Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 2, 2025, 65-77Review Article

INFLUENCE OF DRUG DELIVERY SYSTEMS ON THE SAFETY AND EFFECTIVENESS PROFILE OF RIBAVIRIN

MIKHEL I. B.1* , TITOVA S. A.2, BAKHRUSHINA E. O.3

, TITOVA S. A.2, BAKHRUSHINA E. O.3 , STEPANOVA O. I.4

, STEPANOVA O. I.4 , KRASNYUK I. I.5

, KRASNYUK I. I.5 , SMOLYARCHUK E. A.6

, SMOLYARCHUK E. A.6 , KRASNYUK I. I.7

, KRASNYUK I. I.7

1,3,7Department of Pharmaceutical Technology A. P. Nelyubin Institute of Pharmacy, I. M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University (Sechenov University), Moscow, Russia. 2I. M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University (Sechenov University), Moscow, Russia. 4,6Department of Pharmacology A. P. Nelyubin Institute of Pharmacy, I. M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University (Sechenov University), Moscow, Russia. 5Department of Analytical, Physical and Colloidal Chemistry A. P. Nelyubin Institute of Pharmacy, I. M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University (Sechenov University), Moscow, Russia

*Corresponding author: Mikhel I. B.; *Email: mikheliosif@gmail.com

Received: 04 Oct 2024, Revised and Accepted: 24 Dec 2024

ABSTRACT

Ribavirin is an antiviral drug with a wide spectrum of pharmacological activity. The development of drug delivery systems that increase the safety and effectiveness of ribavirin has been the subject of scientific research for decades. The aim of this article is to examine the published information on this topic, evaluate it according to several criteria, and outline the primary perspectives on this subject within the fields of pharmacy and pharmacology. The results of the evaluation indicate that, despite the extensive and ongoing discourse surrounding the potential modifications to ribavirin within the international scientific community, the majority of publications adopt an illustrative approach. Many relevant and promising applied studies require further development, comprehensive biopharmaceutical indicator testing, rigorous clinical efficacy assessment, and a thorough evaluation of patient compliance.

Keywords: Ribavirin, Drug delivery systems, Excipients, Side effects, Hemolytic anemia, Bioavailability

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i2.52864 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Ribavirin is an Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) that is a nucleoside analogue and is currently one of the most recommended elements in the complex treatment of chronic hepatitis C [1]. Due to the ever-growing need for effective antiviral agents, ribavirin can currently be used in the pharmacotherapy of chronic hepatitis E [2], Lassa fever [3, 4], fever with renal syndrome caused by the Hantaan virus [5], respiratory syncytial virus [6], coronavirus infection COVID-19 [7, 8] and, possibly, gastroenteritis caused by astroviruses [9]. Current research data suggest the efficacy of ribavirin in the treatment of some histological types of nasopharyngeal carcinoma [10, 11], breast [11], lung [12], colorectal cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, malignancies associated with the human papillomavirus (HPV) [13], ovarian carcinoma [14], a number of hemoblastoses [11], and soft tissue sarcoma [15]. Moreover, a positive effect of ribavirin on the severity of addiction to narcotic psychostimulants has been established [16]. However, despite the ever-expanding range of indications for the use of ribavirin in clinical practice, the possibility of its use is limited by severe side effects. The development of adverse reactions may result in decreased adherence to treatment, a reduction in the dosage of the drug, or its complete discontinuation, which affects the effectiveness of pharmacotherapy, increases the risk of developing resistance in viral pathogens and has an unfavorable prognosis for many patients [17-19]. There are several approaches to solving this problem. Presently, a plethora of avenues of investigation are being pursued. These include the utilization of non-conventional routes of parenteral administration of the drug, the introduction of an array of excipients and their combinations as a means to regulate pharmacokinetic parameters, the deployment of targeted delivery systems to guarantee the attainment of targeted effects on specific organs and tissues that are the site of pathogen replication, and numerous others. Given that ribavirin is classified as a class III drug according to the biopharmaceutical classification system (BCS), a promising avenue for modification may be to enhance its penetration through histohematic barriers, prolong its action by increasing mucoadhesion, and augment its affinity for lipophilic structures within the body through the use of suitable polymer-carriers [20].

The aim of this study is to evaluate the existing data on the alteration in the safety profile and efficacy of ribavirin modified with targeted drug delivery systems in the context of both traditional use of this drug and off-label use.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

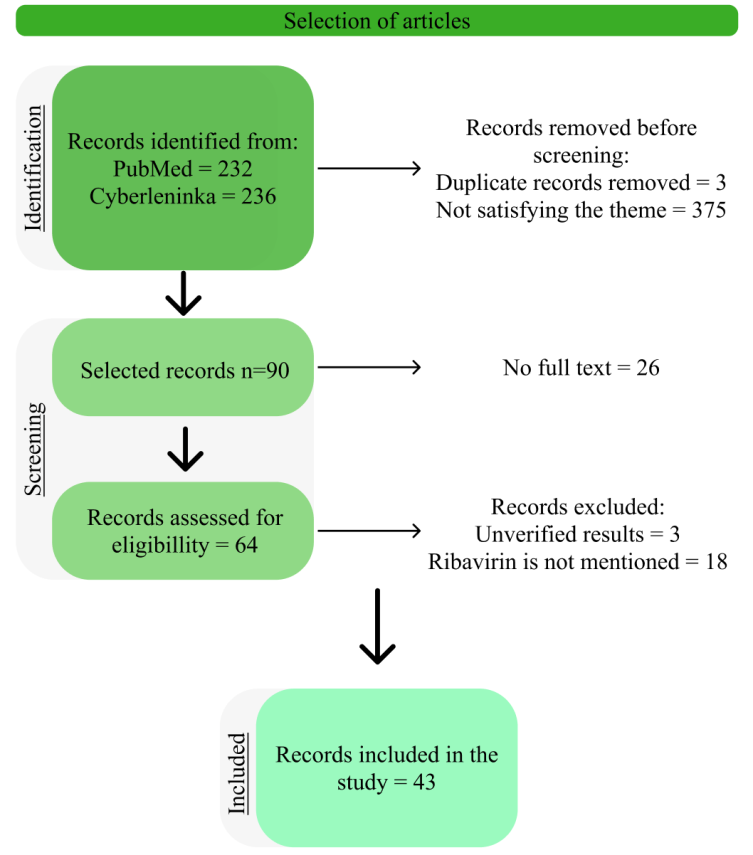

Publications from the international database PubMed and the Russian electronic scientific library Cyberleninka were used as sources of information for the review of scientific literature.

Information was obtained from the PubMed database using the keywords: "delivery systems" and "ribavirin" (49 results); "liposome" and "ribavirin" (9 results); "nanogel" and "ribavirin" (1 result); "nanoparticle" and "ribavirin" (10 results); "drug carriers" and "ribavirin" and "side effects" (12 results); "drug carriers" and "ribavirin" (125 results); "Polymer" and "ribavirin" (26 results).

The following search queries were used in the Cyberleninka electronic library: "ribavirin delivery" (79 results); "ribavirin targeted delivery systems" (57 results); "ribavirin liposomes" (14 results); "ribavirin nanogels" (1 result); "ribavirin polymer" (47 results), "ribavirin conjugates" (38 results). During the analysis, no restrictions were imposed on the "publication date" and "free access to the full text of the publication" indicators.

Inclusion criteria

The following parameters were used as inclusion criteria: the use of ribavirin modified with targeted delivery systems as mono and combination therapy in clinical practice; the use of ribavirin modified with targeted delivery systems in studies conducted on cell and tissue cultures and/or on animals, regardless of species; studies of targeted delivery systems using ribavirin as a model drug.

Exclusion criteria

Studies that do not fit the theme of this review, such as: studies evaluating the incidence of adverse reactions in mono-and combination therapy with ribavirin without the use of targeted delivery systems or using such for another drug; the use of ribavirin as a comparator drug in assessing the efficacy and tolerability of ribavirin analogues and other drugs; studies aimed at efficacy and safety indicators in specific patient groups (such as childhood, chronic renal failure, human immunodeficiency virus infection, recurrent viral hepatitis).

The article uses an assessment of publications by the following parameters: type of study (original research, literature review); object/method used in the study (in vitro testing (using instrumental methods of analysis, cell and tissue cultures), ex vivo, in vivo (studies on laboratory mice, rats, rabbits), studies with the participation of patients, the volume of literature analyzed during the review); the effect achieved during the study; features of the publication methodology (design, key findings, need for further research on the topic, presence of a conflict of interest).

In order to better cover the topic, this paper does not exclude publications that do not fulfill the standard criteria for standard research quality assessment, including the presence of risk of bias, thus allowing for a fuller identification of existing knowledge gaps.

RESULTS

Results of the literature search and the final flowchart of the PRISMA search strategy

According to the results of the analysis, the number of papers meeting the inclusion criteria was 43. Meta-analyses and systematic reviews on the given parameters are absent in the databases under consideration. Among the original studies, in vitro experiments predominate, the largest number of which falls on work with cell and tissue cultures. 100% of authors use small rodents (rats, mice) as experimental animals. Studies involving humans are much less widespread. The analysis of review articles showed that in 100% of cases there is no indication of the methodology of literature selection. The final Flow diagram of the search strategy is presented in fig. 1.

