Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 3, 2025, 328-335Original Article

MOLECULAR DOCKING AND DYNAMIC SIMULATION ON PLA2, NIK, COX-2, AND IRAK-4 INHIBITORS AS ANTIPHLOGISTIC AGENTS IN ZINGIBER OFFICINALIS

CHAYA H.1, CHAYA P. L.1, AKSHATHA MUDIGERE1, JANE B. MATHEW1*, ZAKIYA FATHIMA1, DURGESH PARESH BIDYE2, SHESHAGIRI DIXIT2

1Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, NGSM Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, NITTE, (Deemed to be University), Paneer, Deralakatte, Karnataka-575018, India. 2Computer Aided Drug Design Laboratory, Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, JSS College of Pharmacy Mysore, JSS Academy of Higher Education and Research, Mysore-570015, Karnataka, India

*Corresponding author: Jane B. Mathew; *Email: janej@nitte.edu.in

Received: 17 Dec 2024, Revised and Accepted: 06 Mar 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: Zingiber officinalis (ginger) rhizomes are widely recognised for their health benefits, but the leaves, primarily used as flavouring agents, have not been explored for therapeutic potential. This study investigates the antiphlogistic properties of Z. Officinalis leaf constituents through molecular docking and dynamic simulation of 24 bioactive molecules identified via Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectroscopy (GC-MS), with a focus on pro-inflammatory gene suppression and inflammatory cell apoptosis induction.

Methods: Docking studies were conducted using Schrödinger software (version 2023-1) on secondary metabolites from aqueous and methanolic extracts of Z. officinalis leaves against Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), Interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase-4 (IRAK-4), Phospholipase A2 (PLA2), and NF-kB-inducing kinase (NF-kB) targets. Physicochemical and pharmacokinetic properties were assessed with the QikProp module. MMGBSA simulations evaluated protein-ligand interactions, and molecular dynamics assessed protein adaptation under physiological conditions.

Results: Compound Pterin-6-carboxylic acid exhibited an excellent docking score with the target NF-kB compared to standard Diclofenac. Compounds such as Cyclopropane pentanoic acid 2-undecyl and 14-pentyl bicyclohexyl-4-carbonamide showed docking scores of-8.586 kcal/mol and-7.759 kcal/mol, respectively, against COX-2 and IRAK-4. Cyclopropane pentanoic acid 2-undecyl also demonstrated a score of-7.279 kcal/mol against IRAK-4. MMGBSA showed consistent binding free energies, and pharmacokinetic properties were within acceptable limits. The simulation study generated the stability of the protein-ligand complex and found that Pterin-6-carboxylic acid showed a stable complex with 4UY1.

Conclusion: Pterin-6-carboxylic acid and Cyclopropane pentanoic acid 2-undecyl demonstrate significant anti-inflammatory potential. These findings suggest their promise for developing anti-inflammatory drugs, though further in vitro and in vivo studies are required to confirm their therapeutic viability.

Keywords: Anti-inflammatory, COX-2, Irak-4, PLA2, NF-kB, Molecular docking, Dynamics

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i3.53436 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Inflammation is an essential defence mechanism of the human body, but inflammation that invades the body, apart from defending that affects healthy body parts, can cause various chronic diseases [1]. Uncontrolled inflammation can lead to severe illnesses like cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, cancer, and autoimmune disorders [2]. Understanding the mechanisms and mediators of inflammation is crucial for developing effective therapeutic strategies.

Conventional anti-inflammatory drugs, such as NSAIDs and corticosteroids, have proven effective but are often accompanied by significant side effects, including gastrointestinal irritation, cardiovascular risks, and renal complications [3]. These limitations underscore the need for safer and more effective therapeutic alternatives. Herbal medicines are gaining importance for many diseases due to their efficacy and low reports of side effects. Hence, commonly available herbs like Zingiber officinale or ginger, known for their medicinal properties, especially rhizome, are used for anti-cancer, cardioprotective, antidiabetic, wound healing, and antifungal properties [4]. The versatility of Zingiber officinale in addressing various health issues and ease of availability make it a distinct and beneficial therapeutic agent in traditional and modern medicine. The bioactive molecules such as gingerols, volatile oils, and diarylheptanoids give the rhizome amazing properties in treating numerous medical ailments, including cholera, nausea, stomach aches, and bleeding, mainly with dried ginger. Ginger leaves are edible, rich in antioxidants, and have antibacterial, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, anti-ulcer, and anticancer properties [5, 6] but can be further explored as potential and promising natural compounds for developing target inhibitors of COX-2, IRAK-4, PLA2, and NF-kB.

The inflammatory process is governed by a network of mediators, including arachidonic acid derivatives, phospholipid mediators, chemokines, and cytokines. Specific key mediators play a dual role in inflammation and healing. Phospholipases are mediators of intra and inter-cellular signaling. Phospholipase A2 (PLA2) part of membrane phospholipids and mediates inflammation [7]. Nuclear factor-κB inducing kinase (NF-kB/NIK) regulates pro-inflammatory genes in innate immune cells and is acentral mediator for various immune receptors. Chemokines, Interleukins, interferons, and tumor necrosis factor are types of cytokines that regulate inflammation. Interleukins (IL) have a pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory response [8, 9]. IL-4 and IL-10 are responsible for developing chronic inflammation, whereas IL-6 are pro-inflammatory cytokines [10-12]. The enzyme responsible for the pathological condition of inflammation, pain, and fever is the cyclooxygenase (COX) enzyme [13-15]. Anti-inflammatory drugs act by blocking the COX-2 enzyme [16, 17]. Bioinformatic tools for drug discovery enable the identification and screening of novel biomolecular targets [18]. This approach minimizes experimental costs and accelerates the drug development process. Researchers can predict binding mechanisms through CADD, calculate binding affinities, and suggest molecular modifications to enhance efficacy [19]. Employing computational methods, researchers can expedite the identification and development of plant-derived chemicals for managing various ailments, hence promoting the long-term investigation of natural medicine sources [20, 21]. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations further support drug exploration by providing awareness of aspects of proteins and ligands under physiological conditions [23, 24].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Methodology in silico platform

The in silico analysis was performed on Maestro version 13.5.128, MMshare Version 6.1.128, Release 2023-1, workstation machine runs with Linux –x86_64 as the operating system, of Intel core i7 (octa-core) processor, with 16 GB RAM, 1 TB Hard disk, and a 64-bit. The molecular dynamics were performed using DESMOND (Schrodinger Inc., USA) (https://www.schrodinger.com/products/desmond).

Ligand preparation

In a previous study conducted in our laboratory, the phytochemical constituents of Z. officinalis were identified using GC-MS analysis from both aqueous and methanolic extracts. These extracts demonstrated significant in vitro anti-inflammatory activity in comparison to the standard drug, diclofenac [6]. Based on this, 24 bioactive compounds were selected from both extracts for in silico studies to identify potential inhibitors of inflammation. Ligands were chosen based on GC-MS data, and their structures and SMILES codes were generated using ChemDraw software and the PubChem database. The 3D structures of these ligands were created and underwent energy minimization using the LigPrep module. Structural optimization was performed to achieve the global minimum configuration [25].

Predicted physiochemical and pharmacokinetic properties

A drug must exhibit favorable physicochemical and pharmacokinetic (PK) properties to prevent early failure during drug discovery. These properties were evaluated using the QikProp module. This process aligns with five rules put forth by Lipinski (RO5) regarding the drug-like compounds should follow specific criteria: a molecular weight less than 500 Da, not more than 5 H bond donors and not more than 10 H bond acceptors, and a partition coefficient (log P) not exceeding 5 [26].

