Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 4, 2025, 19-29Review Article

ADVANCING CURCUMIN APPLICATIONS IN HEPATOCELLULAR CARCINOMA: INSIGHTS INTO PHARMACOKINETICS, PHARMACODYNAMICS AND NANODELIVERY SYSTEMS

RESHMA T. MATE1*, ANURADHA N. CHIVATE2, NAMDEO R. JADHAV3, NIRANJAN D. CHIVATE4

1Krishna Institute of Pharmacy, Krishna Vishwa Vidyapeeth (Deemed to be University), Karad-415539, Maharashtra, India. 2Department of Pharmacology, Krishna Institute of Pharmacy, Krishna Vishwa Vidyapeeth (Deemed to be University), Karad-415539, Maharashtra, India. 3Department of Pharmaceutics, Krishna Institute of Pharmacy, Krishna Vishwa Vidyapeeth (Deemed to be University), Karad-415539, Maharashtra, India. 4Department of Pharmaceutics, Krishna Charitable Trust’s Krishna College of Pharmacy, Karad-415539, Maharashtra, India

*Corresponding author: Reshma T. Mate; *Email: mreshma020@gmail.com

Received: 17 Jan 2025, Revised and Accepted: 15 Apr 2025

ABSTRACT

This review explores therapeutic potential of curcumin (CU) in Hepato Cellular Carcinoma (HCC), with a focus on its molecular mechanisms of action and the strategies developed to overcome its clinical limitations.

CU exerts anti-cancer effects by modulating critical signaling pathways, including Wingless Integration site1/β-Catenin) Wnt/β-catenin, Phosphatidyl Inositol 3-Kinase, and Protein Kinase B (PI3K/Akt), Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) and Nuclear Factor Kappa B (NF-κB), thereby inhibiting the progression of HCC. It induces Growth 1/Synthesis (G1/S) phase cell cycle arrest, triggers apoptosis via the mitochondrial pathway and activates tumor suppressor genes such as tumor Protein p53 (p53). Additionally, it demonstrates anti-angiogenic activity through downregulation of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) and exhibits antioxidant properties by neutralizing Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and enhancing the activity of antioxidant enzymes like Super Oxide Dismutase (SOD). However, despite these promising pharmacological actions, CU’s poor systemic bioavailability remains a significant barrier to its clinical application. Nanoparticle-based delivery systems have emerged as a promising solution to improve its stability and absorption.

This review offers an updated perspective by integrating CU’s anti-tumor mechanisms with recent advancements in nanotechnology-based delivery approaches for HCC. Unlike earlier studies, it emphasizes the role of novel nanocarriers-such as Liposomes (LP), Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLNs), Nanostructured Lipid Carriers (NLCs) and Resealed Erythrocytes (RE)-in enhancing CU’s bioavailability and tumor-targeting capabilities. These advanced delivery systems improve cellular uptake, extend circulation time and enhance therapeutic efficacy by addressing the pharmacokinetic limitations of CU. The review provides a comprehensive foundation for the translation of nanotechnology-enabled CU therapies into clinical applications for HCC.

CU represents a versatile therapeutic candidate for HCC, modulating tumor development and progression through multiple molecular pathways. Enhancing its bioavailability via advanced nanocarrier systems is essential to fully realize its clinical potential and therapeutic effectiveness.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Curcumin, Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics, Cancer, Tumor

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i4.53730 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Hepato Cellular Carcinoma (HCC) accounts for over 90% of all liver cancers, making it the most prevalent type of primary liver cancer [1]. It is one of the main causes of cancer-related death and a serious worldwide health issue. 830,000 deaths globally were attributed to HCC in 2020, accounting for 8.3% of all cancer-related fatalities. It is especially aggressive and after lung cancer, it is the second most common reason for cancer-related death in men. HCC still has a low five-year survival rate of about 18%, despite improvements in diagnosis and treatment.

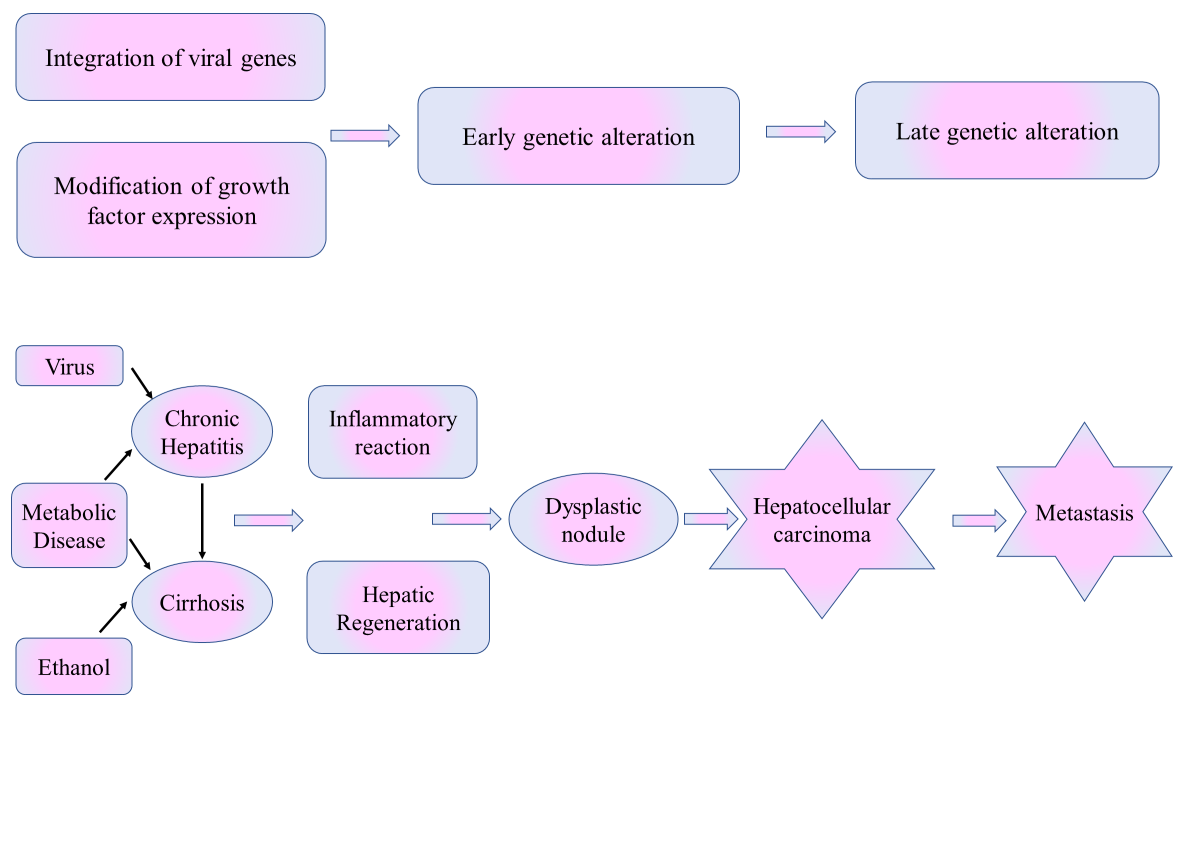

HCC typically develops as a multistep process, beginning with chronic liver injury and inflammation, which progresses to fibrosis, cirrhosis and ultimately malignant transformation. The major risk factor for HCC is cirrhosis, with approximately 80–90% of HCC cases occurring in cirrhotic livers [2]. Chronic viral hepatitis infections [Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) and Hepatitis C Virus (HCV)] are the predominant causes, accounting for about 50% and 25% of HCC cases, respectively. Other significant risk factors include chronic alcohol consumption, Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) and Non-Alcoholic Steato Hepatitis (NASH), both of which are rising concerns due to increasing global obesity and diabetes rates [3]. In patients with cirrhosis, HCC develops through a gradual hepatic carcinogenesis sequence, where regenerative nodules transition into dysplastic nodules and eventually into malignant tumors. Although HCC primarily arises in cirrhotic livers, it can also develop in non-cirrhotic patients, particularly those with HBV infection [4-7].

Treatment for HCC nowadays is based on liver function and disease stage. Treatment options for early-stage HCC include liver transplantation, local ablative treatments and surgical resection. While severe HCC usually necessitates systemic medications, such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors (sorafenib, lenvatinib) and immunotherapy (atezolizumab and bevacizumab), intermediate-stage cancer is frequently treated with Trans Arterial Chemo Embolization (TACE) or Trans Arterial Radio Embolization (TARE). Drug resistance, high recurrence rates and late-stage diagnosis make HCC challenging to treat even with these treatment choices [8].

Alternative therapy approaches that can enhance current treatments and enhance patient outcomes are becoming more popular in due to these difficulties. CU, a polyphenolic compound derived from Curcuma longa, has shown promise as a potential adjunct therapy for HCC due to its anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and anti-cancer properties [9]. According to reports, it regulates key oncogenic pathways that are linked to tumor growth, angiogenesis and metastasis, including Wingless Integration site1/β-Catenin (Wnt/β-catenin), Protein Kinase B (PI3K/Akt), Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) and Nuclear Factor Kappa B (NF-κB). CU is an excellent option for the therapy of HCC since it also causes apoptosis, cell cycle arrest and tumor suppressor activation. Its therapeutic use has been limited by its low bioavailability, rapid metabolism, and restricted systemic absorption [10].

Nanotechnology-based approaches to drug delivery have been developed to improve CU's stability, solubility and targeted distribution to tumors to get around these pharmacokinetic difficulties [11]. In preclinical and clinical research, novel formulations such Liposomes (LP), Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLNs), Nanostructured Lipid Carriers (NLCs) and Resealed Erythrocytes (RE) have shown promise in enhancing CU's bioavailability and therapeutic efficiency. Focusing on its molecular mechanisms of action and the recent developments in nanotechnology-driven delivery techniques to optimise its clinical impact, this review emphasises the therapeutic promise of CU in HCC. Table 1 provides an overview of all the current Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved medicines for HCC.

