Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 3, 2025, 189-199Original Article

IN VITRO ANTIMICROBIAL ACTIVITY OF PUNICA GRANATUM L. EXTRACT AND ANTI-INFLAMMATORY ACTIVITY OF NANO GEL IN VIVO INWISTAR RATS GINGIVA

ARMIA SYAHPUTRA1*, IRMA ERVINA1, AIDA FADHILLA DARWIS2, HAFID SYAHPUTRA3, EMI SARAH NOVITA MARPAUNG1, INDAH JAYANTI SITORUS1, REZA ADITYA1

1Department of Periodontology, Faculty of Dentistry, Universitas Sumatera Utara, Medan-20115 Indonesia. 2Departement of Oral Medicine, Faculty of Dentistry, Universitas Sumatera Utara, Medan, North Sumatera Indonesia. 3Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, Faculty of Pharmacy, Universitas Sumatera Utara, Medan-20115 Indonesia

*Corresponding author: Armia Syahputra; *Email: armia.syahputra@usu.ac.id

Received: 08 Jan 2025, Revised and Accepted: 20 Mar 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: This study evaluates the antimicrobial activity of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) peel extract in vitro and the anti-inflammatory effects of its nano gel formulation in vivo on gingival inflammation in male wistar rats.

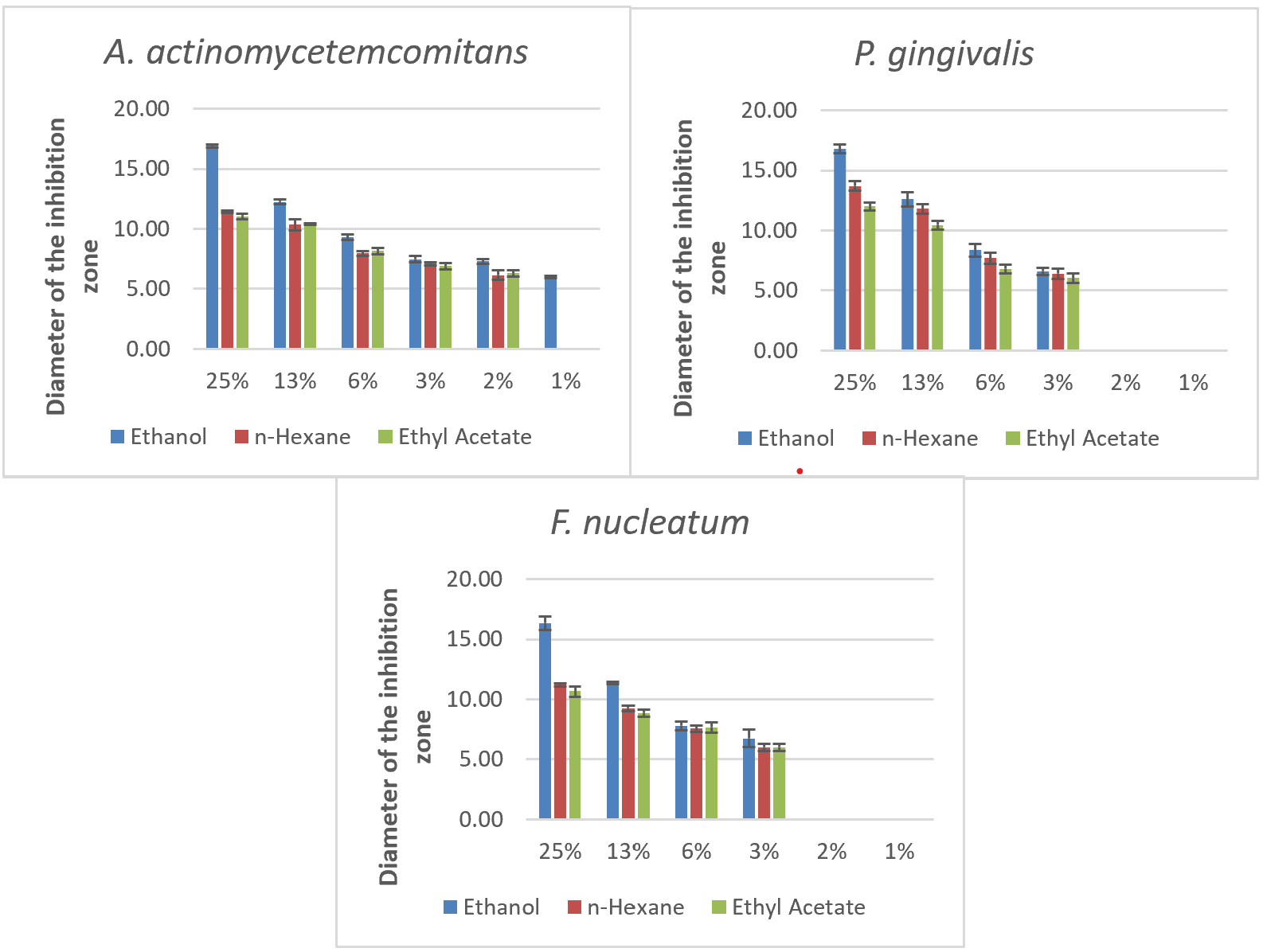

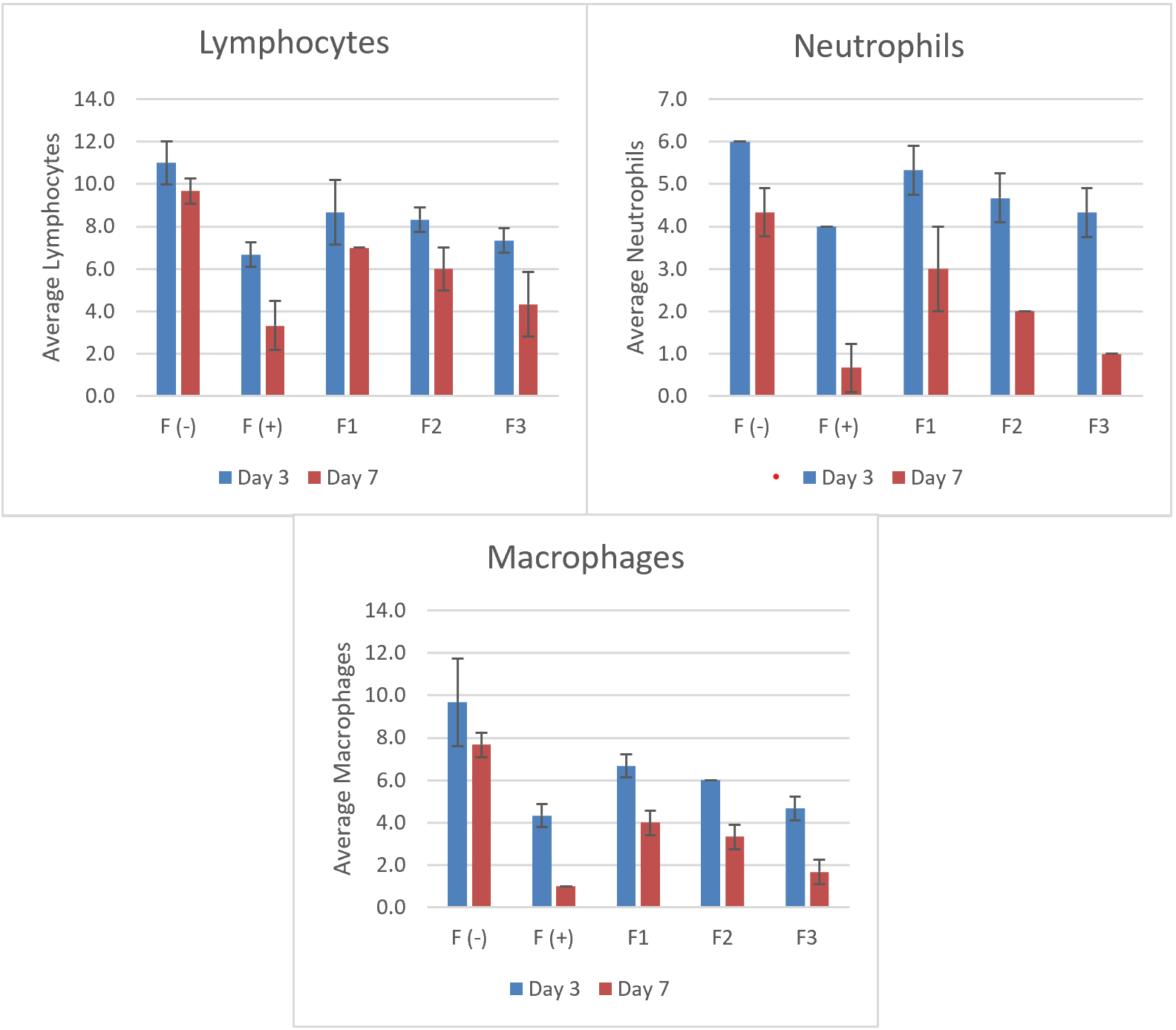

Methods: The antimicrobial activity was tested against Aggregatibacteractinomycetemcomitans, Porphyromonasgingivalis, and Fusobacterium nucleatum using ethanol, ethyl acetate, and n-hexane extracts at concentrations of 0.8–25%. The anti-inflammatory effect was assessed using pomegranate peel extract nano gel (6.25%, 12.5%, and 25%) in a ligature-induced gingivitis model in Wistar rats, with Gengigel as a positive control. Evaluation parameters included inhibition zone diameters for antimicrobial activity, while histological analysis of lymphocyte, neutrophil, and macrophage counts was conducted on days 3 and 7 to assess anti-inflammatory effects.

