Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 2, 2025, 423-431Original Article

IDENTIFYING LEAD COMPOUNDS FOR POTENTIAL ANTI-TUBERCULOSIS DRUGS BY IN SILICO MYCOBACTERIUM TUBERCULOSIS SHIKIMATE KINASE INHIBITORS SELECTION OF CHEMICAL LIBRARY

NUKI BAMBANG NUGROHO1*, BELLA ETIKA2, SRI TEGUH RAHAYU2, AJI WIBOWO1, EKA SISKA1

1Research Center for Vaccine and Drug, National Agency for Research and Innovation (BRIN), Cibinong, West Java, Indonesia. 2Pharmacy Study Program, Faculty of Health Sciences, Esa Unggul University, Jakarta-11510, Jakarta, Indonesia

*Corresponding author: Nuki Bambang Nugroho; *Email: nuki001@brin.go.id

Received: 24 Sep 2024, Revised and Accepted: 13 Jan 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: The present study aimed to identify Shikimate Kinase (SK) inhibitors as antitubercular agents from a chemical library by the utilization of molecular docking simulation, pharmacophore evaluation, and Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) prediction approaches.

Methods: A molecular docking study by Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) was used to screen 400,000 compounds from the Mcule ULTIMATE Express 1 chemical library. This docking study used a rigid docking technique to simulate the interaction between receptors and compounds. The screened compounds were then validated by pharmacophore and ADMET analyses to show the presence of positive characteristics.

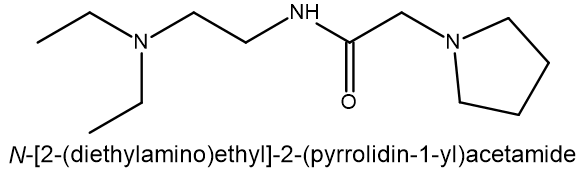

Results: The result of molecular docking simulation identified N-[2-(diethylamino)ethyl]-2-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)acetamide as the most promising candidate for targeting Mycobacterium tuberculosis Shikimate Kinase (MtSK), due to its binding energy score (-11.3412 kcal/mol) and suitability of interacting residues (Asp34 and Gly80). Moreover, this compound also shared similar pharmacophores with shikimate, and it had positive drug-like and ADMET properties.

Conclusion: This work identified one candidate for SK inhibitor from a pool of five drug-like hit compounds. These inhibitors show promise as prospective candidates for the development of a new anti-tuberculosis therapy and warrant additional experimental investigation.

Keywords: Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Shikimate pathway, Shikimate kinase, Molecular docking

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i2.52759 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease caused by the bacteria Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb). Tuberculosis is transmitted by airborne transmission when patients infected with the disease expel saliva particles carrying the bacterium into the air, usually via coughing or sneezing. Presently, this disease remains a worldwide pandemic, leading to the demise of 1.3 million people out of around 10.6 million reported cases of tuberculosis in 2022. The data had risen in comparison to the preceding year, notably reaching 10.3 million in 2021, and 10 million in 2020 [1]. This emphasizes the need to rapidly treat this disease to protect humanity.

Presently, tuberculosis still relies on the use of current therapies, which exhibit an estimated success rate of 85% in effectively healing people with tuberculosis. Untreated cases of tuberculosis are linked to a substantial death rate, estimated to exceed 50% [2]. As per the recommendations established by the World Health Organization (WHO), individuals diagnosed with drug-susceptible tuberculosis are recommended to follow a 6 mo treatment plan that includes the administration of isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide [1]. In contrast, individuals with TB who do not show improvement after receiving one or more drugs would need alternate treatment strategies and maybe a longer length of therapy. Managing Extensively Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis (XDR-TB), which is unresponsive to rifampicin, any fluoroquinolone, and bedaquiline/linezolid, poses significant difficulties, and the prospects of achieving successful treatment outcomes are typically unfavorable [1, 3].

Enzyme-based drugs remain crucial in the process of screening and developing treatments due to their vital role in the life cycle and metabolism of pathogens [4]. Moreover, more than 50% of pharmacological compounds are intentionally engineered to interact with enzymes to produce the intended effects [5]. The shikimate (SKM) pathway has attracted attention as a promising target for the development of antimicrobial agents due to its exclusive presence in bacteria, particularly Mtb, fungi, and plants while being lacking in humans [6]. The SKM pathway plays a crucial role in the synthesis of vital substances, including ubiquinone, folic acid, aromatic amino acids, and other aromatic compounds. Therefore, this pathway has been recognized as a promising target for the development of drugs that may treat tuberculosis.

SK is the fifth enzyme in the SKM pathway. The enzyme's function is to catalyze the conversion of SKM to Shikimate 3-Phosphate (S3P) by using ATP as a phosphate donor. The enzyme exists as a single unit with a molecular weight of 18.6 kDa and is composed of 176 amino acid residues [7, 8]. SK refers to a group of enzymes known as Monophosphate Nucleoside (NMPs) kinases. The enzymes consist of three components: the CORE, which has a loop that binds to phosphate; the LID, which contains amino acids that interact with ATP; and the NMP-binding domains, which are substituted by a site that binds to SKM. The LID domain has a flexible characteristic and plays a crucial role in the structural modifications that take place during substrate binding [9–11]. The aroK gene encodes SK. Studies have shown that aroK is crucial for the survival of Mtb, and inhibiting the gene's function might result in the organism's death [12].

The SKM pathway utilizes erythrose-4-phosphate from the pentose phosphate pathway and phosphoenol pyruvate from the glycolysis pathway as starting materials to synthesize chorismic acid through a series of seven enzymatic reactions. The three-dimensional structure of the seven enzymes involved in the SKM pathway of Mtb has been determined [8, 13]. While the importance of the SKM pathway has been confirmed, only 3-Dehydroquinate (DHQ) synthase, SK, and chorismate synthase have been individually validated [8]. Among these three enzymes, only SK has been used for computer-based screening of anti-TB agents [14–16]. Due to its more complete data compared to other targets, it would be more feasible to develop a screening system for anti-TB agents based on SK.

The objective of this research is to assess the Mcule chemical library for potential SK inhibitors by the use of molecular docking simulation, pharmacophore evaluation, and ADMET prediction techniques [17]. In this study, we assessed the interactions between the hit compounds and the MtSK enzyme by assessing the binding energy and the formation of hydrogen bonds and ionic interactions with the active site residues of the target protein. The similarity of the pharmacophores was evaluated. The drug-likeness was determined using the ADMET characteristic prediction approach.

