Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 2, 2025, 268-280Original Article

IN SILICO EVALUATION OF CSF1R INHIBITORS: A PROMISING APPROACH FOR TARGETING NEUROINFLAMMATION IN NEURODEGENERATIVE DISEASES

ATHIRA SASIDHARAN1, DEEPTHI K2 , SHESHAGIRI DIXIT3

, SHESHAGIRI DIXIT3 , DEEPSHIKHA SINGH4

, DEEPSHIKHA SINGH4 , VEENA V TOM1

, VEENA V TOM1 , YOGISH SOMAYAJI5

, YOGISH SOMAYAJI5 , RONALD FERNANDES2*

, RONALD FERNANDES2*

1Department of Allied Health Sciences, NGSM Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Nitte (Deemed to be University), Mangalore-575018, Karnataka, India. 2Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, NGSM Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Nitte (Deemed to be University), Mangalore-575018, Karnataka, India. 3Computer Aided Drug Design Laboratory, Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, JSS College of Pharmacy Mysore, JSS Academy of Higher Education and Research, Mysore-570015, Karnataka, India. 4Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, JSS College of Pharmacy Mysore, JSS Academy of Higher Education and Research, Mysore-570015, Karnataka, India. 5Department of Post Graduate Studies and Research in Biochemistry, St. Aloysius College (Autonomous), Mangaluru-575003, Karnataka, India

*Corresponding author: Ronald Fernandes; *Email: ronaldfernandes@nitte.edu.in

Received: 17 Dec 2024, Revised and Accepted: 04 Feb 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: This study investigates the therapeutic potential of Colony Stimulating Factor 1 Receptor (CSF1R) inhibitors in targeting neuroinflammation, focusing on the modulation of the JNK/NLRP3/IL-1β signaling pathway, a key axis contributing to neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric diseases.

Methods: In silico docking analyses were conducted to evaluate the interactions between CSF1R inhibitors and pivotal inflammatory proteins (JNK, NLRP3, IL-1β). Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations assessed the stability and conformational dynamics of the ligand-protein complexes. The inhibitors' physicochemical and ADME profiles and toxicity characteristics were analyzed using QikProp and computational toxicity prediction tools.

Results: The docking studies demonstrated that BLZ945 exhibits superior binding affinities with docking scores of-11.107 kcal/mol for JNK, -9.870 kcal/mol for NLRP3, and -4.872 kcal/mol for IL-1β, surpassing other inhibitors such as chiauranib and pexidartinib. ADME analysis revealed that BLZ945 has favorable drug-like properties, including high oral bioavailability (94.025%) and effective blood-brain barrier penetration (QPlogBB:-1.159). Toxicity evaluations confirmed its low toxicity profile, positioning it as a safer candidate compared to edicotinib and ARRY382. MD simulations further validated the stability of BLZ945 in complex with JNK and NLRP3, showing minimal root mean square deviation (RMSD: 2.38–3.55 Å) and strong hydrophobic interactions with key residues.

Conclusion: The findings highlight BLZ945 as a promising CSF1R inhibitor for modulating the JNK/NLRP3/IL-1β pathway, offering potential therapeutic benefits for neuroinflammation-related disorders. Its high binding affinities, favorable ADME properties, and stable interactions in MD simulations underscore its suitability for further experimental validation in neurodegenerative disease models.

Keywords: CSF1R inhibitors, Neuroinflammation, JNK/NLRP3/IL-1β pathway, In silico docking, Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, ADME characteristics

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i2.53425 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Multiple sclerosis, Huntington's disease, Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease, and autism spectrum disorders are among the many neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric conditions that exhibit neuroinflammation [1]. Effective treatment approaches are desperately needed to counteract the effects of this chronic neuroinflammation, which disturbs neuronal homeostasis and accelerates neurodegeneration [2]. The NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome [3], c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) [4], and interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) [5] are important molecular drivers of neuroinflammation that contribute to neuronal injury and amplify inflammatory responses.

The JNK signaling pathway and the NLRP3 inflammasome are increasingly recognized as pivotal in the development of neurodegenerative diseases [6, 7]. JNK, a stress-activated protein kinase highly expressed in the brain, is activated in response to environmental challenges such as oxidative damage and ischemic injury [8, 9]. Its regulatory role in inflammation and cell death is crucial to the neuronal dysfunction seen in both circumstances, making it an important target for studying and treating neuroinflammation [10]. The development of several neurodegenerative diseases is closely linked to the dysregulation of JNK signaling [9]. Similarly, pathogenic and stress-related signals activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, which plays a crucial role in mediating innate immune responses [11]. When it is activated, caspase-1 is cleaved, which causes the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β. This exacerbates neurodegenerative disease and prolongs inflammatory cascades [12, 13].

Recent research has highlighted the important role of microglial dysregulation in maintaining neuroinflammatory states in neurodegenerative diseases [14]. Microglia, the CNS's resident immune cells, play a critical role in neuronal health under physiological settings. However, their continuous activation promotes a pro-inflammatory environment that exacerbates neurodegeneration [15]. The Colony Stimulating Factor 1 Receptor (CSF1R), a tyrosine kinase receptor involved in microglial proliferation and survival, has emerged as a viable therapeutic target. CSF1R inhibitors, including pexidartinib, edicotinib, and BLZ945, have been shown to reduce neuroinflammatory responses by modifying microglial activation [16, 17]. Animal models of neurodegenerative diseases have provided convincing evidence for their ability to block disease development, emphasizing the importance of these inhibitors in treating neuroinflammation-related pathologies [18].

Limited studies have examined the relationship between CSF1R inhibitors and major neuroinflammatory pathways like the JNK/NLRP3/IL-1β axis. This work closes that gap by using in silico docking analyses to assess the interaction of CSF1R inhibitors with these important targets. The motivation for concentrating on this route arises from its critical function in enhancing inflammatory cascades and inducing neuronal damage in neurodegenerative diseases. The study employed in silico docking to evaluate CSF1R inhibitors targeting the JNK/NLRP3/IL-1β pathway, pivotal in neuroinflammation. This study aims to find interesting lead compounds that can be optimized for the treatment of diseases linked to neuroinflammation by investigating the molecular interactions between these inhibitors and important inflammatory proteins. The findings are expected to aid in the development of targeted treatments that address the underlying causes of neuroinflammation and the disorders that are associated with it.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Docking studies

The physicochemical and ADMET features of the chosen CSF1R inhibitors were ascertained through computational analysis performed on Maestro version 13.5.128, MMshare Version 6.1.128, Release 2024-2, with Linux-x86_64operating system.

Ligand preparation

DCC-3014 (CID 86267612), BLZ945 (CID 46184986), CHIAURANIB (CID 49779393), ARRY-382 (SID 355048354), DOVITINIB (CID 135398510), PEXIDARTINIB (CID 25151352), EDICOTINIB (CID 25230468), and SORAFENIB (CID 216239) were all retrieved from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI)-RSCB PubChem Database using the Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES). These inhibitors were chosen based on previous evidence of efficacy as CSF1R inhibitors and availability in public databases [19–21]. We obtained the CSF1R inhibitors' SMILES from PubChem. Using Schrödinger software, the SMILES were imported into Maestro. The preparation of ligands is done using the Schrödinger module LigPrep (https://www.schrodinger.com/ platform/products/ligprep/). It adds or removes hydrogen ions from the ligands to neutralize their charged groups. Before ionization states may be produced, this step is required. To produce a clean and representational structure of the ligand, it eliminates extra molecules, such as water molecules and counter ions in salts. LigPrep removes several tautomeric molecular types. 3D structures are created from the prepared ligands in 2D structures [21, 22].

Physicochemical properties

Using Schrödinger's QikProp software, the physicochemical characteristics of the ligand molecules were determined. The scores aid in understanding bioavailability and drug-likeness characteristics. After being prepared, the ligands were chosen, added to the QikProp tool, and processed. Physicochemical characteristics such as molecular weight, donor HB (hydrogen bond), acceptor HB analyses, QPlogPo/w (predicted octanol/water partition coefficient), and Lipinski's Rule of Five were evaluated [23].

ADME properties

Schrödinger program (Schrödinger 2020-4: Qik-Prop) was used to determine the ADME properties of ligand molecules using QikProp. It offers a comprehensive set of descriptors for evaluating pharmacokinetic and drug-likeness properties and bioavailability [24]. After being prepared, the ligands were chosen, added to the QikProp tool, and processed. The blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability, Caco-2 cell permeability, percentage human oral absorption, solvent accessible surface area (SASA), hydrophobic and hydrophilic components of SASA, plasma–protein binding, metabolism, and the Half Maximal Inhibitory Concentration (IC50) value for the Human Ether-À-Go-Go-Related Gene Potassium Channel (HERG K+) are among the characteristics of ADMET. This method enables a researcher to concentrate on just those specific substances that require additional analysis [25].

Toxicity prediction

pkCSM, ProTox-II, and Osiris Property Explorer were the three tools used to realistically anticipate the phytoconstituents' toxicity. The platform pkCSM (https://biosig.lab.uq.edu.au/pkcsm/) offers a user-friendly, open-source web interface for the analysis and optimization of pharmacokinetic and toxicological parameters [26, 27]. ProTox-II (https://tox.charite.de/protox3/) is a free virtual laboratory that predicts small molecule toxicities by comparing the compound's similarities to known hazardous chemicals [16]. Tumorigenicity, mutagenicity, reproductive effects, and irritating effects were among the toxicity parameters that were examined using the Osiris Property Explorer (https://www.organic-chemistry.org/prog/peo). The results are expressed using values and color codes [22]. For every compound, a distinct SMILES string was pasted and submitted. Using pkCSM, AMES toxicity was predicted. Using ProTox-II, the estimated lethal dose, 50% (LD 50), and toxicity class were determined [28].

Protein preparation

The Protein Data Bank (PDB) (https://www.rcsb.org/) provided the X-ray crystal structures of the JNK, NLRP3, and IL-1β enzymes, identified by their PDB IDs 3E7O, 7ALV, and 5R8Q. The resolutions of target proteins 2.14A (3E7O), 2.83A (7ALV), and 1.23A (5R8Q) were considered good for further analysis. These structures were selected because they are highly relevant to the study’s focus on neuroinflammation, offering high-resolution data on proteins involved in key inflammatory pathways.

Schrödinger's Protein Preparation Wizard was used to import the proteins' 3D structures. Using the required modeling calculations of Schrödinger software, the protein structures were prepared to ensure they were in a suitable form for docking studies. The wizard fixed bond ordering, adjusted formal charges, added the missing protons, treated metal ions, and removed water molecules, thereby ensuring a complete and accurate protein model [29, 30]. Energy minimization was performed to resolve steric clashes and stabilize the protein in a low-energy conformation, ensuring that the protein structure was suitable for docking.

To further enhance the accuracy, Epik was used to generate potential ionization states for the ligand-binding sites of the protein. The most stable ionization state was selected to ensure biological relevance and maintain structural integrity during the docking process. These preprocessing steps were validated by comparing the refined structures with their original experimental data from the PDB, ensuring the accuracy and stability of the protein models for ligand docking. We used the Receptor Grid Generation Wizard to generate a grid for molecular docking. To do this, a three-dimensional grid encircling the protein's active region, where ligands are to dock must be established. The last stage was docking the ligands using the Glide extra precision (XP) scoring tool. The Glide XP tool makes it possible to assess ligand binding to the receptor with more accuracy [31].

Molecular docking

The Glide docking technique (https://www.schrodinger.com/ platform/products/glide/) is used to dock the ligand to the protein binding site. Glide employs a scoring algorithm to assess and rank various ligand poses based on projected binding affinities. The scoring function evaluates the interaction of the ligand and protein. In the XP mode, we investigate docking positions. Numerous interactions are examined by the software, including hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions, metal-ligation interactions, and steric conflicts. The nature of the interactions between ligands and proteins is clarified by this stage. The final scoring is done with the Glide Score function [30].

