Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 3, 2025,1-12Review Article

THE ANTIOSTEOPOROTIC POTENTIAL OF HESPERIDIN AND ADVANCED DELIVERY SYSTEMS

VIJISHNA L. V.1, AKANKSHA D. DESSAI2, USHA Y. NAYAK2, RICHARD LOBO1*

1Department of Pharmacognosy, Manipal College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal-576104, Karnataka, India. 2Department of Pharmaceutics, Manipal College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal-576104, Karnataka, India

*Corresponding author: Richard Lobo; *Email: richard.lobo@manipal.edu

Received: 10 Dec 2024, Revised and Accepted: 14 Feb 2025

ABSTRACT

This study explores Hesperidin (HP) and its bone-protective effect against Osteoporosis (OP), summarizing its healing mechanisms supported by in vitro and in vivo evidence and insights into its ethnobotanical significance and advanced drug delivery systems. To gather information on the antiosteoporotic potential of HP, we thoroughly searched many scientific databases, including Science Direct, Google Scholar, PubMed, and Scopus, for articles published between 1990 and 2025. Data were collected using the keywords HP, traditional uses, phytochemistry, anti-OP, and drug delivery systems. Only studies published in English are considered for this review. It has gained attention for potential health benefits, especially the osteoprotective effect. In vitro studies found that HP reverses dexamethasone-induced inhibition of osteogenic differentiation by suppressing the p53 (Protein 53) pathway. In rat models of Postmenopausal (PM), senile, and disuse OP, HP showed bone-protective benefits. Clinical trials revealed a 15% increase in serum calcium and a 25% increase in osteocalcin levels, indicating enhanced bone formation. Comparative analysis showed that HP's efficacy in increasing bone mineral density is similar to that of bisphosphonates. The findings demonstrate that HP is an excellent therapeutic candidate that protects the skeleton through various mechanisms. Future research should focus on developing HP-based nutraceuticals or pharmaceuticals, integrating traditional knowledge with modern pharmacological approaches to enhance bone health. Despite its potential, the efficacy of HP formulations in treating OP has not yet been investigated.

Keywords: HP, OP, Advanced drug delivery systems

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i3.53661 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

OP is a significant public health problem characterized by low bone mass and Bone Mineral Density (BMD) (T-score: −2.5 and below), bone tissue deterioration, and disruption of bone microarchitecture, all of which raise the risk of fractures [1]. The bone loss progresses due to increased bone resorption and decreased bone production rates. It is a systemic bone and silent disease that exhibits no signs in its early stages [2]. Worldwide, one-fifth of men and more than half of women over 50 are at high risk of developing OP or fragility fractures [3, 4]. According to epidemiologic data from 2015, 46 million Indian women have OP [5]. Fractures caused by OP can lead to increased pain, disability, overall healthcare costs, and mortality [6]. The prognosis for OP is typically poor, and it is associated with several consequences, such as nerve irritation, blood vessel damage, systemic pain, and an elevated chance of fractures [7, 8]. The body continually takes in and replaces bone tissue, but in OP, eliminating old bone is more significant than developing a new bone [9, 10]. It has a high morbidity and mortality rate, and the risk of developing OP can increased by hormone deficiencies, age-related disorders, steroid therapy, nicotine addiction, rheumatoid arthritis, and metabolic disorders (diabetes, dyslipidemia, and metabolic syndrome). Pharmacologic treatments for OP include anabolic drugs like Teriparatide, Abaloparatide, and Parathyroid hormone analogs; Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERM) like Raloxifene; and Antiresorptive drugs like Denosumab and Bisphosphonates [6]. However, there are a few severe adverse effects linked to the use of these drugs. In one example, long-term Bisphosphonate use has been linked to a higher risk of atypical fracture and jaw osteonecrosis [11]. In addition, individuals may encounter typical side effects that primarily affect the cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and endocrine systems.

HP is a bioflavonoid primarily in citrus fruits, such as lemons and oranges [12]. It has drawn much interest due to its wide range of pharmacological characteristics, backed by substantial in vitro, in vivo, and clinical data. These characteristics include anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, antimicrobial, anticancer, neuroprotective, cardioprotective, skinprotective, osteoprotective effects and antioxidant [13]. HP can target various intracellular receptors, enzymes, signaling molecules, antioxidant enzymes, and transcription factors [14-16]. HP's bone-osteoprotective activities, covered in more detail below, are directly linked to some of its therapeutic benefits. Due to its potent anti-inflammatory and antioxidant qualities, HP can lessen the adverse effects of OP-induced abnormalities in osteoblastogenesis and osteoclastogenesis.

The main subject of this review paper is the in vitro and in vivo experimental proof of HP's effectiveness in reducing bone loss and promoting bone growth. HP's poor absorption and considerable first-pass metabolism face serious bioavailability issues. Limited research has been done on enhancing its bioavailability using advanced formulations, like nano-delivery systems. HP's molecular mode of action and its potential as a therapeutic osteoprotective drug are also covered in this review, along with its ethnobotanical significance and advanced drug delivery systems.

Methodology

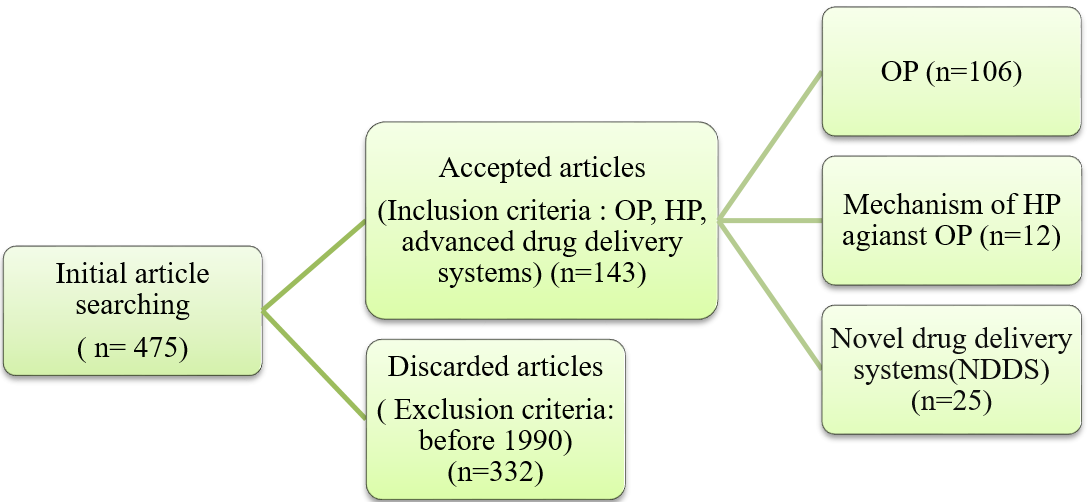

We made a thorough literature search to find relevant material from reliable databases such as scopus, PubMed, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library. Fig. 1 depicts the process of screening, selecting, and including the references gathered from the literature. The search phrases 'OP, HP, and advanced drug delivery systems' The search concentrated on articles published between 1990 and 2024 and selected only English ones.

RESULTS

Epidemiology, etiology, and risk factors of op

More than 200 million individuals worldwide have OP and around nine million OP fractures occur annually [17], adversely affecting people's quality of life and imposing a considerable economic burden [18, 19]. With an increasing aging population, fractures due to OP increase rapidly each year. It is a severe health problem, mainly in senior citizens. After menopause, during the first five years, women lose almost 10% of their bone mass [17].

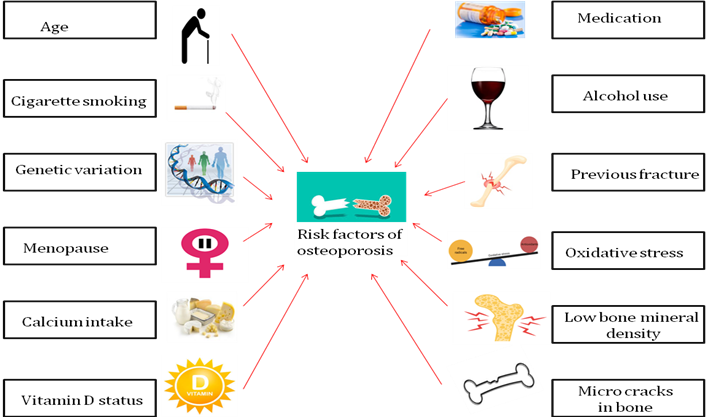

Two significant causes of OP are the lack of estrogen in PM women and aging-related dietary Ca and vit. D supplementation [20, 21]. Sex hormones can influence the proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis of Osteoblasts (OB) and Osteoclasts (OC) by affecting OP-related signaling pathways [22]. Age, sex steroid deficiency, reduced bone quality, microarchitectural integrity disruption, and use of glucocorticoids are the factors that increase OP fracture [19]. The risk factors of OP are discussed in fig. 2.

Fig. 1: Flowchart for article search, screening and selection in literature review

Source: BioRender.com

Fig. 2: Risk factors associated with OP

Source: BioRender.com

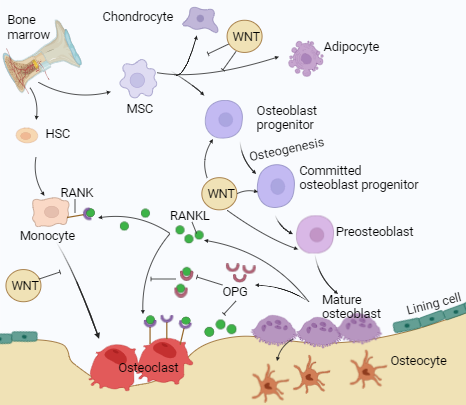

Fig. 3: The dynamic process of bone remodeling

Source: BioRender.com

Mechanism of bone remodeling

The human skeleton comprises bones, cartilage, ligaments, and tendons, making up 20% of the body's total weight [23]. The bones support and shield the body's essential organs [24]. It is a calcified tissue that contains 10% water, 30% organic components such as protein, and 60% inorganic components, often known as hydroxyapatite [23]. Two types of tissues appear in a bone: cortical and cancellous [25]. Cortical bone is shown to have tightly packed collagen fibrils and is protective [26, 27]. Cancellous bones, called trabecular bones, have a porous matrix that is loosely organized and responsible for metabolic functions. Bone homeostasis refers to the dynamic equilibrium of bone formation and resorption [28]. The maintenance of bone homeostasis involves three separate cell types. Osteocytes (OT) are mature bone cells, OB are bone-producing cells, and OC are bone resorption or breakdown cells. OB is formed from Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSC), while OC is derived from Hematopoietic Stem Cells (HSC) of bone marrow [29]. Bone turnover and remodeling occur throughout life and involve bone formation and resorption processes [30]. Bone tissue constantly remodels and has considerable regenerative capacity [31]. Maintaining bone health involves a well-balanced diet rich in Ca and Vit. D, exercise, avoiding smoking, and restricting alcohol use [32]. The mechanism of bone remodeling/homeostasis is shown in fig. 3.