This study enhances comprehension of the interaction between ligands and target proteins, as well as the similarity of pharmacophores and the ADMET characteristics. These findings may be further used via computational and experimental methods to develop prospective inhibitors for future anti-tuberculosis drug design.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

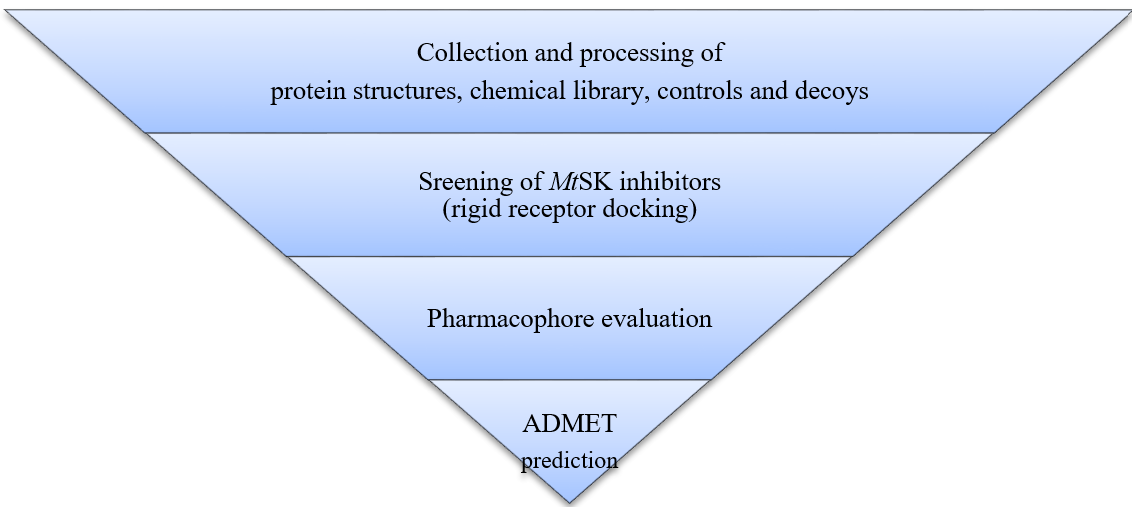

The study's methodology includes the collection and processing of protein structures and chemical library, the identification of MtSK inhibitors by screening, the evaluation of pharmacophore, and the prediction of ADMET, as seen in fig. 1. The PC workstation used for this study was provided with the following system specifications include the Windows 11 Pro operating system, an Intel® Core™ i7-10700K 3.80GHz CPU, 64GB of RAM, and an NVIDIA® Quadro P1000 graphics card.

Fig. 1: The study's workflow

Protein preparation

The pdb file displaying the crystal structure of MtSK enzyme, referred to as 2IYX, was obtained from the Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics (RCSB) protein databank (https://www.rcsb.org/). The active site was determined to be the region where the co-crystalline ligand (SKM) engages with the MtSK enzyme (PDB ID: 2IYX) [18]. The protein was prepared using the QuickPrep feature of MOE, using the default parameters. The protein crystal structure was prepared using various procedures, including the removal of water molecules, adjusting polar hydrogen atoms, and the isolation of the active pocket, rendering it suitable for the docking process [19, 20].

Ligand preparation

The Mcule ULTIMATE Express 1 chemical library was obtained in sdf.gz database format from the Mcule database, accessible at https://mcule.com/database/.

The MtSK positive inhibitor molecule's name from references was converted to their 2D structure using ChemDraw Professional 20.1.1. Subsequently, the molecule structure is stored as sdf files. These positive inhibitor molecules are used as positive control.

Decoy molecules (Supplementary table 1), as the negative control, were prepared using DUD-E (https://dude.docking.org/) [21]. MtSK positive inhibitor molecule as canonical Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) strings were submitted to the DUD-E web to generate decoy molecule SMILES strings, as the decoy for MtSK has not been available in DUD-E database. Subsequently, the decoy molecule SMILES was converted to its 2D structure using ChemDraw and then stored as sdf file.

All sdf molecule files (Mcule, MtSK positive inhibitor, and decoy) are opened in MOE as MOE database. The 3D molecules were prepared by performing the Wash function in the MOE Database Viewer. The Wash function parameters consisted of choosing the dominant protonation state at pH 7 and rebuilding the 3D coordinates while preserving the existing chirality.

Molecular docking

The molecular docking simulation was performed using the MOE 2022.02 bioinformatics program to evaluate the interaction between chemical library compounds and enzymes [25]. The docking findings were analyzed and visualized using MOE. The MOE-DOCK default docking algorithm, a rigid technique was employed for docking the molecules within the cavity, and a triangular matcher was utilized as the methodology for placement. The docking score utilized London ΔG, revealing negative energy values that signify reduced binding free energy and enhanced binding affinity of the ligands. The assessment included the interactions, particularly hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions, between the receptor and ligands. [19, 20, 26–28].

The docking receptors are defined by their relevant surface on the binding site in MOE. SKM as native ligands were verified by re-docking to the 2IYX receptor. The default MOE docking function was used in the docking setting. The docking technique used a two-step approach, in which each ligand was initially placed with the Triangle Matcher technique, employing a London ΔG scoring system. Initially, 30 poses are generated based on the initial placement. The poses are further refined using the rigid receptor technique, using the GBVI/WSA ΔG scoring system. Finally, the best five poses from each ligand docking were retained.

MtSK positive inhibitor and decoy molecules, as positive and negative control respectively, and 400.000 compounds in Mcule chemical library were bound to the SKM receptors of MtSK enzyme using the same docking method.

Pharmacophore evaluation

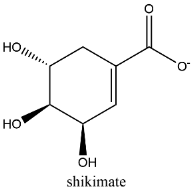

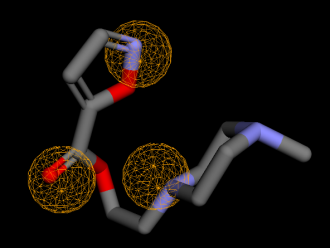

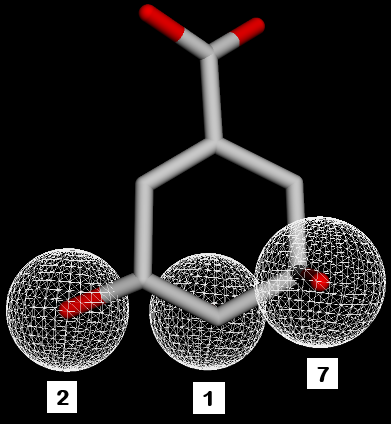

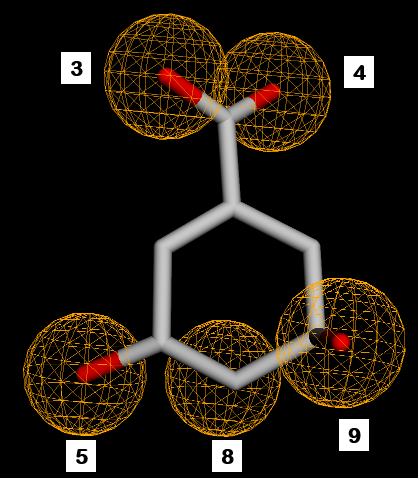

Pharmacophore evaluation was performed by the pharmit (https://pharmit.csb.pitt.edu/) [29]. SKM and hit compounds from docking screening, as 3D sdf files, were submitted to pharmit web using the Create feature of the web. The SKM pharmacophore search features were summarized in fig .

