Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 5, 2025, 21-29Review Article

THERAPEUTIC POTENTIAL AND APPLICATIONS OF BIOGLASS: A REVIEW

VADNALA SRAVANI*1, M. VIDYAVATHI2

1Malla Reddy Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Malla Reddy Viswavidyapeeth, Hyderabad, Telangana, 500100, India. 2Institute of Pharmaceutical Technology, Sri Padmavati Mahila Visvavidyalayam, Tirupati, (A.P.).

*Corresponding author: Vadnala Sravani; *Email: sravanithula@gmail.com

Received: 17 Dec 2024, Revised and Accepted: 05 Jul 2025

ABSTRACT

Bioglass has emerged as a revolutionary biomaterial because of its bioactivity, biocompatibility, and capacity to form a bond with both hard and soft tissues. Originally, Dr. Larry Hench in the late 1960s developed. Bioglass, which has proven especially effective in bone regeneration, dental restoration, and wound healing, positioning it as a versatile material for various medical applications. Unlike traditional bioinert materials, bioglass fosters a beneficial biological response when in contact with physiological environments, forming a hydroxyl carbonate apatite [HCA] layer on its surface that mimics natural bone mineral. This bioactivity, combined with its customizable composition, has enabled the development of various bioglass types tailored for specific applications. In this review, fundamental properties that contribute to bioglass effectiveness and primary healthcare applications of bioglass, focusing on its role in bone grafts, dental fillers, and coatings for implants discussed. Furthermore, this review explore its promising applications in wound healing, where bioglass dressings offer accelerated tissue repair and reduced infection risks. The main objective of this review is to provide a thorough insight into bioglass, with a focus on its present-day uses in the medical field.

Keywords: Bioglass, Wound healing, Bone repair, Biomaterials, Tissue engineering, Hydroxycarbonate apatite

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i5.53435 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Biomaterials, whether natural or synthetic, plays a pivotal role in regenerative medicine, dentistry, infection treatment, and they serves to replace damaged tissues [due to trauma or burns] or redeem biological functions [1-4]. An ideal biomaterial for clinical applications must be readily available, cost-effective, non-toxic, and inert to prevent adverse body reactions or infections. Additionally, it should be easy to shape, not require prolonged surgical time, and not interfere with medical imaging procedures.

In medical field, bioactive glasses stand out as a distinctive group of oxide-based biocompatible ceramics. These materials possess the ability to form bonds with both hard and soft tissues and simultaneously promoting tissue growth while gradually dissolving. This characteristic makes bioactive glasses particularly appealing for use in healthcare and regenerative medicine [5-7]. Dr. Larry Hench developed the groundbreaking 45S5 Bioglass in the late 1960s [8]. This innovative bioactive glass have been utilized in clinical procedures for orthopedic and dental purposes since the mid-1980s [9, 10]. The 45S5 formulation, which consists of silica [SiO₂], sodium oxide [Na₂O], calcium oxide [CaO], and phosphorus pentoxide [P₂O₅], has become the basis for most bioactive glasses. These glasses maintain their bioactive properties when their SiO₂ content is below 55%.

The chemical composition of bioactive glasses significantly influence their ability to induce bone formation, exhibit antibacterial effects, undergo degradation, and facilitate soft tissue repair and healing of the wound. Adjustments to the proportions of the primary components allow for tailored applications that meet various clinical needs [11-15]. Production methods like melt-derived processes enable the creation of components of various shapes and sizes, such as prosthetic middle ear ossicles or fibers [16, 17]. Additionally, these glasses produced through melting can transformed into powder form to create porous three-dimensional scaffolds, which serve as frameworks for tissue development [18].

The bioactivity of bioglass stands out as one of its most remarkable properties. When exposed to physiological fluids, bioglass undergoes surface reactions that results in the formation of a HCA layer, resembles the mineral composition of natural bone [19]. This HCA layer enables bioglass to connect with bone tissue and encourages osteogenesis, establishing it as important material for bone transplantation and orthopedic implants [20]. Beyond bone repair, bioglass has demonstrated potential in wound healing, soft tissue regeneration, and delivery of the drug due to its biocompatibility and customizable degradation rates, allowing for controlled release of therapeutic agents [21]. Recent advancements in bioglass technology have expanded its application scope to include antibacterial coatings, which are essential for preventing infections in medical devices [22]. Composite materials, combining bioglass with polymers or metals, further enhance its versatility and mechanical stability, making bioglass a crucial component in the next generation of medical materials [23].

Despite the extensive research on the properties and applications of bioglass, its comprehensive role in clinical areas, including bone repair, dental restoration, wound healing, and drug delivery, is still lacking. Current literature often focuses on individual applications or specific compositions, leaving a fragmented understanding of the broader potential of bioglass in modern healthcare. This review seeks to address these gaps by providing a holistic examination of bioglass materials, emphasizing their unique properties, clinical versatility, and transformative impact across multiple fields of medicine and regenerative therapy. The aim of this review is to provide a comprehensive overview of unique properties of bioglass and highlighting its crucial roles in bone repair, dental restoration, wound healing. This review written by searching the keywords bioglass, properties, dental applications 45S5 glass, boran and phosphate glasses, clinical studies for last 10 y from databases like PubMed and Science Direct, Google Scholar.

Types of glasses

Bioactive glasses classified into three primary types based on their network-forming oxides and chemical composition. They are silicate glasses, borate glasses, and phosphate glasses [24].

Silicate glasses

Silicate glasses are built from "SiO₄ tetrahedra," where each silicon atom surrounded by four oxygen atoms. These tetrahedra link together through shared oxygen atoms, forming the structural backbone of silicate-based materials [25]. However, the addition of elements like calcium (Ca²⁺), sodium (Na⁺), or magnesium (Mg²⁺) known as network modifiers, disrupts these connections, creating a more reactive and bioactive structure [26].

Bioglass 45S5 known for its high bioactivity and strong bonding capabilities with bone. Its silica content gives it a suitable balance of bioactivity and degradability, while the calcium and phosphate content promote bone regeneration and bonding. During the degradation process of bio glass, it releases essential ionic components that interact with surrounding environmental ions to form a carbonated hydroxyapatite layer. This HCA coating subsequently establishes robust connections with neighboring bone tissue, promoting and accelerating its growth. Additionally, numerous in vitro and in vivo experiments conducted on 45S5 Bio glass have shown its capability for creating scaffolds in the field of tissue engineering. In tissue engineering, these structures serve as crucial elements, designed to produce biological replacements for restoring or substituting damaged tissues resulting from age-related deterioration or medical conditions. These three-dimensional structures contain pores ranging from 100 µm to 300 µm in size. These pores promote the production of vascular endothelial growth factor, facilitate cell penetration, and promote vascularization [27].

Borate glasses

In borate glasses, boron trioxide [B2O3] is essential component for network formation [28]. Borate-based glasses like 13-93B3 are created by substituting SiO2 in silicate glass with B2O3 and incorporating network modifiers such as K2O and MgO. Unlike silicate-based 45S5, these glasses degrade more quickly and show bioactivity. Nevertheless, a potential drawback of borate bioactive glasses is the possible toxic effects resulting from the substantial release of borate ions in a "static" in vitro environment. The challenges associated with this issue have reduced in "dynamic" culture conditions and in vivo contexts [29, 30].

Recent years have seen a surge of interest in borate glasses, driven by encouraging results from pre-clinical and in vivo investigations into their efficacy for treating long-lasting wounds [including diabetic ulcers] in comparison to established treatment methods [31, 32]. Boron offers several advantages, including its ability to enhance vascularization, support angiogenesis, and boost RNA production in fibroblasts [33]. The U. S. Food and Drug Administration granted approval for 13-93B3 in wound healing applications in 2016 [34]. Additionally, this glass variety utilized in scientific studies to develop frameworks for tissue engineering purposes. Additionally, in vivo studies suggest borate-based bioactive glasses are promising for antibiotic delivery, although more research needed due to limited clinical data [35].