Bone cells (OB, OC, OT), hormones, cytokines, ions, growth factors, transcriptional factors, and extracellular matrix proteins help maintain bone homeostasis [33]. The bone tissue environment controls bone matrix secretion and resorption. OB produces the proteins Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) and Osteocalcin (OCN), which are directly engaged in matrix mineralization [34]. Transcription factors, such as Runt-Related Transcription Factor-2 (RunX2) and Osterix (OSX), contribute to the OB development of undifferentiated cells like MSC [35]. Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMPs) and the Wingless Related Integration Site (Wnt/β-catenin) signaling pathways play a vital role in regulating transcription factors involved in OB differentiation. WNT signaling suppresses MSC and promotes OB development [36]. Wnt/β-catenin signaling indirectly inhibits OC development and bone resorption by increasing the release of Osteoprotegerin (OPG). OP is a widespread chronic disease characterized by low bone density, altered microstructure, and bone fragility, leading to low-impact fractures in affected individuals. The discovery of a few mutations that cause sporadic human diseases has identified the WNT signaling pathway as a candidate for therapeutic intervention aimed at increasing bone mass and strength. In particular, inhibition of sclerostin, a WNT antagonist secreted by OT, has proven in clinical trials to be a very efficient osteo-anabolic approach. One year of monthly administration of antibodies to sclerostin rapidly decreases bone resorption and increases bone formation and bone density at all sites, decreasing markedly fracture risk in treated patients. Their effect is, however, limited in time, and cardiovascular adverse events have been reported in one clinical trial targeting WNT signaling in the treatment of OP [15]. It also inhibits chondrogenesis and adipogenesis. OPG is RANKL's (Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor Kappa-B Ligand) natural decoy receptor [37]. RANKL helps to differentiate OC [38]. OPG binds with RANKL and blocks the signaling pathways that help in OC activation [15]. OC regulates bone formation and promotes tissue resorption using proteolytic enzymes and acids secreted into the bone matrix. Matrix Metalloproteinases (Mmp) and cysteine proteases are the primary enzymes involved in the breakdown of the organic matrix. The BMP signaling pathway promotes OC development and bone production [14].

Methods of diagnosis of OP

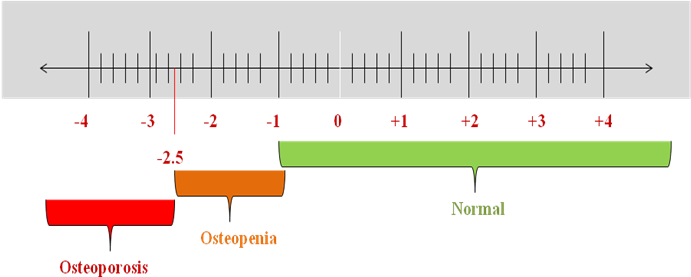

OP has no clinical manifestations until a fracture occurs. The gold standard test for BMD is DEXA (Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry). It is painless and non-invasive; X-rays scan specific to bones such as the spine, hip, and forearm. The findings were expressed as a T-score, which compared bone density to healthy young individuals. A T score of-2.5 or less on the DEXA test indicates OP [39]. All women over 65 should be examined for OP using DEXA to determine BMD. Most patients at elevated risk for fractures do not receive adequate evaluation or treatment for preventing future fractures. The current OP treatment mainly focuses on preventing bone resorption and promoting bone formation [40]. According to DEXA, the T-score interpretation is given in fig. 4.

T-score above-1: Normal

T-score in between-1 and-2.5: Osteopenia

T-score-2.5 or low: OP

Fig. 4: T-score interpretation for OP diagnosis

Source: BioRender.com

Current treatment available for OP

OP is treated with the help of chemical drugs like Alendronate, Risedronate, Zoledronate, Iodine, Monoclonal antibodies like Denosumab, and Hormone replacement therapy [41]. The ongoing treatment options are discussed in table 1.

Currently used medications for the treatment of OP produce serious health issues and are not able to offer long-term solutions [46]. There is a need to come up with better alternatives. Compared to existing OP treatments, phytocompounds such as flavonoids, alkaloids, and terpenoids have several benefits. Because of their anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and bone-protective qualities, these naturally occurring chemicals are increasingly acknowledged for their potential as therapeutics.

Natural products as the future of OP protection

Several natural compounds have been explored to treat OP to overcome the limitations of the current treatments, which show antiosteoporotic activity, promoting bone formation and suppressing bone resorption. A few examples of the phytomolecules that show OP activities are summarized in table 2.

Table 1: Current therapeutic approach for OP

| Medication | Mechanism | Route of administration | Side effects | References |

| Abaloparatide | Binding to the N-terminal moiety and the Para Thyroid Hormone (PTH) type 1 receptor | Subcutaneous | Joint discomfort, redness, or swelling at the place where the drug was injected | [42, 43] |

| Alendronate | Inducing OC apoptosis | Oral | Femoral fractures, OP of the jaw, risk for osteomalacia, skeletal lesions | [11, 44] |

| Bazedoxifene/Conjugated Estrogens | SERM | Oral route | Symptoms may include abdominal pain, nausea, muscle spasms, diarrhea, dyspepsia, oropharyngeal pain, neck pain, and dizziness. | [45] |

| Calcitonin-salmon | Binds to the calcitonin receptor found primarily in OC | Nasal spray | Muscle pain, body aches | [46] |

| Denosumab (human igG2 monoclonal antibody) | Against RANKL inhibits osteoclastogenesis | Subcutaneous | Skin eczema, cellulitis | [47] |

| Ibandronate | Inducing OC apoptosis | Oral, Intravenous | Femoral fractures, OP of the jaw, risk for osteomalacia, skeletal lesions | [11, 44] |

| Raloxifene (SERM) | It interacts with the RANK/RANKL/OPG system to prevent bone resorption | Oral route | Venous thromboembolism, stroke, breast, endometrial, ovarian cancers | [48–51] |

| Risedronate | Inducing OC apoptosis | Oral route | Femoral fractures, osteonecrosis of the jaw, risk for osteomalacia, skeletal lesions | [11, 44] |

| Romosozumab (monoclonal antibody) | It acts against the sclerostin pathway, enhancing bone formation and reducing bone resorption. | Subcutaneous | Skin eczema, cellulitis | [52] |

| Teriparatide | Binding to the N-terminal moiety and PTH type 1 receptor | Subcutaneous | Bone pain, cardiac arrhythmia, osteosarcoma | [39, 53] |

| Zoledronate | Inducing OC apoptosis | Intravenous | Femoral fractures, osteonecrosis of the jaw, risk for osteomalacia, skeletal lesions | [11, 44] |

Table 2: Phytomolecules exhibiting antiosteoporotic activity

| Phytoconstituents | Plant | Family | Mechanism against OP | References |

| Astilbin | Engelhardia roxburghiana | Juglandaceae | Astilbin inhibits bone loss in Ovariectomized (OVX) mice by inhibiting RANKL induced osteoclastogenesis | [54, 55] |

| Baicalein | Scutellaria baicalensis | Lamiaceae | Baicalein activates the mTORC1 (Target Of Rapamycin Complex 1) signaling pathway in MC3T3-E1cells (OB Precursor Cell Line), encouraging to develop into OB | [56, 57] |

| Bavachin | Psoralea corylifolia | Fabaceae | Bavachin exhibited OB proliferation-stimulating activities in the UMR106 cell line (Rat Osteosarcoma Cell Line) | [58] |

| Beriberin | Berberis aristata |

Berberidaceae | Through the Adenosine Monophosphate Activated Protein Kinase (AMPK) activation pathway, berberine protects diabetic rats from bone loss caused by pioglitazone | [59, 60] |

Calycosin |

Astragalus membranaceus | Leguminosae | Calycosin inhibits RANKL-mediated osteoclastogenesis via Mitogen Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) and NF-κB (Nuclear Factor-Kappa B) inhibition | [61, 62] |

| Catechin | Bergenia crassifoli | Saxifragaceae | Treatment with catechin reduced bone-resorbing cytokines Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (TNF-α) and Interleukin-6 (IL-6) production and apoptosis in OB | [63, 64] |

Ulmus davidiana |

Ulmaceae | Promotes apoptosis in OB | [63, 65] | |

| Corylin | Psoralea corylifolia | Fabaceae | In bone micromasses made of mesenchymal progenitor cells, calcineurin induced osteogenesis | [66] |

| Cyanidin | Lonicera caerulea | Caprifoliaceae | Cyanidin-3-glucoside controls OB differentiation through the Extra Cellular Signal Regulated Kinase (ERK1/2) signaling pathway | [67, 68] |

| Delphinidin | Solanum melongena | Solanaceae | Delphinidin reduces bone resorption by blocking RANKL-induced development of OC in an OP model | [69, 70] |

| Engeletin | Engelhardia roxburghiana | Juglandaceae | Inhibiting the osteoclastogenesis | [54] |

| Eriodictyol | Afzelia africana | Fabaceae | Eriodictyol inhibits RANKL-induced OC development | [71, 72] |

Equol |

Pueraria lobata | Fabaceae | Equol activates the Estrogen Receptor (ER) to stimulate the growth and differentiation of rat OB | [73, 74] |

| Formononetin | Actaea racemosa | Ranunculaceae | Formononetin inhibits the NF-κB, Proto-Oncogene (c-Fos) and cytoplasmic 1 signaling pathway activation generated by RANKL |