ADME and toxicity prediction

ADMET and toxicity prediction were performed by the SwissADME (http://www.swissadme.ch/) and ProTox 3.0 (https://tox.charite.de/protox3/) respectively [30, 31]. The compounds were submitted to SwissADME and ProTox 3.0 web as a SMILES file.

Table 1: MtSK positive control (PC) compounds

| Compound | Reference |

| PC1= (1R,6S,10S)-4-butyl-6,10-dihydroxy-2-oxabicyclo [4.3.1]deca-4(Z),7-diene-8-carboxylic acid | [22] |

| PC2= (1R,6S,10S)-4-ethoxymethyl-6,10-dihydroxy-2-oxabicyclo [4.3.1]deca-4(Z),7-diene-8-carboxylic acid | [22] |

| PC3= Ilimaquinone (ZINC000043411817) | [23] |

| PC4= Ilimaquinone | [23] |

| PC5= Rottlerin | [24] |

| PC6= (1R,6S,10S)-6,10-dihydroxy-4-propyl-2-oxabicyclo[4.3.1]deca-4(Z),7-diene-8-carboxylic acid | [22] |

| PC7= (1R,4S,6S,10S)-6,10-dihydroxy-4-methyl-2-oxabicyclo[4.3.1]dec-7-ene-8-carboxylic acid | [22] |

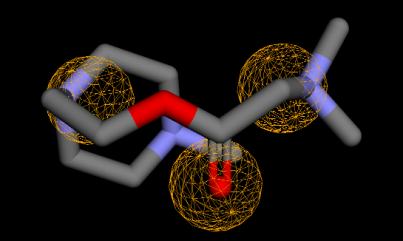

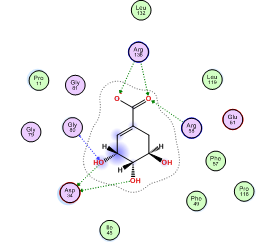

Fig. 2: SKM pharmacophore features. 1,2,7=hydrogen donor. 3,4,5,8,9=hydrogen acceptor. 6=negative ion. 10=hydrophobic

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Molecular docking modeling is essential, particularly for the screening of prospective novel therapeutic molecules. Our study identified one candidate SK inhibitor from a total of 5 hit compounds.

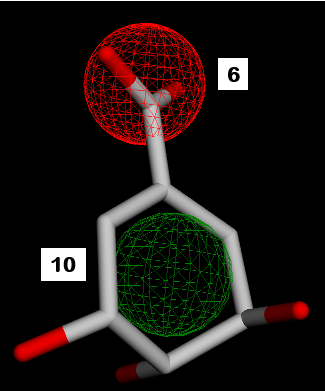

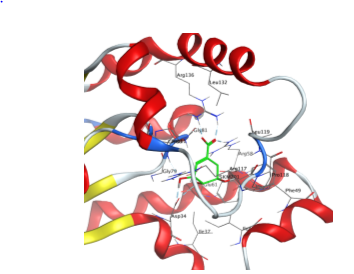

Validation docking of MtSK ligands

The MOE software was used to dock 400,000 small molecules from the Mcule library onto the prepared protein structure of MtSK (PDB ID: 2IYX). Previously, it was essential to evaluate the docking settings and software by determining whether the ligand could be accurately repositioned inside the protein structure during the re-docking process. The assessment of the redocking procedure's validity involves analyzing the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) and its corresponding residuals. After undergoing three redocking attempts, it was noted that the native ligand consistently held nearly the same location within the protein structure, as seen in . In addition, it formed hydrogen bond interactions with Asp34, Gly80, Arg58, and Arg136 (), exhibiting a comparable amount of interaction to that seen in previous studies [18].

Table 2: Validation docking of MtSK ligand with rigid receptor

| Protein | Ligand | ΔG (kcal/mol) | RMSD | Interaction |

| MtSK (2IYX) | SKM | -8.1982 | 0.1451 |

|

| -8.2414 | 0.1419 | |||

| -8.2289 | 0.1444 | |||

| In native protein | Same as above |

|

|

| (a) | (b) |

Fig. 3: MtSK protein structure and SKM interaction with MtSK residues. (a) View of MtSK active site with SKM bound. The protein’s chain is depicted as a ribbon, SKM in green licorice stick shape, and amino acids that form the active site in wire lines. (b) 2D diagram of MtSK-SKM interaction. Pink circle-black outline = polar amino acid, pink circle-blue outline = basic amino acid, pink circle-red outline = acidic amino acid, green circle = hydrophobic, green arrow dashed line = sidechain donor/acceptor, and blue arrow dashed line = backbone donor/acceptor

Additionally, we verified our suggested docking software and parameters using established compounds known for their inhibitory effect against MtSK, as detailed in . The compounds were anticipated to be active by in silico simulations and shown efficacy in vitro investigations, as well as in vivo testing, as described in other publications [22–24]. The validation protocol must be executed using a decoy database (Supplementary table 1) comprising non-binding molecules against a target enzyme to prevent false positive results, while simultaneously enhancing the test's validity by producing true positive outcomes in virtual screening-related tasks.

The binding energies for established MtSK inhibitors ranged from-10.8 kcal/mol to-7.5 kcal/mol, as shown in . Many of those compounds are likely to exhibit favourable interactions with MtSK, as anticipated, given that their binding energies were either superior to or comparable with the re-docked SKM’s binding energies presented in . The maximum values of PC7 remained comparable to those of SKM. Meanwhile, the binding energies of the produced decoy compounds ranged from -8.7586 kcal/mol to 555.6595 kcal/mol. The majority exhibited higher binding energies than SKM, suggesting that these compounds were unlikely to demonstrate activity against the target enzyme. Only a small portion of compounds exhibited lower binding energies compared to SKM, suggesting a diminished likelihood of false positive occurrences. The results suggest that the docking parameters and associated software are suitable for conducting molecular docking-based screening.

