Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 2, 2025, 456-467Original Article

CHITOSAN COATED SELENIUM-DONEPEZIL NANOPARTICLES AMELIORATE SCOPOLAMINE-INDUCED MEMORY IMPAIRMENT IN RATS

FARIBA HOUSHMAND1,2, ALAA A. HASHIM3, HUSSEIN ABDELAMIR MOHAMMAD4, FATEMEH DRISS5, FATEMEH IRANPOUR6, REZA AHMADI7, NARGES NAJAFI8, DHIYA ALTEMEMY9, PEGAH KHOSRAVIAN1*

1Medical Plants Research Center, Basic Health Sciences Institute, Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences, Shahrekord, Iran. 2Departments of Physiology and Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences, Shahrekord, Iran. 3Department of Anesthesia Techniques and Intensive Care, Al-Taff University Collegw, Karbala, Iraq. 4Department of Pharmaceutics, College of Pharmacy, University of Al-Qadisiyah, Iraq. 5Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Health, Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences, Shahrekord, Iran. 6Student Research Committee, Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences, Shahrekord, Iran. 7Clinical Biochemistry Research Center, Basic Health Sciences Institute, Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences, Shahrekord, Iran. 8Department of Biology, Shahrekord Branch, Islamic Azad University, Shahrekord, Iran. 9Department of Pharmaceutics, College of Pharmacy, Al-Zahraa University for Women, Karbala, Iraq

*Corresponding author: Pegah Khosravian; *Email: pegah.khosraviyan@gmail.com

Received: 29 Oct 2024, Revised and Accepted: 05 Feb 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: This study investigated the therapeutic potential of chitosan-coated Selenium-Donepezil Nanoparticles (SeNPs) in a scopolamine-induced rat model of Alzheimer's disease (AD).

Methods: Chitosan-coated SeNPs were synthesized and characterized using Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FE-SEM), Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS), Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR), and Energy-Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (EDAX). The therapeutic potential of SeNPs was evaluated in a scopolamine-induced rat model of AD by assessing spatial memory using the Morris Water Maze (MWM) test and passive avoidance test, as well as measuring oxidative stress markers, including the Ferric-Reducing Ability of Plasma (FRAP) and Malondialdehyde (MDA) levels.

Results: The selected formula (F2) of chitosan-coated SeNPs significantly improved spatial memory and reduced oxidative stress markers compared to scopolamine controls, suggesting a synergistic effect. The average size of F2 was approximately 200 nm, with a zeta potential of-20.4 mV. The loading efficiency of donepezil into F2 was 42.3±0.57%. In the MWM test, F2 significantly improved spatial memory and learning compared to the scopolamine group (p<0.01). F2 also ameliorated scopolamine-induced memory deficits in the passive avoidance test (p<0.05). Furthermore, F2 significantly increased FRAP levels and decreased MDA levels in both serum and brain tissue compared to the scopolamine group (p<0.05).

Conclusion: The results suggest that chitosan-coated SeNPs may offer a promising therapeutic approach for AD by targeting both oxidative stress and cholinergic dysfunction, warranting further investigation.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, Cognitive impairment, Memory enhancement, Nanoparticles, Oxidative stress

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i2.53076 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disorder marked by cognitive decline, memory loss, and behavioral changes [1, 2]. The complex pathophysiology involves β-amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, oxidative stress, and cholinergic dysfunction [2]. Current treatments offer limited efficacy, primarily managing symptoms rather than addressing the underlying causes of the disease [3].

Oxidative stress, an imbalance between Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) production and antioxidant defenses, plays a critical role in AD pathogenesis. ROS can damage cellular components, leading to neuronal dysfunction and death. Selenium, an essential trace element with potent antioxidant properties, has shown promise in mitigating oxidative stress and neurodegeneration in AD models [4]. Studies have linked low selenium levels with cognitive impairments in individuals with AD [5-7].

The central cholinergic system's pivotal role in learning and memory processes was first recognized in the 1970s [8, 9]. AD's activity is reduced, contributing to cognitive decline [10]. The disruption of the cholinergic system involves amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, and excessive acetylcholinesterase release, leading to decreased acetylcholine levels and memory/learning disorders [9, 11, 12]. Donepezil, an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, improves cognitive function in AD patients [3, 13].

Oxidative stress significantly contributes to age-related cognitive problems, including AD. Free radicals can damage mitochondrial components, increasing the production of harmful Amyloid Beta (Aβ) [14]. Developing novel nanoparticles with therapeutic antioxidant properties is crucial for managing neurological disorders [15, 16].

Selenium, a cofactor in redox regulation, exhibits potent antioxidant and neuroprotective functions in AD models [5, 6]. Age-related decline in selenium levels may contribute to neuropsychological decline in adults [17].

Nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems have gained attention for their potential to revolutionize therapeutics [18]. Nanocarriers can enhance drug efficacy, improve bioavailability, and reduce adverse side effects. Chitosan, a natural biocompatible polysaccharide, has emerged as a promising carrier for targeted drug delivery in AD treatment [19]. Nano-selenium has shown superior efficacy compared to other forms of selenium in regulating enzymes and reducing toxicity [20]. Selenium nanoparticles have garnered interest for their therapeutic potential due to their chemical stability, high biocompatibility, and low toxicity [19].

This study focuses on designing a mesoporous selenium nanoparticle system loaded with donepezil to enhance donepezil's brain delivery and improve scopolamine-induced memory and learning impairments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Material

This study utilized 56 male wistar rats (weighing 200-250 g, 3-4 mo old) obtained from the Pasteur Institute of Iran. The animals were housed in quadruple cages under standard conditions, with a 12 h light/dark cycle and a constant temperature of 23±1 °C. They had free access to food and water throughout the study. The ethics approval for this study was obtained from Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences (IR. SKUMS. REC.1399.032).

Reagents used in this study included donepezil hydrochloride, selenium dioxide, ascorbic acid and low molecular weight chitosan (all from Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and Cetyl Trimethyl Ammonium Bromide (CTAB) (98%, Sigma Aldrich, Seelze, Germany).

Preparation of mesoporous selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs)

To prepare mesoporous SeNPs, CTAB (100 mg) was dissolved in 46 ml of water at room temperature and stirred for 30 min at 800 rpm. Zinc (30 mg) was added to the solution and stirred for 120 min at 800 rpm. Sodium selenite solution (2 ml, 5 mmol) and ascorbic acid solution (2 ml, 20 mmol) were added, and the mixture was stirred for 2 h at 800 rpm. The solution was centrifuged at 800 rpm for 5 min and washed three times with water and ethanol. The precipitate was dispersed in 30 ml of ethanol and refluxed at 80 °C and 800 rpm for 24 h to remove CTAB. The SeNPs were then washed three times with water and dried [21].

Loading SeNPs with donepezil (F1)

SeNPs (50 mg) were dispersed in 5 ml of a solution containing 50 mg of donepezil.