The literature for this review was collected from major scientific databases, including PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science. The search was conducted using key terms such as "HCC," "CU," "nanotechnology-based drug delivery," "nanocarriers" and "CU pharmacokinetics." Studies published between 2000 and 2024 were considered, with a particular focus on recent advancements in nanocarrier-based CU delivery systems. Inclusion criteria encompassed preclinical studies, clinical trials and comprehensive reviews discussing CU’s mechanisms of action and therapeutic potential in HCC.

Table 1: FDA-approved treatment for HCC

| Drug name | Brand name | Company name | Treatment | Side effects |

| Atezolizumab | Tecentriq | Roche | Alveolar soft part sarcoma, HCC, Non-small cell lung cancer | Hyperglycemia, Hyponatremia, Hyperkalemia, Hypermagnesemia, Hypophosphatemia, Pneumonia, urinary tract infection, Anemia, Thrombocytopenia and Lymphopenia. |

| Bevacizumab | Alymsys, Avastin Mvasi, Zirabev |

Roche | Cervical cancer, colorectal cancer, Glioblastoma, HCC, Non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer | High blood pressure, Too much protein in the urine, Irregular breathing and Irregular heartbeat. |

| Cabozantinib-S-Malate | Cabometyx Cometriq |

Exelixis, Inc | Differentiated thyroid cancer, HCC, Medullary thyroid cancer, Renal cell carcinoma | Diarrhea, Redness, Swelling or pain in your mouth or throat, Weight loss, Decreased Appetite and Nausea. |

| Ramucirumab | Cyramza | Eli Lilly and Company | Colorectal cancer, HCC, Non-small cell lung cancer, Stomach adenocarcinoma | Allergic reactions like skin rash, itching or hives, Breathing problems, Swelling of the face, lips, or tongue, chest pain, chest tightness and Confusion. |

| Durvalumab | Imfinzi | Medimmune/AstraZeneca | Biliary tract cancer, Endometrial cancer, HCC, Non-small cell lung cancer, Small cell lung cancer | Cough, feeling tired, Inflammation in the lungs and Upper respiratory tract infections. |

| Pembrolizumab | Keytruda | Merck and Co | Breast cancer, Biliary tract cancer, Cervical cancer, Classic, Esophageal, Gastric (stomach) cancer, HCC, Non-small cell lung cancer | Rash, tingling or numbness of the arms or legs, feeling tired, itching, diarrhoea, hair loss, weight loss, decreased appetite, dry eye, nausea and constipation. |

| Lenvatinib Mesylate | Lenvima | Eisai Co. | Endometrial carcinoma, HCC, Renal cell carcinoma, Thyroid cancer | Bladder pain, bleeding gums, coughing up blood, decreased frequency or amount of urine, depressed mood, diarrhea and difficulty with breathing. |

| Pembrolizumab | Keytruda | Merck Sharp and Dohme LLC | Biliary tract cancer, Breast cancer, Cervical cancer, Hodgkin lymphoma, HCC, Gastric (stomach) cancer | Nausea, Breathlessness, Low levels of thyroid hormones, Loss of appetite, Diarrhoea or constipation and high blood pressure. |

| Sorafenib Tosylate | Nexavar | Bayer HealthCare and Onyx Pharmaceuticals | HCC, Renal cell, Thyroid cancer | Difficulty with breathing or swallowing, dizziness, headache and increased vaginal bleeding. |

Pathophysiology of HCC

The development of HCC is driven by multiple factors, including the degree of underlying chronic liver disease, genetic predisposition, immune cells and the interplay between viral and non-viral risk factors. The tumor microenvironment plays a crucial role throughout malignant progression, from early transformation to metastasis. Fig. 1 outlines the molecular and cellular events leading to HCC, including genetic alterations, chronic inflammation and cirrhosis. Understanding these pathways is essential for identifying therapeutic targets and improving HCC management.

Fig. 1: Pathophysiology of HCC

Genetic and molecular alterations in HCC

The pathogenesis of HCC involves genetic mutations and molecular alterations, including TERT promoter mutations that activate telomerase, enabling uncontrolled cell division [12, 13]. The Tomerase Reverse Transcriptase (TERT) promoter mutation is a prevalent genetic alteration found in approximately 60% of HCC cases. This mutation plays a key role in helping cancer cells evade normal aging by maintaining telomere length, which promotes continuous and uncontrolled cell growth. It also enhances telomerase activity, disrupts genomic stability and frequently interacts with other cancer-related pathways like Wnt/β-catenin and PI3K-AKT. In HBV-related HCC, viral integration can further trigger TERT activation, accelerating tumor formation. Due to its significant contribution to HCC progression, telomerase-targeting therapies are being investigated as potential treatment options. Mutations in tumor suppressor genes like Tumor Protein p53 (TP53), RetinoBlastoma 1 (RB1) and Phosphatase and TENsin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN) impair cell cycle regulation, while oncogene amplifications (e. g., Cyclin D1 (CCND1), Fibroblast Growth Factor 19 (FGF19) and Melocytomatosis oncogene (MYC) promote cell growth and metabolism. These alterations, often exacerbated by viral infections, lead to genomic instability and malignant transformation. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) reveals actionable mutations in 20–25% of cases, offering potential for targeted therapies despite limited availability [14–16].

Beyond these well-characterized mutations, emerging molecular targets are gaining interest for therapeutic intervention [17]. Recent studies have identified mutations in Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2-Like 2 (NFE2L2) (involved in oxidative stress response), AT-Rich Interactive Domain-containing protein 1A (ARID1A) (chromatin remodeling) and Kelch-like ECH-Associated Protein 1 (KEAP1) (cellular detoxification), which may provide novel avenues for drug development. NGS has revealed potentially actionable mutations in 20–25% of HCC cases, supporting the growing field of targeted therapy despite current limitations in clinical application.

Role of viral infections in HCC development

Chronic viral infections, particularly HBV and HCV, significantly contribute to HCC development [18, 19]. HBV induces TERT promoter mutations, activating telomerase and extending cell lifespan, alongside oncogenic insertions in genes like Cyclin A2 (CCNA2) and Cyclin E1 (CCNE1), causing genomic instability [20, 21]. HCV, by contrast, promotes carcinogenesis through chronic inflammation and oxidative stress, generating Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) that cause Deoxyribo Nucleic acid (DNA) damage and genetic alterations [22]. These mechanisms disrupt cellular homeostasis, creating an environment conducive to tumor growth and progression.

Tumor microenvironment and immune system involvement

The Tumor Micro Environment (TME) is critical in HCC progression, with chronic liver diseases like HBV, HCV, alcohol damage and NAFLD/NASH inducing inflammation that promotes malignancy. Immune cells in the TME, such as Cluster of Differentiation 8 (CD8), T lymphocytes (T cells), macrophages and lymphocytes, release pro-tumorigenic cytokines [23, 24]. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) suppress CD8+T cell activity [24, 25], while Tumor-Associated Macrophages (TAMs) and Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells (MDSCs) secrete InterLeukin-6 (IL-6), Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha (TNF-α) and Transforming Growth Factor-Beta (TGF-β), driving tumor growth, angiogenesis and metastasis [26]. Immune-active HCC tumors respond well to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors (ICIs), whereas immune-excluded tumors, influenced by TGF-β and Wnt signaling, resist ICIs. Understanding HCC's immune landscape is essential for improving immunotherapy [27, 28].

Cirrhosis and fibrogenesis in HCC pathogenesis

Chronic liver injury from HBV, HCV and NASH often leads to cirrhosis, marked by liver scarring and Extracellular Matrix (ECM) accumulation, which promotes tumorigenesis [29, 30]. Fibrogenesis causes liver stiffness, altered vasculature, and disrupted function, creating a scaffold for tumor growth [31]. Senescent hepatocytes in cirrhosis secrete cytokines and growth factors, fostering a pro-tumorigenic environment. Gene signatures from cirrhotic tissue serve as biomarkers for HCC risk and prognosis [32]. The fibrotic microenvironment also attracts immune cells, releasing cytokines that drive further damage and carcinogenesis, establishing cirrhosis as a major risk factor for HCC [33].

Molecular subtypes and prognostic implications

HCC can be classified into molecular subtypes that reveal genetic profiles and clinical behaviours. The proliferation class, linked to poor prognosis and HBV-related HCC, involves Tumor p53 mutations, FGF19 amplifications and active PI3K-AKT and Rat Sarcoma (RAS)-MAPK pathways. It includes two subgroups: one with progenitor markers and proliferative pathways and another driven by Wnt–TGFβ signalling [23, 24]. The non-proliferation class, often associated with HCV and alcohol-related HCC, has a better prognosis and features mutations in Wnt signaling (e.g., Catenin Beta 1(CTNNB1)), activating β-catenin. Immune-active tumors respond well to ICIs, while immune-excluded tumors, driven by TGF-β and Wnt signaling, resist ICIs [32]. These classifications enhance understanding of HCC biology and inform personalized therapies [24, 25].

