Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 4, 2025, 279-289Original Article

INVESTIGATING THE EFFICACY OF CURCUMIN NANOEMULGEL IN COMBATING BACTERIAL ACTIVITY USING AGAR DIFFUSION METHOD AND BROTH DILUTION METHOD

JOSHNA BOORAVILLI, JANAKI DEVI SIRISOLLA*

*Department of Pharmaceutics, GITAM School of Pharmacy, GITAM (Deemed to be University), Visakhapatnam, India

*Corresponding author: Janaki Devi Sirisolla; *Email: jsirisol@gitam.edu

Received: 31 Dec 2024, Revised and Accepted: 10 Apr 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: The objective of this study was to develop a topical delivery formulation of curcumin nanoemulgel, evaluating its antibacterial activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria.

Methods: Curcumin-containing nanoemulsion was developed by spontaneous emulsification technique. Using a central composite design, the formulation was selected and further evaluated for size analysis, zeta potential, and Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM). Furthermore, the optimized curcumin nanoemulgel was evaluated for its antibacterial activity.

Results: The in vitro antibacterial assay of curcumin nanoemulgel (CUR-CLO NEG 1) exhibits better antibacterial activity against Gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus.) than Gram-negative bacteria Escherichia coli (E. coli.). Inhibition zones of 27.34±0.15 mm (S. aureus.) and 25.32±0.54 mm (E. coli.) were observed by optimized nanoemulgel. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) values against S. aureus. and E. coli. was 120 and 125 µg/ml, respectively. The agar diffusion method revealed significant inhibition zones for g-positive bacteria (S. aureus), whereas the broth dilution method confirmed its effective growth inhibition at lower concentrations in S. aureus. The results in this research work highlight the remarkable breakthrough of curcumin nanoemulgel as a highly effective antibacterial drug delivery system.

Conclusion: The curcumin nanoemulgel retained its better antibacterial properties over drug free loaded nanoemulgel and curcumin plain gel. From the research work, it can be concluded that both the agar diffusion method and broth dilution method confirm the curcumin nanoemulgel's antibacterial activity against g-positive bacteria (S. aureus).

Keywords: Antibacterial activity, Curcumin, Nanoemulgel, Spontaneous emulsification, Smix

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i4.53560 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) is a major public health problem in the 21st century, resulting from changes in bacteria that make antibiotics less effective. The UK Government commissioned the Review on Antimicrobial Resistance, which estimated that AMR might kill 10 million people annually by 2050 [1-3]. Kariuki's 2024 study reveals the global burden of Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) is projected to increase from 1990 to 2021 and continue until 2050, emphasizing the need for coordinated efforts [4]. The study predicts a rise in AMR to 1.91 million attributable and 8.22 million related fatalities by 2050, necessitating novel drug delivery techniques to combat AMR [5].

Nanotechnology-based formulations, such as niosomes/proniosomes, solid lipid nanoparticles, drug nanocrystals, liposomes, and nanostructured lipid carriers, have improved hydrophobic compound bioavailability [6], with United States Food and Drug Administration (USFDA) approvals indicating their effectiveness.

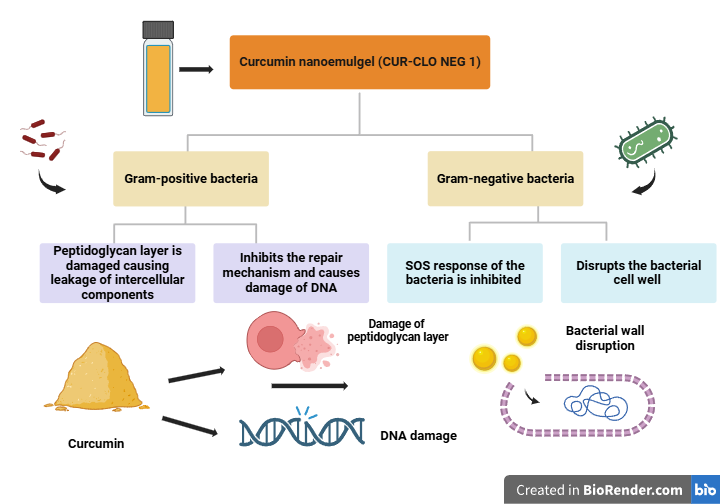

Curcumin, a naturally occurring polyphenolic compound with anti-inflammatory, cancer, and antioxidant properties, requires a unique formulation for effective distribution due to its low bioavailability [7-10]. Curcumin inhibits the action of many bacteria, including Salmonella paratyphi, Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis, Paenibacillus macerans, Bacillus licheniformis, Staphylococcus aureus, and Azotobacter [13].

Fig. 1: Mechanism of action of curcumin nanoemulgel on g-positive and g-negative bacteria

Nanoemulsions, tiny droplets of immiscible liquids, are stable for topical applications but have low viscosity and poor skin retention. Integrating nanoemulgels into gelling systems improves therapeutic use, outperforming traditional lipophilic drug formulations.

Nanoemulgel was chosen as a curcumin delivery platform because it can overcome crucial curcumin limitations such as poor solubility, bioavailability, and stability. Curcumin is hydrophobic, which complicates systemic absorption and therapeutic efficacy. Nanoemulgels, which combine the solubilizing qualities of nanoemulsions with the long-term release and retention abilities of a gel matrix, efficiently address these difficulties. The nanoemulsion component disperses curcumin into nano-sized droplets, increasing its solubility and allowing for greater penetration through biological membranes. Meanwhile, the gel basis promotes long-term retention at the application site, resulting in a regulated release that reduces dose frequency and increases patient compliance [11]. Furthermore, nanoemulgels protect curcumin against environmental and enzymatic breakdown, which is prevalent in physiological conditions. Nanoemulgels are easier and less expensive to prepare than other nanotechnology platforms, such as liposomes, solid lipid nanoparticles, or dendrimers, making them ideal for large-scale production. Furthermore, their topical and transdermal treatments have the benefit of localized administration with limited systemic exposure, minimizing the risk of side effects. The gel component also improves patient comfort by being easy to apply and providing soothing properties, which is especially useful for dermatological or mucosal treatments [12].

While liposomes and polymeric nanoparticles improve curcumin's solubility and stability, they frequently require more complex manufacturing processes and lack the versatility of nanoemulgels, which can incorporate both hydrophilic and lipophilic drugs. Overall, nanoemulgels represent a superior choice for curcumin delivery, effectively addressing formulation challenges while offering scalability and patient-friendly administration.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Curcumin was obtained from Oxford Lab Fine Chem LLP, Palghar-410210, Maharashtra, India. Yarrow Chem products (Mumbai, Maharashtra 400086) provided the clove oil, Cremophor RH ®40, and additional excipients. The Milli-Q water was purified using a Milli-Q water purification system (ELGA, made in the UK). Sigma Life Science, Sigma Aldrich (Belgium) was the supplier of PEG 400. Methanol (HPLC grade; 99.9% purity) was supplied by Sigma-Aldrich, located in Steinheim, Germany.

Animals

Male Wistar rats were procured from Vyas Labs, Hyderabad. The approval for the animals was given by the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee (IAEC) with proposal no: IAEC/GU-1287/JDS-F/5/December 2023. Before the study, the animals were isolated and subjected to light and dark cycles before use.

Methods

Screening of the chemicals suitable for the preparation of nanoemulsion

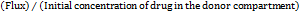

a. Investigation of the solubility of oils, cosurfactants, and surfactants

Based on curcumin's solubility, excipients such oil, surfactant, and co-surfactant were chosen to form a stable nanoemulsion. Oleic acid, peppermint, eucalyptus, lemongrass, castor, anise, clove, coconut, arachis, cinnamon, and neem oil were among the oils used. Only a small number of oils were selected due to their biodegradability and ease of accessibility. Tween-20, Cremophor ® RH 40, Tween-80, Polyethylene glycol 200 (PEG 200), Polyethylene glycol 400 (PEG 400), Span 80, and propylene glycol were the surfactants that were selected.

The solubility of curcumin in different nanoemulsion components was evaluated by vortexing an excess of curcumin with the selected solvent (2 ml) in 5 ml stoppered glass vials [14]. In a bath shaker, the glass vials were constantly shaken for 48 h at 25±2 °C. After that, the samples were centrifuged for 15 min at 3000 rpm. A membrane filter was used to filter the supernatant. To calculate the amount of curcumin soluble, the supernatant was measured at 423 nm using a UV-visible spectrophotometer.

