Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 3, 2025, 28-54Review Article

AN OVERVIEW OF COPD: ITS ADVANCED THERAPEUTIC MANAGEMENT AND CHALLENGES FOR DRUG RELEASE AT THE TARGETED SITE

SUPRAJA A.a , GUNDAWAR RAVIa

, GUNDAWAR RAVIa , TANVI PAINGINKARa

, TANVI PAINGINKARa , GIRISH PAI K.b

, GIRISH PAI K.b , VIRENDRA S. LIGADEc

, VIRENDRA S. LIGADEc , K. SREEDHARA RANGANATH PAId

, K. SREEDHARA RANGANATH PAId , VASANTHARAJU SGa

, VASANTHARAJU SGa , MUDDUKRISHNA BSa*

, MUDDUKRISHNA BSa*

aDepartment of Pharmaceutical Quality Assurance, Manipal College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal-576104, Karnataka, India. bDepartment of Pharmaceutics, Manipal College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal-576104, Karnataka, India. cDepartment of Pharmaceutical Management and Regulatory Affairs, Manipal College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal-576104, Karnataka, India. dDepartment of Pharmacology, Manipal College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, 576104-Karnataka, India

*Corresponding author: Muddukrishna BS; *Email: krishna.mbs@manipal.edu

Received: 04 Oct 2024, Revised and Accepted: 28 Mar 2025

ABSTRACT

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disorder (COPD) is a diverse lung ailment characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms such as coughing, dyspnea, sputum formation, and worsening that causes increased airflow limitation. Globally, COPD ranks third in 2019 and is responsible for 3.23 million deaths. It is a health problem that is brought on by inflammation in the lungs. The respiratory system comprises the trachea, bronchi, larynx, paranasal sinuses, and two lungs. COPD and other Respiratory Disorders (RDs) have dominated research. This review emphasizes the potential of novel treatment strategies for COPD, highlighting advanced therapeutic approaches. It addresses the ongoing challenges associated with the effective delivery of pharmaceuticals to targeted sites while aiming to achieve optimal therapeutic outcomes with reduced dosages. The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) Report 2024 categorizes COPD treatments into pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions. Pharmacological therapies aim to alleviate symptoms, enhance exercise tolerance, reduce exacerbations, and improve health outcomes. These include antibiotics, Long-Acting Beta-Agonist (LABA), Short-Acting Beta-Agonist (SABA), Long-Acting Muscarinic-Antagonists (LAMA), Short-Acting Muscarinic-Antagonists (SAMA), Inhaled Corticosteroids (ICS), and bronchodilators in various formulations. The report also reviews inhaler types and highlights the role of nanoscale drug delivery systems in detecting drug particle deposition in the respiratory tract, along with the characterization and classification of Nanoparticles (NPs) in nanomedicine. In conclusion, contemporary nanoparticles enhance biodistribution, optimize pharmacokinetics, and promote physiological stimulation. They also reduce toxicity and increase the therapeutic index, thereby facilitating the transformation of medication administration for chronic respiratory disorders.

Keywords: COPD, GOLD, Particle size, Nanoparticles, Inhaled corticosteroids, DPIs, Advanced therapies

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i3.53675 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Numerous studies have examined Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disorder (COPD) and Respiratory Disorders (RDs). The respiratory system includes the lungs, paranasal sinuses, trachea, bronchi, throat, and larynx. (RDs) impair breathing and affect the lungs and other components. These can range from life-threatening conditions such as pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, tuberculosis, COPD, and lung cancer to milder infections like the flu. RDs can be classified based on their etiology, affected tissues, and symptom patterns [1–3]. Lung disease symptoms are categorized into three types: obstructive (asthma, COPD, bronchitis), tissue-related (fibrosis, pneumonia, COPD, lung cancer), and circulatory issues (pulmonary hypertension, embolism, edema) [4–9]. COPD is a lung disorder marked by persistent cough, shortness of breath, and sputum production. It is caused by chronic bronchitis and emphysema due to alveoli damage, and irritating particles can affect lung flexibility and airflow [10, 11]. COPD is the sixth most common chronic illness globally, causing 90% of adult deaths in low-and middle-income countries. Tobacco smoking is the leading cause, accounting for 70% of cases in high-income and 30% to 40% in low-and middle-income countries [9]. Indoor exhaust affects 25% of smokers, with air pollution and workplace exposure as additional risks. Inhaled toxins cause lung inflammation and tissue damage in COPD patients, worsening the condition even after quitting smoking and disrupting the balance of lung defenses [10–13]. Emphysema and airway diseases cause gas trapping and blockage, leading to COPD [14–16]. Hyperinflation involves increased lung gas volume, causing dyspnea, reduced exercise tolerance, and hospitalizations [17–19]. Abnormalities related to pulmonary gas exchange, such as smooth muscle hypertrophy and intimal hyperplasia, may also manifest [20–23]. COPD can get worse due to respiratory symptom exacerbations, such as worsening dyspnea and declining VA/Q abnormalities [24–26]. Additionally, survival and health may be impacted by multimorbidity [26, 27]. Mast cells induce inflammation and bronchoconstriction by releasing histamine and arachidonic acid metabolites. Cysteinyl leukotrienes increase intracellular calcium via the cysLT1 receptor. In asthma, adenosine reduces cyclic AMP, causing smooth muscle contraction. Airway regulation involves parasympathetic (muscarinic M3 receptor) and sympathetic (β2-adrenergic receptor) fibers [28–36]. The diagnosis of COPD is made using imaging, physiological tests, and spirometry [37]. Pulmonary function tests are primarily conducted using spirometry. This method assesses the air volume inhaled and exhaled, producing pneumotachographs illustrating air movement during breathing [38, 39]. In 2019, COPD was responsible for 3.23 million deaths, ranking as the third leading cause of death globally, according to the WHO [40]. Each year, the Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) publishes a comprehensive report on the management options for COPD, a valuable resource for healthcare professionals. In addition, numerous global and national guidelines have been released, which focus on the specific characteristics of regional healthcare systems [41–50].

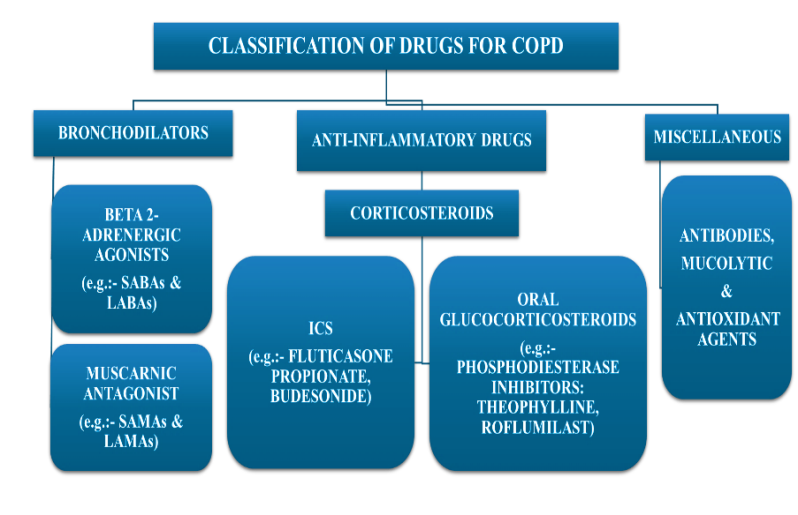

Moving on to the briefly discussed developing innovative treatment options, the objectives of pharmacological therapy for COPD are to improve general health, reduce the intensity and frequency of exacerbations, boost exercise tolerance, and lessen symptoms. In individuals with stable COPD who are unwell, influenza vaccines are necessary. Subgroups comprise the maintenance medications for A. bronchodilators: i. β2-Adrenergic Agonists, ii. Muscarinic Antagonists, B. Anti-inflammatory drugs: a. Corticosteroids-i. Inhaled Corticosteroids (ICS), ii. Oral Corticosteroids, iii. Phosphodiesterase Inhibitors and antibiotics with other appropriate dosage formulations, such as single-drug therapy and combination-drug therapy, triple-drug formulations [38, 51, 52]. Routine treatment must be changed in response to acute exacerbations, intermittent bouts of decreasing respiratory function and increasing symptoms associated with COPD [38, 39, 53–57]. An outline of the many types of COPD inhalers available. Several novel and contemporary inhalers [53, 58] were used for DPIs of medication particle deposition in respiratory tract sections [59–61]. The Nanoscale systems with their significance and barriers for delivering drugs to the aimed locations [62]. Information on nanomedicine, including studies on the characterization and classification of various Nanoparticles (NPs) [63, 64].

RDs

The throat, larynx, trachea, bronchi, nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses, and two lungs-bronchioles and alveoli compose the respiratory system. Pathological disorders that harm the lungs and other respiratory system components and make breathing difficult are known as RDs. These include diseases of the trachea, bronchi, bronchioles, alveoli, pleurae, pleural cavity, and respiratory muscles and nerves. From harmless and self-limiting illnesses like the flu, influenza, and pharyngitis to potentially lethal disorders like pneumonia due to bacteria, pulmonary embolism, tuberculosis, COPD, lung cancer, and other severe acute respiratory syndromes, there are many different types of respiratory maladies. RD can be categorized based on the etiology of the diseases, parts or tissues affected, and pattern of symptoms [1–3].

Based on the etiology of diseases

Obstructive lung diseases are caused by excessive contraction of smooth muscles, leading to constriction of bronchi and bronchioles. The main characteristics involved are inflamed and readily collapsible airways, airflow blockage, difficulty exhaling, and frequent hospitalizations. Bronchitis, asthma, and COPD diseases are classic examples of this category. Lung tissue diseases can be characterized by damage to the pleura, a thin tissue layer of the lungs, enabling lungs to expand to regular size, leading to impaired breathing. Pulmonary Fibrosis (scarring of lung tissues), pneumonia (inflamed air sacs), COPD (emphysema), and lung cancer (uncontrolled growth of lung tissues) are examples of lung tissue diseases (fig. 1). Lung circulation diseases occur when the lungs' blood vessels are coagulated, damaged, or swollen, causing an imbalance in the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide. Pulmonary hypertension, Pulmonary embolism, and Pulmonary edema all belong to this category [65, 66].