[75, 76] |

Genistein |

Glycine max | Fabaceae | Genistein stimulates the ER, MAPK-Runx2, and NO/Cyclic Guanosine Monophosphate (cGMP) pathways to promote OB differentiation and maturation. It also blocks the NF-κB signaling pathway and induces the osteoclastogenic inhibitor OPG to suppress OC production and bone resorption. | [77, 78] |

Glycitein |

Semen sojae praeparatum | Leguminosae | Glycitein suppresses OC generation and induces OC apoptosis | [79, 80] |

| HP | Citrus sinensis | Rutaceae | OP is alleviated by activating the estrogen signaling pathway via ESR1 | [81, 82] |

| Icariin | Epimedium brevicornu | Berberidaceae | Icariin enhanced Messenger Ribo-Nucleic Acid (mRNA) expression of Runx2 and osterix, while decreasing protein expression of Tumor Protein 38 (P38) and Jun N-Terminal Kinase (JNK) | [77, 83] |

| Icaritin | Herba epimedii | Berberidaceae | Reduced adipogenesis via the Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3 β (GSK-3β)/β-catenin signaling pathway | [77] |

Isorhamnetin |

Salsola imbricata | Amaranthaceae | Isorhamnetin controls reactive oxygen species to prevent osteoclastogenesis and protect chondrocytes | [84, 85] |

| Kaempferol | Cuscuta chinensis | Convolvulaceae | Kaempferol enhanced ALP activity in UMR-106 cells | [86] |

| Luteolin | Juncus acutus |

Juncaceae | Luteolin promotes human periodontal ligament cells osteogenic development | [87, 88] |

| Malvidin | Vaccinium angustifolium | Ericaceae | Promoting OB differentiation while suppressing OC production and differentiation | [89, 90] |

Myricetin |

Clitoria ternatea | Fabaceae | Myricetin inhibits osteoclastogenesis and promotes osteogenic differentiation | [91, 92] |

| Naringenin | Piper sarmentosum | Piperaceae | Naringenin functions as a superoxide scavenger, assisting the endogenous antioxidant defense mechanism in protecting bone against OP | [93] |

| Naringin | Citrus paradisi | Rutaceae | Naringin stimulates the expression of BMP-2 and promotes bone formation, bone MSC proliferation, and osteogenic differentiation | [94] |

| Nobiletin | Citrus sinensis |

Rutaceae | In mice with defective ovariectomy, nobiletin prevents bone resorption and preserves bone mass | [95, 96] |

| Peonidin | Vaccinium myrtillus | Ericaceae | Increases OB differentiation and decreases RANKL-induced bone resorption | [97, 98] |

| Petunidin | Vaccinium myrtillus | Ericaceae | Petunidin suppresses osteoclastogenesis and down regulates c-fos, Nuclear Factor of Activated T-cells Cytoplasmic (NFATc 1) and Mmp9 | [98, 99] |

| Quercetin | Helminthostachys zeylanica | Ophioglossaceae | The studies were carried out using Murine Macrophage Cell Line (RAW264.7). Quercetin inhibited RANKL-induced OC development in RAW264.7 cells showed IC50 value of 1.8±0.2 μm | [100] |

| Resvertrol | Polygonum cuspidatum |

Polygonaceae | OT proliferation and quantity in bone are both stimulated by resveratrol | [101, 102] |

| Rutin | Chrozophora tinctoria | Euphorbiaceae | Rutin 1 μm treatment for 48 h significantly increases the activity of all ossification indicators, including ALP enzyme, OCN hormone, and active Vit-D3 | [103, 104] |

| Tangeretin | Citrus reticulata |

Rutaceae | Tangeretin suppresses bone loss and preserves bone mass in estrogen-deficient OVX rats | [96, 105] |

| Taxifolin | Larix olgensis | Pinaceae | Taxifolin increases osteogenic development of human bone marrow MSC through the NF-κB pathway | [106] |

Among the many phytomolecules, HP shows significant benefits in terms of OP treatment. It is a polyphenolic bioflavonoid flavanone glycoside compound of citrus fruits such as grapefruit (Citrus paradise), lime (Citrus aurantifolia), tangerine (Citrus reticulata), lemon (Citrus limon) and orange (Citrus sinensis) belongs to the family Rutaceae. HP exists in the skin of fruits and vegetables and was previously famous as vitamin P because of its vitamin-like action. It is also found in small amounts of mint plant extracts, honey, and aromatic teas. It was initially separated from citrus peel by the French chemist "Lebreton" in 1828 [107, 108]. It possesses anti-aging, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, and antimicrobial properties [109–111]. Citrus peels contain more HP than the fruit itself, though this may vary from fruit to fruit. HP is abundant in citrus fruits' white, delicate inner layer and bright outer peel layers [112].

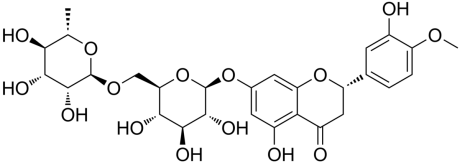

HP is a pale yellow hair-like needle, primarily found in the form of flavonoids, and is an odorless, tasteless compound obtained by alkaline hydrolysis or acid hydrolysis [113]. Chemically, HP is 3, 5, 7-trihydroxy flavanone or 7-rhamnoglucoside or hesperetin-7-O-rutino-side has a molecular weight of 610.57 with a molecular formula C28H34O15 and is composed of aglycone hesperetin and disaccharide rutinose [109]. Naturally, it resembles long, tan, or pale-yellow, hair-like needles. It melts at a temperature of 258-260 °C. At 25 °C, it has a saturation solubility of 4.93±0.99 μg/ml, indicating a slight solubility in water [114]. Its solubility varies with pH; at pH 9.11 (8.93±0.73 μg/ml) it is the most soluble, while at pH 1.21 (4.15±0.34 μg/ml) it is the least soluble. For pure HP, Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) thermal analysis reveals a distinctive endothermic peak at 259 °C, corresponding to its melting point [115]. Using Fourier-Transform Infra-Red (FTIR) spectroscopy, the hesperidin spectrum shows a prominent absorption band around 1644 cm−1, associated with its carbonyl stretching vibration. HP's stability varies depending on the chemical and environmental circumstances [116]. The structure of HP is shown in the fig. 5.

Fig. 5: Structure of HP

Source: ChemSketch

HP is poorly absorbed in the gastrointestinal system and has a low bioavailability. Substances such as bile salts can improve its absorption. HP is dispersed throughout the body after absorption. It has been discovered in a number of tissues, such as the brain, kidneys, and liver. In the liver, HP is extensively metabolized. The gut microbiota and enzymes like CYP3A and P-glycoprotein are mainly responsible for its metabolism to produce the more bioactive hesperetin and excreted through urine [117].

HP has been used in traditional medicine for decades, especially in areas with many citrus fruits. Its medicinal qualities have made it highly valued, particularly for promoting digestive and cardiovascular health. Improving circulation and treating ailments like varicose veins and weak blood flow are two of HP's main traditional uses. Current studies highlight its vasoprotective benefits, showing that teas or extracts from citrus peels frequently strengthen blood vessels and reduce inflammation [118]. Besides offering circulatory advantages, HP often promotes digestive well-being. People have long used citrus peel infusions to calm the stomach and ease the symptoms of ulcers, gastritis, and indigestion. Recent studies indicate that HP's anti-inflammatory properties may help reduce gastrointestinal distress, supporting this consistency [119]. Citrus fruits prevent or lessen colds and flu, and HP is also employed in traditional medicines to boost immune function. HP's antioxidants and antibacterial qualities probably helped produce these immune-stimulating effects [120].

HP possesses several biological and medicinal qualities, such as neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory, anti-allergic, antimicrobial, antiviral, and antioxidant activities [120]. HP can be utilized as a lead chemical or as a cheap anti-inflammatory drug, particularly for people who are allergic to the commonly used non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. With Diosmin, HP exhibits a notable protective effect against inflammatory illnesses in vitro and in vivo, potentially via a mechanism involving antioxidant free radical scavenger activity and/or suppression of eicosanoid production [121]. Cytokines like IL-1β (Interleukin-1β) and inflammatory mediators like TNF-α, Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate (NADPH) oxidase, Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase (iNOS), and Nitric Oxide (NO) were all reduced when HP administered. HP treatment reduces the adverse effects of long-term exposure to chlorpyrifos on hepato-renal damage by inhibiting inflammatory factors such as NF-κB, IL-1β, TNF-α, and iNOS. It is a promising natural substance for treating and preventing OP because it has shown strong osteoprotective properties [96]. Its advantages come from the capacity to control bone metabolism, reduce inflammation, and combat oxidative stress, which are all important aspects of bone health. Therefore, HP is studied more in terms of bone health and repair. This review aims to summarize the protective benefits of HP on bone as demonstrated by the currently available research. HP may also improve bone health through particular mechanisms, which will be covered in the current review.

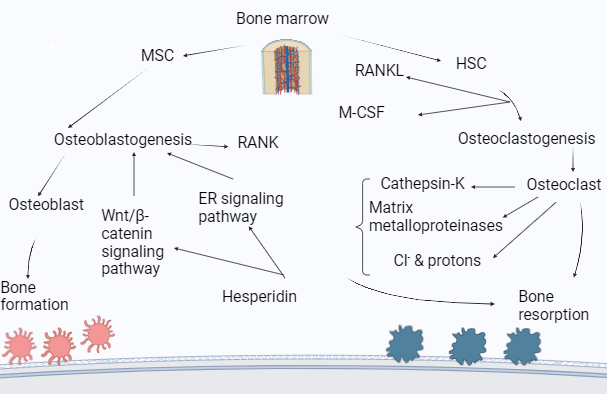

Molecular mechanisms of HP in OP prevention

A growing amount of data indicates that HP, through various mechanisms, increases bone density. It is essential in improving skeletal disorders and boosting bone health in general, including OP. These processes reduce oxidative stress and inflammatory responses, promoting OB development and OC differentiation. The mechanism of action of HP for the treatment of OP is given in fig. 6.

HP activates the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, enhances the estrogen signaling pathway, inhibits RANKL to reduce bone resorption, and suppresses Macrophage-Colony Stimulating Factor (M-CSF) to decrease OC differentiation.

