Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 4, 2025, 299-308Original Article

FORMULATION AND EVALUATION OF TOPICAL TRANSFEROSOMES LOADED LIDOCAINE FOR TOPICAL DELIVERY FOR BURNS, IN VITRO CHARACTERIZATION AND IN VIVO STUDY

SARMAD DHEYAA NOORI1*, SAMER KHALID ALI2, MUSTAFA MUDHAFAR3,4, HASAN ALI ALSAILAWI5,6, AMIRA B. KASSEM7

1College of Pharmacy-Al-Ayen Iraqi University, Thi-Qar, Iraq. 2Department of Pharmaceutics College of Pharmacy-Al-Ayen Iraqi University, Thi-Qar, Iraq. 3Department of Medical Physics, Faculty of Medical Applied Sciences, University of Kerbala-56001, Karbala, Iraq. 4Department of Anesthesia Techniques and Intensive Care, Al-Taff University College-56001, Kerbala, Iraq. 5Department of Basic Science, Faculty of Dentistry, University of Kerbala-56001, Karbala, Iraq. 6Department of Anesthesia Techniques, AlSafwa University College, Karbala, Iraq. 7Department of Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacy Practice. Faculty of Pharmacy, Damnhour University

*Corresponding author: Sarmad Dheyaa Noori; *Email: sarmaddheyaa@gmail.com

Received: 28 Jan 2025, Revised and Accepted: 21 May 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: The current investigation aimed for loading Lidocaine (LID), a local anesthetic agent, into transferosomes topically. Lidocaine has substantial first-pass metabolism results in low oral bioavailability. In order to prevent oral complications, the production of LID transferosomes was to improve LID topical distribution.

Methods: By using a 21.31 factorial design and different amounts lipids and surfactants, transferosomes formulas were created. LID transferosomes were constructed applying ethanol injection method. LID transferosomes were evaluated with regard to entrapment efficiency percent (EE%), particle size (PS), polydispersity index (PDI), and zeta potential (ZP). Extra experiments were conducted on the optimum formula.

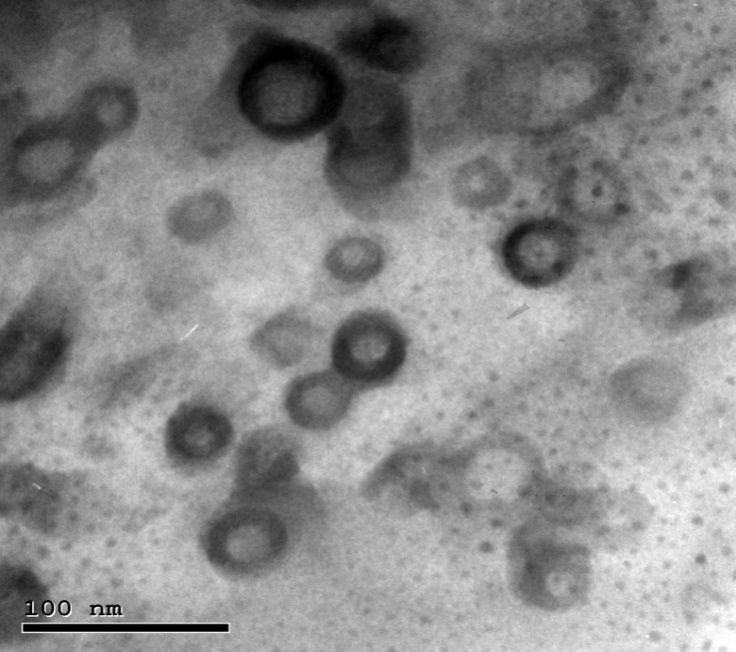

Results: Utilizing Design Expert®, the optimum formula (F2) was evaluated, revealing EE% of 90.25±1.23%, PS of 194.50±6.50 nm, PDI of 0.602±0.0005, ZP of 50.45±1.15 mV, and amount of drug release after 6 h (Q6h) of 45.00±1.50. Further, the optimum transferosomes showed vesicles without aggregation under transmission electron microscope evaluation. In vitro release study showed that the optimum formula was released in sustained manner than LID solution. In addition, during storage, the optimum formula was stable. The histological investigation verified the safety of the optimum transferosomes.

Conclusion: The results confirmed the ability to utilize LID transferosomes for burn treatment topically.

Keywords: Lidocaine, Topical, Factorial design, Transferosomes, Histopathological study

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i4.53805 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

One of the most excruciating and serious injuries that may occur to a person is a burn. The most difficult thing for patients to deal with while recovering from a burn is the pain of repeated therapeutic operations like skin debridement and grafting. Although the procedure discomfort is brief, it is quite severe [1].

Local anesthetics are a natural candidate for localized prohibiting in wound care operations and have been utilized as topical gels or intravenous infusions to relieve burn pain. There are no discernible negative effects on healing when Lidocaine (LID) (1 mg/kg) is administered topically to wounds. This has been shown to greatly reduce analgesic intake and acute and postoperative pain. Strong anti-inflammatory properties of LID may make it advantageous to apply it to a wound site when changing a dressing [2].

LID is frequently used as an anesthetic in intravenous injection to relieve and prevent pain during certain medical procedures. Additionally, it is utilized in clinics as a vasoconstrictor in topical treatments or as an antiarrhythmic medication to treat ventricular arrhythmias, particularly ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation [3].

For topical drug delivery systems, LID in pastes, creams, and ointments is the safest and most practical form of treatment. However, the primary drawback of these systems is that they are quickly eliminated by wetness, movement, and touch. Therefore, for topical administration, a new formulation method incorporating nanocarriers and improved local anesthetic effects is sought [4].

Moreover, for topical or transdermal medication delivery, the skin serves as both a primary target and a barrier. Notwithstanding the system's numerous advantages, the main encounter is the slow rate at which medications distribute through the stratum corneum. A number of techniques have been evaluated to temporarily boost the rate of drug penetration. Applying medications in formulation with skin enhancers or elastic vesicles is an easy and practical method. Elastic vesicles can be divided into two categories: surfactant-based and phospholipid-based (Transfersomes and Ethomomes). In terms of quantity and depth, elastic vesicles were more effective at delivering both high and low-molecular-weight drugs to the skin. Their physicochemical characteristics-composition, duration, and application volume, as well as entrapment efficiency and application techniques-have a significant impact on their efficacy [5].

