Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 5, 2025, 528-533Original Article

PLASMA CONCENTRATION OF CURCUMIN AND SELENIUM FOLLOWING ADMINISTRATION OF SLOW-RELEASE CURCUMIN-LOADED SELENIUM NANOPARTICLES

JAHANGIR KABOUTARI1, FATEMEH SABAGHI1, DHIYA ALTEMEMY2, HOSEIN ALI ARAB3, MOOSE JAVDAI4, PEGAH KHOSRAVIYAN5*

1Department of Basic Sciences, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Shahrekord University, Shahrekord, Iran. 2Department of Pharmaceutics, College of Pharmacy, Al-Zahraa University for Women, Karbala, Iraq. 3Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Tehran University, Tehran, Iran. 4Department of Clinical Sciences, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Shahrekord University, Shahrekord, Iran. 5Medical Plants Research Center, Basic Health Sciences Institute, Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences, Shahrekord, Iran

*Corresponding author: Pegah Khosraviyan; *Email: pegah.khosraviyan@gmail.com

Received: 28 Dec 2024, Revised and Accepted: 24 Jun 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: Suitable plasma concentration at the site of action is a crucial therapeutic goal, so slow-release pharmaceutical dosage forms have been very effective. This study planned to investigate the plasma concentrations of curcumin (Cur) and selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) following the administration of a slow-release system of SeNPs loaded with Cur (SeNPs@Cur).

Methods: 75 adult male rats were randomly divided into five groups. The control group received no treatment. In other groups, a single dose of 5 ml of 10% ethanol (solvent group), 0.25 mg/kg SeNPs, 50 mg/kg Cur, and 0.25 mg/kg SeNPs loaded with 50 mg/kg Cur (SeNPs@Cur) were administered intraperitoneally. Blood samples were taken on days 1, 3, and 5, and blood concentrations of SeNPs and Cur were measured by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES) and High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), respectively.

