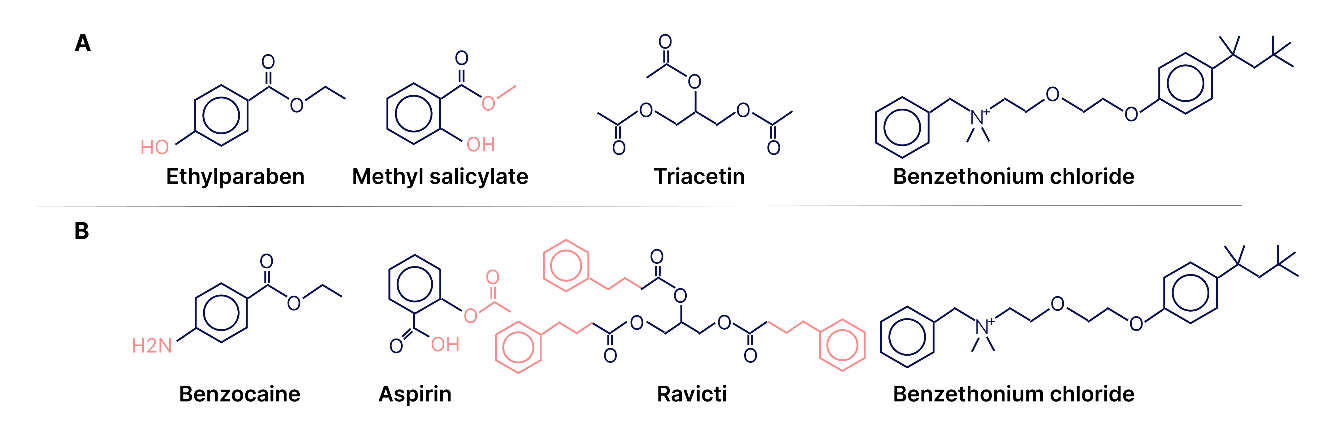

The motivation for testing the biological activities of excipients may be the similarity of the structures of some APIs and excipients. This can be seen in fig. 1, where the first row shows the formulas of commonly used excipients, and the second row shows the formulas of approved APIs. Some excipients are also active substances, such as the antiseptic benzethonium chloride.

Table 2: Examples of adverse effects of some excipients

| Excipients by their functions | Additional function | Adverse effects | Ref. |

| Preservatives | [6, 26, 35] | ||

| Benzyl alcohol | Hypersensitivity reactions, effects on the respiratory system In newborns: respiratory distress syndrome, metabolic acidosis, hemorrhages, neurological disorders, and death due to immature metabolism |

||

| Benzalkonium chloride | surfactant | Bronchospasm when used in combination with asthma medications. Ear damage | |

| Chlorhexidine (all salts) | Biocides | Hypersensitivity reactions, conjunctival irritation and corneal damage at high concentrations | |

| Parabens | Reports of estrogenic effects, especially propylparaben. Also, hypersensitivity reactions and anemia in newborns | ||

| Solvents | [6, 26, 35] | ||

| Ethanol | co-solvent | Intoxication | |

| Propylene glycol | CNS effects, lactoacidosis, especially in children under 4 y of age | ||

| Sweeteners | [26] | ||

| Saccharin | Hypersensitivity and photosensitization | ||

| Glucose and sucrose | Tooth decay | ||

| Aspartame | Breaks down into phenylalanine, asparagic acid and methanol. Contraindicated in patients with phenylketonuria, may cause headache and seizures | ||

| Menthol | Inhalation in large quantities causes ataxia and CNS depression. Hypersensitivity reactions have been reported | ||

| Antioxidants | [6, 26] | ||

| Sodium and potassium bisulfites, sodium and potassium metabisulfites, sodium sulfites, and sulfur dioxide | Bronchospasm, itching, urticaria, chest pain, angioedema, and arterial hypotension, sometimes leading to unconsciousness, are characteristics for hypersensitivity reactions. These reactions usually occur in patients who have a history of asthma attacks |

||

| Sodium metabisulfite | Wheezing and chest tightness in children with asthma | ||

| Fillers | [34, 36] | ||

| Lactose | diluent | In lactose intolerant individuals, cramps, diarrhea and flatulence | |

| Mannitol | Shortens the transit time through the small intestine compared to sucrose. Compared to sucrose, which has no such effect. |