Selection of curcumin nanoemulsion formulation

When selecting different formulations from the phase diagrams to introduce curcumin into the oil phase, the nanoemulsion zone of each generated phase diagram was taken into account. For convenience, a 1 ml nanoemulsion formulation was selected, along with a dosage of 5 mg of curcumin. The oil concentration should be solubilized so that the drug is completely dissolved. Different oil concentrations were chosen at 5% intervals based on each phase diagram. The effect of curcumin was analyzed based on the phase diagram's nanoemulsion area. The phase diagram was used to determine the lowest concentration of Smix for the preparation of the nanoemulsion for each % of oil chosen. The ternary phase diagram was constructed using Chemix school software, and the desired ratio was selected based on fig. 2B.

Optimizing the curcumin nanoemulsion

This study optimized curcumin formulations using the surface response approach and Design Expert® version 13.0.5.0 64-bit. Central Composite Design (CCD) and Box-Behnken Design (BBD) are used in pharmaceutical research to optimize nano formulations. Compared to BBD, which can only define low, middle, and high values of independent variables, CCD is more effective at predicting responses [14]. As indicated in table 1A, CCD was selected for this investigation in order to optimize the nanoemulsion [14, 15]. Oil, Smix, and water were the independent factors, and the dependent variables were globule size (nm), zeta potential (mV), and drug content (%). The software suggested the best formulations out of the 20 runs that were produced.

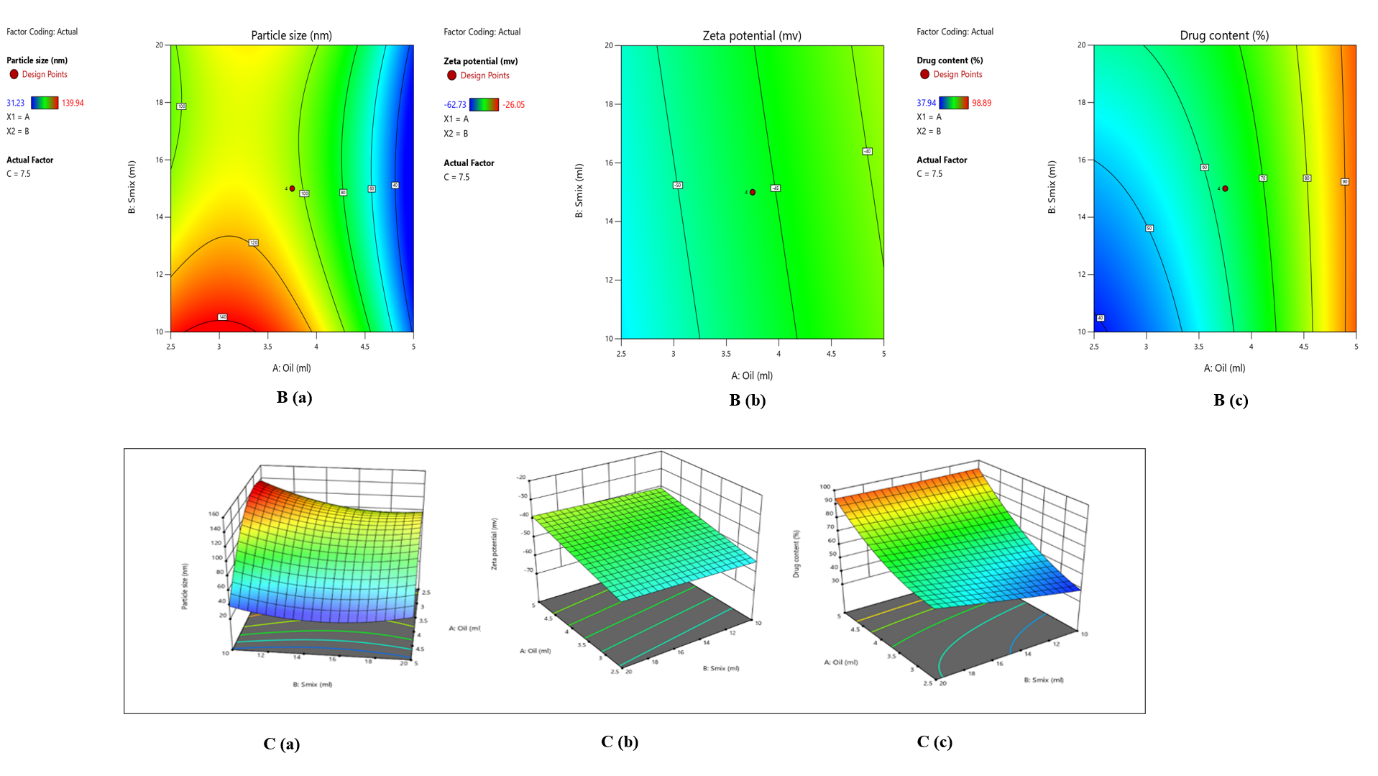

Formulation of curcumin-loaded nanoemulsion by spontaneous emulsification method

Curcumin nanoemulsion (CUR-CLO NE) was prepared by the spontaneous emulsification method. After precisely weighing the drug, it was dissolved in the oil phase and sonicated until it was completely soluble. To prepare the aqueous phase, the cosurfactant and surfactant were mixed together, then water was added dropwise until a uniformly transparent solution was achieved. The aqueous and above oil phases were combined to formulate a nanoemulsion.

Nanoemulsion evaluation studies

Examination of droplet size

As indicated in table 2A, photon correlation spectroscopy was used to determine the nanoemulsion droplet size. The mixture (0.1 milliliters) was spread out in a volumetric flask with 50 milliliters of water, and the flask was tilted slightly to stir the mixture. A Zeta sizer 1000 HS (Malvern Instruments, Worcestershire, UK) was used to take the measurement. At 25 °C, light scattering was seen at a 90° angle.

Zeta potential determination

Surface charges of particles are measured using zeta potential. The Horiba Scientific nanoparticle analyzer (nanoPartica SZ-100V2 Series) was utilized to detect the zeta potential using electrophoretic mobility. The experiment was carried out using a continuous electrical field of 1 volt and a dynamic light scattering particle size analyzer set to 633 nm. The nanoemulsion was diluted 1:100 with pre-filtered, double-distilled water. Three consecutive measurements of each sample's potential were made using the same cuvette just after the DS measurements [16]. Then, in compliance with Ahmad et al. [17–20], the mean value and standard were determined.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) for microscopic analysis of curcumin nanoemulsion

Prior to examination, a sputter coater vacuum-coated the sample with gold, and a Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) (S-4800, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) was used to examine its morphology. 1 ml of the optimized curcumin nanoemulsion (CUR-NE 1) was diluted, put on a piece of tin foil, and allowed to dry at room temperature [20].

Evaluation of viscosity of curcumin nanoemulsion

The Brookfield Engineering DV III ultra V6.0 RV cone and plate rheometer was used. The viscosity of the formulations without dilution (0.5 g) was assessed using spindle no. 60 at 25±0.5 °C (Laboratories, Inc., Middleboro, MA), as indicated in table 2A. Rheocalc V2.6 was used to calculate the viscosity.

Measurement of drug content

A UV-visible spectrophotometer ((SHIMADZU-1880) was used to measure the drug content. The formulation was diluted using ethanol as a solvent in the ratio 1:10, and the absorbance at a wavelength of 423 nm was measured. The following was found to be the drug content:

………. (1) [21]

………. (1) [21]

Formulation of curcumin nanoemulgel

Preparation of carbopol 934 hydrogel

Preparing the carbopol base

In order to make carbopol gel, 1 g of carbopol was dissolved in 100 ml of distilled water. The gel solution was then left overnight before being added to nanoemulsion formulations.

Preparing curcumin-loaded nanoemulgel

The nanoemulsion was continuously stirred for 15 min as the carbopol gelling solution was well mixed in a 1:1 ratio. As a result, a consistent semisolid nanoemulgel formulation was prepared. Triethanolamine was lastly added to the nanoemulgel formulation to lower its pH down to 4.5–5.5, which is the same as human skin, in order to avoid any toxicity [22].