The mixture was stirred at 800 rpm at room temperature under dark conditions for 24 h.

F1 nanoparticles were separated using centrifugation and dried using a freeze-dryer.

Chitosan coating of SeNPs (F2)

F1 nanoparticles (50 mg) were dispersed in 5 ml of deionized water.

Chitosan (5 mg) was dissolved in 2 ml of 0.1 M acetic acid and added dropwise to the nanoparticle solution.

The mixture was stirred for 24 h.

F2 nanoparticles were separated using centrifugation and dried using a freeze-dryer.

Preparation of SeNPs coated with chitosan (F3)

For animal studies, 44 mg of Se nanoparticles were coated with chitosan (F3) using the same method to prepare nanoparticles (without donepezil).

Evaluation of loading and release of donepezil

The amount of donepezil loaded into the SeNPs was determined by measuring the absorbance of the supernatant solution at 260 nm using a spectrophotometer. The loading efficiency and loading capacity were then calculated using specific formulas. These calculations provide insights into the effectiveness of incorporating the drug into the nanoparticles. The loading efficiency reveals the percentage of the initial drug successfully loaded into the nanoparticles, while the loading capacity indicates the amount of drug loaded per unit mass of nanoparticles:

Equation 1:

Equation 2:

Characterization of nanoparticles

The physicochemical properties of the prepared nanoparticles were characterized using various techniques:

Morphology: The morphology of the nanoparticles was assessed using FE-SEM (Tescan/Mira, Brno, Czech Republic).

Size and zeta potential: The particle size and zeta potential were measured using DLS (Mastersizer 2000, Malvern Instruments, Malvern, and Worcestershire, UK).

Porosity: The pore size and surface area of the mesoporous SeNPs were investigated using N2 adsorption-desorption analysis.

Chemical Structure: The chemical structure of the nanoparticles was analyzed using FTIR (Nicolet Magna IR-550).

Elemental Composition: The elemental composition of the nanoparticles was determined using EDAX coupled with FE-SEM [22].

Experimental design and dosage justification

The doses and concentrations for selenium, donepezil and other reagents were selected based on preliminary studies and previous literature to optimize therapeutic efficacy while minimizing potential toxicity. The preparation and administration of each compound adhered to established protocols to ensure consistency and reproducibility across experimental groups [22-24].

Animal groups

This study obtained 56 male wistar rats (200-250 g, 3-4 mo old) from the Pasteur Institute of Iran. The animals were housed in quadruple cages under standard conditions, with a 12 h light/dark cycle and a constant temperature of 23±1 °C. They had adequate access to food and water throughout the study.

The rats were randomly divided into seven groups (n = 8 per group):

Control: Group receiving normal saline (vehicle).

SCO: Group receiving scopolamine (5 mg/kg).

SCO+Don: Group receiving scopolamine (5 mg/kg) with donepezil (0.1 mg/kg).

SCO+Se: Group receiving scopolamine (5 mg/kg) with selenium nanoparticles (without chitosan coating).

SCO+F1: Group receiving scopolamine (5 mg/kg) with loaded SeNPs without chitosan coating (containing 0.1 mg/kg donepezil).

SCO+F2: Group receiving scopolamine (5 mg/kg) with loaded SeNPs with chitosan coating (containing 0.1 mg/kg donepezil).

SCO+F3: Group receiving scopolamine (5 mg/kg) with blank SeNPs chitosan coating.

Nanoparticles were administered intraperitoneally at 2 ml/kg per day for 26 d. Three weeks after the start of treatment, behavioral tests were conducted [25].

Animal study

Learning and memory test

Spatial memory test (Morris water maze, MWM)

The Morris Water Maze (MWM) test is a widely used method to evaluate spatial learning and memory in rat models. The apparatus consisted of a circular pool (136 cm diameter, 60 cm height) filled with water maintained at 25±1 °C. A hidden platform (10 cm diameter) was submerged approximately 1 cm below the water's surface in the center of one quadrant (target quadrant). The pool was located in a dimly lit room with visual cues on the walls to aid navigation [26].

Learning phase (Days 22-26)

Each rat was subjected to four trials per day for four consecutive days. The rat was placed in the pool at a random starting point and given 60 sec to locate the hidden platform. If unsuccessful, the rat was gently guided to the platform. The time (latency) and distance traveled (path length) to reach the platform were recorded using Ethovision XT software.

Probe trial (Day 27)

To evaluate spatial memory retention in rats, researchers conducted a probe trial where the platform was removed, and the rats' movements were recorded. The time spent in the target quadrant and the distance traveled within it served as indicators of the rats' ability to recall the platform's location. These metrics are valuable in assessing the rat's ability to recall the platform's location and navigate to the target quadrant effectively.

Passive avoidance test (Shuttle box)

The passive avoidance test was used to evaluate memory function in rats. The apparatus consisted of two chambers (one light, one dark) separated by a sliding door. The dark chamber's floor was equipped with a metal grid connected to a shock generator.

Habituation (Days 1-2): Rats were individually placed in the light chamber for 5 min and the time it took them to enter the dark chamber was recorded.

Acquisition (Day 3): Rats were placed in the light chamber and after 20 sec, the door was opened. The time to enter the dark chamber (initial latency, T1) was recorded. Upon entering, the door was closed and a mild foot shock (50 Hz, 1 mA, 1 second) was administered.

Retention (Day 4): Rats were again placed in the light chamber and the time to enter the dark chamber (Step-Through Latency, (STL)) was recorded (maximum 60 sec). Increased STL indicated improved memory retention [26].

Laboratory analysis

Measurement of antioxidant capacity

The ferric-reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) assay was used to assess antioxidant capacity in serum and brain tissue homogenates. The FRAP working solution consisted of acetate buffer, TPTZ solution and FeCl3.

Brain tissue was homogenized and centrifuged to obtain the supernatant.

Serum or brain supernatant (50 µl) was added to 1.5 ml of FRAP working solution and incubated at 37 °C for 10 min.

The absorbance of the resulting blue-colored complex was measured at 593 nm.

FRAP values were calculated using a standard curve generated with FeSO4 [25].

Measurement of malondialdehyde (MDA) levels

The level of MDA, a marker of lipid peroxidation, was measured in serum and brain tissue homogenates using the thiobarbituric acid reactive substances assay.

Serum or brain homogenate (1 ml) was incubated at 37 °C for 60 min.

Trichloroacetic acid (1 ml, 5%) and thiobarbituric acid (1 ml, 67%) were added and the mixture was vortexed.

The mixture was centrifuged, and the supernatant was heated in a boiling water bath for 10 min.

After cooling, the absorbance was measured at 535 nm.

MDA levels were calculated using a standard curve [27].

Measurement of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity

A modified Ellman's method measured Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity in serum and brain tissue homogenates.

