Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 2, 2025, 165-173Original Article

GIP/GLP-1 DUAL AGONIST TIRZEPATIDE AMELIORATES RENAL ISCHEMIA/REPERFUSION DAMAGE IN RATS

GHADA A. ALKHAFAJI1, ALI M. JANABI2*

1Pharmacy Department, Babylon Directorate of Health, Babel, Iraq. 2Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Kufa, Najaf, Iraq

*Corresponding author: A. M. Janabi; *Email: alim.hashim@uokufa.edu.iq

Received: 09 Nov 2024, Revised and Accepted: 10 Jan 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: Renal Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury (RIRI) initiates a cascade of deleterious events resulting in acute kidney injury with high mortality rates. Tirzepatide has anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic and antioxidant as well as activation of both autophagy and Protein Kinase B (PKB or Akt) signaling pathway. This study examines the potential nephroprotective effect of tirzepatide against RIRI in rats.

Methods: Twenty-eight male rats (Sprague Dawley) were split into four groups: sham, Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury (IRI), Distilled Water (D. W) and tirzepatide. The Sham group underwent identical procedures without bilateral renal pedicle clamping, whereas IRI group was exposed to 30 min of bilateral renal ischemia followed by 24 h of reperfusion. The vehicle group received distilled water intraperitoneally 2 h before ischemia, and the tirzepatide group received 3 mg/kg tirzepatide intraperitoneally 2 h before ischemia. Study parameters including urea, creatinine, Kidney Injury Molecule-1 (KIM-1), interleukin-6 (IL-6), caspase-3, Akt, autophagic protein microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3-B (LC3-B) and glutathione (GSH), and histopathological changes were examined.

Results: RIRI resulted in a significant elevation in serum urea, serum creatinine and renal levels of KIM-1, IL-6, caspase-3, Akt, and LC3-B while a concurrently reduction in renal GSH level. Tirzepatide treatment diminished the severity of kidney damage by alleviating inflammatory apoptotic and autophagy markers, augmenting antioxidant activity and improving histopathological consequences.

Conclusion: Tirzepatide elucidates significant nephroprotective effects in RIRI, via its anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antiapoptotic properties and activation of both autophagy and Akt signaling pathway.

Keywords: Renal ischemia/reperfusion, Tirzepatide, Acute renal damage, Caspase-3, Akt, LC3-B, GSH

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i2.53156 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Ischemia is the term used to describe the state of tissue hypoperfusion. Hypoperfusion of tissue may result from a variety of conditions, including organ transplantation, acute coronary syndrome, sepsis, and limb injury [1, 2]. When blood flow is rapidly restored after a brief period of ischemia (a lack of oxygen and nutrients caused by vascular occlusion), tissues undergo damage known as IRI. This process triggers strong inflammatory and oxidative stress reactions [3, 4]. Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) is a clinical phenomenon characterized by fast renal dysfunction and high mortality rates; IRI is a pathological disease that contributes to AKI in the kidney [5, 6]. AKI is estimated to account for 2 million deaths worldwide annually and is a growing global health concern [7, 8]. Prerenal, intrarenal, and postrenal causes define three main groups of probable etiologies for AKI. Most cases, including heart failure, fluid or blood loss and sepsis (about 50%) are related to prerenal insults brought on by a drop in arterial blood pressure [9]. Depleting adenosine triphosphate, which alters mitochondrial structure and function, is one of the primary early targets of RIRI. It is the primary energy source concentrated in renal proximal tubular cells [10, 11]. Many factors, including local oxygen tension, cellular energy needs, and innate resistance to hypoxia determine hypoxia status. Kidney hypoxia primarily affects proximal tubular cells [12, 13]. A therapeutic approach to safeguard renal tissue involves mitigating inflammatory responses, as the inflammatory cascade resulting from renal ischemia-reperfusion injury exacerbates kidney damage [14]. Chemokines are important inflammatory mediators that control the expression of adhesion molecules, proinflammatory cytokines, leukocyte infiltration, and activation [15, 16]. The biological process of apoptosis, or programmed cell death, eliminates damaged, sick, or dying cells [17]. Autophagy involves a complex process and regulatory mechanism crucial in healthy and pathological circumstances [18]. It is adaptive, limiting derangements and deaths. However, autophagy promotes cell death in other settings, such as apoptosis and necrosis [19]. It is common for IRI to be accompanied by increased levels of autophagy in tissues such as the heart, brain, liver, and kidneys. Both apoptosis and acute inflammatory response were successfully modulated by regulating autophagy levels [20-22]. Antioxidant properties of GSH manifest themselves differently. GSH shields cells from apoptosis by interacting with signaling pathways that are both pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic [23]. GSH safeguards cellular components by neutralizing Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and hydrogen peroxide, preventing lipid peroxidation and ROS-induced damage to proteins and DNA [24]. Tirzepatide, a new dual agonist targeting Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 (GLP-1) and the Glucose-dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide (GIP), has potential nephroprotective properties and is among the most efficient multi-agonists for diabetic control [25].

This study investigates the biochemical markers and histological alterations in male rats to determine whether tirzepatide exhibits nephroprotective benefits against RIRI. Tirzepatide was tested for its ability to activate anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, and autophagy pathways and its antioxidant effect.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal preparation

The University of Kufa/Faculty of Science generously donated 28 male Sprague Dawley adult and juvenile rats weighing ~200 g and their age of 15 to 20 w. The rats were housed in the animal facility of the Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Kufa. With a 12-hour light/dark cycle, temperature was set at 24±2 °C, and humidity was set to 60-65%; the animals were housed in a separate chamber utilizing a group-caging system. The rats' typical diet consisted of food and water. All experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at University of Kufa after submitting the required applications (letter number 6685-10/3/2024).