Molecular mechanics/Generalized born surface area (MM-GBSA)

Prime MM-GBSA is used to determine the free energy of protein-ligand complex binding (https://www.schrodinger.com/platform/ products/prime/). It uses force fields from molecular mechanics and continuum solvation models to calculate the energy changes associated with ligand binding to a protein receptor. After taking into account any entropy contributions and the solvation-free energy, the binding free energy, or ΔG bind, is calculated by subtracting the complex's energy from the energies of the separated protein and ligand [32].

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation

MD simulation was carried out utilizing the Schrodinger suite's Desmond module. Based on the docking score, the compound BLZ945 was chosen for further MD simulation research. To test compound BLZ945's stability in a complex with 3E70 and 7ALV, a 100-ns MD simulation was performed on an explicit hydration environment. The MD simulation data were assessed using root mean square deviation (RMSD), root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), protein-ligand contact mapping, and ligand-protein contacts. Throughout the trajectory analysis, the average displacement of a collection of atoms in each frame relative to a reference frame is determined using the RMSD, which provides information about structural changes over time. Tracking the RMSD of the protein during simulation can provide structural conformation information [33].

Ligand RMSD indicates the ligand's stability with the protein and its binding pocket. The RMSF is useful for detecting local changes in the protein chain. The interactions between the enzymes 3E70 and 7ALV, as well as the ligand BLZ945, may be followed throughout the simulation. The 'Simulation Interactions Diagram' tab allows you to explore more detailed subtypes within each interaction type.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Physicochemical properties

The physicochemical properties of the ligands were evaluated using QikProp to determine their drug-likeness based on Lipinski's Rule of Five. Table 1 lists the physicochemical characteristics of the CSF1R inhibitors. All of the ligands that were examined had molecular weights that were within the 130.0–725.00 range, adhering to Lipinski's guidelines. Several chemical characteristics were used by Lipinski to create his "Rule of Five". Most molecules with good drug similarity, according to the rule, have logP less than or equal to 5, molecular weight less than or equal to 500, less than or equal to five donors, and fewer than or equal to 10 HB acceptors [34]. The Lipinski "Rule of Five" is stated to be followed by compounds that meet at least three of the four requirements [35]. Six inhibitors, BLZ945, SORAFENIB, DOVITINIB, CHIAURANIB, DCC-3014, and EDICOTINIB, were determined to comply with Lipinski's Rule of Five without any violations. Further investigation revealed that PEXIDARTINIB and ARRY382 violated one rule, indicating that they are classified as drug-like compounds, and the violations were likely caused by the ligands' complicated structures. The reference compound indomethacin was determined to comply with Lipinski's Rule of Five without any violations.

Table 1: Physiochemical properties of CSF1R inhibitors

| S. No. | Ligand ID | Molecular weight (<500 Da) | QPlogPo/w (<5) | Donor HB (≤ 5) | Accept HB (≤10) | Rule of five |

| 1 | BLZ945 | 398.479 g/mol | 3.142 | 3.000 | 7.700 | 0 |

| 2 | Pexidartinib | 417.820 g/mol | 5.538 | 2.000 | 3.500 | 1 |

| 3 | Sorafenib | 464.831 g/mol | 4.110 | 3.000 | 6.000 | 0 |

| 4 | Dovitinib | 392.435 g/mol | 2.635 | 2.500 | 7.000 | 0 |

| 5 | Chiauranib | 435.481 g/mol | 4.929 | 2.500 | 5.750 | 0 |

| 6 | ARRY382 | 564.689 g/mol | 4.828 | 1.000 | 10.750 | 1 |

| 7 | DCC-3014 | 431.496 g/mol | 4.238 | 1.000 | 8.500 | 0 |

| 7 | Edicotinib | 461.606 g/mol | 4.803 | 2.000 | 7.250 | 0 |

| 8 | Indomethacin | 357.793 g/mol | 4.267 | 1.000 | 5.750 | 0 |

ADME properties

QikProp's evaluation of the ADME properties aided in determining the compound's early-phase action and capacity to penetrate biological barriers. By studying ADME properties, medicinal chemists can find areas for improvement in the compound's activity. The results are summarized in Tables 2 and 3. Tables 2 and 3 highlight the findings of QikProp, which also offered insights into bioavailability, BBB penetration, plasma protein binding, metabolism, and SASA.

Prediction of bioavailability

Oral absorption is measured by the predicted aqueous solubility, logS, the predicted percentage of human oral absorption, and adherence to Jorgensen's renowned, well-known "Rule of Three." According to Jorgensen's RO3, compounds that meet al. l or some of these criteria (logS>-5.7, Caco-2>22 nm/s, and # Primary Metabolites<7) are more likely to be absorbed orally [36]. The CSF1R inhibitors BLZ945, Dovitinib, and ARRY382 have log S values that vary from -6.5 to 0.5, indicating good aqueous solubility. BLZ945 showed strong aqueous solubility, with a QPlogS value of -5.717, which is near the RO3 limit. Pexidartinib and chiauranib had intermediate aqueous solubility; however, drugs like sorafenib (-7.079) and edicotinib (-8.838) had lesser solubility, requiring possible solubility augmentation strategies. Indomethacin has a log S value of -5.116, which indicates good aqueous solubility.

Caco-2 cell permeability was used to assess nonactive transport across the gut-blood barrier. Compounds such as BLZ945, pexidartinib, chiauranib, and DCC-3014 have QPPCaco values of more than 500 nm/s, indicating good permeability across the gut-blood barrier. The remaining compounds demonstrated adequate permeability. Indomethacin also demonstrated adequate permeability with values ranging between 300 and 500 nm/s. Indomethacin displayed moderate permeability with a QPPCaco value of 150.434 nm/s, highlighting its lesser efficiency compared to BLZ945.

DOVITINIB was found to comply with Jorgensen's RO3 without any violations, while most CSF1R inhibitors violated one or two requirements but never all three, indicating that they are orally bioavailable. Indomethacin, the reference compound, was similarly determined to comply with Jorgensen's RO3 without violating it. In addition, all CSF1R inhibitors, except for ARRY382, all CSF1R inhibitors were absorbed more than 80% orally in humans. ARRY382 demonstrated acceptable values, ranging from 25 to 80%, indicating the need for formulation changes to improve bioavailability.

Highly polar drugs cannot pass the BBB. To predict central nervous system access, blood-brain partition coefficients (logB/B) were determined. QPlogBB was used to measure the amount of chemicals entering the central nervous system. All CSF1R inhibitors, including BLZ945 and the reference drug indomethacin, fell within the optimum range of-3.0 to-1.2, indicating significant capacity to permeate the BBB. BLZ945 obtained the best QPlogBB score (-1.159), indicating a high potential for CNS activation. Conversely, edicotinib had the least favorable QPlogBB score (-1.202), although still within the acceptable range. Overall, the ADME profile of BLZ945 demonstrates great bioavailability, high gut permeability, and powerful CNS penetration, making it a better candidate than other CSF1R inhibitors and the reference drug indomethacin. Despite mild solubility issues, certain inhibitors, such as sorafenib, prodrug formulations, and excipient modification, can be used to increase drug-like characteristics.

Prediction of dermal penetration

The log Kp value predicts skin permeability and should lie between-8.0 and -1.0. All CSF1R inhibitors were found to be within the acceptable range, indicating good skin penetration. Among them, edicotinib had a log Kp value closest to -1.0, indicating optimal dermal penetration, but BLZ945 and ARRY382, with higher negative values, exhibited slightly decreased but still acceptable skin permeability.

Prediction of plasma-protein binding

Drug binding to plasma proteins lowers the free drug concentration in the bloodstream, lowering its efficacy. The extent of this interaction is determined by plasma-protein binding as measured by the logKhsa parameter (optimal range:-1.5 to 1.5). All of the tested chemicals were found to be within permissible limits, indicating that they are likely to reach their target areas effectively via the bloodstream. Additionally, edicotinib had the maximum binding affinity with a logKhsa value of 1.132, suggesting a robust interaction with plasma proteins, whereas the reference drug, indomethacin, had the lowest binding affinity with a logKhsa value of 0.057.

Prediction of SASA, FOSA, FISA

SASA represents the total contact area between a solvent and a molecule, ranging from 300.0 to 1000.0 Å [37]. All CSF1R inhibitors, including the reference drug indomethacin, have SASA values in this range, indicating suitable molecular sizes for biological interactions. Among the inhibitors, ARRY382 had the greatest SASA value (988.354 Å), whereas indomethacin had the lowest (595.550 Å), suggesting a reduced surface area. FOSA, the hydrophobic component of SASA, should be in the range of 0.0 to 750.0. BLZ945 had the highest hydrophobic surface area with an FOSA value of 298.536 Å, potentially enhancing lipophilic interactions. Pexidartinib and sorafenib had lower FOSA values (83.455 Å and 97.431 Å, respectively), indicating a more balanced hydrophobic-hydrophilic interaction profile. FISA, the hydrophilic component of SASA, should range from 7.0 to 330.0 [37]. All CSF1R inhibitors, including the reference drug, were reported to have FISA values within this range, exceeding 7.0 but remaining less than 330.0.

Prediction of metabolism

All CSF1R inhibitors, including the reference drug indomethacin, are within the recommended range (1-8 reactions) of #metab, which indicates the number of metabolic reactions that may occur. This suggests that these compounds are biologically stable and unlikely to undergo significant metabolic breakdown. BLZ945 and DCC-3014, with three metabolic processes each, had moderate metabolic processing, but sorafenib and dovitinib, with just two metabolic reactions, were even more stable. ARRY382, with six responses, displayed a greater degree of metabolic activity while remaining within the acceptable range.

Table 2: Bioavailability properties of CSF1R inhibitors

| S. No. | Ligand ID | QPlogS (–6.5 – 0.5) |

QPPCaco (>500) |

RO3 | %Human oral absorption (>80%) |

QPlogBB (–3.0 – 1.2) |

#Metabolic reactions (1 – 8) |

| 1 | BLZ945 | -5.717 | 524.601 | 1 | 94.025 | -1.159 | 3 |

| 2 | PEXIDARTINIB | -7.239 | 1345.451 | 1 | 100.000 | -0.224 | 5 |

| 3 | SORAFENIB | -7.079 | 322.698 | 1 | 95.913 | -0.983 | 2 |

| 4 | DOVITINIB | -4.853 | 133.039 | 0 | 80.390 | -0.419 | 2 |

| 5 | CHIAURANIB | -6.782 | 873.853 | 1 | 100.000 | -1.024 | 5 |

| 6 | ARRY382 | -6.262 | 95.048 | 1 | 77.655 | -0.202 | 6 |

| 7 | DCC-3014 | -6.829 | 1236.871 | 1 | 100.000 | -0.841 | 3 |

| 7 | EDICOTINIB | -8.838 | 410.267 | 1 | 100.000 | -1.202 | 4 |

| 8 | INDOMETHACIN | -5.116 | 150.434 | 0 | 90.902 | -0.709 | 3 |

Table 3: ADME properties of the phytoconstituents

| S. No. | Ligand ID | QPlogKp (–8.0 – –1.0) |

QPlogKhsa (–1.5 – 1.5) |

SASA (300.0 – 1000.0) |

FOSA (0.0 – 750.0) |

FISA (7.0 – 330.0) |

| 1 | BLZ945 | -2.585 | 0.175 | 720.187 | 298.536 | 134.564 |

| 2 | PEXIDARTINIB | -1.622 | 0.866 | 680.892 | 83.455 | 91.430 |

| 3 | SORAFENIB | -2.343 | 0.327 | 769.717 | 97.431 | 140.750 |

| 4 | DOVITINIB | -4.958 | 0.404 | 681.646 | 231.819 | 133.800 |

| 5 | CHIAURANIB | -1.043 | 0.787 | 757.618 | 92.867 | 111.195 |

| 6 | ARRY382 | -5.180 | 0.944 | 988.354 | 540.981 | 85.601 |

| 7 | DCC-3014 | -1.767 | 0.513 | 803.170 | 415.867 | 95.284 |

| 8 | EDICOTINIB | -3.345 | 1.132 | 815.394 | 506.637 | 145.822 |

| 9 | INDOMETHACIN | -2.723 | 0.057 | 595.550 | 171.677 | 128.878 |

Toxicity prediction

The CSF1R inhibitors' in silico toxicity was determined using online tools. The AMES was discovered using pkCSM, whereas the LD50 and toxicity class were found using the ProTox-II online software. The Osiris Property Explorer was used to examine toxicity criteria such as tumorigenicity, mutagenicity, reproductive impacts, and irritating effects. Table 4 summarizes the properties.