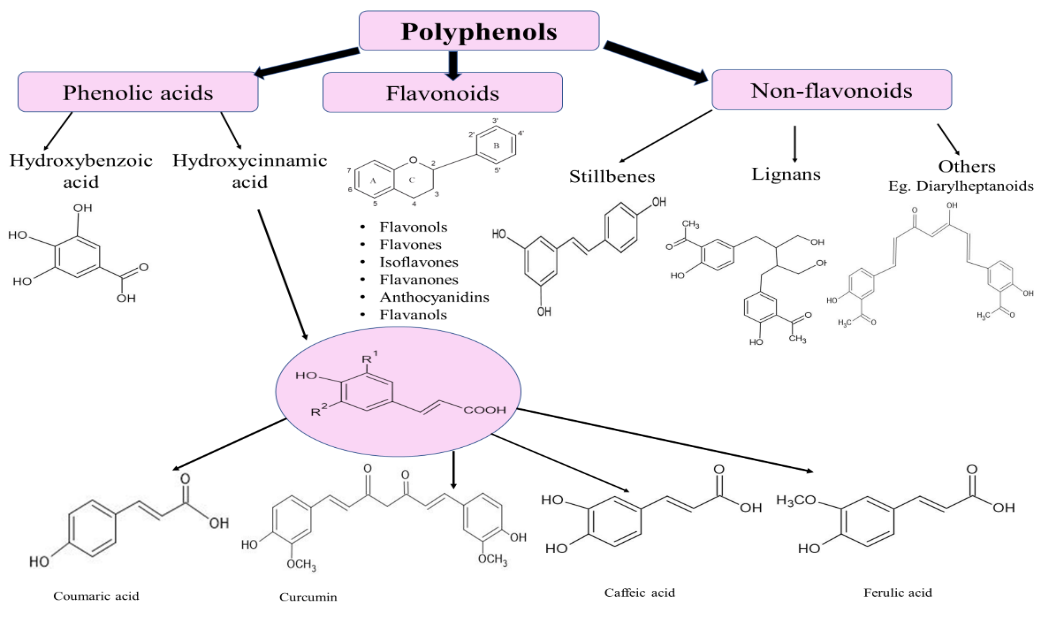

Polyphenolic compounds in HCC

Polyphenols, the most prevalent class of phytocompounds found in plants and accessible to humans through diet, include both flavonoids and non-flavonoids. Numerous biological activities of polyphenolic compounds have been reported, including anti-inflammatory, anti-allergic, anti-mutagenic, anti-carcinogenic and antiproliferative properties [34–37]. Additionally, through a variety of mechanisms, including cell cycle modification, antiproliferation, apoptosis, autophagy and manipulation of different cell signaling pathways, they display chemotherapeutic actions [38]. Previous research has revealed that polyphenolic substances can prevent tumor growth, including genistein, quercetin, resveratrol, CU, apigenin, luteolin, casticin, chrysin and 8-bromo-7-methoxychrysin, as well as their synthetic equivalents [39, 40]. The proliferation of tumor stem cells is inhibited by quercetin, resveratrol, CU, chrysin, casticin and 8-bromo-7-methoxychrysin [41]. Fig. 2 highlights the diverse classes of polyphenolic compounds, which play a crucial role in therapeutic applications due to their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anticancer properties. The classification aids in exploring their mechanisms of action and potential in disease prevention and treatment.

CU

The primary naturally occurring polyphenol present in the rhizome of Curcuma longa (turmeric) and other Curcuma spp. is CU (1,7-bis(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,6-heptadiene-3,5-dione), also known as diferuloylmethane [42]. Curcuma species, is known for its anti-inflammatory [43], anti-mutagenic [44], antibacterial [45, 46], antioxidant [47] and anticancer properties [48]. Despite its safety and efficacy, CU has poor pharmacokinetics, low water solubility and chemical instability [49, 50]. Its low oral bioavailability is attributed to poor intestinal absorption, extensive liver metabolism and gallbladder excretion [51]. Additionally, CU's interaction with enterocyte proteins can further reduce its bioavailability, limiting its therapeutic potential [52].

Pharmacokinetics and metabolism

Pharmacokinetics and metabolism in rodents

Over the past three decades, at least ten studies have examined the distribution, metabolism, excretion and absorption of CU in rodents, consistently showing its rapid metabolism, which reduces the parent compound's bioavailability. Early research reported that 75% of CU-related species were excreted in faces, with minimal amounts in urine after a dietary dose of 1 g/kg in rats [49]. Another study showed a 60% absorption rate of oral CU, with urinary species identified as glucuronide and sulfate conjugates [50]. Using ³H-radiolabeled CU, two-thirds of the oral dose was excreted intact, primarily in faces [51]. Rats given IV or intraperitoneal CU exhibited high levels of CU and its metabolites, tetrahydrocurcumin and hexahydrocurcumin glucuronides, in bile [52]. About half the IV dose was eliminated via bile within five hours, indicating biotransformation during intestinal absorption and enterohepatic recirculation [52]. In mice, intraperitoneal administration of CU (0.1 g/kg) led to metabolic reduction, producing dihydrocurcumin and tetrahydrocurcumin, which were converted into monoglucuronide conjugates [53]. Rats given oral CU exhibited significant levels of CU glucuronide and sulfate in plasma, with negligible amounts of CU itself; minor metabolites included hexahydrocurcumin, hexahydrocurcuminol and hexahydrocurcumin glucuronide (fig. 3) [54]. CU was rapidly metabolized in human hepatocyte suspensions and microsomes from rat and human liver or gut tissues, as illustrated in fig. 3 [55] fig. highlights the primary CU metabolites observed in both animal models and human studies. It is essential for evaluating CU's pharmacokinetics, bioavailability and therapeutic efficacy, as it provides insights to optimize delivery systems and improve clinical outcomes.

Fig. 2: Classification of polyphenolic compounds

Fig. 3: Key metabolites of CU identified in both rodents and humans

Clinical pharmacokinetics and metabolism

Comprehensive human pharmacokinetic data for CU remain limited compared to preclinical studies. In healthy participants, consuming 2 g of CU resulted in plasma levels below 10 ng/ml within a hour, but co-administration with 20 mg piperine increased bioavailability by 2000% [56]. Trials administering 0.5–8 g/d of CU for three months to patients with high-risk premalignant conditions showed peak serum levels of 1.75±0.80 μM after an 8 g dose [57]. In another study, oral doses of 50–200 mg micronized CU failed to achieve detectable plasma levels [58]. In colorectal cancer patients, doses up to 180 mg/d over four months showed no systemic bioavailability [59]. A follow-up study with 0.45–3.6 g/d found CU and its conjugates in plasma near detection limits, with urinary metabolites suggesting compliance [60]. Tissue studies revealed CU in colorectal tissue (12.7 and 7.7 nmol/g in malignant and normal tissue, respectively) after 3.6 g/d for seven days, but with low levels in the blood and undetectable amounts in the liver [61]. These findings indicate limited systemic distribution and suggest achieving pharmacologically active hepatic levels with oral doses may be impractical.

Pharmacodynamic action of CU in HCC

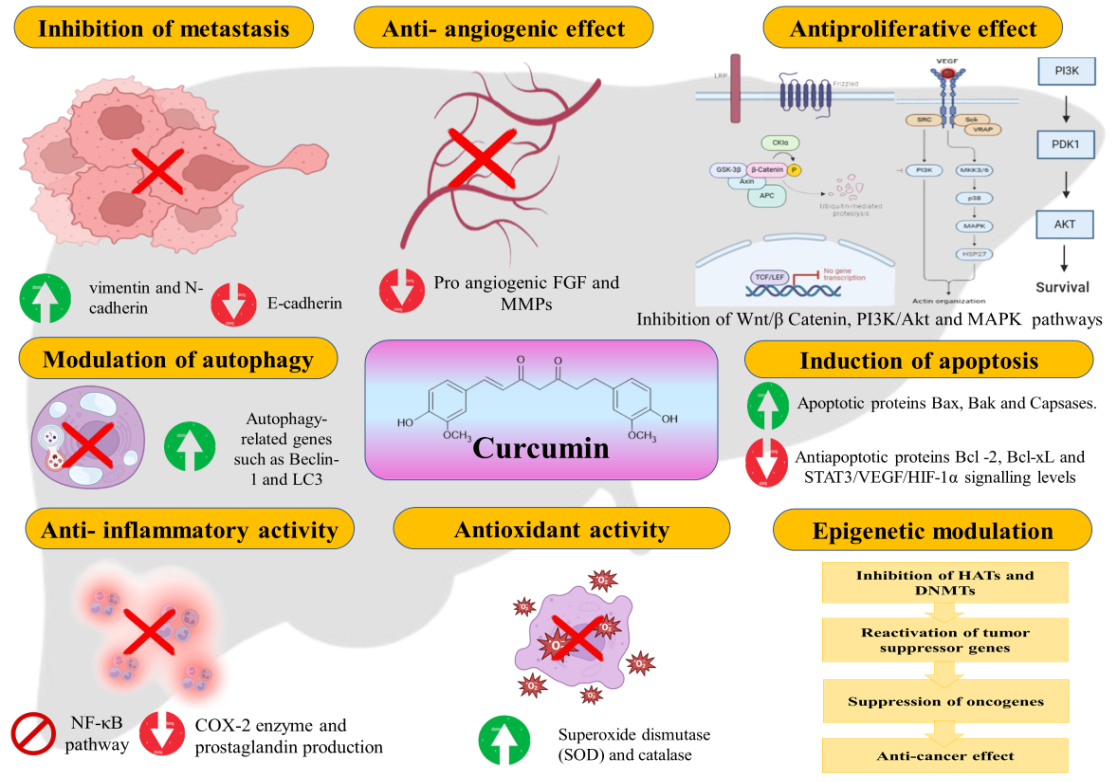

Anti-proliferative effect

CU inhibits tumor cell proliferation by targeting key signaling pathways, including Wnt/β-catenin, PI3K/Akt and MAPK, which are critical for cell growth and survival and often dysregulated in cancer. It also impacts the cell cycle by downregulating cyclins and Cyclin-Dependent Kinases (CDKs) while upregulating inhibitors like protein 21 and protein 27. These inhibitors inactivate CDKs, arresting the cell cycle at the Gap 1 phase to S phase transition and preventing DNA replication. Through these mechanisms, CU effectively curtails tumor growth and progression, highlighting its therapeutic potential [62–64].

