Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 2, 2025, 90-103Original Article

MOLECULAR DOCKING AND PHARMACOKINETIC EVALUATION OF NANOHERBAL SENDUDUK BULU (MICONIA CRENATA (VAHL.) MICHELANG.) COMPOUNDS AS AKT1 INHIBITORS

DINA KHAIRANI, SYAFRUDDIN ILYAS*, DINI PRASTYO WATI

Study Program of Biology, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Universitas Sumatera Utara, Jl. Bioteknologi No. 1 Medan-20155, Indonesia

*Corresponding author: Syafruddin Ilyas; *Email: syafruddin6@usu.ac.id

Received: 14 Oct 2024, Revised and Accepted: 10 Dec 2024

ABSTRACT

Objective: This study seeks to investigate the potential of 36 nanoherbal compounds extracted from senduduk bulu (Miconia crenata (Vahl) Michelang.) as inhibitors of v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog 1 (AKT1) using molecular docking techniques, pharmacokinetic analysis, safety evaluation, and bioactivity assessment.

Methods: Senduduk bulu leaves were nanoparticle-processed and analyzed via Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS). Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) profiles and biological activities were predicted, and molecular docking assessed compound interactions with AKT1 using borussertib as a reference.

Results: Findings indicate that 20 out of 36 compounds meet the criteria as drug candidates, demonstrating favorable interactions with the AKT1 protein, although their affinity did not surpass that of the positive control, borussertib. Several compounds exhibited high oral bioavailability, showed no interaction with the liver enzyme Cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6), and did not inhibit the Organic cation transporter 2 (OCT2) protein in the kidneys. In terms of toxicity, these compounds displayed a range of effects, from non-hazardous to hazardous, with some potentially posing risks of hepatotoxicity, carcinogenicity, and mutagenicity.

Conclusion: This research highlights the potential of nanoherbal senduduk bulu in cancer therapy development; however, further validation through in vitro and in vivo studies is necessary to comprehensively ensure their efficacy and safety.

Keywords: AKT1 inhibition, Breast cancer, Insilico analysis, Miconia crenata, Molecular docking, Nanoherbal

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i2.52932 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is one of the most prevalent types of cancer worldwide and serves as a leading cause of death among women, with an estimated 2.3 million new cases reported in 2020, resulting in approximately 685,000 fatalities [1]. This disease is characterised by the abnormal growth of cells within breast tissue, which can metastasise to other parts of the body if not addressed promptly. Risk factors for breast cancer include genetic predispositions, environmental influences, and lifestyle choices, such as diet and physical activity [2, 3]. Current treatment options for breast cancer comprise surgery, chemotherapy, and targeted therapies, including Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 (HER2) monoclonal antibodies, antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), and inhibitors of poly(adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerase (PARPi) that target mutations in the Breast Cancer Susceptibility Gene (BRCA) [4]. Consequently, with limited treatment alternatives available, there is an urgent need to identify more effective and safer therapies to tackle the challenges of resistance to existing treatments.

One of the key targets in cancer therapy development is the AKT1 protein (serine/threonine kinase 1), which is part of the Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase (PI3K)/AKT/mTOR signalling pathway. This pathway plays a crucial role in regulating various cellular processes, including growth, proliferation, metabolism, and cell survival [5, 6]. Abnormal activation of this pathway is often associated with cancer progression. In the context of breast cancer, AKT1 is frequently overexpressed or mutated, leading to resistance against conventional therapies such as chemotherapy and hormone treatments [7]. These mutations are commonly observed in cancers with alterations in the estrogen receptor (ER), contributing to the development and progression of more aggressive disease [8]. Consequently, AKT1 presents an attractive target for therapeutic intervention, where inhibiting its activity is expected to slow down or halt tumour growth. Several synthetic inhibitors have been developed, showing promising results; however, the long-term impacts and side effects of these drugs remain a significant concern [9]. In the realm of drug research, molecular docking techniques have emerged as essential computational methods for predicting interactions between molecules, such as drug compounds and target proteins. This technique is particularly valuable for identifying new drug candidates capable of inhibiting specific protein activities, like that of AKT1 [10, 11]. The use of docking software allows for the evaluation of binding affinities between tested compounds and the target protein, providing vital information for developing more effective cancer therapies [12]. Additionally, molecular docking enables the simulation of molecular interactions, thereby predicting the potential of compounds as inhibitors and assessing their mechanisms of action [13].

An innovative approach in cancer treatment involves the utilisation of natural compounds derived from biological resources, such as medicinal plants. Senduduk bulu (Miconia crenata) is known to possess various biological activities, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and potential anti-cancer effects [14, 15]. Preliminary studies indicate that the leaf extracts of senduduk bulu contain bioactive compounds that may serve as anti-cancer agents. Through the technique of nanoformulation, these compounds can be obtained in the form of nanoherbal preparations, which are expected to enhance bioavailability, stability, and efficacy, thereby improving the penetration of active ingredients into cancer cells and minimising unwanted side effects [16].

This study aims to explore the potential of nano herbal compounds derived from the leaves of senduduk bulu as AKT1 inhibitors through in silico analysis. By employing a molecular docking approach, it is anticipated that compounds with a high affinity for AKT1 will be identified. Additionally, ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) analysis will be conducted to evaluate the safety profile and bioavailability of these compounds. The findings from this research are expected to make a significant contribution to the development of more effective cancer therapies while also highlighting the importance of exploring natural resources in the discovery of new drugs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant collection and preparation of nanoherbal senduduk bulu (Miconia crenata (Vahl) Michelang.)

The leaves of senduduk bulu were collected from Padangsidimpuan, North Sumatra, Indonesia. Subsequently, the plant was identified at the Herbarium of Andalas University, under identification number 28/K-ID/ANDA/I/2024. The collected leaves were then dried and ground using a blender. Following this, the leaves underwent nanoparticle processing using a Planetary Ball Mill (PBM) (Tokyo, Japan) at Nanotech Indonesia.

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analisys

Bioactive compounds from the nanoherbal senduduk bulu in 96% ethanol were identified using GC-MS (Shimadzu QP 2010S), employing Wiley/NIST library software for data analysis. The analysis was conducted with an Rtx-5 ms column measuring 30 metres (Restek Corp). The injector and detector temperatures were maintained at 250 °C, while the operating temperature ranged from 50 to 300 °C. The column temperature was programmed to increase from 50 °C to 120 °C at a rate of 4 °C per minute, held for one minute, and then raised from 120 °C to 300 °C at a rate of 6 °C per minute, held for five minutes, resulting in a total retention time of 80 min. Helium was used as the carrier gas, with a mass-to-charge ratio range of 50-500 AMU. Electron ionization was performed at 70 eV [17].

Bioactive compounds from nano herbal sen duduk bulu

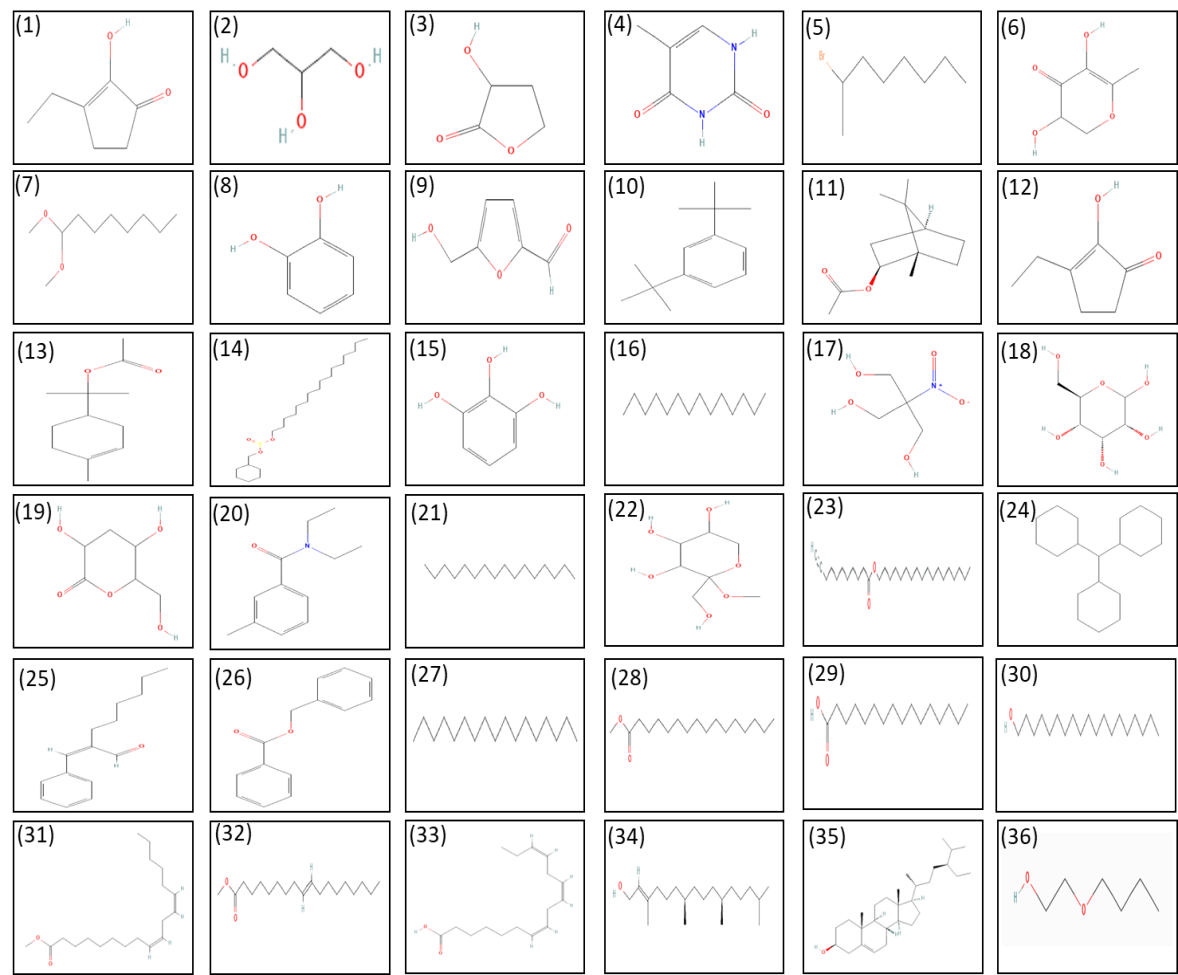

This study identified 36 bioactive compounds from the nanoherbal senduduk bulu, which include: 2-Cyclopenten-1-one, 2-hydroxy-(PubChem CID: 82674), Glycerin (PubChem CID: 753), 2-Hydroxy-gamma-butyrolactone (PubChem CID: 545831), Thymine (PubChem CID: 1135), 2-Bromo-octane (PubChem CID: 79046), 4H-Pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl-(PubChem CID: 119838), Octanal dimethyl acetal (PubChem CID: 61431), Catechol (PubChem CID: 289), 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural (PubChem CID: 237332), 1,3-Bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)benzene (PubChem CID: 136810), Isobornyl acetate (PubChem CID: 6950273), 3-Ethyl-2-hydroxy-2-cyclopenten-1-one (PubChem CID: 62752), α-Terpinyl acetate (PubChem CID: 111037), Sulfurous acid, cyclohexylmethyl hexadecyl ester (PubChem CID: 6421705), 1,2,3-Benzenetriol (PubChem CID: 1057), Tetradecane (PubChem CID: 12389), 2-(Hydroxymethyl)-2-nitro-1,3-propanediol (PubChem CID: 31337), D-Allose (PubChem CID: 439507), 3-Deoxy-D-mannoic lactone (PubChem CID: 541561), Diethyltoluamide (PubChem CID: 4284), Hexadecane (PubChem CID: 11006), α-Methyl-L-sorboside (PubChem CID: 219886), Octadecyl ester of undec-10-ynoic acid (PubChem CID: 91692469), Tricyclohexyl methane (PubChem CID: 137109), 2-(Phenylmethylene)-octanal (PubChem CID: 1715135), Benzyl benzoate (PubChem CID: 2345), Heptadecane (PubChem CID: 12398), Methyl hexadecanoate (PubChem CID: 8181), n-Hexadecanoic acid (PubChem CID: 985), n-Nonadecanol-1 (PubChem CID: 80281), Methyl 9,12-octadecadienoate (Z,Z)-(PubChem CID: 5284421), Methyl 9-octadecenoate (PubChem CID: 5280590), (Z,Z,Z)-7,10,13-hexadecatrienoic acid (PubChem CID: 5312428), Phytol (PubChem CID: 5280435), γ-Sitosterol (PubChem CID: 457801), and 2-Butoxyethanol (PubChem CID: 8133). The 2D structures of the bioactive chemical molecules from nanoherbal senduduk bulu are depicted in fig. 1.