Acute toxicity studies were carried out to investigate the toxicological profile of CSF1R inhibitors. The Ames toxicity test is a well-known in vitro bacterial mutagenicity assay used to assess the genotoxic potential of compounds [38, 39]. BLZ945's lack of mutagenicity is consistent with its positive safety profile, making it a potential candidate. In contrast, pexidartinib and dovitinib tested positive for mutagenicity, emphasizing possible concerns associated with their use that may demand care or structural alterations to decrease genotoxicity. The reference drug indomethacin produced negative results, confirming its previously established safety profile in this regard.

The toxic dose is commonly expressed as the LD50 value in mg/kg body weight. The median lethal dose (LD50) is the dose at which 50% of test subjects die following exposure to a substance. The Globally Harmonized Chemical Labeling Classification System (GHS) establishes toxicity class. The lower the class of the substance, the more poisonous it is. The LD50 value for Edicotinib is 4 mg/kg, making it very hazardous and classified as class I (LD50<5), meaning it is lethal if consumed. This finding indicates a high level of acute toxicity, rendering it inappropriate for oral delivery without major structural changes or other dosage regimens. BLZ945, Sorafenib, ARRY382, DCC-3014, Pexidartinib, and Dovitinib have LD50 values ranging from 800 to 1072 mg/kg and are classed as class 4 (300<Category 4 ≤ 2000 mg/kg/day), indicating that they are minimally hazardous if swallowed and hence deemed safe. BLZ945, with an LD50 value of 1000 mg/kg, displayed safety equivalent to most other inhibitors in this category, underlining its drug-like qualities. The LD50 value for Chiauranib is 8000 mg/kg, which is deemed non-toxic and expected to be in class 6 (LD50>5000), indicating that it is non-toxic and safe. This amazing finding emphasizes Chiauranib's translational potential for therapeutic uses, particularly where safety is paramount. However, its red signal for tumorigenicity creates long-term safety concerns, restricting its usage. The reference drug indomethacin, with an LD50 of 12 mg/kg, is classified as class 2, indicating moderate toxicity within tolerable therapeutic ranges.

Using the Osiris property explorer, molecules can be predicted based on their functional groups. The findings are shown in three colors: red, yellow, and green. Red color indicates a high risk of toxicity, yellow is a medium risk, and green is a low risk [40]. The data show that all compounds, except Chiauranib, ARRY382, and Edicotinib, are regarded safe because they have a green color, which indicates no toxicity in terms of tumorigenicity, mutagenicity, irritability, or reproductive damage. The compounds have acceptable drug scores. Chiauranib is marked in red for tumorigenicity, indicating a significant risk of toxicity indicating a high long-term danger; this raises concerns regarding its applicability for chronic conditions that need sustained exposure. ARRY382 has a yellow color for mutagenicity, which indicates a moderate risk; however, Edicotinib has a red color for irritating effects, indicating a high level of toxicity, further complicating its use in therapeutic settings. BLZ945's entirely green toxicity profile underscores its safety and positions it as a leading candidate among the CSF1R inhibitors.

BLZ945 stands out as a good candidate due to its low mutagenicity, high LD50, and low toxicity, making it appropriate for clinical testing. Chiauranib, while safe in acute toxicity studies, has tumorigenicity risks that need further investigation. Edicotinib's high toxicity and irritancy raise concerns, and structural alterations will probably be required before development. Overall, BLZ945's superior safety profile provides it a higher chance of effective clinical application than the others.

Table 4: Toxicity prediction of the CSF1R inhibitors

| S. No. | Ligands | AMES toxicity | Rat oral acute toxicity | Predicted LD50 | Predicted toxicity class | Toxicity | |||

| (Yes/No) | (mol/kg) | (mg/kg) | Tumorigenic | Reproductive effect | Irritant effect | Mutagenicity | |||

| 1 | BLZ945 | NO | 2.554 mol/kg | 1000 mg/kg | 4 | Green | Green | Green | Green |

| 2 | PEXIDARTINIB | YES | 2.963 mol/kg | 840 mg/kg | 4 | Green | Green | Green | Green |

| 3 | SORAFENIB | NO | 2.14 mol/kg | 800 mg/kg | 4 | Green | Green | Green | Green |

| 4 | DOVITINIB | YES | 2.408 mol/kg | 1072 mg/kg | 4 | Green | Green | Green | Green |

| 5 | CHIAURANIB | NO | 3.151 mol/kg | 8000 mg/kg | 6 | Red | Green | Green | Green |

| 6 | ARRY382 | NO | 2.478 mol/kg | 1000 mg/kg | 4 | Green | Green | Green | Yellow |

| 7 | DCC-3014 | NO | 2.75 mol/kg | 800 mg/kg | 4 | Green | Green | Green | Green |

| 8 | EDICOTINIB | NO | 2.534 mol/kg | 4 mg/kg | 1 | Green | Green | Red | Green |

| 9 | INDOMETHACIN | NO | 2.39 mol/kg | 12 mg/kg | 2 | Green | Green | Green | Green |

Molecular docking

The docking study analyzed the interaction of CSF1R inhibitors, including the reference drug indomethacin, against three target proteins: JNK (3E7O), NLRP3 (7ALV), and IL-1β (5R8Q). The binding affinities were evaluated using docking scores, with lower scores suggesting stronger binding interactions. The results, which are described in tables 5 and 6 revealed that BLZ945 outperformed indomethacin and other inhibitors across all three targets, demonstrating consistently superior binding affinities. Other inhibitors, including chiauranib and pexidartinib, have favorable interaction profiles but are less efficacious than BLZ945. Compounds like sorafenib and dovitinib performed moderately, whilst edicotinib had the weakest binding interactions, indicating limited promise. Overall, BLZ945 was the best-performing ligand, making it an ideal option for future experimental validation in neuroinflammatory pathways.

Table 5: Docking score of CSF1R inhibitors with target proteins 3E7O, 7ALV and 5R8Q