Protein preparation

To predict the presumed binding mode of the active phytoconstituents with the target protein Cyclooxygenase-2, Phospholipase A2, NF-kB-inducing kinase, and interleukin-1-receptor-associated kinase-4, using the Schrodinger module and the docking scores, the docking investigation was conducted into the active site of the co-crystal structure PDB: 5IKT, 4UY1, 1A3Q, 5KX7. The proteins were prepared and pre-processed including optimizing bond orders, adding hydrogens, and forming disulfide bonds. Water molecules within a 5.0 Å radius of the active site were retained, while others were removed. At a pH of 7.0, the protonation states were adjusted through hydrogen bond network optimization. Protein-energy minimization was performed using the OPLS_2005 force field [27, 28].

Receptor grid generation

The Glide module created a receptor grid around the target protein's active site, as defined by a co-crystallized ligand. The grid, centred on the enzyme's active site, was used to dock ligands and assess their binding affinities and interactions [29].

Molecular docking

Ligands were docked into the active sites of the targets using the Glide Dock XP module. The docking process, performed with extra precision using the OPLS-2005 force field, generated conformations for each molecule along with their binding affinities [30, 31].

Binding free energy calculations

The MM-GBSA test helps to know the binding free energy of protein-ligand complexes. The binding free energy, the sum of all intermolecular interactions between the ligand and the target, was evaluated using the Prime module [32-34].

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations

The Desmond module was used to run molecular dynamics (MD) simulations on the best-docked complex from each target. To evaluate complex stability, compatibility, and fluctuations, a 100 ns simulation was run [35]. The TIP3P water model and the OPLS_2005 force field were used. An orthorhombic box containing a 10 Å buffer neutralized with Na+/Cl-ions was used for the simulations. In the NPT ensemble, the system was kept at 300 K and 1 atm of pressure. During the simulation, MD trajectories were tracked and recorded [36, 37].

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

In silico predictions

The prepared ligands were anchored into the active site of the receptors. The pharmacokinetic (PK) properties were used to analyse the oral effectiveness of the compound. Through examination of the drug-like characteristics, the best PK characteristics may be chosen, and compliance-based predictions were made using Lipinski's five rules. Parameters like molecular weight, number of hydrogen bond donors and acceptors, and partition coefficient (log P value) were considered for the rule of five, and Qikprop was used to predict the ADME properties of phytoconstituents.

Table 1: Physicochemical properties of phytoconstituents of aqueous and methanolic extract of Z. Officinalis leaves

| Phytoconstituent | Molecular weight | Donor HB | Acceptor HB | QP logPo/w | Rule of five | Rule of three |

| Acceptable range | <500 | <5 | <10 | -2 to 5.0 | <4 | <3 |

| Pterin-6-carboxylic acid* | 207.148 | 4.000 | 8.000 | -1.594 | 0 | 1 |

| 14-pentyl bicyclohexyl-4carbonamide** | 250.467 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 8.890 | 1 | 1 |

| Beta sitosterol** | 414.713 | 1.000 | 1.700 | 7.453 | 1 | 1 |

| Cholesta-8,24-diene-3ol4-methyl-(3-beta,4-alpha)** | 398.671 | 1.000 | 1.700 | 7.130 | 1 | 2 |

| Cyclopropane Pentanoicacid2-undecyl* | 310.519 | 0.000 | 2.000 | 6.105 | 1 | 0 |

| 1-hexyl-2-nitrocyclohexane | 213.319 | 0.000 | 2.000 | 3.320 | 0 | 0 |

| 15-methylhexadecanoicacid** | 270.454 | 1.000 | 2.000 | 5.570 | 1 | 1 |

| Pentyn-3-ol,3-methylcarbamate | 141.169 | 2.500 | 2.500 | 0.787 | 0 | 0 |

| 2-undecanone6 10 dimethyl | 198.348 | 0.000 | 2.000 | 3.843 | 0 | 0 |

| 12-methyl e, e-2,13-octadecadi-1-ol** | 280.493 | 1.000 | 1.700 | 6.172 | 1 | 1 |

| Carbamimidothioic acid,1methylethyl | 118.196 | 3.000 | 1.500 | 0.479 | 0 | 0 |

| Oxirane** | 284.481 | 1.000 | 2.000 | 5.964 | 1 | 1 |

| Caryophyllene** | 204.355 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 5.708 | 1 | 1 |

| Eicasanoicacid** | 326.562 | 0.000 | 2.000 | 7.333 | 1 | 1 |

| Hexadecanoic acid 15-methyl methyl** | 284.481 | 0.000 | 2.000 | 6.070 | 1 | 1 |

| Sarsasapogenin** | 416.643 | 1.000 | 3.200 | 5.891 | 1 | 1 |

| 13,16-octadecadicynoic** | 290.445 | 0.000 | 2.000 | 6.239 | 1 | 1 |

| Z,z,z,1,4,6,9nonadecatetraene** | 260.462 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 9.921 | 1 | 1 |

| 17-octadecanoic acid, methyl ester** | 294.476 | 0.500 | 2.000 | 6.268 | 1 | 1 |

| 1-octadecyne** | 250.467 | 0.500 | 0.000 | 9.292 | 1 | 1 |

| 1-hexadecyne** | 222.413 | 0.500 | 0.000 | 8.258 | 1 | 1 |

| Pentadecanoic methyl ester** | 270.454 | 0.000 | 2.000 | 5.709 | 1 | 1 |

| Beta carotene** | 536.882 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 17.053 | 2 | 2 |

| Heptacosanoicacidmethylester** | 424.749 | 0.000 | 2.000 | 10.044 | 1 | 1 |

| Diclofenac | 296.152 | 2.000 | 2.500 | 4.467 | 0 | 0 |

*,**-indicates compounds which have violated one rule or two rules respectively.

The results from table 1 show metabolites 1-hexyl-2-nitrocyclohexane, Pentyn-3-ol,3-methylcarbamate, 2-undergone 6,10 dimethyl, and Carbamimidothioic acid,1methylethyl have obeyed the Lipinski RO5 and Jorgensen RO3 without any violation. Pterin-6-carboxylic acid and cyclopropane Pentanoicacid2-undecyl have violated one rule, and the remaining constituents have violated two rules within the permissible limits.

Table 2: ADMET properties of phytoconstituents of aqueous and methanolic extract of Z. officinalis leaves

| Phytoconstituent | % Human oral absorption | CNS | QP log BBB | QPPCaco | QPPMDCK | QPlogkhsa | #Metab | QPlog HERG |

| Acceptable Range | >80%-excellent <25%-poor |

-2 to+2 | -3.10 to 1.2 | >500-good <25-poor |

>500-good <25-poor |

-1.5 to 1.5 | <8 | Below -5 |

| Pterin-6-carboxylic acid | 25.130 | -2 | -2.147 | 2.630 | 1.023 | -0.948 | 1 | -1.687 |

| 14-pentyl bicyclohexyl-4carbonamide | 100.000 | 2 | 1.379 | 9906.038 | 5899.293 | 1.467 | 7 | -4.167 |

| Beta sitosterol | 100.000 | 0 | -0.339 | 3404.604 | 1859.735 | 2.002 | 3 | -4.522 |

| Cholesta-8,24-diene-3ol4-methyl-(3-beta,4-alpha) | 100.000 | 0 | -0.145 | 3954.229 | 2186.267 | 1.933 | 7 | -4.345 |

| Pentanoicacid2-undecyl | 100.000 | -1 | -0.794 | 3412.381 | 1864.327 | 1.060 | 1 | -4.009 |

| 1-hexyl-2-nitrocyclohexane | 100.000 | 0 | -0.570 | 1582.610 | 812.549 | 0.311 | 0 | -3.933 |

| 15-methylhexadecanoicacid | 90.004 | -2 | -1.406 | 266.166 | 150.468 | 0.657 | 1 | -3.284 |

| Pentyn-3ol,3-methylcarbamate | 83.659 | -1 | -0.556 | 815.248 | 396.702 | -0.518 | 1 | -3.328 |

| 2-undecanone6,10 dimethyl | 100.000 | 0 | -0.366 | 3530.081 | 1933.928 | 0.346 | 1 | -4.129 |