Results: The 25% ethanol extract exhibited the highest antimicrobial inhibition zones (16.95 mm for A. actinomycetemcomitans, 16.83 mm for P. gingivalis, and 16.35 mm for F. nucleatum, p<0.05). The 25% nano gel formulation significantly reduced inflammatory cell counts compared to the control (p<0.05), showing reductions in lymphocytes (4.33±1.53), neutrophils (1.00±0.00), and macrophages (1.67±0.57) by day 7.

Conclusion: Pomegranate peel extract demonstrated potent antimicrobial properties, especially in ethanol-based formulations. The nano gel formulation exhibited significant anti-inflammatory effects, with the 25% concentration proving the most effective in reducing gingival inflammation. These findings highlight its potential as a natural therapeutic agent for periodontal disease management.

Keywords: Anti-inflammatory, Antimicrobial activity, Gingivitis, Nano gel, Punica granatum L

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i3.53619 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, the growing interest in natural ingredients for medicinal purposes has been primarily driven by the "back-to-nature" movement and the economic challenges that have reduced purchasing power. Numerous studies have demonstrated the potential of these natural ingredients as effective antimicrobial, antibacterial, and anti-inflammatory agents, providing affordable and sustainable alternatives to synthetic drugs. Among the most promising of these ingredients is pomegranate (Punica granatum L.), particularly its peel, which is rich in bioactive compounds such as flavonoids, phenolic acids, tannins, anthocyanidins, ellagic acid, quercetin, gallic acid, catechins, and vitamin C. These compounds are concentrated in the peel, making it a potent source of polyphenols like ellagitannins and ellagic acid. These bioactive components exhibit potent anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antibacterial properties. Furthermore, utilizing pomegranate peel, often discarded as waste, offers environmental benefits by transforming waste into a valuable product [1-3].

Inflammation is a complex immune response involving various immune cells, such as lymphocytes, neutrophils, and macrophages, along with inflammatory mediators such as cytokines and chemokines. When this response occurs in the gingival tissue, it causes gingivitis, a condition generally characterized by swelling, redness, and bleeding of the gums [4]. This inflammation is often exacerbated by pathogenic bacteria such as Aggregatibacteractinomycetemcomitans, Porphyromonasgingivalis, and Fusobacterium nucleatum, which play essential roles in the onset and progression of periodontal diseases, including gingivitis and periodontitis [5, 6].

These bacteria trigger and exacerbate the immune response in the gingival tissue. A. actinomycetemcomitans releases toxins that cause immune cell infiltration and tissue damage, while P. gingivalis interferes with immune regulation, leading to chronic inflammation. F. nucleatum, which often acts as a bridge organism, facilitates colonization by other pathogens, further amplifying the inflammatory response. Together, these pathogens contribute to periodontal tissue destruction, leading to progressive destruction of the periodontal ligament and alveolar bone, which can worsen if left untreated [7].

The inflammatory process begins with neutrophil infiltration within 24–48 h of bacterial invasion, followed by macrophages replacing the neutrophils and clearing debris. Lymphocytes then migrate to the inflamed area, peaking on the third day and gradually decreasing after the fifth day. This immune response is further exacerbated by pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6, released in response to these pathogens [8, 9]. If left untreated, the ongoing inflammatory response destroys gingival tissue and can lead to periodontitis.

Current treatment of gingivitis involves mechanical plaque removal and maintaining proper oral hygiene practices. However, certain patients, particularly those with physical disabilities or plaque retention factors such as dental caries or ill-fitting crowns, find it challenging to maintain good oral hygiene. Additional therapeutic approaches have been developed to address this, including using antiplaque and anti-inflammatory agents in toothpaste, mouthwashes, or gels. These agents can support mechanical plaque removal and reduce inflammation [10]. Despite these interventions, many conventional formulations have bioavailability, retention time, and targeted delivery limitations, necessitating exploring alternative drug delivery systems that can enhance treatment efficacy.

Recent advances in drug delivery systems, such as nano gel, offer a promising approach to enhancing the efficacy of topical treatments. Nano gels are hydrogels with particle sizes ranging from 1 to 1000 nm, capable of encapsulating and protecting drug molecules. Due to their biocompatibility and high water content, nano gels facilitate the targeted delivery of active compounds to tissues while minimizing premature drug release. This makes nano gels particularly effective for delivering anti-inflammatory agents, including natural products such as pomegranate peel extract [11–14]. Previous studies have demonstrated that nanoformulations improve drug retention and controlled release in periodontal therapy. Solanum nigrum-based selenium nanoparticles and lycopene-chitosan nanoformulations have shown superior anti-inflammatory activity in vitro, highlighting their potential in periodontitis management. Furthermore, nano gel formulations have been explored for sustained drug delivery in gingival applications, proving their efficacy in reducing inflammation and enhancing bioadhesion, thus improving treatment outcomes in periodontal disease. These findings reinforce the role of nano gels as an optimized delivery system for targeted gingival inflammation therapy [15, 16].

This study evaluates the antimicrobial potential of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) peel extract and its nano gel formulation as an anti-inflammatory agent for gingivitis treatment. While pomegranate peel extract has known antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties, its application in gingival therapy remains limited, especially in a nano gel system for controlled and sustained drug release. To address this gap, this study assesses its antimicrobial activity against Aggregatibacteractinomycetemcomitans, Porphyromonasgingivalis, and Fusobacterium nucleatum using various solvents (ethanol, ethyl acetate, and n-hexane), followed by in vivo testing of a nano gel formulation in a ligature-induced gingivitis model in male Wistar rats. Key inflammatory markers, including lymphocytes, neutrophils, and macrophages, were evaluated. By integrating pomegranate peel extract into a nano gel system, this study aims to enhance bioavailability, retention, and targeted therapeutic effects, offering a natural alternative for gingivitis treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals, reagents, and equipment

All chemicals, reagents, and diagnostic kits were obtained from reputable suppliers and used per manufacturer guidelines. Pomegranate peel (Punica granatum L.) was sourced from a local supermarket in Medan, Indonesia. Extraction used ethanol, ethyl acetate, and n-hexane, while nano gel formulation included Carbopol 940, HPMC K4M (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), TEA (Merck, Germany), glycerin (Brataco, Indonesia), Nipagin, and Nipasol (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) in distilled water. Nutrient Agar (NA) and Nutrient Broth (NB) (Seaweed Solution Laboratories) were used for bacterial culture, and strains of A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, and F. nucleatum obtained from the microbiology laboratory of the medical faculty of the university Sumatera Utara. HandE staining kits (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) were used for histological analysis, with tissue preserved in 10% formalin (Merck, Germany). Equipment included a rotary evaporator (Heidolph, Germany), a freeze dryer for sample processing, Petri dishes, micropipettes, and vortex mixers for bacterial testing.

Preparatıon and characterization extract

Fresh pomegranate peel (Punica granatum L.) was washed, dried, and ground into a powder, with its botanical identity confirmed and registered under voucher specimen number 283/MEDA/2024. A 500 g sample underwent successive percolation extraction using n-hexane, ethyl acetate, and 70% ethanol to obtain extracts with different bioactive compound profiles. N-hexane extracted non-polar compounds, ethyl acetate targeted semi-polar compounds like some polyphenols, while ethanol, a polar solvent, maximized the extraction of flavonoids, phenolic acids, and tannins, which are known for their antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties. Each extraction lasted 24 h, and the percolate was concentrated using a rotary evaporator at ≤40 °C before freeze-drying. The extracts were then tested for antimicrobial activity against A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, and F. nucleatum, revealing that ethanol extract showed the highest inhibition zones, indicating superior antimicrobial efficacy. Based on these results, ethanol was selected as the extraction solvent for the active ingredient in the nano gel formulation. The final extract was subjected to phytochemical screening and FTIR analysis [17].