| S. No. | Ligands | Docking score (kcal/mol) | ||

| PDB ID | ||||

| 3E7O | 7ALV | 5R8Q | ||

| 1 | BLZ945 | -11.107 | -9.870 | -4.872 |

| 2 | PEXIDARTINIB | -8.178 | -6.517 | -6.167 |

| 3 | SORAFENIB | -6.619 | -5.464 | -2.674 |

| 4 | DOVITINIB | -8.444 | -7.446 | -2.742 |

| 5 | CHIAURANIB | -9.427 | -5.975 | -4.881 |

| 6 | ARRY382 | -7.882 | -5.722 | -2.083 |

| 7 | DCC-3014 | -5.444 | -4.186 | -3.492 |

| 8 | EDICOTINIB | -4.653 | -0.046 | -2.619 |

| 9 | INDOMETHACIN | -8.189 | -5.299 | -4.893 |

Binding with 3E7O

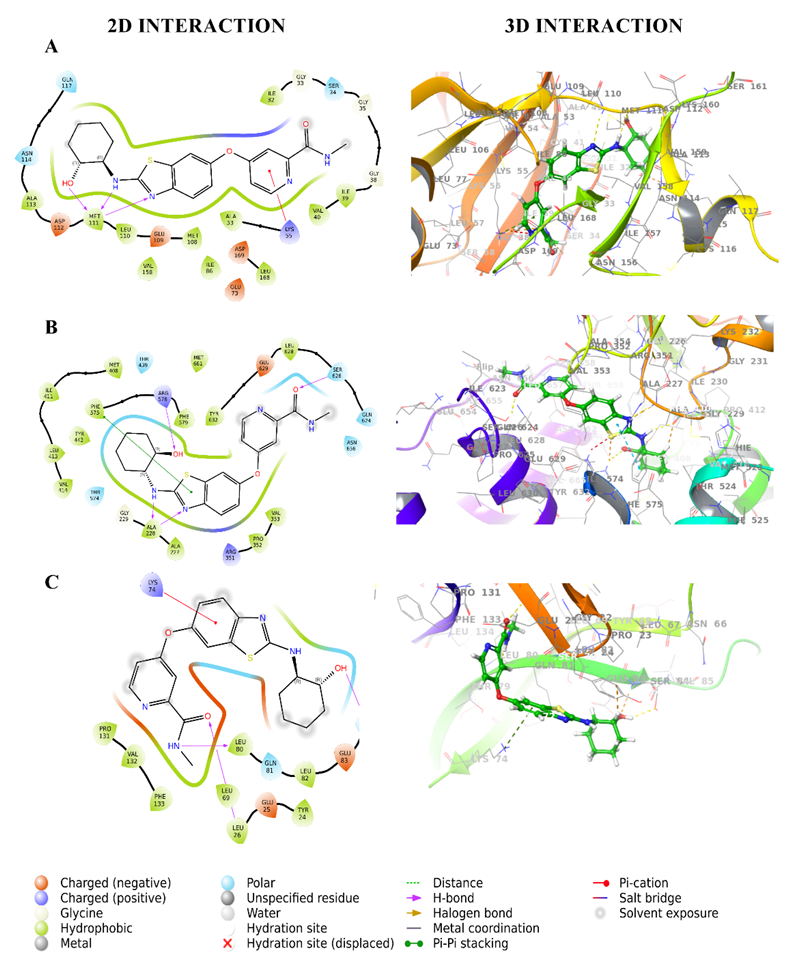

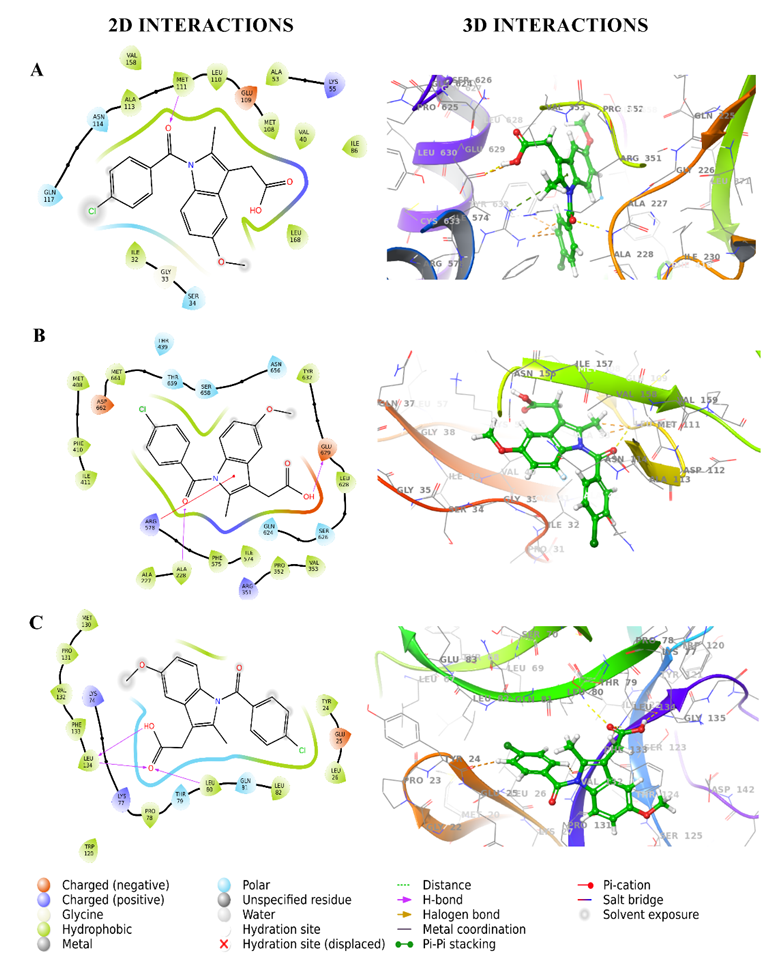

The docking investigation of CSF1R inhibitors with JNK (PDB ID: 3E7O) identified BLZ945 as the best-performing ligand, with a docking score of-11.107 kcal/mol significantly outperforming indomethacin (-8.189 kcal/mol). BLZ945 displayed strong hydrophobic contacts with Ala 113, Met 111, Leu 110, Val 158, Met 108, Ile 86, Leu 168, Ala 53, Val 40, Ile 39, and Ile 32 as well as polar interactions with Gln 117, Asn 114, and Ser 34. It also established hydrogen bonds with Met 111, demonstrating a consistent and advantageous binding profile. These findings are consistent with previous reports suggesting that hydrophobic and hydrogen bond interactions are critical for effective inhibition of JNK activity in neuroinflammation [4]. In contrast, indomethacin formed moderate hydrophobic contacts with Ala 113, Val 158, Met 111, Leu 110, Met 108, Ala 53, Val 40, Ile 86, Leu 168, Ile 32 and polar contacts with Met 111 but had a less favorable binding profile. This significant difference emphasizes BLZ945's greater and more consistent interaction with JNK, showing its ability to disrupt the neuroinflammatory pathways regulated by this protein. Chiauranib (-9.427 kcal/mol) exhibited substantial hydrophobic contacts with Ala 113, Met 111, Leu 110, Met 108, Ala 53, Leu 168, Val 158, Val 40, Ile 32 and polar interactions with Asn 114, Gln 117, Ser 34, Asn 156, Ser 155 including a hydrogen bond with Met 111 and Ser 155. Pexidartinib (-8.178 kcal/mol) and dovitinib (-8.444 kcal/mol) had comparable interaction patterns but somewhat lower binding affinities. ARRY382 (-7.882 kcal/mol) and indomethacin (-8.189 kcal/mol) showed moderate binding, but sorafenib (-6.619 kcal/mol) and DCC-3014 (-5.444 kcal/mol) had lesser interactions. Edicotinib, with a docking score of-4.653 kcal/mol, had the weakest binding strength. 2D and 3D interaction diagrams of BLZ945and reference drug indomethacin with 3E7O shown in fig. 1A and 2A give detailed information about hydrogen bonding, polar interactions, and hydrophobic interactions. The docking results are also consistent with other studies that have identified BLZ945 as a potent CSF1R inhibitor with therapeutic potential in neuroinflammatory diseases [15].

Table 6: Docking Interactions of CSF1R inhibitors with target proteins 3E7O, 7ALV and 5R8Q

| S. No. | Ligands | Protein ID | Hydrophic interaction | Polar interactions | Hydrogen bonding | Pi-Pi stacking |

| 1 | BLZ945 | 3E7O | Ala 113, Met 111, Leu 110, Val 158, Met 108, Ile 86, Leu 168, Ala 53, Val 40, Ile 39, Ile 32 | Gln 117, Asn 114, Ser 34 | Met 111 | |

| 7ALV | Met 408, Ile 411, Leu 413, Val 414, Phe 579, Phe 575, Tyr 443, Ala 228, Ala 227, Pro 352, Val 353, Leu 628, Tyr 632, Met 661 | Thr 439, Thr 524, Asn 656, Gln 624, Ser 626 | Arg 578, Ala 228, Ser 626 | Phe 575 | ||

| 5R8Q | Pro 131, Val 132, Phe 133, Leu 80, Leu 69, Leu 82, Leu 26, Tyr 24 | Gln 81, Ser 84 | Leu 80, Leu 69, Leu 26, Ser 84 | |||

| 2 | Pexidartinib | 3E7O | Ala 113, Met 111, Leu 110, VaL 158, Met 108, Ile 86, Leu 168, Ala 53, Val 40, Ala 42, Ile 32 | Gln 117, Asn 114, Ser 155 | Asn 114 | |

| 7ALV | Val 353, Pro 352, Ile 574, Phe 575, Met 661, Met 404, Phe 410, Ile 411, Leu 413, Val 414, Tyr 632, Ala 228, Ala 227, Tyr 443 | Thr 659, Thr 439, Thr 524, Ser 626, Gln 624 | Arg 578, Gln 624, | |||

| 5R8Q | Pro 131, Val 132, Phe 133, Leu 80, Leu 69, Leu 82, Leu 26, Tyr 24, Trp 120, Pro 78, Leu 134 | Gln 81, Thr79 | Leu 134, Leu 26 | |||

| 3 | Sorafenib | 3E7O | Ala 113, Met 111, Leu 110, Met 108, Ile 86, Ala 53, Leu 168, Val 40, Ile 39, Ala 36, Val 158, Ile 32 | Gln 117, Asn 114, Ser 34, Gln 37 | Met 111, Lys 55 | |

| 7ALV | Ala 228, Ala 227, Tyr 632, Leu 628, Ile 623, Leu 355, Val 353, Pro 352, Met 661, Met 408, Phe 410, Ile 411, Leu 413, VaL 414, Phe575, Tyr 443 | Ser 626, Gln 624, Ser 658, Thr659, Thr 439, Thr 524 | Arg 578 | |||

| 5R8Q | Pro 131, Phe 133, Leu 80, Leu 82, Leu 134, Tyr 24, Trp 120 | Thr 79, Gln 81, Ser 84 | Leu 82 | |||

| 4 | Dovitinib | 3E7O | Ala 113, Met 111, Leu 110, Val 158, Met 108, Ile 86, Ala 53, Leu 168, Ile 32, Val 40 | Gln 117, Asn 114 | Met 111 | |

| 7ALV | Met 408, Ile 411, Leu 413, Val 414, Tyr 443, Ala 228, Ala 227, Phe575, Pro 352, Val 353, Leu 628, Tyr 632, Met 661 | Thr 439, Thr 524, Asn656, Gln 624, Ser 626 | Ala 228, Ser 626 | |||

| 5R8Q | Pro 131, Val 132, Phe133, Leu 80, Leu 82, Tyr 24 | Thr 79, Gln 81, Ser 84 | Gln 81 | Tyr 24 | ||

| 5 | Chiauranib | 3E7O | Ala 113, Met 111, Leu 110, Met 108, Ala 53, Leu 168, Val 158, Val 40, Ile 32 | Asn 114, Gln 117, Ser 34, Asn 156, Ser 155 | Met 111, Ser 155 | |

| 7ALV | Val 353, Pro 352, Ala 227, Ala 228, Ile 417, Tyr 443, Val 414, Leu 413, Ile 411, Phe 410, Met 408, Tyr 632, Leu 628, Met 661, Ile 574, Phe 575 | Thr 524, Thr 439, Thr 659, Ser 658, Asn656, Gln 624, Ser 626 | Gln 624, Ser 626, Thr439 | |||

| 5R8Q | Pro 131, Val 132, Phe 133, Leu 80, Leu 82, Leu 69, Leu 26, Tyr 24 | Gln 81, Thr79 | Tyr 24, Leu 80, Lys 77 | |||

| 6 | Arry382 | 3E7O | Ala 113, Met 111, Leu 110, Val 158, Ile 86, Met 108, Leu 168, Ala 53, Ala 42, Val 40, Ile 32, Pro 31 | Gln 117, Asn 114, Ser 34, Gln 37 | Met 111 | |

| 7ALV | Met 661, Leu 628, Tyr 632, Met 408, Phe410, Ile 411, Leu 413, Val 414, Ile 417, Phe 579, Tyr 443, Phe575, Ile 574, Ala 228, Ala 227, Pro 352, Val 353, Leu 355 | Ser 658, Gln 624, Ser 626, Thr 439, Thr 524, Gln 225, Hie 177 | Ala 228 | Tyr 632 | ||

| 5R8Q | Pro 131, Phe 133, Leo 80, Met 130, Pro 23, Tyr 24 | Ser 125, Thr 79, Gln 81 | Lys 74, Leu 80 | |||

| 7 | DCC-3014 | 3E7O | Ala 113, Met 111, Leu 110, Met 108, Ile 86, Ala 53, Leu 168, Val 40, Ala 42, Ile 32, Val 158 | Asn 114, Gln 117, Ser 34, Asn 156, Ser 155 | Asn114, Met 111, Ser 155 | |

| 7ALV | Ile 623, Leu 628, Tyr 632, Met 408, Phe410, Ile 411, Tyr 443, Leu 413, Val 414, Phe 579, Ala 228, Ala 227, Phe 575, Ile 574, Met 661, Pro 352, Val 353 | Thr 439, Thr 524, Thr 659, Gln 624, Ser 626 | Ser 626 | |||

| 5R8Q | Trp 120, Pro 78, Leo 80, Leo 82, Val 132, Phe 133, Leu 134, Tyr 24 | Gln 81, Ser 84, Thr 79 | Lys 74, Leu 80, Leu 134 | Tyr 24 | ||

| 8 | Edicotinib | 3E7O | Ala 113, Met 111, Leu 110, Leu 168, Ala 53, Val 40, Ala 42, Ile 86, Val 158, Ile 32, | Gln 117, Asn 114, | Gln 117 | |

| 7ALV | Pro 352, Val 353, Leu 628, Tyr 632, Phe 575, Ile 574, Tyr 443, Val 414, Leu 413, Ile 411, Phe410, Met 408, Met 661, Ala 228, Ala 227 | Gln 624, Ser 626, Thr 439, Thr 524, Thr 659, Gln 225, Hie 177 | Arg 578 | |||

| 5R8Q | Pro 131, Val 132, Phe 133, Leu 80, Leu 82, Leu 26, Tyr 24, Pro 23 | Gln 81, Thr79 | Lys 74 | |||

| 9 | Indomethacin | 3E7O | Ala 113, Val 158, Met 111, Leu 110, Met 108, Ala 53, Val 40, Ile 86, Leu 168, Ile 32 | Gln 117, Asn 114, Ser 34 | Met 111 | |

| 7ALV | Val 353, Pro 352, Ile 574, Phe 575, Leu 628, Tyr 632, Met 408, Phe 410, Ile 411, Ala 227, Ala 228, Met 661, | Thr439, Ser 626, Gln 624, Asn 656, Ser 658, Thr 659 | Ala 228, Glu 629, | |||

| 5R8Q | Pro 131, Val 132, Phe133, Leu 134, Pro 78, Leu 80, Leu 82, Leu 26, Tyr 24, Trp 120, Met 130 | Gln 81 | Leu 26, Tyr 24 |

Binding with 7ALV

The docking analysis of CSF1R inhibitors with NLRP3 (PDB ID: 7ALV) identified BLZ945 as the best-performing molecule, with a docking score of-9.870 kcal/mol, compared to indomethacin’s score of-5.299 kcal/mol. BLZ945 has extensive hydrophobic interactions with residues including Met 408, Ile 411, Leu 413, Val 414, Phe 579, Phe 575, Tyr 443, Ala 228, Ala 227, Pro 352, Val 353, Leu 628, Tyr 632, and Met 661. It also generated polar contacts with Thr 439, Thr 524, Asn 656, Gln 624, and Ser 626, as well as hydrogen bonds with Arg 578, Ala 228, and Ser 626. Furthermore, BLZ945 had a pi-pi stacking interaction with Phe 575, indicating its high binding potential.