Phospholipid (PC) vesicles with an aqueous compartment enclosed by one or more lipid bilayers are known as liposomes. Numerous studies instead link topical medication delivery to liposomes. Cevc et al. presented a novel class of liposomes called transferosomes as a drug delivery vehicle made of a PC Bilayer and Surfactant (SAA) [6]. SAA gives the produced vesicles flexibility, which reduces their likelihood of rupturing, particularly when given topically. Both hydrophilic and hydrophobic components found in transferosomes can surround medicinal molecules with a variety of solubility levels. Without suffering any discernible loss, they may squeeze through the small opening, which is five to ten times smaller than their own diameter. Better vesicle penetration is provided by this great deformation ability. Furthermore, the presence of SAA in the vesicles may cause the lipid and protein packing inside the SC to be disturbed [7].

When the Quality by Design (QbD) method was implemented, production procedures were improved, and the final goods' quality and safety were guaranteed. After the release of the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) guidelines, the food and drug administration authorized QbD. The ICH guideline, for example, describes QbD as a method that establishes the process's starting goals, promotes knowledge and control, and controls threats to the quality of the end output. Thus, QbD makes it possible to produce pharmaceutical items that are both safe and of excellent quality. Research on nanosystems has sparked a medical technology revolution in recent decades, with multiple researchers using QbD to create medication nano-delivery systems. By integrating final product quality criteria connected to clinical performance, avoiding variability, enhancing process design, increasing manufacturing efficiency, and allowing post-approval modifications management, QbD streamlines and lowers production procedures in this case [8].

A full factorial design is a factorial experiment that includes every possible combination of the selected factors and levels. This design is a powerful instrument that, in contrast to other experimental designs, offers the most thorough understanding of the behavior of the system since it takes into account the impacts of all components (major effects) and their interactions [8]. If the total number of runs equals nk since all components k have the same number of levels n. The number of experimental runs increases significantly as the number of factors and levels increases. This results in significant expenses and time commitments for traditional experiments. The response quantity variation, however, can be explained, broken down, and ascribed to every potential cause because of the vast variety of combinations, giving an almost accurate representation of the procedure. Because of the nature of factorial designs, their outcomes can be used as useful benchmarks for discussing how well other designs perform in the characterization [9].

Thus, the goals of the present investigation were to evaluate the safety of LID transferosomes applied topically as well as the possibility that it might raise LID for topical use for sustained treatment of burns. In order to do that, many factors affecting the features of LID transferosomes were investigated using full factorial 21.31experimentusing Design Expert® to determine the optimum formula. EE% (Y1), PS (Y2), and PDI (Y3) were chosen as dependent factors, and PC amount (X1) and SAA type (X2) were examined as independent variables. The optimum LID transferosomes were further assessed in terms of stability and shape. Furthermore, histopathology studies of LID from the optimum LID transferosomes were conducted using male Wistar rats.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Lidocaine (LID), Phospholipid (PC) from soya bean, Pluronic 121, Pluronic 123 and Pluronic F127 were bought from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, USA). Ethanol, and methanol were obtained from El-Nasr Pharmaceutical (Cairo, Egypt).

Methods

Preparation of lidocaine transferosomes

By applying the ethanol injection method (due to the excellent solubility of drug and phospholipid, and SAA in ethanol), three SAA (10 mg) Pluronic 121, Pluronic 123, and Pluronic f127and two concentration of PC (100, and 200 mg) were combined to create the LID transferosomes. Firstly, 10 mg of LID were added to 10 ml water. After that lipid and SAA were dissolved into ethanol (2 ml) at 60 ℃. Finally, the organic phase was injected to the aqueous phase slowly and mixed using magnetic stirrer at 800 RPM; to obtain mature vesicles, the vesicles were kept at 4 °C [10].

Characterization of lidocaine transferosomes

Entrapment efficiency ratio (EE%)

The LID transferosomes for the developed formulations was centrifuged at 20,000 rpm for 1 hour at 4 °C using a centrifuge (Sigma, Germany). The entrapped drug was then lysed in methanol and assessed at λmax 228 nm using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Japan) [11], EE% was found using the direct technique [12].

Particle size (PS), polydispersity index (PDI) and zeta potential (ZP)

Using a Malvern Zetasizer, the PS, PDI, and ZP of the LID transferosomes were estimated for the generated formulae [13]. Following dilution (ten folds), the measurements were carried out. The scattering angle was 90°, with laser’s obscuration range was 10 to − 0%. Every measurement was done three times [14].

Assessment of the impact of formulation constraintsapplying21.31 factorial design

Applying the lowest experimental runs, a 21.31 factorial design was employed to determine the impact of several factors on the aspects of LID transferosomes [15]. Two factors were assessed: one had two levels (X1: PC amount), and the other had three levels (X2: SAA type). As dependent variables, the EE% (Y1), PS (Y2), and PDI (Y3), were identified (table 1). To create LID transferosomes, all probable combinations were tested in the experiments (table 1). The experimental data were inspected using Design Expert® (Stat Ease, USA) to independently source the impacts of these components, and then analysis of variance was used to assess the significance at 95% confidence level.

Table 1: 21.31Factorial-design for optimization of LID transferosomes

| Factors | Levels |

| X1: PC amount (mg) | 100200 |

| X2: Pluronic type | P121 P123 PF127 |

| Responses | |

| Y1: EE (%) | Maximize |

| Y2: PS (nm) | Minimize |

| Y3: PDI | Minimize |

| Y4: ZP | Maximize |

Optimization of lidocaine transferosomes

To determine which formulation should be selected for further investigation, the desirability function was established. This function predicts the optimal levels of selected components. Selecting the optimal formulation requires meeting specific criteria, including achieving the lowest PS and PDI and the maximum EE%, and ZP.

Determination of the amount of drug release

The amount of medication released was measured for six hours at 37 °C using the USP dissolution tester equipment II. The optimal LID transferosomes of (2 ml samples) were added into plastic cylindrical as donor compartment and sealed with cellulose membrane with surface area of 3.14 cm2, that contained 5 mg of LID. The formulations were immersed in 50 milliliters of pH 5.5 phosphate buffer release medium [7]. In this volume, the sink state was preserved. Aliquots were removed every hour up to 6 h. A UV spectrophotometer with a λmax of 228 nm was used to evaluate aliquots (1 ml) of LID. Three experiments were carried out.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

Using a Joel JEM 1230 transmission electron microscope (Tokyo, Japan), the optimal formula morphology was examined. A thin layer of the nanodispersion was applied to a grid covered with carbon, dyed, then observed, and photographed [16].

Effect of short-term storage

For forty-five days, the ideal LID transferosomes were kept at 4 °C. At 0 and 45 d, samples from each formulation were taken out. Comparing the initial measurements with the values acquired afterwards storage allowed for the evaluation of stability. As previously mentioned, measurements of the EE%, PS, PDI, ZP, and Q6h(%) from the LID transferosomes were made. Statistical significance was analyzed by Student’s t-test [17].

pH assessment

The pH of the optimum LID transferosomes was estimated, by a calibrated pH meter (Hanna, Romania).

