Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 4, 2025, 38-50Review Article

LIPID-POLYMER HYBRID NANOPARTICLES AND SILICA-BASED HYBRID NANOPARTICLES FOR CANCER TREATMENT

ANJANA A. KAILAS, ANNAMALAI RAMA, BHAUTIK LADANI , INDUJA GOVINDAN, K. A. ABUTWAIBE, ANUP NAHA*

, INDUJA GOVINDAN, K. A. ABUTWAIBE, ANUP NAHA*

1Department of Pharmaceutics, Manipal College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal-576104, Karnataka, India

*Corresponding author: Anup Naha; *Email: anup.naha@manipal.edu

Received: 30 Jan 2025, Revised and Accepted: 13 May 2025

ABSTRACT

The development of complex nanoparticles with enhanced tumor therapy selectivity and effectiveness is now achievable thanks to nanotechnology. Despite the vast number of nanostructures, such as liposomes, solid-lipid nanoparticles, Lipid-Polymer Hybrid Nanoparticles (LPHNPs), and Silica-based Hybrid Nanoparticles (SHNPs), have been developed as carriers for drug delivery for different pathologies with remarkably promising results. In the present study, we have discussed simple and efficient preparation methods for lipid-polymer and silica-based nanoparticles. These methods reduce the potential for toxicity as the drug molecules can be delivered to the pharmacological sites of action at an optimal controlled rate. With adequate preparation methods, lipid hybrid and silica-based nanoparticles can be developed to reduce adverse effects. Significant improvement has been made in preparing and functionalizing the hybrid nanoparticle for advancing cancer treatment. Studies prove that LPHNPs have exhibited drug-loading efficiency of around 60-70%, which is more than liposomal systems. The ability of these nanoparticles to circulate through the Reticulo-Endothelial System (RES) also results in a significant increase in circulation time, with a half-life of up to 12 h. These hybrid nanoparticles with high drug loading efficiency and specific targeting efficiency can help precisely target the tumor cells.

Keywords: Cancer, Lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles, Silica-based hybrid nanoparticles, Modified emulsification solvent evaporation, Nanoprecipitation, Polymeric core

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i4.53823 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

In the last decade, nanotechnology has given an entirely new direction for the detection and treatment of cancer. Hybrid Nanoparticles (HNPs) are the conjugates of the organic or inorganic Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (API), like small peptide molecules, proteins, and nucleic acids, with other components like inorganic metal structures, lipids or polymers, which give enhanced activity of the drug and more specific targeting to a tumor [1]. "Nano-theranostics" is a strategy for the development of nanocarriers such as liposomal HNPs, silica-based HNPs, micellar HNPs, viral HNPs, metal nanoparticles, and carbon nanotubes for enhanced theranostic effect with fewer side effects [2, 3]. Challenges with traditional drug delivery systems, such as liposomes and polymeric nanoparticles, include poor drug encapsulation, rapid drug release, and the inability to target tumors precisely [4]. Hybrid nanoparticles with lipid and polymer components counteract their limitations by improving drug-loading capacity, stability, and controlled release. Lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles (LPHNPs), for example, utilize the biocompatibility and self-assembly characteristics of lipids in conjunction with polymers that stabilize structure and control drug release. Meanwhile, much of the previous work on LPHNPs has concentrated on simple formulations and has tended to place less emphasis on optimizing LPHNPs concerning clinical-scale production, reproducibility, and targeting. Silica-based Hybrid Nanoparticles (SHNPs) provide significant advantages owing to the tunability and versatility of silica, facilitating precise control over particle size, surface modifications, and drug release characteristics [4, 5]. The significant advantage of nanosized hybrid particles is high entrapment efficiency with the protection of the loaded drug from other body stimuli [2]. Blood supply to the solid tumor cell is provided by "leaky vessels". Nano-sized particles are small enough to flow through these leaky vessels and target a specific tumor cell, and these particles are not excreted by the Reticulo-Endothelial System (RES). So, it increases the retention of the drug in the body, known as the Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect [6]. Inorganic HNPs like gold nanoparticles and SHNPs have optimal drug delivery characteristics with biocompatibility and stability. On the other side, protein nanocarriers having high systemic circulation enhanced tumor targeting by interaction with specific receptors like paclitaxel bounded with albumin enhanced affinity of drug towards gp60 and acidic, cysteine-rich secretory proteins receptor [7]. Easy conjugation of API with carriers because of the presence of COOH, OH and NH2 group, gelatin and β-lactoglobulin give smart pH and thermoresponsive drug release [8]. Some peptides, like casein, have high cellular penetration [9]. The concept of multifunctional HNPs is to incorporate diagnostic agents and API in a nanoparticle. This system is a "theranostic" device that can simultaneously diagnose and treat. For example, HNPs with a magnetic core of magnetite (Fe3O4) and a silica shell can be used to imagine a tumor using magnetic resonance and treatment [10]. The major types of HNPs and their clinical studies in cancer are summarized below. Physicochemical properties are summarized in table 1. This study thus attempts to fill these gaps through a comprehensive review of various aspects concerning the preparation, functionalization, and performance of LPHNPs and SHNPs in cancer therapy.

An exhaustive search of literature databases such as PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar was undertaken to facilitate an up-to-date review. Studies published between 2000 and 2024 were used as a search strategy to incorporate relevant foundational studies and recent advancements. Keywords used in this search include: ‘lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles,’ ‘silica-based hybrid nanoparticles,’ ‘cancer drug delivery,’ and ‘theranostics’. Additional filters were used to restrict the search results to the English language and peer-reviewed journal articles, excluding conference proceedings and non-English publications.

Although both LPHNPs and SHNPs are beneficial for their advantages in encapsulation efficiency, drug stability, and targeted delivery, LPHNPs provide better encapsulation efficiency with better drug stabilities than SHNPs, particularly for hydrophobic drugs. This can mainly be attributed to the nature of the lipid-cored, polymeric-shelled hybrid nanoparticles, where the hydrophobic part ensures higher encapsulation efficiency and protects drugs from degradation. In contrast, SHNPs demonstrate their incredible ability to provide controlled release profiles, specifically when functionalized with targeting ligands, and have a high-surface area advantage for loading different kinds of drugs. By engineering SHNPs with targeting agents, they can engineer tumor-targeting capabilities that are better or equivalent to other types. This is mainly because such engineered SHNPs can provide pH-responsive or receptor-mediated drug release. Thus, a comparative study between these two hybrid systems can lead to a more comprehensive understanding of how modification strategies can optimize each system for a specific drug delivery application, particularly in cancer therapy [11, 12].

Table 1: Physicochemical properties of LPHNPs and SHNPs [11, 12]

| Property | LPHNPs | SHNPs |

| Particle size | 100–300 nm; depends on lipid-polymer ratio | 50–500 nm; tunable by silica precursor concentration |

| Surface Charge | Neutral to slightly negative | Highly negative (−30 to −60 mV) |

| Surface Morphology | Core-shell structure | A porous structure enabling high drug loading |

| Encapsulation Efficiency | 60–95% for hydrophobic drugs | 50–80% for hydrophilic drugs |

| Drug Loading Capacity | 5–20% depending on polymer type | Up to 40% due to porous design |

| Surface Functionalization | Modified with PEG, folic acid, etc. | Modified with amines, thiols, etc. |

| Crystallinity/Phase | Often amorphous or semi-crystalline | Commonly crystalline with defined pores |

| Stability | Stable in physiological conditions; prone to aggregation without surfactants | Highly stable due to silica's rigid structure |

| Biodegradability | Faster degradation with biodegradable polymers like PLGA | Slow degradation into orthosilicic acid |

| Optical/Magnetic Properties | Limited unless modified with imaging agents | Doped with dyes, gold, or iron oxide for imaging |

| pH/Temperature Sensitivity | Responsive with pH-sensitive polymers | Pore-blocking agents enable precise release control |

| Hydrophobic/Hydrophilic Balance | The lipid layer enhances hydrophobic drug solubility | Hydrophilic silica surface suits aqueous formulations |

Lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles (LPHNPS)

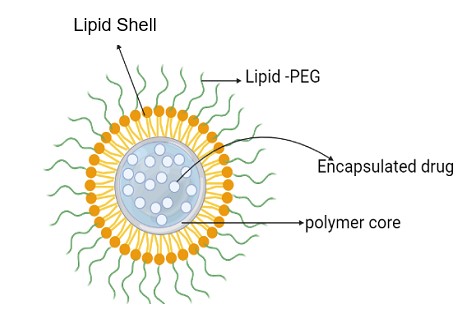

LPHNPs are novel spherical particles consisting of a lipid bilayer and natural or synthetic polymers in which drug molecules can be incorporated, as illustrated in fig. 1. LPHNP can be classified into various types based on the arrangement of the lipids and polymer-like (i) polymer core lipid shell (ii) core-shell type LPHNP (iii) Erythrocyte membrane-camouflaged LPHNP (iv) Monolithic LPHNP (v) Polymer cage liposomes [13]. The lipid shell is employed to provide stability and appropriate biocompatibility, while the polymeric core is used to carry a variety of small molecule medicines and diagnostic agents. Majorly used lipids for preparation LPHNPs are PC (phosphatidylcholine), DOTAP (1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane), DODAB (di octadecyl dimethyl ammonium bromide), DLPC (1,2-dilauroyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine), DPPG (dipalmitoyl phosphatidylglycerol), DSPE-PEG (1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero 3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[succinyl(polyethylene glycol) and various polymer like chitosan, PEG (polyethylene glycol), PLGA (poly-lactic-co-glycolic acid) are used [14].