Fig. 1: 2D structures of the compounds from nanoherbal senduduk bulu (1) 2-Cyclopenten-1-one, 2-hydroxy-; (2) Glycerin; (3) 2-Hydroxy-gamma-butyrolactone; (4) Thymine; (5) Octane, 2-bromo-; (6) 4H-Pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl-; (7) Octanal dimethyl acetal; (8) Catechol; (9) 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural; (10) Benzene, 1,3-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-; (11) Isobornyl acetate; (12) 2-Cyclopenten-1-one, 3-ethyl-2-hydroxy-; (13) α-Terpinyl acetate; (14) Sulfurous acid, cyclohexylmethyl hexadecyl ester; (15) 1,2,3-Benzenetriol; (16) Tetradecane; (17) 1,3-Propanediol, 2-(hydroxymethyl)-2-nitro-; (18) D-Allose; (19) 3-Deoxy-d-mannoic lactone; (20) Diethyltoluamide; (21) Hexadecane; (21) α-Methyl-l-sorboside; (22) Undec-10-ynoic acid, octadecyl ester; (23) Methane, tricyclohexyl-; (24) Octanal, 2-(phenylmethylene)-; (25) Benzyl Benzoate; (26) Heptadecane; (27) Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester; (29) n-Hexadecanoic acid; (30) n-Nonadecanol-1; (31) 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid (Z,Z)-, methyl ester; (32) 9-Octadecenoic αSitosterol; (36) Ethanol, 2-butoxy

Prediction of the absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) profiles for different compounds

To assess the ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) profile of the compounds, their 2D structures were downloaded in. sdf format, and the SMILES structures were retrieved from the PubChem database (http://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). ADME analysis was performed using the SwissADME platform (http://www.swissadme.ch/index.php), which identifies key pharmacokinetic parameters. The compounds' ability to cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) was then predicted using the pkcSM tool (https://biosig.lab.uq.edu.au/pkcsm/prediction). Descriptors such as the number of hydrogen bond donors and acceptors, molecular weight, bioavailability, and compliance with Lipinski’s Rule of Five were considered to evaluate the compounds' potential for oral absorption and pharmacological activity. Finally, toxicity predictions were carried out using the ProTox-II server (https://tox.charite.de/protox3/), based on toxicity classifications in line with the Globally Harmonised System (GHS) for Classification and Labelling of Chemicals [18].

Assessment of the compounds biological activities using the PASS online tool

The biological activity screening of compounds derived from nanoherbal senduduk bulu was performed using the Prediction of Activity Spectra of Substances (PASS) test through the Way2drug online platform (http://way2drug.com/PassOnline/). Initially, the compound names were entered into the PubChem database (http://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) to retrieve their SMILES structures. These structures were then submitted to the Way2drug server for the prediction of biological activities. The PASS online test results provided Pa values, classified into three categories: (i) Pa>0.7 indicates a high probability of the compound being biologically active, (ii) 0.5<Pa<0.7 suggests moderate biological activity, and (iii) Pa<0.5 signifies low biological activity [19].

Molecular docking evaluation

The preparation of ligands was carried out using the BIOVIA Discovery Studio software (https://discover.3ds.com/discovery-studio-visualizer-download). Ligand structures were obtained from the PubChem database (http://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and saved in Standard Data Format (SDF) for further analysis. These ligands were also subjected to energy minimization via Open Babel, integrated with Pyrx v.0.8. Molecular docking simulations were carried out to evaluate the potential of bioactive compounds from senduduk bulu as AKT1 inhibitors. The AKT1 protein (PDB ID: 6HHF) was retrieved from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 6HHF; https://www.rcsb.org/structure/6HHF) and docked with each nanoherbal senduduk bulu compound [20]. Borussertib (PubChem CID: 122668091), a standard commercial inhibitor, served as a reference control to compare the inhibitory effects of the bioactive compounds, as summarized in table 1. Docking was performed using AutoDock Vina within Pyrx, and the results were visualized with PyMOL.

Table 1: Active site and grid position of specific docking

| Protein | PDB ID | Active site | Ref. | Grid coordinate (Å) |

| Center | ||||

| Akt1 | 6hhf | Trp80, Ile84, Glu85, Leu210, Leu264, Lys268, Val270, Tyr272, Arg273, Asp292 | X: 7.4778 Y: 6.1953 Z: 12.6163 |

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis

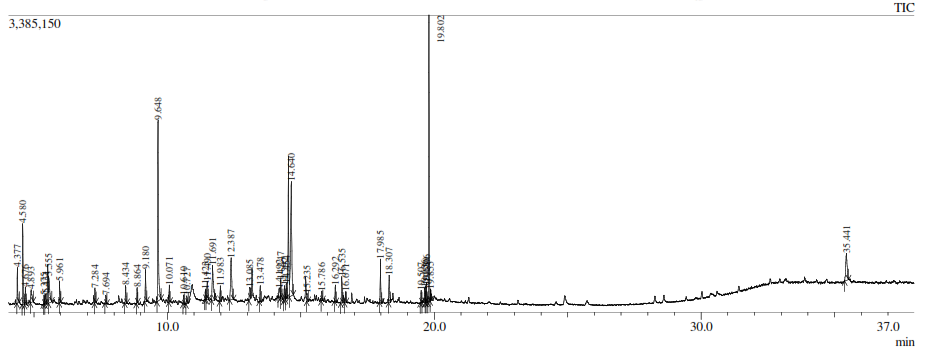

GC-MS is a vital analytical technique in the field of chemistry, combining two powerful methods to effectively identify and quantify volatile and semi-volatile compounds within complex mixtures [21]. In the context of this study, GC-MS is employed to identify and quantify bioactive compounds in herbal extracts. The results from GC-MS provide valuable insights into the chemical composition of the samples, which can then be further analysed to understand the potential bioactivity of these compounds [22, 23]. Raw data from the GC-MS analysis and individual chromatograms were evaluated using Origin software. The GC-MS analysis identified 36 bioactive compounds, one of which is a solvent in the nanoherbal senduduk bulu, including Ethanol, 2-butoxy-; 2-Cyclopenten-1-one, 2-hydroxy-; Glycerin; 2-Hydroxy-gamma-butyrolactone; Thymine; Octane, 2-bromo-; 4H-Pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl-; Octanal dimethyl acetal; Catechol; 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural; Benzene, 1,3-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-; Isobornyl acetate; 2-Cyclopenten-1-one, 3-ethyl-2-hydroxy-; α-Terpinyl acetate; sulfurous acid, cyclohexylmethyl hexadecyl ester; 1,2,3-Benzenetriol; Tetradecane; 1,3-Propanediol, 2-(hydroxymethyl)-2-nitro-; D-Allose; 3-Deoxy-d-mannoic lactone; Diethyltoluamide; Hexadecane; α-Methyl-l-sorboside; Undec-10-ynoic acid, octadecyl ester; Methane, tricyclohexyl-; Octanal, 2-(phenylmethylene)-; Benzyl benzoate; Heptadecane; Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester; n-Hexadecanoic acid; n-Nonadecanol-1; 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid (Z,Z)-, methyl ester; 9-Octadecenoic acid, methyl ester; 7,10,13-Hexadecatrienoic acid; Phytol; and γ-Sitosterol. The chromatogram shown in fig. 2 and the retention times of these compounds are presented in table 2. According to screening results from PubChem, 31 of these compounds possess 3D structures. Consequently, these 31 compounds will be further selected for docking analysis to evaluate their potential as AKT1 inhibitors.

The GC-MS analysis revealed the presence of various compounds with different retention times. Ethanol, specifically 2-butoxy, was identified as the primary solvent component, exhibiting a retention time of 4.58 min and a concentration of 4.59%. Commonly referred to as butoxyethanol or 2-butoxyethanol, this solvent is widely employed in various industrial and commercial applications. It belongs to the glycol ether group and possesses the ability to dissolve a range of substances, including oils, fats, and resins [24]. The detection of compounds such as catechol, with a retention time of 9.180 min, and hexadecanoic acid, with a retention time of 18.307 min, at significant concentrations suggests the presence of biologically active compounds, as these substances are frequently associated with antioxidant and antimicrobial properties [25, 26]. Additionally, compounds such as 2-cyclopenten-1-one, 2-hydroxy-and α-terpinyl acetate, detected at relatively short retention times of 4.893 min and 11.423 min, demonstrate good stability under the analytical conditions, making them attractive candidates for further development in pharmaceutical or cosmetic formulations. The identification of longer retention time compounds like 1,2,3-benzenetriol and γ-sitosterol, with retention times of 11.691 min and 35.441 min respectively, indicates the presence of high molecular weight substances that may contribute to the structure or function of more complex materials within the sample. Overall, the chemical composition of nanoherbal senduduk bulu highlights its broad potential applications in the chemical industry, pharmaceuticals, and as a raw material for the development of new products.

Prediction of drug-likeness

Predicting the drug-likeness of compounds is a crucial initial step in drug development, as it provides essential insights into the potential of a compound to serve as an effective therapeutic agent [27]. Evaluating the physicochemical properties of these compounds against established criteria, such as Lipinski's Rule of Five, allows for the assessment of favourable pharmacokinetic profiles. Based on the physicochemical analysis of compounds from the nanoherbal senduduk bulu and their adherence to Lipinski's criteria, as detailed in table 3, it was found that 20 out of a total of 36 selected compounds meet the criteria for drug-like properties. Among these, one compound, 2-butoxyethanol (ethanol), along with 15 other compounds, did not fully satisfy the drug-likeness criteria. Compounds such as sulfurous acid, cyclohexylmethyl hexadecyl ester, tetradecane, hexadecane, under-10-yonic acid, octadecyl ester, tricyclohexylmethane, heptadecane, hexadecanoic acid methyl ester, n-hexadecanoic acid, n-nonadecanol-1, 9,12-octadecadienoic acid (Z,Z)-methyl ester, 9-octadecenoic acid methyl ester, and phytol failed to meet the criteria due to their high MlogP values exceeding ≤ 4.15. Additionally, compounds such as D-allose and α-methyl-l-sorboside did not comply because they surpassed the minimum threshold of 6. These deviations highlight the need for further optimisation of these compounds to enhance their pharmacokinetic properties. Elevated MlogP values indicate excessive lipophilicity, which can lead to poor solubility in aqueous environments, resulting in reduced absorption in the gastrointestinal tract when administered orally [28]. Modifications that can be implemented to address these discrepancies involve optimising the balance between hydrophobic and hydrophilic properties, which may enhance solubility, bioavailability, and the drug-likeness of these compounds, thereby making them more suitable candidates for therapeutic use [29].

