Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 5, 2025, 352-360Original Article

SLOW-RELEASE DRUG DELIVERY SYSTEM FOR MESOPOROUS SILICA NANOPARTICLES LOADED WITH CELASTROL TO CONTROL ADENOCARCINOMA GASTRIC CELLS

MOHAMMAD TAGHI MORADI1, DHIYA ALTEMEMY2, LEILA HASHEMI1, POORIA MOHAMMADI ARVEJEH3, MAJID ASADI-SAMANI3, FARIBA HOUSHMAND1,4, PEGAH KHOSRAVIAN1*

1Medical Plants Research Center, Basic Health Sciences Institute, Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences, Shahrekord, Iran. 2Department of Pharmaceutics, College of Pharmacy, Al-Zahraa University for Women, Karbala, Iraq. 3Cellular and Molecular Research Center, Basic Health Sciences Institute, Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences, Shahrekord, Iran. 4Departments of Physiology and Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences, Shahrekord, Iran

*Corresponding author: Pegah Khosravian; *Email: pegah.khosraviyan@gmail.com

Received: 24 Dec 2024, Revised and Accepted: 11 Jun 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: The load of low-soluble drugs, such as celastrol (Celas) in mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs), increases the solubility and physicochemical stability of the drug. This study investigated the performance of MSNs loaded with Celas to counteract adenocarcinoma gastric (AGS) cells.

Methods: MSNs with amine surface modification (MSN-NH2) were prepared using the sol-gel method. MSN-NH2 were loaded with Celas and surface coated with Eudragit® RS 100 (Eud). The methods evaluated final prepared Celas@MSN-NH2/Eud as scanning electron microscope (SEM), Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDAX), thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA), Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET), Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and dynamic light scattering (DLS). Final nanoparticles were investigated for loading and release of Celas by spectrophotometric method. In vitro, the antiproliferative activity of free Celas and nanoparticles in AGS cell lines was evaluated using an MTT assay. The apoptosis rate of AGS cells was assessed according to the instructions of the FITC Annexin-V apoptosis detection kit and by flow cytometry.

Results: SEM results showed particles with an approximate size of 50 nm, and XRD results proved the crystal structure of MSNs. BET and Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) plots showed the surface area above 980 m2/g and the pore size of these particles at 2.8 nm, respectively. The FTIR results demonstrated the chemical structure of nanoparticles. The loading capacity of Celas@MSN-NH2/Eud with Celas was 2.6%, and the release of Celas from the nanoparticles increased under the influence of acidic pH. Anti-proliferative activity on AGS cells was increased in growth inhibitory effect by Celas@MSN-NH2/Eud than free Celas. The IC50 and confidence intervals (CI) 95% of the Celas was 0.3756 (CI 95%:0.3207-0.44 μM), higher than that of Celas@MSN-NH2/Eud, which was 0.1456 (CI95: 0.1277-0.1668 μM) against AGS cells. Examination of cellular apoptosis also showed heightened primary apoptosis in Celas-loaded nanoparticles compared to the same Celas concentration.

Conclusion: According to the obtained results, it can be said that Celas@MSN-NH2/Eud exhibited good anticancer activity against AGS cells. We conclude that using MSNs with Eud coating is suitable for Celas drug delivery to gastric cancer cells.

Keywords: Adenocarcinoma gastric cells, Celastrol, Mesoporous silica nanoparticles, Slow-release drug delivery system

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i5.53510 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer is one of the most common epithelial cancers today [1-3]. The incidence of Adenocarcinomas is about 95% of malignant gastric tumours, and the remaining 5% are lymphomas, stromal tumours, and other rare tumours [4]. Although the prevalence of gastric cancer has decreased with the improvement of lifestyles in recent decades, gastric cancer is still the second leading cause of cancer death worldwide [5]. Most patients diagnosed with gastric cancer are at an advanced stage of the disease at the time of diagnosis. Unfortunately, superficial and curable gastric cancers usually do not cause symptoms [6, 7].

Chemotherapy has significant benefits for patients after relapse surgery, such as increased survival, symptom control, and improved quality of life [4]. Recurrence of the disease is often seen after gastric cancer surgery. Chemotherapy is a good option to continue the treatment process, but due to various side effects, its use is limited and careful [8].

Apoptosis is a highly organized, programmed cell death process that plays a vital role in many of the normal functions, such as fetal growth to adult hemostasis [9]. Many apoptotic inducers are derived from medicinal plants [10], with numerous reports suggesting that such compounds may play a role in preventing or treating human cancers [11, 12]. These studies have shown that bioactive compounds lead to the apoptosis of cancer cells [13-15]. Recently, herbs have been considered with promising clinical results due to their positive effect in the treatment of cancer [16-18]. However, many herbal medicines' composition and mechanism of action remain unknown.

Celas is a triterpenoid isolated from Tripterygium wilfordii of the boxwood family. Celas is effectively used to treat autoimmune diseases, asthma, chronic inflammation, neurodegenerative diseases, and cancers [19, 20]. But one of the disadvantages of Celas is its very low solubility in water, which reduces its effectiveness. Most anticancer drugs are insoluble in water, and using nanoparticles to improve the drugs’ water solubility has attracted much attention [21]. MSNs are a suitable choice of nanoparticles to increase the solubility of hydrophobic drugs [22]. MSNs with high surface areas adsorb drugs in molecular or amorphous forms in their pores or surfaces, enhancing drug dissolution [23].

Conventional chemotherapy agents are distributed nonspecifically throughout the body to the extent that they affect both normal and cancer cells. In this way, the achievable dose in the tumour is reduced, and excessive toxicity leads to suboptimal treatment [24, 25]. The unique properties of MSNs, such as high pore volume and large surface area, are functionalization surface areas for application in controlled drug delivery and release. Modification of MSNs by some agents makes it possible to target delivery. Amine functional groups on MSNs improve their pH-sensitive release kinetic properties, an essential factor for targeted drug release near the acidic cancerous tissues, and inhibit toxic side effects [26].

Design and preparation of controlled-release drug systems are more useful in disease management. Mesoporous silica material is more noticeable for this purpose. Indeed, the high volume of mesoporous silica porosity sets some active biological material inside these pores. Therefore, a regular network of these porous materials is directed to proper loading and release results. MSNs with high loading capacity and vast surface area are presented as suitable carriers for drug delivery.

On the other hand, MSNs show great potential for controlled drug release by using materials such as nanospheres, organic molecules, or supermolecules as door cappers or coated layers [24]. Therefore, the systems with sensitive release capability to factors such as light, pH, or other chemical motivations have been obtained [24, 27, 28]. Veneer is also a standard method for creating a controlled release system that uses polymers and liposomes [29]. Eudragit is a synthetic acrylic polymer often used in solid pharmaceutical forms. Since they have great chemical stability and compatibility for many applications in various products with different physical and chemical properties [30]. Non-pH-dependent forms of Eudragit, such as RL, RS, and NE, used in films or coats of some dosage forms cause slow drug release [31, 32]. This material has many applications in the formulation of MSNs to obtain a suitable release profile [33].