Pexidartinib, with a docking score of-6.517 kcal/mol, also showed considerable binding via hydrophobic interactions with important residues like Val 353, Pro 352, Ile 574, Phe 575, Met 661, Met 404, Phe 410, Ile 411, Leu 413, Val 414, Tyr 632, Ala 228, Ala 227, and Tyr 443. It demonstrated polar interactions with Thr 659, Thr 439, Thr 524, Ser 626, and Gln 624, as well as hydrogen bonds with Arg 578, and Gln 624, Chiauranib, with a score of-5.975 kcal/mol, showed hydrophobic contacts with comparable residues, polar interactions with Thr 524, Thr 439, Thr 659, Ser 658, Asn656, Gln 624, and Ser 626, and hydrogen bonds with Gln 624, Ser 626, and Thr 439.

Sorafenib (-5.464 kcal/mol) and dovitinib (-7.446 kcal/mol) exhibited weaker binding, with fewer hydrophobic contacts and less hydrogen bonding. The reference drug, indomethacin, exhibited consistent hydrophobic contacts with Val 353, Pro 352, Ile 574, Phe 575, Leu 628, Tyr 632, Met 408, Phe 410, Ile 411, Ala 227, Ala 228, Met 661, but was exceeded by BLZ945. Edicotinib (-0.046 kcal/mol) and DCC-3014 (-4.186 kcal/mol) exhibited much poorer binding due to insufficient polar and hydrophobic interactions. 2D and 3D interaction diagrams of BLZ945and reference drug indomethacin with 7ALV shown in fig. 1B and 2B give detailed information about hydrogen bonding, polar interactions, and hydrophobic interactions. Overall, BLZ945 emerged as the most promising NLRP3 inhibitor, with a superior interaction profile that highlights its potential as a therapeutic candidate for further investigation.

Binding with 5R8Q

The docking analysis of CSF1R inhibitors with IL-1β (PDB ID: 5R8Q) found that BLZ945 was the top-performing molecule, having the highest docking score of-4.872 kcal/mol compared to indomethacin’s score of-4.893 kcal/mol. BLZ945 had hydrophobic interactions with Pro 131, Val 132, Phe 133, Leu 80, Leu 69, Leu 82, Leu 26, and Tyr 24. It also generated polar contacts with Gln 81 and Ser 84, as well as hydrogen bonds with Leu 80, Leu 69, Leu 26, and Ser 84. Pexidartinib scored -6.167 kcal/mol and had similar hydrophobic interactions with Pro 131, Val 132, Phe 133, Leu 80, Leu 69, Leu 82, Leu 26, Tyr 24, and other residues such as Trp 120, Pro 78, and Leu 134. It also displayed polar interactions with Gln 81 and Thr 79, and hydrogen bonds with Leu 134 and Leu26.

Chiauranib, with a docking score of -4.881 kcal/mol, demonstrated comparable hydrophobic interactions and polar contacts, including Gln 81 and Thr 79, as well as hydrogen bonding to Tyr 24, Leu 80, and Lys 77. Sorafenib (-2.674 kcal/mol) and dovitinib (-2.742 kcal/mol) had weaker interactions, creating fewer hydrogen bonds. The reference drug indomethacin, with a score of -4.893 kcal/mol, exhibited hydrophobic interactions and polar contacts, but its binding strength was lower than BLZ945. The marginally lower score of indomethacin underscores its position as a weaker binder than BLZ945, especially for this target. Weak binding affinities were found for edicotinib (-2.619 kcal/mol) and DCC-3014 (-3.492 kcal/mol), which showed fewer meaningful interactions. 2D and 3D interaction diagrams of BLZ945and reference drug indomethacin with 7ALV shown in fig. 1B and 2B give detailed information about hydrogen bonding, polar interactions, and hydrophobic interactions. BLZ945 showed the highest binding affinity, indicating its promise as a treatment candidate for IL-1β, pending further validation studies.

Fig. 1: 2D and 3D interaction diagrams of BLZ945 with target proteins (A) Interaction with 3E7O, (B) Interaction with 7ALV, (C) Interaction with 5R8Q. The 3D diagrams depict the spatial fit of BLZ945 in the binding pockets, whereas the 2D diagrams show residue-level interactions.

Fig. 2: 2D and 3D interaction diagrams of Indomethacin with target proteins. (A) Interaction with 3E7O, (B) interaction with 7ALV, and (C) interaction with 5R8Q. The 3D diagrams show the spatial fit of Indomethacin in the binding pockets, whereas the 2D diagrams show residue-level interactions

The in silico investigation suggests that BLZ945 can modulate neuroinflammatory pathways by interacting with important targets such as JNK, NLRP3, and IL-1β. The molecular docking studies indicate that BLZ945 binds efficiently to JNK, an enzyme implicated in inflammation and cell death, potentially blocking its activation and lowering neuronal damage. Similarly, the inhibitor's interaction with NLRP3 supports a reduction in inflammasome activation, leading to lower IL-1β production, a critical mediator of neuroinflammation. The docking scores provide additional evidence for BLZ945's capacity to decrease these inflammatory pathways. However, while in silico docking shows these connections, computational predictions have limits since they do not fully describe how molecules behave in a biological system. Thus, scientific confirmation via cell-based and animal investigations is required to prove BLZ945's efficacy in regulating these pathways and demonstrating its therapeutic potential in neuroinflammatory diseases.

MM-GBSA

Indomethacin, as the reference drug, serves as a baseline for evaluating the binding effectiveness of different ligands. The binding energies for the three receptors vary from-37.64 kcal/mol (3E7O) to-53.84 kcal/mol (5R8Q), indicating a moderate interaction strength. While stable as a reference, several of the ligands in the study have higher binding affinities. ARRY382 and CHIAURANIB, for example, bind substantially better to 3E7O (-67.89 kcal/mol and-64.03 kcal/mol, respectively), indicating that they are stronger possibilities for further development.

These CSF1R inhibitors also surpass Indomethacin in terms of lipophilic and van der Waals contributions, which are critical for maintaining the ligand-receptor complex. Similarly, BLZ945 and SORAFENIB show greater binding to particular receptors such as 3E7O and 7ALV, demonstrating receptor-specific advantages over the reference drug. Indomethacin's lower binding energies compared to these ligands indicate that it is effective as a reference but less powerful. CSF1R inhibitors such as ARRY382, CHIAURANIB, and BLZ945 stand out as promising candidates with higher affinities and receptor selectivity, indicating significant promise for future therapeutic development. Table 7 shows the MM-GBSA data for CSF1R inhibitors with 3E7O, 7ALV, and 5R8Q, which support the ligands' binding strength, particularly BLZ945.

MD simulation

MD simulations were used to investigate the dynamic stability and conformational changes of docked complex structures containing the proteins 3E7O and 7ALV, as well as the ligands BLZ945 and the standard drug indomethacin. These simulations lasted 100 nanoseconds (ns) to provide a detailed dynamical picture of the ligand-protein interactions and conformational changes [33].

Table 7: MM-GBSA for CSF1R inhibitors with 3E7O, 7ALV and 5R8Q

| S. No. | Ligand ID | PDB ID | ΔG bind (kcal/mol)a | ΔG bind Coulombb | ΔG Bind Covalentc | ΔG Bind H bondd | ΔG Bind lipophilice | ΔG Bind van derf |

| 1 | BLZ945 | 3E7O | -53.58 | -24.47 | 11.78 | -2.11 | -19.61 | -51.40 |

| 7ALV | -47.51 | -26.96 | 6.51 | -2.11 | -18.98 | -39.18 | ||

| 5R8Q | -44.24 | -18.36 | 6.63 | -2.01 | -12.75 | -36.00 | ||

| 2 | PEXIDARTINIB | 3E7O | -52.55 | -7.07 | 4.85 | -0.57 | -21.24 | -44.00 |

| 7ALV | -47.19 | -14.80 | 2.10 | -2.33 | -17.55 | -43.99 | ||

| 5R8Q | -37.79 | -4.73 | 3.78 | -1.12 | -15.16 | -33.48 | ||

| 3 | SORAFENIB | 3E7O | -49.62 | -12.16 | 3.74 | -1.58 | -22.17 | -42.40 |

| 7ALV | -53.93 | -31.32 | 7.15 | -3.20 | -21.33 | -47.55 | ||

| 5R8Q | -40.95 | -6.94 | 5.60 | -1.01 | -17.65 | -41.88 | ||

| 4 | DOVITINIB | 3E7O | -44.31 | -10.17 | 2.05 | -1.01 | -8.73 | -42.29 |

| 7ALV | -47.52 | -34.88 | -0.15 | -1.57 | -11.56 | -37.95 | ||

| 5R8Q | -29.10 | -3.12 | 4.59 | -0.93 | -9.62 | -38.21 | ||

| 5 | CHIAURANIB | 3E7O | -64.03 | -19.36 | 7.54 | -1.80 | -25.05 | -53.76 |

| 7ALV | -53.53 | -24.69 | 5.46 | -1.52 | -26.14 | -47.94 | ||

| 5R8Q | -49.04 | -17.28 | 6.38 | -1.54 | -20.83 | -34.41 | ||

| 6 | ARRY382 | 3E7O | -67.89 | -7.03 | 5.81 | -0.88 | -24.16 | -67.47 |

| 7ALV | -56.29 | -7.83 | 5.98 | -1.03 | -27.83 | -64.33 | ||

| 5R8Q | -39.67 | -12.36 | 6.09 | -0.61 | -18.33 | -41.04 | ||

| 7 | DCC-3014 | 3E7O | -50.93 | -26.02 | 11.31 | -1.48 | -17.98 | -49.12 |

| 7ALV | -52.02 | -6.01 | 3.12 | -1.07 | -22.12 | -58.27 | ||

| 5R8Q | -37.29 | -8.81 | 5.82 | -1.82 | -12.27 | -35.37 | ||

| 8 | EDICOTINIB | 3E7O | -35.09 | -13.41 | 14.97 | -1.01 | -20.18 | -30.36 |

| 7ALV | -21.79 | -9.69 | 13.82 | -1.52 | -26.54 | -30.30 | ||

| 5R8Q | -30.80 | 4.19 | 2.99 | -0.00 | -16.98 | -37.46 | ||

| 9 | INDOMETHACIN | 3E7O | -37.64 | -9.74 | 7.11 | -0.51 | -18.27 | -33.94 |

| 7ALV | -47.91 | -20.72 | 1.51 | -1.78 | -16.14 | -37.82 | ||

| 5R8Q | -53.84 | -20.05 | 2.54 | -1.55 | -14.44 | -34.19 |

afree energy of binding, bcoulomb energy, ccovalent energy, dhydrogen bonding energy, ehydrophobic energy, fvan der Waals energy

