Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 2, 2025, 190-197Original Article

EXPLORING THE ANTI-INFLAMMATORY PROPERTIES OF METFORMIN IN EXPERIMENTAL HEMORRHOID MODELS

DARMAWI DARMAWI1, MUHAMMAD YULIS HAMIDY2, SORAYA SORAYA3, NURUL AZIZAH3, LALU MUHAMMAD IRHAM4, BAIQ LENY NOPITASARI5, INA F. RANGKUTI6, A. A. MUHAMMAD NUR KASMAN7,8, WIRAWAN ADIKUSUMA5,9*

1Department of Histology, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Riau, Pekanbaru, Indonesia. 2Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Riau, Pekanbaru, Indonesia. 3Master Program in Biomedical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Riau, Pekanbaru, Indonesia. 4Faculty of Pharmacy, Universitas Ahmad Dahlan, Yogyakarta, Indonesia. 5Department of Pharmacy, Faculty of Health Science, Universitas Muhammadiyah Mataram, Mataram, Indonesia. 6Department of Pathology Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Riau, Pekanbaru, Indonesia. 7Research Center for Applied Zoology, Research Organization for Life Sciences and Environment, National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), Cibinong, Indonesia. 8Department of Midwifery, Faculty of Health Science, Universitas Muhammadiyah Mataram, Mataram, Indonesia. 9Research Center for Computing, Research Organization for Electronics and Informatics, National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), Cibinong, Indonesia

*Corresponding author: Wirawan Adikusuma; *Email: adikusuma28@gmail.com

Received: 05 Nov 2024, Revised and Accepted: 16 Dec 2024

ABSTRACT

Objective: This study investigated the anti-inflammatory potential of metformin as a therapeutic agent in an experimental hemorrhoid model using Sprague-Dawley rats.

Methods: Rats were assigned to six groups: normal control, negative control (hemorrhoid-induced without treatment), positive control (hemorrhoid-induced and treated with aspirin), and three metformin-treated groups receiving 3 mg/kg, 9 mg/kg, and 15 mg/kg body weight doses. Metformin's effects were assessed through macroscopic observation, qPCR analysis of IL-6, TNF-α, IL-10, and COX-2 gene expression, and histopathological examination of leukocyte infiltration and venule diameter.

Results: qPCR analysis revealed significant reductions in IL-6 and TNF-α expression in metformin-treated groups compared to the negative control. Specifically, the 9 mg/kg dose achieved a 99% reduction in IL-6 and over 98% reduction in TNF-α expression. COX-2 expression was also significantly decreased in metformin-treated groups (p<0.0001), while IL-10 expression remained unchanged (p=0.3973). Histopathological analysis showed a dose-dependent reduction in leukocyte infiltration, with the 15 mg/kg dose exhibiting the most significant decrease (p<0.0001). Additionally, metformin treatment resulted in a significant reduction in venule diameter, particularly at the 15 mg/kg dose (p<0.0001).

Conclusion: These results suggest that metformin, especially at higher doses, has significant anti-inflammatory effects in experimental hemorrhoid models, indicating its potential as a promising therapeutic option for hemorrhoid treatment.

Keywords: Anti-inflammatory effects, Gene expression, Hemorrhoids, Leukocyte infiltration, Metformin

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i2.53174 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Hemorrhoids are a prevalent medical condition characterized by the swelling and inflammation of blood vessels in the rectal and anal regions. These conditions arise due to the dilation of the hemorrhoidal plexus, a vascular cushion composed of fibroelastic tissue, muscle fibers, and blood vessels [1, 2]. Globally, approximately 50% to 85% of individuals experience hemorrhoids, affecting people of all genders and ages [3]. Hemorrhoids develop due to increased vascular pressure caused by factors like pregnancy, aging, and chronic constipation [4, 5]. Although not life-threatening, hemorrhoids can lead to uncomfortable symptoms such as pain, itching, bleeding, and thrombosis [6]. The pathological changes associated with hemorrhoids include abnormal vein dilation, vascular thrombosis, collagen breakdown, transformation of fibroelastic tissue, and disruption of the structural integrity of subepithelial anal muscles [7]. Inflammation plays a critical role in the progression of hemorrhoids, with key inflammatory mediators such as Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and cytokines like IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α being involved in the inflammatory response [8].

Current treatment approaches for hemorrhoids range from non-surgical methods, including rubber band ligation and sclerotherapy, to surgical interventions like hemorrhoidectomy, particularly in severe cases [9, 10]. However, these treatments often focus on symptom relief rather than addressing the underlying causes, leading to potential recurrence [11]. Consequently, there is a growing need for alternative therapeutic strategies that not only alleviate symptoms but also target the inflammatory processes central to hemorrhoid development.

Recent studies suggest that metformin, a widely prescribed oral medication for the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus [12-14], may have anti-inflammatory properties that could be beneficial in treating hemorrhoids. Studies have shown that metformin reduces the risk of varicose veins, a condition with a similar pathophysiology to hemorrhoids, in patients with type 2 diabetes [15]. Moreover, metformin has been demonstrated to inhibit pro-inflammatory pathways, such as the NF-κB signaling cascade, thereby reducing the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α [16, 17]. The potential of metformin as a therapeutic agent in hemorrhoid treatment lies in its ability to modulate inflammatory responses. It is hypothesized that metformin not only decreases COX-2 expression but also enhances anti-inflammatory mediators like IL-10, offering a dual approach to mitigating inflammation in hemorrhoid conditions [18, 19]. Despite these promising findings, no studies have specifically explored the anti-inflammatory effects of metformin on hemorrhoid models.

This study aims to fill this gap by investigating the anti-inflammatory effects of metformin in a rat model of hemorrhoids. The research will focus on evaluating changes in COX-2, IL-10, IL-6, and TNF-α mRNA expression levels, with the goal of providing a more comprehensive understanding of metformin's therapeutic potential in hemorrhoid treatment. By addressing both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory pathways, this study seeks to offer a novel approach that could lead to more effective and sustainable hemorrhoid management strategies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Hemorrhoids models

This study involved 18 Sprague-Dawley rats divided into six groups through simple random sampling. The rats were housed individually under standard laboratory conditions with a 12 h light-dark cycle (lights on from 7:00 AM to 7:00 PM) and given ad libitum access to a standard rodent diet and water [20]. Before the experiment, they underwent a 7 d acclimatization period to adjust to the laboratory environment, ensuring optimal health.

Hemorrhoids in the rats were induced following a previous study [21]. Briefly, a 6% Croton oil solution (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) was applied, diluted with ether and pyridine to ensure stability and precise application. The dilution ratio was 10:4:5:1 for Croton oil, pyridine, ether, and deionized water [22]. From day 8, all groups, except the normal control, were induced with hemorrhoids using 6% Croton oil for three consecutive days, while the normal group received acetone.