Based on the symptoms

Each lung disease category will have characteristic symptoms. Wheezing, a wet cough, and trouble breathing are symptoms of obstructive lung diseases (bronchitis, COPD, and asthma); symptoms of lung tissue diseases (fibrosis, pneumonia, COPD, lung cancer) include dyspnea with a dry cough; exhaustion, shortness of breath, and chest discomfort are signs of lung circulatory disorders (pulmonary-hypertension, embolism, edema) [4–9].

Fig. 1: Classification of RDs based on the etiology of diseases (BioRender.com)

COPD

Persistent respiratory symptoms, including coughing, dyspnea, sputum production, and exacerbation leading to increasing airflow restriction, are the hallmarks of the heterogeneous lung illness called COPD. It is characterized by damaged alveoli of the lungs, a condition known as emphysema, and/or inflammation of the bronchi/bronchioles termed chronic bronchitis (fig. 2) [10, 11]. With the start of an inflammatory response imposed on by irritant particles in the respiratory tract, COPD is defined by the onset of irreversible inflammation and harm to the air sacs in the lungs, resulting in constriction of the airways.

The lungs become more flexible because of these physiological changes, holding onto more air and obstructing more airflow.

Signs and symptoms

A few of the commonly recognized symptoms include breathing difficulties, particularly when moving, wheezing, chest tightness, and a persistent cough that may produce clear, white, yellow, or greenish mucous or sputum; recurrent respiratory infections; deliberate weight loss (later stages); and swelling in the ankles, legs, or feet.

Shortness of breath-The most defining feature of COPD is its persistent, increasing dyspnoea. Breathlessness symptoms such as wheezing and tightness in the chest might fluctuate during the day or between days and are not always present. Often, chest discomfort occurs after exertion. Low levels of physical exercise are linked to inferior outcomes, and shortness of breath is frequently the cause of limited physical activity [54, 67].

Cough-The initial symptom of COPD is a persistent cough, which could or might not produce phlegm. Diagnosing phlegm coughed up as sputum can be challenging since it might be sporadic and, depending on social or cultural variables, swallowed or spit out. Only up to 30% of patients, meanwhile, also have a productive cough. In some instances, restricted breathing may occur without a cough. When a persistent cough lasts for more than three months and each year for a minimum of two years, it is classified as chronic bronchitis. A persistent productive cough is caused by mucus hypersecretion. Vigorous coughing in those with severe COPD might break ribs or cause momentary unconsciousness [54].

Exacerbations-An abrupt worsening of signs and symptoms that last for a few days is called an acute exacerbation. A frequently observed indicator is air trapping, which makes it difficult to exhale completely. According to research, a pulmonary embolism may occasionally cause these occurrences. Heart failure and pleuritic chest discomfort without symptoms of infection are possible indicators [54].

Fig. 2: Characteristics of COPD include emphysema (destruction of the tiny air sacs-alveoli) and chronic bronchitis (inflammation of bronchi tubes with excess mucous). These are long-term lung conditions causing COPD (BioRender.com)

Causes

About 90% of adult COPD deaths under those over the age-70 occur in nations with low or middle incomes. COPD is the sixth most frequent cause of chronic disease worldwide, as measured by disability-adjusted life years. Tobacco smoking is the primary cause of almost 70% of instances of COPD in high-income nations. Tobacco use accounts for thirty to forty percent of cases in low-and middle-income countries, where indoor exhaust is a significant risk factor for COPD [9]. The leading cause of COPD, which affects up to 25% of cigarette users, is smoking. In addition, occupational contact with dust and fumes, as well as air pollution, can induce COPD [10].

Common risk factors

Smoking-Globally, tobacco use is the primary risk factor for COPD, and research has shown that smokers have an increased risk of the illness in ex-smokers [54, 68]. The main structural element of alveoli-elastin, is broken down by the overproduction of proteases in the lungs due to smoke inhalation. Smoke also affects cilia, preventing mucociliary clearance, which rids the airways of mucus, cell debris, and extra fluid [68]. As per the research, women are more vulnerable than men to the negative consequences of tobacco smoking [69]. Out of 8 million tobacco-related fatalities that occur globally each year, 1.2 million are caused by second-hand smoke, also known as passive smoking [70]. There is also a risk from other forms of tobacco smoke, such as those from pipes, cigars, water pipes, and hookahs [54]. Smoke from water pipes or hookahs seems to be just as toxic as cigarette smoke [71].

Additional lung irritants-Indoor air pollution from poorly ventilated fires is utilized for heating and heating, particularly in developing nations, where one of the leading causes of COPD involves cooking. Coal and biomass, like wood and dried manure, are commonly used to fuel these fires [54]. Individuals diagnosed with COPD are more vulnerable to the harmful consequences of particulate matter exposure, which may result in abrupt exacerbations of infections. Excessive hospitalization risk is linked to black carbon, also called soot, an atmospheric contaminant that causes exacerbations. An elevated mortality rate in COPD is related to prolonged exposure [72]. COPD rates are often more significant in areas with poor outdoor air quality, especially exhaust gas pollution [73].

Age-Most people with COPD are 40 years of age or older when their symptoms first manifest.

Respiratory infections-Two conditions that may make you more susceptible to infection include AIDS and tuberculosis.

Changes in lung development and expansion in the developing fetus-A child’s risk may be increased by diseases that damage the lungs during pregnancy or infancy and alter lung growth and development.

Occupational exposure-The risk of developing COPD due to intense and extended exposure to industrial dust, chemicals, and fumes. Dust from grains and wheat, silica, cadmium, and welding fumes aggravating respiratory symptoms are among the substances identified in the United Kingdom and linked to occupational exposure [54, 74]. In the United States, workplace exposure is thought to be related to around 30% of cases among those who have never smoked. It is believed to be the cause in 10–20% of cases and likely poses a higher risk in nations with insufficient laws [54, 75].

Rare risk factor

Genetics-About 1-5 % of COPD is influenced by genetics [76, 77]. AAT deficiency is a genetic condition that can lead to COPD and lung damage when it runs throughout the family. Smoking or prolonged exposure to dust or fumes can further exacerbate the condition. CHRNA gene mutations and vitamin D insufficiency are possible genetic risk factors [78–80].

The COPD Gene research is a long-term investigation of the epidemiology of the disease that identifies phenotypes and searches for potential gene associations with susceptibility to COPD. As of 2019, whole genome sequencing and the National Heart, Lungs, and Blood Institute collaborate to identify rare genetic determinants [81].

Pathology

With the start of an inflammatory response imposed on by dangerous gases and particles in the respiratory tract, COPD is defined by the onset of irreversible inflammation and harm in the air sacs in the lung while the airways constrict.

These changes in physiological function lead to increased lung compliance, air retention, and airflow obstruction-all of which are signs of COPD. Furthermore, they make it harder for air to pass via the tiny conducting airways [11, 12].

Pathogenesis

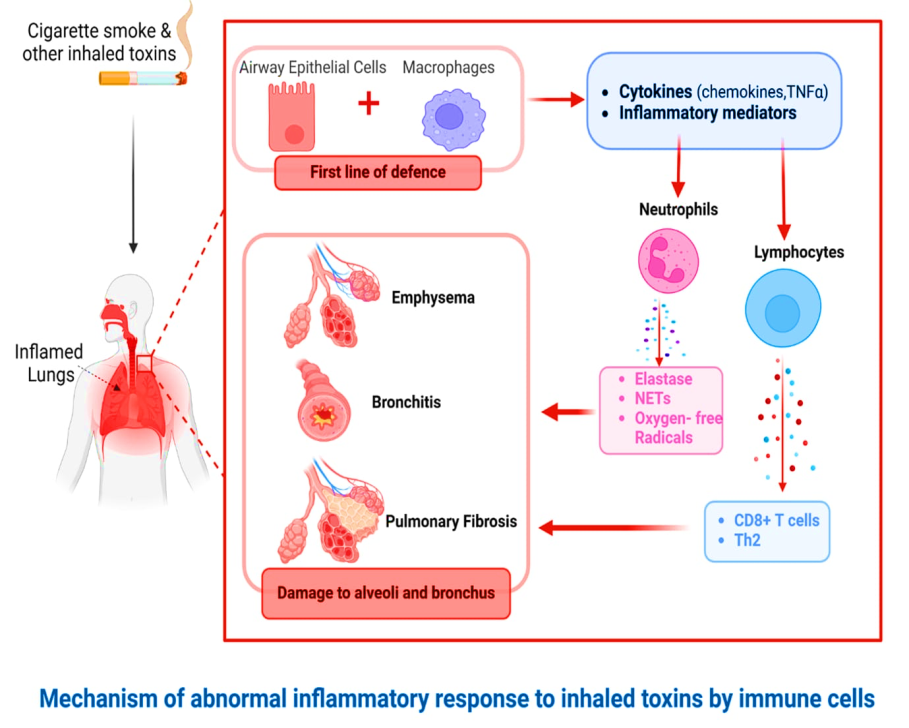

A frequent reaction to the inhaled toxins in COPD patients is lung inflammation, particularly in the small airways. This inflammation causes tissue death and impairs defense and healing mechanisms. Even after stopping smoking, these alterations can continue as the condition worsens. Furthermore, there is an imbalance in the lung's antiproteases, oxidants, antioxidants, and proteases [10–13].

Inflammatory cells-COPD is distinguished by increased lung inflammation, caused mainly by airflow restriction, as well as increased neutrophils, macrophages, and T-lymphocytes, all of which produce numerous cytokines and mediators, as opposed to asthma patients, who have a similar pattern [10–13].

Inflammatory mediators-Leukotriene B4, a chemoattractant for draws T cells and neutrophils, is produced by a rise in inflammatory mediators, including macrophages, neutrophils, and epithelial cells. Growth-related oncogene α and its CXC chemokines interleukin Eight and interleukin Eight are chemotactic factors produced by macrophages with epithelial cells. These stimulate pro-inflammatory responses and attract blood cells. Pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as tumour necrosis factor α and interleukins 1β and 6. A cytokine called connective tissue growth factor is released by growth factors such as transforming growth factor β, which can cause fibrosis in the airways either directly or indirectly [10–13].