||

| PEG 400 (polyethylene glycol) | stimulates peristalsis of the gastrointestinal tract and accelerates passage through the small intestine | ||

| Sorbitol | In sensitive patients may decrease bioavailability of APIs with high permeability |

||

| Gelatin in vaccines, rectal suppositories, and dietary supplements | Thickener, binder in solid dosage forms | Possible anaphylaxis and seizures in patients with epilepsy | |

| Dyes | [29] | ||

| Titanium dioxide | Opacifier | Nanoparticles lead to changes in mitochondrial morphologyand decreased mitochondrial membrane potential | |

| Dyes (e. g., azo dyes) | Sensitivity reactions. Some reports of hyperactivity in children | ||

| Iron oxide | Increases the predisposition to seizures in patients with epilepsy | ||

| Other | [26, 36] | ||

| Shellac | Coating material | Seizures in patients with epilepsy | |

| Silicon dioxide | Stabilizer, gelling agent, adsorbent | Possible anaphylaxis in patients with epilepsy | |

| Hydrogenated castor oil derivatives | Solubilizer, surfactant | Anaphylaxis |

Table 3: Examples of the effects of certain excipients on a child's body

| Name of excipient | Adverse events in pediatrics | Ref. |

| Mannitol | It may cause hypersensitivity reactions and anaphylactic reactions after intravenous infusion of 10% or 20% (w/v) solutions. When taken orally, it can create high osmotic pressure in the intestine, leading to severe diarrhea, which in turn reduces transit time in the small intestine and decreases the absorption of certain medications | [18] |

| Ethanol | It has very high permeability to the Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB). Side effects are observed at a dose of 100 mg/dL, including hyperglycemia and acidosis. High concentrations lead to coma, respiratory depression, cardiovascular collapse, and hyperglycemic seizures | [36] |

| Glycerin | Due to its strong osmotic properties, it contributes to the development of serious side effects: diarrhea, electrolyte imbalances, headache, and stomach disorders | [39] |

| Sorbitol | It is not absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract. Side effects may include: a laxative effect at high concentrations, significantly reducing the absorption of other medications, causing abdominal pain, bloating, and osmotic diarrhea. In severe cases, it can lead to liver damage. Sorbitol is metabolized to fructose. Therefore, it is contraindicated in pediatric patients with hereditary fructose intolerance | [38, 39] |

| Aspartame | Its sweetening ability is more than 150-200 times greater than sucrose. It contains phenylalanine, which is contraindicated in patients with phenylketonuria and epileptogenic disorders. Side effects may include reduced insulin sensitivity, neurological disturbances (neurotoxicity, headache, panic attacks), hypersensitivity reactions (vascular and granulomatous panniculitis), and cross-reactivity with sulfonamides | [39-41] |

| Saccharin | Its sweetening ability is approximately 300 times greater than sucrose. It has carcinogenic effects in pediatric groups (bladder cancer in children often occurs when large amounts of saccharin are consumed). It can cause insomnia, irritability, and cross-sensitivity to sulfonamide medications | [39-41] |

| Dyes | Azodyes: cross-sensitivity to acetylsalicylic acid, sodium benzoate, and indomethacin. For this reason, azodyes should not be used in pediatrics. Contact dermatitis is common with quinoline dyes. Triphenylmethane dyes can cause bronchospasm, skin rashes, erythema, and anaphylaxis. Xanthine dyes can also cause photosensitivity and carcinogenicity in children | [39-41] |

| Propylene glycol | It is rapidly absorbed through the gastrointestinal tract and damaged skin. It may accelerate irreversible deafness in premature infants (±5.2%). Cases of biochemical disturbances have been reported, including hyperosmolality, lactic acidosis, and increased levels of creatinine and bilirubin, after taking 3g/day of propylene glycol for 5 consecutive days. Clinical symptoms then appeared, including seizures and bradycardia | [39-41] |

| Parabens (methtyl, ethyl-, propyl-, butyl-) | They affect the binding of bilirubin to albumin (risk of serious complications in newborns with hyperbilirubinemia). They may cause cross-sensitivity reactions in patients allergic to aspirin. Paraben-containing medications should be contraindicated in newborns with jaundice | [39-41] |

Fig. 1: Similarity of structures of some APIs and excipients, A – excipients, B-drugs [29]

Data on the safety of excipients found in scientific publications are scattered and not systematized, often focusing on a small group of excipients within the context of drug products for specific diseases. The extensive nomenclature of modern excipients requires a systematic organization of their characteristics.