Table 3: MtSK inhibition positive compounds (PC) and decoy compounds (DC) docking simulation to MtSK

| Compound | Binding energy (ΔG kcal/mol) | Mean | ||

| R1 | R2 | R3 | ||

| PC1 | -8.4362 | -8.7562 | -8.7559 | -8.6494 |

| PC2 | -8.3645 | -8.3641 | -8.3639 | -8.3642 |

| PC3 | -8.6853 | -8.7181 | -8.7104 | -8.7046 |

| PC4 | -9.3120 | -9.3118 | -9.3125 | -9.3121 |

| PC5 | -10.4846 | -11.3840 | -10.6331 | -10.8339 |

| PC6 | -8.1138 | -8.1139 | -8.1140 | -8.1139 |

| PC7 | -7.5561 | -7.5563 | -7.5655 | -7.5593 |

| DC1 | -6.8897 | -6.8968 | -6.8909 | -6.8925 |

| DC2 | -8.4188 | -8.7203 | -8.2196 | -8.4529 |

| DC3 | -6.7520 | -7.6378 | -6.6465 | -7.0121 |

| DC4 | -6.8034 | -6.7951 | -6.7954 | -6.7980 |

| DC5 | -6.8434 | -6.8430 | -6.8436 | -6.8433 |

| DC6 | -7.2055 | -7.2046 | -7.2044 | -7.2048 |

| DC7 | -7.0635 | -7.1032 | -7.0987 | -7.0885 |

| DC8 | -8.5373 | -8.1467 | -8.5361 | -8.4067 |

| DC9 | -6.7083 | -6.7082 | -6.7084 | -6.7083 |

| DC10 | -7.1174 | -7.3105 | -7.0463 | -7.1581 |

| DC11 | -7.0230 | -7.0240 | -7.0835 | -7.0435 |

| DC12 | -7.3649 | -7.3656 | -7.3629 | -7.3645 |

| DC13 | -7.9238 | -7.9287 | -8.0591 | -7.9705 |

| DC14 | -8.3365 | -8.3351 | -8.3341 | -8.3352 |

| DC15 | -9.0962 | -8.6478 | -8.5318 | -8.7586 |

| DC16 | -8.4656 | -7.5692 | -7.5644 | -7.8664 |

| DC17 | -8.3252 | -8.3337 | -8.3351 | -8.3314 |

| DC18 | -6.1479 | -6.1476 | -6.1476 | -6.1477 |

| DC19 | -5.8099 | -5.7460 | -5.7240 | -5.7600 |

| DC20 | -6.5119 | -6.5861 | -6.7114 | -6.6031 |

| DC21 | -7.1836 | -6.6600 | -7.1837 | -7.0091 |

| DC22 | -6.2282 | -6.2282 | -6.2283 | -6.2282 |

| DC23 | -6.8392 | -6.8379 | -6.8429 | -6.8400 |

| DC24 | -6.8640 | -6.8635 | -6.8647 | -6.8640 |

| DC25 | -5.9586 | -5.9587 | -5.9586 | -5.9586 |

| DC26 | -6.5062 | -6.3568 | -6.5155 | -6.4595 |

| DC27 | -6.0477 | -6.0511 | -6.0480 | -6.0489 |

| DC28 | -6.3589 | -6.1443 | -6.1659 | -6.2230 |

| DC29 | -5.9849 | -5.9874 | -5.9877 | -5.9867 |

| DC30 | -5.9872 | -6.0153 | -5.9961 | -5.9996 |

| DC31 | -6.4107 | -6.4105 | -6.4107 | -6.4106 |

| DC32 | -6.7808 | -6.7868 | -6.7801 | -6.7826 |

| DC33 | -6.1361 | -6.1366 | -6.1366 | -6.1364 |

| DC34 | -6.8834 | -6.8835 | -6.8835 | -6.8835 |

| DC35 | -6.7555 | -6.7555 | -6.7560 | -6.7557 |

| DC36 | -6.6028 | -6.2761 | -6.6480 | -6.5090 |

| DC37 | -6.0748 | -6.0786 | -6.0777 | -6.0770 |

| DC38 | -6.0739 | -6.2443 | -6.2851 | -6.2011 |

| DC39 | -6.3142 | -6.2634 | -5.8735 | -6.1504 |

| DC40 | -6.1365 | -6.3596 | -6.3599 | -6.2853 |

| DC41 | -6.5768 | -6.5767 | -6.5719 | -6.5751 |

| DC42 | -6.9344 | -6.9394 | -6.9390 | -6.9376 |

| DC43 | -5.8292 | -6.1605 | -6.0303 | -6.0067 |

| DC44 | -6.0352 | -6.0350 | -6.0376 | -6.0359 |

| DC45 | -6.3407 | -6.3409 | -6.3410 | -6.3409 |

| DC46 | -6.4027 | -6.4030 | -6.4033 | -6.4030 |

| DC47 | -6.5943 | -6.5959 | -6.5960 | -6.5954 |

| DC48 | -5.6434 | -5.6436 | -5.6510 | -5.6460 |

| DC49 | -6.2193 | -7.1672 | -6.5859 | -6.6575 |

| DC50 | -6.8435 | -6.6063 | -6.9794 | -6.8098 |

| DC51 | -6.3278 | -6.3276 | -6.3223 | -6.3259 |

| DC52 | -6.0076 | -6.0117 | -6.0070 | -6.0088 |

| DC53 | -6.2728 | -6.2706 | -6.2704 | -6.2713 |

| DC54 | -6.7361 | -6.7313 | -6.7361 | -6.7345 |

| DC55 | -6.2790 | -6.6987 | -7.0429 | -6.6735 |

| DC56 | -6.3103 | -6.3103 | -6.3099 | -6.3101 |