Fig. 3: Diagram representing the various risk factors involved in developing COPD. Common factors are smoking, additional lung irritants, age, respiratory infections, fetus respiratory system status, and occupational exposure to dust, smoke, and chemicals. Rare factors include genetic factors like AAT deficiency (BioRender.com)

Fig. 4: Pathogenesis of Inflammation in COPD (BioRender.com)

Protease and antiprotease imbalance are caused by increased protease synthesis (or activity) and decreased antiprotease production (or inactivation). Oxidative stress is brought on by both inflammation and cigarette smoke, and it inactivates certain antiproteases and primes many inflammatory cells to produce a combination of proteases. Several metalloproteases found in the matrix MMP-8, MMP-9, and MMP-12 and proteases produced by neutrophils (elastase, cathepsin G, in addition protease 3) as well as macrophages consisting of the cysteine proteases and cathepsins E, A, L, and S are the principal proteases implicated. The main antiproteases linked to the pathogenesis of emphysema include tissue inhibitors of metalloproteases, secretory leucoprotease inhibitors, and α1 antitrypsin [10–13].

Oxidative stress-With COPD, the oxidative load is elevated. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species emitted by inflammatory cells and cigarette smoke are sources of oxidants. This leads to an imbalance in oxidative stress's antioxidant and oxidant populations. In stable COPD, several oxidative stress indicators are elevated, and during exacerbations, these markers rise even more. Mucus production may be stimulated, or antiproteases may become inactive because of oxidative stress. Furthermore, it can escalate inflammation by facilitating transcription factors (e.g., nuclear factor κB) and consequent generation of pro-inflammatory mediator genes [10–13, 15, 18, 82–84].

Fig. 5: Progression of COPD by the presence of oxidative and proteases (BioRender.com)

Pathophysiology

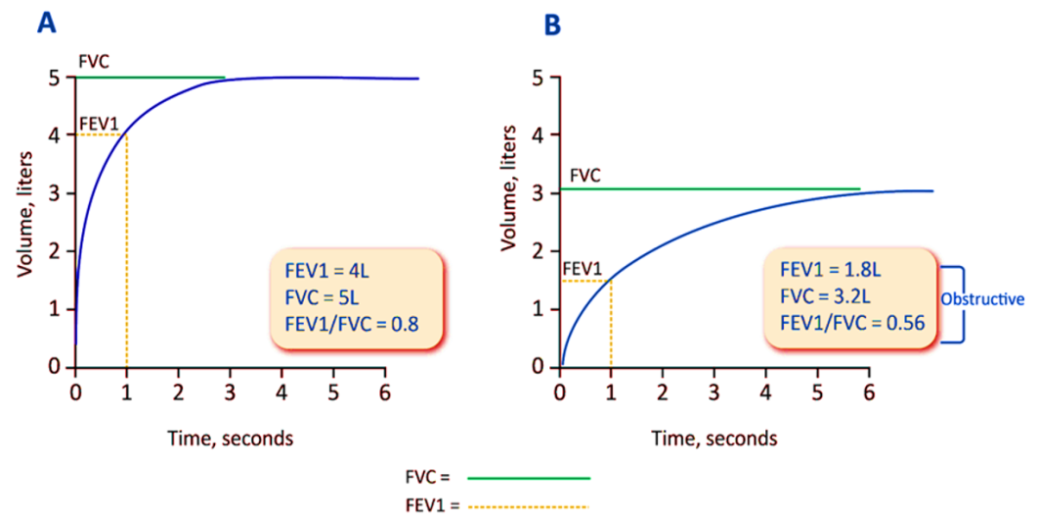

Airflow obstruction and gas trapping-small airway disease and parenchymal degeneration, including emphysema, which raises airway resistance and lowers lung elastic rebound, combined with COPD. The degree of these variables may change over time. Prolonged inflammation results in altered structure, luminal discharges, narrowing of minor airways, and deterioration of lung parenchyma, which diminishes lung elastic rebound and alveolar attachments to minor airways. Due to these modifications, airways are still less able to be opened during expiration, which can cause mucociliary dysfunction and airflow obstruction. Due to decreased lung growth or more significant airway loss, COPD patients may have fewer tiny airways. This increases the risk of gas entrapment and lung hyperinflation, shortens forced expiratory breathing, and lowers FEV1 and FEV1/FVC ratios [14–16].

Hyperinflation-When the gas volume of the lung is higher than usual, it is called hyperinflation. This condition affects individuals with COPD and causes symptoms including dyspnea, reduced exercise tolerance, increased hospitalization rates, respiratory failure, and poorer mortality. When the highest expiratory flows are created during spontaneous breathing, there is a limitation in expiratory flow and a lack of elastic rebound, which leads to this. Airway abnormalities and emphysematous parenchymal degradation are the causes of this blockage [17–19].

Pulmonary gas exchange abnormalities- Patients with COPD have altered ventilation-perfusion distributions because of structural variations in the pulmonary circulation, airways, and alveoli. Vascular hypoxemia in variable degrees and aberrant pulmonary gas exchange result from this. Acidosis and hypercapnic respiratory failure can result from decreased ventilation brought on by sedatives and hypnotic drugs that decrease ventilatory drive. Pneumatic gas exchange frequently deteriorates throughout the illness, and lung diffusing capacity is further reduced by parenchymal damage associated with emphysema [85, 86].

Pulmonary hypertension-Smokers and COPD patients with mild airflow obstruction might see abnormalities within the pulmonary circulation, such as intimal hyperplasia as well as smooth muscle hypertrophy/hyperplasia. These individuals exhibit endothelial cell failure and inflammatory reactions like those in the respiratory system. Significant pulmonary hypertension, however, is uncommon in people with COPD and is often brought on by pulmonary capillary bed loss from emphysema or hypoxic vasoconstriction. The result of increasing pulmonary hypertension is heart failure on the right side, or "cor pulmonale," which is accompanied by right ventricular hypertrophy. Survival may be hampered by serious complications of pulmonary hypertension [20–23].

Exacerbations- Patients with COPD may experience exacerbation of respiratory symptoms due to unknown reasons, environmental pollutants, and respiratory infections. Increased dyspnea, deteriorating VA/Q abnormalities, increased gas trapping, elevated airway inflammation, and hyperinflation are examples of exacerbations. A result of these circumstances might be arterial hypoxemia. Heart failure, lung, and pneumonia are a few additional conditions that can resemble or worsen COPD exacerbations. It is essential to treat these crises therapeutically [24–26].

Multimorbidity- Patients with COPD frequently have other chronic comorbid illnesses, such as age, inactivity, and smoking, which can harm their health and survival. Limiting airflow, particularly in the case of hyperinflation, can worsen heart failure, ischemic heart disease, osteoporosis, normocytic anaemia, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome, among other heart health issues. Cachexia and atrophy of the skeletal muscles may also be caused by inflammatory mediators in the circulation [26, 27].

Mechanism of action

When mast cells are triggered, histamine and freshly produced phospholipid (arachidonic acid metabolites), along with mediators, are released from stored granules. With the aid of phospholipase A2, arachidonic acid is released from membrane phospholipids during immunologic activation. Prostaglandins and leukotrienes are produced via the fast oxidation of arachidonic acid via the cyclooxygenase (COX) or lipoxygenase (LOX) pathways. In addition to causing inflammation, these mediators also produce bronchoconstriction. The most effective bronchoconstrictors have been identified and are so-called cysteinyl leukotrienes: LTC4, LTD4, and LTE4. They specifically enhance the intracellular calcium content and activate the Gq protein-coupled cysLT1 receptor found on bronchial smooth muscle cells to produce smooth muscle formation. Like dopamine, although to a lesser extent, histamine activates the Gq protein-couple H1 receptor to produce smooth muscle contraction. Now, it has been shown that people with asthma have higher-than-average amounts of adenosine within their lungs. By stimulating the G1 region of the protein-coupled adenosine A1 receptor, adenosine affects bronchial smooth muscle cells by lowering cyclic AMP levels and inducing smooth muscle contraction. In addition, sympathetic and parasympathetic nerve fibers that control contractions and relaxations are also innervated in the smooth muscle of the airways. Smooth muscle relaxation is facilitated by activating the Gs protein-coupled β2-adrenergic receptor by endogenous catecholamines produced by the sympathetic fibers, such as nor-and adrenaline. Conversely, the parasympathetic Fibers’ production of acetylcholine activates the muscarinic M3 receptor that is connected to the Gq protein, increasing intracellular calcium levels and thus causing smooth muscle contraction [28–36].

Fig. 6: Mechanism of action (BioRender.com)

Diagnostic tools of COPD

Diagnosing the condition should be the goal for any patient exhibiting dyspnea, persistent coughing, sputum production, and a history of risk factors for the sickness. To diagnose COPD, forced spirometry must be performed and show that the post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC<0.7 [37]. Peak expiratory flow measurement has a very high sensitivity, but its specificity is low enough that it cannot be employed as the sole diagnostic test [87]. Forced spirometry measures the following: Three measures are made: (1) forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), the amount of air exhaled during the first second of the maneuver; (2) forced vital capacity (FVC), the amount of air forced out at the point of maximal inspiration; and (3) the ratio of these two measurements, or FEV1/FVC. Spirometry measurements are compared to reference values depending on gender, height, and age [88].