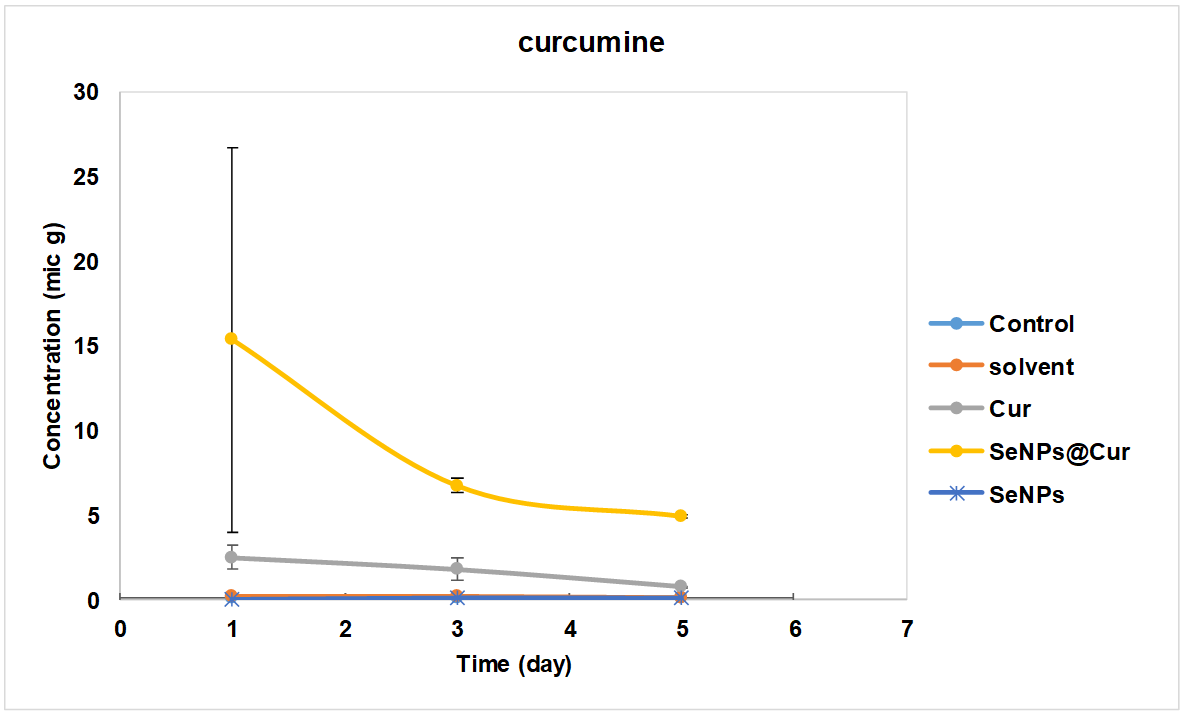

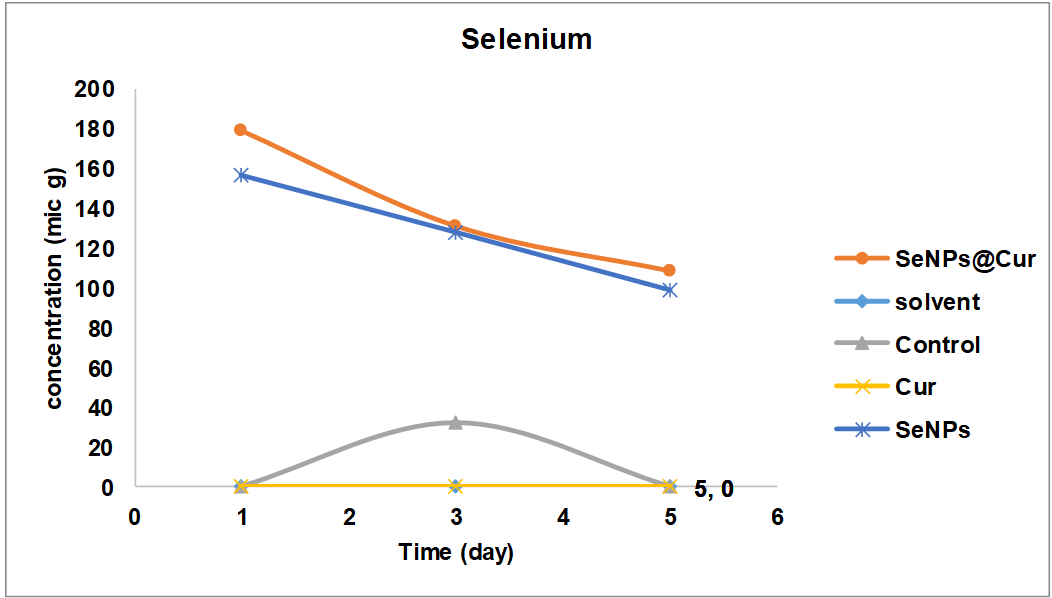

Results: The concentration of Cur in the Cur group was less than five µg on day 1 and gradually decreased over 5 d to zero. The blood concentration of Cur was approximately 15 µg on day 1 in the SeNPs@Cur group, then decreased until the 3rd day, and finally remained at a constant level of 5 µg on the 5th d. Selenium concentration decreased in the SeNPs group, from 160 µg on day 1 to 100 µg on day 5. Selenium concentration in the SeNPs@Cur group was 180 µg on the first day, then decreased to 110 µg on the fifth day. SeNPs@Cur maintained a plasma curcumin level of 5 µg on day 5 compared to undetectable levels in the Cur group.

Conclusion: This study showed that the intraperitoneal administration of SeNPs@Cur, compared to the administration of free Cur, initially causes a high serum concentration and a loading dose, which continues with the slow release, increasing and maintaining the Cur serum level in the long-term treatment period.

Keywords: Curcumin, Selenium nanoparticles, Slow release, Plasma concentration

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i5.53543 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Cur is the active component of Curcuma longa, or turmeric and accounts for about 2–8% of the chemical ingredients of turmeric. It is responsible for its characteristic yellow and golden hue and many other properties [1, 2]. It performs a variety of pharmacological activities with little intrinsic toxicity, including antioxidant, anti-lipid peroxidation, free radical scavenging, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, anti-cancer, hypolipidemia, hypocholesteremia, hepatoprotective, inhibiting lipoxygenase, cyclooxygenase, and protease enzymes, anti-platelet aggregation, and digestant by the choleretic effect [3, 4]. Due to Cur's low aqueous solubility, quick absorption, biotransformation, and overall clearance in the body, it has a short retention period in blood circulation [2]. In animal studies, curcumin undergoes rapid metabolic reduction and conjugation, resulting in poor systemic bioavailability after oral administration [5]. Therefore, the majority of work on Cur and its potential medical applications has focused on enhancing Cur's physiological solubility, general absorption, and biological durability in the body, such as through applying novel pharmaceutical delivery systems [6, 7].

Over the years, numerous curcumin drug targets have been described, providing the molecular basis for the pharmacological action. Unfortunately, the bioavailability and delivery of curcumin are the main obstacles to its effectiveness, precluding its use in medicine. Tabanelli et al. have explored the most promising and modern strategies for improving curcumin bioavailability, offering a comprehensive overview of this field. The progress in the nanoparticle field could provide, in the near future, further curcumin-based complexes with significant pharmacological profiles that can be developed as effective therapeutic agents for treating human diseases. The advancement in this field holds great promise to employ this polyphenol in medicine [8, 9].

Selenium is one of the microelements that play essential roles, especially for vertebrates, such as participating in the selenoprotein structure, including glutathione peroxidase, phospholipid hydroxylase, and thioredoxin. It has a wide range of functions, such as anti-cancer, anti-viral, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory activity and the reduction of oxidative stress induced by reactive oxygen species [10-12]. Both organic and inorganic forms of selenium have different antioxidant effects. SeNPs have a higher median lethal dose (LD50), fewer side effects, greater antioxidant efficiency, enhanced bioavailability, and increased blood shelf life compared to other forms of selenium [13]. SeNPs increase the efficiency of serum glutathione peroxidase, superoxide dismutase, thyroxine reductase, and hepatic glutathione S-transferase, increase antioxidant activity, and subsequently reduce the production of malondialdehyde in comparison to selenium [14].