Twenty compounds exhibited high potential as drug candidates with clinical viability. These compounds not only demonstrated MlogP values within acceptable limits but also maintained an optimal number of hydrogen bonds and molecular weights conducive to good bioavailability. Adherence to Lipinski's Rule indicates that these compounds possess favourable pharmacokinetic profiles, encompassing absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion, thereby increasing the likelihood of their success in further development as therapeutic agents, particularly in clinical applications [30, 31].

Table 2: Identified compounds of nanoherbal senduduk bulu by GC-MS

| No | Compounds name | Mol. formula | Mass (g/mol) | R. Time (min) | Concentration (%) | Smiles | PubChem CID |

| 1 | Ethanol, 2-butoxy- | C6H14O2 | 118 | 4.58 | 4.59 | CCCCOCCO | 8133 |

| 2 | 2-Cyclopenten-1-one, 2-hydroxy- | C5H6O2 | 98 | 4.893 | 1.47 | C1CC(=O)C(=C1)O | 82674 |

| 3 | Glycerin | C3H8O3 | 92 | 5.555 | 2.8 | C(C(CO)O)O | 753 |

| 4 | 2-Hydroxy-gamma-butyrolactone | C4H6O3 | 102 | 5.961 | 1.19 | C1COC(=O)C1O | 545831 |

| 5 | Thymine | C5H6N2O2 | 126 | 7.284 | 0.85 | CC1=CNC(=O)NC1=O | 1135 |

| 6 | Octane, 2-bromo- | C8H17Br | 192 | 7.694 | 0.52 | CCCCCCC(C)Br | 79046 |

| 7 | 4H-Pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl- | C6H8O4 | 144 | 8.434 | 1.12 | CC1=C(C(=O)C(CO1)O)O | 119838 |

| 8 | Octanal dimethyl acetal | C10H22O2 | 174 | 8.864 | 0.76 | CCCCCCCC(OC)OC | 61431 |

| 9 | Catechol | C6H6O2 | 110 | 9,180 | 1.96 | C 1=CC=C(C(=C1)O)O | 289 |

| 10 | 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural | C6H6O3 | 126 | 9,648 | 13.13 | C1=C(OC(=C1)C=O)CO | 237332 |

| 11 | Benzene, 1,3-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)- | C14H22 | 190 | 10,071 | 0.87 | CC(C)(C)C1=CC(=CC=C1)C(C)(C)C | 136810 |

| 12 | Isobornyl acetate | C12H20O2 | 196 | 10,610 | 0.5 | CC(=O) OC1CC2CCC1(C2(C)C)C | 6950273 |

| 13 | 2-Cyclopenten-1-one, 3-ethyl-2-hydroxy- | C7H10O2 | 126 | 10,727 | 0.63 | CCC1=C(C(=O) CC1) O | 62752 |

| 14 | α-Terpinyl acetate | C12H20O2 | 196 | 11,423 | 0.59 | CC1=CCC(CC1)C(C)(C)OC(=O)C | 111037 |

| 15 | Sulfurous acid, cyclohexylmethyl hexadecyl ester | C23H46O3S | 402 | 11,490 | 1.3 | CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCOS(=O)OCC1CCCCC1 | 6421705 |

| 16 | 1,2,3-Benzenetriol | C6H6O3 | 126 | 11,691 | 4.04 | C1=CC(=C(C(=C1)O)O)O | 1057 |

| 17 | Tetradecane | C14H30 | 198 | 11,983 | 0.88 | CCCCCCCCCCCCCC | 12389 |

| 18 | 1,3-Propanediol, 2-(hydroxymethyl)-2-nitro- | C4H9NO5 | 151 | 12,387 | 4.99 | C(C(CO)(CO)[N+](=O)[O-])O | 31337 |

| 19 | D-Allose | C6H12O6 | 180 | 13,085 | 1.35 | C(C1C(C(C(C(O1)O)O)O)O)O | 439507 |

| 20 | 3-Deoxy-d-mannoic lactone | C6H10O5 | 162 | 14,192 | 1.02 | C1C(C(OC(=O)C1O)CO)O | 541561 |

| 21 | Diethyltoluamide | C12H17NO | 191 | 14,392 | 0.82 | CCN(CC)C(=O)C1=CC=CC(=C1)C | 4284 |

| 22 | Hexadecane | C16H34 | 226 | 14,454 | 0.84 | CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCC | 11006 |

| 23 | α-Methyl-l-sorboside | C7H14O6 | 194 | 14,640 | 13.29 | COC1(C(C(C(CO1)O)O)O)CO | 219886 |

| 24 | Undec-10-ynoic acid, octadecyl ester | C29H54O2 | 434 | 15,235 | 0.54 | CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCOC(=O)CCCCCCCCC#C | 91692469 |

| 25 | Methane, tricyclohexyl- | C19H34 | 262 | 15,786 | 0.55 | C1CCC(CC1)C(C2CCCCC2)C3CCCCC3 | 137109 |

| 26 | Octanal, 2-(phenylmethylene)- | C15H20O | 216 | 16,292 | 0.98 | CCCCCCC(=CC1=CC=CC=C1)C=O | 1715135 |

| 27 | Benzyl Benzoate | C14H12O2 | 212 | 16,535 | 1.75 | C1=CC=C(C=C1)COC(=O)C2=CC=CC=C2 | 2345 |

| 28 | Heptadecane | C17H36 | 240 | 16.671 | 0.64 | CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCC | 12398 |

| 29 | Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester | C17H34O2 | 270 | 17.985 | 2.37 | CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCC(=O)OC | 8181 |

| 30 | n-Hexadecanoic acid | C16H32O2 | 256 | 18.307 | 1.96 | CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCC(=O)O | 985 |

| 31 | n-Nonadecanol-1 | C19H40O | 284 | 19.507 | 0.73 | CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCO | 80281 |

| 32 | 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid (Z,Z)-, methyl ester | C19H34O2 | 294 | 19.636 | 1.12 | CCCCCC=CCC=CCCCCCCCC(=O)OC | 5284421 |

| 33 | 9-Octadecenoic acid, methyl ester | C19H36O2 | 296 | 19.680 | 1.02 | CCCCCCCCC=CCCCCCCCC(=O)OC | 5280590 |

| 34 | 7,10,13-Hexadecatrienoic acid | C16H26O2 | 250 | 19.706 | 1.11 | CCC=CCC=CCC=CCCCCCC(=O)O | 5312428 |

| 35 | Phytol | C20H40O | 296 | 19.802 | 16.7 | CC(C)CCCC(C)CCCC(C)CCCC(=CCO)C | 5280435 |

| 36 | γ-Sitosterol | C29H50O | 414 | 35.441 | 3.53 | CCC(CCC(C)C1CCC2C1(CCC3C2CC=C4C3(CCC(C4)O)C)C)C(C)C | 457801 |

Fig. 2: GC-MS chromatogram of nanoherbal senduduk bulu

Table 3: The physicochemical characteristic of compounds nanoherbal senduduk bulu were assessed based on lipinski’s rule of five

| No | Compound name | Lipinski | Violasi | |||

| MW | MlogP ≤ 4.15 | NorO ≤ 10 | NHorOH ≤ 5 | |||

| Positive control | ||||||

| Borussertib | 596 | 3.66 | 3 | 5 | Yes (1) | |

| Bioactive components of the nanoherbal Clidemia crenata | ||||||

| Ethanol, 2-butoxy- | 118 | 0.61 | 1 | 2 | Yes (0) | |

| 2-Cyclopenten-1-one, 2-hydroxy- | 98 | -0.42 | 1 | 2 | Yes (0) | |

| Glycerin | 92 | -1.51 | 3 | 3 | Yes (0) | |

| 2-Hydroxy-gamma-butyrolactone | 102 | -0.79 | 1 | 3 | Yes (0) | |

| Thymine | 126 | -0.39 | 2 | 2 | Yes (0) | |

| Octane, 2-bromo- | 192 | 3.76 | 0 | 0 | Yes (0) | |

| 4H-Pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl- | 144 | -1.77 | 2 | 4 | Yes (0) | |

| Octanal dimethyl acetal | 174 | 2.32 | 0 | 2 | Yes (0) | |

| Catechol | 110 | 0.79 | 2 | 2 | Yes (0) | |

| 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural | 126 | -1.06 | 1 | 3 | Yes (0) | |

| Benzene, 1,3-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)- | 190 | -1.06 | 1 | 3 | Yes (0) | |

| Isobornyl acetate | 196 | 2.76 | 0 | 2 | Yes (0) | |

| 2-Cyclopenten-1-one, 3-ethyl-2-hydroxy- | 126 | 0.31 | 1 | 2 | Yes (0) | |

| α-Terpinyl acetate | 196 | 2.65 | 0 | 2 | Yes (0) | |

| Sulfurous acid, cyclohexylmethyl hexadecyl ester | 402 | 4.92 | 0 | 3 | Yes (1) | |

| 1,2,3-Benzenetriol | 126 | 0.18 | 3 | 3 | Yes (0) | |

| Tetradecane | 198 | 5.93 | 0 | 0 | Yes (1) | |

| 1,3-Propanediol, 2-(hydroxymethyl)-2-nitro- | 151 | -2.41 | 3 | 5 | Yes (0) | |

| D-Allose | 180 | -2.75 | 5 | 6 | Yes (0) | |

| 3-Deoxy-d-mannoic lactone | 162 | -1.68 | 3 | 5 | Yes (0) | |

| Diethyltoluamide | 191 | 2.72 | 0 | 1 | Yes (0) | |

| Hexadecane | 226 | 6.44 | 0 | 0 | Yes (1) | |

| α-Methyl-l-sorboside | 194 | -2.4 | 4 | 6 | Yes (0) | |

| Undec-10-ynoic acid, octadecyl ester | 434 | 6.9 | 0 | 2 | Yes (1) | |

| Methane, tricyclohexyl- | 262 | 6.76 | 0 | 0 | Yes (1) | |

| Octanal, 2-(phenyl methylene)- | 216 | 3.68 | 0 | 1 | Yes (0) | |

| Benzyl Benzoate | 212 | 3.41 | 0 | 2 | Yes (0) | |

| Heptadecane | 240 | 6.68 | 0 | 0 | Yes (1) | |

| Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester | 270 | 4.44 | 0 | 2 | Yes (1) | |

| n-Hexadecanoic acid | 256 | 4.19 | 1 | 2 | Yes (1) | |

| n-Nonadecanol-1 | 284 | 5.17 | 1 | 1 | Yes (1) | |

| 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid (Z,Z)-, methyl ester | 294 | 4.7 | 0 | 2 | Yes (1) | |

| 9-Octadecenoic acid, methyl ester | 296 | 4.8 | 0 | 2 | Yes (1) | |

| 7,10,13-Hexadecatrienoic acid | 250 | 3.9 | 1 | 2 | Yes (0) | |

| Phytol | 296 | 5.25 | 1 | 1 | Yes (1) | |

| γ-Sitosterol | 414 | 6.73 | 1 | 1 | Yes (1) | |

Predicted pharmacokinetic properties of the nano herbal senduduk bulu compounds

Absorption of the compounds

The analysis of the absorption of compounds from nanoherbal senduduk bulu, as presented in table 4 indicates that the majority of these compounds can be efficiently absorbed by the human intestine, with 17 out of a total of 20 compounds exhibiting absorption rates exceeding 80%. For instance, the compound 2-cyclopenten-1-one, 2-hydroxy-demonstrated the highest absorption rate at 95.862%. Conversely, some compounds, such as 3-deoxy-D-mannoic lactone and 1,3-propanediol, 2-(hydroxymethyl)-2-nitro-, showed lower absorption rates of 52.503% and 65.925%, respectively. Compounds with intestinal absorption rates above 80% indicate high oral bioavailability, suggesting a favourable pharmacokinetic profile that includes elevated plasma concentrations and prolonged action duration following oral administration [32, 33]. Additionally, the Caco-2 permeability assay, used to estimate the rate of oral drug absorption, corroborates these findings, as the majority of compounds exhibited high permeability, with Papp values exceeding 1.0 x 10-6 cm/s in 16 out of the 20 compounds assessed. Compounds with high permeability values are considered capable of efficiently crossing the intestinal membrane, which correlates with good oral bioavailability. Those with Papp values above 1.0x10-6 cm/s frequently demonstrate sufficiently high absorption rates in in vivo models, supporting their use in predicting drug absorption in humans [34, 35].

