Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 3, 2025, 390-397Original Article

ELLAGIC ACID IN POMEGRANATE SEEDS AS A POTENTIAL THERAPEUTIC FOR ORAL CANCER VIA THE PI3K/AKT PATHWAY: AN IN SILICO

BRIAN LIMANTORO1, PUTRI ALFA MEIRANI LAKSANTI1,2, KURNIA DWI WULAN1,2, ANDI AYODHYA CHANDRA DIRAWAN3, FATMA YASMIN MAHDANI1,4*

1,2Faculty of Dental Medicine, Airlangga University, Surabaya, East Java, Indonesia. 3Faculty of Dental Medicine, Hasanuddin University, Makassar, South Sulawesi, Indonesia. 4Department of Oral Medicine, Airlangga University, Surabaya, East Java, Indonesia

*Corresponding author: Fatma Yasmin Mahdani; *Email: fatmayasminmahdani@fkg.unair.ac.id

Received: 16 Jan 2025, Revised and Accepted: 28 Mar 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: This study aims to evaluate the anticancer potential of ellagic acid, derived from pomegranate seeds, against oral cancer. Molecular docking was selected to predict the interaction between ellagic acid and the PI3K/AKT pathway, a critical signaling cascade in oral carcinogenesis.

Methods: An in silico approach was employed using MOE 2022 software to perform molecular docking simulations. Ellagic acid was docked against key proteins in the PI3K/AKT pathway to assess binding affinities and interaction dynamics. Additionally, ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) properties were predicted to evaluate the compound's drug-likeness and safety profile.

Results: The molecular docking analysis revealed that ellagic acid exhibits a binding affinity of-6.1004 kcal/mol to the PI3K protein, with an RMSD refinement value of 1.1516, indicating a stable interaction. ADMET predictions suggest favorable pharmacokinetic properties, including high human intestinal absorption and non-inhibitory effects on cytochrome P450 enzymes, implying low potential for drug-drug interactions. Toxicity assessments indicated no significant risks, supporting the compound's safety profile.

Conclusion: The in silico findings suggest that ellagic acid from pomegranate seeds may serve as a promising anticancer agent against oral cancer by effectively targeting the PI3K/AKT pathway. These results contribute to the existing literature by providing computational evidence of ellagic acid's mechanism of action and support further in vitro and in vivo studies to validate its therapeutic potential.

Keywords: Anticancer agent, Ellagic acid, Oral cancer, Pomegranate seed, Punecalagin

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i3.53519 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Oral cancer remains a significant global health concern, with high mortality rates and an estimated 377,000 new cases and nearly 177,000 deaths reported in 2020 [1–3]. The five-year survival rate is approximately 40%, underscoring the critical need for early diagnosis and effective prevention strategies to improve patient outcomes and increase life expectancy [2, 4, 5]. This impact is particularly pronounced in regions with limited healthcare access, such as rural areas, where early detection and specialised care are often unavailable. A major concern with oral cancer is its poor prognosis, especially when diagnosed at a late stage, which is often the case. Notably, 90–95% of these cases are Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma (OSCC), further emphasising the need for preventive strategies targeting modifiable risk factors to curb the rising incidence [6]. The global burden of oral cancer continues to grow, with stable age-standardized mortality rates indicating a need for focused public health interventions. By addressing risk factors and implementing targeted prevention strategies, healthcare systems worldwide can work towards reducing the incidence and improving the prognosis for those affected by this life-threatening disease [7]. Invasive treatments for oral cancer, including surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy, are standard but have notable limitations. Surgery can lead to significant functional and aesthetic impairments, affecting speech and swallowing [8]. Chemotherapy often causes side effects such as mucositis, infections, and salivary gland dysfunction, leading to secondary issues like dehydration and nutritional deficiencies [9]. Radiotherapy can damage healthy tissues, resulting in complications like mucositis, infections, and changes in saliva production [10]. These challenges highlight the need for alternative therapies that effectively manage cancer while minimizing adverse effects. Consequently, there is a growing interest in alternative therapies, particularly those involving herbal compounds, which have shown promise in clinical settings. For instance, studies have indicated that natural flavonoids can induce apoptosis in oral cancer cells, suggesting their potential as adjunctive treatments [11].

Indonesia, as a megadiverse nation with a vast agricultural economy, covers over 10.45 million hectares of cropland annually. Among its main agricultural products are biopharmaceutical plants, such as the pomegranate (Punica granatum L.), which grows throughout the region [12]. The fruit is well-known for its high phytonutrient content, supporting its medicinal qualities and making it a popular option for health-conscious consumers [13]. However, consumer favourability often leads to the disposal of pomegranate seeds as major organic waste, representing one-fifth of the whole fruit. Pomegranate seeds present a significant amount of punicalagins, which, after metabolic processes, transform into ellagic acid. Ellagic acid has demonstrated anticancer activity through the inhibition of molecular pathways such as PI3K/Akt and MAPK, which are crucial in triggering oral cancer progression. [14] Moreover, ellagic acid exhibits antioxidant and anti-inflammatory benefits through mechanisms such as COX-1 inhibition [6, 15]. Ellagic acid, derived from pomegranate seeds, is imperative to evaluate and promote this herbal agent extensively and commercially to raise societal awareness of oral health and explore its role as a complementary approach in oral cancer prevention and treatment.

Recent studies have highlighted the significance of the PI3K/Akt and MAPK signalling pathways in the development and progression of oral cancer [12, 14]. The PI3K/Akt pathway is frequently mutated in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas, indicating its pivotal role in tumorigenesis [14, 15]. Targeting this pathway has become a focal point in developing therapeutic strategies for oral cancer.

