Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 4, 2025, 497-510Original Article

REPURPOSED SIMVASTATIN-LOADED NANOSTRUCTURED LIPID CARRIERS: OPTIMIZATION, CHARACTERIZATION AND EVALUATION AGAINST LUNG CANCER

NARGIS ARA, ABDUL HAFEEZ*, SHOM PRAKASH KUSHWAHA, ARCHITA KAPOOR

Faculty of Pharmacy, Integral University, Lucknow-226026, India

*Corresponding author: Abdul Hafeez; *Email: abdulhafeez@iul.ac.in

Received: 06 Feb 2025, Revised and Accepted: 02 Jun 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: Repurposed Simvastatin (SMV) is being investigated for the treatment of lung malignancies. However, its inadequate solubility in water and formulation constraints are the potential challenges for its use against lung cancer. This study aimed at synthesis of SMV-loaded Nanostructured Lipid Carriers (SMV-NLC) for lung cancer management.

Methods: Emulsification and probe sonication approach was chosen for the formulation of NLCs. A three-factor, three-level Box-Behnken design was utilized for the development of SMV-NLC formulation. The independent variables selected were total lipid concentration (%w/w), solid lipid: liquid lipid ratio, and surfactant concentration (%w/w). Screening of components was performed based on SMV solubility and SMV-excipient compatibility studies.

Results: Optimized SMV-NLC showed a particle size of 209.8±1.8 nm, low polydispersity index (0.319±0.14), negative zeta potential (-20.35 mV) and good entrapment efficiency (73.51±4.22%). Transmission electron microscopy examination revealed spherical shape of NLC with validation of nanometric size. Fourier Transform Infrared analysis revealed the entrapment of the SMV within the lipid matrix of NLC. SMV release of 86.97±1.7% was obtained from NLC after 24 h with sustained release characteristics. In vitro cytotoxic activity against A549 cell lines (lung cancer) showed IC50of 11.34±0.12 and 30.26±0.14 µg/ml for SMV-NLC and SMV-suspension, respectively.

Conclusion: The developed SMV-NLC may be utilized as an effective platform for the management of lung cancer.

Keywords: Simvastatin, Nanostructured lipid carriers, Box-behnken design, Anticancer activity, In vitro drug release, A549 cell line

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i4.53890 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Lung-related cancers are the biggest reason for death internationally, along with more than two million diagnosis and 1.8 million fatalities per year. Lung cancer is among the three most widespread form of cancer in both men and women, following prostate and breast cancer [1]. Nevertheless, lung cancer prevalence and mortality rates vary greatly over across nations, reflecting differences in nicotine consumption habits, risk factors associated with the environment, and inheritance [2]. There are two categories of lung cancer according to the World Health Organization: non-small cell lung cancer, which is responsible for 80 to 85% of all instances, and small cell lung cancer, which accounts for the fifteen percent that remains [3-5]. In the past few decades, the scientific knowledge of cancer in the lungs has advanced dramatically. Despite of significant breakthroughs in lung cancer therapy, anticancer treatment efficacy among cancer patients is still inadequate [6]. Furthermore, because traditional chemotherapy does not target cancer cells specifically, it might kill healthy cells as well, resulting in systemic toxicity in patients. As a result, alternative therapeutic options remain in demand. Perhaps the most prevalent techniques are nanocarrier-based drug administration [7].

Over the past few years, numerous nanocarrier-based drug-delivery techniques have been created for cancer therapy. These systems include liposomes, polymeric micelles, nanoparticles, nanoemulsions, drug-polymer conjugates etc. [8-10]. However, these systems come with several prospective limitations, including restricted loading of drug and drug leaking during storage [11]. Furthermore, in the past decades, several nanoparticulate structures based on lipids had also been created to increase drug loading and release characteristics of anticancer medicines [12]. Lipids have several benefits, including their great biocompatibility and biodegradability [13, 14]. The incorporation of solid lipids in the synthesis of nanoparticle is a particularly appealing option for overcoming the constraints of existing nanocarrier-based drug delivery methods, and there is considerable interest in the possible use of Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLNs). These systems degrade at a more gradual rate than liposomes, polymeric micelles, nanoparticles, nanoemulsions, and they may be generated in huge quantities at a low cost [15, 16]. However, SLNs may be restricted in terms of drug loading and expulsion during storage due to lipid matrix crystallization. To address the limitations of SLNs, Nanostructured Lipid Carriers (NLCs) have emerged as the second generation of lipidic nanoparticles [17, 18]. NLCs are produced from appropriate and biodegradable lipids (liquid and solid) and emulsifiers, and they are classified into three categories depending on lipid content and formulation parameters: imperfect, amorphous, and numerous structures [19]. In general, NLCs are formed by nano-emulsifying lipids in an aqueous solution containing water-soluble surfactants/emulsifiers [20]. NLC components are compatible with most emulsifiers (such as lecithin, sodium glycocholate, polysorbate 80) [21]. A research report indicated that NLCs versatility as a pharmaceutical carrier makes them a potential generic stage for the administration of numerous anticancer cytotoxins [22].