Induction of apoptosis

CU demonstrates potent anti-cancer effects in HCC by targeting multiple pathways. It suppresses the Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 (STAT3)/Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF)/Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1-Alpha (HIF-1α) signaling pathway, crucial for tumor survival and angiogenesis, thereby reducing tumor viability and inhibiting blood vessel formation essential for growth [65]. CU also enhances pro-apoptotic proteins like Bcl-2–Associated X protein (Bax), Bcl-2 homologous Antagonist/Killer (Bak) and caspases while reducing anti-apoptotic proteins such as Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL, shifting the balance towards apoptosis. Additionally, it activates the tumor suppressor gene p53, promoting cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in response to cellular stress [66]. CU further engages the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway, disrupting mitochondrial membrane potential and triggering cytochrome c release, which activates caspase-3 and other apoptotic effectors. These combined actions effectively inhibit tumor proliferation and survival, underscoring CU's therapeutic potential in managing HCC [67].

Anti-angiogenic effect

CU inhibits angiogenesis in HCC by downregulating VEGF and its receptor, key regulators of new blood vessel formation. It also suppresses pro-angiogenic factors like FGF and modulates Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMP-2 and MMP-9), which aid in endothelial cell migration and invasion. By limiting these angiogenic mediators, CU reduces tumor vascularization, restricting the oxygen and nutrient supply necessary for tumor growth and metastasis. This multifaceted mechanism highlights CU's potential as a therapeutic agent in controlling HCC progression [68, 69].

Anti-inflammatory activity

CU exhibits potent anti-inflammatory effects, making it a promising agent for inflammation-associated HCC. It inhibits the NF-κB pathway, reducing pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β, which foster a tumor-promoting microenvironment [70]. CU also downregulates Cyclo OXygenase-2 (COX-2), lowering prostaglandin production and further reducing inflammation. By targeting these pathways, CU disrupts chronic inflammation, preventing HCC initiation and progression, underscoring its therapeutic potential [71].

Inhibition of metastasis

CU plays a key role in reducing HCC metastasis by modulating the Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT), a crucial process in cancer progression [72]. EMT involves the transformation of stationary epithelial cells into invasive mesenchymal cells. CU downregulates mesenchymal markers, such as vimentin and N-cadherin, while upregulating epithelial markers like Epithelial Cadherin (E-cadherin), thereby maintaining cell adhesion and limiting cell detachment and spread [73]. It also inhibits MMPs, enzymes that degrade the extracellular matrix and promote cancer invasion. By suppressing EMT and MMP activity, CU effectively reduces HCC metastasis, highlighting its potential as an anti-metastatic agent [74].

Antioxidant activity

CU is a potent antioxidant that plays a crucial role in combating oxidative stress in HCC cells. ROS are highly reactive molecules that can cause significant cellular damage, contributing to carcinogenesis and tumor progression. CU scavenges free radicals, preventing oxidative damage to cellular components. Additionally, it enhances the body’s antioxidant defence by upregulating enzymes like like Super Oxide Dismutase (SOD) and catalase, which neutralize ROS. SOD converts superoxide radicals into hydrogen peroxide, which catalase then breaks down into water and oxygen. Through this dual mechanism, CU protects against oxidative damage, a major factor in HCC initiation and development, highlighting its potential as both a preventive and therapeutic agent in liver carcinogenesis [75, 76].

Modulation of autophagy

CU has a dual role in autophagy regulation in HCC cells, with effects depending on the cellular context. It can promote autophagic cell death by upregulating autophagy-related genes like Beclin-1 and Microtubule-associated protein 1 light Chain 3 (LC3), aiding in the elimination of damaged cells and suppressing tumor growth [77]. Alternatively, CU can inhibit protective autophagy, sensitizing HCC cells to apoptosis and enhancing cancer treatment efficacy. This dual regulation of autophagy underscores CU's potential as both an autophagy promoter and inhibitor, depending on the tumor microenvironment and signaling pathways [78].

Epigenetic modulation

CU affects epigenetic regulation in HCC by inhibiting Histone Acetyl Transferases (HATs) and DNA Methyl Transferases (DNMTs). By inhibiting HATs, CU suppresses oncogenes and by blocking DNMTs, it reactivates tumor suppressor genes. These epigenetic changes restore natural growth control, reducing cancer cell growth and metastasis and enhancing CU's anti-cancer effects in HCC [79, 80]. Fig. 4 illustrates the multiple mechanisms by which CU exerts anti-cancer effects in HCC, including the inhibition of proliferative signaling pathways, induction of apoptosis, suppression of angiogenesis and reduction of inflammation and oxidative stress. These mechanisms is crucial for developing CU-based therapies and improving treatment outcomes in HCC.

CU delivery systems for HCC

LP

LP are spherical, bi-vesicular Drug Delivery Systems (DDSs) made of cholesterol and phospholipids that can encompass both hydrophilic and lipophilic drugs. The system's encapsulation efficiency for hydrophilic moieties increases with the number of bilayers. These LP have several benefits, including improved bioavailability, enhanced solubility and the utilization of hydrophilic and hydrophobic moieties [82].

Yan Wang et al. formulated conventional LPs, Galactose-modified LP (Gal-LPs) and Galactose-Morpholine-modified LP loaded with CU (Gal-Mor-LPs) for Intravenous (IV) administration by thin film method followed by ultrasonication method using soy phosphatidylcholine and cholesterol. Kunming mice were subcutaneously injected with 2.0 × 106 Hepatoma-22 (H22) cells at the right forelimb axilla in order to prepare the tumor-bearing mouse models. Using a tail vein, 5 mg/kg of CU-loaded LP (LPs, Gal-LPs and Gal-Mor-LPs) were injected into the mice. A trend of LPs<Gal-LPs ASialo Glyco PRotein receptor (ASGPR)<Gal-Mor-LPs (galactose group recognised ASGPR and morpholine group targeted to lysosome) was observed in the LPs' ability to target hepatoma cells both in vitro and in vivo. Gal-Mor-LPs showed superior lysosomal targeting effectiveness in comparison to LPs and Gal-LPs. The order of free CU<LPs<Gal-LPs<Gal-Mor-LPs was observed in the IV administration of the formulations. The CU-loaded LPs modified with galactose and morpholine groups also showed great biosafety, according to in vitro and in vivo toxicity studies [83]. Greil et al. conducted a phase I trial to examine the physiological effects of liposomal CU (Lipocurc TM) administered to patients with advanced cancer. CU levels in the blood remained constant during a 6–8 hour IV infusion (100–300 mg/m2), but they decreased to undetectable levels 10 min after the infusion was stopped [84].

SLN

SLNs are hydrophobic core-dispersed colloidal nanoparticles made of lipids and surfactants in which the drug is dissolved. Because of the issues with inadequate drug loading and carrier explosion, SLNs are not employed frequently. Wei et al., formulated CU SLN by improved thin-film ultrasonic dispersion method using Hydrogenated Soy Phosphatidyl Choline (HSPC) and 1,2-Distearoyl-Sn-glycero-3-Phospho Ethanolamine-N-[methoxy(Poly Ethylene Glycerol)-2000 (DSPE-PEG2000) as a lipid. Using flow cytometry, the cell apoptosis assay of CU SLN was assessed. The findings indicated that CU SLN considerably exhibited a stronger apoptosis-inducing effect on Metastatic HCC (MHCC-97H) cells. The in vitro drug release, entrapment, zeta potential and particle size were 80.93 %,94.98 %,-36.30 mV and 122.10 nm [85].

Fig. 4: Mechanisms of CU in HCC [81]

NLCs

New-generation nanoparticles known as NLCs are made of lipids, surfactants and co-surfactants. They have the ability to load lipophilic and hydrophilic medicines in either liquid or solid form and they also provide controlled and targeted drug release. NLCs production further demonstrated enhanced drug permeability from the matrix and superior storage stability [82, 86]. CU-laden NLCs (CU-NLCs) for HCC were prepared by using emulsion-evaporation and low-temperature solidification techniques. The mean particle diameter was 99.99 nm with a Poly Dispersible Index (PDI) of 0.158, zeta potential of −19.9 mV and entrapment efficiency of 97.86 %. In vitro, C-NLCs induced significant apoptosis in HepG2 cells, primarily through the activation of the Death Receptor 5 (DR5)/caspase-8 mediated extrinsic apoptosis pathway. Flow cytometry analysis demonstrated an increase in apoptotic cell populations, while Western blotting confirmed the upregulation of DR5 and cleaved caspase-8. These findings suggest that C-NLC scan be a potential therapeutic strategy for targeting cancer cells through the extrinsic apoptosis pathway [87].

Chu et al., formulated Glycyrrhizin Acid-Modified CU-Loaded NLCs (CU-GA-PEG-NLC) by film ultrasound method technique using Glycerol monostearate or Miglyol 812N and lecithin as a lipid and 10 mg of CU. The different Cur-GA-PEG-NLC samples had encapsulation efficiencies ranging from 90.06% to 95.31% and particle sizes between 123.1 and 132.7 nm. Cur-GA10%-PEG-NLC demonstrated notably higher cellular uptake and cytotoxicity against human HEPatoma cell line (HepG2) cells in comparison to other groups, as demonstrated by an in vitro 3-(4,5-di Methyl Thiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl Tetrazolium bromide (MTT) experiment. The results of the cytotoxicity test indicated that the formulation’s and the free drug's rates of inhibition of HepG2 cell proliferation were concentration-and time-dependent. Cell growth inhibition rates increase with longer incubation periods and higher drug concentrations. The cytotoxicity of the Cur-GA10%-PEG-NLC group was significantly higher than that of the Cur-solution group at all time periods and higher than that of the Cur-NLC group at 24, 48 h [88].