Pomegranate-derived compounds, particularly ellagic acid, have shown promise in modulating these critical pathways [12, 15]. Research indicates that ellagic acid can inhibit the PI3K/Akt pathway, thereby reducing cancer cell proliferation and inducing apoptosis. Additionally, ellagic acid has been observed to affect the MAPK pathway, further contributing to its anticancer effects [12, 14, 15]. These findings suggest that ellagic acid may serve as a valuable adjunct in oral cancer therapy by targeting key molecular mechanisms involved in disease progression. Furthermore, the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of ellagic acid enhance its therapeutic potential [6, 15–17]. By scavenging free radicals and inhibiting inflammatory mediators, ellagic acid helps mitigate oxidative stress and inflammation, both of which are implicated in cancer development. This multifaceted approach not only targets cancer cells directly but also modifies the tumor microenvironment, making it less conducive to cancer progression.

In light of these promising findings, further research is warranted to fully elucidate the mechanisms by which ellagic acid exerts its effects on oral cancer cells. Clinical studies are essential to determine the efficacy and safety of ellagic acid as a complementary therapy in oral cancer treatment. By advancing our understanding and application of pomegranate-derived compounds, we can develop more effective strategies to combat oral cancer and improve patient outcomes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Ellagic acid compounds

This study favors the active compound of PS, which was obtained from the PubChem website (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), then prepared as a 2–dimensional figure. The active compound used focuses on ellagic acid (CID 5281855) as the prime component in the PS. The researchers used the 5itd receptor (P27986) as the main regulatory subunit of oral cancer PI3K pathway. This study aims to evaluate the interaction of the compound to the receptors through 3–dimensional (3D) conformation retrieved from RCSB Protein Data Bank web page (https://www.rcsb.org/).

Research tools

This research deploys a computational approach comprising Chem3D. exe and BIOVIA_DS2024 for preparation of test materials and visualisation of docking results under the neglection of water molecules, page Lipinski Rule of Five (http://www.scfbio-iitd.res.in/) for the physicochemical tests, ADMETlab 3.0 (https://admetlab3.scbdd.com) for predicting ADME and toxicity, as well as MOE 2022 to identify active research target sites and obtain molecular docking results.

Methods

Preparation of ligand molecular structure and protein structure

The research commenced with the acquisition of test compounds and target proteins from PubChem and the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB), respectively, each compound being appropriately labelled according to its chemical name. Subsequently, docking visualisations of the protein P27986 were performed using Chem3D and BIOVIA Discovery Studio 2024, with water molecules omitted to focus on key interactions. Active site identification and peptide chain sequence optimisation were conducted utilising the Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) 2022 to enhance docking accuracy. MOE 2022 was selected for its comprehensive suite of computational chemistry tools, facilitating accurate modelling and visualisation of molecular interactions. Its robust algorithms and user-friendly interface render it a preferred choice for molecular docking studies. Prior to utilisation, validation studies were performed to ensure the reliability of MOE 2022 in predicting binding affinities and interaction modes [18].

Physicochemical test

Molecular docking test

Molecular docking studies were conducted by uploading the target protein, comparator compound, and test compound into MOE 2022. The software was configured to determine binding modes, Root mean Square Deviation (RMSD) values, and binding affinities in kcal/mol. A lower binding affinity indicated a greater propensity for the compound to interact with the target protein, as less energy was required for bond formation. The mode parameter reflected the variability of the bonds formed, while the RMSD values provided insights into the precision and accuracy of the docking predictions [24]. Visualisation of docking results was performed using MOE 2022 and BIOVIA Discovery Studio 2024 to analyse the number, type, and positions of bonds formed between the target protein and test compounds. This process involved uploading the docked conformations into the target protein framework to confirm interactions within the active site. Such visualisations were crucial for understanding the molecular interactions and guiding further optimisation of the compounds [25, 26]. The selection of the P27986 receptor, corresponding to the regulatory subunit alpha of Phosphoinositide-3-kinase (PIK3R1), was based on its biological relevance to oral cancer. Mutations and deregulation in the PI3K–PTEN–mTOR signalling pathway, in which PIK3R1 plays a critical role, are among the most frequently observed alterations in various cancers, including head and neck cancers. This makes PIK3R1 a pertinent target for investigating potential therapeutic agents against oral cancer [27].

RESULTS

Physicochemical test results

Ellagic acid (CID 5281855) exhibits physicochemical properties that align with Lipinski's Rule of Five, a set of criteria predictive of a compound's potential as an orally active drug in humans. Specifically, ellagic acid has a molecular mass of 302.19 daltons, which is well below the 500-dalton threshold, facilitating efficient absorption and distribution within the body. It possesses four hydrogen bond donors and seven hydrogen bond acceptors, both within the acceptable limits of fewer than five donors and ten acceptors, respectively. These characteristics suggest a favorable balance between solubility and permeability, essential for effective bioavailability. The compound's log P value, a measure of lipophilicity, is calculated to be approximately 1.7, comfortably below the maximum recommended value of 5. This indicates that ellagic acid maintains an appropriate balance between hydrophilicity and lipophilicity, promoting adequate membrane permeability without compromising solubility. Additionally, its molar refractivity falls within the range of 40 to 130, further supporting its drug-like potential. Collectively, these properties underscore ellagic acid's compliance with Lipinski's parameters, suggesting its promise as a candidate for oral drug development.

ADMET prediction results

ADME results

Table 1: Physicochemical test result of PS ellagic acid using Lipinski rule of five (RO5)