Simvastatin (SMV) is a BCS Class II medication that is commonly used to treat hypercholesterolemia [23]. SMV is a possible blocker of the enzyme known as 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase, which has lately been identified as extremely safe for long-term use [24]. HMG-CoA reductase is the restricting enzyme within the cholesterol manufacture pathway; hence, inhibiting it is crucial for lowering cholesterol production [25]. In recent pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies, SMV was found to have a variety of effects (improved microvascular function of cells, anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and immune-modulatory properties) unrelated to its capacity to lower cholesterol [26]. SMV's anti-cancer potential has sparked significant attention as a medicine for cancer cell proliferation and apoptosis activation [27]. SMV is currently under investigation as a repurposed medicine in cancer care and preventive measures for different types of prototypes, particularly lung, liver, breast, skin, prostate, rectal, and intestinal cancers [28]. Predominately being lipophilic, SMV may easily penetrate further into membranes via passive diffusion, resulting in widespread distribution in many tissues [29]. SMV is a lipophilic medication with a low water solubility of ~1.45 µg/ml and a bioavailability of around 5%. [30, 31]. To increase SMV effectiveness and bioavailability, suitable lipid matrix with adequate physicochemical characteristics can be utilized. The development of second-generation NLCs may aid in higher drug encapsulation, prolonged release of drug, and improvement drug entrapment with less leakage during storage.

As a result, the current study recommends development and optimization of SMV-loaded NLCs as a novel lung cancer therapy platform. In this work, oleic acid (OA) was employed as a liquid lipid and glyceryl monostearate (GMS) to be solid lipid in order to formulate NLCs. It is reported that using medium-chain fatty acids and triglycerides produces smaller particle-sized NLCs when compared to long-chain fatty acids and triglycerides [32]. In pulmonary drug delivery, GMS helps form inhalable lipid nanoparticles, ensuring prolonged lung retention and better therapeutic effects, while OA functions as a permeability enhancer, facilitating drug penetration through lung epithelial membranes. Their combination is ideal for pulmonary drug delivery systems. NLC was stabilized by using Tween 80 as surfactant. Tween 80 is a non-ionic surfactant that improves drug dispersion and stabilizes inhalable formulations. It helps in reducing surface tension, making drug particles more suitable for aerosolization and lung deposition. These excipients are ideal for pulmonary drug delivery systems and are widely used in nanoparticles, dry powder inhalers, and nebulized formulations for treating asthma, COPD, tuberculosis, and lung infections [33, 34]. The method known as Box-Behnken was utilized in order to enhance and assess results of various factors on dependent responses (particles, size, entrapment efficiency and in vitro drug release for 24 h). After optimization, SMV-NLC was fully characterized and its effect on human lung cancer cell line (A549 cells) was tested.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

The drug (SMV) was bought from RG and Sons Scientific Solution, Lucknow, India. GMS, Stearic Acid (octadecanoic acid) (SA), Bees Wax (BW), Tween®80 (Polyoxyethylene sorbitan monooleate, Polysorbate 80), Tween®20 (Polyethylene glycol sorbitan monolaurate), Span®80 (Sorbitan monolaurate), Castor Oil (CO), Isopropyl Myristate (propan-2-yl tetradecanoate) (IPM) and OA (cis-9-octadecenoic acid) extrapure were procured through Procurement Cell, Integral University, Lucknow, India. A549 lung cancer cell line Procured from NCCS Pune, India. The remaining chemicals were obtained from Integral University's chemical store and were all of analytical quality.

Screening of excipients

Solubility studies

The solubility of SMV was estimated semi-quantitatively with different solid lipids (GMS, SA and BW). The study was conducted using specific methodologies for each category to determine the best excipients for formulation development. The study was carried by introducing 1 mg doses of SMV into melted solid lipids (warm enough to melt them at 5 °C), till it ceased dissolving further. The quantity of solid lipids necessary to dissolve SMV was computed. This method helped determine the ability of solid lipids to solubilize SMV, which was crucial for selecting the most suitable carrier for formulation. To find the medication's solubility in various liquid lipids (OA, IPM, and CO) and surfactants (Tween 80, Tween 20, and Span 80), a sufficient amount of the drug was dissolved in each additive by heating it on a water bath at 40 °C for ten minutes. The mixtures were then vortexed for 48 h at 25 °C and kept at equilibrium for 24 h. Following a 10 min centrifugation at 4000 rpm for the samples, the clear liquid supernatant was transferred. A UV-VIS spectrophotometer (Shimadzu 1800-series) set to analyze the supernatant at 238.8 nm was used to assess the drug's solubility [35–37]. This study helped identify the most suitable excipients (solid lipid, liquid lipid, and surfactant) that provide maximum solubility for SMV. The selection process was data-driven and aimed at optimizing drug solubility and stability.