Fig. 6: Therapeutic mechanism of HP in combating OP

Source: BioRender.com

MSC-Mesenchymal Stem Cells, HSC-Hematopoietic Stem Cells, ER-Estrogen Receptor, Wnt/β-Wingless related integration site, RANK-Receptor Activator of Nuclear factor Kappa, RANKL-Receptor Activator of Nuclear factor Kappa-B Ligand.

HSC and MSC are essential for bone remodeling and regeneration. HSCs generate blood cells involved in bone remodeling, and MSCs have the ability to develop into a variety of cell types, including OB [34]. HP stimulates the activity and development of OB, the cells that build bones. On the other hand, it prevents OC, which helps in bone resorption. Through a variety of mechanisms, HP exhibits strong antiosteoporotic potential. It alters the ER signaling pathway, which is crucial for preserving bone density, especially in women who have gone through menopause. HP has been found to increase ALP activity by 25% and boost OB proliferation by 30%. Furthermore, by blocking the cathepsin K enzyme, it lowers OC activity by 40% [81]. HP also stimulates OB development and bone production through the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and reduces the breakdown of bone tissue by blocking the action of the enzyme cathepsin K, which contributes to bone resorption [122]. Studies show that HP has a 50% rise in β-catenin levels and a 35% increase in Wnt target genes such as Axin2. This process is essential for the development and maintenance of bones [37]. In order to preserve bone integrity, HP controls MMPs, which are involved in bone matrix turnover. To promote osteoclastogenesis, the production of OC, which are cells in charge of bone resorption, RANKL attaches itself to RANK on OC precursors via the RANKL/RANK/OPG pathway [123]. HP modifies this mechanism to balance bone growth and resorption and affects M-CSF, which is involved in OC differentiation [81].

Antiosteoporotic potential of HP: evidence from preclinical and clinical studies

Evidence from preclinical studies

According to preclinical research, HP increases the ALP activity and OB proliferation, both of which are essential for bone formation. Additionally, it alters estrogen signaling pathways, which are vital for healthy bones. We have summarized the activity of HP through cellular and animal experiments, which are illustrated in table 3.

Table 3: Cellular level observations of HP for the prevention and treatment of OP

| Type of cell/Animal model | Treatment (HP concentration) |

Findings | Statistical difference | Reference |

| Bone marrow MSC induced by dexamethasone | 10 µM | Activation of p53 | Significantly increases ALP staining P<0.001 and Runx2 expression P<0.0001 |

[124] |

| Healthy human alveolar OB | 10 μmol/l | Activation of Wnt/β-Catenin pathway, expressions of β-Catenin and CyclinD1↑ | Significantly enhances ALP activity p<0.05 and Runx2 expression P<0.01 |

[122] |

| MC3T3-E1 induced by dexamethasone | 10 μg/ml | Cell proliferation, ALP, ESR1↑ oxidative stress ↓ |

Significantly increases ALP activity p<0.05, ALP staining p<0.05 and MC3T3-E1 cell proliferation p<0.05 |

[81] |

| MC3T3-E1 pre-osteoblastic cells | 500 µM | RunX2, OSX, bone sialoprotein, Collagen Type I Alpha 2 Chain (CO L1A2)↑ | At 1 µm significantly elevated osteogenic markers in pre-OB cells on day 7and 14 P<0.05 | [3] |

| Critically sized defect rat mandible model | 100 µM | Mature collagen fibers, matrix mineralization ↑ | BMP and HP together significantly increase bone repair P<0.05 | [3] |

| OVX ddY mice | 0.5 g/100 g | Number of OC, serum, hepatic lipids ↓ | Hepatic lipid and serum level significantly lower P<0.05 | [125] |

| OVX female Wistar rats | 5g/Kg | Improved BMD, femoral load improved |

Significantly reduce serum and hepatic lipid levels P<0.05 | [126] |

| OVX Sprague-Dawley rats | 20 mg/kg | OC, ALP, ACP, β-isomerized C-terminal telopeptides ↑ | Significantly enhances bone density, biomechanical properties P<0.001 | [127] |

| Prednisolone induced Zebrafish OP model | 1.25-10 μg/ml | Promotes osteogenesis, oxidative stress ↓, Estrogen signaling pathway activation through ESR1 | Fluorescence staining results showed lower oxidative stress P<0.01 |

[81] |

Clinical evidence

Studies have looked into how HP affects PM women, a crucial demographic for studying OP. Research has examined how HP affected PM's bone health both with and without a calcium supplement called Calcilock. Twelve healthy PMs participated in the double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized-order crossover study. To assess bone calcium retention, the researchers measured the rare isotope 41Ca's excretion in the urine. A statistically significant p-value of less than 0.04 indicated that the combination of calcium and HP increased bone calcium retention by 5.5%. However, there was no discernible improvement in bone calcium retention with HP alone. This study found that HP and calcium supplements (Calcilock) can effectively maintain bone health in PM, indicating the possible synergistic benefits of both substances. According to these results, HP by itself might not be enough to improve bone health, but when combined with calcium, it presents a viable method of lowering PM's risk of OP [128].

Drug delivery system for the treatment of OP

Nanoparticles are able to overcome the constraints of traditional therapies because of their unique physicochemical qualities, which include their small size, huge surface area-to-volume ratio, and customizable surface characteristics. Enhanced medication stability, controlled release kinetics, targeted bone tissue delivery, and better drug bioavailability are the benefits of nanoparticles. Specific physicochemical characteristics of nanoparticles, including silica, polymeric, solid lipid, and metallic nanoparticles, make them viable drug carriers for the treatment of OP [129]. Due to its porosity, silica nanoparticles can be used for imaging and medication delivery [130]. Targeted and prolonged medication release is made possible by the adaptability and customization of polymeric nanoparticles. Solid lipid nanoparticles can be used in a variety of medicinal applications because of their enhanced drug stability, controlled release, and biocompatibility. For imaging, medication delivery, and therapeutic uses, metallic nanoparticles like gold nanoparticles have unique optical qualities. The effectiveness of OP treatment is improved by their enhancement of medication bioavailability, stability, and targeted delivery [131]. HP has a few limitations that can be addressed through such drug delivery systems.

The main drawbacks of HP are its low water solubility and bioavailability. Because the gut microbiota must change into its more accessible form, hesperetin, its absorption in the gastrointestinal system is limited. HP's hydrophobic properties further limit its ability to dissolve in water, reducing its therapeutic effectiveness and absorption efficiency [117].

Several strategies can be used to address HP solubility and bioavailability problems. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLNs) and liposomes are examples of nanotechnology that improves solubility and absorption. While Self-Emulsifying Drug Delivery Systems (SEDDS) increase bioavailability by creating emulsions in aqueous settings, co-formulation with cyclodextrin improves dissolution rates. Enhancers of bioavailability, such as piperine (found in black pepper), improve absorption by blocking metabolic enzymes. HP is protected and released under regulated conditions by microencapsulation. Its hydrophilicity can also be increased by chemical changes like glycosylation, increasing its solubility and bioavailability and boosting its therapeutic efficacy in diseases like OP [132]. Researchers have tried to make HP-encapsulated nanoparticles to improve their properties, and an overview of such drug delivery systems is illustrated in table 4, demonstrating the enhanced functions.

Table 4: Hesperidin drug delivery systems across various diseases

| Drug delivery system | Disease | Property | Study type | Key findings | Reference |

| Self nano-emulsifying drug delivery system | Wound-healing | Enhanced solubility and absorption | Wistar rats | Effective Co-delivery | [133] |

| HP loaded Polylactic-Co-Glycolic Acid (PLGA) nanoparticles | Colorectal cancer | Enhanced bioavailability, reducing survival rate of cancer cells | HCT116 colorectal cancer cell line | Ensuring consistent drug delivery | [134] |

| Nanotheranostic carrier system | Cancer | Controlled drug release | Balb/c mice and HeLa cell line | Targeted drug delivery | [135] |

| Chitosan/HP nanoparticles | Cancer | Enhance the bioavailability and solubility of hesperidin | MDA-MB-231 cell line | Targeted drug delivery | [136] |

| Extracellular vesicle nanodrugs | Malignant glioma | Enhance the efficacy | Balb/c mice | Enhanced drug delivery | [137] |

| Magnetic gelatin-HP microrobots | Diabetic foot ulcers | Enhance the bioavailability and solubility of HP | Human dermal fibroblasts | Enhanced drug delivery | [138] |

| HP-loaded Polyvinyl alcohol/alginate hydrogel | Skin injuries and wound healing | Enhance the bioavailability and solubility of HP | Human dermal fibroblasts | Controlled drug release | [139] |

| HP-conjugated gold nanoparticles | Diabetes-induced cognitive impairment | Enhance the bioavailability and solubility of HP | Sprague-Dawley rats | Targeted delivery | [131] |

| HP-loaded lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles | Wound healing | Controlled drug release | Human dermal fibroblasts | Enhanced drug delivery | [140] |

| Nanostructured lipid carrier | Helicobacter pylori infection | Enhances the delivery and efficacy of HP against Helicobacter pylori | Gastric epithelial cells | Targeted action | [141] |

Toxicity profile of HP

In a 2019 study, Li et al. extracted HP from orange peel and conducted both acute and sub-chronic oral toxicity tests using Dawley rats. For the acute toxicity study, ten rats were administered HP orally at various doses (55, 175, 550, 1750, and 5000 mg/kg). The animals were monitored for 14 d for any signs of illness or mortality. The results showed no indications of acute toxicity.

For the sub-chronic toxicity trial, 15 rats were given oral doses of HP at 0, 250, 500, and 1000 mg/kg for 13 w. The study found no signs of sub-chronic toxicity, indicating that HP is safe at these dosage levels [142].

In another study by Hu et al., zebrafish larvae were used for toxicity tests. The larvae were treated with varying concentrations of HP (0, 1.25, 2.5, 5, and 10μg/ml). The results demonstrated that HP was not toxic to zebrafish larvae [143].

Comparative research has demonstrated that HP's anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties are similar to those of other flavonoids, such as rutin, quercetin, and naringin. A metabolite of HP, hesperetin, exhibits more decisive antibacterial and radical scavenging action. Rutin, quercetin, naringin, and hesperetin have low toxicity. Studies show they are generally safe at typical dietary or supplemental levels, but high doses may cause adverse effects like nausea and diarrhea.