Fig. 1: Final flowchart, the search strategy used to identify studies included in this review is based on PRISMA recommendations

Current status in the scientific literature

In this section, we review the main characteristics of current reviews summarizing data from studies on the use of ribavirin combination and drug delivery systems, their main advantages and limitations. Thus, current review publications address the following aspects: a) the position of ribavirin in the group of antiviral drugs that could be technologically modified to improve the effectiveness of therapy; b) reducing the risk of adverse reactions and increasing the efficacy of therapy.

Thus, Chen R. et al. focus the possibility of enhancing the absorption of the active substance by adding excipients, but the assessment of the risks of adverse reactions associated with an increase in relative bioavailability is not carried out, as well as alternative directions of working with the active substance [21].

Haiyan Guo et al. reviewed the existing strategies for modifying the structure of the active substance, such as: creation of prodrugs; use of isolated L-enantiomer; creation of conjugates with macromolecular compounds and incorporation of the drug into liposomes and niosomes [22]. However, the range of possible modifications is rather limited, and the clinical significance of the described techniques is not fully clear. In the review by Elberry M. H. et al. put forth a proposal to modify ribavirin by incorporating it into nanoparticles. However, the review only includes two potential examples, which do not fully represent the range of modification possibilities [23]. This problem is covered more comprehensively from a pharmaceutical technology perspective in a 2019 review publication, but the main goal of researchers is to improve the results of hepatitis C therapy without addressing the full spectrum of pharmacological activity of ribavirin [24]. It should be noted that a large-scale and comprehensive review by Nader K. et al., addresses the issue of prospects for the use of targeted delivery systems in hepatitis C therapy, including data on the use of liposomes, nanocapsules, nanotubes, dendrimers, fullerenes, but information on the compatibility of these systems with active pharmaceutical substances is not given [25].

Therefore, the present review should provide a comprehensive overview of the technological methods currently available for enhancing the efficacy and safety profile of ribavirin while also elucidating the potential clinical applications of these modifications. The initial stage of this study will entail an examination of the interaction between ribavirin and targeted delivery systems in the context of various pathological conditions. This will be followed by a concise characterisation of the aforementioned systems.

Ribavirin and viral liver damage

In order to optimise the use of ribavirin in the treatment of hepatitis B and C, it is essential to focus on three key target indicators: targeted action on liver cells, reduced extrahepatic toxicity and the possibility of prolonging the pharmacological effect. The principal methodologies employed to address the aforementioned tasks were as follows: an increase in the concentration of the active substance in hepatocytes; modulation of pharmacokinetic parameters; alteration of the physicochemical properties of the molecule, thereby ensuring a reduction in interaction with the targets most susceptible to the toxic effects of ribavirin.

Interest in creating a targeted effect on hepatocytes arose in the mid-1990s. Di Stefano G et al. proposed to use carriers obtained by lactosamination of poly-L-lysine. According to the authors of the study, this terminal modification had antiviral efficacy values comparable to free molecules. Safety indicators were superior to those of unconjugated nucleoside analogues in terms of the incidence of neurotoxic complications [26]. A slightly different approach was implemented by Fiume L. et al. The researchers proposed to bind nucleoside analogues to micelles equipped with a galactosyl fragment. It is assumed that anionic carriers have the highest affinity for hepatocytes. According to in vitro studies, this makes it possible to obtain previously inaccessible liver concentrations [27]. While the aforementioned studies are of historical value as some of the first attempts to modify nucleoside analogues with the goal of reducing the incidence and severity of adverse reactions, it is important to note that at the time, the majority of experiments were focused on other antiviral drugs within this group.

Over time, there has been a growing interest in the potential benefits of introducing structures that are similar to natural carriers in the human body. The development of ribavirin as a prodrug targeting the cotransporting polypeptide sodium taurocholate resulted in a high degree of affinity due to the physiological similarity between the two. The methodology was founded upon the understanding that taurocholate receptors are preferentially expressed in liver cells. The drug was conjugated with six types of bile acids, differing in molecular weight, resulting in selective binding to hepatocytes. A significant reduction in the impact of ribavirin on kidney cells and erythrocytes was observed in studies conducted on mice. The concentration of ribavirin in these cells was found to be reduced by a factor of between 1.8 and 16.7 relative to free ribavirin, depending on the specific modification of the bile acid in question [28].

A detailed comparative analysis was conducted by Hashim F. et al., who outlined modern technological approaches to ribavirin modification. The researchers considered niosomes not only from the standpoint of predicting the effect of targeted delivery systems on the likelihood of adverse reactions but also paid attention to the issues of drug stability. The work involved models with different ratios of excipients and sizes of the resulting vesicles. According to the results of the experiments, niosomes of the composition spen: cholesterol: dicetyl phosphate 4:2:1 were recognized as the most promising. In comparison with other studied modifications in vitro, they demonstrated the most complete and prolonged release of ribavirin. Further testing on rats revealed a sixfold increase in the concentration of the drug in liver cells [29].

An approach based on the inability of erythrocytes to endocytosis and, as a result, the biochemical impossibility of interaction with substances with a high degree of hydrophobicity is widely discussed [30, 31]. One of the most promising areas is the use of polyglycerol adipate and its acyl derivative nanoparticles as carriers [21, 23, 32]. According to the results of in vitro and in vivo work, encapsulation in a homopolymer of lactic acid and arabinogalactan lysine provides prolonged release for a week. Moreover, the release rate during intravenous and intramuscular administration was comparable. In addition, it was found that ribavirin monophosphate encapsulated in a homopolymer has a targeted effect on the liver. The increase in the concentration of ribavirin in the liver compared to an aqueous solution of the free drug was 20%, without demonstrating acute toxicity to erythrocytes or sensitization [22, 23, 33]. However, this approach does not allow for the incorporation of high doses of ribavirin, which is not mentioned when working with lactosylated poly-lysine conjugates [26, 34].

Wohl BM et al. have highlighted the unsatisfactory toxicity indicators of high-molecular-weight carriers. The research data indicate that synthetic methacrylic and vinyl polymers possess independent anti-inflammatory activity against hepatocytes in both viral infections and malignant neoplasms. Nevertheless, despite the synergistic activity of ribavirin and these polymers, a narrow therapeutic index was observed. In order to enhance the safety profile, it has been suggested that polymers with a negative charge, which demonstrate an intracellular antiviral effect and a more favorable therapeutic range, be employed [35].

At the same time, it would be a mistake to assume that the use of carriers can be aimed exclusively at creating a prolonged action of a drug. Despite the widespread use of niosomes as targeted delivery systems, it was found that the release of ribavirin from niosomes does not exceed 5% [22]. In this respect, the question was posed as to the possibility of enhancing the completeness and rate of release of ribavirin from its carrier. In order to address the issue at hand, the utilization of hydrogels with an enhanced lignin concentration (up to 3%) in a gelatin-lignin gel was put forth as a potential solution. Consequently, the degree of release completeness was enhanced [36].

The potential applications of ribavirin in the treatment of liver diseases extend beyond its use as a pharmacotherapy for viral hepatitis. Ribavirin can be employed as an active therapeutic agent in the treatment of viral infections, with a primary localization in the liver. In vivo studies have demonstrated that the use of liposomal forms of ribavirin has a pronounced therapeutic effect on Rift Valley fever in mice. The results of the experiments demonstrated that the concentration of ribavirin administered in an encapsulated form in liver macrophages was five times higher than that of the comparison group. Additionally, the data indicated a reduction in mortality rates associated with a high viral titer [37].

Iron-binding proteins have been recently proposed as a targeted drug delivery system [38]. Given the high affinity of ribavirin for erythrocytes, this technology has attracted interest in the scientific community [22]. An attempt was made to use human hemoglobin as a carrier. According to published data, six to eight ribavirin molecules bind to the carrier hemoglobin. In vitro, this complex was selectively captured by cells expressing the CD163 receptor. The researchers conducted a comparative assessment of the antiproliferative activity of free ribavirin. The indicators were declared equivalent [22, 39]. A comparable result was demonstrated in an in vivo study. The use of hemoglobin as a delivery vehicle ensured greater survival in the studied group of mice and a significantly smaller scale of histologically verified liver necrosis compared to the control group [40]. It has been established that the hemoglobin-ribavirin complex maintains stability and prolonged release in human blood plasma [22, 39]. Table 1 provides a summary of the target effects and delivery systems studied.

Ribavirin in the treatment of lower respiratory tract diseases

Ribavirin is widely used in the treatment of respiratory viral diseases. In order to reduce the incidence of side effects, two fundamentally different approaches have been proposed (table 2).

The initial objective is to combine ribavirin with polymer-carriers. In the study conducted by Riber C. F. et al., the efficacy of high-molecular compounds of methacrylic acid was evaluated in cell and tissue cultures. The antiviral activity of polymers against respiratory syncytial virus, avian influenza virus, and herpes virus was observed. Riber C. F. et al. describe the preservation of ribavirin activity against influenza type A with a reduction in mitochondrial toxicity [41].

The results of studies conducted by Shigeta S. et al. investigating the efficacy of a combination of ribavirin with a polyoxometalate against the influenza type a virus, both in vitro and in vivo, were published. The combination of polyoxometalate and ribavirin demonstrated synergistic and additive effects across a range of ratios [42].