Preparation of extract nano gel

The selection of nano gel concentrations (6.25%, 12.5%, and 25%) was based on preliminary antibacterial testing and formulation feasibility. Initially, pomegranate peel extract was prepared at six concentrations (25%, 12.5%, 6.25%, 3.125%, 1.6125%, and 0.8%) through serial dilution in nutrient broth. These concentrations were tested for antibacterial activity, and the three most effective concentrations (25%, 12.5%, and 6.25%) were chosen for nano gel formulation. Further formulation trials revealed that concentrations exceeding 25% failed to achieve the desired gel consistency and did not meet critical evaluation parameters such as pH stability, viscosity, and particle size distribution. Therefore, the selected concentrations represent the optimal balance between antibacterial efficacy and formulation stability, ensuring a nano gel with suitable physicochemical properties for gingival application.

Before designing the nano gel formula, the gel formula is first oriented to obtain the best material composition for this nano gel [18]. The pomegranate peel extract nanogel formulationis detailed in table 1 below.

Table 1: Formulation of pomegranate peel extract nanogel preparations

| Material | Formula | ||

| F1 | F2 | F3 | |

| Pomegranate peel extract(g) | 6.25 | 12.5 | 25 |

| Carbopol940(g) | 0.625 | 0.625 | 0.625 |

| HPMCK4M(g) | 0.625 | 0.625 | 0.625 |

| TEA(g) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Gliserin(g) | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Nipagin(g) | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Nipasol(g) | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Aquadesad (g) | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Nanogel evaluation

The nanogel evaluation involved several physical tests to determine its characteristics, including particle size, organoleptic properties, homogeneity, pH, viscosity, and spreadability. Particle size was measured using a particle size analyzer (Fritsch Analysette 22 NanoTec) for each formulation. Organoleptic properties, including shape, color, and odor, were assessed through visual and olfactory observation of the nanogel. Homogeneity was tested by applying a sample to glass or transparent material to ensure uniform distribution without visible coarse particles. The pH was measured using a pH meter (AZ Instrument 86502), with readings indicating the acidity or alkalinity of each nano gel preparation. Viscosity was evaluated with an NDJ-8S viscometer, using 100 g of nano gel on spindle 4 at a set speed to determine consistency and flow characteristics. Spreadability was assessed by placing 1 g of nano gel in the center of a 20×20 cm glass plate with a millimeter grid, allowing it to sit for 60 seconds, and then measuring the diameter of the spread. Additional measurements were taken by placing protective plastic over the sample and applying 100 g and 150 g weights for another 60 seconds before recording the spread diameter [18].

In vitro antibacterial activity

The pomegranate peel extract was prepared and diluted to target concentrations by dissolving 1.25 g of extract in 5 ml of nutrient broth to obtain a 25% solution, followed by serial dilution to achieve concentrations of 12.5%, 6.25%, 3.125%, 1.6125%, and 0.8%. Nutrient agar was prepared by dissolving 28 g of nutrient agar powder in 1,000 ml of distilled water, heated to boiling, and sterilized at 121 °C under 2 atm pressure for 15 min. The sterilized medium was cooled and stored at 4 °C until use. Bacterial strains (Aggregatibacteractinomycetemcomitans, Porphyromonasgingivalis, and Fusobacterium nucleatum) were cultured in anaerobic conditions at 37 °Cand bacterial suspensions were standardized to 0.6 McFarland (1×10⁶ CFU/ml) using 0.9% NaCl solution to ensure uniform inoculum density. The bacterial suspensions were spread evenly onto nutrient agar plates, and sterile paper discs were placed on the agar surface. Each disc was loaded with 10 µl of pomegranate peel extract at its respective concentration, followed by a drying period of 15–20 min before incubation in a CO₂ incubator at 37 °C for 18–24 h. A negative control (sterile disc with distilled water) was included to confirm that any observed bacterial inhibition was due to the extract and not the solvent alone, ensuring the validity of the antimicrobial findings. After incubation, the inhibition zones were measured using a caliper, ensuring consistent readings from the edge of the clear zone to the edge of bacterial growth. All tests were conducted in quadruplicate to ensure reproducibility, and the average inhibition zone diameters were recorded for further statistical analysis [6, 19].

Preparation of test animals and in vivo anti-inflammatory activity

The study was conducted following ethical approval from the Health Research Ethics Committee of Universitas Sumatera Utara (No. 225/KEPK/USU/2024). Male Wistar rats (Rattus norvegicus), aged 3–4 mo and weighing 150–200 g, were obtained from the Animal House of the Faculty of Pharmacy, Universitas Sumatera Utara. All animals were acclimated to the experimental environment for 7 days under controlled conditions: temperature (22±2 °C), humidity (50±10%), and a 12-hour light/dark cycle. Rats were housed in cages with free access to standard laboratory chow and water.

The sample size was determined using Federer's formula, resulting in 25 rats divided into five groups (n = 5 per group). The study included 25 rats divided into five groups: a negative control (aquades application), a positive control (Gengigel treatment), and three treatment groups receiving pomegranate peel extract nano gel at concentrations of 25%, 12.5%, and 6.25%. Randomization was performed using a computer-generated random number table to allocate rats into groups, ensuring an unbiased distribution.

Procedures for inducing gingival inflammation were conducted under aseptic conditions to ensure animal welfare. Rats were anesthetized with 0.2 ml of intramuscular ketamine before a ligature wire was placed around the cervix of the first incisor of the mandibular to induce gingival inflammation without irritating. The plaque was removed using a cotton roll, and treatments were applied daily to the subgingival area on the labial side for 7 d. Gengigel was selected as the positive control due to its hyaluronic acid content, which promotes wound healing and modulates inflammation, serving as a benchmark for comparison. The negative control (aquades) was used to assess the natural progression of inflammation without treatment, providing a baseline for evaluating the anti-inflammatory effects of both Gengigel and the pomegranate peel extract nano gel. Humane endpoints were continuously monitored to minimize suffering throughout the study. On the third and seventh days post-treatment, rats were euthanized, and mandibular tissue samples were collected for histological analysis to evaluate lymphocyte, neutrophil, and macrophage counts, determining the anti-inflammatory efficacy of the nano gel [20, 21].

Histological preparation of lower jaw tissue

The lower jaw separation and histological analysis began with euthanizing the rats via cervical dislocation, followed by severing the neck with surgical scissors. The lower jaw was isolated using scissors, and all remaining tissue was carefully removed with a scalpel. After thoroughly cleaning with water to remove blood and muscle remnants, the jaw segment was dried and immersed in 10% formalin for 24 h for preservation. Each jaw segment underwent decalcification for histological preparation to soften the bone for easier sectioning, followed by placement in cassettes for processing. The tissue then passed through a series of fixation, dehydration, clearing, and imgding steps. Fixation was achieved with 10% formalin to maintain tissue integrity, while dehydration involved successive immersion in 70%, 80%, 95%, and 100% alcohol to remove water. The clearing was done with xylol to eliminate residual dehydrates, and tissues were imgded in molten paraffin for stability.

Once the paraffin block solidified, it was trimmed to a 2 mm margin and sectioned with a microtome to a thickness of 6-10 microns. Sections were floated on a 46 °C water bath to flatten, mounted onto polylysine-coated glass slides, and dried on a hotplate at 58 °C-60 °C for 15-30 min. For staining, sections were treated with xylol to dissolve paraffin and rehydrated through alcohol washes and water rinses. They were stained with Mayer's hematoxylin for 15 min to delineate cellular structures, followed by eosin for 15 seconds to 2 min to provide contrast. The stained slides were dehydrated and cleared through graded alcohols and xylol, ensuring the tissue's visibility under a microscope for analysis. This procedure enabled precise examination of the gingival tissue's cellular and structural integrity in response to treatment [22, 23].

Observation and lymphocyte, neutrophil, and macrophage count analysis

Histological preparations were examined under a binocular microscope at 400x magnification. Cell counts for lymphocytes, neutrophils, and macrophages were performed systematically across three fields of view for each sample, beginning from the left and moving horizontally and vertically to ensure all areas were observed. The average count for each cell type was calculated by averaging the counts from the three fields, providing an accurate measure of cell presence in each sample [24].