Although current treatments have been able to improve the prognosis of cancer patients, many of these tumours do not respond to current treatments. Therefore, in the case of gastric cancer, as in other cancers, efforts are being made to find more effective drugs with fewer side effects. This study aims to place insoluble drugs such as Celas in MSNs to increase solubility and physicochemical stability. Moreover, targeted drug delivery is improved by releasing Celas under the influence of pH with a longer duration by using modification and Eud coating on the surface of MSNs. This study investigated the performance of MSNs loaded with Celas to counteract gastric cancer cells. The results of this study could help to evaluate the possibility of using Celas@MSN-NH2/Eud as a suitable drug carrier in the treatment of gastric cancer in future studies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB), tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS), 3-aminopropyl tetraethoxysilane (APTS), and all other solvents and reagents were purchased from Merck. Darmstadt, Germany) and used without further purification. Celas was from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany), and Eud was obtained from Evonik Industries, Essen, Germany. The AGS cell lines were purchased from the National Cell Bank of Iran (Pasteur Institute, Iran). Other media supplements for cell culture, such as Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) with high glucose, fetal bovine serum (FBS), and amphotericin B, were purchased from Gibco (USA), and penicillin-streptomycin solution from Sigma (USA).

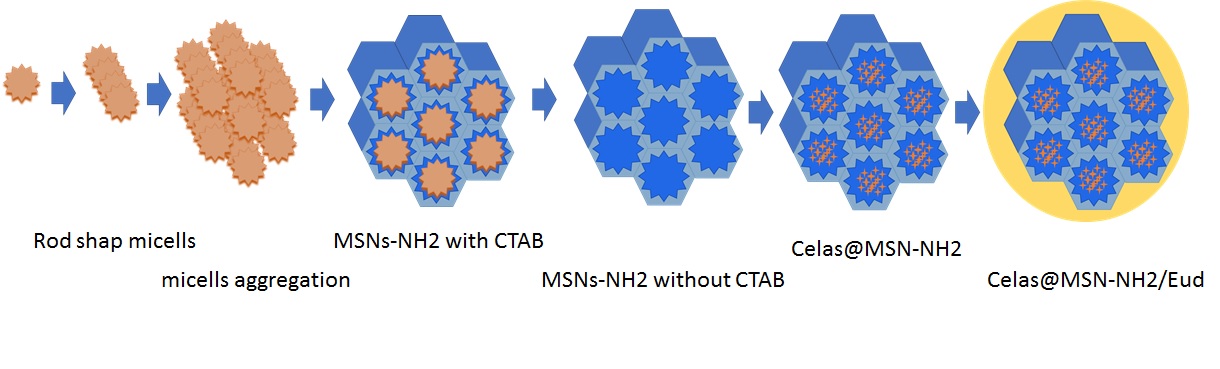

Preparation of Celas@MSN-NH2/Eud

To prepare MSNs with internal amines by one-step and sol-gel method, 1 g of CTAB was dissolved in 480 ml of distilled water and 3.5 ml of 2 M NaOH was added to it and at 1000 rpm was heated and after reaching the solution temperature of 80 °C, 5 ml of TEOS and 0.21 ml of APTS were added dropwise and kept at 80 °C for 2 h [34, 35]. The obtained nanoparticles (MSN-NH2) were refluxed with an ethanol solution of NH4NO3 at 80 °C for 6 h to remove CTAB and then were washed several times with distilled water and ethanol. For loading the drug inside MSN-NH2, 50 mg of prepared CTAB removed MSN-NH2 was added to 5 ml of Cela's solution (2 mg/ml), and the final mixture was stirred in the dark at room temperature for 24 h.

Then, the mixture was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. After separating the supernatant solution, the particles (Celas@MSNs-NH2) were washed with 5 ml of distilled water and dried using a freeze-dryer. To coat the surface of nanoparticles, dissolve 100 mg of Eud in 5 ml of ethanol and let it stir for 4 h. Afterward, the solution was added dropwise to a mixture containing 50 mg MSNs-NH2 charged with Celas dispersed in 10 ml of deionized water and refrigerated for 12 h. The final particles (Celas@MSNs-NH2/Eud) were extracted by centrifugation and were dried with a freeze-dryer.

Fig. 1: Schematic illustration of the multistep synthesis of Celas@MSN-NH2/Eud

Investigation of the properties of Celas@MSNs-NH2/Eud

In the next step, prepared Celas@MSNs-NH2/Eud properties were studied. The particle size and zeta potential were investigated by zeta sizer. Also, SEM was used to study the morphological properties of the coated and basic MSNs-NH2. To study the mesoporous structure of nanoparticles, N2 adsorption-desorption device was used to describe the pore volume and surface area of MSNs and also the mesoporous character of it. The crystal structure of MSNs-NH2 was confirmed using XRD, and the silica and amino structure of nanoparticles was confirmed using FTIR [36, 37].

MSNs-NH2 were loaded with Celas, and the amount of drug loaded was measured by the following equations by a UV spectrophotometer device at 450 nm:

% loading efficiency  … (1)

… (1)

% Loading capacity ..(2)

..(2)

The in vitro drug release from Celas@MSNs-NH2/Eud in two phosphate buffer media with pH 5.5 and 7.4 was investigated by use of the spectrophotometry method. 2 mg of Celas@MSN-NH2/Eud and 2 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) were added into a dialysis bag. Afterward, the bag was closed and placed in 20 ml PBS, shaken at 100 rpm, and left at 37 °C in a dark place. The samples were taken at different intervals, and fresh PBS was replaced. The released drug was measured by a UV spectrophotometer and repeated 3 times.

Cell culture

The cells were cultured in DMEM at 37 °C in a humidified air atmosphere containing 5% (v/v) CO2, supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 µg/ml of streptomycin, 100 UI/ml of penicillin, and 0.25 µg/ml amphotericin B and the required cell stock was prepared.

Evaluation of cell proliferation by MTT method

Initially, the anti-proliferation effects of the Celas and Celas@MSNs-NH2/Eud on AGS cell lines were identified. To evaluate anti-proliferative activity, the cells were treated with different concentrations of these compounds and cell viability was measured by the ability of the mitochondrial enzyme succinate dehydrogenase to cleave the tetrazolium salt 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2ol) 2, 5 diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT), and produce formazone with blue color as described previously [38, 39]. Different dilutions of Celas@MSNs-NH2/Eud were prepared with the same Celas concentration as free Celas.

At this stage, 6 × 103 AGS cells per well were seeded onto 96-well culture plates and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 24 h. Subsequently, the overlay medium was removed, and the cells were incubated with different Celas or Celas@MSN-NH2/Eud concentrations at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for a further 48 h. After that, the cell supernatant was removed, and each well was washed with 100 μl of PBS, and then 60 μl of MTT solution (1 mg/ml in PBS) was added to each well. The plates were incubated for 4 h at 37 °C, and 100 μl of DMSO was added to the wells and placed on a shaker for 15 min. The absorbance was read on an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay reader at 570 nm. Each experiment was carried out in triplicate, and the following formula determined the survival percentage of the treated cultured cells:

The half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of Celas or Celas@MSN-NH2/Eud was determined by regression analysis and relevant models with a regression probit model in the SPSS software (version 16).