Based on the above evidence, we speculated that a combination of Selenium and curcumin might exhibit enhanced anticancer efficacy due to the simultaneous targeting of multiple cellular targets and the synergistic benefits or targeted applications (e. g., anti-inflammatory or antioxidant purposes) [15].

Achieving the appropriate concentration of the drug at the site of the action during the treatment period is an ideal therapeutic goal in treatment. Therefore, the supply of slow-release pharmacological formulations is one of the unique approaches. Slow-release systems are intended to achieve a uniform drug plasma concentration during the therapeutic period. This results in a significant reduction in drug doses and side effects, a reduction in fluctuations in blood drug concentrations, an increase in therapeutic functions, and a decrease in treatment costs [6, 16]. This study examines the blood levels of Cur and SeNPs following the administration of SeNPs@Cur.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Selenium oxide, ascorbic acid, Cur and other reagents and solvents were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Hesse, Germany).

Preparation and characterization of SeNPs and SeNPs@Cur

The SeNPs and SeNPs@Cur synthesis and their characterization were done in a previous study [17]. 50 ml of a 44 mmol ascorbic acid solution (Merck, Germany) was added dropwise to the 500 ml aqueous solution of 1 mmol selenium oxide (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) to form S. N. For curcumin loading on the S. N, 10 mg of curcumin (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) dissolved in 5 ml of acetone (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was added to 150 ml of S. N, stirred, and mixed carefully for 24 h in the fridge (After that, evaluation of the resulting nanoparticles’ characteristics as particle size distribution, surface charge, loading efficiency, etc., was done as in the previous study [17].

Animal experiments

By international standards, 75 adult male rats weighing 200-250 g were kept in metal cages with free access to clean, fresh water and rat pellet food under standard circumstances of 22 °C, relative humidity of 55-56%, 12 h light/dark cycle. Animals were sorted into five groups at random after environmental adaptation. Only normal saline with 10% ethanol was administered to the solvent group. In other groups, 0.25 mg/kg of SeNPs, 50 mg/kg of Cur, and 0.25 mg/kg SeNPs loaded with 50 mg/kg of Cur (SeNPs@Cur) were administered intraperitoneally [18]. The control group didn't get any treatment. The blood samples were taken on days 1, 3, and 5 from 15 mice in each group (each time 5 mice). The animals in each group were euthanized with 150 mg/kg of sodium pentobarbital (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) intraperitoneal administration, and the blood sample was taken by heart puncture for further analysis. All investigational procedures used in this study were reviewed and approved by approved by the institutional ethical committee (IR. SKUMS. AEC.1401.011).

HPLC analysis

Cur extraction was carried out using McEwan's buffer solution. 372 g of Na2EDTA, 12.9 g of citric acid, and 28 g of disodium sulfate were combined. 800 ml of deionized distilled water was added to the prepared mixture. Then, after, 0.1 M phosphoric acid was used to adjust the compound's pH to 4. In the end, distilled water was used to dilute the resulting mixture. 600 µl of serum and 100 µl of McEwan's buffer were added to the test tube and gently mixed with a stirrer. Then, it was held for 30 min in a hot water bath at 40 °C. The supernatant was then taken and placed into another tube after the tubes had been centrifuged for 30 min at 3000 rpm. Following this procedure, 5 ml of methanol was added to each tube, gently mixed, and then filtered through a microfilter. For HPLC detection, several dilutions of the pure standards of the Cur were made in the mobile phase solvent. These dilutions ranged from 2, 20, 100, 200, 2000, and 20,000 g/ml. The mobile phase comprised 30% deionized distilled water and 70% acetonitrile. The lowest concentration of the standard solution, 20 µl, was injected into the HPLC system, and the sample's retention time was determined. The optimal temperature and flow rate were found at 37 °C and 1 ml/min, respectively. Additionally, the ideal sample retention was measured at 420 nm.

Selenium measurement using an ICP device

Two ml of each sample was added to a 6:2 v/v solution of nitric acid and hydrogen peroxide for wet digestion. The mixture was heated to 85 °C, left to dry, and then purified by stable acid-purified microfilters. It was then dissolved in a solution of nitric acid and hydrogen peroxide and diluted to a volume of 10 ml using double-deionized water.

The control and calibration standard solutions were prepared from a single element of selenium (blank). The control standard was made by combining 2 ml of nitric acid with 100 ml of twice-deionized water. The ICP-OES system was employed to measure selenium quantitatively. By spiking the serum samples, it was possible to determine the recovery rates of the samples tested and validate how well the device worked.

Statistical analysis

The results were expressed as mean±SD, and the ANOVA test was used. Differences were considered significant at P<0.05. All statistics were conducted using Microsoft Office Excel 2019 for Windows.

