Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 2, 2025, 153-164Original Article

EXPANSION STRATEGIES TO DESIGN HYBRID MOLECULES OF FDA APPROVED DRUGS AS POTENTIAL INHIBITORS OF SARS Co-V-2 MAIN PROTEASE (Mpro)

THEJUS VARGHESE THOMAS*, AMRITA THAKUR, ANIL KUMAR S.*

Department of Physical Sciences, Amrita School of Engineering, Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham, Bengaluru Campus, India

*Corresponding author: Thejus Varghese Thomas; *Email: s_anilkumar@blr.amrita.edu

Received: 06 Nov 2024, Revised and Accepted: 27 Dec 2024

ABSTRACT

Objective: This research was conducted to design hybrid molecules of FDA-approved drugs as potential inhibitors of SARS Co-V-2 (Mpro) using computational approach.

Methods: This work focused on the significance of hybrid molecules or Mutual Pro-drugs. We have designed a set of 20 molecules and applied Molecular Docking, and Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion, Toxicity (ADMET) tests to filter them. The most effective molecule was then studied for its stability using Molecular Dynamic (MD) simulations.

Results: We have found that the molecule PH-6a has a very low binding energy of-7.58kcal/mol and it forms five hydrogen bonds (Met49, Phe140, His163, and Glu166) and a pi bond (Cys145) with the crucial residues of the targeted Mpro protein. It possesses lower toxicity, is impermeable to the blood-brain barrier (BBB), and has favourable synthetic availability and drug scores. The Root mean Square Deviation (RMSD) of the lead compound (PH-6a) was within the acceptable range of 3 Å and the total energy of the compound PH-6a was determined to be-5.06 kcal/mol, indicating a higher level of stability in the structure.

Conclusion: Our findings offer valuable insights into the significance of hybrid molecules and their potential application in the development of design strategies for addressing various emergency viral infections. Additionally, our results contribute to the creation of a library of compounds with potential therapeutic properties.

Keywords: SARS Co-V-2, Main protease (Mpro), Hybrid molecules, Penciclovir, Hydroxychloroquine, ADMET, Molecular docking, Molecular dynamics

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i2.53121 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Prior to 2002, the human coronaviruses, HCoV-229E, HKU1 [1] etc. were recognized for causing subtle indications resembling the upper respiratory infection in persons with a healthy immune system [2]. During the last twenty years, three new coronaviruses that can be transmitted from animals to humans have emerged. These are the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-Co-V) in 2002, the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-Co-V) in 2012, and the SARS coronavirus-2 (SARS-Co-V-2) in 2019. These viruses have attracted worldwide attention because they have the potential to cause epidemics and high mortality. Projected climate changes indicate a worsening trend in extreme weather events, which subsequently heightens the probability of future viral outbreaks that pose substantial risks to civilization. Global urbanization significantly contributes to the development and transmission of viral diseases, primarily due to overcrowding and unhealthy circumstances [3]. Treatment options for viral infections are reportedly limited. Further, recent press reports have raised concerns about the Covishield vaccination, citing serious side effects like TTS(Thrombosis with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome), despite vaccine's efficacy against the virus [4].

The non-structural proteins (NSPs) of SARS-CoV-2, including Mpro, Papain-like protease (PLpr), RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), and RNA helicase, play crucial roles in proofreading, cleaving polyproteins, and facilitating replication [5–13]. Targeting these proteins to inhibit early viral replication may help avert the progression of the disease into a hyper-inflammatory phase, which has led to significant research into their potential as therapeutic targets. Mpr is highly conserved among SARS viruses and possesses unique cleavage site specificity. These attributes suggest that developing inhibitors targeting Mpro would be an effective drug development strategy. However, SARS viruses have reportedly acquired resistance towards many FDA-approved Mpro inhibitors such as Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), Penciclovir, Remdesivir, Lopinavir, Ritonavir, Ribavirin, Favipiravir, Tenofovir, and Retonavir [14–18]. The ongoing need for novel drugs persists due to evolving variants, diverse patient responses, potential antiviral resistance, side effects of vaccines and unaddressed long-term effects of COVID-19 [19].

Designing hybrid molecules, also known as mutual prodrugs, is a pharmacological approach in which two drugs are chemically linked together, allowing each active component to improve the effectiveness of the other. The selected active component may possess the same biological function as the original medicine but with a reduced toxicity profile, resulting in a synergistic effect, or it may have a unique biological activity that is not present in the parent compound, so providing an extra therapeutic benefit [20, 21]. Numerous mutual prodrugs based on 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) have been developed and are presently available as licensed medications with the goal of enhancing therapeutic efficacy and reducing toxicity [22].

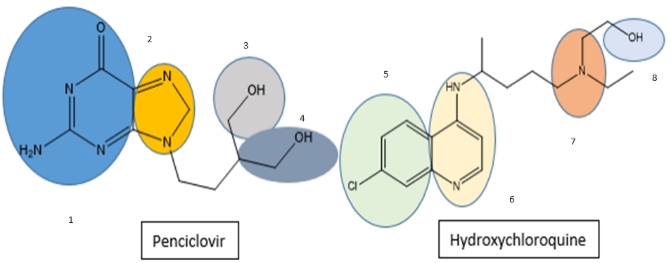

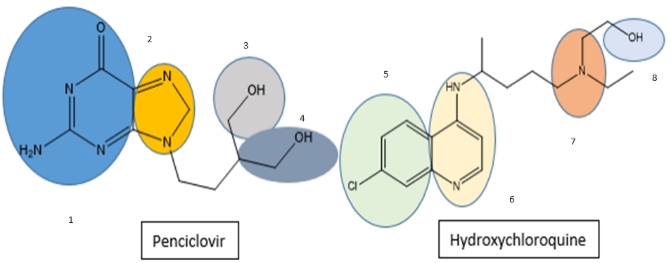

Penciclovir and HCQ are prototypical examples of SARS inhibitors, each representing a distinct class of drugs. Both in vitro and in vivo tests demonstrate that compounds Penciclovir and HCQ exhibit strong potential as therapeutic candidates for combating SARS-CoV-2 [23, 24]. Thus, we selected these two inhibitors as the primary subjects of our investigation. Penciclovir possesses a molecular configuration that incorporates a heterocyclic ring referred to as a purine ring. Its presence is crucial for its antiviral efficacy against the herpes virus as it reduces the action of viral DNA polymerase [25]. Purine, along with its derivative nucleobases adenine and guanine, are widely present in biological chemistry. Numerous purine derivatives have been synthesized as antiviral [26], autoimmune disease [27], and anticancer [28] drugs. HCQ possesses a chemical structure that comprises a quinoline ring system. Quinoline and its derivatives belong to a notable category of potent heterocyclic compounds that possess a wide range of pharmacological activities [29], including antibacterial [30], antimalarial [31], and anti-viral effects [32]. HCQ was one of the drugs that were said to have shown in vitro efficacy against the SARS-CoV-2 virus in the early phases of the global pandemic. However, comprehensive evaluations of HCQ's effectiveness in treating SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans have not yielded satisfactory outcomes [33]. Furthermore, it has been discovered that augmenting pyrimidines with supplementary building blocks, such as hydrazide-hydrazone (CO–NHN=C system), increases their bioactivity. For example, several derivatives containing the hydrazide-hydrazone structure have demonstrated a diverse array of notable biological features, including anti-malarial, anti-tuberculosis, anti-HIV, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and antiviral effects [34].

