Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 2, 2025, 174-189Original Article

THE POTENTIAL COMBINATION OF CENTELLA ASIATICA, CURCUMA LONGA, AND PIPER NIGRUM EXTRACTS IN TREATING BRAIN INJURY: IN VITRO, IN VIVO AND SILICO STUDIES

ARISTIANTI1*, MUHAMMAD ASWAD2, ARYADI ARSYAD3, NURSAMSIAR6, SYAMSU NUR4, ANDI ASADUL ISLAM5

1Department of Pharmacology, Medicine Faculty, Hasanuddin University, Makassar, South Sulawesi, Indonesia. 2Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry and Technology, Faculty of Pharmacy, Hasanuddin University, South Sulawesi, Indonesia. 3Department of Physiology, Medicine Faculty, Hasanuddin University, Makassar, South Sulawesi, Indonesia. 4Department of Pharmaceutical Analysis and Medicinal Chemistry, Almarisah Madani University, Makassar, South Sulawesi, Indonesia. 5Department of Neorosurgery, Medicine Faculty, Hasanuddin University, Makassar, South Sulawesi, Indonesia

*Corresponding author: Aristianti; *Email: aristianti@unhas.ac.id

Received: 12 Nov 2024, Revised and Accepted: 03 Feb 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: Traumatic brain injury is a head injury that causes brain dysfunction. This disorder can have a bad effect if not treated quickly and appropriately. This study aims to examine the extract of Gotukola (Centella asiatica), turmeric (Curcuma longa), and black pepper (Piper nigrum) as natural medicines that can treat brain injury problems.

Methods: The parameters tested in this study included testing the memory of experimental animals using the Y-Maze method, in vitro inhibition of glutaminase, and in silico research through molecular docking and molecular dynamics on the compounds of each extract that have been previously reported.

Results: Each extract had activity in increasing memory, but a combination formula of the three extracts showed a significant increase in memory (p<0.05, n = 5). The combination extract of gotu kola, turmeric, and black pepper in a ratio of 50:50:50 (combination 1), 25:50:50 (combination 5), and 25:12.5:50 (combination 8) continued its activity in inhibiting glutaminase. The results showed a significant decrease in glutaminase activity when applied to the three combination extract formulas. This study is also supported by in silico results showing that the asiaticoside compound identified in gotu kola extract, 1,5-bis (4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,4-pentadien-3-one compound from turmeric extract and Bacitritinib from black pepper extract have an important role in interacting with the target protein glutaminase with protein data bank 4O7D in molecular docking studies and interacting stably in molecular dynamics.

Conclusion: This study has supported the development of a combination extract formula of gotu kola, turmeric, and black pepper as a candidate for treating brain injury.

Keywords: Brain injury, Glutaminase, Natural resources, Molecular docking, Molecular dynamic

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i2.53173 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Brain injury is a force trauma (trauma) that affects the structure of the head, resulting in structural abnormalities and/or functional disorders of brain tissue [1]. Based on Indonesian Health data since 2018, the percentage of head injury cases was 11.9%, with the highest percentage in Gorontalo province at 17.9% [2]. Epidemiological data on brain injuries in Makassar City, Sout Sulawesi Province, Indonesia, especially at Dr Wahidin Sudirohusodo in 2005, numbered 861 cases; in 2006, there were 817 cases, and in 2007, there were 1078 cases [3].

Based on the effects on the head, injuries are classified into two mechanisms: primary injuries (Primary insult) and secondary injuries (secondary insult). Primary injury directly results from trauma that causes primary or mechanical damage. Meanwhile, secondary brain injury is described as a consequence of physiological disorders, such as ischemia, reperfusion, and hypoxia in areas of the brain at risk, sometime after the initial injury (primary brain injury) [4]. Secondary brain injury is sensitive to therapy, and its occurrence can be prevented. One of the causes of secondary brain injury is the excitotoxicity process mediated by the glutamine enzyme [5].

Glutamate is the main excitatory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system. It is important to keep glutamate concentrations low in the extracellular space to ensure adequate synaptic transmission and prevent excitotoxicity. Therefore, glutamate released from the presynaptic terminal must be removed from the synaptic cleft. In a healthy brain, toxic concentrations of glutamate can be prevented by the presence of excitatory amino acid transporters that take up glutamate [6, 7]. In astrocytes, glutamate is converted to glutamine by glutamine synthetase. Glutamine is released into the extracellular space taken up by adjacent neurons and used to synthesize glutamate with the help of the enzyme glutaminase. Some glutamine is also oxidized and completely degraded as an energy substrate. This glutamate-recycling process is known as the glutamate-glutamine cycle, and this cycle results in changes in neuronal metabolism between periods of activity and rest and the energetic relationship between astrocytes and neurons [8, 9].

Gotu Kola (Centella asiatica L.) is a plant that contains antioxidants and can provide antihyperglycemic and antihypertension effects [10, 11]. This shows that Gotu Kola has potential as an alternative therapy for traumatic brain injury [12]. Another plant that can be used is turmeric. The curcumin compound from turmeric (Curcuma longa L.) has the potential as an analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant [13, 14]. Administration of curcumin at a dose of 500 ppm orally for four weeks reduced oxidative stress and increased Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and C-AMP response element binding protein (CREB) levels in mice with a head injury model. These results illustrate that turmeric can reduce the negative impact of head injury, increasing synapse plasticity [15].

Black pepper (Piper nigrum L) is also a candidate plant widely used in treating epilepsy. Piperine, a piperidine alkaloid, is a major component of many pepper plant families [16]. Modern pharmacological studies show that piperine has a variety of effects, including anti-oxidant, immune regulation, anti-tumor, effects on increasing drug metabolism, as well as mood and cognitive disorders [17–19]. Piperine can affect many brain diseases due to its efficient absorption and high membrane permeability [16]. For example, it was found that piperine can block transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1 (TRPV1) channels instead of Ca2+ channels and is expected to become a new type of broad-spectrum antiepileptic drug. Black pepper contains the compound piperine. The piperin compound acts as an antioxidant, can inhibit oxidative stress, protects against free radicals and Radical Oxygen Species (ROS), and inhibits peroxidation [18, 20].

There is information on the chemical content of Gotu Kola, turmeric, and black piper plants and a history of their clinical use in treating brain injuries, making it possible to use a combination of these plants in treating and recovering from brain injuries. In this research, an assessment was carried out regarding the combined effects of these three plants as potential natural medicine candidates in treating brain injuries. The effects of combined dosage settings on the three plants were evaluated in vitro and in silico. This study was carried out to develop natural ingredient extracts into standardized herbal products and become phytopharmaceutical preparations for treating brain injuries in the future.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

The materials used in this research include distilled water, acetic acid (CH3COOH), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Merck-Germany), ethanol 70% v/v (C2H5OH), Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit for Glutamate Receptor Ionotropic-AMPA 1 (GRIA1) was purchased from Cloud-Clone Corp (USA), sulfuric acid (H2SO4) (Merck-Germany), filter paper, L-glutamine (Sigma-Aldrich), sodium acetate (Merck-Germany), sodium Carboxyl Methyl Cellulose (Merck-Germany), animal Rattus novergicus was purchased from animal laboratory Medical Faculty, Airlangga University-Indonesia. Sodium acetic (CH3COONa) (Merck-Germany) and Nessler's reagent (Merck-Germany), buscopan® (hyoscine), Tebokan forte®. Gotu Kola, black pepper, and turmeric plant samples were obtained in Biringkanaya District, Makassar City, South Sulawesi, Indonesia (5°06'47.8"S 119°30'29.0" E). The samples of gotu kola herb, turmeric rhizome, and black pepper have been determined the classification of the plants in the Pharmaceutical Biology laboratory, Faculty of Health Sciences, Almarisah Madani University by Dr. Marwati, M. Sc. with the respective specimen codes, namely H-086/III/2023 (gotu kola), R-1161/III/2023 (turmeric), and B-0026/III/2023 (black pepper).

Extraction method

Dry samples of Gotu Kola (Centella asiatica), turmeric (Curcuma domestica), and black pepper (Piper nigrum L.) powder each weighed 100 g. Then, each sample was extracted by maceration using 500 ml of 70% v/v ethanol solvent. Extraction was carried out for 3×24 h while stirring occasionally, after which it was filtered. Each filtrate obtained was then macerated for 1×24 h, then filtered and concentrated using a rotary evaporator until a thick extract was obtained. Gotu kola, black pepper, and turmeric extracts were each stored in the refrigerator at a temperature of 2-8 °C and then used in each treatment.

Animal handling procedure

The procedures for handling experimental animals (Rattus norvegicus) in this study have received approval from the Research Ethics Code Institute of the Faculty of Medicine, Hasanuddin University, Makassar, South Sulawesi, Indonesia, with ID number 40611IN4.6.4.5.31/PP36/2024. The test animal was a white rat (Rattus norvegicus) weighing 120 and 200 g. It was not sick, not registered and had never experienced drug treatment. The 30 test animals used in this research were divided into 6 groups, each consisting of 5 animals. Before being treated, they were acclimatized to the cage environment for 14 d and given daily food and drink.

Test the memory of experimental animals by the Y-Maze method

The group rats, consisting of the healthy control group, were given treatment and were without treatment for 25 d. Memory testing was then carried out using the Y-maze method [21] with slight modification. For the negative control, positive control, and treatment groups, mice were induced with 1.5 mg/KgBW of scopolamine for 10 d intraperitoneally. The memory testing was carried out using the Y-maze method. After the maze test, each treatment groups were given turmeric extract at a dose of 200 mg/KgBW, gotu kola extract at a dose of 200 mg/, and black pepper at a dose of 15 mg/KgBW. Variations in dose combinations were also carried out in this study, namely combining gotu kola, turmeric and black pepper extracts in various ratios of 50:50:50 (1), 50:25:25 (2), 25:50:25 (3), 25:25:25 (4), 25:50:50 (5), 50:50:25 (6), 25:25:50 (7), 25:12.5:50 (8), and 12.5:50:25 (9). Each extract and combination extracts were suspended with sodium CMC) administered once a day orally using a cannula. The administration was carried out until the 15th day. After giving each group to the test animals, memory was tested using the Y maze method. The three-armed Y-maze method was 50 cm long, 12 cm wide, and 25 cm high. The arms were separated symmetrically at 120ᴼ. The rat was placed at the end of one arm of the maze and allowed to freely explore the Y-maze throughout the experiment, which usually lasted 5-8 min. The behavioral testing was performed in a closed and quiet room. A stopwatch recorded the mouse's activity during the experiment. In this procedure, a healthy control group was used without treatment, a group used ginkgo biloba 120 mg/Kg BW as a positive control, and a group of mice used CMC sodium suspension as a negative control, which was treated for 15 d.

Glutaminase inhibitor activity

The inhibitory activity of the glutaminase enzyme was tested using a modification of the method of [22, 23] with slight modification. In this test, a combination of gotu kola extract, turmeric, and black pepper was used in a ratio of 2:4:1. The combination of extracts was then weighed as much as 100 mg and dissolved in 10 ml DMSO-buffer phosphate solvent (5% v/v). The sample solution was then made into a concentration series (10-1000 ug/ml) for further analysis. The reaction mixture (0.5 ml) consisted of 0.1 sample solution in 5% DMSO, 0.1 ml 0.1 M acetate buffer (pH 4.9), 0.1 ml enzyme solution (2.0 U/ml glutaminase in the same container, and 0.2 ml of substrate solution (0.04 mmol L-glutamine in the same buffer) were incubated at 370 for 30 min. The reaction was stopped by adding 0.5 ml of H2SO4 (0.5 M) solution. The precipitated protein was removed by centrifugation (3000 rpm, 10 min), and 0.2 ml of supernatant was added to 3.8 ml of distilled water. After that, 0.5 ml of Nessler's reagent was added, and absorbance was measured at 420 nm for 10 min.