Study design

A random assignment was made to divide the twenty-eight male Sprague Dawley rats into four groups, with seven rats in each group: Sham, IRI, vehicle distilled water+IRI, and tirzepatide+IRI treatment groups. Rats in the Sham group underwent the same surgery and anesthesia as in the other groups. Still, without ischemic induction, they experienced bilateral Renal Ischemia (bRI) for 30 min, followed by reperfusion for 24 h. The IRI group has bRI for 30 min [26], followed by reperfusion for 24 h [27]. The D. W group vehicle for tirzepatide was given 2 h before ischemia. Subsequently, 30 min of bRI was followed by reperfusion for 24 h. The pretreated group was given tirzepatide 3 mg/kg 2 h before ischemia induction, followed by 30 min of bRI and 24 h of reperfusion [28]. A laparotomy incision was used to collect blood and kidney samples after 24 h. In summary, the operation was carried out while rats were under total anesthesia, which involved injecting 100 mg/kg of ketamine and 10 mg/kg of xylazine intraperitoneally.

Preparation of tirzepatide

Tirzepatide powder was obtained from Hangzhou Go Top Peptide Biotech Co., Ltd, Zhejiang, China. Tirzepatide was dissolved in D. W immediately before use and given intraperitoneally [29] according to manufacturer instructions.

Model of ischemia/reperfusion damage in the kidneys

Experimental surgery was performed on the body's dorsal (retroperitoneal) regions. Ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) were administered to anesthetize the rats and reduce pain [30] via intraperitoneal injection into the abdominal cavity. The body temperature of the anaesthetized rat were maintained at 36.8 °C to 37.3 °C by positioning the rat in the prone position on the feedback-controlled heating pads. Through the use of flank incisions, surgical procedures were carried out to expose the renal hilum, hence reducing the likelihood of any intra-abdominal organ damage occurring during the dissection process. Surgical instruments were used to make a 1.5 cm vertical flank incision, layer by layer, through the skin, fascia, and muscle layer. The renal hilum was exposed by dissecting the peri-nephric tissue on the medial kidney side with a cotton swab. The timer was promptly activated following the intended 30 min ischemia interval. The success of ischemia was confirmed by uniformly observing the kidney's coloration change to a dusky appearance within a few minutes [31].

The pedicle clamp came free at the end of the ischemia interval. The kidney was replaced into the retroperitoneal space. Then, the surgical posture was sutured in two layers. Before wound closure, the retroperitoneal region received 1 ml of 38 °C pre-warmed 0.9% saline injection [32]. The procedure was repeated on the animal model's contralateral side, which was planned for bilateral RIRI. The bilateral IRI clamping of the renal arteries typically affects the overall renal mass. It elevates serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen levels within 24 h, which are characteristic indicators of AKI in a clinical context [33]. After the anesthetic recovery, the rats were carefully moved back to their cages, with some food provided on the floor. Their general condition and appearance were regularly observed and monitored during this time. Subsequently, animals were sacrificed under heavy anesthesia after 24 h, and kidney tissue samples were collected for further analysis.

Collection of samples

Blood samples collection for measurement of renal function

About 2-4 ml of blood were collected immediately from the heart while rats were still anesthetized at the end of the procedure. The blood sample was centrifuged in a gel tube free of anticoagulant to obtain serum, which was used to determine urea and creatinine using a spectrophotometric technique at 550 nm absorbance. This method is a quantitative measurement and very helpful in determining the concentrations of the compound.

Tissue preparation for measurement of inflammatory, apoptotic, autophagy and oxidative parameters

After the blood samples had been collected, kidney tissue specimens were collected. Kidneys were extracted from each animal, then chopped and divided into two equal parts. One-half fixed in 10 % formalin for medical pathology evaluation. In contrast, the other half was kept at-80 °C until frozen before homogenizing with a high-intensity ultrasonic liquid processorin phosphate-buffered saline with a weight-to-volume ratio of 1:10, which also included 1 % triton X-100 and a protease inhibitor cocktail. Homogenates was centrifuged at 2000-3000 rpm. Supernatants were collected after 10-20 min at 4 °C used to determine KIM-1, IL-6, Caspase-3, PKB/Akt, LC3-B, and GSH kits using available ELISA technique following the instructions provided by the manufacturer, from Sun Long Biotech Co., Ltd., China.

Tissue preparation for histopathology

The renal tissue section was fixed within 10 % formalin, alcohol-based dehydration, cleaned with xylene, and then submerged in paraffin. The kidney tissues were fixed in paraffin and then sectioned into slices 5 μm thick. After staining these portions with hematoxylin, eosin, and trichrome [34].

Assessment of urea and creatinine levels

A spectrophotometric technique is used to estimate serum urea and creatinine, which depends on measuring light absorption or transmission of chemical reactions within a specific wavelength. This method is a quantitative measurement and very helpful in determining the compounds' concentrations; urea and creatinine levels were measured at 550 nm absorbance.

Measurement of KIM-1, IL-6, caspase-3, Akt, LC3-B and GSH

The level of KIM-1, IL-6, caspase-3, Akt, LC3-B and GSH were determined by utilizing the corresponding ELISA kits. Following the manufacturer's instructions, the ELISA kits were ordered from Sun Long Biotech Co., Ltd, China.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad (La Jolla, CA, USA) software developed by GraphPad Prism 9.5 was used to analyze the data in this study. The mean±Standard Error of mean (SEM) was used to express all results unless otherwise specified. One-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used to analyze study data, followed by Bonferroni multiple comparison test. Additionally, the Kruskal-Wallis test was utilized to compare alterations in histopathological changes among study groups. Statistical significance was determined using a P value<0.05 for every test.