Compound |

Molecular mass |

Hydrogen bond donor |

Hydrogen bond acceptor |

Log P |

Molar refractivity |

Drug likeness |

Standard |

≤ 500 Da |

≤ 5 |

≤ |

≤ |

40–130 |

+ |

Ellagic Acid |

302.194 Da |

4 |

8 |

1.3128 |

77.146 |

+ |

Table 2: ADME prediction test results of PS ellagic acid

Compound |

Internal absorption (%) |

Human fraction unbound (Fu) |

CYP2D6 substrate and inhibitor |

Total clearance (log ml/min/kg) |

Ellagic Acid |

88.834 |

0.083 |

Negative |

0.637 |

Ellagic acid exhibits a pharmacokinetic profile that underscores both its therapeutic potential and the challenges associated with its clinical application. An intestinal absorption rate of 88.834% indicates efficient uptake through the gastrointestinal tract, facilitating its entry into systemic circulation. However, the compound's low fraction unbound in plasma (0.083) signifies that only 8.3% remains free to interact with biological targets, as the majority is bound to plasma proteins. This high protein binding could limit the bioactive fraction available for therapeutic action. The substantial protein binding of ellagic acid is consistent with existing literature, which reports that approximately 50–60% of the compound is bound to serum proteins following oral administration, with a half-life of about 8.4±1.8 h. This extensive binding may impede the free drug's availability to exert its therapeutic effects [28]. Moreover, ellagic acid is rapidly metabolised and eliminated from the body. Studies have detected maximum plasma concentrations approximately one-hour post-ingestion, with the compound being undetectable after four hours [29]. This swift elimination necessitates frequent dosing to maintain therapeutic levels, which could pose challenges in clinical settings. The limited bioavailability of ellagic acid is further compounded by its poor solubility and permeability, which restrict its absorption and systemic availability. These pharmacokinetic limitations have prompted the exploration of various formulation strategies to enhance its bioavailability. Approaches such as solid dispersions, micro and nanoparticles, inclusion complexes, self-emulsifying systems, and polymorphs have been investigated to improve solubility, stability, and absorption. [30] In summary, while ellagic acid demonstrates promising pharmacokinetic properties, including efficient intestinal absorption, its high plasma protein binding, rapid metabolism, and elimination, coupled with poor solubility and permeability, present significant challenges. Addressing these issues through advanced formulation strategies is essential to fully realise the therapeutic potential of ellagic acid as an orally administered agent.

Notably, ellagic acid is neither a substrate nor an inhibitor of the cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6) enzyme, which reduces the likelihood of drug-drug interactions involving this pathway. This characteristic is particularly advantageous in clinical settings where patients may be on multiple medications. The compound's total clearance rate is 0.637 (log ml/min/kg), indicating a moderate elimination speed from the body. This rate suggests that ellagic acid is neither rapidly cleared, which could necessitate frequent dosing, nor slowly eliminated, which might raise concerns about accumulation and potential toxicity. In summary, ellagic acid's high intestinal absorption and minimal interaction with CYP2D6 are promising for oral administration. However, its substantial plasma protein binding warrants consideration, as it may impact the effective concentration of the drug available for therapeutic action. These pharmacokinetic insights are crucial for informing dosing strategies and anticipating the compound's behaviour in clinical applications.

Table 3: Toxicity prediction test result of PS ellagic acid

Compound |

AMES toxicity |

Hepatotoxicity |

Human maximum tolerated dose (log mg/kg/day) |

Skin sensitisation |

Loael chronic toxicity (log mg/kg_bw/d) |

Ellagic Acid |

Negative |

Negative |

0.478 |

Negative |

2.893 |

Toxicity result

The toxicity assessment of ellagic acid (CID 5281855) provides crucial insights into its systemic safety profile, particularly in its potential application as an oral therapeutic agent. The negative result for AMES toxicity suggests that ellagic acid does not exhibit mutagenic properties, indicating a low risk of genetic mutations or DNA damage upon exposure. This finding is essential in assessing the compound’s carcinogenic potential, as mutagenicity is often linked to cancer development. Additionally, the absence of hepatotoxicity suggests that ellagic acid does not induce liver damage, a critical consideration for long-term administration. Many pharmacological agents exhibit hepatotoxic effects due to metabolic activation in the liver, leading to oxidative stress and cellular damage; however, the negative hepatotoxicity result implies that ellagic acid does not interfere with hepatic enzymatic functions or cause significant liver toxicity. The Human Maximum Tolerated Dose (HMTD) is recorded at 0.478 log mg/kg/day, reflecting a moderate safety margin for systemic exposure. This parameter is crucial in determining the upper limit of a compound's dosage before adverse effects manifest in human physiology. Although this value suggests an acceptable threshold, further pharmacokinetic studies are required to establish an optimal therapeutic dose that balances efficacy and safety. The negative skin sensitisation result indicates that ellagic acid does not induce allergic or hypersensitivity reactions upon dermal exposure. This is particularly relevant in pharmaceutical formulation, as compounds with skin sensitisation potential can pose risks in topical applications or during systemic absorption. The absence of skin irritation further supports its suitability for oral administration without significant risk of cutaneous adverse effects. Lastly, the Lowest Observed Adverse Effect Level (LOAEL) chronic toxicity value of 2.893 log mg/kg_bw/day provides insights into long-term exposure risks. This parameter reflects the lowest dose at which adverse effects are observed in chronic toxicity studies. A higher LOAEL value generally indicates a favourable safety profile, suggesting that ellagic acid does not exhibit significant toxic effects at standard therapeutic doses. However, additional in vivo evaluations are necessary to corroborate these findings and refine dosage recommendations for clinical applications.

Table 4: Docking result of PS ellagic acid binding to 5itd receptor (P27986) through the PI3k pathway.

Attempts |

Binding affinity |

RMSD refinement |

Mode |

1 |

-6.1004 |

1.1516 |

0 |

2 |

-6.0568 |

2.4477 |

0 |

3 |

-5.8439 |

1.1561 |

0 |

4 |

-5.8622 |

2.2106 |

0 |

5 |

-5.5509 |

2.9100 |

0 |

Mean |

-5.8468 |

1.9752 |

0 |

The molecular docking results, as tabulated, provide crucial insights into the binding interactions between the ligand and its target protein. The binding affinity values, measured in kcal/mol, represent the thermodynamic stability of the ligand-protein complex, with more negative values indicating stronger binding interactions. Across five repeated docking attempts, the binding affinity demonstrates a gradual decreasing trend, starting from-6.1004 kcal/mol in the first attempt and reducing to-5.5509 kcal/mol in the fifth. This decline suggests that while the ligand consistently maintains a relatively strong affinity for the target, there is variability in binding strength across different docking poses.