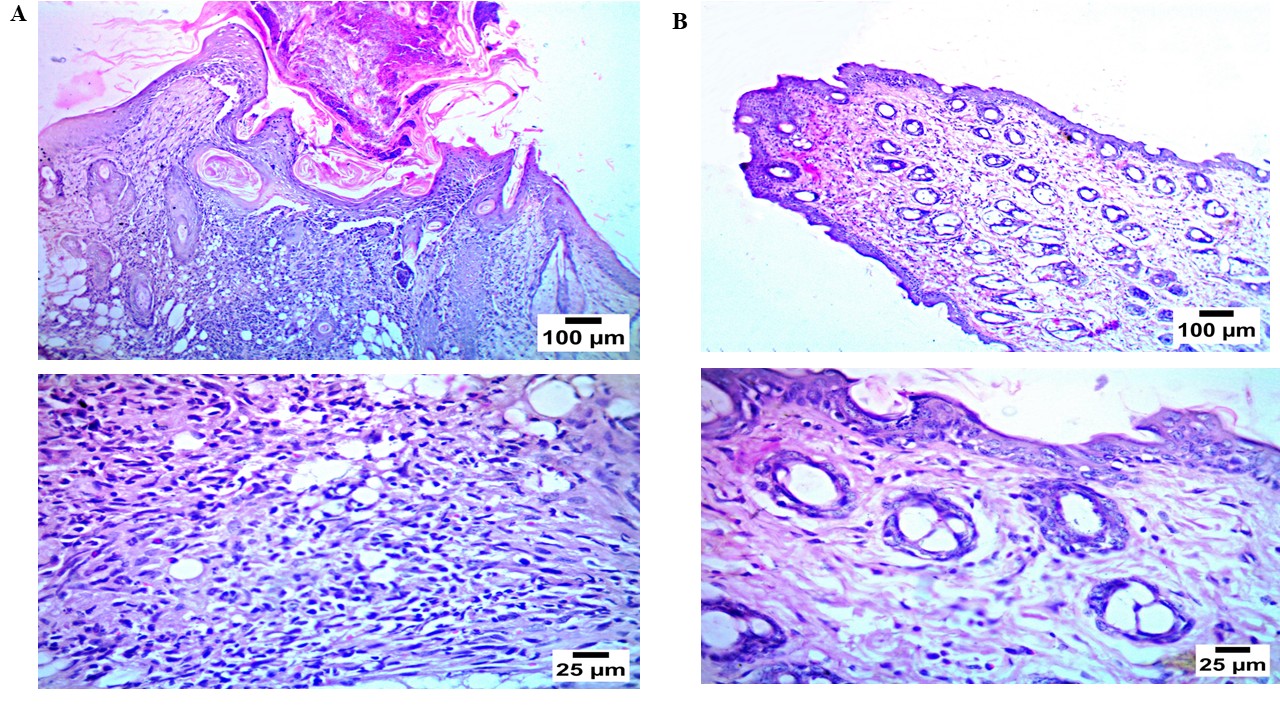

Histopathological study

The study design was authorized by the ethical committee of the Al-Ayen University College (AUIQ-REC-A24001). Six animals supplied by Al-Ayen university animal house were divided into two groups where groups one behaved as control left untreated, while group two was treated with the optimum LID transferosomes. The rats were provided with water and a standard diet, at 22 °C, 55% humidity, and a cycle of 12 h dark followed by 12 h light. Rats remained to adapt for 7 d. The treatment lasted one day. After being fixed for 24 h in 10% formol saline, skin samples were cleaned, and alcohol was used to dehydrate them. Following a 24 h period at 56 °C, the specimens were cleaned, imgded blocks, and sectioned using a microtome (Leica, USA) at a thickness of 4 mm for each skin sample. Using light microscopy, the specimens were deparaffinized and stained with hematoxylin and eosin, for histological analysis. (Axiostar plus, Zeiss, New York) [18].

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Analysis of factorial design

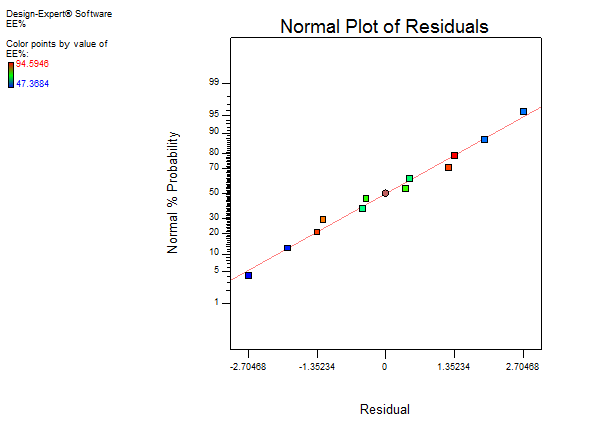

Two independent variables were investigated: the PC amount (X1) and SAA type (X2); dependent variables included EE% (Y1), PS (Y2), PDI (Y3), and ZP (Y4). The experimental results were evaluated using Design Expert® to trace independently the effects of these factors, which were then evaluated employing ANOVA to decide the significance of each factor. The two-factor interaction (2 FI) model was utilized, and it was seen that the predicted R2 values were in agreement with the adjusted R2 in all responses, with reference to the design analysis results in table 2. Adequate precision is employed to confirm that the model could be utilized throughout the design space; it is worth noting that all responses showed adequate precision with a ratio superior to 4. The degree of freedom and F values have been supplied in table 3.

EE%

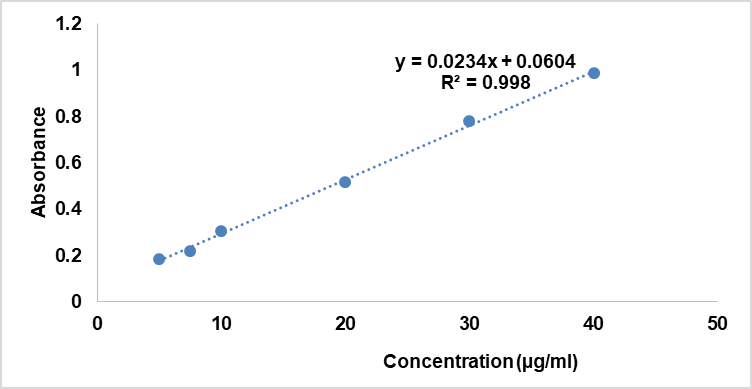

The authors utilized a validated method, using UV-Vis spectrophotometry for calculating the entrapped drug in EE% calculation (table 5, and fig. 1).