Serum or brain homogenate (0.4 ml) was added to 2.6 ml phosphate buffer.

5,5'-Dithiobis-(2-Nitrobenzoic Acid) (DTNB) (100 µl) was added, and the absorbance was zeroed.

Acetylthiocholine iodide substrate (60 µl) was added, and the mixture was mixed well.

The absorbance at 412 nm was measured every 15 sec for seven readings.

The reaction rate (change in absorbance per minute) was calculated, and AChE activity was determined.

For red blood cell AChE activity, blood samples were diluted with distilled water and the assay was performed as described above using the acetylthiocholine iodide substrate [28].

Statistical analysis

After collecting the data (n = 3), it was entered into Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 18 software and analyzed using descriptive statistics (including frequency, percentage, mean and standard deviation) and analytical statistics, including one-way analysis of variance with Tukey's post hoc test. A significance level of 5% (p<0.05) was considered to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS

Characterization of nanoparticles

Morphology and size

FE-SEM analysis revealed that the SeNPs were spherical and uniformly distributed. The average nanoparticle size was approximately 200 nm (fig. 1A). DLS analysis further confirmed the size distribution, with an average size of 206 nm and a polydispersity index (PDI) of 0.231, indicating a high degree of size uniformity (fig. 1E).

Porosity

The mesoporous structure of SeNPs was confirmed by isotherm and porosity studies (fig. 1B). The surface area of the nanoparticles was determined using the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) method, which revealed a surface area of 0.091625 cm2/g (fig. 1C) and the pore radius, as calculated from the Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) method, was 1.64 nm (fig. 1D).

Zeta potential

The zeta potential of the SeNPs was measured to be-20.4 mV (fig. 1F).

Fig. 2: FTIR spectrum of SeNPs showing characteristic peaks

Fig. 1: Characterization of SeNPs: A) FE-SEM image, B) Isotherm, C) BET pattern, D) BJH curve, E) Size distribution, F) Zeta potential

FTIR analysis

Fig. 2 displays Se's FTIR data. The peak observed at 1109 cm-1 corresponds to the stretching vibration of Se-O, whereas the peaks at 1631 and 470 cm-1 correspond to the bending vibrations of Se-O. Intense bands are detected at 3437 cm-1, indicating O-H stretching vibrations, while the peak at 1393 cm-1 corresponds to C-O stretching vibrations. The vibrations detected at 2870 cm-1 and 2927 cm-1 correspond to the symmetric and asymmetric stretching vibrations of the C-H bonds.

EDAX analysis

The elemental composition of the F2 nanoparticles was evaluated using EDAX. The analysis confirmed the presence of carbon, oxygen, selenium, hydrogen and nitrogen, which are the constituent elements of selenium nanoparticles, donepezil and chitosan (fig. 3). The presence of these elements supports the successful formation of the F2 nanoparticles and the incorporation of both donepezil and chitosan into the nanoparticle structure.

Fig. 3: EDAX analysis of F2 nanoparticles confirming elemental composition

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) of nanoparticles

The thermal stability of Se, F1 and F2 nanoparticles were investigated using TGA under a nitrogen atmosphere. The samples were heated from ambient temperature to 800 °C at a constant rate. The TGA curves (fig. 4) reveal distinct weight loss patterns for each nanoparticle type.

Se: The Se nanoparticles demonstrated high thermal stability, exhibiting minimal weight loss (5.5%) even when heated up to 800 °C. This observed weight loss can be primarily attributed to the evaporation of residual solvent and adsorbed water.

F1: They showed a significant weight loss of 68.35% at 800 °C, suggesting the decomposition of the organic functional groups in donepezil.

F2: They exhibited a weight loss of 56.45% at 800 °C. This weight loss is attributed to the combined decomposition of donepezil and the chitosan coating. The slightly lower weight loss compared to F1 suggests that the chitosan layer provides additional thermal stability. The distinct weight loss patterns observed for each nanoparticle type provide valuable insights into their thermal behavior and the potential impact of the chitosan coating on their stability.

Fig. 4: TGA analysis of Se, F1 and F2 nanoparticles showing weight loss patterns

Drug loading

The successful encapsulation of donepezil within the chitosan-coated selenium nanoparticles (F2) is crucial for the efficacy of this drug delivery system. The loading efficiency of donepezil into the F2 nanoparticles was determined to be 42.3±0.57%, indicating that a substantial portion of the initial drug amount was successfully incorporated. The loading capacity, which reflects the amount of drug loaded per unit mass of nanoparticles, was 12.2±0.31%. While this value may seem moderate, it is essential to consider the potential for controlled and sustained release of donepezil from the nanoparticles, which could enhance its therapeutic efficacy. The loading efficiency and capacity values are summarized in table 1.

Table 1: Donepezil loading in F2 nanoparticles

| Nanoparticle | Loading efficiency (%) | Loading capacity (%) |

| F2 | 42.3±0.57 | 12.2±0.31 |

Value represent mean±SD (n = 3).

The successful loading of donepezil into the F2 nanoparticles, as evidenced by the reasonable loading efficiency and capacity, supports the feasibility of this drug delivery system for further investigation in the context of AD treatment. The subsequent evaluation of drug release kinetics will provide additional insights into the potential of these nanoparticles for controlled and targeted drug delivery to the brain.

Morris water maze (MWM) test

The Morris water maze (MWM) test was employed to assess the effects of SCO and F2 on spatial learning and memory in rats. The experimental timeline involved ten consecutive days of SCO administration to induce memory impairment, followed by a 5 d MWM assessment starting on the fifth day post-SCO treatment.

The results revealed that chronic SCO administration significantly impaired spatial memory, as evidenced by the increased latency (time to find the hidden platform) in the MWM test compared to the control group (p<0.05). The learning performance, assessed by both latency and path length to reach the hidden platform during the first four training days, further confirmed the cognitive deficit in the SCO group. Moreover, the probe trial on day 5, where the platform was removed, showed a marked decrease in the time spent in the target quadrant by the SCO group, further substantiating the memory impairment.

In contrast, rats treated with F2 significantly improved spatial memory and learning. They demonstrated significantly reduced latency and path length to find the platform during training, along with increased time spent in the target quadrant during the probe trial (p<0.01 compared to the SCO group). These findings suggest that F2 effectively mitigated scopolamine-induced memory impairment, highlighting their potential as a therapeutic intervention for cognitive deficits associated with AD [29-31].

Learning stage

The Morris water maze test assessed the rats' spatial learning ability over four days. The results revealed significant differences in the time it took the various groups to find the hidden platform across the training days. This variation was particularly pronounced in the SCO+Se and SCO+F2 groups (fig. 5).

As expected, scopolamine injection impaired learning, leading to an increase in the time required to locate the platform. On the first day, no significant differences were observed between the groups. However, on the second day, the SCO+Se group took significantly longer to find the platform compared to all other groups. The remaining groups were similar on day 2 (fig. 5).

