Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 3, 2025, 243-251Original Article

QUERCETIN-LOADED GRAPHENE OXIDE NANOPARTICLES: SYNTHESIS, OPTIMIZATION, AND EVALUATION FOR BREAST CANCER TREATMENT

TANDALE PRASHANT1, SUTTEE ASHISH1*, PANZADE PRABHAKAR2, GADADE DIPAK3

1School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Lovely Professional University, Phagwara. Punjab-144411, India. 2Srinath College of Pharmacy, Chh. Sambhajinagar, Maharashtra-431133, India. 3Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Delhi Skill and Entrepreneurship University, Dwarka Campus, Sector 9, New Delhi-110077, India

*Corresponding author: Suttee Ashish; *Email: ashish7manipal@gmail.com

Received: 01 Mar 2025, Revised and Accepted: 03 Apr 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: This study aimed to develop graphene oxide (GO) nanoparticles (NPs) loaded with Quercetin (QUE) for oncological applications, enhancing therapeutic efficacy while minimizing adverse effects.

Methods: QUE-GO NPs were synthesized using Tween 80 and probe sonication, with optimization achieved through a Box-Behnken Design (BBD) that considered parameters including GO weight, surfactant volume, and sonication time.

Results: The optimized batch 14 achieved an Entrapment Efficiency (EE) of 92.5±0.7%, with a particle size of 86.9±0.46 nm and a Polydispersity Index (PDI) of 0.158±0.001, indicating good stability. Drug release studies showed 88.60±2.3% release over 8 h (n = 3). Cytotoxicity assays in MCF-7 breast cancer and HEK293 noncancerous cells revealed enhanced cytotoxicity against MCF-7 cells (IC50: 126.20 µg/ml) (p<0.001) compared to pure QUE's (MW: 302.24 g/mol) IC50 of 175.89 µg/ml (p<0.05). The safety profile was observed for HEK 293 cells (IC50: 1009.40 µg/ml).

Conclusion: These findings support QUE-GO NPs as a promising nanocarrier for targeted cancer therapy. A favourable safety profile was observed.

Keywords: Graphene oxide, Nanocomposites, Quercetin, Nanomedicine, Anticancer, Response surface methodology, Drug delivery systems

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i3.53794 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Nanotechnology is employed in the field of nanomedicine to create advanced Drug Delivery Systems (DDSs) that enhance therapeutic efficacy while minimizing systemic toxicity. These systems enable the targeted delivery, controlled release, and improved bioavailability of therapeutic agents, which are crucial in oncology, where maximizing tumor-specific effects and minimizing harm to healthy tissues are paramount. The field of nanomedicine utilises nanotechnology to develop advanced drug delivery mechanisms that enhance therapeutic efficacy while minimizing adverse effects. These mechanisms include targeted delivery, controlled release, and enhanced bioavailability of therapeutic compounds, all of which are crucial in cancer therapy, where maximizing tumour impact and minimizing systemic toxicity are desired [1]. Nanotechnology has emerged as a vital tool for creating diverse nanoparticles (NPs) with high surface-area-to-volume ratios and distinctive properties [2].

Among the various nanocarriers for drug delivery, Graphene Oxide (GO) stands out due to its unique properties, which make it suitable for oncological applications [1]. GO exhibits a high surface area-to-volume ratio (~2630 m²/g), enabling an exceptional drug-loading capacity through π-π stacking, hydrogen bonding, and hydrophobic interactions. Unlike liposomes or polymeric NPs, GO’s mechanical robustness and pH-responsive degradation allow precise control over drug release in acidic tumour microenvironments [3]. GO demonstrates a superior drug-loading capacity of 92.5% Entrapment Efficiency (EE) compared to liposomes (70-80% EE) and polymeric NPs (75-85% EE) due to its high surface area and π-π interactions [4]. For instance, GO-based DDSs have demonstrated enhanced tumour accumulation in breast cancer models, outperforming conventional carriers, such as PLGA NPs, in terms of stability and payload capacity. Nanocarriers can overcome the obstacles encountered in traditional drug delivery systems. These include liposomes, polymeric NPs, and solid lipid NPs [5]. For instance, GO has been successfully used to deliver doxorubicin in breast cancer models [6]. Graphene is a multifunctional carbon nanomaterial that offers promising opportunities for the development of platform technologies for cancer therapy. The surface functionalization of graphene-specific drugs targeting cancer cells and tissues improves treatment efficacy [7]. Research has shown that functionalized nano-GO exhibits significantly more significant cytotoxic effects when combined with two anticancer drugs compared to a single one [8].

The uncontrolled proliferation of abnormal cells is a hallmark of cancer, resulting in malignant growth. The primary cause of illness and death in most cancer patients is the migration of malignant cells to neighboring tissues and remote organs [9]. Cancer has become a significant public health issue owing to its widespread occurrence and high mortality rate. Patients with cancer have access to a range of treatment approaches, including surgical procedures, radiation therapy, drug-based chemotherapy, and therapies that target specific cancer mechanisms [10]. Chemotherapy, a common approach in cancer treatment, employs drugs designed to inhibit the proliferation of cancer cells or to eradicate them. While this method is primarily administered as systemic therapy, there are also non-systemic alternatives for delivering chemotherapy [11]. Various drug delivery systems have been developed to overcome the limitations of chemotherapy.

Quercetin (QUE), a pentahydroxy flavone, is the most prevalent flavanol in food and is particularly abundant in apples and capers. Research has linked QUE to the prevention of non-communicable diseases [12, 13]. Naturally occurring flavonoids exhibit various pharmacological effects, including anticancer, antioxidant, antibacterial, and anti-inflammatory [14-17]. Research has shown that QUE acts as a potent anticancer compound. It suppresses invasion and blood vessel formation in oesophagal cancer cells, induces self-destruction and programmed cell death in lung cancer cells, and hinders the spread of triple-negative breast cancer [18–20]. QUE nanocomposites exhibit pH-responsive drug release with enhanced release rates in acidic environments, which is characteristic of cancer. Research has demonstrated that a nanocomposite of ZnO and QUE effectively inhibits the proliferation of MCF-7 breast cancer cells while exhibiting high compatibility with healthy cells [21].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

QUE was purchased from Bio-Molecules, Khandwa, M. P., India. GO was procured from AdNano® Technologies Private Limited (Shimoga, Karnataka, India). This study used analytical-grade materials and solvents.

Compatibility study

A Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy compatibility study was conducted to assess the interaction between QUE and GO in the nanoparticle formulation. This method analyses the principal peaks of the drug QUE, carrier GO, their physical mixture, and the optimized nanoparticle formulation to evaluate compatibility and potential chemical interactions within the formulation composition. By comparing the spectra of the individual components to those of the nanoparticle formulation, FTIR enables the detection of any new bond formation or significant peak shifts that may indicate incompatibility or undesired chemical reactions between QUE and GO. This analysis is crucial for confirming the successful loading of QUE onto the GO nanocarriers without degradation, as well as verifying the stability and integrity of the drug-carrier system.

FTIR

The interaction between the excipients and drug was assessed using FTIR spectroscopy. This investigation analyzed the principal peaks of the drug, excipients, their mixtures, and the optimized formulation to evaluate compatibility within the formulation composition. The spectra were recorded using a Shimadzu IR Affinity-1 spectrophotometer, encompassing a spectral range of 4000–400 cm−1.

Fabrication of QUE-GO NP’s procedure

The preparation of GO NPs loaded with QUE followed a systematic approach. Initially, a mixture of QUE (0.1% w/v) was prepared in ethanol by combining QUE (20 mg) with ethanol (20 ml), and the mixture was stirred continuously until it became transparent. Then, 100 mg of GO was added to the QUE mixture. The resulting combination was thoroughly mixed to ensure complete and even distribution [4]. Subsequently, 0.05 ml of Tween 80, a surfactant, was introduced into the solution and mixed manually. The resulting solution was subjected to probe sonication for 60 min with periodic cooling to maintain a temperature below 40 °C. This step was designed to enhance the dispersion and stability of NPs further. After sonication, the mixture was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 15 min to separate the unbound QUE from the clustered NPs [22]. The NPs were then washed three times with deionized water using centrifugation to remove any residual QUE [23]. Finally, the QUE-GO NPs were dried either under a vacuum or at 40 °C overnight and subsequently collected for further characterization and analysis.