RESULTS

Cur standard curve using HPLC

First of all, the result of the synthesis and characterization of The SeNPs and SeNPs@Cur were showed in a previous study [17].

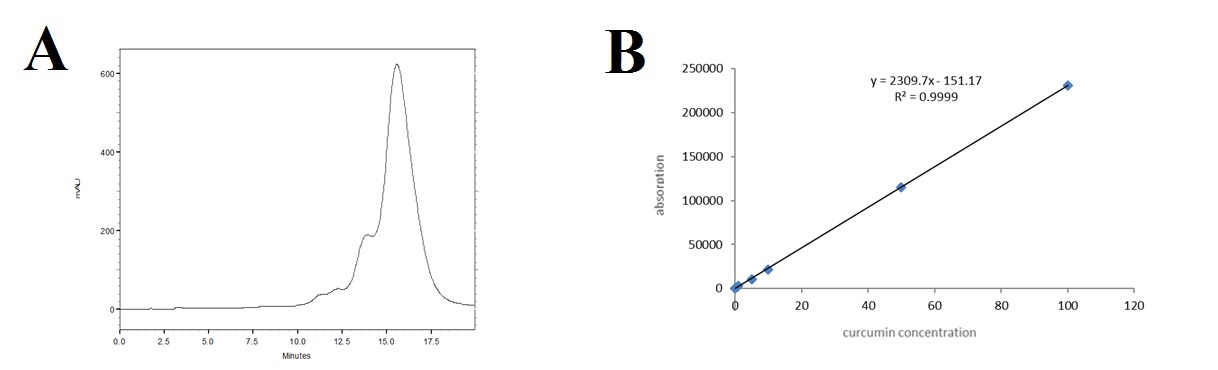

The peak of Cur was seen at about 15.5 min (fig. 1A). The standard curve (fig. 1B) obtained using HPLC was linear (R² = 0.9999) in the concentration range of 0.5-100 ppm.

Fig. 1: A) Spectrum of Cur by HPLC, B) Standard curve of Cur by HPLC

Selenium standard curve using ICP

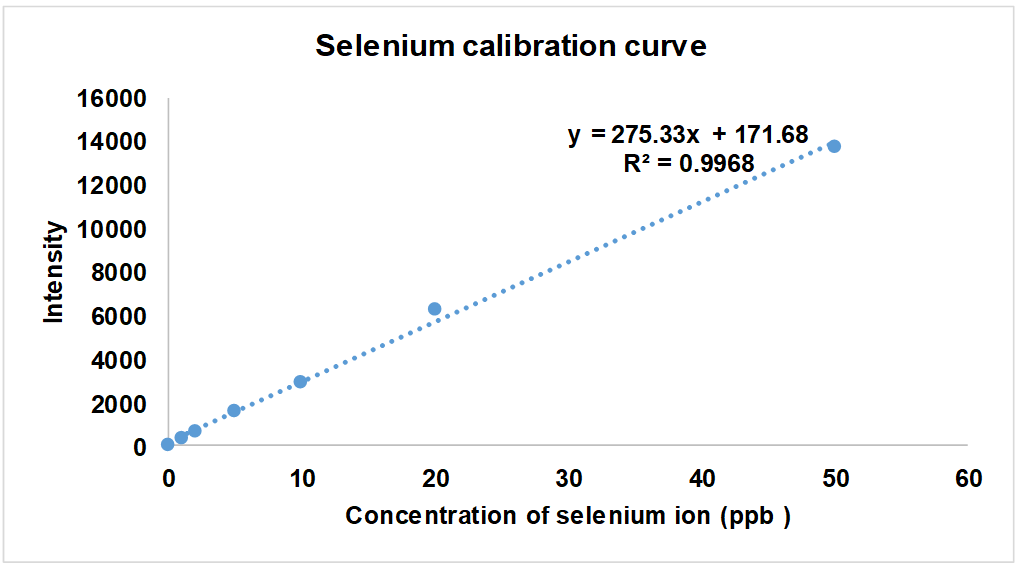

The standard curve for selenium (fig. 2) obtained using ICP was linear (R² = 0.9968) in the concentration range of 50 to 1 ppm.

Cur release in blood

Examining the Cur release in the blood, which is given in fig. 3, it can be seen that in the group that received only Cur, its amount decreased slowly until it reached zero on the fifth day. The initial amount of Cur in the SeNPs@Cur group was much higher on the first day, and after a sudden decrease until the third day, its amount reached relative stability from the third day to the fifth day.

Selenium release in blood

The selenium release in the blood is shown in fig. 4. The amount of released selenium in the control group decreases after a small increase until the third day and reaches zero on the fifth day. The amount of selenium in the SeNPs group increased from 160 µg on the first day to 100 µg on the fifth day. In the SeNPs@Cur group, the initial amount of selenium was higher (180 µg), and then it slowly decreased until, on the third to fifth day, its amount remained relatively constant.