The observations highlight the impact of scopolamine on spatial learning and suggest potential variations in the learning process between different treatment groups, particularly the SCO+Se group, which warrants further investigation.

Fig. 5: Impact of different treatments on spatial learning in the Morris water maze test. The graph shows each group's mean escape latency (time to find the hidden platform) across the first four training days. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM)

The impact of treatments on spatial learning

Scopolamine's detrimental effect

From the second to the fourth day of the test, the SCO group consistently swam a significantly greater distance to find the platform compared to the control group, further confirming the cognitive impairment induced by SCO.

Donepezil's partial improvement

The group treated with scopolamine and donepezil (SCO+Don) showed a gradual improvement in learning, as evidenced by their decreasing escape latency. By days 3 and 4, their performance was comparable to that of the control group. This suggests that donepezil partially mitigated the learning impairment caused by scopolamine.

Selenium's beneficial effects

The selenium-treated groups (SCO+Se, SCO+F3, SCO+F1 and SCO+F2) exhibited enhanced spatial learning compared to the SCO group, with significantly reduced escape latencies. Notably, the SCO+Se group performed better on day three than the control and SCO+Don groups.

Chitosan's potential role

The chitosan-coated nanoparticle groups (SCO+F3 and SCO+F2) showed a trend towards improved spatial memory compared to the SCO+Don group, although this difference was not statistically significant.

Synergistic effect

The SCO+F1 and SCO+F2 groups, which received selenium nanoparticles loaded with donepezil, demonstrated the most pronounced improvement in spatial learning, particularly on the third and fourth days, suggesting a potential synergistic effect between selenium and donepezil.

The impact of treatments on distance traveled

Scopolamine's detrimental effect

The SCO group consistently swam a significantly greater distance to find the platform compared to the control group from the second to the fourth day of the test, further confirming the cognitive impairment induced by SCO.

Fig. 6: Effect of different treatments on escape latency in the morris water maze test (training days 1-4). The graph illustrates each group's mean escape latency (time to find the hidden platform). Standard deviation (SD) (n=3) is represented by error bars. Significant differences are denoted by: (*) for differences with the control group (p<0.05) and (#) for differences with the SCO group (p<0.05)

Selenium and donepezil's beneficial effects

The treatment groups, including those receiving selenium (SCO+Se, SCO+F3, SCO+F1 and SCO+F2) and donepezil (SCO+Don), showed an apparent reduction in swimming distance compared to the SCO group. This reduction was statistically significant on the third and fourth days for all treated groups except for the SCO+F3 group on the third day.

Donepezil's initial advantage

On the second day, the group treated with scopolamine and donepezil (SCO+Don) demonstrated a significantly shorter swimming distance than all other treatment groups except the SCO+F1 group. This suggests that donepezil may offer an initial advantage in improving spatial navigation.

No significant differences between treatments

Apart from the observation on the second day, no significant differences in swimming distance were found between the various treatment groups on other test days.

Probe trial

The probe trial, conducted without the hidden platform, assessed spatial memory retention by measuring the time spent in the target quadrant. The SCO group exhibited a significant decrease in time spent in the target quadrant compared to the control group (p<0.05), confirming the detrimental effects of scopolamine on spatial memory. In contrast, all treatment groups demonstrated a substantial increase in time spent in the target quadrant (p<0.05), indicating improved spatial memory retention. These findings suggest that the treatments effectively mitigated scopolamine-induced memory impairment. Fig. 8 illustrates the time spent in the target quadrant during the probe trial for each group.

In addition to time spent in the target quadrant, the probe trial assessed spatial memory by measuring the distance traveled within this area. The SCO group exhibited a significant decrease in the distance traveled in the target quadrant compared to the control group (p<0.05), further underscoring the detrimental effects of scopolamine on spatial memory. Conversely, all treatment groups significantly increased the distance traveled within the target quadrant (p<0.05), indicating improved memory retention and a stronger inclination to search in the area previously associated with the platform. Fig. 9 illustrates the distance traveled in the target quadrant during the probe trial for each group.

Fig. 7: Impact of different treatments on swimming distance in the Morris water maze test (training days 1-4). The graph depicts the mean swimming distance traveled to find the hidden platform for each group. Standard deviation (SD) (n=3) is represented by error bars. Significant differences are denoted by: (#) for differences with the SCO group (p<0.05)

Fig. 8: Effect of different treatments on time spent in the target quadrant during the probe trial. The graph shows each group's mean time spent in the target quadrant (where the platform was previously located) during the probe trial. Standard deviation (SD) (n=3) is represented by error bars. Significant differences are denoted by: (#) for differences with the SCO group (p<0.05) and (a) for differences with the SCO+Don group (p<0.05)

Fig. 9: Impact of different treatments on distance traveled in the target quadrant during the probe trial. The graph illustrates the mean distance traveled within the target quadrant for each group during the probe trial. Standard deviation (SD) (n=3) is represented by error bars. Significant differences are denoted by: (#) for differences with the SCO group (p<0.05) and (a) for differences with the SCO+Don group (p<0.05)

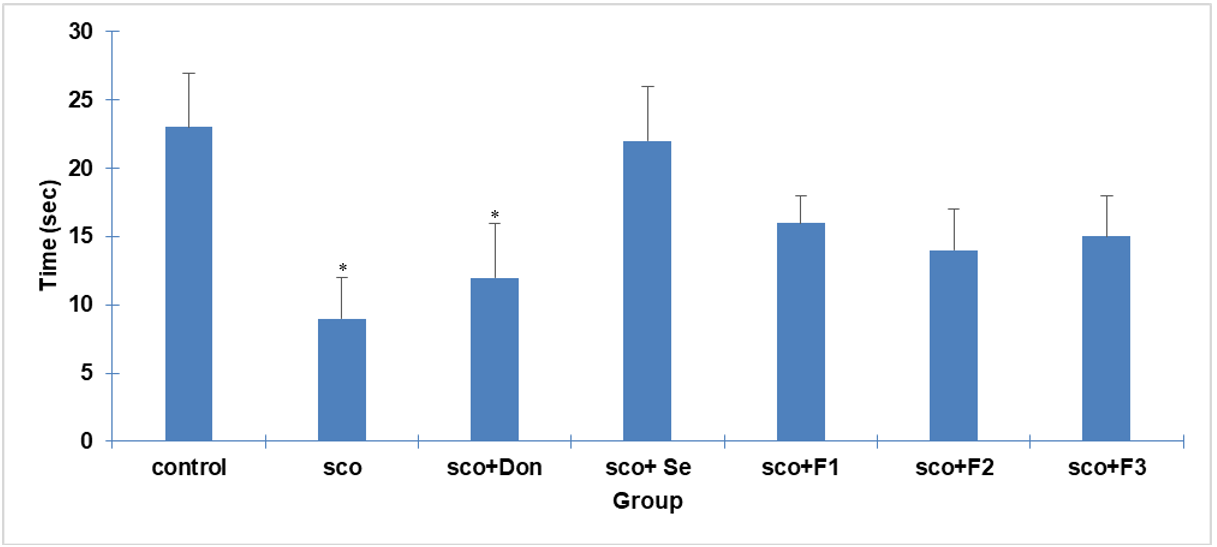

Passive avoidance test

The passive avoidance test, a fear-motivated test commonly used to assess memory function in rodents, was employed to evaluate the effects of scopolamine and F2 on memory retention. The test measures the latency of an animal to enter a dark chamber where it has previously received a mild foot shock. A longer latency to enter the dark chamber indicates improved memory retention, as the animal remembers the aversive experience.