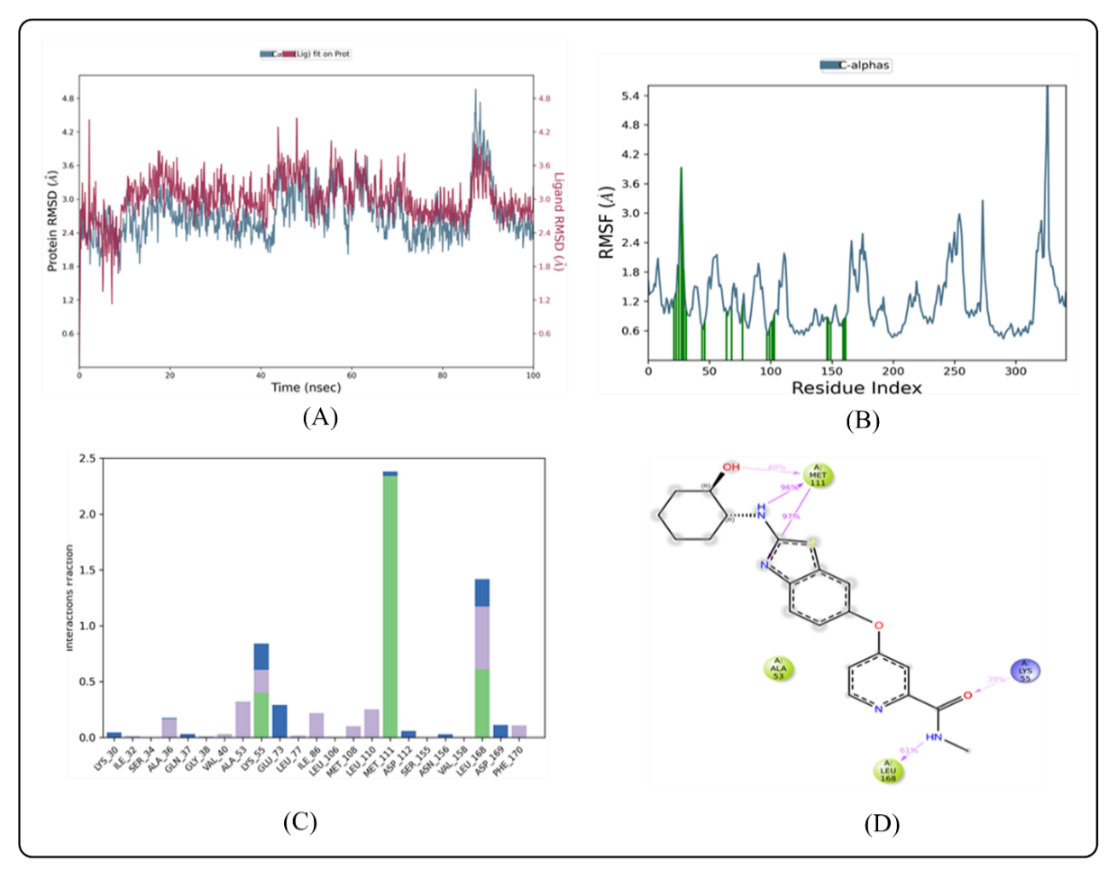

Analysis of 3E7O complex

RMSD analysis

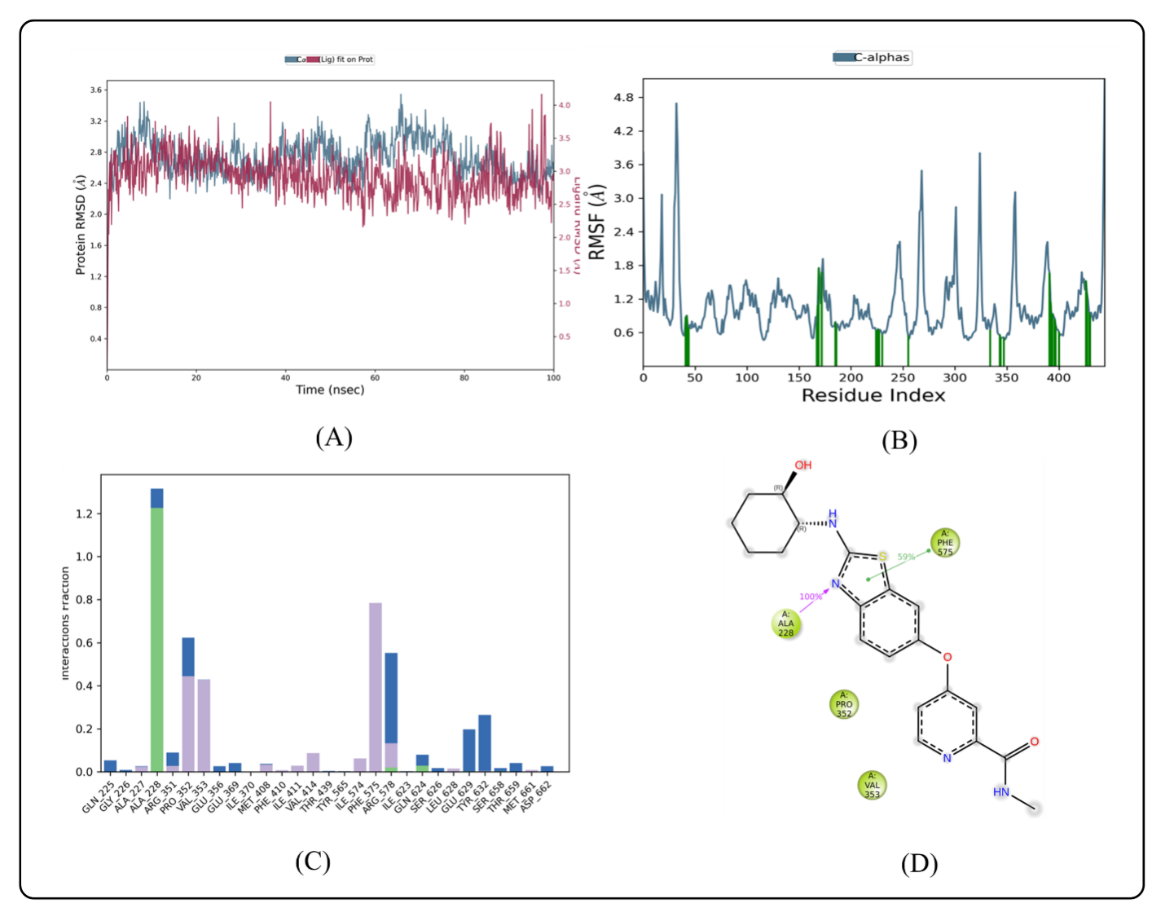

The calculated RMSD deviations for BLZ945 and indomethacin, based on their respective alpha carbon atoms, followed a pattern consistent with MD simulations. The BLZ945 complex has RMSD values ranging from 2.38 to 3.55 Å. After 50 ns, the simulations revealed that the ligand remained stable within the protein, with very slight fluctuation seen between 53 ns and 99.03 ns, as shown in fig. 3A. If the ligand's RMSD value is less than the protein's RMSD, it means that the ligand hasn't disseminated from its original binding site [41]. However, as fig. 3A illustrates the ligand was constant throughout the simulation, but the indomethacin-protein complex showed minor fluctuations during the first phase (0–12 ns).

The protein-ligand complexes' RMSD was more stable throughout the simulation, with minor fluctuations noted between 0 and 20 ns. The stability of the complex in a dynamic environment was demonstrated by the RMSD values of the protein's Cα atoms, which were obtained from the protein-ligand complex's simulated trajectory. According to prior studies, when the ligand’s RMSD value is lower than that of the protein's, it suggests that the ligand remains firmly docked to its original binding site [22]. The protein-ligand complex's equilibration was further substantiated by the slight changes in backbone RMSD. The backbone deviation was represented as the difference between the greatest and lowest RMSD values. In the dynamic simulation context, the protein-ligand complexes generally remained stable and consistent.

RMSF analysis

For the protein-ligand complex to remain stable throughout dynamic processes, individual amino acid residues are essential. The fluctuation of certain amino acids for the reference or native structure is measured by the RMSF parameter, which is generated from MD simulation trajectories. The protein complex's residual vibrations are revealed by the RMSF plot. As seen by the green vertical bar in the RMSF plot, the study showed very slight conformational changes in the amino acids within the 3E70 protein's binding cavity, especially those interacting with the lead compound. This shows that there were very minor variations in the active site and main chain residues, indicating that the lead compound binds well inside the target protein's binding pocket with minimal modification in conformation. Throughout the simulation, the RMSF of each amino acid residue was used to assess the protein system's flexibility. The N-terminal residues displayed greater changes in the RMSF plot (fig. 3B). Compound BLZ945 interacted with the amino acids of the protein throughout the simulation, and each of these interacting residues showed RMSF values between 0.81 Å and 1.34 Å. The amino acids in the protein also interacted with indomethacin; all interacting residues had RMSF values ranging from 1.34 Å to 1.74 Å (fig. 4B).

Protein-ligand contact analysis

The protein-ligand interactions involving amino acid residues that stabilize the complex with BLZ945 are depicted in (fig. 3C). The residues Ile 32, Ser 34, Ala 36, Val 40, Ala 53, Lys 55, Ile 86, Leu 106, Met 108, Leu 110, Leu 168, and Phe 170 are responsible for the hydrophobic interactions with BLZ945. The stability of the protein-ligand complex is largely dependent on these interactions. Additionally, water bridges with BLZ945, which are essential for mediating protein-ligand interactions and maintaining the complex, were formed by residues Lys 30, Gln 37, Lys 55, Glu 73, Asp 112, Asn 156, Leu 168, and Asp 169. Additionally, residues Lys 55, Met 111, and Leu 168 established hydrogen bonds with BLZ945. Ile 32, Val 40, Ala 53, Ile 86, Met 108, Leu 110, Val 158, and Leu 168 were the residues that contributed to hydrophobic interactions for the indomethacin-protein complex. These residues also helped to keep the complex stable. The protein-ligand complex was further stabilized by the participation of residues Ile 32, Ser 34, Gly 35, Glu 73, Leu 168, and Asp 169 in the formation of water bridges. Furthermore, as seen in fig. 4C, Lys 55, Glu 109, Met 111, Leu 168, and Asp 169 participated in the formation of hydrogen bonds with indomethacin. Based on ligand-mediated two-dimensional interactions seen in fig. 3D, the protein-ligand contact analysis revealed that Met 111 and Leu 168 formed substantial hydrophobic bonds with BLZ945, which accounted for 40–97% of the simulation time. Through positively charged connections, Lys 55 also had a role in 39% of the encounters. Similarly, Met 111 and Leu 168 formed hydrophobic bonds with indomethacin for 85% and 36% of the simulation duration, respectively, according to the contact analysis for the indomethacin-protein complex, which is displayed in fig. 4D.