The rationale for choosing particular fragments such as purines, quinolone rings, amides, and aryl groups in the design of inhibitors for SARS-CoV-2 Mpro is based on their capacity to improve binding affinity and stability through various mechanisms, including hydrogen bonding, aromatic stacking, hydrophobic interactions, and steric complementarity [35]. The synergistic amalgamation of these fragments enables the development of powerful inhibitors with exceptional selectivity and robust affinity to the protease, rendering them efficacious therapeutic agents against SARS-CoV-2.

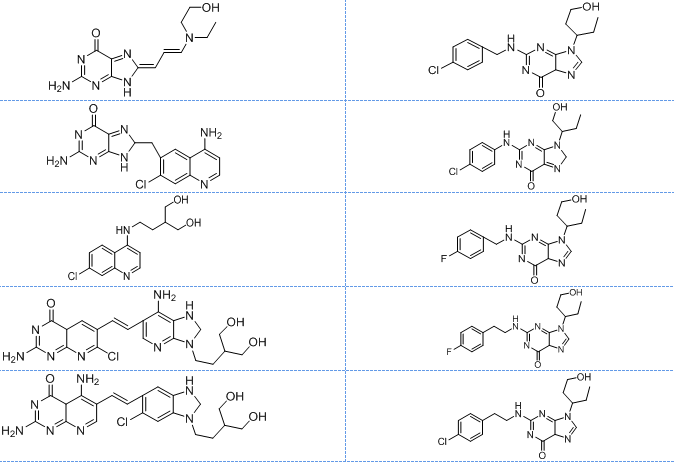

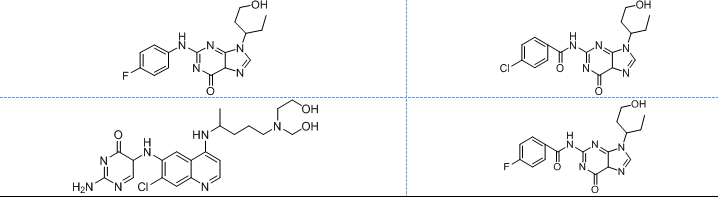

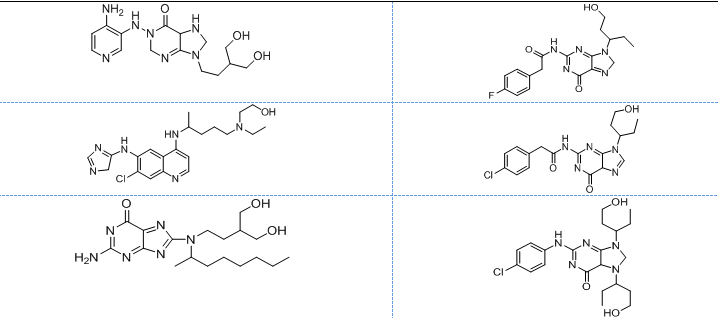

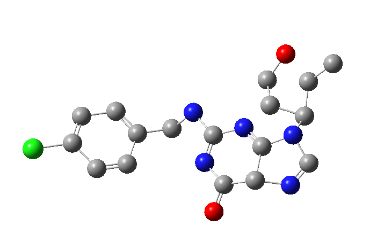

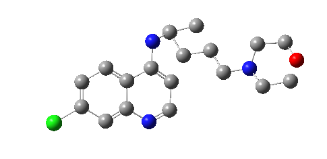

In this study, we chose eight segments (fig. 1) from these two compounds and assumed that the energy of covalent bonds created by moieties of the same kind is the same. The selection of pharmacophore moieties and the type of linker has been made after giving considerable thought to the mechanism of action. Subsequently, various combinations of fragments were devised, leading to the creation of ten novel core molecules. The ‘top hit’ structure was further refined by using chemical intuition leading to ten analogues of the lead molecule. The compounds exhibiting superior theoretical activity were then chosen through the utilization of molecular docking, ADMET filtration, and molecular dynamics simulations.

Fig. 1: Fragments selected from hydroxychloroquine and penciclovir

To summarize, an effective noncovalent inhibitor of Mpro generally contains four essential components: (i) a hydrophobic aromatic sub-moiety located in the S2 site; (ii) and (iii) H-bonding interactions with the pendant group of the His163 residue (via an acceptor) and Glu166 (also by means of an acceptor); and (iv) an aryl system placed at the S1 cavity. These observations are consistent with earlier research on the structural development of inhibitors for SARS-CoV-2 Mpro and the experimental findings from the COVID Moonshot initiative [36–38].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Retrieval of protein structure

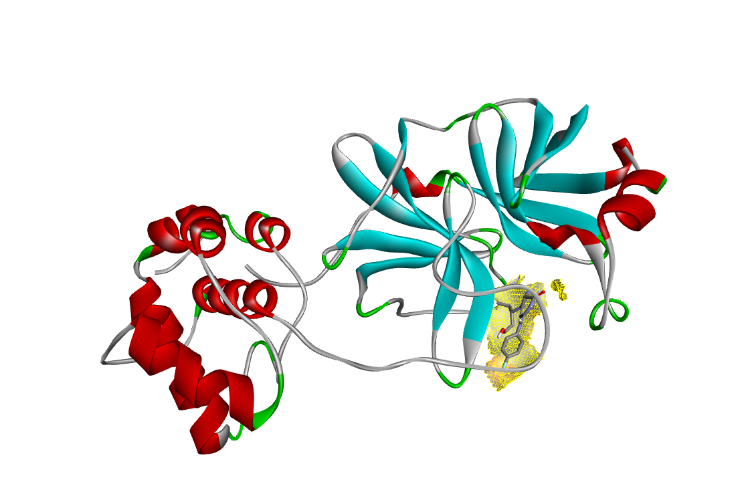

PDB database (www. rcsb. org) was accessed to obtain the crystal structure of the Mpro enzyme of SARS-CoV-2 in PDB format (PDB ID: 6LU7) [39].

Preparation of potential inhibitors

The structures of the selected FDA drugs HCQ (ID: CHEMBL1535) and Penciclovir (ID: CHEMBL1540) were obtained from the ChEMBL database, (www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl) for this investigation. We selected eight segments from these two drugs and structured them to interconnect in various combinations using ChemDraw3D. Hybrid molecule design employs a comprehensive strategy that combines structural biology, medicinal chemistry, and pharmacology focusing on SARS-CoV-2 Mpro [40, 41].

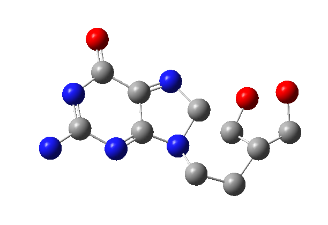

Penciclovir, an analogue of guanosine, possesses antiviral and protein-binding characteristics due to its molecular fragments. Because the guanine resembles normal guanosine, the viral polymerase tends to incorporate it in DNA synthesis. This integration prematurely stops DNA synthesis and limits viral multiplication. The necessary structural features for drug action, in this case, include the hydroxymethyl group, which activates into its triphosphate form in infected cells, and the ability of guanine's aromatic purine ring to form hydrogen bonds with the active site of viral DNA polymerase. In some of its analogues, the hydroxyl groups, in the ribose-like structure form hydrogen bonds with amino acid residues at the binding site [42, 43], thus, strengthening and specification of the binding. The presence of amino groups on the guanine base it forms hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions that further stabilize the drug-protein combination [44, 45]. The hydroxyl group on the quinoline ring improves solubility and forms H-bonds with critical residues. The presence of ether bonds and alkyl chains increases the molecule's stability and lipophilicity, affecting distribution and protein binding. The chloro group also helps molecules dissolve in lipids and interact with hydrophobic protein surfaces, promoting robust binding to protein targets.