| DC57 | -6.2371 | -6.2337 | -6.2344 | -6.2351 |

| DC58 | -6.2528 | -6.2529 | -6.2628 | -6.2562 |

| DC59 | -6.0905 | -6.5716 | -6.5746 | -6.4122 |

| DC60 | -6.3760 | -6.5219 | -5.9211 | -6.2730 |

| DC61 | -6.5247 | -6.5246 | -6.5248 | -6.5247 |

| DC62 | -6.4044 | -6.4039 | -6.4037 | -6.4040 |

| DC63 | -6.7617 | -6.7655 | -6.7645 | -6.7639 |

| DC64 | -7.3421 | -6.7607 | -6.7665 | -6.9564 |

| DC65 | -7.2263 | -7.2264 | -7.2258 | -7.2262 |

| DC66 | -6.4877 | -6.1855 | -6.4870 | -6.3868 |

| DC67 | -6.6136 | -6.7003 | -6.5514 | -6.6218 |

| DC68 | -5.9535 | -5.9541 | -5.9540 | -5.9538 |

| DC69 | -5.9013 | -5.9018 | -5.9009 | -5.9013 |

| DC70 | -6.4256 | -6.4257 | -6.4269 | -6.4261 |

| DC71 | -6.6306 | -6.6337 | -6.6335 | -6.6326 |

| DC72 | -6.5378 | -6.5363 | -6.5383 | -6.5375 |

| DC73 | -6.2702 | -6.2877 | -6.2863 | -6.2814 |

| DC74 | -5.9291 | -5.9288 | -5.9292 | -5.9291 |

| DC75 | -7.8033 | -8.4245 | -8.1482 | -8.1253 |

| DC76 | -6.8362 | -6.7142 | -6.7238 | -6.7581 |

| DC77 | -6.0910 | -6.0930 | -6.0935 | -6.0925 |

| DC78 | -5.9012 | -5.2609 | -5.9032 | -5.6885 |

| DC79 | -6.8418 | -6.8423 | -6.8418 | -6.8420 |

| DC80 | -6.2653 | -6.2602 | -6.2629 | -6.2628 |

| DC81 | -6.4939 | -6.4940 | -6.4890 | -6.4923 |

| DC82 | -6.6228 | -6.6230 | -6.6232 | -6.6230 |

| DC83 | -6.6978 | -6.6985 | -6.6981 | -6.6981 |

| DC84 | -6.0239 | -6.0220 | -6.0224 | -6.0228 |

| DC85 | -6.7037 | -6.7000 | -6.6998 | -6.7012 |

| DC86 | -5.8643 | -5.9451 | -5.8649 | -5.8914 |

| DC87 | -5.9779 | -5.9768 | -5.9780 | -5.9776 |

| DC88 | -6.5661 | -6.5767 | -6.2610 | -6.4679 |

| DC89 | -6.1152 | -6.3285 | -6.3344 | -6.2594 |

| DC90 | -6.4329 | -6.4364 | -6.3981 | -6.4225 |

| DC91 | -6.5507 | -6.5504 | -6.5506 | -6.5506 |

| DC92 | -6.5254 | -6.5246 | -6.5251 | -6.5251 |

| DC93 | -6.4552 | -6.4552 | -6.4552 | -6.4552 |

| DC94 | -6.2544 | -6.2528 | -6.2541 | -6.2538 |

| DC95 | -6.5213 | -6.5209 | -6.5206 | -6.5210 |

| DC96 | -6.6465 | -6.6469 | -6.6394 | -6.6443 |

| DC97 | -6.3562 | -6.3563 | -6.3564 | -6.3563 |

| DC98 | -6.1193 | -6.1185 | -6.1191 | -6.1190 |

| DC99 | -7.0092 | -6.7653 | -7.1153 | -6.9633 |

| DC100 | -7.9313 | -7.7041 | -7.8063 | -7.8139 |

| DC101 | -5.7475 | -7.6937 | -7.6721 | -7.0378 |

| DC102 | -6.9964 | -7.1549 | -7.3419 | -7.1644 |

| DC103 | 434.9636 | 194.2555 | 1031.7593 | 553.6595 |

| DC104 | -8.6874 | -8.6941 | -8.6857 | -8.6891 |

| DC105 | -8.3803 | -8.5649 | -8.6749 | -8.5400 |

| DC106 | -3.9768 | -4.6151 | 19.8663 | 3.7581 |

| DC107 | -8.7423 | -7.9112 | -8.0356 | -8.2297 |

Screening of MtSK inhibitors

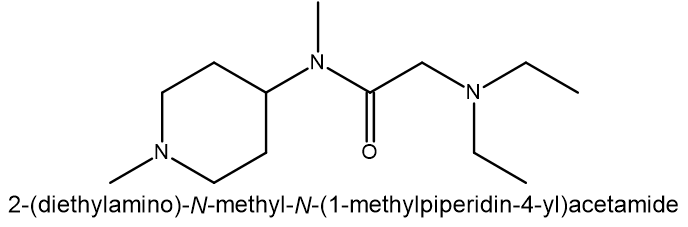

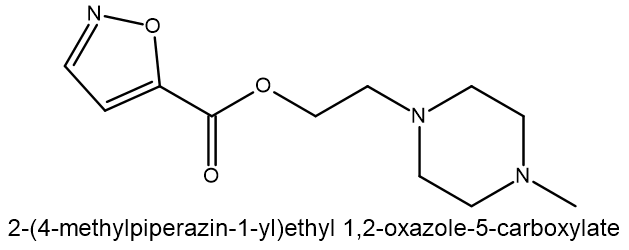

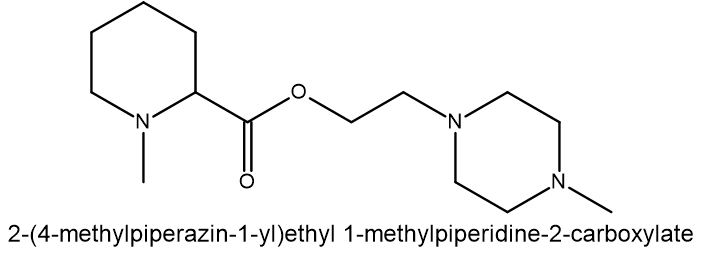

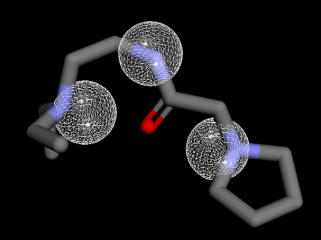

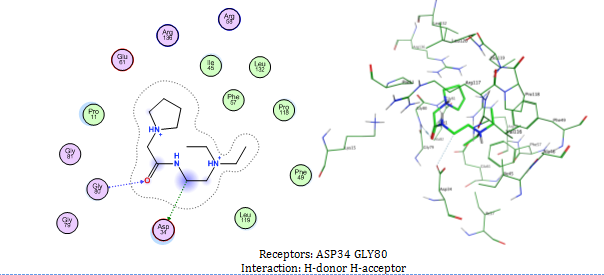

The outcome of docking 400,000 small molecules to the MtSK protein structure (PDB ID: 2IYX) displayed in . Out of the total quantity of compounds that underwent docking, only five achieved a higher score using the rigid receptor docking technique compared to SKM as the native ligands (compounds 1 to 5 in ). The compound 1, N-[2-(diethylamino)ethyl]-2-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)acetamide exhibits the most favorable binding score (ΔG) of -11.3412 kcal/mol.