Due to advantages like high structural integrity, high loading capacity, protection of the drug from other physical stimuli, easy preparation, and high functional ability make LPHNPs as a widely used tool in drug targeting. However, it also has disadvantages like storage leakage, and some polymers produce immunogenicity [15]. These delivery methods are generally employed to physically or covalently link ligands, hydrophilic and hydrophobic medicines, proteins, and other molecules of interest. These LPHNPs can also contain many medicines inside and outside their shell.

Fig. 1: Lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles

For instance, Corbin Clawson and colleagues developed multidrug-loaded nanoparticles with a lipid layer composed of DOPE and oleic acid. This lipid layer is self-assembled onto the surface of the polymeric core. The surface of these LPHNPs was further coated with lipid-(succinate)-mPEG, rendering the particles fusogenic and pH-sensitive. This design enabled the polymeric core to solubilize in aqueous environments and act as a diffusion barrier, thereby preventing encapsulated pharmaceuticals from leaching out [15].

Doxorubicin (DOX) and a Chinese herb extract called triptolide (TPL) were administered utilizing a reduction-sensitive LPHNP drug delivery system created by Bo Wu et al. It was shown that hydrophobic DOX and TPL could be successfully loaded in LPHNPs by self-assembly. The two medications were concurrently released from LPHNPs and efficiently absorbed by the human oral cavity squamous tumor cells. The dialysis process was used to create TPL-LPHNPs or DOX-LPHNPs because they can deliver several medications to the same cancer cell at once; LPHNPs have the potential to be a very effective synergistic therapeutic tool. Reductive agents in the buffer or inside the cancer cells themselves caused the release of DOX and TPL after cancer cells had taken them up [17, 18]. Various LPHNP formulations are tabulated below, and their intended use is shown in table 2.

Table 2: Examples of LPHNP with the formulation and its use

| Drug | Polymer | Lipid | Cancer type | Tested In vitro/In vivo/clinically | Reference |

| Curcumin | PLGA | DPPC and DSPE-PEG | Breast cancer | In vitro, In vivo | Palange AL et al., 2014 [47] |

| Isoliquiritigenin | PLGA-COOH | DSPE-PEG | Breast cancer | In vitro, In vivo | Gao F et al., 2017 [111] |

| Methotrexate and Aceclofenac | Polycaprolactone | DSPE-PEG (2000)-NH2 | Breast cancer | In vitro, In vivo | Garg N K et al., 2017 [112] |

| Doxorubicin hydrochloride | PLGA | DSPE-PEG 2000 | Breast cancer | In vitro, In vivo | Wu B et al., 2017 [17] |

| 10-hydroxy camptothecin | Egg lecithin and PLGA | DSPE | Breast cancer | In vitro | Yang Z et al., 2013 [116] |

| Paclitaxel (PTX) and Triptolide (TL) | PLGA | DSPE-mPEG5000 and DSPE-PEG5000-FITC | Lung cancer | In vitro | Zhang l et al., 2015 [59] |

| Curcumin and Cabazitaxel | PLGA and PEG-COOH | L-α-Phosphatidylcholine | Prostate cancer | In vitro, In vivo | Chen Y et al., 2020 [117] |

| Docetaxel | PLGA | DSPE-PEG 2000 | Prostate cancer | In vitro, In vivo | Wang Q et al., 2017 [118] |

| Hyaluronic acid modified, Irinotecan | Egg lecithin and PLGA | DSPE-PEG | Colorectal cancer | In vitro, In vivo | Wang Z et al., 2020 [119] |

| 5-fluorouracil | PEG-PLA | DSPE-PEG 2000 | Pancreatic cancer | In vitro, In vivo | Giram PS et al., 2024 [120] |

| α-mangostin | PLGA | DSPE-PEG2K-MAL | Breast cancer | In vitro | Sakpakdeejorean I et al., 2022 [42] |

| Docetaxel | PBAE | DSPE-PEG2000, FA-DSPE-PEG2000, and lecithin | Breast cancer | In vitro, In vivo | Cong X et al., 2022 [121] |

| Sunitinib malate | Chitosan | lipoid-90H | Breast cancer | In vitro | Ahmed MM et al., 2022 [44] |

| Verteprofin and 5-Fluorouracil | PLGA | DSPE-PEG, lecithin | Colorectal cancer cells | In vitro | Sang R et al., 2022 [41] |

| Erlotinib | PCL | DSPE-PEG 2000 and HSPC | Non-small cell lung cancer | In vitro, In vivo | Mandal B et al., 2016 [29] |

(Where PLGA= Poly lactic-co-Glycolic acid; PEG = polyethylene glycol; PLA= Poly lactic acid; PCL= poly caprolactone; HSPC= hydrogenated soy phosphatidylcholine; DPPC=1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine; DSPE-PEG=1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero 3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[succinyl (polyethylene glycol); DSPE-PEG-FITC=1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[(polyethyleneglycol)] fluorescein isothiocyanate); DSPE-PEG2K-MAL=1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-(maleimide (polyethylene glycol)-2000); FA-DSPE-PEG2000= Folic acid-1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-polyethylene glycol)

Preparation of LPHNP

Two-step method

The most widely used method for the preparation of the LPHNP is divided into two steps. First, the polymeric nanoparticle is prepared, and then the core is encapsulated into the lipid.

Conventional method

This is the most preferred method for the production of LPHNPs in the early phase of development, wherein the core of polymeric hybrid nanoparticles is first prepared and then fused with single or multi-layer lipids. Electrostatic interaction is the reason behind the fusion of the polymeric core and lipid layer.

For example, PEM-coated hybrid Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLNs) were effectively created by Thiruganesh Ramasamy et al. Layering hyaluronic acid (HA) and chitosan (CT), over negatively charged hybrid SLNs, layer-by-layer (LbL) nanoarchitectures. By assembling CT and HA on DOX/DS-SLNs, LbL coating significantly improved the retention of drugs and nanoparticles in the blood, opening the door for effective systemic/tumor therapeutic delivery. Because of the terminal HA's biomimetic characteristics, nanoparticles displayed anti-fouling qualities, which led to an extension of the circulation half-life and a reduction in the assessments of the elimination rate in comparison to uncoated SLNs [19, 20].

External energy required for fusion is provided by ultra-sonication direct hydration vortexing. Nano precipitation, a high-pressure homogenizer, and emulsion solvent evaporation are the methods used to manufacture LPHNP [19]. For the preparation of DOX and combretastatin-loaded LPHNPs, the shell is prepared by a combination of lipids like DSPE-PEG phosphatidylcholine, cholesterol, with combretastatin, and DOX is loaded in the core by conjugating with PLGA by the emulsion solvent evaporation method. A specific size of LPHNPs can be obtained by extrusion or homogenization [20, 21].

For example, Nasseen Seedat et al. used to create both drug-loaded and drug-free LPNs by heated high-pressure homogenization followed by ultrasonication. Helper lipid and polymer-infused LPN systems demonstrated regulated release profiles, greater medication encapsulation, and prolonged and improved antibacterial efficacy against susceptible and resistant bacteria types [23, 24].

Non-conventional method

Other than conventional methods, spray drying and soft lithography techniques like “Particle Replication in Nonwetting Templates (PRINT)” are also used to prepare LPHNPs. Spray drying of lipoidal polymeric suspension gives the LPHNPs. For example, the study was conducted on the use of spray drying and spray freeze drying methods for the preparation of LPHNP of levofloxacin by using polymers like PLGA and lecithin as a lipid phase [25]. Fabrication of LPHNPs with a PLGA-siRNA system protected in the lipid core by a top-down approach with a method of particle replication in nonwetting templates gives highly uniformed nanoparticles used for tumour targeting in prostate cancer. A solution contending with PLGA with siRNA was prepared in DMSO cast on ethylene terephthalate (PET) and placed in contact with “PRINT” mould [26].

One-step method

The drawbacks of the two-step method are more time-consuming and less efficient, so alternative one-step methods are developed for the manufacturing of LPHNPs. This method prepares polymeric nanoparticles and their encapsulation in a single step. Nano precipitation and modified emulsion solvent evaporation generally use single-step methods in preparing LPHNPs [27]. Qiang Feng et al. created a microfluidic device for synthesizing mono-dispersed lipid nanoparticles in a single-step, high-throughput, size-tunable way. The device has two stages. This method can be able to give emulsification, sonication, solvent evaporation, and purification of the produced NPs, all of which require intricate, multi-step procedures at various flow rates. The cellular absorption effectiveness of large lipid-PLGA NPs was inferior to that of tiny ones, and they were more prone to aggregate in serum [28]. Bivash Mandal et al. described a one-step synthesis technique for erlotinib-loaded Core-Shell Lipid Polymer Hybrid Nanoparticles (CSLPHNPs). The cells' cytoplasm filled up with CSLPHNPs loaded with erlotinib and fluorescent lipid tags. CSLPHNPs are created with a biodegradable polymeric core and a lipid monolayer shell to administer the anticancer medication erlotinib, which is clinically utilized to treat non-small cell lung cancer [29].

