Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 2, 2025, 198-203Original Article

FORMULATION AND CHARACTERIZATION OF SAMBILOTO EXTRACT ORALLY DISSOLVING FILMS: A DUAL MECHANISM FOR PROBIOTIC GROWTH AND ANTIBACTERIAL ACTION

MIKSUSANTI MIKSUSANTI*, ELSA FITRIA APRIANI, ADIK AHMADI, SHAUM SHIYAN, DINA PERMATA WIJAYA, VIO AGISTER RISANLI

Department of Pharmacy, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Universitas Sriwijaya, Indralaya, South Sumatra, Indonesia

*Corresponding author: Miksusanti Miksusanti; *Email: miksusanti@unsri.ac.id

Received: 09 Oct 2024, Revised and Accepted: 26 Nov 2024

ABSTRACT

Objective: This study aimed to develop Orally Dissolving Films (ODFs) containing Sambiloto leaf extract and evaluate their effects on the growth of the probiotic bacterium Bifidobacterium longum (B. longum) and their antibacterial activity against Escherichia coli (E. coli).

Methods: The ODFs were prepared using the solvent casting method with three concentrations: F1 (0.4%), F2 (0.6%), and F3 (0.8%). The growth of B. longum was assessed through the Total Plate Count method, while antibacterial activity was determined using the disc diffusion method.

Results: F2 was chosen as the optimal formulation, characterized by a smooth texture, a pH of 6.240±0.026, thickness of 0.102±0.008 mm, weight of 0.059±0.002 mg, disintegration time of 16.633±0.822 seconds, folding endurance of 433.00±2.000 folds, and elongation of 22.250±1.372%. F2 significantly enhanced the growth of B. longum, yielding 2.43×10¹⁰ CFU/ml and a prebiotic index of 1.056 (p<0.05). Additionally, it demonstrated antibacterial activity with an inhibition zone diameter of 7.500±0.408 mm (p<0.05).

Conclusion: This research highlights F2's potential as a nutraceutical product with both probiotic growth-enhancing and antibacterial properties.

Keywords: Antibacterial activity, Bifidobacterium longum, Nutraceutical, Orally dissolving films (ODF), Sambiloto extract

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i2.52902 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Escherichia coli (E. coli) infection is a major cause of infectious diarrheal diseases. According to the latest report from the World Health Organization (WHO), there are approximately 1.7 billion cases of diarrhea caused by E. coli infection each year, with significant mortality rates, particularly among children under the age of five in developing countries. The increasing antibiotic resistance presents an essential challenge in managing E. coli infections. Recent studies have demonstrated that E. coli strains resist to several antibiotics, including ampicillin, sulfonamides, tetracycline, streptomycin, and gentamicin [1]. The urgency to find new solutions is heightened by the substantial clinical impact and the rising incidence of antibiotic resistance, necessitating the development of more effective and sustainable alternative treatments.

Probiotics are a promising approach for managing infections caused by E. coli. Probiotics are beneficial intestinal microbiota that play a crucial role in maintaining the balance of the intestinal ecosystem and overall health. Specifically, probiotics such as Bifidobacterium longum (B. longum) are essential for intestinal health by inhibiting pathogen growth through nutrient competition and enhancing the immune system. Previous studies have shown that B. longum can increase lactic acid production, lowering intestinal pH and creating an inhospitable environment for pathogens like E. coli [2]. Additionally, research by Sharma et al. [3] revealed that B. longum strains could inhibit E. coli growth by producing bacteriocins, natural antimicrobials such as bifidocin. Bifidocin kills E. coli by breaking down its cell structure in several ways. It damages the cell membrane, leading to leaks of essential molecules like potassium, phosphate, and ATP. Additionally, bifidocin disrupts the cell’s energy balance by breaking the electric and pH gradients across the membrane, which are crucial for cell survival [4, 5]. These findings confirm the potential of probiotics in controlling E. coli infections, emphasizing their importance as a preventive and therapeutic strategy for maintaining intestinal health and combating pathogenic infections.

The existence of probiotic bacteria is greatly influenced by the availability of nutrients that can support their activity and proliferation. Prebiotics are the primary nutrients probiotic bacteria need, including dietary fiber, oligosaccharides, and polysaccharides that function as fermentation substrates, as well as vitamins and minerals needed for bacterial metabolism. Flavonoids, bioactive compounds in many plants, also play an important role in increasing probiotic bacteria population. Flavonoids can function as prebiotic agents by providing additional substrates beneficial for the growth of probiotic bacteria [6].