| 12-methyl e, e-2,13-octadecadi-1-ol | 100.000 | -1 | -0.924 | 3304.713 | 1800.827 | 1.098 | 4 | -5.574 |

| Carbamimidothioic acid,1methylethyl | 81.205 | -1 | -0.452 | 749.553 | 539.889 | -0.721 | 1 | -2.677 |

| Oxirane | 92.485 | -2 | -1.484 | 272.033 | 154.057 | 0.784 | 1 | -3.445 |

| Caryophyllene | 100.000 | 2 | 1.114 | 9906.038 | 5899.293 | 1.054 | 5 | -3.628 |

| Eicasanoic acid | 100.000 | -2 | -1.276 | 2685.357 | 1438.966 | 1.513 | 1 | -5.954 |

| Hexadecanoic acid 15-methyl methyl | 100.000 | -1 | -0.982 | 2635.438 | 1410.075 | 1.123 | 1 | -5.429 |

| Sarsasapogenin | 100.000 | 1 | -0.062 | 3414.013 | 1865.290 | 1.558 | 1 | -3.827 |

| 13,16-octadecadicynoic | 100.000 | -1 | -0.974 | 2892.406 | 1559.253 | 1.154 | 4 | -6.094 |

| Z,z,z,1,4,6,9nonadecatetraene | 100.000 | 2 | 1.456 | 9906.038 | 5899.293 | 1.615 | 3 | -6.024 |

| 17-octadecynoicacid, methyl ester | 100.000 | -2 | -1.065 | 2895.164 | 1560.861 | 1.100 | 2 | -5.834 |

| 1-octadecyne | 100.000 | 2 | 1.471 | 9906.038 | 5899.293 | 1.290 | 1 | -5.564 |

| 1-hexadecyne | 100.000 | 2 | 1.361 | 9906.038 | 5899.293 | 1.043 | 1 | -5.255 |

| Pentadecanoic methyl ester | 100.000 | -1 | -0.900 | 2673.647 | 1432.185 | 1.003 | 1 | -5.310 |

| Diclofenac | 100.000 | -1 | -0.284 | 296.036 | 518.295 | -0.009 | 4 | -2.812 |

The ADMET Properties of the phytoconstituents are displayed in table 2 and are predicted using Qikprop. % Human oral absorption of Pterin-6-carboxylic acid is poor could be that the carboxyl group has got ionized in the acidic pH of the stomach, which would have reduced the solubility or it would have been a substrate for P-glycoprotein that caused it to be transported into the lumen from intestinal cells, limiting its absorption into the bloodstream, whereas all the other compounds have good oral absorption. The human intestinal Caco–2 and MDCK cell permeability have been commonly used to estimate the drug permeability. Pterin-6-carboxylic acid confirmed poor oral absorption. All the selected compounds showed that the CNS permeability values were within the acceptable range and none displayed any violation. #Metab refers to several likely metabolic reactions; the recommended range is between 1 to 8. Pterin-6-carboxylic acid showed the least number of metabolic reactions, proving it to be a stable molecule. The human ether-a-go-go related gene (HERG) is inhibited, which results in QT syndrome and deadly ventricular arrhythmia. Every single chosen chemical exhibited a mild suppression of HERG. As a result, it was thought that all the chemicals were relatively safe. QPlogHERG refers to the predicted IC50 value for blockage of HERG K+channels below the-5 value. Compounds14-Pentyl bi-cyclohexyl-4 carbonamide and beta-sitosterol showed violations.

To predict the presumed binding mode of the active phytoconstituents with target proteins, the glide XP module was used, and the docking scores of the compounds with each target Cyclooxygenase-2 (PDB ID: 5IKT), phospholipase A2 (PDB ID: 4UY1), NF-κB-inducing kinase (PDB ID: 1A3Q) and interleukin-1-receptor-associated kinase-4 (PDB ID: 5KX7) are depicted in table 3.