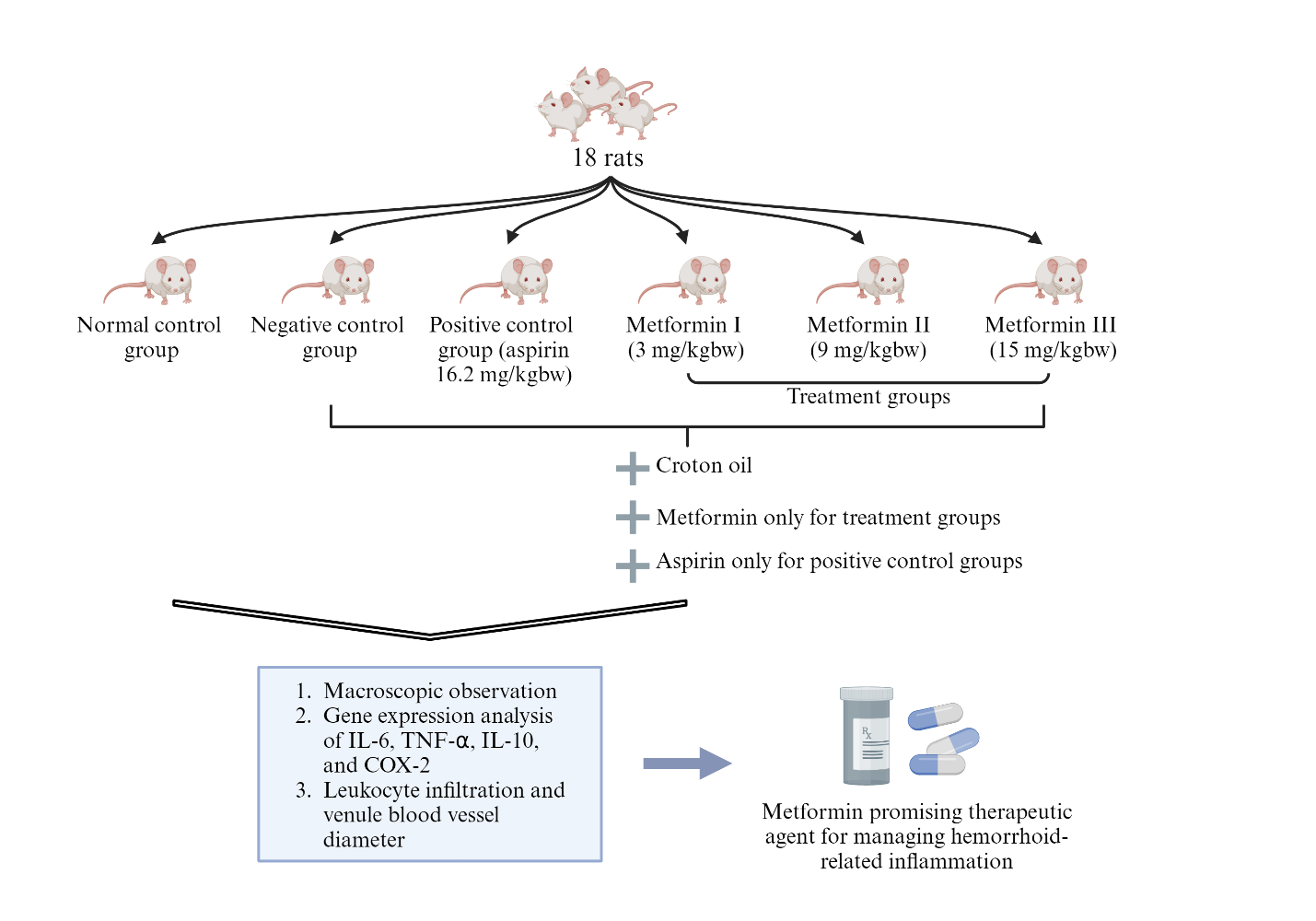

The experimental groups were treated following previous study [20]. Briefly, rats were divided into three metformin-treated groups receiving 3 mg/kg, 9 mg/kg, and 15 mg/kg body weight doses of metformin, administered orally via gavage for 7 consecutive days. Metformin was dissolved in distilled water for consistent delivery. The positive control group received 16.2 mg of aspirin, also administered orally via gavage, with distilled water as the solvent to ensure aspirin stability. The negative control group received standard feed and water without any drug treatment. All groups had continuous access to standard feed and water throughout the experiment. On day 14, all rats were euthanized using an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine/xylazine (10 ml/kg body weight). The study workflow is shown in fig. 1.

Fig. 1: Study design of metformin as a therapeutic agent in managing hemorrhoid-related inflammation

RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis and RT-PCR

The sample consisted of rat anorectal tissues. The tissue was homogenized using a micropestle. RNA extraction was performed using the torax nucleic acid extraction kit (Torax Biosciences, NI, United Kingdom) with the magnetic bead method. Briefly, the process began with homogenizing the torax plate in a Biosafety Cabinet. Next, 15 μl of proteinase K was added to columns 1 and 7 of the torax plate, followed by the addition of 200 μl of the vortexed sample to both columns. The torax plate was then placed in the torax machine, and the tip comb was inserted. The extraction process was run for 10 min, after which the RNA was ready for collection. The isolated RNA from columns 6 and 12 was transferred to a microtube. The isolated RNA could be used immediately or stored at-20 °C. Subsequent to this, the concentration and purity of the RNA were measured using a plate reader.

The extracted RNA was used as a template for cDNA synthesis. The first step involved preparing the reverse transcription reaction mixture. This mixture included RNA template, oligo (dT) or random primers, GoScript Reverse Transcriptase, dNTP mix, buffer reaction, and RNase inhibitor. All components were mixed in a prepared tube. The reverse transcription reaction began with incubation at 25 °C for 5 min to allow primers to bind to the RNA template. The temperature was then increased to 42 °C for 60 min to allow the reverse transcriptase enzyme to synthesize cDNA from the RNA template. After cDNA synthesis was complete, the reaction was stopped by heating the mixture to 70 °C for 15 min to inactivate the reverse transcriptase enzyme. The synthesized cDNA was then ready for use in subsequent PCR reactions.