Nanoemulsion (NE)

NEs are kinetically stable colloidal systems of water, oil and emulsifiers that improve drug effectiveness and bioavailability. Guo et al. developed an oral NE (CU/FU-NE) for the co-delivery of CU and 5-FluoroUracil (FU) to treat liver cancer using the emulsification method. In HepG2-induced HCC, CU/FU-NE significantly enhanced the oral bioavailability and intracellular concentrations of CU and FU compared to free CU, FU, or their combination. CU/FU-NE promoted tumor apoptosis, inhibited HepG2 cell growth and improved the safety of CU+FU combination chemotherapy, demonstrating its potential as a novel, effective and safe treatment for liver cancer [89].

RE

Red Blood Cells (RBCs), or erythrocytes, are abundant in the bloodstream and offer prolonged circulation and high biocompatibility with minimal immunogenicity. Their membranes RBC Membrane (RBCM) have become a promising tool for DDSs, particularly for encapsulating nanoparticles to enhance therapeutic efficacy. The Cluster of Differentiation 47 (CD47) protein on RBCM modulates macrophage uptake by binding to CD47 receptors, enabling RBCM-coated materials to evade phagocytosis and remain in systemic circulation longer, making them efficient drug carriers [90, 91]. The study on erythrocyte membrane-cloaked, CU-loaded nanoparticles developed a novel formulation targeting HCC. Encapsulating CU within nanoparticles cloaked with erythrocyte membranes addressed CU's low bioavailability and rapid degradation. This approach improved stability, circulation time, immune evasion and tumor accumulation. The results showed significant enhancements in CU's bioavailability and cytotoxicity against HCC cells, demonstrating this nanoparticle system's potential as a more effective, biocompatible chemotherapy strategy. This innovative formulation highlights nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems' potential to enhance natural compounds' therapeutic efficacy, like CU, for liver cancer treatment [92].

Other nanoparticles

CU-loaded Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles (CUR-MSNs) were developed to enhance CU's cytotoxicity in HCC cells. Silica-Encapsulated (SCNP) and Chitosan-Silica Co-encapsulated (CSCNP) CU nanoparticles were synthesized via silicification methods. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) revealed spherical particles with sizes of 61.7±23.04 nm (SCNP) and 75.0±14.62 nm (CSCNP). CSCNP showed superior antioxidant activity and cytotoxicity, especially against HepG2 cells, with improved stability and antitumor efficacy, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic option for HCC [93]. Darwesh et al. developed CU-capped iron oxide nanoparticles (IONs@CU), averaging 12 nm in size, with a zeta potential of –33±2.2 mV, ensuring stability and effective cellular delivery. IONs@CU exhibited enhanced cytotoxicity and antioxidant capacity compared to free CU, with increased CU accumulation in HepG2 cells. The formulation upregulated SOD2 and TP53 expression and induced autophagy, as confirmed by immunofluorescence staining of AuTophagy-related Gene 4 (ATG-4), demonstrating improved therapeutic potential against HCC [94].

Table 2: Nanocarrier systems their advantages, limitations and therapeutic uses

| Nanocarrier type | Advantages | Limitations | Therapeutic outcomes |

| LP’s | Enhances drug solubility and bioavailability | Prone to leakage and stability issues | Improved targeted delivery and reduced toxicity |

| SLN’s | High drug loading capacity, biocompatibility | Limited drug encapsulation efficiency | Improved stability and sustained drug delivery |

| NLC’s | Enhanced drug loading and controlled release | Formulation complexity | Superior bioavailability and reduced systemic side effects |

| NE’s | High drug solubility, ease of preparation | Physical instability (e. g., phase separation) | Enhanced drug absorption and improved bioavailability |

| RE’s | Biocompatible, low immunogenicity | Labor-intensive preparation | Prolonged circulation and targeted drug delivery |

| MSN’s | High surface area for drug loading | Potential toxicity and biodegradability concerns | Improved drug loading, controlled release, and targeted delivery |

Although nanocarrier technology has advanced significantly, several of obstacles still stand in the way of its therapeutic application:

Manufacturing difficulties: One major difficulty is growing the manufacturing of nanocarriers while preserving consistent particle size, stability and reproducibility. Maintaining clinical efficacy and meeting regulatory requirements require batch-to-batch consistency [95].

Regulatory obstacles: Proving the safety, effectiveness and biocompatibility of nanocarriers is necessary to comply with regulatory frameworks. The need for extensive preclinical and clinical trials increases the time and expense required for market approval.

Stability and storage: Nanocarriers frequently struggle to remain stable while being transported and stored. Over time, physical or chemical deterioration may reduce their therapeutic efficacy, requiring sophisticated formulation techniques [96].

Cost and accessibility: Patients are unable to obtain nanocarriers due to the high expenses associated with the intricate design and manufacturing procedures. For increased clinical usage, scalable and economical production methods must be developed [97].

Clinical translation: Several factors, including patient variability, immunogenic responses and the complex nature of HCC, make it difficult to translate preclinical discoveries into clinical applications. Adaptive clinical trial designs and thorough research are needed to address these problems.

Overcoming these barriers through innovative manufacturing approaches, streamlined regulatory processes, and continued research efforts is vital to unlock the full therapeutic potential of nanocarrier-based treatments for HCC [98].

Challenges in achieving consistent plasma levels of CU

Poor water solubility and rapid metabolism and clearance

CU is highly hydrophobic, which limits its dissolution in aqueous environments like blood plasma. This poor solubility reduces its absorption in the gastrointestinal tract, leading to low systemic availability [99]. Nanocarriers improve solubility, but achieving a uniform and sustained release remains a challenge. Once absorbed, CU undergoes extensive first-pass metabolism in the liver and intestines. It is rapidly converted into inactive glucuronide and sulfate conjugates, which are quickly excreted through bile and urine. This fast metabolic breakdown leads to a short plasma half-life, making it difficult to maintain therapeutic drug levels over time [100].

Efflux by transporters and chemical instability

Efflux transporters like Permeability glycoprotein (P-glycoprotein) actively expel CU from intestinal and systemic circulation back into the gastrointestinal tract. This reduces CU's retention and limits its bioavailability. Even advanced delivery systems struggle to prevent this active efflux, impacting sustained drug levels. CU is chemically unstable at physiological pH and degrades into by-products under light, heat, or alkaline conditions. This degradation reduces the effective CU concentration, making it difficult to maintain consistent plasma levels [101].

Patient-specific variability and inconsistent drug encapsulation and release

Individual differences in metabolic enzymes (such as Uridine 5'-Diphospho-glucuronosyltransferase) and transporter expression lead to significant variability in how CU is absorbed, metabolized and cleared. This variability makes it challenging to achieve predictable and consistent plasma concentrations across diverse patient populations [102]. Nanocarrier systems improve CU delivery, but ensuring consistent drug loading and controlled release is technically challenging during large-scale production. Variability in encapsulation efficiency affects the amount of CU released, leading to fluctuations in plasma levels [103].

Short circulation time and regulatory and manufacturing challenges

Although nanocarriers extend CU’s circulation, many delivery systems are rapidly cleared by the Mononuclear Phagocyte System (MPS) or are taken up by the liver and spleen [104]. This rapid clearance reduces the duration CU remains available in the bloodstream. Scaling up the production of CU-loaded nanocarriers while ensuring consistent quality and pharmacokinetic properties remains a complex challenge. Differences in manufacturing conditions can affect particle size, drug loading and stability, leading to variability in plasma drug levels [105].

Patents of CU for HCC

The patents mentioned in table 3 highlight a range of innovative CU formulations developed to target HCC more effectively. These patents include nanoparticle-based CU delivery systems, such as CU-loaded LPs, polymer-coated nanoparticles and ligand-conjugated particles, all of which aim to enhance CU's bioavailability, stability and targeted delivery to tumor sites. Some patents focus on CU combinations with other chemotherapeutic agents to leverage synergistic effects for improved anti-tumor activity.

Table 3: Patents of CU for HCC

| S. No. | Patent/application number | Patent title | Applicant/Assignee | Key findings | Publication date | Reference |

| 1 | US 2022/0152211 A1 | Hybrid CU Conjugates and Methods of Use Thereof | The US Government as Represented by the Department of Veterans Affairs and Augusta University Research Institute INC | The specific CU conjugate formulation can be used effectively in the treatment of various cancers, including HCC, through targeted administration to inhibit cancer cell growth. | May 19, 2022 | [106] |

| 2 | WO 2023/225578 A2 | Immuno-Ablation Treatment for Solid Tumors | University of North western US | The composition combining ethanol and CU as an anti-cancer immune modulator can be used for ethanol 3ablation to effectively treat solid tumors, including HCC, by reducing tumor volume and enhancing immune response. | Nov 23, 2023 | [107] |

| 3 | CN 108272780 A | Composition inhibiting proliferation of hepatoma carcinoma cells and application of composition | Dalian Yuangu Kangjian Tech Co LTD | Resveratrol and CU work synergistically to significantly inhibit the proliferation of human liver cancer HepG2 cells. | Jul 13, 2018 | [108] |

| 4 | WO 2020/087175 A1 | Phospholipid-Free Small Unilamellar Vesicles (Pfsuvs) for Drug Delivery | British Columbia University | A phospholipid-free small unilamellar vesicle (PFSUV) composition containing a steroid and nonionic surfactant, with the option to include drugs like CU, shows potential for targeted drug delivery and liver disease treatment, including liver cancer. | May 7, 2020 | [109] |

| 5 | WO 2009/144220 A1 | Water Soluble CU Compositions for Use in Anti-Cancer and Anti-Inflammatory Therapy | Bruxelles BE University, Liege BE University, Neven Philippe BE, Serteyn Didier BE, Delarge Jacques, Kiss Robert BE, Mathieu Veronique BE, Cataldo Didier BE and Rocks Natacha BE | A cyclodextrin complex of CU lysine (HP-beta-CD or HP-gamma-CD) enhances water solubility and bioavailability, demonstrating efficacy for treating proliferative and inflammatory disorders, including cancer and chronic inflammatory conditions. | Sep 10, 2020 | [110] |

| 6 | US 2005/0049299 A1 | Selective inhibitors of STAT-3 activation and uses thereof | Aggarwal Bharat B | Administration of a pharmacologically effective dose of curcuminoids, such as CU or its analogues, reduces activated STAT3 expression and shows potential for treating various cancers, including multiple myeloma, head and neck cancer, HCC, lymphomas and leukaemia. | Mar 3, 2005 | [111] |

| 7 | WO 2023/191746 A1 | An Anti-Cancer Formulation Comprising Sodium Pentaborate, CU and Piperine for Use in the Treatment of HCC | Yeditepe University | The formulation combining sodium pentaborate pentahydrate, CU and piperine in specific concentrations is effective for the treatment of liver cancer, including HCC and can be administered orally in various dosage forms. | Oct 5, 2023 | [112] |