The results showed no significant differences in initial latency (time to enter the dark chamber before the shock) between the groups during the acquisition trial. However, in the retention trial (24 h later), the SCO group exhibited a significantly reduced STL compared to the control group, indicating impaired memory retention. In contrast, all treatment groups showed a significant increase in STL compared to the SCO group, suggesting that the treatments effectively ameliorated scopolamine-induced memory deficit.

These findings further support the potential of F2 in mitigating cognitive impairment associated with AD, as they demonstrate the ability to improve both spatial memory (MWM test) and associative memory (passive avoidance test). The observed increase in STL in the treated groups suggests that these interventions enhance memory consolidation and retrieval processes, which are crucial for cognitive function.

Fig. 10: Effect of different treatments on step-through latency in the passive avoidance test (acquisition and retention trials). The graph compares the mean STL, or the time to enter the dark chamber, between the groups in the acquisition and retention trials. Data are mean+SD (n=3). # p<0.05 vs. SCO

Measurement of antioxidant capacity

Serum FRAP levels

The serum FRAP levels showed a significant decrease in the SCO group (313.6±15.14) compared to the control group (409.4±18.65), indicating reduced antioxidant capacity due to scopolamine-induced oxidative stress. While the SCO+Don, SCO+Se and SCO+F3 groups also exhibited decreased FRAP levels compared to the control, treatment with F1 (439±2.80) and F2 (466±9.15) nanoparticles led to a significant increase in FRAP levels, surpassing even the control group (p<0.05). Importantly, all treatment groups showed a significant increase in FRAP levels compared to the SCO group (p<0.05), suggesting their antioxidant potential in mitigating scopolamine-induced oxidative stress (fig. 11A).

Brain tissue FRAP levels

In contrast to the significant decrease in brain tissue FRAP levels observed in the SCO and SCO+Se groups, the SCO+F2 group showed a significant increase compared to the control (p<0.05). Furthermore, the SCO+Don, SCO+F3 and SCO+F1 groups also demonstrated higher FRAP levels than the SCO group (p<0.05) (fig. 11B).

Measurement of oxidative stress and cholinesterase activity

Malondialdehyde (MDA) levels

Serum

The mean serum MDA level, a marker of lipid peroxidation, was significantly elevated in the SCO group (17.63±0.8) compared to all other groups (p<0.05), indicating increased oxidative stress. Treatment with F1 and F2 nanoparticles significantly decreased serum MDA levels compared to both the control group (11.32±0.36) and the SCO group (p<0.05). The other treatment groups (SCO+Don, SCO+Se and SCO+F3) also showed a significant reduction in serum MDA levels compared to the SCO group (p<0.05) (fig. 11C).

Brain tissue

The brain tissue MDA levels followed a similar pattern, with a significant increase observed in the SCO group (5.70±0.17) compared to the control group (3.70±0.43) (p<0.05). All treatment groups exhibited a significant decrease in brain tissue MDA levels compared to the SCO group (p<0.05) (fig. 11D).

Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity

Serum

Serum AChE activity was significantly decreased in the SCO (27.96±0.76), SCO+Se (29.37±3.15) and SCO+F3 (29.77±2.25) groups compared to the control group (34.90±1.61) (p<0.05). However, the SCO+F2 group showed a significant increase in serum AChE activity compared to the SCO group (p<0.05) (fig. 11E).

Brain tissue

Brain tissue AChE activity showed a statistically significant difference between the SCO (13.71±0.43), SCO+Se (14.14±0.31), SCO+F2 (17.23±0.54) and control groups (16.02±0.47) (p<0.05). The SCO+Don (11.15±0.43), SCO+F3 (15.05±0.44) and SCO+F2 groups exhibited increased AChE activity, with a significant difference observed between these groups and the SCO group (p<0.05) (fig. 11F).

Fig. 11: Effects of different treatments on oxidative stress markers and acetylcholinesterase activity. The graphs compare the mean levels of A) serum FRAP, B) brain tissue FRAP, C) serum MDA, D) brain tissue MDA, E) serum AChE activity and F) brain tissue AChE activity between the groups. Standard deviation (SD) (n=3) is represented by error bars. Significant differences are denoted by: (*) for differences with the control group (p<0.05) and (#) for differences with the SCO group (p<0.05)

DISCUSSION

Alzheimer's disease (AD), a leading cause of neurodegenerative decline globally, is characterized by the accumulation of β-amyloid plaques and the subsequent elevation in oxidative stress. The present study investigates the therapeutic potential of chitosan-coated selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) loaded with donepezil (F2), a novel approach aimed at addressing both the oxidative damage and cholinergic deficits that are hallmarks of AD. Our findings demonstrate that F2 bolster antioxidant defenses and enhance cholinergic function. This dual action positions F2 as a promising therapeutic strategy that could modify disease progression by directly delivering a combination of antioxidant and cholinergic-modulating agents to the affected brain regions.

Scopolamine, a non-selective muscarinic acetylcholine receptor antagonist, is widely used to induce memory impairment and amnesia in animal models, mimicking certain aspects of AD [32]. The current study employed scopolamine to investigate the effects of chitosan-coated SeNPs containing donepezil on memory and learning deficits in male rats. The investigation was driven by the well-documented antioxidant properties of SeNPs and their potential to counteract the oxidative stress associated with scopolamine-induced cognitive impairment.

The use of scopolamine to induce amnesia in rodents serves as a well-established pharmacological model for AD, facilitating the investigation of potential therapeutic interventions. Consistent with previous studies, the current research demonstrated that intraperitoneal administration of scopolamine resulted in cognitive deficits in rats. These deficits were evident in the prolonged search time for the hidden platform in the Morris water maze and the reduced latency time in the passive avoidance test, which are widely used to assess animal cognitive function [33, 34].