Fig. 7: A: Spirometry-normal tracing, B: Spirometry-Airflow obstruction; Due to airflow obstruction, patients with COPD usually have decreased FEV1 and, to a lesser extent, FVC (because of gas trapping) (BioRender.com)

When considering a diagnosis of COPD, GOLD has advised using post-bronchodilator readings by other national and international standards. Post-bronchodilator beliefs were previously thought that they were more appropriate over confirming a finding for fixed airflow blockage because they were supposed to be more dependable, helpful in deciding out asthma, and could help recognize volume responders alongside bronchodilators within whom the obstruction is confirmed through a rise in FVC administered by the drug [89]. However, it is widely known because a bronchodilator response has minimal relevance in distinguishing between asthma and COPD [90] that obstruction only evident on post-bronchodilator evaluations is rare and that pre-bronchodilator values are repeatable [91, 92]. Physicians might not perform spirometry because it takes longer to get post-bronchodilator values. GOLD suggests pre-bronchodilator spirometry as a preliminary test to ascertain whether an airflow restriction exists in those exhibiting symptoms. Pre-bronchodilator spirometry should be used before undergoing post-bronchodilator spirometry unless COPD is highly likely, around which situation an FVC volume response could indicate FEV1/FVC<0.7. Repeating the tests for pulmonary function after some time may be necessary as a follow-up to ascertain the cause of the patient's symptoms. Post-bronchodilator examination should be utilized to confirm COPD if any pre-bronchodilator readings show a blockage. Individuals with a FEV1 to FVC ratio pre-bronchodilator<0.7, which translates to>0.7 post-bronchodilator, are at a higher risk of developing COPD and should be thoroughly investigated [93].

Some more extra investigations

Additional testing should determine whether lung mechanics, development, or other comorbidities, such as ischemic heart disease, influence the patient's symptoms. This is especially important whenever the degree of airflow obstruction and the indicators noticed are different [38]. Along with these, some physiological tests include lung volumes, Measurement of arterial blood gas, oximetry, and the lungs' ability to diffuse carbon monoxide. Computerized Tomography imaging beneath chest X-ray along with many more like Interstitial lung abnormalities and alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency [38, 39].

Worldwide growth rate of COPD and global market for inhalers

According to the WHO, in 2019, COPD accounted for 6% of total deaths, making it the “3rd leading cause of death worldwide, causing 3.23 million deaths”. The global market for inhalers, which is estimated to develop at a “compound annual growth rate of 6.1% and reach USD 33,572.9 million by 2023”, is expected to rise [40].

The GOLD annually releases a report on COPD management strategies. Physicians utilize this report, which defines fundamental words and concepts, as a starting point for strategy. Nonetheless, several national and worldwide COPD management guidelines and recommendations have been produced and published in the past, with a greater emphasis on respecting the specific scope, structure, and unique features of local healthcare systems [41–50].

Therapies for COPD

According to the GOLD Report 2024, therapies are classified into two therapies for controlling and treating COPD: I) Pharmacological therapies and II) Non-Pharmacological therapies [38].

Pharmacological therapies

Based on the severity of symptoms and the risk of worsening them, the GOLD Report for 2024 recommends a personalized approach to starting therapy. Breathlessness, exercise restriction, and the frequency of exacerbations while undergoing maintenance therapy are the key symptoms that determine whether to escalate or de-escalate treatment. These recommendations, which offer a systematic approach to treatment, drew some support from data from randomized controlled trials. Nevertheless, these guidelines provide professional guidance according to clinical knowledge because they are intended to help doctors make decisions.

The patient's GOLD group should inform the initial course of pharmacological treatment. Patients present symptom severity as measured by the COPD Assessment Test, the Dyspnea Scale, or the Modified Medical Research Council values. The frequency of exacerbations should be assessed at appropriate intervals (longer for fewer patients, shorter for severe patients). Comorbidities should be reevaluated, along with the treatment's impact and potential side effects.

Review of the inhaler technique, compliance with pharmaceutical and non-pharmacological suggested treatment, current smoking habits, and ongoing contact with hazards should all be part of every clinician session. Promoting physical activity and investigating pulmonary rehabilitation in extreme circumstances are both critical. Each of the following needs to be evaluated independently: lung volume reduction, oxygen therapy, safe support for breathing, and palliative interventions. The action plan should then be modified appropriately. It is recommended that spirometry be performed at least annually. Stopping the patient's bronchodilator medication if they are currently using it while doing spirometry is not recommended.

Table 1: Pharmacological therapies for COPD

| Pharmacological therapies | Reference | ||

| More than two mild exacerbations or more than one that requires hospitalization | “GROUP E” LABA+LAMA* If the blood eos is less than 300, consider LABA+LAMA+ICS*. |

[38] | |

| Moderate exacerbation (0 or 1) (without requiring hospital admission) | “GROUP A” Bronchodilators |

“GROUP B” LABA+LAMA* |

|

| mMRC 0–1, CAT less than 10 | Patients with a mmol RC score of 2 or higher and a CAT score of 10 or more. |

Group A

Bronchodilators can be administered to all Group A patients with short-acting or long-acting administration. Unless a patient experiences dyspnea often, long-acting bronchodilators are advised if they are accessible and cheap [38].

Group B

A combination of LABA and LAMA should be the initial treatment option. According to a randomized controlled trial, using LABA+LAMA for patients with a CAT™ score of ≥ 10 is more effective than using LAMA alone regarding various outcomes, especially for patients who experienced at least one moderate exacerbation the year before the study. Thus, LABA+LAMA is the first pharmacological option that is advised if there are no problems with availability, cost, or adverse effects. The available information does not support prescribing one kind of long-acting bronchodilator over another to patient group B to relieve the first symptoms. The patient's feelings should guide decisions. The prognosis and symptomatology may deteriorate due to complementary disorders [94–96].

Group E

The most effective treatment for COPD exacerbations, assuming no issues with cost, availability, or side effects, is the combination of LABA and LAMA, as stated in a Cochrane systematic review and network meta-analysis. For group E patients, the recommended first-line therapy is LABA+LAMA; however, if an ICS is necessary, it's advised to use LABA+LAMA+ICS due to its superior efficacy. In group E, the text suggests LABA+LAMA+ICS for patients whose eosinophil count is fewer than 300 cells/µl. The following section will examine the relationship between blood eosinophil count and how ICS affects exacerbations. As for starting triple therapy as the principal line of therapy for those suffering from elevated eosinophil levels in those who have just received a diagnosis, there is presently insufficient data to support this practice. Patients should get the same care as those with asthma if they also have COPD [38, 97–99].

When it came to reducing the death rate of COPD patients, neither the SUMMIT research nor the TORCH clinical trial could show that a mixture of LABA and ICS was better than a placebo. The intention-to-treat analysis in the UPLIFT research did not decrease mortality compared to placebo since most individuals took an ICS [100, 101]. Compared to dual inhaled long-acting bronchodilation treatment, fixed-dose inhalation tri combinations (LABA+LAMA+ICS) have been shown in two randomized clinical studies, IMPACT and ETHOS, to reduce all-cause mortality [102, 103].

Bronchodilators

The drugs are known as bronchodilators, which enhance FEV1 and/or modify other spirometry parameters. They work by altering the tone of the smooth muscle within the airways, and rather than altering lung elastic recoil, the improvements in overall expiratory flow result from airway widening. During exercise and rest, bronchodilators often lessen dynamic hyperinflation and enhance exercise efficiency. From the improvement in resting FEV1, it is difficult to estimate the degree of these improvements, particularly in individuals with severe and very severe COPD [38]. While administering an anticholinergic/beta2-agonist by nebulizer offers a subjective advantage during acute episodes, it may not be beneficial when the illness is stable. An order of magnitude increases in dosage. The most common use of bronchodilator drugs in COPD patients is regularly to either avoid or lessen symptoms. In addition, toxicity relates to dose. Regular use of short-acting bronchodilators is generally not advised [104–110].

Fig. 8: Classification of drugs for COPD (BioRender.com) [38, 51, 52]

β2- Adrenergic agonist

To provide a functional antagonistic reaction against bronchoconstriction, beta2-agonists primarily work by activating beta2-adrenergic receptors, which raises cyclic AMP. Airway smooth muscle is relaxed as a result. LABA and SABA are the two types of beta2-agonists available. 4–6 h are usually when SABAs start to lose their effects. FEV1 and symptoms are improved when SABA is used regularly as needed. LABAs have an impact that lasts for at least 12 h, and they don't stop subsequent benefits from more SABA treatment when it's required. Salmeterol and formoterol, two twice-daily LABAs, dramatically reduce mortality and the rates when lung function gets worse. They also reduce the rate of exacerbations, hospitalizations, dyspnea, and general health issues. Indacaterol, a once-daily LABA, has been shown to effectively alleviate shortness of breath, enhance overall health, and reduce the frequency of exacerbations. Indacaterol inhalation can cause persistent coughing in certain people. Oladaterol and vilanterol are among the extra once-daily LABAs that enhance lung function and alleviate symptoms [108, 110–120].

Muscarinic antagonists

The drug prevents acetylcholine from constricting the airways by inhibiting M3 muscarinic receptors within the smooth muscle in the airways. Like oxitropium and ipratropium, SAMAs may encourage vagally produced bronchoconstriction. Among the LAMAs are revefenacin, tiotropium, aclidinium, umeclidinium, and glycopyrronium bromide. LAMAs increase how long bronchodilator action lasts [121]. An analysis of RCTs revealed that the short-acting muscarinic antagonist ipratropium had little benefit over the short-acting beta2-agonists regarding lung function, general health, and the requirement for oral steroids. Examples of LAMA drugs that enhance patient well-being and symptoms, reduce hospitalization and exacerbation rates, and boost the efficacy of pulmonary rehabilitation include tiotropium, umeclidinium, and revefenacin. Studies show that tiotropium is more effective than LABA therapy at reducing the frequency of exacerbations [121–127].

Anti-inflammatory agents

Corticosteroids

ICS

Corticosteroid responsiveness of COPD-associated inflammation appears restricted, according to in vitro studies. Furthermore, a few medications, such as macrolides, theophylline, and beta2-agonists, may help COPD patients' corticosteroid sensitivity to some extent [128–130]. Determining the effect's clinical relevance is still premature. According to in vivo data, more studies are required to elucidate the dose-response relationships as well as the long-term (>three years) safety of ICS for individuals with COPD [131]. These are two different treatment choices since using long-acting bronchodilators simultaneously as ICS might alter its effects in COPD patients. COPD patients, both present and former smokers, benefit from ICS treatment as far as both lung function and exacerbation rates; however, the effect size is more significant in heavy smokers compared to moderate or ex-smokers [132, 133].