Evaluation of apoptosis by flow cytometry

In the next step, the effects of Celas and Celas@MSN-NH2/Eud on the induction of apoptosis were investigated. AGS cells were cultured in 6-well plates for 24 h and incubated with one-time IC50 concentrations for 24 and 48 h. Then, the cells were gathered from the bottom of the plates and washed twice with calcium buffer, re-suspended in 100 μl of 1× binding buffer containing FITC-conjugated annexin-V (2μl) and one μl of propidium iodide (PI; 100 μg/ml), and left to incubate for further 20 min in the dark on ice and the samples were analyzed by flow cytometry [40, 41].

Statistical analysis

Each experimental value was expressed as the mean±standard deviation (SD). SPSS software (version 16) was used to obtain dose-response curves by conducting nonlinear regression analysis. IC50 values were determined using a regression probit model in the SPSS software (version 16).

RESULTS

Particle size, particle distribution, and zeta potential

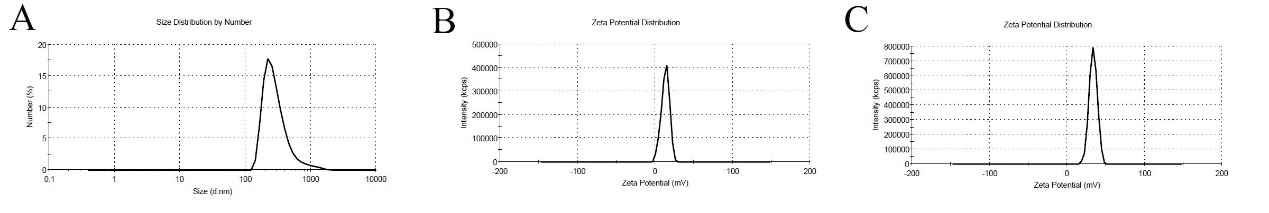

The measured size of Celas@MSNs-NH2/Eud by DLS was 310 nm, and 0.219 nm polydispersity index (PDI) referred to acceptable particle distribution as homogenize and uniform (fig. 2A). Also, the obtained zeta potential of MSNs-NH2 and Celas@MSNs-NH2/Eud were 13.1 and 33.6, respectively (fig. 2B and 2C) the positive charge of MSNs-NH2 reflected amine functional groups on them and strongly positive zeta potential values exhibited the polycationic Eud precipitated on Celas@MSNs-NH2/Eud, as a result of zeta its acceptable within the range ± 30 to ensure the stability of the nanoparticles.

Fig. 2: A) Size distribution of Celas@MSNs-NH2/Eud. B) Zeta potential of MSNs-NH2. C) Zeta potential of Celas@MSNs-NH2/Eud

Evaluation of morphological properties of nanoparticles using SEM microscope

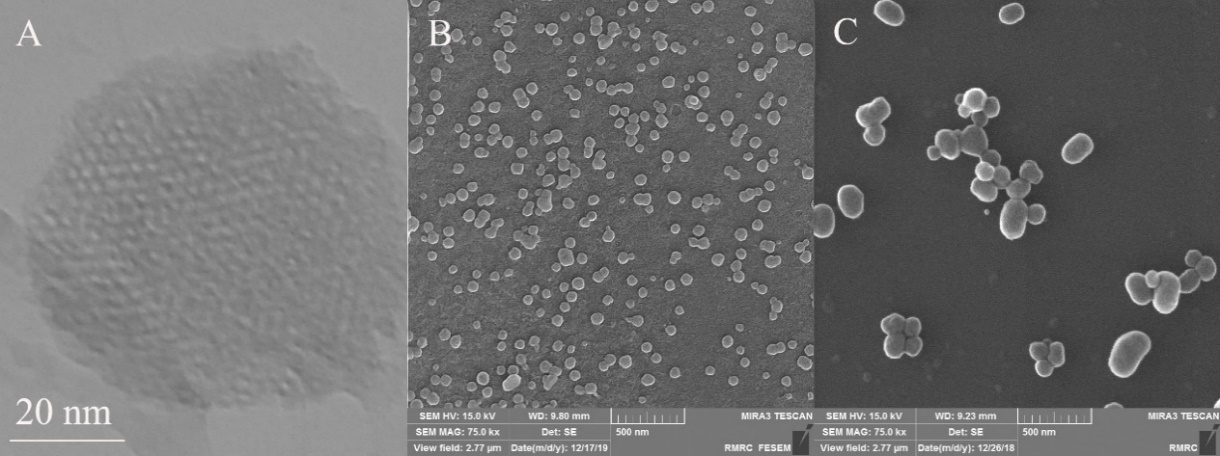

TEM and SEM imaging of MSNs-NH2, according to fig. 3A and B, show almost spherical particles with uneven surfaces and sizes between 50 to 100 nm and uniform particle size distribution. Moreover, the honeycomb shape of the porosity is clear, too. Celas@MSNs-NH2/Eud had a size between 200 to 300 nm and a smooth surface, as shown in fig. 3C, which confirmed the DLS results. This is related to coating with Eud. Leads to an increased size of nanoparticles.

Fig. 3: A) TEM image of MSN-NH2. B) SEM image of MSN-NH2. C) SEM image of Celas@MSNs-NH2/Eud

Surface area characteristics, pore size, and pore size distribution of prepared nanoparticles using an N2 adsorption-desorption device

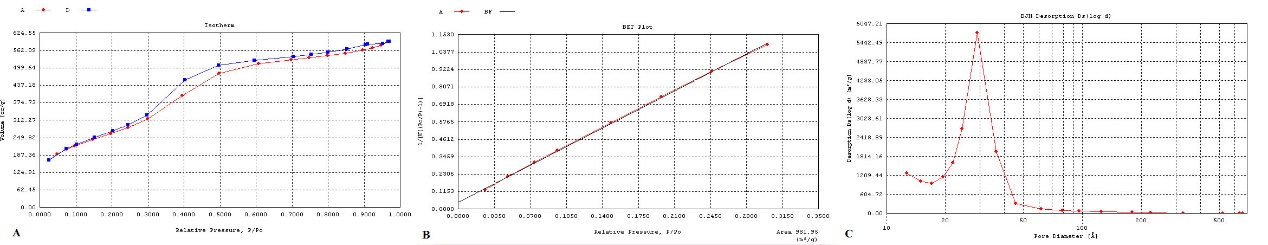

Fig. 4A and table 1 show the isotherm obtained from MSN-NH2, which proves the presence of mesoporous particles (particles with a pore size of 2-50 nm) by the distance between the adsorption and desorption branches and the sigmoidal shape of the isotherm. The obtained BET diagram also showed a surface area of 981.95 m2/g (fig. 4B), one of the main and important characteristics of MSNs. The pore size of MSN-NH2 (fig. 4C) was about 2.8 nm, calculated and evaluated using the BJH equation.