Phosphate glasses

In phosphate glasses, phosphorus pentoxide [P₂O₅] is the primary network-forming component. The core structural unit is an orthophosphate tetrahedron [PO4-], comprising a phosphorus atom at the center encircled by four oxygen atoms [36]. The orthophosphate tetrahedron can only connect to three additional phosphate tetrahedra because one oxygen atom forms a double bond with phosphorus [37].

Phosphate glasses, which consist of P₂O₅ as the primary network component and CaO and Na2O as network modifiers [e. g., P50C35N15] have chemical compositions similar to those of bone minerals [38]. By altering their compositions, the rate at which phosphate glasses break down or dissolve can be controlled. Compared to silica-based bioglasses, phosphate-based glasses are more degradable and resorbable, making them suitable for applications requiring faster degradation. They are frequently used in soft tissue applications, drug delivery systems, and wound care, where gradual degradation and ion release support healing and therapeutic effects [39]. Table 1 shows specific compositions for different types of bioactive glass.

Table 1: Specific chemical compositions for different bioactive glasses

| Component | 45S5 [wt%] | 58S [wt%] | 13-93B3 [wt%] | P50C35N15 [wt%] | S53P4 [wt%] | 70S30C [wt%] | 13-93 [wt%] |

| SiO2 | 45 | 58.2 | - | - | 53 | 71.4 | 53 |

| P2O5 | 6 | 9.2 | 4 | 71 | 4 | - | 4 |

| B2O3 | - | - | 53 | - | - | - | - |

| Na2O | 24.5 | - | 6 | 9 | 23 | - | 6 |

| K2O | - | - | 12 | 3 | - | - | 12 |

| MgO | - | - | 5 | - | - | - | 5 |

| CaO | 24.5 | 32.6 | 20 | 19.7 | 20 | 28.6 | 20 |

Methods involved in the bioactive glass production

The melt quenching technique and the sol-gel process are the methods used for the production of bioactive glasses [40, 41]. By adjusting the compositional elements and manufacturing parameters of these approaches, researchers can produce a diverse array of specialized bio-glasses. Researchers have also employed other methods, such as flame spraying, to produce spherical glasses at the nanoscale level [42].

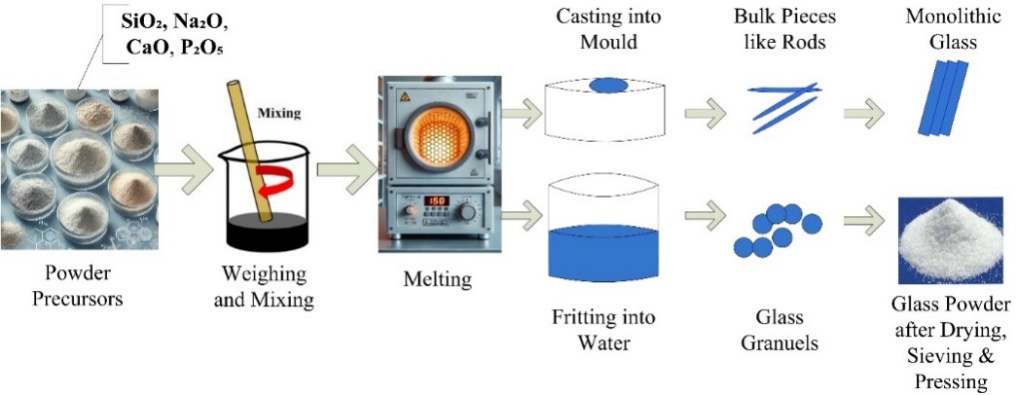

Melt quenching approach

The production of oxide glasses such as 45S5 initially relied on melting, as described in Hench's original methodology. This process requires appropriate amounts of various chemicals, typically in the powder form, such as nitrates, oxides, sulfates, and carbonates. The procedure involved selecting a suitable glass composition, weighing and mixing the components, and melting them at appropriate temperatures. Compared with silicate glasses, glasses made from borates and phosphates typically have lower melting temperatures [43]. When producing large-scale items, such as monoliths and rods, the uniform molten material transferred into appropriate molds and left to solidify. The molten glass cooled in cold water to produce a glass powder or frit. The resulting small glass fragments were dried, crushed, and sieved [44]. Fig. 1 illustrates the main steps of bioglass preparation using the melt-quenching method.

To meet the growing demand for bioactive glasses in healthcare and regenerative medicine, production methods must be optimized for scalability, efficiency, and cost-effectiveness while maintaining product quality. Key strategies for optimization includes lowering melting temperatures by refining glass compositions, particularly in borate and phosphate-based glasses, reduces energy costs. Implementing advanced furnace designs, such as electric or hybrid furnaces, can improve thermal efficiency and reduce emissions. Emerging additive manufacturing techniques enable the direct production of complex Bioglass scaffolds, minimizing material wastage and post-processing requirements. By implementing these optimizations, the production of bioactive glasses scaled up to industrial levels, meeting the increasing demand for biomedical applications [45].

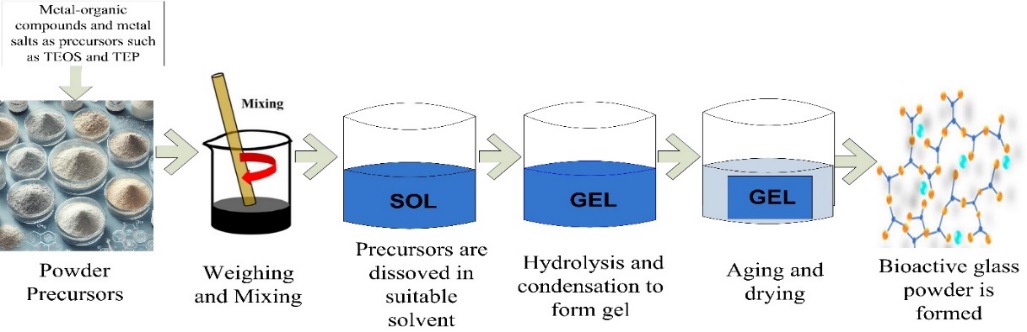

Sol-gel technique

Thomas Graham first coined the word "sol-gel" in 1864 [46]. His investigations into silica sols demonstrated that the interaction between tetraethyl orthosilicate [TEOS] and water results in hydrolysis and condensation processes, ultimately creating a silica network or gel. Graham observed that drying this gel yielded glassy SiO2. Subsequently, Professor L. L. Hench developed the sol-gel technique for manufacturing bioglass. This method offered a more effective and accurate approach to producing consistent structures in various forms, including membranes, composites, fibers, powders, and monoliths. This process initiates with the formation of a solution by mixing metal-organic compounds and metal salts as precursors. Following this, gel formation occurred through a series of hydrolysis and condensation reactions. The final step involves applying a heat treatment to dry the sol, which promotes the creation of oxides and removes organic components [26]. Many researchers prefer the sol-gel method overmelt quenching because of its versatility and capacity to overcome certain limitations.

Compared to melt quenching, the sol-gel technique offers numerous advantages as follows; it shows greater control over composition and morphology, less complex glass manufacturing equipment, prevention of unwanted alloy formation due to metal ion-crucible interactions comparatively lower production temperatures. These benefits outweigh the increased expense of the alkoxide precursors used in the sol-gel method. Furthermore, this approach enables the inclusion of heat-sensitive components in the glass structure [44]. Fig. 2 illustrates the main steps of bioglass preparation using the melt-quenching method.

To scale up the sol-gel process for industrial use, the following optimizations can be considered Explore alternative, cost-effective precursors while maintaining material quality. Automation of solution preparation, gelation, and drying processes to ensure consistency and reduce labor costs. Standardize parameters like pH, precursor ratios, and drying times for reproducible results at scale. Integrate energy-saving technologies such as low-energy dryers or microwave-assisted heating for gel drying and heat treatment. Combine the sol-gel method with 3D printing technologies directly fabricate customized bioglass scaffolds and implants, reducing post-processing requirements. Optimize solvent recovery and reuse during the sol-gel process. By addressing these areas, the sol-gel method effectively scaled for industrial production [49].