Table 3: Docking scores of phytoconstituents with target proteins

| Name of the constituent | Docking score | |||

| 5IKT | 4UY1 | 1A3Q | 5KX7 | |

| Diclofenac | -10.176 | -7.104 | -3.057 | -9.0544 |

| Pterin-6-carboxylic acid | -5.604 | -5.915 | -4.127 | -5.774 |

| 14-pentyl bicyclohexyl-4-carbonamide | -7.759 | -5.771 | -1.841 | -4.289 |

| Cholesta-8,24-diene-3ol 4-methyl-(3-beta, 4-alpha) | - | -4.480 | -2.984 | - |

| Cyclopropane Pentanoic acid 2-undecyl | -8.586 | -4.399 | -1.080 | -7.279 |

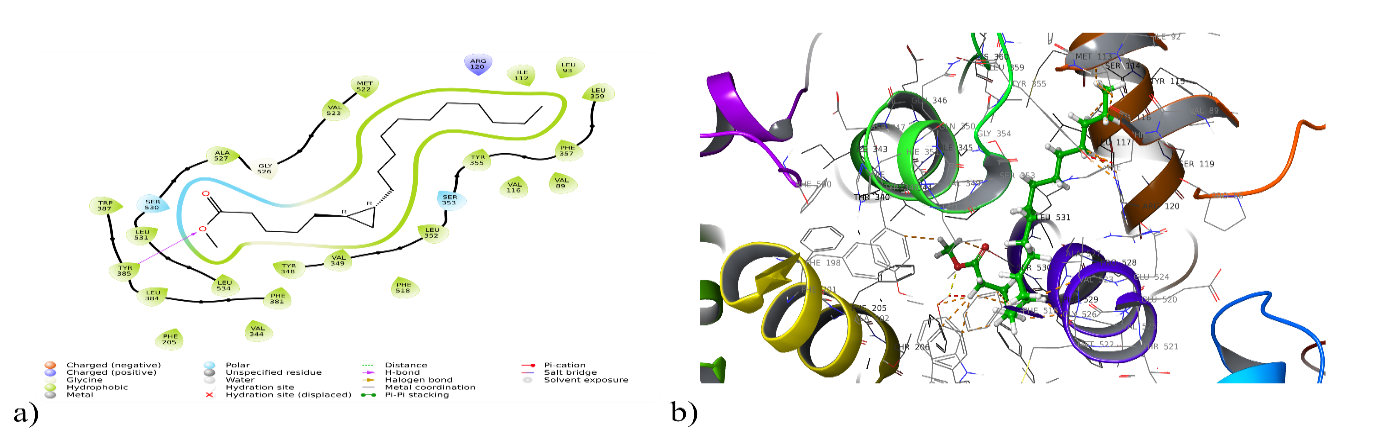

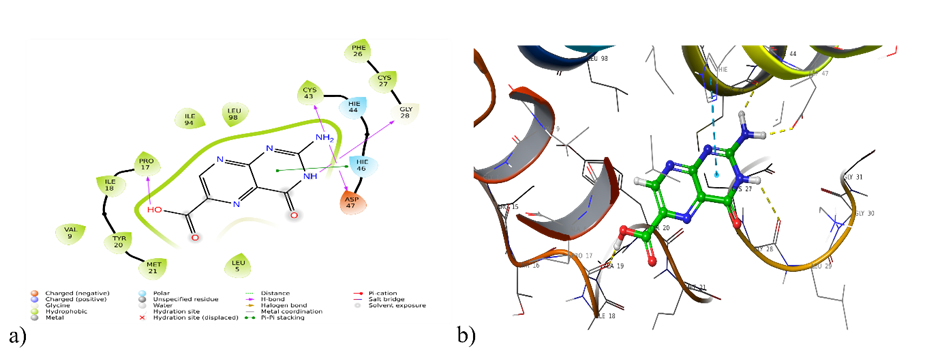

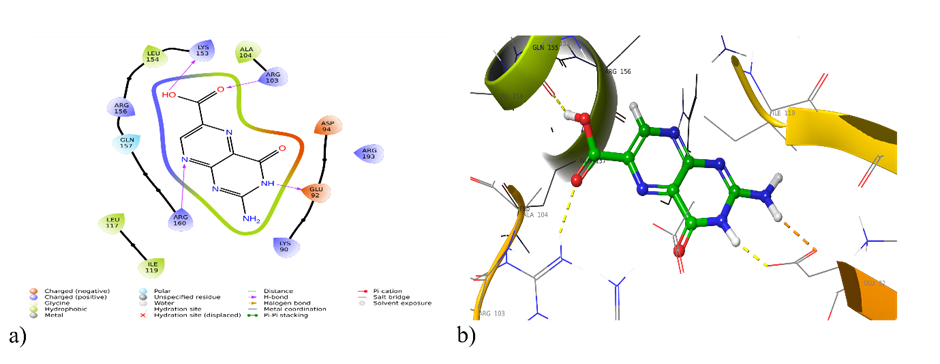

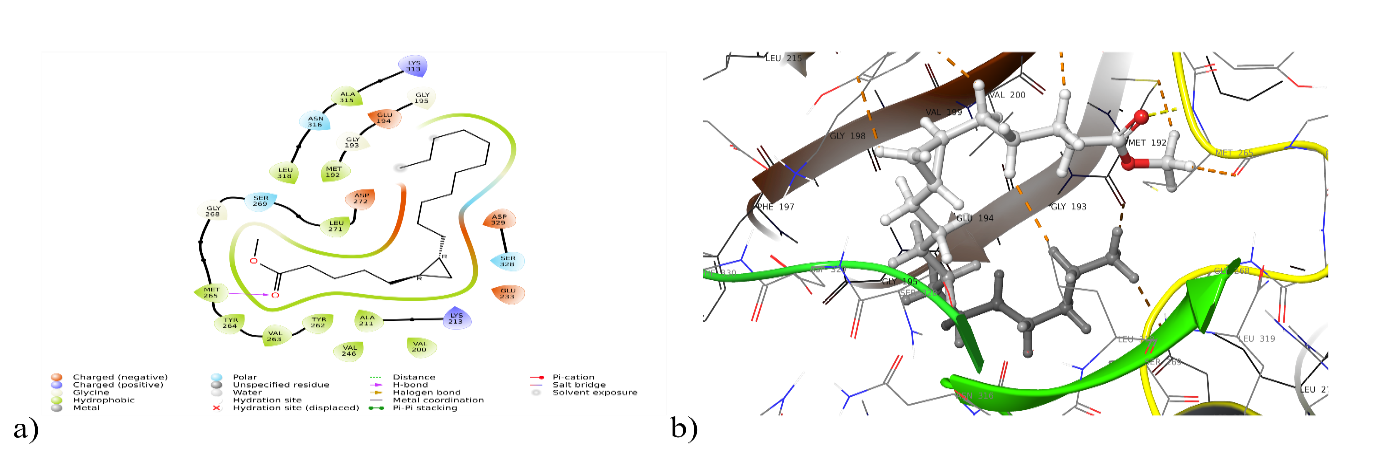

The prepared phytoconstituents were docked into the active pocket of the receptors and the compounds with the best docking scores are shown in table 3. From the docking results, it is observed that the best-docked score of ligands interacting with 5IKT was Cyclopropane Pentanoic acid 2-undecyl and 14-pentyl bi-cyclohexyl-4-carbonamide with a score of-8.586 and-7.759, respectively. Interaction with receptor 4UY1 was highest with Pterin-6-carboxylic acid and 14-pentyl bicyclohexyl-4-carbonamide-5.915 and -5.771, respectively, compared with standard Diclofenac. Interaction with target 1A3Q, the chemical constituent Pterin-6-carboxylic acid (-4.127) showed a better dock score than the standard (-3.057). Cholesta-8,24-diene-3ol 4-methyl-(3-beta, 4-alpha) also showed a good score of-2.984. Cyclopropane Pentanoic acid 2-undecyl and Pterin-6-carboxylic acid show scores of -7.279 and -5.774, respectively, possibly due to stronger interactions with a target of 5KX7. Most compounds showed a binding affinity with the four targets selected. The best was seen with Cyclopropane Pentanoic acid 2-undecyl and Pterin-6-carboxylic acid, and among the two, Pterin-6-carboxylic acid showed better with 4UY1 and with 1A3Q showed a better score than the standard hence it was selected for molecular dynamic simulation. The interactions of the top four molecules are shown in table 4 below, and interactions are shown in fig. 1-4.

Pterin-6-carboxylic acid contains a pteridine core, a bicyclic structure consisting of fused pyrazine and pyrimidine rings. The carboxyl functional group in Pterin-6-carboxylic acid contributes to hydrogen bonding and potential enzyme interactions [38, 39]. Additionally, its electron-rich aromatic system may enhance binding affinity to biological targets. When comparing the top dock-scored compounds, Pterin-6-carboxylic acid exhibited multiple hydrogen bonds with all the targets, a characteristic that enhances binding specificity (table 4).

The pteridine core is a well-established structural motif known for its anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties [40-42]. Given its presence in Pterin-6-carboxylic acid, the compound may exhibit similar biological effects, warranting further investigation into its potential therapeutic applications. However, the pteridine core of Pterin-6-carboxylic acid is also responsible for its extensive hydrogen bonding, which often results in poor membrane permeability. This limitation can be addressed through various structural modification techniques, such as esterification or a prodrug approach. A study conducted by Zhejiang et al. reported that structural modification of 6-hydroxykynurenic acid via esterification resulted in improved bioavailability and permeability [43]. Similarly, esterification of the terminal carboxyl (-COOH) group in Pterin-6-carboxylic acid to its methyl or ethyl esters may enhance membrane permeability. Additionally, NSAIDs have been modified through esterification with alkyl or aryl groups to generate prodrugs, a strategy that has been shown to effectively reduce gastrointestinal irritation. This was further supported by a study on oxaprozin, where the esterified prodrug of oxaprozin retained its therapeutic efficacy while demonstrating an improved pharmacokinetic profile and reduced gastrointestinal side effects [44].

Considering the structural features of Pterin-6-carboxylic acid, it contains a pteridine core consisting of fused pyrazine and pyrimidine rings, which form an electron-rich aromatic system that may engage in strong π-π interactions with aromatic residues in the binding site, thereby enhancing binding affinity [45]. In contrast, Cyclopropane Pentanoic acid 2-undecyl contains a long undecyl alkyl chain, which enhances hydrophobic interactions with the hydrophobic pockets of the target protein [46]. These interactions increase binding stability by allowing the compound to bind more tightly to the non-polar regions of the binding site. The interactions formed by the compounds are detailed in (table 2).

Additionally, the carboxyl group (-COOH) present in both structures provides an additional hydrogen bonding site with the target, further stabilizing the interaction. It may also participate in electrostatic interactions with positively charged residues [47]. These factors contribute to the compound's ability to form superior interactions with the active site, thereby improving both specificity and affinity.