One of the most authoritative, world-renowned publications containing extensive information on pharmaceutical excipients is the Handbook of Pharmaceutical Excipients [5], which has undergone several editions. The authors of the 9th edition (2020) were more than 160 scientists from different countries who are experts in the manufacturing, analysis, and use of excipients. The handbook contains more than 420 monographs on excipients, which contain not only a description of the functions of excipients in drug formulations, but also: information from the pharmacopoeias of the UK, Europe, Japan, and the USA; chemical names and structure, Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registration numbers, empirical formulas, molecular weight; data on incompatibility, safety, stability, storage; biological sections on excipients used in pediatric, injectable, oral solid, and inhalation drug products.

Monographs are cross-referenced and many include infrared, Raman and Near-infrared Spectroscopy (NIR).

Databases on excipients

Electronic databases on excipients have become highly valuable for researchers, manufacturers, and regulatory authorities, offering extensive information on a wide range of excipients.

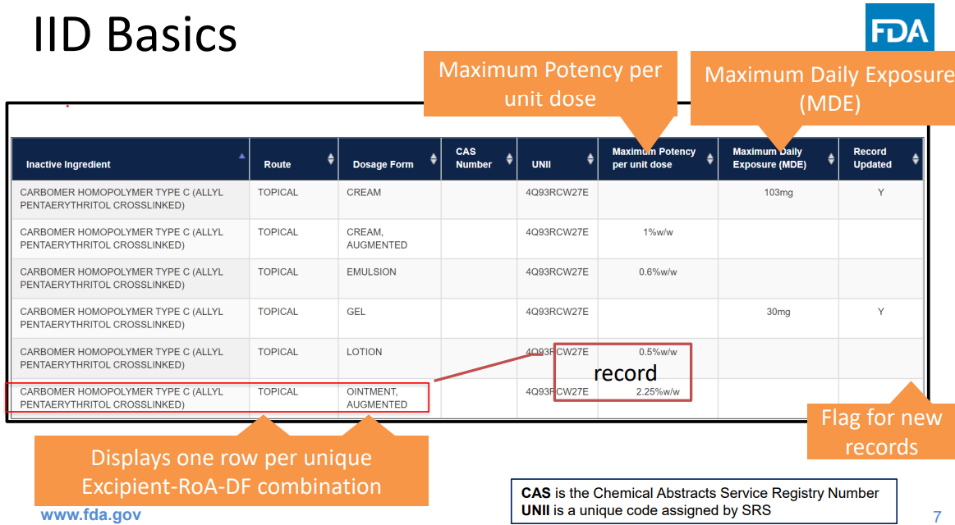

In 1987, the FDA published a paper-based Guide to Inactive Ingredients in Drug Formulations. The aim of the guide was to systematize and provide additional information on excipients. Since 2003, this information has been available online in the FDA's database, which now includes data on all excipients used in approved drug products. This database provides information on the dosage forms and routes of administration for each excipient, as well as maximum single and daily doses within these contexts [46, 47]. The FDA excipient database is continuously updated, allowing researchers specializing in pharmaceutical development to determine the applicability of specific excipients for dosage forms and routes of administration. The dosage information provided is considered safe, as it is based on formulations of drug products already approved by the FDA, which have undergone toxicity studies, preclinical and clinical trials. According to the authors, this information indicates the safety of the excipients under the specified conditions of use.

The provided information on excipient dosages is used in the evaluation of new drug products. If these dosages are exceeded, the FDA may request justification and additional safety data for the drug, including pharmacokinetic profiles. A screenshot of the webpage is shown in fig. 2.

Fig. 2: FDA inactive ingredient database web page [48]

However, this database does not provide information on the compatibility of individual excipients and their mixtures with other ingredients of dosage forms, including APIs [46].

The European Pediatric Formulation Initiative (EuPFI), in collaboration with the United States Pediatric Formulation Initiative (USPFI), has developed the STEP database, which stands for Safety and Toxicity of Excipients for Pediatrics. The STEP database is a free resource that contains information on the safety and toxicity of excipients, manually extracted from selected information sources [49, 50]. The aim of this project is to provide important information on excipients for practical use and scientific research. STEP offers public access to a database of information on the safety and toxicity of excipients for pharmaceutical industry scientists, healthcare professionals, and regulatory authorities, becoming a practical tool for all scientific communities involved in pediatric drug development.