In contrast to Bisphosphonates and SERMs, HP exhibits the potential for increasing bone formation and decreasing resorption without increasing the risk of atypical femoral fractures and Osteonecrosis of the jaw. HP's safety has been validated by toxicity tests conducted on Dawley rats and zebrafish larvae.

DISCUSSION

HP, a bioflavonoid in citrus fruits, offers advantages over standard OP treatments. In contrast to traditional treatments, it targets the p53 signaling pathway, which is essential for osteogenic differentiation. The usefulness of HP is suggested by the fact that it can reverse the suppression of osteogenic differentiation caused by dexamethasone by decreasing p53 activation. Additionally, it increases the microarchitecture and mineral density of bones, strengthening the skeleton and lowering the risk of fracture. Because of this all-encompassing strategy, HP is a viable substitute for conventional therapies, offering specific advantages for the treatment of OP.

Various study designs, dosages, populations, formulations, and techniques can result in variations in the effectiveness of hesperidin. Reviewing these is essential to get a thorough understanding. As an osteoporosis treatment and prevention medication, hesperidin exhibits great promise and presents a viable substitute with fewer adverse effects.

CONCLUSION

Several studies have reported the protective effect of HP against OP. By controlling bone production and metabolism, HP inhibits activated p53, which may help to treat or prevent OP. It regulates cell differentiation through the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and affects the mineralization process by upregulating the expression of the osteogenic genes (ALP, OCN, Osx, and Runx2) in human alveolar OB. By encouraging osteoblast genesis and bone production, HP has antiosteoporotic, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory properties.

By maintaining intestinal absorption of calcium, HP also boosts endogenous antioxidants, especially those found in the intestines. HP has anti-inflammatory qualities because it inhibits proinflammatory cytokines like Tumor necrosis factor-α, Interleukin-1β, and Interleukin-6, as well as NF-κB.

In vitro studies established its anti-OC activity by inhibiting osteoclastic markers like RANKL, cathepsin K, TRAP, and proinflammatory cytokines such as Interleukin-1β, Interleukin-6, Interleukin-8, TNF-α, and Matrix metalloproteinases-3, 9, 13, as well as by reducing Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS). It has advantages for mineralized tissue due to its anti-collagenolytic activity.

Based on research done on animal models, HP lowers bone loss and enhances the regeneration of bone tissue. In vivo, evidence indicates that HP's antiosteoporotic activity reduces trabecular bone loss and increases bone mineral density.

Emerging nanotechnology-based Drug Delivery Systems (DDS) offer promising advancements in the targeted treatment of OP. These systems can deliver HP more precisely and effectively to specific body locations, reducing adverse effects and improving patient outcomes.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Future directions include conducting clinical trials to further validate the efficacy and safety of HP in treating OP and exploring formulation innovations to enhance HP's bioavailability and therapeutic effect. Still, more research is needed to minimize the limitations of HP. Continued research and innovation in this area hold great promise for developing more effective OP therapies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Authors Vijishna. L. V and Akanksha D Dessai are thankful to the Manipal Academy of Higher Education (MAHE) for providing Dr. T. M. A. Pai Doctoral Fellowship. The authors also acknowledge with thanks to Manipal College of Pharmaceutical Sciences for providing facilities for this work. The authors also thank BioRender.com and ChemSketch.

FUNDING

This research received no external funding.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

VIJISHNA L V: Conceptualization, data curation, writing original draft, writing-review and editing.

Akanksha D Dessai: Writing original draft, writing-review and editing.

Usha Y Nayak: Investigation, Supervision.

Richard Lobo: Investigation, Supervision.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

REFERENCES

Ahmad Hairi H, Jayusman PA, Shuid AN. Revisiting resveratrol as an osteoprotective agent: molecular evidence from in vivo and in vitro studies. Biomedicines. 2023 May 16;11(5):1453. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines11051453, PMID 37239124.

Shah A, Gourishetti K, Nayak Y. Osteogenic activity of resveratrol in human fetal osteoblast cells. Phcog Mag. 2019;15(64):250-5. doi: 10.4103/pm.pm_619_18.

Miguez PA, Tuin SA, Robinson AG, Belcher J, Jongwattanapisan P, Perley K. Hesperidin promotes osteogenesis and modulates collagen matrix organization and mineralization in vitro and in vivo. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Mar 22;22(6):3223. doi: 10.3390/ijms22063223, PMID 33810030.

Yang J, Cong N, Shi D, Chen S, Zhang Z, Zhao P. Siwu decoction exerts a phytoestrogenic osteoprotective effect on postmenopausal osteoporosis via the estrogen receptor/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/serine/threonine protein kinase pathway. J Ethnopharmacol. 2024 May 18;332:118366. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2024.118366, PMID 38763371.

Khadilkar AV, Mandlik RM. Epidemiology and treatment of osteoporosis in women: an Indian perspective. Int J Womens Health. 2015;7:841-50. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S54623, PMID 26527900.

TU KN, Lie JD, Wan CK, Cameron M, Austel AG, Nguyen JK. Osteoporosis: a review of treatment options. Pharm Ther. 2018 Feb;43(2):92-104.

Wang C, Zeng R, LI Y, HE R. Cirsilineol inhibits RANKL-induced osteoclast activity and ovariectomy-induced bone loss via NF-κb/ERK/p38 signaling pathways. Chin Med. 2024 May 14;19(1):69. doi: 10.1186/s13020-024-00938-6, PMID 38745234.

Sahu TK, Shanmugam J, Sundaram G, Cannane S. Detection of bone marrow edema in vertebral compression fractures using third generation dual-energy computed tomography and virtual non-calcium techniques. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2024;17(9):19-21.

Florencio Silva R, Sasso GR, Sasso Cerri E, Simoes MJ, Cerri PS. Biology of bone tissue: structure function and factors that influence bone cells. Bio Med Res Int. 2015;2015:421746. doi: 10.1155/2015/421746, PMID 26247020.

Xiao D, Huang S, Tang Z, Liu M, DI D, MA Y. Mijiao formula regulates NAT10-mediated Runx2 mRNA ac4C modification to promote bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell osteogenic differentiation and improve osteoporosis in ovariectomized rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2024 Aug 10;330:118191. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2024.118191, PMID 38621468.

Huang CY, Cheng CJ, Chiou WF, Chang WC, Kang YN, Lee MH. Efficacy and safety of duhuo jisheng decoction add on bisphosphonate medications in patients with osteoporosis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Ethno pharmacol. 2022 Jan 30;283:114732. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2021.114732, PMID 34637967.

Ahmed H, Aboul Enein A, Abou Elella F, Salem S, Aly H, Nassrallah A. Nano-formulations of hesperidin and essential oil extracted from sweet orange peel: chemical properties and biological activities. Egypt J Chem. 2021 Aug 4;64(9):5373-85. doi: 10.21608/ejchem.2021.84783.4139.

Agrawal PK, Agrawal C, Blunden G. Pharmacological significance of hesperidin and hesperetin two citrus flavonoids as promising antiviral compounds for prophylaxis against and combating COVID-19. Nat Prod Commun. 2021 Oct 1;16(10). doi: 10.1177/1934578X211042540.

Beederman M, Lamplot JD, Nan G, Wang J, Liu X, Yin L. BMP signaling in mesenchymal stem cell differentiation and bone formation. J Biomed Sci Eng. 2013 Aug;6(8A):32-52. doi: 10.4236/jbise.2013.68A1004, PMID 26819651.

Baron R, Gori F. Targeting WNT signaling in the treatment of osteoporosis. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2018 Jun 1;40:134-41. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2018.04.011, PMID 29753194.

Almukainzi M, El Masry TA, El Zahaby EI, El Nagar MM. Chitosan/hesperidin nanoparticles for sufficient compatible antioxidant and antitumor drug delivery systems. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2024 Jul 29;17(8):999. doi: 10.3390/ph17080999, PMID 39204104.

Lee H, Kim MH, Choi Y, Yang WM. Ameliorative effects of Osteo-F, a newly developed herbal formula on osteoporosis via activation of bone formation. J Ethnopharmacol. 2021 Mar 25;268:113590. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2020.113590, PMID 33212177.

Viju KK, Shah MR. Awareness of delayed healing in post-operative fracture conditions in osteoporotic patients. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2024;17(6):146-8. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2024.v17i6.50642.

Sozen T, Ozısık L, Basaran NC. An overview and management of osteoporosis. Eur J Rheumatol. 2017 Mar;4(1):46-56. doi: 10.5152/eurjrheum.2016.048, PMID 28293453.

Cheng CH, Chen LR, Chen KH. Osteoporosis due to hormone imbalance: an overview of the effects of estrogen deficiency and glucocorticoid overuse on bone turnover. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Jan 25;23(3):1376. doi: 10.3390/ijms23031376, PMID 35163300.

Tella SH, Gallagher JC. Prevention and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2014 Jul;142:155-70. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2013.09.008, PMID 24176761.

LU Y, Zhang M, Zhang J, Jiang M, Bai G. Psoralen prevents the inactivation of estradiol and treats osteoporosis via covalently targeting HSD17B2. J Ethnopharmacol. 2023 Jul 15;311:116426. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2023.116426, PMID 36997132.

Dunstan C, Blair J, Zhou HM, Seibel MJ. Bone mineral connective tissue metabolism. Compr Med Chem. 2006 Nov 1;6:495-520.

Hart NH, Newton RU, Tan J, Rantalainen T, Chivers P, Siafarikas A. Biological basis of bone strength: anatomy physiology and measurement. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2020;20(3):347-71. PMID 32877972.

Blair HC, Larrouture QC, LI Y, Lin H, Beer Stoltz D, Liu L. Osteoblast differentiation and bone matrix formation in vivo and in vitro. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2017 Jun 1;23(3):268-80. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEB.2016.0454, PMID 27846781.

Clarke B. Normal bone anatomy and physiology. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008 Nov;3 Suppl 3:S131-9. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04151206, PMID 18988698.

Nair AK, Gautieri A, Chang SW, Buehler MJ. Molecular mechanics of mineralized collagen fibrils in bone. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1724. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2720, PMID 23591891.

Kim JM, Lin C, Stavre Z, Greenblatt MB, Shim JH. Osteoblast osteoclast communication and bone homeostasis. Cells. 2020 Sep 10;9(9):2073. doi: 10.3390/cells9092073, PMID 32927921.