LPHNPs are advanced drug delivery systems with the benefits of liposomes and polymeric nanoparticles that are influenced by their methods of synthesis, which additionally allow for scalability and reproducibility essential for clinical purposes. One-step methods like microfluidic hydrodynamic focusing allow for greater control over nanoparticle parameters. As an example, P/lNPs prepared with microfluidic methods with sonication at a flow rate of 0.8 ml/min have been shown to exhibit characteristics of interest, namely, a particle size of ~106.4 nm and a Polydispersity Index (PDI) of 0.126, indicative of a narrow size distribution. However, the two-step procedures, i. e., emulsification-solvent evaporation, would provide more reproducibility regarding the control achieved over particle size and morphology. Still, it involves additional steps, such as solvent evaporation, which is challenging to scale up. All quantitative process parameters, such as sonication time or solvent ratios, must be optimized for appropriate nanoparticle characteristics. For example, one of the studies stated that adding Polyethyleneimine (PEI-800) to lipid nanoparticles would almost increase the particle size, and PDI slightly changes surface charge and stability. It is imperative to tune synthesis parameters accurately to derive an optimal system for successfully translating LPHNPs into clinical applications [30].

Nano precipitation

In conventional nanoprecipitation, drugs, lipids, and polymers are dispersed in an organic solvent that is aqueous-soluble substances are dispersed into the water. Heat should be applied to form a homogenous dispersion. Then, the organic solution is added to aqueous dispersion drop by drop. So, the diffusion of the organic solvent gives the LPHNP [31]. In this method, the final size of the particle depends on the ratio of organic and water phase and lipid to polymer ratio [15]. For example, in the preparation of DOX-loaded LPHNP, methanol and PLGA dissolved in acetone act as an organic phase, and bovine serum albumin (BSA) in water acts as an aqueous phase. When the oil phase is added to the water phase, acetone and methanol diffuse into the water and give LPHNP [32]. The process can be done without the help of heat; for instance, Ronnie H. Fang et al. prepared polymeric nanoparticles coated with a lipid monolayer using a modified multistep nanoprecipitation method. A factor of roughly 20 decreases the time needed to generate the same number of hybrid nanoparticles with this approach since it does not need heating the sample, centrifugation, or solvent evaporation. The high and homogenous energy input from the sonication bath can be credited for the quick production of LPHNPs. The sonication method produced a population of particles with minimal polydispersity and allowed the structural components to quickly finish the kinetic self-assembly process [33-37].

Bupivacaine (BVC) loaded LPHNPs were produced and tested by Pengju Ma et al. by utilizing a one-step nanoprecipitation process. Enhanced In vitro stability and reduced cytotoxicity were shown by BVC-LPHNPs in 10% FBS. At the same drug dose, BVC-LPHNPs showed decreased cytotoxicity of free BVC and considerably increased analgesic duration [38]. In recent advancements, nanoprecipitation has increased the efficiency of the method. Sonication provides higher energy, which results in the faster assembly of LPHNP [39]. The uniformity of LPHNP can be achieved by perfuming precipitation into the microchannels, wherein the mixing of organic and aqueous phases can be controlled. So, the micro-scale mixing improves the size uniformity of the particle. The time of solvent displacement is also reduced by using microchannels, so the homogeneity of the polymeric core could be increased [40]. Rui Sang and colleagues employed a one-step nanoprecipitation method to fabricate lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles (LPHNPs) for combined X-ray-induced photodynamic therapy (X-PDT) and chemotherapy using 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) to target colorectal cancer cells (CRC). The nanoparticles comprised a hydrophobic PLGA core for encapsulating verteporfin (VP) and 5-FU, a hydrophilic stealth shell (DSPE-PEG), and a lipid monolayer (lecithin) situated between the PLGA core and the DSPE-PEG shell. Their research activated verteporfin upon X-ray irradiation, generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) at varying radiation doses to induce tumor cell death. Furthermore, verteporfin acted as an approved photosensitizer for PDT in age-related macular degeneration. The combined X-PDT and chemotherapy approach notably suppressed the growth and proliferation of cancer cells. This strategy led to G2/M and S phase arrest in HCT116 cells, as evidenced by cell cycle analysis [41].

Sakpakdeejaroen and colleagues researched the preparation and characterization of transferrin-conjugated LPHNPs containing α-mangostin. This method offers advantages over the traditional two-step process, which involves separately preparing polymeric nanoparticles and lipid vesicles and combining them through ultrasonication and homogenization. In LPHNP formulations, the predominant mechanism of drug release involves the diffusion of α-mangostin from the outer layer of the polymer core through water-filled pores. Including PEGylated lipids in LPHNP formulations enhances water absorption, potentially accelerating drug release compared to polymer-based nanoparticles [42]. Imran Kazmi and colleagues developed Apigenin-loaded lipid hybrid nanoparticles (AGN-PLHNPs) through a one-step nanoprecipitation method. These optimized AGN-PLHNPs exhibited cytotoxic effects on breast cancer cells MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 in a dose-and time-dependent manner. Thus, the In vitro findings suggest that the modified AGN-PLHNPs represent a novel delivery approach with extended-release and enhanced cell viability [43].

Modified emulsification solvent evaporation

The method of emulsification has two types. Namely, single emulsification and double emulsification.

Mohammed Muqtader Ahmed and colleagues utilized sunitinib malate (SM), an anticancer agent, loaded into LPHNPs (lipid polymer hybrid nanoparticles) fabricated with lipoid-90H and chitosan through the emulsion solvent evaporation technique. Four formulations (SLPN1–SLPN4) were created by adjusting the concentration of chitosan polymer. The potential cytotoxicity of SLPN4 on MCF-7 breast cancer cells was assessed using the MTT assay for cytotoxicity, along with ELISA analysis of caspase-3,-9, and p53 activity, compared to free SM or control. The optimized SM-loaded LPHNPs (SLPN4) significantly enhanced the release and accessibility of SM to breast cancer cells, as demonstrated by In vitro release and cell line analyses [44, 45]. The hydrophobic drug is encapsulated using a single solvent evaporation method. An oil phase comprising the drug and polymer is prepared in this process. In contrast, an aqueous phase containing dissolved lipids is formed to create an oil-in-water (o/w) emulsion through continuous stirring or ultrasonication. Subsequent evaporation of the organic phase results in the formation of nanoparticles [46]. For instance, Curcumin-loaded lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles (LPHNPs) for breast cancer treatment are fabricated using a single emulsion solvent evaporation technique. Here, a solution of PLGA containing the drug and DPPC in acetone serves as the oil phase, which is dispersed into an aqueous phase containing DSPE-PEG in ethanol under ultrasonication [47].

Burcu Devrim et al. developed lysozyme-loaded LPNPs by modifying the w/o/w double emulsion solvent evaporation method. These LPNPs exhibited reduced particle size, spherical morphology, enhanced encapsulation efficiency, stability in serum, minimal cytotoxicity, and increased cellular uptake [48, 49]. Jianguo Wang and colleagues devised a customized solvent extraction/evaporation method to produce lidocaine-loaded lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles (LA-LPNs) for a topical formulation aimed at rapid onset and prolonged duration. Their study demonstrated that LA-LPNs induce a more potent anesthetic effect, suggesting their capability to facilitate the transdermal transport of anesthetics with sustained release properties. This innovation holds promise as a potential technology for overcoming the skin's barrier function in drug delivery [50]. Hongyan Zhang and colleagues devised nanoparticles composed of a polymer core, poly[beta-amino ester] (PBAE), and a mixed lipid shell containing DSPE-PEG2000, FA-DSPE-PEG2000, and lecithin aimed at delivering docetaxel (DTX) specifically to breast cancer cells. They employed single emulsion (O/W) solvent evaporation and self-assembly techniques to fabricate the DTX-loaded nanoparticles. DTX was effectively encapsulated within the PBAE core through hydrophobic interactions. The stained lipid layer enveloping the polymeric core contributed to the increased electron density at the periphery of these LPHNPs. In experiments conducted on mice bearing 4T1 tumors, FA/PBAE/DTX-NPs exhibited heightened anticancer efficacy with minimal systemic toxicity. These results suggest that FA/PBAE/DTX-NPs hold promise as targeted delivery vehicles for breast cancer therapy, enhancing their therapeutic efficacy [51].

LPHNPs of the hydrophilic drug are prepared using the double emulsion method, in which the drug is dissolved in the water phase and incorporated into the hydrophobic phase, containing lipid and polymeric units. This W/O type of emulsion again incorporates an aqueous phase with lipid-PEG, followed by oil evaporation, giving LPHNPs [46]. This process involves the development of LPHNP for treating pancreatic cancer, utilizing a combination of HIF1a siRNA and gemcitabine. This method dissolves gemcitabine in water and is then incorporated into the oil phase containing methylene chloride and MPEG-PLGA using sonication. This oil-in-water emulsion is added to the aqueous phase of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and ε-polylysine (EPL) with continuous stirring. The solvent is then evaporated using vacuum drying to achieve the desired formulation [52]. Sebastian Vencken and colleagues developed LPHNPs using a double emulsion solvent evaporation technique. These nanoparticles were designed to encapsulate double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) oligonucleotides, miR-17 mimics, and LPHNPs within DOTAP-modified PLGA LPHNPs. Using DOTAP-modified PLGA LPHNPs offers a promising avenue for future miRNA-based therapies targeting inflammatory lung diseases. These nanoparticles serve as safe and effective carriers for the nebulized delivery of miR-17 to bronchial epithelial cells (BECs) [53].