The percent inhibition of the glutaminase enzyme was calculated using the formula:

………. [1]

………. [1]

Molecular docking simulation

The in silico activity of each extract of gotu kola, turmeric, and black pepper as candidates for treating brain injury was evaluated using molecular docking [24,25]. One of the target proteins in this research is glutaminase. Glutaminase protein was downloaded at the Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org/) with PDB ID 4O7D. Glutaminase is one of the enzymes involved in the mechanism of brain injury, so in this study, it was used as a target or receptor for searching for candidate chemical medicinal molecules from natural ingredients. There were 182 compounds consisting of 64 Curcuma longa L. compounds, 53 Piper nigrum L. compounds, and 65 Centella asiatica (L.) compounds. These compounds were obtained from several references that published chemical contents and were successfully identified in these three plants. The selected compounds are then confirmed for suitability for selected medicinal plants at https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/. The among of 182 compounds were evaluated for their biological activity by molecular docking using Autodock Tools software (Autodock vina_1_1_2). Using the Autodock vina_1_1_2 program, a grid was formed with dimensions (28.23×25.62×31.95) Å with grid box coordinates (x, y, z) 15.7 Å, 33.33 Å and-42.81 Å on the enzyme glutaminase. The parameters evaluated in this study include binding affinity energy, hydrogen interactions, and inhibition constants for each compound.

Molecular dynamic simulation

To evaluate the ligand-target interactions for the compounds with minimal binding energy (stronger binding energy) further, molecular dynamics (MD) was utilized. YASARA (YASARA Bioscience GmBH, Vienna, Austria) (Land et al., 2018) software was used to simulate molecular dynamics. Amber14 is applied in conjunction with periodic boundary conditions as a force field. The pH was kept at 7.4, and the temperature was adjusted to 310 K. To rebalance the system, TIP3P solvent and counterions (Na+, Cl-) were added. Ultimately, the simulation ran with a timestep of 0.25 fs for 100 ns. Every 25 ps, the following metrics are recorded and examined: radius of gyration, root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), and root mean square deviation (RMSD) [26].

Data analysis

Data analysis on in vitro testing from research results was analyzed using Microsoft Excel and statistically tested for normality, homogeneity, one-way ANOVA, and Kruskal-Wallis H tests using SPSS version 29.0. In silico evaluation, parameters include the orientation of the ligand structure, hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonds formed, and free energy values for each molecule's docking and molecular dynamic simulation.

RESULTS

Extraction and phytochemical screening

Gotu kola, turmeric, and black pepper are plant parts that can potentially have biological activity. In the study, gotu kola was used in herbaceous form (roots, stems, and leaves); in the turmeric plant, the rhizome was used, and the seeds were used in black pepper. Each gotu kola, turmeric, and black pepper powder were extracted by maceration using 70% ethanol as a solvent. Several references state that the maceration method for extracting gotu kola plants, turmeric rhizomes, and black pepper seeds effectively extracts the essential compounds [21, 22, 27]. The extraction solvent in 70% ethanol has also been proven to extract the compounds contained in these three plants. In general, triterpenoid compounds in the form of asiaticoside from the gotu kola plant are markers that have biological activity [28]. Likewise, turmeric rhizomes in curcuminoid compounds [14] and black pepper seeds in the form of piperine compounds also have the same potential to provide biological activity [29]. The maceration method and the selected extracting solvent attracted these potential compound candidates.

Based on the phytochemical screening carried out using colorimetric method, information was obtained that gotu kola extract was positive for containing triterpenoid compounds, turmeric extract was positive for containing curcuminoid compounds, and black pepper seed extract showed positive results for containing alkaloids (table 1). This identification is still suspected of asiaticoside in gotu kola extract, curcumin in turmeric extract, and piperine in black pepper extract. These three metabolite compounds are the major compounds contained in each extract and are used as markers in future research development.

The memorial test by Y-maze test

Memory testing was carried out using the Y-maze method. This test aims to measure the memory of experimental animals to find food quickly and efficiently. The mouse's memory was calculated from entering the Y-maze until it found the food in its right arm of the Y-maze. Memory testing was carried out on rat test animals consisting of 4 treatment groups. Group 1 (healthy control) rat test animals were only given food and drink, group 2 (negative control) rat test animals were given 0.5% NaCMC, group 3 (positive control) rat test animals were given ginkgo biloba, and group 4 (gotu kola leaf extract treatment), Group 5 (turmeric extract treatment), group 6 (black pepper extract treatment) and group 7 until group 15 (extract combination). Before testing to obtain initial data, an acclimatization process was carried out for seven days. After that, initial data was obtained from the rat's introduction stage in the maze, which aimed at learning and forming spatial memory. This stage was carried out and observed for 1×24 h.

Table 1: Yield (%) of extracts and their phytochemical profile

| Extract | Dry sample weight (g) | Extract weight (g) | Yield (%) | Organoleptic | Group compounds |

| Gotu Kola | 50 | 7 | 14 | The thick extract is blackish-green in colour, has a slightly bitter taste, and has a non-specific odour. | Terpenoid (+) |

| Turmeric rhizome | 50 | 11 | 22 | The thick extract is yellowish brown in colour, bitter in taste, and aromatic in smell | Curcuminoid (+) |

| Black pepper seed | 50 | 9.88 | 19.76 | Dry extract, black in color, spicy taste, and distinctive odor | Alkaloid (+) |

Note: (+) is a positive result.

Table 2: Profile of memory before and after treatment in experimental mice (seconds)

| Groups | Treatment | Observation (second) | ||

| Before treatment | Induction with scopolamine 1.5 mg/Kg BW | After treatment | ||

| 1 | Healthy control | 140.7±40.28 | - | - |

| 2 | Negative control (Na CMC) | 144.0±77.86 | 167.4±63.82 | 169.1±68.72* |

| 3 | Positive Control (ginkgo biloba) | 153.3±23.43 | 280.3±64.26 | 146.9±19.24* |

| 4 | Gotu kola extract (200 mg/KgBW) | 142.0±6.44 | 191.3±7.31 | 137.8±7.18* |

| 5 | Turmeric extract (200 mg/KgBW) | 145.2±88.27 | 198.3±34.84 | 133.0±23.70* |

| 6 | Black Pepper Extract (15 mg/KGBW) | 120.6±25.27 | 317.2±137.60 | 150.9±13.69* |

| 7 | Combination 1 (50:50:50) | 178.7±37.31 | 203.9±51.27 | 142.3±23.19* |

| 8 | Combination 2 (50:25:25) | 153.9±30.63 | 192.2±59.16 | 149.8±44.08* |

| 9 | Combination 3 (25:50:25) | 169.9±78.36 | 189.8±83.63 | 144.8±9.03* |

| 10 | Combination 4 (25:25:25) | 196.6±64.46 | 217.3±19.43 | 181.3±72.78* |

| 11 | Combination 5 (25:50:50) | 157.7±51.34 | 182.0±76.98 | 133.9±29.51* |

| 12 | Combination 6 (50:50:25) | 167.6±10.17 | 213.4±60.91 | 155.9±19.54* |

| 13 | Combination 7 (25:25:50) | 179.2±22.95 | 268.7±62.76 | 148.7±45.64* |

| 14 | Combination 8 (25:12,5:50) | 155.7±29.50 | 254.9±69.28 | 143.1±40.95* |

| 15 | Combination 9 (12.5:50:25) | 163.3±23.14 | 248.4±81.42 | 153.9±14.11* |

Note: *The statistical analysis of samples were shows that the significant different among of samples (p<0.05, n=3, mean±SD).

The experimental data in table 2 shows changes in mice's memory before and after treatment, induced by Scopolamine and by treatment with the extract. Induction with Scopolamine showed a decrease in memory, observed in the longer it took for mice to leave the Y-maze, namely 169.1±68.72 seconds, compared to before induction, namely 144.0±77.86 sec. Similar things were experienced in all groups after being induced with Scopolamine compared with experimental data before induction. The decrease in memory of mice using the Y-maze method after scopolamine induction was caused by Scopolamine quickly crossing the blood-brain barrier, causing the induction of muscarinic activity by depleting acetylcholine, which caused memory loss, oxidative stress, and causing a decrease in catalase activity in the hippocampus compared to initial data [30].

Data from the treatment of gotu kola extract, turmeric, and black pepper showed an increase in the memory of the experimental animals, which was observed by decreasing the travel time (in minutes) for the mice to reach their food in the Y-maze. Administration of gotu kola extract suspension at a dose of 200 mg/Kg BW, turmeric extract at a dose of 200 mg/Kg BW, and black pepper extract at a dose of 15 mg/Kg BW were able to improve memory as evaluated using the Y-maze method (fig. 2). The improvement in memory after administration of the extract increased significantly P<0.05 from the negative control group after scopolamine induction. Improved memory from each extract showed results that were not significantly different (p>0.05) from the positive control treatment group, ginkgo biloba (200 mg/Kg BW). This means that each extract can improve memory in mice after administration for 15 d. In this study, ginkgo biloba was used as a positive control because ginkgo biloba is one of the main compounds isolated from natural plants and works by activating the signaling pathway connected to erythroid 2 factor 2 (Nrf2), which is known as the primary molecular mechanism in protection against oxidative stress and deletion of its gene expression inhibits neuron regeneration by stimulating phase II genes through Kelch-like ECH associated protein-1 [31].

Fig. 1: Memory profile of test animals (mice) from each treatment by Y-maze method. Note: *The statistical analysis of samples were shows that the significant different among of samples (p<0.05, n=3, mean±SD)

In this study, an evaluation of memory enhancement activity was also conducted using several comparisons of gotu kola, turmeric, and black pepper extract combinations. Dose variations were carried out with different comparisons according to table 2. The evaluation results showed a significant increase in memory from the combination used and compared with the results of memory enhancement using a single extract and positive control. The combination of extracts 1 and 8 increased memory by>50% (fig. 1) and was followed by a combination dose of extract 5 with a percentage increase of 46.8%. The combination of extracts at other doses did not show significant results in increasing memory, namely<40% (post-hoc test, p>0.05, n=3). When observed from the increase in memory ability in test animals, the combination of doses 1 and 8 did not show a significant increase in memory (Post-hoc test, p>0.05, n=3). However, when compared with the percentage of memory increase between the combination doses 1 and 8 (>50%) and combination 5 (>45%) against the positive control, ginkgo biloba (<40%), significantly different results were obtained (Post-hoc test, p>0.05, n=3). Therefore, the administration of extracts with combinations of 1, 5, and 8, namely gotu kola, turmeric, and black pepper extracts, can be selected for further research.

Glutaminase inhibitor profile

Based on preliminary tests of the activity of gotu cola extract, skin, and black pepper as a memory enhancer, it was shown that combining the three natural extracts was proven effective in improving memory. The best combination uses a ratio of gotu kola, turmeric, and black pepper extract, namely 50:50:50 (combination 1), 25:50:50 (combination 5), and 25, 12.5, and 50 (combination 8). These combinations of the extracts were then applied to the in vitro glutaminase inhibition test.