Foster BM, Shi L, Harris KS, Patel C, Surratt VE, Langsten KL. Bone marrow derived stem cell factor regulates prostate cancer induced shifts in pre-metastatic niche composition. Front Oncol. 2022;12:855188. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.855188, PMID 35515124.

Siddiqui JA, Partridge NC. Physiological bone remodeling: systemic regulation and growth factor involvement. Physiology (Bethesda). 2016 May;31(3):233-45. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00061.2014, PMID 27053737.

Kanczler J, Wells J, Gibbs D, Marshall K, Tang DK, Oreffo R. Bone tissue engineering and bone regeneration; 2020. p. 917-35.

Anam AK, Insogna K. Update on osteoporosis screening and management. Med Clin North Am. 2021 Nov;105(6):1117-34. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2021.05.016, PMID 34688418.

Weitzmann MN. Bone and the immune system. Toxicol Pathol. 2017 Oct;45(7):911-24. doi: 10.1177/0192623317735316, PMID 29046115.

Murshed M. Mechanism of bone mineralization. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2018 Dec;8(12):a031229. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a031229, PMID 29610149.

Komori T. Regulation of osteoblast differentiation by transcription factors. J Cell Biochem. 2006 Dec 1;99(5):1233-9. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20958, PMID 16795049.

Kim JH, Liu X, Wang J, Chen X, Zhang H, Kim SH. Wnt signaling in bone formation and its therapeutic potential for bone diseases. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2013 Feb;5(1):13-31. doi: 10.1177/1759720X12466608, PMID 23514963.

Mazemondet O, Hubner R, Frahm J, Koczan D, Bader BM, Weiss DG. Quantitative and kinetic profile of Wnt/β-catenin signaling components during human neural progenitor cell differentiation. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2011 Dec;16(4):515-38. doi: 10.2478/s11658-011-0021-0, PMID 21805133.

Park JH, Lee NK, Lee SY. Current understanding of RANK signaling in osteoclast differentiation and maturation. Mol Cells. 2017 Oct 31;40(10):706-13. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2017.0225, PMID 29047262.

Collison J. Osteoporosis: teriparatide preferable for fracture prevention. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2018 Jan;14(1):4. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2017.194, PMID 29167546.

Cooper C, Campion G, Melton LJ. Hip fractures in the elderly: a world-wide projection. Osteoporos Int. 1992 Nov 1;2(6):285-9. doi: 10.1007/BF01623184, PMID 1421796.

Chaugule SR, Indap MM, Chiplunkar SV. Marine natural products: new avenue in treatment of osteoporosis. Front Mar Sci. 2017 Nov 29;4. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2017.00384.

Leder BZ, Mitlak B, HU MY, Hattersley G, Bockman RS. Effect of abaloparatide vs alendronate on fracture risk reduction in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105(3):938-43. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgz162, PMID 31674644.

Merlotti D, Falchetti A, Chiodini I, Gennari L. Efficacy and safety of abaloparatide for the treatment of post-menopausal osteoporosis. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2019 May;20(7):805-11. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2019.1583208, PMID 30856013.

Sindel D. Osteoporosis: spotlight on current approaches to pharmacological treatment. Turk J Phys Med Rehabil. 2023 May 15;69(2):140-52. doi: 10.5606/tftrd.2023.13054, PMID 37671373.

Lindsay R, Gallagher JC, Kagan R, Pickar JH, Constantine G. Efficacy of tissue selective estrogen complex of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for osteoporosis prevention in at risk postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2009 Sep 1;92(3):1045-52. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.02.093, PMID 19635616.

Zhou Z, Wang N, Ding C, Zhou X, Zhou J. Postmenopausal osteoporosis treated with acupoint injection of salmon calcitonin:a randomized controlled trial. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. 2016 Jul 12;36(7):705-8. doi: 10.13703/j.0255-2930.2016.07.008, PMID 29231409.

Kobayakawa T, Miyazaki A, Saito M, Suzuki T, Takahashi J, Nakamura Y. Denosumab versus romosozumab for postmenopausal osteoporosis treatment. Sci Rep. 2021 Jun 3;11(1):11801. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-91248-6, PMID 34083636.

Jolly EE, Bjarnason NH, Neven P, Plouffe L, Johnston CC, Watts SD. Prevention of osteoporosis and uterine effects in postmenopausal women taking raloxifene for 5 years. Menopause. 2003 Jul;10(4):337-44. doi: 10.1097/01.GME.0000058772.59606.2A, PMID 12851517.

Vestergaard P, Hermann AP, Gram J, Jensen LB, Kolthoff N, Abrahamsen B. Improving compliance with hormonal replacement therapy in primary osteoporosis prevention. Maturitas. 1997 Dec 15;28(2):137-45. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(97)00076-5, PMID 9522321.

Vincent A, Riggs BL, Atkinson EJ, Oberg AL, Khosla S. Effect of estrogen replacement therapy on parathyroid hormone secretion in elderly postmenopausal women. Menopause N Y N. 2003 Mar;10(2):165-71.

Wein MN, Kronenberg HM. Regulation of bone remodeling by parathyroid hormone. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2018 Aug 1;8(8):a031237. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a031237, PMID 29358318.

Singh S, Dutta S, Khasbage S, Kumar T, Sachin J, Sharma J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacy and safety of romosozumab in postmenopausal osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2022 Jan;33(1):1-12. doi: 10.1007/s00198-021-06095-y, PMID 34432115.

Kendler DL, Marin F, Zerbini CA, Russo LA, Greenspan SL, Zikan V. Effects of teriparatide and risedronate on new fractures in post-menopausal women with severe osteoporosis (VERO): a multicentre double blind double dummy randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018 Jan 20;391(10117):230-40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32137-2, PMID 29129436.

Huang H, Cheng Z, Shi H, Xin W, Wang TT, YU LL. Isolation and characterization of two flavonoids engeletin and astilbin from the leaves of Engelhardia roxburghiana and their potential anti-inflammatory properties. J Agric Food Chem. 2011 May 11;59(9):4562-9. doi: 10.1021/jf2002969, PMID 21476602.

Jin H, Wang Q, Chen K, XU K, Pan H, Chu F. Astilbin prevents bone loss in ovariectomized mice through the inhibition of rankl induced osteoclastogenesis. J Cell Mol Med. 2019 Dec;23(12):8355-68. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14713, PMID 31603626.

LI SF, Tang JJ, Chen J, Zhang P, Wang T, Chen TY. Regulation of bone formation by baicalein via the mTORC1 pathway. Drug Des Dev Ther. 2015;9:5169-83. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S81578, PMID 26392752.

Liao H, YE J, Gao L, Liu Y. The main bioactive compounds of Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi. for alleviation of inflammatory cytokines: a comprehensive review. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021 Jan;133:110917. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110917, PMID 33217688.

Wang D, LI F, Jiang Z. Osteoblastic proliferation stimulating activity of Psoralea corylifolia extracts and two of its flavonoids. Planta Med. 2001 Nov;67(8):748-9. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-18343, PMID 11731919.

Adil M, Mansoori MN, Singh D, Kandhare AD, Sharma M. Pioglitazone induced bone loss in diabetic rats and its amelioration by berberine: a portrait of molecular crosstalk. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017 Oct;94:1010-9. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.08.001, PMID 28810524.

Yogesh HS, Chandrashekhar VM, Katti HR, Ganapaty S, Raghavendra HL, Gowda GK. Anti-osteoporotic activity of aqueous methanol extract of Berberis aristata in ovariectomized rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011 Mar 24;134(2):334-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.12.013, PMID 21182919.

Park KR, Park JE, Kim B, Kwon IK, Hong JT, Yun HM. Calycosin-7-O-β-Glucoside isolated from astragalus membranaceus promotes osteogenesis and mineralization in human mesenchymal stem cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Oct 21;22(21):11362. doi: 10.3390/ijms222111362, PMID 34768792.

Quan GH, Wang H, Cao J, Zhang Y, WU D, Peng Q. Calycosin suppresses rankl-mediated osteoclastogenesis through inhibition of MAPKs and NF-κB. Int J Mol Sci. 2015 Dec 10;16(12):29496-507. doi: 10.3390/ijms161226179, PMID 26690415.

Choi EM, Hwang JK. Effects of (+)-catechin on the function of osteoblastic cells. Biol Pharm Bull. 2003 Apr;26(4):523-6. doi: 10.1248/bpb.26.523, PMID 12673036.

Ivanov SA, Nomura K, Malfanov IL, Sklyar IV, Ptitsyn LR. Isolation of a novel catechin from bergenia rhizomes that has pronounced lipase inhibiting and antioxidative properties. Fitoterapia. 2011 Mar;82(2):212-8. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2010.09.013, PMID 20923698.

Hosny M, Zheng MS, Zhang H, Chang HW, Woo MH, Son JK. (–)-Catechin glycosides from Ulmus davidiana. Arch Pharm Res. 2014 Jun;37(6):698-705. doi: 10.1007/s12272-013-0264-6, PMID 24155021.

YU AX, XU ML, Yao P, Kwan KK, Liu YX, Duan R. Corylin a flavonoid derived from psoralea fructus induces osteoblastic differentiation via estrogen and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways. FASEB J. 2020 Mar;34(3):4311-28. doi: 10.1096/fj.201902319RRR, PMID 31965654.

Chen L, Xin X, Lan R, Yuan Q, Wang X, LI Y. Isolation of cyanidin 3-glucoside from blue honeysuckle fruits by high speed counter current chromatography. Food Chem. 2014;152:386-90. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.11.080, PMID 24444952.

HU B, Chen L, Chen Y, Zhang Z, Wang X, Zhou B. Cyanidin-3-glucoside regulates osteoblast differentiation via the ERK1/2 signaling pathway. ACS Omega. 2021 Feb 23;6(7):4759-66. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.0c05603, PMID 33644583.

Fan C, LI N, Cao X, Wen L. Ionic liquid modified countercurrent chromatographic isolation of high purity delphinidin-3-rutinoside from eggplant peel. J Food Sci. 2020 Apr;85(4):1132-9. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.15089, PMID 32144797.