Rodrigo Scopel utilized a method combining solvent evaporation emulsification and mild hydration to create vitamin D3-functionalized lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles (HNP-VDs). This approach targeted Vitamin D Receptors (VDR) expressed in melanoma cells. The HNP-VDs, consisting of a core composed of PLGA and a lipid shell containing HSPC, cholesterol, and DSPE-PEG, were found to target and attack B16 melanoma cells effectively, demonstrating the efficacy of the designed nanoparticles [54]. Rajendra Jangda and colleagues developed a method to enhance the distribution of hesperidin in wound sites and improve its effectiveness. They utilized a double emulsion technique, known as w/o/w, to produce hesperidin-loaded LPHNPs, subsequently freeze-dried into nanoparticles. This process, termed emulsion-solvent evaporation, resulted in stable LPHNPs with increased surface area and nano size, potentially boosting the topical bioavailability of hesperidin. The findings suggest that LPHNPs could effectively deliver bioactive hesperidin to wounds, potentially accelerating wound healing [55].

Recent advancements in the LPHNPs for drug delivery in cancer

Due to its highly effective medication loading, biocompatibility, and extensive circulation in the bloodstream, LPHNPs offer superior efficacy compared to conventional cancer treatments. The polymer within LPHNP facilitates sustained release of medication from the delivery system, thereby prolonging its action and reducing both dosage requirements and side effects. Compared to other cancer treatments, such as chemotherapy, combination therapy involving LPHNP demonstrates a synergistic effect against MDR cancer cells. Ying Liu et al. capitalized on the advantages of polymeric and lipid-based nanoparticles to enhance the oral delivery of poorly water-soluble oridonin. They developed and characterized wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) modified LPNs (WGA-LPNs), incorporating WGA to enhance site-specific adhesion and improve bioavailability. Their modified one-step nanoprecipitation method is faster and more straightforward than the emulsification-solvent-evaporation technique, making it more suitable for large-scale production. WGA-LPNs can potentially enhance oral medication administration by promoting cellular absorption and intestinal adhesion [56–58].

Surface-modified lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles (LPHNPs) offer a pathway to achieve specific targeting of tumors. According to research, Folate-Modified LPHNPs (FLPHNPs) enable precise and controlled delivery of paclitaxel to the targeted site. These nanoparticles, synthesized via ultra-sonication using DSPE-PEG 2000 as a lipid and PCL-PEG as a polymer, are tailored for breast cancer treatment. Including paclitaxel in FLPHNPs enhances targeting efficacy compared to non-targeted nanoparticles [59]. Linhua Zhang et al. developed a drug carrier consisting of folate-modified lipid-shell and polymer-core nanoparticles (FLPNPs) for the targeted, sustained, and regulated delivery of paclitaxel (PTX). PTX-loaded FLPNPs exhibited comparable anticancer efficacy and low toxicity. Cellular uptake studies revealed efficient internalization of PTX-loaded FLPNPs, demonstrating the anticancer potential of folate-targeted nanoparticles via receptor-mediated endocytosis. FLPNPs hold promise as an effective drug delivery system for treating cancers characterized by overexpression of the folate receptor [60]. Maitham Alhajamee and colleagues employed the ionic gelation technique to fabricate tamoxifen-curcumin-loaded lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles (Tmx-Cu-LPHNPs). This approach aimed to enhance tamoxifen and curcumin's cytotoxic and anti-cancer properties co-encapsulated within the LPHNPs. The study revealed tamoxifen-induced cell cycle arrests in the G1 phase, while curcumin led to cell cycle arrests in the S phase. Treatment with Tmx-Cu-LPHNPs resulted in cell cycle arrests in the SubG1 phase. Furthermore, Tmx-Cu-LPHNPs exhibited larger size, more uniform dispersion, and greater stability than LPHNPs [61].

Dehui Fu and colleagues developed stable LPHNPs containing cisplatin (CDDP) and afatinib (AFT) to combat Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma (NPC). AFT significantly inhibited the growth and survival of five different lines of human head-and-neck squamous cell carcinomas. The accumulation of nanoparticles in tumor tissues is facilitated by the tumor microenvironment's EPR effect and the ability of particles smaller than 200 nm to penetrate tumors. The combination of CDDP and AFT increased the number of cells in the G2/M and sub-G0 phases (apoptosis) while decreasing the proportion in the G0/G1 phase. CDDP arrested the cell cycle in the G2/M phase. The dual-drug-loaded LP NPs also demonstrated potent anticancer activity by significantly increasing the number of cells in the sub-G0 phase and decreasing those in the G2/M phase. Compared to administering free drugs separately or in combination, encapsulating AFT and CDDP in a nanocarrier enhanced cell cycle arrest and cell death [62].

Hui Liu et al. created a treatment for breast cancer with emodin-loaded LPHNPs (E-PLNs). E-PLNs were made using the nanoprecipitation technique. By encouraging the absorption of emodin, E-PLNs demonstrated increased toxicity to MCF-7 cells and can trigger early apoptosis in these cells. The ratio of anti-apoptotic protein Bax/Bcl-2 considerably rises in addition to the morphological alterations of apoptotic cells, indicating that E-PLNs can cause apoptosis in MCF-7 cells to have an anticancer impact [63-65]. Using the nanoprecipitation technique, Safiullah Khan and colleagues developed poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) based LPHNPs loaded with 5-FU. These drug-loaded LPHNPs exhibited prolonged release and enhanced cellular uptake compared to 5-FU solution, increasing cytotoxicity. The produced 5-FU-loaded LPHNPs effectively enhanced toxicity against MCF7 and HeLa (human cervical) cell lines in a concentration-dependent manner. The sustained release and improved intracellular uptake of LPHNPs led to reduced cell viability and heightened cytotoxicity compared to the 5-FU solution. The enhanced cytotoxicity of LPHNPs was attributed to lipid-mediated cytosolic transport of 5-F [66]. The tumor microenvironment differs from the normal cellular environment due to the presence of aged and newly formed blood vessels and various growth factors. These distinct microenvironments lead to subtle physiological changes within the tumor, such as a slightly elevated temperature, a reductive environment, and acidic pH, which actively target the tumor [15]. Innovative designs of low pH-sensitive nanoparticles are developed to target the low pH environment of tumors, featuring a PEG coating. These particles remain stable at normal physiological pH but unstable at lower pH levels. Low pH-sensitive nanoparticles are prepared with PEG and a lipid monolayer, rendering them pH-sensitive through lipid-(succinate)-MPEG conjugation. The pH sensitivity of these particles can be adjusted by altering the lipid-(succinate)-MPEG concentration. Such pH-sensitive LPHNPs are predominantly utilized in lung cancer treatment [67]. Apart from lipid-(succinate)-MPEG, other triblock polymers like (mPEGPLGA-PGlu) are employed for pH-responsive drug release, particularly for doxorubicin, at pH 5.1 [68]. The Stimuli-Responsive Lipid Polymer Hybrid Nanoparticle (SRLPHNP) represents a notable advancement in LPHNP technology, offering enhanced specificity in active targeting while mitigating side effects. A recent study revealed that SRLPHNPs incorporate magnetic beads within their core and employ remote radiofrequency for active targeting. These nanoparticles are loaded with camptothecin and Fe3O4 within the PLGA polymer core and coated with a DSPE-PEG lipid monolayer. The release of medication from the particles is controlled by external stimuli such as radiofrequency. The ease of preparation and precise targeting capabilities has led to widespread adoption in cancer treatment [69].

All-trans retinoic Acid (ATRA) based differentiation therapy is important in treating melanoma. ATRA is an active derivative of retinol and exhibits a targeted effect on cancer-initiating cells. However, a notable challenge lies in the low bioavailability of ATRA, which can be addressed through the formulation of LPHNP utilizing PLGA and PEG polymers. These particles enable active targeting of CD20, a glycosylated phosphoprotein expressed in melanoma cells [70]. The size of an ultra-small lipid polymer hybrid nanoparticle (USLPHNP) is less than 25 nm, and it can be prepared by the nanoprecipitation method. The spleen and liver can easily remove a larger particle greater than 200 nm. Particles smaller than 50 nm can have deep tissue penetration, which also improves the localization of the particle in tissue. Such USLPHNP is sometimes also used for brain targeting because it can cross the blood-brain barrier [71]. Novel nanostructured lipid-dextran sulfate hybrid carriers (NLDCs) have been employed in combating multiple drug-resistant cancers. Their unique composition, incorporating dextran sulfate, enhances both encapsulation efficiency and the sustained release of mitoxantrone hydrochloride, a crucial agent utilized against MCF-7/MX cells, a form of breast cancer known for its resistance to conventional treatments [72]. Yong Tae Kim and colleagues successfully synthesized LPHNPs using microfluidics, which improved the mixing process but suffered from low throughput. Their work introduced a pattern-tunable micro vortex platform for the controlled single-step nanoprecipitation of PLGA-PEG polymeric nanoparticles, enabling mass production and precise size control for medical imaging and drug delivery. To address the issue of localized PLGA aggregation near the PDMS microfluidic channel walls, they modified the approach by incorporating 3D focusing flow patterns. Achieving high throughput and reproducibility in nanoparticle synthesis necessitates rapid mixing of nanoparticle precursors, which must be carefully monitored. It has been demonstrated that a Tesla-style microfluidic structure enhances lipid production with rapid mixing. Compared to traditional microfluidic diffusive synthesis methods, polymeric nanoparticles can now be produced up to a thousand times faster [73].