In a study exploring the potential use of ribavirin in the treatment of viral pneumonitis, the feasibility of utilizing negatively charged multilayer liposomes was investigated. The results indicated that the liposomal form of ribavirin exhibited high efficacy in protecting against the influenza virus. The same level of efficacy was not observed in the prevention of herpesvirus infection [43].

A distinct technological methodology was employed in the investigation of aerosolized forms of ribavirin generated via the particle replication method in non-wetting templates (PRINT). The primary objective was to achieve a uniform shape and size for the ribavirin particles. The combination of enhanced physicochemical properties and the ratio of active and auxiliary substances guaranteed not only a high concentration of ribavirin in the fluid of the lungs epithelium in the primary and control groups but also good tolerability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [44].

Use of ribavirin in ophthalmology

Currently, non-traditional routes of ribavirin administration are being actively studied. In particular, it is possible to note the high interest in the use of ribavirin in ophthalmology (table 3).

Table 1: The relationship of excipients and the effect of their compounds with ribavirin in liver pathology

| Ref. | Drug delivery system | Pharmacokinetic results | Pharmacodynamic results | Toxicological results |

| [26] | lactosaminatedpoly-L-lysine | No data | Comparable efficacy | Reduced toxicity |

| [27] | Micelles with a galactosyl fragment | Increased targeting | Higher theuraputic efficacy | Reduced toxicity |

| [28] | bileacids | Increased concentration in hepatocytes | Higher theuraputic efficacy | Reduced nephrotoxicity; Reduced hematotoxicity |

| [29] | niosomes of the composition spen: cholesterol: dicetylphosphate 4:2:1 | Increased concentration in hepatocytes; | Prolongation of therapeutic effect | Increased release rate; |

| [32] | nanoparticles of polyglycerol adipate and its acyl derivative | No data | Comparable efficacy | Less risk of developing hemolytic anemia |

| [21] | nanoparticles of polyglycerol adipate and its acyl derivative | No data | Comparable efficacy | Less risk of developing hemolytic anemia |

| [23] | nanoparticles of polyglycerol adipate and its acyl derivative | No data | Comparable efficacy | Less risk of developing hemolytic anemia |

| [33] | homopolymer of lactic acid and arabinogalactan lysin | Increased concentration in hepatocytes; Extended-release | Higher theuraputic efficacy | Less systemic adverse reactions |

| [22] | homopolymer of lactic acid and arabinogalactan lysin | Increased concentration in hepatocytes; Extended-release | Higher theuraputic efficacy | Less systemic adverse reactions |

| [34] | lactosylatedpoly-lysine | No data | Higher theuraputic efficacy | It is possible to incorporate high doses of the API |

| [35] | methacrylicandvinylpolymers | No data | Synergism of antiviral action; Synergism of antiproliferative action | Less systemic adverse reactions |

| [36] | gelatin-ligningel | Increased completeness of ribavirin release; Increased rate of ribavirin release | Higher theuraputic efficacy | No data |

| [37] | liposomes | No data | Therapeutic effect in early stages of Rift Valley fever | No data |

| [39] | hemoglobin | Extended-release | Preservation of antiproliferative activity | No data |

| [40] | hemoglobin | Extended-release | Higher theuraputic efficacy | Reduced risk of liver necrosis |

Table 2: The relationship of excipients and the effect of their compounds with ribavirin in lower respiratory tract pathology

| Ref. | Drug delivery system | Pharmacodynamic results | Toxicological results |

| [41] | Methacrylic acid-based polymers | Expanded antiviral activity | Reduced toxicity |

| [42] | polyoxometalate | Synergism; Additive effect | Less systemic adverse reactions |

| [43] | Negatively charged multilamellar liposomes | Preventive effect against influenza virus | Less systemic adverse reactions |

| [44] | Particle Replication Technology in Non-Wetting Templates | Improved tolerability in a group of patients with COPD | Reduced toxicity |

Table 3: The relationship between excipients and the effect of their compounds with ribavirin in ophthalmological practice

| Ref. | Drug delivery system | Pharmacokinetic results | Pharmacodynamic results | Toxicological results |

| [45] | Multiple microemulsions of the w/o/w type | Increased bioavailability; Increased bioadhesion; Prolonged release | Higher theuraputic efficacy | No data |

| [46] | Pharmasolve | Increased permeability; | Higher theuraputic efficacy | No irritating effect |

| [47] | Gelucire44/14 | Increased permeability; | Higher theuraputic efficacy | No irritating effect |

The key limitation of the use of drugs is low bioavailability caused by the peculiarities of penetration of molecules through the cornea. As a solution to this problem, Ibrahim M. M. et al. proposed to use a multiple microemulsion of the i\o\v type with a droplet size of 10 nm. According to the researchers, the microemulsion has high bioadhesion, provides a threefold increase in the bioavailability of ribavirin and prolonged release during the day [45].

A study of permeability and tolerability parameters was carried out by Li X. et al. Ribavirin was considered in combination with Pharmasolve™ (N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone) as a model compound. According to the results, the increase in corneal permeability for ribavirin was 4.04 with no irritating effect of Pharmasolve™ at a concentration of 10 percent and below [46]. An example of a more economical absorption enhancer for ophthalmic drugs was the use of Gelucire® 44/14. The study examined the use of this excipient in the delivery system of six model drugs, including ribavirin. In the concentration range of the absorption enhancer from 0.05% to 0.1%, an increase in the permeability coefficient for ribavirin by 6.47 was demonstrated. No irritating effect on the excised rabbit cornea was detected either in the specified concentration range or with a fourfold increase in the technologically standard content of Gelucire® 44/14 [47]. However, it should be noted that the advisability of using ribavirin in ophthalmology remains debatable. There are reports in scientific literature on the development of retinal damage during hepatitis C therapy using ribavirin [48]. At the same time, a number of studies indicate the absence of a relationship between the use of ribavirin in mono and combination therapy and the development of this side effect [49, 50].

Ribavirin and pathologies of the nervous system

Due to the broad spectrum of antiviral activity of ribavirin, the global scientific community has become interested in studying the possibility of its use in the treatment of viral encephalitis. It was found that this drug is not able to penetrate the blood-brain barrier. However, according to in vivo studies, the use of an appropriate carrier can increase the degree to which the drug reaches brain tissue. A complex comprising alpha-cyclodextrin was put forth as a potential solution. The level of penetration into tissues was not associated with the severity of the condition of the studied objects or the dosage of the drug [51].

The use of drug delivery systems can facilitate the entry of ribavirin into cells of the peripheral nervous system. In particular, studies were conducted on a carrier based on lipid nanovesicles containing procaine and ribavirin, which demonstrated satisfactory results [52].

An alternative approach to facilitating transport through the blood-brain barrier may be to alter the route of administration. At present, the administration of drugs via the nasal route to the brain is being introduced into clinical practice. In vivo experimental conditions demonstrated that the penetration rate of free ribavirin achieved 35% penetration when administered intranasally. Ribavirin has been observed to reach structures such as the basal ganglia and hippocampus [53]. Therefore, intranasal administration does not necessitate substantial modification of the molecular structure of the active substance. An increase in bioavailability can be achieved by enhancing mucoadhesion and optimizing the disaggregation of drug particles, which enables the overcoming of the typical BBB permeability issues associated with small hydrophilic substances. The established targeted effect of lecithin on organs rich in lipophilic components in combination with alpha-cyclodextrin provides a targeted effect on the brain compared to the injection of an aqueous solution [54].

The administration of ribavirin in microparticles form with poloxamer 188 demonstrates the expected high absorption of substances when administered intranasally. As posited by Vasa D. M. et al., the initial gelation process results in a reduction in the rate of release from the compound in comparison to free ribavirin. Subsequently, when the excised mucosa was subjected to the same treatment, the release from the complexes increased. The researchers posit that in this case, the role of poloxamer 188 is not merely that of a carrier but also entails an independent interaction with the epithelium of the mucous membranes [55-58]. Furthermore, intranasal administration of ribavirin exhibits distinctive pharmacokinetic characteristics. A comparative analysis of classical absorption enhancers, including chitosan and mannitol and alpha-cyclodextrin, revealed a higher level of ribavirin accumulation in all regions of the brain for the latter. The combination of ribavirin with alpha-cyclodextrin was observed to exhibit specific flowability and particle size characteristics [54]. A comparative analysis of the interaction between the route of administration, the delivery system and its effects are presented in table 4.

Comparative analysis of the impact of individual types of drug delivery systems

In this section, we review the drug delivery systems investigated in combination with ribavirin, as well as their main biological effects, prospects and feasibility of use [64]. This section does not address the use of individual excipients in different clinical applications of ribavirin.