Fig. 1: a) 2D and b) 3DInteraction of cyclopropane pentanoic acid 2-n decyl with 5IKT

Fig. 2: a) 2D and b) 3D interaction of pterin-6-carboxylic acid with4UY1

Fig. 3: a) 2D and b) 3D interaction of pterin-6-carboxylic acid with 1A3Q

Table 4: Interactions of top four phytoconstituents with 5IKT, 4UY1, 1A3Q and5KX7

| Compounds | PDB ID | Interactions |

| Cyclopropane Pentanoic acid 2-ndecyl | 5IKT | Hydrogen Bonding: Tyr 385 Polar Interaction: Ser 530, Ser 353 Hydrophobic interaction: Trp 387, Tyr 385, Leu 384, Phe 381, Phe 205, Val 344, Leu 531, Leu 534, Ala 527, Val 523, Met 522, Tyr 348, Val 349, Phe 518, Leu 352, Tyr 355, Val 116, Val 89, Phe 157, Leu 150, Leu 91, Ile 112 |

| 4UY1 | Polar Interaction: Hie 46 Hydrophobic interaction: Ile 2,Leu 5, Ala 6,Val 9,Pro 17,Ile 18,Tyr 20,Met 21,Phe 26,Cys 27,Leu 29,Cys 43, Tyr 50, Ile 94,Leu 98 |

|

| 1A3Q | Hydrogen Bonding: Arg 103 Polar interaction: Gln 157, Ser 196, Ser 206 Hydrophobic interaction: Leu 117,Ile 119,Ala 104, Phe 197 |

|

| 5KX7 | Hydrogen Bonding: Met265 Polar Interaction: Ser 328, Asn 316, Ser 269 Hydrophobic interaction: Met 192, Val 200, Ala 211, Val 246, Tyr 262, Val 263, Tyr 264, Met265, Leu 271, Leu 271, Ala 315, Leu 318 |

|

| 14-pentyl bicyclohexyl-4carbonamide | 5IKT | Polar interaction: Ser 530, Ser 353 Hydrophobic interaction: Phe 518, Trp 387, Tyr 385, Leu 384, Phe 381, Met 522, Val 523, Ala 527, Leu 531, Ile 345, Leu 359, Met 113, Val 116, Leu 117, Tyr 355, Leu 352, Val 349 |

| 4UY1 | Polar interaction: Hie 46 Hydrophobic interaction: Ile 2, Leu 5,Ala 6, Val 9, Pro 17,Ile 18, Tyr 20,Met 21, Phe 26, Cys27, Cys 43, Tyr 50, Ile 94, Leu 98 |

|

| 1A3Q | Polar interaction: Gln 157, Ser 195 Hydrophobic interaction: Leu 117, Ile 119, Ala 104,Phe 197, Pro 208, Pro 211 |

|

| 5KX7 | Polar interaction: Asn 316, Ser 328 Hydrophobic interaction: Val 200, Ala 211,Tyr 262,Val 263, Tyr 264, Met 265, Val 246,Leu 318, Ala 315 |

|

| Pterin-6-carboxylic acid | 5IKT | Hydrogen Bonding: Ser 530,Tyr 385,Tyr 355 Polar interaction: Ser 530, Ser 353 Hydrophobic interaction: Ala 527, Leu 531, Leu 534, Tyr 385, Trp 387, Tyr 348, Val 349, Phe 518, Val 523, Leu 352, Tyr 355, Val 116 |

| 4UY1 | Hydrogen Bonding: Pro 17, Gly 28, Asp 47, Cys 43 Polar interaction: Hie 44,Hie 46 Hydrophobic interaction: Leu 5, Val 9, Pro 17, Ile 18, Tyr 20,Met 21, Cys 27,Phe 26,Cys 43,Leu 98,Ile 94 Pi-Pi-stacking: Hie 46 |

|

| 1A3Q | Hydrogen Bonding: Lys 153, Arg 103, Glu 92, Arg 60 Polar interaction: Gln 157 Hydrophobic interaction: Leu 154, Ala 104, Leu 117, Ile 119 |

|

| 5KX7 | Hydrogen Bonding: Met265, Asp272 Polar interaction: Ser 269 Hydrophobic interaction: Met 192, Val 200, Ala 211, Tyr 264, Met 265, Pro 266,Leu 271, Leu 318, Ala 315 |

|

| Cholesta-8,24-diene-3ol4-methyl-(3-beta,4-alpha) | 5IKT | - |

| 4UY1 | Hydrogen Bonding: Met 21 Polar interaction: Hie 46 Hydrophobic interaction: Leu 98, Ile 94, Cys 43, Val 9, Ala 6,Leu 5, Ile 2,Tyr 50, Cys27, Leu 29, Met 21, Tyr 20, Phe 26 |

|

| 1A3Q | Hydrogen Bonding: Ser 161 Polar interaction: Gln 157, Ser 161 Hydrophobic interaction: Ile 119,Leu 117,Phe 197, Pro 208, Ala 104 |

|

| 5KX7 | - | |

| Diclofenac | 5IKT | Polar interaction: Ser 353, Ser 530 Hydrophobic interaction: Val 116, Tyr 355, Leu 352, Val 349, Tyr 348, Leu 534, Leu 531, Ala 527, Val 523, Met 522, Phe 381, Leu 384, Tyr 385, Trp 387, Phe 518, Val 344, Phe 205 |

| 4UY1 | Hydrogen Bonding: Tyr 20, Asp 47 Polar interaction: Hie 46 Hydrophobic interaction: Leu 29, Cys 27, Cys 43, Leu 98, Ile 94, Val 9, Ala 6, Leu 5, Ile 2, Met 21, Tyr 20, Pro 17 |

|

| 1A3Q | Hydrogen Bonding: Glu 92 Polar interaction: Gln 57 Hydrophobic interaction: Ile 119, Leu 117, Ala 104 |

|

| 5KX7 | Hydrogen Bonding: Met 265 Polar interaction: Ser 269, Ser 328, Asn 316 Hydrophobic interaction: Ala 315, Leu 318, Val 246, Met 265, Tyr 264, Val 263, Tyr 262, Ala 211, Met 192, Val 200 |

Fig. 4: a) 2D and b) 3D interaction of cyclopropane pentanoic acid 2-n decyl with 5KX7

Inflammation is a complex process driven by several mediators like cytokines, chemokines, and prostaglandins. It would be advantageous to be able to identify a single molecule with multi-target activity, thereby producing synergistic action through multi-targeting to effectively reduce inflammation rather than target a single mediator or one pathway.

The MMGBSA method, which is molecular mechanics with generalized born and surface area solvation, is commonly used to determine the free energy associated with ligand binding to proteins. A lower free energy value indicates a stronger interaction and more excellent complex stability. The more negative the value, the more free energy is released during complex formation. MMGBSA is chosen for re-scoring due to its efficiency in calculating free energy binding compared to other computational methods [48].

MMGBSA analysis shows better binding energy calculation than molecular docking energies and depicts stronger binding of ligands to receptors. Including each energy component in the free energy calculation provides insight into the ligand binding mechanism. The electrostatic interaction, H bond, lipophilic, and van der Waal’s interaction are contributors to the overall binding free energy of the complex.

Molecular dynamics (MD) is an efficient bioinformatics simulation method to understand the dynamic behavior of proteins, from fast internal movement to slow structural changes based on different times, representing each atom in different molecular and protein systems in femtoseconds. Reveals the dynamic behavior of water molecules and solvation required for protein functioning and ligand binding. It also gives an idea of the stability and thermodynamic parameters of the biomolecular system. It arranges molecular perturbations that can be studied and compared from the results obtained from the simulations performed under various conditions.

Table 5: Binding free energy calculation of top four ligands with 5IKT, 4UY1, 1A3Q and5KX7 target proteins