Evaluation of the pH of curcumin nanoemulgel

To determine the pH of nanoemulgel at room temperature, or about 25 °C, a calibrated digital pH meter (pH meter, Toshcon Industries Pvt. Ltd., Hardwar, India) was implemented. To record the values, the electrode of the device was immersed directly in the glass beaker containing the formulation of the test sample [23].

Determination of viscosity

The viscosity of the formulations was measured at 25±0.5 °C using a Brookfield DV III ultra V6.0 RV cone and plate rheometer (Brookfield Engineering Laboratories, Inc., Middleboro, MA) fitted with spindle no 62 [24].

Spreadability

Nanoemulgel's spreadability was assessed using a drag and slip method. There are two glass slides in the setup. The lower slide was secured in the bottom, and the upper slide was suspended with the aid of a thread that had been weighted. Two gs of the formulation were placed on the lower slide, which was positioned between the two slides. The spreadability of the formulation was computed using equation 2, and the time it took for two slides to separate from one another was noted.

………. (2)

………. (2)

Extrudability

Conventional collapsible aluminium tubes with caps were filled with the gel compositions, and crimps were used to seal the ends. The tubes were placed between two glass slides and clamped. After placing 500 g of weight over the slides, the cap was removed. We collected and weighed a certain amount of the extruded gel.

Uniformity of curcumin nanoemulgel drug content

To guarantee homogeneity, 0.5 g of gel was extracted from three separate gel sections in order to assess the curcumin content of the produced nanoemulgel. Methanol (10 ml) was used to extract each component of the chosen nanoemulgel, and it was centrifuged for 15 min at 3000 rpm. The curcumin content was determined by UV-visible spectrophotometric analysis, which measured the λ max at 423 nm after filtering the sample supernatant. The percentage of curcumin in the sample was analyzed three times [25].

Investigation of curcumin nanoemulgel’s stability

In order to investigate the stability of the prepared formulation, studies on the impact of temperature were carried out by keeping it at different temperatures. In the case of freeze/thaw cycles, the produced nanoemulgel was centrifuged for 30 min at 3500 rpm for thermodynamic analysis. As per ICH (International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use) guidelines Q1(R2), each composition was stored for three months at 4 °C in the freezer, 25 °C at room temperature, and 40 °C at high temperature in tightly sealed containers. Sampling was done at intervals of 0, 7, 21, 30, 60, and 90 d. The compounds were analyzed for pH, drug concentration, and physiological changes (e. g., colour changes, transparency, phase separation, and drug precipitation) [26].

Ex vivo investigations on drug penetration

The study examined curcumin's ex vivo penetration using a developed formulation. The skin of a male Wistar rat was removed, washed, and kept in a pH 7.4 phosphate buffer. The skin was positioned in between the donor and receptor compartments. 100 ml of phosphate buffer pH 7.4 was mixed with 5% ethanol in a 1:2 ratio to fill the receptor medium [27]. The donor compartment was then filled with 0.2 g of the nanoemulgel formulation, which was stirred at 300 rpm. Samples were gathered at various times and subjected to spectrophotometric analysis at 423 nm using a Shimadzu device. Calculations were made for parameters such as enhancement ratio, permeability coefficient (Kp), and flux (Jss).

Flux (JSS) =  ……… (3)

……… (3)

Permeation coefficient (Kp) =

……. (4)

……. (4)

In vitro antimicrobial activity of curcumin nanoemulgel

The antibacterial activity of CUR-CLO NEG 1, DFL-CLO NEG, and CG was evaluated against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, such as E. coli. (ATCC 25922) and S. aureus. (ATCC 25923) (Saint Cloud, Minnesota, USA: MicroBiologics). With modifications, Hettiarachchi's study served as the model for the agar well diffusion method [28]. Mueller-Hinton (MH) agar (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) was added to Petri plates and let to settle in order to prepare the plates for the study. By diluting bacterial cultures with 0.9% sterile sodium chloride solution, they were brought up to the 0.5 McFarland standard [29]. To ensure uniform distribution, bacterial solutions were mixed into the agar medium and then solidified. Wells were then created using the sterile back of a Pasteur pipette. 10 mg of the samples (CUR-CLO NEG 1, DFL-CLO NEG, and CG) were dissolved in DMSO. Wells were then filled with 65µl of prepared solutions. After that, the plates were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. A calliper (RS PRO, Shanghai, China) was used to measure the inhibitory zones following incubation.

Antimicrobial study by broth dilution method

In compliance with CLSI (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute) recommendations, an antibacterial susceptibility test was conducted. Microbial suspensions of Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC: 29,213) and Escherichia coli (ATCC: 25,922) were developed in a sterilized physiological solution to achieve a concentration of 108 CFU/ml (0.5 McFarland turbidity). Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) experiments were conducted on 96-well plates [30]. Each well contained 100 μl of Mueller-Hinton broth. Diluted stock solutions of CUR-CLO NEG, DFL-CLO NEG and CG were added to the first well of each row at 100 μl each. Serial dilutions were used to achieve final concentrations of 28.57-285 μg/ml for all the formulations. Control wells did not contain any antibacterial agents. After adding 100 μl of bacterial suspensions to each well, the plates were incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. The MIC (Minimal Inhibitory Concentration) of an antibacterial agent is determined by the sample's clarity and prevents visible bacteria growth.

Scaling up of curcumin nanoemulgel

Following the successful formulation and evaluation of the nanoemulgel on a lab scale, a scale-up process was carried out to determine the feasibility of developing bigger batches. Curcumin nanoemulsion formulation was scaled up to 1000 ml using high-pressure homogenization with the lowest temperature. After successfully developing the curcumin nanoemulsion, a similar procedure as discussed earlier was used to prepare curcumin nanoemulgel.

RESULTS

a. Investigation of the solubility of oils, cosurfactants, and surfactants

The solubility of curcumin in different oils was established, and the solubility of clove oil was chosen because of its kinetic stability and ability to form a stable nanoemulsion [31]. As illustrated in fig. 2A, curcumin exhibited the highest solubility of 10.52±3.12 mg/ml in lemongrass oil, 10.33±3.35 mg/ml in cinnamon oil, and 9.7±3.32 mg/ml in clove oil, according to the solubility studies. Curcumin's superior solubility in clove oil, when compared to lemongrass and cinnamon oils, suggests that it could enhance curcumin's bioavailability by facilitating its dispersion in a stable nanoemulsion form. This is particularly important because increased solubility leads to better absorption and more effective delivery of curcumin to the target site. Clove oil's kinetic stability also supports its use, as it reduces the likelihood of Alam et al. [32] reported that nanoemulsions have a modest Ostwald ripening propensity, underscoring the significance of choosing appropriate surfactants and cosurfactants for nanoemulsion formulation. The addition of PEG 400 reduces interfacial tension and increases the coating's flexibility, underscoring the necessity for careful selection.

Selection of curcumin nanoemulsion formulation

The drug-loaded nanoemulsion was made with the same oil and mix ratios after the ternary phase diagram analyses showed that the placebo formulation was stable. 10 % surfactant and 10 % cosurfactant in a 1:1 ratio was selected based on nanoemulsification, and 5 % oil was selected for the curcumin dosage. The small nanoemulsion area, which shows the impossibility of emulsification for smix ratios of 1:0, 1:0.25, and 1:0.5, was not used for the formulation of nanoemulsion.

Optimizing the curcumin nanoemulsion

The independent components mentioned in table 1A were chosen based on the smix ratio 1:1 derived from the ternary phase diagram.