Table 4: The relationship of excipients and the effect of their compounds with ribavirin in pathologies of the nervous system

| Ref. | Drug delivery system | Pharmacokinetic results | Pharmacodynamic results | Toxicological results |

| [51] | alpha-cyclodextrin | Increased penetration of ribavirin into brain tissue | Higher theuraputic efficacy | Less systemic adverse reactions |

| [52] | lipid nanovesicles containing procaine | Penetration of ribavirin into tissues of the peripheral nervous system | Higher theuraputic efficacy | No data |

| [53] | «nose to brain» | Penetrationthroughthe BBB | Higher theuraputic efficacy | Less systemic adverse reactions |

| [54] | «nose to brain», lecithin in combination with alpha-cyclodextrin | Penetration through the BBB; Accumulation of ribavirin in all parts of the brain | Targeted action on brain cells; | Less systemic adverse reactions |

| [55] | Poloxamer 188 | Decreased release rate; Increased completeness of release; Mucoadhesion |

Higher theuraputic efficacy | No data |

Liposomes and niosomes

Liposomes are biocompatible, non-immunogenic spherical vesicles approved by the FDA for medical use [65-67]. The advantages of this form include increased loading of the active ingredient, the possibility of targeted action and prolongation of the effect [68]. Currently, liposomes can be made from phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylglycerol, phosphatidylglycerol, cholesterol and a variety of other lipophilic compounds, giving a wide range of formulation options to dosage form developers [69, 70]. This dosage form is extensively studied, due to which there are many strategies to incorporate active pharmaceutical substances into the liposomal carrier, creating improved dosage forms such as immunoliposomes, aptamer-liposomes and peptide-liposomal conjugates [66]. Interestingly, liposomes can be combined with other high-tech drug delivery systems, such as nanoparticles [71]. At the same time, the main disadvantages of this drug delivery system are the technical difficulty of obtaining stable vesicles of uniform size [72], as well as relatively rapid excretion from the bloodstream by macrophages [73].

It should be noted that many liposomal forms of drugs have been introduced into clinical practice in various nosologies, including, for example, AmBisome (antifungal drug amphotericin), Myocet (doxorubicin-antitumor agent) and DepoDur (narcotic analgesic morphine) [74] and a significant list of names is at the stage of clinical trials [75].

Niosomes are small lipid vesicles containing surfactants, which makes them similar to microemulsions [76]. The main advantages of this drug delivery system include the ability to penetrate through the skin [77, 78], suitability for loading hydrophilic and hydrophobic substances [79], prolonged release of the incorporated substance, the presence of an independent pharmacological effect (antibacterial) [80-83], selective cytotoxicity against tumor cells [81], reducing the risk of adverse reactions characteristic of the specific active pharmaceutical substance [84], the ability to significantly increase the biodosage capacity of the drug [85, 86]. A potential disadvantage of niosomes is the induction of an immune response. On the one hand, this phenomenon allows their use as a vaccine adjuvant, on the other hand, in the context of the present study, increases the risk of allergic reactions [87].

It can be posited that the utilisation of ribavirin in liposomal and niosomal forms is a promising avenue of research, given that these drug delivery systems facilitate the desired alterations in pharmaco-and toxicokinetic parameters.

Polymeric carriers

Current developments in modified dosage forms of ribavirin include its incorporation into in situ systems (ISS). This type of targeted delivery systems responds to a specific physiological stimulus such as, for example, temperature or body fluids [88, 89], followed by a sol-gel transition [90]. The key component of these systems is the polymer matrix formulator, which determines the mechanism of action of the system and the release parameters of the active pharmaceutical substance [91]. The active ingredient, in turn, is able to influence the phase transition parameters. At the same time, it should be noted that for ribavirin such influence is minimal [92].

ISS play a special role in nose-to-brain drug delivery, including in combination with niosomes [93], providing the highest bioavailability [94] and prolonged release due to the gel structure and mucoadhesive properties [95]. The advantages of ISS also include non-invasive administration and the possibility of combining different polymers and active pharmaceutical substances. This allows this system to be used in a wide range of pathological conditions, from infectious processes [96] to brain neoplasms [97]. The main disadvantage of stimulus-sensitive in situ systems is the difficulty of standardization. Despite this, the feasibility of ISS for ribavirin has been sufficiently explored. According to the results of in vitro and in vivo studies, combinations with chitosan formate [98], gellan gum and poloxamer [99] allow not only to achieve the above-mentioned favorable effects but also to overcome the main difficulty of nose-to-brain delivery-mucociliary clearance [100].

Furthermore, the utilisation of lactic acid homopolymer is becoming an increasingly significant factor. The advantages of this polymer include biocompatibility and biodegradability, as well as the potential for modifying its physical properties and behavior within the body through copolymerization with other compounds [101-103]. Another noteworthy attribute is its potential for use as the primary component in multiple systems, including thermosensitive gels [104] and solvent-responsive gels [105], as well as nanoparticles [106]. It is noteworthy that lactic acid homopolymer is employed in clinical settings. One such example is the drug Atridox, a prolonged-acting antibiotic [107]. The disadvantages associated with this polymer can be attributed to its advantageous properties. Consequently, the ultimate characteristics and, consequently, the efficacy of the composition will be largely contingent upon the presence of additional excipients.

Nanoparticles

Nanoparticles are defined as particles with a diameter of less than 100 nm, comprising a diverse range of chemical compositions [108]. With regard to the combination of ribavirin with polyglycerol adipate, an investigation was conducted on the efficacy of the latter alone. It is a biocompatible and biodegradable aliphatic glycerol polyester, which is widely known for its use as a targeted drug delivery vehicle capable of self-assembly [109, 110]. The advantages of polyglycerol adipate include increased bioavailability and reduced hepatotoxicity of incorporated active pharmaceutical substances. Additionally, it can be modified by other molecules, such as other polymers, including polycaprolactone, and lipophilic compounds, specifically cholesterol and tocopherol. This allows for the modification of the release profile of active ingredients [111-113]. Notwithstanding the aforementioned advantages, data on the utilization of this compound, in conjunction with its combination with ribavirin, in humans remain scarce.

Functionalization with biomolecules

Bile acids are biocompatible, non-toxic amphiphilic steroidal molecules used mainly to increase the bioavailability of drugs [114, 115] by increasing their stability and intensifying their penetration through mucous membranes [116]. Cholic acid, deoxycholic acid, chenodeoxycholic acid and glycocholic acid with various modifications are most commonly used [117, 118]. As a component of drug delivery system can be presented as conjugates with active ingredients, bilosomes or hybrid nanoparticles with intrinsic pharmacological activity [119]. Compared to liposomes and niosomes, bilosomes are more stable, including in the gastrointestinal tract [125], hence the high interest in their use as oral drug modifiers [120, 121]. The possibility of targeting different body structures such as the brain [122], liver [123] or large intestine [124] is also worthy of mention. The main limitation of bile acids is the fact that their role in the body is not fully understood and, as a consequence, makes it difficult to assess the behaviour of such systems in the body, making it difficult to move from in vitro experiments to clinical studies [125, 126].

This review proposes an alternative biomolecule as a potential targeted delivery system. The majority of studies addressing this issue were conducted over a decade ago. In recent years, there has been a resurgence of interest in this field among the scientific community. In particular, hemoglobin has been considered as a pH-sensitive nanocarrier with targeting properties against tumor cells [127]. However, due to the insufficient number of studies, the primary significance of this information is limited to its historical value as one of the stages in the development of the field. In light of these considerations, the functionalization of ribavirin with biomolecules is constrained by a number of factors, including ethical considerations, which impede further advancement.

As an intermediate conclusion for this section, a comparative analysis of the mentioned systems was performed (table 5).

Table 5: Comparative analysis of ribavirin targeted delivery systems

| Class | Drug delivery system | Advantages | Disadvantages | Clinical appropriateness | Ref. |

| Lipid derivatives | liposomes | Biocompatibility; Low allergic potential; increased loading of active ingredient; possibility of targeted action; prolongation of effect; possibility of combination with other systems | technical difficulty of manufacture; rapid elimination from the bloodstream |

Clinically appropriate use: FDA approval, availability of representatives in clinical practice | [65-74] |

| Niosomes | Possibility of skin penetration; suitability for loading substances of different nature; prolonged release; selective cytotoxicity for tumour cells; reduced risk of adverse reactions; increased bioavailability | Allergic potential | Application is appropriate with limitations | [77-79, 81, 84, 86, 87] | |

| Polymers | ISS | Prolonged release; non-invasive administration | Challenges of standardization | Application is appropriate with limitations | [91, 94, 95] |

| Lactic acid homopolymer | Biocompatibility and biodegradability; modifiability; prolonged effect | Influence of other components of the formulation on the characteristics | Clinically appropriate use: FDA approval, availability of representatives in clinical practice | [88, 102, 103, 107] | |

| Nanoparticles | Polyglycerol adipate | Biocompatibility; increased bioavailability; reduced hepatotoxicity; modifiability; | There is limited data on the use of this compound in humans | Insufficient data to be able to apply | [109-113] |

| Biomolecules | bile acids | Biocompatibility; increased bioavailability; high stability; ability to target different body structures | There is insufficient data on the mechanism of action | Application is appropriate with limitations | [114-116, 120, 123-126] |

| haemoglobin | Targeting action | Poorly researched | Insufficient data to be able to apply | [128] |

Thus, we can conclude that despite the wide range of possible modifications of ribavirin using directed delivery systems, as well as significant interest in these dosage forms in recent years, liposomes, niosomes, ISS and bilosomes are the most studied and promising for use in real clinical practice.

DISCUSSION

Modern scientific literature offers many ways to solve pharmaco-and toxicokinetic problems that arise during ribavirin therapy. However, most studies are still limited to in vitro experiments. More dynamically developing areas are the modification of ribavirin for use in ophthalmology and in pathology of the nervous system. At the moment, this vector has the smallest number of publications, but they have more convincing results and high-quality design of the studies. Regardless of the date and language of publication, a critical assessment of existing articles with a well-developed methodology is currently lacking.