Fig. 2: Standard curve of selenium by ICP

Fig. 3: Amount of released cur in blood

Fig. 4: Amount of released selenium in blood

Pharmacokinetics of cur and selenium

The pharmacokinetic parameters of Cur and selenium were measured based on the equations given in the work method [17], and the results are shown in Tables 2 and 3. As can be seen, the half-life in both Cur and SeNPs groups was 48 h, which is more than the SeNPs@Cur group. The clearance constant (Kel) in the Cur group (0.0144) is much lower than the SeNPs@Cur group (0.023). Regarding the volume of distribution (𝑉𝑑) and clearance time (Cl), it was also seen that its amount was significantly higher in the Cur and SeNPs group than in the SeNPs@Cur group.

Table 2: Pharmacokinetic parameters of cur

| 𝑉𝑑 (ml) | Cl total (ml/h) | AUC 0-∞ (micg. h/ml) | AUC 0-𝑡 (micg. h/ml) | 𝑘el (1/h) | 𝑡(1/2) (h) | Group |

| 2463.9 | 35.48 | 0.3523 | 304.3 | 0.0144 | 48 | Cur |

| 445.9 | 10.658 | 1.1729 | 968.7 | 0.0239 | 29 | SeNPs@Cur |

Pharmacokinetic parameters, t1/2: The time required for the concentration of the drug to reach half of its original value, 𝑘el: The rate of drug eliminated per unit of time, AUC 0-𝑡: the area under the concentration-time curve from dosing (time 0) to time t, AUC 0-∞: the area under the concentration-time curve from dosing (time 0) to infinite time, Cl total: The volume of plasma (blood) completely cleared of drugs per hour, 𝑉𝑑: the volume of distribution, values are mean, n=3.

Table 3: Pharmacokinetic parameters of selenium

| 𝑉𝑑 (ml) | Cl total (ml/h) | AUC 0-∞ (micg. h/ml) | AUC 0-𝑡 (micg. h/ml) | 𝑘el (1/h) | 𝑡(1/2) (h) | Group |

| 0.0227 | 0.00327 | 19094 | 12240 | 0.0144 | 48 | SeNPs |

| 0.175 | 0.00316 | 19761 | 13728 | 0.018 | 38.5 | SeNPs@Cur |

Pharmacokinetic parameters, t1/2: The time required for the concentration of the drug to reach half of its original value, 𝑘el: The rate of drug eliminated per unit time, AUC 0-𝑡: the area under the concentration-time curve from dosing (time 0) to time t, AUC 0-∞: the area under the concentration-time curve from dosing (time 0) to infinite time, Cl total: The volume of plasma (blood) completely cleared of drug per hour, 𝑉𝑑: the volume of distribution, values are mean, n=3.

DISCUSSION

Cur is one of the compounds with low bioavailability after oral use due to first-pass metabolism with hepatic metabolism, especially glucuronidation and sulfation [19].

In this study, the amount of Cur released into the blood showed that in the Cur group, the blood level of this substance was less than five µg 24 h after administration, which indicates its low half-life in the body. This small amount also slowly decreases until it reaches zero on the fifth day, consistent with some previous research on this matter.

In a 1997 study on rats, after oral administration of 1 g/kg of Cur, very small amounts of Cur were seen in the blood plasma, and the level slowly decreased until it reached zero on the fourth day [20].

Shoba et al. (1998) reported that the simultaneous use of Cur with 1-properly piperidine (the alkaline substance of pepper) as an oral administration in the rats caused the stimulation of glucuronyl transferase enzymes, and this transformation increased the bioavailability (154%) of Cur [21].

Hong et al. (2004) found high plasma levels of curcumin glucuronide and curcumin sulfate, small amounts of hexahydrocurcumin, hexahydrocurcumin-inol, and hexahydrocurcumin glucuronide, and very small amounts of curcumin, although due to low bioavailability, the amount of these substances decreased sharply by the second day [22]. However, this research showed that the level of Cur in the blood in the SeNPs@Cur group was close to 15 µg at the end of the first 24 h. Still, after it decreased until the third day, its level remained constant (nearly five µg) until the fifth day, indicating an increase in its bioavailability in the body, possibly due to a slow-release form.

The use of new drug delivery technologies to increase the shelf life of drugs and the possibility of targeting them has recently attracted the attention of many researchers. Various technologies have been tested regarding highly hydrophobic substances, such as Cur, including liposomal and phospholipid formulations, emulsions, nanogels, polymer micelles, polymer conjugates, self-assembling, and encapsulating nanoparticles [23]. In the present study, the evaluated concentration of Cur in the blood in the first hour in the SeNPs@Cur group is higher than the concentration of Cur in the blood in the group receiving free Cur, which is because Cur, along with the nanoparticle, becomes more soluble, so it is more soluble in the blood. It is solved and identified with more values [24].