Optimization of designed molecules

All structures underwent energy minimization by Gaussian 09 software using the Density Functional Theory (DFT), functional B3LYP at 6-31G basis set [46]. Also, we assumed that the energy of covalent bonds created by these segments would be of the same kind.

Pharmacological properties using ADMET studies

The most optimized geometry of the compounds after DFT calculations was subjected to evaluation of ADMET parameters using the online tool available at (http://www.swissadme.ch/) [47]. The study evaluated various attributes to classify compounds as ADMET competent and safe for in vivo use, assessing features like hydrogen bond donors and acceptors, Topological Polar Surface Area (TPSA), LogP, solubility, Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) permeability, Lipinski and lead-like rule violations, and synthetic accessibility, alongside physicochemical properties and models for BBB distribution, Plasma Protein Binding, metabolism via CYP2, and renal excretion through OCT2.

Molecular docking studies

AutoDock4 was used for molecular docking and the results were visualized using PyMol molecular visualizer and Biovia Discovery Studio. The 3D protein and ligand complex (6LU7) was obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). Protein preparation included the removal of non-essential components and water molecules, and the addition of polar hydrogens and Kollman charges. Based on the literature, a grid box was set around the active site with coordinates (-14.607, 19.162, 64.101) with a size (25x25x25) Å, extending 5-10 Å beyond crucial residues. After the docking simulation, the docking poses were analyzed based on their ranking. Binding interactions were examined, and results were visualized through PyMol and Biovia Discovery Studio.

PES scan

Mulliken charge analysis helps understand the electronic charge distribution within molecules, identifying regions prone to electrophilic and nucleophilic attacks [48]. Electrostatic potential maps (MEP) from DFT calculations are used to explore potential intermolecular interactions between drug systems and receptors, with MEPs providing a color-coded visualization of the molecule's reactivity to such attacks, showing the most electropositive sites in blue and the most electronegative in red [49–51].

MD simulation studies

The preparation of topologies for small molecules involved several steps, beginning with structure development and optimization. MD simulations lasting 150 ns were conducted on the best-docked complex using the GROMACS 22.4 package on an HPC cluster. The simulation setup included boundary conditions (1000x1000x1000), the CHARMM36 force field, and the TIP3P explicit solvent model. The system was hydrated, parameterized, and placed in a cubic box with a 3 Å boundary, with ions added. Equilibration occurred over 100 picoseconds at 300K with a 2 femtosecond time step, maintaining pressure coupling at 1 bar. The simulation analysis measured RMSD, Root mean Square Fluctuations (RMSF), and protein-ligand binding to assess ligand stability. The binding free energy (ΔGbind) was calculated using the free energy equation, with Molecular Mechanics Generalized Born Surface Area (MM-GBSA) rescoring improving docking results and binding affinity predictions.

ΔGbind = Gcomplex – Gprotein – Gligand

= ΔEMM+ΔGGB+ΔGSA – TΔS

= ΔEvdw+ΔEle+ΔGGB+ΔGSA – TΔS

MM-GBSA rescoring is a highly effective computational method used to improve docking results and make more accurate predictions of binding affinities. By integrating precise solvation effects and thorough molecular mechanics energies, MM-GBSA yielded a more accurate assessment of the binding free energy. The validation of its association with experimental binding affinities has established its indispensability in drug discovery, rendering it a vital element of structure-based drug design workflows. The preparation of topologies for small molecules entails a series of steps. It begins with the development and optimization of the structure, followed by the assignment of atom types and charges. Finally, relevant tools and force fields are used to generate topology and parameter files. Also, validating the generated topologies ensured the reliability of subsequent simulations.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

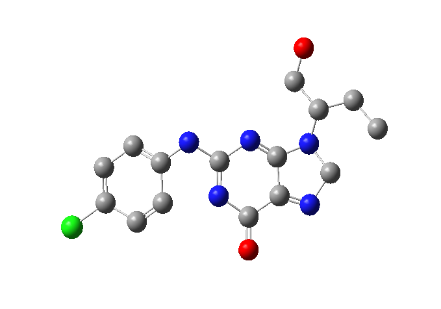

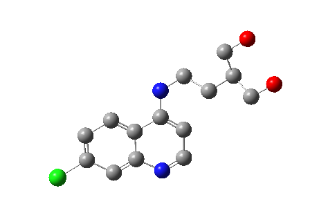

All the designed core and analogue structures were drawn using ChemDraw to ensure optimal geometry which summarizes the molecular structures and highlights the key compounds chosen for analysis [table 1]. Ten core hybrid structures were designed from relevant fragments of HCQ and Penciclovir [table 2, Series 1]. These structures were subjected to ADMET filtration, eventually discarding PH-3 as it did not pass through the filtration [table 3]. The remaining structures were subjected to docking out of which PH-6 showed the least binding energy [table 4].

PH-6 was further developed into 10 analogues [table 2, Series 2]. Series 2 compounds were further subjected to screening by ADMET and docking [table 3, table 5]. PH-6a, amongst them, was found to be most suitable for MD simulation studies. The results are discussed in detail in the following sections.

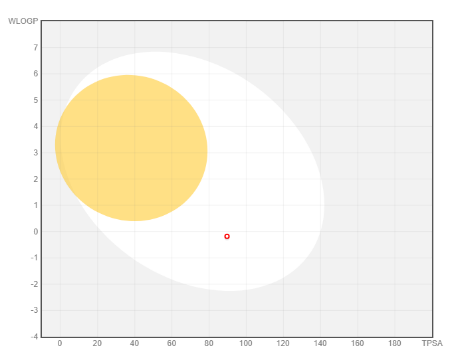

Fig. 2: Boiled-egg plot of PH-6a

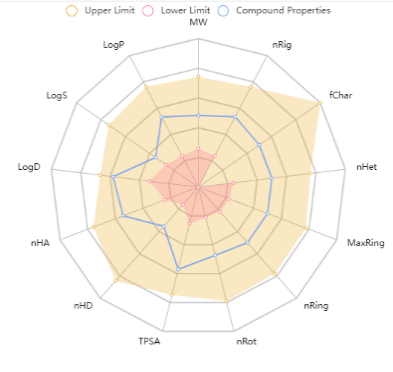

Fig. 3: Bioavailability radar of PH-6a

Table 1: Structures of the designed core and analogue molecules

| Structures of the core molecules | Structures of the analogue molecules |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Physicochemical and ADMET properties

The ADMET characteristics of the designed compounds are presented in table 3. The permeability of the BBB refers to the compound's capacity to enter the Central Nervous System (CNS) [52]. Almost all core compounds, except PH-3, showed impermeability to the CNS whereas, all the 10 analogues of PH6 (PH6a-j) exhibited impermeability and thus were classified as non-toxic to the CNS. The BOILED-Egg [fig. 3] study shows that it can be considered as an oral drug and from the bioavailability radar [fig. 4] it is well within all the boundaries of the characteristics of a drug. All the analogues exhibited favourable adherence to the Lipinski rule of five, as well as satisfactory pharmacokinetic and toxicological profiles. Due to its impermeability to the CNS, adherence to the Lipinski rule of 5 lead-likeliness, and synthetic accessibility of the compound, PH-6a was considered more appropriate for additional research. PH-6a exhibits minimal toxicity and demonstrates high efficiency in specifically targeting the virus and its associated pathways within the body. If a compound has enough antiviral action, has acceptable levels of toxicity, and can be efficiently delivered to the infection site, it still has a high promise as a therapeutic agent, even if it cannot pass through the BBB.