Table 6: Classification summary table for the publications analyzed in this paper

| Ref. | Type | Methods | Еffects | Special features |

| [26] | Research | In vivo: mice | Targeted effects on the liver by intramuscular injection | The conjugate efficacy for ribavirin was lower than that of other nucleoside analogues, emphasis of development on adenine arabinoside monophosphate |

| [27] | Review | 78 publications from 1949 to 1994 | Targeted effects. Reduction in the frequency of side effects from the nervous system | The study methodology, inclusion and exclusion criteria are not described |

| [28] | Research | In vitro: NTCP-HEK293 cell culture; Human whole blood; In vivo: Mice | Targeting liver receptors, reducing ribavirin accumulation in erythrocytes | Increased ability to diffuse conjugates leads to an increased risk of haemolytic effects |

| [29] | Research | Ex vivo: Liver of female rats given ribavirin | Increased bioavailability of low-dose ribavirin, reduced extrahepatic toxicity | Need for further study of the safety and efficacy profile |

| [32] | Research | In vitro using HPLC and NMR | Reduced erythrocyte uptake of ribavirin | No assessment of biorelevance parameters |

| [21] | Review | 156 publications for the period from 2000 to 2020 | Modulation of pharmacokinetics by nanoparticles | The study methodology, inclusion and exclusion criteria are not described |

| [23] | Review | 70 publications from 1976 to 2017 | Reduced incidence of adverse drug reactions with the use of lipid nanoparticles | The study methodology, inclusion and exclusion criteria are not described |

| [33] | Research | In vivo: Mice; In vitro: HepG2 cell culture |

Targeted effects on liver cells and prolonged release | Targeted effects of nanoparticles on liver cells have been convincingly demonstrated |

| [22] | Review | 126 publications from 1976 to 2014 | Reducing the likelihood of ribavirin-induced haemolyticanaemia | The study methodology, inclusion and exclusion criteria are not described. Consistent and comprehensive presentation of the application of topical ribavirin targeted delivery systems |

| [34] | Review | 71 publications from 1984 to 2004 | Cumulative characterisation of targeted delivery systems for liver targeting | The methodology of the study inclusion and exclusion criteria are not described. The material is visually clear ands pecifically presented |

| [35] | Research | In vitro: HuH7 cell culture; RAW 264.7 cell culture |

Reduction of ribavirin toxicity, prolongation of therapeutic effect | The prospect of using negatively charged polymer-carriers in improving technological processes and increasing the requirements for standartizationation of macromolecules has been taken into account |

| [36] | Research | In vitro: Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) |

Increased completeness and rate of release of ribavirin | The study target is the controlled achievement of rapid and short-term pharmacological effects |

| [37] | Research | In vivo: mice | Increased efficacy of low-dose ribavirin therapy | Limitations of use include effectiveness only as a means of prevention or in the early stages of the disease |

| [39] | Research | In vitro: Human and mouse blood plasma; Cell cultures of cell types: HepG2; AML12; CHO/CD163 |

Synthesis and evaluation of the stability and efficacy of a biocompatible ribavirin carrier | Limitations: the conjugate is suitable for intravenous administration only; use may be appropriate in cases of acute viral infection or relapse prevention |

| [40] | Research | In vitro; ex vivo: mouse liver cells and macrophages | Increased clinical efficacy of low-dose HRC 203 relative to high-dose free ribavirin | It is difficult to predict how applicable the result is to individuals |

| [41] | Research | In vitro: Cell and tissue cultures of types: Vero; A549; HeLa | Increased antiviral activity of ribavirin by regulating the molecular weight of the carrier polymer | A difference in the efficacy of ribavirin in combination with polymers of different molecular weights was found against several viruses |

| [42] | Research | In vitro: MDCK-type cells; in vivo: mice | Increased antiviral efficacy of ribavirin | Significant synergism was observed in the ratio of active ingredient to excipients 1:16 |

| [43] | Research | In vivo: mice | Increased efficacy of liposome-encapsulated ribavirin in mono-and combination therapy | Further studies are required to be able to evaluate the clinical significance of multilamellar liposome application |

| [44] | Clinical trial | Men and women from 18 to 65 years old | Improved tolerability of ribavirin when administered by inhalation | Double-blind placebo-controlled study |

| [45] | Research | In vivo: rabbits | Increased penetration of active substances through the cornea | The results of the study can be projected to other drugs with high water solubility |

| [46] | Research | In vivo: rabbits | In the investigated concentration range Pharmasolve™ does not cause irritating effect on the cornea and significantly enhances the penetration of substances through it | The main focus of the study was Pharmasolve™, with ribavirin used as a model drug |

| [47] | Research | In vivo: rabbits | Gelucire® 44/14 increases transcorneal permeability does not cause irritation in ophthalmic applications | The main focus of the study was Gelucire® 44/14, with ribavirin used as a model drug |

| [51] | Research | In vivo: mice; ex vivo: mice brain |

Possibility of ribavirin penetration through the blood-brain barrier | According to the conclusions of the studies themselves, no other publications reporting an advantage of alpha-cyclodextrin in transporting pharmacologically active substances to the brain were identified |

| [52] | Research | In vivo: rats | Nanovesicles that optimally incorporate ribavirin and have satisfactory release were obtained | There is a possibility that procaine plays a significant role in delivery to the nervous system. |

| [53] | Research | In vitro: rabbit nasal mucosa model; In vivo: rats |

Increased bioavailability of ribavirin with nose-to-brain administration regimen | Key area of research: facilitating the use of substances in veterinary practice through intranasal administration |

| [54] | Research | Ex vivo: rabbit nasal mucosa; in vivo: rats | Increased bioavailability of ribavirin with nose-to-brain administration regimen | The study emphasises the role of excipients in regulating the bioavailability of ribavirin microparticles |

| [55] | Research | In vitro: Franz diffusion cell; bovine nasal mucosa model | The use of poloxamer 188 enhances the permeability and mucoadhesion of the preparation | The results of the study can be projected to other nose-to-brain medications |

| [59] | Review | 72 publications from 1906 to 2014 | Ribavirin conjugates are presented as an example of reduced drug toxicity by modification of the delivery system | The study methodology, inclusion and exclusion criteria are not described. The publications of an educational nature |

| [60] | Review | 27 publications from 1998 to 2008 | Phospholipid nanoparticles of ribavirin are cited as an example of a promising area of drug development | The study methodology, inclusion and exclusion criteria are not described. The publications of an educational nature |

| [61] | Research | In vitro: NMR1H and 13C spectroscopy; Mass spectral analysis | Presumably, the high degree of release of ribavirin from conjugates | Requires further in vitro and in vivo studies |

| [62] | Research | In vitro: pH meter; coaxial rotational viscometer; mucin model; Franz diffusion cell; | Achieving optimum values of mucoadhesion, retention rate, physiological pH value | Requires further in vivo study |

| [63] | Clinicalt rial | 60 patients with chronic hepatitis C, aged 18 to 50 years | The use of liposomal forms of ribavirin has been characterised as highly effective | Conflict of interest |

The next pressing problem in this area of research is the fact that most of the experiments were conducted in vitro using cell and tissue cultures. As a consequence, it is possible that unexpected adverse reactions, including those associated with chronic toxicity, may occur in attempts at research involving human subjects.

The current clinical trials of ribavirin concentrate on the assessment of its efficacy when used in conjunction with other pharmaceutical agents, as well as the potential for its use in the treatment of a range of pathologies beyond the established scope of indications [128-131]. In contrast, clinical studies of drug delivery systems are relatively dispersed and predominantly oriented towards enhancing the efficacy of treatment for diseases that are not entirely curable (e. g., malignant neoplasms) [132, 133]. It is noteworthy that a number of alternative systems remain pertinent, including the extensively investigated liposomes and the comparatively recent nanoparticles [133, 134]. It is therefore possible that the use of directed delivery systems will ensure the fulfilment of the main objectives voiced in clinical trials in recent years, namely, to broaden the spectrum of ribavirin indications, reduce the risk of adverse reactions and increase treatment efficacy.

CONCLUSION

The utilization of targeted delivery systems represents a promising avenue for enhancing the safety profile and efficacy of ribavirin. Modern science offers a plethora of modifications, including conjugation with polyamino acid residues, amino sugars, and proteins, as well as the latest nanovesicles, nanoparticles, and in situ systems. A significant number of proposed solutions allow for targeted action on specific cells (in particular, liver cells macrophages), a reduced likelihood of severe dose-dependent side effects (usually hematotoxic), reduced sensitizing and local irritant effects, increased completeness of drug release and regulation of its rate, and the preservation of the antiviral and antiproliferative effects of ribavirin in relatively low doses. The majority of studies are conducted in vitro or ex vivo. The least studied, yet promising, areas for further development include enhancing the penetration of ribavirin through the cornea, reducing its adverse effects on the retina; increasing the completeness and speed of ribavirin transport through the blood-brain barrier, achieving high concentrations of the drug in brain cells. Potential avenues for further investigation include the use of auxiliary substances and technological solutions to facilitate prolonged release, the enhancement of mucoadhesion, and the combination with lipophilic polymer components.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization-Mikhel I. B., Bakhrushina E. O.; investigation-Mikhel I. B., Titova S. A.; resources-Mikhel I. B., Titova S. A., Stepanova O. I.; data curation-Bakhrushina E. O., Krasnyuk I. I. (jr.), Smolyarchuk E. A., Krasnyuk I. I.; writing—original draft preparation-Mikhel I. B., Titova S. A; writing—review and editing-Bakhrushina E. O., Smolyarchuk E. A., Krasnyuk I. I.; project administration-Mikhel I. B., Bakhrushina E. O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTS

All authors have none to declare

REFERENCES

Mejer N, Galli A, Ramirez S, Fahnøe U, Benfield T, Bukh J. Ribavirin inhibition of cell-culture infectious hepatitis C genotype 1-3 viruses is strain-dependent. Virology. 2020 Jan 15;540:132-40. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2019.09.014, PMID 31778898.