Drug-excipient compatibility studies

Drug-excipient compatibility studies are essential in pharmaceutical formulation development to ensure that the active pharmaceutical ingredient and excipients do not interact in a way that affects stability, efficacy, or safety [38]. About 10 mg of pure drugs and excipients were weighed separately and in combination (1:1). Individual drug (SMV), individual excipient (GMS, SA and BW) and drug-excipient combinations (SMV+GMS, SMV+SA, SMV+BW) were transferred into different glass vial and appropriately labelled. After each vial was correctly sealed, it was kept in a humidity-controlled room for a period of four weeks. Organoleptic characteristics of the samples, such as colour and texture, were first noted and again at the conclusion of the first, second, third, and fourth weeks in order to determine the physical instability. Any colour change, precipitation, or phase separation indicates possible incompatibility. To identify the chemical instability, samples (SMV, GMS, SMV+GMS) were further used to record the Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectrum using FTIR Spectrophotometer [39]. To create a pellet, the sample was processed using potassium bromide (KBr). The resulting pellet was stored in a disk for examination. A broad range of wave numbers, from 4000 to 400 cm−1, was examined. Any major shifts, disappearance, or formation of new peaks in the FTIR spectra indicate chemical interactions between the drug and excipient.

Synthesis of drug-loaded NLC

Emulsification and probe sonication approach was chosen for the formulation of NLCs because of its reliability, reproducibility, and efficiency in forming stable nano-sized lipid dispersions The Emulsification and Probe Sonication approach is an efficient and reliable method for NLC formulation, making it ideal for drug delivery applications [40–42]. In this process, the lipid and aqueous phases were produced separately using a magnetic stirrer at 60-70 °C. At same temperature (to keep lipids in the molten state), lipid phase comprising liquid (OA) and solid (GMS) lipids was melted and combined. Drug (SMV) continued to stir while it was dissolved in the lipid phase. After the drug had completely dissolved in the lipid phase, an aqueous phase comprising surfactant (Tween 80) was gently added to the lipid phase and thoroughly mixed using a magnetic stirrer at the identical temperature(60–70 °C) to prevent premature solidification of lipids when mixing. Distilled water was added gradually while being constantly stirred on a magnetic stirrer over twenty minutes in order to get the desired final volume. This resulted in the formation of a coarse emulsion (large lipid droplets dispersed in water). The coarse emulsion was exposed to high-shear energy using a probe sonicator (60% amplitude for 30 min, in two cycles), to reduce the particle size of the emulsion droplets to the nano-range and form stable NLCs. Sonication was performed at a lower power range (100–150 W) to prevent overheating and degradation [43]. The high-energy ultrasonic waves break down the larger emulsion droplets into nano-sized lipid particles (NLCs). The ultrasonic cavitation effect (formation and collapse of microscopic bubbles) leads to the formation of uniform nano-sized NLCs.

Experimental design and optimization

For the purpose of optimizing NLC formulation in this investigation, a three-level, three-factor Box-Behnken design (Version 23.1.4, Stat Ease Inc., Minneapolis, MN 55413) had been chosen [44, 45]. Regarding the ultimate optimum formulation, the values at low (represents the minimum concentration used in the study), middle (represents the intermediate concentration), and high (represents the maximum concentration to evaluate the impact of higher levels) of the dependent and independent variables had been selected. The concentration of surfactant used in the creation of NLCs, the ratio of solid to liquid lipid, and the total lipid were all regarded as independent variables. Particle size, entrapment efficiency, and percentage drug release were the three dependent factors examined in the design for the three responses [46], as indicated in table 1. The selection of independent and dependent variables is crucial in an experimental design as it directly influences the optimization process and the final formulation characteristics. The chosen variables were carefully selected based on their scientific significance, practical relevance, and impact on NLC performance [47].

Table 1: Variables in box-behnken design

| Independent variable | Levels | ||

| (-1) | (0) | (+1) | |

| A, Total Lipid (% w/w) | 1 | 3 | 5 |

| B, Solid Lipid: Liquid Lipid | 1 | 2.5 | 4 |

| C, Surfactant (% w/w) | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Dependent variables | Constrains | ||