To further assess the reliability of these results, statistical analysis was applied to the dataset. The Standard Deviation (SD) of the binding affinity values provides an estimate of the variability between docking attempts. Given the mean binding affinity of-5.8468 kcal/mol, the standard deviation can be calculated to determine the dispersion of values around this mean. A low standard deviation would indicate that the binding affinities are relatively stable across multiple docking runs, while a higher standard deviation suggests greater variability in ligand-protein interactions. Similarly, the Root mean Square Deviation (RMSD) refinement values offer additional insights into the stability of the ligand’s binding conformation. The lower the RMSD value, the more stable the ligand’s conformation at the binding site. The first and third docking attempts exhibit relatively low RMSD values (1.1516 Å and 1.1561 Å, respectively), suggesting that the ligand maintains a stable conformation in these poses. However, the second, fourth, and fifth docking attempts show increasing RMSD values, with the highest reaching 2.9100 Å. The mean RMSD value of 1.9752 Å, along with its standard deviation, indicates the extent of fluctuation in ligand positioning. A high standard deviation in RMSD values would suggest significant conformational variation across different docking poses, potentially reflecting dynamic binding behaviour. The mode parameter remains consistently at zero across all docking attempts, indicating that the ligand binds in a single binding mode without significant variations. This consistency suggests that despite minor fluctuations in binding affinity and RMSD, the ligand exhibits a preferred binding conformation, reinforcing the reliability of the docking predictions.

By incorporating statistical analyses, such as standard deviation, these docking results gain enhanced interpretability. The standard deviation of binding affinity and RMSD values can provide deeper insights into the robustness of the docking study. A low standard deviation would indicate reproducibility and reliability, while a higher standard deviation may highlight potential binding flexibility or instability. Overall, while the ligand demonstrates a consistent and favourable binding affinity with the target protein, the observed RMSD fluctuations suggest that the stability of the ligand-protein interaction is not uniform across all docking attempts. Further molecular dynamics simulations and additional statistical evaluations would be beneficial to confirm the most stable and biologically relevant binding conformation.

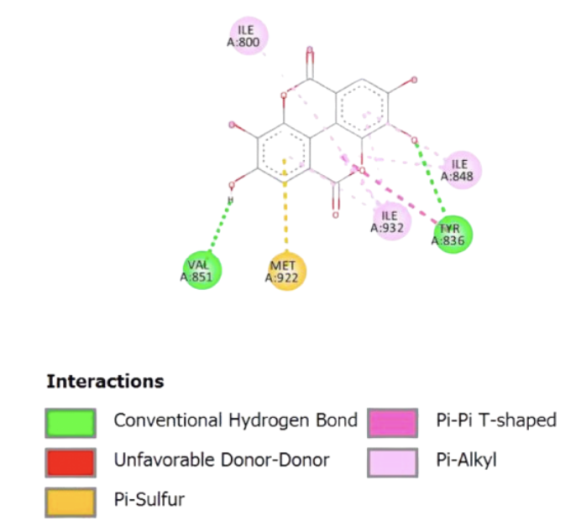

Fig. 1: Visualisation of PS ellagic acid binding to 5itd receptor. Different colors and lines indicate the formation of the type of bond between the test compound and the enzyme peptide. Dark green indicates the formation of a van der Waals bond, pink indicates the formation of pi--alkyl bonds, red indicates the formation of an unfavorable bump bond, yellow indicates the formation of pi–sulphur bonds, magenta indicates the formation of a pi–pi bond

Visualisation test results

The molecular interaction diagram illustrates the binding profile of the ligand within the active site of the target protein, highlighting the key interactions that stabilise the ligand-protein complex. The presence of conventional hydrogen bonds (depicted in green) with residues such as VAL851 and TYR836 suggests strong and specific interactions that contribute to the ligand’s affinity. Hydrogen bonds play a crucial role in ligand binding by enhancing specificity and stabilisation within the active site.

Furthermore, pi-sulphur interactions (yellow) are observed with MET922, indicating a stabilising interaction between the aromatic system of the ligand and the sulfur-containing side chain of methionine. This interaction can enhance binding affinity, particularly in environments where sulphur-mediated stabilisation is favoured. The presence of pi-pi T-shaped interactions (pink) and pi-alkyl interactions (light purple) with ILE800, ILE848, and ILE932 suggests that the ligand engages in hydrophobic and stacking interactions with non-polar residues. Pi-pi stacking is particularly relevant in stabilising aromatic ligands within a hydrophobic pocket, which can influence the overall binding energy. Notably, no unfavourable donor-donor interactions (red) are observed, suggesting that the ligand does not experience significant steric or electronic repulsion within the binding site.

Overall, the interaction profile suggests that the ligand exhibits a well-balanced combination of hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions, and aromatic stacking, which collectively contribute to its binding stability. These insights are essential for understanding the ligand’s structure-activity relationship and can guide further optimisation in drug design to enhance affinity and selectivity for the target protein.

DISCUSSION

Cancer is a complex and multifaceted disease characterised by the uncontrolled and abnormal proliferation of cells [22]. Its risk factors encompass genetic predisposition, exposure to carcinogens, lifestyle behaviours, and specific infectious diseases. Cancer initiation often results from the transformation of proto-oncogenes into oncogenes [31]. Oncogenes, which arise from mutated proto-oncogenes, encode overactive proteins that drive oncogenic processes. Oral cancer remains a significant public health concern in Southeast Asia, particularly in Indonesia, where behavioural risk factors such as betel chewing, tobacco use, and alcohol consumption contribute to its prevalence [32–34].