Distribution of the compounds

To understand the distribution of compounds from nanoherbal senduduk bulu, an analysis was conducted on their oral bioavailability in humans, specifically, the ability of compounds to enter the bloodstream after oral consumption and their capacity to cross the Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB). The results presented in table 4 indicate that the majority of compounds exhibit negative BBB permeability values, leading to the conclusion that these compounds are unlikely to directly affect the central nervous system. Compounds with low or negative BBB permeability may require additional strategies, such as chemical modifications, to enhance their potential to penetrate the BBB. However, if the therapeutic target is not located in the brain, low BBB permeability is considered advantageous, as it may reduce the risk of undesirable side effects on the central nervous system [35, 36].

Metabolism of the compounds

Cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6) enzymes play a crucial role in the metabolism of various medications, predominantly located in the liver. This enzyme is responsible for the metabolism of approximately 20-25% of all clinically used drugs [37]. Interactions with this enzyme can lead to significant alterations in the pharmacokinetics of medications, potentially resulting in undesirable drug interactions. The results presented in table 4 indicate that these compounds are unlikely to interfere with the metabolism of other drugs via this enzymatic pathway. This suggests that compounds that do not act as substrates or inhibitors of CYP2D6 generally exhibit simpler drug interaction profiles, which may help mitigate the risk of side effects associated with pharmacokinetic interactions [38].

Excretion of the compounds

Organic cation transporter 2 (OCT2) is a membrane protein that plays a critical role in the transport of organic cations in the kidneys, particularly in the absorption and excretion of compounds in the proximal tubules. It is capable of transporting a wide range of organic cations, including drugs, metabolites, and endogenous compounds [39, 40]. Based on the results shown in table 4, no compounds were identified as substrates for the OCT2 transporter involved in the renal transport of organic cations. This suggests that these compounds are less likely to interact with other drugs via competitive transport mechanisms in the kidneys, thereby reducing the potential for harmful pharmacokinetic interactions [41].

Water solubility of the compounds

Water solubility is a critical physicochemical property in pharmacokinetics, as it affects the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion of drugs in the body. As indicated in table 4 the compounds exhibit considerable variation in their solubility. Nine compounds fall into the highly soluble category, including glycerin, 2-hydroxy-gamma-butyrolactone, thymine, 4H-pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl-, catechol, 5-hydroxymethylfurfural, 2-cyclopenten-1-one, 3-ethyl-2-hydroxy-, 1,3-propanediol, 2-(hydroxymethyl)-2-nitro-, and 3-deoxy-D-mannoic lactone. High solubility typically indicates that these compounds are easily absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract following oral administration [42]. Two compounds, 2-cyclopenten-1-one, 2-hydroxy-and 1,2,3-benzenetriol, are classified as moderately soluble. Another two compounds, α-terpinyl acetate and diethyltoluamide, are categorised as sparingly soluble, and seven compounds are classified as poorly soluble. These include octane, 2-bromo-, octanal dimethyl acetal, benzene, 1,3-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-, isobornyl acetate, octanal, 2-(phenylmethylene)-, benzyl benzoate, and 7,10,13-Hexadecatrienoic acid. Low solubility can present a significant barrier to absorption within the body, as these compounds may not dissolve quickly enough in the gastrointestinal tract, potentially leading to low bioavailability. Compounds with poor water solubility often require specialised formulations, such as complex formation or the use of solubilising excipients, to improve their solubility [43].

Table 4: Pharmakokinetics properties of compounds from nano herbal senduduk bulu

| No | Compounds name | Human intestinal absorption | Caco-2 permeability | BBB permanent | CYP2D6 substrate | CYP2D6 inhibitor | OCT2 substrate | Log S (ESOL) |

| 1 | 2-Cyclopenten-1-one, 2-hydroxy- | 95.862 | 1.577 | -0.27 | No | No | No | Moderately soluble |

| 2 | Glycerin | 74.246 | 1.073 | -0.362 | No | No | No | Highly soluble |

| 3 | 2-Hydroxy-gamma-butyrolactone | 95.746 | 1.109 | -0.28 | No | No | No | Highly soluble |

| 4 | Thymine | 86.806 | 0.617 | -0.441 | No | No | No | Highly soluble |

| 5 | Octane, 2-bromo- | 92.954 | 1.391 | 0.776 | No | No | No | Very poorly soluble |

| 6 | 4H-Pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl- | 83.475 | 0.476 | -0.3 | No | No | No | Highly soluble |

| 7 | Octanal dimethyl acetal | 94.608 | 1.614 | 0.704 | No | No | No | Poorly soluble |

| 8 | Catechol | 86.856 | 1.682 | -0.318 | No | No | No | Highly soluble |

| 9 | 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural | 95.848 | 1.172 | -0.361 | No | No | No | Highly soluble |

| 10 | Benzene, 1,3-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)- | 94.226 | 1.503 | 0.561 | No | No | No | Very poorly soluble |

| 11 | Isobornyl acetate | 95.366 | 1.855 | 0.553 | No | No | No | Poorly soluble |

| 12 | 2-Cyclopenten-1-one, 3-ethyl-2-hydroxy- | 93.736 | 1.588 | 0.362 | No | No | No | Highly soluble |

| 13 | α-Terpinyl acetate | 96.295 | 1.626 | 0.429 | No | No | No | Slightly soluble |

| 14 | 1,2,3-Benzenetriol | 83.549 | 1.122 | -0.441 | No | No | No | Moderately soluble |

| 15 | 1,3-Propanediol, 2-(hydroxymethyl)-2-nitro- | 52.503 | -0.325 | -0.908 | No | No | No | Highly soluble |

| 16 | 3-Deoxy-d-mannoic lactone | 65.925 | 0.389 | -0.43 | No | No | No | Highly soluble |

| 17 | Diethyltoluamide | 93.683 | 1.192 | 0.358 | No | No | No | Slightly soluble |

| 18 | Octanal, 2-(phenylmethylene)- | 94.782 | 1.652 | 0.686 | No | No | No | Very poorly soluble |

| 19 | Benzyl Benzoate | 95.835 | 1.43 | 0.282 | No | No | No | Poorly soluble |

| 20 | 7,10,13-Hexadecatrienoic acid | 93.523 | 1.579 | 1.579 | No | No | No | Very poorly soluble |

Predicted toxicity profiles of the compounds

The toxicity prediction results shown in table 5 indicate that the 20 selected compounds from nanoherbal senduduk bulu, which passed clinical suitability based on Lipinski's rule, range from the category of harmful if swallowed (Class 3) to non-toxic (Class 6). Two compounds classified as harmful, if swallowed, are catechol and 1,2,3-benzenetriol, with LD50 values of 100 and 300 mg/kg body weight, respectively. Catechol, a phenolic compound, is known to cause liver and kidney damage at high doses, as well as irritation to the skin and respiratory tract [44]. Meanwhile, one compound is classified as non-toxic, namely 7,10,13-Hexadecatrienoic acid, with an LD50 value of 10,000 mg/kg body weight. This compound is a fatty acid commonly found in plants and vegetable oils. The remaining 17 compounds are predicted to have potential toxicity, falling within class 4 and 5 categories.

Based on the toxicity predictions shown in table 6, 11 selected compounds were found to have no toxic potential, while 9 others were predicted to pose toxicity risks. α-Terpinyl acetate is the only compound exhibiting hepatotoxic activity, indicating that it may cause liver damage either through oxidative stress pathways or disruption of liver enzymes [45]. 6 compounds, including thymine, octane, 2-bromo-, catechol, 5-hydroxymethylfurfural, benzene, 1,3-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-, and 1,2,3-benzenetriol, were identified as having potential carcinogenicity. This carcinogenicity suggests that these compounds may promote uncontrolled cell growth and increase cancer risk [46]. Meanwhile, compounds such as 4H-pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl-, 5-hydroxymethylfurfural, 1,2,3-benzenetriol, and benzyl benzoate were found to exhibit mutagenic activity, meaning they have the potential to induce mutations in genetic material. These mutations are linked to an increased risk of genetic disorders due to changes in DNA that can affect key proteins regulating the cell cycle [47]. On the other hand, the predictions showed no compounds causing immunotoxicity or cytotoxicity, which is a favourable outcome, as these toxicities often pose significant risks in long-term therapies.

The toxicity assessment results of the 20 compounds derived from nanoherbal senduduk bulu demonstrate a significant variation in toxicity risk. This highlights the considerable differences in the pharmacological and toxicological potential of these compounds, necessitating thorough evaluation before therapeutic use [6]. Overall, while some selected compounds from nanoherbal senduduk bulu exhibit favourable safety profiles, others that show toxicity potential require further investigation. In vivo studies are crucial to validate these predictions and to gain a deeper understanding of the toxicity mechanisms and safe dosage levels of these compounds before their application in clinical therapy.

Predicted bioactivity of the nanoherbal senduduk bulu compounds based on the PASS online test

The predicted biological activities using the PASS online assay, based on probability of activity (Pa) and probability of inactivity (Pi) shown in table 7, reveal various levels of biological activities that can be harnessed for therapeutic development, particularly for cancer and inflammation treatments [48]. Probabilities were calculated for each compound and its biological targets, such as JAK2 expression inhibitors, apoptosis inducers, and others. The Pa value indicates the likelihood of a compound exhibiting a specific biological activity, while the Pi value reflects the probability of inactivity. Compounds like 2-Cyclopenten-1-one, 2-hydroxy-and Benzene, 1,3-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-exhibit potential as JAK2 inhibitors, a known target in cancer therapy, with respective Pa values of 0.806 and 0.749. The JAK2/STAT pathway plays a key role in cancer cell proliferation, and inhibiting JAK2 can suppress tumour growth and promote apoptosis, particularly in cases of leukaemia and solid tumours [49]. Additionally, compounds such as 7,10,13-Hexadecatrienoic acid and Octanal, 2-(phenylmethylene)-show potential as BRAF inhibitors, commonly found in melanoma, with Pa values of 0.892 and 0.825, respectively. Furthermore, several compounds, including Glycerin, Thymine, 1,2,3-Benzenetriol, and 3-Deoxy-d-mannoic lactone, are predicted to enhance the expression of TP53, a tumour suppressor gene. TP53 regulates cell cycles and apoptosis, and increasing TP53 expression can induce the death of mutated cancer cells [50]. Apoptosis induction is also a primary strategy in cancer therapy, with 4H-Pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl-showing strong activity as an apoptosis inducer (Pa = 0.858) and antineoplastic agent (Pa = 0.737). Additionally, the compound with the highest anti-inflammatory and TNF inhibition properties (Pa = 0.804) is 7,10,13-Hexadecatrienoic acid, highlighting its potential in mitigating chronic inflammation, often linked with cancer progression, by suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokines [51].