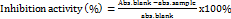

Determination of inhibitory bioactivity of the combination extract of gotu kola, turmeric, and black pepper against glutaminase showed potent activity. Combinations with a ratio of 50:50:50 (combination 1), 25:50:50 (combination 5), and 25, 12.5, and 50 (combination 8) had IC50 values of 44.63±11.84, 57.94±4.01, and 56.29±6.18, respectively (fig. 2). According to Batubara et al. (2010), an IC50 value<100 µg/ml indicates strong inhibitory potential, an IC50 value of 100-450 µg/ml indicates moderate inhibitory potential, and an IC50 value of 450-700 µg/ml indicates weak inhibitory potential [32]. From the results of the tests, an IC50 value of<100 µg/ml was obtained, indicating potent activity. The statistical analysis results of the combination of extracts applied to the glutaminase enzyme showed significantly different IC50 values between samples. The combination of extract 1, namely at a ratio of 50:50:50, gave the most potent and most significant inhibitory effect with combinations 5 and 8 (post-hoc test, p<0.05, n=3).

In silico activity of combination extract by molecular docking

The in vitro activity of the combination of Gotu kola, turmeric, and black pepper extracts as a memory enhancer correlates with its bioactivity in inhibiting glutaminase. The prediction of active compounds from each extract that provide pharmacological activity for developing brain injury treatment needs to be made. This study also evaluated in silico activity through molecular docking to predict the interaction of active compounds identified in each extract against amino acid residues in the target protein. The target protein used was glutaminase protein with PDB id 4O7D. Each identified compound from gotu kola, turmeric, and black pepper extracts obtained from secondary data from searches in several sources was then monitored for interaction. Citric acid is one of the compounds used as a native ligand that has the potential to interact with the target protein. The native ligand pocket was reduced to obtain the pocket where the selected compounds interacted from each extract so that the visualization of the interaction between the identified compounds and the native ligand could be compared. The results of the native ligand redocking analysis against the target protein obtained an RMSD value of 1.5 A. The RMSD value is stated to have good validity, so the ligand copy interaction pocket size can be used to dock compounds from each extract. The smaller RMSD value indicates that the interaction between the compound and the target protein is getting closer to the interaction between the native ligand and the target protein. Visualization of the docking method validation is shown in fig. 3.

The test compounds used in the study were 64 Curcuma longa L. compounds, 53 Piper nigrum L. compounds, and 65 Centella asiatica (L.) Urb. Compounds obtained from the results of literature studies. The observed free binding energy is the interaction energy of the ligand bond to the glutaminase enzyme. The results of the docking of the test compound molecules generally show interactions with the active site of the receptor, which are characterized by negative free binding energy values, but only a few compounds from Curcuma longa L. and Centella asiatica (L.) Urb. This showed the best results in inhibiting the target protein (table 3-5).

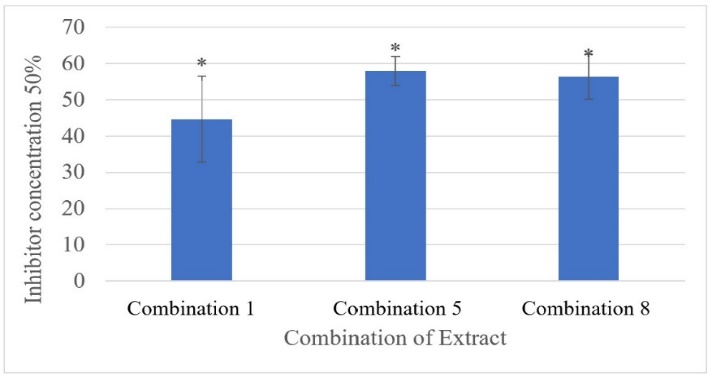

Based on the results of the in silico activity evaluation of identified compounds from gotu kola extract, it is shown that several potential compounds have the best interaction with the target protein of the glutaminase enzyme. Centellasaponin C, asiaticoside, and its derivatives, including asiaticoside B, D, E, and G, and Quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside compounds. The interaction of these compounds has a more negative binding affinity value (range -8 to -10 kcal/mol) compared to the native ligand 5-oxo-L-norleucine (-5.4 kcal/mol).

Table 3: Free energy value of binding, ligand and receptor interaction, and residues bound to glutaminase enzyme in gotu kola (Centella asiatica (L.) Urb) compound

| No. | Compounds | Free binding affinity (kcal/mol) | Amino acid residue (H-Bond) |

| NL | 5-OXO-L-NORLEUCINE | -5,4 | ASN170, ASN117, GLN67, VAL266 |

| 1 | Asiaticoside | -8,7 | GLU163, ASN170, TYR248, LYS289 |

| 2 | Asiaticin | -6,8 | ARG496 |

| 3 | Madekassosida | -8,6 | ASN101, ARG99, ASP249, LYS289 |

| 4 | Asam Asiatic | -9,3 | - |

| 5 | Isoasiatic acid | -9,2 | - |

| 6 | 2α,3β,20,23-Tetrahydroxy-urs-28-ioc acid | -8,8 | - |

| 7 | Centella-sapogenol A | -9,6 | - |

| 8 | Asam madasiatic | -9,7 | - |

| 9 | Centellin | -5,4 | ASN170, SER166 |

| 10 | 1,3,7,9-Tetrahydroxy-6H-dibenzo[b,d]pyran-6-one | -8,0 | TYR248, LYS71 |

| 11 | Meso-inositol | -5,9 | GLN67, SER68, TYR196, ASN170 |

| 12 | Amygdalin | -8,5 | SER166, ASN170, GLU163, ASN117 |

| 13 | Brahmic acid | -9,6 | - |

| 14 | Centellasaponin B | -9,3 | - |

| 15 | Centellasaponin C | -9,1* | GLN67, ASN170, GLU168, TYR248 |

| 16 | Asiaticoside C | -8,8 | PHE100, GLU163, ASN117, ARG169, ASP249, ARG99 |

| 17 | Asiaticoside D | -9,2* | ASP249, ASN117, ASN101 |

| 18 | Asiaticoside E | -8,9* | VAL266, ASN170, GLU163, TYR31 |

| 19 | Asiaticoside F | -8,2 | VAL266, ASN170, GLU163, TYR31 |

| 20 | Isoasiaticoside | -7,8 | LEU287, MET290 |

| 21 | Asiaticoside G8 | -8,5* | ASP30, TYR31, LYS289, GLN67, ASN170 |

| 22 | Centelloside E | -8,8 | ARG99, ASP249, GLU163 |

| 23 | Asiaticoside B | -8,3* | MET290, VAL266, SER68, LYS71, ASN117, GLU163, ASP288, LYS289 |

| 24 | Centellasaponin A | -7,7 | LYS289, ASN117, ASO249, LYS27 |

| 25 | Centellasaponin D | -8,6 | PHE100, GLU163, TYR196, ASN117 |

| 26 | Chebuloside II | -9,0 | GLU163, LYS27 |

| 27 | Centelloside D | -8,4 | ASP249, MET290, ASP288, ASN101 |

| 28 | Castasterone | -7,8 | ASN117, LYS27 |

| 29 | Castillicetin | -9,1 | GLU163, ASP249, SER68 |

| 30 | Castilliferol | -9,2 | SER68, ASP249 |

| 31 | Polyacetylene I | -5,2 | ASN170, ARG169 |

| 32 | Polyacetylene II | -6,1 | VAL266, SER68, ASN170 |

| 33 | Polyacetylene III | -5,5 | TYR248 |

| 34 | Polyacetylene IV | -5,8 | SER68 |

| 35 | Polyacetylene V | -5,3 | MET290 |

| 36 | Centellicin | -5,3 | TYR248 |

| 37 | Glyceryl 2-phospho-1caprate | -5,8 | TYR196, ASN117 |

| 38 | Cadiyenol | -6,3 | LYS27, ASN101, VAL266, SER68 |

| 39 | Irbic acid (3,5-O-diceffeoyl-4-O-malonil quinic acid) | -8,0 | LYS289, ASP288, LYS71, TYR196, TYR248, ASN101, ASN117, SER166 |

| 40 | 11-Oxoheneicosanyl cyclohexane | -5,1 | SER68, VAL266 |

| 41 | Apigenin | -7,8 | ASN117, MET290, GLN67 |

| 42 | Luteolin | -7,9 | GLU163, ASN170, ARG169, ASN101, SER68 |

| 43 | Myristicin | -5,7 | ASN117 |

| 44 | 7-methoxycoumarin | -5,8 | ASN117, SER68 |

| 45 | Umbelliferone | -5,9 | LYS71, ASN117 |

| 46 | p-coumaric acid | -5,7 | SER68, GLN67, MET290, TYR31 |

| 47 | Ferulic acid | -5,9 | TYR31, MET290, SER68 |

| 48 | Caffeic acid | -5,7 | ASN101, MET290, TYR31, GLN67 |

| 49 | Kaempferol | -7,8 | GLN67, SER68, MET290 |

| 50 | Quercetin | -7,9 | ASN101, GLN67 |

| 51 | Chlorogenic acid | -8,0 | MET290, ASN117, GLN67, SER68, ASN170 |

| 52 | Kaempferol-3-arabinoside | -8,4 | GLU163, GLN67, TYR31, SER166 |

| 53 | β-sitosterol | -7,8 | - |

| 54 | Kaempferol-7-rhamnoside | -8,6 | ASN117 |

| 55 | Kaempferol-3-O-rhamnoside | -8,6 | SER68, ASN101, ASN117, SER166 |

| 56 | Quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside* | -9,0* | SER166, ASN170, GLU163, ASN117, SER68, ARG169 |

| 57 | Kaempferol-5-glucoside | -8,2 | ASN117, PHE100, GLY291, LYS289 |

| 58 | Kaempferol-3-O-glucoside | -8,1 | PHE100 |

| 59 | Betulinic acid | -9,3 | ASN117 |

| 60 | Methyl asiatate | -8,9 | - |

| 61 | Isothankunic acid | -9,0 | - |

| 62 | Terminolic acid | -9,1 | LYS289, ASP249, SER68 |

| 63 | β-carotene | -5,9 | - |

| 64 | Rutin | -8,5 | MET290, PHE100, ASN117, ASN170, LYS27 |

| 65 | Scheffuroside B | -8,8 | PHE100, LYS289, ASP249, ARG99, ASN117, ASN170, GLU163 |

Note: *The selected compounds that have the best interaction in inhibiting the target protein based on evaluation of binding affinity and hydrogen interactions with amino acid residues.