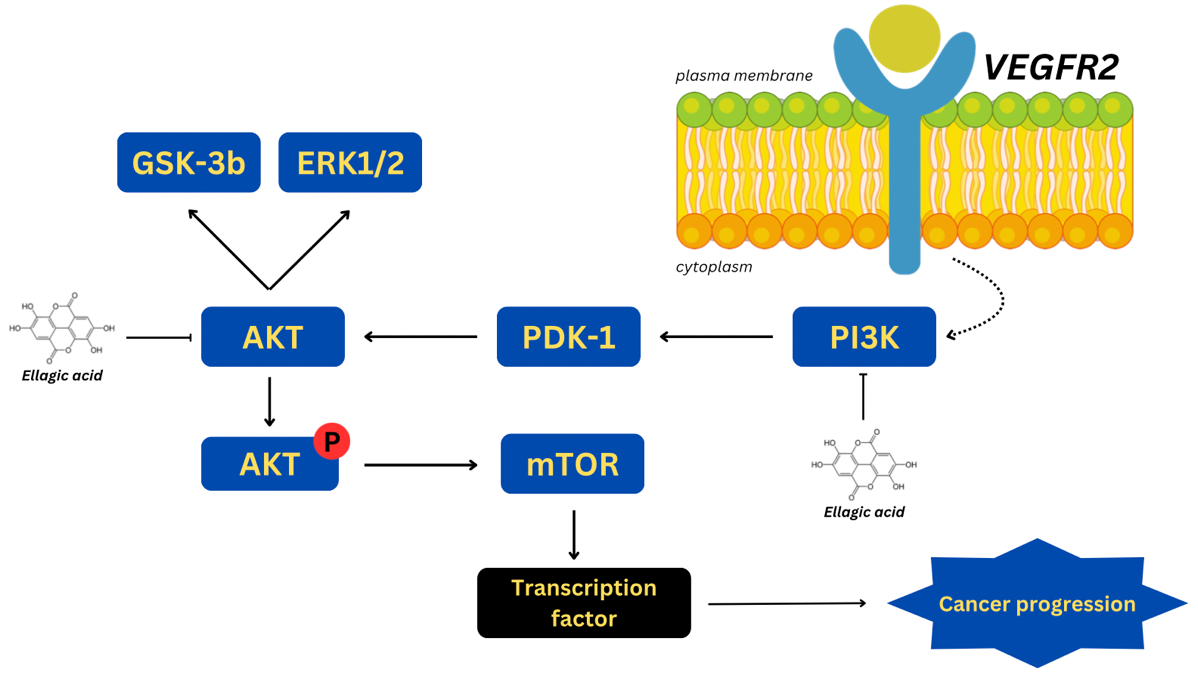

The PI3K pathway plays a pivotal role in oral cancer progression by regulating key cellular processes, including survival, proliferation, invasion, and migration. Notably, PI3K/AKT/mTOR signalling is a central driver of oncogenesis in OSCC, facilitating tumourigenesis and metastatic dissemination. A comprehensive understanding of this pathway provides insights into potential therapeutic targets and diagnostic markers. ATP stimulation has been shown to activate the PI3K/AKT pathway via the P2Y2-Src-EGFR axis, thereby enhancing malignancy by promoting cellular invasion and migration [26, 35–37]. Furthermore, the pathway plays a crucial role in apoptosis regulation, as evidenced by the action of compounds such as 11-epi-sinulariolide acetate, which inhibit PI3K/AKT activation, enabling FOXO proteins to promote apoptosis in oral cancer cells [27, 35]. Although invasive therapies do not directly target this pathway, their effects are closely intertwined with MAPK signalling and the cascading molecular events associated with oral cancer progression and malignancy [35].

Ellagic acid, a naturally occurring polyphenolic compound found in high concentrations in pomegranate species (PS), has emerged as a promising anticancer agent [17, 38]. Structurally, ellagic acid is a dilactone derivative of Hexahydroxydiphenic Acid (HHDP), a dimeric gallic acid derivative produced through ellagitannin hydrolysis. The compound exerts its anticancer effects through multiple mechanisms, including apoptosis induction, inhibition of proliferation, suppression of angiogenesis, and prevention of migration and metastasis, primarily through modulation of the PI3K pathway [38, 39]. Peng et al. (2020) demonstrated that pomegranate extract inhibits MMP-2/-9 activation, as well as cancer cell migration and invasion, by modulating AKT signalling in oral cancer cells [40]. The present study corroborates these findings through molecular docking and visualisation analyses, which demonstrate the stability and consistency of ellagic acid-binding. The docking attempts yielded high binding affinities ranging from-5.5509 to-6.1004 kcal/mol, with an associated error value (standard deviation) of 1.4037, which is well within the acceptable range (≤ 2 kcal/mol), thereby confirming the reliability of the results.

The mechanistic basis for ellagic acid's anticancer activity is further supported by its ability to modulate key oncogenic pathways, particularly through the inhibition of PI3K/AKT signalling. The compound effectively suppresses PI3K and Akt phosphorylation, leading to decreased proliferation and increased apoptosis in cancer cells. Moreover, ellagic acid downregulates critical oncogenic regulators, including PDK-1, mTOR, and HIF-1α, which are essential for tumour growth and angiogenesis [39–41]. Computational docking analyses reveal the compound's robust binding interactions, despite the presence of a single unfavourable bond. The docking studies provide strong evidence for ellagic acid’s capacity to significantly disrupt PI3K pathway signalling, as indicated by consistent binding affinities and a tolerated RMSD value of 1.9752.

Fig. 2: Modulation of PI3K/Akt pathway by ellagic acid

Beyond its molecular efficacy, ellagic acid demonstrates favourable pharmacokinetic and toxicological properties. According to Lipinski's Rule of Five (RO5), the compound satisfies key criteria for drug-likeness, including molecular mass, hydrogen bond donor/acceptor capacity, log P, and molar refractivity, suggesting high bioavailability and favourable pharmacodynamics. Additionally, ADMETlab 3.0 analyses further support its therapeutic potential by confirming excellent intestinal absorption, high human fraction unbound distribution, and appropriate metabolism through CYP2D6, ensuring efficient systemic clearance. The safety profile of ellagic acid is also favourable, as demonstrated in table 3, where its toxicity parameters, including AMES mutagenicity, hepatotoxicity, and skin sensitisation, are all within acceptable ranges. Moreover, human maximum tolerated dose and LOAEL chronic toxicity evaluations indicate that ellagic acid remains safe even at higher dosages, provided administration remains within the recommended thresholds.