Recent advancements in molecular imaging utilize LPHNP as an imaging and therapeutic agent. In this process, the probe is enclosed within the core along with a drug for imaging purposes. LPHNP incorporates quantum dots, gold, and superparamagnetic iron oxide into the polymeric core of PLGA, prepared using the w/o/w double emulsion method. The Magnetic Resonance Imaging of LPHNP produces images that rely on the polymer's concentration [74, 75].

Interaction of lipid shell and polymer in LPHNP

The hybrid nanoparticles lipid-polymer matrix (LPHNP) protects the drugs from premature degradation due to the synergetic activity of either the lipid shell or polymer core. The lipid shell forms an external hydrophobic barrier through phospholipids such as DPPC or DSPE-PEG to sequester hydrophobic drugs from any external aqueous medium. It thus prevents their premature degradation because of the enzymatic activity fluctuations in pH. The polymeric core is made from biodegradable materials like PLGA or PCL, thus providing mechanical strength to drugs while forming a system that favors control release to prevent rupturing or leakages with drugs. This dual system stabilizes drugs by giving protection to sensitive drugs regarding oxidation and hydrolysis to keep their therapeutic efficacy. The release has been controlled because of the ratio of lipids to polymers and other test material parameters and drug affinities towards either phase; this will ensure sustained release but lessen the side effects [76-78].

Silica-based hybrid nanoparticle (SHNP)

The application of nanotechnology in cancer diagnosis and treatment has seen significant advancement in recent years. Particularly, silica-based nanocarriers have garnered considerable attention in cancer therapy. Mesoporous materials discovered in the 1990s have shown remarkable potential in biomedical applications. Various silica-based nanocarriers are utilized for targeted drug delivery, employing active and passive targeting mechanisms to reach tumors effectively [79]. The development of SHNP technology progresses through three generations. First-generation SHNPs are designed for sustained drug release, thereby prolonging the drug's therapeutic effect. Second-generation SHNPs, characterized by uniform surface topology and hollow nanostructures, enhance drug loading capacity. Finally, third-generation SHNPs enable specific targeting and simultaneous delivery of drugs and imaging agents, offering promising avenues for cancer treatment [80].

The distinctive surface morphology of SHNP exhibits two distinct domains that operate independently. The inner pores facilitate high drug loading of organic or large biological molecules, while the outer pores enable selective, site-specific targeting [81]. With a high surface area, SHNP allows for increased drug loading, averaging 60 mg of drug per g of silica. Specific stimuli-responsive SHNP, such as pH-responsive, thermoresponsive, enzyme-responsive, light-responsive, and ultrasound-responsive variants, target specific cells, reducing drug toxicity. The tunable pore size accommodates various drug sizes and shapes for incorporation. Silica's high compatibility enhances the utility of silica nanoparticles in cancer treatment. The pharmacological effectiveness of SHNP is heavily influenced by particle size, preparation method, particle geometry, and surface chemistry. Despite its advantages, there are instances where rapid drug release may lead to adverse pharmacological effects [82, 83].

Method of preparation for SHNP

Co-condensation

Co-condensation represents a one-step procedure wherein surfactant template molecules transform through sol-gel transition. During this process, surfactant molecules such as cetyl trimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB), hexadecyl trimethyl ammonium chloride (CTAC), and tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) undergo condensation with an acid or basic solvent like triethanolamine. This results in the formation of silica-siloxane bonds. Within this gel solution, organosilanes are introduced, replacing the silica precursor and yielding SHNP. This method offers the advantage of high organosilane loading and their uniform distribution [79, 84]. According to research, the co-condensation of 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES) and TOES in the presence of superparamagnetic iron oxide produces magnetic SHNP [85].

This method allows a good degree of control on the nanoparticle structure; however, challenges can arise for maintaining a uniform distribution of functional groups because functionalization may vary with organic modifier concentration as well as other reaction parameters [86]. Uniform functionalization is necessary to provide most consistent properties, such as drug delivery and immunogenicity, because that might be hindered by many other influencing factors, such as solubility of precursors, pH variations, and complexity of the reaction scheme.

Grafting

Grafting is proposed as an alternative to co-condensation, wherein SHNP are first prepared, followed by the grafting of organosilanes onto their surfaces. The functional groups attached to these surfaces are crucial in therapeutic and diagnostic actions. Various stimuli-responsive SHNP can be attained by attaching different functional groups, enabling drug release triggered by specific stimuli [79]. For instance, pH-responsive drug release can be achieved through the preparation of "PEGylated silica-poly[2-(dimethylamino)ethyl acrylate] (PEGylated MSN-g-PDMAEA)" SHNP. Initially, a silica base chain is formed through tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) condensation in an octane solvent. Subsequently, the functional group is grafted onto the surface via a three-step chemical reaction, forming PEGylated MSN-g-PDMAEA. When shaken at 80 RPM in acetate buffer pH 5, Doxorubicin loaded with PEGylated MSN-g-PDMAEA demonstrates effective drug loading [87].

This method allows for a more controlled introduction of functional groups, but difficulties arise in achieving uniform grafting and preventing aggregation. The inconsistency in grafting results in heterogeneities of nanoparticle size, surface charge, and drug-loading capacity, which affect the reproducibility and performance of the material. Because it requires precise control of reaction time, temperature, and concentration of functional agents, consistent functionalization across different batches is often quite difficult [88].

Targeting of cancer cells using SHNP

Passive targeting

The distinct physiological characteristics of cancer cells, such as vascularity, permeability, and cellular organization, provide an opportunity for targeted drug delivery. Passive targeting exploits the EPR effect, allowing drug molecules to accumulate to a higher extent in cancer cells. SHNP with a molecular weight below 80 kDa exhibit greater penetration into tumor cells. The primary objective of passive targeting is to prolong the circulation time of the drug in the body by minimizing excretion. Passive targeting relies on various properties of SHNP, including size, shape, and surface morphology. However, variations in vascularity among different cancer cell types can result in poor bioavailability and increase the likelihood of resistance to multiple drugs. Hence, active drug targeting utilizing the EPR effect is predominantly favored for targeting tumor cells [79, 89].

Active targeting

Utilizing specific ligands attached to the surface of SHNP, this approach, known as ligand-mediated targeting, is employed for inactive targeting. The ample surface area of SHNP facilitates the attachment of the ligand. This method enables drug delivery based on specific bodily or external stimuli or targeting specific receptor sites through ligand attachment [83]. The size of the ligand plays a crucial role in targeting, with smaller ligands offering potential advantages over larger ones. For ligand conjugation, widely employed methods include COOH/NH2 coupling and maleimide/SH coupling [89].

Various ligands for active targeting in cancer treatment areas are described below.

Antibodies

Antibodies, particularly proteins, serve as effective targeting agents due to their precise binding to receptors present in cancer cells [79]. They can be conjugated to SHNP through either covalent bonds or electrostatic interactions. Polymer cross-linking agents like PEG facilitate the formation of silica-based hybrid nanosystems, protecting the antibodies. The ratio of antibodies to silica nanocarriers significantly influences cell recognition [89]. Monoclonal antibodies offer enhanced targeting efficacy. In a recent study, anti-HER2/neu monoclonal antibodies were tethered to mesoporous silica using PEG polymer for breast cancer cell targeting. The findings demonstrate that SHNP loaded with antibodies exhibit superior targeting efficiency, influenced by the surface density of monoclonal antibodies Top of Form[90].

Proteins

Transferrin, a glycoprotein, targets cancer cells when conjugated with SHNP actively. Transferrin receptors, abundant in cancer cells, facilitate this targeting. The binding occurs through redox-cleavable disulfide bonds, with DOX loaded into the system. Upon encountering glutathione, the nanosystem triggers a rapid drug release [91].

Peptides

The peptide is a molecule with a few amino acid structures utilized for active targeting, serving as an alternative to antibodies as a targeting agent. Among active targeting methods, peptides are more efficient in targeting cancer cell nuclei. In a recent study, SHNP was conjugated with the TAT (Transactivator of Transcription) peptide, exhibiting a high payload for targeting cancer nuclei. Among various sizes of SHNP tested, those smaller than 50 nm demonstrated high efficiency in tumor targeting and delivery of doxorubicin for cancer treatment [92].

However, there exist some peptides that show affinity in the low micromolar to nanomolar range (Kd ~ 10 to 100 nM) with respect to their binding partners, for instance, the RGD peptide binding to integrin receptors on cancer cells [93].

There are many advantages to peptides, such as high specificity; these peptides, in fact, can be designed to bind cellular receptors with very little off-target effect. Peptides are also relatively easy and economical to synthesize in bulk. They are also less likely to provoke an immune response, making them suitable for repeated treatment. However, peptides suffer some limitations. High specificity is achieved in most cases, but the binding affinities differ from those for other ligands like antibodies; ligands may possess weaker binding affinities. For instance, the RGD peptide often presents dissociation constants (Kd) in a nanomolar range (10-100 nM), thus possibly limiting the targeting efficiency [93]. Peptides are subjected to enzymatic degradation by proteolytic enzymes; however, they can be made stable through chemical modifications or peptide mimetics.