Compound 1 revealed interaction with Asp34 and Gly80 in MtSK. The interaction of compound 1 with MtSK residues is illustrated in . As a result of rigid docking (), compound 1 establishes hydrogen connections with Asp34 via a carbon -CH2- as a hydrogen donor and with Gly80 through a carbonyl group as a hydrogen acceptor. Compound 2 to compound 5 also revealed a hydrogen bond, as a hydrogen donor, with Asp34. The Asp34 residue consistently appeared in all analyses related to hit compounds, suggesting its significant role. This aligns with the prior study, which asserts that Asp34 is crucial for the positioning of SKM within the active site of MtSK. Besides Asp34, other residues (Gly79, Gly80 and Arg136) also play a role in the hydrogen bond of docking simulations with these compounds.

Table 4: Result of chemical library docking simulation to MtSK

| Compound | Binding energy (ΔG kcal/mol) | Residue H-bond with compound |

| 1 | -11.3412 | Asp34, Gly80 |

| 2 | -9.6227 | Asp34 |

| 3 | -8.5597 | Gly79, Gly80 |

| 4 | -8.4616 | Asp34 |

| 5 | -8.2939 | Asp34, Arg136 |

| SKM | -8.2414 | Asp34, Gly80, Arg58, Arg136 |

Compound 1: MCULE-7869324005 SMILES: C(CN1CCCC1)(=O)NCCN(CC)CC |

Compound 2: MCULE-4639721901 SMILES: C(CN(CC)CC)(=O)N(C1CCN(C)CC1)C |

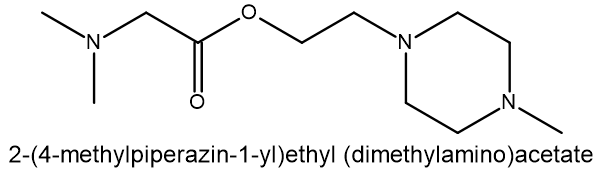

Compound 3: MCULE-7301005464 SMILES: O(CCN1CCN(C)CC1)C(C1=CC=NO1)=O |

Compound 4: MCULE-7131512429 SMILES: O(CCN1CCN(C)CC1)C(C1CCCCN1C)=O |

Compound 5: MCULE-9965096728 SMILES: O(CCN1CCN(C)CC1)C(CN(C)C)=O |

SKM |

Fig. 4: Hit compounds of MtSK inhibitors by docking screening

Fig. 5: Compound 1 interaction with MtSK residues in docking simulation. In the 3D illustration, Compound 1 is illustrated using green licorice stick, with the amino acids that make up the active site represented by wire lines. Pink circle-black outline = polar amino acid, pink circle-blue outline = basic amino acid, pink circle-red outline = acidic amino acid, green circle = hydrophobic, green arrow dashed line = sidechain donor/acceptor, and blue arrow dashed line = backbone donor/acceptor

Pharmacophore evaluation, ADME, and toxicity prediction

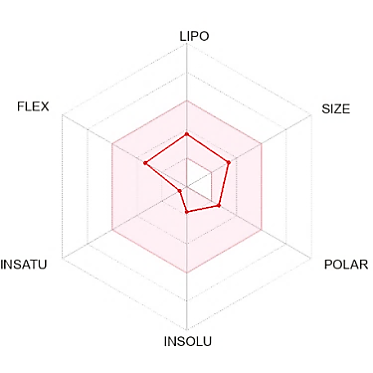

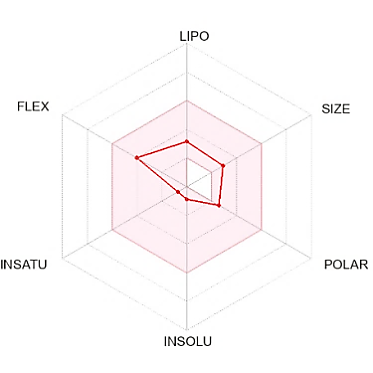

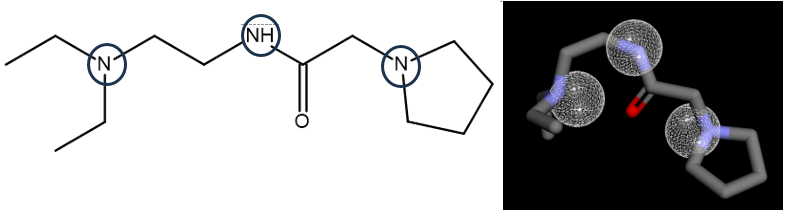

The evaluation of the pharmacophore indicates that only three molecules (compounds 1, 3, and 5) out of the five compounds exhibit similarity to the SKM hydroxyl. Compound 1 exhibits pharmacophore similarities as hydrogen donors, whereas compounds 3 and 5 act as hydrogen acceptors ().

The pharmacophore of compound 1, which acts as a hydrogen donor via its nitrogen moiety (), demonstrates the role of its pyrrolidin nitrogen in the docking interaction with ASP34. The pharmacophore evaluation did not support the compound's docking interaction with Gly80, which had a carbonyl group as a hydrogen receptor.

Drug likeness is determined by following the Lipinski rule, which states that the Molecular Weight (MW) should be less than or equal to 500, the MLogP value should be less than or equal to 4.15, the number of hydrogen bond acceptors should be less than or equal to 10, and the number of hydrogen bond donors should be less than or equal to 5 [32].