Fig. 4: A) Isotherm diagram of MSN-NH2. B) BET diagram of MSN-NH2. C) BJH diagram of MSN-NH2

Table 1: BET result of the MSN-NH2

| Surface area | 981.95 m2/g |

| Pore volume | 2.8 nm |

Fig. 5: A) FTIR graph of MSNs-NH2. B) XRD diagram of MSNs-NH2

Evaluation of surface modification on MSN-NH2 by FTIR method

Fig. 5A shows the stretching Si-O bond at 1056 cm-1 as a sharp peak, and at 790 cm-1, a stretching frequency of the Si-O peak was visible. N-H and O-H stretching bonds presented a wide pe ak at 3400 cm-1. The peak observed at 2900 cm-1 is related to the stretching bond of C-C, which proves the conjugation of amine groups on MSNs by APTS.

Evaluation of crystalline properties of MSNs-NH2 by XRD technique

XRD results obtained from MSN-NH2 are shown in fig. 5B. The peaks around 2θ = 1.8, 3.6, and 5.7, which were the reflection on pages 100, 110, and 200, proved the existence of a two-dimensional and hexagonal structure, which is one of the characteristics of MSNs, and the shift of these peaks than the pattern of MSNs was due to the presence of amino groups.

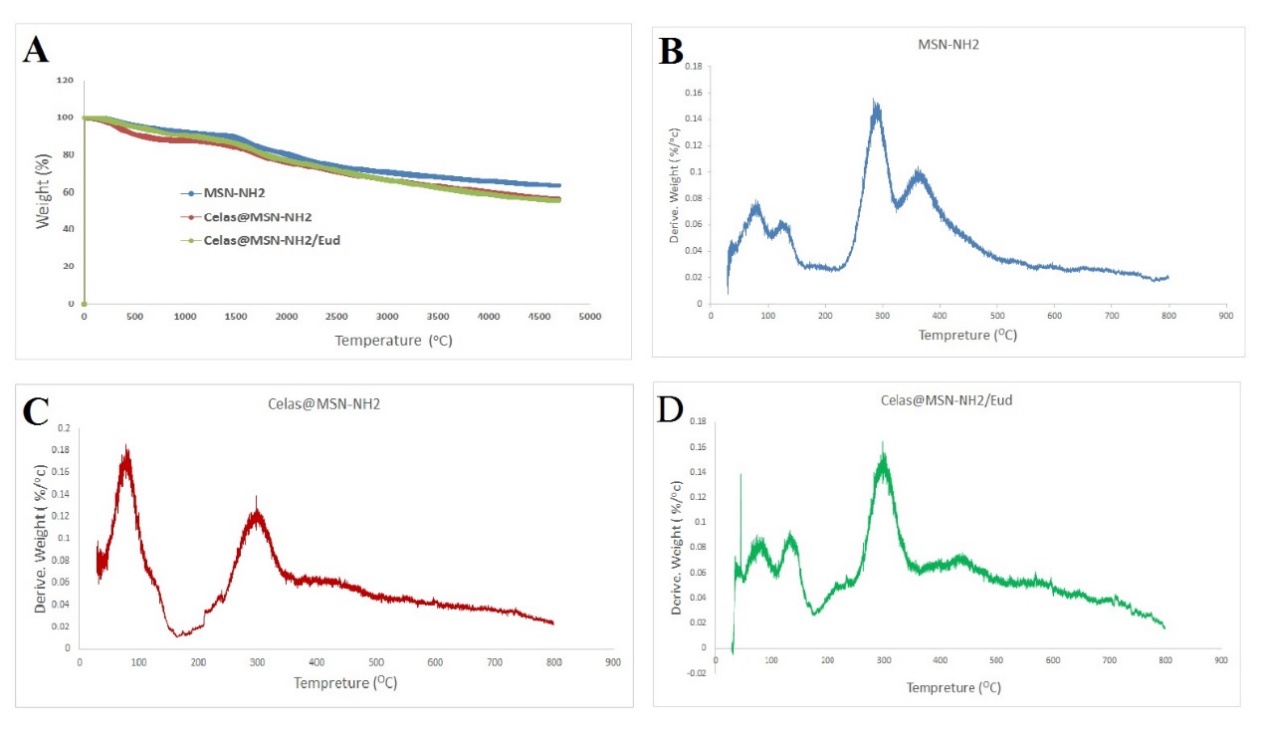

Evaluation and proof of surface changes on prepared nanoparticles using the TGA method

The entry of organic compounds into silica in MSNs-NH2 samples is confirmed by the TGA test as much as possible. As shown in fig. 6, MSN-NH2 lose about 10% of their weight up to 150 °C, which can be due to the evaporation of water and other solvents adsorbed on the surface of the nanoparticles. At a temperature of 300 °C, all nanoparticles lost about 10% of their weight, probably due to the decomposition of amine groups on the surface of these nanoparticles. At a final temperature of 787 °C, the weight reduction percentage of Celas@MSN-NH2 and Celas@MSN-NH2/Eud nanoparticles was more than MSN-NH2, indicating that the carbon-containing organic compounds on the surface of these nanoparticles. There is also more change in the weight loss of Celas@MSN-NH2/Eud than Celas@MSN-NH2 due to the coating of eud on the surface of these nanoparticles.

Fig. 6: Thermogravimetric analysis graph of nanoparticles

Load rate of formulated nanoparticles

The Celas loading amounts in Celas@MSN-NH2 are listed in table 1.

Although one of the important characteristics of MSNs is the high loading capacity, it is low for drugs with low solubility in water. As seen in table 2, due to the low dissolution of Celas in water, the amount of drug loaded in Celas@MSN-NH2 was not high. However, the hydrogen bond between the amine groups on the MSN-NH2 surface and O-H groups of Cela’s molecules could help to increase the drug loading. Moreover, Eud coat on MSN-NH2 after loading of Celas due to capture Celas, which sedimented on MSN-NH2 surface for more drug loading.

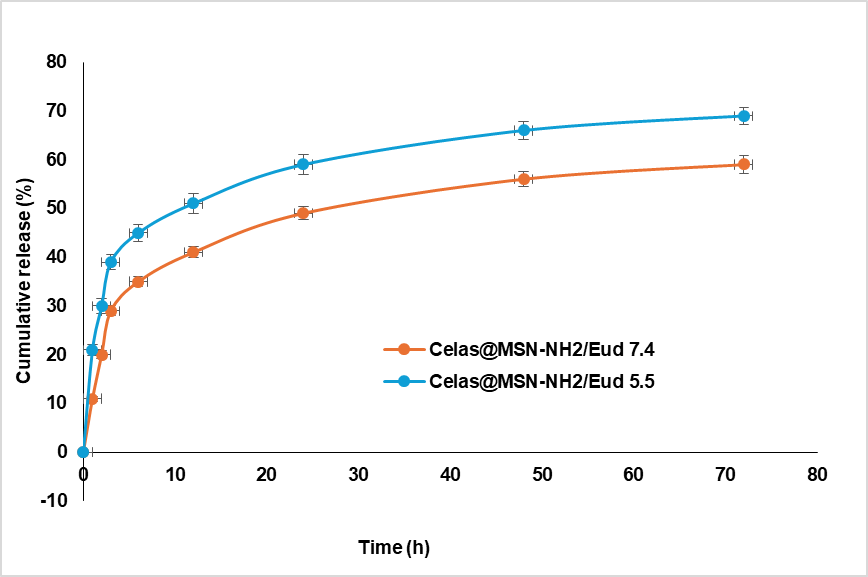

Evaluation of drug release from Celas@MSN-NH2

Fig. 7 was obtained from the release of the drug from Celas@MSN-NH2/Eud in two buffer media with pH 5.5 and 7.4; the release of the drug was controlled and pH-sensitive. As in fig. 7, the coated layer of Eud was prevented from burst release of Celas and led to a controlled release system. Moreover, due to the presence of hydrogen bonds between MSN-NH2 and Celas, the release manner was also sensitive to pH. Since cancerous tissues are more acidic than normal tissues, therefore, the usage of Celas@MSN-NH2/Eud leads to more release of Celas in acidic environments of cancerous tissues.