| Ligands | Targets | dG Bind | dG Bind coulomb |

dG Bind covalent | dG Bind H bond | dG Bind lipo |

dG Bind solv GB | dG Bind vdW |

| Cyclopropane Pentanoic acid 2-ndecyl | 5IKT 4UY1 1A3Q 5KX7 |

-56.76 -87.32 -54.50 -86.40 |

-7.31 -2.14 -10.00 -8.82 |

27.32 1.91 2.82 2.63 |

-0.60 -0.45 -1.03 -0.25 |

-84.49 -60.24 -38.43 -57.52 |

9.19 14.89 24.44 21.92 |

1.13 -32.29 -32.29 -44.37 |

| 14-pentyl bicyclohexyl-4carbonamide | 5IKT 4UY1 1A3Q 5KX7 |

-24.14 -80.80 -45.56 -40.19 |

-0.27 0.55 0.72 0.46 |

18.54 8.08 2.04 10.61 |

0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 |

82.02 -73.08 -36.59 -54.94 |

14.58 14.09 17.26 19.89 |

25.03 -30.44 -28.06 -16.20 |

| Pterin-6-carboxylic acid | 5IKT 4UY1 1A3Q 5KX7 |

-38.97 -43.12 -28.95 -39.79 |

-9.75 -31.53 -39.71 -25.84 |

0.62 3.46 5.07 2.69 |

-0.67 -3.87 -6.24 -1.44 |

-8.51 -7.44 -4.51 -8.40 |

11.42 26.29 33.61 20.52 |

-31.86 -29.77 -17.16 -27.32 |

| Cholesta-8,24-diene-3ol4-methyl-(3-beta,4-alpha) | 5IKT 4UY1 1A3Q 5KX7 |

- -83.69 -53.11 - |

- -7.45 -12.09 - |

- 11.39 4.06 - |

- -0.26 -0.23 - |

- -78.57 -42.50 - |

- 20.95 19.29 - |

- 20.54 -21.64 - |

| Diclofenac | 5IKT 4UY1 1A3Q 5KX7 |

-59.56 -73.83 -42.33 -73.27 |

-15.20 -15.20 -20.17 -17.84 |

7.69 2.74 5.14 -0.00 |

-0.50 -1.23 -1.01 -0.50 |

-40.86 -38.86 -25.86 -41.20 |

20.24 17.41 25.89 20.59 |

-30.76 -38.69 -25.54 -34.14 |

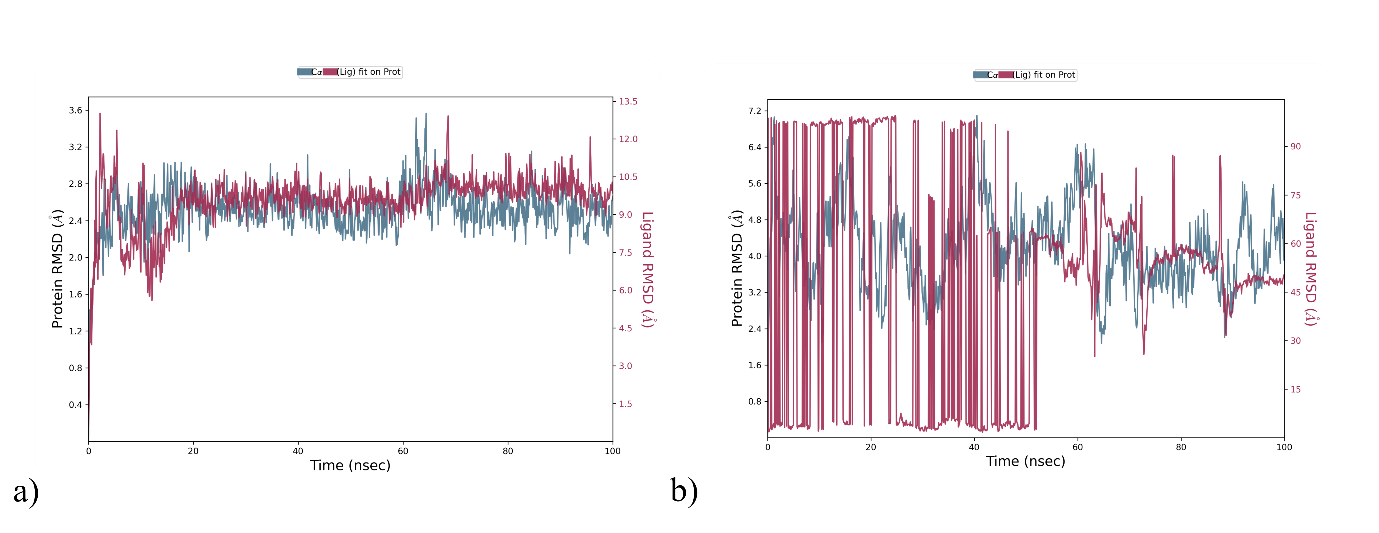

Fig. 5: RMSD analysis of a) Pterin 6 Carboxylic acid with 4UY1 b) Pterin 6 Carboxylic acid with 1A3Q

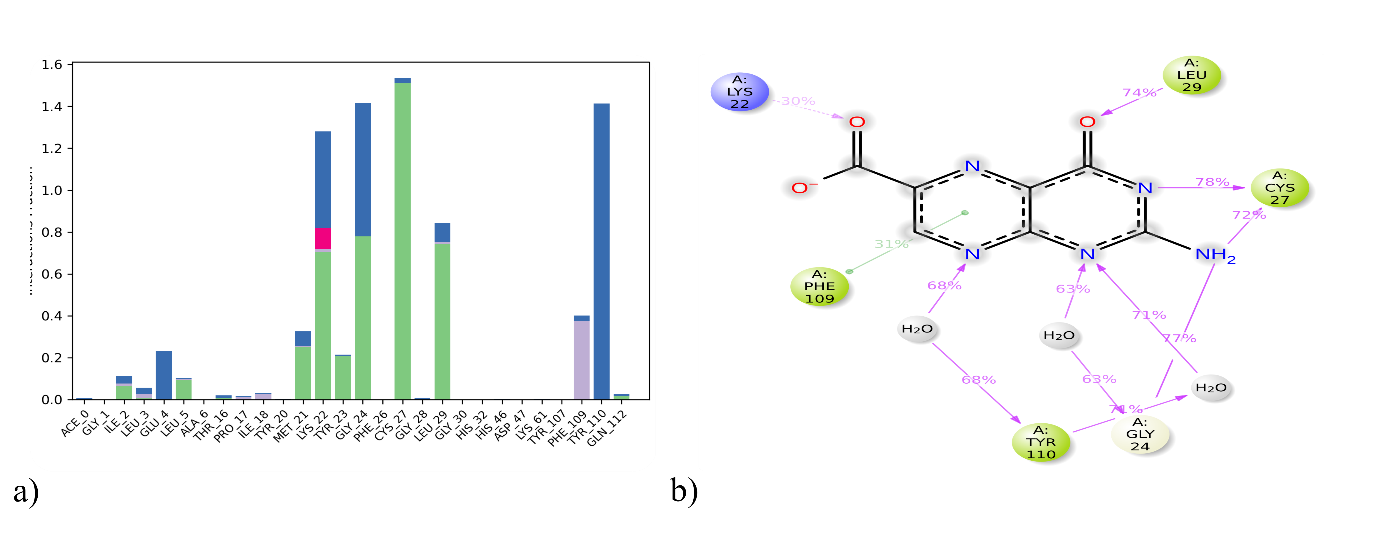

Fig. 6: Active site amino acid residue contacts of pterin 6 carboxylic acid with 4UY1 a) Protein-ligand contact analysis of MD trajectory, (b) 2D interaction diagram

The Pterin 6 Carboxylic acid exhibited excellent binding affinity with multiple targets (i. e, 4UY1 and 1A3Q). Hence for further validation, the complex was subjected to Desmond of Schrodinger for MD simulation. The complexes underwent 100 ns simulations to assess Root mean Square Deviation (RMSD), and Root mean Square Fluctuations (RMSF) were evaluated, thereby analysing the stability and flexibility of the ligands. Detailed discussions on the receptor-ligand complexes of 4UY1/Pterin 6 Carboxylic acid.

RMSD measures the structural deviations from its original form over time. Lower RMSD values imply the structure is more stable. The 4UY1/Pterin 6 Carboxylic acid complex displays dynamic behavior, suggesting stable configuration, with an average RMSD fluctuating between 1.6 and 3.6 Å. The ligand underwent limited conformational change, and the overall RMSD values remained within an acceptable range, suggesting a conformationally stable protein-ligand complex (fig. 5a). A detailed analysis determined the average interaction frequency of individual amino acids within the binding site for each simulated system and visualized it in histograms. In the 4UY1/Pterin 6 Carboxylic acid, Cys27 exhibited the highest occupancy, forming a hydrogen bond stabilized by water bridges (fig. 4a). Key hydrophobic interactions involved Ile2, Leu5, Thr16, Met 21, Lys22, Tyr 23, Gly24, Cys27 and Leu 29. Post-MD simulations preserved interactions involving amino acids Cys27 consistent with post-docking predictions (fig. 6b).