The administration of SeNPs effectively mitigated these scopolamine-induced cognitive impairments. Rats treated with SeNPs exhibited improved performance in both the Morris water maze and passive avoidance tests, demonstrating enhanced learning and memory. These findings align with previous research by Balaban et al. (2017), who reported that selenium can prevent cognitive deficits in scopolamine-treated animals [35]. Furthermore, Samad et al. (2021) showed that co-administration of selenium can inhibit arsenic-induced reduction of spatial memory [36]. The present study extends these findings by demonstrating the efficacy of SeNPs, specifically chitosan-coated selenium nanoparticles loaded with donepezil, in ameliorating scopolamine-induced memory impairment. The observed improvements in cognitive function suggest the potential of F2 as a therapeutic strategy for addressing cognitive deficits associated with AD.

Selenium (Se) is an essential trace element that plays a crucial role in human health, particularly as a structural component of antioxidant enzymes involved in peroxide decomposition [37, 38]. Selenium deficiency or excessive intake can lead to various health issues, including cardiovascular and inflammatory diseases, immunodeficiency and brain disorders [39]. Selenium treatment has been shown to reduce memory deficit risk in animal models and patients with [40]. The growing interest in understanding the function of selenium and selenoproteins in neurodegenerative disorders like AD has led to extensive research in this area.

Despite extensive investigation, the exact molecular pathways underlying the initiation of AD remain elusive. Several hypotheses have been proposed, including the aggregation of amyloid precursor protein leading to the formation of Aβ plaques, excessive phosphorylation of tau protein, alterations in cholinergic neurotransmission and oxidative stress [13].

Reducing brain ROS is critical in AD treatment. As a component of antioxidant enzymes, selenium actively contributes to ROS inhibition. Our data analysis revealed that the Alzheimer's model exhibited decreased FRAP levels and increased lipid peroxidation (measured by MDA) in both serum and brain tissue. Treatment with Se, however, effectively reversed these effects. The long-term administration of selenium enhanced memory recall and reduced oxidative damage caused by scopolamine. Both SeNPs and SeNPs combined with chitosan significantly increased FRAP activity and decreased MDA levels in both blood and brain. These findings align with previous research demonstrating the potent antioxidant properties of selenoproteins and selenium nanoparticles, effectively decreasing neurogenic damage in individuals with AD and in animal models [40-42].

Se-based nanoparticles (SeNPs) offer several advantages over organic and inorganic selenium compounds, including reduced toxicity and enhanced biocompatibility. These properties have attracted significant attention from the scientific community regarding their potential as therapeutic agents. Studies have shown that nanoparticles containing selenium and selenite can effectively reduce oxidative stress and inhibit its associated cytotoxicity [23]. The ability of SeNPs to inhibit Aβ aggregation, a key pathological hallmark of AD, has also been demonstrated. For instance, epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG)-stabilized SeNPs and sialic acid-modified SeNPs coated with a blood-brain barrier permeable peptide-B6 have been shown to prevent Aβ aggregation effectively [43, 44].

Furthermore, Wang et al. reported that selenium-containing clioquinol derivatives exhibit beneficial effects on Cu2+-induced Aβ aggregation, hydrogen peroxide scavenging and intracellular ROS production in a neuroblastoma cell line [45]. Building on previous studies showing the capacity of selenium species to inhibit metal-induced Aβ aggregation, our findings highlight the therapeutic potential of SeNPs in AD. Specifically, the protective effects of chondroitin sulfate nano-selenium in AD mouse models were remarkable, demonstrating the ability to mitigate oxidative stress, enhance cognitive function and regulate cholinesterase activity [41].

The antioxidant properties of SeNPs have been further enhanced by stabilizing them with chitosan or with both chitosan and chlorogenic acid polyphenol. These modified SeNPs have demonstrated not only high antioxidant activity and the ability to inhibit metal-induced Aβ aggregation [36]. Selenium's ability to combat key pathological processes in AD, such as Aβ-induced neurotoxicity, oxidative stress and tau protein dysregulation, highlights its significant promise for the development of novel Se-containing therapeutics.

The central cholinergic neuronal system plays a critical role in learning and memory. Its impairment, characterized by decreased acetylcholine levels and receptor density, is a hallmark of pathological aging and AD [46]. Selenium-based compounds, like ebselen and diselenides, have exhibited anticholinesterase properties and antioxidant activity [47]. Our study demonstrated that Se treatment effectively reduced the elevated levels of cholinesterase induced by scopolamine. This reduction in cholinesterase activity, which is known to impair memory function, suggests a potential mechanism through which Se exerts its beneficial effects on the cholinergic system and, consequently, memory.

Furthermore, the deterioration of the cholinergic system can trigger the production of Aβ plaques, which, in turn, can lead to mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress [48]. The antioxidant properties of SeNPs, coupled with the presence of donepezil, a cholinesterase inhibitor, may contribute to the observed neuroprotective effects by suppressing neuronal death and Aβ accumulation.

Studies have demonstrated the protective effects of selenium compounds against Aβ-induced neurotoxicity in hippocampal neurons [44]. The accumulation of Aβ in the brain is directly correlated with oxidative stress [49] and Nazıroğlu et al. showed that SeNPs could effectively decrease ROS production, thereby reducing Aβ formation [15]. Oxidative stress also plays a role in neuronal cell death in AD and antioxidants can interfere with pathways leading to Aβ accumulation[50]. Therefore, it is plausible that the antioxidant properties of SeNPs, in conjunction with the presence of donepezil, contribute to the observed neuroprotection by suppressing neuronal death and Aβ buildup.

The neuroprotective effects of F2 likely stem from their dual action: reducing oxidative stress and enhancing cholinergic signaling, both crucial factors in AD pathophysiology. This proposed mechanism is further supported by studies where donepezil-loaded mesoporous silica nanoparticles significantly improved memory retention in rats. These findings collectively suggest that enhanced drug delivery to the brain and subsequent modulation of cognitive pathways play a key role in the therapeutic efficacy of such nanoparticle-based approaches [26].

The literature on the impact of selenium and SeNPs on disease treatment presents some conflicting findings. These discrepancies may be attributed to variations in experimental conditions, such as selenium concentrations, cell lines used and the specific selenium compounds administered [15].

The current study's findings align with previous research, demonstrating that SeNPs enhance cognitive function memory and reduce oxidative stress in neurodegenerative disorders. Our results indicate that combining donepezil with Se, particularly in the form of F2, is more effective than donepezil alone in improving cognitive function, enzyme activity, lipid peroxidation and FRAP levels. The lack of statistical significance in some comparisons might be attributed to the specific concentrations and nanoscale dimensions of the SeNPs used.

Overall, our work supports the notion that Se exhibits neuroprotective effects and shows promise as a treatment option for neuropathological disorders like AD. The development of F2 represents a step towards harnessing the therapeutic potential of selenium for combating the complex pathophysiology of AD.