RESULTS

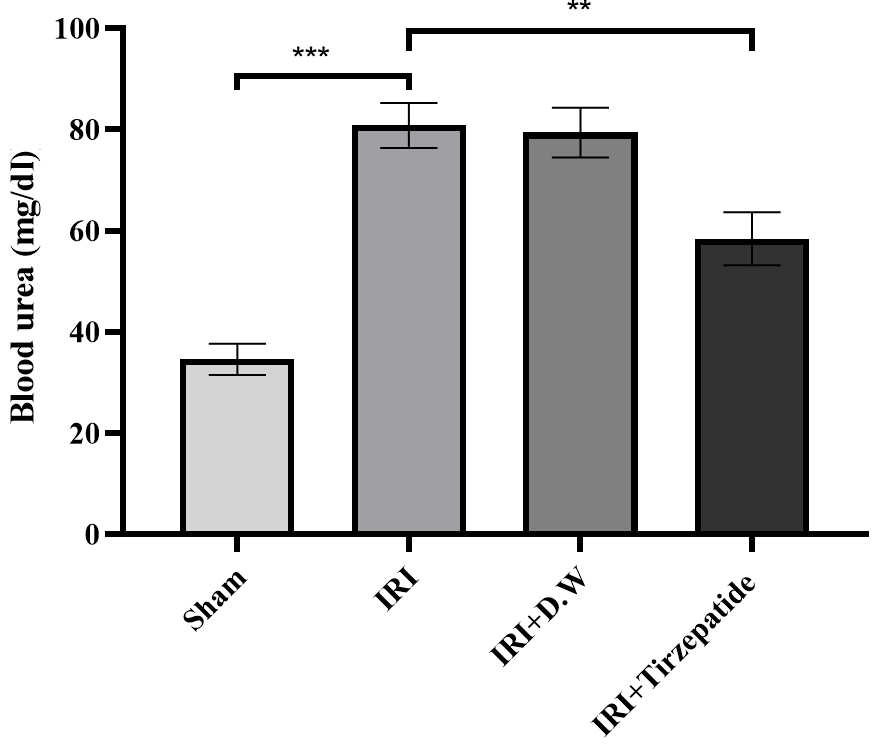

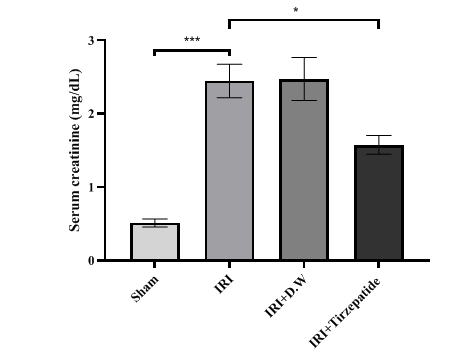

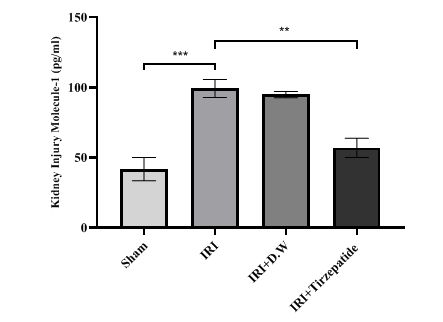

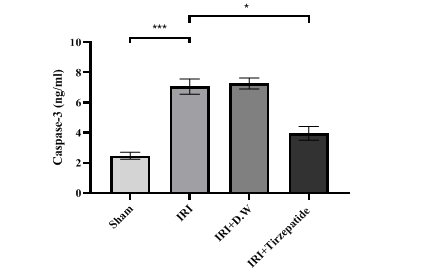

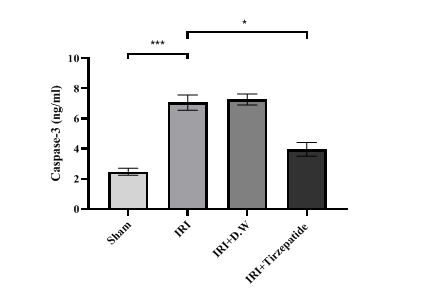

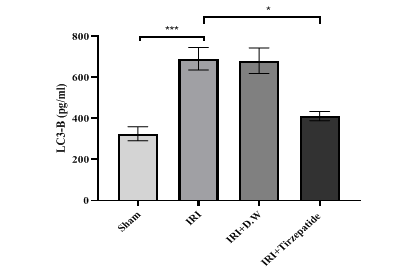

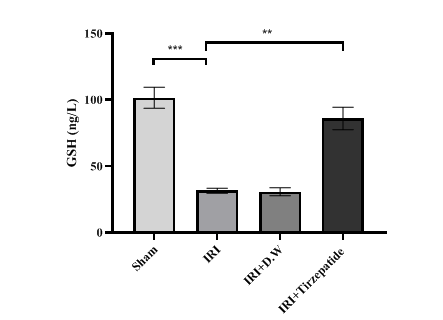

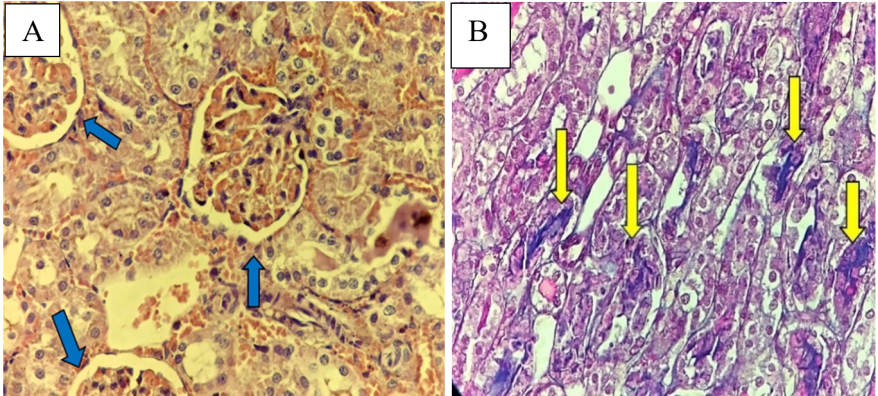

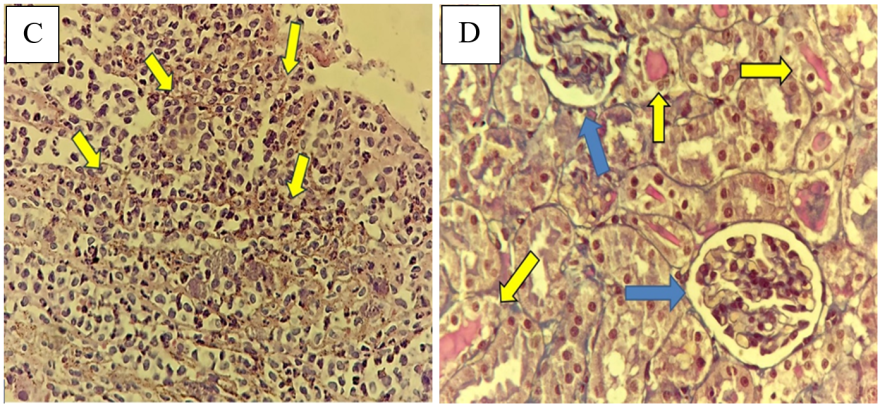

The onset of RIRI was signified by a notable increase in urea (fig. 1) and creatinine (fig. 2), KIM-1 (fig. 3), IL-6 (fig. 4), caspase-3 (fig. 5), Akt (fig. 6), and LC3-B levels (fig. 7); and a markedly decrease in GSH levels (fig. 8) in IRI rats when compared with sham group. To exclude the effect of vehicle, rats treated with D. W (the vehicle of tirzepatide) showed no significant differences in all study parameters in comparison with IRI group. Pretreatment with tirzepatide markedly improved RIRI, as evidenced by a substantial decrease in urea, creatinine, KIM-1, the inflammatory mediator IL-6, the apoptotic marker caspase-3, Akt, and the autophagic marker LC3-B levels when compared with levels with IRI rats. The renal tissue concentration of the antioxidant enzyme GSH was substantially elevated in the tirzepatide pretreated group when compared to IRI rats. When compared to sham group, IRI group displayed notable kidney impairment with a mean score of ~ 3.8 (fig. 9, fig. 10). Pretreatment with tirzepatide reduces kidney damage in IRI rats significantly when compared with untreated rats (fig. 9, fig. 10).

Fig. 1: Serum urea level of study groups. Data were represented as mean±SEM, n = 7 rats per group.; **P<0.01, ***P<0.001