Experimental design

The response surface methodology Box-Behnken Design (BBD) utilizes three independent variables [24, 25]. BBD was selected for its efficiency in optimizing three factors with minimal experimental runs (15 vs. 27 in Central Composite Design). The sonication time weights of GO, the volumes of surfactant Tween 80, and the sonication time (in minutes) are listed in table 1. The response variables were EE, mean Particle Size (MPS), and Polydispersity Index (PDI).

Optimization of QUE-GO NPs synthesis conditions

Responses: The dependent variables (responses) measured based on variations in the factors are listed in table 1.

Table 1: Variables used, experimental design, and observed responses from randomised runs in the BBD

| BBD | ||||||

| Factors: 3 | Replicates: 1 | |||||

| Base runs: 13 | Total runs: 15 | |||||

| Base blocks: 1 | Total blocks: 1 | |||||

| Center points: 3 | ||||||

| Levels, actual (Coded) | ||||||

| Low (-1) | Medium (0) | High (+1) | ||||

| Independent variables | ||||||

| X1: Amount of GO (mg) | 80 | 100 | 120 | |||

| X2: Surfactant (Tween 80) (ml) | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.08 | |||

| X3: Sonication Time (min) | 40 | 60 | 80 | |||

| Dependent variables | ||||||

| Y1: EE (%) | Maximum | |||||

| Y2: MPS (nm) | Minimum | |||||

| Y3: PDI | Less than 0.2 | |||||

| Independent variables | Dependent variables* | |||||

| Run | X1 | X2 | X3 | Y1 | Y2 | Y3 |

| 1 | -1 | 1 | 0 | 78.3±1.06 | 83.6±0.70 | 0.16681±0.00321 |

| 2 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 80.8±1.14 | 82.9±0.80 | 0.16658±0.00103 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 83.3±1.17 | 85.3±1.06 | 0.16409±0.00153 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 82.2±1.32 | 85.7±0.47 | 0.16321±0.00153 |

| 5 | 0 | -1 | -1 | 82.6±0.62 | 86.7±0.57 | 0.16404±0.00101 |

| 6 | 0 | 1 | -1 | 82.3±0.86 | 85.5±0.59 | 0.16392±0.00153 |

| 7 | -1 | 0 | -1 | 76.0±1.15 | 84.7±0.46 | 0.16712±0.00201 |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 82.7±0.86 | 85.5±1.02 | 0.16398±0.00252 |

| 9 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 88.4±0.62 | 87.2±0.26 | 0.15954±0.00153 |

| 10 | 1 | -1 | 0 | 87.9±0.57 | 87.8±0.36 | 0.16245±0.00058 |

| 11 | 1 | 0 | -1 | 86.0±1.13 | 88.2±0.65 | 0.15972±0.00153 |

| 12 | 0 | -1 | 1 | 83.5±0.83 | 84.7±0.46 | 0.16397±0.00153 |

| 13 | -1 | -1 | 0 | 79.3±0.67 | 83.8±0.61 | 0.16812±0.00101 |

| 14 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 92.5±0.70 | 86.9±0.46 | 0.15819±0.00103 |

| 15 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 83.0±1.14 | 84.1±0.72 | 0.16295±0.00153 |

*Data are presented as mean±SD (n=3)

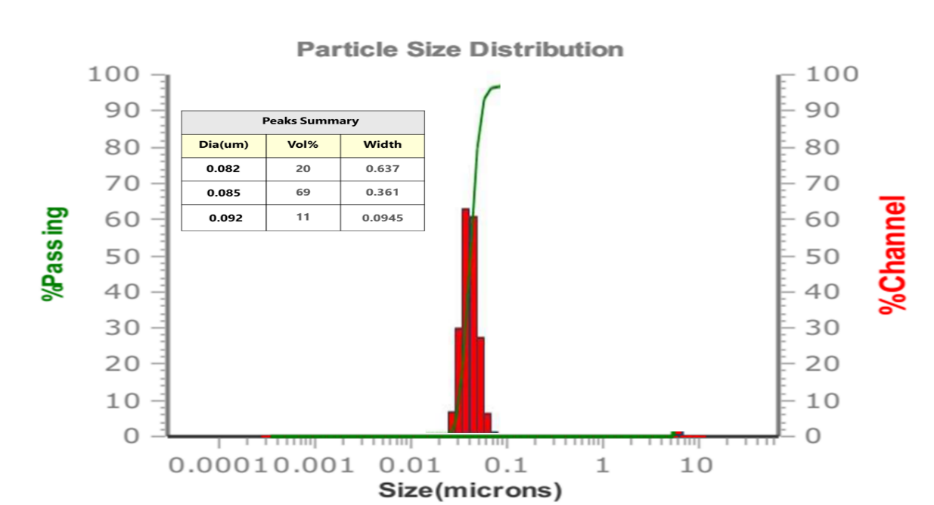

Entrapment Efficiency

To determine the quantity of QUE bound to the GO NPs, a suspension containing 50 mg of QUE-GO NPs was subjected to centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 15 min. This process separated the unattached QUE from the NPs. The resulting supernatant, which contained free QUE, was then carefully extracted and filtered through a 0.45 µm filter.

The concentration of free QUE in the supernatant was quantified using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) [26]. A series of QUE standards with known concentrations were used to create a calibration curve, which was then used for comparison with the supernatant samples. The EE was calculated using the following equation:

EE (%)

Equation 1: Entrapment Efficiency (%)

The quantity of loaded QUE was determined by deducting the amount of unbound QUE in the supernatant from its initial concentration.

Particle size (PS), zeta potential (ZP) (ζ)

The MPS and ZP values were determined using dynamic light scattering techniques with a Nanotrac wave II instrument manufactured by Microtrac, Japan. To determine the dimensions of the QUE-GO NPs, a 3-ml sample was diluted with deionized water and transferred to a cell cuvette. The samples were scanned three times to obtain the average measurement (n = 3).

In vitro drug release

A controlled release study utilizing a dissolution testing apparatus was performed to explore the drug release patterns of GO NPs loaded with QUE. First, 50 mg of QUE-GO NPs were accurately weighed and incorporated into a dialysis bag, which was then tied at both ends. Next, 200 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with a pH of 7.4 was added to the beaker to help disperse the NPs. The beaker was subsequently placed in a USP (United States Pharmacopeia) type-II paddle dissolution apparatus and maintained at 37±2 °C. The dissolution apparatus was operated at 100 rpm [27]. At 1-hour intervals, 3 ml samples of the solution were withdrawn from the apparatus for analysis. To maintain a constant volume of the release medium, an equal amount of fresh buffer solution was immediately added to the beaker following the withdrawal of each sample. The extracted samples were analyzed to measure the amount of QUE released by NPs at various intervals [27, 28].

Cell line characterisation

The National Center for Cell Science (NCCS) supplied both the MCF-7 and HEK293 cell lines used in this study, which were characterized to confirm their suitability for experiments. Microbial contamination, including the presence of bacteria and fungi, was excluded using standard sterility testing methods. Cross-contamination was evaluated by direct observation of the cellular morphology under an inverted microscope [8, 29].