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version XX (replaced with the actual version used). Data normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and variance homogeneity was evaluated with Levene's test, revealing that the data were not normally distributed (p<0.05), necessitating non-parametric tests. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare inhibition zone diameters among different extract concentrations and solvents (ethanol, ethyl acetate, and n-hexane), followed by Dunn's post-hoc test for pairwise comparisons. Similarly, for the in vivo anti-inflammatory study, lymphocyte, neutrophil, and macrophage counts were analyzed using Kruskal-Wallis, with the Mann-Whitney U test applied for pairwise comparisons. To strengthen result interpretation, effect sizes (η² for Kruskal-Wallis, Cohen's d for Mann-Whitney U) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported alongside p-values, with statistical significance set at p<0.05. All statistical methods were selected based on data distribution to ensure robust and reliable conclusions.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Preparatıon and characterization extract

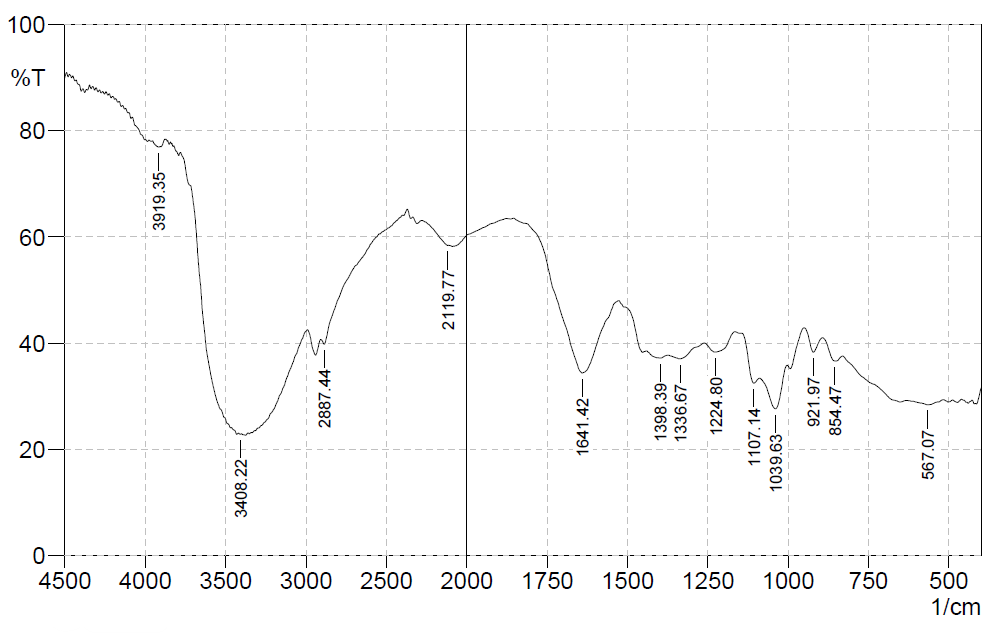

The results of the phytochemical screening of simplicia and extracts are presented in table 2, while the FTIR spectrum of the pomegranate peel extract is shown in fig. 1, highlighting the functional groups responsible for the bioactive compounds identified.

Phytochemical screening results showed that pomegranate peel extract contains flavonoids, saponins, glycosides, and tannins, while alkaloids, steroids, and triterpenoids were undetected. The presence of compounds, such as flavonoids, saponins, glycosides, and tannins, indicates the potential for significant antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory activities. The FTIR spectrum supports these phytochemical screening results by showing relevant peaks, such as the peak at 3408.22 cm⁻¹ indicating the presence of O-H groups, and the peak at 1641.42 cm⁻¹ indicating carbonyl bonds (C=O), confirming the presence of flavonoids and tannins. In addition, the peaks in the 854.47 cm⁻¹ and 567.07 cm⁻¹ indicate aromatic structures, common in polyphenolic compounds and tannins [25].

Evaluation test

This study evaluated the quality of pomegranate peel extract nano gel preparations, including organoleptic tests, homogeneity, pH, viscosity, spreadability, and particle size analysis. The results of these evaluations are summarised in table 3.

Table 2: Phytochemical screening

| No | Compound classes | Ethanol extract |

| 1 | Flavonoid | + |

| 2 | Saponin | + |

| 3 | Alkaloids | - |

| 4 | Glycosides | + |

| 5 | Tannin | + |

| 6 | Steroids and triterpenoids | - |

Description:+: Presence of compound, -: Absence of compound

Fig. 1: FTIR spectrum

Table 3: Nano gel evaluation test

| Parameter | F1 (6.25%) | F2 (12.5%) | F3 (25%) |

| Color | Brown | Brown | Brown |

| Smell | Typical smell | Typical smell | Typical smell |

| Consistency | Semisolid | Semisolid | Semisolid |

| Homogeneity | Homogeneous | Homogeneous | Homogeneous |

| pH | 6.56±0.21 | 6.56±0.11 | 6.56±0.06 |

| Viscosity (mPas) | 3603±4.56 | 2788±7.28 | 2821±5.49 |

| Spreadability (cm) | 5.5±0.1 (100g). 5.9±0.1 (150g) | 6.0±0.1(100g). 6.5±0.1 (150g) | 6.0±0.1 (100g). 7.0±0.1 (150g) |

| Particle size (nm) | 465±0.55 | 904±0.49 | 849±0.58 |

The organoleptic evaluation of the pomegranate peel nano gel formulations (6.25%, 12.5%, and 25%) showed consistent physical characteristics across all concentrations, including a brown color, distinctive smell, and semisolid consistency, making them suitable for topical application. These formulations displayed good homogeneity with no visible coarse particles, ensuring an even distribution of active ingredients. The pH analysis revealed a stable value of 6.56 for each formulation, aligning with the physiological pH range (4.5-7.5), which minimizes the risk of skin or mucosal irritation [26, 27].

Viscosity, a critical parameter influencing gel consistency and application ease, was measured using an NDJ-8S viscometer. The viscosity values ranged from 2,788 to 3,603 mPas, appropriate for semisolid applications (2,000-50,000 mPas). This range provides a balanced consistency that allows smooth, even application on gingival tissue without excessive fluidity or stiffness. The spreadability test further confirmed the practicality of the nano gels for topical use, with measurements ranging from 5.5 to 7.0 cm under 100 g and 150 g loads, falling within the ideal range for semisolids. This spreadability ensures that the nano gel can be applied evenly and retains an optimal layer over the treatment area [26, 27].

Particle size analysis showed the nano gels had sizes of 465 nm (6.25%), 904 nm (12.5%), and 849 nm (25%), all within the acceptable range for nano gel systems (1-1000 nm). Smaller particles, as in the 6.25% formulation, offer better penetration and faster drug release due to their higher surface area-to-volume ratio, whereas the larger particles in the 12.5% and 25% formulations support a more sustained release, beneficial for prolonged anti-inflammatory effects. Nano gels' biocompatibility and high water content enhance drug solubility and bioavailability, making them highly effective for controlled topical drug delivery. This design optimizes therapeutic benefits while minimizing toxicity risk [26, 27].