Fig. 1 After 30 min of ischemia, rats were reperfused for 24 h. They were pretreated 2h before ischemia with either a vehicle D. W, tirzepatide (3 mg/kg), or left untreated (sham and IRI group). Serum urea concentrations were assessed utilizing the spectrophotometric technique. Following one-way ANOVA, data were analyzed using Bonferroni multiple comparison test. Data were represented as mean±SEM, n = 7 rats per group; **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Fig. 2: Serum creatinine levels of study groups. Data were represented as mean±SEM, n = 7 rats per group; *P<0.05, ***P<0.001

Fig. 2 After 30 min of ischemia, rats were reperfused for 24 h. They were pretreated 2h before ischemia with either a vehicle D. W, tirzepatide (3 mg/kg), or left untreated (sham and IRI group). Serum creatinine concentrations were assessed utilizing the spectrophotometric technique. Following one-way ANOVA, the data were analyzed using Bonferroni multiple comparison test. Data were represented as mean±SEM, n = 7 rats per group; *P<0.05, ***P<0.001.

Fig. 3: Renal KIM-1 levels of study groups. Data were represented as mean±SEM, n = 7 rats per group.; **P<0.01, ***P<0.001

Fig. 3 After 30 min of ischemia, rats were reperfused for 24 h. They were pretreated 2 h before ischemia with either a vehicle D. W, tirzepatide (3 mg/kg), or left untreated (sham and IRI group). Renal KIM-1 concentrations were assessed utilizing ELISA kit. Following one-way ANOVA, the data were analyzed using Bonferroni multiple comparison test. Data were represented as mean±SEM, n = 7 rats per group; **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Fig. 4 After 30 min of ischemia, rats were reperfused for 24 h. They were pretreated 2 h before ischemia with either vehicle D. W, tirzepatide (3 mg/kg), or left untreated (sham and IRI group). Renal IL-6 concentrations were assessed utilizing ELISA kit. Following one-way ANOVA, the data were analyzed using Bonferroni multiple comparison test. Data were represented as mean±SEM, n = 7 rats per group; *P<0.05, ***P<0.001.