CONCLUSION

CU demonstrates significant potential as an adjunctive therapeutic agent in HCC by targeting key signaling pathways involved in tumor growth, invasion and metastasis. Its ability to modulate the cell cycle, induce apoptosis, inhibit angiogenesis and exert anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects establishes a comprehensive anti-cancer profile. Despite these promising attributes, CU's clinical application is limited by poor bioavailability and rapid metabolism. Recent advancements in nanotechnology-based delivery systems, such as erythrocyte membrane-coated nanoparticles, have shown promise in overcoming these challenges by enhancing CU's stability, bioavailability and therapeutic efficacy.

Future research should prioritize the development of scalable and cost-effective nanocarrier systems to facilitate large-scale production and clinical application. Additionally, further investigation through well-designed clinical trials is essential to validate the safety and efficacy of novel CU formulations. Exploring the synergistic potential of CU in combination with existing HCC treatments could offer innovative therapeutic strategies, ultimately improving patient outcomes and advancing the clinical translation of CU-based therapies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We sincerely thank Krishna Vishwa Vidyapeeth’s Krishna Institute of Pharmacy, Karad for providing the resources and support needed to complete this review article.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Ms. Reshma Mate: Literature review, data collection, writing and draft preparation, Dr. Anuradha Chivate: Conceptualization, Data analysis, validation, visualization, writing–review and editing, interpretation of results, Dr. Namdeo Jadhav: Supervision, technical support, validation, Dr. Niranjan Chivate: Supervision, validation

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no conflict of interest related to this review article.

REFERENCES

Coffman D Annibale K, Xie C, Hrones DM, Ghabra S, Greten TF, Monge C. The current landscape of therapies for hepatocellular carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 2023;44(7):537-48. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgad052, PMID 37428789.

Chivate A, Pratibha S, Salve, Rajendra C, Doijad, Avinash M, Mane, Niranjan D, Chivate. Effect of capecitabine resealed erythrocytes on mnu induced hepatocarcinogenesis in swiss albino mice. PCI-Approved-IJPSN. 2022;15(1):5813-21. doi: 10.37285/ijpsn.2022.15.1.9.

Raza A, Sood GK. Hepatocellular carcinoma review: current treatment and evidence-based medicine. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(15):4115-27. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i15.4115, PMID 24764650.

Lee MJ. A review of liver fibrosis and cirrhosis regression. J Pathol Transl Med. 2023;57(4):189-95. doi: 10.4132/jptm.2023.05.24.

Desai A, Sandhu S, Lai JP, Sandhu DS. Hepatocellular carcinoma in non-cirrhotic liver: a comprehensive review. World J Hepatol. 2019;11(1):1-18. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v11.i1.1, PMID 30705715.

Ramakrishna G, Rastogi A, Trehanpati N, Sen B, Khosla R, Sarin SK. From cirrhosis to hepatocellular carcinoma: new molecular insights on inflammation and cellular senescence. Liver Cancer. 2013;2(3-4):367-83. doi: 10.1159/000343852, PMID 24400224.

Stroffolini T, Stroffolini G. A historical overview on the role of hepatitis B and C viruses as aetiological factors for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancers. 2023;15(8):2388. doi: 10.3390/cancers15082388, PMID 37190317.

Chivate AN, Salve PS, Doijad RC, Mane AM, Chivate ND. Acute toxicity study of intravenously administered capecitabine resealed erythrocytes in mice. Res J Pharm Technol. 2022;15(12):5473-7. doi: 10.52711/0974-360X.2022.00923.

Steffi PF, MS. Curcumin a potent anticarcinogenic polyphenol a review. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2014;7(7):1-8.

Asish A, Rajan S, Jose SP, SS, MR, SS. Extracellular modulatory and anti-inflammatory effects of a combination of curcumin piperine and virgin coconut oil in animal model. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2024;17(2):73-9. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2024v17i12.52641.

Kaur J, Bawa P, Rajesh SY, Sharma P, Ghai D, Jyoti J. Formulation of curcumin nanosuspension using box-behnken design and study of impact of drying techniques on its powder characteristics. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2017;10(16):43-51. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2017.v10s4.21335.

Sia D, Villanueva A, Friedman SL, Llovet JM. Liver cancer cell of origin molecular class and effects on patient prognosis. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(4):745-61. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.11.048, PMID 28043904.

Pikarsky E. Neighbourhood deaths cause a switch in cancer subtype. Nature. 2018;562(7725):45-6. doi: 10.1038/d41586-018-06217-3, PMID 30275548.

Schulze K, Imbeaud S, Letouze E, Alexandrov LB, Calderaro J, Rebouissou S. Exome sequencing of hepatocellular carcinomas identifies new mutational signatures and potential therapeutic targets. Nat Genet. 2015;47(5):505-11. doi: 10.1038/ng.3252, PMID 25822088.

Llovet JM, Kelley RK, Villanueva A, Singal AG, Pikarsky E, Roayaie S. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7(1):6. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-00240-3, PMID 33479224.

Hyman DM, Taylor BS, Baselga J. Implementing genome driven oncology. Cell. 2017;168(4):584-99. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.015, PMID 28187282.

Bhutadiya VL, Mistry KN. A review on bioactive phytochemicals and its mechanism on cancer treatment and prevention by targeting multiple cellular signaling pathways. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2021;13(12):15-9. doi: 10.22159/ijpps.2021v13i12.42798.

European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2018;69(1):182-236. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.019, PMID 29628281.

Paterlini Brechot P, Saigo K, Murakami Y, Chami M, Gozuacik D, Mugnier C. Hepatitis B virus related insertional mutagenesis occurs frequently in human liver cancers and recurrently targets human telomerase gene. Oncogene. 2003;22(25):3911-6. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206492, PMID 12813464.

Nault JC, Datta S, Imbeaud S, Franconi A, Mallet M, Couchy G. Recurrent AAV2-related insertional mutagenesis in human hepatocellular carcinomas. Nat Genet. 2015;47(10):1187-93. doi: 10.1038/ng.3389, PMID 26301494.

Bayard Q, Meunier L, Peneau C, Renault V, Shinde J, Nault JC. Cyclin A2/E1 activation defines a hepatocellular carcinoma subclass with a rearrangement signature of replication stress. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):5235. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07552-9, PMID 30531861.

Alexandrov LB, Nik Zainal S, Wedge DC, Aparicio SA, Behjati S, Biankin AV. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature. 2013;500(7463):415-21. doi: 10.1038/nature12477, PMID 23945592.

Zucman Rossi J, Villanueva A, Nault JC, Llovet JM. Genetic landscape and biomarkers of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(5):1226-39.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.05.061, PMID 26099527.

Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Electronic address: wheeler@bcm.edu, cancer genome atlas research network. comprehensive and integrative genomic characterization of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell. 2017;169(7):1327-41.e23. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.046, PMID 28622513.

Lachenmayer A, Alsinet C, Savic R, Cabellos L, Toffanin S, Hoshida Y. Wnt-pathway activation in two molecular classes of hepatocellular carcinoma and experimental modulation by sorafenib. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(18):4997-5007. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2322, PMID 22811581.

Bruno TC. New predictors for immunotherapy responses sharpen our view of the tumour microenvironment. Nature. 2020;577(7791):474-6. doi: 10.1038/d41586-019-03943-0, PMID 31965091.

Ruiz DE Galarreta M, Bresnahan E, Molina Sanchez P, Lindblad KE, Maier B, Sia D. β-catenin activation promotes immune escape and resistance to anti-PD-1 therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2019;9(8):1124-41. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-0074, PMID 31186238.

Sia D, Jiao Y, Martinez Quetglas I, Kuchuk O, Villacorta Martin C, Castro DE Moura M. Identification of an immune-specific class of hepatocellular carcinoma based on molecular features. Gastroenterology. 2017;153(3):812-26. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.06.007, PMID 28624577.

Anstee QM, Reeves HL, Kotsiliti E, Govaere O, Heikenwalder M. From NASH to HCC: current concepts and future challenges. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16(7):411-28. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0145-7, PMID 31028350.

Gomes AL, Teijeiro A, Buren S, Tummala KS, Yilmaz M, Waisman A. Metabolic inflammation-associated IL-17A causes non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2016;30(1):161-75. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.05.020, PMID 27411590.

Tsuchida T, Friedman SL. Mechanisms of hepatic stellate cell activation. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 Jul;14(7):397-411. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.38, PMID 28487545.