Cell test results

Anti-proliferative activity on AGS cells

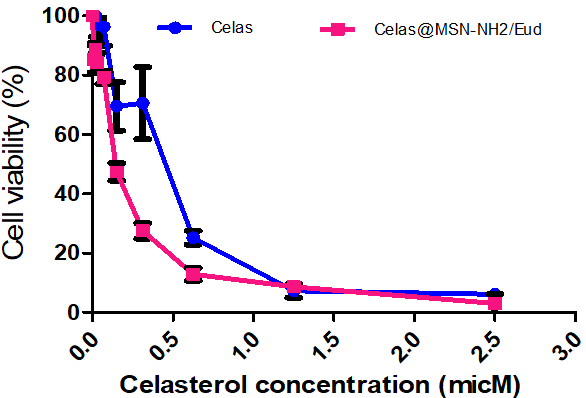

To evaluate the antiproliferative activity of Celas and Celas@MSN-NH2/Eud on AGS cell lines, the cells were treated with different concentrations, and cell viability was determined using an MTT assay.

The results showed that cell viability was significantly reduced in a dose-dependent manner following treatment with the Celas and nanoparticles (P<0.05, fig. 8). The IC50 and confidence intervals (CI) 95% of the Celas was 0.3756 (CI95%:0.3207-0.44 μM), higher than that of Celas@MSN-NH2/Eud, which was 0.1456 (CI95: 0.1277-0.1668 μM) against AGS cells. The results of this MTT test show that the inhibitory growth effects of Celas@MSN-NH2/Eud at all concentrations were more significant than free Celas (P<0.01).

Table 2: Percent loading efficiency and loading capacity of Celas@MSN-NH2/Eud. Note: data presented as mean±standard deviation

| % loading capacity | % loading efficiency | Nanoparticle |

| 2.6±0.28 | 5.7±0.52 | Celas@MSN-NH2/Eud |

n= 3, data given in mean±SD

Fig. 7: Diagram of celas release from celas@MSN-NH2/Eud at pH 7.4 and 5.5 per time hour

Fig. 8: Antiproliferative activity of Celas@MSN-NH2/Eud compared to celas in AGS cell. AGS cell lines were treated with different concentrations of Celas@MSN-NH2/Eud and Celas for 48 h, and cell viability was determined using an MTT assay. The data indicate the mean±standard error of three independent experiments' mean (SEM). Using the probit regression model, data (curves) show that the antiproliferative activity of the extract between Celas@MSN-NH2/Eud and Celas was significantly different (P<0.01); AGS: Adenocarcinoma gastric cell line

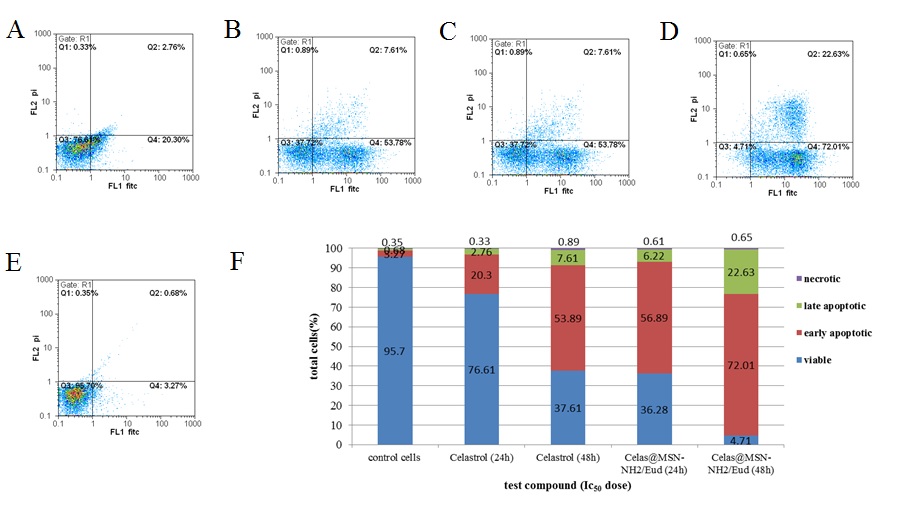

Fig. 9: Flow cytometric analysis of apoptosis in AGS cell line, AGS (adenocarcinoma gastric) cells were treated with one-time IC50 concentrations of Celas and Celas@MSN-NH2/Eud, stained with both propidium iodide (PI) and Annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), and analyzed by flow cytometry; A: Flow cytometry analysis of apoptosis induced activity of, a, b, c, d, and e: treated with Celas 24h, Celas 48h, Celas@MSN-NH2/Eud 24h, Celas@MSN-NH2/Eud 48h and cell control respectively; B: the apoptosis ratio

Evaluation of apoptosis by the annexin V PI method

To determine whether the antiproliferation of these compounds involved the induction of apoptosis, AGS cells were treated with the corresponding IC50 concentrations of Celas and Celas@MSN-NH2/Eud, stained with both Propidium iodide (PI) and Annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Flow cytometric analysis of apoptosis showed that the Celas and Celas@MSN-NH2/Eud induced cell death through early apoptosis. The percentages of early apoptosis cells in the cells treated with the Celas and Celas@MSN-NH2/Eud treatment for 48 h were 53.78% and 72.01%, respectively. The results show that despite the use of Celas@MSN-NH2/Eud with a Celas loading capacity of 2.6% and although the Celas content of these nanoparticles was about 4 times lower, free Celas showed far fewer effects on secondary apoptosis of AGS cells than Celas@MSN-NH2/Eud, which confirmed the significant effect of using Celas@MSN-NH2/Eud to deliver Celas. Furthermore, these results were consistent with the results of MTT (fig. 9).