Table 1A: Various parameters and concentrations were chosen to optimize the curcumin nanoemulsion

| Independent factors | Symbol | Low level (-1) | High level (+1) |

| Clove oil | A | 2.50 | 5.00 |

| Smix | B | 10.00 | 20.00 |

| Water | C | 5.00 | 10.00 |

| Dependent factors | Symbol | ||

| Particle size | R1 | ||

| Drug content | R2 |

Table 1B: Explains the experimental design and results from the optimization stage

| Runs | A (%) | B (%) | C (%) | (R1) Particle size (nm) | (R2) Zeta potential (mv) | (R3) Drug content (%) |

| 1 | 2.5 | 10 | 5 | 135.79 | -56.11 | 37.94 |

| 2 | 3.75 | 15 | 7.5 | 97.69 | -62.73 | 67.03 |

| 3 | 2.5 | 10 | 10 | 139.94 | -59.02 | 38.47 |

| 4 | 3.75 | 15 | 11.7045 | 96.37 | -26.05 | 64.47 |

| 5 | 5 | 20 | 10 | 31.23 | -38.30 | 98.89 |

| 6 | 5 | 15 | 20 | 39.46 | -38.47 | 96.37 |

| 7 | 3.75 | 15 | 7.5 | 136.47 | -39.02 | 56.73 |

| 8 | 5 | 15 | 10 | 36.93 | -40.02 | 94.73 |

| 9 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 35.73 | -42.15 | 93.67 |

| 10 | 2.5 | 20 | 10 | 92.67 | -57.26 | 52.56 |

| 11 | 5 | 12 | 20 | 32.58 | -39.14 | 92.56 |

| 12 | 3.75 | 23.409 | 7.5 | 134.76 | -48.11 | 72.06 |

| 13 | 5 | 10 | 10 | 38.56 | -38.57 | 93.05 |

| 14 | 3.75 | 15 | 7.5 | 93.04 | -47.14 | 62.03 |

| 15 | 5 | 20 | 10 | 31.23 | -39.05 | 93.67 |

| 16 | 3.75 | 15 | 3.29552 | 95.46 | -45.01 | 55.03 |

| 17 | 5 | 15 | 20 | 35.04 | -39.38 | 92.94 |

| 18 | 5 | 20 | 5 | 36.67 | -39.46 | 90.03 |

| 19 | 3.75 | 15 | 7.5 | 97.48 | -42.03 | 67.26 |

| 20 | 2.5 | 20 | 5 | 100.25 | -45.03 | 62.78 |

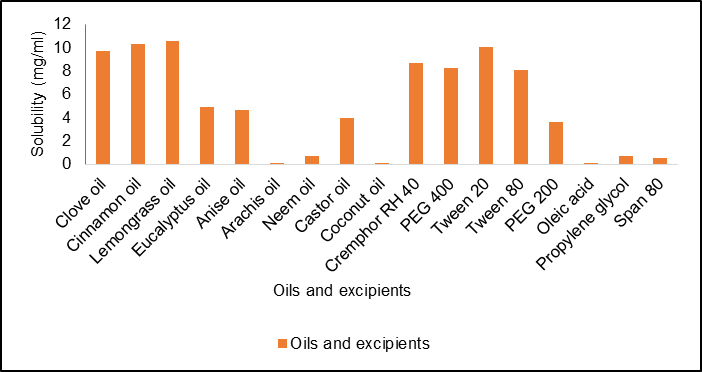

The influence of factors on drug content (%) and particle size (nm)

The mean globule size (nm) and entrapment efficiency (% EE) values were determined using Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) after data collection [33]. A total number of 20 runs were provided as shown in table 1B. The responses R1 (mean particle size), R2 (zeta potential), and R3 (% drug content) ranged between 31.23 –139.94 nm,-38.3 – 59.02, and 34.92 – 98.89 %, respectively. For responses R1, R2, and R3, it was found that the ratio of maximum to minimum was 4.48, 2.41, and 2.61, respectively. There was no need to modify the data because they were less than 10. Adequate precision was used to estimate the signal-to-noise ratio, which is considered ideal if it is more than 4 [34]. Responses R1, R2, and R3 were found to have adequate precision at 11.8123, 5,03, and 19.67. It was found that the predicted r2 values for R1, R2, and R3 were 0.7558, 0.2496, and 0.8400, respectively. Fig. 2B and fig. 2C show the 2D and 3D responses of particle size, zeta potential, and drug content.

The following were the final coded equations for responses R1, R2, and R3:

R1= 103.83-39.95A-10.23B+9.24AB+1.85AC-0.5395BC-41.46A2+14.94B2-0.1037C2 ……… (1)

R2=-46.19+6.75A+1.10B+0.3324C ………. (2)

R3= 66.21+22.60A+4.92B+0.9171C-4.81AB+2.00AC+0.0202BC+8.05A2+0.4311B2 – 0.5608C2 ………. (3)

Fig. 2: (A) Solubility studies of curcumin, B (a) 2D plot of particle size, B (b) 2D plot of zeta potential, B (c) 2D plot of drug content, 3D plots demonstrating the effect of several parameters on C (a) particle size, C (b) zeta potential, and C (c) drug content

Formulation of curcumin nanoemulsion by spontaneous emulsification method

Curcumin nanoemulsions CUR-CLO NE 1, CUR-CLO NE 2, CUR-CLO NE 3, and CUR-CLO NE4 were generated using the spontaneous emulsification method, as illustrated in fig. 3A, and the prepared nanoemulsion as shown in fig. 3B was then evaluated.

Nanoemulsion evaluation studies

Examination of droplet size

The two key variables for assessing nanoscale particles and their distribution are droplet size and PDI; droplet size is crucial for the NE's stability and skin penetration. The droplet sizes for CUR-CLO NE 1, CUR-CLO NE 2, CUR-CLO NE 3, and CUR-CLO NE 4 were 30.2±0.11, 40.5±0.36, 35.4±0.70, and 54.9±0.37 nm, with PDI values of 0.145, 0.466, 1.345, and 0.285. With CUR-CLO, NE 1 has the lowest droplet size (10-200 nm) and PDI<0.5. However, CUR-CLO NE 3 had a PDI value of 1.345, which was unacceptable. Mohammed S. Algahtani et al. (2020) investigated curcumin nanoemulsions with droplet sizes ranging from 10.57 to 68.87 nm and PDIs ranging from 0.094 to 0.550 nm, which backed up their findings.

Zeta potential determination

The zeta potential must be evaluated in order to calculate the overall surface charge and stability of the improved Curcumin nanoemulsion formulation. Table 2A displays the zeta potential values for developed nanoemulsion formulations, which ranged from-38.3±0.25 mV to-50.9±0.23.

The CUR-CLO NE 1 (A) exhibited the lowest zeta potential, measuring-38.3±0.25 mV. Negative zeta potential values could be caused by the presence of negatively charged fatty acid esters in clove oil [35, 36].

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) for microscopic analysis of curcumin nanoemulsion

Fig. 3C depicts the synthesized curcumin nanoemulsion (CUR-CLO NE 1), which contained spherical emulsion globules.

Evaluation of viscosity of curcumin nanoemulsion

Table 2A shows the viscosity of the formulations CUR-CLO NE 1, CUR-CLO NE 2, CUR-CLO NE 3, and CUR-CLO NE 4. CUR-CLO NE 1 is the formulation with the lowest viscosity. This is owing to the existence of low smix and oil concentrations, which are ideal for the preparation of nanoemulsions, as well as their ease of handling.

Fig. 3: Schematic illustration of the procedure for preparing curcumin nanoemulsion using the spontaneous emulsification approach (A), a clear curcumin nanoemulsion (B), and SEM analysis of optimized curcumin nanoemulsion (CUR-CLO NE 1) (C)

Table 2A: Evaluation studies of curcumin nanoemulsion

| Formulation | Evaluation parameters | Key advantages | Inference |

| CUR-CLO NE 1 | Particle size-30.2±0.11 PDI-0.145 Zeta potential--38.3±0.23 Viscosity-33±6 Drug content-98.21±0.12% |

-Enhances bioavailability with smaller particle size. -Uniform dispersion due to low PDI. -Stable formulation with sufficient negative zeta potential. -High curcumin load for effective delivery. -Well-balanced viscosity for easy application. |

Highly stable due to its small size, low PDI, and stable zeta potential. |

| CUR-CLO NE 2 | Particle size-40.5±0.36 PDI-0.466 Zeta potential--49.0±0.31 Viscosity-39±3 Drug content-92.34±0.34% |

-Higher zeta potential causing instability. -Increased viscosity improves retention on the skin. |

Moderately stable because of its larger particle size and higher PDI, leading to a higher risk of aggregation. |

| CUR-CLO NE 3 | Particle size-35.4±0.70 PDI-1.345 Zeta potential--50.9±0.25 Viscosity-36±4 Drug content-93.11±0.16% |

-Strong zeta potential provides partial stability. -Adequate drug content and viscosity. |

Less stable due to a higher PDI, which increases the likelihood of aggregation and instability. |

| CUR-CLO NE 4 | Particle size-47.5±0.3 PDI-0.285 Zeta potential--47.8±0.22 Viscosity-40±3 Drug content-90.65±0.23% |

-Lesser zeta potential when compared to CUR-CLO NEG 3 but more viscosity | Least stable due to the large particle size, which may lead to phase separation or aggregation. |

The data for the above study are given as mean±SD, n = 3

Selection of optimized formulation

Based on the evaluation studies done on the prepared curcumin nanoemulsion, CUR-CLO NE 1 was superior due to its smaller particle size, which improves curcumin bioavailability and absorption. It has a low PDI, which promotes homogeneity and stability. The zeta potential of-38.3±0.23 mV prevents aggregation and enhances stability. The highest drug content provides an effective therapeutic dose. Additionally, its optimal viscosity offers good spreadability and retention for topical applications. Therefore, it was selected and loaded into the carbopol gel for further evaluation studies.