Table 4: Free energy value of binding, ligand and receptor interaction, and residues bound to glutaminase enzyme in Turmeric extract (Curcuma longa) compounds

| No. | Compounds | Free binding affinity (kcal/mol) | Amino acid residue (H-Bond) |

| NL | 5-OXO-L-NORLEUCINE | -5,4 | ASN170, ASN117, GLN67, VAL266 |

| 1 | Curcumin | -7,6* | ASN101, LYS71, ASN170 |

| 2 | Dimethoxy curcumin | -7,7 | ASP30, TYR31 |

| 3 | Bisdimethoxy curcumin | -7,6* | LYS27, GLN67, ASP30 |

| 4 | Calebin A | -6,0 | ASP30, LYS27, GLN67 |

| 5 | 1,7-bis(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,4,6-heptatriena-3-on | -7,9 | LYS27 |

| 6 | 1-hydroxy-1,7-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-3-methoxyphenyl)-6-heptena-3,5-dion | -7,8* | LVS27, TYR31, GLN67 |

| 7 | 1,7-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-1-heptena-3,5-dion | -7,7 | ASP30, LYS27, MET290 |

| 8 | 1,7-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-1,4,6-heptatrien-3-on | -7,6 | TYR31, LYS27 |

| 9 | 1,5-bis(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,4-pentadien-3-on | -7,5* | ASN170, ASN117, LYS71, SER68, GLN67, ASN101, TYR248, VAL266 |

| 10 | Curcumenon | -6,8 | ASN101, LYS71 |

| 11 | Dehydrocurdion | -6,7 | SER68, ASN117 |

| 12 | Germacrone 4,5-Epoxide | -6,5 | - |

| 13 | Bisabola-3,10-diena-2-on | -6,2 | - |

| 14 | Α-turmeron | -7,9* | ASN117, ASN170 |

| 15 | Bisacumol | -6,4 | ASP492 |

| 16 | Bisacuron | -6,4 | LYS71, GLU163 |

| 17 | Curcumenol | -6,4 | ASN117 |

| 18 | Isoprocurcumenol | -6,9 | TYR248, GLU163 |

| 19 | Zedoaronediol | -7,0 | ASN117 |

| 20 | Procurcumenol | -7,0 | ASN117, TYR196 |

| 21 | Epiprocurcumenol | -7,0 | ASN117, LYS71 |

| 22 | Germacron-13-al | -6,6 | SER68 |

| 23 | 4-hydroxy-bisabola-2,10-diena-9-on | -6,3 | - |

| 24 | 4,5-di hydroxy bisabola-2,10-diena | -6.7 | ASN117, TYR196 |

| 25 | 4-methoxy-5-hydroxy bisabola-2,10-diena-9-on | -6,5 | ASN117 |

| 26 | 2,5-di hydroxy ibisabola-3,10-diena | -6,3 | - |

| 27 | Procurcumadiol | -7,4 | LYS71, ASN117 |

| 28 | 1,3,5,11-Bisabolatetraene | -5,9 | - |

| 29 | 3-Hydroxy-1,10-bisaboladien-9-one | -6,2 | ASN117, LYS71 |

| 30 | ar-Turmerone | -6,4 | SER68 |

| 31 | Curlone | -6,4 | SER68 |

| 32 | Bisacurone A | -6,6 | TYR196, LYS71 |

| 33 | Bisacurone B | -6,4 | ASN117 |

| 34 | Bisacurone C | -6,7 | SER68 |

| 35 | Bisacurone epoxide | -6,8 | TYR31, LYS71 |

| 36 | Turmeronol B | -6,2 | ASN117 |

| 37 | Dihydrocurcumenone | -6,7 | ASN101, SER68 |

| 38 | Isospathulenol | -7,1 | VAL266 |

| 39 | Isozedoarondiol | -7,3 | TYR196 |

| 40 | α-Phellandrene | -4,5 | - |

| 41 | Sabinene | -4,8 | - |

| 42 | Geraniol | -4,9 | ASN117 |

| 43 | Bergamotene | -5,7 | - |

| 44 | p-Cymene | -5,1 | - |

| 45 | Eucalyptol | -4,8 | ASN117 |

| 46 | Terpinolene | -5,0 | - |

| 47 | β Thujene | -4,5 | - |

| 48 | Terpineol | -5,3 | GLU163, TYR31, GLN67 |

| 49 | Camphene | -4,5 | - |

| 50 | O-Cymene | -5,1 | - |

| 51 | Cis-α-Bisabolene | -6,2 | - |

| 52 | α-Curcumene | -6,2 | - |

| 53 | γ-Himachelene | -6,5 | - |

| 54 | α-Fernesene | -4,8 | - |

| 55 | Alpha-terpinene | -4,9 | - |

| 56 | β-Pinene | -4,6 | - |

| 57 | β-Myrcene | -4,5 | - |

| 58 | 2-Carene | -4,6 | - |

| 59 | 3-Carene | -5,0 | - |

| 60 | 4-Carene | -4,6 | - |

| 61 | Zingiberene | -5,4 | - |

| 62 | β-Sesquiphellandrene | -6,1 | - |

| 63 | p-Menthatriene | -5,0 | - |

| 64 | Bisabolene | -6,1 | - |

Note: *The selected compounds that have the best interaction in inhibiting the target protein based on evaluation of binding affinity and hydrogen interactions with amino acid residues.

Table 5: Free energy value of binding, ligand and receptor interaction, and residues bound to glutaminase enzyme in black pepper (Piper nigrum) compounds

| No. | Compounds | Free binding affinity (kcal/mol) | Amino acid residue (H-Bond) |

| NL | 5-OXO-L-NORLEUCINE | -5,4 | ASN170, ASN117, GLN67, VAL266 |

| 1 | Piperin | -7,2 | ASP249 |

| 2 | Alpha-Thujene | -4,6 | - |

| 3 | α-Pinene | -4,6 | - |

| 4 | Camphene | -4,5 | - |

| 5 | Sabinene | -4,8 | - |

| 6 | β-Pinene | -4,6 | - |

| 7 | β-Myrcene | -4,5 | - |

| 8 | α-Phellandrene | -4,5 | - |

| 9 | Delta-3-carene | -5,0 | - |

| 10 | Alpha-terpinene | -4,9 | - |

| 11 | p-Cymene | -5,1 | - |

| 12 | Limonene | -5,0 | - |

| 13 | 1,3,6-Octatriene, 3,7-dimethyl-, (E)-(CAS) Beta Ocimene | -4,7 | - |

| 14 | Gamma-terpinene | -5,1 | - |

| 15 | Alpha-terpinolene | -5,0 | - |

| 16 | Linalool | -4,6 | TYR231, ARG215 |

| 17 | Delta-elemene | -5,8 | - |

| 18 | Alpha-cubenene | -5,9 | - |

| 19 | Alpha-copaene | -5,9 | - |

| 20 | Beta-elemene | -6,0 | - |

| 21 | Alpha-gurjunene | -6,0 | - |

| 22 | Trans-cryophyellene | -6,1 | - |

| 23 | Alpha-humulene | -6,4 | - |

| 24 | Germacrene-D | -6,3 | - |

| 25 | Beta-selinene | -6,2 | - |

| 26 | Alpha-selinene | -6,3 | - |

| 27 | Delta-cadinene | -6,1 | - |

| 28 | (-)-Caryophyllene oxide | -6,2 | ASN117 |

| 29 | Spathulenol | -6,5 | LYS71 |

| 30 | Eugenol | -5,4* | ASN117, ASN170 |

| 31 | Gingerol | -6,7 | TYR512, ARG496, LYS477 |

| 32 | Zingerol | -5,6 | SER166, SER68, LYS71 |

| 33 | Carvacrol | -5,4 | ASN101 |

| 34 | Thymoquinone | -5,7 | TYR248, ASN101 |

| 35 | Cinnamaldehyde | -5,1 | SER68 |

| 36 | Cinnamic acid | -5,5* | GLN67, VAL266 |

| 37 | β-Caryophyllene | -6,1 | - |

| 38 | Calcone | -6,8 | TYR248 |

| 39 | Chloroquine | -6,1 | - |

| 40 | Hydroxychloroquine | -6,2 | TYR196 |

| 41 | Anethole | -5,0 | - |

| 42 | Fenchone | -5,0 | ASN170 |

| 43 | Metyl chavicol | -4,7 | - |

| 44 | Cuminaldehyde | -5,3 | VAL266 |

| 45 | Baricitinib | -8,0* | SER166, ASN101, SER68, ASN117,ASN170, LYS71 |

| 46 | Chavicine | -7,2 | LYS71 |

| 47 | Isochavicine | -7,1 | - |

| 48 | Isopiperine | -7,1 | VAL266 |

| 49 | Piperidine | -3,2 | - |

| 50 | Piperic acid | -6,4* | GLN67, ASN170 |

| 51 | CMPD-1 | -6,4* | ASN170, SER68, GLN67 |

| 52 | CMPD-8 | -5,8 | TSER68, GLN67, VAL266 |

| 53 | Adenosine 5’-monophosphate | -7,2 | ASN117, GLN67, TYR196, ASN170 |

Note: *The selected compounds that have the best interaction in inhibiting the target protein based on evaluation of binding affinity and hydrogen interactions with amino acid residues.

Fig. 2: The anti-glutaminase activity of combination extract. Test data showed that there was a significant difference in the inhibitory activity against glutaminase of each extract combination (p<0.05, n=3, mean±SD)

Fig. 3: Docking visualization of native ligand. (a) Yellow represents the copy ligand, and (b) gray represents the native ligand

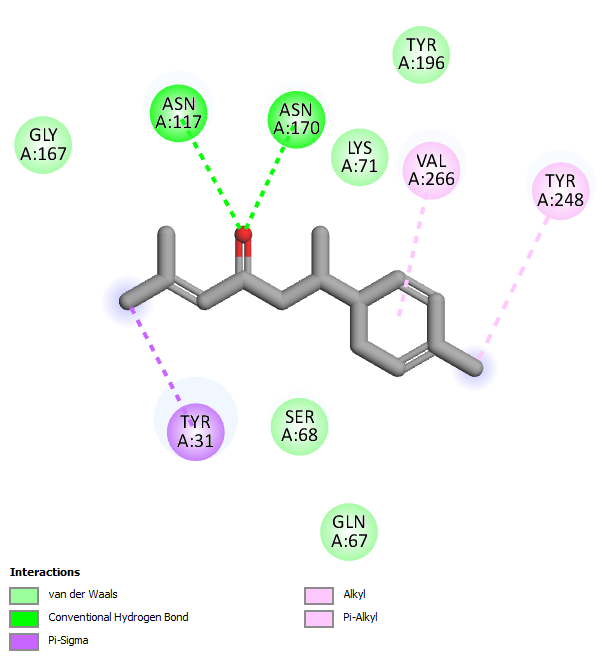

The hydroxyl group located on the aromatic ring of Centellasaponin and asiaticoside derivates shows hydrogen interactions at the amino acid residues ASN170, ASN117, GLN67, and VAL266, depending on the position of each compound (fig. 4).