The screening results highlight several compounds with potential as anticancer agents through diverse mechanisms. 7,10,13-Hexadecatrienoic acid and 1,2,3-Benzenetriol emerge as strong candidates, exhibiting various antitumor activities with high values. Although the screening suggests these compounds hold promise, further exploration is needed through in vitro and in vivo studies in the laboratory to assess their efficacy and safety.

Table 5: Predicted toxicology levels of the compounds nanoherbal senduduk bulu

| No | Compounds name | Predicted LD50 | Predicted toxicity class | Average similarity | Prediction accuracy |

| 1 | 2-Cyclopenten-1-one, 2-hydroxy- | 400 mg/kg | Four (harmful) | 66.52% | 68.07% |

| 2 | Glycerin | 4090 mg/kg | Five (possibly hazardous) | 100% | 100% |

| 3 | 2-Hydroxy-gamma-butyrolactone | 1510 mg/kg | Four (harmful) | 71.67% | 69.26% |

| 4 | Thymine | 1923 mg/kg | Four (harmful) | 57.72% | 67.38% |

| 5 | Octane, 2-bromo- | 1190 mg/kg | Four (harmful) | 100% | 100% |

| 6 | 4H-Pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl- | 595 mg/kg | Four (harmful) | 60.38% | 68.07% |

| 7 | Octanal dimethyl acetal | 5000 mg/kg | Five (possibly hazardous) | 100% | 100% |

| 8 | Catechol | 100 mg/kg | Three (harmful if ingested) | 100% | 100% |

| 9 | 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural | 2500 mg/kg | Five (possibly hazardous) | 100% | 100% |

| 10 | Benzene, 1,3-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)- | 3100 mg/kg | Five (possibly hazardous) | 100% | 100% |

| 11 | Isobornyl acetate | 3100 mg/kg | Five (possibly hazardous) | 100% | 100% |

| 12 | 2-Cyclopenten-1-one, 3-ethyl-2-hydroxy- | 2000 mg/kg | Four (harmful) | 78% | 69.26% |

| 13 | α-Terpinyl acetate | 4800 mg/kg | Five (possibly hazardous) | 100% | 100% |

| 14 | 1,2,3-Benzenetriol | 300 mg/kg | Three (harmful if ingested) | 100% | 100% |

| 15 | 1,3-Propanediol, 2-(hydroxymethyl)-2-nitro- | 845 mg/kg | Four (harmful) | 63.56% | 68.07% |

| 16 | 3-Deoxy-d-mannoic lactone | 1590 mg/kg | Four (harmful) | 75.34% | 69.26% |

| 17 | Diethyltoluamide | 1170 mg/kg | Four (harmful) | 100% | 100% |

| 18 | Octanal, 2-(phenylmethylene)- | 2300 mg/kg | Five (possibly hazardous) | 100% | 100% |

| 19 | Benzyl Benzoate | 1000 mg/kg | Four (harmful) | 100% | 100% |

| 20 | 7,10,13-Hexadecatrienoic acid | 10000 mg/kg | Six (nontoxic) | 100% | 100% |

Table 6: Predicted organ toxicity of the compounds from nanoherbal senduduk bulu

| No | Compounds | Organ toxicity |

| Hepatotoxicity | ||

| 1 | 2-Cyclopenten-1-one, 2-hydroxy- | Inactive |

| 2 | Glycerin | Inactive |

| 3 | 2-Hydroxy-gamma-butyrolactone | Inactive |

| 4 | Thymine | Inactive |

| 5 | Octane, 2-bromo- | Inactive |

| 6 | 4H-Pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl- | Inactive |

| 7 | Octanal dimethyl acetal | Inactive |

| 8 | Catechol | Inactive |

| 9 | 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural | Inactive |

| 10 | Benzene, 1,3-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)- | Inactive |

| 11 | Isobornyl acetate | Inactive |

| 12 | 2-Cyclopenten-1-one, 3-ethyl-2-hydroxy- | Inactive |

| 13 | α-Terpinyl acetate | Active |

| 14 | 1,2,3-Benzenetriol | Inactive |

| 15 | 1,3-Propanediol, 2-(hydroxymethyl)-2-nitro- | Inactive |

| 16 | 3-Deoxy-d-mannoic lactone | Inactive |

| 17 | Diethyltoluamide | Inactive |

| 18 | Octanal, 2-(phenylmethylene)- | Inactive |

| 19 | Benzyl Benzoate | Inactive |

| 20 | 7,10,13-Hexadecatrienoic acid | Inactive |

Table 7: Prediction biological activity compounds of nanoherbal senduduk bulu by PASS online test

| No | Compound name | Biological activity | Pa | Pi | Criteria |

| 1 | 2-Cyclopenten-1-one, 2-hydroxy- | JAK2 expression inhibitor | 0.806 | 0.008 | High |

| MMP9 expression inhibitor | 0.696 | 0.007 | Low | ||

| TP53 expression enhancer | 0.690 | 0.028 | Low | ||

| Macrophage colony stimulating factor agonist | 0.677 | 0.017 | Low | ||

| Apoptosis agonist | 0.665 | 0.019 | Low | ||

| Antineoplastic (multiple myeloma) | 0.509 | 0.009 | Low | ||

| Cytochrome P450 stimulant | 0.486 | 0.030 | Low | ||

| BRAF expression inhibitor | 0.437 | 0.011 | Low | ||

| Caspase 3 stimulant | 0.441 | 0.038 | Low | ||

| Antineoplastic (breast cancer) | 0.430 | 0.027 | Low | ||

| Antimetastatic | 0.387 | 0.050 | Low | ||

| 2 | Glycerin | Macrophage colony stimulating factor agonist | 0,878 | 0,003 | High |

| TP53 expression enhancer | 0,736 | 0,019 | High | ||

| BRAF expression inhibitor | 0.712 | 0,003 | High | ||

| JAK2 expression inhibitor | 0,624 | 0,028 | Low | ||

| Antiinflammatory | 0,558 | 0,041 | Low | ||

| MMP9 expression inhibitor | 0,531 | 0,024 | Low | ||

| TNF expression inhibitor | 0,514 | 0,027 | Low | ||

| Caspase 8 stimulant | 0,454 | 0,029 | Low | ||

| Caspase 3 stimulant | 0,421 | 0,044 | Low | ||

| Cytochrome P450 stimulant | 0,418 | 0.048 | Low | ||

| 3 | 2-Hydroxy-gamma-butyrolactone | Macrophage colony stimulating factor agonist | 0.699 | 0.014 | Low |

| TP53 expression enhancer | 0.636 | 0.040 | Low | ||

| Caspase 8 stimulant | 0.573 | 0.009 | Low | ||

| MMP9 expression inhibitor | 0.519 | 0.026 | Low | ||

| 4 | Thymine | TP53 expression enhancer | 0.728 | 0.021 | High |

| Cytochrome P450 stimulant | 0.705 | 0.006 | High | ||

| TNF expression inhibitor | 0.441 | 0.044 | Low | ||

| 5 | Octane, 2-bromo- | JAK2 expression inhibitor | 0.481 | 0.058 | Low |

| MMP9 expression inhibitor | 0.381 | 0.058 | Low | ||

| 6 | 4H-Pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl- | Apoptosis agonist | 0.868 | 0.005 | High |

| Antineoplastic | 0.737 | 0.020 | High | ||

| JAK2 expression inhibitor | 0.730 | 0.014 | High | ||

| Antioxidant | 0.587 | 0.005 | Low | ||

| TP53 expression enhancer | 0.603 | 0.049 | Low | ||

| MMP9 expression inhibitor | 0.571 | 0.019 | Low | ||

| Macrophage colony stimulating factor agonist | 0.581 | 0.037 | Low | ||

| Caspase 8 stimulant | 0.544 | 0.011 | Low | ||

| 7 | Octanal dimethyl acetal | BRAF expression inhibitor | 0.608 | 0.005 | Low |

| JAK2 expression inhibitor | 0.559 | 0.040 | Low | ||

| Antineoplastic | 0.502 | 0.071 | Low | ||

| TP53 expression enhancer | 0.504 | 0.088 | Low | ||

| Caspase 3 stimulant | 0.365 | 0.066 | Low | ||

| 8 | Catechol | JAK2 expression inhibitor | 0.910 | 0.003 | High |

| TP53 expression enhancer | 0.731 | 0.020 | High | ||

| BRAF expression inhibitor | 0.553 | 0.006 | Low | ||

| Caspase 8 stimulant | 0.552 | 0.010 | Low | ||

| Antioxidant | 0.501 | 0.007 | Low | ||

| Antiinflammatory | 0.521 | 0.051 | Low | ||

| 9 | 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural | Macrophage colony stimulating factor agonist | 0.655 | 0.021 | Low |

| Antineoplastic | 0.644 | 0.036 | Low | ||

| TP53 expression enhancer | 0.636 | 0.039 | Low | ||

| Apoptosis agonist | 0.409 | 0.069 | Low | ||

| 10 | Benzene, 1,3-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)- | JAK2 expression inhibitor | 0.749 | 0.013 | High |

| BRAF expression inhibitor | 0.591 | 0.005 | Low | ||

| Antiinflammatory | 0.614 | 0.029 | Low | ||

| HERG 1 channel blocker | 0.558 | 0.014 | Low | ||

| MMP9 expression inhibitor | 0.539 | 0.023 | Low | ||

| TNF expression inhibitor | 0.539 | 0.022 | Low | ||

| 11 | Isobornyl acetate | Transcription factor NF kappa B stimulant | 0.521 | 0.019 | Low |

| TNF expression inhibitor | 0.517 | 0.026 | Low | ||

| MMP9 expression inhibitor | 0.513 | 0.026 | Low | ||

| Antineoplastic | 0.474 | 0.079 | Low | ||

| Apoptosis agonist | 0.441 | 0.055 | Low | ||

| 12 | 2-Cyclopenten-1-one, 3-ethyl-2-hydroxy- | Apoptosis agonist | 0.708 | 0.014 | High |

| Macrophage colony stimulating factor agonist | 0.661 | 0.019 | Low | ||

| TP53 expression enhancer | 0.664 | 0.033 | Low | ||

| Antineoplastic | 0.648 | 0.035 | Low | ||

| MMP9 expression inhibitor | 0.615 | 0.014 | Low | ||

| JAK2 expression inhibitor | 0.633 | 0.026 | Low | ||

| TNF expression inhibitor | 0.514 | 0.027 | Low | ||

| 13 | α-Terpinyl acetate | Antiinflammatory | 0.693 | 0.017 | Low |

| Antineoplastic | 0.576 | 0.050 | Low | ||

| Macrophage colony stimulating factor agonist | 0.506 | 0.062 | Low | ||

| Cytochrome P450 stimulant | 0.335 | 0.089 | Low | ||

| 14 | 1,2,3-Benzenetriol | JAK2 expression inhibitor | 0.898 | 0.003 | High |

| Apoptosis agonist | 0.755 | 0.010 | High | ||

| Macrophage colony stimulating factor agonist | 0.746 | 0.008 | High | ||

| TP53 expression enhancer | 0.744 | 0.018 | High | ||

| MMP9 expression inhibitor | 0.705 | 0.006 | High | ||

| Antioxidant | 0.655 | 0.004 | Low | ||

| TNF expression inhibitor | 0.581 | 0.015 | Low | ||

| Antineoplastic | 0.572 | 0.051 | Low | ||

| BRAF expression inhibitor | 0.511 | 0.008 | Low | ||

| Caspase 3 stimulant | 0.507 | 0.026 | Low | ||

| 15 | 1,3-Propanediol, 2-(hydroxymethyl)-2-nitro- | Macrophage colony stimulating factor agonist | 0.776 | 0.006 | High |