| Y1, Particle Size (nm) | Minimize | ||

| Y2, Entrapment Efficiency (%) | Maximize | ||

| Y3, Drug Release after 24h (%) | Maximize |

Lipids are the core components of NLCs and influence particle size, drug entrapment, and release profile. The selected range (1–5 %) ensures an adequate lipid matrix to encapsulate the drug while preventing excessive particle aggregation. NLCs are a combination of solid and liquid lipids, which helps prevent crystallization and enhances drug loading. The ratio of solid to liquid lipids impacts: more solid lipids can lead to larger particles, a balanced ratio allows better drug retention and too much solid lipid can slow down drug release, while too much liquid lipid may lead to rapid drug leakage. A lower ratio (1:1) ensures better drug solubilization, while a higher ratio (4:1) provides stability and controlled release. The middle value (2.5:1) serves as a balance point between stability and drug release efficiency. Surfactants stabilize the NLC dispersion by preventing particle aggregation. Higher surfactant levels can enhance drug solubility and entrapment efficiency, but excessive amounts might cause toxicity or destabilization. Below 1%, poor stabilization may cause particle aggregation. Above 3%, excess surfactant could lead to toxicity or excessive surface modification, affecting drug absorption. 2% as the middle value provides optimal stabilization without excessive interference. Dependent variables are the measurable responses that are affected by changes in the independent variables. Smaller NLCs penetrate biological barriers more efficiently, leading to better therapeutic outcomes. A target particle size below 200 nm is ideal for enhanced drug delivery. Entrapment efficiency (EE%) indicates how much drug is successfully loaded into the NLCs. A well-optimized lipid composition increases drug loading, enhancing treatment effectiveness. Drug release kinetics determines how long the drug remains effective in the body. Optimized release profiles ensure therapeutic levels of the drug are maintained over time [48, 49].

In order to develop NLC formulations, a design framework comprising of fifteen trial runs was established. The variables included total lipid (A), solid lipid: liquid lipid (B), and surfactant concentration (C). We looked at the responses, which comprised size (Y1), entrapment efficiency (Y2) and percentage drug release (Y3). The following is the non-linear quadratic equation (1) produced by a computer:

Y = b0+b1A+b2B+b3C+b12AB+b13AC+b23BC+b11A2+b22B2+b33C2. Eq. (1)

In which the coded levels are A, B, and C of independent variables that represent the linear terms; Y is the observed response associated with every combination of factor levels; b0 is an intercept; and b1, b2, and b3 are coefficients of regression determined from the experimental run's observed experimental values for Y [50]. The experiment's design allowed for the analysis of these data. The model that fit the best was chosen. It was discovered that the optimization technology had the least amount of variation in the NLCs' size range, the highest entrapment efficiency, and the highest percentage of drug release. Ultimately, the optimal option was chosen for additional characterisation.

Characterization of optimized NLC formulation

Particle size and polydispersity index (PDI)

The formulations' particle sizes were analyzed at room temperature (25 C) by Zetasizer (Advance Series-Lab blue Software version 3.31, Malvern Panalytical Ltd, UK). The samples were treated with purified water in a clear, disposable cell, and the results were recorded. The PDI was calculated as a homogeneity metric. A homogenous distribution of particles is indicated by small PDI values (<0.5), whereas substantial heterogeneity among the particles is indicated by PDI values (>0.5) [51]. Each measurement was carried out in triplicate (n=3).

Entrapment efficiency

The efficacy of entrapment was ascertained by centrifuging 2 ml of formulations at 10000 rpm for 60 min, and after that, one ml of the supernatant was obtained and appropriately diluted with pH 7.4 phosphate buffer. Lastly, a UV-VIS Spectrophotometer (UV-1800 SHIMADZU) was used to assess the free drug at 238.8 nm. The following equation (2) was used to determine EE [52].

Eq. (2)

Eq. (2)

Zeta potential

Zeta potential was characterized by electrophoretic mobility technique using Zetasizer. Zeta potential was tested to assess the stability of optimized NLC. It represents the electrical charge on the particles. Zeta potentials of less than −30 mV and more than+30 mV are classified as strongly anionic and strongly cationic, respectively, whereas those between ±10 mV is regarded roughly neutral [53]. Zeta potential can influence a nanoparticle's ability to penetrate membranes since the majority of cellular membranes possess a negative charge. Catalytic particles often exhibit more toxicity when it comes to cell wall disintegration [54].

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

Transmission electron microscopy (Thermo Fisher Scientific TALOS L120C, SPER, Jamia Hamdard, New Delhi, India) was employed to examine the SMV-NLC's structure. A suitable concentration of the samples was obtained, and they were sonicated for 8 to 10 min using a bath sonicator. On the carbon-coated grid with a 300/200 mesh, a drop of sample was applied film side up. For the negative staining process, 1% phosphotungstic acid was used. After the samples were incubated for 30 to 90 seconds, extra liquid was wiped off using a filter paper. For TEM investigation, the air dried and was inspected [55].