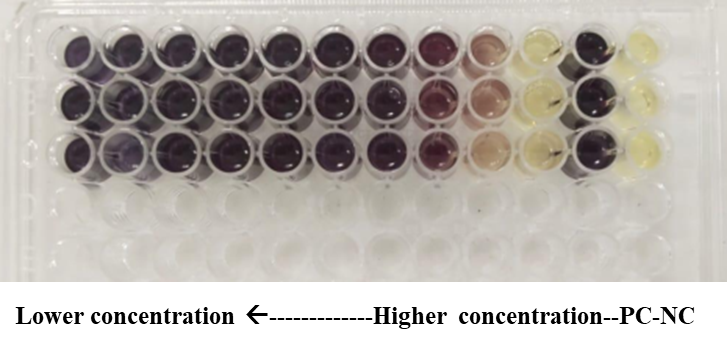

Cytotoxicity assay

MTT assay was used to assess the cytotoxic effects of QUE and QUE-GO NPs. In 96-well plates, MCF-7. Similar to the noncancerous cells (HEK293), 5×104 cells were plated in each well, with each well containing 100 µL of culture medium. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was used to prepare QUE solutions, which were then diluted in a culture medium to achieve concentrations from 1.95 µg/ml to 1000 µg/ml. Each experiment was performed in triplicate (n = 3).

Additionally, the cytotoxicity of QUE was examined in the non-cancerous HEK293 cell line over 48 h.

Controls: Positive Control (+Ve) wells containing cells and media without the test sample to establish the baseline viability. Negative Control (-Ve) wells contained only media, without cells or the test sample, to account for background absorbance.

After 24 h of exposure, 20 µl** of MTT reagent (5 mg/ml) was added to each well, and the plates were incubated for an additional 4 h at 37 °C. To dissolve the resulting formazan crystals, 100 µl** DMSO was added to each well, followed by overnight incubation. Absorbance was measured at 570 nm using an ELISA plate reader.

RESULTS

Compatibility study

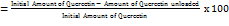

The results of the FTIR analysis of the QUE-GO mixture are shown in table 2.

Hydroxyl (-OH) Groups: QUE exhibits a broad-OH stretch at 3631 cm⁻¹ (alcoholic), while GO shows broad-OH peaks at 3491–3261 cm⁻¹ (alcoholic and carboxylic). In the mixture, these peaks merge into broader bands at 3522–3332 cm⁻¹ and 3296 cm⁻¹. The retention of the wide-OH signals, coupled with slight shifts, indicated hydrogen bonding between the phenolic and OH groups of QUE and GO’s oxygenated functionalities of GO (e.g.,-OH and-COOH). This interaction likely enhances the stability of the mixture without forming covalent bonds.

Carbonyl (C=O) and Aromatic Features: The C=O stretches in QUE (1743–1735 cm⁻¹) and GO (1735 cm⁻¹) overlap closely in the mixture (1747–1732 cm⁻¹), suggesting no significant chemical alteration of these groups. Similarly, aromatic C-H stretches (3176–3124 cm⁻¹ in QUE and 3169 cm⁻¹ in GO) persisted in the mixture, confirming the structural integrity of both components.

Alkyne/Nitrile and Fingerprint Regions: A minor shift in the alkyne/nitrile peak from 2360 cm⁻¹ (QUE) to 2368 cm⁻¹ (mixture) indicates weak interactions, possibly π-π stacking, between the aromatic rings of QUE and the graphitic domains of GO. Additionally, the emergence of firm fingerprint region peaks (1029–1010 cm⁻¹) in the mixture, which is not explicitly prominent in the GO spectrum, suggests enhanced vibrational modes due to QUE-GO associations.

Table 2: FT-IR detail peak intensities in QUE, GO and a mixture of QUE-GO

| Functional Group/Vibration | QUE Peaks | GO Peaks | QUE+GO Observations | Implications |

| O-H Stretching (3200–3500 cm⁻¹) |

Broad peak (phenolic-OH) |

Broad peak (hydroxyl groups) |

Broadening/shift in-OH peak | Hydrogen bonding enhances compatibility |

| C=O Stretching (1650–1720 cm⁻¹) |

Sharp peak (~1650 cm⁻¹, ketone) | Peak (~1720 cm⁻¹, carboxylic acid) | Shifting/diminishing of QUE’s C=O peak | Interaction with GO’s-COOH groups |

| Aromatic C=C (1500–1600 cm⁻¹) |

Peaks (aromatic rings) |

Weak peak (~1600 cm⁻¹, graphitic C=C) | Shift in QUE’s C=C | π-π stacking improves drug loading on GO |

| C-O Stretching (1050–1300 cm⁻¹) |

- | Strong peaks (epoxy/alkoxy groups) | Reduced intensity/shifts in GO’s C-O peaks | Interaction with QUE’s-OH groups |

| General compatibility | - | - | No new covalent peaks | Stable physical mixture, no degradation |

The spectrum confirms the presence of functional groups from both QUE and GO, such as O–H, C=O, and C–O, suggesting successful mixing without significant chemical degradation of either component, as shown in fig. 1.

Fabrication of QUE-GO NPs

The synthesis of GO NPs loaded with QUE-GO NPs was successfully achieved through a systematic protocol. The process began with the dissolution of QUE to obtain a 0.1% (w/v) solution in ethanol, yielding a homogeneous and transparent solution that confirmed the effective solubilization of the hydrophobic flavonoid. The subsequent addition of GO (100 mg) to the QUE-ethanol mixture, followed by vigorous stirring, ensured the dispersion of GO within the matrix.