Table 2: Data of the 21.31 factorial analysis of lidocaine transferosomes

| Responses | EE% | PS (nm) | PDI | ZP (mV) |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.9916 | 0.964 | 0.915 | 0.912 |

| Predicted R2 | 0.9847 | 0.922 | 0.814 | 0.808 |

| Adequate precision | 27.512 | 18.01 | 12.05 | 13.34 |

| Significant factors | X1 | X1, X2 | X1 | X1, X2 |

| Predicted value of optimum formula (F2) | 90.2595 | 194.5 | 0.602 | -50.45 |

| Observed value of optimum formula (F2) | 90.25 | 194.50 | 0.602 | -50.45 |

Table 3: Degree of freedom and F values for all responses

| Degree of freedom | X1:PC amount (mg) | X2:SAA amount (mg) |

| EE% F value | 558.1 | 1.07 |

| EE% Degree of freedom | 1 | 2 |

| PS F value | 32.67 | 126.45 |

| PS Degree of freedom | 1 | 2 |

| PDI F value | 5.87 | 39.24 |

| PDI Degree of freedom | 1 | 2 |

| ZP F value | 15.54 | 32.98 |

| ZP Degree of freedom | 1 | 2 |

Table 4: Experimental runs of the 21.31factorial design

| PC amount (mg) | SAA type | EE% | PS (nm) | PDI | ZP (mV) | |

| F1 | 100 | P121 | 50.60±1.93 | 113.80±1.60 | 0.682±0.031 | -41.70±0.01 |

| F2 | 200 | P121 | 90.25±1.23 | 194.50±6.50 | 0.602±0.0005 | -50.45±1.15 |

| F3 | 100 | P123 | 50.07±2.70 | 185.50±45.50 | 0.454±0.004 | -42.40±1.20 |

| F4 | 200 | P123 | 93.24±1.35 | 419.55±28.85 | 0.468±0.035 | -41.35±0.15 |

| F5 | 100 | P127 | 65.32±0.46 | 530.15±20.25 | 0.527±0.027 | -39.10±0.001 |

| F6 | 200 | P127 | 73.39±0.39 | 560.80±18.40 | 0.728±0.012 | -39.35±1.25 |

Notes: Data given in mean±SD

Fig. 1: Calibration curve

Table 5: LID calibration curve

| Conc (μg/ml) | Abs |

| 5 | 0.185 |

| 7.5 | 0.2181 |

| 10 | 0.306 |

| 20 | 0.516 |

| 30 | 0.7803 |

| 40 | 0.987 |

It is possible to create multilayered nanosystems into an efficient drug delivery system for the targeted or controlled release of lipophilic medicines. Encapsulating bioactive inside PC containing formulations offers the best distribution, improved stability, and permeability based on the lipid composition and characteristics [19].