Apiratikul et al. (2013) used a nanoliposome created from fat as a carrier for Cur. The amount of cellular absorption and the blood level of free and encapsulated Cur were compared. It was determined that by coating Cur, its absorption rate increased, and its blood level increased more than the control group [25]. Also, Rang Zhang et al. found Cur/Se nanoparticles could increase the bioactivity of curcumin and improve cancer therapy by regulating the gut microbiota. Which agrees with the combination of both Cur/Se in this research [26].

Sadeghi et al. (2013) introduced biocompatible nanotubes as carriers for Cur. In this research, polylysine and bovine serum albumin and layer-by-layer deposition methods were used to create nanotubes. Their results showed an increase in the solubility of Cur and its effect on the body [27].

Tiyaboonchai et al. (2007) investigated solid lipid nanoparticles loaded with Cur for dermal administration. The size of these nanoparticles loaded with Cur was close to 450 nm, and they were stable for six months at room temperature. These particles could be released for 12 h, while the sensitivity to light and oxygen in Cur composition was significantly reduced after being placed in this formulation. In the end, in vitro studies of this formulation on healthy volunteers showed that the effectiveness of this cream with this combination of Cur is higher than the cream with free Cur [28].

Rahimzadeh et al. (2016) investigated Cur's loading, toxicity, absorption, and release from a new surfactant nanotube. They reported that free Cur diffuses through the cell membrane and enters the cell, and after the cell cytoplasm is saturated with Cur, it is prevented from entering the cell. As a result of this process, all the characteristics of Cur can be seen shortly after entering the body, and its effects on the body disappear quickly. This is while using nanotubes causes Cur to enter the cell in the form of endocytosis and makes it possible for the cell to always have a proper accumulation of this substance that is released slowly [29].

Naderinezhad et al. (2017) investigated the fabrication of a biodegradable and self-accumulating anionic nanotube as a new approach to improve the delivery of Cur to bone cancer cells and provide a mathematical model for drug release kinetics. Their results showed that the placement of Cur in neosome, a vesicle based on non-ionic surfactants, can overcome the instability problem of neosome in plasma and improve its solubility. Examining the drug release profile at different times in 96 h showed that the neosemic system has slow-release Cur, and after 96 h, 43.87% of the total Cur is released into the plasma [30].

Zare Shehneh et al. (2018) investigated the anticancer function of Cur-containing lipid nanotubes as a new system in the direction of controlled drug release. They showed the optimized Cur-Cur-containing liponiscemic nanosystem with appropriate physical and chemical properties and increased drug stability. It can be a suitable carrier for drug delivery to cancer cells [31].

In the present study, the selenium analysis showed that this element released in the SeNPs group gradually decreased until the fifth day. In the SeNPs@Cur group, the amount of selenium was higher on the first day, and its amount gradually decreased, and on the third to the fifth day, its amount remained almost constant. Considering that no noticeable difference was observed between these two groups, the existence of a nanoparticle in both groups is confirmed.

Nano-sized materials have inhomogeneous characteristics of isolated atoms, and normal-sized coarse materials related to their high surface-to-volume ratio. SeNPs have attracted wide attention due to their high bioavailability and relatively low toxicity. For example, the LD50 of SeNPs in mice is 92.1 mg/kg; for selenomethionine, this value is 25.6 mg/kg [32].

When methionine is limited or catabolized, selenomethionine can be stored in protein by releasing and entering selenium into other storage. Therefore, the bioavailability of selenium depends on its absorption in the intestine and its transformation into a biologically active form [33].

Zhang et al. (2009) reported that SeNPs were more bioavailable than other forms by inducing selenoenzymes in cultured cells and selenium-deficient rats. Therefore, nano selenium may have a different bioavailability than other inorganic selenium by going through various transformation processes, and it may act differently, with a greater effect, and finally cause optimal growth performance [34].

Li et al. (2008) investigated the toxicity of SeNPs and selenite with an equal amount of 100 µg/l. They showed that SeNPs accumulated five times in the liver and LC50, four times more toxicity than the group receiving selenite and stated. More caution should be exercised when using these nanoparticles [35]. Also, Niels Hadrup and Gitte Ravn-Haren study the Acute human toxicity and mortality after selenium ingestion [36].

CONCLUSION

This study showed that the intraperitoneal administration of SeNPs@Cur, compared to the administration of free Cur, initially causes a high serum concentration and a loading dose, which continues with the slow release, increasing and maintaining the Cur serum level in the long-term treatment period. Maintaining the maintenance dose and thus improving the therapeutic functions for a longer period by prescribing a lower amount of the drug. This is important in treating inflammation and cancer disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This article results from a research project as 5963 project number in Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences. We want to thank the Vice Chancellor for Research and Technology of Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences for financing this research, as well as the staff of the Phytochemical Laboratory at the Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences Research Center for Medicinal Plants who cooperated in implementing this project.

ETHICS, CONSENT, AND PERMISSIONS

All investigational procedures used in this study were reviewed and approved by approved by the institutional ethical committee (IR. SKUMS. AEC.1401.011).