CONCLUSION

The present study demonstrates that chitosan-coated selenium nanoparticles loaded with donepezil can effectively ameliorate scopolamine-induced memory and learning impairments in male rats. The improvements in cognitive function were associated with modulation of brain acetylcholinesterase activity, reduced lipid peroxidation and enhanced brain antioxidant levels. These findings suggest that the synergistic effects of selenium and donepezil, delivered via a targeted nanoparticle system, offer a promising therapeutic strategy for addressing the cognitive deficits and oxidative stress associated with AD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This article is the outcome of Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences project 5310. The authors express their gratitude to the Vice Chancellor for Research and Technology at Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences for providing financial support for their research. The authors also extend their appreciation to the Phytochemical Laboratory staff at the Research Center for Medicinal Plants for their valuable assistance. The study was primarily funded by grant number 5310 from the Vice Chancellor for Research and Technology of Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed equally to the conception, execution and writing of this study and all approved the final manuscript. Fariba Houshmand and Alaa A. Hashim focused on study design and, nanoparticle synthesis and manuscript preparation, respectively. Hussein Abdelamir Mohammad and Fatemeh Driss assisted with animal experiments and data interpretation. Fatemeh Iranpour and Reza Ahmadi participated in experimental design and biochemical assays. Narges Najafi contributed to animal handling, while Dhiya Altememy aided in nanoparticle characterization. Pegah Khosravian oversaw the project and led manuscript preparation.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

Johnson DK, Storandt M, Morris JC, Langford ZD, Galvin JE. Cognitive profiles in dementia: alzheimer disease vs healthy brain aging. Neurology. 2008;71(22):1783-9. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000335972.35970.70, PMID 19029518.

Nasb M, Tao W, Chen N. Alzheimers disease puzzle: delving into pathogenesis hypotheses. Aging Dis. 2024;15(1):43-73. doi: 10.14336/AD.2023.0608, PMID 37450931.

Passeri E, Elkhoury K, Morsink M, Broersen K, Linder M, Tamayol A. Alzheimers disease: treatment strategies and their limitations. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(22):13954. doi: 10.3390/ijms232213954, PMID 36430432.

Benilova I, DE Strooper B. Neuroscience promiscuous alzheimers amyloid: yet another partner. Science. 2013;341(6152):1354-5. doi: 10.1126/science.1244166, PMID 24052299.

Koc ER, Ilhan A, Ayturk Z, Acar B, Gurler M, Altuntas A. A comparison of hair and serum trace elements in patients with alzheimer disease and healthy participants. Turk J Med Sci. 2015;45(5):1034-9. doi: 10.3906/sag-1407-67, PMID 26738344.

Rayman MP. The importance of selenium to human health. Lancet. 2000;356(9225):233-41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02490-9, PMID 10963212.

Cardoso BR, Roberts BR, Bush AI, Hare DJ. Selenium selenoproteins and neurod generative diseases. Metallomics. 2015;7(8):1213-28. doi: 10.1039/c5mt00075k, PMID 25996565.

Fibiger HC. Cholinergic mechanisms in learning memory and dementia: a review of recent evidence. Trends Neurosci. 1991;14(6):220-3. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(91)90117-d, PMID 1716012.

Hampel H, Mesulam MM, Cuello AC, Khachaturian AS, Vergallo A, Farlow MR. Revisiting the cholinergic hypothesis in alzheimers disease: emerging evidence from translational and clinical research. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2019;6(1):2-15. doi: 10.14283/jpad.2018.43, PMID 30569080.

Blake MG, Krawczyk MDC, Baratti CM, Boccia MM. Neuropharmacology of memory consolidation and reconsolidation: insights on central cholinergic mechanisms. J Physiol Paris. 2014;108(4-6):286-91. doi: 10.1016/j.jphysparis.2014.04.005, PMID 24819880.

Maurer SV, Williams CL. The cholinergic system modulates memory and hippocampal plasticity via its interactions with non-neuronal cells. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1489. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01489, PMID 29167670.

Marucci G, Buccioni M, Dal Ben DD, Lambertucci C, Volpini R, Amenta F. Efficacy of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in alzheimers disease. Neuropharmacology. 2021;190:108352. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2020.108352, PMID 33035532.

Jawaid T, Rai A, Kamal M. A comparative study of neuroprotective effect of telmisartan and donepezil against lipopolysaccharide induced neuroinflammation in mice. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2015;8(6):68-72.

Ionescu Tucker A, Cotman CW. Emerging roles of oxidative stress in brain aging and alzheimers disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2021;107:86-95. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2021.07.014, PMID 34416493.

Nazıroglu M, Muhamad S, Pecze L. Nanoparticles as potential clinical therapeutic agents in alzheimers disease: focus on selenium nanoparticles. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2017;10(7):773-82. doi: 10.1080/17512433.2017.1324781, PMID 28463572.

Yamasaki M, Takeuchi T. Locus coeruleus and dopamine-dependent memory consolidation. Neural Plast. 2017;2017(1):8602690. doi: 10.1155/2017/8602690, PMID 29123927.

Rita Cardoso B, Silva Bandeira V, Jacob Filho W, Franciscato Cozzolino SM. Selenium status in elderly: relation to cognitive decline. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2014;28(4):422-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2014.08.009, PMID 25220532.

Mohammad Jafari R, Ala M, Goodarzi N, Dehpour AR. Does pharmacodynamics of drugs change after presenting them as nanoparticles like their pharmacokinetics? Curr Drug Targets. 2020;21(8):807-18. doi: 10.2174/1389450121666200128113547, PMID 32003669.

Skalickova S, Milosavljevic V, Cihalova K, Horky P, Richtera L, Adam V. Selenium nanoparticles as a nutritional supplement. Nutrition. 2017 Jan;33:83-90. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2016.05.001, PMID 27356860.

Merten T, Henry M. Symptom and performance validity assessment in older adults and patients with dementia and claimed dementia. A handbook of geriatric neuropsychology. Routledge; 2022. p. 286-303.

Kaboli MA, Hashim AA, Altememy D, Saffari chaleshtori JS, Rezaee M, Hosseini SA. Silk fibroin-coated mesoporous silica nanoparticles enhance 6-thioguanine delivery and cytotoxicity in breast cancer cells. Int J App Pharm. 2025;17(1):275-83. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2025v17i1.52882.

Gao X, Lowry GV. Progress towards standardized and validated characterizations for measuring physicochemical properties of manufactured nanomaterials relevant to nano health and safety risks. Nano Impact. 2018;9:14-30. doi: 10.1016/j.impact.2017.09.002.

Cao Y, Zhang R. The application of nanotechnology in treatment of alzheimers disease. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2022;10:1042986. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2022.1042986, PMID 36466349.

Singh B, Day CM, Abdella S, Garg S. Alzheimers disease current therapies novel drug delivery systems and future directions for better disease management. J Control Release. 2024;367:402-24. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2024.01.047, PMID 38286338.