For each excipient, the STEP resource provides general information, including chemical name, CAS registration number, synonyms and functions, and in vitro characteristics. Clinical data includes type of study, age category, route of administration/application site, and effect on an organ/system. Preclinical data contains all information on animal toxicity with references to original publications.

STEP database allows you to search for characteristics by the name of the excipient and, conversely, to select suitable excipients according to the target characteristics of the drug to be developed (route of administration, dosage form, age category, etc.). Based on the target quality profile, having set the search criteria for the product to be developed, on the page “Search results” the resource provides information about the corresponding excipient, its chemical name, CAS registration number, its pharmacopoeial, regulatory status, synonyms, acceptable daily dosage.

Thus, the STEP database, in which toxicity and safety information can be searched in both directions, makes it highly convenient to find the information you need. The pilot version of the STEP database was launched in 2014 and is currently being continuously updated.

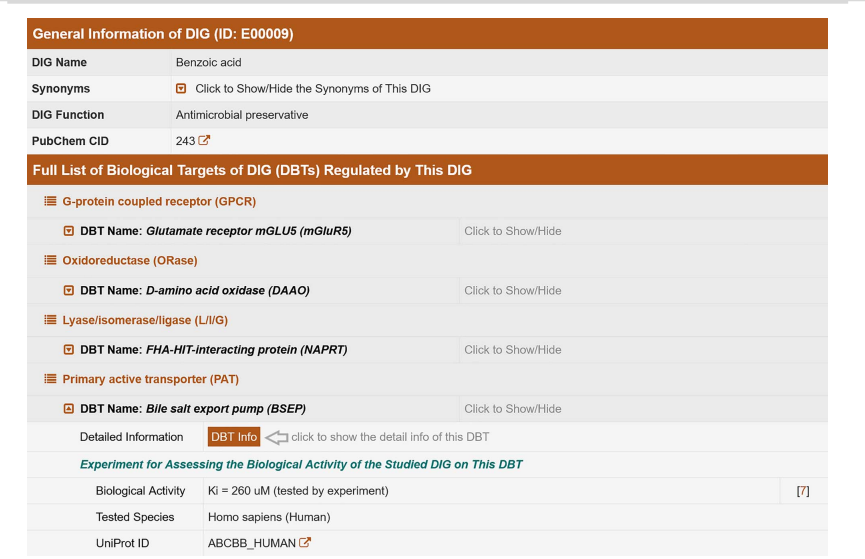

To systematize and summarize scientific data from various sources, researchers at Zhejiang University (China) developed a database in 2022 called "ACDINA: biological activities of drug inactive ingredients" [, 52]. This database was created by analyzing information from publications on more than 2,000 FDA-approved drug products, reviewing 23,949 dosage forms. The biological activity of these drugs and their corresponding biological targets were studied based on literature sources and open databases (including UniProt, PubChem, NCBI Gene, ChEMBL, etc.) [-]. A comprehensive set of artificial intelligence methods (machine learning, ML) was employed to process the information for predictive assessment of the biological activity of excipients, with the results implemented in Python (version 3.7.11). This allowedto create a database that describes the largest number of excipients, APIs, and dosage forms, providing comprehensive data on their biological activity. All users can freely access ACDINA. A screenshot of the webpage for the excipient benzoic acid is shown in fig. 3.

The top of the table provides general information about benzoic acid, while the complete list of Biological Targets (DBT) regulated by it is shown below. All biological targets are classified according to their biochemical families. Data on the biological activity of excipients (highlighted in color) and a hyperlink to additional information in other available databases are provided below the text. By clicking the "DBT Information" button, you will be redirected to a new page containing data on synonyms of the excipient, biochemical family, tested organism, gene name, and more [50]. This format is used for information on APIs and drugs.

Top of Form

Bottom of Form

The information in the databases on excipients varies in nature and scope. А brief comparative description is provided in table 4.

Databases on excipients have enormous practical value in scientific research, for developers and manufacturers, clinicians, and regulatory authorities. It is important to continuously update them with new information that meets the current needs of professional communities in the field of pharmaceutical products. This includes data on the compatibility of individual excipients and their mixtures with other ingredients of dosage forms, including Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs), as well as information on possible impurities and technological additives that need to be monitored, the stability of ingredients during processing, and more.