Moeini A, Torrecilla S, Tovar V, Montironi C, Andreu Oller C, Peix J. An immune gene expression signature associated with development of human hepatocellular carcinoma identifies mice that respond to chemopreventive agents. Gastroenterology. 2019 Nov;157(5):1383-97.e11. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.07.028, PMID 31344396.

Hoshida Y, Villanueva A, Sangiovanni A, Sole M, Hur C, Andersson KL. Prognostic gene expression signature for patients with hepatitis C-related early-stage cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2013 May;144(5):1024-30. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.01.021, PMID 23333348.

Pietta PG. Flavonoids as antioxidants. J Nat Prod. 2000 Jul;63(7):1035-42. doi: 10.1021/np9904509, PMID 10924197.

Kawai M, Hirano T, Higa S, Arimitsu J, Maruta M, Kuwahara Y. Flavonoids and related compounds as anti-allergic substances. Allergol Int. 2007 Jan;56(2):113-23. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.R-06-135, PMID 17384531.

Serafini M, Peluso I, Raguzzini A. Flavonoids as anti-inflammatory agents. Proc Nutr Soc. 2010 Aug;69(3):273-8. doi: 10.1017/S002966511000162X, PMID 20569521.

Panche AN, Diwan AD, Chandra SR. Flavonoids: an overview. J Nutr Sci. 2016 Dec 29;5:e47. doi: 10.1017/jns.2016.41, PMID 28620474.

Chahar MK, Sharma N, Dobhal MP, Joshi YC. Flavonoids: a versatile source of anticancer drugs. Pharmacogn Rev. 2011;5(9):1-12. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.79093, PMID 22096313.

Sak K. Cytotoxicity of dietary flavonoids on different human cancer types. Pharmacogn Rev. 2014;8(16):122-46. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.134247, PMID 25125885.

Ren W, Qiao Z, Wang H, Zhu L, Zhang L. Flavonoids: promising anticancer agents. Med Res Rev. 2003;23(4):519-34. doi: 10.1002/med.10033, PMID 12710022.

MA T, Fan A, LV C, Cao J, Ren K. Screening flavonoids and their synthetic analogs to target liver cancer stem-like cells. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2018;11(10):10614-22.

Fuloria S, Mehta J, Chandel A, Sekar M, Rani NN, Begum MY. A comprehensive review on the therapeutic potential of Curcuma longa Linn. in relation to its major active constituent curcumin. Front Pharmacol. 2022 Mar 25;13:820806. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.820806, PMID 35401176.

Lestari ML, Indrayanto G. Curcumin. Profiles Drug Subst Excip Relat Methodol. 2014;39:113-204. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800173-8.00003-9, PMID 24794906.

Proenca Assuncao JC, Constantino E, Farias DE França AP, Nogueira FA, Consonni SR, Chaud MV. Mutagenicity of silver nanoparticles synthesized with curcumin (Cur-AgNPs). J Saudi Chem Soc. 2021 Sep;25(9):101321. doi: 10.1016/j.jscs.2021.101321.

Hussain Y, Alam W, Ullah H, Dacrema M, Daglia M, Khan H. Antimicrobial potential of curcumin: therapeutic potential and challenges to clinical applications. Antibiotics (Basel). 2022 Feb 28;11(3):322. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11030322, PMID 35326785.

Hossain S, Islam A, Tasnim F, Hossen F, E-Zahan K, Asraf A. Antimicrobial antioxidant and cytotoxicity study of Cu(II), Zn(II), Ni(II), and Zr(IV) complexes containing O, N donor Schiff base ligand. Int J Chem Res. 2024 Oct 1;8(4):1-11.

Padalkar R, Madgulkar A, Mate R, Pawar A, Shinde A, Lohakare S. Investigation of curcumin nanoparticles and D panthenol for diabetic wound healing in wistar rats: formulation statistical optimization and in-vivo evaluation. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2024 Mar;93:105390. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2024.105390.

Rodrigues FC, Anil Kumar NV, Thakur G. Developments in the anticancer activity of structurally modified curcumin: an up-to-date review. Eur J Med Chem. 2019 Sep;177:76-104. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.04.058, PMID 31129455.

Singh JK, Roy AK. Role of curcumin and cumin on hematological parameters of profenofos exposed mice (Mus musculus). International Journal of Current Pharmaceutical Review and Research. 2013;4(4):120-7.

Deshkar S, Satpute A. Formulation and optimization of curcumin solid dispersion pellets for improved solubility. Int J App Pharm. 2019;12(2):36-46. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2020v12i2.34846.

Anand P, Kunnumakkara AB, Newman RA, Aggarwal BB. Bioavailability of curcumin: problems and promises. Mol Pharm. 2007 Dec;4(6):807-18. doi: 10.1021/mp700113r, PMID 17999464.

Heger M, Van Golen RF, Broekgaarden M, Michel MC. The molecular basis for the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of curcumin and its metabolites in relation to cancer. Pharmacol Rev. 2014 Jan;66(1):222-307. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.004044, PMID 24368738.

Pan MH, Huang TM, Lin JK. Biotransformation of curcumin through reduction and glucuronidation in mice. Drug Metab Dispos. 1999 Apr;27(4):486-94. doi: 10.1016/S0090-9556(24)15211-7, PMID 10101144.

Ireson C, Orr S, Jones DJ, Verschoyle R, Lim CK, Luo JL. Characterization of metabolites of the chemopreventive agent curcumin in human and rat hepatocytes and in the rat in vivo and evaluation of their ability to inhibit phorbol ester-induced prostaglandin E2 production. Cancer Res. 2001 Feb 1;61(3):1058-64. PMID 11221833.

Ireson CR, Jones DJ, Orr S, Coughtrie MW, Boocock DJ, Williams ML. Metabolism of the cancer chemopreventive agent curcumin in human and rat intestine. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002 Jan;11(1):105-11. PMID 11815407.

Shoba G, Joy D, Joseph T, Majeed M, Rajendran R, Srinivas PS. Influence of piperine on the pharmacokinetics of curcumin in animals and human volunteers. Planta Med. 1998 May;64(4):353-6. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-957450, PMID 9619120.

Cheng AL, Hsu CH, Lin JK, Hsu MM, HO YF, Shen TS. Phase I clinical trial of curcumin a chemopreventive agent in patients with high risk or pre-malignant lesions. Anticancer Res. 2001;21(4B):2895-900. PMID 11712783.

Lao CD, Ruffin MT, Normolle D, Heath DD, Murray SI, Bailey JM. Dose escalation of a curcuminoid formulation. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2006 Mar 17;6:10. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-6-10, PMID 16545122.

Sharma RA, MC Lelland HR, Hill KA, Ireson CR, Euden SA, Manson MM. Pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic study of oral curcuma extract in patients with colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2001 Jul;7(7):1894-900. PMID 11448902.

Sharma RA, Euden SA, Platton SL, Cooke DN, Shafayat A, Hewitt HR. Phase I clinical trial of oral curcumin: biomarkers of systemic activity and compliance. Clin Cancer Res. 2004 Oct 15;10(20):6847-54. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0744, PMID 15501961.

Garcea G, Berry DP, Jones DJ, Singh R, Dennison AR, Farmer PB. Consumption of the putative chemopreventive agent curcumin by cancer patients: assessment of curcumin levels in the colorectum and their pharmacodynamic consequences. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005 Jan;14(1):120-5. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.120.14.1, PMID 15668484.

Farghadani R, Naidu R. Curcumin: modulator of key molecular signaling pathways in hormone independent breast cancer. Cancers. 2021 Jul;13(14):3427. doi: 10.3390/cancers13143427, PMID 34298639.

Meybodi SM, Rezaei P, Faraji N, Jamehbozorg K, Ashna S, Shokri F. Curcumin and its novel formulations for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: new trends and future perspectives in cancer therapy. J Funct Foods. 2023 Sep;108:105705. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2023.105705.

Nocito MC, DE Luca A, Prestia F, Avena P, LA Padula D, Zavaglia L. Antitumoral activities of curcumin and recent advances to improve its oral bioavailability. Biomedicines. 2021 Oct;9(10):1476. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9101476, PMID 34680593.

Wang X, Tian Y, Lin H, Cao X, Zhang Z. Curcumin induces apoptosis in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells by decreasing the expression of STAT3/VEGF/HIF-1α signaling. Open Life Sci. 2023 Jun 14;18(1):20220618. doi: 10.1515/biol-2022-0618, PMID 37333486.

Wang JB, QI LL, Zheng SD, WU TX. Curcumin induces apoptosis through the mitochondria mediated apoptotic pathway in HT-29 cells. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2009 Feb;10(2):93-102. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B0820238, PMID 19235267.

Talib WH, Al Hadid SA, Ali MB, Al Yasari IH, Ali MR. Role of curcumin in regulating p53 in breast cancer: an overview of the mechanism of action. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press). 2018 Nov 29;10:207-17. doi: 10.2147/BCTT.S167812, PMID 30568488.

Wang TY, Chen JX. Effects of curcumin on vessel formation insight into the pro and antiangiogenesis of curcumin. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2019 Jun 19;2019:1390795. doi: 10.1155/2019/1390795, PMID 31320911.

Bhandarkar SS, Arbiser JL. Curcumin as an inhibitor of angiogenesis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;595:185-95. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-46401-5_7, PMID 17569211.

Buhrmann C, Mobasheri A, Busch F, Aldinger C, Stahlmann R, Montaseri A. Curcumin modulates nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) mediated inflammation in human tenocytes in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2011 Aug 12;286(32):28556-66. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.256180, PMID 21669872.

Wilken R, Veena MS, Wang MB, Srivatsan ES. Curcumin: a review of anti-cancer properties and therapeutic activity in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Mol Cancer. 2011 Feb 7;10(1):12. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-10-12, PMID 21299897.

