Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 3, 2025, 55-79Review Article

REVOLUTIONIZING ALZHEIMER’S THERAPEUTICS: FROM MICROTECHNOLOGIES TO AI-DRIVEN INNOVATIONS

AKANKSHA LAHIRI1, BALAMURALIDHARA V.2*, MANOHAR S. K.1, AKHILA A. R.3

1Department of Pharmaceutics, JSS College of Pharmacy, Mysuru, JSS Academy of Higher Education Research, Mysuru-570015, Karnataka, India. 2,3Department of Pharmaceutics, JSS College of Pharmacy, JSS Academy of Higher Education Research, Mysuru-570015, Karnataka, India

*Corresponding author: Balamuralidhara V.; *Email: baligowda@jssuni.edu.in

Received: 16 Jan 2025, Revised and Accepted: 13 Mar 2025

ABSTRACT

This review article dives deep into Alzheimer's Disease (AD), a progressive and incurable brain disorder. It aims to equip readers with a comprehensive understanding of AD by exploring its history, classification, causes, and risk factors. The article explores the emerging field of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and its potential to revolutionize AD management. It examines how AI can impact diagnostics, treatment strategies, and, particularly, the development of targeted therapies. AI-powered imaging tools, such as Deep Learning-based Positron Emission Tomography (PET)/Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) analysis, have achieved over 90% accuracy in early AD detection by identifying subtle brain changes years before clinical symptoms appear. Machine learning models have also enhanced precision medicine by predicting patient responses to therapies with 85–92% accuracy, optimizing treatment regimens based on genetic and biomarker profiles. These novel delivery systems enhance drug efficacy, improve patient compliance, and reduce systemic toxicity, addressing key challenges in AD treatment. Future developments will focus on AI-guided personalized medicine, smart nanocarriers responsive to AD biomarkers, and AI-powered neuroprosthetics for cognitive rehabilitation. Next, it compares established management methods with the latest investigational drug therapies for AD. This analysis sheds light on promising future directions and potential breakthroughs in AD treatment. However, the article emphasizes the importance of patient safety and highlights the rigorous processes of clinical trials, and regulatory hurdles that new AD therapies and delivery systems must overcome. The review concludes by summarizing the key takeaways and identifying the most promising avenues for future research and development in AD treatment. It emphasizes the potential of these cutting-edge approaches to transform AD care and significantly improve patient quality of life.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, Artificial intelligence, Drug delivery, Clinical trials, Regulatory guidelines

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i3.53726 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer's disease (AD) was initially considered an advanced neurodegenerative condition by Alois Alzheimer in 1906. It stands as the predominant cause of dementia, marked by the gradual decline of nerve cells, brain functions, and cognitive abilities [2]. Globally, Alzheimer's constitutes 60–80% of all dementia cases [1, 2]. Presently, the FDA has approved six prescription medications for AD. However, none of these drugs has demonstrated the ability to cure the disease or arrest its progression; they can only provide temporary relief from its symptoms [3, 4]. Managing individuals with AD poses challenges for both healthcare professionals and caregivers [5-7]. Additionally, ensuring patient compliance and persistence with treatment is vital for effectively slowing down the disease's progression and maintaining acceptable well-being [8–10]. Without improvements in AD treatment, it is projected that there could be 13.8 million individuals aged over 65 with the condition in the United States by 2050 [11]. The blood-brain barrier (BBB), characterized by its unique biochemical, structural, and physiological features, serves as the initial interface between the cerebrospinal nervous system (CNS) and the variable environment of the bloodstream [12]. Enzyme activity and efflux pumps actively limit the entry of lipid-soluble molecules and prevent water-soluble blood molecules from accessing the central nervous system (CNS) [13]. The intricacies of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) contribute to the central nervous system (CNS) being one of the body's most intricate microenvironments, posing challenges for developing new medications for CNS disorders. The utilization of Novel Drug Delivery Systems (NDDS) holds considerable promise for advancing the therapy of disorders in the cerebrospinal nervous system (CNS), presenting various advantages over traditional chemotherapy. These advantages include targeted drug delivery, protection against immune and circulatory system clearance, alteration of the medication's physicochemical properties, reduction in dosage, and controlled release of the medication [14–16]. This study outlines the delivery methods employed in the pharmacological management of Alzheimer's disease (AD).

For this review, we explored the papers across four major English databases: PubMed, Google Scholar, Elsevier, and Clinicaltrials. gov. The search focused on studies published within the last twenty years related to Alzheimer's Disease (AD) and the role of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in its diagnosis, treatment, and drug delivery. The primary keywords used in the search included "Alzheimer's Disease," "Artificial Intelligence in AD," "AI-based diagnostics," and "Targeted drug delivery in AD," Studies exploring AI-driven imaging techniques and novel drug delivery approaches were included. However, articles with incomplete data, abstracts without full-text availability, inconsistencies between methodology and results, and inadequate explanation of findings were excluded. By incorporating this search strategy in the introduction, the review ensures a systematic and transparent approach to analyzing the latest advancements in the AD management.

History of alzheimer's disease

Augustine D., the first patient to suffer from presenile dementia, was defined by Alois Alzheimer in 1907, which is how the condition, named for the German psychiatrist and neurologist, came to be [17]. The first autopsy-based description of an Alzheimer's disease (AD) brain was subsequently provided by Italian doctor Perusini, who was also an Alzheimer's student [18]. Among these were reports of anomalous fibrous inclusions in the miliary foci and perikaryal cytoplasm of neurons, which were subsequently identified as amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), respectively. .Glennerhypothesized in 1984 that chromosome 21 contained the amyloid gene, identifying "amyloid" (Aβ) as an element of the amyloid plaques observed in the brains of AD and Down syndrome patients [19, 20].

Following the identification of a locus on chromosome 21 by genetic linkage studies in 1987, the amyloid precursor protein (APP) gene was cloned [21, 22]. The identification of the first APP missense mutation in an AD family in 1991 [23] prompted Hardy and colleagues to assert that amyloid was the etiological factor behind AD [24, 25].

Alois Alzheimer first identified presenile dementia in 1907, later named Alzheimer’s disease (AD). His student, Perusini, provided the first autopsy-based description, noting amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs). These abnormal fibrous inclusions were observed in miliary foci and neuronal cytoplasm, later recognized as extracellular amyloid plaques and intracellular NFTs composed of hyperphosphorylated tau protein. In 1984, Glenner et al. linked amyloid-beta (Aβ) to chromosome 21, associating it with AD and Down syndrome. Genetic studies in 1987 led to the cloning of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) gene, and the first APP missense mutation in an AD family was discovered in 1991proposing that Aβ accumulation triggers AD progression, influencing therapeutic research and drug development. Hardy and colleagues then proposed the amyloid hypothesis, suggesting Aβ as the primary cause of AD.

Classification of alzheimer's disease

Alzheimer's disease is mainly classified based on the clinical symptoms. It ranges from mild to severe. They are mainly classified into three stages, namely the Preclinical stage, Prodromal stage, and Dementia stage which is described in fig. 1.

Preclinical stage

The term "preclinical Alzheimer's disease" (AD) describes the stage of cognitive deterioration that comes before a formal clinical diagnosis. The American Alzheimer's Association and the International Working Group (IWG) have initiated efforts to define the parameters of this preclinical stage of AD [27]. It is advisable to monitor persons at an elevated risk of developing AD, such as those with genetic predispositions (family history or APOE genotype), for preclinical symptoms. Alternatively, observing very subtle cognitive or behavioral changes in individuals over the age of 55 may prompt an investigation into preclinical AD. Ongoing research utilizing sensitive neuropsychological testing, neuroimaging, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers unveil abnormalities that can aid in diagnosing preclinical AD.

AI role in preclinical stage

AI-Enhanced neuroimaging analysis

Deep learning algorithms applied to MRI, PET, and Computed Tomography (CT) scans detect subtle brain atrophy and early amyloid/tau deposition, achieving over 90% accuracy in distinguishing preclinical AD from normal aging.

Example: AI models analysing fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) scans can predict AD progression up to six years before clinical symptoms appear.

Machine learning for biomarker prediction

AI integrates cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and blood biomarkers (e.g., Aβ42/40 ratio, phosphorylated tau) to predict AD risk with high sensitivity.

Example: Support Vector Machine (SVM) models improve the classification of preclinical AD by combining biomarker and genetic data.