Fig. 5 After 30 min of ischemia, rats were reperfused for 24 h. They were pretreated 2 h before ischemia with either vehicle D. W, tirzepatide (3 mg/kg), or left untreated (sham and IRI group). Renal caspase-3 concentrations were assessed utilizing ELISA kit. Following one-way ANOVA, data were analyzed using Bonferroni multiple comparison test. Data were represented as mean±SEM, n = 7 rats per group; *P<0.05, ***P<0.001.

Fig. 6 After 30 min of ischemia, rats were reperfused for 24 h. They were pretreated 2 h before ischemia with either a vehicle D. W, tirzepatide (3 mg/kg), or left untreated (sham and IRI group). Renal Akt concentrations were assessed utilizing ELISA kit. Following one-way ANOVA, data were analyzed using Bonferroni multiple comparison test. Data were represented as mean±SEM, n = 7 rats per group; *P<0.05, ***P<0.001.

Fig. 4: Renal IL-6 levels of study groups. Data were represented as mean±SEM, n = 7 rats per group.; *P<0.05, ***P<0.001

Fig. 5: Renal caspase-3 level of study groups. Data were represented as mean±SEM, n = 7 rats per group; *P<0.05, ***P<0.001

Fig. 6: Renal PKB/Akt levels of study groups. Data were represented as mean±SEM, n = 7 rats per group; *P<0.05, ***P<0.001

Fig. 7: Renal LC3-B levels of study groups. Data were represented as mean±SEM, n = 7 rats per group.; *P<0.05, ***P<0.001

Fig. 7 After 30 min of ischemia, rats were reperfused for 24 h. They were pretreated 2 h before ischemia with either a vehicle D. W, tirzepatide (3 mg/kg), or left untreated (sham and IRI group). Renal LC3-B concentrations were assessed utilizing ELISA kit. Following one-way ANOVA, data were analyzed using Bonferroni multiple comparison test. Data were represented as mean±SEM, n = 7 rats per group; *P<0.05, ***P<0.001.

Fig. 8 After 30 min of ischemia, rats were reperfused for 24 h. They were pretreated for 2 h before ischemia with either a vehicle D. W, tirzepatide (3 mg/kg), or left untreated (sham and IRI group). Renal GSH concentrations were assessed utilizing ELISA kit. Following one-way ANOVA, data were analyzed using Bonferroni multiple comparison test. Data were represented as mean±SEM, n = 7 rats per group; **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Fig. 8: Renal GSH levels of study groups. Data were represented a0s mean±SEM, n = 7 rats per group; **P<0.01, ***P<0.001

Fig. 9: Histopathological mean score of renal injury severity. *P<0.05, ***P<0.001

Fig. 10 (A) Sham group has normal renal tubule histology (blue arrow); stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HandE) X400. (B) IRI group; kidney tubules with score four including focal tubular necrosis highlighted by cytoplasmic cyanophilic staining including the disappearance of brush borders, cytoplasmic eosinophilia, dilated tubules and hemorrhage>75% (yellow arrow), stained with trichrome X400. (C) D. W group, kidney tubules with score four damage. Cytoplasmic eosinophilia, dilated tubules, cast formation, and hemorrhage (yellow arrows); stained with HandE X400. (D) Tirzepatide group, kidney tubules with damage score one associated with occasional intratubular protein casts (yellow arrows) with preserved renal corpuscle and tubules (blue arrows); stained with trichrome X400.

Fig. 10: Representative histological micrographs of renal tissue of study groups

DISCUSSION

Reduced glomerular filtration rates define AKI, a sudden and fast drop in kidney function [35]. One frequent clinical consequence that might result in AKI development is IRI [36]. About 20% to 50% of hospitalized patients have AKI, and its prevalence is rising [37]. AKI has been identified as a primary condition caused by RIRI, leading to renal tubular dilatation, inflammatory damage, apoptotic cell death, and,eventually, renal failure [38]. One of the key elements in the tissue damage brought on by IR is the inflammatory response [39], which plays a key mediator of various problems including pancreatitis [40]. This study indicated that serum levelsof urea and creatinine were markedly elevated in the IRI and D. W groups when compared with sham group, which agreed with previous findings by Liu and colleagues [41]. Pretreatment with tirzepatide markedly reduced the levels of urea and creatinine in comparison to the IRI group (fig. 1, fig. 2, fig. 3). This conclusion supports earlier research which highlighted tirzepatide beneficial impact on kidney tissue in individuals with DM type 2 [42]. Tirzepatide pretreated group significantly reduced the level of KIM-1 when compared with IRI and vehicle groups (fig. 3). Interestingly, no previous studies described the effect of tirzepatide on KIM-1. Hence, a study showed that semaglutide (GLP-1 receptor agonist) had significantly reduced KIM-1 in the treated group when compared with the control group in accelerated diabetic kidney disease in a mouse model of hypertension [43].

Furthermore, the level of inflammatory mediator IL-6 was lowered in the tirzepatide group compared with both IRI and vehicle groups (fig. 4). Inflammation is a crucial pathophysiological process of IRI. RIRI can provoke the aggregation of inflammatory cells; inflammatory mediators such as Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (TNF-α), IL-6, and IL-8 are produced, and adhesion molecules rise, leading to injury to organs [44]. Inflammatory mediator levels are higher in individuals with oxidative stress [45]. This observation is consistent with an earlier study reported by Yang and colleagues that showed a lower level of IL-6 in tirzepatide treated group in a mouse model exposed to diabetic nephropathy and thus, tirzepatide caused inhibition of inflammatory response [46]. To the best of our knoweledge, no previous studies described the effect of tirzepatide on IL-6, especially in RIRI.