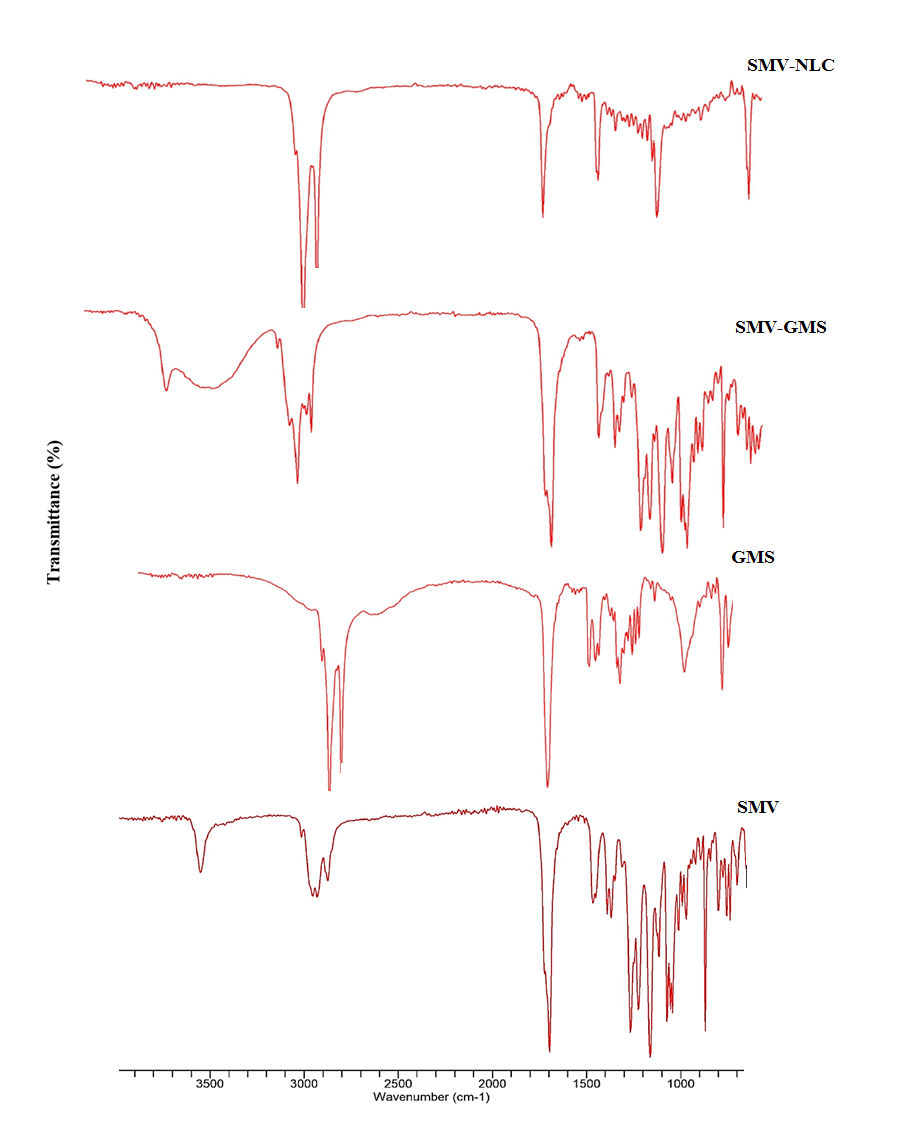

FTIR analysis

With an Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectrophotometer (Shimadzu), the FTIR spectra of SMV, GMS, physical mixing of SMV with GMS, and SMV-NLC were recorded and analysed between 4000 and 400 cm-1 wavelengths. In a nutshell, pellets were created after samples were mixed using KBr powder. The distinctive peaks were noted and contrasted [56].