The detection and quantification of RNA in samples were performed using a two-step qPCR technique. First, RNA was extracted from samples and converted into cDNA through RT. Next, PCR reactions were prepared by mixing cDNA with a master mix containing all necessary components. The PCR reactions were then conducted with a cycle consisting of denaturation, annealing, and elongation phases, followed by fluorescence detection to track DNA amplification. The data obtained were analyzed to determine the amount of RNA in samples based on cycle threshold (CT) values and amplification curves. The data from qPCR were analyzed using Livak's method (2ΔΔCT) to quantitatively determine the amount of RNA in samples for further analysis [23].

ELISA

Blood samples from rats were directly placed in EDTA tubes. The next step involved separating serum from red blood cells. The Eppendorf tube was centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 15 min to separate heavier red blood cells from lighter serum. After centrifugation was complete, the supernatant containing serum was carefully collected using a sterile pipet and transferred to a sterile tube. The serum was then stored at-20 °C for subsequent ELISA analysis.

ELISA for IL-10 in rat serum using the ABclonal IL-10 Kit (RK00050) began with preparing reagents, including washing buffer, blocking buffer, IL-10 standard, conjugated antibodies, and enzyme-substrate, according to the appropriate mixing and dilution instructions. Rat serum was diluted according to the specified ratio in the protocol, and IL-10 standard, control, and serum samples were added to ELISA wells. After incubation, well contents were discarded and washed several times. Conjugated antibodies were added and incubated followed by washing again. Enzyme substrate was added and incubated before stopping the reaction with a stop solution. Optical absorbance was measured at 450 nm using an ELISA reader plate reader. Absorbance data were used to calculate IL-10 concentrations in rat serum samples using standard curves and analyzed using Skanlt 6.1 RE for Microplate Reader software.

Histopathology of infiltration leukocyte cells and venules measurements

On day 11, all animals were euthanized using ketamine-xylazine (40-80 mg/kg+5-10 mg/kg) and terminated. Rectal tissue samples were taken for histopathological confirmation of hemorrhoid treatment. The anorectal tissue samples were fixed in 10% formalin and embedded in paraffin. The samples were cut into 5 μm sections and stained with HandE [20]. Slides were examined under a Leica microscope and one field of view representing anorectal tissue was taken. Using the Leica application connecting microscope images to the screen, the diameter of venules and infiltration leukocyte cells was measured according to the images on the screen. The evaluation was done with a 40X magnification.

The diameter of venules was analyzed in detail using a microscope and Leica application. The specimen was prepared and observed under the microscope until the image was clear. The microscope was connected to a computer with the Leica application installed. The appropriate observation mode was selected, ensuring the best image quality for venule diameter analysis and leukocyte cells. The slide was examined under a Leica microscope and one field of view representing anorectal tissue was taken. After selecting the observation mode, the zoom feature on the application was used to enlarge the area containing venules. Navigation tools on the application were used to adjust the position so that venules were centered on the screen. The measurement tool available in Leica was activated. The tool typically includes a ruler or distance measurement icon. The starting point of measurement was placed at one side of the venule diameter. The measurement line was extended to reach the other side of the venule diameter. The Leica application automatically calculated and displayed the length of this line, which represented the measured venule diameter. After all measurements were completed, images and results were saved in the specified format. We employed a scoring system that involved manual calculation for each sample to assess leukocyte infiltration. We summed the scoring values and then executed an ANOVA statistical test.

RESULTS

Induction of hemorrhoids and experimental group observations

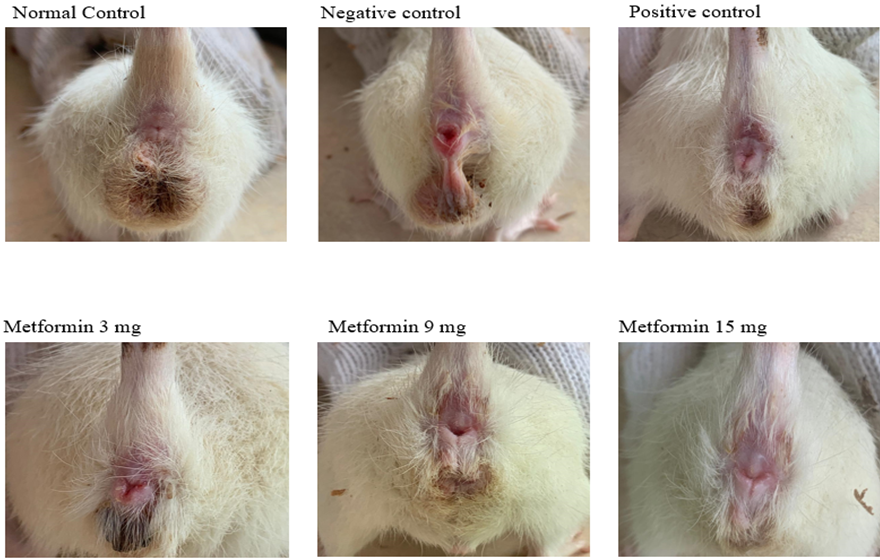

In this study, we divided the experimental rats into six groups, each containing three rats. The groups included three metformin-treated groups (receiving 3 mg/kg, 9 mg/kg, and 15 mg/kg doses), a normal control group, a negative control group (hemorrhoid-induced without treatment), and a positive control group (hemorrhoid-induced and treated with aspirin). Our findings on the macroscopic observations of hemorrhoid-induced rats, particularly the dose-dependent reduction in inflammation with metformin, are consistent with previous research on its anti-inflammatory properties. Metformin's efficacy in reducing inflammation has been documented in models of colitis, where similar reductions in redness and swelling were observed upon metformin administration [24]. This further supports the hypothesis that metformin’s anti-inflammatory mechanism may be generalized across different inflammation-related conditions, including hemorrhoids (fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Macroscopic images of the anus captured for each rat group