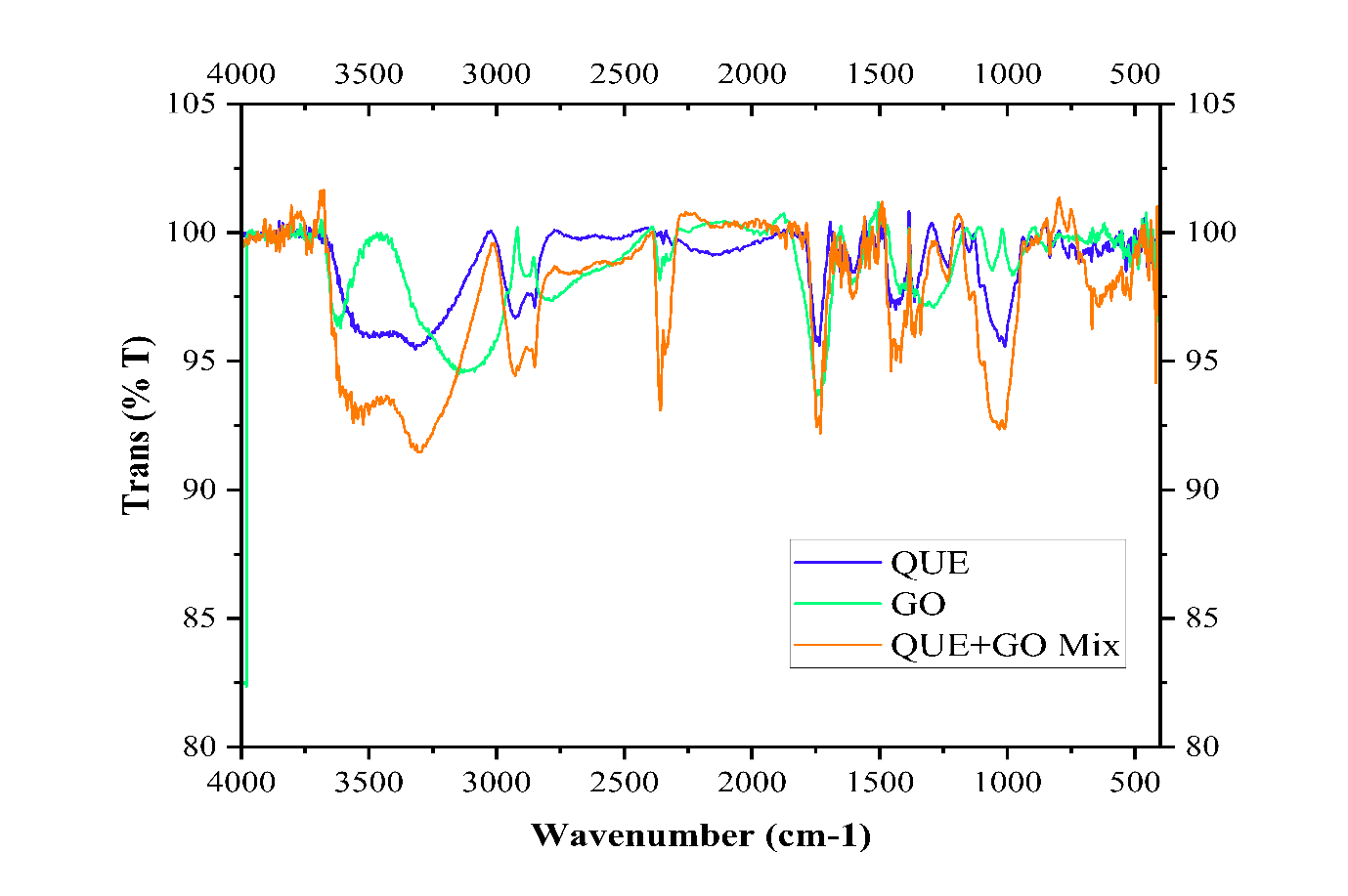

Optimization of QUE-GO NPs

Optimization can be conducted in specific complex experimental designs such as BBD, which employs response surface methodology. These investigations aimed to establish the most efficacious relationships between variables and experimental outcomes. To determine the optimal components of the formulation variables that influence product quality, a BBD was used to optimize the composition of QUE-GO NPs.

Fig. 1: Overlay spectra of GO, QUE and a mixture of QUE-GO

Fig. 2: Effect of amount of GO and sonication time interaction on EE (a) contour graphs (b) surface graphs, effect on MPS (c) contour graphs (d) surface graphs, effect on PDI (e) contour graphs (f) surface graphs. Comparison of the data obtained with the experimental data of the QUE-GONPs formulation graphs for (g) EE, (h) MPS, and (i) PDI

Table 3: ANOVA of the fitted equation for EE, MPS, and PDI of QUE-GO NPs

| EE (%) | MPS (nm) | PDI | ||||||||||||

| Sum of squares | Mean square | F value | P value | Sum of squares | Mean square | F value | P value | Sum of squares | Mean square | F value | P value | |||

| Model | 225.03 | 75.01 | 46.45 | <0.0001 | 34.63 | 11.54 | 154.49 | <0.0001 | 1.080E-004 | 3.599E-005 | 52.67 | <0.0001 | ||

| GO (X1) | 204.02 | 204.02 | 126.33 | <0.0001 | 28.50 | 28.50 | 381.48 | <0.0001 | 1.032E-004 | 1.032E-004 | 150.98 | <0.0001 | ||

| Surfactant (X2) | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.13 | 0.7244 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 11.31 | 0.0063 | 3.591E-006 | 3.591E-006 | 5.25 | 0.0426 | ||

| Sonication Time (X3) | 20.80 | 20.80 | 12.88 | 0.0043 | 5.28 | 5.28 | 70.69 | <0.0001 | 1.209E-006 | 1.209E-006 | 1.77 | 0.2104 | ||

| Residual | 17.76 | 1.61 | -- | -- | 0.82 | 0.075 | -- | -- | 7.517E-006 | 6.834E-007 | -- | -- | ||

| Lack of fit | 17.16 | 1.91 | 6.29 | 0.1447 | 0.74 | 0.082 | 2.06 | 0.3693 | 7.058E-006 | 7.842E-007 | 3.41 | 0.2472 | ||

| Pure error | 0.61 | 0.30 | 0.080 | 0.040 | 4.598E-007 | 2.299E-007 | ||||||||

| Std deviation | 1.27 | 0.27 | 8.267E-004 | |||||||||||

| Predicted R2 | 0.8491 | 0.9526 | 0.8649 | |||||||||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.9069 | 0.9705 | 0.9172 | |||||||||||

| R2 | 0.9268 | 0.9768 | 0.9349 | |||||||||||

| Best fitted model | Linear | Linear | Linear | |||||||||||

| Y1=53.43667+0.25250*X1-5.41667*X2+0.080625*X3 | Y1=79.04833+0.094375*X1-10.83333*X2-0.040625*X3 | Y1=0.18389-1.79563E-004*X1-0.022333*X2-1.94375E-005*X3 | ||||||||||||

(n=3, Data are expressed as mean±SD (n=3)

Fitting data to the model

The BBD employed in this investigation yielded 15 distinct formulations. We examined the influence of independent variables on the observed dependent responses. After fitting the observed responses to the design, optimal models were derived for the three dependent variables of the QUE-GO NPs formulation: EE, MPS, and PDI.

The independent variables are given in Table 1. The analysis of the study outcomes, shown in table 3, demonstrated a firm fit for the correlation coefficients of the equations derived from the experimental values. Displays the R² values, with all cases exhibiting p-values less than 0.05. In any model, the significance of a term in influencing the response variables is characterized by a combination of a small p-value and a significant F value, added effect sizes, and partial eta-squared (η²p). For model terms to be considered significant, Probe>F (p-value) should be less than 0.05 [30]. In the 'lack of fit test' section of the appropriate model, the Probe F-value should not be statistically significant (p>0.05).

Response analysis for optimization of QUE-GO NPs formulation

EE, MPS, and PDI

EE is a crucial parameter that significantly impacts the therapeutic efficacy of NPs. The observed EE% values ranged from 76% to 92.5%, depending on the formulation conditions. Statistical analysis revealed that the amount of GO and sonication time had a significant impact on the EE% (p<0.05). Higher concentrations of GO and increased sonication time resulted in higher EE%, which was likely due to the enhanced interaction between QUE and GO. The optimal formulation (Batch 14) exhibited an EE of 92.5%, which falls within the acceptable range for effective drug delivery.