While ellagic acid demonstrates significant anticancer potential, it is essential to compare its binding affinity with those of standard chemotherapeutic agents targeting the PI3K/AKT pathway, such as rapamycin, wortmannin, or PI3K inhibitors like BEZ235 [15,42–46]. Such comparisons would further elucidate ellagic acid’s relative potency and therapeutic viability. Additionally, the present findings provide a foundation for future experimental validation through in vitro and in vivo studies. Cell culture assays involving OSCC lines could evaluate its pro-apoptotic and anti-proliferative effects, while animal models could determine its efficacy in tumour regression and metastasis inhibition [47–50]. Pharmacokinetic studies assessing bioavailability, metabolism, and systemic clearance in vivo will also be crucial in determining its translational potential.

Despite promising findings, this study is limited by the inherent constraints of in silico modelling, which may not fully capture the complexity of biological systems. Computational docking and molecular simulations, while valuable for predicting interactions, cannot entirely account for dynamic cellular processes, metabolic stability, or bioavailability in physiological environments. Therefore, future research should focus on experimental validation through in vitro and in vivo studies, evaluating ellagic acid’s efficacy in clinical settings.

Furthermore, given that PI3K pathway inhibition is often associated with compensatory activation of alternative survival pathways such as MAPK and JAK/STAT, future investigations should assess potential resistance mechanisms and explore combination therapies. Investigating ellagic acid’s synergistic effects with existing chemotherapeutic agents could optimise its clinical application, potentially enhancing efficacy while reducing toxicity.

CONCLUSION

The in silico evaluation underscores the promising potential of pomegranate seed–derived ellagic acid as an anticancer agent against oral cancer. Its strong affinity for the PI3K/AKT pathway effectively disrupts key oncogenic processes, including tumour survival, cellular proliferation, and inflammation. Moreover, its favourable pharmacokinetic profile-characterized by excellent biocompatibility, low toxicity, and high intestinal absorption- reinforces its viability as a safe and effective therapeutic candidate. These findings provide a solid foundation for further exploration into the clinical applications of ellagic acid. To translate these computational insights into tangible medical advancements, future research should focus on rigorous in vitro and in vivo validation. Cell culture studies using OSCC models should be conducted to assess its apoptotic and anti-proliferative effects, while animal studies should evaluate its pharmacokinetics, bioavailability, and systemic efficacy in tumour suppression. Additionally, clinical trials will be necessary to establish optimal dosage, safety margins, and potential side effects in human subjects. Beyond monotherapy, combination therapy strategies should be explored to enhance ellagic acid’s therapeutic efficacy. Given the compensatory activation of alternative survival pathways such as MAPK and JAK/STAT in response to PI3K inhibition, investigating synergistic effects with standard chemotherapeutic agents or targeted inhibitors could optimize treatment outcomes while minimizing toxicity. Furthermore, advancements in drug delivery syste.ms-such as nanoformulations, liposomal carriers, and targeted delivery mechanisms should be considered to enhance ellagic acid’s solubility, stability, and bioavailability. Such innovations could improve its therapeutic potential and facilitate its clinical transition. In conclusion, while this study provides compelling preliminary evidence for ellagic acid’s role in oral cancer therapy, its full therapeutic potential can only be realized through comprehensive preclinical and clinical investigations. A multidisciplinary approach integrating computational modeling, pharmacological research, and translational medicine will be essential in advancing ellagic acid towards clinical application as a viable anticancer agent.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to everyone who contributed to the completion of this study on the pomegranate seed ellagic acid prospect as oral cancer therapy. First and foremost, we would like to extend our appreciation to the Dental Medicine Faculty of Airlangga University for providing the necessary resources and facilities that enabled us to conduct our experiments. Additionally, we are grateful to our peers and colleagues who provided insights and feedback during the development of this article. Their constructive criticism helped improve the quality of our work. Finally, we would like to acknowledge our families and friends for their unwavering support and encouragement, which motivated us to complete this study.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

BL formulated the research idea, designed the study framework, and supervised the entire research process. He provided intellectual guidance and ensured the study’s alignment with relevant scientific methodologies and objectives. PAML was responsible for conducting the in silico simulations, including molecular docking, pharmacokinetic modeling, and ADMET predictions. She also handled data processing, statistical analysis, and visualization of results. KDW contributed to data validation and cross-verification of the computational findings. She played a key role in interpreting the docking outcomes, binding affinities, and pharmacokinetic properties, ensuring scientific accuracy. AACD prepared the manuscript, including the introduction, methodology, results, and discussion sections. He structured the content, integrated relevant literature, and ensured logical coherence in presenting findings. FYM critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for technical accuracy, clarity, and coherence. They also contributed to refining the discussion and conclusion. Additionally, they facilitated funding acquisition and ensured compliance with ethical and institutional research guidelines. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTS

Authors declare no conflict of interest(s)

REFERENCES

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209-49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660, PMID 33538338.

Pinto Silva JF. Early oral cancer diagnosis: secondary prevention in the form of opportunistic screening or organized screening. Gaz Med. 2021;8(2).

Zhang SZ, Xie L, Shang ZJ. Burden of oral cancer on the 10 most populous countries from 1990 to 2019: estimates from the global burden of disease study 2019. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(2):875. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19020875, PMID 35055693.

Chung CH, HU TH, Wang JD, Hwang JS. Estimation of quality adjusted life expectancy of patients with oral cancer: integration of lifetime survival with repeated quality of life measurements. Value Health Reg Issues. 2020;21:59-65. doi: 10.1016/j.vhri.2019.07.005, PMID 31655464.

Xie L, Shang Z. Burden of oral cancer in Asia from 1990 to 2019: estimates from the global burden of disease 2019 study. Plos One. 2022;17(3):e0265950. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0265950, PMID 35324990.