Fig. 1: Stages of alzheimer’s disease [26]

Cognitive and speech pattern analysis

Natural Language Processing (NLP) tools detect early speech and linguistic changes, which often precede memory impairment.

Example: AI-driven speech assessment tools identify subtle hesitations and vocabulary changes linked to early AD stages.

Wearable and digital biomarker monitoring

AI-driven smartphone apps and wearable sensors track daily cognitive patterns, movement, and sleep disturbances, enabling continuous risk assessment.

Example: AI-powered digital cognitive tests assess reaction times and memory recall, detecting early cognitive decline years before clinical symptoms emerge.

Prodromal stage

During the prodromal stage of Alzheimer's disease (AD), there are evident signs of brain dysfunction. To identify AD as the primary underlying pathology at this stage, a clinician must ascertain that the individual meets the criteria for Mild Cognitive Impairement (MCI) while also determining that AD is the predominant cause [28]. Biomarker evidence indicating the progression of AD neuropathology provides the most accurate verification.

AI role in prodromal stage

AI-Enhanced neuroimaging analysis

Machine learning models applied to MRI, PET, and CT scans detect early hippocampal atrophy, cortical thinning, and amyloid/tau accumulation—key indicators of prodromal AD.

Example: AI models analyzing FDG-PET scans achieve 85–95% accuracy in differentiating MCI from healthy aging.

Deep learning algorithms predict the conversion of MCI to AD up to 3–5 y in advance, guiding early intervention.

Machine learning for biomarker integration

AI algorithms combine cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and blood biomarkers (e. g., Aβ42/40 ratio, phosphorylated tau, neurofilament light (NfL)) to improve diagnostic precision.

Example: AI-based predictive models using plasma biomarkers can classify prodromal AD with over 85% sensitivity and specificity.

Natural language processing (NLP) for speech and cognitive analysis

AI-driven NLP tools analyze spoken language, sentence complexity, word-finding difficulty, and speech pauses-early linguistic markers of AD.

Example: AI speech analysis can predict MCI conversion to AD with 80–90% accuracy, offering a non-invasive diagnostic approach.

AI-Powered cognitive and behavioral monitoring

Digital cognitive tests and wearable sensors track reaction time, memory lapses, and sleep patterns, detecting early cognitive and behavioral changes.

Example: AI-integrated smartphone apps and wearables monitor daily activity and subtle cognitive fluctuations, aiding real-time risk assessment.

Dementia stage

Dementia, characterized by a substantial impact on a person's occupational and social performance, leads to a loss of independence in performing daily activities due to cognitive impairments [29]. In such instances, individuals require assistance from others to accomplish tasks. Memory impairment, along with deficits in other cognitive domains like executive, language, and visuospatial abilities, are common symptoms observed in Alzheimer's disease dementia.

AI role in dementia stage

While early detection at this stage may not prevent disease progression, AI-powered tools play a crucial role in accurate diagnosis, disease staging, treatment optimization, and personalized care planning.

More accurate diagnosis and disease staging: AI differentiates AD dementia from other neurodegenerative disorders, preventing misdiagnosis.

Personalized treatment and care planning: AI tailors medication regimens, behavioral therapy, and caregiver support based on disease severity.

Improved clinical trials and drug development: AI helps enroll patients in late-stage AD trials, evaluating symptom management therapies.

Enhanced caregiver support and remote monitoring: AI-powered digital tools assist caregivers, tracking daily activities and predicting behavioral changes.

The fig. 2 illustrates the pathophysiology of Alzheimer's disease and the role of AI in its diagnosis. The disease begins with the abnormal cleavage of amyloid precursor protein (APP) by the γ-secretase complex, leading to increased production of amyloid-beta (Aβ) peptides due to mutations on chromosome 21. These peptides aggregate into insoluble amyloid plaques, causing neuronal dysfunction, synaptic loss, and neurodegeneration, ultimately resulting in Alzheimer's disease. AI aids in early detection by analyzing brain imaging data through segmentation, feature extraction, and pattern recognition. Machine learning models identify biomarkers such as cortical atrophy and amyloid accumulation, enabling accurate disease diagnosis. By integrating AI with brain imaging, clinicians can detect Alzheimer's disease at an early stage, improving diagnosis and patient outcomes.

As with many other neurodegeneration-related disorders, the production and accumulation of misfolded proteins is the most notable histopathological feature of Alzheimer's disease. Individuals with Alzheimer's disease are more likely to exhibit extracellular amyloid plaques and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles in their brains [31, 32]. Transgenic mice expressing at least one of the human mutant genes have also demonstrated the characteristic amyloid pathology observed in the brains of individuals with Alzheimer's disease [33, 34]. The ϒ-secretase complex, composed of PS1, PS2, and other proteins [35], plays a pivotal role in the amyloidogenic process by acting on the β-secretase sub-products [41, 36-37]. The aggregation propensity of Aβ peptides, with Aβ1-42 exhibiting a higher tendency, is contingent upon the ϒ-secretase complex's action on the three distinct cleavage sites originating from Aβ1-38, Aβ1-40, and Aβ1-42 [36].

Fig. 2: Pathophysiology and role of AI in diagnosis of alzheimer’s disease [30]

This encourages these harmful peptides to build up in the brain [38–40]. Even though amyloidogenesis is the main cause of neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's disease (AD), it is also accompanied by changes in other processes, most notably the brain's inflammatory profile [41–43]. It is thought that inflammation influences both brain pathology and behavior early in the disease course, although the precise implications of the many cellular and molecular components of the inflammatory profile in AD are still not fully known.

AI enhances the understanding of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) mechanisms by identifying novel biomarkers, predicting protein misfolding patterns, and mapping disease progression.

Biomarker Discovery – AI integrates multi-omics data (genomics, proteomics, metabolomics) to identify blood-based and CSF biomarkers (Aβ42/40, p-tau, NfL) for early detection.

Protein Misfolding Prediction – AI tools like AlphaFold predict Aβ and tau misfolding structures, while deep learning models simulate protein aggregation dynamics to identify anti-aggregation drug targets.

Disease Progression Modeling – AI analyzes longitudinal imaging, biomarker, and clinical data to predict MCI-to-AD conversion and genetic risk factors (e.g., APOE4, TREM2), refining precision medicine approaches.

AI-driven insights accelerate early diagnosis, therapeutic development, and personalized treatment strategies, transforming AD research and care.

Pathology

As Alzheimer's disease is polygenic and very complicated, its pathology is not yet fully understood [44–45]. Following are some significant neuropathological indicators that Alzheimer's disease was present:

In Alzheimer's disease, the hyperphosphorylation of tau proteins leads to the formation of neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), which are chiefly distinguished by the gradual deposition of amyloid-β (Aβ) proteins surrounding the neurons composing them [47] (fig. 3).

Key barriers in crossing the BBB

Tight junctions – Endothelial cells form a highly selective barrier, restricting the entry of large and hydrophilic molecules.

Efflux transporters (e. g., P-glycoprotein) – Actively pump drugs out of the brain, reducing therapeutic effectiveness.

Enzymatic degradation – Brain endothelial cells contain enzymes that break down drugs before reaching their target.

Limited transport mechanisms – Only small, lipophilic molecules can passively diffuse, while most AD therapeutics require active transport.

Emerging technologies addressing BBB challenges

Nanocarrier systems (Liposomes, polymeric and solid lipid nanoparticles) – Improve BBB penetration through surface modifications with ligands (e. g., transferrin, lactoferrin) that utilize receptor-mediated transport.

Exosome-based drug delivery – Exploits the brain’s natural extracellular vesicle transport, ensuring efficient and biocompatible drug delivery.

Focused ultrasound (FUS) with microbubbles – Temporarily disrupts the BBB to enhance drug permeability by 3–5×, improving therapeutic reach.

Peptide and antibody-conjugated drug delivery – Targets endogenous receptor-mediated transcytosis (e. g., insulin receptors) to shuttle drugs into the brain.

AI-Driven drug optimization – Uses machine learning models to predict BBB permeability and design optimized therapeutics with enhanced brain entry.

By combining nanotechnology, biologically inspired carriers, and AI-driven strategies, emerging innovations aim to overcome BBB challenges, enhance drug delivery, and improve treatment outcomes for AD patients.