Fig. 4: Moleculer docking visualization of glutaminase target protein against selected compounds from gotu kola extract

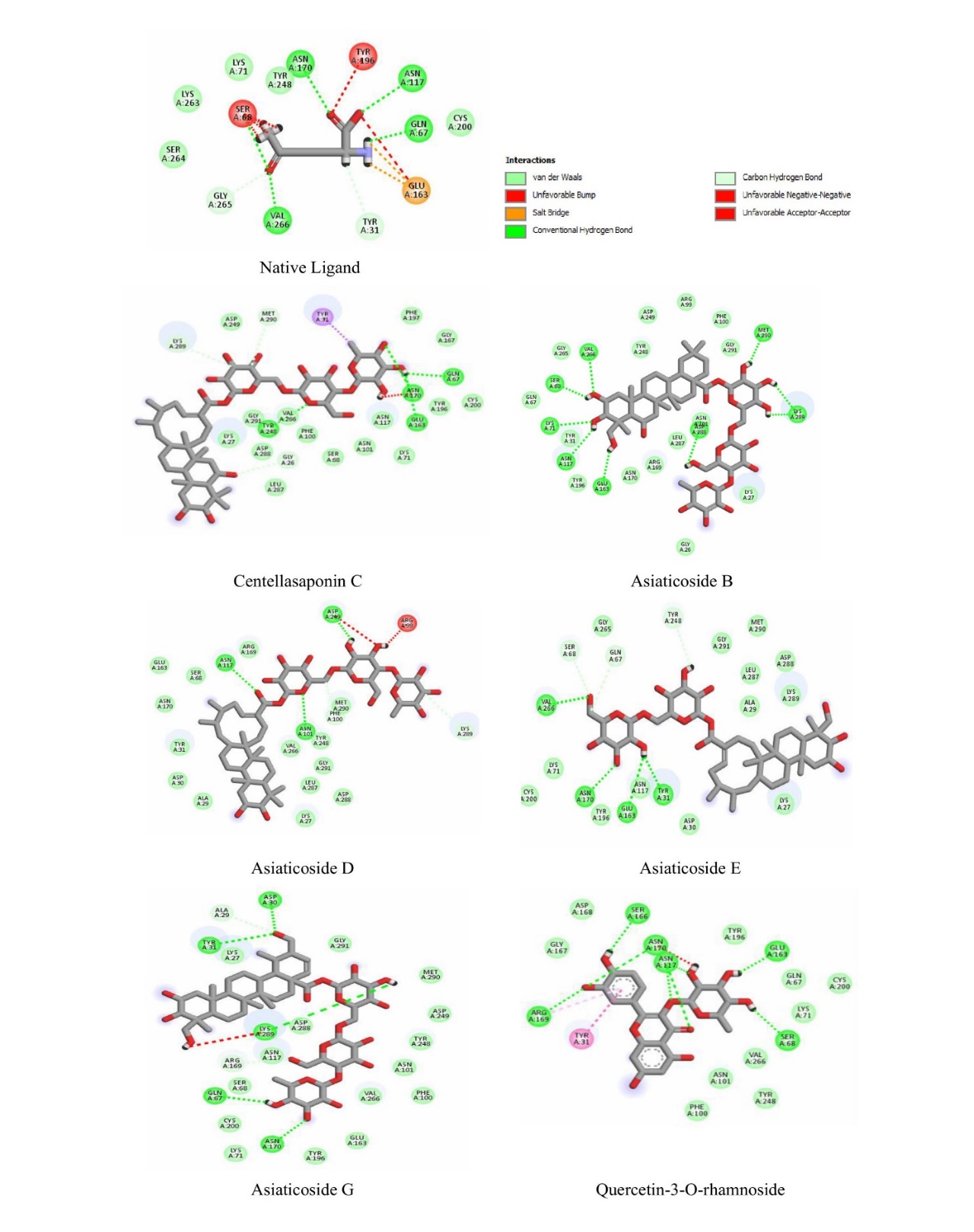

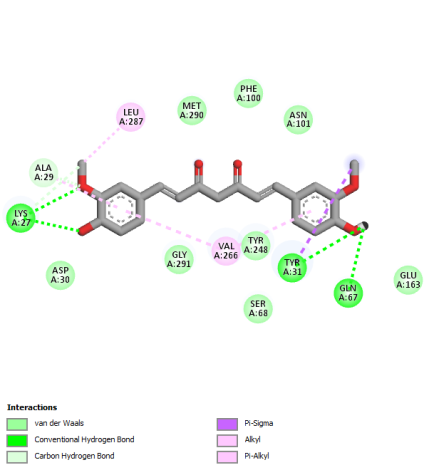

Compounds from turmeric extract were also evaluated for their in silico activity by molecular docking. It was confirmed that 64 secondary metabolite compounds were identified in turmeric rhizome extract based on a search in internationally reputable journals, and curcumin compounds are markers in this plant. The results of evaluating the interaction of compounds from turmeric extract were reported to have general interactions with the target protein glutaminase. However, 5 selected compounds were identified that had the most negative binding affinity values and interactions with key amino acids that were similar to the native ligand. The five compounds were curcumin, Bisdimethoxy curcumin, alpha-turmeron, 1-hydroxy-1,7-bis (4-hydroxyphenyl)-3-methoxyphenyl)-6-heptene-3,5-dione, and 1,5-bis (4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,4-pentadien-3-one with binding affinity values of each compound>7 kcal/mol (table 4). The binding affinity of each compound was evaluated to be more negative than the native ligand on the glutaminase protein.

|

|

| Curcumin | Bisdimethoxy curcumin |

|

|

| Alpha Turmeron | 1-hydroxy-1,7-bis (4-hydroxyphenyl)-3-methoxyphenyl)-6-heptene-3,5-dione |

|

|

| 1,5-bis (4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,4-pentadien-3-one |

Fig. 5: Moleculer docking visualization of glutaminase target protein against selected compounds from turmeric extract

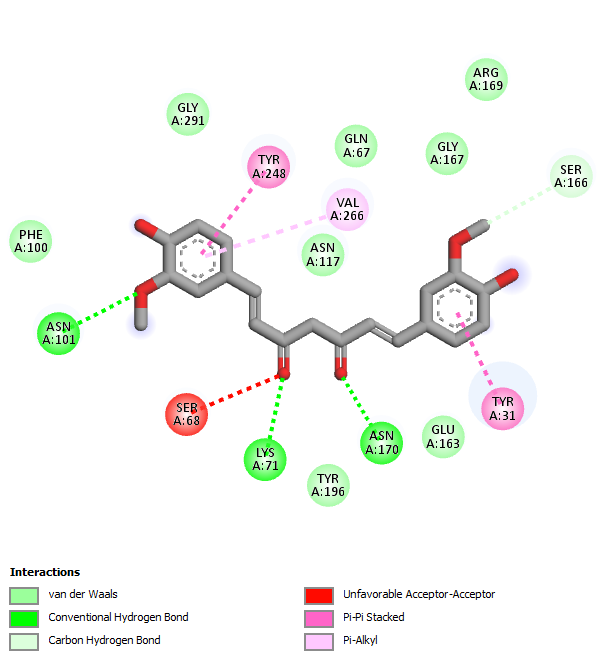

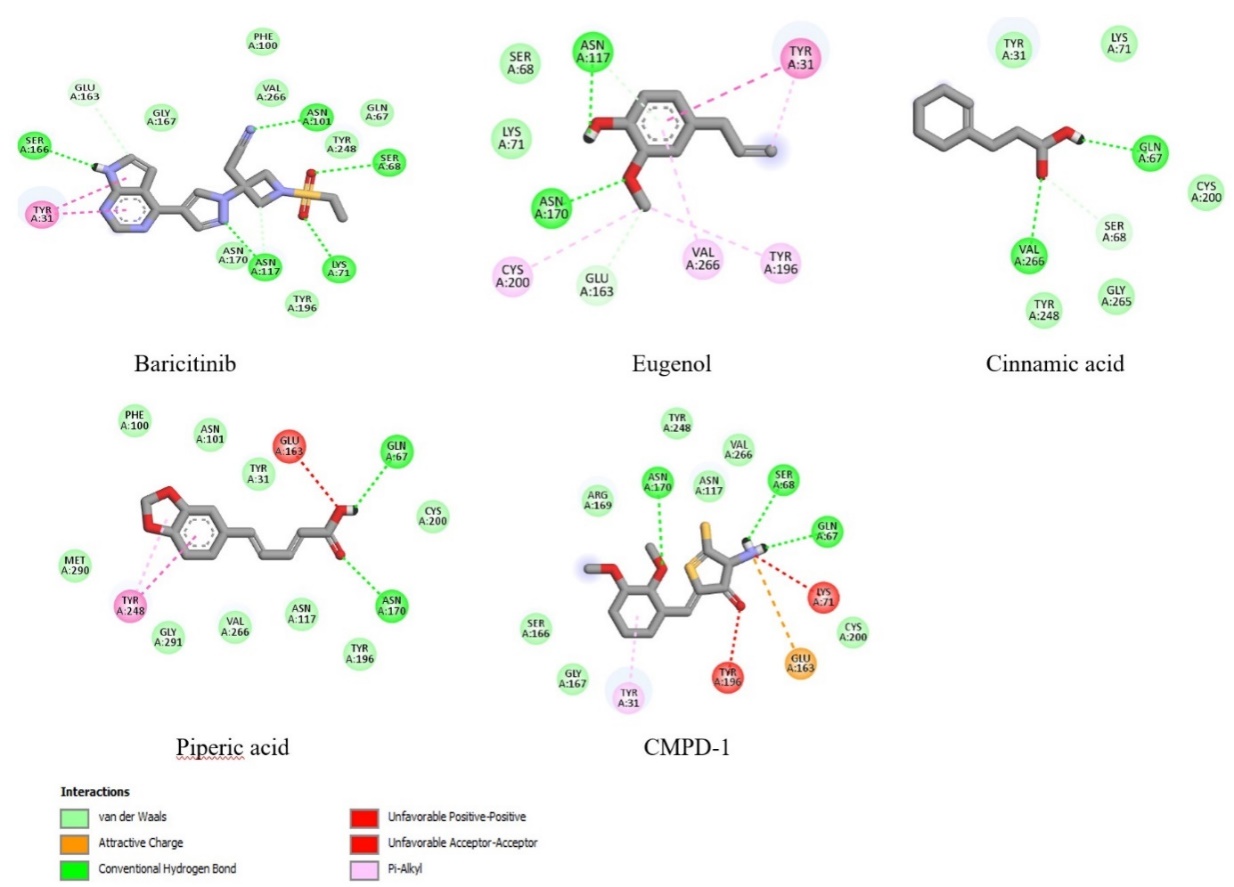

The visualization results in fig. 5 show that the carbonyl group in the curcumin compound plays a role in interacting hydrogen with the key amino acid ASN170. While in the compounds Bisdimethoxy curcumin and 1-hydroxy-1,7-bis (4-hydroxyphenyl)-3-methoxyphenyl)-6-heptene-3,5-dione, there is a hydroxyl group on the aromatic ring that interacts hydrogen with the amino acid GLN67. At the same time, the carbonyl group (C = O) in the compound 1,5-bis (4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,4-pentadien-3-one and alpha-turmeron interacts hydrogen with the amino acids ASN170, ASN117, and GLN67, and the hydroxyl group (OH) on the aromatic ring of the compound interacts with the amino acid VAL266. The compound's interaction with the key amino acids ASN170, ASN117, GLN67, and VAL266 is predicted to inhibit the target protein glutaminase. Meanwhile, black pepper extract showed 6 compounds inhibiting glutaminase in silico. Compounds like Baricitinib, Eugenol, Cinnamic acid, piperic acid, and CMPD-1 have negative binding affinity values (>6 kcal/mol) and even exceed native ligands (fig. 6 and table 5).