Imangali N, Phan QT, Mahady G, Winkler C. The dietary anthocyanin delphinidin prevents bone resorption by inhibiting rankl induced differentiation of osteoclasts in a medaka (Oryzias latipes) model of osteoporosis. J Fish Biol. 2021 Apr;98(4):1018-30. doi: 10.1111/jfb.14317, PMID 32155282.References

Lee J, Noh AL, Zheng T, Kang JH, Yim M. Eriodicyol inhibits osteoclast differentiation and ovariectomy induced bone loss in vivo. Exp Cell Res. 2015 Dec 10;339(2):380-8. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2015.10.001, PMID 26450448.

Vigbedor BY, Osei Akoto C, Neglo D. Isolation and identification of flavanone derivative eriodictyol from the methanol extract of Afzelia africana bark and its antimicrobial and antioxidant activities. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2023;2023:9345047. doi: 10.1155/2023/9345047, PMID 37200890.

Kwon JE, Lim J, Kim I, Kim D, Kang SC. Isolation and identification of new bacterial stains producing equol from Pueraria lobata extract fermentation. Plos One. 2018;13(2):e0192490. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192490, PMID 29447179.

Wang J, XU J, Wang B, Shu FR, Chen K, MI MT. Equol promotes rat osteoblast proliferation and differentiation through activating estrogen receptor. Genet Mol Res. 2014 Jul 4;13(3):5055-63. doi: 10.4238/2014.July.4.21, PMID 25061730.

Huh JE, Lee WI, Kang JW, Nam D, Choi DY, Park DS. Formononetin attenuates osteoclastogenesis via suppressing the rankl induced activation of NF-κB, c-Fos, and nuclear factor of activated T-cells cytoplasmic 1 signaling pathway. J Nat Prod. 2014 Nov 26;77(11):2423-31. doi: 10.1021/np500417d, PMID 25397676.

Jiang B, Kronenberg F, Balick MJ, Kennelly EJ. Analysis of formononetin from black cohosh (Actaea racemosa). Phytomedicine. 2006 Jul;13(7):477-86. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2005.06.007, PMID 16785040.

Ming LG, Chen KM, Xian CJ. Functions and action mechanisms of flavonoids genistein and icariin in regulating bone remodeling. J Cell Physiol. 2013 Mar;228(3):513-21. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24158, PMID 22777826.

Wang ST, Chang HS, Hsu C, SU NW. Osteoprotective effect of genistein 7-O-phosphate a derivative of genistein with high bioavailability in ovariectomized rats. J Funct Foods. 2019 Jul 1;58:171-9.

Winzer M, Rauner M, Pietschmann P. Glycitein decreases the generation of murine osteoclasts and increases apoptosis. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2010;160(17-18):446-51. doi: 10.1007/s10354-010-0811-4, PMID 20714813.

QU LP, Fan GR, Peng JY, MI HM. Isolation of six isoflavones from semen sojae praeparatum by preparative HPLC. Fitoterapia. 2007 Apr;78(3):200-4. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2006.11.002, PMID 17343991.

HU HY, Zhang ZZ, Jiang XY, Duan TH, Feng W, Wang XG. Hesperidin anti-osteoporosis by regulating estrogen signaling pathways. Molecules. 2023 Oct 9;28(19):6987. doi: 10.3390/molecules28196987, PMID 37836830.

Kilor VA. Design and development of novel microemulsion based topical formulation of hesperidin. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2015;7(12):142-8.

Xue L, Jiang Y, Han T, Zhang N, Qin L, Xin H. Comparative proteomic and metabolomic analysis reveal the antiosteoporotic molecular mechanism of icariin from Epimedium brevicornu maxim. J Ethnopharmacol. 2016 Nov 4;192:370-81. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.07.037, PMID 27422162.

Zhou F, Mei J, Yuan K, Han X, Qiao H, Tang T. Isorhamnetin attenuates osteoarthritis by inhibiting osteoclastogenesis and protecting chondrocytes through modulating reactive oxygen species homeostasis. J Cell Mol Med. 2019 Jun;23(6):4395-407. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14333, PMID 30983153.

Suleiman RK, Umoren SA, Iali W, El Ali B. Isolation of new constituents from whole plant of salsola imbricataforssk of Saudi Origin. ACS Omega. 2022 Jun 14;7(23):20332-8. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.2c02332, PMID 35721930.

Yang L, Chen Q, Wang F, Zhang G. Antiosteoporotic compounds from seeds of Cuscuta chinensis. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011 May 17;135(2):553-60. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.03.056, PMID 21463675.

Hakem A, Desmarets L, Sahli R, Malek RB, Camuzet C, François N. Luteolin isolated from Juncus acutus L. a potential remedy for human coronavirus 229E. Molecules. 2023 May 23;28(11):4263. doi: 10.3390/molecules28114263, PMID 37298740.

Quan H, Dai X, Liu M, WU C, Wang D. Luteolin supports osteogenic differentiation of human periodontal ligament cells. BMC Oral Health. 2019 Oct 26;19(1):229. doi: 10.1186/s12903-019-0926-y, PMID 31655580.

Gui H, Dai J, Tian J, Jiang Q, Zhang Y, Ren G. The isolation of anthocyanin monomers from blueberry pomace and their radical scavenging mechanisms in DFT study. Food Chem. 2023 Aug 30;418:135872. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.135872, PMID 37001355.

Mao W, Huang G, Chen H, XU L, Qin S, LI A. Research progress of the role of anthocyanins on bone regeneration. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:773660. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.773660, PMID 34776985.

Fan S, Gao X, Chen P, LI X. Myricetin ameliorates glucocorticoid induced osteoporosis through the ERK signaling pathway. Life Sci. 2018 Aug 15;207:205-11. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2018.06.006, PMID 29883721.

Jeyaraj EJ, Lim YY, Choo WS. Extraction methods of butterfly pea (Clitoria ternatea) flower and biological activities of its phytochemicals. J Food Sci Technol. 2021 Jun;58(6):2054-67. doi: 10.1007/s13197-020-04745-3, PMID 33967304.

Mohd Ramli ES, Suhaimi F, Ahmad F, Shuid AN, Mohamad N, Ima Nirwana S. piper sarmentosum: a new hope for the treatment of osteoporosis. Curr Drug Targets. 2013 Dec;14(14):1675-82. doi: 10.2174/13894501113146660228, PMID 24107234.

Sharma A, Bhardwaj P, Arya SK. Naringin: a potential natural product in the field of biomedical applications. Carbohydrate Polymer Technologies and Applications. 2021 Dec 25;2:100068. doi: 10.1016/j.carpta.2021.100068.

LI S, YU H, HO CT. Nobiletin: efficient and large quantity isolation from orange peel extract. Biomed Chromatogr. 2006;20(1):133-8. doi: 10.1002/bmc.540, PMID 15999338.

Tominari T, Hirata M, Matsumoto C, Inada M, Miyaura C. Polymethoxy flavonoids nobiletin and tangeretin prevent lipopolysaccharide induced inflammatory bone loss in an experimental model for periodontitis. J Pharmacol Sci. 2012;119(4):390-4. doi: 10.1254/jphs.11188sc, PMID 22850615.

Ren Z, Raut NA, Lawal TO, Patel SR, Lee SM, Mahady GB. Peonidin-3-O-glucoside and cyanidin increase osteoblast differentiation and reduce RANKL-induced bone resorption in transgenic medaka. Phytother Res. 2021 Nov;35(11):6255-69. doi: 10.1002/ptr.7271, PMID 34704297.

Ichiyanagi T, Kashiwada Y, Nashimoto M. Large scale isolation of three O-methyl anthocyanins from bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus L.) extract. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo). 2020 Nov 1;68(11):1113-6. doi: 10.1248/cpb.c20-00593, PMID 32879234.

Nagaoka M, Maeda T, Moriwaki S, Nomura A, Kato Y, Niida S. Petunidin a B-ring 5′-O-methylated derivative of delphinidin stimulates osteoblastogenesis and reduces sRANKL-induced bone loss. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 Jun 7;20(11):2795. doi: 10.3390/ijms20112795, PMID 31181661.

Huang YL, Shen CC, Shen YC, Chiou WF, Chen CC. Anti-inflammatory and antiosteoporosis flavonoids from the rhizomes of Helminthostachys zeylanica. J Nat Prod. 2017 Feb 24;80(2):246-53. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b01164, PMID 28169537.

Irnidayanti Y, Maharani DG, Rizky MH, Noer MI, Rizkawati V. Resveratrol-tempeh reduce micronucleus frequencies bone marrow cells and stimulate osteocyte proliferation in aluminum chloride induced mice. Braz J Biol. 2023 Feb 3;82:e266690. doi: 10.1590/1519-6984.266690, PMID 36753089.

Wang DG, Liu WY, Chen GT. A simple method for the isolation and purification of resveratrol from Polygonum cuspidatum. J Pharm Anal. 2013 Aug 1;3(4):241-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2012.12.001, PMID 29403824.

Abdel Naim AB, Alghamdi AA, Algandaby MM, Al Abbasi FA, Al Abd AM, Eid BG. Rutin isolated from Chrozophora tinctoria enhances bone cell proliferation and ossification markers. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2018 Feb 13;2018:5106469. doi: 10.1155/2018/5106469, PMID 29636845.

Seal T, Chaudhuri K. Effect of solvent extraction system on the antioxidant activities of some selected wild edible plants used by the ethnic people of Arunachal Pradesh. Int J Curr Pharm Rev Res. 2016;7(3):180-5.

Mak NK, Wong Leung YL, Chan SC, Wen J, Leung KN, Fung MC. Isolation of anti-leukemia compounds from Citrus reticulata. Life Sci. 1996;58(15):1269-76. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(96)00088-4, PMID 8614280.

Liu X, Liu W, Ding C, Zhao Y, Chen X, Ling D. Taxifolin extracted from waste larix olgensis roots attenuates CCl4-induced liver fibrosis by regulating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR and TGF-β1/Smads signaling pathways. Drug Des Dev Ther. 2021;15:871-87. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S281369, PMID 33664566.

Bansal K, Bhati H, Vanshita BM, Bajpai M. New insights into therapeutic applications and nanoformulation approaches of hesperidin: an updated review. Pharmacological Research Modern Chinese Medicine. 2024 Mar;10:100363. doi: 10.1016/j.prmcm.2024.100363.