Sambiloto (Andrographis paniculata L.) is a traditional medicinal plant renowned for its diverse health benefits. Extensive research has highlighted that this plant contains bioactive compounds, including flavonoids like quercetin. In addition to its prebiotic activity, flavonoids in sambiloto leaves have been demonstrated to inhibit the growth of pathogenic bacteria, including E. coli. This inhibition occurs through mechanisms such as the suppression of protein synthesis, disruption of bacterial cell membranes, and the creation of unfavorable environmental conditions for pathogens [7, 8].

Administering nutraceuticals, such as probiotics, through an Orally Dissolving Film (ODFs) can enhance bioavailability and provide effective antibacterial action. Due to the fast disintegration and resorption characteristics of ODFs from oral mucosa, the active principles can easily enter systemic circulation, bypassing gastrointestinal degradation phenomena compared to conventional dosage forms, hence the strong antibacterial action. For instance, a study on ODFs containing extracts from Vaccinium oxycoccos and Plectranthusamboinicus demonstrated effective inhibition of Streptococcus mutans at minimal inhibitory concentrations of 25 µg/ml and 50 µg/ml, respectively[9]. Also, because the extract usually used from the sambiloto leaf is highly bitter, a special formulation will be required to mask the bitter taste to enhance patient compliance. The ODF dosage form, flexible pharmaceutical films that rapidly dissolve in the mouth without water, effectively mask bitterness and enhance the ease of drug administration, increasing patient adherence. Thus, ODF formulations might offer a more efficient, patient-friendly alternative for managing E. coli infections.

The primary components of ODFs are film formers and plasticizers. In this study, pullulan and maltodextrin were used as film formers. Pullulan, known for its non-toxic and water-soluble properties, forms strong and transparent films, while maltodextrin enhances the film's thickness and flexibility [10]. Propylene glycol was employed as a plasticizer to increase flexibility, reduce film brittleness, and improve elasticity [11]. Previous research has also demonstrated that including propylene glycol as a plasticizer in ODFs enhances their strength and facilitates rapid dissolution, which is crucial for efficient drug release [12].

Based on the above description, this study focused on formulating and evaluating Orally Dissolving Film (ODFs) preparations containing sambiloto leaf extract. The objective was to enhance the effectiveness of Bifidobacterium longum (B. longum) in inhibiting Escherichia coli (E. coli). This study also aimed to assess the growth stimulation of B. longum by the ODFs and evaluate the antibacterial activity of the combination of ODFs and probiotics against E. coli.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Sambiloto leaves were sourced from the Ogan Komering Ulu region in South Sumatra, Indonesia. Chemicals such as 96% ethanol, phytochemical screening reagents, distilled water, methanol pro analysis, propylene glycol, Tween 80, citric acid, and aspartame were procured from Bratachem, Indonesia. Quercetin, pullulan, and maltodextrin were obtained from Merck, Indonesia. Media for bacterial growth, including de Man, Rogosa, and Sharpe Agar (MRSA), de Man, Rogosa, and Sharpe Broth (MRSB), nutrient agar (NA), and nutrient broth (NB), were supplied by Smartlab, Indonesia. Bifidobacterium longum FNCC 0210 and Escherichia coli FNCC 0091 were obtained from the Centre for Food and Nutrition Studies, Gadjah Mada University, Indonesia.

Sambiloto leaf extraction

Sambiloto leaf extraction was performed using the maceration method. The leaves were collected from Ogan Komering Ulu, South Sumatra, Indonesia, with geographical coordinates of 103°22'–104°21' East Longitude and 04°14'–04°55' South Latitude. The sambiloto leaves were identified at the Herbarium of Universitas Andalas, with voucher specimen number 569/K-ID/ANDA/VIII/2023. The leaves were cleaned, dried, and ground using a 40-mesh sieve. The dried simplicia was then soaked in 96% ethanol solvent at a ratio of 1:10 for 5 days, stirring every 4 h. The resulting filtrate was evaporated using a rotary evaporator at 50 °C until a concentrated extract was obtained, and its yield was calculated [13, 14].

Determination of total flavonoid content

The total flavonoid content in sambiloto leaf extract was determined using ultraviolet-visible spectrophotometry [15]. Quercetin was used as the standard for constructing the calibration curve. A 1.5 ml aliquot of sambiloto leaf extract at a concentration of 1000 ppm was pipetted and mixed with 0.1 ml of 10% w/v AlCl3, 0.1 ml of 1 M sodium acetate, and distilled water up to a total volume of 5 ml. The solution was homogenized by vortexing for 10 seconds and then left in the dark for 30 min. Absorbance was measured at the maximum wavelength of 430 nm. The total flavonoid content in the extract was calculated using the following equation 1.