Fig. 6: Molecular docking visualization of glutaminase target protein against selected compounds from black pepper extract

Molecular dynamic simulation of extract compounds

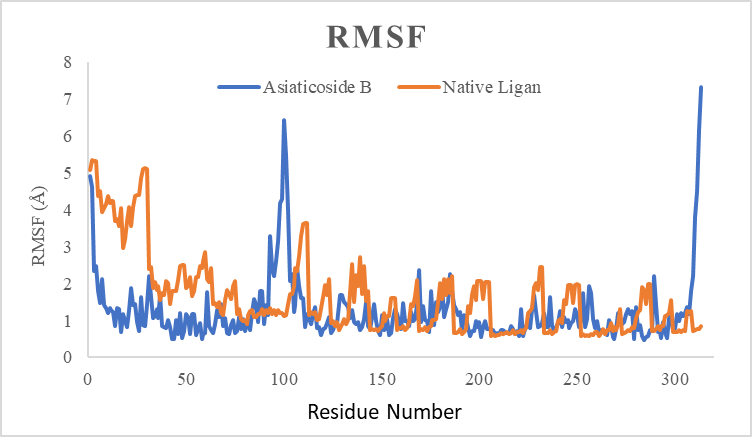

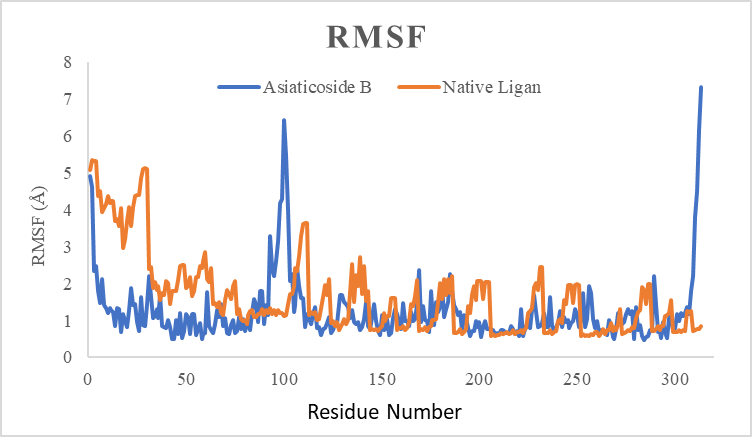

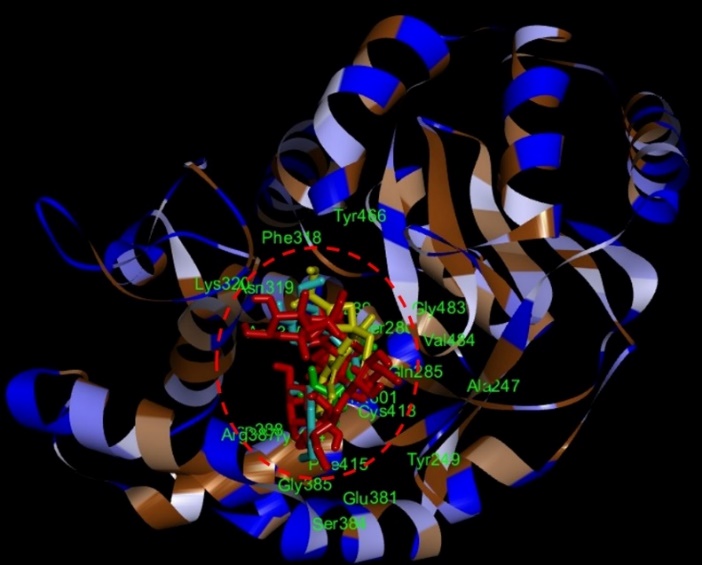

In this study, one of the most active compounds was selected in silico from each extract. In the gotu kola extract, the molecular dynamic evaluation used the compound Asiaticoside B, and the compound 1,5-bis (4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,4-pentadien-3-one in the turmeric compound and Barictinib in the black pepper extract compound. The three compounds were evaluated using RMSD, the Radius of gyration, and RMSF. The results of the molecular dynamic evaluation of each compound against the target protein glutaminase compared to the native ligand can be seen in fig. 7-9.

|

|

| A | B |

|

|

| C |

Fig. 7: Graph of RMSF profile during molecular dynamics simulation of 4O7D-Native ligand (orange line) and 4O7D-5-OXO-L-NORLEUCINE (blue line) complexes during 100 NM sampling time of the molecular dynamics simulation. A) Asiaticoside B, (B) 1,5-bis (4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,4-pentadien-3-one, and (C) Baricitinib

Of the three compounds, the 4O7D-Asiaticoside B complex showed the most stable binding complex when compared to the 1,5-bis (4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,4-pentadien-3-one and Baricitinib compounds. The 4O7D-Asiaticoside B binding complex showed an RMSD value of 2A ranging from 0 to 60 NM (fig. 7). It began to increase in the range of 3A to 90 NM and decreased until 100 NM. The average RMSD value of the 4O7D-Asiaticoside B complex was<3 Å. While the 1,5-bis (4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,4-pentadien-3-one and Baricitinib compounds showed RMSD values >3 Å starting at 60 NM and started to decrease until 100 NM. RMSD value <3Å indicates that the protein is stable and does not experience significant conformational changes.

|

|

| A | B |

|

|

| C |

Fig. 8: Graph of RMSF profile during molecular dynamics simulation of 4O7D-Native ligand (orange line) and 4O7D-5-OXO-L-NORLEUCINE (blue line) complexes during 100 NM sampling time of the molecular dynamics simulation. A) Asiaticoside B, (B) 1,5-bis (4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,4-pentadien-3-one, and (C) Baricitinib

|

|

| A | B |

|

|

| C |

Fig. 9: The graph of Radius of Gyration profile during molecular dynamics simulation of 4O7D-Native ligand (orange line) and 4O7D-5-OXO-L-NORLEUCINE (blue line) complexes during 100 NM sampling time of the molecular dynamics simulation. A) Asiaticoside B, (B) 1,5-bis (4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,4-pentadien-3-one, and (C) Baricitinib

The visualization results of the RMSF value in the protein-ligand complex in each compound (fig. 8) tend not to experience significant fluctuations. Although there are fluctuations in the number of amino acids in sequence 100, they stabilize again until molecular dynamics occur. The average on the active site residue of the protein tends not to experience a significant increase in RMSF during the simulation process. The active site can maintain the structure because it has hydrogen bonds between residues ASN117, ASN170, GLN56, and VAL266, which can stabilize the position of the structure. Based on the visualization results of the RMSF value in fig. 10, it can be concluded that the active site residue is in a stable position.

Fig. 9 shows the profile of changes in the protein radius of gyration during molecular dynamics simulations of complexes with compound and native ligands. Changes in the size of 5A46 with ligands during molecular dynamics simulations did not experience significant changes in either the protein-ligand complex Asiaticosid B, 1,5-bis (4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,4-pentadien-3-one, and Baricitinib. Although at 80 NM, there was an increase in the radius of gyration, it returned to the appropriate size at 100 NM. This increase did not occur significantly, showing that the protein-ligand complex resulting from docking is quite stable. This can also be adjusted to the evaluation results of RMSD and RMSF values that did not experience significant changes.

DISCUSSION

This research examines the effects of gotu kola, turmeric, and black pepper extracts as candidates in treating brain injury, which is carried out in several stages, starting from the extraction process, phytochemical screening, and in vitro and silico tests. Secondary metabolite compounds such as asiaticoside derivatives from gotu kola, curcumin derivatives from turmeric, and piperine derivatives from black pepper can potentially treat brain injury. Several parameters used include the effects of extracts and combinations of extracts on improving memory and inhibiting glutaminase, which triggers an increase in neurotransmitters in the form of glutamate after brain injury.

Gotu Kola extract can stimulate memory, which is thought to be caused by the triterpenoid saponin compound (asiaticoside) contained therein. This compound is known to repair damaged blood vessels, thereby improving blood circulation to the brain. It is also able to regenerate cells and heal wounds. This process is initiated by inhibiting Na+K+ATPase in the brain, which depolarises calcium in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Depolarization of the RE causes continuous secretion of acetylcholine, resulting in stable central cholinergic neurotransmission and increased memory [12, 33, 34]. Turmeric extract is thought to contain curcuminoids essential in improving memory. Curcuminoids can work by reducing oxidative stress in the hippocampus, and curcumin shows its antioxidant potential by reducing oxidative stress [14, 35].

Meanwhile, in black pepper extract, the presence of a significant compound in the form of piperine is strongly suspected to have a role in improving memory. The antioxidant in piperine itself has a mechanism of action by donating one or more electrons to free radicals so that reactions caused by free radicals do not occur, which can cause oxidative stress [36, 37]. According to research conducted, piperine also stated there was a significant reduction in the increase in acetylcholinesterase that was induced by hyoscine because it has a high affinity for binding to acetylcholinesterase so that it cannot act as a catalytic enzyme against acetylcholine [38]. This follows the results obtained with the positive control, which showed that black pepper extract provided the same memory-enhancing activity as ginkgo biloba because it had a similar mechanism of action in inhibiting acetylcholinesterase and acting as an antioxidant. Combining these three natural ingredients is a novelty in searching for active ingredients with neuroprotective effects. To date, there have been no reports on the ability of individual extracts or combinations of extracts to inhibit glutaminase activity to assess their effects as neuroprotective.

Another consequence of brain injury is an increase in the neurotransmitter glutamate due to the excretion of glutaminase. Excess glutamate can cause excitotoxicity, which is a common central pathological factor in many neurological diseases and injuries, especially those showing neuroinflammatory components, such as multiple sclerosis (MS), traumatic brain injury, acute brain anoxia/ischemia, epilepsy, glaucoma, meningitis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Alzheimer's disease, Huntington's disease, Parkinson's disease, and various other diseases. Glutamate itself becomes very toxic in multiple pathological conditions [39–41]. The existence of over-expression of glutamate is a parameter in evaluating the ability of a material to treat brain injury [42].

Glutamate plays a vital role in the normal development and function of the central nervous system (CNS). The benefits of glutamate are that it plays a crucial role in brain activity, including cognition. Glutamate also significantly contributes to the development of the CNS by contributing to the formation and elimination of synaptic nerve contacts, as well as cell migration, differentiation, and regulation of cell death. Given the strong and vital role of glutamate in many body functions and its rapid and robust effects on many target cells, glutamate must be present at the right time, in the right concentration, and in the right amount. Excess glutamate will cause excitotoxicity, a central pathological factor common to many neurological diseases and injuries, especially those showing a neuroinflammatory component, such as multiple sclerosis (MS), traumatic brain injury, acute brain anoxia/ischemia, epilepsy, glaucoma, meningitis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Alzheimer's disease, Huntington's disease, Parkinson's disease, and various other diseases. Glutamate becomes very toxic in multiple pathological conditions when its concentration exceeds its concentration. Meanwhile, glutamate deficiency can cause several problems, including neurological, mood, central nervous system, and metabolic disorders [39–41].

Several studies have reported that gotu kola, turmeric and black pepper extracts have neuroprotective effects. Asiaticoside is one of the asiatic acid derivatives in gotu kola that plays a role in inhibiting glutaminase through its antioxidant properties, so it can reduce the formation of ROS and inhibit the formation of lipid peroxidation [43]. The same thing also happens to the curcumin compound in turmeric which works by inhibiting glutaminase against glutamine metabolism through its antioxidant mechanism. Curcumin is also able to prevent the death of neuron cells after brain injury, one of the consequences of which comes from excessive glutaminase expression [44]. Meanwhile, piperine from black pepper works by improving cognitive disorders and restoring hippocampal neurotransmission, such as excessive glutamate expression due to increased glutaminase activity [45]. These studies support the results of our study and with the combination at certain doses used in this study, it can increase the effect as a neuroprotectant due to brain injury.

This study also observed the inhibitory interactions between chemical molecules by molecular docking of each extract against glutaminase protein to support the in vitro results. The parameters analyzed in this docking study were amino acid residues, hydrogen bonds, and free binding energy (ΔG) [46]. Observation of amino acid residue interactions aims to identify the interactions that occur between the ligand and the receptor. Hydrogen bonds are interactions that can stabilize the ligand bond with the receptor. Other interactions between ligands that can increase conformational stability are electrostatic interactions and van der Walls interactions [25, 47, 48].