Table 2: Optimized structures of designed molecules and analogues molecules

| Structure-series 1 (Core Hybrid molecules) | Structure-series 2 (Analogues of Top hit molecules of series-1) |

PH-1

(Z)-2-amino-8-((E)-3-(ethyl(2-hydroxyethyl) amino) allylidene)-8,9-dihydro-6H-purin-6-one |

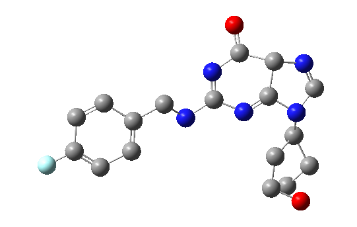

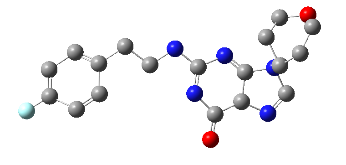

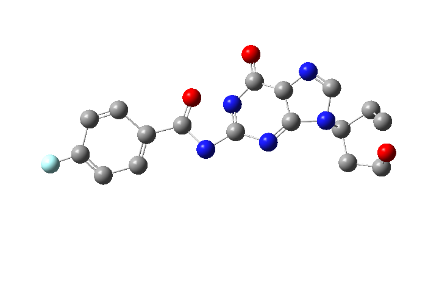

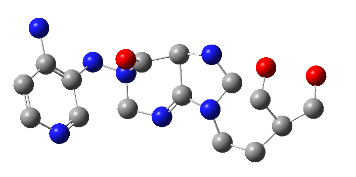

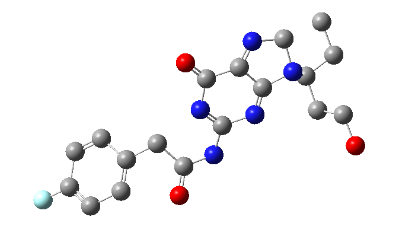

PH-6a

2-((4-chlorobenzyl) amino)-9-(1-hydroxypentan-3-yl)-5,9-dihydro-6H-purin-6-one |

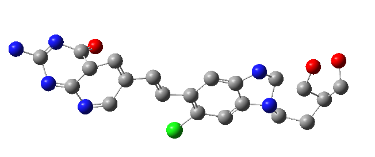

PH-2

2-amino-8-((4-amino-7-chloroquinolin-6-yl) methyl)-8,9-dihydro-6H-purin-6-one |

PH-6b

2-((4-chlorophenyl) amino)-9-(1-hydroxybutan-2-yl)-8,9-dihydro-6H-purin-6-one |

PH-3

2-(2-((7-chloroquinolin-4-yl)amino)ethyl)propane-1,3-diol |

PH-6c

2-((4-fluorobenzyl) amino)-9-(1-hydroxypentan-3-yl)-5,9-dihydro-6H-purin-6-one |

PH-4

(E)-2-amino-6-(2-(7-amino-3-(4-hydroxy-3-(hydroxymethyl) butyl)-2,3-dihydro-1H-imidazo[4,5-b] pyridin-6-yl) vinyl)-7-chloropyrido[2,3-d] pyrimidin-4(4aH)-one |

PH-6d

2-((4-fluorophenethyl) amino)-9-(1-hydroxypentan-3-yl)-5,9-dihydro-6H-purin-6-one |

PH-5

E)-2,5-diamino-6-(2-(6-chloro-1-(4-hydroxy-3-(hydroxymethyl) butyl)-2,3-dihydro-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-5-yl) vinyl) pyrido[2,3-d] pyrimidin-4(4aH)-one |

PH-6e

2-((4-chlorophenethyl)amino)-9-(1-hydroxypentan-3-yl)-5,9-dihydro-6H-purin-6-one |

PH-6

2-((4-fluorophenyl)amino)-9-(1-hydroxypentan-3-yl)-5,9-dihydro-6H-purin-6-one |

PH-6f

4-chloro-N-(9-(1-hydroxypentan-3-yl)-6-oxo-5,9-dihydro-6H-purin-2-yl) benzamide |

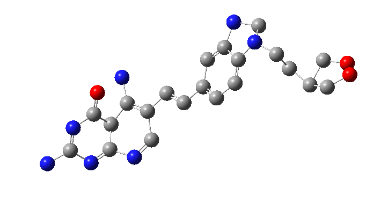

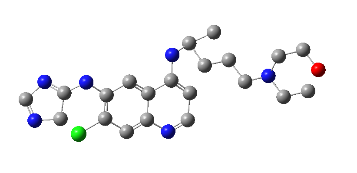

PH-7

2-amino-5-((7-chloro-4-((5-((2-hydroxyethyl) (hydroxymethyl)amino) pentan-2-yl) amino) quinolin-6-yl) amino) pyrimidin-4(5H)-one |

PH-6g

4-fluoro-N-(9-(1-hydroxypentan-3-yl)-6-oxo-5,9-dihydro-6H-purin-2-yl)benzamide |

PH-8

1-((4-aminopyridin-3-yl)amino)-9-(4-hydroxy-3-(hydroxymethyl)butyl)-1,2,5,7,8,9-hexahydro-6H-purin-6-one |

PH-6h

2-(4-chlorophenyl)-N-(9-(1-hydroxypentan-3-yl)-6-oxo-5,9-dihydro-6H-purin-2-yl)acetamide |

PH-9

2-((4-((6-((4H-imidazol-5-yl) amino)-7-chloroquinolin-4-yl) amino) pentyl) (ethyl)amino) ethan-1-ol |

Ph-6i

2-(4-fluorophenyl)-N-(9-(1-hydroxypentan-3-yl)-6-oxo-8,9-dihydro-6H-purin-2-yl)acetamide |

PH-10

2-amino-8-((4-hydroxy-3-(hydroxymethyl)butyl)(octan-2-yl)amino)-6H-purin-6-one |

PH-6j

2-((4-chlorophenyl)amino)-7,9-bis(1-hydroxypentan-3-yl)-5,7,8,9-tetrahydro-6H-purin-6-one |

Molecular docking

Active site analysis of protein

Mpro of SARS-CoV-2 exhibits a high degree of conservation and demonstrates a 96% sequence match to the SARS-CoV virus that emerged in 2002 [53]. The receptor-binding domain of Mpro from SARS-CoV-2 exhibits similarity to that of SARS-CoV, despite certain alterations in the amino acid sequence [54]. The catalytic dyad, formed by residues Cys145 and His41 imparts the proteolytic property to SARS-CoV-2Mpro [55–57]. This active site has garnered significant attention from researchers globally because of its ability possibly impede replication of the virus [58]. The in-built N3 inhibitor of 6LU7 forms additional interactions with multiple residues, including Phe140, Gly143, His164, Glu166, Gln189, and Thr190 along with those in the dyad. Glu166 facilitates the accurate placement of the substrate, while His164 contributes to the stabilization of the transition state by transferring protons. Both residues indirectly assist the catalytic dyad by preserving the conformation of the active site and enabling essential proton exchanges. These residues play a vital role in preserving the overall structure of the enzyme, essential for its efficient functioning. Any alterations in these amino acid residues can result in a reduction of the protein's structural integrity and a decline in its capacity to catalyse chemical reactions [37].