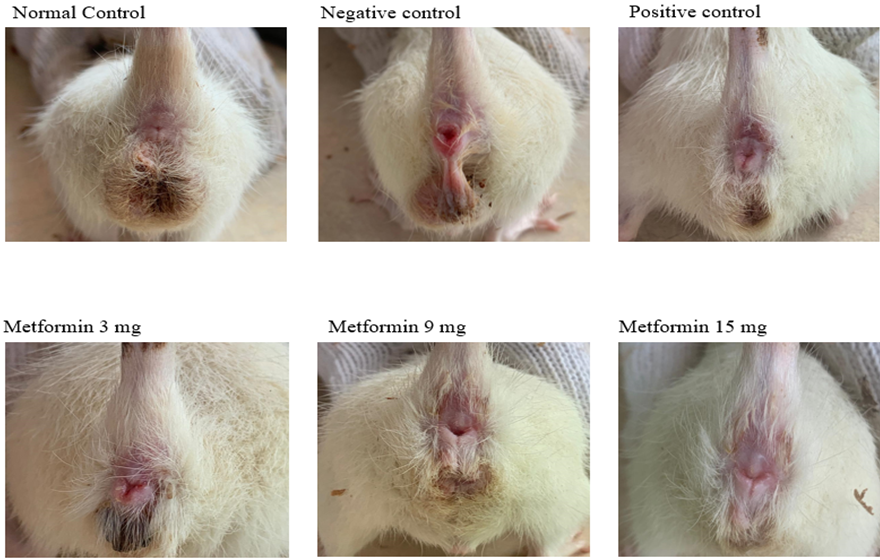

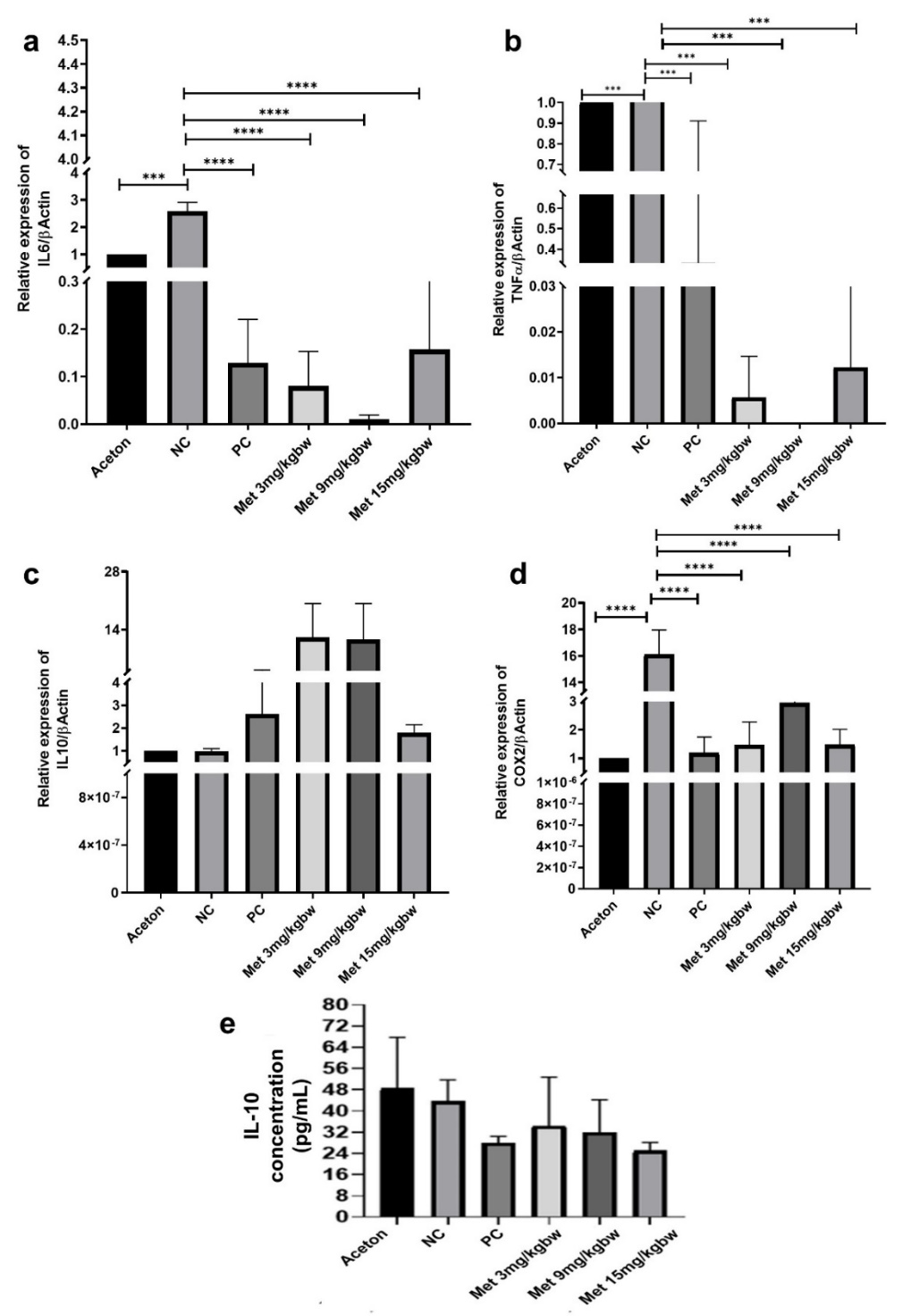

Relative expression analysis of IL-6, TNF-α, IL-10 and COX-2 genes using qPCR

The analysis of IL-6, TNF-α, IL-10, and COX-2 gene expressions was conducted using qPCR. The statistical analysis revealed significant differences among the groups for IL-6 expression (fig. 3A). The negative control group showed a substantial increase in IL-6 expression (158.7%), while the positive control exhibited an 87.1% reduction. Metformin treatment resulted in a marked reduction, particularly in the 9 mg/kg dose group, which showed a 99% reduction, suggesting that metformin, especially at a dose of 9 mg/kg, is effective in reducing IL-6 expression.

Similarly, TNF-α expression showed significant differences across the groups (fig. 3B). The negative control group exhibited the highest increase, while metformin significantly suppressed TNF-α expression in all treated groups, with reductions of 99%, 99.5%, and 98.8% at doses of 3 mg/kg, 9 mg/kg, and 15 mg/kg, respectively. This suggests a potent anti-inflammatory effect of metformin on TNF-α expression.

The relative expression of IL-10 was analyzed, and the one-way ANOVA test indicated no significant differences across the groups (p=0.3973) (fig. 3C), suggesting that metformin did not significantly alter IL-10 expression compared to the control groups. However, metformin significantly modulated COX-2 expression (p<0.0001) (fig. 3D). Detailed comparative data of COX-2 expression, including the mean±SD, 95% CI of difference, and p-values between all groups, are presented in table 1. These results align with metformin’s known anti-inflammatory effects, particularly in suppressing IL-6, TNF-α, and COX-2 expression, but not IL-10. In addition to gene expression, IL-10 protein levels were evaluated using ELISA (fig. 3E), with no significant differences among the groups (p=0.2330). This suggests that metformin did not significantly impact IL-10 protein levels in this experimental setup.