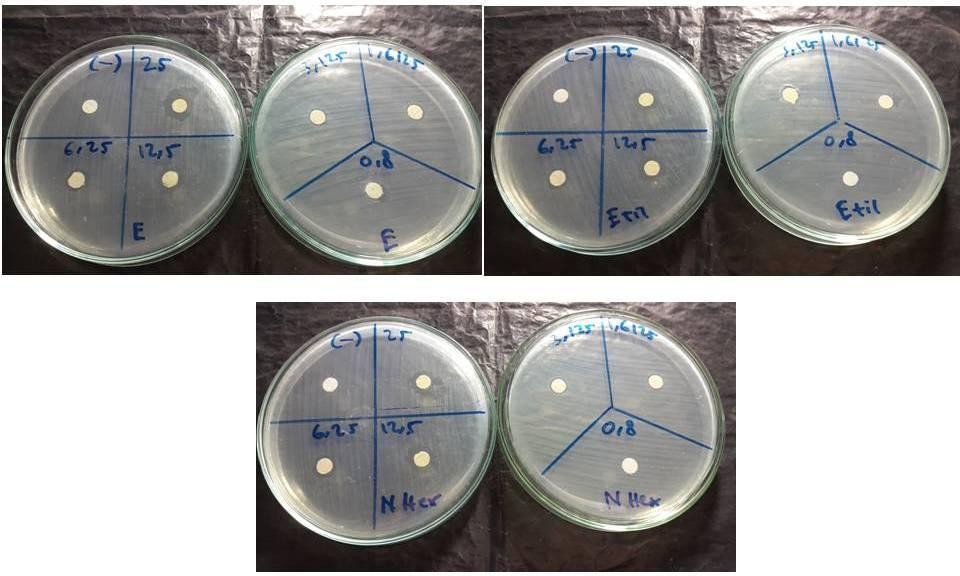

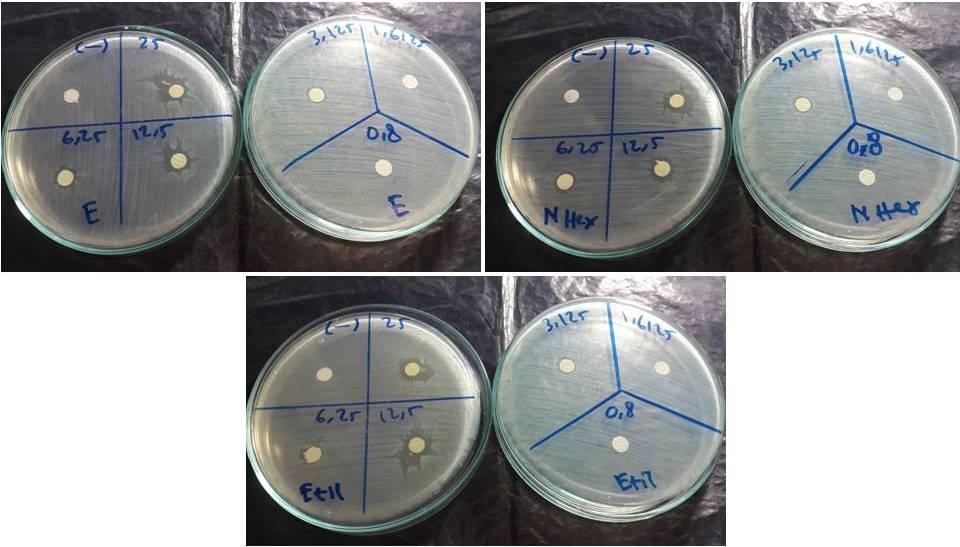

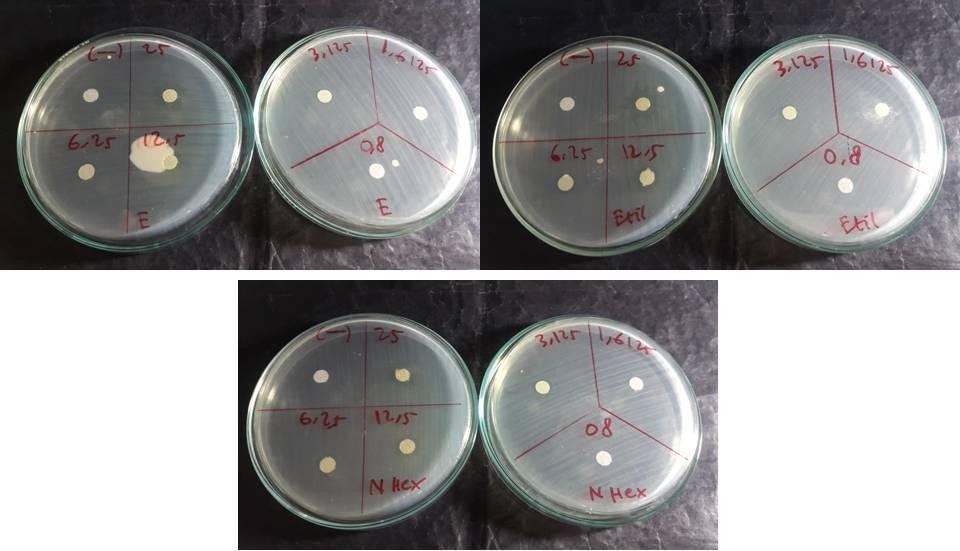

In vitro antibacterial activity

The effectiveness of pomegranate peel extract at concentrations of 25%, 12.5%, 6.25%, 3.125%, 1.6125%, and 0.8% was tested against A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, and F. nucleatum using ethanol, ethyl acetate, and n-hexane as solvents. The diameter of the inhibition zone around each concentration and solvent combination was measured to assess the antimicrobial activity, with larger diameters indicating greater effectiveness in inhibiting bacterial growth. The results of these measurements are summarised in table 4 and fig. 5, and inhibition zones for each bacteria and concentration are illustrated in fig. 2, 3, and 4.

Fig. 2: Diameter of inhibition zone of extract on A. actinomycetemcomitans

Fig. 3: Diameter of inhibition zone of extract on P. gingivalis

Fig. 4: Diameter of inhibition zone of extract on F. nucleatum

The inhibition zone diameters for A. actinomycetemcomitans, the 25% ethanol extract produced the highest inhibition zone of 16.90 mm. In contrast, n-hexane and ethyl acetate at the same concentration yielded inhibition zones of 11.45 mm and 11.05 mm, respectively. Lower concentrations showed progressively smaller inhibition zones, with no inhibition detected at 0.8% concentration. This suggests that ethanol as a solvent enhances the antimicrobial efficacy of pomegranate peel extract, particularly at higher concentrations, potentially due to its effectiveness in dissolving a broad range of bioactive compounds present in the extract. Ethanol's high polarity likely facilitates the extraction of polar compounds, which may contribute to the antibacterial activity against A. actinomycetemcomitans [22, 28].

Table 4: The diameter of the inhibition zone of each concentration of extract with ethanol, n-hexane, ethyl acetate

| Extract concentration | A. actinomycetemcomitans | P. gingivalis | F. nucleatum | ||||||

| Ethanol | n-hexane | Ethyl acetate | Ethanol | n-hexane | Ethyl acetate | Ethanol | n-hexane | Ethyl acetate | |

| 25% | 16.90±0.12 | 11.45±0.1 | 11.05±0.25 | 16.8±0.35 | 13.7±0.4 | 12±0.35 | 16.35±0.55 | 11.2±0.15 | 10.67±0.43 |

| 13% | 12.25±0.19 | 10.35±0.48 | 10.4±0.07 | 12.6±0.6 | 11.8±0.38 | 10.45±0.37 | 11.35±0.1 | 9.25±0.25 | 8.85±0.30 |

| 6% | 9.30±0.22 | 7.95±0.17 | 8.15±0.25 | 8.35±0.53 | 7.7±0.45 | 6.8±0.35 | 7.8±0.38 | 7.55±0.25 | 7.67±0.42 |

| 3% | 7.47±0.26 | 7.1±0.15 | 6.9±0.27 | 6.6±0.3 | 6.4±0.45 | 6.05±0.4 | 6.75±0.75 | 6.0±0.3 | 6.00±0.30 |

| 2% | 7.30±0.20 | 6.15±0.4 | 6.3±0.28 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0±0 |

| 1% | 6.00±0.09 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0±0 |

n = 3; values are expressed as mean±SD

Fig. 5: Inhibition zones of pomegranate peel extract against periodontal pathogens using different solvents and concentrations, n = 3, values are expressed as mean±SD

In testing P. gingivalis, a similar trend was observed, with the 25% ethanol extract showing the largest inhibition zone of 16.8 mm, followed by n-hexane at 13.7 mm and ethyl acetate at 12 mm. At a lower concentration of 12.5%, the ethanol extract maintained substantial activity (12.6 mm), although it decreased with n-hexane (11.8 mm) and ethyl acetate (10.45 mm). The inhibition effect diminished with lower concentrations, with no inhibition observed at 1.6125% and 0.8%. These results indicate that the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for P. gingivalis with ethanol is 3.125%, while n-hexane and ethyl acetate are less effective at this concentration. Ethanol's higher efficacy in this context suggests that it is more effective in preserving or extracting antimicrobial agents from pomegranate peel, leading to increased bacterial inhibition [6, 19].

In testing For F. nucleatum, the 25% ethanol extract again demonstrated the highest inhibition zone at 16.35 mm, with n-hexane and ethyl acetate following at 11.2 mm and 10.67 mm, respectively. Lower concentrations exhibited reduced effectiveness, with no inhibition at 1.6125% and 0.8%. The MIC for ethanol against F. nucleatum was also identified at 3.125%, while higher concentrations were required for n-hexane and ethyl acetate. This pattern suggests that ethanol's solvent properties enhance the extract's bioavailability and bioactivity, maximizing its antimicrobial potential at higher concentrations [6, 19].

Ethanol emerged as the most effective solvent across all tested bacteria, producing the most significant inhibition zones, especially at the 25% concentration. This may be attributed to ethanol's ability to extract a broader range of polar bioactive compounds from pomegranate peel, which are likely responsible for the antibacterial properties. In comparison, n-hexane and ethyl acetate showed limited efficacy, likely due to their lower polarity and restricted ability to dissolve certain active compounds. The MIC for ethanol was lowest for A. actinomycetemcomitans at 0.8%, indicating this bacterium's higher sensitivity to the extract. For P. gingivalis and F. nucleatum, the MIC was 3.125% in ethanol, with n-hexane and ethyl acetate showing higher MICs for all bacteria, further supporting ethanol's superior solubilizing capacity [28, 29].

In vivo anti-inflammatory activity

The anti-inflammatory effect of pomegranate peel extract (Punica granatum L.) nanogel on gingival tissue was investigated by measuring lymphocyte, neutrophil, and macrophage cell counts in male wistar rats. This study assessed how different concentrations of pomegranate peel extract nanogel (6.25%, 12.5%, and 25%) influenced cellular inflammatory markers over twotime points: the third and seventh days following induction of gingival inflammation with a ligature. The results provide insight into the dose-dependent anti-inflammatory properties of pomegranate peel extract and its potential as a natural anti-inflammatory agent.