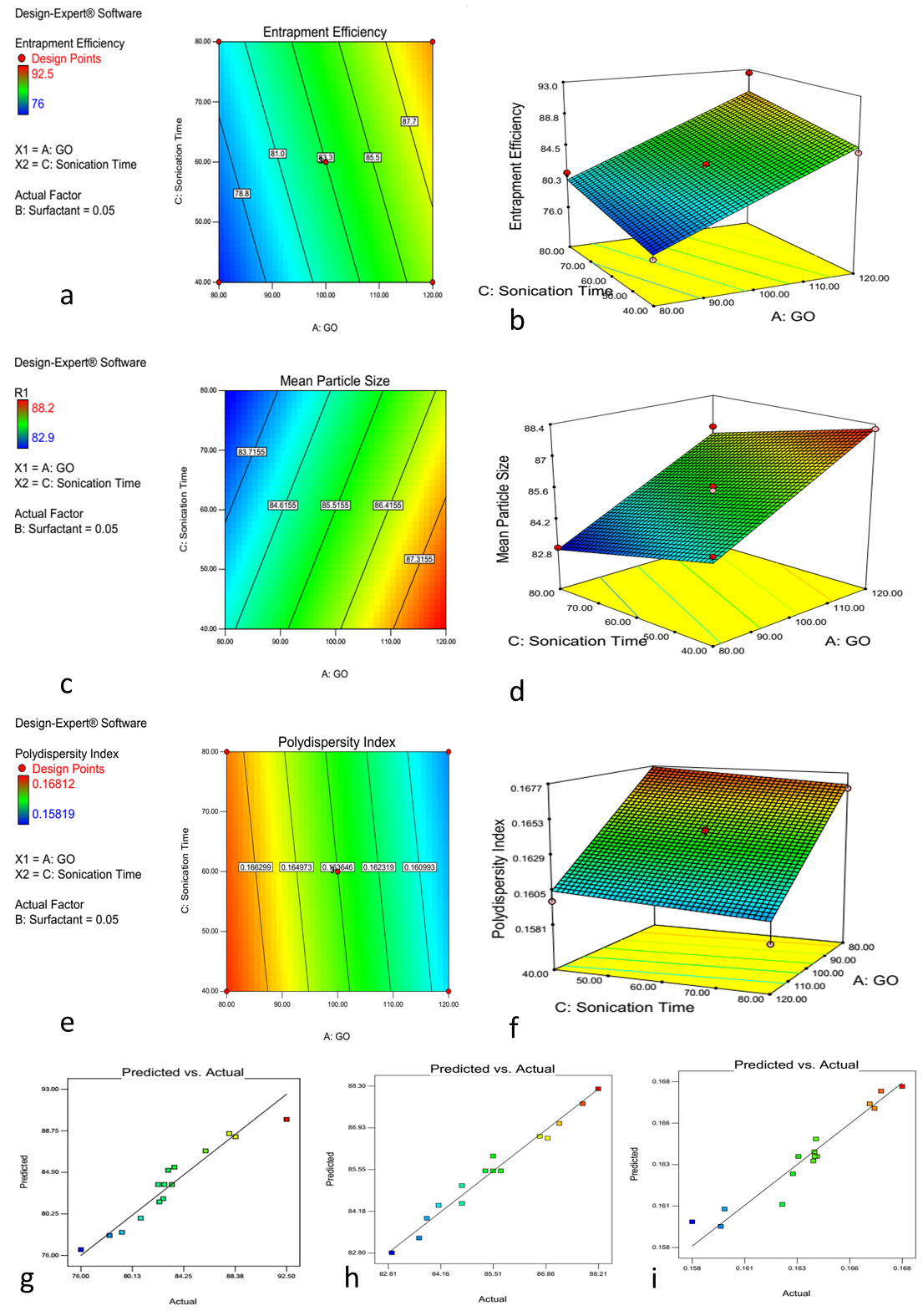

The MPS of QUE-GO NPs plays a crucial role in their cellular uptake and bioavailability. The MPS varied from 82.9 nm to 88.2 nm, primarily influenced by the amount of GO and the duration of sonication. The statistical model revealed a significant effect of the amount of GO and sonication time, where increasing both resulted in a decrease in particle size. The optimized formulation yielded a particle size of 82.9 nm, as illustrated in fig. 3, which ensured enhanced stability and efficient cellular uptake.

PDI

PDI measures the uniformity of particle size distribution, with lower values indicating a more homogeneous nanoparticle formulation. PDI values ranged between 0.15819 and 0.16812, indicating a relatively uniform size distribution. Statistical analysis demonstrated that the amount of GO had a substantial influence on the PDI. The optimized formulation (batch 14) achieved a PDI of 0.15819, confirming the stability and monodispersity of the NPs. Tween 80 reduces surface tension and prevents particle aggregation, thereby stabilising the formulation. At concentrations of 0.05 ml or lower, Tween 80 adsorbs at the interface, preventing coalescence. However, increasing its concentration beyond 0.05 ml may lead to micelle formation, which can alter stability. Excessive Tween 80 may also induce phase separation or impact viscosity, negatively affecting stability. Tween 80 can modulate drug release by altering the solubility and permeability of the drug. At optimal concentrations, it enhances drug release. However, excessive amounts can entrap the drug within micelles, thereby reducing the rate of drug release.

Fig. 3: Particle size distribution of optimized batch 14

Zeta potential

The zeta potential of the optimized QUE-GO NPs was measured at-32.5±1.2 mV, indicating a stable colloidal dispersion due to strong electrostatic repulsion between particles. This negative surface charge arises primarily from the oxygen-containing functional groups on GO, such as carboxyl (-COOH) and hydroxyl (-OH) groups, which ionise in aqueous media.

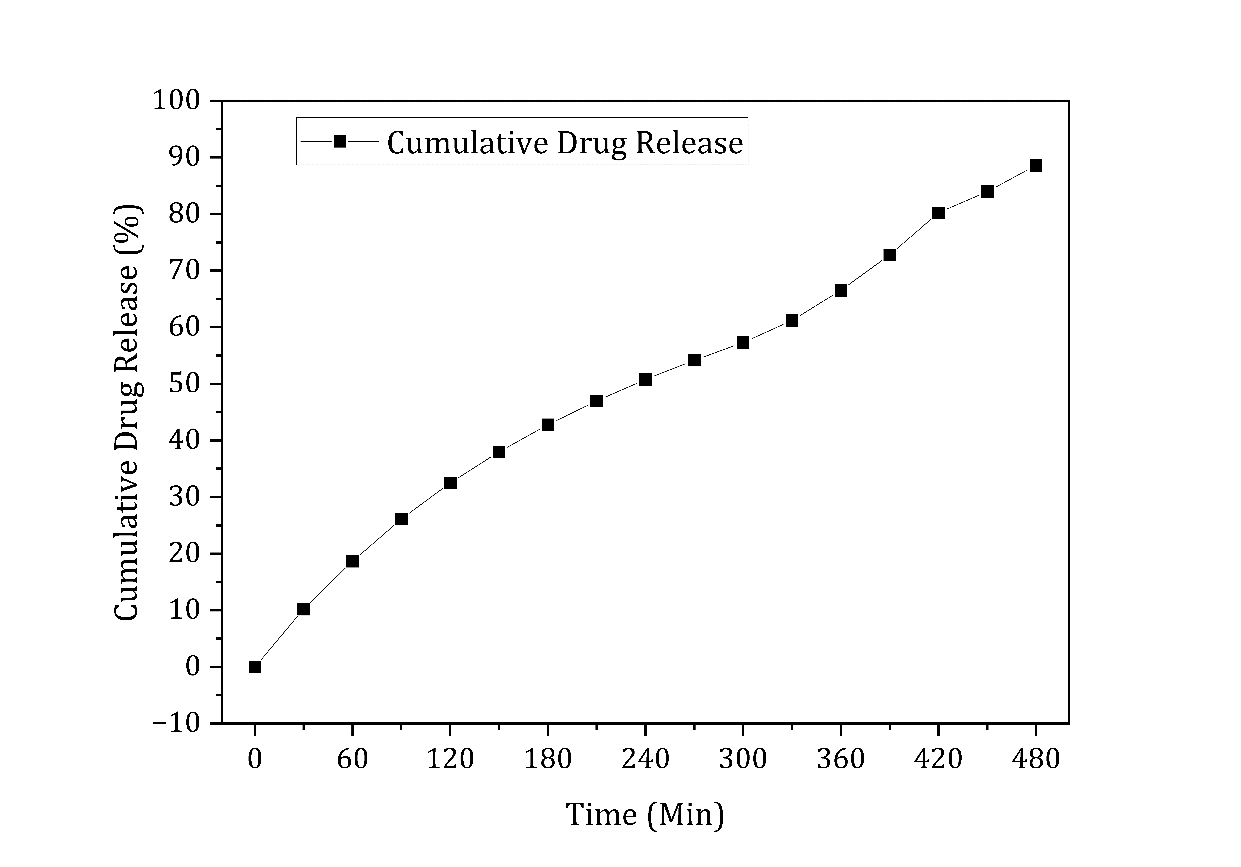

In vitro drug release

In this study, we investigated the release profile of QUE-GO NPs using a dialysis method over 8 h. The results demonstrated that optimized batch 14 exhibited a remarkable cumulative drug release of 88.60±2.3% at the end of 8 h (n = 3), as shown in fig. 4. This indicates the effective encapsulation and subsequent release of QUE from the NPs, suggesting that QUE-GO NPs can serve as a promising delivery system for this bioactive compound.