Characterization of curcumin nanoemulgel

pH

The optimized nanoemulgel CUR-CLO NEG 1 had a pH of 6.69±0.06, falling within the optimum range of 4-6.

Viscosity

The viscosity of CUR-CLO NEG 1 was measured to be 136.52±1.31. The high viscosity of the gel may prevent droplet coalescence and uniform dispersion of droplets. Adding 1% w/v Carbopol 934 to formulations significantly increased viscosity. Furthermore, increasing the Smix concentration resulted in higher viscosity [37].

Spreadability and extrudability

The study found that topical gels' extrudability and spreadability are critical for patient compliance. The extrudability and spreadability values were 9.27±4.91 g. cm/s and 18.54±1.63 g. cm/s, respectively. The formulation's remarkable skin spreadability and simplicity of extrusion supported Ali et al. [38]'s prior studies, which underlined the importance of these qualities for uniform distribution and patient compliance.

Drug content

The optimized nanoemulgel formulation CUR-CLO NEG 1 has a drug content of 98.60±0.52. The results showed that the medication was equally distributed throughout the formulation, with very little loss throughout the nanoemulgel formulation process.

Investigation of curcumin nanoemulgel’s stability

The physical stability of the CUR-CLO NEG 1 sample was tested while stored at various temperatures. The nanoemulgel samples were kept for 90 d. Table 2B shows the physical properties of the formulation, such as pH, viscosity, and curcumin drug concentration, at various time intervals (0, 30, 60, and 90).

Table 2B: Curcumin nanoemulgel (CUR-CLO NEG 1) stability studies for a duration of 90 d

| Time (days) | pH | Viscosity | Drug content |

| 0 | 6.69±0.06 | 136.52±1.31 | 98.60±0.52 |

| 7 | 6.68±0.05 | 120.55±0.45 | 97.64±0.51 |

| 21 | 6.68±0.04 | 135.56±1.32 | 98.61±0.53 |

| 30 | 5.48±1.07 | 126.51±2.31 | 96.62±0.52 |

| 60 | 6.63± 1.37 | 135.26±0.32 | 97.61±0.53 |

| 90 | 6.68±0.04 | 136.52±1.31 | 98.60±0.52 |

The data is represented as mean±SD, n=3

Ex vivo investigations on drug penetration

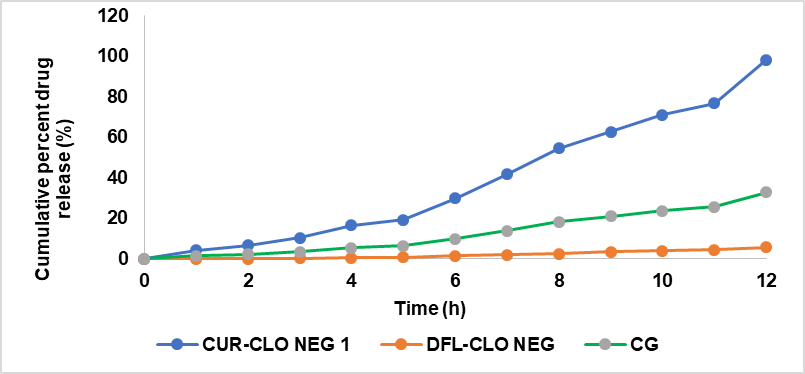

Ex vivo permeation studies were performed to determine the nanoemulgel's permeability. The researchers employed Franz diffusion cells and rat skin in their study. Fig. 4 depicts the ex vivo penetration of curcumin from the CUR-CLO NEG 1, CG, and DFL-CLO NEG. Curcumin penetration from nanoemulgel, drug-free nanoemulgel, and gel was 592.41±1.21, 147.38±1.27, and 318.5±0.69 µg/cm2 respectively. It was discovered that the permeability of curcumin from nanoemulgel increased significantly after 12 h. The diffusion study of CUR-CLO NEG 1 showed a release of 6.76±1.06 % at 2 h, 29.82±0.62 % at 6 h, and 98.25±0.30 for 12 h, while CG and DFL-CLO NEG showed 54.45±1 and 9.62±0.16, respectively. The emulsion's nano-sized droplets improved drug penetration through the epidermal layers. CUR-CLO NEG 1 had a flux (Jss) of 10.68±0.26 µg/cm2. h, twice that of CG (5.82±0.08 µg/cm2. h) and DFL-CLO NEG (2.72±0.02 µg/cm2. h), respectively.

Fig. 4: Ex vivo drug release studies of curcumin nanoemulgel, drug free loaded nanoemulgel, and curcumin plain gel expressed in mean (n=3)

In vitro antimicrobial activity of curcumin nanoemulgel

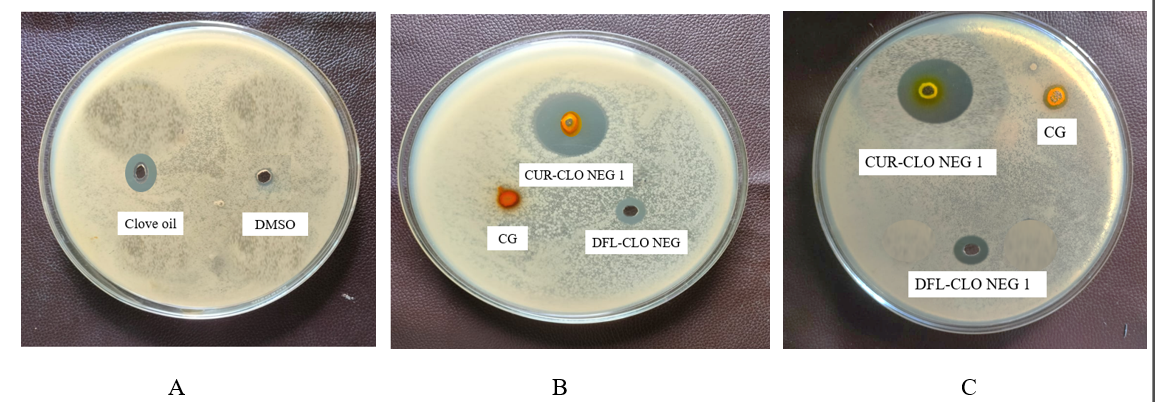

Antibiotic resistance is a significant global issue. As a result, there is an urgent need for the development of novel antibacterial agents [39, 40]. Curcumin has been shown in multiple trials to be safe against gram-positive and gram-negative [41]. This study examined the antibacterial characteristics of curcumin nanoemulgel (CUR-CLO NEG 1), DFL-CLO NEG, and CG against two typical bacterial stains (S. aureus. and E. coli.). While E. coli. is a rod-shaped, Gram-negative bacterium found in wounds, decubitus, and foot ulcers, S. aureus. is a round, Gram-positive bacterium typically found in the body's microbiota. As illustrated in fig. 5A, the inhibition zones for clove oil and DMSO (control) in E. coli were determined to be 9.02±0.37 and 1.25±0.21 mm, respectively.