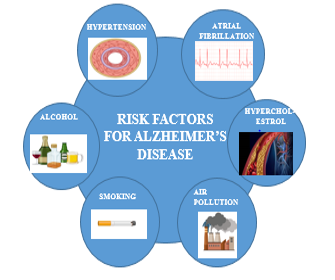

Risk factors

A multitude of genetic, environmental, and dietary risk factors, including but not limited to air pollution, alcohol consumption, atrial fibrillation, diabetes, hypertension, oxidative stress, hyper-cholesterolemia, and smoking, contribute to shaping the advancement of Alzheimer's disease as described in fig. 4.

Fig. 3: Schematic alzheimer’s pathologic condition [46]

Fig. 4: Risk factors connected to Alzheimer's disease [48]

Artificial intelligence (AI) approach in the diagnosis, management and treatment of the disease

AI has recently brought about a significant transformation in the assessment and utilization of digital data. In contemporary times, artificial intelligence finds application in various tasks, including speech or face recognition, often outperforming human capabilities in these areas [49]. The potential for quick, cost-effective, and precise automation, particularly in tasks like processing digital images using AI algorithms, presents an exciting opportunity for integration into medical treatment [50]. To enhance the understanding of complex multifactorial disorders like Alzheimer's disease (AD), numerous studies have been conducted. Leveraging the capabilities of deep learning (DL) and machine learning (ML), algorithms are developed that rely on the fusion and processing of diverse data sources. These sources include clinical data, neuroimaging, and neuropsychological information from cases and healthy subjects. In the field of biomedicine, AI is commonly utilized for computer-aided diagnosis (CAD), which seeks to automate the diagnosis process through data analysis, potentially aiding in the early detection of conditions such as AD or dementia with multiple etiologies.

In the realm of researching Alzheimer's disease (AD) and other disorders using AI-based tools, the necessity for large datasets is evident, comprising hundreds to thousands of entries for subjects, detailing a wide range of clinical and biological variables. These datasets serve as the foundation for developing innovative algorithms by scrutinizing disease characteristics. Within the field of neurodegenerative disorder investigation, particularly Alzheimer's disease, various open data-sharing projects have emerged. Examples include the Alzheimer's Disease Sequencing Project, the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, and the Global Alzheimer's Association Interactive Network (GAAIN) [51, 52].

2AI in the initial diagnosis of alzheimer's disease

AI technology, particularly Machine Learning (ML) algorithms, exhibits superior capabilities in managing high-dimensional complex systems compared to human abilities. ML has found application in the Computer-Aided Diagnosis (CAD) of various disorders, including Alzheimer's disease. This involves integrating information from cutting-edge equipment, such as wearable sensors for assessing executive functions, along with data from biological markers, brain imaging, electronic medical records, and neuropsychological testing. The comprehensive data about the structure and performance of the brain provided by Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and Positron Emission Tomography (PET) enables the identification of characteristics that support the diagnosis, including amyloid accumulation, atrophy, or microstructural damages [53-54]. Additionally, neuroimaging can distinguish between pathological conditions beyond Alzheimer's disease that might impact cognitive performance, such as brain tumors. Several studies have illustrated that complex diagnostic systems can incorporate neurodegenerative biomarkers, the primary pathology of Alzheimer's disease, or combinations of biomarkers [28, 29, 55, 56]. To date, the initial Computer-Aided Diagnosis (CAD) tools for Alzheimer's disease have been developed by employing AI algorithms to analyze brain scans [57-58]. Distinct anatomical differences between normal control (NC) and Alzheimer's disease (AD) groups, such as ventricle enlargement, cerebral cortex atrophy, and hippocampus shrinkage, were identified by analyzing MRI data from the OASIS database using the "eigenbrain" feature extraction and selection technique [59]. The employed Support Vector Machine (SVM) algorithm facilitated the creation of an automated classification method for AD diagnosis based on MRI data, achieving a mean accuracy of 92.36% [60]. Additionally, a Deep Learning (DL) algorithm for preclinical identification of Alzheimer's disease was developed using brain Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography (FD-PET), demonstrating 82% specificity and 100% sensitivity approximately 75.8 mo before the final diagnosis [61].

AI in the identification of the MCI subjects converted to AD

The more complicated task for AI is to differentiate between patients with stable Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) or MCI not caused by Alzheimer's disease (AD) and those with mild impairment who will eventually develop AD dementia. This proves challenging due to the unclear distinctions and overlapping symptoms in the biological variables characterizing these groups in the initial stages [62]. Algorithms designed to predict MCI-to-AD conversion categorize MCI patients into two groups: those expected to convert to AD (MCI-c) within a specific timeframe (typically 3 y) and those who will not convert (MCI-nc). Approximately 15% of MCI patients progress to AD each year [63-64], underscoring the importance of early and accurate identification to enhance outcomes and impede disease progression. Numerous AI-based algorithms evaluate the precision of combinations of non-invasive predictors, clinical data, and socio-demographic data to generate efficient screening tools. Utilizing the Alzheimer Disease Neuroimaging Initiative dataset, multiple supervised machine learning (ML) algorithms were trained on clinical scale ratings and neuropsychological test results, and an ensemble model was developed through their combination. This ensemble learning approach demonstrated the highest predictive ability for forecasting MCI-to-AD conversion [65], achieving an Area Under Curve (AUC) of 0.88. Notably, it relies solely on non-invasive and easily collectible predictors, in contrast to CSF biomarkers, improving its possibility for utilization and adoption in clinical practice.

AI in the precision of medicine for Alzheimer's disease

Clinically, individuals with Alzheimer's disease (AD) can exhibit variations in several aspects, including the rate of disease progression and responsiveness to medication, resulting in a heterogeneous pathology. Consequently, one of the significant challenges for AI is the integration of information to recognize subgroups of persons with similar characteristics. Utilizing clinical symptoms, the Mini-Mental State Examination, CSF biomarker levels, and inflammatory indices, it is possible to identify individuals with fragile Alzheimer's disease who typically do not respond well to pharmaceutical therapy and experience rapid deterioration [66]. This aids in advancing the development of novel targets for personalized therapeutic approaches. Furthermore, the integration of omics data provides an opportunity to investigate the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the complete biological spectrum of Alzheimer's disease [67]. Deep neural network models have the potential to enhance the precision of differentiating Alzheimer's subjects by identifying common patterns in biological data. These models can be applied to unravel various heterogeneous omics datasets, including DNA methylation from prefrontal area tissue and gene expression.

AI in the management and therapy of alzheimer's disease

Currently, there are no efficient therapies for Alzheimer's disease (AD), and major pharmaceutical industries have scaled back their research efforts in this area due to the extremely low success rate of clinical trials [68-71]. For example, between 2002 and 2012, over 400 clinical trials for AD treatment were conducted, yet only one medication was authorized [72]. This illustrates the challenge of establishing personalized drug strategies and underscores the prospect of exploring innovative strategies for drug discovery.

Machine learning approaches are increasingly being employed for designing personalized drug strategies, gaining popularity, as algorithms for neurodegenerative diseases can be fed comprehensive individual data, including clinical history, transcriptomic, neuroimaging, and biomarker data [73]. Employing unsupervised models in deep learning is one method for classifying patient outcomes and stratifying patients, reducing dimensionality in high-dimensional labeled data. AI presents a new avenue for the development and discovery of novel AD medications.

Given the multifaceted pathways involved in AD pathogenesis, a comprehensive and holistic examination of data related to various pathways is crucial for understanding the disease. Yet, this can be challenging for individual researchers. AI can assist in understanding, prediction, and the development of new medications by integrating data from various sources such as ChEMBL, Ensembl, OmniPath, KEGG, and PubMed to create knowledge graphs connecting genes, diseases, and medications [74, 75]. This strategy helps uncover less apparent connections between Alzheimer's disease (AD) and potential therapeutic targets. However, a drawback is that biological interactions lack granularity, leading to reduced specificity in predictions [76]. Machine learning offers a means of achieving more detailed biological specifications compared to knowledge graphs. Molecular networks can show biological processes that vary during different phases of disease by collecting gene expression data from healthy controls and individual patients. For example, transcriptome data obtained from the brain tissue of persons with late-onset AD and non-AD controls was analyzed using a combination of clustering, Bayesian inference, and co-regulation [77]. Individuals with late-onset AD exhibited high expression levels of immune-related genes, microglial-specific genes encoding the TYROP protein, and other genes. Further validation of the TYROP function in an AD mouse model revealed a deficit of this protein, indicating that it protects the nervous system [78, 79].