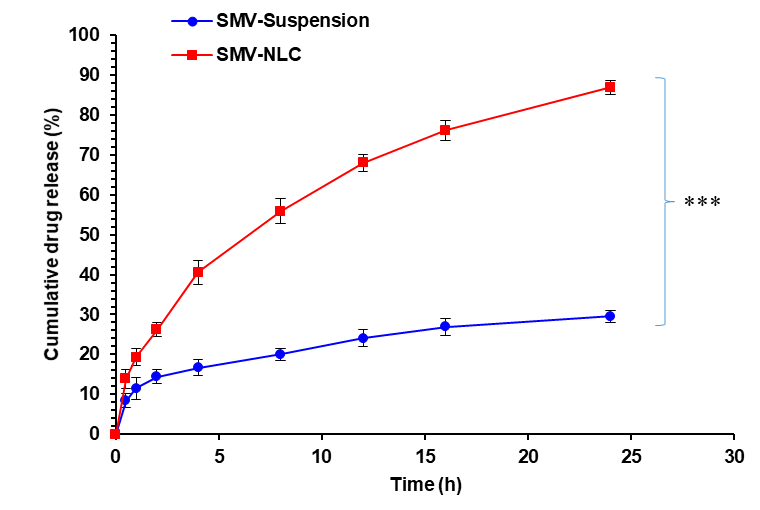

In vitro drug release studies

The in vitro release behaviour of optimized SMV-NLC and SMV-suspension had been studied employing the dialysis-bag diffusion method. Phosphate buffer with 7.4 pH served as the dissolving media. The membrane used for dialysis was initially soaked in a 7.4 pH phosphate buffer for a whole day to ensure proper hydration and permeability. Different configurations of SMV-NLC and SMV-suspension (2 ml) were added to the dialysis bags. After that, the bag used for dialysis was placed in 100 ml of dissolving solution that was kept at 37±0.5 °C while being constantly stirred at 100 rpm to ensure uniform mixing and prevent concentration gradients. This setup mimics in vivo conditions, where body fluids continuously remove released drugs. Samples of one milliliter were pipetted out from the medium at various time gaps for up to twenty-four hours, and fresh dissolving medium was used to maintain the sink condition, ensuring continuous drug diffusion. The UV-Vis spectrophotometer measured the quantity of SMV emitted at 238.8 nm, the wavelength specific to SMV absorption. Three runs of the experiment each were made and the data were examined by graphing the percentage cumulative drug release against time to observe the release pattern. First-order, zero-order, Higuchi's and Korsmeyer-Peppas's models were among the mathematical models used to study the release kinetics of SMV from SMV-NLC [57, 58]. If SMV-NLC follows zero-order, it means the drug is released at a uniform rate, providing prolonged therapeutic effects. If SMV-NLC follows first-order, it means the drug is released faster initially and slows down over time. If SMV suspension follows this model, it suggests a faster depletion of free drug molecules. If SMV-NLC follows Higuchi’s model, it confirms drug release is diffusion-controlled, indicating a sustained release profile. The Korsmeyer-Peppas model is a semi-empirical equation used determine whether drug release is controlled by Fickian diffusion, non-Fickian transport, or erosion mechanisms. If release exponent 0.5<n<1.0, SMV-NLC release is non-Fickian transport (combination of diffusion and matrix relaxation) and if release exponent n<0.5, SMV-NLC release is Fickian diffusion (drug release mainly by diffusion) [59].

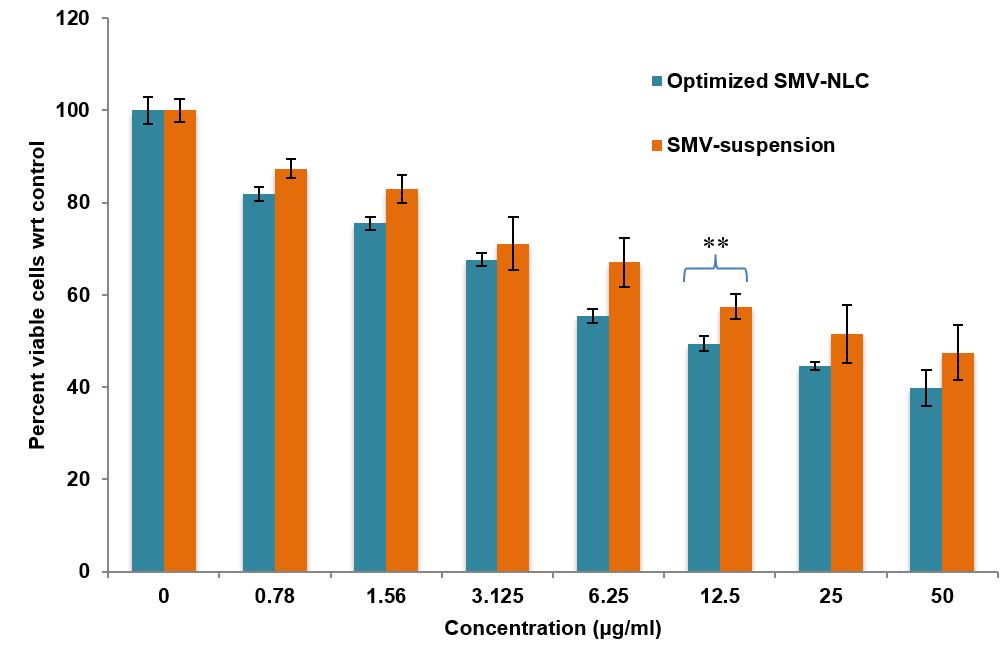

In vitro cell cytotoxicity studies

Cytotoxicity of the optimized NLC formulation and SMV suspension was investigated on A549 cell lines (Human lung cancer) employing MTT Assay process. The 96-well plate containing 10,000 cells per well was incubated for 24 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in DMEM medium (Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium-AT149-1L) treated with ten percent FBS (Fetal Bovine Serum-HIMEDIA-RM 10432) and one percent antibiotic solution. The very following day, test sample (SMV-suspension and SMV-NLC) dosages ranging from 0.78 to 50 µg/ml were used to treat cells. Control cells were those that had not received any treatment. The MTT mixture was incorporated into the cell culture and cultured for an additional two hours after the first 24 h culture period. The culture filtrate was collected at the final stage of the experiment, and the cell layer matrix was dissolved in 100 μl of Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO–SRL–Cat no.–67685). The results were read at 540 and 660 nm using an Elisa plate reader (iMark, Biorad, USA). The IC50 was computed using the Graph Pad Prism-6 program. Images were taken using an AmScope digital camera (10 MP Aptima CMOS) under an inverted microscope (Olympus ek2) [60, 61].