FUNDING

This research was funded by the Iran Government, By the Vice Chancellor for Research and Technology of Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences grant number 3913 mainly. Moreover, a number of supplemental grants for the veterinary medicine thesis project of the Shahrekord University (2846379) were used for this project.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization, investigation, writing, and Supervision; pegah khosraviyan and jahangir kaboutari; investigation and writing dhiya altememy, moose javdai and Fatemeh Sabaghi, hosein ali arab and Dhiya Altememy; review, investigation and editing all authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that they don’t have conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

Cheng AL, Hsu CH, Lin JK, Hsu MM, Ho YF, Shen TS. Phase I clinical trial of curcumin a chemopreventive agent in patients with high-risk or pre-malignant lesions. Anticancer Res. 2001;21(4B):2895-900. PMID 11712783.

Karunagaran D, Joseph J, Kumar TR. Cell growth regulation. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;595:245-68. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-46401-5_11, PMID 17569215.

Gowdy KM. Selenium supplementation and antioxidant protection in broiler chickens; 2004.

Zachara BA, Gromadzinska J, Wąsowicz W, Zbrog Z. Red blood cell and plasma glutathione peroxidase activities and selenium concentration in patients with chronic kidney disease: a review. Acta Biochim Pol. 2006;53(4):663-77. doi: 10.18388/abp.2006_3294, PMID 17160142.

Vareed SK, Kakarala M, Ruffin MT, Crowell JA, Normolle DP, Djuric Z. Pharmacokinetics of curcumin conjugate metabolites in healthy human subjects. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(6):1411-7. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2693, PMID 18559556, PMCID PMC4138955.

Scott ML, Thompsom JN. Selenium content of feedstuffs and effects of dietary selenium levels upon tissue selenium in chicks and poults. Poult Sci. 1971;50(6):1742-8. doi: 10.3382/ps.0501742, PMID 5158618.

Khosravian Dehkordi P, Asadi Samani M, Altememy D, Javadi Farsani F, Akbari M, Moradi MT. In vitro antiviral activity of curcumin-loaded selenium nanoparticles against human herpes virus type 1. J Shahrekord Univ Med Sci. 2024;26(2):73-7. doi: 10.34172/jsums.943.

Tabanelli R, Brogi S, Calderone V. Improving curcumin bioavailability: current strategies and future perspectives. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13(10):1715. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13101715, PMID 34684008, PMCID PMC8540263.

Asl FD, Altememy D, Khosravian P, Rezaee M, Saffari Chaleshtori J. Evaluation of curcumin effects on bad bak and bim: a molecular dynamics simulation study. J Pharm Negat Results. 2022;13(3):8-14. doi: 10.47750/pnr.2022.13.03.002.

Pescatello LS, Turner D, Rodriguez N, Blanchard BE, Tsongalis GJ, Maresh CM. Dietary calcium intake and renin angiotensin system polymorphisms alter the blood pressure response to aerobic exercise: a randomized control design. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2007 Jan 4;4:1. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-4-1, PMID 17204161.

Garcea G, Berry DP, Jones DJ, Singh R, Dennison AR, Farmer PB. Consumption of the putative chemopreventive agent curcumin by cancer patients: assessment of curcumin levels in the colorectum and their pharmacodynamic consequences. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(1):120-5. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.120.14.1, PMID 15668484.

Mohamad RH, El Bastawesy AM, Zekry ZK, Al Mehdar HA, Al Said MG, Aly SS. The role of Curcuma longa against doxorubicin (adriamycin) induced toxicity in rats. J Med Food. 2009;12(2):394-402. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2007.0715, PMID 19459743.

Jungbauer A, Hahn R. Ion-exchange chromatography. Methods Enzymol. 2009;463:349-71. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)63022-6, PMID 19892182.

Stadtman TC. Selenium biochemistry. Annu Rev Biochem. 1990;59:111-27. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.59.070190.000551, PMID 2142875.

Kumari M, Purohit MP, Patnaik S, Shukla Y, Kumar P, Gupta KC. Curcumin loaded selenium nanoparticles synergize the anticancer potential of doxorubicin contained in self-assembled cell receptor targeted nanoparticles. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2018;130:185-99. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2018.06.030, PMID 29969665.

Adaramoye OA, Anjos RM, Almeida MM, Veras RC, Silvia DF, Oliveira FA. Hypotensive and endothelium independent vasorelaxant effects of methanolic extract from Curcuma longa L. in rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;124(3):457-62. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.05.021, PMID 19481144.

Altememy D, Javdani M, Khosravian P, Khosravi A, Moghtadaei Khorasgani E. Preparation of transdermal patch containing selenium nanoparticles loaded with doxycycline and evaluation of skin wound healing in a rat model. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2022;15(11):1381. doi: 10.3390/ph15111381, PMID 36355552.