Oral glucocorticoids

Among the many negative consequences of oral glucocorticoids is steroid myopathy [134], which in those with very severe COPD can worsen respiratory failure, muscle weakness, and reduced functioning. In patients hospitalized or presenting to ERs during acute exacerbations, systemic glucocorticoids have been demonstrated to enhance lung function and dyspnea while decreasing the risk of treatment failure and its recurrence [135]. However, there aren't enough long-term prospective studies on how oral glucocorticoids affect individuals with stable COPD. This indicates that while oral glucocorticoids help treat acute exacerbations of COPD, long-term, daily use of them should be avoided because the significant risk of systemic issues outweighs any potential benefits [136].

Phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE4) inhibitor

By inhibiting intracellular cyclic AMP breakdown, PDE4 inhibitors decrease inflammation. Oral roflumilast, taken once daily, lowers moderate to severe worsening in patients with severe to extremely serious COPD, persistent bronchitis, and exacerbations when combined with systemic corticosteroids. It can, however, affect lung function when used with long-acting bronchodilators or in individuals not adequately managed on fixed-dose LABA+ICS combinations. A higher chance of benefiting from roflumilast is shown among patients who have experienced prior acute exacerbations. No research hasn't been done directly comparing roflumilast with inhaled corticosteroids [137–143].

Long-acting bronchodilator medication combined with ICS

ICS and LABA together improve lung function and overall health more than either drug alone does when used in individuals with moderate to severe COPD who have exacerbations [144, 145]. Clinical studies that used all-cause mortality as their primary endpoint could not show that combination treatment had a statistically meaningful impact on survival [146, 147]. Compared with LABA alone, patients with at least one exacerbation for the year before the study were included in most trials that found a decreased exacerbation rate using a combination with a fixed dose of LABA+ICS [145]. The combination of LABA with ICS in conventional treatment was compared in a comprehensive RCT in an early healthcare setting in the United Kingdom. The study's main objective was to reduce moderate-to-severe deteriorating conditions by 8.4%. However, according to the data, the number of hospital admissions and pneumonia cases remained unchanged. Additionally, the CAT™ score significantly increased [148].

Triple therapy

Research has demonstrated that increasing inhaled medicine to LABA in addition to LAMA together with ICS (triple treatment) improves outcomes reported by patients, pulmonary functioning, and decreases exacerbations when compared to LAMA. separately LABA+ICS and LABA+LAMA[149]. This can be done in several ways [150–160]. An RCT assessing the benefits of LABA+LAMA+ICS found that, despite smoking status, triple treatment enhanced clinical results over dual therapy. A post-hoc analysis supported this finding [161].

In patients with severe airflow obstruction due to COPD and a history of exacerbations, a recent analysis of three clinical trials showed a slight trend towards reduced mortality with triple inhaled therapy compared to non-ICS-based treatments. This suggests a potential benefit of triple therapy in terms of safety outcomes for this specific patient population [162].

Miscellaneous

Antibiotics

Preventive, continuous use of antibiotics did not influence the incidence of COPD exacerbations, according to five-year research examining chemoprophylaxis's efficacy throughout the winter [163-165]. Additional research has demonstrated that using several antibiotics consistently may lower the incidence of exacerbations [166, 167]. Those who were susceptible to exacerbations had a lower chance of experiencing exacerbations following a year of using azithromycin (250 mg/day 500 mg on three occasions per week) either erythromycin (250 mg twice a day) compared to conventional medication [168–170]. Azithromycin use has been connected to longer QTc intervals, a higher prevalence of bacterial resistance, and worse outcomes on hearing tests [170]. Less advantage among smokers who are currently smoking, according to a post-hoc study [171]. There is no proof that long-term azithromycin therapy is safe or helpful in avoiding COPD exacerbations, even after a year of treatment. For patients with recurrent exacerbations and chronic bronchitis, moxifloxacin pulse treatment (400 mg/day over five days once every eight weeks) did not reduce the overall exacerbation rate [172]. Exacerbations were not decreased by long-term doxycycline use, while there could be responder subgroups [173].

Mucolytic and antioxidant agents

Mucolytics like carbocysteine and N-acetylcysteine can be used consistently to help individuals with COPD feel slightly better and experience fewer exacerbations when ICS is not being given to them [174–177]. On the other hand, it has been demonstrated that erdosteine, independent of concomitant ICS therapy, may have a notable impact on (mild) exacerbations. The current data regarding the analyzed demographics, therapeutic dose, and concurrent treatment are too variable to identify the potential target demographic for antioxidant medications in COPD [178].

Put it all up, the most often prescribed medications for the treatment of COPD include inhaled corticosteroids in cases of severe COPD and recurrent exacerbations, long-acting bronchodilators, and selective β2-adrenergic agonists. Bronchodilators benefit patients with moderate to severe COPD, especially those with a long half-life, as they increase exercise tolerance, enhance general health, and reduce exacerbations. Nonetheless, due to potential side effects, inhaled corticosteroids need to be used with caution. Future COPD care seems bright because of ongoing developments in pharmaceutical therapy, which include the creation of novel medication and combination therapies.

Non-pharmacological therapy

Self-management

A conceptual definition of COPD self-management interventions was developed through the Delphi process. It states that these interventions are structured, personalized, and frequently involve multiple components. With the help of these interventions, patients should be able to modify their health-related behaviors for the better and acquire the skills they need to maintain their condition. Patients and healthcare professionals must have ongoing, continuous discussions to provide efficient self-care treatments. Behavior modification strategies evoke motivation, competence, and confidence in patients. Comprehensibility is improved by the employment of literacy-sensitive techniques [179]. It is well-established that self-management enhances the quality of life of individuals with COPD. A 2022 Cochrane review discovered that these interventions enhanced health-related quality of life, reduced hospital admissions for respiratory-related reasons, and had no effect on mortality risks [180]. Past Cochrane reviews and meta-analyses have addressed concerns of elevated mortality, indicating no effect on total mortality. The COMET and PIC-COPD, two separate trials, have demonstrated the possibility of lowering mortality with integrated case management and self-management strategies. Confirming the idea that self-management therapies are unlikely to be harmful are these findings from the most current Cochrane study [181, 182].

According to research, throughout six months, hospitalizations and emergency room visits doubled for individuals who participated in a three-month program designed to help them manage their COPD exacerbations on their own. This shows that self-management techniques could encourage people to use healthcare services more frequently [183]. Generalizing these findings, however, is difficult because of the variety of treatments, application consistency, intervention details, patient groups, duration of follow-up, and outcome measures. A conceptual definition should address these shortcomings, emphasizing the need for iterative patient-provider interactions [184]. The Chronic Respiratory Disease Questionnaire mastery scores of individuals receiving health coaching from respiratory therapists or nurses have shown significant gains in their ability to control their health [185].

Integrated care programs

Because COPD is complicated, several healthcare professionals must work closely together. There is conflicting data about the potential benefits and efficacy of a formal, planned disease management program. Integrated disease care improved quality of life, ability to exercise, hospitalizations, especially inpatient days, but not death, according to a study of 52 studies [186]. This was not supported by a significant multicentre trial conducted in primary care within a well-functioning system, and telemedicine treatments did not yield noteworthy results [187]. Though structured into a codified program, well-organized care may not always be advantageous. A person's integrated care should be tailored to their health literacy and stage of sickness [188, 189].

Physical activity

Both community-based and home-based pulmonary rehabilitation have shown benefits, but encouraging and sustaining physical exercise is essential [190]. A common feature of COPD patients' reduced exercise levels is their diminished quality of living, which raises their chances of hospitalization and mortality [191–193]. Consequently, behavior-targeted therapies to increase physical activity are gaining popularity [194]. Especially for those with poor baseline self-efficacy in COPD, technology-based therapies can improve exercise self-efficacy and encourage healthy lifestyle modifications [195, 196]. Most published research lacks instructions, methodological consistency, and specifics needed to duplicate or modify treatments for use in clinical settings. Research on the effects of community-based physical activity coaching on COPD exacerbation history found no advantages in terms of acute care utilization or survival [197]. Around 12 to 15 mo after the intervention, different research discovered a correlation between it and a lower incidence of acute exacerbations [198]. Studies have demonstrated that non-pharmacological therapies, such as pursed lips and breathing with the diaphragm, enhance exercise tolerance and lung function in people with COPD [199].

Exercise education

Individuals diagnosed with COPD experienced a significant boost in their physical activity levels through exercise training alone or when combined with activity counseling, as revealed by a meta-analysis of RCTs [200]. Strength training yields improved results when paired with intermittent or continuous load training [201]. The recommended limit for resistance workouts is Borg dyspnea, and the tiredness rating is 4 to 6 (average to intense), or 60–80% of an individual's symptom-limited maximal work or heart rate [202, 203]. Exercise regimens that alternate between periods and continuously work well for endurance training. In the latter, the patient completes the same amount of work but breaks it into shorter bursts of intense activity. This tactic is helpful when other comorbidities hinder performance [204, 205]. Exercise ability in COPD patients has been demonstrated to increase with Tai Chi practice, which emphasizes focus and circular body movement. However, Tai Chi's benefits in lowering dyspnea and enhancing quality of life are still up for debate [206]. Since they lessen both resting and dynamic hyperinflation, optimizing bronchodilators can improve exercise training [207]. Although it is helpful for aerobic training, strength training has no positive effects on health or exercise tolerance [208]. Exercise training on the upper extremities improves arm strength and endurance, whereas whole-body vibration training may increase endurance [209, 210]. Exercise that strengthens the inspiratory muscles may help with performance, lessen dyspnea, or promote overall health, although these benefits are not always guaranteed [211–214].

Therapeutic management of COPD acute exacerbation

Acute exacerbations, which can occur at any moment during COPD, are sporadic bouts of worsening pulmonary function and increased respiratory symptoms that call for a change in routine therapy [38, 39, 53–57].