Thirty male wistar rats were divided into five groups, each consisting of six rats. The groups included a negative control (receiving no active treatment), a positive control (treated with Gengigel, a hyaluronic acid-based gel known for its anti-inflammatory effects), and three treatment groups with pomegranate peel extract nano gel at concentrations of 6.25%, 12.5%, and 25%. Gingival inflammation was induced by placing a ligature wire around the cervical region of the mandibular incisor, which remained in place for seven days to promote a stable inflammatory response. This ligature placement generated plaque accumulation, promoting ulceration and triggering periodontal tissue breakdown, thereby mimicking chronic inflammatory conditions suitable for studying anti-inflammatory agents.

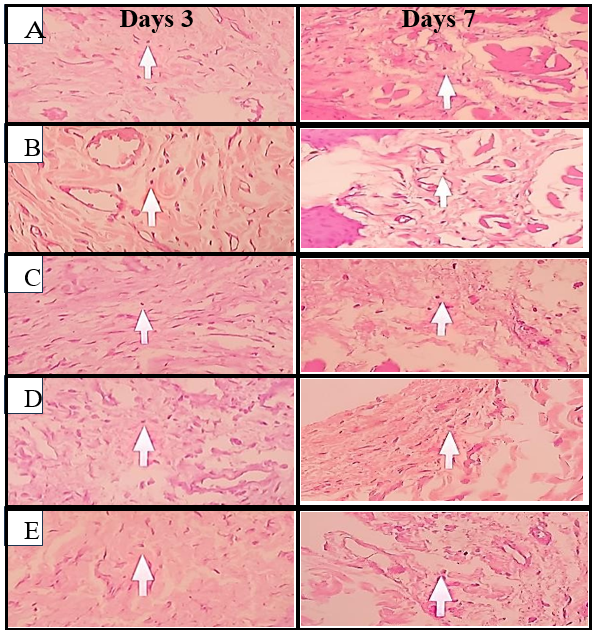

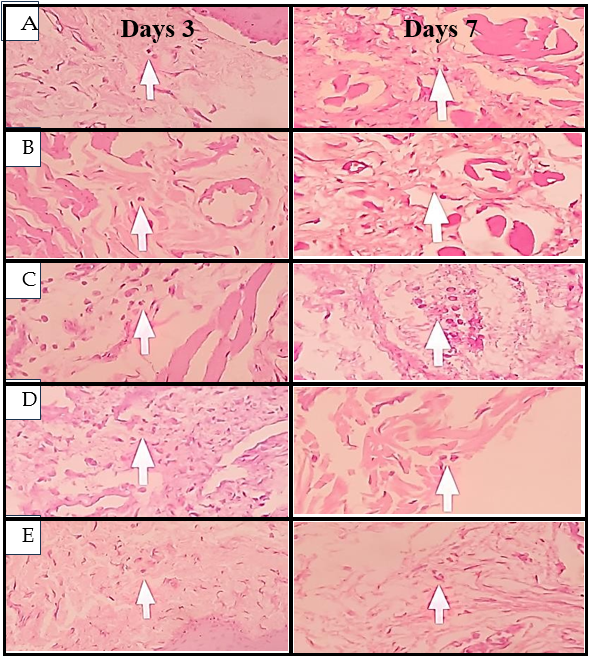

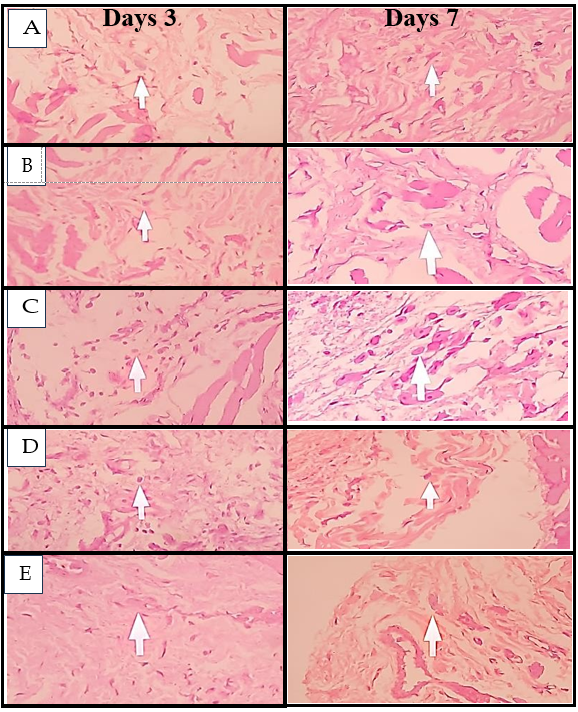

Histological evaluation of lymphocyte, neutrophil, and macrophage cell counts was conducted at 400x magnification on days 3 and 7. The characteristics of each cell type facilitated precise identification: lymphocytes were identified by their round heterochromatic nuclei and limited cytoplasm, neutrophils by their multi-lobed nuclei and presence of pink or purple granules, and macrophages by their irregular nuclear shapes and larger cell bodies. Cell counts were taken across three fields of view to obtain an accurate mean count per sample. The data presented in table 5summarise the mean cell counts of lymphocytes, neutrophils, and macrophages for each group on days 3 and 7, and significant differences between treatment groups were identified using the Kruskal-Wallis test, with further comparisons made using the Mann-Whitney U test where appropriate. Images showing the presence of cells can be seen in the fig. below [22, 23].

Fig. 6: Histological images of lymphocyte cells on days 3 and 7, (A) Negative control, (B) Positive control, (C) Pomegranate peel extract nano gel 6.25%, (D) Pomegranate peel extract nano gel 12.5%, (E) Pomegranate peel extract nano gel 25%

Fig. 7: Histological images of neutrophil cells on days 3 and 7, (A) Negative control, (B) Positive control, (C) Pomegranate peel extract nano gel 6.25%, (D) Pomegranate peel extract nano gel 12.5%, (E) Pomegranate peel extract nano gel 25%

Fig. 8: Histological images of macrophage cells on days 3 and 7, (A) Negative control, (B) Positive control, (C) Pomegranate peel extract nano gel 6.25%, (D) Pomegranate peel extract nano gel 12.5%, (E) Pomegranate peel extract nano gel 25%

Mean number of lymphocytes, neutrophils,and macrophages

The normality test used in this research was the Shapiro Wilk, and the homogeneity test used the Levene Test. Based on the normality test results, p<0.05 means the data is distributed not normally and not homogeneous. Next, a Kruskal Wallis test was used to determine if there was a significant difference in the average number of lymphocyte, neutrophil, and macrophage cells in the control group andthe treatment group on days 3 and 7. The difference in the average number of cells on days 3 and 7 can be seen in table 5 and fig. 9.

Fig. 9: Comparison of lymphocyte, neutrophil, and macrophage counts on day 3 and day 7 after nanogel treatment, n = 3; values are expressed as mean±SD

Table 5: Mean number of cells in days 3 and 7 in the gingiva of male Wistar rats

| Group | Day | Average lymphocytes±SD | P Value | Average neutrophils±SD | P Value | Average macrophages±SD | P Value |

| F (-) | Day 3 | 11.00±1.00 | 0.031* | 6.00±0.00 | 0.025* | 9.67±2.08 | 0.009* |

| F (+) | Day 3 | 6.67±0.58 | 4.00±0.00 | 4.33±0.55 | |||

| F1 | Day 3 | 8.67±1.53 | 5.33±0.577 | 6.67±0.55 | |||

| F2 | Day 3 | 8.33±0.58 | 4.67±0.577 | 6.00±0.00 | |||

| F3 | Day 3 | 7.33±0.58 | 4.33±0.577 | 4.67±0.55 | |||

| F (-) | Day 7 | 9.67±0.58 | 0.015* | 4.33±0.57 | 0.043* | 7.67±0.577 | 0.034* |

| F (+) | Day 7 | 3.33±1.15 | 0.67±0.57 | 1.00±0.00 | |||

| F1 | Day 7 | 7.00±0.00 | 3.00±1.00 | 4.00±0.577 | |||

| F2 | Day 7 | 6.00±1.00 | 2.00±0.00 | 3.33±0.577 | |||

| F3 | Day 7 | 4.33±1.53 | 1.00±0.00 | 1.67±0.577 |

n = 3; values are expressed as mean±SD, Description: Kruskal-Wallistest, *Significant if (P<0.05), F (-): Negative control, F(+):Positivecontrol, F1: Pomegranate peel extract nano gel 6.25%, F2: Pomegranate peel extract nano gel 12.5%, F3:Pomegranatepeelextractnano gel 25%

Based on table 5 above, lymphocyte counts were notably higher in the negative control group across both time points, which indicated sustained inflammation due to the absence of active anti-inflammatory treatment. By contrast, the positive control group, treated with Gengigel, consistently showed the lowest lymphocyte counts, reflecting Gengigel's efficacy in reducing lymphocyte proliferation and mitigating inflammatory responses.