Statistical analysis

All the results were presented as mean±standard deviation (SD, n=3). Significance of the experimental data was examined by Tukey’s one-way ANOVA using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software Inc., USA, version 10.2.3); where p<0.05, was considered as significant statistically.

RESULTS

Solubility studies

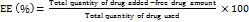

The solubility of drug was determined in different solid lipids (GMS, SA, and BW), liquid lipids (OA, CO, IPM) and surfactants (Tween 80, Tween 20, Span 80), and results are presented in fig. 1. Solid lipids help in controlling drug release and stabilizing the formulation. The drug showed the highest solubility in GMS at 30.52±0.45 mg/g, lower solubility in SA at 15.37 mg/g and the lowest solubility was observed in BW at 8.18 mg/g. Liquid lipids enhance drug solubility and improve absorption. The drug showed the highest solubility in OA at 14.71±0.55 mg/ml, moderate solubility in IPM at 9.28 mg/ml and the lowest solubility in CO at 7.73 mg/ml. Surfactants help in stabilizing formulations and enhancing drug dispersion. The drug showed the highest solubility in Tween 80 at 11.06±0.63 mg/ml, making it the most effective surfactant. The drug showed lower solubility in Tween 20 (4.30 mg/ml) and the least solubility in Span 80 (2.33 mg/ml). Since GMS, OA and Tween80 provided the highest solubility, they were selected as solid lipid, liquid lipid and surfactant, respectively, for formulation development. Similar results are also reported for the solubility of SMV in different excipients by Munir et al., 2014 [62]. Further, GMS increases drug stability and permits controlled release; it was chosen to make NLCs. In formulation development, OA was chosen as a liquid lipid because it enhances the solubility and absorption of lipophilic drugs. OA is a monounsaturated fatty acid that enhances drug permeability across biological membranes. It is widely used in lipid-based formulations like emulsions and lipid nanoparticles [63]. Tween 80 was chosen as a surfactant because it lowers surface tension and increases the solubility and bioavailability of drugs that are not very soluble. This means that these substances can be considered ideal candidates for developing a formulation for the drug that will enhance its solubility, stability, and bioavailability [64].

Fig. 1: Solubility of SMV in solid lipids, liquid lipids and surfactants. Data presented as mean±SD, n=3

Drug-excipient compatibility studies

Over the storage time, the visual observations of the samples showed no notable changes, suggesting physical compatibility between SMV and excipients. As a result, no physical instabilities were seen in drug/drug-excipient combinations. In order to verify the chemical stability of SMV and GMS, FTIR spectroscopy was utilized and data was interpreted, as shown in fig. 7. The O–H stretching vibration corresponds to hydrogen bonding or hydroxyl (O–H) groups present in SMV and GMS. In the SMV+GMS mixture, the O–H peak remains nearly unchanged (3196.30 cm⁻¹ compared to individual values of 3198.82 cm⁻¹ and 3199.82 cm⁻¹). No major peak shift or disappearance indicates that there is no strong chemical interaction affecting hydroxyl groups. The C=O stretching vibration corresponds to the carbonyl (ketone) functional group present in SMV and GMS. In the SMV+GMS combination, the C=O peak appears at 1717.43 cm⁻¹, which is very close to the original peaks of SMV (1713.61 cm⁻¹) and GMS (1718.34 cm⁻¹). The ketone functional group remains stable, ensuring chemical compatibility. The presence of characteristic functional group peaks in SMV+GMS (without major shifts or new peaks) suggests that no chemical interactions or degradation occurred. No major shifts in FTIR peaks indicate chemical compatibility of SMV with GMS. As a result, no chemical instabilities were seen in the drug-excipient combination as represented in table 5. Similar results are also for pure SMV and with excipients during development of proliposomes [65].