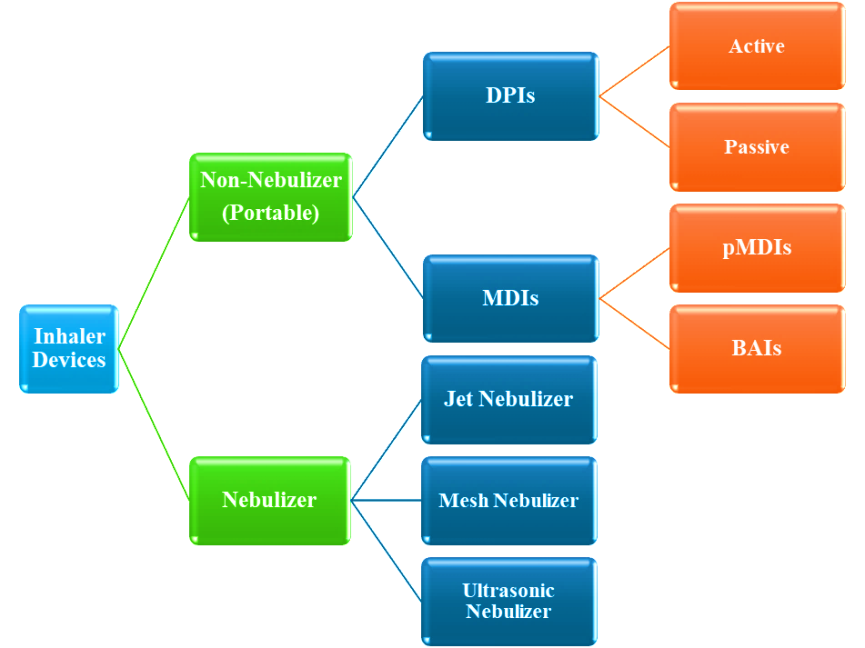

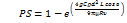

Fig. 9: Types of inhalers used in the treatment of COPD [53, 58]

DPIs

Orally inhalable DPI formulations provide patients with higher compliance, high dose-carrying capacity, and drug stability. Targeting respiratory diseases such as diabetes and pain management, these devices release metered doses of powdered drugs by inhalation. DPIs have been developed to treat both local and systemic abnormal lung diseases, including “asthma” and “chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.” The device, commonly made of polypropylene plastic, delivers the dry powder formulation to the pulmonary tract in a controlled manner.

The dry powder size is critical for inhalations. Since it is typically stored in capsules, the aerodynamic diameter range is 1–5 µm. Less than 2 µm is needed for systemic effects, whereas 2–5 µm is the preferred particle size. Dry powders that can become aerosolized are made by adjusting their shape, density, and porosity. DPIs frequently develop through crystallization and micronization, but both methods have drawbacks regarding particle size, shape, dispersion, and crystallinity. To generate respirable particles, spray drying is employed along with specialized milling procedures to manage humidity during crystallization. For effective delivery of drugs, the pharmaceutical industry must manufacture micron-sized powders on a large scale [215].

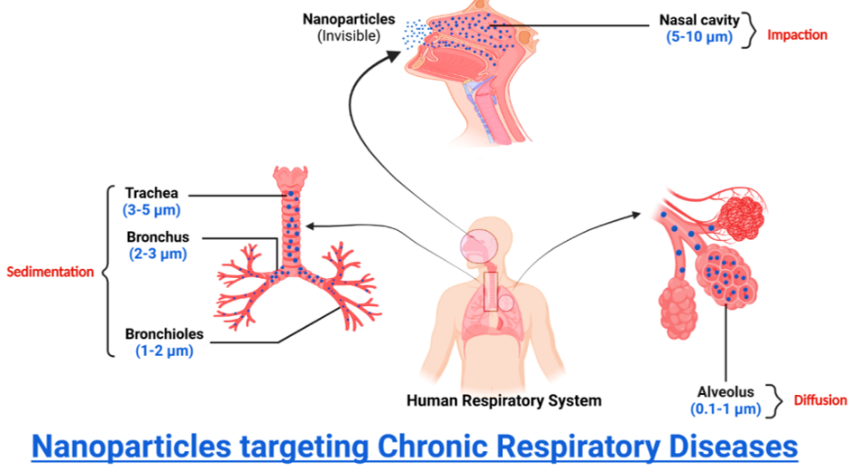

Drug deposition and particle size in the lungs

Precautionary measures should be implemented since drug deposition in the lungs can impact how effective an inhalation therapy is therapeutically. The initial stage following the particles' successful inhalation is drug deposition, which can be achieved by various methods, including direct interception, electrostatic deposition, sedimentation, and diffusion (table 2), and impaction, sedimentation, and diffusion.

Fig. 10: Mechanisms of particle deposition based on size (BioRender.com)

Table 2: Pathways for particle-size-dependent deposition in the lungs

| Mechanism | Size of particles | Sections of the respiratory tract | Reference (S) |

| Impaction | 5-10 µm | Nasal Cavity(Oropharynx and conducting airways) | [59–61, 216] |

| Sedimentation | 3–5 µm | Trachea | |

| 2-3 µm | Bronchus | ||

| 1-2 µm | Bronchioles | ||

| Diffusion | 0.1-1 µm | Alveolus |

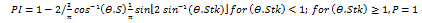

Owing to increased air velocity with turbulent flow, inertial impaction is the primary mechanism for deposition in the oropharynx and conducting airways. Large particles, defined as those with a diameter of more than 5 µm, are pushed out of their original airstream trajectory and eventually strike the upper airway wall because of inertia, which prevents them from reacting to abrupt changes in direction and speed. One may compute the probability (PI) of a particle departing from the airstream using Equation (1) [59–61, 216].

------------ (Equation 1)

------------ (Equation 1)

Equation (1) indicates that PI = probability of impaction

θ = bending angle (change in the direction of the flow)

Stk = Stokes number, defined as (Equation 2):

-------------- (Equation 2)

-------------- (Equation 2)

Equation (2) indicates that: ρ = particle density

d = particle diameter

υ = particle velocity

µ = viscosity of fluid

D = airway diameter

The principal difficulty of lung deposition with the dry powder inhaler is the quantity of medication lost because of this mechanism [217].

Sedimentation is the process that impacts particles between 0.1 and 5 µm as they enter the lungs, mainly within the bronchi, bronchioles, as well as alveolar area. The probability of impaction-induced deposition also decreases with velocity. Therefore, sedimentation impacts particles that have made it beyond impaction and into the final five or six lung generations. Gravity causes the particles to start settling, which causes sedimentation. Sedimentation worsens as the particle mass, diameter, residence time, and flow rate rise. When particles with a diameter of 3-5 µm enter the tracheobronchial area, they do so via sedimentation; however, when particles with a diameter of 0.1-3 µm enter the alveolar region, both sedimentation and diffusion are anticipated. Equation (3) expresses the chance that sedimentation (PS) will result in particle deposition [59–61].

---------------------- (Equation 3)

---------------------- (Equation 3)

Equation (3) indicates that PS = probability of sedimentation

g = gravitational force

C = Cunningham slip angle correction factor

ρ = particle density

d = particle diameter

L = length of the tube

ø = inclination angle relative to gravity

µ = viscosity of fluid

R = radius of the airways

υ = particle velocity

Different types of inhalers

Here listed below some of the traditionally used inhaled that are:

Breezhaler

Clickhaler

Diskhaler

Diskus

Ellipta

Handinhaler

Jenuair

pMDIs

Respimat

Swinghaler

Turbuhaler

Twincaps

Twisthaler

Rotahaler [218]

Space inhaler

Volumatic device [219]

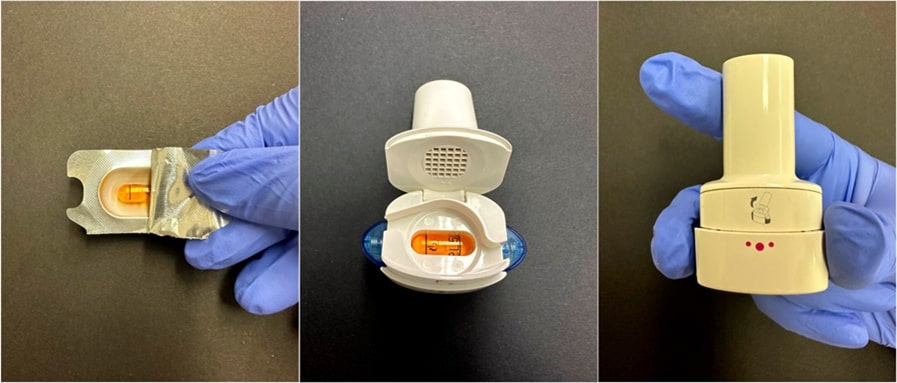

Fig. 11: Inhalation devices [218, 219]

Presently available inhalers and innovations in inhalation therapy

In recent years, there have been significant advancements and developments in inhalation administration to increase medication availability and distribution, daily regimens, and patient compliance (particularly by lowering the frequency of doses). This has led to advancements in device technology, medication delivery methods, and manufacturing procedures. Lipid-or polymer-based carriers in the formulation and biotech medications [220]. For example, Afrezza® is the only protein DPI (insulin) used to treat type 1 and 2 diabetes. As previously indicated, DPIs present a promising method for delivering biologics, including viruses (like phages), proteins, nucleic acids, and cells (attenuated bacterial cells like BCG for Tuberculosis). Regarding biologics for inhalation, proteins have gotten the most attention; nevertheless, many of the formulation and production processes have been altered to accommodate other biologics, such as nucleic acids and, more recently, phages. DPIs provide benefits such as mucosal immunization and non-invasive injection-free delivery, making them a viable platform for inhaled gene treatments and vaccines [221, 222].

Various DPIs are presently available on the market, and inhalation treatment is constantly evolving to overcome the many obstacles it encounters while maintaining a high level of therapeutic efficacy (fig. 12). Around 500 million people worldwide suffer from various diseases, and out of the 40 varieties of inhaler devices now on the market, DPIs are the most often used variety [223, 224].