Hosawi S. Current update on role of hesperidin in inflammatory lung diseases: chemistry pharmacology and drug delivery approaches. Life (Basel). 2023 Apr 3;13(4):937. doi: 10.3390/life13040937, PMID 37109466.

Choi SS, Lee SH, Lee KA. A comparative study of hesperetin hesperidin and hesperidin glucoside: antioxidant anti-inflammatory and antibacterial activities in vitro. Antioxidants (Basel). 2022 Aug 20;11(8):1618. doi: 10.3390/antiox11081618, PMID 36009336.

LI C, Schluesener H. Health promoting effects of the citrus flavanone hesperidin. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2017 Feb 11;57(3):613-31. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2014.906382, PMID 25675136.

Stanisic D, Liu LH, Dos Santos RV, Costa AF, Duran N, Tasic L. New sustainable process for hesperidin isolation and anti-ageing effects of hesperidin nanocrystals. Molecules. 2020 Oct 3;25(19):4534. doi: 10.3390/molecules25194534, PMID 33022944.

Ortiz A DE C, Fideles SO, Reis CH, Bellini MZ, DE Pereira ES, Pilon JP. Therapeutic effects of citrus flavonoids neohesperidin hesperidin and its aglycone hesperetin on bone health. Biomolecules. 2022 Apr 23;12(5):626. doi: 10.3390/biom12050626, PMID 35625554.

Grohmann K, Manthey JA, Cameron RG. Acid catalyzed hydrolysis of hesperidin at elevated temperatures. Carbohydr Res. 2000 Sep 8;328(2):141-6. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(00)00081-1, PMID 11028782.

Rosiak N, Wdowiak K, Tykarska E, Cielecka Piontek J. Amorphous solid dispersion of hesperidin with polymer excipients for enhanced apparent solubility as a more effective approach to the treatment of civilization diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Dec 2;23(23):15198. doi: 10.3390/ijms232315198, PMID 36499518.

Majumdar S, Srirangam R. Solubility stability physicochemical characteristics and in vitro ocular tissue permeability of hesperidin: a natural bioflavonoid. Pharm Res. 2009 May;26(5):1217-25. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9729-6, PMID 18810327.

Altunayar Unsalan C, Unsalan O, Mavromoustakos T. Molecular interactions of hesperidin with DMPC/cholesterol bilayers. Chem Biol Interact. 2022 Oct 1;366:110131. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2022.110131, PMID 36037876.

Wdowiak K, Walkowiak J, Pietrzak R, Bazan Wozniak A, Cielecka Piontek J. Bioavailability of hesperidin and its aglycone hesperetin compounds found in citrus fruits as a parameter conditioning the pro-health potential (neuroprotective and antidiabetic activity) mini-review. Nutrients. 2022 Jun 26;14(13):2647. doi: 10.3390/nu14132647, PMID 35807828.

Pyrzynska K. Hesperidin: a review on extraction methods stability and biological activities. Nutrients. 2022 Jun;14(12):2387. doi: 10.3390/nu14122387, PMID 35745117.

Guazelli CF, Fattori V, Ferraz CR, Borghi SM, Casagrande R, Baracat MM. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of hesperidin methyl chalcone in experimental ulcerative colitis. Chem Biol Interact. 2021 Jan 5;333:109315. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2020.109315, PMID 33171134.

Yang HL, Chen SC, Senthil Kumar KJ, YU KN, Lee Chao PD, Tsai SY. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory potential of hesperetin metabolites obtained from hesperetin administered rat serum: an ex vivo approach. J Agric Food Chem. 2012 Jan 11;60(1):522-32. doi: 10.1021/jf2040675, PMID 22098419.

Golboyu BE, Erdogan MA, Cosar MA, Balıkoglu E, Erbas O. Diosmin and hesperidin have a protective effect in diabetic neuropathy via the FGF21 and galectin-3 pathway. Medicina (Kaunas). 2024 Oct;60(10):1580. doi: 10.3390/medicina60101580, PMID 39459367.

Hong W, Zhang W. Hesperidin promotes differentiation of alveolar osteoblasts via Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 2020 Oct;40(5):442-8. doi: 10.1080/10799893.2020.1752718, PMID 32308087.

Grimaud E, Soubigou L, Couillaud S, Coipeau P, Moreau A, Passuti N. Receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand (RANKL)/osteoprotegerin (OPG) ratio is increased in severe osteolysis. Am J Pathol. 2003 Nov;163(5):2021-31. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63560-2, PMID 14578201.

Zhang M, Chen D, Zeng N, Liu Z, Chen X, Xiao H. Hesperidin ameliorates dexamethasone induced osteoporosis by inhibiting p53. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022 Apr 11;10:820922. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2022.820922, PMID 35478958.

Chiba H, Uehara M, WU J, Wang X, Masuyama R, Suzuki K. Hesperidin a citrus flavonoid inhibits bone loss and decreases serum and hepatic lipids in ovariectomized mice. J Nutr. 2003 Jun;133(6):1892-7. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.6.1892, PMID 12771335.

Horcajada MN, Habauzit V, Trzeciakiewicz A, Morand C, Gil-Izquierdo A, Mardon J. Hesperidin inhibits ovariectomized induced osteopenia and shows differential effects on bone mass and strength in young and adult intact rats. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2008;104(3):648-54. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00441.2007.

Zhang Q, Song X, Chen X, Jiang R, Peng K, Tang X. Antiosteoporotic effect of hesperidin against ovariectomy induced osteoporosis in rats via reduction of oxidative stress and inflammation. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2021 Aug;35(8):e22832. doi: 10.1002/jbt.22832, PMID 34028927.

Martin BR, McCabe GP, McCabe L, Jackson GS, Horcajada MN, Offord Cavin E. Effect of hesperidin with and without a calcium (Calcilock) supplement on bone health in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016 Mar;101(3):923-7. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-3767, PMID 26751193.

Dayanandan AP, Cho WJ, Kang H, Bello AB, Kim BJ, Arai Y. Emerging nano scale delivery systems for the treatment of osteoporosis. Biomater Res. 2023 Jul 13;27(1):68. doi: 10.1186/s40824-023-00413-7, PMID 37443121.

Marimuthu A, Seenivasan R, Pachiyappan JK, Nizam I, Ganesh G. Synergy of science and tradition: a nanotechnology driven revolution in natural medicine. Int J App Pharm. 2024;16(6):10-20. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2024v16i6.50767.

Pradhan SP, Sahoo S, Behera A, Sahoo R, Sahu PK. Memory amelioration by hesperidin conjugated gold nanoparticles in diabetes induced cognitive impaired rats. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2022 Mar 1;69:103145. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2022.103145.

Sarabia Vallejo A, Caja MD, Olives AI, Martin MA, Menendez JC. Cyclodextrin inclusion complexes for improved drug bioavailability and activity: synthetic and analytical aspects. Pharmaceutics. 2023 Sep 19;15(9):2345. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics15092345, PMID 37765313.

Hayat A, Shah I, Jabbar A, Nafady A, Balouch A, Shah MR. Enhanced wound healing activity in animal model via developing and designing of self nano emulsifying drug delivery system (SNEDDS) for the co-delivery of hesperidin and Rutin. J Clust Sci. 2024 Dec 1;35(8):2721-34. doi: 10.1007/s10876-024-02679-w.

Yaghoubi N, Gholamzad A, Naji T, Gholamzad M. In vitro evaluation of PLGA loaded hesperidin on colorectal cancer cell lines: an insight into nano delivery system. BMC Biotechnol. 2024 Aug 2;24(1):52. doi: 10.1186/s12896-024-00882-1, PMID 39095760.

Dastanpour L, Kamali B, Ebrahimi G, Tadavani PK, Bashiri F, Pourjavadi A. Nanogram scale co-delivery of hesperidin and bicelin with high performance by redox and NIR-responsive nanotheranostic carrier. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2024 Nov 1;101:106139. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2024.106139.

Almukainzi M, El Masry TA, El Zahaby EI, El Nagar MM. Chitosan/hesperidin nanoparticles for sufficient compatible antioxidant and antitumor drug delivery systems. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2024 Jul 29;17(8):999. doi: 10.3390/ph17080999, PMID 39204104.

LI J, Wang X, Guo H, Zhou H, Sha S, Yang Y. Immunostimulant citrus fruit derived extracellular vesicle nanodrugs for malignant glioma immunochemotherapy. Chem Eng J. 2024 Mar 15;484:149463. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2024.149463.

Sun X, Yang H, Zhang H, Zhang W, Liu C, Wang X. Magnetic gelatin hesperidin microrobots promote proliferation and migration of dermal fibroblasts. Front Chem. 2024 Oct 10;12:1478338. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2024.1478338, PMID 39449692.

Kodous AS, Abdel Maksoud MA, El Tayeb MA, Al Sherif DA, Mohamed SS, Ghobashy MM. Hesperidin loaded PVA/alginate hydrogel: targeting NFκB/iNOS/COX-2/TNF-α inflammatory signaling pathway. Front Immunol. 2024 Apr 15;15:1347420. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1347420, PMID 38686374.

Jangde R, Elhassan GO, Khute S, Singh D, Singh M, Sahu RK. Hesperidin loaded lipid polymer hybrid nanoparticles for topical delivery of bioactive drugs. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2022 Feb 10;15(2):211. doi: 10.3390/ph15020211, PMID 35215324.

Sharaf M, Arif M, Khan S, Abdalla M, Shabana S, Chi Z. Co-delivery of hesperidin and clarithromycin in a nanostructured lipid carrier for the eradication of helicobacter pylori in vitro. Bioorg Chem. 2021 Jul 1;112:104896. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2021.104896, PMID 33901764.

LI Y, Kandhare AD, Mukherjee AA, Bodhankar SL. Acute and sub-chronic oral toxicity studies of hesperidin isolated from orange peel extract in sprague dawley rats. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2019 Jul 1;105:77-85. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2019.04.001, PMID 30991075.

Sharma P, Kumari S, Sharma J, Purohit R, Singh D. Hesperidin interacts with CREB-BDNF signaling pathway to suppress pentylenetetrazole induced convulsions in zebrafish. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:607797. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.607797, PMID 33505312.