Kamar N, Abravanel F, Behrendt P, Hofmann J, Pageaux GP, Barbet C. Ribavirin for hepatitis E virus infection after organ transplantation: a large European retrospective multicenter study. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 Aug 22;71(5):1204-11. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz953, PMID 31793638.

Salam AP, Duvignaud A, Jaspard M, Malvy D, Carroll M, Tarning J. Ribavirin for treating lassa fever: a systematic review of pre-clinical studies and implications for human dosing. PLOS Negl Trop Dis. 2022 Mar 30;16(3):e0010289. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0010289, PMID 35353804, PMCID PMC9000057.

Eberhardt KA, Mischlinger J, Jordan S, Groger M, Gunther S, Ramharter M. Ribavirin for the treatment of lassa fever: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2019 Oct;87:15-20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2019.07.015, PMID 31357056.

Mayor J, Engler O, Rothenberger S. Antiviral efficacy of ribavirin and favipiravir against hantaan virus. Microorganisms. 2021 Jun 15;9(6):1306. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9061306, PMID 34203936, PMCID PMC8232603.

Tejada S, Martinez Reviejo R, Karakoc HN, Pena Lopez Y, Manuel O, Rello J. Ribavirin for treatment of subjects with respiratory syncytial virus-related infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Adv Ther. 2022 Sep;39(9):4037-51. doi: 10.1007/s12325-022-02256-5, PMID 35876973.

Poulakou G, Barakat M, Israel RJ, Bacci MR, Virazole Collaborator Group for COVID-19 Respiratory Distress. Ribavirin aerosol in hospitalized adults with respiratory distress and COVID-19: an open-label trial. Clin Transl Sci. 2023 Jan;16(1):165-74. doi: 10.1111/cts.13436, PMID 36326174, PMCID PMC9841304.

Unal MA, Bitirim CV, Summak GY, Bereketoglu S, Cevher Zeytin I, Besbinar O. Ribavirin shows antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2 and downregulates the activity of TMPRSS2 and the expression of ACE2 in vitro. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2021 May;99(5):449-60. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-2020-0734, PMID 33689451.

Janowski AB, Dudley H, Wang D. Antiviral activity of ribavirin and favipiravir against human astroviruses. J Clin Virol. 2020 Feb;123:104247. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2019.104247, PMID 31864069, PMCID PMC7034780.

Huq S, Casaos J, Serra R, Peters M, Xia Y, Ding AS. Repurposing the FDA-approved antiviral drug ribavirin as targeted therapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2020 Sep;19(9):1797-808. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-19-0572, PMID 32606016.

Casaos J, Gorelick NL, Huq S, Choi J, Xia Y, Serra R. The use of ribavirin as an anticancer therapeutic: will it go viral? Mol Cancer Ther. 2019 Jul;18(7):1185-94. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-18-0666, PMID 31263027.

Zhu S, Han X, Yang R, Tian Y, Zhang Q, Wu Y. Metabolomics study of ribavirin in the treatment of orthotopic lung cancer based on UPLC-Q-TOF/MS. Chem Biol Interact. 2023 Jan 25;370:110305. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2022.110305, PMID 36529159.

Burman B, Drutman SB, Fury MG, Wong RJ, Katabi N, Ho AL. Pharmacodynamic and therapeutic pilot studies of single-agent ribavirin in patients with human papillomavirus-related malignancies. Oral Oncol. 2022 May;128:105806. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2022.105806, PMID 35339025, PMCID PMC9788648.

Wambecke A, Laurent Issartel C, Leroy Dudal J, Giffard F, Cosson F, Lubin Germain N. Evaluation of the potential of a new ribavirin analog impairing the dissemination of ovarian cancer cells. PLOS One. 2019 Dec 11;14(12):e0225860. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0225860, PMID 31825993, PMCID PMC6905583.

Zhang Q, Yang R, Tian Y, Ge S, Nan X, Zhu S. Ribavirin inhibits cell proliferation and metastasis and prolongs survival in soft tissue sarcomas by downregulating both protein arginine methyltransferases 1 and 5. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2022 Jul;131(1):18-33. doi: 10.1111/bcpt.13736, PMID 35470570.

Petkovic B, Kesic S, Pesic V. Critical view on the usage of ribavirin in already existing psychostimulant-use disorder. Curr Pharm Des. 2020;26(4):466-84. doi: 10.2174/1381612826666200115094642, PMID 31939725, PMCID PMC8383468.

Reddy KR, Nelson DR, Zeuzem S. Ribavirin: current role in the optimal clinical management of chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2009 Feb;50(2):402-11. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.11.006, PMID 19091439.

Shiffman ML. What future for ribavirin? Liver Int. 2009 Jan;29 Suppl 1:68-73. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01936.x, PMID 19207968.

Barrail Tran A, Goldwirt L, Gele T, Laforest C, Lavenu A, Danjou H. Comparison of the effect of direct-acting antiviral with and without ribavirin on cyclosporine and tacrolimus clearance values: results from the ANRS CO23 CUPILT cohort. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2019 Nov;75(11):1555-63. doi: 10.1007/s00228-019-02725-x, PMID 31384986.

Preston SL, Drusano GL, Glue P, Nash J, Gupta SK, McNamara P. Pharmacokinetics and absolute bioavailability of ribavirin in healthy volunteers as determined by stable-isotope methodology. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999 Oct;43(10):2451-6. doi: 10.1128/AAC.43.10.2451, PMID 10508023, PMCID PMC89499.

Chen R, Wang T, Song J, Pu D, He D, Li J. Antiviral drug delivery system for enhanced bioactivity, better metabolism and pharmacokinetic characteristics. Int J Nanomedicine. 2021 Jul 22;16:4959-84. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S315705, PMID 34326637, PMCID PMC8315226.

Guo H, Sun S, Yang Z, Tang X, Wang Y. Strategies for ribavirin prodrugs and delivery systems for reducing the side-effect hemolysis and enhancing their therapeutic effect. J Control Release. 2015 Jul 10;209:27-36. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.04.016, PMID 25883028.

Elberry MH, Darwish NH, Mousa SA. Hepatitis C virus management: potential impact of nanotechnology. Virol J. 2017 May 2;14(1):88. doi: 10.1186/s12985-017-0753-1, PMID 28464951, PMCID PMC5414367.

Abd Ellah NH, Tawfeek HM, John J, Hetta HF. Nanomedicine as a future therapeutic approach for hepatitis C virus. Nanomedicine (Lond). 2019 Jun;14(11):1471-91. doi: 10.2217/nnm-2018-0348, PMID 31166139.

Nader K, Shetta A, Saber S, Mamdouh W. The potential of carbon-based nanomaterials in hepatitis C virus treatment: a review of carbon nanotubes, dendrimers and fullerenes. Discov Nano. 2023 Sep 16;18(1):116. doi: 10.1186/s11671-023-03895-5, PMID 37715929, PMCID PMC10505122.

Di Stefano G, Busi C, Mattioli A, Fiume L. Selective delivery to the liver of antiviral nucleoside analogs coupled to a high molecular mass lactosaminated poly-L-lysine and administered to mice by intramuscular route. Biochem Pharmacol. 1995 Jun 16;49(12):1769-75. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(95)00020-z, PMID 7541203.

Fiume L, Busi C, Di Stefano GS, Mattioli A. Targeting of antiviral drugs to the liver using glycoprotein carriers. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 1994;14(1):51-65. doi: 10.1016/0169-409X(94)90005-1.

Dong Z, Li Q, Guo D, Shu Y, Polli JE. Synthesis and evaluation of bile acid-ribavirin conjugates as prodrugs to target the liver. J Pharm Sci. 2015 Sep;104(9):2864-76. doi: 10.1002/jps.24375, PMID 25645375, PMCID PMC4522399.

Hashim F, El-Ridy M, Nasr M, Abdallah Y. Preparation and characterization of niosomes containing ribavirin for liver targeting. Drug Deliv. 2010 Jul;17(5):282-7. doi: 10.3109/10717541003706257, PMID 20350052.

Schekman R, Singer SJ. Clustering and endocytosis of membrane receptors can be induced in mature erythrocytes of neonatal but not adult humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73(11):4075-9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.11.4075.

Rothen Rutishauser BM, Schurch S, Haenni B, Kapp N, Gehr P. Interaction of fine particles and nanoparticles with red blood cells visualized with advanced microscopic techniques. Environ Sci Technol. 2006;40(14):4353-9. doi: 10.1021/es0522635, PMID 16903270.