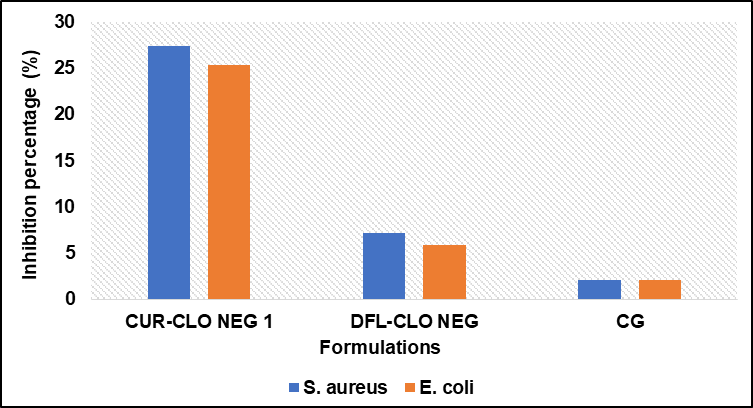

In E. coli, the zone of inhibition for CUR-CLO NEG 1, DFL-CLO NEG, and CG was 25.32±0.54, 5.93± 0.21, and 2.11±0.13 mm, respectively, as illustrated in fig. 5B. In S. aureus, the zone of inhibition was 27.34±0.15, 7.23± 0.51, and 2.15± 0.16 mm, respectively, as illustrated in fig. 5C. The zones' diameters increased during the course of 12 and 24 h. Consequently, curcumin nanoemulgel (CUR-CLO NEG1) showed a 66.67 % increase in the inhibitory zones against E. coli. Compared to DFL-CLO NEG and CG, which showed 33.6% and 0 %, the inhibition percentages for S. aureus were 98.52 %, 54.28 %, and 0 %, as shown in fig. 6. The MIC of CUR-CLO NEG 1, DFL-CLO NEG, and CG showed in S. aureus. It was 120, 142, and 168 µg/ml, whereas for E. coli., the MIC was 125, 163, and 200 µg/ml, as shown in table 3. The results showed that the Gram-positive bacteria were more sensitive than the Gram-negative bacteria. This could be owing to changes in their cell membrane composition and structure. It is known that Gram-positive bacteria have an outer peptidoglycan layer, whereas Gram-negative bacteria have an outer phospholipidic membrane, both of which interact differently when exposed to curcumin. We compared a plain curcumin gel (CG) to a curcumin nanoemulgel (CUR-CLO NEG 1) and drug free loaded nanoemulgel (DFL-CLO NEG). All the formulations were dissolved in DMSO to improve their diffusion into the agar medium. This type of comparison was explicitly designed to investigate the influence of particle size reduction on curcumin solubility and bioefficacy. Since curcumin has a very high solubility in DMSO, the anti-microbial activity of DMSO was also conducted to prove that although it has little anti-bacterial activity, it helped in enhancing the solubility of CUR-CLO NEG 1, hence showing anti-bacterial effect. Since curcumin is insoluble in water, water has never been used as the solvent for solubilizing the curcumin but it has been used in the aqueous phase the formulation of curcumin nanoemulsion. The above studies concluded that CUR-CLO NEG 1 showed better in vitro anti-microbial activity than CG. This is due to the small particle size and diffusion of curcumin from the nanoemulgel, thus improving its activity and efficacy.

Scaling up of curcumin nanoemulgel

Using the spontaneous emulsification approach, curcumin nanoemulgel was scaled up to 1000 ml batch size. The process parameters, such as mixing speed and temperature, were adjusted to ensure consistency in small-scale production. To validate the scale-up, comparison analyses were conducted, including droplet size, zeta potential, viscosity, and stability evaluation studies, which confirmed the formulation's reproducibility. Furthermore, the results show that the 1000 ml batch has the same quality attributes as the lab-scale formulation, with no significant particle size or stability differences. Detailed raw data for these studies and process parameter logs will be available upon request to ensure transparency.

Fig. 5: Inhibition zones of (A) clove oil and DMSO in E. Coli., (B) curcumin nanoemulgel, curcumin gel and drug free loaded nanoemulgel in E. coli. and (C) curcumin nanoemulgel, curcumin gel and drug free loaded in S. aureus

Table 3: Zone of inhibition and MIC of all formulations for S. aureus and E. coli

| Formulations | MIC (µg/ml) | Inhibition zones (mm) | ||

| S. aureus | E. coli | S. aureus | E. coli | |

| CUR-CLO NEG 1 | 120 | 125 | 27.34±0.15 | 25.32±0.54 |

| DFL-CLO NEG | 142 | 163 | 7.23±0.51 | 5.93±0.21 |

| CG | 168 | 200 | 2.15±0.16 | 2.11±0.13 |

| DMSO (control) | 350 | 350 | 1.26±0.18 | 1.25±0.21 |

The data for MIC and inhibition zones are shown as mean where n=3

Fig. 6: Percentage inhibition of curcumin nanoemulgel (CUR-CLO NEG 1), drug free loaded nanoemulgel (DFL-CLO NEG) and curcumin gel (CG) in both S. aureus. and E. coli

DISCUSSION

Nanoemulgel is a cutting-edge drug delivery technology that combines the advantages of nanoemulsions and hydrogels, resulting in increased solubility, stability, and bioavailability for weakly water-soluble medicines such as curcumin. They have drawn much attention for topical drug administration because of their non-greasy texture and simplicity of use, especially in antibacterial therapy, arthritis [42], wound healing, cardiovascular diseases [43], and dermatological treatments. They are a prospective substitute for traditional gels and creams in pharmaceutical and cosmetic formulations because of their capacity to increase the bioavailability of lipophilic medicines while ensuring prolonged release.

The solubility of a drug in excipients is crucial for selecting components for a nanoemulsion formula, particularly the oil phase. The prepared curcumin nanoemulsion fulfilled the requirements suitable for an oil-in-water nanoemulsion. Several studies have examined nanoemulsions and nanoemulgels for curcumin delivery. Priyadarshini et al. [44] developed a posaconazole nanoemulsion with a particle size of 79.1 nm. Similarly, Eid et al. [45] formulated Coriandrum sativum nanoemulgel whose particle size of the nanoemulsion was 162.72 nm, which is substantially more significant than the 30.2±0.11 nm observed in our formulation (CUR-CLO NE 1).

The optimized curcumin nanoemulsion (CUR-CLO NE 1) was added to a gel base to extend its retention period due to its low viscosity, which makes it difficult to retain on the skin. The spreadability and viscosity of CUR-CLO NEG 1 were 18.54±1.63 g. cm/s and 136.52±1.31Cps, respectively. This suggests that CUR-CLO NEG 1 spreads more readily when applied due to optimum viscosity, enhancing patient compliance upon application, which was not in the case of curcumin nanoemulsion gel prepared by Fatease Al et al. [46] and Ritika et al. [47], whose formulation had a higher viscosity of 2200±120.12 Cp and 15480±0.43 respectively which may have spreadability issues upon application to skin.

With a pH of 6.69±0.06, curcumin nanoemulgel is within the acceptable limits for topical preparations and is similar to the values reported by Alhasso et al. with pH 6.0±0.2 [48]. Maintaining a pH close to skin physiology reduces irritation and increases formulation stability. The spreadability of the nanoemulgel was tested to determine the influence of storage temperature and duration on viscosity, pH, separation signals, and organoleptic characteristics. CUR-CLO NEG 1 remained stable after 90 d of exposure to different temperatures, with only a slight decline in viscosity observed after 7 and 60 d due to temperature changes. The ex vivo drug release studies of CUR-CLO NEG 1 showed 98.25±0.30 % of drug release at 12 h and a flux of 10.68±0.26 µg/cm2. h, which was similar to results of curcumin nanoemulgel prepared by Algahtani et al. [27].

Finally, the anti-bacterial activity of curcumin nanoemulgel was determined by both the agar diffusion method and broth dilution method, where the inhibition zones were 27.34±0.15 mm and 25.32±0.32 mm in both S. aureus and E. Coli respectively. The MIC was 120 µg/ml and 125 µg/ml in S. aureus. and E. Coli. Similar results were reported by Bagheri et al. [49], whose curcumin nanoemulgel formulation showed MIC values between 250 µg/ml and 500 µg/ml in the same bacterial strains for its superiority in inhibiting g-positive bacteria (S. aureus.) Our study addresses the superior anti-bacterial activity of curcumin nanoemulgel (CUR-CLO NEG 1) in g-positive bacteria compared to g-negative bacteria, indicating curcumin's effectiveness and therapeutic activity. This is proved by research done by Morão et al., 2018 [50], who studied curcumin's antibacterial properties on Gram-positive bacteria like Bacillus subtilis. Curcumin disrupts bacterial membranes, inhibits cell division, and increases permeability, reducing membrane potential for proteins like FtsZ. It also interacts with FtsZ, altering its polymerization kinetics and preventing the Z-ring development. Compared to curcumin gel (CG) and drug free loaded nanoemulgel (DFL-CLO NEG), curcumin nanoemulgel formulation has higher drug release and better antibacterial action.