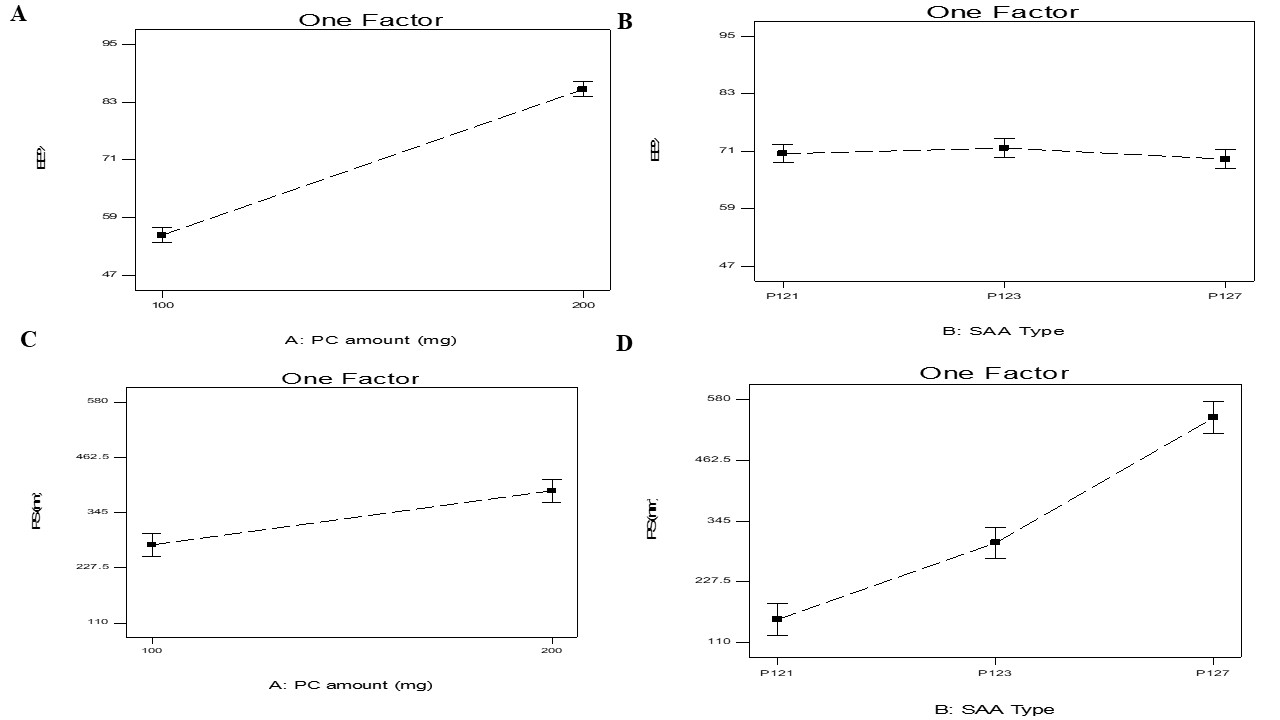

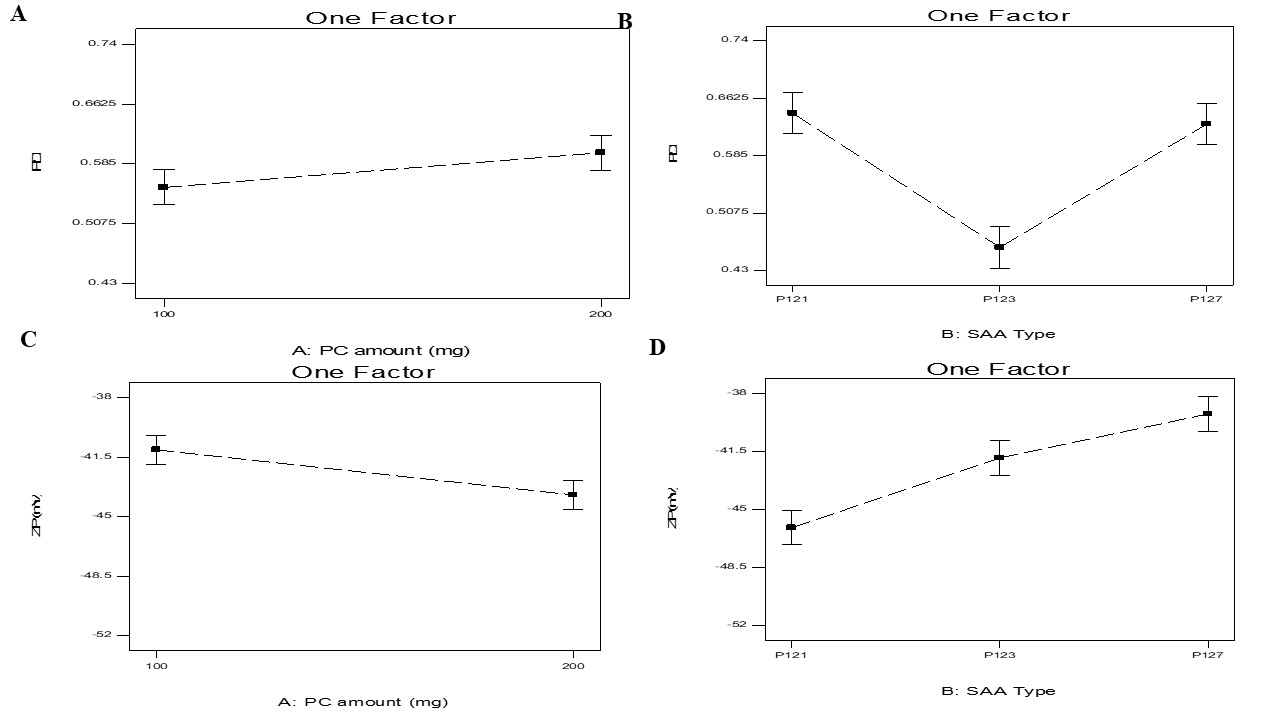

The effect of the independent variables, PC amount (X1) and SAA type (X2) on the EE% of LID transferosomes is shown in table 2,3 and is illustrated in fig. 2A-B. EE% ranged from 50.60±1.93 to 93.24±1.35% table 4.

The polynomial equation for EE% is: EE+70.50+15.13 * A-0.020* B[1]+1.16* B[2]+4.65* AB[1]+6.45* AB[2]

It was found high PC amount produced significantly (p<0.0001) larger EE% values than the smaller amounts of PC. At high PC amounts there would be sufficient space for drug loading compared to lower amounts of PC [7].

Considering SAA type (X2) (p=0.399), it has no significant effect on EE% with p values of 0.399.

Fig. 2: Effect of PC amount (X1) and SAA type (X2) on EE%, and PS on transferosomes

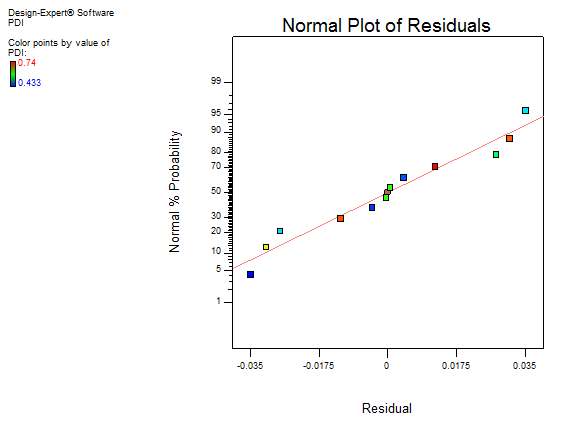

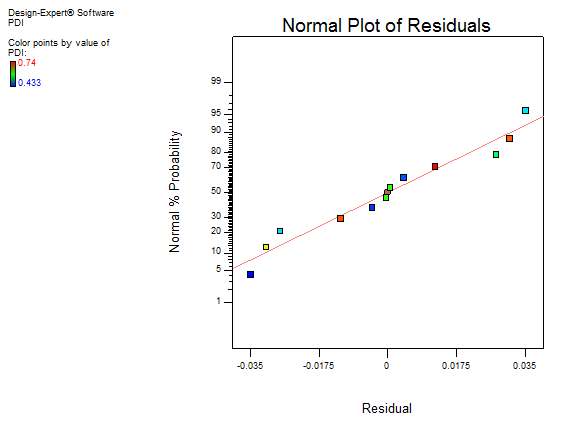

Fig. 3: Residual fig. for on EE%

PS

The mean hydrodynamic diameter of the particles is indicated by the z-average diameter [20] was measured and presented in table 2,3 and illustrated in fig. 2B. The PS of the nano-system might affect the degree of drug deposition as well as skin penetration [21]. PS ranged from 113.80±1.60 to 560.80±18.40 nm.

It is noticeable that both PC amount (X1) and SAA type (X2), significantly influenced the PS of the vesicles with p values of 0.0013 and (p<0.0001), respectively.

The polynomial equation of PS was as follows:

PS (nm)=+334.05+57.57* A-179.90* B[1]-31.53* B[2]-17.22* AB[1]+59.46 * AB[2]

For PC amount (X1), it was found that larger PS was produced by using higher amounts of PC compared to smaller amounts of PC. This could be related to higher PC amount the viscosity of the system increased, hence increased the PS [15]. Further, it was also detected from the results that the PS was in agreement with the amount of drug entrapped in the nanosystems. Consequently, the increase in EE% would give justification for the larger PS of vesicle [22].

For SAA type (X2), it was observed that PS augmented in the subsequent order P121<P123<P127; this could be related to SAA hydrophilicity, as the hydrophilicity of SAA increased the PS increase. Aziz et al. stated by increasing SAA hydrophilicity led to increasing the water content in the nanosytems with resultant increase in PS [18].