Future perspectives on utilization of AI in the treatment of alzheimer's disease

Recent AI approaches in Alzheimer's disease (AD) research have demonstrated promising results by effectively handling vast amounts of biological, environmental, and lifestyle information. These approaches offer efficient, practical, and precise methods for diagnosing AD and assessing the progression of Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) in diverse settings [80-82]. Current research suggests that certain algorithms incorporating both biological and clinical data may distinguish between AD patients, predict AD conversion, or facilitate patient sub-typing. It is anticipated that artificial intelligence (AI) technology will soon contribute to achieving these objectives, generating new hypotheses, and ultimately providing effective treatment options for the disease, despite the current limitations of available data [83]. Future AI models are expected to enhance their resilience and accuracy by incorporating heterogeneous data and leveraging advancements in non-invasive screening tests.

Examples of AI algorithms and datasets (e. g., ADNI, OASIS) used in current AD research

Key AI algorithms used in AD research

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) – Used for analyzing MRI, PET, and CT scans to detect early brain changes.

Example: CNN-based models achieve>90% accuracy in distinguishing AD from MCI and healthy aging.

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Networks – Track disease progression over time using longitudinal data.

Example: LSTM models predict MCI-to-AD conversion up to 5 y in advance.

Support Vector Machines (SVMs) – Applied to biomarker data (CSF, blood, genetic) for classification and early detection.

Example: SVMs improve diagnostic accuracy by combining biomarker and neuroimaging data.

Random Forest (RF) and Gradient Boosting Models (XGBoost, LightGBM) – Identify key genetic and metabolic biomarkers linked to AD risk.

Example: RF models extract genetic risk factors (APOE, TREM2) from large GWAS datasets.

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) – Used to generate synthetic MRI scans for augmenting training datasets and improving AI model robustness.

Example: GANs help detect subtle brain atrophy patterns missed by conventional models.

Autoencoders and Dimensionality Reduction (PCA, t-SNE) – Extract features from high-dimensional neuroimaging and omics data to uncover novel biomarkers.

Example: Autoencoders identify hidden patterns in CSF and plasma biomarkers predictive of AD.

Major datasets used in AI-based AD research

Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) – A large, multi-modal dataset with MRI, PET, CSF biomarkers, and clinical data tracking AD progression.

Open Access Series of Imaging Studies (OASIS-3) – Includes longitudinal neuroimaging and cognitive assessments for healthy and AD patients.

UK Biobank – A vast dataset with genomic, imaging, and health records, enabling AI-driven biomarker discovery.

Australian Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle Study (AIBL) – Provides PET scans, blood biomarkers, and lifestyle data to study early AD.

National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) – Offers clinical and neuropathological data for ML-based disease modeling.

Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) and AMP-AD Knowledge Portal – Contains multi-omics data (RNA-seq, proteomics, GWAS) for AI-driven biomarker identification.

Quantitative results of AI-based diagnostic accuracy compared to traditional methods:

AI-based diagnostic methods outperform traditional approaches by offering higher accuracy, faster processing, and improved early detection. The integration of multi-modal AI models holds promise for cost-effective, scalable, and personalized AD diagnosis.

Limitations in AI algorithms

Data privacy and ethical concerns

Patient Data Security – AI models rely on large-scale patient data (e. g., MRI scans, genetic profiles, EHRs), raising concerns over data breaches and unauthorized access.

Regulatory Challenges – Compliance with General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), and other data protection laws complicates AI model deployment across institutions.

Informed Consent and Data Sharing – Many AI studies use public datasets (e. g., ADNI,), but real-world clinical data is often restricted due to patient confidentiality concerns.

Bias and generalizability issues

Dataset Bias – Most AI models are trained on Western-centric datasets (e. g., ADNI,), leading to poor generalization in underrepresented populations (e. g., Asian, African, Hispanic groups).

Algorithmic Bias – AI models may disproportionately misclassify individuals based on age, sex, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status, affecting diagnostic accuracy.

Overfitting to Limited Datasets – Some deep learning models memorize patterns from small datasets, reducing real-world applicability.

Conventional and innovative approaches in the management and treatment of the disease

Considering the utilization of Drug Delivery Systems (DDS) to transport medications across the Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) for Alzheimer's disease (AD) treatment, Nano DDSs are composed of biodegradable materials, including inorganic metals, lipids, and both natural and synthetic polymers.

Traditional oral-based AD therapies

Cholinesterase inhibitors, including the oral formulations of donepezil, rivastigmine, tacrine, and memantine, represent the primary treatment approach for Alzheimer's disease (AD). These inhibitors are prioritized as they decrease the breakdown of acetylcholine in the synaptic gap, compensating for its deficiency [84]. Although tacrine was the first Cholinesterase Inhibitor (ChEI) approved for the therapy of mild to moderate AD, its use is now restricted to very specific circumstances due to its hepatotoxic adverse effects [85]. Traditional dosage forms and their limitations are listed in table 1.

Table 1: Drugs and their dosage form used traditionally and their limitations

| S. No. | Drug | dosage form | Limitations |

| 1 | Tacrine | Capsule | Hepatotoxic side effects |

| 2 | Donepezil | Tablets | Related to the Gastrointestinal tract and sleep disturbance has been observed in a few patients |

| 3 | Rivastigmine | capsules and oral solution | mainly gastrointestinal disorders during the titration phase |

Innovative drug delivery systems for AD treatment

In addition to conventional oral formulations, various administration modes can be employed for Alzheimer's disease (AD) treatment. Alternatives include orally disintegrating or sublingual formulations, as well as intranasal, pulmonary, or transdermal forms. Recently, several nanotechnology-based drug delivery systems have also emerged. Moreover, AD patients often find it more convenient to adhere to less frequent dosing regimens, such as a once-daily protocol, compared to multi-day fractionated doses.

Buccal and oral conventional drug delivery systems

Oral Extended-Release (ER) formulations, such as tablets or capsules, now allow therapeutic agents that previously required multiple daily administrations to be delivered just once per day by limiting drug release. The potential advantages of oral ER products are widely recognized, including reduced dosing frequency, steady-state plasma concentration levels that mitigate adverse effects associated with fluctuating drug levels, consistent drug levels, uniform drug effects, and enhanced compliance and convenience. However, potential drawbacks include prolonged lag times to peak plasma levels, unexpected or diminished bioavailability, particularly in elderly patients, the risk of dosage dumping and potential persistent toxicity, restrictive dosing, and higher formulation costs.

A commercially available extended-release oral drug delivery system comprises a capsule containing both donepezil and memantine, designed for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. This formulation functions by inhibiting glutamate receptors (NMDA) and inhibiting the cholinesterase enzyme.

Injectable depot-forming and transdermal and drug delivery systems

Transdermal delivery can offer numerous advantages over traditional delivery methods for individuals who struggle with adherence or have difficulty swallowing food or beverages. This approach may mitigate certain adverse effects; for example, it can bypass first-pass effects [86], lead to reduced doses due to a decreased metabolic pathway, and simplify the daily dosing regimen. Moreover, easy patch removal ensures prompt termination of drug delivery when side effects begin to manifest as described in fig. 5. A few examples of transdermal drug delivery systems used in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease are listed in table 2.

Fig. 5: Mechanism of action of transdermal drug delivery system for Alzheimer's disease [87]

Table 2: There are few transdermal medication delivery technologies for Alzheimer's disease therapy

| S. No. | Drugs | Transdermal technique | Significance | References |

| 1 | Phenserine | Ointment form | Good efficacy in brain | [88] |

| 2 | Physostigmine | Patch | Stable plasma levels, Stability of absorption from 8h to 22h after administration | [89, 90] |

| 3 | Tacrine | Iontophoresis | Sustained release | [91] |

| 4 | Rivastigmine | Patch matrix drug adhesive | Reduced surface and thickness of patch with prolonged penetration | [92] |

| 5 | Donepezil | Patch | Faster influx | [93] |

| 6 | Galantamine | Patch | Stable concentration over 24h | [94] |

Potential of transdermal delivery systems fin the treatment of AD

Sustained and controlled drug release

TDDS enables steady plasma drug levels over time, avoiding sharp peaks and troughs seen with oral dosing. Prevents dose dumping and minimizes fluctuations in cognitive function.