Limitations and future directions

This comprehensive review brings together currently available data on pharmaceutical excipient safety, offering a clear and complete analysis of existing databases-making it an especially useful resource for researchers and developers. While current tools help assess risks and choose appropriate excipients, there are still major gaps. Many excipients haven’t been thoroughly studied for long-term use, effects in children, or interactions with active drug ingredients. Databases also often miss key details on how excipients behave when combined. While these resources facilitate risk assessment and rational excipient selection, significant limitations persist in the field. Many excipients still lack comprehensive toxicological studies, especially concerning long-term use, pediatric exposure, or interactions with active ingredients. Additionally, existing databases often omit critical compatibility data between excipients and APIs. These identified gaps not only highlight the importance of this review's all-encompassing approach but also underscore the pressing need for standardized testing protocols and expanded regulatory requirements to ensure excipient safety in evolving drug formulations.

Fig. 3: Web page describing a drug called benzoic acid [50]

Table 4: Comparative aspects of excipient databases

| Database information | Application | Ref. |

| FDA inactive ingredient database | [48] | |

| Contains information about all excipients included in the formulations of medicinal products approved by the FDA. For each excipient, the dosage form and route of administration are provided, as well as the maximum single and daily doses in these medicinal products | It allows determining the suitability of a specific excipient for a given dosage form and route of administration. The excipient dosages listed in the database are considered safe based on the fact that medicinal products containing them have been approved, serving as guidelines for the development of new products and in the evaluation of new medicinal products. The dataset does not contain information on the biological activity of substances, including adverse effects or potential interactions with other ingredients in medicinal products | |

STEP safety and toxicity of excipients for pediatrics Developed by the European Pediatric Formulation Initiative (EuPFI) in collaboration with the United States Pediatric Formulation Initiative (USPFI) |

[49, 50] | |

| For each excipient, the following information is provided: general information, including chemical name, CAS registration number, pharmacopoeial and regulatory status, synonyms, acceptable daily dosage, functions, and in vitro characteristics. Clinical data include type of study, age group, route of administration/application, and effect on organ/system. Preclinical data includes all information on animal toxicity with references to original publications | It allows searching for physicochemical and clinical characteristics of an excipient by name and vice versa, as well as selecting suitable excipients based on the target properties of the drug being developed in the context of route of administration, dosage form, age group, etc., making it very convenient for finding the needed information. The dataset information is intended for pediatric drug products | |

ACDINA biological activities of drug inactive ingredients Zhejiang University (China) |

[51, 52] | |

| It describes not only excipients but also APIs and drug products (2000 FDA-approved drug products). It contains general information about the substance a complete list of biological targets regulated by it. All biological targets are classified by their biochemical families. Data on the biological activity of the substance are provided, along with hyperlinks to additional information in other available databases. It includes data on substance synonyms, biochemical families, the tested organism, and gene names |

It provides comprehensive data on the biological activity of substances, manually gathered from open scientific information sources. Data on the predictive activity of substances on biological targets is obtained from scientific publications using artificial intelligence technology. The data set allows for searching the most complete, diverse, and up-to-date information for drug developers and clinicians |

CONCLUSION

Sources of information on physicochemical parameters of pharmaceutical excipients include pharmacopoeias and manufacturers' quality standards, which do not contain information on acceptable routes of administration and dosage forms for each specific excipient. In recent years, due to the emergence of publications on the adverse effects on the body of several excipients, information on the biological activity of excipients is widely demanded both in clinical studies and practice and in the pharmaceutical industry. To systematize and generalize scientific data from different sources to deliver important information about excipients for practical use and in scientific research, electronic databases have been created. These databases provide the consumer with information about excipients in the context of their use, including adverse effects and \or biological targets with which excipients can interact.

FUNDING

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

ND designed the article and drafted the manuscript. EB and MA researched and analyzed relevant information. SA assisted in data visualization and interpretation. IZ and IK supervised the research and provided critical guidance. All authors have reviewed, edited, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

Sheskey PJ, Hancock BC, Moss GP, Goldfarb DJ, editors. Handbook of pharmaceutical excipients. 9th ed. London: Pharmaceutical Press; 2020. p. 1400.

Eurasian Economic Commission. Place of publication unknown; 2018 Jul 20. Available from: https://docs.eurasianeconomiccommission.eaeunion.org/upload/iblock/48f/168lf54epet2i8rd7bjkxdr5ousxsx2l/cncd_20072018_doc.pdf. [Last accessed on 10 Sep 2024].