DISCUSSION

This study investigated a system of Celas@MSN-NH2/Eud with a pH-sensitive for combat to AGS cells. Amongst all the nanoparticles, MSNs have shown great potential as a drug delivery carrier. Inorganic nanocarriers such as MSNs have high physicochemical and biochemical stability. MSNs contain unique characteristics such as morphology, pore size and uniform particle size, tunnel cavity, high surface area and pore volume, easy surface functionalization, etc. The particle size and zeta potential of prepared nanoparticles using a zeta sizer showed a size of about 300 nm and a zeta potential of+33.6 mV. As the zeta potential ia important to satisfy the stability of nanoparticles and prevent aggregation with increase uptake and targeting to cance cells. These differences from the base-prepared MSN-NH2 (below 100 nm and+13 mV) confirmed the successful coating with Eud. SEM was also used to study the morphological properties of nanoparticles. Therefore, the results showed a rough surface and 50 to 100 nm size for primary nanoparticles and 250 to 300 nm with a smooth surface for Eud-coated nanoparticles. The results of the final nanoparticles by SEM show a smooth surface, proving the slow precipitate of Eud as a uniform film. For the study of the mesoporous structure of nanoparticles, an N2 adsorption-desorption device was used. The obtained BET diagram showed a surface area of 981.95 m2/g, and the pore size obtained from MSN-NH2 is about 2.8 nm, which was calculated and evaluated using the BJH equation. The sigmoidal shape and the adsorption-desorption branch distance in the isotherm plot mention the mesoporous structure. Furthermore, the high surface area from the BET plot supports the before consequence, too. The crystal structure of mesoporous nanoparticles was confirmed using XRD, and the silica and amino structures of nanoparticles were confirmed using FTIR.

MSN-NH2 was loaded with Celas, and the amount of drug loaded was read using UV spectrophotometry at 450 nm, and thus, the amount of drug loaded was measured. 5.7% and 2.6% were obtained for loading efficiency and capacity, respectively. The release of the drug from Celas@MSN-NH2/Eud was investigated in two phosphate buffer media with pH 5.5 and 7.4, and finally, the pH-dependent release of these nanoparticles was determined. A good reason for this result is related to hydrogen bonds between surface amine groups on MSNs and drug molecules and, on the other hand, the slow release by gradually dissolving the Eud coat.

In the study of anti-proliferative activity, the results showed that cell viability was significantly dependent on reducing the dose of Celas and Celas@MSN-NH2/Eud (P<0.05). Also, after 48 h, the IC50 level of Celas and Celas@MSN-NH2/Eud on AGS cell line were 0.3756 μM (CI95%: 0.2020-0.44) and 0.1459 μM (CI95%:0.2768-0.687), respectively. The results of this MTT test show that the inhibitory effects of the growth of Celas@MSN-NH2/Eud at all concentrations obtained were more than Celas and could significantly increase the solubility of Celas in Celas@MSN-NH2/Eud. Also, flow cytometry results showed that Celas and nanoparticles loaded with Celas induce cell death due to primary apoptosis. And this is a good approach to the synthesis of a slow-release (control) and targeting cancer cells with minimum side effects.

The effect of Celas in suppressing tumour onset, invasion, and metastasis in a wide range of tumour cells and inhibitory effects on cancer models have been reported in some studies. For example, the effect of Celas in inhibiting cell growth and proliferation and inducing cell death in the HL-60 cell line, prostate cancer, and glioma cells [42]. In 2013, Ni et al. investigated the effect of Celas on cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in human multiple myeloma. This study found that inhibition of p56, the NFkB subunit, led to cell cycle arrest in myeloma cells [43]. In 2014, Chang et al. examined the effect of Celas on IL6, which promotes the proliferation and differentiation of prostate cancer cells. In this study, it was found that Celas reduced IL6 by affecting NFkB signalling [44]. In a 2015 study by Fribley et al., the effect of Celas on drug enhancement of the response to the primary protein (upr) was investigated, which is an effective method for eliminating and inhibiting oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSC) [45]. In 2014, Yoon et al. showed that Celas induces the death of several cell lines from breast cancer and colon cancer by inducing apoptosis Cells [46]. In a 2006 study by Yang H et al., Celas was reported as a potent proteasome inhibitor that inhibited the growth of human prostate cancer in nude mice [47]. In a 2009 study by Dr. He D et al., the effect of Celas on apoptosis was investigated. Finally, by inhibiting NF-Kappa B, Celas was able to enhance the anti-cancer effect of gambogic acid in oral squamous cell carcinoma lines [48]. A 2010 study by Zhu H et al. Found that a combination of APO-2L/TRAIL and Celas had a strong synergistic antiproliferative effect against human cancer cells, including OVCAR-8 ovarian cancer, SW620 colon cancer, and D-95 lung cancer [49]. Su-wei Xu et al. showed that Celas could be used as an effective anti-cancer agent in the treatment of future lung cancer drug resistance [50]. A 2009 study by Dai Y et al. examined the effect of Celas in vitro and in vivo on human prostate cancer; the results of the study showed that Celas could be a promising new adjunctive regimen for the treatment of hormone-resistant prostate cancer [51]. A 2010 study by Ge P et al. Celas, as a potent proteasome inhibitor, induces apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in mouse glioma cells [52].

The results show that despite the use of Celas containing nanoparticles with a Celas loading rate of 2.6% and although the Celas content of these nanoparticles is about 4 times lower, free Celas has far fewer effects on secondary apoptosis of AGS cells than It has Celas-loaded nanoparticles, which confirms the significant effect of using MSN nanoparticles to deliver Celas.

As in our study, other research on Cela's drug delivery obtained some excellent results. In recent years, there has been a sizable interest in designing and developing drug delivery systems with a novel approach focused on enhancing the aqueous solubility of hydrophobic drugs like Celas and improving drug efficacy. Such as, Niemelä et al. Gluc-functionalized mesoporous silica nanoparticles could be an effective carrier for targeted drug delivery of Celas and induction of apoptosis in cancer cells [53]. JY et al. showed that CMSN-PEG (PEGylated polyaminoacid-capped CST-loaded MSN) nanoparticles have promising potential in treating solid tumours [54].

Finally, we can say this new drug delivery system of Celas with great cytotoxic effect on AGS cells could propose for future research to overcome stomach cancer.

CONCLUSION

According to the obtained results, it can be said that the use of MSNs is a suitable option for drug delivery to gastric cancer cells, and the use of Eud coating agents improves this drug delivery, which, according to research in this field, is more effective and has shown better performance. Therefore, it is suggested that more research be done on using these nanoparticles in drug delivery to cancer cells.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This article results from a research project, the 3696-project number in Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences (IR. SKUMS. REC.1397.119). We would like to thank the Vice Chancellor for Research and Technology of Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences for financing this research, as well as the staff of the Phytochemical Laboratory at the Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences Research Center for Medicinal Plants, who cooperated in implementing this project.

FUNDING

This research was funded by the Iran Government, By the Vice Chancellor for Research and Technology of Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences, grant number 3696 mainly. Moreover, supplement grant numbers 3835 and 5294 were used for this project.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization, investigation, writing, and Supervision; Pegah Khosraviyan and Mohammad Taghi Moradi; investigation and writing Dhiya Altememy, Leila Hashemi and Pooria Mohammadi Arvejeh, Majid Asadi-Samani, Fariba Houshmand and Dhiya Altememy; review, investigation and editing all authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors confirm that they don’t have conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

Ames BN. Prevention of mutation cancer and other age associated diseases by optimizing micronutrient intake. J Nucleic Acids. 2010;2010(1):725071. doi: 10.4061/2010/725071, PMID 20936173.