Hypoxia leads to the buildup of intracellular calcium, which activates caspases in ischemic tissues, serving as a signal of cell death [47]. In contrast to the sham condition following RIRI, the groups subjected to IRI or given D. W had significantly higher levels of caspase-3 in their renal tissues (fig. 5). An earlier study performed by Kopp and coworkers showed that caspase-3 levels decreased by the effect of tirzepatide treatment that exhibits anti-neuroinflammatory properties in addition to neurotrophic and neuroprotective activities in cellular models of neurodegeneration employing human and mouse microglial cell lines [48].

Pretreatment with tirzepatide intraperitoneally 2 h before induction of ischemia significantly decreased Akt level; there was no significant difference between treatment and sham groups, and it possibly is a way of protection for this medication (fig. 6). Likewise, administration of semaglutide significantly upregulated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) expression while maintaining levels comparable to the sham group, indicating that GLP-1 agonism could have a pivotal role in enhancing cell survival by regulating the PI3K/Akt axis [49].

Data in this study showed that pretreatment with tirzepatide 2 h before induction of ischemia significantly reduced autophagy level on ischemic renal tissues to the level of sham in comparison with those in both IRI and vehicle groups as a protective mechanism to promote cell survival comparison with those in both IRI and vehicle groups (fig. 7). There were no previous studies explaining the effect of dual-agonists GLP-1 and GIP receptors on LC3-B in RIRI, but there were studies explaining the autophagic effect on GLP-1 agonist in other conditions. A previous study found that GLP-1 receptor agonist protects heart tissue from oxidative stress and reduces proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, and Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 (MCP-1). Stimulating GLP-1 receptor reduces cardiomyocyte ferroptosis, necroptosis, pyroptosis, and death. GLP-1 receptor stimulation promotes myocardial autophagy and mitophagy activity. It prevents IR cardiac injury in patients with acute myocardial infarction [50]. A study by Guan and colleagues showed that early reaction acting in a reno-protective role during renal IR, where autophagy happened temporally dependent earlier than the beginning of cell death. The upregulation of autophagy could be a possible approach to treating acute kidney damage [51].

Pretreatment with tirzepatide before ischemia induction in rats could significantly elevate the concentration of GSH in renal tissues when compared with IRI groups (fig. 8). This finding agreed a nother study, which examined the nephroprotective effect of tirzepatide in activating the antioxidant marker; tirzepatide demonstrates potential adjunct therapy in the colistin treatment regimen to mitigate colistin-induced nephrotoxicity and neurotoxicity because it inhibits ER stress-related markers and has anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anti-apoptotic qualities [52].

The study demonstrated that there were no significant alterations in the renal tissue of the sham group. The IRI mean score severity of the kidney portion was substantially higher than that of the sham group. Injury to the renal tubules was more severe when the score was higher (fig. 9, fig 10). This result was compatible with a previous study which demonstrated that rats exposed to bilateral renal ischemia for 30 min and then reperfusion for 2 h had significant tubular damage severity score in the RIRI group [53]. Among GLP-1 receptor agoists, a study revealed by Tiba and colleagues on semaglutide indicated that renal tissue subjected to IRI exhibited significant damage, which is marked by congestion, vascular thickening, irritation, and blood loss when compared with renal tissue observed in the sham group [49]. However, a novel treatment with tirzepatide showed a notable decrease in kidney function, as seen by reduced damage score. Precise mechanisms behind its protective effects on the kidneys and renal tissue require more investigations.

CONCLUSION

According to the results of current study, tirzepatide significantly reduces renal injury in IRI rats via its anti-inflammatory effect by decreasing the kidney injury marker KIM-1, inflammatory marker IL-6, anti-apoptotic effect by lowering apoptotic marker caspase-3, activation of both cell survival pathway Akt and autophagy by reducing Akt and LC3-B to the normal level as a protective mechanism, finally, antioxidant effect by elevating antioxidant marker GSH.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

FUNDING

This research did not receive any specific funding from external sources.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed equally to this article. Alkhafaji, GA contributed to data collection, statistical analysis, and draft writing. Janabi, AM contributed to the main idea, design of the study and critical revision.

REFERENCES

Andrew R, Evans Laura E, Waleed A, Levy Mitchell M, Massimo A, Ricard F. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Crit Care Med. 2017;18(2):197-204.

Zuo Y, Wang Y, HU H, Cui W. Atorvastatin protects myocardium against ischemia-reperfusion injury through inhibiting miR-199a-5p. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2016;39(3):1021-30. doi: 10.1159/000447809, PMID 27537066.

Granger DN, Kvietys PR. Reperfusion injury and reactive oxygen species: the evolution of a concept. Redox Biol. 2015 Dec;6:524-51. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2015.08.020, PMID 26484802.

RJ, M SB, VY. Oxidative stress in acne vulgaris. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2022;14(11):73-6. doi: 10.22159/ijpps.2022v14i11.45967.

Kellum JA, Unruh ML, Murugan R. Acute kidney injury. BMJ Clin Evid. 2011 Mar 28;2011:2001. PMID 21443811. doi: 10.1038/s41572-021-00284-z.

Hoste EA, Clermont G, Kersten A, Venkataraman R, Angus DC, DE Bacquer D. Rifle criteria for acute kidney injury are associated with hospital mortality in critically ill patients: a cohort analysis. Crit Care. 2006;10(3):R73. doi: 10.1186/cc4915, PMID 16696865.

Murugan R, Kellum JA. Acute kidney injury: whats the prognosis? Nat Rev Nephrol. 2011;7(4):209-17. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2011.13, PMID 21343898.