TFC =

(Eq. 1)

(Eq. 1)

Description:

TFC = Total Flavonoids Content

V = Total extract volume (ml)

M = Sample weight (g)

DF = Dilution factor

Preparation of orally dissolving film formula

The preparation of orally dissolving films containing sambiloto leaf extract involved creating three formulas with varying extract concentrations, namely: F1 (0.4%), F2 (0.6%), and F3 (0.8%). The concentration of extract used in these formulations references the study by Idorenyin et al. [16], which demonstrated that a 0.5% extract concentration exhibits antibacterial activity against various bacterial species. The ODF was formulated based on research from Shah et al. [17], with minor modifications. ODFs were prepared using the solvent casting method. Pullulan (346 mg) and maltodextrin (100 mg) were dissolved in distilled water at 40 °C, followed by the gradual addition of 70 mg propylene glycol until fully dissolved. The mixture was then covered with aluminum foil (Solution I). In a separate container, 25 mg of Tween 80, 20 mg of citric acid, and 60 mg of aspartame were dissolved in distilled water (Solution II). Solutions I and II were combined and stirred for 30 min, after which sambiloto leaf extract was added and mixed until homogeneous. The final solution (25 ml) was poured into Petri dishes and dried in an oven at 45 °C for 36 h. The resulting film was carefully removed and cut into 3x2 cm² pieces [18].

Evaluation of orally dissolving film preparations

The evaluation of ODFs preparations involved observing and measuring several parameters, including organoleptic properties, pH, film thickness, weight uniformity, disintegration time, folding endurance, and percent elongation. Organoleptic testing was conducted visually, assessing color, odor, taste, and surface texture. The pH of the preparation was measured using a pH meter, and film thickness was determined using a micrometer screw. Weight uniformity was assessed by weighing individual film pieces. Disintegration time was measured using a stopwatch by immersing the film in a beaker containing phosphate buffer solution at pH 6.8. Folding endurance was determined by repeatedly folding the film on the same plane until it broke, with the number of folds counted as the folding endurance value. Percent elongation was calculated by measuring the film length after being stretched until breaking, and the strength and elongation of the film were recorded. The percent elongation value was calculated using the following equation 2.

Percent elongation =  ……. (Eq. 2)

……. (Eq. 2)

Description:

L = final length

L0 = initial length

Bifidobacterium longum probiotic growth test

The growth test of B. longum probiotics was conducted using the Total Plate Count (TPC) method. The test involved various treatment groups: group I (10% probiotics), group II (10% probiotics and glucose), group III (10% probiotics and sambiloto leaf extract), group IV (10% probiotics and ODFs placebo), and group V (10% probiotics and the best ODFs). Each treatment group provided 1 ml sample to a 5 ml MRSB test tube. Subsequently, 1 ml of B. longum bacterial suspension was added, and the mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. After incubation, serial dilutions were performed using NaCl solution to achieve concentrations ranging from 10-1 to 10-8. Each dilution was then plated on Petri dishes containing MRSA media and incubated in an inverted position at 37 °C for 48 h. A colony counter was used to count the growing bacterial colonies, and the following equation 3 was applied to determine the number of product colonies:

(Eq. 3)

(Eq. 3)

Description:

N = Number of colonies (cfu/ml or cfu/g)

∑C = Number of colonies on all plates counted

n1, = Number of plates in the first dilution, and so on.

df = dilution factor in first counted

Determination of prebiotic index

The prebiotic index was determined based on research conducted by Owolabi et al. [19]. It is calculated by comparing the growth of probiotic bacteria in the presence of prebiotics with their growth in the presence of carbohydrates. In this study, glucose was used as the control carbohydrate.

Antibacterial activity test against Escherichia coli

The antibacterial activity test against E. coli FNCC 0091, obtained from the Food and Nutrition Culture Collection (FNCC), was conducted using the paper disc diffusion method. Several treatment groups were tested: the negative control group (phosphate buffer pH 6.8), the positive control group (prebiotic supplement), test group I (sambiloto leaf extract), test group II (probiotics), test group III (probiotics and sambiloto leaf extract), test group IV (probiotics and ODFs placebo), and test group V (probiotics and the best ODFs). For groups containing probiotics, metabolites were obtained by incubating the test sample for 48 h at 37 °C, centrifuging for 20 min at 15,000 rpm, and filtering through a 0.22 μm Millipore filter to collect the supernatant (metabolite) [20].

The E. coli bacterial suspension was inoculated into solidified NA media using the swab method. Paper discs with a diameter of 6 mm were soaked in the respective treatments, then aseptically placed on the media containing the test bacteria using sterile tweezers. The plates were incubated for 48 h at 37 °C. The presence of inhibition zones around the discs indicated antibacterial activity [21-23].