Fig. 3: Metformin treatment in hemorrhoid models reduces expression of (A) IL-6, (B) TNF-α, and (D) COX2, but not IL-10 (C and E). All results are shown as mean±SD of triplicate experiments in each of the two independent experiments. NC-Negative control, PC-Positive control, Met-Metformin, ***<0.001, ****<0.0001

Table 1: Comparative data of COX-2 expression with mean±SD, 95% CI of difference, and P value between all groups

| Tukey's multiple comparisons test | Mean Diff, | 95,00% CI of diff, | P value |

| Normal vs. Positive control | -0.1973 | -4,433 to 4,038 | >0,9999 |

| Normal vs. Negative control | -15.13 | -19,37 to-10,90 | <0,0001 |

| Normal vs. Metformin 3 mg/kg | -0.4686 | -4,704 to 3,767 | 0.9988 |

| Normal vs. Metformin 9 mg/kg | -1.96 | -6,196 to 2,276 | 0.6396 |

| Normal vs. Metformin 15 mg/kg | -0.4869 | -4,723 to 3,749 | 0.9986 |

| Positive control vs. Negative control | -14.94 | -19,17 to-10,70 | <0,0001 |

| Positive control vs. Metformin 3 mg/kg | -0.2712 | -4,507 to 3,965 | >0,9999 |

| Positive control vs. Metformin 9 mg/kg | -1.763 | -5,999 to 2,473 | 0.7278 |

| Positive control vs. Metformin 15 mg/kg | -0.2896 | -4,525 to 3,946 | 0.9999 |

| Negative control vs. Metformin 3 mg/kg | 14.66 | 10,43 to 18,90 | <0,0001 |

| Negative control vs. Metformin 9 mg/kg | 13.17 | 8,937 to 17,41 | <0,0001 |

| Negative control vs. Metformin 15 mg/kg | 14.65 | 10,41 to 18,88 | <0,0001 |

| Metformin 3 mg vs. Metformin 9 mg/kg | -1.492 | -5,727 to 2,744 | 0.8367 |

| Metformin 3 mg vs. Metformin 15 mg/kg | -0.01833 | -4,254 to 4,217 | >0,9999 |

| Metformin 9 mg vs. Metformin 15 mg/kg | 1.473 | -2,762 to 5,709 | 0.8432 |

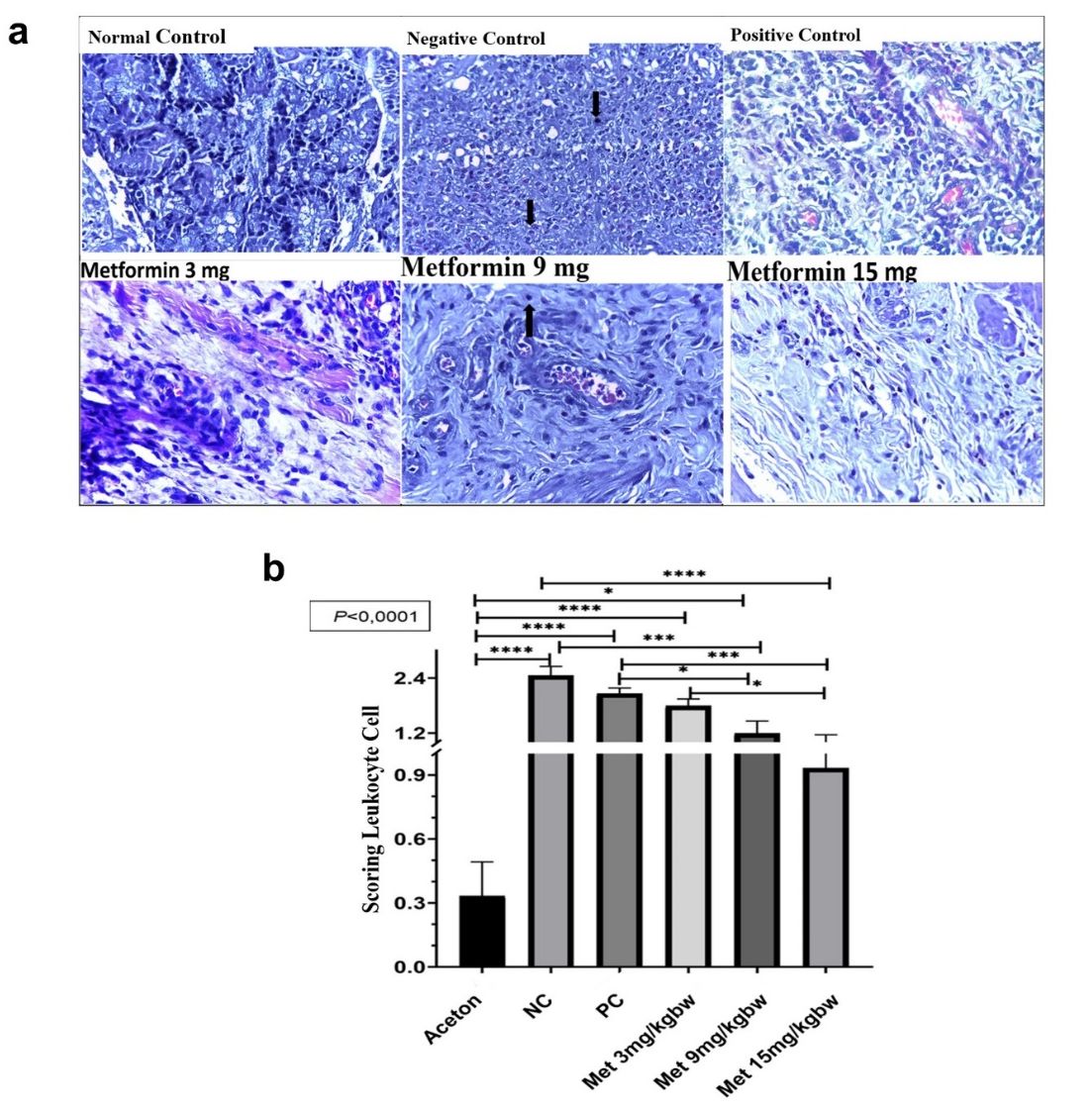

Histopathological analysis of infiltration leukocyte

In our analysis of leukocyte density across different treatment groups, we observed notable variations that highlight the effects of metformin and other interventions. The data revealed that the negative control group had the highest density of leukocyte cells in the tissue, indicating a strong inflammatory response. In contrast, the metformin-treated groups exhibited progressively lower leukocyte counts at doses of 3 mg/kg, 9 mg/kg, and 15 mg/kg (fig. 4A). Histopathological analysis showed that the normal control group had well-preserved tissue with minimal leukocyte infiltration. However, the negative control group displayed a significantly higher concentration of leukocytes, particularly in the area extending from the lumen to the dermis. The aspirin-treated group demonstrated a noticeable decrease in leukocyte dispersion compared to the negative control. Similarly, the 3 mg/kg metformin group had fewer leukocytes than the positive control, while the 9 mg/kg metformin group showed an even greater reduction. The 15 mg/kg metformin group exhibited the lowest leukocyte count among all treatment groups, suggesting a dose-dependent anti-inflammatory effect. These findings underscore metformin’s potential to mitigate inflammation by reducing leukocyte infiltration in hemorrhoid tissues.