In the pomegranate peel nano gel treatment groups, lymphocyte counts decreased as the concentration of the extract increased. On day 3, the 25% nano gel group exhibited significantly lower lymphocyte counts than the 6.25% group (P<0.05), suggesting a dose-dependent effect of the extract in modulating lymphocyte-mediated inflammatory responses. By day 7, the trend was more pronounced, with the 25% nano gel group approaching lymphocyte counts similar to the positive control group, indicating the extract's potential to control inflammation over time at higher concentrations [20, 21].

Neutrophil counts followed a similar pattern, with the highest levels in the negative control group, indicating ongoing acute inflammation without treatment intervention. The positive control group showed the lowest neutrophil levels on both days, reflecting Gengigel's rapid anti-inflammatory effect [23, 24]. In the nano gel-treated groups, a decrease in neutrophil counts correlated with higher concentrations of pomegranate peel extract. By day 7, the 25% concentration group had significantly reduced neutrophil counts compared to the 6.25% group (P<0.05), suggesting that higher concentrations of pomegranate peel extract may accelerate the resolution of acute inflammatory responses by reducing neutrophil infiltration. These findings highlight the nanogel's capacity to suppress the activity of acute inflammatory cells, likely contributing to tissue healing and reduced tissue damage [23, 30].

Macrophage counts also revealed a clear pattern of inflammation modulation. In the untreated negative control, macrophage levels remained elevated across both days, consistent with chronic inflammatory progression. The positive control group displayed the lowest macrophage counts on both days, underscoring Gengigel's capacity to suppress macrophage activity and promote tissue regeneration. Among the treatment groups, the 25% nano gel concentration showed the most significant reduction in macrophage counts by day 7 compared to the lower concentrations (P<0.05). This reduction aligns with the natural progression of inflammation, where macrophages transition the response from inflammation to healing. Higher concentrations of pomegranate peel extract accelerate this transition, promoting a shift toward tissue repair [23, 24].

The comparative analysis between the pomegranate peel extractnanogel and Gengigel revealed that while the nano gel effectively reduced inflammatory cell counts, it did not achieve the same level of reduction as Gengigel, particularly by day 3. This observation may be attributed to Gengigel's hyaluronic acid component, which protects against bacterial plaque and supports tissue regeneration through its viscoelastic properties. The high adhesive nature of hyaluronic acid allows it to remain in contact with the gingival tissue longer, optimizing its anti-inflammatory and wound-healing effects [31].

Pomegranate peel extract contains various bioactive compounds, including flavonoids and tannins, which exhibit strong antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties. However, as a natural extract, its effects may be influenced by the interaction of multiple compounds, potentially leading to synergistic or antagonistic effects. The nano gel formulation in this study was designed to enhance bioavailability and controlled release, addressing the challenge of rapid degradation and poor penetration of bioactive compounds when applied in conventional formulations. The observed dose-dependent reduction in inflammatory cells suggests that higher extract concentrations (25%) optimize these effects, potentially compensating for the lower bioavailability of active compounds relative to the highly purified hyaluronic acid in Gengigel, which is known to promote wound healing and modulate inflammatory responses. Prior studies, such as those by Sayed et al. (2022), have demonstrated that pomegranate peel extract significantly reduces inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β and IL-6) and enhances antioxidant enzyme activities (SOD, GSH, and catalase) in hepatotoxicity models [31, 32].

This aligns with our findings, where pomegranate nano gel effectively suppressed lymphocyte, neutrophil, and macrophage infiltration, indicating potent anti-inflammatory effects in gingival inflammation. The mechanism of action is likely attributed to the high tannin and flavonoid content, particularly ellagic acid and punicalagin, which have been shown to inhibit NF-κB activation and downregulate pro-inflammatory mediators. Additionally, the nano gel delivery system prolongs retention time on gingival tissue, allowing sustained release and enhancing penetration of bioactive compounds. Compared to previous formulations of pomegranate peel extracts in oral applications, this study provides novel insights into the role of nanotechnology in optimizing the therapeutic potential of natural bioactive compounds. Further research is needed to explore pomegranate nano gel's pharmacokinetics and long-term effects of periodontal therapy [31, 32].

The progression from acute to chronic inflammation typically involves cellular responses. Neutrophils are the first responders, peaking within 24-48 h and contributing to initial tissue cleanup and immune signaling. In the present study, the reduction in neutrophils in the higher concentration nano gel groups suggests that pomegranate peel extract may facilitate an earlier transition to the macrophage-dominated phase of inflammation, a hallmark of the reparative phase.

Macrophages play a dual role in sustaining inflammation and promoting repair by releasing cytokines that stimulate tissue remodeling. By day 7, the 25% nano gel group demonstrated reduced macrophage presence, indicating that pomegranate peel extract may expedite the resolution of inflammation, thus advancing the healing process. The reduction in lymphocytes further supports this finding, as lymphocytes typically persist in areas of chronic inflammation and contribute to ongoing immune responses. Lower lymphocyte counts in the higher concentration groups suggest that the extract effectively dampens the sustained immune response, allowing tissue to transition into the healing phase [33, 34].

The results of this study indicate that pomegranate peel extract nanogel, particularly at higher concentrations, holds promise as an anti-inflammatory agent for gingival applications. The extract's ability to reduce lymphocyte, neutrophil, and macrophage infiltration supports its potential for managing periodontal inflammation. Although the nano gel's efficacy did not fully match Gengigel's, its natural composition offers an alternative for patients seeking plant-based treatments. Additionally, pomegranate peel extract's antimicrobial properties further enhance its applicability in treating gingivitis and periodontal disease, where bacterial colonization exacerbates inflammatory responses [33, 34].

Based on the study's results, pomegranate peel extract nano gel shows potential as an additional therapy in periodontal treatment, especially for gingivitis, with significant antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory effects. The efficacy of this nano gel shows that nanotechnology-based formulations can improve retention, bioavailability, and controlled release of bioactive compounds, thus providing more optimal therapeutic benefits than conventional preparations. However, this study has several limitations, including animal models that may not fully represent human clinical responses and the absence of direct comparisons with other natural formulations or available commercial products. Therefore, further research is needed to optimize the nano gel formulation, evaluate pharmacokinetics and bioavailability in the oral environment, and conduct clinical trials in humans to ensure its safety and effectiveness in treating periodontal disease.

CONCLUSION

This study concludes that pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) peel extract, particularly in a nano gel formulation, shows strong potential as an antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory agent for managing gingival inflammation. In vitro tests revealed that ethanol-based pomegranate peel extract effectively inhibited A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, and F. nucleatum, with optimal activity at a 25% concentration. In vivo, the nano gel reduced lymphocyte, neutrophil, and macrophage counts in a dose-dependent manner, with the highest concentration (25%) yielding significant anti-inflammatory effects. Although the nano gel did not surpass the effectiveness of the hyaluronic acid-based Gengigel, its natural bioactive compounds make it a promising alternative or complementary treatment for gingivitis. Future research should optimize the nano gel formulation for improved bioavailability and retention in gingival tissue, enhancing its therapeutic efficacy in oral health applications.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors significantly contributed to the conception, design, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation. They were involved in drafting and revising the article for important intellectual content. All authors agreed to submit the work to the current journal, approved the final version for publication, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the research.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Dioguardi M, Ballini A, Sovereto D, Spirito F, Cazzolla AP, Aiuto R. Application of the extracts of Punica granatum in oral cancer: scoping review. Dent J (Basel). 2022;10(12):234. doi: 10.3390/dj10120234, PMID 36547050.

Moga MA, Dimienescu OG, Balan A, Dima L, Toma SI, Bigiu NF. Pharmacological and therapeutic properties of Punica granatum phytochemicals: possible roles in breast cancer. Molecules. 2021;26(4):1054. doi: 10.3390/molecules26041054, PMID 33671442.

Lampakis D, Skenderidis P, Leontopoulos S. Technologies and extraction methods of polyphenolic compounds derived from pomegranate (punica granatum) peels a mini-review. Processes. 2021;9(2):236. doi: 10.3390/pr9020236.

Masfria M, Sumaiyah S, Syahputra H, Jenifer J. Anti-inflammatory and antiaging activity of hydrogel with active ingredient Phyllantusemblica L. fruit nanosimplicia. J Med Plants. 2023;22(28):49-64.

Diyatri I, Juliastuti WS, Ridwan RD, Ananda GC, Waskita FA, Juliana NV. Antibacterial effect of a gingival patch containing nanoemulsion of red dragon fruit peel extract on porphyromonas gingivalis aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans and fusobacterium nucleatum assessed in vitro. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2023;13(3):386-91. doi: 10.1016/j.jobcr.2023.03.011.