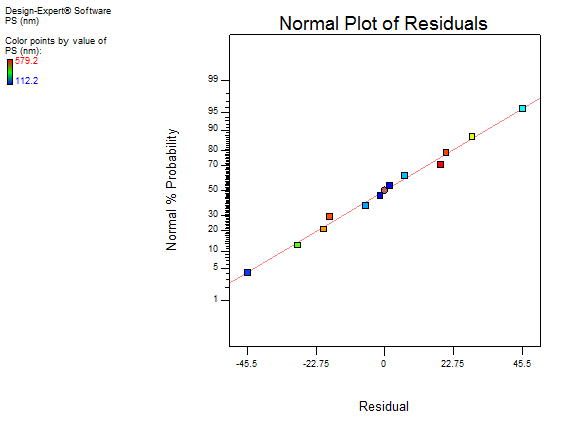

Fig. 4: Residual fig. for PS

Fig. 5: Effect of phospholipid (X1) and SAA type (X2) on PDI and ZP on SLNs-phospholipid complex

PDI

The width of unimodal size distributions is measured by the PDI. Further, PDI was measured and presented in table 2,3 and fig. 5 A-B. PDI ranged from 0.454±0.004 to 0.728±0.012. A homogeneous dispersion shows a value of 0, whereas a completely heterogeneous polydisperse population is indicated by a value of 1. A PDI that is considered acceptable should be less than 0.5. The produced vesicles' polydispersity indices were often minimal, as can be seen from the data, indicating strong homogeneity and a narrow size distribution [23].

The polynomial equation for PDI is:

PDI =+0.58+0.022* A+0.065* B [1]-0.12* B[2]-0.062* AB[1]-0.015* AB[2]

Factorial analysis displayed that only SAA type (X2) showed significant effect on PDI (p=0.0004), P127 produced the biggest PDI then P123, and finally P121. The previous outcomes showed agreement of PS results with PDI values; as the PS of transferosomes increased PDI subsequently increased this was described previously in literature [7].

Fig. 6: Residual fig. for PDI

ZP

ZP ranged from-39.10±0.001to-50.45±1.15 mV. For electrostatic causes, particles with (≥|15|mV) are expected to be stable due to steric reasons [24]. The negative charge present in transferosomes formulae was due to presence of PC carrying negative charge [25].

ZP was measured and presented in table 2,3 and illustrated in (fig. 5C-D). It is noticeable that both phospholipid amounts (X1) and SAA type (X2) significantly influenced the PS of the vesicles with p values of 0.0088 and 0.006, respectively.

The polynomial equation for ZP was as follows:

ZP (mV) =-42.39-1.32* A-3.68* B [1]+0.52* B[2]-3.05* AB[1]+1.85* AB[2]

For PC amount (X1), it was found that increasing the amount of PC increased ZP. It was expected that in a low ionic strength media, the polar head group is oriented in a manner that the negatively charged phosphatidyl is directed to the out while the positively charged choline group is located to the inside, producing a negative charge. Hence by increasing the phospholipid amount, the negative phosphatidyl group would increase [26].

For SAA type, it was found that SAA that produced the smallest transferosomes produced the highest ZP values of vesicles due to its ability to prevent the aggregation and sedimentation, subsequently produced stable vesicles [27].

Selection of the optimized formulation

A set of criteria was first established in the Design Expert® (Stat Ease, USA) to choose the best formula. Particles having the highest EE%, and lowest PS and PDI were given preference according to these parameters. The primary effects of these parameters were separately found through the use of Design Expert® to examine the experimental data. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was then performed to ascertain the importance of each element. The formula that satisfied the predetermined criteria was the best one. The optimum LID transferosomes (F2) had EE% of 90.25±1.23%, PS of 194.50±6.50 nm, PDI of 0.602±0.0005, and ZP of-50.45±1.15 mV. The expected and observed responses of were compared and are displayed in table 2 to verify the validity of our experiment. There was a strong correlation found between the actual and anticipated values for the optimum formula F2 that is composed of 200 mg phospholipid and P121.

Characterization of the optimum formula

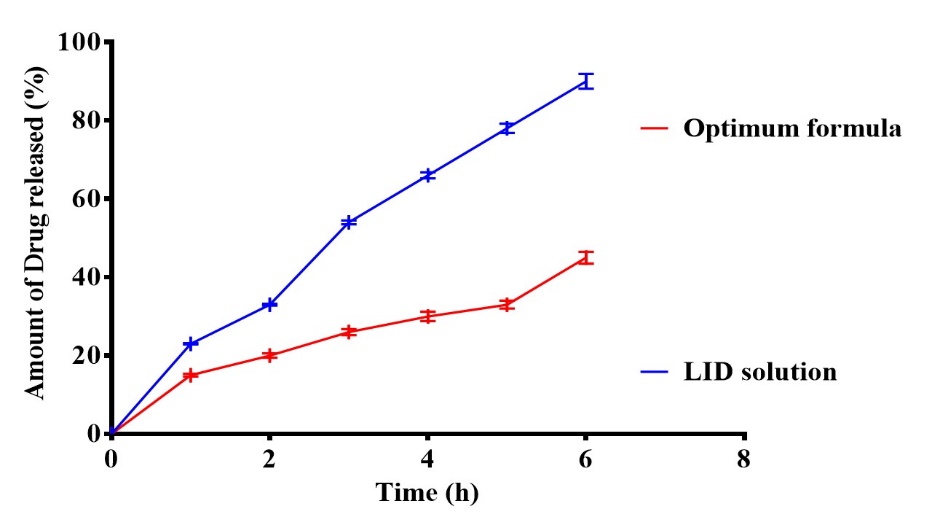

In vitro drug release

Regarding the saturated solubility of LID, the utilization of phosphate buffer pH (5.5) (maintained sink condition and the saturated solubility was 5.33 greater folds than the aqueous solubility of LID. Subsequently pH 5.5 was selected as proper medium for in vitro release.

When expecting a drug's in vivo performance, the release profile is a crucial indicator [28]. High surface area and a faster rate of disintegration are the outcomes of PS decrease [29]. Q6h for the optimum LID transferosomes (F2) and LID solution are displayed in fig. 8. Additionally, the results indicated that the optimum LID transferosomes contains phospholipids that provide a significant (P=0.001) slower release percentage compared to LID solution. The release profile of the optimum LID transferosomes proved that transfersomes successfully sustain the release over 6 h. Moreover, it is a hopeful approach to deliver LID with a reduced frequency of administration, which would reduce side effects and enhance the management of burns [30]. From fig. 3 it was noticeable the release from F2 was fast then significantly (p = 0.01) slower in a prolonged way associated to LID solution as lidocaine was entirely released from LID solution after 1 h. The aforementioned results might be related to, firstly: LID is hydrophilic; therefore its hydrophilic characteristics results in better release from LID solution. Further, the existence of PC make a drug-PC complex inside the transferosomes, which propose the opportunity of constantly releasing LID in a persistent way from transferosomes that proposes a store for pain management in burns.

It is worth observing that the drug solution follows first follows first order kinetics with R2 of 0.9827, while it follows diffusion model for nano formula with R2 of 0.9928.