Scoring of infiltration leukocyte cells in anorectal tissue experimental hemorrhoid

In evaluating the impact of metformin on leukocyte infiltration, we compared the control group with groups treated with different doses of metformin. Our analysis encompassed the control group and those receiving metformin at doses of 3 mg/kg, 9 mg/kg, and 15 mg/kg. The results of the ANOVA statistical test, which was conducted based on the normal distribution of the data, revealed significant differences among the groups (p-values of p<0.0001, p = 0.0001, p>0.01). The negative control group showed the highest leukocyte cell score, while the metformin groups exhibited dose-dependent reductions. The 15 mg/kg metformin group demonstrated the most significant reduction, suggesting that metformin effectively reduces leukocyte infiltration in anorectal tissue at higher doses (fig. 4B).

Fig. 4: Metformin treatment reduced leukocyte infiltration. (A) Representative images of leukocyte infiltration at 40x magnification using a light microscope. (B) Scoring of leukocyte cell infiltration in each group. All results are shown as mean±SD of triplicate experiments in each of the two independent experiments

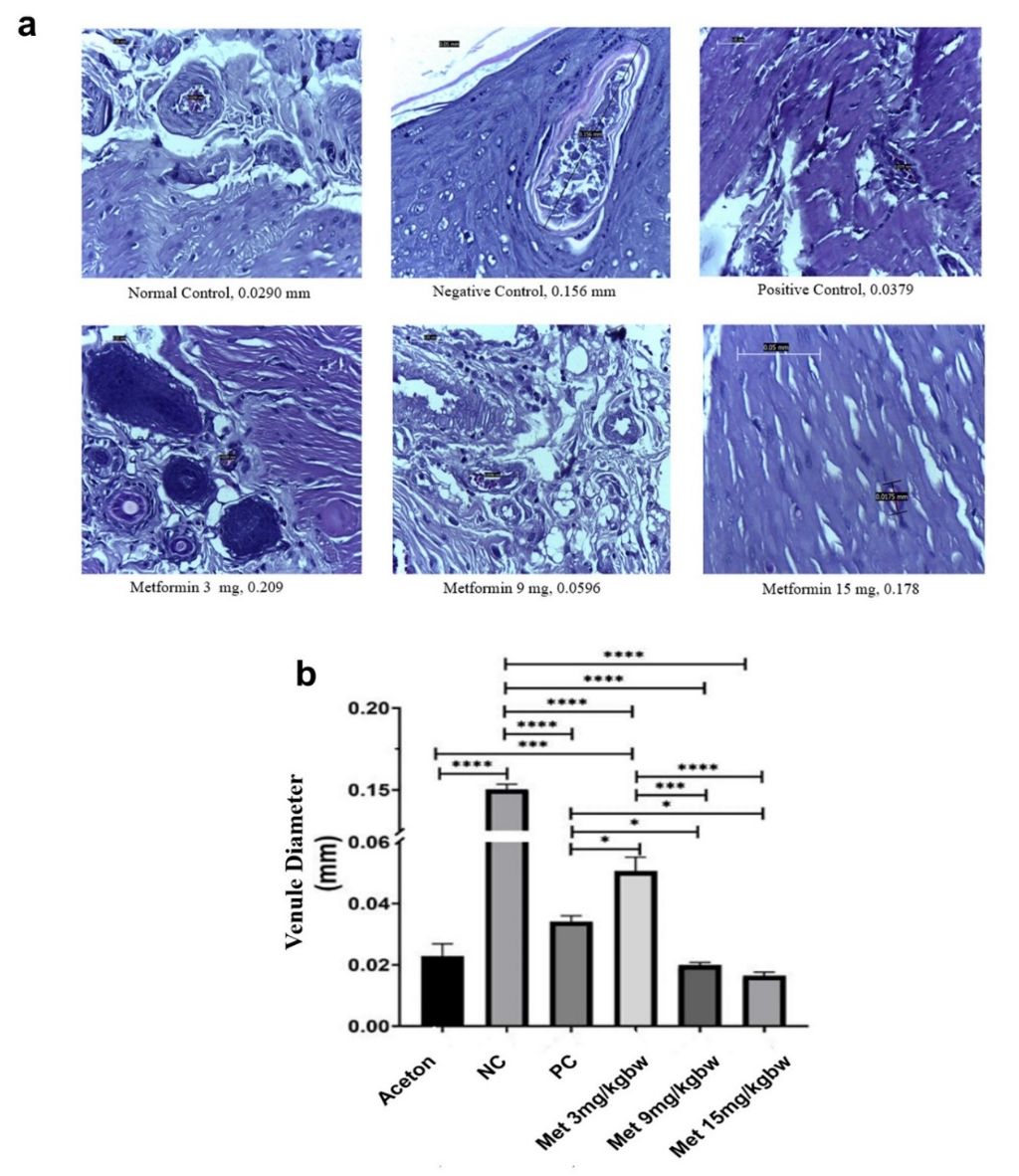

Histopathological analysis of venule blood vessel diameter size

Our histological analysis focused on measuring the venule blood vessel diameters in the anal tissue of rats under different treatment conditions (fig. 5A). In the normal control group, the venule blood vessels had an average diameter of 0.0290 mm, representing a healthy state without inflammation. In contrast, the negative control group, which represented untreated hemorrhoidal tissue, exhibited a significantly larger venule diameter of 0.156 mm, consistent with marked vasodilation commonly seen in hemorrhoid conditions. The positive control group, treated with aspirin, showed a reduced venule diameter of 0.0379 mm, which, although slightly larger than the normal control, was still considerably smaller than that of the negative control group.

To statistically assess these variations, an ANOVA test was performed to compare the venule diameters among all groups (fig. 5B). The test revealed significant differences, with a highly significant p-value (p<0.0001) indicating robust differences among most groups, a less significant result (p = 0.1), and a non-significant result (p>0.1), suggesting variability in response to the treatments.