| Chemosensitizer | 0.520 | 0.017 | Low | ||

| JAK2 expression inhibitor | 0.541 | 0.044 | Low | ||

| 16 | 3-Deoxy-d-mannoic lactone | Antineoplastic | 0.822 | 0.009 | High |

| TP53 expression enhancer | 0.775 | 0.014 | High | ||

| Immunostimulant | 0.654 | 0.018 | Low | ||

| Chemosensitizer | 0.504 | 0.019 | Low | ||

| MMP9 expression inhibitor | 0.415 | 0.046 | Low | ||

| TNF expression inhibitor | 0.419 | 0.051 | Low | ||

| Apoptosis antagonist | 0.371 | 0.010 | Low | ||

| Antioxidant | 0.348 | 0.017 | Low | ||

| 17 | Diethyltoluamide | Macrophage colony stimulating factor agonist | 0.600 | 0.032 | Low |

| MMP9 expression inhibitor | 0.416 | 0.046 | Low | ||

| JAK2 expression inhibitor | 0.416 | 0,080 | Low | ||

| Caspase 3 stimulant | 0.324 | 0.098 | Low | ||

| Caspase 8 stimulant | 0.336 | 0.101 | Low | ||

| 18 | Octanal, 2-(phenylmethylene)- | BRAF expression inhibitor | 0.825 | 0.002 | High |

| Macrophage colony stimulating factor agonist | 0.746 | 0.009 | High | ||

| MMP9 expression inhibitor | 0.651 | 0.010 | Low | ||

| JAK2 expression inhibitor | 0.621 | 0.028 | Low | ||

| TP53 expression enhancer | 0.623 | 0.041 | Low | ||

| Apoptosis agonist | 0.536 | 0.034 | Low | ||

| 19 | Benzyl Benzoate | JAK2 expression inhibitor | 0.615 | 0,029 | Low |

| Caspase 8 stimulant | 0.446 | 0.032 | Low | ||

| Antiinflammatory | 0.459 | 0.070 | Low | ||

| Caspase 3 stimulant | 0.401 | 0.050 | Low | ||

| 20 | 7,10,13-Hexadecatrienoic acid | Macrophage colony stimulating factor agonist | 0.892 | 0.002 | High |

| BRAF expression inhibitor | 0.828 | 0.002 | High | ||

| Antiinflammatory | 0.804 | 0.006 | High | ||

| TP53 expression enhancer | 0.731 | 0.020 | High | ||

| TNF expression inhibitor | 0.713 | 0.006 | High | ||

| Apoptosis agonist | 0.628 | 0.023 | Low | ||

| MMP9 expression inhibitor | 0.600 | 0.016 | Low | ||

| Caspase 8 stimulant | 0.579 | 0.008 | Low | ||

| Chemoprotective | 0.349 | 0.030 | Low |

Table 8: Residues and binding energy of ligand and AKT1 interaction

| No | Ligand | Interaction type | Binding energy (Kcl/mol) | |||

| Hydrogen bond | Hydrophobic | Electrostatis | ||||

| Hydrogen bond | Carbon hydrogen bond | |||||

| Positive control | ||||||

| 1 | Borussertib (control) | TYR18 TYR272 THR291 PHE293 |

ASN279 | GLY294 PHE293 LYS297 LYS20 |

LYS276 | -11.5 |

| Bioactive components of the nanoherbal senduduk bulu | ||||||

| 2 | 2-Cyclopenten-1-one, 2-hydroxy- | LEU275 | - | LEU316 VAL330 |

- | -5.1 |

| 3 | Glycerin | GLY294 TYR272 ASN279 THR291 |

- | - | - | -4.2 |

| 4 | 2-Hydroxy-gamma-butyrolactone | ASN279 THR291 PHF293 ASP292 GLY294 |

- | - | - | -4.8 |

| 5 | Thymine | ALA317 LEU275 |

GLY334 | LYS276 TYR315 LEU316 |

- | -5.5 |

| 6 | Octane, 2-bromo- | - | - | TRP333 TYR18 VAL330 LEU316 VAL320 ALA317 |

- | -4.0 |

| 7 | 4H-Pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl- | - | - | ALA317 VAL330 VAL320 LEU316 TYR18 |

- | -4.1 |

| 8 | Octanal dimethyl acetal | LEU275 | GLY334 VAL330 |

TYR18 | - | -4.4 |

| 9 | Catechol | - | - | LEU316 | - | -5.7 |

| 10 | 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural | LEU275 | - | LEU316 | - | -5.1 |

| 11 | Benzene, 1,3-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)- | - | - | - | ASP274 | -5.7 |

| 12 | Isobornyl acetate | ARG15 | GLU17 | ARG15 | - | -5.5 |

| 13 | 2-Cyclopenten-1-one, 3-ethyl-2-hydroxy- | - | - | LEU316 LYS276 |

- | -5.4 |

| 14 | α-Terpinyl acetate | - | - | TYR272 | - | -5.7 |

| 15 | 1,2,3-Benzenetriol | ASP274 LEU275 |

- | LEU316 | - | -5.9 |

| 16 | 1,3-Propanediol, 2-(hydroxymethyl)-2-nitro- | ARG15 GLY16 GLU85 |

- | - | - | -3.9 |

| 17 | 3-Deoxy-d-mannoic lactone | PHE293 THR291 ASP274 |

ASP292 | - | - | -5.3 |

| 18 | Diethyltoluamide | - | - | PHE293 MET281 LEU156 VAL164 |

GLU234 MET281 |

-5.0 |

| 19 | Octanal, 2-(phenylmethylene)- | LYS276 | - | TYR272 PHE293 |

- | -5.4 |

| 20 | Benzyl Benzoate | ASN279 GLY294 PHE293 |

- | PHE293 | ASP274 | -7.0 |

| 21 | 7,10,13-Hexadecatrienoic acid | THR291 TYR272 PHE293 GLY294 |

- | VAL164 LEU156 |

- | -5.7 |

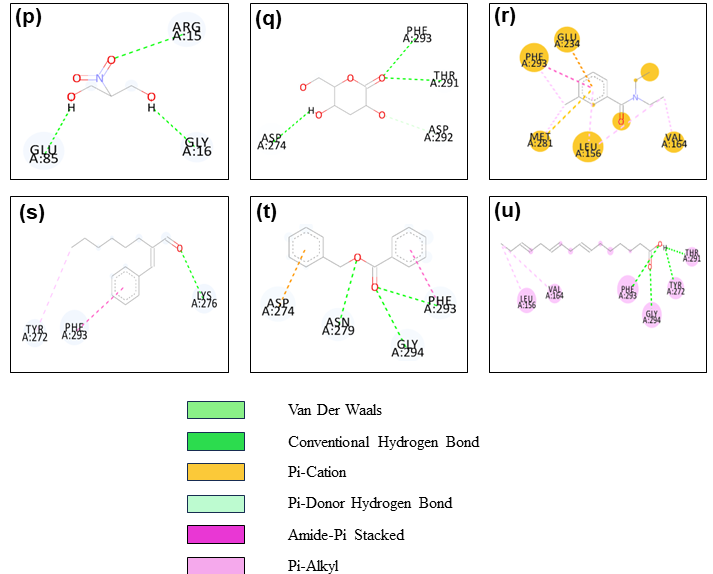

Molecular interactions of bioactive compounds from nanoherbal senduduk bulu with AKT1