Data analysis

Data from the preparation evaluation, probiotic growth, and inhibition zone were analyzed using SPSS 25® software. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess normality, while one-way ANOVA was employed with a 95% confidence level to determine the significance of differences among groups. Significant differences were further analyzed using the post-hoc Duncan test to identify specific variations between test groups.

RESULTS

Sambiloto leaf extract

This study yielded a dark green, thick sambiloto leaf extract with a distinctive ethanol odor and a yield of 13.508%, meeting the standards set by the Indonesian Herbal Pharmacopoeia. The total flavonoid content was determined to be 2.594%, equivalent to 25.941 mg QE/g of extract.

Formula of orally dissolving film of sambiloto leaf extract

The evaluation results of ODFs preparations are summarized in table 1.

Growth of probiotic Bifidobacterium longum and prebiotic index

The results regarding the growth of B. longum and the prebiotic index are presented in table 2 and illustrated in fig. 1.

Table 1: Orally dissolving film’s evaluation

| Parameters | Formula | ||

| F1 | F2 | F3 | |

| Organoleptic | Smooth, elastic, green, odorless, and sweet taste. | Smooth, elastic, green, typical aroma of sambiloto leaves, and sweet taste. | Smooth, elastic, green, typical aroma of sambiloto leaves, and a slightly bitter sweet taste. |

| pH | 6.403±0.015a | 6,240±0,026b | 5.813±0.015c |

| Film thickness (mm) | 0.065±0.005a | 0,102±0,008b | 0.115±0.005c |

| Weight uniformity (mg) | 0.052±0.001a | 0,059±0,002b | 0.071±0.002c |

| Digestion time (sec) | 22.230±0.877a | 16,633±0,822b | 14.690±0.335c |

| Folding endurance | 487.333±1.527a | 433,00±2,000b | 399.333±1.527c |

| Percent elongation (%) | 25.167±1.527a | 22,250±1,372ab | 19.528±1.796b |

Descriptions: Results followed by different uppercase letters indicate significant differences based on post-hoc Duncan Test (p<0.05), Data are given as mean±SD, n=3

Fig. 1: Growth of Bifidobacterium longum at dilutions of 10-6, 10-7, 10-8

Table 2: Growth of probiotic Bifidobacterium longum and prebiotic index

| Test group | Bacterial count (CFU/ml) | Prebiotic index |

|

2.900×108d | 0.861 |

|

6.750×109c | 1 |

|

2.030×1010b | 1.048 |

|

2.193×108d | 0.848 |

|

2.430×1010a | 1.056 |

Descriptions: Results followed by different uppercase letters indicate significant differences based on post-hoc Duncan Test (p<0.05), Data are given as mean±SD, n=3, CFU means Colony Forming Unit

Table 3: Inhibition zone diameter against Escherichia coli bacteria

| Group | Treatment | Mean±SD (mm) | Category |

| Negative control | Phosphate buffer pH 6.8 | ND | No activity |

| Positive control | Prebiotic Supplement | 4.000±0.408d | Weak |

| Group I | Sambiloto leaf extract | 4.500±0.471cd | Weak |

| Group II | Probiotic | 7.500±0.408a | Moderate |

| Group III | Probiotic+sambiloto leaf extract | 5.000±0.471c | Weak |

| Group IV | Probiotic+Placebo ODFs | 6.500±0.235b | Moderate |

| Group V | Probiotic+ODFs F2 | 7.500±0.408a | Moderate |

Descriptions: Results followed by different uppercase letters indicate significant differences based on post-hoc Duncan Test (p<0.05), Data are given as mean±SD, n=3, ND means Not Determined

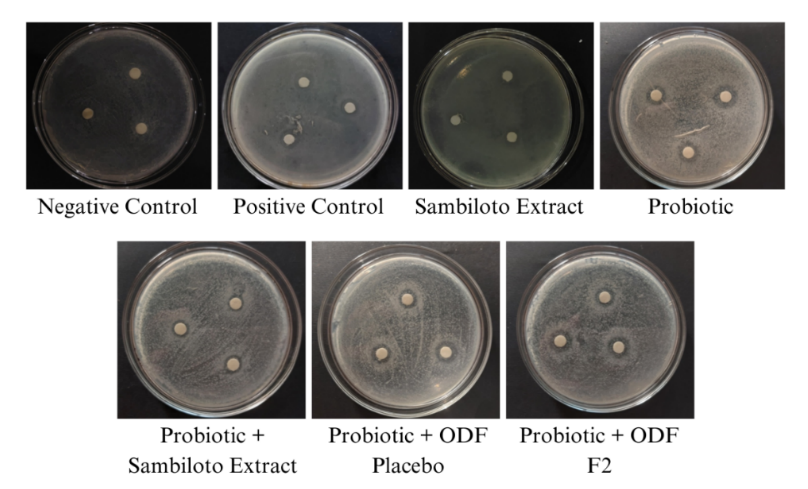

Fig. 2: Diameter of inhibition zone against Escherichia coli

Antibacterial activity against Escherichia coli

The antibacterial activity against E. coli was evaluated by measuring the diameter of the inhibition zones. The results are presented in table 3 and illustrated in fig. 2.