Aptamers

They are molecules of "single-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid (ssDNA)" or "Ribo Nucleic Acid (RNA)" that can be synthesized as needed. Due to their low immunogenicity and high targeting efficiency, they are more effective than antibodies. SHNP, prepared with a negative MUC1 aptamer, targets breast cancer cells overexpressing mucin 1 (MUC1) surface protein. SHNP containing MUC1 (S1-apMUC1) targets MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells and delivers the drug doxorubicin specifically to the intended cell [94].

Aptamers can yield higher binding efficiencies, with some aptamers having picomolar dissociation constants, meaning they can bind tighter than peptides [95]. Target-specific aptamers display some benefits, including high specificity and affinity, with dissociation constants (Kd) reported to be as low as 10^-12 M in aptamers directed to EGFR [95]. Also, aptamers are highly stable, with RNA aptamers being resistant to proteolytic degradation and capable of chemical modifications to increase their stability against nucleases. Additionally, aptamers are believed to be weakly immunogenic and, hence, suitable for chronic applications. However, their synthesis may be more elegant than for peptides for larger molecular aptamers. They also show limited target ranges because of specific recognition of one set of markers, but they might bind nonspecifically to other biomolecules having similar structural motifs, therefore inducing off-target effects.

Saccharides

Different saccharides, such as mannose and lactobionic acid (derived from lactose), are utilized for targeting cancer cells. A study suggests that the presence of lactobionic acid receptors on the surface of liver cancer cells enhances the absorption of the nanosystem. Nanoparticles featuring lactose on their surface and carrying platinum (IV) are employed for targeting liver cancer cells. Once the nanosystem is absorbed, platinum (IV) undergoes reduction, resulting in the activation of platinum (II) for targeted therapy [96].

Small molecules

Small molecules like folic acid play pivotal roles in actively targeting cancer cells. A folate receptor (FR) on virtually any type of cancer cell provides a prime opportunity for precisely targeting these cells using folic acid. This receptor, known as α-FR, serves as a distinct marker, allowing for the strategic delivery of therapeutic agents directly to cancerous tissues [97].

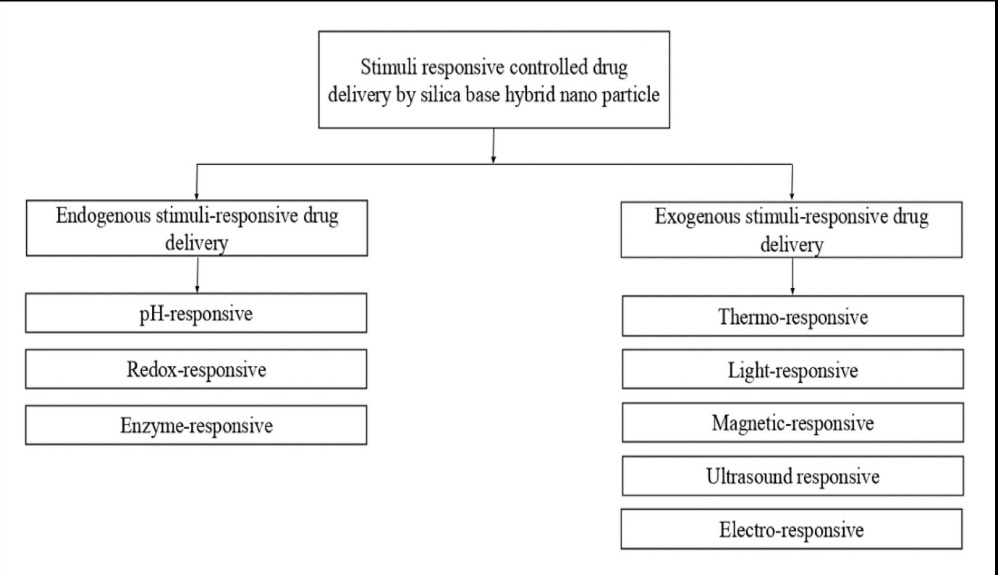

Stimuli-responsive controlled drug delivery by SHNP

In traditional cancer treatment, therapeutic agents swiftly eliminate cancer cells but also harm healthy cells. This collateral damage underscores the need for precise targeting methods to attack cancer cells while sparing normal ones selectively. One promising avenue involves using stimuli-responsive SHNP systems, which can react to internal and external cues. By harnessing these responsive properties, SHNPs offer a potential solution to mitigate the adverse effects of cancer drugs. This targeted approach holds promise to significantly reduce the debilitating side effects of conventional cancer treatments Top of Form[98]. Fig. 2 illustrates the various types of stimuli-based drug delivery strategies.

Fig. 2: Various types of stimuli-based drug delivery strategies

pH-responsive SHNP

pH-targeted drug release is highly appealing among various endogenous stimuli. Tumor or inflammatory cells typically exhibit a lower pH than regular body cells (7.4) or blood cells, while specific organelles like lysosomes have an even lower pH (5.5). This pH gradient provides a means to target drugs to specific cells [99]. Several strategies for pH-triggered drug delivery systems can be employed, such as acid-cleavable linkers/bonds, polymer gatekeepers, supramolecular nano valves, and acid-decomposable gatekeepers.

Different bonds, including boronate ester, acetal, and hydrazine, can cleave at specific low pH levels, facilitating drug release. In a study by Ke Yang et al., pH-triggered drug release was achieved by coating SHNP with poly(N-succinimidyl acrylate) via an acid-sensitive acetal linker. Nanoparticles were loaded with DOX and coated with poly(N-succinimidyl acrylate) to prevent premature drug release. Folic acid and biodegradable polymer PEG were added to facilitate cellular uptake [100]. Based on pH stimuli, various pH-sensitive gatekeepers are utilized as pore blockers and openers in SHNP. In one study, SHNP incorporated poly(2-(pentamethyleneimino)ethyl methacrylate) (PPEMA) as a pH-sensitive gatekeeper along with PEG for enhanced dispersibility and blood circulation time. At neutral pH, the PPEMA chain collapses, blocking pores and encapsulating doxorubicin, while at acidic pH, PPEMA becomes protonated, opening the pores and releasing the drug [101]. SHNP is equipped with supramolecular nano valves for targeted drug release and consists of immobilized stalk molecules connected to silica carriers by covalent bonds. Nano valves are designed to block drug release at normal pH levels, with mild pH changes triggering cap release and significant changes leading to stalk release. Aromatic amines and cyclodextrin are commonly used as stalk and cap compounds for delivering DOX to tumor cells [102]. Acid-degradable gatekeepers are also employed for stimuli-responsive drug release, utilizing layered double hydroxides, calcium phosphate nano-coatings, and zinc oxide quantum dots. SHNP containing layered double hydroxides was prepared via a sol-gel method, with drug release facilitated by the dissolution of the hydroxide layer in acidic conditions [103].

Redox responsive SHNP

The significant variance in redox agent concentration between intra-and extracellular environments offers ample targeting opportunities. Tumor cells notably exhibit higher levels of glutathione (GSH) than healthy cells. Silica nanocarriers are modified with inorganic compounds such as Au and Fe3O4 and organic compounds like PEG and heparin peptides. Attachment occurs via disulfide bonds to enable redox-responsive drug release from the surface of these nanocarriers [80, 98]. L. Dai and colleagues proposed a method where silica nanocarriers are structured with heparin, end-capped through disulfide bonds, facilitating glutathione-targeted drug release. Lactobionic acid is conjugated with heparin to enhance the uptake of the nanosystem by HepG2 cells. The reduction of disulfide bonds in the presence of high concentrations of glutathione triggers the release of doxorubicin by opening the silica pores [100]. Shanshan Wu and co-researchers developed a nanosystem incorporating zinc oxide quantum dots (QDs) attached to the silica surface via disulfide bonds. This enables drug release triggered by lower pH and bond cleavage. This approach allows targeted drug delivery through multiple stimuli, including redox and pH changes [104].

Enzyme responsive SHNP

The elevated concentration gradient of numerous enzymes within tumor cells compared to normal cells offers a significant opportunity for precise tumor targeting. One approach to creating enzyme-sensitive SHNP carriers involves coating them with enzyme-sensitive chains or utilizing protease-sensitive linkers [80, 98]. Specifically, MMPs (matrix metalloproteinases), notably MMP2 and MMP9, are overexpressed in tumor cells. Certain polymers, such as gelatin, which are non-immunogenic and biodegradable, become activated in the presence of MMPs. In a study by Jun-Hua Xu et al., SHNPs were prepared with a gelatin coating serving as a protective barrier for the drug, enabling its release in the presence of MMPs. Due to increased endocytosis activity, this mechanism facilitates the delivery of model drug doxorubicin into cancer cells. The abundance of MMPs leads to the degradation of the gelatin coating, resulting in the release of the drug from the DOXMSNs@Ge [105]. Cathepsin B is a specific protease enzyme that targets the Gly-Phe-Leu-Gly (GFLG) sequence to activate drug delivery. Cheng et al. devised a method for loading doxorubicin onto self-immolative hydrazone nanoparticles (SHNP), creating a rotaxane structure with an alkoxysilane tether and α-cyclodextrin (α-CD) acting as a gatekeeper. The nanosystem's surface, featuring RGDS and a continuous seven-arginine (R7) sequence, facilitates its easy cell penetration. The higher concentration of cathepsin B within tumor cells enables the hydrolysis of the GFLG sequences, triggering drug release from the valve [106].