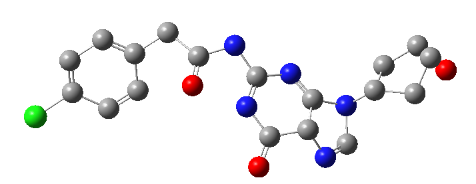

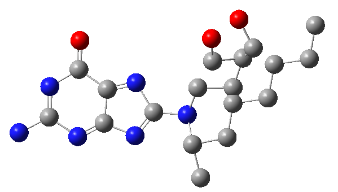

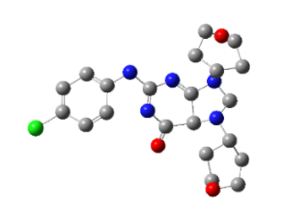

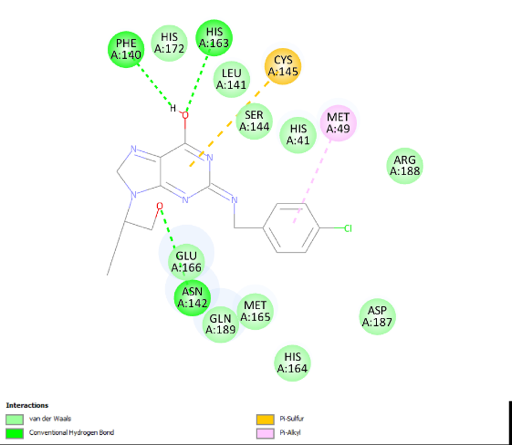

Docking results of compounds of Series 1 and Series 2 are presented in table 4 and table 5 respectively. The top molecule (PH-6a) showed the lowest binding energy (-7.58 kcal/mol) as compared to what was selected for molecular dynamics simulation. This binding energy was compared to 6.4 kcal/mol of the co-crystallized ligand, N3. The key interactions included both H-bond and hydrophobic interactions as shown in table 5. PH-6a formed hydrogen bonds with the amino acid residues Glu166, Phe140, and His163. Additionally, compound PH-6a formed an extra hydrogen bond with Cys145, as seen in table 5 and fig. 4.

It can be seen that the two aromatic rings of compounds PH-6a formed a pi-bond with Met49 and Cys145, with a bond distance of 2.00 Å and 1.89 Å. Additionally, the =C-OH group of the purine ring in the Penciclovir part of PH-6a formed hydrogen bonds with Phe140 and His163, with a bond distance of 1.98 Å and 2.25 Å respectively. The main chain carbonyl oxygen atom of Phe140 interacts with the –OH group in the purine ring of the ligand through hydrogen bonding. The side chain nitrogen of His163 participated in hydrogen bonding with the oxygen atom in the –OH group in the purine ring of the ligand. The side chain carboxylate group of Glu166 forms hydrogen bonds with the –OH group in the extended alkyl chain of the ligand. The side chain carbonyl oxygen of Gln189 forms a hydrogen bond with the ligand. The side chain hydroxyl group of Thr190 interacts with the ligand via hydrogen bonding.

The re-docking with the co-crystallized ligand ‘N3’ resulted in an estimated binding energy of-6.97 kcal/mol, with key hydrogen linkage with the Main protease of SARS-CoV-2 at Met49, Asp187, His41, Phe140, Leu141, Asn142,Ser144, Cys145, Arg188, His163-164, and Gly143.

4a |

4b |

| Fig. 4a: 2-D diagram of the interactions of the docked complex of PH-6a with 6LU7 | Fig. 4b: 3-D diagram of the PH-6a-Mpro complex |

Table 4: Docking studies with structures of hybrid molecules

| Compound name | Residues with bond lengths (Å) | No of H-bonds | Binding energy (kcal/mol) | Structure |

| PH-1 | Leu141(2.5) Ser144 (1.9) Cys145 (3.3) Glu166 (3.2) Arg188 (2.0) Thr190 (2.4) | 6 | -3.9 | |

| PH-2 | Phe140 (2.1) His163 (3.4) His164 (2.2) | 4 | -8.32 | |

| PH-3 | His164 (2.1)Gln189 (2.2) | 2 | -4.43 | |

| PH-4 | Gly278 (1.8) Ala285 (3.3) | 2 | -3.54 | |

| PH-5 | Lys236 (2.2 and2.3),Tyr237 (1.9and2.1)Ala285 (2.5and2.8) | 6 | -4.49 | |

| PH-6 | Glu166 (1.8and1.9)Arg188 (2.0) | 3 | -7.42 | |

| PH-7 | Ser301 (2.6) | 1 | -1.87 | |

| PH-8 | Thr196 (1.8)Met235 (2.4)Glu240 (2.2) | 3 | -2.68 | |

| PH-9 | Gln189 (2.4) | 1 | -4.15 | |

| PH-10 | Gln110 (2.3)Phe294 (2.6) | 2 | -2.24 |

Table 5: Docking studies with structures of analogues molecules

| Compound name | Residues with bond lengths (Å) | No of H-bonds | Binding energy (kcal/mol) | Structure |

| PH-6a | Met49 (2.0) Phe140 (2.11) Cys145 (1.89) His163 (1.95) Glu166 (1.99) | 5 | -7.58 | |

| PH-6b | Met49 (1.9)His164 (3.2) | 2 | -7.2 | |

| PH-6c | Arg188 (2.4)Thr190 (2.0)Gln192 (2.1) | 3 | -6.64 | |

| PH-6d | Glu166 (2.8) Glu166 (2.9)Arg188(2.6) Arg188(2.9) Arg188(3.0)Thr190 (2.2 Thr190 (3.1) | 7 | -6.48 | |

| PH-6e | Gln189 (3.4)Thr190 (2.0)Gln192 (1.9) | 3 | -6.71 | |

| PH-6f | His41 (2.5)His164 (2.6) His164(2.4)Gln189 (2.7) |

4 | -6.74 | |

| PH-6g | His164 (2.2)Glu166 (3.10Gln189 (3.0) | 3 | -7.01 | |

| PH-6h | His164 (2.1)Glu166 (2.0)Gln189 (2.9) | 3 | -7.54 | |

| PH-6i | His164 (2.1)Glu166 (3.3) Glu (2.4)Gln189 (2.8) | 4 | -7.19 | |

| PH-6j | His164 (1.9) His164 (2.1)Glu166 (2.5)Arg188 (2.8)Thr190 (2.0)Gln192(2.0) |

6 | -7.04 |

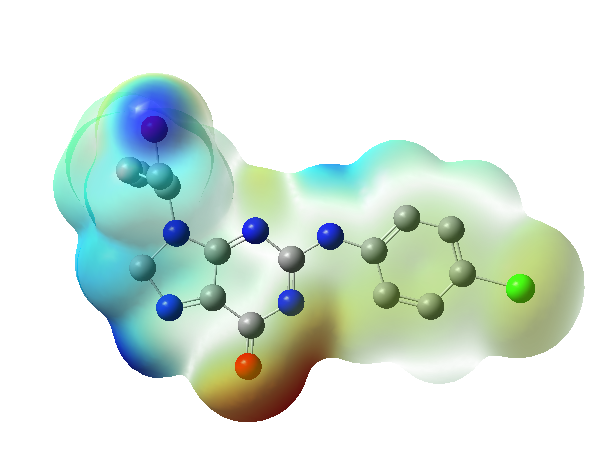

PES scan

The computed MEP plots for the top hit molecule, as shown in fig. 5, highlight that the hydrogen atom attached to the alcohol group is more vulnerable to nucleophilic attacks, while the oxygen atom attached to the heterocyclic ring is prone to electrophilic attacks.