DISCUSSION

This study successfully developed an ODFs incorporating Sambiloto leaf extract, which contains 2.594% of the target flavonoid compound. This concentration is higher than those reported in previous studies using ethanol as a solvent, likely due to variations in the growing conditions that affect secondary metabolite production. The flavonoids in Sambiloto extract form the basis for its role as a nutraceutical ingredient with prebiotic potential. However, due to the inherent bitterness of Sambiloto, it was essential to formulate the extract in a palatable form. The ODFs, enhanced with aspartame as a sweetener, effectively masked the bitter taste of Sambiloto while delivering its active compounds. Three different ODFs formulations were developed, varying in extract concentration.

Visually, there were no significant differences among the ODFs formulations, all exhibiting a smooth, elastic texture and light green color. However, formulations F2 and F3, which contained higher concentrations of Sambiloto extract, began to exhibit a stronger herbal aroma and bitterness (table 1). The evaluation parameters (pH, thickness, weight, disintegration time, folding endurance, and elongation) demonstrated that all ODFs formulations met the required standards [24]. Notably, increasing the concentration of Sambiloto extract led to decreasedpH, disintegration time, folding endurance, and elongation percentage, while increasing the thickness and uniformity of the film weightThese changes can be attributed to the acidic properties of flavonoids, especially quercetin, present in sambiloto extract. Flavonoids like quercetin introduce acidic groups that contribute to a lower pH in the formulation, promotes disintegration by enhancing solubility in aqueous media, causing the matrix to break down more easily and faster disintegration times due to reduced intermolecular forces within the polymer matrix, as flavonoids tend to disrupt hydrogen bonding and other cohesive forces, weakening the structural integrity of the film [25, 26].

The formulation components, including maltodextrin, pullulan, and propylene glycol, significantly influenced the ODFs characteristics. Maltodextrin provided flexibility and strength to the films, while pullulan contributed to elasticity and cohesiveness, creating a soft texture in the mouth [27]. Propylene glycol, plasticizer, enhanced the film's flexibility and reduced brittleness by modifying intermolecular forces within the film matrix [28]. These components worked synergistically to produce an ODFs that was functional and palatable, with F2 emerging as the optimal formulation due to its balance of extract concentration and acceptable taste profile.

Further testing revealed that the F2 ODFs formulation significantly enhanced the probiotic bacterium B. longum's growth while exhibiting antibacterial activity against E. coli. The group treated with F2 ODFs showed the highest increase of B. longum, with a viability of 2.430×1010 CFU/ml and a prebiotic index of 1.056 (table 2 and fig. 1). This finding suggests that the F2 formulation functions effectively as a prebiotic, promoting beneficial bacterial proliferation more efficiently than the glucose control. The flavonoids present in sambiloto extract likely play a crucial role in this prebiotic effect; these compounds can be metabolized by gut microbiota into bioactive metabolites, such as phenolic acids. Studies have shown that flavonoid biotransformation by gut bacteria produces phenolic compounds that enhance B. longum growth by improving its colonization resistance and providing metabolic substrates essential for its proliferation [29, 30].

Moreover, the use of pullulan in the ODFs enhanced its nutraceutical properties by serving as a prebiotic that supports the growth and activity of beneficial bacteria like Lactobacillus rhamnosus and Lactobacillus plantarum [31]. The fermentation of pullulan by gut bacteria produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which lower intestinal pH and inhibit pathogenic bacteria while promoting probiotic proliferation [31]. Additionally, pullulan forms a protective matrix around probiotics, shielding them from harsh gastrointestinal conditions and enhancing their survival and colonization [32]. Data from table 3 shows that the combination of probiotics with F2 ODF gave an inhibition zone diameter against E. coli with a value of 7.5±0.408 mm, including in the moderate activity category. The value of this combination was equal to that of the probiotic-only group (7.5±0.408 mm), and it was higher compared to probiotics with placebo ODF (6.5±0.235 mm) or sambiloto leaf extract alone (4.5±0.471 mm). These results suggest that F2 ODF can act as a prebiotic, enhance the action of probiotics, and simultaneously exert moderate antibacterial action against E. coli, promote the growth of probiotics, and inhibit pathogenic growth.