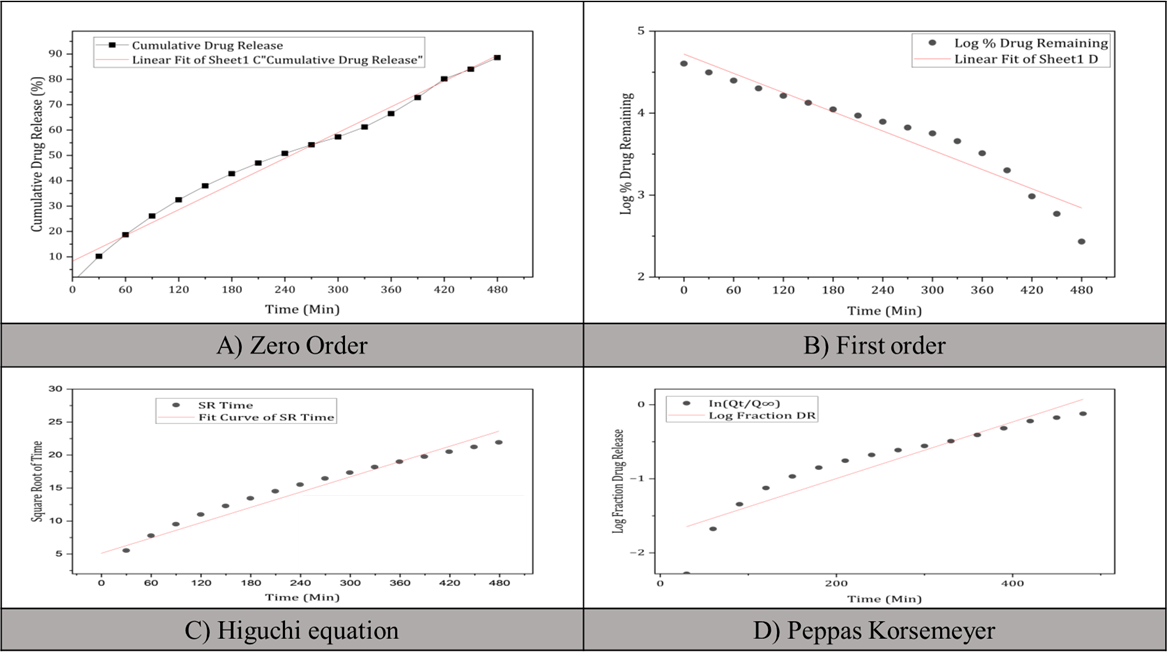

In vitro drug release kinetics

The in vitro drug release kinetics of QUE from the optimized batch of QUE-GO NPs formulations are shown in fig. 5. The in vitro release of QUE from the QUE-GO NPs dispersion was found to be 88.60±2.3% after 8 h (n = 3). The data best fit the Korsmeyer-Peppas model (R² = 0.98), suggesting diffusion-controlled release.

Fig. 4: Cumulative percent release of optimize batch of QUE-GO NPs (Batch 14)

Fig. 5: Graphs for release kinetic study of optimized batch 14

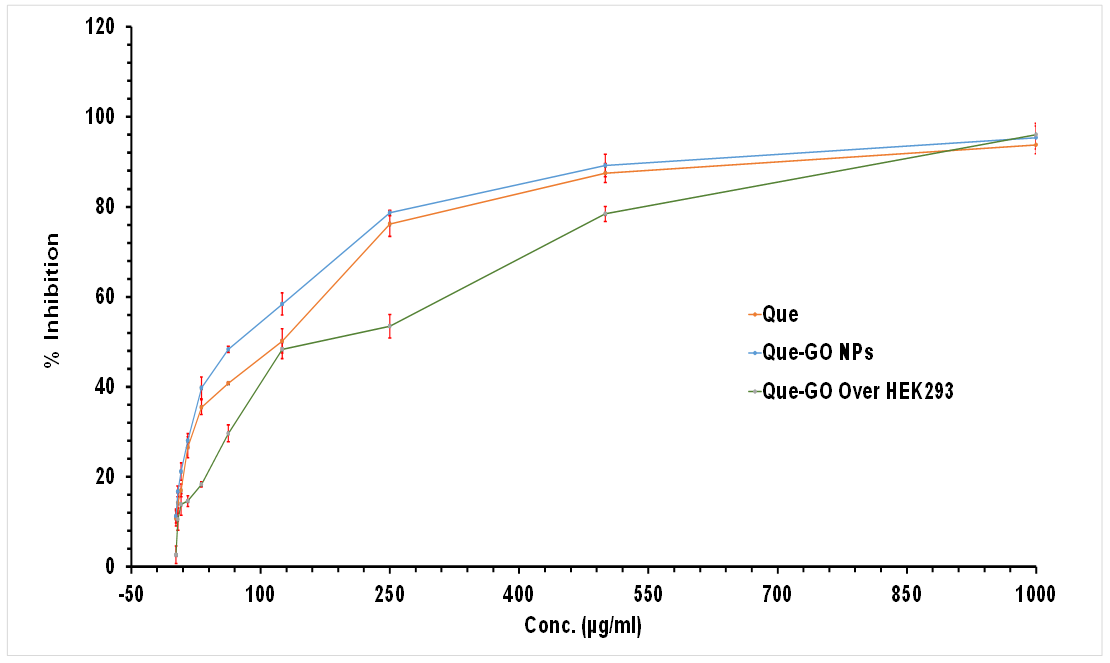

Evaluation of anticancer activity test (Cytotoxicity study)

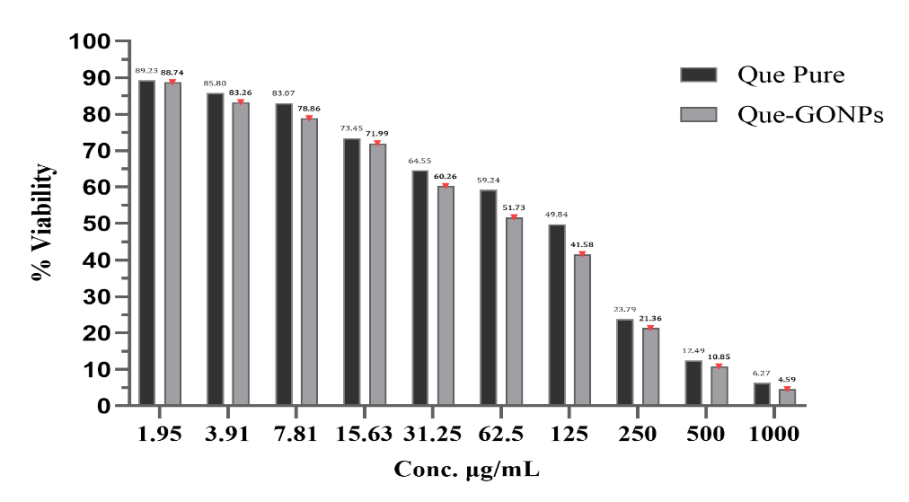

Pure drug (QUE)

Pure QUE exhibits a dose-dependent cytotoxic effect on MCF-7 breast cancer cells, serving as a well-established in vitro model for studying breast cancer therapeutics. At a high concentration of 1000 µg/ml, QUE exhibited a significant cytotoxic effect, with an inhibition rate of 93.73%. This finding highlights the strong inhibitory potential of QUE against MCF-7 cells at elevated doses, suggesting its potential as an anticancer agent, as shown in fig. 6.

Fig. 6: Microdilution assay using MTT staining (PC: Positive Control, NC: Negative Control) (n=3)

The cytotoxic effect of QUE decreased sharply with decreasing concentration, with an IC50 value of 175.89 µg/ml (molecular weight: 302.24 g/mol). The relatively low IC50 underscores the potency of QUE, which requires only a moderate concentration to achieve 50% inhibition of cell viability.

QUE-GO NPs

QUE-GO NPs demonstrated enhanced cytotoxicity, with a reduced IC50 value of 126.20 µg/ml (molecular weight: 302.24 g/mol). This increased activity may be attributed to the improved bioavailability and cellular uptake of QUE facilitated by the GO. However, increased activity was observed in the cancerous MCF-7 cells shown in fig. 8.

Biocompatibility of HEK 293 cells

The IC50 value of 1009.40 µg/ml for QUE-GO in HEK293 noncancerous cells suggests that it has low cytotoxic potential in normal, noncancerous cells, indicating a favourable safety profile at lower concentrations.