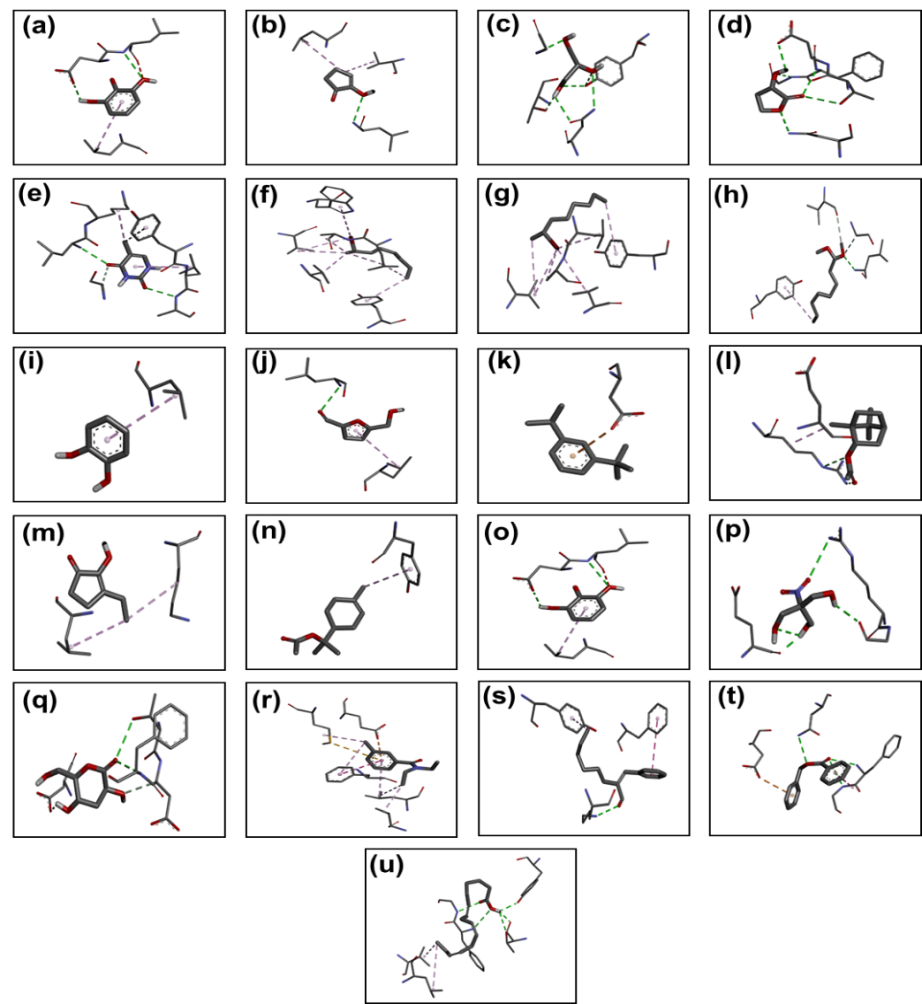

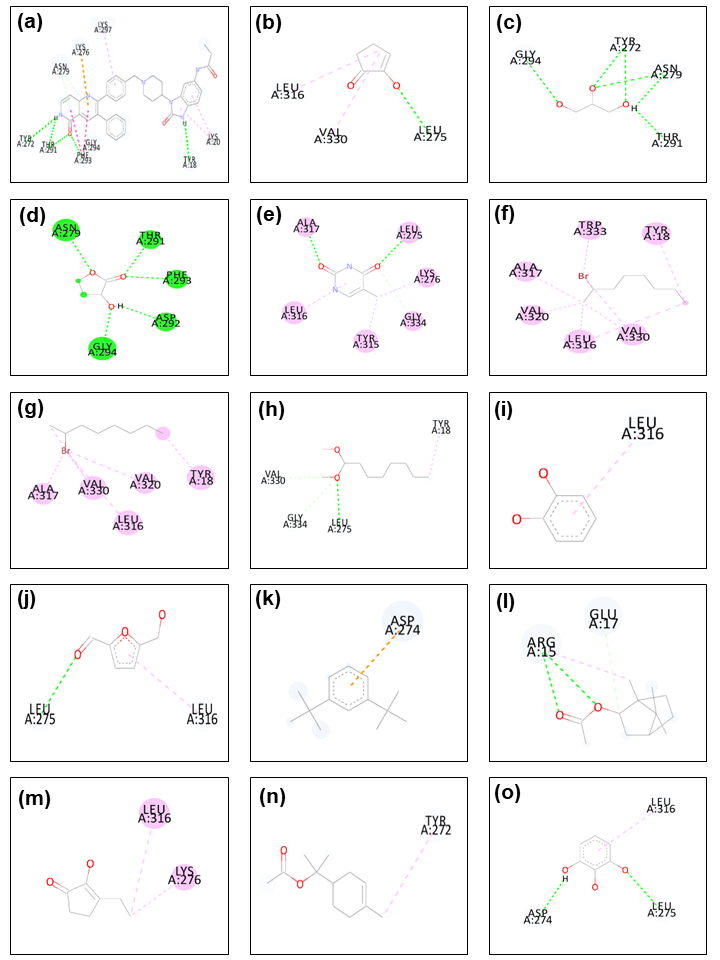

Based on the results of molecular docking analysis comparing the control compound borussertib with various bioactive compounds from nanoherbal senduduk bulu as shown in table 8 (fig. 3 and 4), there is a significant variation in the types of interactions and binding energies with the target protein AKT1. Borussertib, with the highest binding energy (-11.5 kcal/mol), forms strong interactions through hydrogen bonds, electrostatic, and hydrophobic interactions with key residues such as TYR18, TYR272, THR291, and PHE293. This indicates that borussertib has a very strong affinity for the AKT1 protein. The effectiveness of borussertib as a potent AKT1 inhibitor is supported by its interactions with important residues that play a role in inhibiting phosphorylation activity, which in turn affects the cell cycle and apoptosis. In previous studies, borussertib has been shown to suppress AKT1 phosphorylation activity, particularly in cancer cells dependent on AKT1, and significantly induce apoptosis [52–54]. The high binding energy of borussertib highlights its ability to stabilize the AKT1 structure in its inactive form, thereby inhibiting the signalling pathway regulated by AKT1. In the context of cancer therapy, AKT1 inhibition has significant clinical implications, as AKT1 is a key protein in signalling pathways that regulate cell growth and survival, which are often overactivated in cancer cells [55].

When compared to the bioactive compounds from senduduk bulu, compounds such as 1,2,3-Benzenetriol (-5.9 kcal/mol) and Benzyl benzoate (-7.0 kcal/mol) exhibit relatively moderate binding energies, although not as high as borussertib. These compounds still demonstrate significant interactions with key residues, including ASP274, LEU275, ASN279, GLY294, and ASP274. This suggests that, despite their lower binding affinities compared to borussertib, these compounds may still have potential to modulate AKT1 activity, particularly in the context of combination therapies where they could be used alongside stronger inhibitors to achieve synergistic effects.

Other compounds, such as glycerin (-4.2 kcal/mol) and octane, 2-bromo (-4.0 kcal/mol), show much lower binding energies and limited interactions with the target protein, mostly through hydrophobic interactions. This indicates a low affinity for AKT1, which is likely to result in less significant biological activity. Meanwhile, compounds like thymine (-5.5 kcal/mol) and 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural (-5.1 kcal/mol) demonstrate moderate binding energies, with a broader range of hydrogen and hydrophobic interactions, suggesting these compounds may have moderate activity towards AKT1.

Fig. 3: Visualization 3D of interactions borussertib and bioactive compounds from nanoherbal senduduk bulu against the AKT1 protein. (a) borussertib; (b) 2-Cyclopenten-1-one, 2-hydroxy-; (c) Glycerin; (d) 2-Hydroxy-gamma-butyrolactone; (e) Thymine; (f) Octane, 2-bromo-; (g) 4H-Pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl-; (h) Octanal dimethyl acetal; (i) Catechol; (j) 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural; (k) Benzene, 1,3-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-; (l) Isobornyl acetate; (m) 2-Cyclopenten-1-one, 3-ethyl-2-hydroxy-; (n) α-Terpinyl acetate; (o) 1,2,3-Benzenetriol; (p) 1,3-Propanediol, 2-(hydroxymethyl)-2-nitro-; (q) 3-Deoxy-d-mannoic lactone; (r) Diethyltoluamide; (s) Octanal, 2-(phenylmethylene)-; (t) Benzyl benzoate; (u) 7,10,13-Hexadecatrienoic acid

From these results, it can be concluded that compounds with higher binding energies, such as borussertib, generally exhibit stronger affinity and interactions with the target protein, making them more effective as AKT1 inhibitors. In contrast, compounds with lower binding energies, such as glycerin and octane, 2-bromo, demonstrate weaker affinity and are predicted to have limited biological activity. However, compounds with moderate affinity, such as 1,2,3-Benzenetriol and Benzyl benzoate, although not as potent as borussertib, still hold potential for contributing to AKT1 modulation, particularly when used in combination with other compounds. Overall, while the bioactive compounds from senduduk bulu may not possess the same potential as borussertib as standalone AKT1 inhibitors, they still show promising potential for modulating the AKT1 signalling pathway, which could be utilised in multi-target or combination therapeutic approaches. This study provides valuable preliminary insights into the potential interactions of bioactive compounds from senduduk bulu with the AKT1 protein through computational approaches, such as molecular docking and virtual screening. Although these findings are intriguing, the study also presents several important limitations, primarily the reliance on in silico methods, which may yield predictions that do not accurately reflect the actual biological activity within the body. Therefore, further experimental validation, including in vitro and in vivo studies, is essential to ascertain the therapeutic potential and safety of these compounds. Additionally, while Lipinski's rule is employed to predict the viability of compounds as drug candidates, successful drug development requires a more nuanced consideration of various factors.

Fig. 4: Visualization 2D interactions borussertib and bioactive compounds from nanoherbal senduduk bulu against the AKT1 protein. (a) borussertib; (b) 2-Cyclopenten-1-one, 2-hydroxy-; (c) Glycerin; (d) 2-Hydroxy-gamma-butyrolactone; (e) Thymine; (f) Octane, 2-bromo-; (g) 4H-Pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl-; (h) Octanal dimethyl acetal; (i) Catechol; (j) 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural; (k) Benzene, 1,3-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-; (l) Isobornyl acetate; (m) 2-Cyclopenten-1-one, 3-ethyl-2-hydroxy-; (n) α-Terpinyl acetate; (o) 1,2,3-Benzenetriol; (p) 1,3-Propanediol, 2-(hydroxymethyl)-2-nitro-; (q) 3-Deoxy-d-mannoic lactone; (r) Diethyltoluamide; (s) Octanal, 2-(phenylmethylene)-; (t) Benzyl Benzoate; (u) 7,10,13-Hexadecatrienoic acid

CONCLUSION

This research successfully identified 20 out of 36 compounds from senduduk bulu that meet the criteria to be considered as potential drugs and demonstrated their potential as AKT1 inhibitors in the context of cancer treatment through in silico analysis. Molecular docking tests revealed promising interactions between these compounds and the target protein AKT1, with affinity values that, while not surpassing that of the control drug borussertib, remain encouraging. ADMET analysis further highlighted that several compounds possess characteristics indicative of high oral bioavailability. Metabolically, these compounds are not substrates for the CYP2D6 enzyme in the liver, and none function as inhibitors of the OCT2 protein in the kidneys. The majority of the compounds from senduduk bulu exhibit good water solubility and are likely to be well absorbed by the human intestine. Regarding toxicity, there are indications of varying toxicity risks ranging from non-hazardous to hazardous, with some presenting potential risks for hepatotoxicity, mutagenicity, and carcinogenicity.

These findings underscore the potential of compounds from senduduk bulu in the development of innovative cancer therapies, while also highlighting the need for further research to experimentally explore the biological effects of these compounds. Therefore, this study provides a solid foundation for future development, which could include in vitro and in vivo studies to validate the efficacy and safety of these compounds. Through these efforts, it is hoped that these findings can be translated into clinical applications, potentially enhancing cancer treatment strategies and improving outcomes for patients battling this disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We extend our deepest gratitude to the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology for their generous support through the PMDSU (Master to Doctoral Education) Batch VII Scholarship Program. This invaluable assistance has greatly facilitated our research and academic progress at the Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Universitas Sumatera Utara. We are sincerely thankful for this opportunity and for the guidance provided, which has been instrumental in our academic journey.

FUNDING

This work received financial support from The Directorate of Research, Technology, and Community Service (DRTPM) Kemendikbudristek grant number: 87/UN5.4.10. S/PPM/KP-DRTPM/2024.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

As the lead author, Dina Khairani spearheaded the project, designed the research framework, drafted the initial manuscript, and ensured its coherence. Syafruddin Ilyas, as the corresponding author, polished the content, ensured the manuscript's accuracy and proper English gmar, and managed the submission process and journal correspondence. Dini Prastyo Waty as co-author contributed writing and editing. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript, contributed to critical discussions, and provided valuable input to enhance the paper's quality.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors hereby declare that there are no conflicts of interest, either financial or non-financial, that could have influenced the research outcomes or the interpretation of data in this study.

REFERENCES

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209-49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660, PMID 33538338.

Zaira G, Asia G. Breast cancer: the road to a personalized prevention. IgMin Res. 2024;2(3):163-70. doi: 10.61927/igmin160.

Tarannum J, Manaswini P, Deekshitha C, Gaju RK, Shyam Sunder AS. Reproductive factors and breast cancer risk. Int J Med Rev. 2019;6(2):40-4. doi: 10.29252/IJMR-060203.

chen XR, Zhang Y Wu, Liu C Cui, Xu Y Ying, Shao Z Ming, Yu K da. Series immunotherapy and its racial specificity for breast cancer treatment in Asia: a Narrative Review. Lancet Reg Heal West Pacifi; 2024. p. 1-13.

Wu P, Hu YZ. PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway inhibitors in cancer: a perspective on clinical progress. Curr Med Chem. 2010;17(35):4326-41. doi: 10.2174/092986710793361234, PMID 20939811.

Joseph X, Akhil A, Arathi KB, Megha KB, Vandana U, Mohanan PV. Toxicity assessment of nanoparticle. In: Mohanan PV, Kappalli S, editors. Biomedical applications and toxicity of nanomaterials. Singapore: Springer; 2023. p. 401-23. Available from: doi: 10.1007/978-981-19-7834-0_16.

Mahalekshmi V, Balakrishnan N, Ajay Kumar TV, Parthasarathy V. In silico molecular screening and docking approaches on antineoplastic agent-irinotecan towards the marker proteins of colon cancer. Int J App Pharm. 2023;15(5):84-92. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2023v15i5.48523.

Fox EM, Kuba MG, Miller TW, Davies BR, Arteaga CL. Autocrine IGF-I/insulin receptor axis compensates for inhibition of AKT in ER-positive breast cancer cells with resistance to estrogen deprivation. Breast Cancer Res. 2013;15(4):R55. doi: 10.1186/bcr3449, PMID 23844554.

Ohmoto A, Yachida S. Current status of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors and future directions. Onco Targets Ther. 2017;10(5):5195-208. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S139336, PMID 29138572.