The data demonstrated that the negative control group had the largest venule diameter among all groups, confirming the presence of inflammation. The group treated with 3 mg/kg of metformin had a venule diameter 49.72% larger than the normal control, indicating only partial mitigation of vasodilation. The positive control group, treated with aspirin, showed a venule diameter 20.75% larger than the normal control, suggesting moderate anti-inflammatory effects. In contrast, the group receiving 9 mg/kg of metformin exhibited a 7.92% reduction in venule diameter compared to the normal control, indicating a significant decrease in vascular inflammation. The 15 mg/kg metformin group demonstrated the greatest effect, with a 47% reduction in venule diameter, suggesting that higher doses of metformin are more effective in reducing vascular inflammation [25, 26]. Moreover, the contrast between metformin’s effect and aspirin’s suggests that metformin may have a more targeted action on vascular inflammation in hemorrhoid models. These insights add to the growing evidence that metformin could be a valuable treatment for vascular complications beyond its traditional use in diabetes management.

Fig. 5: Metformin treatment in hemorrhoid models reduces venule’s diameter. (A) Representative images of a diameter of venule blood vessels in anal tissue of rats. (B) ANOVA statistical analysis of venule blood vessel diameters across treatment groups. All results are shown as mean±SD of triplicate experiments in each of the two independent experiments

DISCUSSION

This study observed a significant reduction in the relative mRNA expression of TNF-α and IL-6, especially with a 9 mg/kg dose of metformin. This supports the hypothesis that metformin’s activation of AMPK inhibits NF-κB, thereby reducing pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α [27]. These results are consistent with the understanding that metformin’s anti-inflammatory effects are mediated through these pathways [28, 29]. Our previous bioinformatic study demonstrated that hemorrhoidal disease was characterized by an increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines, with IL-6 and TNF-α being the most prevalent cytokines [30].

Metformin also significantly reduced COX-2 mRNA expression across all doses tested. Although the reduction was consistent, the lack of significant differences among the doses suggests that higher doses or longer treatment durations may be necessary for more pronounced effects. This finding aligns with previous studies that indicated the need for extended or higher-dose treatments to fully realize metformin's anti-inflammatory potential [31-33].

Interestingly, metformin did not significantly affect IL-10 mRNA expression. This suggests that while metformin effectively reduces COX-2-mediated inflammation, it does not significantly influence IL-10-related anti-inflammatory pathways. This discrepancy might be attributed to metformin’s action through specific molecular pathways, such as AMPK and mTOR, which might not directly modulate IL-10 production [17, 34]. The differences in experimental conditions compared to studies like Kelly et al. (2015), which reported an increase in IL-10 with metformin treatment in LPS-activated macrophages, our study found no significant change in IL-10 levels [18]. This discrepancy may arise from differences in the pathological conditions between hemorrhoids and other inflammatory models, such as diabetes [27]. In terms of leukocyte infiltration, metformin treatment led to a dose-dependent reduction in leukocyte counts, with the 15 mg dose showing the lowest count. This reduction in leukocytes, a marker of inflammation, underscores metformin’s role in mitigating inflammatory responses in hemorrhoid tissues [35]. Metformin’s ability to reduce leukocyte adhesion by decreasing Intercellular Adhesion Molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and Vascular Adhesion Molecule-1 (VCAM-1) expression further underscores its anti-inflammatory potential [36].

Additionally, in non-hemorrhoid-induced rats, the venule blood vessel diameter was reduced, indicating healthy anal tissue. The negative control group of hemorrhoid model rats displayed a wider venule diameter, characteristic of inflammatory conditions [25, 26]. The 15 mg metformin dose proved most effective in reducing venule diameter, suggesting a dose-dependent effect on vascular inflammation. While our study provides valuable insights, it is limited by the duration of treatment and the specific dosages used. Future research should explore a broader range of doses and longer treatment durations to fully characterize metformin’s anti-inflammatory effects. Additionally, clinical trials are necessary to evaluate the effectiveness of metformin in human subjects with hemorrhoids and to confirm its potential as a therapeutic option.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, our findings indicate that metformin, particularly at higher doses, significantly reduces pro-inflammatory cytokine expression, leukocyte infiltration, and venule dilation in an experimental hemorrhoid model. These results suggest that metformin could be a promising therapeutic agent for managing hemorrhoid-related inflammation, warranting further investigation in clinical settings.

ETHICS APPROVAL

This study has obtained approval from the Animal Ethics Committee of Universitas Riau. All procedures involving animals were conducted in accordance with the guidelines and regulations set by the committee to ensure animal welfare and minimize pain and suffering. The experimental protocol was approved by the Unit of Ethics in Research of the Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Riau, with the number B/131/UN19.5.1.1.8/UEPKK/2023.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology of Indonesia (No. 1591/lL8/AL.04/2024).

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

D. D and W. A conceived and designed the study. D. D., W. A., L. M. I., B. L. N., S. S., N. A and M. Y. H., data curation. D. D., W. A., S. S and N. A formal analysis. D. D writing the original draft. W. A provided the funding. D. D., W. A., L. M. I., B. L. N., S. S., N. A., I. F. R., A. M. N. K and M. Y. H revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript and have made significant contributions to this study.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

Gupta S, Singh TG, Baishnab S, Garg N, Kaur K, Satija S, editors. Recent management of hemorrhoids: a pharmacological and surgical perspective; 2020.

Ray Offor E, Amadi S. Hemorrhoidal disease: predilection sites, pattern of presentation, and treatment. Ann Afr Med. 2019;18(1):12-6. doi: 10.4103/aam.aam_4_18, PMID 30729927, PMCID PMC6380113.

Al-Masoudi RO, Shosho R, Alquhra D, Alzahrani M, Hemdi M, Alshareef L. Prevalence of hemorrhoids and the associated risk factors among the general adult population in Makkah, Saudi Arabia. Cureus. 2024;16(1):e51612. doi: 10.7759/cureus.51612, PMID 38318578, PMCID PMC10840063.

Sardinas C, Arreaza DD, Osorio H. Changes in the proportions of types I and III collagen in hemorrhoids: the sliding anal lining theory. J Coloproctol. 2016;36(3):124-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcol.2016.04.003.

Sun Z, Migaly J. Review of hemorrhoid disease: presentation and management. Clin Colon Rect Surg. 2016;29(1):22-9. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1568144, PMID 26929748.

Sanchez C, Chinn BT. Hemorrhoids. Clin Colon Rect Surg. 2011;24(1):5-13. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1272818, PMID 22379400, PMCID PMC3140328.

Lohsiriwat V. Hemorrhoids: from basic pathophysiology to clinical management. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(17):2009-17. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i17.2009. PMID 22563187, PMCID PMC3342598.

Porwal A, Gandhi P, Kulkarni D. Laser hemorrhoidopexy: an observational study of 1088 patients treated at a single center. Indian J Colo Rect Surg. 2022;5(3):61-7. doi: 10.4103/ijcs.ijcs_28_21, PMID 02234691.