Ohnishi Y, Sakamoto T, Zhengguang L, Yasui H, Hamada H, Kubo H. Curcumin inhibits epithelial mesenchymal transition in oral cancer cells via c-Met blockade. Oncol Lett. 2020 Jun;19(6):4177-82. doi: 10.3892/ol.2020.11523, PMID 32391111.

Gallardo M, Calaf GM. Curcumin inhibits invasive capabilities through epithelial mesenchymal transition in breast cancer cell lines. Int J Oncol. 2016 Sep 1;49(3):1019-27. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2016.3598, PMID 27573203.

Kumar D, Kumar M, Saravanan C, Singh SK. Curcumin: a potential candidate for matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2012 Oct 1;16(10):959-72. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2012.710603, PMID 22913284.

Jakubczyk K, Drużga A, Katarzyna J, Skonieczna Zydecka K. Antioxidant potential of curcumin a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Antioxidants (Basel). 2020 Nov;9(11):1092. doi: 10.3390/antiox9111092, PMID 33172016.

Sathyabhama M, Priya Dharshini LC, Karthikeyan A, Kalaiselvi S, Min T. The credible role of curcumin in oxidative stress mediated mitochondrial dysfunction in mammals. Biomolecules. 2022 Oct;12(10):1405. doi: 10.3390/biom12101405, PMID 36291614.

HU P, KE C, Guo X, Ren P, Tong Y, Luo S. Both glypican-3/Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and autophagy contributed to the inhibitory effect of curcumin on hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Liver Dis. 2019 Jan;51(1):120-6. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2018.06.012, PMID 30001951.

Liang J, Zhou F, Xiong X, Zhang X, LI S, LI X. Enhancing the retrograde axonal transport by curcumin promotes autophagic flux in N2a/APP695swe cells. Aging (Albany, NY). 2019 Sep 6;11(17):7036-50. doi: 10.18632/aging.102235, PMID 31488728.

Hassan FU, Rehman MS, Khan MS, Ali MA, Javed A, Nawaz A. Curcumin as an alternative epigenetic modulator: mechanism of action and potential effects. Front Genet. 2019 Jun 4;10:514. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00514, PMID 31214247.

Ming T, Tao Q, Tang S, Zhao H, Yang H, Liu M. Curcumin: an epigenetic regulator and its application in cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022 Dec 1;156:113956. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113956, PMID 36411666.

BioRender.com. Available from: https://app.biorender. [Last accessed on 20 Feb 2025].

Kaur K, Kulkarni YA, Wairkar S. Exploring the potential of quercetin in alzheimers disease: pharmacodynamics pharmacokinetics and nanodelivery systems. Brain Res. 2024;1834:148905. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2024.148905, PMID 38565372.

Wang Y, Ding R, Zhang Z, Zhong C, Wang J, Wang M. Curcumin loaded liposomes with the hepatic and lysosomal dual targeted effects for therapy of hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Pharm. 2021 Jun 1;602:120628. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.120628, PMID 33892061.

Greil R, Greil Ressler S, Weiss L, Schonlieb C, Magnes T, Radl B. A phase 1 dose-escalation study on the safety tolerability and activity of liposomal curcumin (LipocurcTM) in patients with locally advanced or metastatic cancer. Cancer Chemotherpharmacol. 2018;82(4):695-706.

Wei Y, LI K, Zhao W, HE Y, Shen H, Yuan J. The effects of a novel curcumin derivative loaded long circulating solid lipid nanoparticle on the MHCC-97H liver cancer cells and pharmacokinetic behavior. Int J Nanomedicine. 2022 May 17;17:2225-41. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S363237, PMID 35607705.

Shah J, Patel S, Bhairy S, Hirlekar R. Formulation optimization characterization and in vitro anti-cancer activity of curcumin loaded nanostructured lipid carriers. Int J Curr Pharm Sci. 2022;14(1):31-43. doi: 10.22159/ijcpr.2022v14i1.44110.

Wang F, YE X, Zhai D, Dai W, WU Y, Chen J. Curcumin loaded nanostructured lipid carrier induced apoptosis in human HepG2 cells through activation of the DR5/caspase mediated extrinsic apoptosis pathway. Acta Pharm. 2020;70(2):227-37. doi: 10.2478/acph-2020-0003, PMID 31955141.

Chu Y, LI D, Luo YF, HE XJ, Jiang MY. Preparation and in vitro evaluation of glycyrrhetinic acid modified curcumin loaded nanostructured lipid carriers. Molecules. 2014;19(2):2445-57. doi: 10.3390/molecules19022445, PMID 24566313.

Guo P, PI C, Zhao S, FU S, Yang H, Zheng X. Oral co-delivery nanoemulsion of 5-fluorouracil and curcumin for synergistic effects against liver cancer. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2020;17(10):1473-84. doi: 10.1080/17425247.2020.1796629, PMID 32749895.

Al CA, PS S, ND DR C. Design and evaluation of capecitabine resealed erythrocytes by preswell and dilution techniques. Int J Biol Pharm Allied Sci. 2021;10(12).

Salve P, Doijad R, Chivate N. Resealed erythrocytes: a promising approach to enhance efficacy of anticancer drugs. IND DRU. 2020;57(3):9-20. doi: 10.53879/id.57.03.11645.

Xie X, Wang H, Williams GR, Yang Y, Zheng Y, WU J. Erythrocyte membrane cloaked curcumin loaded nanoparticles for enhanced chemotherapy. Pharmaceutics. 2019;11(9):429. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics11090429, PMID 31450749.

Kong ZL, Kuo HP, Johnson A, WU LC, Chang KL. Curcumin loaded mesoporous silica nanoparticles markedly enhanced cytotoxicity in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(12):2918. doi: 10.3390/ijms20122918, PMID 31207976.

Darwesh R, Elbialy NS. Iron oxide nanoparticles conjugated curcumin to promote high therapeutic efficacy of curcumin against hepatocellular carcinoma. Inorg Chem Commun. 2021;126:108482. doi: 10.1016/j.inoche.2021.108482.

Alshawwa SZ, Kassem AA, Farid RM, Mostafa SK, Labib GS. Nanocarrier drug delivery systems: characterization limitations future perspectives and implementation of artificial intelligence. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14(4):883. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14040883, PMID 35456717.

Desai N. Challenges in development of nanoparticle based therapeutics. AAPS J. 2012;14(2):282-95. doi: 10.1208/s12248-012-9339-4, PMID 22407288.

Pingale P, Kendre P, Pardeshi K, Rajput A. An emerging era in manufacturing of drug delivery systems: nanofabrication techniques. Heliyon. 2023;9(3):e14247. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14247, PMID 36938476.

Sedighi M, Mahmoudi Z, Abbaszadeh S, Eskandari MR, Saeinasab M, Sefat F. Nanomedicines for hepatocellular carcinoma therapy: challenges and clinical applications. Mater Today Commun. 2023 Mar;34:105242. doi: 10.1016/j.mtcomm.2022.105242.

Hegde M, Girisa S, Bharathwaj Chetty B, Vishwa R, Kunnumakkara AB. Curcumin formulations for better bioavailability: what we learned from clinical trials thus far? ACS Omega. 2023;8(12):10713-46. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.2c07326, PMID 37008131.

Vareed SK, Kakarala M, Ruffin MT, Crowell JA, Normolle DP, Djuric Z. Pharmacokinetics of curcumin conjugate metabolites in healthy human subjects. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(6):1411-7. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2693, PMID 18559556.

LI C, Naeem A, Shen J, Zha W, Zeng Q, Zhang P. Advances in the pharmaceutical research of curcumin for oral administration. Open Chem. 2023;21(1). doi: 10.1515/chem-2023-0171.

Sai Y. Biochemical and molecular pharmacological aspects of transporters as determinants of drug disposition. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2005;20(2):91-9. doi: 10.2133/dmpk.20.91, PMID 15855719.

Din FU, Aman W, Ullah I, Qureshi OS, Mustapha O, Shafique S. Effective use of nanocarriers as drug delivery systems for the treatment of selected tumors. Int J Nanomedicine. 2017 Oct 5;12:7291-309. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S146315, PMID 29042776.

Ayan AK, Yenilmez A, Eroglu H. Evaluation of radiolabeled curcumin loaded solid lipid nanoparticles usage as an imaging agent in liver spleen scintigraphy. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2017 Jun 1;75:663-70. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2017.02.114, PMID 28415513.

Sun Q, LV M, LI Y. Nanotechnology based drug delivery systems for curcumin and its derivatives in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases. J Funct Foods. 2024 Nov;122:106476. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2024.106476.

Panda SS, Thangaraju M, Lokeshwar BL. Hybrid curcumin conjugates and methods of use thereof. US20220152211A1; 2022.

Kim DH, Kwak K. Immuno ablation treatment for solid tumors. WO2023225578A3; 2024.

Guo Yongcheng. A composition with the effect of inhibiting the proliferation of liver cancer cells and its application. CN108272780A; 2018.

LI SD, Zhang W, Chao PH, Boettger R. Phospholipid free small unilamellar vesicles (pfsuvs) for drug delivery. WO2020087175A1; 2020.

Neven P, Serteyn D, Jacques D (Deceased), Kiss R, Mathieu V, Cataldo D, Rocks N. Water soluble curcumin compositions for use in anticancer and anti-inflammatory therapy. WO2009144220A1; 2009.

Aggarwal B. Selective inhibitors of STAT-3 activation and uses thereof. US20050049299A1; 2005.

Sahin F, Ulu ZO, Bolat ZB, Degirmenci NS. An anticancer formulation comprising sodium pentaborate, curcumin, and piperine for use in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. WO2023191746A1; 2023.