Bypassing the first-pass metabolism

Many AD drugs (e.g., rivastigmine, donepezil) undergo significant hepatic metabolism, reducing bioavailability.

TDDS delivers drugs directly into circulation, enhancing efficacy at lower doses.

Improved blood-brain barrier (BBB) penetration

Novel TDDS formulations (e. g., nanoemulsions, microneedle patches) can enhance CNS drug delivery.

Lipophilic drugs with small molecular weights are efficiently absorbed through the skin, increasing brain bioavailability.

Reduced gastrointestinal (GI) and systemic side effects

Oral cholinesterase inhibitors (e.g., rivastigmine) often cause nausea, vomiting, and gastric irritation.

TDDS bypasses the GI tract, reducing these side effects while maintaining therapeutic efficacy.

Enhanced patient compliance and convenience

Many AD patients struggle with swallowing pills (dysphagia) and complex medication schedules.

Patches are easy to apply, require less frequent dosing, and improve adherence in elderly patients.

Lower dosing frequency

Extended-release transdermal patches (e. g., rivastigmine patch) require only once-daily application, compared to multiple daily oral doses.

Provide a critical evaluation of the potential and limitations of intranasal and nanotechnology-based delivery systems in crossing the BBB:

Nasal route

There are several methods to deliver medications to the Central Nervous System (CNS) without traversing the Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB). These approaches may involve invasive procedures such as surgical exposure and injection delivery [95], or they can utilize sensory organs, as exemplified by intranasal delivery. Intranasal administration is the most straightforward means of delivering medicine to the CNS, bypassing the blood flow clearance and potential adverse effects. The trigeminal nerve (respiratory epithelium) and olfactory nerve (olfactory epithelium), crucial for optimal drug delivery through this route, facilitate interaction between the cerebrospinal nervous system and the surrounding environment as described in fig. 6. [96]. Drugs can reach the cerebrospinal nervous system (CNS) from the nasal cavity through slower intra-axonal transport or more rapidly through paracellular transport via the perineural space around the neurons into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or interstitial fluid of the brain [97]. A few examples of nasal drug delivery systems for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease are listed in table 3.

Fig. 6: Mechanism of action of nasal drug delivery system for Alzheimer's disease [98]

Table 3: Examples of Alzheimer's disease therapy nasal drugs delivery systems

| S. No. | Drugs | Description | Significance |

| 1 | Physostigmine (NXX-006) | Physostigmine analogue and acetylcholinesterase inhibitor | Absorption into the systemic circulation happens extremely quickly and completely, then the plasma concentrations quickly start to fall. |

| 2 | Rivastigmine | Formulated as conventional multilamellar liposomes | Relative bioavailability was increased compared to intranasal solutions [99] |

| 3 | Tacrine | Centrally acting cholinesterase inhibitor | After intranasal treatment of tacrine microemulsion, tacrine was transported into mice brains more quickly and to a greater extent, and memory loss in scopolamine-induced amnesic mice was restored more quickly [100]. |

Drug delivery systems based on nanotechnology

The integration of nanotechnology into pharmaceutical sciences is expected to bring significant advancements to the therapy of neurodegenerative disorders. The dispersion of active substances in healthy tissues can lead to serious adverse effects, highlighting the importance of targeting and localized delivery in Alzheimer's disease (AD) therapy. There is increasing attention to designing drug delivery systems that can target pharmacologically active compounds near their intended sites of action. These systems, with a higher affinity for molecular interactions with biological systems compared to dendrimers and polymeric micelles, have gained prominence, utilizing their tunable size, enhanced reliability, and surface tailorability [87]. Nanotechnology devices hold the potential to circumvent the limitations of the Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) by selectively conjugating active molecules with ligands exhibiting high affinity for the BBB [86, 91]. The impact of nanotechnology on neurology extends to the ability to create precise drug targets outside the BBB, develop potential regenerative therapeutics, and pioneer innovative diagnostic tools for early disease diagnosis. Various examples of nanotechnology-based drug delivery systems used in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease are listed in table 4.

Table 4: Examples of nanotechnology-based drug delivery systems for the therapy of Alzheimer's disease

| S. No. | Drug | Description | Significance | Reference |

| 1 | Donepezil | Encapsulated by PLGA microparticles Designed by oil in water emulsion solvent evaporation approach |

According to the experimental results, donepezil-loaded microparticles might be a viable option for a sustained drug delivery system that only needs to be administered once per month. | [101] |

| 2 | Tacrine | The drug was formulated as microparticles. | Due to related gastrointestinal, hepatic, and cholinergic side effects, clinical use has been restricted. | [102] |

Understanding the microenvironment of the Central Nervous System (CNS) and the surface receptors expressed in the brain of Alzheimer's disease (AD) patients allows for the creation and utilization of various nanocarriers for targeted drug administration.

Fig. 7: Various nanotechnology-based drug delivery systems for Alzheimer's disease treatment [115, 143, 152]

The fig. 7 illustrates various nanotechnology-based drug delivery systems, each with distinct structural features and advantages. Polymeric nanoparticles provide controlled drug release and stability, making them ideal for targeted therapy. Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) and nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs) enhance drug stability and bioavailability, with NLCs offering superior drug-loading capacity. Liposomes, composed of phospholipid bilayers, improve drug solubility and biocompatibility, enabling targeted delivery. Dendrimers, with their branched structure, allow high drug loading and precise control over molecular interactions. Microemulsions (water-in-oil, oil-in-water, and bicontinuous types) and nanoemulsions enhance drug solubility, stability, and absorption, making them suitable for hydrophobic drugs. Overall, these nanocarriers improve bioavailability, enable controlled and sustained drug release, and reduce systemic side effects, making them crucial in cancer therapy, neurodegenerative diseases, and other medical applications.

As represented in above fig. 7, the next sections address the six categories of Nano DDSs for treating AD that can cross the BBB. [103-106].

Polymeric nanoparticles

Polymeric nanoparticles (NPs) serve as colloidal carriers that encapsulate drugs through either chemical or non-covalent adsorption on the surface, in either a solid-state or fluid form [107]. These delivery systems offer advantages such as sustained drug release, minimal toxicity, immunogenic response, good stability, biocompatibility, and biodegradability, along with ease of manufacturing [108]. Various polymeric particles used in the treatment of AD are listed in table 5. Nanoparticles typically have a size ranging from 1 to 100 nm [109]. Adjusting the drug-to-polymer ratio and coating nanoparticles with cell-penetrating peptides, surfactants, or antibodies allows for the modification of polymeric nanoparticles' characteristics, including blood circulation time, size, zeta potential, drug release rate, and targeting capabilities.

Lipid nanoparticles

Lipid nanoparticles (NPs) are colloidal dispersions that offer a potential alternative to other carriers like nanoemulsions, liposomes, and polymeric NPs, with Nanostructured Lipid Carriers (NLCs) and solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) representing two prominent categories [115]. SLNs are made up of a lipid core that remains in a solid state at the body and at room temperature. Various examples of solid lipid nanoparticles are listed in table 6. To overcome certain drawbacks of SLNs, such as reduced drug loading capacity and shortened stability due to lipid polymorphic shifts to more stable forms, NLCs are created by combining solid and liquid lipids. It's noteworthy that factors like drug lipophilicity, surfactant usage, and the production process play crucial roles in determining the drug incorporation efficiency in SLNs and NLCs [116]. Various examples of nanostructured lipid carriers used in treating Alzheimer's disease are listed in table 7.

Lipid nanoparticles (lipid NPs) present the advantage of potentially minimal toxicity while preserving the benefits associated with other carriers, such as deterioration resistance, sustained drug release, drug targeting, and scalability [117]. Research indicates that lipophilic lipid nanoparticles may traverse the blood-brain barrier (BBB) through an endocytotic process, accumulating in the cerebrospinal nervous system (CNS). Additionally, due to their small size, lipid nanoparticles can be administered intravenously without the risk of uptake by the mononuclear phagocyte system, reducing the chance of macrophage uptake.

Liposomes

Liposomes, spherical phospholipid vesicles with a bi-layered structure, contain a water-filled interior and can be produced in a range of sizes, typically spanning from 50 nm to 100 m. The surface of liposomes can exhibit various charges, and their structure may be uni-, bi-, or multi-lamellar, depending on the choice of phospholipids and the manufacturing process. Modifications in liposome composition have given rise to diverse variations such as ethosomes, pyrosomes, transfersomes, and others [131-133]. These lipid-based structures are considered non-toxic and biocompatible, primarily due to their phospholipid makeup [134, 135]. A few examples of liposomes used in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease are listed in table 8. By encapsulating drugs within lipid bubbles, liposomes can accommodate both hydrophilic and lipophilic substances [136].