Mannion R. Complex generics and regulatory challenges. Silver spring (MD): center for research on complex generics; 2022 Dec 6. Available from: https://www.complexgenerics.org/wp-content/uploads/crcg/prsnt-mannion20221206-crcg-62.pdf. [Last accessed on 18 Sep 2024].

Radhika G, Sharvani A, Hemanth Eswar Teja Y, Prasanthi D. Comprehensive regulations for drug and cosmetics in European Union. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2025;17(2):26-32.

Goupil R, Tsuyuki RT, Santesso N, Terenzi KA, Habert J, Cheng G. Hypertension Canada guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of hypertension in adults in primary care. CMAJ. 2025;197(20):E549-64. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.241770, PMID 40419299.

Pharmacentral. Place of publication unknown: Pharmacentral. Pharmaceutical excipients safety: it’s not only about toxicology. Available from: https://pharmacentral.com/learning-hub/technical-guides/pharmaceutical-excipients-safety-its-not-only-about-toxicology. [Last accessed on 01 Oct 2024].

Europe IP. Brussels (BE): Available from: https://www.ipec-europe.orginternationalpharmaceuticalexcipientscouncileurope. [Last accessed on 18 Sep 2024].

International Pharmaceutical Excipients Council. IPEC excipient stability guide for pharmaceutical excipients. In: Brussels, Belgium: International Pharmaceutical Excipients Council; 2022. Available from: https://www.ipec-europe.org/guidelines.html?y=2022. [Last accessed on 08 Sep 2024].

International Pharmaceutical Excipients Council. The IPEC excipient information package sustainability chapter. In: Brussels, Belgium: International Pharmaceutical Excipients Council; 2023. Available from: https://www.ipec-europe.org/guidelines.html. [Last accessed on 08 Sep 2024].

International Pharmaceutical Excipients Council. IPEC significant change guide. In: Brussels, Belgium: International Pharmaceutical Excipients Council; 2023. Available from: https://www.ipec-europe.org/guidelines.html.

International Pharmaceutical Excipients Council. The IPEC good distribution practices audit guide for pharmaceutical excipients. In: Brussels, Belgium: International Pharmaceutical Excipients Council; 2021. Available from: https://www.ipec-europe.org/guidelines.html.

International Pharmaceutical Excipients Council. The IPEC certificate of analysis guide for pharmaceutical excipients. In: Brussels, Belgium: International Pharmaceutical Excipients Council; 2024. Available from: https://www.ipec-europe.org/guidelines.html. [Last accessed on 08 Sep 2024].

International Pharmaceutical Excipients Council. The IPEC qualification of excipients for use in pharmaceuticals. In: Brussels, Belgium: International Pharmaceutical Excipients Council; 2020. Available from: https://www.ipec-europe.org/guidelines.html. [Last accessed 08 Sep 2024].

International Pharmaceutical Excipients Council. IPEC-PQG good manufacturing practices guide. In: Brussels, Belgium: International Pharmaceutical Excipients Council; 2022. Available from: https://www.ipec-europe.org/guidelines.html. [Last accessed on 08 Sep 2024].

MedlinePlus. Phosphorus: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. Bethesda: United States National Library of Medicine. Available from: https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/00267814.html. [Last accessed on 03 Sep 2024].

Spectrum Chemical Mfg. Corp. Safety data sheet: thimerosal, USP. Gardena: Spectrum Chemical Mfg. Corporation; 2022. Available from: https://www.spectrumchemical.com/msds/th125_aghs.pdf. [Last accessed on 18 Sep 2024].

Conklin L, Hviid A, Orenstein WA, Pollard AJ, Wharton M, Zuber P. Vaccine safety issues at the turn of the 21st century. BMJ Glob Health. 2021 May;6 Suppl 2:e004898. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004898, PMID 34011504, PMCID PMC8137241.

Caballero ML, Krantz MS, Quirce S, Phillips EJ, Stone CA Jr. Hidden dangers: recognizing excipients as potential causes of drug and vaccine hypersensitivity reactions. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021 Aug;9(8):2968-82. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.03.002, PMID 33737254, PMCID PMC8355062.

Sanofi pasteur. Fluson® quadrivalent. Swiftwater (pa): sanofi pasteur; 2021. Influenza virus vaccine quadrivalent types a and b (split virion). Product [monograph]. Available from: https://pdf.hres.ca/dpd_pm/00062890.pdf. [Last accessed on 18 Sep 2024].