Fig. 1: Essential stages in producing bioglass using the melt-quenching technique

Fig. 2: Essential stages of the sol-gel process for synthesizing bioglass

Properties of bioglass

Bioactivity

Bioglass exhibits exceptional bioactivity, allowing it to establish connections with living tissues, especially the bone. Upon contact with bodily fluids, the bioglass surface undergoes a series of chemical reactions, resulting in the development of HCA layer. This layer closely resembles the mineral components of bone tissue. The ability to form this HCA layer is essential for bioglass applications in bone restoration and regeneration because it encourages the adhesion and growth of osteoblasts, the cells responsible for bone formation [50].

Biocompatibility

The biocompatibility of bioglass allows it to be safely used in contact with human tissues without causing adverse immune reactions. Its composition well tolerated by the body, making it suitable for both hard and soft tissue applications. bioglass degrades into ions that either used in physiological processes or easily excreted, thereby reducing the risk of toxicity. The compatibility of bioactive glasses with biological systems influenced by the silicate concentration in the glass composition. Optimal bonding between the graft and bone occurs when the silicate content falls within the range of 45-52% [50].

Osteoconductivity

Bioglass provides a scaffold that supports bone growth, which is a property known as osteoconductivity. This makes it ideal for applications in orthopedic implants and bone grafts, where it not only provides structural support but also enhances bone regeneration by guiding cell attachment and bone matrix deposition [51].

Controlled degradability

One of the unique advantages of BG is its ability to degrade at controlled rates, depending on its composition and structure. This degradability allows it gradually dissolve in the body, releasing beneficial ions [such as calcium and phosphate] that aid tissue repair. The degradation rate can be customized to align with the healing processes of various tissues by modifying the material composition [51].

Mechanical properties

Although bioglass is inherently brittle compared to metals and some polymers, its mechanical properties can be tailored to provide adequate strength for specific applications. For example, combining bioglass with polymers or metals creates composites that enhance durability and pliability, making them appropriate for applications that bear weight, such as bone implants. Research is ongoing to further enhance its mechanical properties to expand its usability [52].

Antibacterial properties

Substantial amounts of sodium, silica, calcium, and phosphate ions are liberated from the glass surface, resulting in an elevation of the surrounding pH and osmotic pressure, and has demonstrated its ability to kill bacteria across various strains, including Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Escherichia coli, and Klebsiella pneumonia [53].

Ram Sabarish Chandrasekar et al. conducted an in vitro research study to evaluate the antibacterial properties of Perioglas against Streptococcus salivarius, a common oral commensal and early colonizer. Different concentrations of Perioglas tested against the ATCC 13419 strain of S. salivarius. Antimicrobial activity assessed after 24 h of incubation at 37 °C by measuring the reduction in colony-forming units on culture plates and smears. The results demonstrated that bioactive glass (BAG) exhibited antibacterial effects against S. salivarius, with its efficacy increasing in a concentration-dependent manner [54].

Al-Jobory AI et al. investigated the antibacterial properties of 45S5 Bioglass along with chitosan as fillers in gutta-percha against Enterococcus faecalis. Antibacterial activity assessed by measuring the inhibition zone, which indicates microbial sensitivity or toxicity. The modified gutta-percha exhibited a highly significant antibacterial effect compared to the control group, which showed no microbial sensitivity. The results demonstrated that incorporating 45S5 Bioglass® and chitosan into gutta-percha significantly enhanced its antibacterial efficacy against Enterococcus faecalis in vitro compared to commercial available gutta-percha [55].

Certain formulations of bioglass, especially those doped with ions such as silver, zinc, or copper, exhibit antibacterial properties. This makes it valuable for coatings on implants and medical devices to prevent infections, particularly in orthopedic and dental applications, where infections can pose significant complications. Hammami Iet al. explores the significance of antibacterial implant coatings by incorporating copper into 45S5 Bioglass. Bioglasses containing varying concentrations of CuO (0 to 8 mol %) synthesized using the melt-quenching technique. Antibacterial activity was evaluated against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, revealing bacterial inhibition at 0.5 mol% CuO. These findings highlight that copper inclusion in bioglass enhances its potential as an implant coating, improving both antibacterial effectiveness and osteointegration properties [56].

Ionic release and therapeutic effects

As bioglass degrades, it releases ions, such as silicon, calcium, sodium, and phosphate, which can have therapeutic effects. For example, silicon ions known to stimulate osteoblast activity and enhance bone regeneration. Controlled ionic release can also influence cellular behavior by enhancing angiogenesis [formation of new blood vessels], which is important for wound healing [57].

A clinical study involving approximately 58 cases demonstrated that Bioglass 45S5 ability to release calcium, phosphate, and silica ions, promoting hydroxyapatite formation and bone regeneration. This can serve as an effective alternative for secondary alveolar bone grafting in patients with cleft lip and palate. Traditionally, these procedures rely on iliac crest bone harvesting, which is associated with donor site morbidity. Utilizing Bioglass 45S5 instead can minimize harvesting-related complications and streamline the surgical process [58].

In an in vivo rabbit model, bioglass scaffolds implanted in critical-sized calvarial defects released borate and calcium ions, leading to improved osteoblast activity and enhancing bone formation. This study evaluated the bone regeneration capacity of borate bioactive glass (1393B3) scaffolds with three different microstructures—trabecular, fibrous, and oriented. After 12 w, histomorphometric analysis and scanning electron microscopy assessed new bone formation, mineralization, and blood vessel area. Results showed that trabecular scaffolds achieved the highest bone regeneration (33% of the defect area), followed by oriented (23%) and fibrous (15%) structures [59].

Surface modification potential

Bioglass surfaces can modify to improve specific properties such as bioactivity, adhesion, and antibacterial capabilities. Surface modification techniques, including coating or functionalization with bioactive molecules, can enhance cell attachment and proliferation, making bioglass even more effective for tissue engineering applications [60].

Versatility in composition and formulation

Bioglass can tailored by altering its chemical composition, which alters its properties for various applications. It is available in different forms, such as powders, granules, fibers, and scaffolds, allowing flexibility in use across applications. Composites of bioglass with polymers, ceramics, or metals also been increasingly developed to enhance their properties for specific medical needs [12, 13].

Applications of bioglass in healthcare

Bioglass has a wide range of applications in healthcare owing to its unique bioactive and biocompatible properties. From bone regeneration to wound healing, bioglass is increasingly used as a material that not only provides structural support, but also interacts positively with biological tissues to promote healing. Below are the main areas where bioglass has shown significant potential.

Orthopedics and bone regeneration

Bone bonding attributed to the formation of a HCA layer on the glass surface, which develops as the glass dissolves and the ions released from the surface reprecipitate. Bioglass extensively utilized in bone tissue scaffolds due to its capacity to enhance cell adhesion, growth, and specialization. Functioning as a supportive scaffold, this material emulates the natural bone structure, fostering cellular attachment and the progressive formation of new tissue. Bone mineral is structurally similar to HCA, which thought to interact with collagen fibrils. This interaction believed to promote HCA's incorporation into the bone tissue of the host. Researchers have developed synthetic bone graft alternatives to reduce dependence on autografts, which are not only scarce, but also pose risks of pain and infection at the donor site [61].

Clinical applications of bioglass as bone graft

Bioglass 45S5, marketed as NovaBone [NovaBone Products LLC, Jacksonville, FL, USA], has been utilized in orthopedic and craniofacial reconstruction as a particulate material to address bone defects. The initial clinical application of bioglass involved cone-shaped monoliths designed to replace small bones in the middle ear of a patient. These bones deteriorate due to infection, resulting in hearing loss. The bioglass implant successfully restored the patient's hearing. The product, known as DOUEK MED™ [US Biomaterials, Alachua, FL], offers a range of glass cones of various sizes, allowing healthcare professionals to select the most appropriate option for each patient [62].