Thermoresponsive SHNP

Thermoresponsive SHNPs have been extensively researched and applied for tumor targeting in cancer treatment. This drug delivery system involves coating silica nanoparticles with a thermosensitive polymer to regulate drug release based on temperature fluctuations. By utilizing this approach, the surrounding tumor tissue can be selectively targeted. A commonly used polymer for crafting such DDS is Poly N-isopropyl acrylamide (PNIPAM). However, PNIPAM's lower critical solution temperature (LCST) of 32 ℃ renders it unsuitable for physiological applications. To address this issue, hydrophilic monomers like glycine are incorporated to elevate the LCST. Below the LCST, PNIPAM remains hydrophilic, while above it, PNIPAM chains dehydrate and disintegrate, facilitating drug release from the SHNP [80, 107]. Additionally, other polymers such as poly(ethylene oxide-N vinyl caprolactam) and zwitterionic sulfobetaine can also be employed in the preparation of thermosensitive SHNP, broadening the range of potential applications for this innovative drug delivery system [108].

Light responsive SHNP

Light-sensitive drug delivery systems have recently been developed using silica as a carrier. When exposed to UV-visible light, the nano-carrier undergoes a conformational change, triggering rapid drug release from the reservoir. One approach involves preparing doxorubicin-loaded light-sensitive SHNPs by incorporating azobenzene-modified nucleic acids. Under UV light, azobenzene undergoes isomerization from the more stable trans configuration to the less stable cis configuration, facilitating drug release. Additionally, light-responsive drug delivery systems can utilize spiropyran derivatives and coumarin derivatives. For instance, 7-[(3-trihydroxysilyl) propoxy]coumarin is attached to the silicon group, controlling drug release. However, exposure to UV light induces photo-dimerization, forming cyclobutane dimer rings, which lead to pore formation and subsequent drug release.

Magnetic responsive SHNP

Delivering drug-loaded silica nanoparticles to tumor cells using an external magnetic field can be achieved through magnetic-responsive SHNPs. Iron oxide stands out as a commonly utilized carrier for such magnetic-responsive SHNP. When subjected to an external magnetic field, thermal energy is produced, facilitating controlled drug release from the imgded silica magnetic nanoparticles. Additionally, a thermoresponsive material coating the silica surface undergoes conformational changes due to this thermal energy, further aiding in the controlled release of the drug [109]. Lu and colleagues developed thermoresponsive SHNPs infused with iron oxide, demonstrating exceptional drug-loading capacity. Employing nanospheres as a template, their innovative approach yielded high drug-loading capabilities. This framework encapsulated DOX within iron oxide nanoparticles, facilitating localized heat generation upon exposure to an alternative magnetic field (AMF) [110].

Ultrasound responsive SHNP

Ultrasound (US) presents several advantages over external stimuli, including low invasiveness, cost-effectiveness, and simple tissue penetration control. When high-frequency US passes through the body, it induces various physical changes such as localized high temperature, cavitation, alterations in pressure, and acoustic fluid streaming [80, 111]. Poly (2-(2-methoxy ethoxy) ethyl methacrylate), or p(MEO2MA), exhibits both thermoresponsive and ultrasound-responsive properties, making it suitable for the development of ultrasound-responsive SHNPs. These polymers enable drug loading at 4 °C, maintaining shape at 37 °C, and facilitating the transport of drug-loaded nanoparticles at physiological temperature. When subjected to ultrasound, the polymer changes hydrophobicity and conformation, releasing drugs [111]. Top of Form.

Electro responsive SHNP

This SHNP employs a mechanism wherein drug release is modulated through the application of a mild electric field. This approach offers a straightforward coupling with bioelectronics, enabling precise control over the release of drugs. Fang et al. devised a method to fabricate dual-responsive SHNPs, wherein drug release is regulated by both an external magnetic field and temperature variations. Their technique involves coating the surface of silica nanoparticles with a combination of electro-sensitive and thermosensitive copolymers. Consequently, the release of drugs is influenced by the interplay of these external stimuli. Applying a 0.5 Hz alternative electric field alongside the stimuli leads to a twofold increase in drug release compared to using a single stimulus [112].

Biocompatibility and toxicological concerns of hybrid nanoparticles

Both LPHNPs and SHNPs could exhibit cytotoxicity, hemolytic susceptibility, or organ toxicity depending on their composition, size, and surface properties. LPHNPs tend to be more biocompatible owing to their lipid and polymer composition, which closely resembles biological membranes and provides less chance of developing toxic reactions. However, their choice of lipids (e.g., DPPC, DSPE-PEG) and polymers (e.g., PLGA, PCL) could affect biodegradability and allocate the probability of tissue accumulation. Reports have claimed that PLGA nanoparticles are generally safe due to prolonged degradation time, limiting long-term toxicity [113]. However, some PLGA degradation products may mediate local inflammatory or cytotoxic responses at high concentrations. To minimize these effects, surface modifications such as PEGylation (for instance, DSPE-PEG) are often performed, which otherwise result in enhanced biocompatibility and reduced interactions with serum proteins, hence reducing toxicity [114].

SHNPs, especially mesoporous silica nanoparticles, are not only biocompatible but are also feared for inducing oxidative stress and inflammation when poorly functionalized. Evidence exists that unmodified silica nanoparticles activate the immune system and cause inflammation [86]. However, coating SHNPs with biocompatible polymers, such as PEG, or using surface modifications to decrease their surface charge or porosity may greatly ameliorate these toxicological concerns. Furthermore, controlled biodegradation and body clearance protect from cumulative toxicity [87].

LPHNPs are generally considered to be less immunogenic owing to the biocompatibility of lipid and polymer components. The PEGylation of nanoparticles is a widely used strategy to minimize immunogenicity by evading recognition from the RES, thereby preventing rapid clearance and increasing circulation in the body [114]. The studies have reported that PEGylated LPHNPs show much lower immunogenicity, decreasing the chances of activating the immune system in drug delivery applications.

On the contrary, the bare silica surfaces of SHNPs induce immune responses through macrophage and other immune cell activation mechanisms. To that effect, surface modifications with PEGylation and the utilization of biomolecular coatings, for example, polyethyleneimine, have been found to suppress the inflammatory reaction and enhance their biocompatibility [86]. There is also a possibility of reducing recognition by immune cells by using biodegradable silica materials or incorporating targeting moieties like antibodies to alleviate immunogenicity further.

In conclusion, while hybrid nanoparticles such as LPHNPs and SHNPs have potential toxicological and immunogenic hazards, proper formulations and surface modification with biocompatible and biodegradable materials can readily address these concerns. Such improvements guarantee the safety and effectiveness of hybrid nanoparticles for drug delivery applications [87, 115].

CONCLUSION

Hybrid nanoparticles with high drug loading efficiency and specific targeting efficiency with higher circulation time in the body can help get specific targeting to the tumor cell. It will reduce the side effects without harming normal tissue. Recent advancements in lipid polymer hybrid nanoparticles (LPHNPs), like magnetic responsive nanoparticles and ultra-small hybrid nanoparticles, help target cancer cells more specifically. ATRA-based differentiation gives promising results in treating myeloma with the least side effects compared to conventional treatments. LPHNPs incorporated with quantum dots, gold, and superparamagnetic iron oxide are practical innovations in diagnosing cancer. The porous nature of the silica allowed the incorporation of nanosystem into the pores and achieved high drug loading and protection from external stimuli. Silica allows the attachment of various ligands on the surface so that active targeting can be achieved and help reduce the side effects. Various endogenous stimuli (pH, enzyme, redox reaction) and exogenous stimuli (light, temperature, magnetic, ultra-sonic, electro) responsive hybrid nanoparticles provide promising results in cancer treatment and diagnosis. Peptides and aptamers show great promise in targeting ligands in systemic, highly hybrid nanoparticle systems to improve drug delivery systems' specificity, efficacy, and stability. Peptides can easily be synthesized with good specificity but have binding affinity and stability disadvantages. In contrast, aptamers provide better binding affinity and stability but are poorly synthesized and have a reduced targeting range. Future considerations for hybrid nanoparticle systems involve enhancing formulation stability, optimizing the clinical use of hybrid nanoparticles through preclinical and clinical trials, and working through regulatory concerns that ensure safe and efficacious therapeutic results. In this way, if these problems are solved, cancer treatment and other therapeutic fields may be revolutionized by hybrid nanoparticle-drug delivery systems.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We, the authors, gratefully acknowledge the support of the Manipal College of Pharmaceutical Science and the Manipal Academy of Higher Education throughout the review.

FUNDING

This review received no specific grant or funding from any sources.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors have made equal contributions to this work.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Davis ME, Chen ZG, Shin DM. Nanoparticle therapeutics: an emerging treatment modality for cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7(9):771-82. doi: 10.1038/nrd2614, PMID 18758474.

Sailor MJ, Park JH. Hybrid nanoparticles for detection and treatment of cancer. Adv Mater. 2012;24(28):3779-802. doi: 10.1002/adma.201200653, PMID 22610698.

Muthu MS, Leong DT, Mei L, Feng SS. Nanotheranostics application and further development of nanomedicine strategies for advanced theranostics. Theranostics. 2014;4(6):660-77. doi: 10.7150/thno.8698, PMID 24723986.

Mahzabin A, Das B. A review of lipid polymer hybrid nanoparticles as a new generation drug delivery system. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2020;12(1):65-75. doi: 10.13040/IJPSR.0975-8232.12(1).