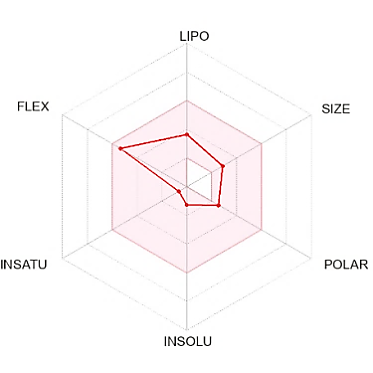

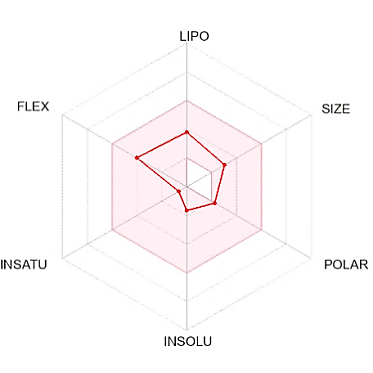

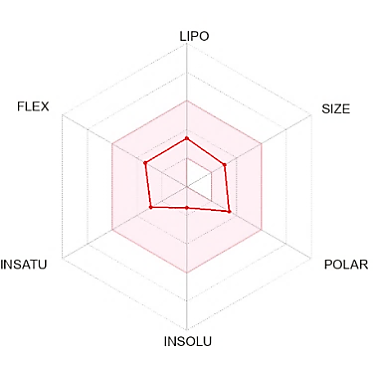

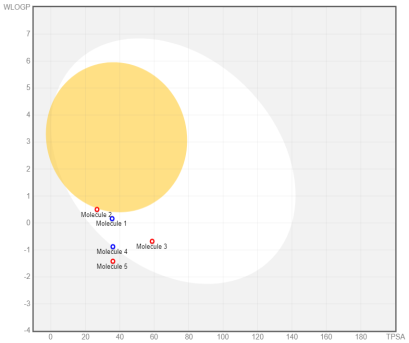

The suitable physicochemical for oral bioavailability followed to SwissADME, which uses 6 physicochemical properties, are taken into account: lipophilicity, size, polarity, solubility, flexibility, and saturation. The pink area in the oral bioavailability chart (fig. 8 & table 5) represents the optimal range for each property, lipophilicity: XLogP3 between −0.7 and+5.0, size: MW between 150 and 500 g/mol, polarity: Topological Polar Surface Area (TPSA) between 20 and 130Å, solubility: log S not higher than 6, saturation: fraction of carbons in the sp3 hybridization not less than 0.25, and flexibility: no more than 9 rotatable bonds [30].

In the BOILED-Egg (Brain Or IntestinaL EstimateD) predictive model, the white region is the physicochemical space of molecules with the highest probability of being absorbed by the gastrointestinal tract, and the yellow region is the physicochemical space of molecules with the highest probability of permeating to the brain [33]. Compound 1 in the white region of the BOILED-Egg predictive model.

Compound 1 did not have any Lipinski rule violation, was predicted orally bioavailable, and had a high probability of being absorbed by the gastrointestinal tract, then this compound was considered drug-like. The LD50 of a compound between 300 and 2000 mg/kg body weight indicated that compounds are harmful if swallowed, according to toxicity classes defined by the Globally Harmonized System of Classification of Labelling of Chemicals (GHS) [34]. All other compounds exhibited comparable ADMET predictions to compound 1 (table 5).

Compound 1. RMSD=0,5374 |

Compound 3. RMSD=0,4409 |

Compound 5 RMSD=0,4809 |

Fig. 6: Pharmacophore feature similarity. Compounds 1 with SKM hydrogen donors 1,2,7 feature similarity and compounds 3 and 5 with SKM hydrogen acceptors 5,8,9 feature similarity

Fig. 7: Pharmacophore of compound 1 as hydrogen donor

Compound 1 |

Compound 2 |

Compound 3 |

Compound 4 |

Compound 5 |

Boiled-Egg |

Fig. 8: Oral bioavailability chart and boiled-egg of hit compounds

Table 5: ADME and toxicity prediction of hit compounds

| ADMET prediction component | Hit compounds | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Molecule Weight | 227.35 | 241.37 | 239.27 | 269.38 | 229.32 |

| Fraction Carbon sp3 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.64 | 0.93 | 0.91 |

| Rotatable bonds | 8 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 6 |

| H-bond acceptors | 3 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 5 |

| H-bond donors | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| TPSA | 35.58 | 26.79 | 58.81 | 36.02 | 36.02 |

| XLogP3 | 0.87 | 1.12 | 0.4 | 0.91 | 0.03 |

| MLogP | 0.62 | 0.9 | -0.06 | 0.74 | -0.08 |

| ESOL Log S | -1.27 | -1.65 | -1.46 | -1.75 | -0.88 |

| Lipinski violations | No | No | No | No | No |

| LD50 mg/Kg body weight | 1050 | 1300 | 1768 | 900 | 1500 |

| Toxicity class | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

CONCLUSION

In silico investigations were conducted to investigate the effectiveness of the Mcule ULTIMATE Express 1 chemical library as an inhibitor of MtSK. A total of 400,000 molecules underwent screening by molecular docking simulation, resulting in the identification of N-[2-(diethylamino) ethyl]-2-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)acetamide as the most effective candidate for targeting MtSK within a group of five drug-like hit molecules. Pharmacophore investigation supported the confirmation of this compound. This compound exhibited favorable drug-like properties and was suitable for oral administration, including good absorption qualities related to the gastrointestinal tract. These findings indicate that this candidate shows promise for being developed as the lead compound for a new anti-tuberculosis medicine through experimental study.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

NBN performed the research design and analysis, ADMET data analysis, whole paper drafting and supervised the research. BE performed collection and analysis of molecular docking, pharmacophore evaluation, and ADMET data. STR performed the research design and analysis, paper drafting (ADMET), and supervised the research. AW contributed to the molecular docking and visualization tools and performed molecular docking analysis and paper drafting (molecular docking). ES performed pharmacophore evaluation and paper drafting (introduction).

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The author (s) declare(s) that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

REFERENCES

World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2023; 2023. Available from: https://iris.who.int.

Tiemersma EW, van der Werf MJ, Borgdorff MW, Williams BG, Nagelkerke NJ. Natural history of tuberculosis: duration and fatality of untreated pulmonary tuberculosis in HIV negative patients: a systematic review. PLOS One. 2011;6(4):e17601. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017601, PMID 21483732.

Ramdhani D, Kusuma SA. In silico identification of natural products with antituberculosis activity for the inhibition of inha and ethr proteins from mycobacterium tuberculosis. Int J Appl Pharm. 2023;15:169-74.

Geronikaki A. Current trends in enzyme inhibition and docking analysis in drug design-part-IV. Curr Top Med Chem. 2021;21(6):461. doi: 10.2174/156802662106210304111713, PMID 33849411.

Hopkins AL, Groom CR. The drug gable genome. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2002;1(9):727-30. doi: 10.1038/nrd892, PMID 12209152.

Bentley R. The shikimate pathway–a metabolic tree with many branches. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1990;25(5):307-84. doi: 10.3109/10409239009090615, PMID 2279393.

Rosado LA, Vasconcelos IB, Palma MS, Frappier V, Najmanovich RJ, Santos DS. The mode of action of recombinant Mycobacterium tuberculosis shikimate kinase: kinetics and thermodynamics analyses. PLOS One. 2013;8(5):e61918. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061918, PMID 23671579.