PerioGlas, the first bioglass particulate (90–710 µm), was introduced in 1993 by USBiomaterials (now NovaBone Products LLC) as a synthetic bone graft for treating jawbone defects caused by periodontal disease. In 2005, the FDA granted approval for NovaBone, for use in orthopedic applications for non-weight-bearing bone defects. Autograft and NovaBone were contrasted in posterior spinal fusion procedures. The patient's blood combined with NovaBone material before being applied to the intended site and metal hooks and screws were utilized to apply pressure on the surrounding vertebrae. With the primary advantage of not requiring a donor site, NovaBone functioned better throughout the 4-year follow-up period, with very less infections [2% vs. 5%] and mechanical defaults[2% vs. 7.5%] [63]. Another 45S5 glass product used to repair jawbone defects is Biogran [Biomet 3i, Palm Beach Gardens, FL] [64].

The S53P4 composition, a modified form of the 45S5 composition, now marketed as BonAlive [BonAlive Biomaterials; Turku, Finland]. The FDA granted approval for its use as an alternative to bone grafts in orthopedic procedures in 2008, following the authorization of the European Union in 2006 [65]. Currently, BonAlive used to treat chronic osteomyelitis, trauma, and synthetic bone grafting after tumor resection.

Application in bone defects from trauma

In cases of tibial fractures requiring joint realignment, autografts compared with S53P4 particles [0.83–3.15 mm]. Implants inserted into the subchondral bone cavities within the compressed porous osseous tissue and reinforced using metallic condylar plates and casts. A long-term investigation spanning 11 y revealed comparable bone regeneration and not showed any notable differences in articular depression. Additionally, after more than a decade few glassy particles remained visible. The increased silicon dioxide content in S53P4 compared to that in 45S5 is probably the reason for its reduced absorption [66].

Craniofacial application

Frontal sinus obliteration is a surgical technique used to eliminate the frontal sinuses. This procedure typically performed to address recurrent infections, head trauma, and tumor excision. Traditionally, fat has been used to fill defects; however, this method results in complications in many patients. Trials performed by using S53P4 and 13–93 glass particles in the size range of 0.5–1 mm demonstrated superior bone regeneration in both quantity and quality contrast to hydroxyapatite [synthetic]. Compared to 13-93, BonAlive [S53P4] exhibited more rapid bone formation, presumably due to the presence of magnesium in 13-93, which diminishes its bioactive properties [67].

Removal of benign bone tumors

In trials, BonAlive used to repair bone defects [1–30 cm3] in the hands, tibia, and humerus caused by benign bone tumor surgery. A14 y study compared S53P4 granules (1–4 mm, 14 patients) with autografts (11 patients) for treating bone defects (1–30 cm³) after benign bone tumor surgery in the hands, tibia, and humerus. S53P4-treated bones showed twice the cortical thickness compared to autografts, though some glass particles remained after 14 y [68]. The glass began degrading between 12–36 mo, stimulating bone remodeling, but it was slower when compared with autograft [69].

Sponpondylolisthesis

BonAlive granules of 1-2 mm utilized in clinical studies for patients with severe spondylolisthesis or displacement of the spinal column. Each patient had an autograft and glass [20–40 g, based on the amount required] inserted in the same location using a metal screw system; the vertebrae compressed to hold the implants in place between them. Eleven years later, the success rate for glass fusion was 88%, and while for autografts was 100%. The outcomes observed similar when treating osteomyelitis, a condition in which bacterial infection lowers the quality of the vertebral bone [70].

Application in dental products

Dental products, particularly toothpaste formulations, have successfully incorporated bioactive glasses, owing to their diverse benefits. These glasses are capable of releasing antibacterial agents, promoting remineralization, and alleviating tooth sensitivity [71]. NovaMin, a notable illustration, is a bioactive glass composed of calcium-sodium-phosphate silicate. This substance releases ions of calcium and phosphate, which results in an elevation of the oral environment's pH level [72]. This process results in calcium phosphate deposition, which then transforms into hydroxyapatite, contributing to the repair and reinforcement of the tooth enamel [73]. Biomin F combines fluoride with calcium and phosphate to enable the formation of fluorapatite [FAP]. This compound provides enhanced durability and resistance against dental decay, making it an effective choice for long-term oral health [74].

Application in periodontal therapy

Studies conducted on dogs have demonstrated that bioactive glass particles can aid in the restoration of periodontal irregularities by enhancing bone mineralization [75]. Due to its composition being identical to Bioglass 45S5, PerioGlass frequently employed as a bone graft material in the treatment of periodontal bone deficiencies [76]. Bioactive glass particles in PerioGlas, ranging from 90 to 710 μm in size, can effectively fill bone defects during periodontal procedures. Research has demonstrated that this substance promotes the regeneration of bone tissue, accelerates the formation of new bone, and displays significant bioactive properties [77].

Application in orthodontics

The use of bioactive glass coatings on implants can mitigate infection and inflammation risks owing to their innate antimicrobial properties. These glasses also improve the connection between the titanium implants and bone tissue, thereby shortening the overall treatment time [78]. Studies have indicated that orthodontic adhesives containing bioactive glass and fluoride strengthen the apatite structure, potentially inhibiting the formation of white-spot lesions [79]. Moreover, bioactive glasses have shown the ability to restore such lesions, which frequently emerge as a consequence of orthodontic bracket attachment [79, 80]. Notably, QMAT3 bioactive glass causes less enamel damage than Bioglass 45S5 when using air abrasion or tungsten carbide burs. Thus, QMAT3 is a more conservative method for removing orthodontic adhesives [81].

Application in endodontics

Root canal treatments have also incorporated bioactive glass. In a study involving rats, an innovative bioactive glass employed as a pulp-capping material for direct pulp-capping procedures [82]. Then findings demonstrated that bioactive glass promoted the formation of substantial dentin bridges and elicited inflammatory reactions comparable to those observed with mineral trioxide aggregate [MTA][83]. Gutta-percha combined with Bioglass 45S5 (Bio-Gutta) offers a viable alternative to traditional gutta-percha in root canal treatments as root fillers. Bio-Gutta is biocompatible and capable of bonding directly to dentin walls, and does not require sealers [84].

Application in oral and maxillofacial surgery

Research has shown that bioactive glass outperforms other calcium phosphate-based materials, including hydroxyapatite and tricalcium phosphate, in promoting bone formation during maxillofacial surgical procedures. This superior bone-forming capability of bioactive glass has been well documented in various studies. This results in rapid and high-quality bone regeneration [85]. Bioglass commercially introduced as a synthetic bone graft substitute for maxillofacial and orthopedic applications, under the brand names Perioglass and Novabone, respectively [86, 87].

Application in esthetic and restorative dentistry

The hydrodynamic theory suggests that dentin hypersensitivity discomfort alleviated by obstructing nerve endings or sealing the dentinal tubules [88]. Bioactive glasses offer an effective solution to dentin hypersensitivity pain by binding to collagen fibers and promoting the formation of hydroxyapatite, which effectively occludes dentinal tubules [89]. PerioGlas, in particular, shown to bond firmly with collagen and reduce dentin tenderness by occluding tubules [90].

Soft tissue repair

Regenerating soft tissues injured by trauma or pathological lesions using biomaterials is a well-established and promising therapeutic strategy. This characteristic attributed to the unique capacity of biomaterials featuring textured structures, specifically engineered compositions, and biocompatible mechanical properties to guide and direct endogenous or pre-seeded stem cells [91]. These materials encourage cell differentiation and aid the formation and restructuring of new tissues. Bioactive glasses [BGs] extensively studied in the field of soft-tissue regeneration. Studies have demonstrated that these substances have the potential to treat soft tissue injuries, including those in the heart, lungs, nerves, and epithelium [92].

Applications in cardiac tissue engineering

Studies have shown that bioactive glasses [BGs] hold promise for cardiac tissue regeneration, especially when used as nanoparticles integrated into soft matrices. Chen et al. [2008] conducted research aimed at creating polymeric cardiac patches designed to provide mechanical reinforcement and act as delivery systems for cells in tissue repair processes. The research team created elastomeric nanocomposites with varying concentrations [0–10 wt%] of 45S5 Bioglass nanoparticles combined with polyglycerol sebacate [PGS]. The PGS provided mechanical flexibility, whereas the glass nanoparticles enhanced the mechanical properties and functioned as cell anchors, facilitating their release into the physiological environment. Additionally, glass nanoparticles decreased the acidity of the PGS-nano-Bioglass scaffold, thereby improving biocompatibility [93]. Laboratory studies conducted on cardiomyocytes derived from human endometrial stromal cells demonstrated that PGS-nano-Bioglass showed greater compatibility with living tissues than PGS alone, indicating its possible use in cardiac tissue engineering [94].