Fig. 3: MD simulation of ligand BLZ945 in complex with enzyme 3E7O (A) Protein-ligand RMSD (B) Protein RMSF (C) Protein-ligand contacts (D) Ligand-protein contacts

Fig. 2: MD simulation of ligand indomethacin in complex with enzyme 3E7O (A) Protein-ligand RMSD (B) Protein RMSF (C) Protein-ligand contacts (D) Ligand-protein contacts

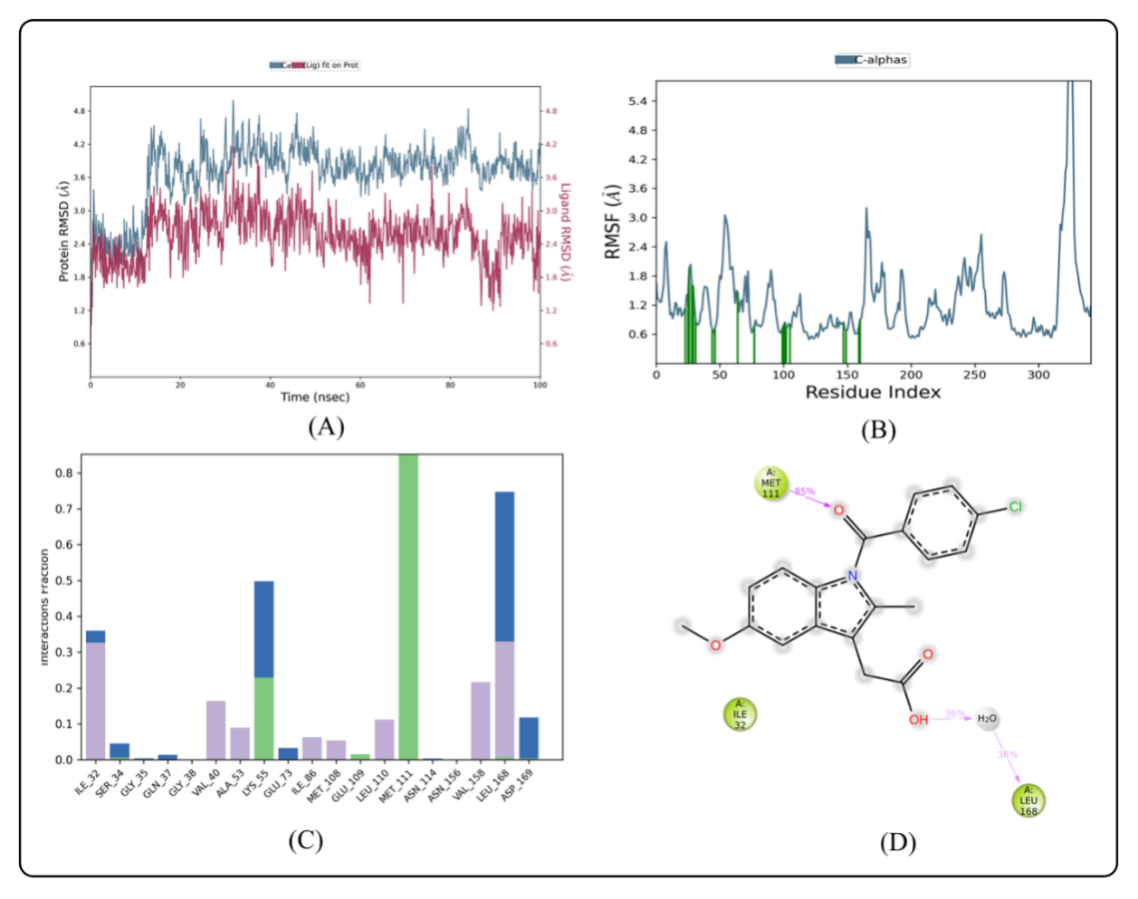

Analysis of 7ALV complex

RMSD analysis

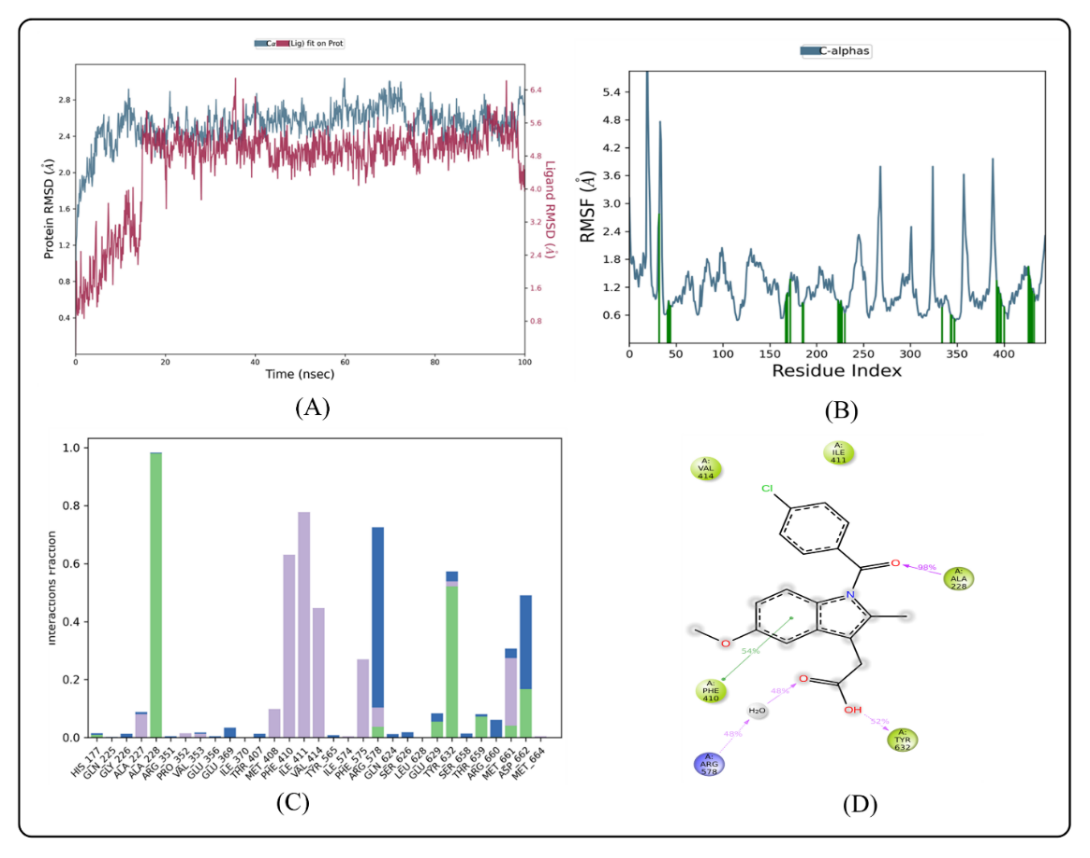

Based on their individual alpha carbon atoms, the computed RMSD deviations for indomethacin and BLZ945 showed an overall pattern that was in line with MD simulations. If the ligand's RMSD value is less than the protein's RMSD, it means that the ligand hasn't disseminated from its original binding site [41]. RMSD readings for the BLZ945 complex fluctuated slightly between 10 and 28 ns, with values ranging from 0 to 100 ns. As seen in fig. 5A, the simulation then revealed that the ligand remained stable inside the protein until 35 ns, with very slight variations happening between 85 and 90 ns. The indomethacin-protein complex, on the other hand, showed a steady pattern with minor fluctuations at the beginning of the simulation and at about 26 ns. As observed in fig. 6A, the ligand was steady after these points until the simulation's end. Throughout the simulation, the protein-ligand complexes' RMSD was more stable, with only slight fluctuations seen between 0 and 20 ns. The stability of the complex in a dynamic environment was demonstrated by the RMSD values of the protein's Cα atoms, which were obtained from the simulated trajectory. According to prior studies, when the ligand’s RMSD value is lower than that of the protein's, it suggests that the ligand remains firmly docked to its original binding site [22]. Protein Cα atoms with higher RMSD values show structural unfolding, whereas those with lower values show compactness. The protein-ligand complex's equilibration was further evidenced by the slight changes in backbone RMSD. The degree of backbone deviation was shown by the difference between the greatest and lowest RMSD values. In the dynamic simulation context, the ligand-protein complexes generally showed consistency and stability.

RMSF analysis

The stability of dynamic processes is largely dependent on the individual amino acid residues in the protein-ligand complex. The fluctuation of certain amino acids for the reference or native structure is measured by the RMSF parameter, which is generated from MD simulation trajectories. The protein complex's residual vibrations are revealed by the RMSF plot. As observed by the green vertical bar in the RMSF plot, the study showed very slight conformational changes in the amino acids within the 7ALV protein's binding cavity, especially those interacting with the lead compound. The fact that the main chain and active site residues only slightly fluctuated suggests that the lead compound binds strongly to the target protein's binding pocket with minor conformational changes. Throughout the simulation, the RMSF of each amino acid residue was used to assess the protein system's flexibility. The N-terminal residues displayed greater fluctuations in the RMSF plot (fig. 5B). The compound BLZ945 interacted with the protein's amino acids during the simulation, and all of the interacting residues showed RMSF values between 0.64 and 1.23 Å. On the other hand, as seen in fig. 6B, the interacting residues for the indomethacin-protein complex showed RMSF values ranging from 1.31 to 2.90 Å.

Protein-ligand contact analysis

The protein-ligand interactions that stabilize the BLZ945-protein complex are shown in (fig. 5C). The amino acid residues Ala 227, Arg 351, Val 353, Met 408, Phe 410, Ile 411, Val 414, Ile 574, Phe 575, Arg 578, Leu 628, and Met are responsible for the hydrophobic interactions with BLZ945. The stability of the protein-ligand complex is largely dependent on these interactions. The complex was further stabilized by the formation of water bridges with BLZ945 by residues Gln 225, Gly 226, Arg 351, Pro 352, Glu 369, Arg 578, Gln 624, Glu 629, Tyr 632, Ser 658, Thr 659, Met 661, and Asp 662. The ligand and residues Ala 227, Arg 578, Gln 624, and Ser 658 were shown to form hydrogen bonds. The stability of the indomethacin-protein complex was greatly enhanced by the hydrophobic interactions involving residues Gly 226, Pro 352, Val 353, Met 408, Phe 410, Ile 411, Val 414, Ile 574, Arg 578, Met 661, and Met 664. In order to further stabilize the complex, residues Gly 227, Pro 352, Met 408, Phe 410, Ile 411, Val 414, Ile 574, Phe 575, Arg 578, and Met 661 formed water bridges with indomethacin. Fig. 6C illustrates the formation of hydrogen bonds with residues His 177, Ala 227, Phe 575, Glu 629, Tyr 632, Thr 659, Met 661, and Asp 662. Based on ligand-mediated two-dimensional interactions, ligand-protein contact analysis (fig. 5D) showed that Ala 228 formed a strong hydrophobic binding with BLZ945, which lasted the whole simulation period. Furthermore, Phe 575 contributed 59% of the simulation time by exhibiting pi-pi stacking interactions with BLZ945. Val 414, Ile 411, Ala 228, and Tyr 632 produced large hydrophobic connections for the indomethacin complex, according to contact analysis (fig. 6D), which accounted for 98% and 52% of the simulation time, respectively. Pi-pi stacking interactions were seen in Phe 410, whereas 48% of the interactions were attributed to a positive charge in Arg 578.

Fig. 5: MD simulation of ligand BLZ945 in complex with enzyme 7ALV (A) Protein-ligand RMSD (B) Protein RMSF (C) Protein-ligand contacts (D) Ligand-protein contacts

Fig. 6: MD simulation of ligand indomethacin in complex with enzyme 7ALV (A) Protein-ligand RMSD (B) Protein RMSF (C) Protein-Ligand Contacts (D) Ligand-protein contacts

CONCLUSION

The study shows that CSF1R inhibitors, specifically BLZ945, have substantial interactions with neuroinflammation proteins like JNK, NLRP3, and IL-1β. These inhibitors exhibit physicochemical properties, oral bioavailability, and the ability to traverse the BBB, making them promising candidates for therapeutic intervention in neuroinflammatory diseases. Despite certain compounds having moderate to high toxicity concerns, BLZ945 stands out due to its greater binding affinities and positive drug-like properties, implying that it could be a useful therapy choice for neuroinflammation-related disorders. MD simulations indicated that BLZ945 is stable and strongly bound in complexes with 3E7O and 7ALV proteins. BLZ945 demonstrated more consistent binding, with lower RMSF values and greater interaction percentages, indicating to be a therapeutic option. However, these conclusions are based on computational data and must be supported by experimental trials. While the in silico results imply BLZ945 has intriguing therapeutic potential, further experimental work is needed to demonstrate its effectiveness and safety in biological systems. This step is required to proceed with BLZ945 as a potential therapy for neuroinflammation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors are thankful to the authorities of NGSM Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Nitte (Deemed to be University), Mangalore, India for providing all the necessary facilities.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr. Ronald Fernandes contributed to the conception and design of the study, provided insights into the research direction, and supervised the manuscript review. Ms. Deepthi K was involved in the conceptualization of the work, helping design the experiments and contributing to the manuscript review and preparation. Ms. Veena V Tom played a key role in the study design, particularly with experimental approaches, and participated in the critical revision of the manuscript. Dr. Yogish Somayaji contributed to the conceptualization and design of the research and also participated in the final review and approval of the manuscript. Ms. Athira Sasidharan performed the experimental work, interpretation of data, and drafting of the manuscript. Dr. Sheshagiri Dixit and Ms. Deepshikha Singh contributed to the MD simulations, analyzed the results, and provided a detailed interpretation of the computational findings. The final draft was reviewed and approved by all authors before submission for publication.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Kwon HS, Koh SH. Neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative disorders: the roles of microglia and astrocytes. Transl Neurodegener. 2020 Nov 26;9(1):42. doi: 10.1186/s40035-020-00221-2, PMID 33239064.