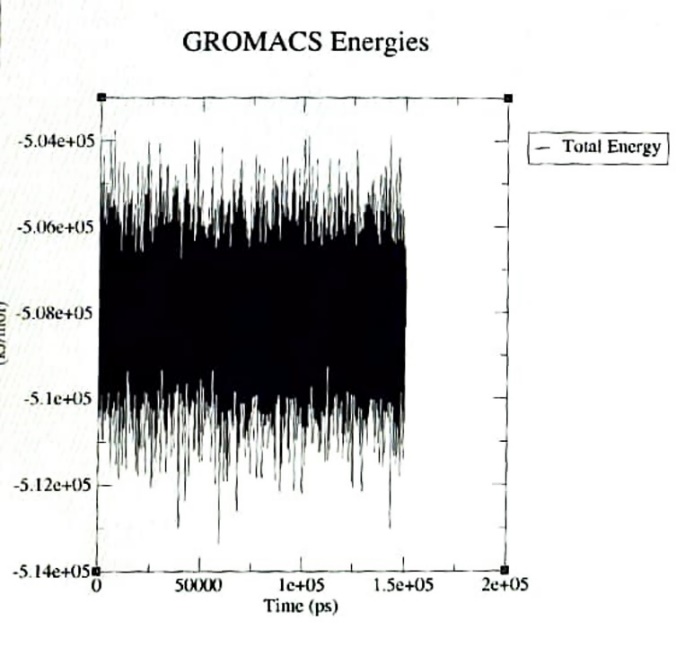

MD simulation

The simulation results are emphasized based on the examination of RMSD, RMSF and hydrogen bonds. The RMSD indicates that the lead compound PH-6a was within the acceptable range of 3 Å suggesting that PH-6a was strongly bound within the active cavity of Mpro. The average RMSD value of PH-6a was 1Å, as shown in the RMSD graph fig. 6. The ligand’s heavy atoms did not exceed the size of the protein, as indicated by the RMSD figure, which demonstrated the stability of the complex. The RMSF trajectories provide essential insights into the complex stability. Low values or less variability imply well-organized complex regions with minimal distortion Fig.7. The energy of binding of the compound PH-6a was analysed based on the final 1000 frames of the equilibrated simulated trajectories using GROMACS [59]. The investigation found that the total energy of the compound PH-6a was-5.06 kcal/mol, as depicted in fig. 8.

Fig. 5: MEP plot of the top hit molecule (PH-6a), *Red colour indicating zones of negative electrostatic potential. These areas are electron-rich, and associated with nucleophilic sites in the molecule, while the bluish colour indicating positive electrostatic potential zones. These areas are electron-deficient, usually associated with electrophilic sites and Green represents regions of neutral electrostatic potential. These areas are neither strongly electron-rich nor electron-deficient regions represent negative, positive and zero electrostatic potentials respectively

Fig. 6: RMSD of the complex

Fig. 7: RMSF of the complex

Compound PH-6a demonstrated significant results in the simulation studies, exhibiting a greater degree of stability in its interaction compared to the co-crystallized ligand. This indicates that compound PH-6a has a higher likelihood of being an effective inhibitor for suppressing Mpro. To conclude, the designed hybrid compound PH-6a exhibited favorable pharmacokinetic and docking characteristics against SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. Significant interactions were noted with binding site residues, such as Met49, Phe140, Cys145, His163, and Glu166, crucial for enzyme function [60]. PH-6a demonstrated a binding energy of-7.58 kcal/mol, which is equivalent to the reported binding energies of the co-crystallised N3 inhibitor (-7.5 to-8.3 kcal/mol) and exceeds that of repurposed Covid drugs, Boceprevir (-6.0 to-7.0 kcal/mol) and Calpain inhibitors (-5.5 to-7.0 kcal/mol) [61, 62]. A detailed comparison of binding energies of 6LU7 inhibitors are given in table 6. PH-6a established supplementary hydrogen bonds with Cys145, in addition to pi-bonds associated with its purine and quinoline rings, hence augmenting binding stability. RMSD (1 Å) and RMSF (<0.3 Å) studies demonstrated structural stability, characterized by 3-4 persistent hydrogen bonds and substantial hydrophobic interactions throughout the simulations. Although PH-6a's MM-GBSA binding free energy (-5 kcal/mol) was inferior to that of N3 (-28 kcal/mol), its van der Waals and electrostatic interactions enhanced its stability. These findings correspond with research emphasizing the importance of His163, Glu166, and Cys145 in Mpro inhibition, showing PH-6a’s promise as a viable treatment candidate.

Fig. 8: Total energy of the complex

Table 6: Binding energy comparison of PH-6a against other known 6LU7 inhibitors

| 6LU7 inhibitors | Binding Energy (kcal/mol) | References |

| PH-6a | -7.58 | Current study |

| Lopinavir | -6.4 | [63] |

| Ritonavir | -6.5 | [64] |

| Favipiravir | -5.0 | [65] |

| Kaempferol | -6.0 to-8.0 | [66] |

| N3 | -6.97 | (re-docked) |

CONCLUSION

Because of its remarkable ability to inhibit the Mpro of SARS-CoV-2, the PH-6a hybrid molecule stood out among the twenty hybrid compounds that we were able to create. The unusual combination of a heterocyclic ring that contains nitrogen, an amine linker, and a carbonyl group that is capable of undergoing tautomerization results in a significant increase in the binding efficacy. It has been demonstrated that PH-6a has a strong affinity for the active site of Mpro, and it specifically targets Cys145, which is part of the catalytic dyad pair. This suggests that it can prevent the virus from spreading from person to person during transmission. Molecular dynamics simulations were conducted to assess the stability of the Mpro-PH-6a complex. The analysis revealed that the stability of the Mpro-PH-6a complex was comparable to that of the co-crystallized ligand-Mpro complex, confirming the robustness of the binding interactions. PH-6a demonstrates remarkable promise as a viable option that could be further investigated as a potential antiviral candidate. Furthermore, prior to determining whether or not it is beneficial, additional in vitro validation is required to show that it is effective.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTOHRS CONTRIBUTIONS

Thejus Varghese Thomas: Simulations, data curation, writing original draft, and evaluation. Anil Kumar S.: Conceptualization, writing original draft, literature review, evaluation of work. Amrita Thakur: Literature review, writing and critical evaluation, review and editing.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there are no competing interests

REFERENCES

Ali Kanso M, Omeiche ZA, Hijazi MA, El Lakany A, Aboul ELA M. Antiviral potential of herbal medicine in fighting COVID-19 pandemic re-investigation of herbal monographs. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2024;16(9):18-25. doi: 10.22159/ijpps.2024v16i9.51681.

Hui DS, Azhar EI, Memish ZA, Zumla A. Human coronavirus infections severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) middle east respiratory syndrome (MERS) and SARS-CoV-2. 2nd ed. 2nd ed. Vol. 4, Encyclopedia of Respiratory Medicine. Elsevier Incorporated; 2021.

Pfenning Butterworth A, Buckley LB, Drake JM, Farner JE, Farrell MJ, Gehman AM. Interconnecting global threats: climate change biodiversity loss and infectious diseases. Lancet Planet Health. 2024;8(4):e270-83. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(24)00021-4, PMID 38580428.

Astra Zeneca admits its COVID vaccine Covishield can cause rare side effect times of India. CMS. Available from: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/life-style/health-fitness/health-news/astrazeneca-admits-its-covid-vaccine-can-cause-rare-side effect/articleshow/109710995. [Last accessed on 02 May 2024]

Ibrahim IM, Abdelmalek DH, Elshahat ME, Elfiky AA. COVID-19 spike host cell receptor GRP78 binding site prediction. J Infect. 2020;80(5):554-62. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.02.026, PMID 32169481.