The selected and active compounds in inhibiting glutaminase in silico from gotu kola extracts, such as centellasaponin and asiatica derivative, which are compounds of the triterpenoid saponin group and the Quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside compounds are phenolic compounds which are thought to play an essential role in the process of inhibiting over-expression of glutaminase. These compounds interact through hydrogen bonds with vital amino acids of the target protein, namely at residues ASN170, ASN117, GLN67, and VAL266 (fig. 4). For the curcumin derivates specifically interacts through hydrogen bonds at the amino acid residue ASN170, while other compounds, namely bis dimethoxy curcumin, alpha-turmerone, and 1-hydroxy-1,7-bis (4-hydroxyphenyl)-3-methoxyphenyl)-6-heptene-3,5-dione specifically bond hydrogen with the key amino acid GLN67. However, for the compound 1,5-bis (4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,4-pentadien-3-one, there is a hydrogen interaction at the key amino acids ASN170, ASN 117, GLN67, and VAL266 and is very similar to the hydrogen interaction of the native ligand compounds, namely ASN170, ASN117, GLN67, and VAL266 (fig. 5). The similarity of interactions with key amino acids of the target protein glutaminase allows competitive inhibition.

Similar things were also found in the in silico activity of black pepper extract compounds. There is a hydrogen interaction between the active site of the compound with specific amino acid residues, namely ASN117, ASN170, VAL266 and GLN67, so black pepper extract can inhibit excessive glutaminase activity, which triggers brain haemorrhage. The active site in the form of hydroxyl groups and methoxy groups of active compounds generally interact with hydrogen with amino acid residues ASN117, ASN170 and GLN67 and the critical amino acid VAL266 tend to interact with hydrogen with the carbonyl group (C = O) of the compound, especially in cinnamic acid compounds. Meanwhile, in the baricitinib compound, hydrogen interactions on the vital amino acids ASN117 and ASN170 occur in the nitrogen group of the pentacyclic structure of the baricitinib compound (fig. 6). The baricitinib compound reported in black pepper is an alkaloid with the best activity in inhibiting glutaminase, with a binding affinity value of-8.0 kcal/mol. This compound must be studied further regarding its mechanism and pharmacological action. However, based on the chemical structure, the nitrogen group in the alkaloid core certainly interacts with hydrogen with critical amino acids in the glutaminase target protein.

The selected compounds from each gotu kola, turmeric, and black pepper extract showed the best interaction with the target protein glutaminase, with a more negative binding affinity value than the native ligand. However, one of the candidate markers among the identified active compounds from each extract it was shown that the compound Asiaticoside B from gotu kola, 1,5-bis (4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,4-pentadien-3-one from turmeric, and Baricitinib from black pepper in silico gave strong activity. This is because the three compounds have the same active site that interacts with the amino acid residues of the target protein. Fig. 10 is a visualization of the synergistic effect of the three compounds on the target protein.

Fig. 10: Visualization of the interaction of Asiaticoside B (blue color), 1,5-bis (4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,4-pentadien-3-one (red color), and Baricitinib (green color) compounds against the target protein glutaminase. The red circle indicates that the three active compounds interact at the same active site compared to the native ligand (yellow color)

These results support the in vitro study on each extract and the combination extract of the three. In vitro, with parameters of increasing memory and inhibition of glutaminase, shows that the combination formula of the extract effectively increases memory and inhibits over-expression of glutaminase. The potential chemical content influences the synergistic effect of each extract in providing bioactivity and pharmacological effects. The chemical interaction of each compound with the receptor in providing a pharmacological effect is not convincing enough if it is not accompanied by the stability of the bond or interaction through molecular dynamics.

Molecular Dynamics is one of the best methods to investigate the dynamic behaviour of macromolecules at the molecular and atomic levels [49]. Molecular dynamics simulation aims to determine the stability of protein interactions with ligands in conditions similar to human physiology over a certain period. Several parameters evaluated are the RMSD (Root Means Standard Deviation) value, Radius of gyration, and RMSF (root means square fluctuation). These three parameters can evaluate the stability of the interaction of compounds with target proteins [50, 51].

Suppose the RMSD value ≥3 Å indicates that the protein has undergone conformational changes that are very different from its native condition. An increase in the RMSD value indicates that the protein structure is starting to open. The ligand seeks the appropriate binding site or coordinates on the protein. In contrast, a stable RMSD value indicates that the maximum conformation of the protein bound to the ligand is starting to be achieved so that the protein can maintain its position [52, 53]. Similar things were also found in the 5A46-native ligand complex, which experienced an increase in RMSD values in the range of>3 Å. This indicates that the protein-native ligand complex tends to be less stable when compared to the protein-compound complex. However, observing the profile of the increase in RMSD values in the compounds 1,5-bis (4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,4-pentadien-3-one and Baricitinib did not provide a significant picture because at 100 NM time there was a decrease in RMSD values. Therefore, the RMSD observations on the three compounds showed fairly stable results.

The next parameter is the RMSF value in the 5A46 complex and the compound/native ligand. RMSF (Root mean Square Fluctuation) measures the deviation between the particle position and several reference positions. RMSF can be calculated for each amino acid residue that makes up the protein by looking at the extent of the fluctuation of the movement of each amino acid residue during the simulation [54, 55]. The purpose of RMSF analysis in molecular dynamics simulations is to obtain information about flexible and rigid amino acid residues during the simulation process [56]. Fig. 9 is a visualization of molecular dynamics on the RMSF parameters of the Protein-ligand complex. Low flexibility describes the stability of the interaction of the protein complex with the ligand. The maximum value of amino acid residues is 2.5 Å. RMSF values <2.5Å indicate low flexibility. The flexibility of amino acid residues describes the stability of the interaction at the active site that binds to the test compound because the atoms that make up the amino acid residues tend not to change many positions during the molecular dynamics simulation [57].

The protein radius of gyration is also analyzed in addition to RMSD and RSMF. The protein radius of gyration is the distance of the distribution of protein atoms from its main axis. The radius of gyration in molecular dynamics simulations provides information about changes in protein size during dynamic simulations. Therefore, the larger the radius of gyration, the larger the protein [52]. The profile of changes in the protein radius of gyration during molecular dynamics simulations of complexes with compound and native ligands. Changes in the size of 5A46 with ligands during molecular dynamics simulations did not experience significant changes in either the protein-ligand complex Asiaticosid B, 1,5-bis (4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,4-pentadien-3-one, and Baricitinib. Although at 80 NM, there was an increase in the radius of gyration, it returned to the appropriate size at 100 NM. This increase did not occur significantly, showing that the protein-ligand complex resulting from docking is quite stable. This can also be adjusted to the evaluation results of RMSD and RMSF values that did not experience significant changes. The study of molecular dynamic analysis of protein complexes with the most active compound ligands and native ligands showed quite good results and showed a stable protein-ligand complex.

Exploration in this study allows the development of a combination of gotu kola, turmeric, and black pepper extracts as an alternative treatment for brain injury. This study is still limited to exploring the bioactivity of single extracts and combination extracts used as candidates for active ingredients as neuroprotective. This discovery will be developed to obtain standardized natural product ingredients. Quantitative analysis of the levels of active compounds in the extract also needs to be done to regulate the dosage regimen as a neuroprotective. The form of the dosage formula is also essential to be developed to provide a better effect as a neuroprotective. In future developments, a combination dose of gotu kola, turmeric, and black pepper extracts can be applied as an alternative neuroprotective treatment. A combination dose regimen with a ratio of 50:50:50 of each extract can be formulated into a microencapsulation form and intended for oral administration. This approach can be done to produce phytopharmaceutical drug candidates that can be tested clinically.

CONCLUSION

Bioactivity studies of gotu kola, turmeric and black pepper extracts in treating brain injury through memory enhancement parameters in the Y-Maze, in vitro studies in inhibiting glutaminase expression and molecular docking approaches that have been carried out show a good correlation of activity. The bioactivity of the extracts individually has shown a good effect. In silico testing through molecular docking identified several compounds with glutaminase 5A46 inhibitory activity. Still, in each extract, only the most active compound was selected. It showed asiaticoside B, 1,5-bis (4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,4-pentadien-3-one, and Baricitinib compounds with more negative binding affinity values and have a hydrogen interaction profile to amino acid residues similar to the native ligand. The three compounds were also evaluated for their stability through molecular dynamics, and the evaluation results showed that they had stability when interacting with the target protein. After being evaluated, the combination of the extracts is very supportive of being developed as one of the standardized herbal products for treating brain injury.

ETHIC APPROVALS

This method has been equipped with a code of research ethics in the use of experimental animals as subjects for in vivo research obtained from the Research Ethics Code of Medical Faculty, Hasanuddin University, Makassar, South Sulawesi, Indonesia, with ID number 40611IN4.6.4.5.31/PP36/2024.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The author would like to thank the Pharmaceutical Analysis and Medicinal Chemistry Laboratory of Almarisah Madani University for its enzyme testing facilities and the Medicinal Chemistry Laboratory, Faculty of Pharmacy, Hasanuddin University, for its molecular dynamic evaluation.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

AR, MA, AA, AAI: Concept or ideas, design, Clinical trial, Experimental Studies, Data Analysis, manuscript preparation. KP, SS, and HL: Literature search, collected the data, data acquisition, manuscript editing. NS, BY, SN: in silico design, In vitro experimental studies, statistical analysis, manuscript review, manuscript revision.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that is there not conflict of interest with the data contained in the manuscript.

REFERENCES

Awasthi A, Bhaskar S, Panda S, Roy S. A review of brain injury at multiple time scales and its clinicopathological correlation through in silico modeling. Brain Multiphys. 2024 Jun;6:100090. doi: 10.1016/j.brain.2024.100090.

Azriyantha MR, Syaiful Saanin, Hesty Lidya Ningsih. Relationship of the degree of head injury based on glasgow coma scale (gcs) with the arrival of acute post-concussion syndrome (pcs) onset in post-head injury patients in general hospital dr.m.djamil padang. Biomed J Indones. 2021;7(1):153-69. doi: 10.32539/bji.v7i1.273.

Samma L, Widodo D. A case evaluation of traumatic brain injury in wahidin sudirohusodo hospital makassar during jan 2016 dec 2017. Bali Med J. 2019;8(3):S542-6. doi: 10.15562/bmj.v8i3.1569.

NG SY, Lee AY. Traumatic brain injuries: pathophysiology and potential therapeutic targets. Front Cell Neurosci. 2019 Nov 27;13:528. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2019.00528, PMID 31827423.

Baracaldo Santamaria D, Ariza Salamanca DF, Corrales Hernandez MG, Pachon-Londono MJ, Hernandez Duarte I, Calderon Ospina CA. Revisiting excitotoxicity in traumatic brain injury: from bench to bedside. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14(1):152. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14010152, PMID 35057048.

Byrdwell WC, Goldschmidt RJ. Fatty acids of ten commonly consumed pulses. Molecules. 2022;27(21):7260. doi: 10.3390/molecules27217260, PMID 36364086.

Zhou Y, Danbolt NC. Glutamate as a neurotransmitter in the healthy brain. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2014;121(8):799-817. doi: 10.1007/s00702-014-1180-8, PMID 24578174.

Sidoryk Węgrzynowicz M, Adamiak K, Strużynska L. Astrocyte neuron interaction via the glutamate-glutamine cycle and its dysfunction in tau dependent neurodegeneration. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(5):3050. doi: 10.3390/ijms25053050, PMID 38474295.

Sandhu MR, Gruenbaum BF, Gruenbaum SE, Dhaher R, Deshpande K, Funaro MC. Astroglial glutamine synthetase and the pathogenesis of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Front Neurol. 2021;12:665334. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.665334, PMID 33927688.

Chandrika UG, Prasad Kumarab PA. Gotu kola (Centella asiatica): nutritional properties and plausible health benefits. Adv Food Nutr Res. 2015;76:125-57. doi: 10.1016/bs.afnr.2015.08.001, PMID 26602573.