Ng KS, Holzgang M, Young C. Still a case of “no pain, no gain”? An updated and critical review of the pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management options for hemorrhoids in 2020. Ann Coloproctol. 2020;36(3):133-47. doi: 10.3393/ac.2020.05.04, PMID 32674545, PMCID PMC7392573.

Altomare DF, Giuratrabocchetta S. Conservative and surgical treatment of haemorrhoids. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10(9):513-21. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.91, PMID 23752820.

Zagriadskii EA, Bogomazov AM, Golovko EB. Conservative treatment of hemorrhoids: results of an observational multicenter study. Adv Ther. 2018;35(11):1979-92. doi: 10.1007/s12325-018-0794-x, PMID 30276625, PMCID PMC6223991.

Shah I, Vyas J. Role of P-GP inhibitors on gut permeation of metformin: an ex-vivo study. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2022;14(10):18-23. doi: 10.22159/ijpps.2022v14i10.45135.

Aleti R, Baratam SR, Jagirapu B, Kudamala S. Formulation and evaluation of metformin hydrochloride and gliclazide sustained release bilayer tablets: a combination therapy in management of diabetes. Int J Appl Pharm. 2021;13(5):343-50. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2021v13i5.41339.

Mussttaf GS, Habib A, Mahtook M. Drug prescribing pattern and cost-effectiveness analysis of oral antidiabetic drugs in patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus: real-world data from Indian population. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2021;14(7):45-9. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2021.v14i7.41677.

Tseng CH. Chronic metformin therapy is associated with a lower risk of hemorrhoid in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:578831. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.578831, PMID 33664665, PMCID PMC7921735.

Zhou J, Massey S, Story D, Li L. Metformin: an old drug with new applications. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(10):2863. doi: 10.3390/ijms19102863, PMID 30241400, PMCID PMC6213209.

Saisho Y. Metformin and inflammation: its potential beyond glucose-lowering effect. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2015;15(3):196-205. doi: 10.2174/1871530315666150316124019, PMID 25772174.

Kelly B, Tannahill GM, Murphy MP, O’Neill LA. Metformin inhibits the production of reactive oxygen species from NADH: ubiquinone oxidoreductase to limit induction of interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and boosts interleukin-10 (IL-10) in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-activated macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(33):20348-59. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.662114, PMID 26152715, PMCID PMC4536441.

Wang Q, Zhang M, Torres G, Wu S, Ouyang C, Xie Z. Metformin suppresses diabetes-accelerated atherosclerosis via the inhibition of Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission. Diabetes. 2017;66(1):193-205. doi: 10.2337/db16-0915, PMID 27737949, PMCID PMC5204316.

Karimi H, Asghari A, Jahandideh A, Akbari G, Mortazavi P. Effects of metformin on experimental varicocele in rats. Arch Razi Inst. 2021;76(2):371-84. doi: 10.22092/ari.2020.128136.1406, PMID 34223735, PMCID PMC8410191.

Nurul Qurrota A, Kusmardi, Nurhuda BE. Anti-inflammation of soursop leaves (Annona muricata L.) against hemorrhoids in mice induced by croton oil. Pharmacogn J. 2020;12(4).

Hutagalung MS. Phlebotrophic effect of graptophyllum pictum (L.) griff on experimental wistar hemorrhoids. J Biomed Transl Res. 2019;5(1). doi: 10.14710/jbtr.v5i1.3704.

Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402-8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262, PMID 11846609.

Wanchaitanawong W, Thinrungroj N, Chattipakorn SC, Chattipakorn N, Shinlapawittayatorn K. Repurposing metformin as a potential treatment for inflammatory bowel disease: evidence from cell to the clinic. Int Immunopharmacol. 2022;112:109230. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2022.109230, PMID 36099786.

Dey YN, Wanjari MM, Kumar D, Lomash V, Jadhav AD. Curative effect of Amorphophallus paeoniifolius tuber on experimental hemorrhoids in rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2016;192:183-91. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.07.042, PMID 27426509.

Fontem RF, Eyvazzadeh D. Internal hemorrhoid. Stat Pearls. Treasure Island, (FL); 2024.

Gallo G, Picciariello A, Tufano A, Camporese G. Clinical evidence and rationale of mesoglycan to treat chronic venous disease and hemorrhoidal disease: a narrative review. Update Surg. 2024;76(2):423-34. doi: 10.1007/s13304-024-01776-9, PMID 38356039, PMCID PMC10995001.

Kaidar Person O, Person B, Wexner SD. Hemorrhoidal disease: a comprehensive review. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204(1):102-17. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.08.022, PMID 17189119.

Ahmadu AA, Zezi AU, Yaro AH. Anti-diarrheal activity of the leaf extracts of daniellia oliveri hutch and dalz (Fabaceae) and ficus sycomorus miq (Moraceae). Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2007;4(4):524-8. doi: 10.4314/ajtcam.v4i4.31246, PMID 20161921, PMCID PMC2816518.

Adikusuma W, Firdayani F, Irham LM, Darmawi D, Hamidy MY, Nopitasari BL. Integrated genomic network analysis revealed potential of a druggable target for hemorrhoid treatment. Saudi Pharm J. 2023;31(12):101831. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2023.101831, PMID 37965490, PMCID PMC10641558.

Kulkarni AS, Gubbi S, Barzilai N. Benefits of metformin in attenuating the hallmarks of aging. Cell Metab. 2020;32(1):15-30. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.04.001, PMID 32333835, PMCID PMC7347426.

Shi B, Hu X, He H, Fang W. Metformin suppresses breast cancer growth via inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2. Oncol Lett. 2021;22(2):615. doi: 10.3892/ol.2021.12876, PMID 34257723, PMCID PMC8243079.

Lin H, Ao H, Guo G, Liu M. The role and mechanism of metformin in inflammatory diseases. J Inflamm Res. 2023;16:5545-64. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S436147, PMID 38026260, PMCID PMC10680465.

Cameron AR, Morrison VL, Levin D, Mohan M, Forteath C, Beall C. Anti-inflammatory effects of metformin irrespective of diabetes status. Circ Res. 2016;119(5):652-65. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308445, PMID 27418629, PMCID PMC4990459.

Apostolova N, Iannantuoni F, Gruevska A, Muntane J, Rocha M, Victor VM. Mechanisms of action of metformin in type 2 diabetes: effects on mitochondria and leukocyte-endothelium interactions. Redox Biol. 2020;34:101517. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101517, PMID 32535544, PMCID PMC7296337.

Sigit Adi P, Parish B, Ignatius R. Ch. 3. Prolapsing hemorrhoids. In: Alberto V, Daniela Cornelia L, editors. Benign anorectal disorders. Rijeka: IntechOpen; 2022.