Fang RH, Chen KN, Aryal S, Hu CM, Zhang K, Zhang L. Large scale synthesis of lipid polymer hybrid nanoparticles using a multi-inlet vortex reactor. Langmuir. 2012;28(39):13824-9. doi: 10.1021/la303012x, PMID 22950917.

Nakamura Y, Mochida A, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H. Nanodrug delivery: is the enhanced permeability and retention effect sufficient for curing cancer? Bioconjug Chem. 2016;27(10):2225-38. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.6b00437, PMID 27547843.

Elzoghby AO, Hemasa AL, Freag MS. Hybrid protein inorganic nanoparticles: from tumor-targeted drug delivery to cancer imaging. J Control Release. 2016 Dec 10;243:303-22. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.10.023, PMID 27794493.

Elzoghby AO, Samy WM, Elgindy NA. Protein-based nanocarriers as promising drug and gene delivery systems. J Control Release. 2012;161(1):38-49. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.04.036, PMID 22564368.

Elzoghby AO, Helmy MW, Samy WM, Elgindy NA. Novel ionically crosslinked casein nanoparticles for flutamide delivery: formulation characterization and in vivo pharmacokinetics. Int J Nanomedicine. 2013 May 13;8:1721-32. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S40674, PMID 23658490.

Kim J, Kim HS, Lee N, Kim T, Kim H, Yu T. Multifunctional uniform nanoparticles composed of a magnetite nanocrystal core and a mesoporous silica shell for magnetic resonance and fluorescence imaging and for drug delivery. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2008;47(44):8438-41. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802469, PMID 18726979.

Kaur P, Garg T, Rath G, Goyal AK. Boosting the skin delivery of curcumin through lipid polymer hybrid nanoparticles. Int J Appl Pharm. 2021;13(1):261-7. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2021.v13i1.39645.

Iranshahy M, Hanafi Bojd MY, Aghili SH, Iranshahi M, Nabavi SM, Saberi S. Curcumin loaded mesoporous silica nanoparticles for drug delivery: synthesis biological assays and therapeutic potential a review. RSC Adv. 2023;13(32):22250-67. doi: 10.1039/D3RA02772D, PMID 37492509.

Dave V, Tak K, Sohgaura A, Gupta A, Sadhu V, Reddy KR. Lipid polymer hybrid nanoparticles: synthesis strategies and biomedical applications. J Microbiol Methods. 2019 May;160:130-42. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2019.03.017, PMID 30898602.

Al Jamal WT, Kostarelos K. Liposomes: from a clinically established drug delivery system to a nanoparticle platform for theranostic nanomedicine. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44(10):1094-104. doi: 10.1021/ar200105p, PMID 21812415.

Krishnamurthy S, Vaiyapuri R, Zhang L, Chan JM. Lipid-coated polymeric nanoparticles for cancer drug delivery. Biomater Sci. 2015;3(7):923-36. doi: 10.1039/c4bm00427b, PMID 26221931.

Clawson C, Ton L, Aryal S, Fu V, Esener S, Zhang L. Synthesis and characterization of lipid polymer hybrid nanoparticles with pH-triggered poly(ethylene glycol) shedding. Langmuir. 2011;27(17):10556-61. doi: 10.1021/la202123e, PMID 21806013.

Wu B, Lu ST, Zhang LJ, Zhuo RX, Xu HB, Huang SW. Codelivery of doxorubicin and triptolide with reduction-sensitive lipid polymer hybrid nanoparticles for in vitro and in vivo synergistic cancer treatment. Int J Nanomedicine. 2017 Mar 8;12:1853-62. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S131235, PMID 28331310.

Chen L, Zhou X, Shi Y, Gao B, Wu J, Kirk TB. Green synthesis of lignin nanoparticle in aqueous hydrotropic solution toward broadening the window for its processing and application. Chem Eng J. 2018 Aug 15;346:217-25. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2018.04.020.

Poudel BK, Gupta B, Ramasamy T, Thapa RK, Youn YS, Choi HG. Development of polymeric irinotecan nanoparticles using a novel lactone preservation strategy. Int J Pharm. 2016;512(1):75-86. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2016.08.018, PMID 27558884.

Ramasamy T, Tran TH, Choi JY, Cho HJ, Kim JH, Yong CS. Layer-by-layer coated lipid polymer hybrid nanoparticles designed for use in anticancer drug delivery. Carbohydr Polym. 2014 Feb 15;102:653-61. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.11.009, PMID 24507332.

Hadinoto K, Sundaresan A, Cheow WS. Lipid polymer hybrid nanoparticles as a new generation therapeutic delivery platform: a review. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2013;85(3 Pt A):427-43. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2013.07.002, PMID 23872180.

Sengupta S, Eavarone D, Capila I, Zhao G, Watson N, Kiziltepe T. Temporal targeting of tumour cells and neovasculature with a nanoscale delivery system. Nature. 2005;436(7050):568-72. doi: 10.1038/nature03794, PMID 16049491.

Seedat N, Kalhapure RS, Mocktar C, Vepuri S, Jadhav M, Soliman M. Co-encapsulation of multi-lipids and polymers enhances the performance of vancomycin in lipid polymer hybrid nanoparticles: in vitro and in silico studies. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2016 Apr 1;61:616-30. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2015.12.053, PMID 26838890.

Javaid A, K AA, Sharma KK, P MS, Verma A, Mudavath SL. Niacin-loaded liquid crystal nanoparticles ameliorate prostaglandin D2-mediated niacin-induced flushing and hepatotoxicity. ACS Appl Nano Mater. 2024;7(1):444-54. doi: 10.1021/acsanm.3c04649.

Wang Y, Kho K, Cheow WS, Hadinoto K. A comparison between spray drying and spray freeze drying for dry powder inhaler formulation of drug-loaded lipid polymer hybrid nanoparticles. Int J Pharm. 2012;424(1-2):98-106. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.12.045, PMID 22226876.

Hasan W, Chu K, Gullapalli A, Dunn SS, Enlow EM, Luft JC. Delivery of multiple siRNAs using lipid-coated PLGA nanoparticles for treatment of prostate cancer. Nano Lett. 2012;12(1):287-92. doi: 10.1021/nl2035354, PMID 22165988.

Rahman M, Alharbi KS, Alruwaili NK, Anfinan N, Almalki WH, Padhy I. Nucleic acid loaded lipid polymer nanohybrids as novel nanotherapeutics in anticancer therapy. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2020;17(6):805-16. doi: 10.1080/17425247.2020.1757645, PMID 32329630.

Feng Q, Zhang L, Liu C, Li X, Hu G, Sun J. Microfluidic-based high throughput synthesis of lipid polymer hybrid nanoparticles with tunable diameters. Biomicrofluidics. 2015;9(5):52604. doi: 10.1063/1.4922957, PMID 26180574.

Mandal B, Mittal NK, Balabathula P, Thoma LA, Wood GC. Development and in vitro evaluation of core-shell type lipid polymer hybrid nanoparticles for the delivery of erlotinib in non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2016 Jan 1;81:162-71. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2015.10.021, PMID 26517962.

Huang X, Lee RJ, Qi Y, Li Y, Lu J, Meng Q. Microfluidic hydrodynamic focusing synthesis of polymer lipid nanoparticles for siRNA delivery. Oncotarget. 2017;8(57):96826-36. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18281, PMID 29228574.

Zhang LI, Zhang L. Lipid polymer hybrid nanoparticles: synthesis characterization and applications. Nano Life. 2010;1(01n02):163-73. doi: 10.1142/S179398441000016X.

Betancourt T, Brown B, Brannon Peppas L. Doxorubicin loaded PLGA nanoparticles by nanoprecipitation: preparation characterization and in vitro evaluation. Nanomedicine (Lond). 2007;2(2):219-32. doi: 10.2217/17435889.2.2.219, PMID 17716122.

Fang RH, Aryal S, Hu CM, Zhang L. Quick synthesis of lipid polymer hybrid nanoparticles with low polydispersity using a single-step sonication method. Langmuir. 2010;26(22):16958-62. doi: 10.1021/la103576a, PMID 20961057.

Chen Y, Chen M, Zhang Y, Lee JH, Escajadillo T, Gong H. Broad spectrum neutralization of pore‐forming toxins with human erythrocyte membrane coated nanosponges. Adv Healthc Mater. 2018;7(13):e1701366. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201701366, PMID 29436150.

Zhang Q, Honko A, Zhou J, Gong H, Downs SN, Vasquez JH. Cellular nanosponges inhibit SARS-CoV-2 infectivity. Nano Lett. 2020;20(7):5570-4. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c02278, PMID 32551679.

Parvez S, Yadagiri G, Gedda MR, Singh A, Singh OP, Verma A. Modified solid lipid nanoparticles encapsulated with amphotericin B and paromomycin: an effective oral combination against experimental murine visceral leishmaniasis. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):12243. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-69276-5, PMID 32699361.

Wang F, Gao W, Thamphiwatana S, Luk BT, Angsantikul P, Zhang Q. Hydrogel retaining toxin absorbing nanosponges for local treatment of methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus infection. Adv Mater. 2015;27(22):3437-43. doi: 10.1002/adma.201501071, PMID 25931231.

Ma P, Li T, Xing H, Wang S, Sun Y, Sheng X. Local anesthetic effects of bupivacaine loaded lipid polymer hybrid nanoparticles: in vitro and in vivo evaluation. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017 May;89:689-95. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.01.175, PMID 28267672.