The symbiotic effect of sambiloto extract with B. longum created a potential nutraceutical formulation to fight against E. coli infection through a dual mechanism of action, promoting gut-friendly bacteria and directly inhibiting pathogenic strains. Moreover, Sambiloto leaf extract exerts antibacterial activity by damaging cell membranes in E. coli, inhibiting metabolic enzymes, and cessation of protein synthesis. All its bioactive components, including andrographolide, flavonoids, and diterpenoids, interfere with the bacterial cell membrane and metabolism [33]. On the other hand, B. longum produces metabolic probiotic products such as lactic acid and SCFAs, which include acetic acid. This lowers intestinal pH by making an environment unsuitable for the survival of E. coli [34, 35]. Besides, B. longum synthesizes compounds such as bacteriocins and exopolysaccharides, and the bacteriocins selectively cause damage to E. coli by forming pores in the cell membrane of the latter, consequently causing cell lysis [36, 37]. The flavonoids in sambiloto also play a key role, as their biotransformation by gut bacteria produces phenolic acids that enhance the antibacterial effect. The synergistic action between sambiloto-derived phenolic acids and lactic acid from B. longum intensifies the acidification of the intestinal environment, further inhibiting E. coli growth. This combined acidification from both phenolic and lactic acids, along with bacteriocin activity, provides a robust defense against pathogens while fostering a favorable environment for probiotics [29, 30].

Although the inhibition zone diameter for this combination is moderate compared to standard antibacterial agents, this effect is still clinically relevant, especially as a probiotic supplement aimed at maintaining gut microbiota balance. Sambiloto in F2 ODF doesn't become an antibiotic per se but modulates the intestinal environment to enhance moderate pathogen inhibition while allowing colonization by beneficial bacteria. Moreover, increasing the concentration or combining it with other natural antibacterial active ingredients may enhance the antibacterial efficiency of sambiloto.

Overall, the present study has highlighted ODFs as a novel vehicle for sambiloto-derived bioactive compounds to improve gut health and fight against bacterial infection. From these, formulation F2 shows potential to enhance the growth of probiotics and inhibit harmful pathogens and thus may be a very important candidate for further development in nutraceutical therapies.

CONCLUSION

This study successfully developed a nutraceutical orally dissolving film (ODF) incorporating Sambiloto leaf extract, demonstrating significant prebiotic potential and antibacterial activity. The optimized formulation, F2, ideally masked the taste of Sambiloto and encouraged the proliferation of B. longum while inhibiting E. coli. Flavonoids in the extract and the synergistic action of pullulan and other film-forming agents are responsible for the enhanced probiotic and antibacterial action. These results suggested that Sambiloto leaf extract may act as a promising nutraceutical ingredient for gut health and antibacterial infection. Clinical treatment with F2 ODFs can be applied as supportive therapy for patients in the risk group of gastrointestinal infections or to enhance probiotic consumption. Unfortunately, all these results were from in vitro analyses; therefore, detailed in vivo studies have yet to establish these effects. Another future direction should involve testing the safety, efficacy, and bioavailability of F2 ODFs in animal models and human trials, complemented by manufacturing scale-up, stability, and shelf life, aiming to widen its applications in the nutraceutical and functional food industries. Thus, this ODF formulation may represent a new delivery system for administering bioactive compounds in nutraceutical therapies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Nil

FUNDING

The research was funded by the Directorate of Research, Technology, and Community Service, Directorate General of Higher Education, Research, and Technology of the Republic of Indonesia in accordance with the Implementation Contract for Operational Assistance for State Universities for Research Programs for the 2024 Fiscal Year Number: 090/E5/PG.02.00. PL/2024.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Miksusanti Miksusanti (1stauthor): planning, conceptualization, data collection and paper writing. Elsa Fitria Apriani, Adik Ahmadi, Shaum Shiyan, Dina Permata Wijaya and Vio Agister Risanli (2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, 6th author): data collection, review of literature and data interpretation.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

Tadesse DA, Zhao S, Tong E, Ayers S, Singh A, Bartholomew MJ. Antimicrobial drug resistance in Escherichia coli from humans and food animals, United States, 1950-2002. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18(5):741-9. doi: 10.3201/eid1805.111153, PMID 22515968.

Bhatnagar A. A comprehensive review of Kalmegh's biological activities (Andrographis paniculata). Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2023;15(2):1-7. doi: 10.22159/ijpps.2023v15i2.46705.

Sharma P, Tomar SK, Goswami P, Sangwan V, Singh R. Antibiotic resistance among commercially available probiotics. Food Res Int. 2014;57:176-95. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2014.01.025.