The 1A3Q/Pterin 6 Carboxylic acid complex exhibits notable fluctuations, indicating that the ligand actively explores different conformations within the binding site to reach a stable configuration (fig. 5b). The pronounced movement of the ligand suggests a potentially suboptimal binding mode or an unstable complex.

CONCLUSION

The docking studies revealed that Pterin 6-carboxylic acid exhibited potent binding affinity against various anti-inflammatory targets. Consequently, a molecular dynamics study was conducted to further validate the stability of this compound within a biological system. The findings demonstrated that the 4UY1/Pterin 6-carboxylic acid complex maintained stable binding interactions, whereas the 1A3Q/Pterin 6-carboxylic acid complex showed instability.

However, the compound's pharmacokinetic profile indicates poor oral absorption bioavailability, which may be due to low solubility, permeability, and instability in physiological conditions. This can be overcome by structural modifications such as esterifying the carboxyl group or by acylating the pterin molecule, by introducing a halogen like fluorine or electron withdrawing group (-NO2 or CF3), and also through suitable formulations such as encapsulating in lipid nanoparticles or converting into prodrugs probably could improve the lipophilicity of the molecule membrane permeability and metabolic stability. Thus, the structure of Pterin 6-carboxylic acid can be utilized as a lead, with modifications aimed at developing a promising plant-based scaffold for treating inflammation.

The integration of herbal medicines with computational tools presents a promising avenue for addressing the challenges of inflammation management. By leveraging the medicinal properties of plants like Z. officinale and employing advanced computational methodologies, researchers can expedite the discovery of safe, effective, and innovative anti-inflammatory therapies. This synergistic approach promotes the exploration of natural medicine sources and holds the potential for developing innovative anti-inflammatory therapeutics.

Though in silico simulations are helpful in hypothesis generation and provide valuable insights, experimental validation through in vitro and in vivo methods is essential for reliability and applicability in human systems.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors are grateful to NGSM Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Nitte (Deemed to be University), Mangaluru, for providing the necessary research facilities and JSS College of Pharmacy Mysore, JSS Academy of Higher Education and Research, Mysore.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Chaya, Chaya PL, Akshatha: Literature search, Performing in-silico studies and draft preparation. Jane Mathew: Conceptualization of idea supervision and draft editing. ZakiyaFathima: performed in-silico studies, interpreting data and draft editing, Durgesh: Performed molecular docking and molecular dynamics. The raw data was obtained from 2D and 3D interactions with allied data. Dixit: Checking scientific facts and correctness for molecular docking and dynamic studies to give concluding remarks.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

Yuan G, Wahlqvist ML, HE G, Yang M, LI D. Natural products and anti-inflammatory activity. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2006;15(2):143-52. PMID 16672197.

Herowati R, Widodo GP. Molecular docking analysis: interaction studies of natural compounds to anti-inflammatory targets. In: Kandemirli F, editor. Quantitative structural activity relationship. In Tech; 2017. doi: 10.5772/intechopen.68666.

Varrassi G, Coluzzi F, Fornasari D, Fusco F, Gianni W, Guardamagna VA. New perspectives on the adverse effects of nsaids in cancer pain: an italian delphi study from the rational use of analgesics (RUA) group. J Clin Med. 2022;11(24):7451. doi: 10.3390/jcm11247451, PMID 36556066.

Murakami M, Kudo I. Phospholipase A2. J Biochem. 2002;131(3):285-92. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a003101, PMID 11872155.

Hawkey CJ. COX-2 inhibitors. Lancet. 1999;353(9149):307-14. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)12154-2, PMID 9929039.

Ambily PG, Mathew J, Sudhina M. Analysis of leaf extract of Zingiber officinale by a hybrid analytical technique. Curr Trends Biotechnol Pharm. 2022;16(3):316-28.

Kalgutkar AS, Crews BC, Rowlinson SW, Marnett AB, Kozak KR, Remmel RP. Biochemically based design of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors: facile conversion of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to potent and highly selective COX-2 inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(2):925-30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.925, PMID 10639181.

Umar S, Palasiewicz K, Van Raemdonck K, Volin MV, Romay B, Amin MA. IRAK4 inhibition: a promising strategy for treating RA joint inflammation and bone erosion. Cell Mol Immunol. 2021;18(9):2199-210. doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-0433-8, PMID 32415262.

Otto G. IRAK4 inhibitor attenuates inflammation. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2021;17(11):646. doi: 10.1038/s41584-021-00699-8, PMID 34584262.

Danto SI, Shojaee N, Singh RS, LI C, Gilbert SA, Manukyan Z. Safety tolerability pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of PF-06650833 a selective interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 4 (IRAK4) inhibitor in single and multiple ascending dose randomized phase 1 studies in healthy subjects. Arthritis Res Ther. 2019;21(1):269. doi: 10.1186/s13075-019-2008-6, PMID 31805989.

Stylianou E, Saklatvala J. Interleukin-1. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1998;30(10):1075-9. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(98)00081-8, PMID 9785472.

Varrassi G, Coluzzi F, Fornasari D, Fusco F, Gianni W, Guardamagna VA. New perspectives on the adverse effects of NSAIDs in cancer pain: an Italian Delphi study from the rational use of analgesics (RUA) group. J Clin Med. 2022;11(24):7451. doi: 10.3390/jcm11247451, PMID 36556066.

Zarghi A, Arfaei S. Selective COX-2 inhibitors: a review of their structure-activity relationships. Iran J Pharm Res. 2011;10(4):655-83. PMID 24250402, PMCID PMC3813081.

Nageswara Rao R, Meena S, Raghuram Rao A. An overview of the recent developments in analytical methodologies for determination of COX-2 inhibitors in bulk drugs, pharmaceuticals and biological matrices. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2005;39(3-4):349-63. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2005.03.040, PMID 16009523.

Bennett J, Starczynowski DT. IRAK1 and IRAK4 as emerging therapeutic targets in hematologic malignancies. Curr Opin Hematol. 2022;29(1):8-19. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0000000000000693, PMID 34743084, PMCID PMC8654269.

Garcia Manero G, Platzbecker U, Lim KH, Nowakowski G, Abdel Wahab O, Kantarjian H. Research and clinical updates on IRAK4 and its roles in inflammation and malignancy: themes and highlights from the 1st symposium on IRAK4 in cancer. Front Hematol. 2024;3. doi: 10.3389/frhem.2024.1339870.

Bai YR, Yang WG, Hou XH, Shen DD, Zhang SN, LI Y. The recent advance of interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 4 inhibitors for the treatment of inflammation and related diseases. Eur J Med Chem. 2023;258:115606. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2023.115606, PMID 37402343.

Surabhi S, Singh BK. Computer-aided drug design: an overview. J Drug Delivery Ther. 2018;8(5):504-9. doi: 10.22270/jddt.v8i5.1894.

YU W, MacKerell AD. Computer-aided drug design methods. Antibiotics. Methods Protoc. 2017:85-106.

Nascimento IJ, DE Aquino TM, DA Silva Junior EF. The new era of drug discovery: the power of computer-aided drug design (CADD). Lett Drug Des Discov. 2022;19(11):951-5. doi: 10.2174/1570180819666220405225817.

Bharatam PV. Computer-aided drug design. In: Poduri R, editor. Drug discovery and development. Singapore: Springer Singapore. 2021. p. 137-210. doi: 10.1007/978-981-15-5534-3_6.

B Mathew JB, Fathima Z, Raviraj C, Mathew A. Quantitative estimation of mangiferin and molecular docking simulation of Salacia reticulata formulation. Res J Pharm Technol. 2024;17(2):578-84. doi: 10.52711/0974-360X.2024.00090.