Fig. 7: Conc. (µg/ml) Vs % viability (Data are presented as mean±SD (n=3)

Fig. 8: Conc. (µɡ/ml) Vs % Inhibition of Pure QUE, QUE-GO NPs and QUE-GO over HEK293 (Data are presented as mean±SD (n=3)

DISCUSSION

The absence of new peaks in the FTIR QUE-GO Mixture study, indicative of non-covalent bonding, suggests that no chemical reactions occurred. This indicates compatibility through non-covalent interactions, such as hydrogen bonding and van der Waals forces, which are beneficial for preserving the inherent characteristics of both QUE and GO.

The synthesis and characterization of QUE-GO NPs have demonstrated promising results in enhancing the anticancer potential of QUE. FTIR analysis confirmed the successful incorporation of QUE into the GO nanocarriers, as evidenced by the presence of characteristic peaks from both components in the mixture spectrum. This suggested that QUE was effectively loaded onto the GO NPs without significant chemical degradation.

The use of a BBD enabled the systematic optimization of the synthesis parameters, ensuring reproducibility and scalability. Batch 14 exhibits a maximum EE of 92.5±0.7%, indicating a robust interaction between QUE and GO, likely mediated by π-π stacking, hydrogen bonding, and hydrophobic interactions. These non-covalent bonds are critical for stabilizing the drug-nanocarrier complex while preserving the bioactivity of QUE. The model exhibited high predictability (R2 = 0.9268 for EE), confirming its validity. The small particle size (86.9±0.46 nm) and low PDI (0.158±0.001) are particularly advantageous for tumour targeting, as NPs in this size range can exploit the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, facilitating passive accumulation in tumour tissues. Furthermore, a narrow PDI signifies homogeneity in nanoparticle distribution, which is essential for consistent drug release kinetics and predictable in vivo behavior [31].

The sustained drug release profile, with 88.60±2.3% drug release after 8 h (n = 3), aligns with the desired pharmacokinetic profile for cancer therapy, where prolonged exposure to therapeutic agents enhances tumour cell apoptosis while reducing the dosing frequency. This controlled release may be attributed to the gradual diffusion of QUE from the GO matrix coupled with the pH-responsive degradation of GO in the acidic tumour microenvironment. Such a mechanism could minimize premature drug leakage into the systemic circulation, thereby improving bioavailability [3].

The marked reduction in IC50 values of QUE-GO NPs (126.20 µg/ml) compared to free QUE (175.89 µg/ml) in MCF-7 cells underscores the role of nanoparticle-mediated delivery in enhancing therapeutic efficacy. This improvement likely stems from multiple factors: the nanoscale size of QUE-GO NPs promotes cellular uptake via endocytosis, thereby bypassing efflux pumps that often limit intracellular drug accumulation. GO’s high surface area facilitates higher drug loading, ensuring a greater payload reaches tumour cells, and the potential synergistic effects between QUE and GO may amplify oxidative stress and apoptosis in cancer cells [32].

Equally significant is the selectivity of QUE-GO NPs, as evidenced by their significantly higher IC50 in HEK 293 cells (1009.40 µg/ml) than in MCF-7 cells. This differential toxicity suggests that QUE-GO NPs preferentially target cancer cells, sparing healthy tissues —a critical advantage for reducing off-target effects. This selectivity may arise from the metabolic disparities between cancerous and noncancerous cells, such as heightened glutathione levels in tumours that could accelerate GO degradation and QUE release. However, further mechanistic studies are required to confirm these hypotheses [33].

However, this study has some limitations. The in vitro nature of this study may not fully reflect in vivo performance. Further animal studies are required to evaluate its pharmacokinetics, biodistribution, and anticancer efficacy. Additionally, long-term stability studies and investigations into the potential toxicity of GO carriers are beneficial.

In conclusion, this study provides a strong foundation for the development of QUE-loaded GO NPs as improved anticancer formulations. The enhanced cytotoxicity against breast cancer cells, coupled with good biocompatibility, warrants further investigation of this nanocarrier system for targeted cancer therapy.

In vivo studies to assess the bio-distribution, pharmacokinetics, and anticancer efficacy of NPs may be explored in future. In vivo studies will use BALB/c mice with MCF-7 xenografts to determine tumour volume reduction and biodistribution. GO can be degraded by Horseradish Peroxidase HRP in the presence of hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂). This process oxidises GO into smaller carbon fragments and ultimately mineralises it into CO₂ and water. The degradation efficiency depends on GO's surface chemistry (e. g., oxygen-containing functional groups) and the pH conditions [34].

CONCLUSION

The incorporation of QUE into GO NPs significantly enhanced their cytotoxicity against MCF7 cancer cells while maintaining reasonable safety for HEK293 cells. QUE-GO NPs offer a promising approach to improving the bioavailability and therapeutic potential of QUE. This study demonstrated the successful synthesis and characterization of QUE-loaded GO NPs, with optimized formulations exhibiting high EE and controlled release profiles. The NPs exhibited enhanced anticancer activity compared to pure QUE, with a lower IC50 value against MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Additionally, the formulation has potential biocompatibility with noncancerous HEK293 cells. These findings suggest that QUE-GO NPs could be a valuable strategy for targeted cancer therapy, potentially improving treatment outcomes while minimizing side effects.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We want to express our deepest gratitude to Lovely Professional University, Punjab, India, and the Srinath College of Pharmacy, Department of Pharmaceutics, Chh. Sambhajinagar, MS, India, and the Sanjivani Rural Education Society’s Sanjivani College of Pharmaceutical Education and Research, Kopargaon, Maharashtra, India, for providing the instrumentation.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Tandale Prashant contributed to the conceptualisation, design of experiments, visualisation, investigation, data curation, interpretation of studies outcomes, and writing of the original draft. They also reviewed and edited the manuscript. Dr. Suttee Ashish provided supervision, contributed to conceptualisation, experimental design, interpretation of studies outcomes, visualisation, and investigation, and participated in writing, reviewing, and editing. Dr. Panzade Prabhakar provided supervision and conceptual guidance and contributed to the interpretation of study outcomes, as well as writing, reviewing, and editing. Dr. Dipak D. Gadade contributed to the conceptualisation, design of experiments, interpretation of study outcomes, and review and editing of the final manuscript. All authors collaborated to ensure the integrity and quality of this research.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

Ardekani ZM, Lorenzo Leal AL, Bach H. Nanomedicine mediated drug delivery for potential treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: a narrative review. Nanomedicine (Lond). 2024 Jan 1;19(2):163-79. doi: 10.2217/nnm-2023-0267, PMID 38284393.

Yuan YG, Wang YH, Xing HH, Gurunathan S. Quercetin mediated synthesis of graphene oxide silver nanoparticle nanocomposites: a suitable alternative nano therapy for neuroblastoma. Int J Nanomedicine. 2017 Aug 16;12(16):5819-39. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S140605, PMID 28860751.

Bai X, Smith ZL, Wang Y, Butterworth S, Tirella A. Sustained drug release from smart nanoparticles in cancer therapy: a comprehensive review. Micromachines. 2022 Sep 28;13(10):1623. doi: 10.3390/mi13101623, PMID 36295976.

Niranjan R, Zafar S, Lochab B, Priyadarshini R. Synthesis and characterization of sulfur and sulphur selenium nanoparticles loaded on reduced graphene oxide and their antibacterial activity against gram-positive pathogens. Nanomaterials (Basel). 2022 Jan 7;12(2):191. doi: 10.3390/nano12020191, PMID 35055210.

Kumar A, Vaiphei KK, Singh N, Datta Chigurupati SP, Paliwal SR, Paliwal R. Nanomedicine for colon targeted drug delivery: strategies focusing on inflammatory bowel disease and colon cancer. Nanomedicine (Lond). 2024 Jun 20;19(15):1347-68. doi: 10.1080/17435889.2024.2350356, PMID 39105753.

Senapati S, Mahanta AK, Kumar S, Maiti P. Controlled drug delivery vehicles for cancer treatment and their performance. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2018 Mar 16;3(1):7. doi: 10.1038/s41392-017-0004-3, PMID 29560283.

Patel SC, Lee S, Lalwani G, Suhrland C, Chowdhury SM, Sitharaman B. Graphene-based platforms for cancer therapeutics. Ther Deliv. 2016 Jan 15;7(2):101-16. doi: 10.4155/tde.15.93, PMID 26769305.