Applications in lung tissue engineering

Patients with conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], pulmonary hyperextension, and cystic fibrosis often face challenges owing to the limited capacity of the lungs for self-repair. This limitation frequently necessitates lung transplantation as a treatment option. Researchers have proposed the use bioactive glasses [BGs] in tissue engineering as a potential alternative. Tan et al. conducted an innovative research project investigating the biocompatibility of 58S bioactive glass scaffolds produced through sol-gel methods. These scaffolds were enhanced with amines, mercaptan groups, or laminin, and their compatibility was evaluated using MLE-12 cells, which are murine lung epithelial cells. The findings showed that pulmonary cells effectively populated all types of scaffolds, suggesting compatibility with biological systems and facilitating cellular attachment and growth [95].

Applications in nerve tissue engineering

Bioactive glasses [BGs] have shown considerable promise in the field of nervous tissue engineering. The initial research work involving in vivo study employing bioglass focused on reconstructing sheep facial nerves. Scientists have developed dissolvable phosphate glass tubes, which are inserted into the epineurium through openings at both nerve ends. Following a three-month period, the glass tubes had completely dissolved, and full nerve regeneration observed [96].

Wound healing

The healing of chronic wounds is a complicated process influenced by various factors, including inadequate blood flow, inflammation, infection, and coexisting conditions, such as diabetes [97]. This complexity necessitates a comprehensive approach involving multiple disciplines and advanced treatment. Bioglass shows promising results in addressing the above issues by supporting critical phases of wound healing, including blood vessel formation. Bioglass-based formulations, including nanocomposites like scaffolds and hydrogels, generate favorable conditions for tissue regeneration, reduces scar formation, and regulate inflammatory responses [98]. Hydrogels serve as moist wound dressings and can adsorb and remove dead tissue, aiding wound healing. Resorbable hydrogels, resembling natural tissues, have become widely used as scaffolds in tissue engineering [99].

Bioglass has demonstrated promising potential in wound healing applications owing to its compatibility with biological systems, ability to release ions, and antimicrobial properties. Bioactive glasses [BGs] possess a chemical makeup that makes them appropriate for use as scaffolds to accelerate wound healing. These substances can enhance the expression of genes associated with healing, including vascular endothelial growth factor [VEGF], basic fibroblast growth factor [bFGF], and vascular cell adhesion protein [VCAM]. Additionally, 45S5 Bioglass shown to safeguard endothelial cells and improve gap junctions, thereby accelerating the wound healing process [92].

Table 2: Applications of various Bioglass in various fields of health care listed

| S. No. | Field of application | Type of bioglass/Brand name | Applications | Reference |

| 1 | Dental field | 45S5 | Detaching residual orthodontic adhesive, pulp capping substance, and artificial bone graft. | [71] |

| Novamin | Delivery of antimicrobial agents, combat gingivitis, promote remineralization, and decrease tooth sensitivity. | [73] | ||

| BiominF | Restoring mineral content in artificial dental caries, occlusion of dentinal tubules. | [74] | ||

| Perioglas | Serving as a bone grafts to restore periodontal bone deficiencies. | [76] | ||

| QMAT3 | Inhibiting the development of white spot lesions and exhibiting enhanced antimicrobial and remineralizing capabilities. | [81] | ||

| 2 | Orthopaedics and bone regeneration | S53P4 [BonAlive] | To treat chronic osteomyelitis, trauma, and synthetic bone grafting after tumor resection, in sinus obliteration to fill the defect. | [85, 86] |

| NovaBone | Glass cones to replace a patient's middle ear's tiny bones, non-load-bearing bone grafts, orthopedic trauma, posterior spinal fusion procedures, | [62] | ||

| Biogran | Bone regeneration in orthopedic surgery and to repair jawbone | [64] | ||

| 3 | Soft tissue repair | 13-93 B3 borate glass microfiber, phosphate glass tubes | Neuronal tissue regeneration | [96] |

| 58S bioactive glass | Lung tissue engineering | [95] | ||

| PGS-nano-Bioglass scaffold | Cardiac tissue engineering | |||

| 4 | Wound healing | 45S5 Bioglass | Wound dressing causes cell proliferation and angiogenesis, Inhibit the formation of scar tissue, and regulate inflammatory responses | [94] |

| MIRRAGEN [Borate based wound dressing] | Diabetic pressure, trauma wounds, vascular ulcers, surgical incisions and burns | [102] | ||

| Dermfactor | Chronic wounds, diabetic ulcer, surgical incisions, burns and bedsores | [102] | ||

| Arglaes, Phosphate [Ag dopped] | Full-thickness wounds, management of infection | [103] | ||

| Rediheal Borate [Cu dopped] animal use |

Promote angiogenesis, trauma wounds, surgical wounds, pressure sores, chronic and soft tissue wounds | [102] |

Studies conducted by Li et al. demonstrated that ion extracts from 45S5 Bioglass can enhance wound healing in both laboratory and animal experiments by encouraging the production of connexin 43 [Cx43], a protein crucial for gap junction intercellular communication. The most thoroughly investigated BGs for wound healing applications are silicate-based glasses, which increase the local pH and display antimicrobial effects [100]. BGs enriched with ions such as silver, copper, or zinc possess inherent antibacterial properties, making them beneficial for the treatment of chronic or infected wounds, and help suppress bacterial growth and reduce infection risks, which are especially important in hospital environments [101].

CONCLUSION

Bioglass emerged as a renowned material which has transformed health care sector, for its exceptional bioactivity, biocompatibility, and versatility. Recent innovations in bioactive glasses, including borate, borosilicate, and phosphate compositions, have opened new avenues for tissue engineering applications. Through advanced processing techniques and compositional adjustments, researchers are tailoring bioglass to meet specific therapeutic needs, yielding more effective and adaptable solutions for both hard and soft tissue repair.

One of the major limitations of bioglass, particularly in load-bearing applications, is its inherent brittleness. Unlike natural bone, which has a combination of strength and flexibility due to its composite structure, traditional bioglass lacks fracture toughness and tends to crack under mechanical stress. This restricts its use in high-load areas such as long bones and weight-bearing joints. Future research aims to capitalize on bioglass's advantageous properties while mitigating its brittleness through innovative scaffold design and processing, combining bioglass with polymers and 3D printing and bio-fabrication. Its applications extend to wound care, particularly in reducing amputations from diabetic ulcers and addressing sports injuries like cruciate ligament damage and cartilage tears. Futher research should be extended in customization of bioglass through the incorporation of therapeutic ions for controlled drug release, targeted cancer therapies, and tissue regeneration in more complex anatomical structures. Recent advancements, such as the integration of nanotechnology and 3D printing, have facilitated the development of bioglass-based materials with customized properties enabling implants and scaffolds for individual patients' needs and various applications.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors have contributed equally

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Authors declare no conflict of interest amongst themselves.

REFERENCES

Hoppe A, Boccaccini AR. Bioactive glasses as carriers of therapeutic ions and the biological implications. In: Boccaccini AR, Brauer DS, Hupa L, editors. Bioactive glasses: fundamentals technology and applications. Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry; 2016. p. 362-92. doi: 10.1039/9781782622017-00362.

Ali S, Farooq I, Iqbal K. A review of the effect of various ions on the properties and the clinical applications of novel bioactive glasses in medicine and dentistry. Saudi Dent J. 2014 Jan 1;26(1):1-5. doi: 10.1016/j.sdentj.2013.12.001, PMID 24526822.

Zhao X, Courtney JM, Qian H, editors. Bioactive materials in medicine: design and applications. Elsevier; 2011 May 25.

Cannio M, Bellucci D, Roether JA, Boccaccini DN, Cannillo V. Bioactive glass applications: a literature review of human clinical trials. Materials (Basel). 2021 Sep 20;14(18):5440. doi: 10.3390/ma14185440, PMID 34576662.