Rahnama S, Rabiei Z, Alibabaei Z, Mokhtari S, Rafieian Kopaei M, Deris F. Anti-amnesic activity of Citrus aurantium flowers extract against scopolamine-induced memory impairments in rats. Neurol Sci. 2015;36(4):553-60. doi: 10.1007/s10072-014-1991-2, PMID 25367404.

Cınar E, Mutluay SU, Baysal I, Gultekinoglu M, Ulubayram K, Ciftci SY. Donepezil-loaded PLGA-b-PEG nanoparticles enhance the learning and memory function of beta-amyloid rat model of alzheimers disease. Noro Psikiyatr Ars. 2022;59(4):281-9. doi: 10.29399/npa.28275, PMID 36514517.

Fathi F, Oryan S, Rafieian KopaeI M, Eidi A. Neuroprotective effect of pretreatment with Mentha longifolia L. extract on brain ischemia in the rat stroke model. Arch Biol Sci (Beogr). 2015;67(4):1151-63. doi: 10.2298/ABS150115091F.

George PM, Abernethy MH. Improved ellman procedure for erythrocyte cholinesterase. Clin Chem. 1983;29(2):365-8. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/29.2.365, PMID 6821947.

Morris R. Developments of a water maze procedure for studying spatial learning in the rat. J Neurosci Methods. 1984;11(1):47-60. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(84)90007-4, PMID 6471907.

Uddin MS, Kabir MT, Niaz K, Jeandet P, Clement C, Mathew B. Molecular insight into the therapeutic promise of flavonoids against alzheimers disease. Molecules. 2020;25(6):1267. doi: 10.3390/molecules25061267, PMID 32168835.

Vorhees CV, Williams MT. Morris water maze: procedures for assessing spatial and related forms of learning and memory. Nat Protoc. 2006;1(2):848-58. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.116, PMID 17406317.

Bajo R, Pusil S, Lopez ME, Canuet L, Pereda E, Osipova D. Scopolamine effects on functional brain connectivity: a pharmacological model of alzheimers disease. Sci Rep. 2015;5(1):9748. doi: 10.1038/srep09748, PMID 26130273.

Jung HA, Jin SE, Choi RJ, Kim DH, Kim YS, Ryu JH. Anti-amnesic activity of neferine with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory capacities as well as inhibition of ChEs and BACE1. Life Sci. 2010;87(13-14):420-30. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2010.08.005, PMID 20736023.

Xiao J, LI S, Sui Y, WU Q, LI X, Xie B. Lactobacillus casei-01 facilitates the ameliorative effects of proanthocyanidins extracted from lotus seedpod on learning and memory impairment in scopolamine induced amnesia mice. PLOS One. 2014;9(11):e112773. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112773, PMID 25396737.

Balaban H, Nazıroglu M, Demirci K, Ovey IS. The protective role of selenium on scopolamine-induced memory impairment oxidative stress and apoptosis in aged rats: the involvement of TRPM2 and TRPV1 channels. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54(4):2852-68. doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-9835-0, PMID 27021021.

Samad N, Rao T, Rehman MH, Bhatti SA, Imran I. Inhibitory effects of selenium on arsenic-induced anxiety-/depression like behavior and memory impairment. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2022;200(2):689-98. doi: 10.1007/s12011-021-02679-1.

Godoi GL, DE Oliveira Porciuncula L, Schulz JF, Kaufmann FN, DA Rocha JB, DE Souza DO. Selenium compounds prevent amyloid β-peptide neurotoxicity in rat primary hippocampal neurons. Neurochem Res. 2013;38(11):2359-63. doi: 10.1007/s11064-013-1147-4, PMID 24013888.

Kaur K, Kaur R, Kaur M. Recent advances in alzheimers disease: causes and treatment. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2016;8(2):8-15.

Ferro C, Florindo HF, Santos HA. Selenium nanoparticles for biomedical applications: from development and characterization to therapeutics. Adv Healthc Mater. 2021;10(16):e2100598. doi: 10.1002/adhm.202100598, PMID 34121366.

Pinton S, DA Rocha JT, Zeni G, Nogueira CW. Organoselenium improves memory decline in mice: involvement of acetylcholinesterase activity. Neurosci Lett. 2010;472(1):56-60. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.01.057, PMID 20122991.

JI D, WU X, LI D, Liu P, Zhang S, Gao D. Protective effects of chondroitin sulphate nano selenium on a mouse model of alzheimers disease. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;154:233-45. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.03.079, PMID 32171837.

Bashir DW, Rashad MM, Ahmed YH, Drweesh EA, Elzahany EA, Abou El-Sherbini KS. The ameliorative effect of nanoselenium on histopathological and biochemical alterations induced by melamine toxicity on the brain of adult male albino rats. Neurotoxicology. 2021 Sep;86:37-51. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2021.06.006, PMID 34216684.

Zhang J, Zhou X, YU Q, Yang L, Sun D, Zhou Y. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG)-stabilized selenium nanoparticles coated with Tet-1 peptide to reduce amyloid-β aggregation and cytotoxicity. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2014;6(11):8475-87. doi: 10.1021/am501341u, PMID 24758520.

Yin T, Yang L, Liu Y, Zhou X, Sun J, Liu J. Sialic acid (SA) modified selenium nanoparticles coated with a high blood brain barrier permeability peptide-B6 peptide for potential use in alzheimers disease. Acta Biomater. 2015 Oct;25:172-83. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2015.06.035, PMID 26143603.

Wang Z, Wang Y, LI W, Mao F, Sun Y, Huang L. Design synthesis and evaluation of multitarget directed selenium-containing clioquinol derivatives for the treatment of alzheimers disease. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2014;5(10):952-62. doi: 10.1021/cn500119g, PMID 25121395.

Douchamps V, Mathis C. A second wind for the cholinergic system in alzheimers therapy. Behav Pharmacol. 2017;28(2-3):112-23. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0000000000000300, PMID 28240674.

Barbosa FA, Canto RF, Teixeira KF, DE Souza AS, DE Oliveira AS, Braga AL. Selenium derivative compounds: a review of new perspectives in the treatment of alzheimers disease. Curr Med Chem. 2023;30(6):689-700. doi: 10.2174/0929867329666220224161454, PMID 35209817.

Leuner K, Muller WE, Reichert AS. From mitochondrial dysfunction to amyloid beta formation: novel insights into the pathogenesis of alzheimers disease. Mol Neurobiol. 2012;46(1):186-93. doi: 10.1007/s12035-012-8307-4, PMID 22833458.

Demirci K, Nazıroglu M, Ovey IS, Balaban H. Selenium attenuates apoptosis inflammation and oxidative stress in the blood and brain of aged rats with scopolamine-induced dementia. Metab Brain Dis. 2017;32(2):321-9. doi: 10.1007/s11011-016-9903-1, PMID 27631101.

Tonnies E, Trushina E. Oxidative stress synaptic dysfunction and alzheimers disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;57(4):1105-21. doi: 10.3233/JAD-161088, PMID 28059794.