Nanoemulsions

Nanoemulsions are heterogeneous systems, stabilized by one or more surfactants, comprising dispersed oil or water droplets in oil or aqueous media. The intriguing aspect of nanoemulsions lies in the diverse sizes of oil droplets, ranging from 10 to 100 nm, rendering them promising for the delivery of drugs. Moreover, these oil droplets can effectively solubilize and preserve lipophilic compounds, with the advantage of easy scalability from laboratory to industrial manufacturing. A few examples of nanoemulsions used in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease are listed in table 9. However, certain drawbacks exist, such as storage instability leading to phase separation and a sudden release impact [106, 142, 143]. Consequently, mucoadhesive nanoemulsions have the potential to deliver poorly soluble curcumin intranasally, showcasing advantages over other nanoemulsions and drug solutions [144].

Table 5: Various polymeric nanoparticles used to treat AD

| S. No. | Therapeutic moiety | Methods | Dose | Inferences | References |

| 1 | Curcumin | A water-soluble polymeric nanoparticle formulation, NanoCurc™, was engineered to enhance the bioavailability of curcumin. | 25 mg/kg twice daily | Athymic mice treated with NanoCurc™ exhibited elevated levels of glutathione (GSH), decreased levels of H2O2, and reduced caspase 7 and 3 activity in the brain. | [110] |

| 2 | Withaferin-A | The solvent evaporation process was employed to extract withaferin-A and load it into PLGA nanoparticles. Nanoparticle evaluation included assessments of zeta potential, particle size, surface morphology, loading effectiveness, and in vitro drug release tests. | A steady release of withaferin-A was observed from the nanoparticles. Withaferin-A could serve as a viable option for the treatment of neurodegenerative conditions. | [111] | |

| 3 | Estradiol | Estradiol-containing nanoparticles were prepared using a single emulsion process, and the T-80 layer was achieved by incubating the reconstituted nanoparticles with varying concentrations of T-80. The pharmacokinetics of estradiol nanoparticles were assessed about T-80 coating, and the optimization of the T-80 coating procedure for the nanoparticles was carried out. | 0.2 mg | Furthermore, the concentrations of estradiol in the brain closely resembled those achieved after administering an equivalent dose of the drug through a 100% bioavailable intramuscular route, indicating an increased proportion of bioavailable drug reaching the brain when administered orally. Moreover, the nanoparticle-exposed group demonstrated efficacy in reducing amyloid beta-42 (A-42) staining in the hippocampal region of the brain. These collective results suggest the potential of nanoparticles for facilitating oral transport of estradiol to the brain. | [112] |

| 4 | Phytol | Phytol-loaded PLGA nanoparticles were fabricated by evaporating a solvent from an oil-in-water emulsion. Analysis through dynamic laser scattering (DLS) demonstrated that the phytol-PLGA NPs were nanosized with smooth surfaces and spherical morphology, as confirmed by a field emission scanning electron microscope. Furthermore, the biocompatibility of the drug/polymer ratio was examined using powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) analysis and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR). | 30-50µg/ml in Neuro2a cells | To our knowledge, this study represents the inaugural investigation into the formulation of phytol-PLGA NPs, enhancing the solubility of phytol and potentially aiding in BBB permeability. This facilitates a regulated release of phytol to the brain, offering potential advantages for sustained therapeutic effects. The results imply that both phytol and phytol-PLGA NPs could be considered novel therapeutic strategies for the therapy of Alzheimer's disease. | [113] |

| 5 | Galantamine | In this study, a nano-emulsion templating method, characterized by low-energy emulsification, was employed to create galantamine-loaded nano-emulsions. These nano-emulsions were subsequently evaporated to yield polymeric nanoparticles loaded with galantamine. This approach was deemed suitable as it yielded nanoparticles that were biocompatible, biodegradable, and safe, possessing the essential properties for intravenous administration. | 50µl to neuronal cells | Upon encapsulation into non-cytotoxic nanoparticles at the required therapeutic dose, the drug's enzymatic activity was preserved at 80%. For the therapy of neurodegenerative diseases, novel galantamine-loaded polymeric nanoparticles have been developed for the first time using the nano-emulsification method. These nanoparticles exhibited the essential characteristics to serve as innovative drug delivery systems. | [114] |

Table 6: Examples of the solid lipid nanoparticles used to treat AD

| S. No. | Therapeutic moiety | Methods | Inferences | References |

| 1 | Erythropoietin | In this study, the double emulsion solvent evaporation technique (W1/O/W2) was utilized to formulate Solid Lipid Nanoparticles loaded with Erythropoietin (EPO-SLNs). | The EPO-SLN, in comparison to free EPO, exhibited a reduction in beta-amyloid plaque deposition, the ADP/ATP ratio in the hippocampus, and oxidative stress. Therefore, the formulated SLN presents a potential and effective approach for the safe delivery of Erythropoietin in Alzheimer's disease. | [118] |

| 2 | Resveratrol and grape extract | The study showed that extracts derived from grape skin and seeds contribute to the inhibition of Aβ aggregation. However, resveratrol undergoes rapid breakdown into phenolic group conjugates with sulfates and glucuronic acid in intestinal epithelial cells and the liver following intravenous injection (within<2 h), which are then excreted. In the current investigation, we illustrate that solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) functionalized with the anti-transferrin receptor monoclonal antibody (OX26 mAb) have the potential to serve as a carrier for delivering the extract to target the brain. | Examination of human brain-like endothelial cells demonstrates that OX26 SLNs exhibit superior cellular uptake compared to both conventional SLNs and SLNs functionalized with a non-specific antibody. Consequently, when OX-26 is employed for functionalization, these diverse SLNs display enhanced transcytosis capabilities. | [119] |

| 3 | Ferulic acid | FA-loaded SLNs were formulated with Compritol as the lipid and polysorbate 80 as the surfactant. The optimization process was conducted using a 32 Central Composite Design (CCD). | The results successfully show enhanced anti-AD efficacy, better mucoadhesion, and permeability of the nasal mucosa, longer release of the drug, enhanced potential for patient compliance, robustness, as well as safety of the proposed lipidic nanoconstructs of FA administered via the intranasal route. | [120] |

| 4 | Nicotinamide | Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) loaded with nicotinamide were developed and functionalized using phosphatidic acid (PA), phosphatidylserine (PS), and polysorbate 80 (S80). The particles obtained were identified and evaluated for toxicity, in vivo efficacy, and biodistribution through various administration methods. | In an Alzheimer's disease rat model, the results of memory and spatial tests, including the Morris water maze, along with biochemical and histopathology analysis, indicated the efficiency of intraperitoneal infusion of phosphatidylserine (PS)-functionalized SLNs in enhancing cognition, protecting neuronal cells, and lowering tau hyperphosphorylation. | [121] |

| 5 | RVG-9R-BACE1 siRNA | To enhance the transcellular route in neuronal cells, we opted for a cell-penetrating peptide called RVG-9R, a short peptide derived from the glycoprotein of the rabies virus. The optimal molar ratio between BACE1 siRNA and RVG-9R was determined, and the two complexes were subsequently encapsulated. We propose the use of uncoated and chitosan-coated solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) as a nasal delivery strategy that can leverage both trigeminal nerve channels and olfactory pathways. | The positive charge of the coating formulation enhanced the mucoadhesive properties of the particles, prolonging their residence in the nasal cavity. Caco-2, serving as a model with epithelial-like characteristics were employed to assess the cellular transit of siRNA delivered by SLNs. We found that siRNA released from any of the formulations under investigation, especially from chitosan-coated SLNs, crossed the monolayer to a greater extent than siRNA released alone. |