Hench LL. Bioactive materials: the potential for tissue regeneration. J Biomed Mater Res. 1998;41(4):511-8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(19980915)41:4<511::aid-jbm1>3.0.co;2-f, PMID 9697022.

Hench LL, Polak JM. Third-generation biomedical materials. Science. 2002;295(5557):1014-7. doi: 10.1126/science.1067404, PMID 11834817.

Jones JR. Reprint of: review of bioactive glass: from hench to hybrids. Acta Biomater. 2015;23Suppl:S53-82. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2015.07.019, PMID 26235346.

Hench LL. Biomaterials: a forecast for the future. Biomaterials. 1998 Aug 1;19(16):1419-23. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(98)00133-1, PMID 9794512.

Hench LL, Splinter RJ, Allen WC, Greenlee TK. Bonding mechanisms at the interface of ceramic prosthetic materials. J Biomed Mater Res. 1971 Nov;5(6):117-41. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820050611.

Baino F, Fiorilli S, Vitale Brovarone C. Bioactive glass-based materials with hierarchical porosity for medical applications: review of recent advances. Acta Biomater. 2016 Sep 15;42:18-32. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2016.06.033, PMID 27370907.

Islam MT, Felfel RM, Abou Neel EA, Grant DM, Ahmed I, Hossain KM. Bioactive calcium phosphate-based glasses and ceramics and their biomedical applications: a review. J Tissue Eng. 2017 Jul 18;8:2041731417719170. doi: 10.1177/2041731417719170, PMID 28794848.

Hoppe A, Güldal NS, Boccaccini AR. A review of the biological response to ionic dissolution products from bioactive glasses and glass ceramics. Biomaterials. 2011 Apr 1;32(11):2757-74. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.01.004, PMID 21292319.

Kaur G, Pandey OP, Singh K, Homa D, Scott B, Pickrell G. A review of bioactive glasses: their structure, properties, fabrication and apatite formation. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2014 Jan;102(1):254-74. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34690, PMID 23468256.

Baino F, Novajra G, Miguez Pacheco V, Boccaccini AR, Vitale Brovarone C. Bioactive glasses: special applications outside the skeletal system. J Non Crystal Solids. 2016 Jan 15;432:15-30. doi: 10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2015.02.015.

Jones JR. Review of bioactive glass: from Hench to hybrids. Acta Biomater. 2013 Jan 1;9(1):4457-86. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.08.023, PMID 22922331.

Rust KR, Singleton GT, Wilson J, Antonelli PJ. Bioglass middle ear prosthesis: long-term results. Am J Otol. 1996;17(3):371-4. PMID 8817012.

Vitale Brovarone C, Novajra G, Lousteau J, Milanese D, Raimondo S, Fornaro M. Phosphate glass fibres and their role in neuronal polariza-tion and axonal growth direction. Acta Biomater. 2012 Mar;8(3):1125-36. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.11.018.

Baino F, Vitale Brovarone C. Three-dimensional glass-derived scaffolds for bone tissue engineering: current trends and forecasts for the future. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2011;97(4):514-35. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.33072, PMID 21465645.

Chen QZ, Thompson ID, Boccaccini AR. 45S5 Bioglass derived glass ceramic scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2006 Apr 1;27(11):2414-25. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.11.025, PMID 16336997.

Jones JR, Ehrenfried LM, Hench LL. Optimising bioactive glass scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2006;27(7):964-73. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.07.017, PMID 16102812.

Gupta S, Majumdar S, Krishnamurthy S. Bioactive glass: a multifunctional delivery system. J Control Release. 2021 Jul 10;335:481-97. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.05.043, PMID 34087250.

Day RM, Boccaccini AR, Shurey S, Roether JA, Forbes A, Hench LL. Assessment of polyglycolic acid mesh and bioactive glass for soft tissue engineering scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2004;25(27):5857-66. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.01.043, PMID 15172498.

Wang M. Developing bioactive composite materials for tissue replacement. Biomaterials. 2003;24(13):2133-51. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00037-1, PMID 12699650.

Huang J. Design and development of ceramics and glasses. In: Biology and engineering of stem cell niches. Elsevier; 2017 Jan 1. p. 315-29. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-802734-9.00020-2.

Pawar V, Shinde V. Bioglass and hybrid bioactive material: a review on the fabrication, therapeutic potential and applications in wound healing. Hybrid Adv. 2024 Apr 26;6:100196. doi: 10.1016/j.hybadv.2024.100196.

Brauer DS, Moncke D. Introduction to the structure of silicate phosphate and borate glasses. In: Boccaccini AR, Brauer DS, Hupa L, editors. Bioactive glasses: fundamentals technology and applications. Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry; 2016. p. 61-88. doi: 10.1039/9781782622017-00061.

Fabbri P, Cannillo V, Sola A, Dorigato A, Chiellini F. Highly porous polycaprolactone-45S5 Bioglass® scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Compos Sci Technol. 2010 Nov 15;70(13):1869-78. doi: 10.1016/j.compscitech.2010.05.029.

Osipov AA, Osipova LM. Boson peak and superstructural groups in Na2O-B2O3 glasses. Adv Condens Matter Phys. 2018 Jan 1;2018:1-8. doi: 10.1155/2018/6746023.

Brown RF, Rahaman MN, Dwilewicz AB, Huang W, Day DE, Li Y. Effect of borate glass composition on its conversion to hydroxyapatite and on the proliferation of MC3T3-E1 cells. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2009;88(2):392-400. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31679, PMID 18306284.

Fu Q, Rahaman MN, Bal BS, Bonewald LF, Kuroki K, Brown RF. Silicate borosilicate and borate bioactive glass scaffolds with controllable degradation rate for bone tissue engineering applications. II. In vitro and in vivo biological evaluation. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2010;95(1):172-9. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32823, PMID 20540099.

Zhao S, Li L, Wang H, Zhang Y, Cheng X, Zhou N. Wound dressings composed of copper-doped borate bioactive glass microfibers stimulate angiogenesis and heal full-thickness skin defects in a rodent model. Biomaterials. 2015 Jun 1;53:379-91. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.02.112, PMID 25890736.

Balasubramanian P, Hupa L, Jokic B, Detsch R, Grunewald A, Boccaccini AR. Angiogenic potential of boron-containing bioactive glasses: in vitro study. J Mater Sci. 2017 Aug;52(15):8785-92. doi: 10.1007/s10853-016-0563-7.

Naseri S, Lepry WC, Nazhat SN. Bioactive glasses in wound healing: hope or hype? J Mater Chem B. 2017;5(31):6167-74. doi: 10.1039/c7tb01221g, PMID 32264432.

Rahaman MN, Day DE, Bal BS, Fu Q, Jung SB, Bonewald LF. Bioactive glass in tissue engineering. Acta Biomater. 2011 Jun 1;7(6):2355-73. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.03.016, PMID 21421084.

Ding H, Zhao CJ, Cui X, Gu YF, Jia WT, Rahaman MN. A novel injectable borate bioactive glass cement as an antibiotic delivery vehicle for treating osteomyelitis. PLOS One. 2014 Jan 10;9(1):e85472. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085472, PMID 24427311.

Brow RK. Review: the structure of simple phosphate glasses. J Non-Crystal Solids. 2000 Mar 1;263-264:1-28. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3093(99)00620-1.

Fernandes HR, Gaddam A, Rebelo A, Brazete D, Stan GE, Ferreira JM. Bioactive glasses and glass ceramics for healthcare applications in bone regeneration and tissue engineering. Materials (Basel). 2018 Dec 12;11(12):2530. doi: 10.3390/ma11122530, PMID 30545136.

Knowles JC. Phosphate-based glasses for biomedical applications. J Mater Chem. 2003;13(10):2395-401. doi: 10.1039/b307119g.

Abou Neel EA, Pickup DM, Valappil SP, Newport RJ, Knowles JC. Bioactive functional materials: a perspective on phosphate based glasses. J Mater Chem. 2009;19(6):690-701. doi: 10.1039/B810675D.