Martinez FA, Balciunas EM, Converti A, Cotter PD, De Souza Oliveira RP. Bacteriocin production by Bifidobacterium spp. a review. Biotechnol Adv. 2013;31(4):482-8. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.01.010, PMID 23384878.

Mandal B. Bacteriocin. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2024;16(3):1-7. doi: 10.22159/ijpps.2024v16i3.50326.

Yang L, Gao Y, Farag MA, Gong J, Su Q, Cao H. Dietary flavonoids and gut microbiota interaction: a focus on animal and human studies to maximize their health benefits. Food Front. 2023;4(4):1794-809. doi: 10.1002/fft2.309.

Chauhan ES, Sharma K, Bist R. Andrographis paniculata: a review of its phytochemistry and pharmacological activities. Res J Pharm Technol. 2019;12(2):891-900. doi: 10.5958/0974-360X.2019.00153.7.

Li Z, Ren Z, Zhao L, Chen L, Yu Y, Wang D. Unique roles in health promotion of dietary flavonoids through gut microbiota regulation: current understanding and future perspectives. Food Chem. 2023;399:133959. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.133959, PMID 36001928.

Arikatla SK, Chalasani U, Mandava J, Yelisela RK. Interfacial adaptation and penetration depth of bioceramic endodontic sealers. J Conserv Dent. 2018;21(4):373-7. doi: 10.4103/JCD.JCD_64_18, PMID 30122816.

Shah KA, Gao B, Kamal R, Razzaq A, Qi S, Zhu QN. Development and characterizations of pullulan and maltodextrin-based oral fast-dissolving films employing a box–behnken experimental design. Materials (Basel). 2022;15(10):3591. doi: 10.3390/ma15103591, PMID 35629620.

Fong RJ, Robertson A, Mallon PE, Thompson RL. The impact of plasticizer and degree of hydrolysis on free volume of poly(vinyl alcohol) films. Polymers (Basel). 2018;10(9):1036. doi: 10.3390/polym10091036, PMID 30960961.

Morales JO, McConville JT. Manufacture and characterization of mucoadhesive buccal films. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2011;77(2):187-99. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2010.11.023, PMID 21130875.

Hardestyariki D, Rasyid RS, Apriani EF. Sambiloto leaves (Andrographis paniculata (Burm.f.) Wall. Ex. Nees) nanoemulsion preparations: optimization of Tween 80 and PEG-400 concentrations as photoprotective agents. J Res Pharm. 2024;28(5):1435-48. doi: 10.29228/jrp.821.

Indarti K, Apriani EF, Wibowo AE, Simanjuntak P. Antioxidant activity of ethanolic extract and various fractions from green tea (Camellia sinensis L.) leaves. Pharmacogn J. 2019;11(4):771-6. doi: 10.5530/pj.2019.11.122.

Sudirman S, Herpandi SE, Safitri EF, Apriani EF, Taqwa FH. Total polyphenol and flavonoid contents and antioxidant activities of water lettuce (Pistia stratiotes) leave extracts. Food Res. 2022;6(4):205-10. doi: 10.26656/fr.2017.6(4).484.

Idorenyin E, Ekpenyong E, James I, Ibuot A. Antimicrobial properties of Andrographis paniculata (vinegar) leaf on selected human pathogens. World J Bio Pharm Health Sci. 2020;3(1):60-5. doi: 10.30574/wjbphs.2020.3.1.0047.

Shah KA, Gao B, Kamal R, Razzaq A, Qi S, Zhu QN. Development and characterizations of pullulan and maltodextrin-based oral fast-dissolving films employing a box–behnken experimental design. Materials (Basel). 2022;15(10):3591. doi: 10.3390/ma15103591, PMID 35629620.

Palezi SC, Fernandes SS, Martins VG. Oral disintegration films: applications and production methods. J Food Sci Technol. 2023;60(10):2539-48. doi: 10.1007/s13197-022-05589-9, PMID 37599841.

Owolabi IO, Dat-arun P, Takahashi Yupanqui C, Wichienchot S. Gut microbiota metabolism of functional carbohydrates and phenolic compounds from soaked and germinated purple rice. J Funct Foods. 2020;66:103787. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2020.103787.

Liu Q, Liu Y, Li F, Gu Z, Liu M, Shao T. Probiotic culture supernatant improves metabolic function through FGF21-adiponectin pathway in mice. J Nutr Biochem. 2020;75:108256. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2019.108256, PMID 31760308.

Fitria Apriani E, Shiyan S, Hardestyariki D, Starlista V, Laras Sari A. Optimization of hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC) and carbopol 940 in clindamycin HCl ethosomal gel as anti-acne. Res J Pharm Technol. 2024;17(2):603-11. doi: 10.52711/0974-360X.2024.00094.