Fig. 7: Residual fig. for ZP

Fig. 8: In vitro drug release for LID and the optimum formula (F2), Notes: Data given in mean

Fig. 9: Transmission electron micrograph for the optimum LID transferosomes

Morphology of vesicles

TEM analysis confirmed that LID-transferosomes exhibited a uniform morphology with no observable aggregation. The morphological shape revealed that they were spherical and had a consistent size distribution (fig. 9). The Zetasizer-determined LID transferosomes PS correlated with TEM-PS evaluation.

Effect of storage

During storage, lipid nanoparticles formulations have a tendency to fuse and disintegrate, changing PS, PDI, and ZP. Additionally, these modifications result in a decrease in the EE% and medication leakage from the vesicles [31]. LID transferosomes (F2) were visually inspected for aggregation and appearance changes. Furthermore, it was determined what EE% of 89.15±0.93%, PS of 199.60±1.50 nm, PDI of 0.612±0.01, and ZP of-51.34±2.05 mV, and Q6h(%) of 92.00 ±0.07%. After 45 d at 4 °C, statistical analysis showed that there was no significant change between the fresh and preserved transferosomes in terms of EE%, PS, PDI, ZP and Q6h(%) with p values of 0.79, 0.86, 0.32, 0.06, and 0.67 respectively. These results suggest that the ideal optimum transferosomes are stable.

pH measurement

The inspected pH assessments for optimum LID transferosomes ranged from 4.980±0.31 to 5.77±0.34, which is suitable for skin [26].

Histopathological study

Permeation enhancers are thought to be a key barrier to topical delivery due to skin irritation [32]. When related to untreated skin (group I), examination of group II which were treated with the optimum LID transferosomes, respectively, revealed no histological changes in epidermal and dermal cells (fig. 10). These results showed that the optimum LID transferosomes formulation had a tolerable level of acceptability.

Fig. 10: Histopathological study for the optimum LID transferosomes(F2) (b) compared to the negative control (a)

Table 6: Score (inflammatory cell count)

| Control group | LID transferosomes |

| 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 |

| 0 | 1 |

CONCLUSION

In this study, we developed lidocaine transferosomesas a topical lidocaine delivery drug for enhancing pain-related wounds. In accordance with the factorial design, six formulations were created using the thin ethanol injection process. These formulations were then utilized to choose the best nano-formula, which had spherical morphology, a good drug EE%, minimal PS, and good ZP values. The optimum formula was stable during storage period. The in vitro release study confirmed the sustained release of lidocaine from the optimum formula. Additionally, the in vivo histological investigation verified that optimum formula did not cause irritation when applied to rat skin. The findings therefore, indicated that since lidocaine transferosomes applied topically without any irritation, it could be regarded as a potential topical administration strategy. Further, it was assumed that topical application of the optimum transferosomes lidocaine might contribute to enhance healing, improved histological improvement and decreased scar formation. In addition, the authors recommended ex vivo skin penetration studies, pharmacokinetic evaluation or in vivo efficacy studies in burn models to prove that lidocaine transferosomes are therapeutically effective in humans.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization, Sarmad dheyaa noori, samerkhalid ali, Mustafa Mudhafar, Hasan Ali ALsailawi, and Amira B kassem. Formal analysis, Sarmad dheyaa noori, samerkhalid ali, Mustafa Mudhafar, Hasan Ali ALsailawi, and Amira B kassem. Investigation, Sarmad dheyaa noori, samerkhalid ali, Mustafa Mudhafar, Hasan Ali ALsailawi, and Amira B kassem. Resources Writing-original draft preparation, Sarmad dheyaa noori, samerkhalid ali, Mustafa Mudhafar, Hasan Ali ALsailawi, and Amira B kassem. Writing—review and editing, Sarmad dheyaa noori, samerkhalid ali, Mustafa Mudhafar, Hasan Ali ALsailawi, and Amira B kassem. Supervision, Amira B kassem. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors report no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

Summer GJ, Puntillo KA, Miaskowski C, Green PG, Levine JD. Burn injury pain: the continuing challenge. J Pain. 2007;8(7):533-48. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.02.426, PMID 17434800.

Desai C, Wood FM, Schug SA, Parsons RW, Fridlender C, Sunderland VB. Effectiveness of a topical local anaesthetic spray as analgesia for dressing changes: a double-blinded randomised pilot trial comparing an emulsion with an aqueous lidocaine formulation. Burns. 2014;40(1):106-12. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2013.05.013, PMID 23810271.

Verdugo Escamilla C, Alarcon Payer C, Acebedo Martinez FJ, Fernandez Penas R, Dominguez Martin A, Choquesillo Lazarte D. Lidocaine pharmaceutical multicomponent forms: a story about the role of chloride ions on their stability. Crystals. 2022;12(6):798. doi: 10.3390/cryst12060798.

Omar MM, Hasan OA, Sisi El AM. Preparation and optimization of lidocaine transferosomal gel containing permeation enhancers: a promising approach for enhancement of skin permeation. Int J Nanomedicine. 2019 Feb 26;14:1551-62. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S201356, PMID 30880964.

Choi MJ, Maibach HI. Elastic vesicles as topical/transdermal drug delivery systems. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2005;27(4):211-21. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2494.2005.00264.x, PMID 18492190.

Home page J, Arana K. Advances in nanotechnology and their applications. Int J Pharm. 2022;12(1):4. doi: 10.37532/2249-1848-22.12.04.

Albash R, Abdelbary AA, Refai H, El Nabarawi MA. Use of transethosomes for enhancing the transdermal delivery of olmesartan medoxomil: in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo evaluation. Int J Nanomedicine. 2019 Mar 15;14:1953-68. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S196771, PMID 30936696.

Cunha S, Costa CP, Moreira JN, Sousa Lobo JM, Silva AC. Using the quality by design (QbD) approach to optimize formulations of lipid nanoparticles and nanoemulsions: a review. Nanomedicine. 2020 Aug;28:102206. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2020.102206, PMID 32334097.

Jankovic A, Chaudhary G, Goia F. Designing the design of experiments (DOE) an investigation on the influence of different factorial designs on the characterization of complex systems. Energy Build. 2021 Nov 1;250:111298. doi: 10.1016/j.enbuild.2021.111298.

Albash R, Badawi NM, Hamed MI, Ragaie MH, Mohammed SS, Elbesh RM. Exploring the synergistic effect of bergamot essential oil with spironolactone loaded nano-phytosomes for treatment of acne vulgaris: in vitro optimization in silico studies and clinical evaluation. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2023;16(1):128. doi: 10.3390/ph16010128, PMID 36678625.