Al Shoyaib A, Archie SR, Karamyan VT. Intraperitoneal route of drug administration: should it be used in experimental animal studies? Pharm Res. 2019;37(1):12. doi: 10.1007/s11095-019-2745-x, PMID 31873819, PMCID PMC7412579.

Lestari ML, Indrayanto G. Curcumin. Profiles Drug Subst Excip Relat Methodol. 2014;39:113-204. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800173-8.00003-9, PMID 24794906.

Wahlstrom B, Blennow G. A study on the fate of curcumin in the rat. Acta Pharmacol Toxicol (Copenh). 1978;43(2):86-92. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1978.tb02240.x, PMID 696348.

Yu H, Huang Q. Enhanced in vitro anti-cancer activity of curcumin encapsulated in hydrophobically modified starch. Food Chem. 2010;119(2):669-74. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.07.018.

Hong J, Bose M, Ju J, Ryu JH, Chen X, Sang S. Modulation of arachidonic acid metabolism by curcumin and related β-diketone derivatives: effects on cytosolic phospholipase a 2, cyclooxygenases and 5-lipoxygenase. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25(9):1671-9. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh165, PMID 15073046.

Yallapu MM, Jaggi M, Chauhan SC. Curcumin nanoformulations: a future nanomedicine for cancer. Drug Discov Today. 2012;17(1-2):71-80. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2011.09.009, PMID 21959306.

Mohammad Akaboli, Javdani M, Amini Khoei H, Mehreganzadeh P, Driss F, Karimi M. Investigating the role of nanoparticle based curcumin implants in prevention of post laparotomy peritoneal adhesion: an in vivo study. International Journal of Applied Pharmaceutics. 2024;16(5):326-31. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2024v16i5.50976.

Apiratikul N, Penglong T, Suksen K, Svasti S, Chairoungdua A, Yingyongnarongkula B. In vitro delivery of curcumin with cholesterol based cationic liposomes. Bioorg Khim. 2013;39(4):497-503. doi: 10.1134/S1068162013030035, PMID 24707732.

Zhang R, Zhang W, Zhang Q, Wang L, Yang F, Sun W. Curcumin modified selenium nanoparticles improve S180 tumour therapy in mice by regulating the gut microbiota and chemotherapy. Int J Nanomedicine. 2024 Dec 20;19:13653-69. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S476686, PMID 39720218, PMCID PMC11668068.

Sadeghi R, Kalbasi A, Emam Jomeh Z, Razavi SH, Kokini J, Moosavi Movahedi AA. Biocompatible nanotubes as potential carrier for curcumin as a model bioactive compound. J Nanopart Res. 2013;15(11):1-11. doi: 10.1007/s11051-013-1931-8.

Tiyaboonchai W, Tungpradit W, Plianbangchang P. Formulation and characterization of curcuminoids loaded solid lipid nanoparticles. Int J Pharm. 2007;337(1-2):299-306. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.12.043, PMID 17287099.

Rahimzadeh M, Sadeghizadeh M, Najafi F, Arab SS, Mobasheri H. Study of loading cytotoxicity uptake and release of curcumin from a novel gemini surfactant nanocarrier. Pathobiol Res. 2016;19(1):13-27.

Naderinezhad S, Haghirosadat F, Amoabediny G, Naderinezhad A, Esmaili Z, Akbarzade A. Synthesis of biodegradable and self-assembled anionic nano-carrier: novel approach for improvement of curcumin delivery to bone tumors cells and mathematical modeling of drug release kinetic. New Cellular and Molecular. Biotechnol J. 2017;7(27):77-84.

Shehneh MZ, Kalantar SM, Sheikhha MH, Asri Kojabad AA, Haghiralsadat BF. Study of anti-cancer effects of curcumin; formulation of curcumin loaded nano carrier and its toxicity effect on MCF-7 cell line. J Shahid Sadoughi Univ Med Sci. 2019;27(1):875. doi: 10.18502/ssu.v27i1.875.

Xia T, Li N, Nel AE. Potential health impact of nanoparticles. Annu Rev Public Health. 2009;30(1):137-50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100155, PMID 19705557.

Foster LH, Sumar S. Selenium in the environment food and health. Nutr Food Sci. 1995;95(5):17-23. doi: 10.1108/00346659510093991.

Zhang J, Wang X, Xu T. Elemental selenium at nano size (nano-Se) as a potential chemopreventive agent with reduced risk of selenium toxicity: comparison with se-methylselenocysteine in mice. Toxicol Sci. 2008;101(1):22-31. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm221, PMID 17728283.

Li H, Zhang J, Wang T, Luo W, Zhou Q, Jiang G. Elemental selenium particles at nano-size (nano-Se) are more toxic to Medaka (Oryzias latipes) as a consequence of hyper accumulation of selenium: a comparison with sodium selenite. Aquat Toxicol. 2008;89(4):251-6. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2008.07.008, PMID 18768225.

Hadrup N, Ravn Haren G. Acute human toxicity and mortality after selenium ingestion: a review. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2020 Mar;58:126435. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2019.126435, PMID 31775070.