Wu CW, Chi CW, Lin WC. Gastric cancer: prognostic and diagnostic advances. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2002;4(6):1-12. doi: 10.1017/S1462399402004337, PMID 14987390.

Jiang Y, Li T, Liang X, Hu Y, Huang L, Liao Z. Association of adjuvant chemotherapy with survival in patients with stage II or III gastric cancer. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(7):e171087. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.1087, PMID 28538950.

Park S, Ha S, Kwon HW, Kim WH, Kim TY, Oh DY. Prospective evaluation of changes in tumor size and tumor metabolism in patients with advanced gastric cancer undergoing chemotherapy: association and clinical implication. J Nucl Med. 2017;58(6):899-904. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.182675, PMID 28572288.

Zhou F, Yu XL, Liang P, Cheng Z, Han ZY, Yu J. Microwave ablation is effective against liver metastases from gastric adenocarcinoma. Int J Hyperthermia. 2017;33(7):830-5. doi: 10.1080/02656736.2017.1306120, PMID 28540787.

Hajizadeh N, Pourhoseingholi MA, Baghestani AR, Abadi A, Zali MR. Bayesian adjustment of gastric cancer mortality rate in the presence of misclassification. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2017;9(4):160-5. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v9.i4.160, PMID 28451063.

Rahamooz Haghighi SR, Asadi MH, Akrami H, Baghizadeh A. Anti-carcinogenic and anti-angiogenic properties of the extracts of Acorus calamus on gastric cancer cells. Avicenna J Phytomed. 2017;7(2):145-56. PMID 28348970.

Florea AM, Busselberg D. Cisplatin as an anti-tumor drug: cellular mechanisms of activity drug resistance and induced side effects. Cancers. 2011;3(1):1351-71. doi: 10.3390/cancers3011351, PMID 24212665.

Taylor RC, Cullen SP, Martin SJ. Apoptosis: controlled demolition at the cellular level. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9(3):231-41. doi: 10.1038/nrm2312, PMID 18073771.

Liby KT, Yore MM, Sporn MB. Triterpenoids and rexinoids as multifunctional agents for the prevention and treatment of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7(5):357-69. doi: 10.1038/nrc2129, PMID 17446857.

Martinez Perez C, Ward C, Cook G, Mullen P, McPhail D, Harrison DJ. Novel flavonoids as anti-cancer agents: mechanisms of action and promise for their potential application in breast cancer. Biochem Soc Trans. 2014;42(4):1017-23. doi: 10.1042/BST20140073, PMID 25109996.

Gholamian Dehkordi N, Elahian F, Khosravian P, Mirzaei SA. Intelligent TAT‐coupled anti‐HER2 immunoliposomes knock downed MDR1 to produce chemosensitize phenotype of multidrug resistant carcinoma. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234(11):20769-78. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28683, PMID 31001890.

Yang MH, Kim J, Khan IA, Walker LA, Khan SI. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-activated gene-1 (NAG-1) modulators from natural products as anti-cancer agents. Life Sci. 2014;100(2):75-84. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2014.01.075, PMID 24530873.

Forbes Hernandez TY, Giampieri F, Gasparrini M, Mazzoni L, Quiles JL, Alvarez Suarez JM. The effects of bioactive compounds from plant foods on mitochondrial function: a focus on apoptotic mechanisms. Food Chem Toxicol. 2014 Jun;68:154-82. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2014.03.017, PMID 24680691.

Kalimuthu S, Se Kwon K. Cell survival and apoptosis signaling as therapeutic target for cancer: marine bioactive compounds. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14(2):2334-54. doi: 10.3390/ijms14022334, PMID 23348928.

Mangal M, Sagar P, Singh H, Raghava GP, Agarwal SM. NPACT: naturally occurring plant-based anti-cancer compound activity target database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013 Jan 1;41(D1):D1124-9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1047, PMID 23203877.

Cragg GM, Newman DJ. Natural products: a continuing source of novel drug leads. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1830(6):3670-95. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.02.008, PMID 23428572.

Khosravian P, Heidari Soureshjani S, Yang Q. Effects of medicinal plants on radiolabeling and biodistribution of diagnostic radiopharmaceuticals: a systematic review. Plant Sci Today. 2019;6(2):123-31.

Lee JH, Koo TH, Yoon H, Jung HS, Jin HZ, Lee K. Inhibition of NF-κB activation through targeting IκB kinase by celastrol a quinone methide triterpenoid. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;72(10):1311-21. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.08.014, PMID 16984800.

Sassa H, Kogure K, Takaishi Y, Terada H. Structural basis of potent antiperoxidation activity of the triterpene celastrol in mitochondria: effect of negative membrane surface charge on lipid peroxidation. Free Radic Biol Med. 1994;17(3):201-7. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)90075-2, PMID 7982625.

He Q, Gao Y, Zhang L, Zhang Z, Gao F, Ji X. A pH-responsive mesoporous silica nanoparticles based multi-drug delivery system for overcoming multi-drug resistance. Biomaterials. 2011;32(30):7711-20. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.06.066, PMID 21816467.

Kusterbeck AW, Charles PT, Melde BJ, Trammell SA, Adams AA, Deschamps JR, editors. Biosensor UUV payload for underwater detection. Ocean Sensing and Monitoring; 2010. p. 767805. doi: 10.1117/12.850317.

Bremmell KE, Prestidge CA. Enhancing oral bioavailability of poorly soluble drugs with mesoporous silica based systems: opportunities and challenges. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2019;45(3):349-58. doi: 10.1080/03639045.2018.1542709, PMID 30411991.

Slowing II, Vivero Escoto JL, Wu CW, Lin VS. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles as controlled release drug delivery and gene transfection carriers. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60(11):1278-88. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.03.012, PMID 18514969.

Heurtault B, Saulnier P, Pech B, Proust JE, Benoit JP. Physicochemical stability of colloidal lipid particles. Biomaterials. 2003;24(23):4283-300. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00331-4, PMID 12853260.

Cho K, Wang X, Nie S, Chen ZG, Shin DM. Therapeutic nanoparticles for drug delivery in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(5):1310-6. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1441, PMID 18316549.

Mohammadi ZG, Badiei AR, Khaniania Y, Hadadpour M. One-pot synthesis of polyhydroquinolines catalyzed by sulfonic acid functionalized SBA-15 as a new nanoporous acid catalyst under solvent-free conditions. Iranian Journal of Chemistry & Chemical Engineering International English Edition. 2010 Jun;29(2):1-10. doi: 10.30492/IJCCE.2010.6687.

Badiei A, Jahangir HI, Ziarani G. Incorporation of ibuprofen into SBA-15; drug loading and release properties. Dyn Biochem Process Biotechnol Mol Biol. 2009;3:48-50.