Stanzione F, Giangreco I, Cole JC. Use of molecular docking computational tools in drug discovery. Elsevier. Vol. 60; 2021. Progress in Medicinal Chemistry. 1st ed. p. 273-343. doi: 10.1016/bs.pmch.2021.01.004.

Carrella D, Manni I, Tumaini B, Dattilo R, Papaccio F, Mutarelli M. Computational drugs repositioning identifies inhibitors of oncogenic PI3K/AKT/P70S6K-dependent pathways among FDA-approved compounds. Oncotarget. 2016;7(37):58743-58. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11318, PMID 27542212.

Mursal M, Ahmad M, Hussain S, Faraz Khan M. Navigating the computational seas: a comprehensive overview of molecular docking software in drug discovery. In: Unravelling mol docking. Intech Open; 2024. doi: 10.5772/intechopen.1004802.

Chaudhary M, Tyagi K. A review on molecular docking and its application. Int J Adv Res. 2024;12(3):1141-53. doi: 10.21474/IJAR01/18505.

Bajpai P, Usmani S, Kumar R, Prakash O. Recent advances in anticancer approach of traditional medicinal plants: a novel strategy for cancer chemotherapy. Intelligent Pharmacy. 2024;2(3):291-304. doi: 10.1016/j.ipha.2024.02.001.

Tuginah SD, Lokaria E, Daun Harendong PAR. Bulu (Clidemia hirta) terhadap kadar kolestrol mencit (Mus musculus). J Biosilampari J Biol. 2020;3(1):1-6. doi: 10.31540/biosilampari.v3i1.972.

Petrovic S, Bita B, Barbinta Patrascu ME. Nanoformulations in pharmaceutical and biomedical applications: green perspectives. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(11):5842. doi: 10.3390/ijms25115842, PMID 38892030.

Gophane SR, Jadhao SR, Jamdhade PB. Bergenia ciliata: isolation of active flavonoids, GC-MS analysis, ADME study and inhibition activity of oxalate synthesizing enzymes. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2021;13(11):34-46. doi: 10.22159/ijpps.2021v13i11.42127.

Santoso P, Ilyas S, Midoen YH, Maliza R, Belahusna DF. Predictive bioactivity of compounds from Vitis gracilis leaf extract to counteract doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity via sirtuin 1 and adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase: an in-silico study. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2024;14(4):99-114. doi: 10.7324/JAPS.2024.167007.

Alam N, Banu N, Aziz MA, Barua N, Ruman U, Jahan I. Chemical profiling, pharmacological insights and in silico studies of methanol seed extract of Sterculia foetida. Plants (Basel). 2021;10(6):1135. doi: 10.3390/plants10061135, PMID 34205007.

Sri Satya MS, Suma BV, Aiswariya. Molecular docking and admet studies of ethanone, 1-(2-hydroxy-5-methyl phenyl) for anti-microbial properties. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2022;14(6):24-7. doi: 10.22159/ijpps.2022v14i6.44548.

Shuttle Worth A, Johnson SD. GC-MS/FID/EAD: a method for combining mass spectrometry with gas chromatography-electroantennographic detection. Front Ecol Evol. 2022;10:1-10. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2022.1042732.

Fiehn O. Metabolomics by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry: the combination of targeted and untargeted profiling. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2017;7:232-5. doi: 10.1002/0471142727.

Gomathi D, Kalaiselvi M, Ravikumar G, Devaki K, Uma C. GC-MS analysis of bioactive compounds from the whole plant ethanolic extract of evolvulus alsinoides (L.) L. J Food Sci Technol. 2015;52(2):1212-7. doi: 10.1007/s13197-013-1105-9, PMID 25694742.

Masera K, Hossain AK, Davies PA, Doudin K. Investigation of 2-butoxyethanol as biodiesel additive on fuel property and combustion characteristics of two neat biodiesels. Renew Energy. 2021;164:285-97. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2020.09.064.

Ahmed MU, Arise RO, Umaru IJ, Mohammed A. Antidiarheal activity of catechol and ethyl 5, 8,11,14,17-icosapentanoate-rich fraction of Annona senegalensis stem bark. J Tradit Complement Med. 2022;12(2):190-4. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2021.07.007, PMID 35528478.

Aljazy NA. Antioxidant activity and the laxative agent of red hawthorn (Crataegus sumbollis) in jam industry. J Surv Fish Sci. 2023;10(2):1257-71. doi: 10.17762/sfs.v10i2S.835.

Bitew M, Desalegn T, Demissie TB, Belayneh A, Endale M, Eswaramoorthy R. Pharmacokinetics and drug-likeness of antidiabetic flavonoids: molecular docking and DFT study. PLOS One. 2021;16(12):e0260853. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0260853, PMID 34890431.

Alqahtani MS, Kazi M, Alsenaidy MA, Ahmad MZ. Advances in oral drug delivery. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:618411. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.618411, PMID 33679401.

Kumari L, Choudhari Y, Patel P, Gupta GD, Singh D, Rosenholm JM. Advancement in solubilization approaches: a step towards bioavailability enhancement of poorly soluble drugs. Life (Basel). 2023;13(5):1099. doi: 10.3390/life13051099, PMID 37240744.

Mendie LE, Hemalatha S. Molecular docking of phytochemicals targeting GFRs as therapeutic sites for cancer: an in silico study. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2022;194(1):215-31. doi: 10.1007/s12010-021-03791-7, PMID 34988844.

Duran Iturbide NA, Diaz Eufracio BI, Medina Franco JL. In silico ADME/Tox profiling of natural products: a focus on biofacquim. ACS Omega. 2020;5(26):16076-84. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.0c01581, PMID 32656429.

Azman M, Sabri AH, Anjani QK, Mustaffa MF, Hamid KA. Intestinal absorption study: challenges and absorption enhancement strategies in improving oral drug delivery. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2022;15(8):975. doi: 10.3390/ph15080975, PMID 36015123.

Lennernas H. Regional intestinal drug permeation: biopharmaceutics and drug development. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2014;57(1):333-41. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2013.08.025, PMID 23988845.

Artursson P, Karlsson J. Correlation between oral drug absorption in humans and apparent drug permeability coefficients in human intestinal epithelial (Caco2) cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;175(3):880-5. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)91647-u, PMID 1673839.

Sawant Basak A, Rodrigues AD, Lech M, Doyonnas R, Kasaian M, Prasad B. Physiologically relevant, humanized intestinal systems to study metabolism and transport of small molecule therapeutics. Drug Metab Dispos. 2018;46(11):1581-7. doi: 10.1124/dmd.118.082784, PMID 30126862.

Teleanu RI, Preda MD, Niculescu AG, Vladacenco O, Radu CI, Grumezescu AM. Current strategies to enhance delivery of drugs across the blood–brain barrier. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14(5):987. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14050987, PMID 35631573.

Wang D, Poi MJ, Sun X, Gaedigk A, Leeder JS, Sadee W. Common CYP2D6 polymorphisms affecting alternative splicing and transcription: long-range haplotypes with two regulatory variants modulate CYP2D6 activity. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23(1):268-78. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt417, PMID 23985325.

Zanger UM, Schwab M. Cytochrome P450 enzymes in drug metabolism: regulation of gene expression, enzyme activities, and impact of genetic variation. Pharmacol Ther. 2013;138(1):103-41. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.12.007, PMID 23333322.

Koepsell H. Update on drug–drug interaction at organic cation transporters: mechanisms, clinical impact, and proposal for advanced in vitro testing. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2021;17(6):635-53. doi: 10.1080/17425255.2021.1915284, PMID 33896325.

Lapczuk Romanska J, Drozdzik M, Oswald S, Drozdzik M. Kidney drug transporters in pharmacotherapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(3):2856. doi: 10.3390/ijms24032856, PMID 36769175.

Nies AT, Koepsell H, Damme K, Schwab M. Organic cation transporters (OCTs, MATEs), in vitro and in vivo evidence for the importance in drug therapy. H and B Exp Pharmacol. 2011;201:105-67. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-14541-4_3, PMID 21103969.

Savjani KT, Gajjar AK, Savjani JK. Drug solubility: importance and enhancement techniques. Pharmacol. 2012;2012:195727. doi: 10.5402/2012/195727, PMID 22830056.

Munnangi SR, Youssef AA, Narala N, Lakkala P, Narala S, Vemula SK. Drug complexes: perspective from academic research and pharmaceutical market. Pharm Res. 2023;40(6):1519-40. doi: 10.1007/s11095-023-03517-w, PMID 37138135.

Rahman M, Rahaman S, Islam R, Rahman F, Mithi FM, Alqahtani T. Role of phenolic compounds in human disease: current. Molecules. 2022;27(233):1-36.

Lee Y, Park HG, Kim V, Cho MA, Kim H, Ho TH. Inhibitory effect of α-terpinyl acetate on cytochrome P450 2B6 enzymatic activity. Chem Biol Interact. 2018;289:90-7. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2018.04.029, PMID 29723517.

Sørli JB, Frederiksen M, Nikolov NG, Wedebye EB, Hadrup N. Identification of substances with a carcinogenic potential in spray-formulated engine/brake cleaners and lubricating products, available in the European Union (EU)-based on IARC and EU-harmonised classifications and QSAR predictions. Toxicology. 2022;477:153261. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2022.153261, PMID 35863487.

Melekhina VG, Mityanov VS, Komogortsev AN, Lichitski BV, Dudinov AA, Shirinian VZ. Condensation of 5-hydroxy-2-methyl-4H-pyran-4-one with arylglyoxals. Synthesis and properties of 2-aryl-1-(3-hydroxy-6-methyl-4-oxo-4H-pyran-2-yl)ethane-1,2-diones. Russ Chem Bull. 2018;67(10):1873-7. doi: 10.1007/s11172-018-2301-6.

Infanger D, Schmidt Trucksäss A. P value functions: an underused method to present research results and to promote quantitative reasoning. Stat Med. 2019;38(21):4189-97. doi: 10.1002/sim.8293, PMID 31270842.

Jin W. Metastasis, the transition of cancer stem cells, and chemo resistance of cancer by epithelial-mesenchymal transition. MDPI. 2020;9(217):1-23.

Rehman B, Abubakar M, Kiani MN, Ayyoub R. Analysis of genetic alterations in TP53 gene in breast cancer-a secondary publication. PAR. 2024;8(3):25-35. doi: 10.26689/par.v8i3.6720.

Moawadh MS. Molecular docking analysis of natural compounds as TNF-α inhibitors for Crohn’s disease management. Bioinformation. 2023;19(6):716-20. doi: 10.6026/97320630019716, PMID 37885792.

Weisner J, Landel I, Reintjes C, Uhlenbrock N, Trajkovic Arsic M, Dienstbier N. Preclinical efficacy of covalent-allosteric AKT inhibitor borussertib in combination with trametinib in KRAS-mutant pancreatic and colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2019;79(9):2367-78. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-2861, PMID 30858154.

Zhong HA, Goodwin DT. Selectivity studies and free energy calculations of AKT inhibitors. Molecules. 2024;29(6):1233. doi: 10.3390/molecules29061233, PMID 38542870.

Zhang Y, Zhang C, Li J, Jiang M, Guo S, Yang G. Inhibition of AKT induces p53/SIRT6/PARP1-dependent parthanatos to suppress tumor growth. Cell Commun Signal. 2022;20(1):1-21. doi: 10.1186/s12964-022-00897-1.

Rehan M, Beg MA, Parveen S, Damanhouri GA, Zaher GF. Computational insights into the inhibitory mechanism of human AKT1 by an orally active inhibitor, MK-2206. PLOS One. 2014;9(10):e109705. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109705, PMID 25329478.