Fathima CZ, James JP, Srinivasa MG, TJS, MJ, Revanasiddappa BC, Ghate DS. Investigating multitarget potential of Mucuna pruriens against parkinsons disease: insights from molecular docking MMGBSA pharmacophore modeling MD simulations and ADMET analysis. Int J Appl Pharm. 2024;16(5):176-93.

Srinivasa MG, Kumar DU, Mehta CH, Nayak UY, Revanasiddappa BC. In silico studies of (Z)-3-(2-chloro-4-nitrophenyl)-5-(4-nitrobenzylidene)-2-Thioxothiazolidin-4-One derivatives as PPAR-γ agonist: design molecular docking MM-GBSA assay toxicity predictions DFT calculations and MD simulation studies. J Comput. Biophys Chem. 2024;23(1):117-36.

Zakiya Fathima C, James JP, Dwivedi PS, Sindhu TJ. Molecular docking pharmacophore modeling 3d qsar molecular dynamics simulation and mmpbsa studies on hydrazine linked thiazole analogues as mao-b inhibitors. J Comput Biophys Chem. 2024:1-24. doi: 10.1142/S2737416524500790.

Thomsen R, Christensen MH. Mol dock: a new technique for high accuracy molecular docking. J Med Chem. 2006;49(11):3315-21. doi: 10.1021/jm051197e, PMID 16722650.

Meng XY, Zhang HX, Mezei M, Cui M. Molecular docking: a powerful approach for structure-based drug discovery. Curr Comput Aided Drug Des. 2011;7(2):146-57. doi: 10.2174/157340911795677602, PMID 21534921.

Sengupta S, Bhowmik R, Acharjee S, Sen S. In silico modeling of 1-3-[3-(substituted phenyl) prop-2-enoyl phenyl thiourea against anti-inflammatory drug targets. Biosci Biotechnol Res Asia. 2021;18(2):413.

Abdelshafeek KA, Osman AF, Mouneir SM, Elhenawy AA, Abdallah WE. Phytochemical profile comparative evaluation of Satureja montana alcoholic extract for antioxidants anti-inflammatory and molecular docking studies. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2023;23(1):108. doi: 10.1186/s12906-023-03913-0, PMID 37024878.

Sengupta S, Bhowmik R, Acharjee S, Sen S. In-silico-modelling-of-1-3-3-substituted-phenyl-prop-2-enoyl-phenyl-thiourea-against-anti-inflammatory-drug-targets/. Biosci Biotechnol Res Asia. 2021;18(2):413-21. doi: 10.13005/bbra/2928.

Abdelshafeek KA, Osman AF, Mouneir SM, Elhenawy AA, Abdallah WE. Phytochemical profile comparative evaluation of Satureja montana alcoholic extract for antioxidants anti-inflammatory and molecular docking studies. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2023;23(1):108. doi: 10.1186/s12906-023-03913-0, PMID 37024878.

El-Saghier AM, Enaili SS, Abdou A, Hamed AM, Kadry AM. Synthesis docking and biological evaluation of purine-5-N-isosteresas anti-inflammatory agents. RSC Adv. 2024;14(25):17785-800. doi: 10.1039/d4ra02970d, PMID 38832248.

Varghese SS, Mathews SM. A simulation approach for novel 1,3,4 thiadiazole acetamide moieties as potent antimycobacterial agents. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2024;16(7):40-7. doi: 10.22159/ijpps.2024v16i7.51356.

Poleboyina PK, Pawar SC. Comparative analysis of small molecules and natural plant compounds as therapeutic inhibitors targeting RDRP and nucleocapsid proteins of SARS COV 2: an in silico approach. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2023;16(10):208-28. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2023.v16i10.48095.

Achdeo R, Khanwelkar C, Shete A. In silico exploration of berberine as a potential wound healing agent via network pharmacology molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation. Int J Appl Pharm. 2024;16(2):188-94.

James JP, Devaraji V, Sasidharan P, Pavan TS. Pharmacophore modeling 3D QSAR molecular dynamics studies and virtual screening on pyrazolopyrimidines as anti-breast cancer agents. Polycyclic Aromat Compd. 2023 Sep 14;43(8):7456-73. doi: 10.1080/10406638.2022.2135545.

Srinivasa MG, Shivakumar DU, Kumar DU, Mehta CH, Nayak UY, Revanasiddappa BC. In silico studies of (z)-3-(2-chloro-4-nitrophenyl)-5-(4-nitrobenzylidene)-2-thioxothiazolidin-4-one derivatives as ppar-γ agonist: design molecular docking mm-gbsa assay toxicity predictions dft calculations and md simulation studies. J Comput Biophys Chem. 2024;23(1):117-36. doi: 10.1142/S2737416523500540.

Carmona Martinez V, Ruiz Alcaraz AJ, Vera M, Guirado A, Martinez Esparza M, Garcia Penarrubia P. Therapeutic potential of pteridine derivatives: a comprehensive review. Med Res Rev. 2019 Mar;39(2):461-516. doi: 10.1002/med.21529, PMID 30341778.

Pontiki E, Hadjipavlou Litina D, Patsilinakos A, Tran TM, Marson CM. Pteridine‐2,4‐diamine derivatives as radical scavengers and inhibitors of lipoxygenase that can possess anti‐inflammatory properties. Future Med Chem. 2015;7(14):1937-51. doi: 10.4155/fmc.15.104, PMID 26423719.

DE Jonghe S, Marchand A, Gao LJ, Calleja A, Cuveliers E, Sienaert I. Synthesis and in vitro evaluation of 2‐amino‐4‐N‐piperazinyl‐6‐(3,4‐dimethoxyphenyl)‐pteridines as dual immunosuppressive and anti‐inflammatory agents. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21(1):145-9. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.11.053, PMID 21131199.

Shen C, Dillissen E, Kasran A, Lin Y, Herman J, Sienaert I. Immunosuppressive activity of a new pteridine derivative (4AZA1378) alleviates severity of TNBS‐induced colitis in mice. Clin Immunol. 2007;122(1):53-61. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.09.007, PMID 17070110.

Shen C, Dillissen E, Kasran A, Lin Y, Clydesdale G, Sienaert I. Anti‐inflammatory activity of a pteridine derivative (4AZA2096) alleviates TNBS‐induced colitis in mice. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2006;26(8):575-82. doi: 10.1089/jir.2006.26.575, PMID 16881868.

Shen Z, HU H, Pan J, XU M, OU F, HE K. Pharmacokinetics and brain distribution studies of 6-hydroxykynurenic acid and its structural modified compounds. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2022 Jan;74(1):22-31. doi: 10.1093/jpp/rgab132, PMID 34586411.

Peesa JP, Atmakuri LR, Yalavarthi PR, Mandava Venkata BR, Rasheed A, Pachava V. Oxaprozin prodrug as safer nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drug: synthesis and pharmacological evaluation. Arch Pharmazie. 2018 Feb;351(2):1700256. doi: 10.1002/ardp.201700256, PMID 29283449.

Denburg D. Quantum mechanics-based computational chemistry has become a powerful partner in the scientific research of nitrogen-rich compounds, paving the way for important advances in biochemical, pharmacological and other related fields; 2021.

Gao Y, Duan L, Guan S, Gao G, Cheng Y, Ren X. The effect of hydrophobic alkyl chain length on the mechanical properties of latex particle hydrogels. RSC Adv. 2017;7(71):44673-9. doi: 10.1039/C7RA07983D.

Sun Z, Chai L, Shu Y, LI Q, Liu M, Qiu D. Chemical bond between chloride ions and surface carboxyl groups on activated carbon. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects. 2017;530:53-9. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2017.06.077.

Balaji B, Ramanathan M. Prediction of estrogen receptor β ligands potency and selectivity by docking and MM-GBSA scoring methods using three different scaffolds. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2012;27(6):832-44. doi: 10.3109/14756366.2011.618990, PMID 21999568.