Nunes JE, Duque MA, de Freitas TF, Galina L, Timmers LF, Bizarro CV. Mycobacterium tuberculosis shikimate pathway enzymes as targets for the rational design of anti-tuberculosis drugs. Molecules. 2020;25(6):1259. doi: 10.3390/molecules25061259, PMID 32168746.

Vonrhein C, Schlauderer GJ, Schulz GE. Movie of the structural changes during a catalytic cycle of nucleoside monophosphate kinases. Structure. 1995;3(5):483-90. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00181-2, PMID 7663945.

Han C, Zhang J, Chen L, Chen K, Shen X, Jiang H. Discovery of Helicobacter pylori shikimate kinase inhibitors: bioassay and molecular modeling. Bioorg Med Chem. 2007;15(2):656-62. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.10.058, PMID 17098431.

Saidemberg DM, Passarelli AW, Rodrigues AV, Basso LA, Santos DS, Palma MS. Shikimate kinase (EC 2.7.1.71) from Mycobacterium tuberculosis: kinetics and structural dynamics of a potential molecular target for drug development. Curr Med Chem. 2011;18(9):1299-310. doi: 10.2174/092986711795029500, PMID 21366533.

Parish T, Stoker NG. The common aromatic amino acid biosynthesis pathway is essential in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbiology (Reading). 2002;148(10):3069-77. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-10-3069, PMID 12368440.

Almeida AM, Marchiosi R, Abrahão J, Constantin RP, dos Santos WD, Ferrarese-Filho O. Revisiting the shikimate pathway and highlighting their enzyme inhibitors. Phytochem Rev. 2024;23(2):421-57. doi: 10.1007/s11101-023-09889-6.

Gordon S, Simithy J, Goodwin DC, Calderon AI. Selective Mycobacterium tuberculosis shikimate kinase inhibitors as potential antibacterials. Perspect Medicin Chem. 2015;7:9-20. doi: 10.4137/PMC.S13212, PMID 25861218.

Rahul Reddy MB, Krishnasamy SK, Kathiravan MK. Identification of novel scaffold using ligand and structure-based approach targeting shikimate kinase. Bioorg Chem. 2020;102:104083. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2020.104083, PMID 32745735.

Kawamoto S, Hori C, Taniguchi H, Okubo S, Aoki S. Identification of novel antimicrobial compounds targeting Mycobacterium tuberculosis shikimate kinase using in silico hierarchical structure-based drug screening. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 2023;141:102362. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2023.102362, PMID 37311288.

Al-Mohaya M, Mesut B, Kurt A, Çelik YS. In silico approaches which are used in pharmacy. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2024;14:225-39. doi: 10.7324/JAPS.2024.154854.

Hartmann MD, Bourenkov GP, Oberschall A, Strizhov N, Bartunik HD. Mechanism of phosphoryl transfer catalyzed by shikimate kinase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Mol Biol. 2006;364(3):411-23. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.09.001, PMID 17020768.

El-Sawy ER, Abo-Salem HM, Mahmoud K, Zarie ES, El-Metwally AM, Mandour AH. Synthesis, anticancer activity and molecular modeling study of novel 1, 3-diheterocycles indole derivatives. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2015;7:1-9.

Abo-Salem HM, Ahmed KM, Hallouty SE, El-Sawy ER, Mandour AH. Synthesis, molecular docking and anti-proliferative activity of new series of 1-methylsulphonyl-3-indolyl heterocycles. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2016;8(12):113-23. doi: 10.22159/ijpps.2016v8i12.14841.

Mysinger MM, Carchia M, Irwin JJ, Shoichet BK. Directory of useful decoys, enhanced (DUD-E): better ligands and decoys for better benchmarking. J Med Chem. 2012;55(14):6582-94. doi: 10.1021/jm300687e, PMID 22716043.

Pernas M, Blanco B, Lence E, Thompson P, Hawkins AR, Gonzalez Bello C. Synthesis of rigidified shikimic acid derivatives by ring-closing metathesis to imprint inhibitor efficacy against shikimate kinase enzyme. Org Chem Front. 2019;6(14):2514-28. doi: 10.1039/C9QO00562E.

Simithy J, Fuanta NR, Hobrath JV, Kochanowska Karamyan A, Hamann MT, Goodwin DC. Mechanism of irreversible inhibition of Mycobacterium tuberculosis shikimate kinase by ilimaquinone. Biochim Biophys Acta Proteins Proteom. 2018;1866(5-6):731-9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2018.04.007, PMID 29654976.

Pandey S, Chatterjee A, Jaiswal S, Kumar S, Ramachandran R, Srivastava KK. Protein kinase C-δ inhibitor, rottlerin inhibits growth and survival of mycobacteria exclusively through shikimate kinase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;478(2):721-6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.08.014, PMID 27498028.

ULC CCG. Molecular Operating Environment (MOE), 2022.02. Chemical Computing Group ULC, 910-1010 Sherbrooke St. W., Montreal, QC H3A 2R7; 2024.

Nossier ES, El-Hallouty SM, Zaki ER. Synthesis, anticancer evaluation and molecular modeling of some substituted thiazolidinonyl and thiazolyl pyrazole derivatives. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2015;7:353-9.

Thangavelu P, Cellappa S, Thangavel S. Synthesis, evaluation and docking studies of novel formazan derivatives as an enoyl-acp reductase inhibitor. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2018;10(8):56. doi: 10.22159/ijpps.2018v10i8.26819.

Wardani AK, Ritmaleni SEP. Molecular docking studies of HGV-6 analogue as a potential PBP-1A inhibitor. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2020;12:8-12.

Sunseri J, Koes DR. Pharmit: interactive exploration of chemical space. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(W1):W442-8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw287, PMID 27095195.

Daina A, Michielin O, Zoete V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci Rep. 2017;7:42717. doi: 10.1038/srep42717, PMID 28256516.

Banerjee P, Kemmler E, Dunkel M, Preissner R. ProTox 3.0: a webserver for the prediction of toxicity of chemicals. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024;52(W1):W513-20. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkae303, PMID 38647086.

Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;46(1-3):3-26. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0, PMID 11259830.

Daina A, Zoete V. A BOILED-egg to predict gastrointestinal absorption and brain penetration of small molecules. Chem Med Chem. 2016;11(11):1117-21. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201600182, PMID 27218427.

Nations U. Globally harmonized system of classification and labelling of chemicals. 4th Rev. ed. United Nations Economic Commission for Europe; 2009. p. 201.