Bienvenue D, Bong D, Brian N, Staphane J, Hortense G, Charles M. In vitro evaluation of the efficacy of an aqueous extract of Allium sativum as an antibacterial agent on three major periodontal pathogen. J Oral Dent Health Res. 2021;3(1):2121.

Bamashmous S, Kotsakis GA, Kerns KA, Leroux BG, Zenobia C, Chen D. Human variation in gingival inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2021;118(27):e2012578118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2012578118, PMID 34193520.

Garcia Garcia ML, Tovilla Zarate CA, Villar Soto M, Juarez Rojop IE, Gonzalez Castro TB, Genis Mendoza AD. Fluoxetine modulates the pro-inflammatory process of IL-6, IL-1β and TNF-α levels in individuals with depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2022;307:114317. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114317, PMID 34864233.

Teixeira QE, Ferreira D DE C, DA Silva AM, Goncalves LS, Pires FR, Carrouel F. Aging as a risk factor on the immunoexpression of pro-inflammatory IL-1β, IL-6 and tnf-α cytokines in chronic apical periodontitis lesions. Biology. 2021;11(1):14. doi: 10.3390/biology11010014, PMID 35053012.

Fernandes T, D Souza AD, Sawarkar SP. Ocimum sanctum L: promising agent for oral health care management. Nat Oral Care Dent Ther. 2020:ch16. doi: 10.1002/9781119618973.

Rosaini H, Halim A, Sandi IE, Makmur I, Asra R, Sidoretno WM. Formulation and antioxidant activity of nano gel ethanol extract of kepok banana peel (musa X paradisiaca L.). Int Res J Pharm. 2021;12(1):21-5. doi: 10.7897/2230-8407.1201112.

Alotaibi G, Alharthi S, Basu B, Ash D, Dutta S, Singh S. Nano gels: recent advancement in fabrication methods for mitigation of skin cancer. Gels. 2023;9(4):331. doi: 10.3390/gels9040331, PMID 37102943.

Masfria S, Hafid Syahputra S. Antibacterial and anti-inflammatory activities of nanosimpliciaphyllantusemblica L. fruit in suspension formulation. Int J Appl Pharm. 2025;17(2). doi: 10.22159/ijap.2025v17i2.52608.

Masfria, Sumaiyah, Syahputra H, Fani V. Antiinflammation and antifungal effects of silver nanoparticles greenly synthesized using phyllanthus emblica L. extract as a reducing agent against dermatophytosis. International Journal of Applied Pharmaceutics. 2024;16(4):29. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2024.v16s4.06.

Evaluation of anti-inflammatory activity of solanum nigrum infused selenium nanoparticles an in vitro study. Int J Pharm Res. 2020;12:(sp1). doi: 10.31838/ijpr/2020.sp1.426.

Kumaran H, Gajendran PL, Arjunkumar R, Rajesh S. Anti inflammatory activity of lycopene and its based chitosan nanoformulation an in vitro study. Plant Cell Biotechnol Mol Biol. 2020;21:(51-2):91-100.

Masfria M, Sumaiyah S, Syahputra H, Witarman M. Formulation and evaluation of antibacterial and anti-inflammatory capsules containing phyllanthus emblica L. fruit nanoparticles. Sci Technol Indones. 2023;8(4):607-15. doi: 10.26554/sti.2023.8.4.607-615.

Yulistina Y. Potential nanogel extract of advocate fruit (Persea americana Mill.) as alternative in prevention of inflammation in white rats white rats post-extraction wounds. Journal Research of Social Science. Econ Manag. 2022;2(2). doi: 10.59141/jrssem.v2i02.293.

Amalia M, Nisa Brkemit GM, Kahfi M, Syahputra A, Ervina I, Nasution RO. In vitro evaluation of andaliman (Zanthoxylum acanthopodium DC) extract on the growth of periodontal pathogenic bacteria. Malaysian Journal of Microbiology. 2023;19(5). doi: 10.21161/MJM.220110.

Dimitriu T, Bolfa P, Daradics Z, Suciu S, Armencea G, Catoi C. Ligature-induced periodontitis causes atherosclerosis in rat descending aorta: an experimental study. Med Pharm Rep. 2021;94(1):106-11. doi: 10.15386/mpr-2044, PMID 33629057.

Pujiastuti P, Sakinah NN, DA AT AYM, Wahyukundari MA, Praharani D, Sari DS. The potential of toothpaste containing robusta coffee bean extract in reducing gingival inflammation and dental plaque formation. Dent J. 2023;56(2):109-14. doi: 10.20473/J.DJMKG.V56.I2.

Garcia VG, Miessi DM, Esgalha DA, Rocha T, Gomes NA, Nuernberg MAA, Cardoso J DE M, Ervolino E, Theodoro LH. The effects of Lactobacillus reuteri on the inflammation and periodontal tissue repair in rats: a pilot study. Saudi Dental Journal. 2022;34(6):516-26. doi: 10.1016/j.sdentj.2022.05.004.

Suryono S, Wulandari F, Andini H, Widjaja J, Nugraheni T. Methodology in wistar rats periodontitis induction: a modified ligation technique with injection of bacteria. Int J Oral Health Sci. 2020;10(1). doi: 10.4103/ijohs.ijohs_44_19.

Setiawatie EM, Gani MA, Rahayu RP, Ulfah N, Kurnia S, Augustina EF. Nigella sativa toothpaste promotes anti-inflammatory and anti-destructive effects in a rat model of periodontitis. Arch Oral Biol. 2022;137:105396. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2022.105396, PMID 35286946.

Sehari NH, Wafa S, Sehari NH, Siouda W, Sehari M, Merinas L. Phytochemical profile FTIR studies antioxidant and antifungal activity of extracts of pomegranate peel (Punica granatum L.). Ukr J Ecol. 2022;12(12):8-16.

Rahmat D, Budiati A. Formulation and activity of gel containing nanoparticles of javanese turmeric extract as antiacne (formulasi dan aktivitas gel yang mengandungnanopartikelekstraktemulawaksebagai antiacne). J Ilmu Kefarmasian Indones. 2020;18(1).

Azarashkan Z, Motamedzadegan A, Ghorbani Hasan Saraei A, Biparva P, Rahaiee S. Investigation of the physicochemical antioxidant rheological and sensory properties of ricotta cheese enriched with free and nano encapsulated broccoli sprout extract. Food Sci Nutr. 2022;10(11):4059-72. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.3001, PMID 36348770.

Amalia M, Yosuana PS, Mohammad IS Binti Nababan FSR Zulkarnain, Wulandari P, Nasution AH, Syahputra A. Inhibitory test of andaliman (Zanthoxylum achantopodium DC) extract mouthwash against dental plaque bacteria. Dental Journal. 2023;56(2):92-7. doi: 10.20473/J.DJMKG.V56.I2.P92-97.

Pattanashetti JI, Kalburgi NB, Patil KA, Sulakod K, Hannahson P. Antibacterial activity of abutilon indicum leaf extract against periodontal pathogens: an in vitro study. Int J Res Ayurveda Pharm. 2023;14(1):72-5. doi: 10.7897/2277-4343.140117.

Quintao Manhanini Souza E, Felipe Toro L, Franzao Ganzaroli V, DE Oliveira Alvarenga Freire J, Matsumoto MA, Casatti CA, Tavares Angelo Cintra L, Leone Buchaim R, Mardegan Issa JP, Gouveia Garcia V. Peri implantitis increases the risk of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaws associated with osseointegrated implants in rats treated with zoledronate. Scientific Reports. 2024;14(1). doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-49647-4.

Isnurhakim A, Suhartono B, Putranto R. Comparison for Carica papaya and gengigel leaves extraction for gingivitis healing effectiveness in orthodontic application. MEDALI. 2021;3(1). doi: 10.30659/medali.v3i1.17055.

Sayed S, Alotaibi SS, El Shehawi AM, Hassan MM, Shukry M, Alkafafy M. The anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic and antioxidant effects of a pomegranate peel extract against acrylamide induced hepatotoxicity in rats. Life (Basel). 2022;12(2):224. doi: 10.3390/life12020224, PMID 35207511.

Diyatri I, Kusumaningsih T, Tantiana HAR. Analysis of the expression of macrophage among periodontitis rat model after treatment with graptophyllum pictum (L.) Griff. leaves extract gel. Malays J Med Health Sci. 2020;16(4):92-6.

Saidah M, Oktiani BW, Taufiqurrahman I. The effect of flavonoid propolis kelulut (trigona spp) extract on macrophage cell number in periodontitis (in vivo study in male wistar rate (rattus novergicus) gingiva). Dentino :Jurnal Kedokteran Gigi. 2020;5(1):28. doi: 10.20527/dentino.v5i1.8117.