Abo Zeid Y, Irving W, Thomson B, Mantovani G, Garnett M. P19: ribavirin-boronic acid loaded nanoparticles: a possible route to improve hepatitis C treatment. J Viral Hepat. 2013;20(s3):26-7. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12166_18.

Ishihara T, Kaneko K, Ishihara T, Mizushima T. Development of biodegradable nanoparticles for liver-specific ribavirin delivery. J Pharm Sci. 2014;103(12):4005-11. doi: 10.1002/jps.24219, PMID 25335768.

Virovic L, Wu CH, Konishi M, Wu GY, Wu GY. Novel delivery methods for treatment of viral hepatitis: an update. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2005 Jul;2(4):707-17. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2.4.707, PMID 16296795.

Wohl BM, Smith AA, Jensen BE, Zelikin AN. Macromolecular (pro) drugs with concurrent direct activity against the hepatitis C virus and inflammation. J Control Release. 2014 Dec 28;196:197-207. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.09.032, PMID 25451544.

Chiani E, Beaucamp A, Hamzeh Y, Azadfallah M, Thanusha AV, Collins MN. Synthesis and characterization of gelatin/lignin hydrogels as quick release drug carriers for ribavirin. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023 Jan 1;224:1196-205. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.10.205, PMID 36309240.

Kende M, Alving CR, Rill WL, Swartz GM Jr, Canonico PG. Enhanced efficacy of liposome-encapsulated ribavirin against rift valley fever virus infection in mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985 Jun;27(6):903-7. doi: 10.1128/AAC.27.6.903, PMID 4026264, PMCID PMC180183.

Bialasek M, Kubiak M, Gorczak M, Braniewska A, Kucharzewska Siembieda P, Krol M. Exploiting iron-binding proteins for drug delivery. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2019 Oct;70(5). doi: 10.26402/jpp.2019.5.03, PMID 31889039.

Brookes S, Biessels P, Ng NF, Woods C, Bell DN, Adamson G. Synthesis and characterization of a hemoglobin-ribavirin conjugate for targeted drug delivery. Bioconjug Chem. 2006 Mar-Apr;17(2):530-7. doi: 10.1021/bc0503317, PMID 16536487.

Levy GA, Adamson G, Phillips MJ, Scrocchi LA, Fung L, Biessels P. Targeted delivery of ribavirin improves outcome of murine viral fulminant hepatitis via enhanced anti-viral activity. Hepatology. 2006 Mar;43(3):581-91. doi: 10.1002/hep.21072, PMID 16496340, PMCID PMC7165489.

Riber CF, Hinton TM, Gajda P, Zuwala K, Tolstrup M, Stewart C. Macromolecular prodrugs of ribavirin: structure-function correlation as inhibitors of influenza infectivity. Mol Pharm. 2017 Jan 3;14(1):234-41. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.6b00826, PMID 28043136.

Shigeta S, Mori S, Watanabe J, Soeda S, Takahashi K, Yamase T. Synergistic anti-influenza virus A (H1N1) activities of PM-523 (polyoxometalate) and ribavirin in vitro and in vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997 Jul;41(7):1423-7. doi: 10.1128/AAC.41.7.1423, PMID 9210659, PMCID PMC163933.

Gangemi JD, Nachtigal M, Barnhart D, Krech L, Jani P. Therapeutic efficacy of liposome-encapsulated ribavirin and muramyl tripeptide in experimental infection with influenza or herpes simplex virus. J Infect Dis. 1987 Mar;155(3):510-7. doi: 10.1093/infdis/155.3.510, PMID 3805775.

Dumont EF, Oliver AJ, Ioannou C, Billiard J, Dennison J, van den Berg F. A novel inhaled dry-powder formulation of ribavirin allows for efficient lung delivery in healthy participants and those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a phase 1 study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020 Apr 21;64(5):e02267-19. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02267-19, PMID 32071044, PMCID PMC7179635.

Ibrahim MM, Maria DN, Wang X, Simpson RN, Hollingsworth TJ, Jablonski MM. Enhanced corneal penetration of a poorly permeable drug using bioadhesive multiple microemulsion technology. Pharmaceutics. 2020 Jul 26;12(8):704. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics12080704, PMID 32722550, PMCID PMC7463957.

Li X, Pan W, Ju C, Liu Z, Pan H, Zhang H. Evaluation of pharmasolve corneal permeability enhancement and its irritation on rabbit eyes. Drug Deliv. 2009 May;16(4):224-9. doi: 10.1080/10717540902850567, PMID 19514982.

Liu R, Liu Z, Zhang C, Zhang B. Gelucire44/14 as a novel absorption enhancer for drugs with different hydrophilicities: in vitro and in vivo improvement on transcorneal permeation. J Pharm Sci. 2011 Aug;100(8):3186-95. doi: 10.1002/jps.22540, PMID 21416467.

Lai CH, Yang YH, Chen PC, King YC, Liu CY. Retinal vascular complications associated with interferon-ribavirin therapy for chronic hepatitis C: A population-based study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2018 Feb;27(2):191-8. doi: 10.1002/pds.4363, PMID 29210149.

Elgouhary SM, Said Ahmed KE, Mowafy MA. Anatomical and functional retinal complications of combined sofosbuvir and ribavirin therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2019 Jan 1;50(1):39-41. doi: 10.3928/23258160-20181212-06, PMID 30640394.

Abd Elaziz MS, Nada AS, ElSayed SH, Nasr GS, Zaky AG. Ocular comorbidities with direct-acting antiviral treatment for chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) patients. Int Ophthalmol. 2020 May;40(5):1245-51. doi: 10.1007/s10792-020-01290-y, PMID 31965393.

Jeulin H, Venard V, Carapito D, Finance C, Kedzierewicz F. Effective ribavirin concentration in mice brain using cyclodextrin as a drug carrier: evaluation in a measles encephalitis model. Antiviral Res. 2009 Mar;81(3):261-6. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2008.12.006, PMID 19133295.

Sengupta S, Paul P, Mukherjee B, Gaonkar RH, Debnath MC, Chakraborty R. Peripheral nerve targeting by procaine-conjugated ribavirin-loaded dual drug nanovesicle. Nanomedicine (Lond). 2018 Dec;13(23):3009-23. doi: 10.2217/nnm-2018-0192, PMID 30507340.

Colombo G, Lorenzini L, Zironi E, Galligioni V, Sonvico F, Balducci AG. Brain distribution of ribavirin after intranasal administration. Antiviral Res. 2011 Dec;92(3):408-14. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2011.09.012, PMID 22001322.

Giuliani A, Balducci AG, Zironi E, Colombo G, Bortolotti F, Lorenzini L. In vivo nose-to-brain delivery of the hydrophilic antiviral ribavirin by microparticle agglomerates. Drug Deliv. 2018 Nov;25(1):376-87. doi: 10.1080/10717544.2018.1428242, PMID 29382237, PMCID PMC6058489.

Vasa DM, Bakri Z, Donovan MD, O’Donnell LA, Wildfong PL. Evaluation of ribavirin-poloxamer microparticles for improved intranasal absorption. Pharmaceutics. 2021 Jul 23;13(8):1126. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13081126, PMID 34452087, PMCID PMC8399989.

Loginova SJ, Shchukina VN, Borisevich SV. The modern state of prevention and treatment of chikungunya fever. Jour Antibiot Chemother. 2020;65(3-4):45-53. doi: 10.37489/0235-2990-2020-65-3-4-45-53.

Zhurkin MA, Ivanov VV, Kharitonov MA, Saluchov VV, Zhogolev KD, Zhogolev SD. The use of ribavirinum in complex therapy of virus-bacterial pneumonia. “Russian-Chinese scientific-practical conference on medical microbiology and clinical mycology (ХIХ kashkinskiye readings). Theses of reports” Problems of Medical Mycology. 2016;18(2):34-131.

Shilovskiy IP, Yumashev KV, Kozhikhova KV, Vishniakova LI, Smirnov VV, Gudima GO. A synthetic peptide mimicking the antigenic site of F protein suppresses of respiratory syncytial virus infection in vitro. Immunologiya. 2023;44(2):134-46. doi: 10.33029/0206-4952-2023-44-2-134-146.

Postnov VN, Naumysheva EB, Korolev DV, Galagudza MM. Nanoscale carriers for drug delivery//Biotechnosphere. 2013;6(30).

Chekhonin VP, Merkulov VA, Kuznetsov DA, Petrov AA, Pavlyuk AS. Prospects for the application of nanobiotechnology in medicine. Bulletin of Russian State Medical University; 2009. Available from: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/perspektivy-primeneniya-nanobiotehnologii-v-meditsine [Last accessed on 22 Jan 2025]

ReferencesYamansarov EY, Petrov RA, Petrov SA, Saltykova IV, Ondar EE, Kislyakov IV. Low-molecular glycoconjugates antiviral drug ribavirin with galactosamine derivatives-a new approach to targeted therapy of liver diseases. Russian Biotherapeutic Journal; 2017. Available from: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/nizkomolekulyarnye-glikokonyugaty-protivovirusnogo-preparata-ribavirin-s-proizvodnymi-galaktozamina-novyy-podhod-adresnoy-terapii. [Last accessed on 31 Mar 2024].