Astiani R, Sadikin M, Eff AR, Firdayani SFD, Suyatna FD. In silico identification testing of triterpene saponines on Centella asiatica on inhibitor renin activity antihypertensive. Int J Appl Pharm. 2022;14(2):1-4. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2022.v14s2.44737.

Sun B, WU L, WU Y, Zhang C, Qin L, Hayashi M. Therapeutic potential of Centella asiatica and its triterpenes: a review. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:568032. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.568032, PMID 33013406.

Sharifi Rad J, Rayess YE, Rizk AA, Sadaka C, Zgheib R, Zam W. Turmeric and its major compound curcumin on health: bioactive effects and safety profiles for food pharmaceutical biotechnological and medicinal applications. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:1021. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.01021, PMID 33041781.

El Saadony MT, Yang T, Korma SA, Sitohy M, Abd El Mageed TA, Selim S. Impacts of turmeric and its principal bioactive curcumin on human health: pharmaceutical medicinal and food applications: a comprehensive review. Front Nutr. 2022;9:1040259. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.1040259, PMID 36712505.

Sarker MR, Franks SF. Efficacy of curcumin for age-associated cognitive decline: a narrative review of preclinical and clinical studies. Gero Science. 2018;40(2):73-95. doi: 10.1007/s11357-018-0017-z, PMID 29679204.

Song Y, Cao C, XU Q, GU S, Wang F, Huang X. Piperine attenuates TBI-induced seizures via inhibiting cytokine-activated reactive astrogliosis. Front Neurol. 2020 Jun 4;11:431. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00431, PMID 32655468.

Stojanovic Radic Z, Pejcic M, Dimitrijevic M, Aleksic A, Kumar VA, Salehi B. Piperine a major principle of black pepper: a review of its bioactivity and studies. Appl Sci. 2019;9(20):4270. doi: 10.3390/app9204270.

Tripathi AK, Ray AK, Mishra SK. Molecular and pharmacological aspects of piperine as a potential molecule for disease prevention and management: evidence from clinical trials. Beni Suef Univ J Basic Appl Sci. 2022;11(1):16. doi: 10.1186/s43088-022-00196-1, PMID 35127957.

Rather RA, Bhagat M. Cancer chemoprevention and piperine: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2018 Feb 15;6:10. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2018.00010, PMID 29497610.

Nazıroglu M. TRPV1 channel: a potential drug target for treating epilepsy. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2015;13(2):239-47. doi: 10.2174/1570159x13666150216222543, PMID 26411767.

Kraeuter AK, Guest PC, Sarnyai Z. The Y-maze for assessment of spatial working and reference memory in mice. Methods Mol Biol. 2019;1916:105-11. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-8994-2_10, PMID 30535688.

Cederkvist H, Kolan SS, Wik JA, Sener Z, Skalhegg BS. Identification and characterization of a novel glutaminase inhibitor. FEBS Open Bio. 2022;12(1):163-74. doi: 10.1002/2211-5463.13319, PMID 34698439.

Almashhedy LA, Hadwan MH, Abbas Khudhair D, Kadhum MA, Hadwan AM, Hadwan MM. An optimized method for estimating glutaminase activity in biological samples. Talanta. 2023;253:123899. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2022.123899, PMID 36084433.

Nur S, Hanafi M, Setiawan H, Elya B. Chemical characterization and biological activity of molineria latifolia root extract as dermal antiaging: isolation of natural compounds in silico and in vitro study. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2024 Feb;56:103039. doi: 10.1016/j.bcab.2024.103039.

Nur S, Hanafi M, Setiawan H, Nursamsiar N, Elya B. In silico evaluation of the dermal antiaging activity of molineria latifolia (dryand. ex w.t. aiton) herb. ex kurz compounds. J Pharm Pharmacogn Res. 2023;11(2):325-45. doi: 10.56499/jppres23.1606_11.2.325.

Rasyid H, Soekamto NH, Firdausiah S, Mardiyanti R, Bahrun B, Siswanto S. Revealing the potency of 1,3,5-trisubstituted pyrazoline as antimalaria through combination of in silico studies. Sains Malays. 2023;52(10):2855-67. doi: 10.17576/jsm-2023-5210-10.

Idris FN, Mohd Nadzir M. Comparative studies on different extraction methods of Centella asiatica and extracts bioactive compounds effects on antimicrobial activities. Antibiotics (Basel). 2021;10(4):457. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10040457, PMID 33920563.

Gray NE, Alcazar Magana A, Lak P, Wright KM, Quinn J, Stevens JF. Centella asiatica phytochemistry and mechanisms of neuroprotection and cognitive enhancement. Phytochem Rev. 2018;17(1):161-94. doi: 10.1007/s11101-017-9528-y, PMID 31736679.

Tiwari A, Mahadik KR, Gabhe SY. Piperine: a comprehensive review of methods of isolation purification and biological properties. Medicine in Drug Discovery. 2020 Sep;7:100027. doi: 10.1016/j.medidd.2020.100027.

Rauf MA. Scopolamine induced memory impairment in mice: neuroprotective effects of Carissa edulis (Forssk.) Valh (Apocynaceae) aqueous extract. In: Nanotechnology methods for neurological diseases and brain tumors. United States; 2017. p. 187-95.

Noor E, Tabassum E, Das R, Lami MS, Chakraborty AJ, Mitra S, Tallei TE. Ginkgo biloba: a treasure of functional phytochemicals with multi-medicinal applications. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2022;2022:8288818. doi: 10.1155/2022/8288818, PMID 35265150.

Batubara I, Darusman LK, Mitsunaga T, Rahminiwat M, Djauhari E. Potency of Indonesian medicinal plants as tyrosinase inhibitor and antioxidant agent. J Biol Sci. 2010;10(2):138-44. doi: 10.3923/jbs.2010.138.144.

Gohil KJ, Patel JA, Gajjar AK. Pharmacological review on Centella asiatica: a potential herbal cure-all. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2010;72(5):546-56. doi: 10.4103/0250-474X.78519, PMID 21694984.

Bandopadhyay S, Mandal S, Ghorai M, Jha NK, Kumar M, Radha. Therapeutic properties and pharmacological activities of asiaticoside and madecassoside: a review. J Cell Mol Med. 2023;27(5):593-608. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.17635, PMID 36756687.

Hewlings SJ, Kalman DS. Curcumin: a review of its effects on human health. Foods. 2017;6(10):92. doi: 10.3390/foods6100092, PMID 29065496.

Kumar S, Malhotra S, Prasad AK, Van Der Eycken EV, Bracke ME, Stetler-Stevenson WG. Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties of piper species: a perspective from screening to molecular mechanisms. Curr Top Med Chem. 2015;15(9):886-93. doi: 10.2174/1568026615666150220120651, PMID 25697561.

Sharma H, Sharma N, An SS. Black pepper (Piper nigrum) alleviates oxidative stress exerts potential anti-glycation and anti-AChE activity: a multitargeting neuroprotective agent against neurodegenerative diseases. Antioxidants (Basel). 2023;12(5):1089. doi: 10.3390/antiox12051089, PMID 37237954.

Abdul Manap AS, Wei Tan AC, Leong WH, Yin Chia AY, Vijayabalan S, Arya A. Synergistic effects of curcumin and piperine as potent acetylcholine and amyloidogenic inhibitors with significant neuroprotective activity in SH-SY5Y cells via computational molecular modeling and in vitro assay. Front Aging Neurosci. 2019;11:206. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2019.00206, PMID 31507403.

Bornstein R, Mulholland MT, Sedensky M, Morgan P, Johnson SC. Glutamine metabolism in diseases associated with mitochondrial dysfunction. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2023;126:103887. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2023.103887, PMID 37586651.

Iovino L, Tremblay ME, Civiero L. Glutamate induced excitotoxicity in parkinsons disease: the role of glial cells. J Pharmacol Sci. 2020;144(3):151-64. doi: 10.1016/j.jphs.2020.07.011, PMID 32807662.

Belov Kirdajova D, Kriska J, Tureckova J, Anderova M. Ischemia triggered glutamate excitotoxicity from the perspective of glial cells. Front Cell Neurosci. 2020;14:51. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2020.00051, PMID 32265656.

Hinzman JM, Thomas TC, Burmeister JJ, Quintero JE, Huettl P, Pomerleau F. Diffuse brain injury elevates tonic glutamate levels and potassium evoked glutamate release in discrete brain regions at two days post injury: an enzyme-based microelectrode array study. J Neurotrauma. 2010;27(5):889-99. doi: 10.1089/neu.2009.1238, PMID 20233041.

Ding L, Liu T, MA J. Neuroprotective mechanisms of asiatic acid. Heliyon. 2023;9(5):e15853. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e15853, PMID 37180926.

Park CH, Song JH, Kim SN, Lee JH, Lee HJ, Kang KS. Neuroprotective effects of tetrahydrocurcumin against glutamate induced oxidative stress in hippocampal HT22 cells. Molecules. 2019;25(1):144. doi: 10.3390/molecules25010144, PMID 31905820.

Balakrishnan R, Azam S, Kim IS, Choi DK. Neuroprotective effects of black pepper and its bioactive compounds in age related neurological disorders. Aging Dis. 2023;14(3):750-77. doi: 10.14336/AD.2022.1022, PMID 37191428.

Nur S, Hanafi M, Setiawan H, Nursamsiar N, Elya B. Molecular docking simulation of reported phytochemical compounds from Curculigo latifolia extract on target proteins related to skin antiaging. Trop J Nat Prod Res. 2023;7(11):5067-80.

Nur S, Setiawan H, Hanafi M, Elya B. Phytochemical composition antioxidant in vitro and in silico studies of active compounds of Curculigo latifolia extracts as promising elastase inhibitor. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2023;30(8):103716. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2023.103716, PMID 37457237.

Nursamsiar SM, Siregar M, Awaluddin A, Nurnahari N, Nur S, Febrina E. Molecular docking and molecular dynamic simulation of the aglycone of curculigoside a and its derivatives as alpha glucosidase inhibitors. Rasayan J Chem. 2020;13(1):690-8. doi: 10.31788/RJC.2020.1315577.

Hollingsworth SA, Dror RO. Molecular dynamics simulation for all. Neuron. 2018;99(6):1129-43. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.08.011, PMID 30236283.

Priya R, Sumitha R, Doss CG, Rajasekaran C, Babu S, Seenivasan R. Molecular docking and molecular dynamics to identify a novel human immunodeficiency virus inhibitor from alkaloids of Toddalia asiatica. Pharmacogn Mag. 2015;11 Suppl 3:S414-22. doi: 10.4103/0973-1296.168947, PMID 26929575.

Ghahremanian S, Rashidi MM, Raeisi K, Toghraie D. Molecular dynamics simulation approach for discovering potential inhibitors against SARS-CoV-2: a structural review. J Mol Liq. 2022;354:118901. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2022.118901, PMID 35309259.

Rampogu S, Lee G, Park JS, Lee KW, Kim MO. Molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations discover Curcumin analogue as a plausible dual inhibitor for SARS-COV-2. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(3):1771. doi: 10.3390/ijms23031771, PMID 35163692.

Abdalla M, Eltayb WA, El Arabey AA, Singh K, Jiang X. Molecular dynamic study of SARS-CoV-2 with various S protein mutations and their effect on thermodynamic properties. Comput Biol Med. 2022;141:105025. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2021.105025, PMID 34772510.

Sharma J, Kumar Bhardwaj V, Singh R, Rajendran V, Purohit R, Kumar S. An in-silico evaluation of different bioactive molecules of tea for their inhibition potency against non structural protein-15 of SARS-CoV-2. Food Chem. 2021;346:128933. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128933, PMID 33418408.