This research advances the area by solving the stability and scalability issues many previous formulations encountered. Notably, the spontaneous emulsification process utilized in this study has been found to scale up efficiently to 1000 ml without affecting particle size or formulation stability. Furthermore, unlike previous studies that focused solely on in vitro tests, our research emphasizes the practical application of nanoemulgel formulations, focusing on real-world issues such as formulation stability and ease of scale-up, which can help bridge the gap between research and clinical use.

Future research should explore curcumin's antibacterial properties, enhance formulation stability and efficacy, and conduct clinical trials in humans. Expanding the study to include additional bacterial strains, especially Gram-negative ones, and using new analytical tools like proteomics and transcriptomics could reveal molecular interactions between curcumin nanoemulgel and bacterial cells, enabling more effective formulations and therapeutic strategies.

CONCLUSION

Currently, there is an increasing interest in developing natural therapeutic drugs. Active components of herbal plants, such as curcumin, have received attention because of their significant antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant activities. This work focuses on developing and evaluating a curcumin nanoemulgel for topical usage against two bacterial strains, E. coli and S. aureus. The spontaneous emulsification approach was used to prepare curcumin nanoemulsions, significantly increasing curcumin solubility and therapeutic potential. These data support the idea that curcumin nanoemulgel is suitable for topical bacterial therapy.

ETHICS APPROVAL

The research work was approved by the IAEC committee with proposal no: IAEC/GU-1287/JDS-F/5/December 2023. Both the authors provided informed consent

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Both authors have reviewed the research paper and consented to the manuscript's publication.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA

Data will be available on request

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors are thankful to the University Grants Commission (UGC) for funding through the Savitribai Jyotirao Phule fellowship (grant no-F. No. 82-7/2022(SA-III)) for funding this research work and to the GITAM School of Pharmacy, GITAM Deemed to be University, Visakhapatnam, for providing us with the resources.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

CUR – Curcumin, Smix-Surfactant and cosurfactant mixture, PEG 400-Polyethylene glycol 400, CUR-CLO NE 1-Curcumin nanoemulsion 1, CUR-CLO NE 2-Curcumin nanoemulsion 2, CUR-CLO NE 3-Curcumin nanoemulsion 3, CUR-CLO NE 4-Curcumin nanoemulsion 4, CUR-CLO NEG 1-Curcumin nanoemulgel 1, US FDA-United States Food and Drug Administration, NE – Nanoemulsion, PDI-Polydispersibility index

FUNDING

The authors are thankful to UGC for funding through the Savitribai Jyotirao Phule Single Girl Child Fellowship (SJSGC) with grant number-F. No. 82-7/2022(SA-III)

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Joshna Booravilli designed the study, collected the data, conducted the experiment, and analyzed the data. Janaki Devi Sirisolla has reviewed the manuscript and has been involved equally in all stages of its development.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2022;399(10325):629-55. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02724-0, PMID 35065702.

O Neill J. Tackling drug resistant infections globally: final report and recommendations. London: review on antimicrobial resistance. London; 2016. Available from: https://amr-review.org/sites/default/files/160518_Final%20paper_with%20cover.pdf. [Last accessed on 17 Apr 2025].

O Neill J, Grande B. Antimicrobial resistance: tackling a crisis for the health and wealth of nations. London: review on antimicrobial resistance; 2014. Available from: https://books.co.in/books?id=b1EOkAEACAAJ. [Last accessed on 17 Apr 2025].

Kariuki S. Global burden of antimicrobial resistance and forecasts to 2050. Lancet. 2024 Sep 28;404(10459):1172-3. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01885-3, PMID 39299259.

Aparicio Blanco J, Vishwakarma N, Lehr CM, Prestidge CA, Thomas N, Roberts RJ. Antibiotic resistance and tolerance: what can drug delivery do against this global threat? Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2024 Jun;14(6):1725-34. doi: 10.1007/s13346-023-01513-6, PMID 38341386.

Patra JK, Das G, Fraceto LF, Campos EV, Rodriguez Torres MD, Acosta Torres LS. Nano based drug delivery systems: recent developments and future prospects. J Nanobiotechnology. 2018 Sep 19;16(1):71. doi: 10.1186/s12951-018-0392-8, PMID 30231877.

Sari TP, Mann B, Kumar R, Singh RR, Sharma R, Bhardwaj M. Preparation and characterization of nanoemulsion encapsulating curcumin. Food Hydrocoll. 2015 Jan;43:540-6. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2014.07.011.

Kaur S, Modi NH, Panda D, Roy N. Probing the binding site of curcumin in escherichia coli and bacillus subtilis FtsZ--a structural insight to unveil antibacterial activity of curcumin. Eur J Med Chem. 2010 Sep;45(9):4209-14. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.06.015, PMID 20615583.

Rai D, Singh JK, Roy N, Panda D. Curcumin inhibits FtsZ assembly: an attractive mechanism for its antibacterial activity. Biochem J. 2008 Feb 15;410(1):147-55. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070891, PMID 17953519.

Sharifi S, Fathi N, Memar MY, Hosseiniyan Khatibi SM, Khalilov R, Negahdari R. Anti-microbial activity of curcumin nanoformulations: new trends and future perspectives. Phytother Res. 2020 Aug;34(8):1926-46. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6658, PMID 32166813.

Jeengar MK, Rompicharla SV, Shrivastava S, Chella N, Shastri NR, Naidu VG. Emu oil based nano-emulgel for topical delivery of curcumin. Int J Pharm. 2016 Jun 15;506(1-2):222-36. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2016.04.052, PMID 27109049.

Soliman WE, Shehata TM, Mohamed ME, Younis NS, Elsewedy HS. Enhancement of curcumin anti-inflammatory effect via formulation into myrrh oil based nanoemulgel. Polymers (Basel). 2021 Feb 14;13(4):577. doi: 10.3390/polym13040577, PMID 33672981.

Pandit RS, Gaikwad SC, Agarkar GA, Gade AK, Rai M. Curcumin nanoparticles: physic chemical fabrication and its in vitro efficacy against human pathogens. 3 Biotech. 2015 Dec;5(6):991-7. doi: 10.1007/s13205-015-0302-9, PMID 28324406.

Ahmad N, Ahmad R, Al-Qudaihi A, Alaseel SE, Fita IZ, Khalid MS. Preparation of a novel curcumin nanoemulsion by ultrasonication and its comparative effects in wound healing and the treatment of inflammation. RSC Adv. 2019;9(35):20192-206. doi: 10.1039/c9ra03102b, PMID 35514703.

Ngan CL, Basri M, Lye FF, Fard Masoumi HR, Tripathy M, Abedi Karjiban R. Comparison of box behnken and central composite designs in optimization of fullerene loaded palm based nano emulsions for cosmeceutical application. Ind Crops Prod. 2014 Aug;59:309-17. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2014.05.042.

Gaikwad MT, Marathe RP. Cilnidipine loaded transdermal nanoemulsion based gel: synthesis optimisation characterisation and pharmacokinetic evaluation. Int J App Pharm. 2025;17(1):255-74. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2025v17i1.52689.

Ahmad N, Alam MA, Ahmad FJ, Sarafroz M, Ansari K, Sharma S. Ultrasonication techniques used for the preparation of novel eugenol nanoemulsion in the treatment of wounds healings and anti-inflammatory. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2018;46:461-73. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2018.06.003.

Azhar M, Mishra A. Review of nanoemulgel for treatment of fungal infections. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2024 Sep 1;16(9):8-17. doi: 10.22159/ijpps.2024v16i9.51528.

Ahmad N, Ahmad FJ, Bedi S, Sharma S, Umar S, Ansari MA. A novel nanoformulation development of eugenol and their treatment in inflammation and periodontitis. Saudi Pharm J. 2019 Apr 30;27(6):778-90. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2019.04.014, PMID 31516320.