Lewington AJ, Cerda J, Mehta RL. Raising awareness of acute kidney injury: a global perspective of a silent killer. Kidney Int. 2013;84(3):457-67. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.153, PMID 23636171.

Daniel Patschan GA. Acute kidney injury. J Inj Violence Res. 2015;7(1):19-26. doi: 10.5249/jivr.v7i1.604.

Weinberg JM, Venkatachalam MA, Roeser NF, Saikumar P, Dong Z, Senter RA. Anaerobic and aerobic pathways for salvage of proximal tubules from hypoxia-induced mitochondrial injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2000;279(5):F927-43. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.279.5.F927, PMID 11053054.

Chen Y, Fry BC, Layton AT. Modeling glucose metabolism and lactate production in the kidney. Math Biosci. 2017;289:116-29. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2017.04.008, PMID 28495544.

Liu BC, Tang TT, LV LL, Lan HY. Renal tubule injury: a driving force toward chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2018;93(3):568-79. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.09.033, PMID 29361307.

Lee JW, Lee KH. Comparison of renoprotective effects of febuxostat and allopurinol in hyperuricemic patients with chronic kidney disease. Int Urol Nephrol. 2019;51(3):467-73. doi: 10.1007/s11255-018-2051-2, PMID 30604229.

Stroo I, Stokman G, Teske GJ, Raven A, Butter LM, Florquin S. Chemokine expression in renal ischemia/reperfusion injury is most profound during the reparative phase. Int Immunol. 2010;22(6):433-42. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxq025, PMID 20410256.

Malek M, Nematbakhsh M. Renal ischemia/reperfusion injury; from pathophysiology to treatment. J Renal Inj Prev. 2015;4(2):20-7. doi: 10.12861/jrip.2015.06, PMID 26060833.

Hegner J, Patel J, Fong S, Jeffs S, PJ, Jeffs S. The role of specialist pharmacist in the management of adalinumab in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2021;13(11):30-3. doi: 10.22159/ijpps.2021v13i11.42451.

Fuchs Y, Steller H. Programmed cell death in animal development and disease. Cell. 2011;147(4):742-58. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.033, PMID 22078876.

Peters AE, Mihalas BP, Bromfield EG, Roman SD, Nixon B, Sutherland JM. Autophagy in female fertility: a role in oxidative stress and aging. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2020;32(8):550-68. doi: 10.1089/ars.2019.7986, PMID 31892284.

Kroemer G. Autophagy: a druggable process that is deregulated in aging and human disease. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(1):1-4. doi: 10.1172/JCI78652, PMID 25654544.

Turkmen K, Martin J, Akcay A, Nguyen Q, Ravichandran K, Faubel S. Apoptosis and autophagy in cold preservation ischemia. Transplantation. 2011;91(11):1192-7. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31821ab9c8, PMID 21577181.

Suzuki C, Isaka Y, Takabatake Y, Tanaka H, Koike M, Shibata M. Participation of autophagy in renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;368(1):100-6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.01.059, PMID 18222169.

Gotoh K, LU Z, Morita M, Shibata M, Koike M, Waguri S. Participation of autophagy in the initiation of graft dysfunction after rat liver transplantation. Autophagy. 2009;5(3):351-60. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.3.7650, PMID 19158494.

Masella R, DI Benedetto R, Vari R, Filesi C, Giovannini C. Novel mechanisms of natural antioxidant compounds in biological systems: involvement of glutathione and glutathione related enzymes. J Nutr Biochem. 2005;16(10):577-86. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2005.05.013, PMID 16111877.

Hanschmann EM, Godoy JR, Berndt C, Hudemann C, Lillig CH. Thioredoxins glutaredoxins and peroxiredoxins molecular mechanisms and health significance: from cofactors to antioxidants to redox signaling. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;19(13):1539-605. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4599, PMID 23397885.

Caruso I, Giorgino F. Renal effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists and tirzepatide in individuals with type 2 diabetes: seeds of a promising future. Endocrine. 2024;84(3):822-35. doi: 10.1007/s12020-024-03757-9, PMID 38472620.

Alaasam ER, Janabi AM, Al Buthabhak KM, Almudhafar RH, Hadi NR, Alexiou A. Nephroprotective role of resveratrol in renal ischemia-reperfusion injury: a preclinical study in sprague dawley rats. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2024;25(1):82. doi: 10.1186/s40360-024-00809-8, PMID 39468702.

Oxburgh L, DE Caestecker MP. Ischemia reperfusion injury of the mouse kidney. Kidney development. Methods Protoc. 2012:363-79.

Martin JA, Czeskis B, Urva S, Cassidy KC. Absorption distribution metabolism and excretion of tirzepatide in humans rats and monkeys. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2024;202:106895. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2024.106895, PMID 39243911.

Guo X, Lei M, Zhao J, WU M, Ren Z, Yang X. Tirzepatide ameliorates spatial learning and memory impairment through modulation of aberrant insulin resistance and inflammation response in diabetic rats. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1146960. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1146960, PMID 37701028.

Al Amir H, Janabi A, Hadi NR. Ameliorative effect of nebivolol in doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. J Med Life. 2023;16(9):1357-63. doi: 10.25122/jml-2023-0090, PMID 38107721.

Jallawee HQ, Janabi AM. Potential nephroprotective effect of dapagliflozin against renal ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats via activation of autophagy pathway and inhibition of inflammation oxidative stress and apoptosis. S East Eur J Public Health. 2024;24 Suppl 2:488-500. doi: 10.70135/seejph.vi.1009.