Bakhrushina EO, Ivkina AS, Tabanskaya TV. Evaluation of biopharmaceutical indicators of a new intranasal antiviral drug based on in situ system//Health and Education in the XXI century. Vol. 4; 2023. Available from: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/otsenka-biofarmatsevticheskih-pokazateley-novogo-intranazalnogo-protivovirusnogo-preparata-na-osnove-in-situ-sistemy. [Last accessed on 31 Mar 2024].

Usova SV, Targonsky SN, Zemskova LN, Zmyzgova AV, Isaeva NP, Isaeva NP. Experience with a new regimen for the treatment of chronic viral hepatitis using liposomal form of ribavirin. Vol. 4; 2012. Available from: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/opyt-primeneniya-novoy-shemy-lecheniya-hronicheskogo-virusnogo-gepatita-s-s-ispolzovaniem-liposomalnoy-formy-ribavirina. [Last accessed on 31 Mar 2024].

Glotova TI, Nikonova AA, Glotov AG. Antiviral compounds and drugs effective against bovine viral diarrhea virus//voprosyvirosologii. Vol. 5; 2017. Available from: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/protivovirusnye-soedineniya-i-preparaty-effektivnye-v-otnoshenii-virusa-virusnoy-diarei-krupnogo-rogatogo-skota. [Last accessed on 31 Mar 2024].

Mendez R. Sonication-based basic protocol for liposome synthesis. Methods Mol Biol. 2023;2625:365-70. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-2966-6_31, PMID 36653658.

Almeida B, Nag OK, Rogers KE, Delehanty JB. Recent progress in bioconjugation strategies for liposome-mediated drug delivery. Molecules. 2020 Dec 1;25(23):5672. doi: 10.3390/molecules25235672, PMID 33271886, PMCID PMC7730700.

Wang Y. Liposome as a delivery system for the treatment of biofilm-mediated infections. J Appl Microbiol. 2021 Dec;131(6):2626-39. doi: 10.1111/jam.15053, PMID 33650748.

Gorain B, Al-Dhubiab BE, Nair A, Kesharwani P, Pandey M, Choudhury H. Multivesicular liposome: a lipid-based drug delivery system for efficient drug delivery. Curr Pharm Des. 2021;27(43):4404-15. doi: 10.2174/1381612827666210830095941, PMID 34459377.

Large DE, Abdelmessih RG, Fink EA, Auguste DT. Liposome composition in drug delivery design, synthesis, characterization, and clinical application. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2021 Sep;176:113851. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2021.113851, PMID 34224787.

Lima PH, Butera AP, Cabeça LF, Ribeiro Viana RM. Liposome surface modification by phospholipid chemical reactions. Chem Phys Lipids. 2021 Jul;237:105084. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2021.105084, PMID 33891960.

Meng Y, Niu X, Li G. Liposome nanoparticles as a novel drug delivery system for therapeutic and diagnostic applications. Curr Drug Deliv. 2022;20(1):41-56. doi: 10.2174/1567201819666220324093821, PMID 35331112.

Has C, Sunthar P. A comprehensive review on recent preparation techniques of liposomes. J Liposome Res. 2020 Dec;30(4):336-65. doi: 10.1080/08982104.2019.1668010, PMID 31558079.

Gan Y, Yu Y, Xu H, Piao H. Liposomal nanomaterials: a rising star in glioma treatment. Int J Nanomedicine. 2024 Jul 5;19:6757-76. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S470478, PMID 38983132, PMCID PMC11232959.

Shah S, Dhawan V, Holm R, Nagarsenker MS, Perrie Y. Liposomes: advancements and innovation in the manufacturing process. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2020;154-155:102-22. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2020.07.002, PMID 32650041.

Guimaraes D, Cavaco Paulo A, Nogueira E. Design of liposomes as drug delivery system for therapeutic applications. Int J Pharm. 2021 May 15;601:120571. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.120571, PMID 33812967.

Inal O, Amasya G, Sezgin Bayindir Z, Yuksel N. Development and quality assessment of glutathione tripeptide loaded niosome containing carbopol emulgels as nanocosmeceutical formulations. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023 Jun 30;241:124651. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.124651, PMID 37119885.

Farmoudeh A, Akbari J, Saeedi M, Ghasemi M, Asemi N, Nokhodchi A. Methylene blue-loaded niosome: preparation, physicochemical characterization, and in vivo wound healing assessment. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2020 Oct;10(5):1428-41. doi: 10.1007/s13346-020-00715-6, PMID 32100265, PMCID PMC7447683.

Kheilnezhad B, Hadjizadeh A. Factors affecting the penetration of niosome into the skin, their laboratory measurements and dependency to the niosome composition: a review. Curr Drug Deliv. 2021;18(5):555-69. doi: 10.2174/1567201817999200820161438, PMID 32842940.

Barani M, Paknia F, Roostaee M, Kavyani B, Kalantar Neyestanaki D, Ajalli N. Niosome as an effective nanoscale solution for the treatment of microbial infections. BioMed Res Int. 2023 Aug 16;2023:9933283. doi: 10.1155/2023/9933283, PMID 37621700, PMCID PMC10447041.

Lai X, Chow SH, Le Brun AP, Muir BW, Bergen PJ, White J. Polysaccharide-targeting lipid nanoparticles to kill gram-negative bacteria. Small. 2024 Feb;20(6):e2305052. doi: 10.1002/smll.202305052, PMID 37798622.

Rezaei H, Iranbakhsh A, Sepahi AA, Mirzaie A, Larijani K. Formulation, preparation of niosome loaded zinc oxide nanoparticles and biological activities. Sci Rep. 2024 Jul 19;14(1):16692. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-67509-5, PMID 39030347, PMCID PMC11271597.

Hedayati Ch M, Abolhassani Targhi A, Shamsi F, Heidari F, Salehi Moghadam Z, Mirzaie A. Niosome-encapsulated tobramycin reduced antibiotic resistance and enhanced antibacterial activity against multidrug-resistant clinical strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2021 Jun;109(6):966-80. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.37086, PMID 32865883.

Rahmati M, Babapoor E, Dezfulian M. Amikacin-loaded niosome nanoparticles improve amikacin activity against antibiotic-resistant klebsiella pneumoniae strains. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2022 Oct 3;38(12):230. doi: 10.1007/s11274-022-03405-2, PMID 36184645, PMCID PMC9527143.

Ergin AD, Oltulu C, Turker NP, Demirbolat GM. In vitro hepatotoxicity evaluation of methotrexate-loaded niosome formulation: fabrication, characterization and cell culture studies. Turk J Med Sci. 2023 Aug;53(4):872-82. doi: 10.55730/1300-0144.5651, PMID 38031943, PMCID PMC10760534.

Salehi S, Nourbakhsh MS, Yousefpour M, Rajabzadeh G, Sahab Negah S. Chitosan-coated niosome as an efficient curcumin carrier to cross the blood-brain barrier: an animal study. J Liposome Res. 2022 Sep;32(3):284-92. doi: 10.1080/08982104.2021.2019763, PMID 34957899.

Sharma S, Kumari N, Garg D, Chauhan S. A compendium of bioavailability enhancement via niosome technology. Pharm Nanotechnol. 2023;11(4):324-38. doi: 10.2174/2211738511666230309104323, PMID 36892113.

Obeid MA, Teeravatcharoenchai T, Connell D, Niwasabutra K, Hussain M, Carter K. Examination of the effect of niosome preparation methods in encapsulating model antigens on the vesicle characteristics and their ability to induce immune responses. J Liposome Res. 2021 Jun;31(2):195-202. doi: 10.1080/08982104.2020.1768110, PMID 32396752.

Tao R, Liu L, Xiong Y, Zhang Q, Lv X, He L. Construction and evaluation of a phospholipid-based phase transition in situ gel system for brexpiprazole. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2023 Nov;13(11):2819-33. doi: 10.1007/s13346-023-01349-0, PMID 37160629.

Kalebar RV, Gajare P, Mamle DSN, Kalebar VU, Aladakatti RH. Synergistic drug compatibility of sumatriptan succinate and metoclopramide hydrochloride (in situ gel formulations) for nasal drug release optimization. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2024 Mar 7:132-8.

Singh M, Dev D. Acacia catachu gum in situ forming gels with prolonged retention time for ocular drug delivery. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2022 Sep 7:33-40. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2022.v15i9.45269.

Ambikar RB, Bhosale AV. Development and characterization of diclofenac sodium loaded eudragit RS100 polymeric microsponge incorporated into in situ gel for ophthalmic drug delivery system. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2021 Sep 1:63-9. doi: 10.22159/ijpps.2021v13i9.42405.

Reddy MS, Begum Z. Formulation and in vitro evaluation of gastro retentive in-situ floating gels of telmisartan cubosomes. Int J Curr Pharm Sci. 2022 Jan 15:44-53. doi: 10.22159/ijcpr.2022v14i1.44111.

Ourani Pourdashti S, Mirzaei E, Heidari R, Ashrafi H, Azadi A. Preparation and evaluation of niosomal chitosan-based in situ gel formulation for direct nose-to-brain methotrexate delivery. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022 Jul 31;213:1115-26. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.06.031, PMID 35691430.