Adamu A, LI S, Gao F, Xue G. The role of neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative diseases: current understanding and future therapeutic targets. Front Aging Neurosci. 2024 Apr 12;16:1347987. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2024.1347987, PMID 38681666.

Paik S, Kim JK, Silwal P, Sasakawa C, JO EK. An update on the regulatory mechanisms of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Cell Mol Immunol. 2021 May;18(5):1141-60. doi: 10.1038/s41423-021-00670-3, PMID 33850310.

Benakis C, Vaslin A, Pasquali C, Hirt L. Neuroprotection by inhibiting the c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathway after cerebral ischemia occurs independently of interleukin-6 and keratinocyte derived chemokine (KC/CXCL1) secretion. J Neuroinflammation. 2012 Dec;9:76. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-76, PMID 22533966.

Hewett SJ, Jackman NA, Claycomb RJ. Interleukin-1β in central nervous system injury and repair. Eur J Neurodegener Dis. 2012 Aug;1(2):195-211. PMID 26082912.

Mehan S, Meena H, Sharma D, Sankhla R. JNK: a stress-activated protein kinase therapeutic strategies and involvement in alzheimers and various neurodegenerative abnormalities. J Mol Neurosci. 2011 Mar;43(3):376-90. doi: 10.1007/s12031-010-9454-6, PMID 20878262.

Holbrook JA, Jarosz Griffiths HH, Caseley E, Lara Reyna S, Poulter JA, Williams Gray CH. Neurodegenerative disease and the NLRP3 inflammasome. Front Pharmacol. 2021 Mar 10;12:643254. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.643254, PMID 33776778.

Musi CA, Agro G, Santarella F, Iervasi E, Borsello T. JNK3 as therapeutic target and biomarker in neurodegenerative and neurodevelopmental brain diseases. Cells. 2020 Sep 28;9(10):2190. doi: 10.3390/cells9102190, PMID 32998477.

Yan H, HE L, LV D, Yang J, Yuan Z. The role of the dysregulated JNK signaling pathway in the pathogenesis of human diseases and its potential therapeutic strategies: a comprehensive review. Biomolecules. 2024 Feb 19;14(2):243. doi: 10.3390/biom14020243, PMID 38397480.

Anfinogenova ND, Quinn MT, Schepetkin IA, Atochin DN. Alarmins and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling in neuroinflammation. Cells. 2020 Oct 24;9(11):2350. doi: 10.3390/cells9112350, PMID 33114371.

MA Q, Lim CS. Molecular activation of NLRP3 inflammasome by particles and crystals: a continuing challenge of immunology and toxicology. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2024 Jan 23;64(1):417-33. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-031023-125300, PMID 37708431.

Erdag E, Kucuk M, Aksoy U, Abacioglu N, Ozer A. Docking study of ligands targeting NLRP3 inflammatory pathway for endodontic diseases. Chem Methodol. 2023;7(3):200-10. doi: 10.22034/CHEMM.2022.367137.1623.

Chandana L, Bhikshapathi DV. Ethnopharmacological investigation of pleurotus ostreatus for anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory activity in experimental animals. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2024;17(4):37-41. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2024.v17i4.49533.

Jadhav SP. MicroRNAs in microglia: deciphering their role in neurodegenerative diseases. Front Cell Neurosci. 2024 May 15;18:1391537. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2024.1391537, PMID 38812793.

Xiang C, LI H, Tang W. Targeting CSF-1R represents an effective strategy in modulating inflammatory diseases. Pharmacol Res. 2023 Jan 1;187:106566. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2022.106566, PMID 36423789.

Wang W, LI Y, MA F, Sheng X, Chen K, Zhuo R. Microglial repopulation reverses cognitive and synaptic deficits in an alzheimers disease model by restoring BDNF signaling. Brain Behav Immun. 2023 Oct 1;113:275-88. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2023.07.011, PMID 37482204.

Barca C, Foray C, Hermann S, Herrlinger U, Remory I, Laoui D. The colony-stimulating factor-1 receptor (CSF-1R)-mediated regulation of microglia/macrophages as a target for neurological disorders (glioma stroke). Front Immunol. 2021 Dec 7;12:787307. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.787307, PMID 34950148.

Han J, Chitu V, Stanley ER, Wszolek ZK, Karrenbauer VD, Harris RA. Inhibition of colony stimulating factor-1 receptor (CSF-1R) as a potential therapeutic strategy for neurodegenerative diseases: opportunities and challenges. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2022 Apr;79(4):219. doi: 10.1007/s00018-022-04225-1, PMID 35366105.

HU B, Duan S, Wang Z, LI X, Zhou Y, Zhang X. Insights into the role of CSF1R in the central nervous system and neurological disorders. Front Aging Neurosci. 2021 Nov 15;13:789834. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2021.789834, PMID 34867307.

Guenoun D, Blaise N, Sellam A, Roupret Serzec J, Jacquens A, Steenwinckel JV. Microglial depletion a new tool in neuroinflammatory disorders: comparison of pharmacological inhibitors of the CSF‐1R. Glia. 2025 Apr;7(34):686-700. doi: 10.1002/glia.24664, PMID 39719687.

Azhar Z, Grose RP, Raza A, Raza Z. In silico targeting of colony-stimulating factor-1 receptor: delineating immunotherapy in cancer. Explor Target Antitumor Ther. 2023;4(4):727-42. doi: 10.37349/etat.2023.00164, PMID 37711590.

KD, Katagi MS, Fernandes J, Dixit S, Singh D. Novel hybrids of quinoline linked pyrimidine derivatives as cyclooxygenase inhibitors: molecular docking admet study and md simulation. Int J App Pharm. 2024 Nov 7:16(6):147-57. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2024v16i6.52023.

James JP, Ail PD, Crasta L, Kamath RS, Shura MH, Sindhu TJ. In silico ADMET and molecular interaction profiles of phytochemicals from medicinal plants in Dakshina Kannada. J Health Allied Sci NU. 2024 Apr;14(2):190-201. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-1770057.

Ntie Kang F, Lifongo LL, Mbah JA, Owono Owono LC, Megnassan E, Mbaze LM. In silico drug metabolism and pharmacokinetic profiles of natural products from medicinal plants in the Congo basin. In Silico Pharmacol. 2013 Dec;1:12. doi: 10.1186/2193-9616-1-12, PMID 25505657.

Arman M, Alam S, Maruf RA, Shams Z, Islam MN. Molecular modeling of some commercially available antiviral drugs and their derivatives against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Narra J. 2024 Apr;4(1):e319. doi: 10.52225/narra.v4i1.319, PMID 38798846.

Adnyaswari DA, Indrayani AW, Artini IG. In silico toxicity and pharmaceutical properties to get candidates for antitumor drug. J Pharm Res Int. 2024 Feb 23;36(2):1. doi: 10.9734/JPRI/2024/v36i27497.

Madriwala B, Jays J, Sai GC. Molecular docking and computational pharmacokinetic study of some novel coumarin benzothiazole schiff’s base for antimicrobial activity. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2022 Aug 1:14(8):16-21. doi: 10.22159/ijpps.2022v14i8.45046.

Husain A, Ahmad A, Khan SA, Asif M, Bhutani R, Al Abbasi FA. Synthesis molecular properties toxicity and biological evaluation of some new substituted imidazolidine derivatives in search of potent anti-inflammatory agents. Saudi Pharm J. 2016 Jan 1;24(1):104-14. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2015.02.008, PMID 26903774.

Mahalekshmi V, Balakrishnan N, TV, AK, VP. In silico molecular screening and docking approaches on antineoplastic agent irinotecan towards the marker proteins of colon cancer. Int J App Pharm. 2023;15(5):84-92. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2023v15i5.48523.

Elmi A, Sayem SA, Ahmed M, Abdoul Latif F. Natural compounds from djiboutian medicinal plants as inhibitors of COVID-19 by in silico investigations. Int J Curr Pharm Sci. 2020 Jul 15;12(4):52-7. doi: 10.22159/ijcpr.2020v12i4.39051.

Jays J, Saravanan J. A molecular modelling approach for structure-based virtual screening and identification of novel isoxazoles as potential antimicrobial agents against S. aureus. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2024 Apr 1;16(4):36-41. doi: 10.22159/ijpps.2024v16i4.49731.

Chand J, Kandy AT, Prasad K, Mathew J, Sherin F, Subramanian G. In silico preparation and in vitro studies of benzylidene based hydroxy benzyl urea derivatives as free radical scavengers in parkinsons disease. Int J App Pharm. 2024 May 7;16(3):217-24. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2024v16i3.50628.

Baqi MA, Jayanthi K, R. Identification of benzylidene amino phenol inhibitors targeting thymidylate kinase for colon cancer treatment through in silico studies. Int J App Pharm. 2024 Jul 7;16(4):92-9. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2024v16i4.50874.

S JP, Sharmila P, Sangeetha K, Ponmurugan P. Phytochemical characterization in vitro and in silico studies on therapeutic potential of edible and wild mushrooms. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2025 Jan 7;18(1):68-80. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2025v18i1.53352.

Raymer B, Bhattacharya SK. Lead like drugs: a perspective. J Med Chem. 2018 Jul 27;61(23):10375-84. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00407, PMID 30052440.

Shahbazi S, Kaur J, Singh S, Achary KG, Wani S, Jema S. Impact of novel N-aryl piperamide NO donors on NF-κB translocation in neuroinflammation: rational drug designing synthesis and biological evaluation. Innate Immun. 2018 Jan;24(1):24-39. doi: 10.1177/1753425917740727, PMID 29145791.

Cardoza S, Singh A, Sur S, Singh M, Dubey KD, Samanta SK. Computational investigation of novel synthetic analogs of C-1’ β substituted remdesivir against RNA-dependent RNA-polymerase of SARS-CoV-2. Heliyon. 2024 Sep 15;10(17):e36786. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e36786, PMID 39286185.

Pires DE, Blundell TL, Ascher DB. PKCSM: Predicting small molecule pharmacokinetic and toxicity properties using graph-based signatures. J Med Chem. 2015;58(9):4066-72. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00104, PMID 25860834.

Vijay U, Gupta S, Mathur P, Suravajhala P, Bhatnagar P. Microbial mutagenicity assay: Ames test. Bio Protoc. 2018 Mar 20;8(6):e2763. doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.2763, PMID 34179285.

Sabarees G, Velmurugan V, Solomon VR. Discovery of new naphthyridine hybrids against enoyl-ACP reductase (inhA) protein target of mycobacterium tuberculosis: molecular docking molecular dynamics simulations studies. Chem Phys Impact. 2023 Dec 1;7:100399. doi: 10.1016/j.chphi.2023.100399.

WU N, Zhang R, Peng X, Fang L, Chen K, Jestila JS. Elucidation of protein-ligand interactions by multiple trajectory analysis methods. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2024;26(8):6903-15. doi: 10.1039/d3cp03492e, PMID 38334015.