Cheng YT, TU YC, Chou YH, Lai CF. Protocol for renal ischemia-reperfusion injury by flank incisions in mice. Star Protoc. 2022;3(4):101678. doi: 10.1016/j.xpro.2022.101678, PMID 36208451.

Skrypnyk NI, Harris RC, DE Caestecker MP. Ischemia reperfusion model of acute kidney injury and post-injury fibrosis in mice. J Vis Exp. 2013;(78):50495. doi: 10.3791/50495, PMID 23963468.

Shishido T, Nozaki N, Yamaguchi S, Shibata Y, Nitobe J, Miyamoto T. Toll like receptor-2 modulates ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2003;108(23):2905-10. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000101921.93016.1C, PMID 14656915.

Goyal A DP, Hashim MF. Acute Kidney Inj (nursing). In: Stat Pearls Treasure Island (FL): In: Stat Pearls Treasure Island (FL); 2024.

Han SJ, Lee HT. Mechanisms and therapeutic targets of ischemic acute kidney injury. Kidney Res Clin Pract. 2019;38(4):427-40. doi: 10.23876/j.krcp.19.062, PMID 31537053.

Srisawat N, Kulvichit W, Mahamitra N, Hurst C, Praditpornsilpa K, Lumlertgul N. The epidemiology and characteristics of acute kidney injury in the Southeast Asia intensive care unit: a prospective multicentre study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020;35(10):1729-38. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfz087, PMID 31075172.

El Sabbahy ME, Vaidya VS. Ischemic kidney injury and mechanisms of tissue repair. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 2011;3(5):606-18. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.133, PMID 21197658.

Pallet N, Livingston M, Dong Z. Emerging functions of autophagy in kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2014;14(1):13-20. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12533, PMID 24369023.

Ghazi HS. Ibudilast and octreotide can ameliorate acute pancreatitis via downregulation of the inflammatory cytokines and nuclear factor kappa B expression. Ann Trop Med Public Health. 2019;22(8):1-9. doi: 10.36295/ASRO.2019.22081.

Liu LJ, YU JJ, XU XL. Kappa opioid receptor agonist U50448H protects against renal ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats via activating the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2018;39(1):97-106. doi: 10.1038/aps.2017.51, PMID 28770825.

Mima A, Nomura A, Fujii T. Current findings on the efficacy of incretin-based drugs for diabetic kidney disease: a narrative review. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023 Sep;165:115032. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2023.115032, PMID 37331253.

Dalboge LS, Christensen M, Madsen MR, Secher T, Endlich N, Drenic V. Nephroprotective effects of semaglutide as mono and combination treatment with lisinopril in a mouse model of hypertension accelerated diabetic kidney disease. Biomedicines. 2022;10(7):1661. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10071661, PMID 35884965.

Ahmad A, Sattar MA, Rathore HA, Khan SA, Lazhari MI, Afzal S. A critical review of pharmacological significance of hydrogen sulfide in hypertension. Indian J Pharmacol. 2015;47(3):243-7. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.157106, PMID 26069359.

Al Chlaihawi M, Janabi A. Azilsartan improves doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity via inhibiting oxidative stress proinflammatory pathway and apoptosis. J Med Life. 2023;16(12):1783-8. doi: 10.25122/jml-2023-0106, PMID 38585516.

Yang M, Zhang C. The role of innate immunity in diabetic nephropathy and their therapeutic consequences. J Pharm Anal. 2024;14(1):39-51. doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2023.09.003, PMID 38352948.

Ozbilgin S, Ozkardesler S, Akan M, Boztas N, Ozbilgin M, Ergur BU. Renal ischemia/reperfusion injury in diabetic rats: the role of local ischemic preconditioning. Bio Med Res Int. 2016;2016(1):8580475. doi: 10.1155/2016/8580475, PMID 26925416.

Kopp KO, LI Y, Glotfelty EJ, Tweedie D, Greig NH. Incretin-based multi-agonist peptides are neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory in cellular models of neurodegeneration. Biomolecules. 2024;14(7):872. doi: 10.3390/biom14070872, PMID 39062586.

Tiba AT, Qassam H, Hadi NR. Semaglutide in renal ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice. J Med Life. 2023;16(2):317-24. doi: 10.25122/jml-2022-0291, PMID 36937464.

Boshchenko AA, Maslov LN, Mukhomedzyanov AV, Zhuravleva OA, Slidnevskaya AS, Naryzhnaya NV. Peptides are cardioprotective drugs of the future: the receptor and signaling mechanisms of the cardioprotective effect of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(9):4900. doi: 10.3390/ijms25094900, PMID 38732142.

Guan X, Qian Y, Shen Y, Zhang L, DU Y, Dai H. Autophagy protects renal tubular cells against ischemia-reperfusion injury in a time-dependent manner. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;36(1):285-98. doi: 10.1159/000374071, PMID 25967967.

Hassan NF, Ragab D, Ibrahim SG, Abd El Galil MM, Hassan Abd El Hamid AH, Hamed DM. The potential role of tirzepatide as adjuvant therapy in countering colistin-induced nephro and neurotoxicity in rats via modulation of PI3K/p-Akt/GSK3-β/NF-kB p65 hub shielding against oxidative and endoplasmic reticulum stress and activation of p-CREB/BDNF/TrkB cascade. Int Immunopharmacol. 2024 Jun 30;135:112308. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2024.112308, PMID 38788447.

Alsaaty EH, Janabi AM. Moexipril improves renal ischemia/reperfusion injury in adult male rats. J Contemp Med Sci. 2024;10(1). doi: 10.22317/jcms.v10i1.1477.