Yorifuji T, Kado Y, Diez MH, Kishikawa T, Sanada S. Neurological and neurocognitive functions from intrauterine methylmercury exposure. Arch Environ Occup Health. 2016 May 3;71(3):170-7. doi: 10.1080/19338244.2015.1080153, PMID 26267674.

Masten SA. Butylparaben: review of toxicological literature. NC: National institute of environmental health sciences; 2005. Available from: https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/ntp/htdocs/chem_background/exsumpdf/butylparaben_508.pdf. [Last accessed 28 on May 2025].

Amadasi A, Mozzarelli A, Meda C, Maggi A, Cozzini P. Identification of xenoestrogens in food additives by an integrated in silico and in vitro approach. Chem Res Toxicol. 2009 Jan;22(1):52-63. doi: 10.1021/tx800048m, PMID 19063592, PMCID PMC2758355.

World Health Organization. Geneva [CH]. WHO; 2022 Oct 5. Medical product alert N° 6/2022: substandard (contaminated) paediatric medicines. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/05-10-2022-medical-product-alert-n-6-2022-substandard-(contaminated)-paediatric-medicines. [Last accessed on 04 Sep 2024].

Gupta A, Kumar J, Verma S, Singh H. Application of quality by design approach for the optimization of orodispersible film formulation. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2018;11(14):8-11. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2018.v11s2.28508.

Krantz MS, Liu Y, Phillips EJ, Stone CA JR. Anaphylaxis to pegylated liposomal echocardiogram contrast in a patient with IgE-mediated macrogol allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020 Apr;8(4):1416-1419.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.12.041, PMID 31954852, PMCID PMC7263401.

Ionova Y, Wilson L. Biologic excipients: importance of clinical awareness of inactive ingredients. PLOS One. 2020 Jun 25;15(6):e0235076. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0235076, PMID 32584876, PMCID PMC7316246.

Pantin C, Letellez J, Calzas J, Mohedano E. Indirect identification of hypersensitivity reaction to etoposide mediated by polysorbate 80. Farm Hosp. 2018 Jan 1;42(1):27-8. doi: 10.7399/fh.10882, PMID 29306312.

Perino E, Freymond N, Devouassoux G, Nicolas JF, Berard F. Xolair induced recurrent anaphylaxis through sensitization to the excipient polysorbate. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018 Jun;120(6):664-6. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2018.02.018, PMID 29481891.

Pottel J, Armstrong D, Zou L, Fekete A, Huang XP, Torosyan H. The activities of drug inactive ingredients on biological targets. Science. 2020 Jul 24;369(6502):403-13. doi: 10.1126/science.aaz9906, PMID 32703874, PMCID PMC7960226.

Bibera MA, Lo KM, Steele A. Potential cross reactivity of polysorbate 80 and cremophor: a case report. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2020 Jul;26(5):1279-81. doi: 10.1177/1078155219896848, PMID 31955702.

Meduniver. Cremophor EL poisoning and its side effects. Available from: https://meduniver/medical/toksikologia/otravlenie_kremoforom.html. [Last accessed on 08 Sep 2024].

Brockow K, Bauerdorf F, Kugler C, Darsow U, Biedermann T. ‘Idiopathic’ anaphylaxis caused by carboxymethylcellulose in ice cream. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021 Jan;9(1):555-557.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.10.051, PMID 33181345.

International Programme on Chemical Safety. Geneva (CH). World Health Organization; PIM 443: methylmercury. Available from: https://www.inchem.org/documents/pims/chemical/pim443.htm#sectiontitle:9.1%20%20acute%20poisoning. [Last accessed on 18 Sep 2024].

Farooque S, Kenny M, Marshall SD. Anaphylaxis to intravenous gelatine based solutions: a case series examining clinical features and severity. Anaesthesia. 2019 Feb;74(2):174-9. doi: 10.1111/anae.14497, PMID 30520028.

Abdul Bari M. The excipients between effects and the side effects. Med Care Res Rev. 2019 May;2(5):178.

Nemes D, Kovacs R, Nagy F, Mezo M, Poczok N, Ujhelyi Z. Interaction between different pharmaceutical excipients in liquid dosage forms assessment of cytotoxicity and antimicrobial activity. Molecules. 2018 Jul 23;23(7):1827. doi: 10.3390/molecules23071827, PMID 30041418, PMCID PMC6100184.