Bahniuk MS, Pirayesh H, Singh HD, Nychka JA, Unsworth LD. Bioactive glass 45S5 powders: effect of synthesis route and resultant surface chemistry and crystallinity on protein adsorption from human plasma. Biointerphases. 2012 Dec 1;7(1-4):41. doi: 10.1007/s13758-012-0041-y, PMID 22669582.

Pirayesh H, Nychka JA. Sol-gel synthesis of bioactive glass ceramic 45S5 and its in vitro dissolution and mineralization behavior. J Am Ceram Soc. 2013 May;96(5):1643-50. doi: 10.1111/jace.12190.

Strobel LA, Hild N, Mohn D, Stark WJ, Hoppe A, Gbureck U. Novel strontium-doped bioactive glass nanoparticles enhance proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of human bone marrow stromal cells. J Nanopart Res. 2013;15(7):9. doi: 10.1007/s11051-013-1780-5.

Bengisu M. Borate glasses for scientific and industrial applications: a review. J Mater Sci. 2016;51(5):2199-242. doi: 10.1007/s10853-015-9537-4.

O Donnell MD. Melt-derived bioactive glass. In: Jones JR, Clare AG, editors. Bio‐glasses: an introduction. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 2012 Aug 1. p. 13-27. doi: 10.1002/9781118346457.ch2.

Fiume E, Migneco C, Verne E, Baino F. Comparison between bioactive sol-gel and melt-derived glasses/glass ceramics based on the multicomponent SiO2−P2O5−CaO−MgO−Na2O−K2O system. Materials (Basel). 2020 Jan 23;13(3):540. doi: 10.3390/ma13030540, PMID 31979302.

Graham T. XXXV-on the properties of silicic acid and other analogous colloidal substances. J Chem Soc. 1864;17(318):318-27. doi: 10.1039/JS8641700318.

Foroutan F, Kyffin BA, Abrahams I, Corrias A, Gupta P, Velliou E. Mesoporous phosphate-based glasses prepared via sol-gel. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2020;6(3):1428-37. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.9b01896, PMID 33455383.

Lepry WC, Nazhat SN. Highly bioactive sol-gel-derived borate glasses. Chem Mater. 2015;27(13):4821-31. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.5b01697.

Shoushtari MS, Hoey D, Biak DR, Abdullah N, Kamarudin S, Zainuddin HS. Sol-gel-templated bioactive glass scaffold: a review. Res Biomed Eng. 2024 Mar;40(1):281-96. doi: 10.1007/s42600-024-00342-x.

Krishnan V, Lakshmi T. Bioglass: a novel biocompatible innovation. J Adv Pharm Technol Res. 2013 Apr 1;4(2):78-83. doi: 10.4103/2231-4040.111523, PMID 23833747.

Hupa L. Melt-derived bioactive glasses. In: Bioactive glasses. Elsevier; 2011 Jan 1. p. 3-28. doi: 10.1533/9780857093318.1.3.

Ferrando A, Part J, Baeza J. Treatment of cavitary bone defects in chronic osteomyelitis: biogactive glass s53p4 vs. calcium sulphate antibiotic beads. J Bone Jt Infect. 2017 Oct 9;2(4):194-201. doi: 10.7150/jbji.20404, PMID 29119078.

Gergely I, Zazgyva A, Man A, Zuh SG, Pop TS. The in vitro antibacterial effect of S53P4 bioactive glass and gentamicin impregnated polymethylmethacrylate beads. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung. 2014 Jun 1;61(2):145-60. doi: 10.1556/AMicr.61.2014.2.5, PMID 24939683.

Chandrasekar RS, Lavu V, Kumar K, Rao SR. Evaluation of antimicrobial properties of bioactive glass used in regenerative periodontal therapy. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2015 Sep 1;19(5):516-9. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.167166, PMID 26644717.

Al Jobory AI, Al Hashimi R. Antibacterial activity of bioactive glass 45S5 and chitosan incorporated as fillers into gutta percha. J Res Med Dent Sci. 2021;9(3):108-17.

Hammami I, Gavinho SR, Jakka SK, Valente MA, Graca MP, Padua AS. Antibacterial biomaterial based on bioglass modified with copper for implants coating. J Funct Biomater. 2023 Jul 13;14(7):369. doi: 10.3390/jfb14070369, PMID 37504864.

Sergi R, Bellucci D, Salvatori R, Anesi A, Cannillo V. A novel bioactive glass containing therapeutic ions with enhanced biocompatibility. Materials (Basel). 2020 Oct 15;13(20):4600. doi: 10.3390/ma13204600, PMID 33076580.

Graillon N, Degardin N, Foletti JM, Seiler M, Alessandrini M, Gallucci A. Bioactive glass 45S5 ceramic for alveolar cleft reconstruction about 58 cases. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2018 Oct 1;46(10):1772-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2018.07.016, PMID 30082167.

Bi L, Rahaman MN, Day DE, Brown Z, Samujh C, Liu X. Effect of bioactive borate glass microstructure on bone regeneration, angiogenesis and hydroxyapatite conversion in a rat calvarial defect model. Acta Biomater. 2013 Aug 1;9(8):8015-26. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.04.043, PMID 23643606.

Miola M, Vitale Brovarone C, Mattu C, Verne E. Antibiotic loading on bioactive glasses and glass ceramics: an approach to surface modification. J Biomater Appl. 2013 Aug;28(2):308-19. doi: 10.1177/0885328212447665, PMID 22684515.

Oonishi HL, Hench LL, Wilson J, Sugihara F, Tsuji E, Kushitani S. Comparative bone growth behavior in granules of bioceramic materials of various sizes. J Biomed Mater Res. 1999 Jan;44(1):31-43. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199901)44:1<31::aid-jbm4>3.0.co;2-9, PMID 10397902.

Hench LL. Bioactive materials for gene control. New Mater Technol Healthc. 2011. p. 25-48. doi: 10.1142/9781848165595_0003.

Jones JR, Brauer DS, Hupa L, Greenspan DC. Bioglass and bioactive glasses and their impact on healthcare. Int J Appl Glass Sci. 2016 Dec;7(4):423-34. doi: 10.1111/ijag.12252.

Schepers EJ, Ducheyne P. Bioactive glass particles of narrow size range for the treatment of oral bone defects: a 1-24 mo experiment with several materials and particle sizes and size ranges. J Oral Rehabil. 1997 Mar;24(3):171-81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.1997, PMID 9131472.

Andersson H, Liu G, Karlsson KH, Niemi L, Miettinen J, Juhanoja J. In vivo behaviour of glasses in the SiO2-Na2O-CaO-P2O5-Al2O3-B2O3 system. J Mater Sci: Mater Med. 1990;1(4):219-27. doi: 10.1007/BF00701080.

Lindfors NC, Koski I, Heikkila JT, Mattila K, Aho AJ. A prospective randomized 14 y follow-up study of bioactive glass and autogenous bone as bone graft substitutes in benign bone tumors. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2010 Jul;94(1):157-64. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31636, PMID 20524190.

Peltola M, Aitasalo K, Suonpaa J, Varpula M, Yli-Urpo A. Bioactive glass S53P4 in frontal sinus obliteration: a long-term clinical experience. Head Neck. 2006 Sep;28(9):834-41. doi: 10.1002/hed.20436, PMID 16823870.

Lindfors NC, Koski I, Heikkila JT, Mattila K, Aho AJ. A prospective randomized 14-y follow up study of bioactive glass and autogenous bone as bone graft substitutes in benign bone tumors. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2010 Jul;94(1):157-64. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31636, PMID 20524190.

Lindfors NC, Heikkila JT, Koski I, Mattila K, Aho AJ. Bioactive glass and autogenous bone as bone graft substitutes in benign bone tumors. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2009 Jul;90(1):131-6. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31263, PMID 18988277.

Frantzen J, Rantakokko J, Aro HT, Heinanen J, Kajander S, Gullichsen E. Instrumented spondylodesis in degenerative spondylolisthesis with bioactive glass and autologous bone: a prospective 11-y follow-up. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2011 Oct 1;24(7):455-61. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e31822a20c6, PMID 21909036.