Furthermore, fig. 13 gives a detailed breakdown of how to utilize a DPI device step-by-step for a more thorough perspective.

Furthermore, inhalation devices that are more recent and sophisticated can deliver drug doses in the microgram and occasionally nanogram range rather than milligrams (table 2), which results in higher drug deposition. Compared to earlier inhalers, which showed ≤20% lung deposition,>50% lung deposition has been recorded [225, 226]. Relenza® (zanamivir, 5 mg), Tobi Podhaler® (tobramycin, 28 mg), Bronchitol (40 mg, mannitol), and Osmohale® (mannitol) are a few DPIs with large dosages that should be noted [227, 228].

Fig. 12: Presently available inhalers [227]

Fig. 13: An explanation in detail on how to use the Breezhaler® DPI device: extraction of the capsules from the blister, insertion into the device through the closure, and pressing of the side buttons to puncture the capsule and release the powder [227]

For respiratory conditions like COPD and asthma to be effectively treated, prescription inhalers must be used as directed. Reduced medication delivery can affect disease control due to ineffective inhalation procedures or inaccurate administration strategies. Spacers, also called holding chamber extension devices, limit inhaled medication, increasing the effectiveness of pMDIs. A spacer can improve medication delivery when used with appropriate breathing techniques. 82.3 % of patients in Indian research reported misusing their inhalers at least once, with MDI users accounting for the most significant percentage of mistakes (94.3%). However, the proportion of errors was reduced (78%) when a spacer was used with MDIs. DPI users made 82.3% of the errors, followed by nebulizer users with 70% [229]. As a result, employing a spacer lessens both the amount of deposition in the oropharyngeal area and the requirement for exact actuation and inhalation synchronization that comes with utilizing a pMDI device alone [230]. Patients who need medical aid, such as elderly patients with COPD and cognitive impairment, or babies and youngsters who might not be able to perform a precise breathing technique or who might not comply, will benefit most from this. Conversely, DPIs don't require a spacer or must be shaken before each usage.

Integrating data analysis and connection in digital smart inhalers transforms respiratory treatment by tracking patient adherence and inhaler usage. These technologies maximize treatment outcomes by enabling patients to control their diseases properly [231]. They are invaluable for people who suffer from obstructive disorders or respiratory conditions like asthma. Personalized treatment regimens are made possible by the inhalers' use of electromechanical sensors and microelectronics to monitor inhaler activation. This is the first line of smart inhalers with embedded sensors, allowing for efficient respiratory condition management [232, 233].

Van Sickle et al.'s study, which provided real-time monitoring and patient adherence insights, validated the effectiveness of digital smart inhalers in redefining respiratory treatment. Utilizing the mobile health service improved asthma outcomes, such as more asthma-free days, greater medication adherence, and better overall asthma management [234].

With the implementation of smart DPIs and related applications, patient involvement and engagement will increase. A more patient-centered healthcare system will result from its successful implementation, assisting individuals in managing their health. Complex business structures and a lack of interoperability standardization are the main obstacles that still need to be addressed [235].

The clinical translation of NPs and inhalation devices entails numerous challenges that must be systematically addressed to optimize patient outcomes. A prominent issue within this context is patient adherence; many individuals encounter significant obstacles in consistently and correctly utilizing their inhalers as prescribed. The factors contributing to non-compliance include a lack of understanding of proper inhalation techniques, physical difficulties associated with device handling, and psychological barriers to managing chronic respiratory conditions [236, 237].

To enhance adherence, it is imperative to implement a comprehensive strategy that incorporates education, technology, and personalized support. Educational initiatives should provide thorough instruction on the correct usage of inhalers, employing visual aids and practical demonstrations to reinforce comprehension [237]. Furthermore, inhalation devices should be designed to focus on user-friendliness, incorporating features such as ergonomic designs, audible feedback mechanisms, and quickly interpretable dosage indicators.

Additionally, establishing ongoing support from healthcare professionals is critical to motivating patients. Regular follow-ups, facilitated through phone communication, text reminders, or specialized mobile applications, can significantly improve adherence by ensuring patients remain cognizant of their medication schedules [231]. Integrating such technological tools provides timely reminders and enables tracking usage patterns, allowing healthcare providers to identify and address potential issues proactively. The likelihood of improved adherence and overall therapeutic success is considerably increased by cultivating a supportive environment and empowering patients in their respiratory health management [238].

Comparative analysis of inhaler types

DPI, pMDI smart inhalers

DPIs

A wide array of DPIs is currently available. To be classified as ‘ideal,’ an inhaler device must encompass several essential criteria: (1) effectiveness ensuring the inhalation of a sufficient fraction of the drug, delivered in breathable-sized particles, regardless of fluctuations in the patient’s inspiratory flow; (2) reproducibility-facilitating the inhalation of a consistent amount of the drug, particularly concerning its breathable fraction; (3) precision allowing for real-time knowledge of the number of doses remaining in the device and confirming the correct execution of inhalation; (4) stability protecting the drug(s) from adverse effects due to variations in temperature and humidity; (5) comfort promoting ease of use across diverse situations, while accommodating multiple doses for long-term application; (6) versatility enabling the administration of various medications; and (7) environmental sustainability ensuring the absence of harmful chemical contaminants. At present, no commercially available DPI fulfills all these criteria. Nevertheless, specific inhaler devices possess features that closely align with the ideal conception of an inhaler in a practical, real-world context [239–241].

pMDIs

A pMDI uses a propellant to deliver a specific dose of medication directly into the lungs. It works well with spacers, which help improve drug delivery and make inhalation easier for patients with coordination issues. pMDIs are small and light, making them convenient for patients who need to take their medications while on the move [242]. Each inhaler can provide multiple doses from a single canister, making it a cost-effective choice for long-term treatment. pMDIs can deliver various medications, including bronchodilators and corticosteroids, allowing healthcare providers to tailor treatments to each patient. Using a pMDI effectively requires good timing between pressing the inhaler and breathing in. This can be difficult for some patients, such as the elderly or young children. The propellants in pMDIs can increase the carbon footprint compared to other inhalation devices, raising concerns about their environmental effects [242, 243].

Smart inhaler

Smart inhalers significantly advance in managing respiratory diseases such as asthma and COPD. These innovative devices are embedded with advanced sensors that meticulously monitor various factors, including medication usage, therapeutic effectiveness, and environmental triggers that could exacerbate symptoms [244]. The comprehensive data collected is transmitted to patients and healthcare providers through user-friendly mobile applications, facilitating effective medication tracking and personalized coaching tailored to individual needs. In addition to these features, smart inhalers send timely reminders to users and provide constructive feedback on inhaler techniques, which is crucial in improving patient medication adherence [245]. Despite these benefits, the higher price point of smart inhalers may pose a barrier to access for some patients, highlighting the need for further large-scale studies to confirm their overall effectiveness and justify their costs. Moreover, while some devices may experience technical malfunctions, user support often resolves these issues. Ongoing research is also critical to address outstanding questions regarding funding strategies and implementing these advanced technologies in diverse healthcare settings [244].

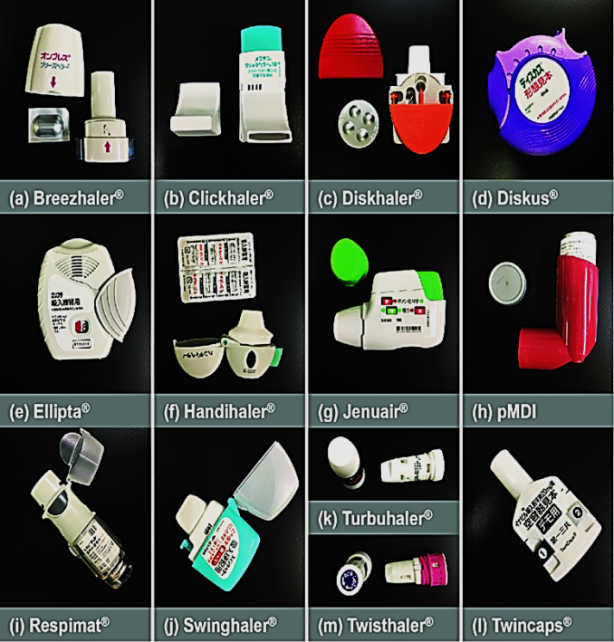

Nano-scale system

A new field of multidisciplinary science called nanoscience has emerged [246]. The field of nanomedicine has gained potential for scientific study due to the introduction of nanotechnology throughout the last two decades [247]. As potential ideal drug delivery systems for poorly soluble, poorly retained, and labile substances, a late-stage advancement in nanoparticulate frameworks, including potent NPs, polymeric NPs, and polymeric self-congregations, is presented in the current matter. The improved solubility, targetability, and binding to tissues, among other new capabilities arising from nanosizing, are illustrated. Furthermore, these capabilities are used to develop an additional drug delivery system [248].

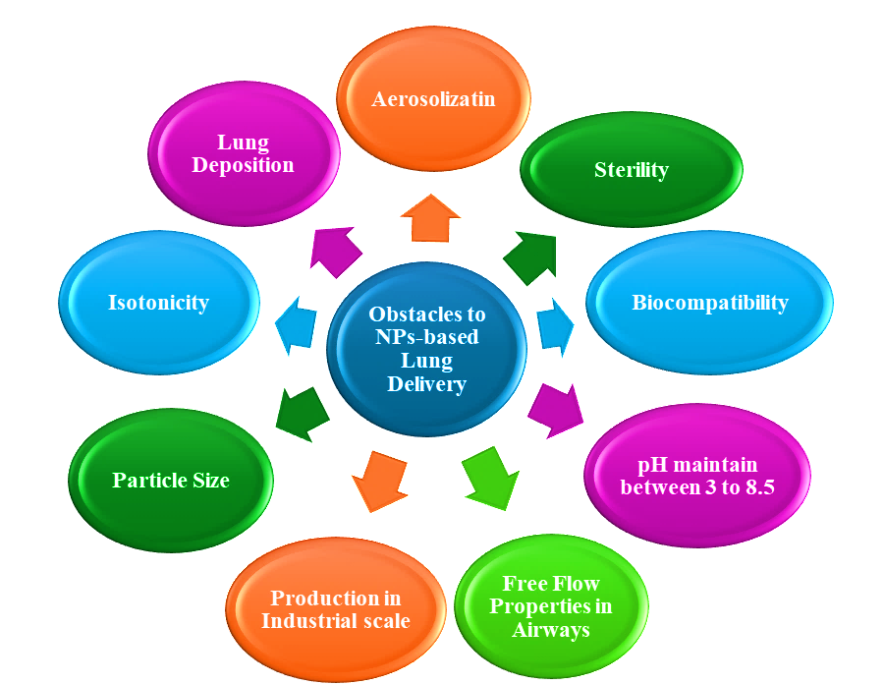

The ability to deliver the treatment over various natural obstacles to the target location is another distinctive feature of nano particulates, and difficulties with NPs formulations are mentioned, accordingly, in fig. 14 and 15.