[122] |

| 6 | Chrysin | In the current study, we formulated CN-loaded SLNs (CN-SLNs) and assessed their therapeutic potential in mitigating neuronal damage induced by Aβ-25-35 administration. | Our findings suggest that encapsulating CN in SLNs can enhance both the oral bioavailability of CN and its therapeutic effectiveness at lower doses. Consequently, the results highlight the potential use of CN-SLNs as a brain-targeted therapy strategy to mitigate the impact of Alzheimer's disease globally. | [117] |

| 7 | Galantamine hydrobromide | Galantamine hydrobromide was formulated into solid-lipid nanoparticles using biodegradable and biocompatible materials to address the associated drawbacks. The selected solid-lipid nanoparticles, loaded with galantamine hydrobromide, exhibited a nano-colloidal size of less than 100 nm and achieved maximum drug entrapment of 83.42±0.63%. | In comparison to the conventional medication, the formulated carriers demonstrated approximately double the bioavailability. Consequently, the solid-lipid nanoparticles loaded with galantamine hydrobromide show promise as a potential delivery system, particularly for conditions such as Alzheimer's. | [124] |

Table 7: Examples of nanostructured lipid carriers used to treat AD

| S. No. | Therapeutic moiety | Methods | Inferences | References |

| 1 | Berberine | In this investigation, nanostructured lipid carriers loaded with berberine were produced through the utilization of melt-emulsification and ultrasonication techniques. | It was observed that berberine-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers (berb-NLCs) exhibited enhanced behavioral characteristics in vivo than pure berberine in Albino Wistar rats. The enhanced efficacy of these nanostructured lipid carriers in an animal model of Alzheimer's disease suggests their potential utility for targeted delivery to the brain. | [125] |

| 2 | Astaxanthin | The development of AST-NLCs involved the application of hot high-pressure homogenization, wherein optimization of processing variables, including the overall drug-to-lipid ratio, the ratio of liquid lipid to solid lipid, and the quantity of surfactant, was carried out. | Intravenous administration of optimized AST-NLCs demonstrated substantial reductions in oxidative stress, the amyloidogenic pathway, apoptosis, and neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease (AD)-like rats, in contrast to standard AST solution. | [126] |

| 3 | Curcumin | In the ongoing study, nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs) were employed to enhance the effectiveness of curcumin in addressing cognitive deficits induced by Alzheimer's disease (AD) in a rat model. | This method proved successful in mitigating Alzheimer's disease (AD)-induced neurological abnormalities and memory deficits. These findings suggest that utilizing Cur-NLCs could serve as a basis for further exploration in the realms of AD treatment and prevention. | [127] |

| 4 | Donepezil | The investigation aimed to assess the possibility of nanostructured lipid carrier-based gels (NLC gel) in improving the skin distribution of donepezil-free base (DPB). Through in vitro experiments assessing DPB skin delivery, the ingredientsof nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs) were chosen based on their observed augmentative effects. | The outcomes from in vitro skin permeation investigations showed that the drug skin permeation of DPB-NLC gel was enhanced not only due to the augmenting influence of its ingredients but also because of the additional enhancement conferred by the lipid nanocarriers. This heightened drug flux through the skin. Consequently, DPB-NLC gel stands out as a noteworthy formulation for enhanced therapy targeting Alzheimer's disease. | [128] |

| 5 | Salvia Officinalis | The objective of this investigation was to formulate a nanostructured lipid carrier (NLC) loaded with freeze-dried Salvia officinalis extract (FSE) for intranasal administration, followed by its subsequent evaluation. The NLC was created through the solvent evaporation method, with optimization achieved using the central composite design (CCD) of trials. | Examinations of protein adsorption indicated that the NLCc surface exhibited the highest level of protein adsorption (55.97±0.75%), while the NLCp surface displayed the lowest protein adsorption (43.53±0.07%). Enhanced ORAC assay results demonstrated that NLCo and NLCc possessed superior antioxidative activity compared to FSE. Cell culture experiments suggested the potential of the prepared NLCs for the controlled release of FSE with a specific brain-targeting capability.Top of Form | [129] |

| 6 | Resveratrol | The primary aim of the current investigation was to design an intranasal delivery in situ gel incorporating resveratrol based on nanostructured lipid carriers. A lipid carrier loaded with resveratrol was developed using a melt emulsification-probe sonication method, and then comprehensive evaluation and optimizationwere conducted. | Pharmacokinetic investigations unveiled that the in situ gel exhibited increased drug distribution in the brain, signifying the safety and efficacy of the novel formulation when administered intranasally. Consequently, it can be inferred that a portion of the medication from the developed formulation might have been absorbed through the olfactory pathway, making the intranasal route an intriguing approach for Alzheimer's disease therapy. | [130] |

Table 8: Examples of liposomes used in the treatment of AD

| S. No. | Therapeutic moiety | Methods | Inferences | References |

| 1 | H102-peptide | Liposomes of H102 were created employing an altered thin film hydration technique, and their delivery properties were investigated on monolayers of Calu-3 cells. Furthermore, the dry kinetics in the blood and brains of rats were assessed. | The developed liposomes consistently traversed Calu-3 cell monolayers. Successful transport of H102 to the brain was achieved via an intranasal route of delivery, with the area under the curve of H102 liposomes in the hippocampus being 2.92 times more than that of the solution group. Even at a lesser dosage than the H102 intranasal solution, H102 liposomes exhibited a substantial improvement in spatial memory deficiency in the rat model of Alzheimer's disease, enhancing ChAT and IDE activity while preventing plaque accumulation. H102 nasal formulations reported no toxicity on the nasal mucosa. | [137] |

| 2 | Curcumin | These newly developed liposomes efficiently encase hydrophobic curcumin, resulting in particles with a size below 200 nm and a polydispersity index less than 0.20. This characteristic renders them optimal for penetrating the blood-brain barrier. | These exoliposomes proved non-toxic and were internalized in zebrafish embryos, accumulating in lipid-rich areas such as the yolk sac and brain. Their stability, ability to protect cargo and uptake by neuronal cells make these innovative carriers a promising and effective method for delivering medications to the brain. The internalization of liposomes offers a viable alternative treatment approach for Alzheimer's disease (AD), facilitating the release of therapeutic biomoleculesand achieving successful neuroprotection. | [138] |

| 3 | Apolipoprotein E2 | Liposomes incorporating a glucose transporter-1 (GLUT-1) targeting strategy were employed for efficient transport of ApoE2 containing plasmid DNA (pApoE2) to the brain. To improve brain targeting and cellular internalization, the liposomes were surface-functionalized with the GLUT-1 targeting ligand mannose (MAN) and a cell-penetrating peptide (CPP). Among several CPPs, the rabies virus glycoprotein peptide (RVG) was utilized as a cell permeation promoter. | A single injection of PenMAN-and RVGMAN-functionalized liposomes, administered through the tail vein, led to a potential enhancement in pApoE2 transfection in the brains of C57BL/6 mice during in vivo efficacy investigations, without causing evident harm. These findings underscore the potential of surface-modified liposomes as a safe and efficient means of delivering the pApoE2 gene to the brain for the therapy of Alzheimer's disease (AD). | [139] |

| 4 | Galanthamine hydrobromide | For the initial time, the intranasal delivery of GH-loaded flexible liposomes has been evaluated to assess both the efficacy of acetylcholinesterase inhibition and the drug kineticbehavior of GH in rat brains. | The results suggest that the intranasal delivery of flexible liposomes containing GH facilitates the effective transport of GH into various brain regions. This indicates the potential of this approach for targeted drug delivery to the brain in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease (AD). | [140] |

| 5 | Rivastigmine | The objective of the investigation was to create liposomes encapsulating rivastigmine (Lp) and liposomes altered with cell-penetrating peptides (CPP-Lp) to improve pharmacodynamics upon intravenous (IV) administration while minimizing adverse effects. | As per the data, rivastigmine liposomes, especially CPP-Lp, enhance pharmacodynamics by improving blood-brain barrier permeability and facilitating entry into the brain via the nasal olfactory route after intravenous (IV) administration. | [141] |