Mahadev M, Nandini HS, Ramu R, Gowda DV, Almarhoon ZM, Al-Ghorbani M. Fabrication and evaluation of quercetin nanoemulsion: a delivery system with improved bioavailability and therapeutic efficacy in diabetes mellitus. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2022 Jan 5;15(1):70. doi: 10.3390/ph15010070, PMID 35056127.

Rehman A, Iqbal M, Khan BA, Khan MK, Huwaimel B, Alshehri S. Fabrication in vitro and in vivo assessment of eucalyptol loaded nanoemulgel as a novel paradigm for wound healing. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14(9):1971. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14091971, PMID 36145720.

Jain A, Gulbake A, Shilpi S, Jain A, Hurkat P, Jain SK. A new horizon in modifications of chitosan: syntheses and applications. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carrier Syst. 2013;30(2):91-181. doi: 10.1615/critrevtherdrugcarriersyst.2013005678, PMID 23510147.

Betzler DE, Oliveira DE, Siqueira L, Matos AP, Cardoso VD, Villanova JC, Guimaraes BD, Dos Santos EP. Clove oil nanoemulsion showed potent inhibitory effect against candida spp. Nanotechnology. 2019 Oct 18;30(42):425101. doi: 10.1088/1361-6528/ab30c1, PMID 31290755.

Shakeel F, Baboota S, Ahuja A, Ali J, Shafiq S. Celecoxib nanoemulsion for transdermal drug delivery: characterization and in vitro evaluation. J Dispers Sci Technol. 2009;30(6):834-42. doi: 10.1080/01932690802644012.

Ahmad J, Gautam A, Komath S, Bano M, Garg A, Jain K. Topical nano emulgel for skin disorders: formulation approach and characterization. Recent Pat Antiinfect Drug Discov. 2019;14(1):36-48. doi: 10.2174/1574891X14666181129115213, PMID 30488798.

Xiao Y, Chen X, Yang L, Zhu X, Zou L, Meng F. Preparation and oral bioavailability study of curcuminoid loaded microemulsion. J Agric Food Chem. 2013;61(15):3654-60. doi: 10.1021/jf400002x, PMID 23451842.

Algahtani MS, Ahmad MZ, Ahmad J. Nanoemulsion loaded polymeric hydrogel for topical delivery of curcumin in psoriasis. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2020 Oct;59:101847. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2020.101847.

Hettiarachchi SS, Perera Y, Dunuweera SP, Dunuweera AN, Rajapakse S, Rajapakse RM. Comparison of antibacterial activity of nanocurcumin with bulk curcumin. ACS Omega. 2022 Nov 23;7(50):46494-500. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.2c05293, PMID 36570282.

Wayne PA, Clinical and laboratory standards institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 2011. p. 100-21. http://en.journals.sid:ID=450165.Ir/ViewPaper.aspx.

Sadeghi Ghadi Z, Behjou N, Ebrahimnejad P, Mahkam M, Goli HR, Lam M. Improving antibacterial efficiency of curcumin in magnetic polymeric nanocomposites. J Pharm Innov. 2023;18(1):13-28. doi: 10.1007/s12247-022-09619-z.

Shahavi MH, Hosseini M, Jahanshahi M, Meyer RL, Darzi GN. Evaluation of critical parameters for preparation of stable clove oil nanoemulsion. Arab J Chem. 2019;12(8):3225-30. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2015.08.024.

Alam P, Ansari MJ, Anwer MK, Raish M, Kamal YK, Shakeel F. Wound healing effects of nanoemulsion containing clove essential oil. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2017 May;45(3):591-7. doi: 10.3109/21691401.2016.1163716, PMID 28211300.

Bhattacharya S, Prajapati BG. Formulation and optimization of celecoxib nanoemulgel. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2017 Aug 1;10(8):353. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2017.v10i8.19510.

Tang H, Xiang S, LI X, Zhou J, Kuang C. Preparation and in vitro performance evaluation of resveratrol for oral self-microemulsion. Plos One. 2019 Apr 16;14(4):e0214544. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0214544, PMID 30990813.

British Pharmacopoeia. XXX. London: Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency; 2016. p. 741.

Bali V, Ali M, Ali J. Study of surfactant combinations and development of a novel nanoemulsion for minimising variations in bioavailability of ezetimibe. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2010 Apr 1;76(2):410-20. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2009.11.021, PMID 20042320.

Zeng L, Xin X, Zhang Y. Development and characterization of promising cremophor EL-stabilized o/w nanoemulsions containing short chain alcohols as a cosurfactant. RSC Adv. 2017;7(32):19815-27. doi: 10.1039/C6RA27096D.

Ali EM, Mahmood S, Sengupta P, Doolaanea AA, Chatterjee B. Sunflower oil based nanoemulsion loaded into carbopol gel: semisolid state characterization and ex vivo skin permeation. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2023;85(2):388-402. doi: 10.36468/pharmaceutical-sciences.1104.

Zheng D, Huang C, Huang H, Zhao Y, Khan MR, Zhao H. Antibacterial mechanism of curcumin: a review. Chem Biodivers. 2020 Aug;17(8):e2000171. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.202000171, PMID 32533635.

Teow SY, Liew K, Ali SA, Khoo AS, Peh SC. Antibacterial action of curcumin against Staphylococcus aureus: a brief review. J Trop Med. 2016;2016:2853045. doi: 10.1155/2016/2853045, PMID 27956904.

Gunes H, Gulen D, Mutlu R, Gumus A, Tas T, Topkaya AE. Antibacterial effects of curcumin: an in vitro minimum inhibitory concentration study. Toxicol Ind Health. 2016 Feb;32(2):246-50. doi: 10.1177/0748233713498458, PMID 24097361.

Wikantyasning ER, Setiyadi G, Pramuningtyas R, Kurniawati MD, HO YC. Formulation of nanoemulgel containing extract of Impatients Balsamina L. And its antibacterial activity. Int J Appl Pharm. 2023;15(3):67-70. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2023v15i3.4667045.

Gaikwad MT, Marathe RP. Cilnidipine loaded transdermal nanoemulsion based gel: synthesis optimisation characterisation and pharmacokinetic evaluation. Int J App Pharm. 2025 Jan 7;17(1):255-74. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2025v17i1.52689.

Priyadarshini P, Karwa P, Syed A, Asha AN. Formulation and evaluation of nanoemulgels for the topical drug delivery of posaconazole JDDT. 2023;13(1):33-43. doi: 10.22270/jddt.v13i1.5896.

Eid AM, Issa L, Al Kharouf O, Jaber R, Hreash F. Development of coriandrum sativum oil nanoemulgel and evaluation of its antimicrobial and anticancer activity. Bio Med Res Int. 2021 Oct 11;2021:5247816. doi: 10.1155/2021/5247816, PMID 34671674.

Al Fatease A, Alqahtani A, Khan BA, Mohamed JM, Farhana SA. Preparation and characterization of a curcumin nanoemulsion gel for the effective treatment of mycoses. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):22730. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-49328-2, PMID 38123572.

Arora R, Aggarwal G, Harikumar SL, Kaur K. Nanoemulsion based hydrogel for enhanced transdermal delivery of ketoprofen. Advances in Pharmaceutics. 2014;2014:1-12. doi: 10.1155/2014/468456.

Alhasso B, Ghori MU, Rout SP, Conway BR. Development of a nanoemulgel for the topical application of mupirocin. Pharmaceutics. 2023 Sep 26;15(10):2387. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics15102387, PMID 37896147.

Bagheri AM, Ranjbar M, Karami Mohajeri S, Moshafi MH, Dehghan Noudeh YD, Ohadi M. Curcumin nanoemulgel: characterization optimization and evaluation of photoprotective efficacy anti-inflammatory properties and antibacterial activity. J Clust Sci. 2024;35(7):2253-72. doi: 10.1007/s10876-024-02651-8.

Morao LG, Polaquini CR, Kopacz M, Torrezan GS, Ayusso GM, Dilarri G. A simplified curcumin targets the membrane of bacillus subtilis. Microbiology Open. 2019 Apr;8(4):e00683. doi: 10.1002/mbo3.683, PMID 30051597.