Nanomedicine formulations

The history of nano-scale development

Nanomedicine is a therapeutic application of technology that enhances the delivery of innovative therapy techniques for inflammatory lung diseases, such as COPD, in future generations [249]. In the past, medicinal plants were used to cure illnesses, but how the drugs were delivered lacked uniformity, control, and precision. In 1955, Jatzkewitz published the first study on polymer-drug conjugate (NP-based) treatment, demonstrating the first instance of medicine and nanotechnology working together to improve medication delivery and effectiveness. Similarly, the identification of liposomes in the 1960s stimulated research on nanocarriers, which stimulated the development of micelles and polymerization drug-loading techniques in the latter part of the 1970s and early 1980s [250, 251]. Over 1000 research publications on nanomedicine, including using NPs and nanocarriers in practical biological contexts, were reported to have been published in Web of Science in 2015. This indicates an exponential growth in the number of publications on this topic of study. This expanding field of study has led to the advancement of conventional medicine delivery through the micro-engineering of NPs, which has been used to treat various chronic inflammation lung conditions [251].

Fig. 14: Relevance of nano-scale system in pulmonary applications (BioRender.com)

Fig. 15: Obstacles to NPs-based lung delivery (BioRender.com)

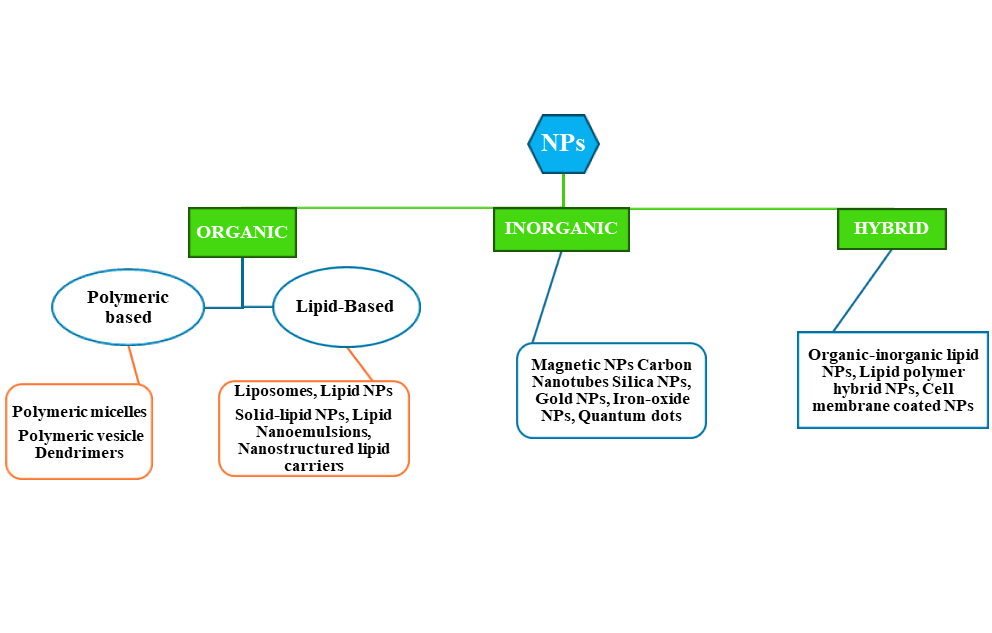

Fig. 16: Several kinds of NPs. The NPs have three different nanoparticle subclasses: A) Organic, B) Inorganic, and C) Hybrid; again, their subgroups are divided into different varieties of NPs(BioRender.com)

Nanomedicine delivery system

As previously stated, present therapy techniques focus on symptomatic alleviation rather than treating the underlying cause of COPD, which is the harm caused by cigarette smoke [252]. This makes it necessary to investigate other treatment options, such as nanoparticle delivery methods. NPs-based formulations encapsulate the drugs, transport them to the desired location, and release their active compounds into the targeted tissues. Among the numerous advantages of this technology-dispersing procedure is the real-time, regulated release of the medicine of choice to the therapeutic target [62]. The Nano formulations contain API and certain other supporting carriers that aid in the dispersion and transportation of Nano formulations with volume, making up for the delivery of drugs throughout the body. The different drug distribution in various routes of administration will also affect other aspects such as pharmacokinetics, ease of administration, toxicity, and infection risk [62].

When it comes to treating severe RDs, nanomedicine has demonstrated enormous therapeutic promise. Examples include polymeric NPs, liposomes, nanotubes, inorganic silver and gold NPs, and micelles. NPs have been used to transport immunomodulatory chemicals, DNA vectors, antibiotics, and vaccine components to their intended target areas. In addition, NPs are preferred because they enable tissue-specific drug delivery and have the capacity to maintain and preserve the medication. As a result, this has improved efficacy over alternative therapy methods and less negative consequences for the patient. Moreover, physical attributes such as size, shape, zeta potential, oxidative potential, and chemical structure can be adjusted to fine-tune a nanoparticle's biological response [253]. A concise overview of the several innovative nanoparticulate systems is shown in fig. 16.

Several kinds of NPs

Organic

Polymer-based

Polymers are macromolecules that consist of repeating units of monomers. Various synthetic groups of polymers have been employed to functionalize and medicate polymer-based NPs. Any polymer NP can be called "polymer-based NPs" but is associated explicitly with nanospheres and nano-capsules. Several materials are available for collecting NPs, including synthetic and characteristic polymers. Regular polymers, including proteins and polysaccharides, are remarkably biocompatible and biodegradable. Different benefits are available from other perspectives when using engineered polymers. Because polyethylene glycol polymers are very bio-inert, for instance, they are frequently utilized for altering the surface of NPs [254]. Using polymeric NPs for medicine delivery aims to maximize beneficial effects while minimizing detrimental ones. This reduces PEGylation and enhances NPs' susceptibility to resistant cells [254, 255]. Because PEG-covered NPs are much-dormant, they are also prepared to enter the respiratory fluid. PEG-covered particles swiftly pierced body fluid at 100 and 200 nm [256]. Due to its electrostatic tendency, polyethyleneimine, a cationic polymer, was employed as an efficient linker to nucleotides in the interim. Because of this characteristic, PEI-based NPs have emerged as a promising option for high-quality transportation for chronic respiratory diseases [255, 256]. Here are some polymer-based NPs enlisted below:

PMs

PMs are nanoscale polymeric capsules whose membranes are often believed to have a hydrophobic bilayer structure like phospholipids [257]. PMs constitute a micelle, even though amphiphilic molecules produced in solution contain macromolecules. "Organized self-assembled bodies formed in liquid and consisting of amphiphilic macromolecules, generally amphiphilic and amphiphilic blocks built of hydrophilic and hydrophobic blocks, di-block or tri-block copolymer," is how the IUPAC defines polymer micelles. Typically, PMs are spherical. PMs are different from typical micelles in the following ways. 1) Greater volume, often with a 10–100 nm diameter. 2) Lower CMC while keeping different macromolecules in balance. 3) The kinetic as well as thermodynamic stability of PMs is better [258]. Furthermore, due to their biological stability and the diversity of polymers found in PMs, it is frequently easier to create the hydrophilic and hydrophobic blocks of PMs. Polyethylene glycol, polyvinyl alcohol, poly-N-vinyl-2-pyrrolidone, poly-acrylic acid, polyacrylamide, polyglycerol, poly amino acids, and polysaccharides are among the substances that provide the hydrophilic shells. The hydrophobic blocks may usually be made from polyesters (like polyglycolic acid, polycaprolactone, and poly-D, L-lactic acid) or polyether (like polyethylene oxide and polypropylene oxide) [259].

Dendrimers

Dendrimers are artificial branching polymeric macromolecules ranging from 10 to 100 nm. They have an outer functional unit layer, an internal recurring unit layer, and a core that allows them to be polyfunctional [260, 261]. In the process of forming, dendrimers go through chemical synthesis by polymerization. Due to the spherical shape and highly adjustable surface of dendrimers, the nanocarrier is more biocompatible and degrades more readily [260, 262].

In one research, Khan et al. used a lipid replacement to encase siRNA in poly(amidoamine) (PAMAM) and poly(propylene imine) dendrimers to treat inflammatory lung disorders such as asthma and COPD. Tie-2 endothelial cells developed in the lung thanks to the combinational method's synergistic impact on the tyrosine-protein kinase receptor. The outcomes demonstrated the significant differences between PAMAM-conjugated dendrimers with C15 cholesterol tails and polyphenylene ethynylene dendrimers containing C15 and C14 cholesterol chains. Moreover, the results obtained in vivo showed that neither the toxicity nor the dendrimer-lipid compounds led to an elevation in proinflammatory cytokines in the mice [262, 263].

Lipid-based

Liposomes

The spherical, nanoscale vesicles known as liposomes have a variety of uses due to their concentric structure, which allows them to combine hydrophilic and hydrophobic drugs in a watery core and hydrophobic phospholipid carbon chains individually. The liposomes' external appearance resembles layers of biological material [264–266]. One of the beneficial characteristics of liposomal arrangements is that they use nontoxic lipids, which are easily absorbed by the body and don't constitute a health risk.