Khramtsov PV, Rayev MB, Timganova VP, Bochkova MS, Zamorina SA. Interaction of graphene oxide nanoparticles with cells of the immune system. Genes & Cells. 2020;15(3):29-38. doi: 10.23868/202011004.

Khanikar D, Bhagawati I, Bhattacharyya M, Borah L, Ojha K, Mahanta N PP, Buragohain S. Prescription pattern of prophylactic antiemetics in breast cancer patients: a retrospective observational study in a Tertiary Care Hospital. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2023 Jun 7;16(6):34-8. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2023.v16i6.47336.

Lei Y, Zhang D, YU J, Dong H, Zhang J, Yang S. Targeting autophagy in cancer stem cells as an anticancer therapy. Cancer Lett. 2017 May 1;393:33-9. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.02.012, PMID 28216370.

Dang Y, Guan J. Nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems for cancer therapy. Smart Mater Med. 2020;1:10-9. doi: 10.1016/j.smaim.2020.04.001, PMID 34553138.

Deepika MPK, Maurya PK. Health benefits of quercetin in age-related diseases. Molecules. 2022 Apr 13;27(8):2498. doi: 10.3390/molecules27082498, PMID 35458696.

Michala AS, Pritsa A. Quercetin: a molecule of great biochemical and clinical value and its beneficial effect on diabetes and cancer. Diseases. 2022 Jun 29;10(3):37. doi: 10.3390/diseases10030037, PMID 35892731.

Pandey SK, Patel DK, Thakur R, Mishra DP, Maiti P, Haldar C. Anti-cancer evaluation of quercetin embedded PLA nanoparticles synthesized by emulsified nanoprecipitation. Int J Biol Macromol. 2015 Apr 1;75:521-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.02.011, PMID 25701491.

Wang P, Henning SM, Magyar CE, Elshimali Y, Heber D, Vadgama JV. Green tea and quercetin sensitize PC-3 xenograft prostate tumors to docetaxel chemotherapy. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2016 May 6;35(1):73. doi: 10.1186/s13046-016-0351-x, PMID 27151407.

Sun D, LI N, Zhang W, Yang E, Mou Z, Zhao Z. Quercetin loaded PLGA nanoparticles: a highly effective antibacterial agent in vitro and anti-infection application in vivo. J Nanopart Res. 2016;18(1):3. doi: 10.1007/s11051-015-3310-0.

Arasoglu T, Derman S, Mansuroglu B, Yelkenci G, Kocyigit B, Gumus B. Synthesis characterization and antibacterial activity of juglone encapsulated PLGA nanoparticles. J Appl Microbiol. 2017 Dec 1;123(6):1407-19. doi: 10.1111/jam.13601, PMID 28980369.

Guo H, Ding H, Tang X, Liang M, LI S, Zhang J. Quercetin induces pro-apoptotic autophagy via SIRT1/AMPK signaling pathway in human lung cancer cell lines A549 and H1299 in vitro. Thorac Cancer. 2021 May;12(9):1415-22. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.13925, PMID 33709560.

Liu Y, LI CL, XU QQ, Cheng D, Liu KD, Sun ZQ. Quercetin inhibits the invasion and angiogenesis of esophageal cancer cells. Pathol Res Pract. 2021 Jun 1;222:153455. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2021.153455, PMID 33962176.

Chen WJ, Tsai JH, Hsu LS, Lin CL, Hong HM, Pan MH. Quercetin blocks the aggressive phenotype of triple-negative breast cancer by inhibiting IGF1/IGF1R-mediated EMT program. J Food Drug Anal. 2021 Mar 15;29(1):98-112. doi: 10.38212/2224-6614.3090, PMID 35696220.

Sathishkumar P, LI Z, Govindan R, Jayakumar R, Wang C, Long GU F. Zinc oxide quercetin nanocomposite as a smart nano drug delivery system: molecular level interaction studies. Appl Surf Sci. 2021 Jan 15;536:147741. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2020.147741.

Jihad MA, Noori FT, Jabir MS, Albukhaty S, AlMalki FA, Alyamani AA. Polyethylene glycol functionalized graphene oxide nanoparticles loaded with Nigella sativa extract: a smart antibacterial therapeutic drug delivery system. Molecules. 2021 May 21;26(11):3067. doi: 10.3390/molecules26113067, PMID 34063773.

Toderascu LI, Sima LE, Orobeti S, Florian PE, Icriverzi M, Maraloiu VA. Synthesis and anti-melanoma activity of L-cysteine coated iron oxide nanoparticles loaded with doxorubicin. Nanomaterials (Basel). 2023 Feb 4;13(4):621. doi: 10.3390/nano13040621, PMID 36838989.

Solanki AB, Parikh JR, Parikh RH. Formulation and optimization of piroxicam proniosomes by 3-factor, 3-level box behnken design. AAPS Pharm Sci Tech. 2007 Oct 19;8(4):E86. doi: 10.1208/pt0804086, PMID 18181547.

Madupoju B, Areti A, Malothu N, Chamakuri K. Optimization characterization and in vivo hepatoprotective evaluation of NAC-loaded nanoparticles using QBD and ImageJ® software. Int J App Pharm. 2025;17(2):339-51. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2025v17i2.52384.

Al Mamoori FF, Wahab HA, Ahmad W. Synergistic effect lung cancer therapy: co-delivery of quercetin and cisplatin via eudragit l-100 nanoparticles in vitro. Int J App Pharm. 2024 Nov 7;16(6):201-10. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2024v16i6.52449.

Matiyani M, Rana A, Pal M, Rana S, Melkani AB, Sahoo NG. Polymer grafted magnetic graphene oxide as a potential nanocarrier for pH-responsive delivery of sparingly soluble quercetin against breast cancer cells. RSC Adv. 2022 Jan 19;12(5):2574-88. doi: 10.1039/d1ra05382e, PMID 35425302.

Shah J, Patel S, Bhairy S, Hirlekar R. Formulation optimization characterization and in vitro anti-cancer activity of curcumin loaded nanostructured lipid carriers. Int J Curr Pharm Sci. 2022 Jan 15;14(1):31-43. doi: 10.22159/ijcpr.2022v14i1.44110.

Rajawat S, Ramachandran B, Malik MM. Efficacy assessment of sulfated flavanol functionalized silver nanoparticles against MCF-7 breast cancer. Clin Cancer Drugs. 2025;10. doi: 10.2174/012212697X345534241121082505.

Sharma S, Narang JK, Ali J, Baboota S. Synergistic antioxidant action of vitamin E and rutin SNEDDS in ameliorating oxidative stress in a Parkinsons disease model. Nanotechnology. 2016 Sep 16;27(37):375101. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/27/37/375101, PMID 27491690.

Danaei M, Dehghankhold M, Ataei S, Hasanzadeh Davarani F, Javanmard R, Dokhani A. Impact of particle size and polydispersity index on the clinical applications of lipidic nanocarrier systems. Pharmaceutics. 2018 May 18;10(2):57. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics10020057, PMID 29783687.

Niazvand F, Orazizadeh M, Khorsandi L, Abbaspour M, Mansouri E, Khodadadi A. Effects of quercetin loaded nanoparticles on MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Medicina (Kaunas). 2019 Apr 22;55(4):114. doi: 10.3390/medicina55040114, PMID 31013662.

Bhargav E, Mohammed N, Singh UN, Ramalingam P, Challa RR, Vallamkonda B. A central composite design based targeted quercetin nanoliposomal formulation: optimization and cytotoxic studies on MCF-7 breast cancer cell lines. Heliyon. 2024 Sep;10(17):e37430. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e37430, PMID 39296160.

Kotchey GP, Zhao Y, Kagan VE, Star A. Peroxidase mediated biodegradation of carbon nanotubes in vitro and in vivo. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013 Jul 12;65(15):1921-32. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2013.07.007, PMID 23856412.