Thiel V, Ivanov KA, Putics A, Hertzig T, Schelle B, Bayer S. Mechanisms and enzymes involved in SARS coronavirus genome expression. J Gen Virol. 2003;84(9):2305-15. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19424-0, PMID 12917450.

Hilgenfeld R. From SARS to MERS: crystallographic studies on coronaviral proteases enable antiviral drug design. FEBS Journal. 2014;281(18):4085-96. doi: 10.1111/febs.12936, PMID 25039866.

Agostini ML, Andres EL, Sims AC, Graham RL, Sheahan TP, LU X. Coronavirus susceptibility to the antiviral remdesivir (GS-5734) is mediated by the viral polymerase and the proofreading exoribonuclease. Mbio. 2018;9(2):e00221-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00221-18, PMID 29511076.

Ivanov KA, Thiel V, Dobbe JC, Van Der Meer Y, Snijder EJ, Ziebuhr J. Multiple enzymatic activities associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus helicase. J Virol. 2004;78(11):5619-32. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.11.5619-5632.2004, PMID 15140959.

V Kovski P, Kratzel A, Steiner S, Stalder H, Thiel V. Coronavirus biology and replication: implications for SARS-CoV-2. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021;19(3):155-70. doi: 10.1038/s41579-020-00468-6, PMID 33116300.

Nahir CF, Putra MY, Wibowo JT, Lee VS, Yanuar A. The potential of Indonesian marine natural product with dual targeting activity through SARS-COV-2 3CLPRO AND PLPRO: an in silico studies. Int J App Pharm. 2023;15(5):171-80. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2023v15i5.48416.

Muralikrishnan A, Kubavat J, Vasava M, Jupudi S, Biju N. Investigation of anti-sars cov-2 activity of some tetrahydro curcumin derivatives: an in silico study. Int J App Pharm. 2023;15(1):333-9. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2023v15i1.46288.

Vibhute S, Kasar A, Mahale H, Gaikwad M, Kulkarni M. Niclosamide: a potential treatment option for COVID-19. Int J App Pharm. 2023;15(1):50-6. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2023v15i1.45850.

Frediansyah A, Nainu F, Dhama K, Mudatsir M, Harapan H. Remdesivir and its antiviral activity against COVID-19: a systematic review. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. 2021 Jan;9:123-7. doi: 10.1016/j.cegh.2020.07.011, PMID 32838064.

Samaee H, Mohsenzadegan M, Ala S, Maroufi SS, Moradimajd P. Tocilizumab for treatment patients with COVID-19: recommended medication for novel disease. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;89(A):107018. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.107018, PMID 33045577.

Kaptein SJ, Jacobs S, Langendries L, Seldeslachts L, Ter Horst S, Liesenborghs L. Favipiravir at high doses has potent antiviral activity in SARS-CoV-2−infected hamsters whereas hydroxychloroquine lacks activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(43):26955-65. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2014441117, PMID 33037151.

Gentry CA, Thind SK, Williams RJ, Hendrickson SC, Kurdgelashvili G, Humphrey MB. Development of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with rheumatic conditions on hydroxychloroquine monotherapy vs. patients without rheumatic conditions: a retrospective propensity matched cohort study. Am J Med Sci. 2023;365(1):19-25. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2022.08.006, PMID 36103912.

Mohamed K, Yazdanpanah N, Saghazadeh A, Rezaei N. Computational drug discovery and repurposing for the treatment of COVID-19: a systematic review. Bioorg Chem. 2021;106:104490. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2020.104490, PMID 33261845.

Narwat A, DUA M, Goyal A. Safety monitoring of COVID-19 vaccine: in a Tertiary Care Hospital in Haryana. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2023;15(3):35-7.

Mahdi MF, Alsaad HN. Design synthesis and hydrolytic behavior of mutual prodrugs of NSAIDs with gabapentin using glycol spacers. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2012;5(10):1080-91. doi: 10.3390/ph5101080, PMID 24281258.

Song B, Liu X, Dong H, Roy R. Mir-140-3P induces chemotherapy resistance in esophageal carcinoma by targeting the NFYA-MDR1 axis. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2023;195(2):973-91. doi: 10.1007/s12010-022-04139-5, PMID 36255597.

Ciaffaglione V, Modica MN, Pittala V, Romeo G, Salerno L, Intagliata S. Mutual prodrugs of 5-fluorouracil: from a classic chemotherapeutic agent to novel potential anticancer drugs. Chem Med Chem. 2021 Dec 6;16(23):3496-512. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.202100473, PMID 34415107.

Ghanbari R, Teimoori A, Sadeghi A, Mohamadkhani A, Rezasoltani S, Asadi E. Existing antiviral options against SARS-CoV-2 replication in COVID-19 patients. Future Microbiol. 2020 Dec;15:1747-58. doi: 10.2217/fmb-2020-0120, PMID 33404263.

Wang M, Cao R, Zhang L, Yang X, Liu J, XU M. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020;30(3):269-71. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0, PMID 32020029.

Ravishankar N, Sadhana P, Thakur A, Singh T. Denudation of COVID-19 genome. In: 13th International Conference on Computing Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT); 2022. doi: 10.1109/ICCCNT54827.2022.9984268.

Gogineni V, Schinazi RF, Hamann MT. Role of marine natural products in the genesis of antiviral agents. Chem Rev. 2015 Sep 23;115(18):9655-706. doi: 10.1021/cr4006318, PMID 26317854.

Clark JD, Flanagan ME, Telliez JB. Discovery and development of janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors for inflammatory diseases. J Med Chem. 2014 Jun 26;57(12):5023-38. doi: 10.1021/jm401490p, PMID 24417533.

Parker WB. Enzymology of purine and pyrimidine antimetabolites used in the treatment of cancer. Chem Rev. 2009 Jul 8;109(7):2880-93. doi: 10.1021/cr900028p, PMID 19476376.

HU S, Chen J, Cao JX, Zhang SS, GU SX, Chen FE. Quinolines and isoquinolines as HIV-1 inhibitors: chemical structures action targets and biological activities. Bioorg Chem. 2023 Jul 1;136:106549. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2023.106549, PMID 37119785.

Zhang J, Wang S, BA Y, XU Z. 1,2,4-triazole-quinoline/quinolone hybrids as potential anti-bacterial agents. Eur J Med Chem. 2019 Jul 15;174:1-8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.04.033, PMID 31015103.

Nqoro X, Tobeka N, Aderibigbe BA. Quinoline based hybrid compounds with antimalarial activity. Molecules. 2017 Dec 19;22(12):2268. doi: 10.3390/molecules22122268, PMID 29257067.

Pallaval VB, Kanithi M, Meenakshisundaram S, Jagadeesh A, Alavala M, Pillaiyar T. Chloroquine analogs: an overview of natural and synthetic quinolines as broad spectrum antiviral agents. Curr Pharm Des. 2021;27(9):1185-93. doi: 10.2174/1381612826666201211121721, PMID 33308117.

TGS, Subramanian S, Eswaran S. Des synth study antibacterial antitubercular act quinoline hydrazone hybrids. Heterocyclic Communications. 2020;26(1):137-47. doi: 10.1515/hc-2020-0109.

TG S, Subramanian S, Eswaran S. Design synthesis and study of antibacterial and antitubercular activity of quinoline hydrazone hybrids. Heterocycl Commun. 2020;26(1):137-47. doi: 10.1515/hc-2020-0109.

Barmade Mahesh A, Chapter SMK. 12-biological spectrum of vicinal diaryl-substituted fused heterocycles. In: Yadav MR, Murumkar PR, editors. Ghuge RBBTVDSH, editors. Elsevier; 2018. p. 363-99.