Chaudhary M. Missing the woods for the trees. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2023;27(1):4-5. doi: 10.4103/jomfp.jomfp_89_23, PMID 37234295.

Mohamad I, Glaun MD, Prabhash K, Busheri A, Lai SY, Noronha V. Current treatment strategies and risk stratification for oral carcinoma. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2023;43:e389810. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_389810, PMID 37200591.

Problems after mouth and oropharyngeal cancer surgery; 2024. Available from: https://www.cancerresearchuk.cancerresearchuk.orgorg/aboutcancer/mouthcancer/treatment/surgery/possible-problems.

Oral complications of cancer therapies. Cancer; 2024. Available from: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/side-effects/mouth-throat/oral-complications-pdq.Gov. [Last accessed on 13 Feb 2025].

Sroussi HY, Epstein JB, Bensadoun RJ, Saunders DP, Lalla RV, Migliorati CA. Common oral complications of head and neck cancer radiation therapy: mucositis infections saliva change fibrosis, sensory dysfunctions dental caries periodontal disease and osteoradionecrosis. Cancer Med. 2017 Oct 25;6(12):2918-31. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1221, PMID 29071801.

Huang YC, Sung MY, Lin TK, Kuo CY, Hsu YC. Chinese herbal medicine compound of flavonoids adjunctive treatment for oral cancer. J Formos Med Assoc. 2024 Aug;123(8):830-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2023.10.009, PMID 37919197.

Imanu SF, Leginis SN, Iqbal M, Surboyo MD. Pomegranate extract mechanism in inhibiting the development of oral cancer: a review. Indonesian J Dent Med. 2023;6(1):37-42. doi: 10.20473/ijdm.v6i1.2023.37-42.

Wang J, Sun M, YU J, Wang J, Cui Q. Pomegranate seeds: a comprehensive review of traditional uses chemical composition and pharmacological properties. Front Pharmacol. 2024;15:1401826. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2024.1401826, PMID 39055489.

Wang F, Chen J, Xiang D, Lian X, WU C, Quan J. Ellagic acid inhibits cell proliferation migration and invasion in melanoma via EGFR pathway. Am J Transl Res. 2020;12(5):2295-304. PMID 32509220.

Cizmarikova M, Michalkova R, Mirossay L, Mojzisova G, Zigova M, Bardelcikova A. Ellagic acid and cancer hallmarks: insights from experimental evidence. Biomolecules. 2023 Nov 1;13(11):1653. doi: 10.3390/biom13111653, PMID 38002335.

Yang Y, Liu C, Tang SS, GU D, Tian J, Huang D. Ellagic acid from pomegranate peel: consecutive countercurrent chromatographic separation and antioxidant effect. Biomed Chromatogr. 2023;37(9):e5662.13.

Sharifi Rad J, Quispe C, Castillo CM, Caroca R, Lazo Velez MA, Antonyak H. Ellagic acid: a review on its natural sources chemical stability and therapeutic potential. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022;2022:3848084. doi: 10.1155/2022/3848084, PMID 35237379.

Chemcomp. Molecular operating environment (MOE) | MOEsaic. PSILO; 2025. Available from: https://www.chemcomp.Com/Products. [Last accessed on 13 Feb 2025].

Chen X, LI H, Tian L, LI Q, Luo J, Zhang Y. Analysis of the physicochemical properties of acaricides based on lipinski’s rule of five. J Comput Biol. 2020;27(9):1397-406. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2019.0323, PMID 32031890.

Dulsat J, Lopez Nieto B, Estrada Tejedor R, Borrell JI. Evaluation of free online ADMET tools for academic or small biotech environments. Molecules. 2023 Jan 1;28(2):776. doi: 10.3390/molecules28020776, PMID 36677832.

Ferreira LL, Andricopulo AD. ADMET modeling approaches in drug discovery. Drug Discov Today. 2019;24(5):1157-65. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2019.03.015, PMID 30890362.

Rim KT. In silico prediction of toxicity and its applications for chemicals at work. Toxicol Environ Health Sci. 2020;12(3):191-202. doi: 10.1007/s13530-020-00056-4, PMID 32421081.

FU L, Shi S, YI J, Wang N, HE Y, WU Z. ADMET lab 3.0: an updated comprehensive online ADMET prediction platform enhanced with broader coverage improved performance API functionality and decision support. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024 Apr 4;52(W1):W422-31. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkae236, PMID 38572755.

JI D, XU M, Udenigwe CC, Agyei D. Physicochemical characterisation molecular docking and drug likeness evaluation of hypotensive peptides encrypted in flaxseed proteome. Curr Res Food Sci. 2020;3:41-50. doi: 10.1016/j.crfs.2020.03.001, PMID 32914119.

Burley SK, Bhikadiya C, Bi C, Bittrich S, Chao H, Chen L. RCSB protein data bank: tools for visualizing and understanding biological macromolecules in 3D. Protein Sci. 2022;31(12):e4482. doi: 10.1002/pro.4482, PMID 36281733.

Pantsar T, Poso A. Binding affinity via docking: fact and fiction. Molecules. 2018;23(8):1899. doi: 10.3390/molecules23081899, PMID 30061498.

Cristiane H. Squarize FS. The determinants of head and neck cancer: unmasking the PI3K pathway mutations. J Carcinog Mutagen. 2013. doi: 10.4172/2157-2518.S5-003.

Hamad AW, Al Momani WM, Janakat S, Oran SA. Bioavailability of ellagic acid after single dose administration using HPLC. Pak J Nutr. 2009 Sep 15;8(10):1661-4. doi: 10.3923/pjn.2009.1661.1664.

Seeram NP, Lee R, Heber D. Bioavailability of ellagic acid in human plasma after consumption of ellagitannins from pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) juice. Clin Chim Acta. 2004 Oct;348(1-2):63-8. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2004.04.029, PMID 15369737.