European Medicines Agency. Annex to the European commission guideline on excipients in the labelling and package leaflet of medicinal products for human use. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/annex-europeancommission-guideline-excipients-labelling-package-leaflet-medicinal-products-human-use. [Last accessed on 04 Feb 2025].

Kriegel C, Festag M, Kishore RS, Roethlisberger D, Schmitt G. Pediatric safety of polysorbates in drug formulations. Children (Basel). 2019 Dec 20;7(1):1. doi: 10.3390/children7010001, PMID 31877624, PMCID PMC7022221.

Rouaz K, Chiclana Rodriguez B, Nardi Ricart A, Sune Pou M, Mercade Frutos D, Sune Negre JM. Excipients in the paediatric population: a review. Pharmaceutics. 2021 Mar 13;13(3):387. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13030387, PMID 33805830, PMCID PMC8000418.

Saito J, Agrawal A, Patravale V, Pandya A, Orubu S, Zhao M. The current states challenges ongoing efforts and future perspectives of pharmaceutical excipients in pediatric patients in each country and region. Children (Basel). 2022 Mar 23;9(4):453. doi: 10.3390/children9040453, PMID 35455497, PMCID PMC9026161.

FDA. Pediatric research equity act (PREA). In: Silver Spring (MD): United States Food and Drug Administration; Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-resources/pediatric-research-equity-act-prea. [Last accessed on 20 Jan 2025].

European Medicines Agency. Paediatric regulation. In: Amsterdam: EMA; Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory-overview/paediatric-medicines-overview/paediatric-regulation.

Sujith T, Chakradhar T, Marpaka S, Sowmini K. Aspects of utilization and limitations of artificial intelligence in drug safety. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2021;14(8):34-9. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2021.v14i8.41979.

Wang Z, Liang L, Yin Z, Lin J. Improving chemical similarity ensemble approach in target prediction. J Cheminform. 2016 Apr 23;8:20. doi: 10.1186/s13321-016-0130-x, PMID 27110288, PMCID PMC4842302.

Nash A. Similarity ensemble approach finding targets (receptor proteins) for small molecules; 2019. Available from: https://distributedscience.wordpress.com.similarity-ensemble-approach-finding-targets-receptor-proteins-for-small-molecules. [Last accessed on 18 Sep 2024].

US Food and Drug Administration. Highlights of prescribing information: doxorubicin hydrochloride liposome injection for intravenous use. Food and Drug Administration; Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/050718Orig1s060lbl.pdf. [Last accessed on 10 Sep 2024].

US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry: nonclinical studies for the safety evaluation of pharmaceutical excipients. Silver Spring, (MD): FDA; 2005 May. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/72260/download.

US Food and Drug Administration. Inactive ingredients database download. In: Silver Spring, (MD): FDA; Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/inactive-ingredients-database-download. [Last accessed on 18 Sep 2024].

Salunke S, Brandys B, Giacoia G, Tuleu C. The step (safety and toxicity of excipients for paediatrics) database: part-2 the pilot version. Int J Pharm. 2013;457(1):310-22. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.09.013, PMID 24070789.

European Paediatric Formulation Initiative (EuPFI) STEP Database. London UK: University College London. Available from: https://step-db.ucl.ac.uk/eupfi/appDirectLink.do?appFlag=login. [Last accessed on 10 Sep 2024].

Zhang C, Mou M, Zhou Y, Zhang W, Lian X, Shi S. Biological activities of drug inactive ingredients. Brief Bioinform. 2022 Sep 20;23(5):bbac160. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbac160, PMID 35524477.

ACDINA. Hangzhou (CN): Innovative Drug Research and Bioinformatics Group. Zhejiang University. Available from: https://acdina.idrblab.net/ttd. [Last accessed on 10 Sep 2024].

UniProt Consortium. UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023 Jan 6;51(D1):D523-31. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac1052, PMID 36408920, PMCID PMC9825514.

PubChem. Bethesda: Available from: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/. [Last accessed on 18 Sep 2024].

Gene NC. In: Bethesda: National Center for Biotechnology Information, United States National Library of Medicine; Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/. [Last accessed 18 Sep 2024].

Gene NC. In: Bethesda: National Center for Biotechnology Information, United States National Library of Medicine; Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/. [Last accessed 18 Sep 2024].