Consortium TC, Achdout H, Aimon A, Bar David E, Barr H, Ben Shmuel A. Open science discovery of oral non-covalent SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitor therapeutics. Biorxiv. 2021;10:339317.

Jin Z, Zhao Y, Sun Y, Zhang B, Wang H, WU Y. Structural basis for the inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 main protease by antineoplastic drug carmofur. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2020;27(6):529-32. doi: 10.1038/s41594-020-0440-6, PMID 32382072.

Duong CQ, Nguyen PT. Exploration of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro noncovalent natural inhibitors using structure based approaches. ACS Omega. 2023 Feb;8(7):6679-88. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.2c07259, PMID 36844600.

Zhang L, Lin D, Sun X, Curth U, Drosten C, Sauerhering L. Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease provides a basis for design of improved α-ketoamide inhibitors. Science. 2020;368(6489):409-12. doi: 10.1126/science.abb3405, PMID 32198291.

Farghaly TA, Masaret GS, Abdulwahab HG. Novel 1,3-indanedione thiazole hybrids as small molecule SARS-COV-2 main protease inhibitors with potential anti-coronaviral activity. Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds. 2024;44(10):6941-56. doi: 10.1080/10406638.2024.2318442.

Cardoso Ortiz J, Leyva Ramos S, Baines KM, Gomez Duran CF, Hernandez-Lopez H, Palacios Can FJ. Novel ciprofloxacin and norfloxacin tetrazole hybrids as potential antibacterial and antiviral agents: targeting S. aureus topoisomerase and SARS-CoV-2-MPro. J Mol Struct. 2023;1274:134507. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2022.134507, PMID 36406777.

Koshland JR, DE. The key lock theory and the induced fit theory. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1995 Jan 3;33(23-24):2375-8. doi: 10.1002/anie.199423751.

Jones S, Thornton JM. Principles of protein protein interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996 Jan;93(1):13-20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.13, PMID 8552589.

Chang KY, Varani G. Nucleic acids structure and recognition. Nat Struct Biol. 1997 Oct;4 Suppl:854-8. PMID 9377158.

Bauman JD, Patel D, Dharia C, Fromer MW, Ahmed S, Frenkel Y. Detecting allosteric sites of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase by X-ray crystallographic fragment screening. J Med Chem. 2013 Apr;56(7):2738-46. doi: 10.1021/jm301271j, PMID 23342998.

Rahman AA. Software news and updates gabedit a graphical user interface for computational chemistry software. J Comput Chem. 2012;32:174-82.

Daina A, Michielin O, Zoete V. Swiss ADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics drug likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci Rep. 2017 Jan;7:42717. doi: 10.1038/srep42717, PMID 28256516.

Anil Kumar S, Bhaskar BL. Preliminary investigation of drug impurities associated with the anti-influenza drug favipiravir an insilico approach. Comput Theor Chem. 2021;1204:113375. doi: 10.1016/j.comptc.2021.113375, PMID 34306990.

Sasidharan Pillai AK, Bhaskar BL. Computational spectral and bioavailability studies of venlafaxine cyclic impurity. ECS Trans. 2022;107(1):13439-49. doi: 10.1149/10701.13439ecst.

Anil Kumar S, Bhaskar BL. Development and validation of two spectrophotometric methods for the estimation of dronedarone impurity molecule: (5-Amino-2-butyl-3-benzofuranyl)[4-[3-(dibutylamino)propoxy]phenyl]methanone. Mater Today Proc. 2021;46:2940-4. doi: 10.1016/j.matpr.2020.11.913.

Kumar SA, Bhaskar BL. Computational and spectral studies of 3,3’-(propane-1,3-diyl)bis(7,8-dimethoxy-1,3,4,5-tetrahydro-2H-benzo[d]azepin-2-one). Heliyon. 2019;5(9):e02420. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02420, PMID 31687545.

Jalal K, Khan K, Haleem DJ, Uddin R. In silico study to identify new monoamine oxidase type a (MAO-A) selective inhibitors from natural source by virtual screening and molecular dynamics simulation. J Mol Struct. 2022;1254:132244. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.132244.

Cardoso WB, Mendanha SA. Molecular dynamics simulation of docking structures of SARS-CoV-2 main protease and HIV protease inhibitors. J Mol Struct. 2021;1225:129143. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.129143, PMID 32863430.

Ahmad P, Alvi SS, Hasan I, Khan MS. Targeting SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro) and human ACE-2: a virtual screening of carotenoids and polyphenols from tomato (Solanum Lycopersicum L.) to combat COVID-19. Intelligent Pharmacy. 2024;2(1):51-68. doi: 10.1016/j.ipha.2023.10.008.

Walls AC, Park YJ, Tortorici MA, Wall A, McGuire AT, Veesler D. Structure function and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Cell. 2020;181(2):281-292.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.058, PMID 32155444.

Hasan A, Paray BA, Hussain A, Qadir FA, Attar F, Aziz FM. A review on the cleavage priming of the spike protein on coronavirus by angiotensin converting enzyme-2 and furin. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2021;39(8):3025-33. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1754293, PMID 32274964.

Khalifa A, Gammal G, Fadl S, Gohary M, Barakat M. Laboratory microbiological and chemical analysis for detection of water pollution in fresh water fish farms. Alex J Vet Sci. 2020;66(1):76. doi: 10.5455/ajvs.111726.

Kim S, Kim DM, Lee B. Insufficient sensitivity of RNA dependent RNA polymerase gene of SARS-CoV-2 viral genome as confirmatory test using Korean COVID-19 cases; 2020.

Basic doubt regarding frames in the trajectory user discussions GROMACS forums; 2022.

Zhang S, Zhong N, Xue F, Kang X, Ren X, Chen J. Three dimensional domain swapping as a mechanism to lock the active conformation in a super active octamer of SARS-CoV main protease. Protein Cell. 2010;1(4):371-83. doi: 10.1007/s13238-010-0044-8, PMID 21203949.

Pfizer Inc. Pfizers novel COVID-19 oral antiviral treatment candidate reduced risk of hospitalization or death by 89%. In: Interim analysis of Phase 2/3 EPIC-HR study | Pfizer. Pfizer Website; 2021.

MA C, Sacco MD, Hurst B, Townsend JA, HU Y, Szeto T. Boceprevir GC-376 and calpain inhibitors II, XII inhibit SARS-CoV-2 viral replication by targeting the viral main protease. Cell Res. 2020;30(8):678-92. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0356-z, PMID 32541865.

Merzouki M, Challioui A, Bourassi L, Abidi R, Bouammli B, El Farh L. In silico evaluation of antiviral activity of flavone derivatives and commercial drugs against SARS-CoV-2 main protease (3CLpro). Moroccan J Chem. 2023;11(1):129-43.

Muralidharan N, Sakthivel R, Velmurugan D, Gromiha MM. Computational studies of drug repurposing and synergism of lopinavir oseltamivir and ritonavir binding with SARS-CoV-2 protease against COVID-19. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2021;39(7):2673-8. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1752802, PMID 32248766.

Patel U, Desai K, Dabhi RC, Maru JJ, Shrivastav PS. Ecting phytochemicals of Rosmarinus officinalis L. for targeting SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro): a computational study. J Mol Model Bioprosp. 2023;29(5):1-15.

Menacer R, Bouchekioua S, Meliani S, Belattar N. New combined Inverse-QSAR and molecular docking method for scaffold based drug discovery. Comput Biol Med. 2024 Mar;180:108992. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2024.108992, PMID 39128176.