Zuccari G, Baldassari S, Ailuno G, Turrini F, Alfei S, Caviglioli G. Formulation strategies to improve oral bioavailability of ellagic acid. Appl Sci. 2020 May 12;10(10):3353. doi: 10.3390/app10103353.

Hernawati S, Irmawati A. The efficacy of pomegranate extract (Punica granatum l.) and ellagic acid on the expression of VEGF and oral cancer cells apoptosis of mus musculus due to benzopyrene induction. Pollut Res. 2019;38:S206-10.

Kumar M, Nanavati R, Modi TG, Dobariya C. Oral cancer: etiology and risk factors: a review. J Cancer Res Ther. 2016;12(2):458-63. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.186696, PMID 27461593.

Cheng Y, Chen J, Shi Y, Fang X, Tang Z. MAPK signaling pathway in oral squamous cell carcinoma: biological function and targeted therapy. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(19):4625. doi: 10.3390/cancers14194625, PMID 36230547.

Alkhatib DZ, Thi Kim Truong T, Fujii S, Hasegawa K, Nagano R, Tajiri Y, Kiyoshima T. Stepwise activation of p63 and the MEK/ERK pathway induces the expression of ARL4C to promote oral squamous cell carcinoma cell proliferation. Pathol Res Pract. 2023 Jun;246:154493.

Kumari M, Chhikara BS, Singh P, Rathi B. Signaling and molecular pathways implicated in oral cancer: a concise review. CBL. 2024;11(1). doi: 10.62110/sciencein.cbl.2024.v11.652.

Jiang Q, Xiao J, Hsieh YC, Kumar NL, Han L, Zou Y. The role of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR axis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Biomedicines. 2024;12(7):1610. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines12071610, PMID 39062182.

Zhou Q, Liu S, Kou Y, Yang P, Liu H, Hasegawa T. ATP promotes oral squamous cell carcinoma cell invasion and migration by activating the PI3K/AKT pathway via the P2Y2-Src-EGFR axis. ACS Omega. 2022;7(44):39760-71. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.2c03727, PMID 36385800.

Chang TS, Lin JJ, Cheng KC, SU JH, She YY, WU YJ. 11-epi-sinulariolide acetate-induced apoptosis in oral cancer cells is regulated by FOXO through inhibition of PI3K/AKT pathway. Anticancer Res. 2023 Jun;43(6):2625-34. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.16429, PMID 37247910.

Kowshik J, Giri H, Kranthi Kiran Kishore T, Kesavan R, Naik V, Ankudavath R, Bhanuprakash Reddy G, Nagini S. Ellagic acid inhibits VEGF/VEGFR2, PI3K/Akt and MAPK signaling cascades in the hamster cheek pouch carcinogenesis model. Anti-Cancer Agents Med Chem. 2014;14(9):1249-60. doi: 10.2174/1871520614666140723114217.

Peng SY, Hsiao CC, Lan TH, Yen CY, Farooqi AA, Cheng CM. Pomegranate extract inhibits migration and invasion of oral cancer cells by downregulating matrix metalloproteinase-2/9 and epithelial mesenchymal transition. Environ Toxicol. 2020;35(6):673-82. doi: 10.1002/tox.22903, PMID 31995279.

Liu Q, Liang X, Niu C, Wang X. Ellagic acid promotes A549 cell apoptosis via regulating the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B pathway. Exp Ther Med. 2018;16(1):347-52. doi: 10.3892/etm.2018.6193, PMID 29896260.

Ceci C, Lacal PM, Tentori L, DE Martino MG, Miano R, Graziani G. Experimental evidence of the antitumor antimetastatic and antiangiogenic activity of ellagic acid. Nutrients. 2018 Nov 14;10(11):1756. doi: 10.3390/nu10111756, PMID 30441769.

Cho DC, Cohen MB, Panka DJ, Collins MJ, Ghebremichael M, Atkins MB. The efficacy of the novel dual PI3-kinase/mTOR inhibitor NVP-BEZ235 compared with rapamycin in renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2010 Jul 15;16(14):3628-38. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3022, PMID 20606035.

Karar J, Cerniglia GJ, Lindsten T, Koumenis C, Maity A. Dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitor NVP-BEZ235 suppresses hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)-1α expression by blocking protein translation and increases cell death under hypoxia. Cancer Biol Ther. 2012 Sep;13(11):1102-11. doi: 10.4161/cbt.21144, PMID 22895065.

LI B, Zhang X, Ren Q, Gao L, Tian J. NVP-BEZ235 inhibits renal cell carcinoma by targeting TAK1 and PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathways. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:781623. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.781623, PMID 35082669.

Suzuki Y, Enokido Y, Yamada K, Inaba M, Kuwata K, Hanada N. The effect of rapamycin NVP-BEZ235 aspirin and metformin on PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway of PIK3CA-related overgrowth spectrum (PROS). Oncotarget. 2017 May 2;8(28):45470-83. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17566, PMID 28525374.

Mady FM, Shaker MA. Enhanced anticancer activity and oral bioavailability of ellagic acid through encapsulation in biodegradable polymeric nanoparticles. Int J Nanomedicine. 2017 Oct;12:7405-17. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S147740, PMID 29066891.

Maria P, Hellmeister LR, Teixeira LN, Junior, Martinez EF. Ellagic acid cytotoxic and metalloproteinases inhibitory effects against oral squamous cell carcinoma: an in vitro study; 2021.

Mohammadinejad A, Mohajeri T, Aleyaghoob G, Heidarian F, Kazemi Oskuee R. Ellagic acid as a potent anticancer drug: a comprehensive review on in vitro, in vivo, in silico and drug delivery studies. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 2022;69(6):2323-56. doi: 10.1002/bab.2288, PMID 34846078.

Wang D, Chen Q, Tan Y, Liu B, Liu C. Ellagic acid inhibits human glioblastoma growth in vitro and in vivo. Oncol Rep. 2017;37(2):1084-92. doi: 10.3892/or.2016.5331, PMID 28035411.

10

10 5

5