Wang D, Huang J, Wang X, Yu Y, Zhang H, Chen Y. The eradication of breast cancer cells and stem cells by 8-hydroxyquinoline loaded hyaluronan modified mesoporous silica nanoparticle-supported lipid bilayers containing docetaxel. Biomaterials. 2013;34(31):7662-73. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.06.042, PMID 23859657.

Ceballos A, Cirri M, Maestrelli F, Corti G, Mura P. Influence of formulation and process variables on in vitro release of theophylline from directly compressed Eudragit matrix tablets. Farmaco. 2005;60(11-12):913-8. doi: 10.1016/j.farmac.2005.07.002, PMID 16129436.

Huyghebaert N, Vermeire A, Remon JP. In vitro evaluation of coating polymers for enteric coating and human ileal targeting. Int J Pharm. 2005;298(1):26-37. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2005.03.032, PMID 15894443.

Haznedar S, Dortunc B. Preparation and in vitro evaluation of eudragit microspheres containing acetazolamide. Int J Pharm. 2004;269(1):131-40. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2003.09.015, PMID 14698584.

Kaboli MA, Hashim AA, Altememy D, Chaleshtori JS, Rezaee M, Hosseini SA. Silk fibroin-coated mesoporous silica nanoparticles enhance 6-thioguanine delivery and cytotoxicity in breast cancer cells. Int J Appl Pharm. 2025;17(1):275-83. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2025v17i1.52882.

Khosravian P, Shafiee Ardestani M, Khoobi M, Ostad SN, Dorkoosh FA, Akbari Javar H. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles functionalized with folic acid/methionine for active targeted delivery of docetaxel. Onco Targets Ther. 2016 Dec 1;9:7315-30. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S113815, PMID 27980423.

Khosravian P, Khoobi M, Ardestani MS, Daryasari MP, Hassanzadeh M, Ghasemi Dehkordi P. Enhancement antimicrobial activity of clarithromycin by amine functionalized mesoporous silica nanoparticles as drug delivery system. Lett Drug Des Discov. 2018;15(7):787-95. doi: 10.2174/1570180815666180117155818.

Altememy D, Jafari M, Naeini K, Alsamarrai S, Khosravian P. In vitro evaluation of metronidazole-loaded mesoporous silica nanoparticles against trichomonas vaginalis. Int J Pharm Res; 2020. doi: 10.31838/ijpr/2020.SP1.400.

Altememy D, Khoobi M, Javar HA, Alsamarrai S, Khosravian P. Synthesis and characterization of silk fibroin-coated mesoporous silica nanoparticles for tioguanine targeting to leukemia. Int J Pharm Res. 2021:12(2)1181. doi: 10.31838/ijpr/2020.SP2.145.

Moradi MT, Karimi A, Alidadi S. In vitro antiproliferative and apoptosis-inducing activities of crude ethyl alcohol extract of Quercus brantii L. Acorn and subsequent fractions. Chin J Nat Med. 2016;14(3):196-202. doi: 10.1016/S1875-5364(16)30016-4, PMID 27025366.

Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65(1-2):55-63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4, PMID 6606682.

Pinna GF, Fiorucci M, Reimund JM, Taquet N, Arondel Y, Muller CD. Celastrol inhibits pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion in crohn’s disease biopsies. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;322(3):778-86. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.07.186, PMID 15336532.

Kannaiyan R, Shanmugam MK, Sethi G. Molecular targets of celastrol derived from thunder of god vine: potential role in the treatment of inflammatory disorders and cancer. Cancer Lett. 2011;303(1):9-20. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.10.025, PMID 21168266.

Nagase M, Oto J, Sugiyama S, Yube K, Takaishi Y, Sakato N. Apoptosis induction in HL-60 cells and inhibition of topoisomerase II by triterpene celastrol. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2003;67(9):1883-7. doi: 10.1271/bbb.67.1883, PMID 14519971.

Ni H, Zhao W, Kong X, Li H, Ouyang J. NF-kappa B modulation is involved in celastrol-induced human multiple myeloma cell apoptosis. PLOS One. 2014;9(4):e95846. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095846, PMID 24755677.

Chiang KC, Tsui KH, Chung LC, Yeh CN, Chen WT, Chang PL. Celastrol blocks interleukin-6 gene expression via downregulation of NF-κB in prostate carcinoma cells. PLOS One. 2014;9(3):e93151. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093151, PMID 24664372.

Fribley AM, Miller JR, Brownell AL, Garshott DM, Zeng Q, Reist TE. Celastrol induces unfolded protein response-dependent cell death in head and neck cancer. Exp Cell Res. 2015;330(2):412-22. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2014.08.014, PMID 25139619.

Yoon MJ, Lee AR, Jeong SA, Kim YS, Kim JY, Kwon YJ. Release of Ca2+ from the endoplasmic reticulum and its subsequent influx into mitochondria trigger celastrol-induced paraptosis in cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2014;5(16):6816-31. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2256, PMID 25149175.

Yang H, Chen D, Cui QC, Yuan X, Dou QP. Celastrol a triterpene extracted from the Chinese thunder of god vine is a potent proteasome inhibitor and suppresses human prostate cancer growth in nude mice. Cancer Res. 2006;66(9):4758-65. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4529, PMID 16651429.

He D, Xu Q, Yan M, Zhang P, Zhou X, Zhang Z. The NF-kappa B inhibitor celastrol could enhance the anti-cancer effect of gambogic acid on oral squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2009 Sep 25;9:343. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-343, PMID 19778460.

Zhu H, Ding WJ, Wu R, Weng QJ, Lou JS, Jin RJ. Synergistic anti-cancer activity by the combination of TRAIL/APO-2L and celastrol. Cancer Investig. 2010;28(1):23-32. doi: 10.3109/07357900903095664, PMID 19916747.

Xu SW, Law BY, Mok SW, Leung EL, Fan XX, Coghi PS. Autophagic degradation of epidermal growth factor receptor in gefitinib resistant lung cancer by celastrol. Int J Oncol. 2016;49(4):1576-88. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2016.3644, PMID 27498688.

Dai Y, DeSano JT, Meng Y, Ji Q, Ljungman M, Lawrence TS. Celastrol potentiates radiotherapy by impairment of DNA damage processing in human prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74(4):1217-25. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.03.057, PMID 19545787.

Ge P, Ji X, Ding Y, Wang X, Fu S, Meng F. Celastrol causes apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in rat glioma cells. Neurol Res. 2010;32(1):94-100. doi: 10.1179/016164109X12518779082273, PMID 19909582.

Niemela E, Desai D, Nkizinkiko Y, Eriksson JE, Rosenholm JM. Sugar-decorated mesoporous silica nanoparticles as delivery vehicles for the poorly soluble drug celastrol enables targeted induction of apoptosis in cancer cells. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2015 Oct;96:11-21. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2015.07.009, PMID 26184689.

Choi JY, Gupta B, Ramasamy T, Jeong JH, Jin SG, Choi HG. Pegylated polyaminoacid-capped mesoporous silica nanoparticles for mitochondria-targeted delivery of celastrol in solid tumors. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2018 May 1;165:56-66. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2018.02.015, PMID 29453086.