Skallevold HE, Rokaya D, Khurshid Z, Zafar MS. Bioactive glass applications in dentistry. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 Nov 27;20(23):5960. doi: 10.3390/ijms20235960, PMID 31783484.

Gjorgievska E, Nicholson JW. Prevention of enamel demineralization after tooth bleaching by bioactive glass incorporated into toothpaste. Aust Dent J. 2011 Jun;56(2):193-200. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2011.01323.x, PMID 21623812.

Burwell AK, Litkowski LJ, Greenspan DC. Calcium sodium phosphosilicate (NovaMin): remineralization potential. Adv Dent Res. 2009 Aug;21(1):35-9. doi: 10.1177/0895937409335621, PMID 19710080.

Brauer DS, Karpukhina N, O Donnell MD, Law RV, Hill RG. Fluoride-containing bioactive glasses: effect of glass design and structure on degradation pH and apatite formation in simulated body fluid. Acta Biomater. 2010 Aug 1;6(8):3275-82. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.01.043, PMID 20132911.

Felipe ME, Andrade PF, Novaes Jr AB, Grisi MF, Souza SL, Taba Jr M. Potential of bioactive glass particles of different size ranges to affect bone formation in interproximal periodontal defects in dogs. J Periodontol. 2009 May;80(5):808-15. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.080583, PMID 19405835.

Lovelace TB, Mellonig JT, Meffert RM, Jones AA, Nummikoski PV, Cochran DL. Clinical evaluation of bioactive glass in the treatment of periodontal osseous defects in humans. J Periodontol. 1998 Sep;69(9):1027-35. doi: 10.1902/jop.1998.69.9.1027, PMID 9776031.

Profeta AC, Prucher GM. Bioactive glass in periodontal surgery and implant dentistry. Dent Mater J. 2015 Oct 2;34(5):559-71. doi: 10.4012/dmj.2014-233, PMID 26438980.

Civantos A, Martinez Campos E, Ramos V, Elvira C, Gallardo A, Abarrategi A. Titanium coatings and surface modifications: toward clinically useful bioactive implants. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2017;3(7):1245-61. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.6b00604, PMID 33440513.

Gange P. The evolution of bonding in orthodontics. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2015;147(4)Suppl:S56-63. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2015.01.011, PMID 25836345.

Milly H, Festy F, Watson TF, Thompson I, Banerjee A. Enamel white spot lesions can remineralise using bio-active glass and polyacrylic acid-modified bio-active glass powders. J Dent. 2014;42(2):158-66. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2013.11.012, PMID 24287257.

Taha AA, Hill RG, Fleming PS, Patel MP. Development of a novel bioactive glass for air-abrasion to selectively remove orthodontic adhesives. Clin Oral Investig. 2018;22(4):1839-49. doi: 10.1007/s00784-017-2279-8, PMID 29185145.

Gholami S, Labbaf S, Houreh AB, Ting HK, Jones JR, Esfahani MH. Long term effects of bioactive glass particulates on dental pulp stem cells in vitro. Biomed Glasses. 2017;3(1):96-103. doi: 10.1515/bglass-2017-0009.

Long Y, Liu S, Zhu L, Liang Q, Chen X, Dong Y. Evaluation of pulp response to novel bioactive glass pulp capping materials. J Endod. 2017;43(10):1647-50. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2017.03.011, PMID 28864220.

Belladonna FG, Calasans Maia MD, Novellino Alves AT, De Brito Resende RF, Souza EM, Silva EJ. Biocompatibility of a self-adhesive gutta-percha-based material in subcutaneous tissue of mice. J Endod. 2014;40(11):1869-73. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2014.07.013, PMID 25190606.

Peltola MJ, Aitasalo KM, Suonpaa JT, Yli-Urpo A, Laippala PJ, Forsback AP. Frontal sinus and skull bone defect obliteration with three synthetic bioactive materials. A comparative study. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2003;66(1):364-72. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.10023, PMID 12808596.

Fetner AE, Hartigan MS, Low SB. Periodontal repair using PerioGlas in nonhuman primates: clinical and histologic observations. Compendium. 1994;15(7):935-8. PMID 7728821.

Elshahat A. Correction of craniofacial skeleton contour defects using bioactive glass particles. Egypt J Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;30(2):113-9.

Orchardson R, Gillam DG. The efficacy of potassium salts as agents for treating dentin hypersensitivity. J Orofac Pain. 2000;14(1):9-19. PMID 11203743.

Gillam DG. Clinical trial designs for testing of products for dentine hypersensitivity a review. J West Soc Periodontol Periodontal Abstr. 1997;45(2):37-46. PMID 9477867.

Montazerian M, Zanotto ED. A guided walk through Larry Hench’s monumental discoveries. J Mater Sci. 2017;52(15):8695-732. doi: 10.1007/s10853-017-0804-4.

Yu H, Peng J, Xu Y, Chang J, Li H. Bioglass activated skin tissue engineering constructs for wound healing. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016 Jan 13;8(1):703-15. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b09853, PMID 26684719.

Kargozar S, Hamzehlou S, Baino F. Can bioactive glasses be useful to accelerate the healing of epithelial tissues? Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2019 Apr 1;97:1009-20. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2019.01.028, PMID 30678892.

Chen QZ, Harding SE, Ali NN, Lyon AR, Boccaccini AR. Biomaterials in cardiac tissue engineering: ten years of research survey. Mater Sci Eng R Rep. 2008 Feb 29;59(1-6):1-37. doi: 10.1016/j.mser.2007.08.001.

Kargozar S, Hamzehlou S, Baino F. Potential of bioactive glasses for cardiac and pulmonary tissue engineering. Materials (Basel). 2017 Dec 15;10(12):1429. doi: 10.3390/ma10121429, PMID 29244726.

Tan A, Romanska HM, Lenza R, Jones JR, Hench LL, Polak JM. The effect of 58S bioactive sol-gel derived foams on the growth of murine lung epithelial cells. Key Eng Mater. 2003;240-242:719-24. doi: 10.4028/www.scientific.net/KEM.240-242.719.

Gilchrist T, Glasby MA, Healy DM, Kelly G, Lenihan DV, McDowall KL. In vitro nerve repair in vivo. The reconstruction of peripheral nerves by entubulation with biodegradeable glass tubes a preliminary report. Br J Plast Surg. 1998 Jan 1;51(3):231-7. doi: 10.1054/bjps.1997.0243, PMID 9664883.

Varghese R, RV, Shinde. Therapeutic potential of novel phyto-medicine from natural origin for accelerated wound healing. Int J Pharmacogn. 2021;8(1):14-24. doi: 10.13040/IJPSR.0975-8232.

Mehrabi T, Mesgar AS, Mohammadi Z. Bioactive glasses: a promising therapeutic ion release strategy for enhancing wound healing. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2020;6(10):5399-430. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.0c00528, PMID 33320556.

Rao TR, Chvs P, MY, CH P. Hydrogels the three-dimensional networks: a review. Int J Curr Pharm Sci. 2021;13(1):12-7. doi: 10.22159/ijcpr.2021v13i1.40823.

Xu H, LV F, Zhang Y, Yi Z, Ke Q, Wu C. Hierarchically micro-patterned nanofibrous scaffolds with a nanosized bio-glass surface for accelerating wound healing. Nanoscale. 2015 Nov 5;7(44):18446-52. doi: 10.1039/C5NR04802H, PMID 26503372.

Li H, He J, Yu H, Green CR, Chang J. Bioglass promotes wound healing by affecting gap junction connexin 43 mediated endothelial cell behavior. Biomaterials. 2016 Apr 1;84:64-75. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.01.033, PMID 26821121.

Banijamali S, Heydari M, Mozafari M. Cellular response to bioactive glasses and glass ceramics. In: InHandbook of biomaterials biocompatibility. Elsevier; 2020 Jan 1. p. 395-421. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-08-102967-1.00019-0.

Chen S, Huan Z, Zhang L, Chang J. The clinical application of a silicate-based wound dressing (DermFactor®) for wound healing after anal surgery: a randomized study. Int J Surg. 2018 Apr 1;52:229-32. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.02.036, PMID 29481992.