Mardiyanto M, Apriani EF, Hafizhaldi Alfarizi MH. Formulation and in vitro antibacterial activity of gel containing ethanolic extract of purple sweet potato leaves (Ipomoea batatas (L.) loaded poly lactic co-glycolic acid submicroparticles against staphylococcus aureus. Res J Pharm Technol. 2022;15(8):3599-605. doi: 10.52711/0974-360X.2022.00603.

Miksusanti M, Elsa Fitria Apriani EF, Bama Bihurinin AH. Optimization of tween 80 and PEG-400 concentration in Indonesian virgin coconut oil nanoemulsion as antibacterial against Staphylococcus aureus. Sains Malays. 2023;52(4):1259-72. doi: 10.17576/jsm-2023-5204-17.

Thonte SS, Bachipale RR, Pentewar RS, Gholve SB, Bhusnure OG. Formulation and evaluation of oral fast dissolving film of levosalbutamol sulphate. World J Pharm Res. 2017;4:1298-318.

Luo Z, Murray BS, Ross AL, Povey MJ, Morgan MR, Day AJ. Effects of pH on the ability of flavonoids to act as pickering emulsion stabilizers. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2012;92:84-90. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2011.11.027, PMID 22197223.

Hoque M, Alam M, Wang S, Zaman JU, Rahman MS, Johir M. Interaction chemistry of functional groups for natural biopolymer-based hydrogel design. Materials Science and Engineering R: Reports. 2023;156. doi: 10.1016/j.mser.2023.100758.

Cupone IE, Sansone A, Marra F, Giori AM, Jannini EA. Orodispersible film (ODF) platform based on maltodextrin for therapeutical applications. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14(10):2011. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14102011, PMID 36297447.

Malipeddi VR, Awasthi R, Ghisleni DD, de Souza Braga M, Kikuchi IS, de Jesus Andreoli Pinto T. Preparation and characterization of metoprolol tartrate containing matrix type transdermal drug delivery system. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2017;7(1):66-76. doi: 10.1007/s13346-016-0334-7, PMID 27677866.

Cardona F, Andres Lacueva C, Tulipani S, Tinahones FJ, Queipo Ortuno MI. Benefits of polyphenols on gut microbiota and implications in human health. J Nutr Biochem. 2013;24(8):1415-22. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2013.05.001, PMID 23849454.

Kemperman RA, Bolca S, Roger LC, Vaughan EE. Novel approaches for analysing gut microbes and dietary polyphenols: challenges and opportunities. Microbiology (Reading). 2010;156(11):3224-31. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.042127-0, PMID 20724384.

Hong L, Kim WS, Lee SM, Kang SK, Choi YJ, Cho CS. Pullulan nanoparticles as prebiotics enhance the antibacterial properties of Lactobacillus plantarum through the induction of mild stress in probiotics. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:142. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00142, PMID 30787918.

Savitskaya I, Zhantlessova S, Kistaubayeva A, Ignatova L, Shokatayeva D, Sinyavskiy Y. Prebiotic cellulose-pullulan matrix as a “vehicle” for probiotic biofilm delivery to the host large intestine. Polymers (Basel). 2023;16(1):30. doi: 10.3390/polym16010030, PMID 38201695.

Hossain S, Urbi Z, Karuniawati H, Mohiuddin RB, Moh Qrimida AM, Allzrag AM. Andrographis paniculata (Burm. f.) wall. Ex nees: an updated review of phytochemistry, antimicrobial pharmacology, and clinical safety and efficacy. Life (Basel). 2021;11(4):348. doi: 10.3390/life11040348, PMID 33923529.

Facchin S, Bertin L, Bonazzi E, Lorenzon G, De Barba C, Barberio B. Short-chain fatty acids and human health: from metabolic pathways to current therapeutic implications. Life (Basel). 2024;14(5):559. doi: 10.3390/life14050559, PMID 38792581.

Zhang D, Jian YP, Zhang YN, Li Y, Gu LT, Sun HH. Short-chain fatty acids in diseases. Cell Commun Signal. 2023;21(1):212. doi: 10.1186/s12964-023-01219-9, PMID 37596634.

Anjana TSK. Bacteriocin-producing probiotic lactic acid bacteria in controlling dysbiosis of the gut microbiota. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:1-11. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.85114033.

Yu D, Pei Z, Chen Y, Wang H, Xiao Y, Zhang H. Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis as widespread bacteriocin gene clusters carrier stands out among the Bifidobacterium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2023;89(9):e0097923. doi: 10.1128/aem.00979-23, PMID 37681950.