Table 9: Examples of nanoemulsions used in the therapy of Alzheimer's disease

| S. No. | Therapeutic moiety | Methods | Inferences | References |

| 1. | Memantine | The production of nanoemulsion involved homogenization and ultrasonication processes. Characterization of the resulting nanoemulsions, including in vitro release profiles and antioxidant capabilities, was conducted. For in vivo investigations, memantine was radiolabeled with technetium pertechnetate. | Antioxidative assays confirmed that the inclusion of memantine in a nanoemulsion retained its antioxidative properties, and the nanoemulsion exhibited 98% cell survival. Gamma imaging and biodistribution data provided additional evidence of the formulation's enhanced absorption, occurring 1.5 h post-intranasal administration, with aradioactivity content of 3.6±0.18%/g. The specifically designed nanoemulsionfacilitates the direct delivery of memantine to the brain from the nasal cavity. | [145] |

| 2 | Donepezil hydrochloride | we formulated an oil-in-water (o/w) nanoemulsion (NE) containing donepezil. The characterization of the developed NE involved assessing polydispersity index (PDI), zeta potential, and particle size. In vitro release tests were conducted to monitor the release of the medication. | According to the study findings, the specifically designed NE loaded with donepezil hydrochloride represents a distinctive approach for treating Alzheimer's disease, involving drug transfer from the nasal route directly to the brain. | [146] |

| 3 | Tegaserod | This study explored the potential therapeutic effects of tegaserod, a drug typically used for irritable bowel syndrome, in the context of Alzheimer's disease. To explore its potential for repurposing, nanoemulsions loaded with tegaserod were formulated and modified with a blood-brain barrier shuttle peptide. | Emphasis was placed on tegaserod's inhibitory action on butyrylcholinesterase and its neuroprotective effects at the cellular level, indicating its potential for AD treatment. For optimal drug delivery, tegaserod was encapsulated in monodisperse lipid nanoemulsions (Tg-NEs) with a neutral zetapotential, measuring approximately 50 nm, to limit regional distribution following intravenousadministration. Future preclinical investigations could further explore the repurposing of tegaserod for the treatment of AD utilizing the observed peptide-22 functionalized Tg-NEs. | [147] |

| 4 | Osthole (OST) | In this study, an OST nanoemulsion (OST-NE) was formulated using the pseudo-ternary phase diagram technique, a common approach for optimizing formulations based on the solubility of OST in surfactants and cosurfactants. | The results of the investigation suggest that intravenous administration of OST-NE enhances the bioavailability of OST. Even at a low dosage, OST-NE shows promise as a potential substitute for increasing the bioavailability of OST in both the prevention and therapy of Alzheimer's disease. | [148] |

| 5 | Naringenin | The current investigation aimed the design a nanoemulsioncontaining naringenin and its neuroprotective properties against β-amyloid-induced neurotoxicity in an SH-SY5Y cell line. | the nanoemulsion diminished the values of phosphorylated tau in SH-SY5Y cells treated with β-amyloid. These findings indicate that a nanoemulsion incorporating naringenin could be an effective therapy for Alzheimer's disease. | [149] |

Microemulsions

A microemulsion is defined as a thermodynamically stable liquid solution consisting of an amphiphile, water, and oil, exhibiting optical isotropy. The key distinction between emulsions and microemulsions lies in their thermodynamic stability; emulsions, despite possessing good kinetic stability, are inherently thermodynamically unstable and will eventually phase-separate [150]. Various examples of microemulsions used in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease are listed in table 10. Emulsions and microemulsions differ visually, with emulsions appearing murky while microemulsions are translucent or clear. Considering the relative safety and commercial manufacturing costs of both systems, this distinction holds significant implications [151].

Dendrimer

It has been 20 y since dendrimers, also known as cascade molecules and arborols, were discovered [157]. A dendrimer is a name used to graphically represent the structure of this new family of molecules (Greek: dendron. tree, meros. portion). Although the term "dendrimers" has been established in the meantime, the older name "cascade molecule" is highly appropriate to construct their nomenclature [158]. A few examples of dendrimers used in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease are listed in table 11. These molecules typically come from a core, and with each new branching unit, they ramify more and more like a tree.

Potential and limitations of intranasal and nanotechnology-based delivery systems in crossing the BBB

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) poses a major challenge in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) drug delivery, limiting the entry of therapeutic agents into the central nervous system (CNS). Intranasal and nanotechnology-based drug delivery systems have emerged as promising strategies to enhance CNS drug bioavailability. However, both approaches have significant potential and limitations.

Table 10: Examples of microemulsions used for the treatment of AD

| S. No. | Therapeutic moiety | Methods | Inferences | References |

| 1. | Morin hydrate | The primary objective of our investigation is to design and examine morin hydrate-loaded microemulsion and to analyze the potential of microemulsion through intranasal delivery. This is the first instance of administering the morin hydrate-loaded microemulsion in AD to minimize oxidative stress in the brain. | . A substantial (P 0.05) decrease in measured pharmacodynamics characteristics was seen after intranasal injection of morin hydrate-loaded microemulsion in comparison to the sham control group. Daily chronic treatment with a morin-loaded microemulsion until the 21st day substantially improved memory in Wistar rats with STZ-induced dementia. | [152] |

| 2 | Donepezil | The formation of pseudo-ternary phase diagrams led to the development of the Micro Emulsion, which can be identified using transmission electron microscopy and dynamic light scattering. Evaluations were made on the flow characteristics, optical stability viscosity, and stability during storage at various temperatures. Finally, tests of ex vivo penetration through porcine nasal mucosa and in vitro release were completed. | The results of the morphological examination showed that the droplets had a smooth, regular surface and a spherical shape. No destabilization processes were visible in the optical stability. The ex vivo permeation profile revealed that the ME followed a hyperbolic kinetic model and that the greatest quantity that could be permeated was around 2000 g, which is equivalent to 80% of the drug's initial starting amount. The DPZ release profile suggested that the ME followed this model. | [153] |

| 3 | Ibuprofen | . Drug delivery to the target brain is non-invasive and direct with intranasal administration via the olfactory pathway. Rats' brain absorption of a new ibuprofen microemulsion was characterized, and evaluated. | Additionally, in vivo, tests on rats showed that the microemulsion delivered ibuprofen to the brain at a rate that was four times greater than that of the reference solution, as well as nearly four and ten times greater than that of intravenous and oral doses. This study offers a novel delivery method for the therapy of Alzheimer's disease. | [154] |

| 4 | Piperine | In this study, bioactive surfactants are used to enhance PIP targeting to the brain in the usual, safe doses. Selected ME systems included Transcutol HP (co-surfactant), Caproyl 90 (co-surfactant), Tween 80/Cremophor RH 40 (surfactant), and Caproyl 90 (oil). | The in vivo data demonstrated that microemulsion had a better impact than free PIP. The safety of microemulsion on brain cells was demonstrated by the results of colchicine-induced brain toxicity. However, toxicological findings indicated a potential nephrotoxicity of microemulsion. In comparison to the free medication, oral microemulsion improved the efficacy of PIP and improved its transport to the brain. However, the toxicity of this nanosystem should be carefully considered when using it over an extended period. | [155] |

| 5 | Huperzine A (HA) and Ligustrazine phosphate (LP) | The current work set out to develop a novel microemulsion-based patch that would distribute both ligustrazine phosphate (LP) and huperzine A (HA) transdermally. The lamination process was used for making the transdermal microemulsion patches. | . The transdermal combination therapy of HA and LP demonstrated greater benefits for treating amnesia than monotherapy, according to the findings of the pharmacodynamic investigations. After transdermal delivery at numerous dosages over 9 days, the anti-amnesic effects were likewise validated in rats that had been given scopolamine to produce amnesia. The effectiveness showed a dose-dependent pattern. The microemulsion-based transdermal patch with HA and LP may offer a workable method for preventing Alzheimer's disease, in light of the foregoing. |

[156] |

Table 11: Examples of dendrimers used to treat AD

| S. No. | Dendrimers | Methods | Inferences | References |

| 1 | Multifunctional Polyamidoamine Dendrimer |

Tocopheryl polyethylene glycol succinate-1000 (TPGS), serving as a matrix carrier for the delivery of the neuroprotective compound piperine (PIP), was combined with multifunctional polyamidoamine (PAMAM) dendrimer to mitigate the toxicity associated with Aβ fibrils. This resulted in the development of a PIP-TPGS-PAMAM dendrimer aimed at reducing the toxic impact of Aβ1-42 fibrils on SH-SY5Y cells. The synthesis of PIP-TPGS-PAMAM involved the creation of TPGS-PAMAM through a carbodiimide coupling procedure, and PIP was encapsulated in the dendrimer using a solvent injection approach. | The outcomes of our study demonstrated that PIP-TPGS-PAMAM effectively mitigated neuronal cell toxicity induced by Aβ1-42, showcasing significant potential for neuroprotection and therapeutic prospects in Alzheimer's disease. | [159] |