Albash R, Ragaie MH, Hassab MA, El Haggar R, Eldehna WM, Al Rashood ST. Fenticonazole nitrate loaded trans novasomes for effective management of tinea corporis: design characterization in silico study and exploratory clinical appraisal. Drug Deliv. 2022;29(1):1100-11. doi: 10.1080/10717544.2022.2057619, PMID 35373684.

Refai H, El Gazar AA, Ragab GM, Hassan DH, Ahmed OS, Hussein RA. Enhanced wound healing potential of spirulina platensis nanophytosomes: metabolomic profiling molecular networking and modulation of HMGB-1 in an excisional wound rat model. Mar Drugs. 2023;21(3):149. doi: 10.3390/md21030149, PMID 36976198.

J Sheikh AA, Giri AJ, Sheikh A, Kale R, Biyani K. Nanocrystal technology characterization and pharmaceutical applications. Int J Pharm. 2021;11(11):7-12.

Mohamed HR, El Shamy S, Abdelgayed SS, Albash R, El Shorbagy H. Modulation efficiency of clove oil nano emulsion against genotoxic oxidative stress and histological injuries induced via titanium dioxide nanoparticles in mice. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):7715. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-57728-1, PMID 38565575.

Albash R, Abdellatif M, Hassan M, M Badawi N. Tailoring terpesomes and leciplex for the effective ocular conveyance of moxifloxacin hydrochloride (comparative assessment): in vitro, ex-vivo, and in vivo evaluation. Int J Nanomedicine. 2021 Aug 3;16:5247-63. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S316326, PMID 34376978.

Eltabeeb MA, Hamed RR, El Nabarawi MA, Teaima MH, Hamed MI, Darwish KM. Nanocomposite alginate hydrogel loaded with propranolol hydrochloride kolliphor® based cerosomes as a repurposed platform for methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (mrsa) induced skin infection; in vitro, ex vivo, in silico, and in vivo evaluation. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2025;15(2):556-76. doi: 10.1007/s13346-024-01611-z, PMID 38762697.

Teaima MH, Eltabeeb MA, El Nabarawi MA, Abdellatif MM. Utilization of propranolol hydrochloride mucoadhesive invasomes as a locally acting contraceptive: in vitro ex-vivo, and in vivo evaluation. Drug Deliv. 2022;29(1):2549-60. doi: 10.1080/10717544.2022.2100514, PMID 35912869.

Aziz DE, Abdelbary AA, Elassasy AI. Investigating superiority of novel bilosomes over niosomes in the transdermal delivery of diacerein: in vitro characterization ex vivo permeation and in vivo skin deposition study. J Liposome Res. 2019;29(1):73-85. doi: 10.1080/08982104.2018.1430831, PMID 29355060.

Mendes AC, Gorzelanny C, Halter N, Schneider SW, Chronakis IS. Hybrid electrospun chitosan phospholipids nanofibers for transdermal drug delivery. Int J Pharm. 2016;510(1):48-56. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2016.06.016, PMID 27286632.

Ezzat SM, Salama MM, ElMeshad AN, Teaima MH, Rashad LA. HPLC–DAD–MS/MS profiling of standardized rosemary extract and enhancement of its anti-wrinkle activity by encapsulation in elastic nanovesicles. Arch Pharm Res. 2016;39(7):912-25. doi: 10.1007/s12272-016-0744-6, PMID 27107862.

Roberts MS, Mohammed Y, Pastore MN, Namjoshi S, Yousef S, Alinaghi A. Topical and cutaneous delivery using nanosystems. J Control Release. 2017 Feb 10;247:86-105. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.12.022, PMID 28024914.

Hathout RM, Elshafeey AH. Development and characterization of colloidal soft nano carriers for transdermal delivery and bioavailability enhancement of an angiotensin II receptor blocker. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2012;82(2):230-40. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2012.07.002, PMID 22820090.

Salama AH, Aburahma MH. Ufasomes nano vesicles based lyophilized platforms for intranasal delivery of cinnarizine: preparation optimization ex vivo histopathological safety assessment and mucosal confocal imaging. Pharm Dev Technol. 2016;21(6):706-15. doi: 10.3109/10837450.2015.1048553, PMID 25996631.

Sun Z, Nicolosi V, Rickard D, Bergin SD, Aherne D, Coleman JN. Quantitative evaluation of surfactant stabilized single-walled carbon nanotubes: dispersion quality and its correlation with zeta potential. J Phys Chem C. 2008;112(29):10692-9. doi: 10.1021/jp8021634.

Albash R, Abdelbari MA, Elbesh RM, Khaleel EF, Badi RM, Eldehna WM. Sonophoresis mediated diffusion of caffeine loaded transcutol® enriched cerosomes for topical management of cellulite. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2024 Oct 1;201:106875. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2024.106875, PMID 39121922.

El Naggar MM, El Nabarawi MA, Teaima MH, Hassan M, Hamed MI, Elrashedy AA. Integration of terpesomes loaded levocetrizine dihydrochloride gel as a repurposed cure for methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (mrsa) induced skin infection; d-optimal optimization ex vivo, in silico, and in vivo studies. Int J Pharm. 2023 Feb 25;633:122621. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2023.122621, PMID 36693486.

Albash R, El Nabarawi MA, Refai H, Abdelbary AA. Tailoring of PEGylated bilosomes for promoting the transdermal delivery of olmesartan medoxomil: in vitro characterization ex vivo permeation and in vivo assessment. Int J Nanomedicine. 2019 Aug;14:6555-74. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S213613, PMID 31616143.

Abdellatif MM, Eltabeeb MA, El Nabarawi MA, Teaima MH. A review on advances in the development of spermicides loaded vaginal drug delivery system: state of the art. Int J App Pharm. 2022;14(4):48-54. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2022v14i4.44925.

Abdellatif MM, Khalil IA, Khalil MA. Sertaconazole nitrate loaded nanovesicular systems for targeting skin fungal infection: in vitro, ex-vivo and in vivo evaluation. Int J Pharm. 2017;527(1-2):1-11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.05.029, PMID 28522423.

Karna S, Chaturvedi S, Agrawal V, Alim M. Formulation approaches for sustained release dosage forms: a review. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2015;8(5):46-53.

Zeb A, Qureshi OS, Kim HS, Cha JH, Kim HS, Kim JK. Improved skin permeation of methotrexate via nanosized ultra-deformable liposomes. Int J Nanomedicine. 2016 Aug 8;11:3813-24. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S109565, PMID 27540293.

Priyanka K, Singh S. A review on skin targeted delivery of bioactives as ultra deformable vesicles: overcoming the penetration problem. Curr Drug Targets. 2014;15(2):184-98. doi: 10.2174/1389450115666140113100338, PMID 24410447.