Optimization of experimental data by design-expert software

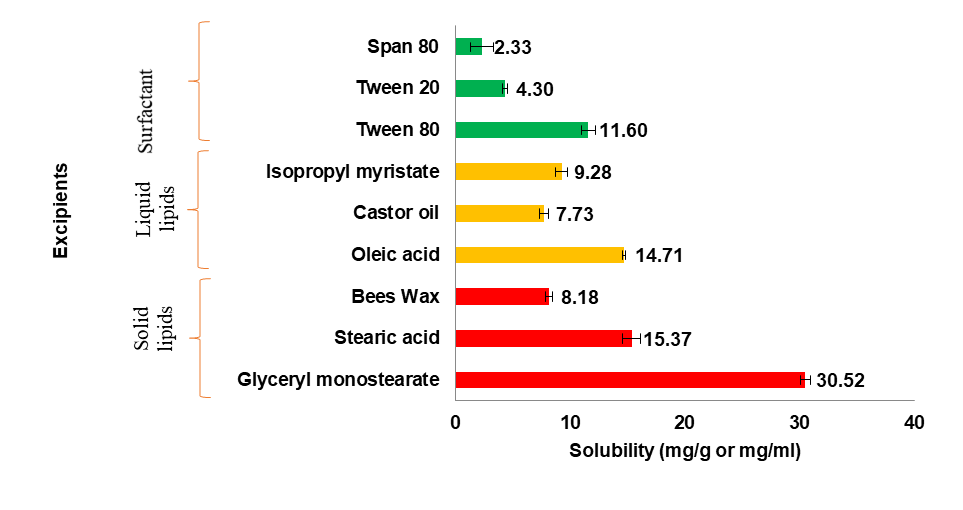

To optimize the SMV-NLC formulation, fifteen experimental runs using a 3-level and 3-factor design—as advised by box-behnken statistical design—were carried out. The responses of particle size, entrapment efficiency, and percentage drug release (during 24 h) ranged between 151.5±1.3 and 257.1±1.1 nm, 68.67±3.91 to 93.05±1.22 %, and 61.92±1.9 to 95.67±1.5 % in all 15 formulations (table 2). A quadratic polynomial model was identified as the best-fitting model based on the response data as shown in table 3. It captures both linear and interaction effects of independent variables and it is more accurate than simple linear models for predicting optimal formulation. Table 3 provides an overview of the regression analysis findings for each of the three answers (Y1, Y2, and Y3). All three of the dependent variables' anticipated R2 values were discovered to be quite consistent to the adjusted R2 values, or>0.99 (p =<0.0001). In polynomial equations, a factor with a positive sign signifies that the answer rises with the factor; conversely, a factor with a negative sign implies that the reaction falls with the factor. A quantitative comparison between the observed and expected values of the reactions is shown in fig. 2, to check data reproducibility. These graphs aid in determining the reproducibility of the experimentally collected data for the dependent variable.

Table 2: Box-behnken experimental design for SMV-NLC with observed responses

| Run | Independent variables | Dependent variables | |||||||

| A | B | C | Observed Y1 (nm)±SD (n=3) | Predicted Y1 (nm) | Observed Y2 (%)±SD (n=3) |

Predicted Y2 (%) | Observed Y3 (%)±SD (n=3) | Predicted Y3 (%) | |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 151.5±1.3 | 152.33 | 79.86±1.48 | 79.73 | 95.67±1.5 | 95.94 |

| 2 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 233.4±2.2 | 235.68 | 93.05 ±.122 | 92.94 | 78.25±1.9 | 78.49 |

| 3 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 176.4±1.5 | 174.13 | 86.96±0.60 | 87.07 | 91.42±2.8 | 91.18 |

| 4 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 257.1±1.1 | 256.28 | 91.91±1.35 | 92.04 | 83.21±2.1 | 82.95 |

| 5 | 1 | 2.5 | 1 | 157.6±2.6 | 159.40 | 71.74±2.39 | 71.67 | 93.14±2.2 | 93.26 |

| 6 | 5 | 2.5 | 1 | 237.9±2.3 | 238.25 | 79.45±1.49 | 79.37 | 71.07±2.0 | 71.21 |

| 7 | 1 | 2.5 | 3 | 153.6±1.6 | 153.25 | 68.67±3.91 | 68.75 | 88.02±2.3 | 87.88 |

| 8 | 5 | 2.5 | 3 | 241.7±2.1 | 239.90 | 79.15±2.95 | 79.22 | 84.37±1.9 | 84.25 |

| 9 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 230.8±1.1 | 228.18 | 81.95±3.91 | 82.15 | 61.92±1.9 | 61.53 |

| 10 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 237.6±3.0 | 238.08 | 84.77±2.95 | 84.73 | 79.24±2.4 | 79.36 |

| 11 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 215.1±1.2 | 214.63 | 79.93±1.04 | 79.97 | 83.46±2.4 | 83.34 |

| 12 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 244.5±2.3 | 247.13 | 84.03±1.42 | 83.83 | 64.82±2.5 | 65.21 |

| 13 | 3 | 2.5 | 2 | 209.5±1.2 | 208.17 | 73.65±3.12 | 73.69 | 84.87±1.5 | 84.44 |

| 14 | 3 | 2.5 | 2 | 211.6±1.3 | 208.17 | 74.09±1.33 | 73.69 | 82.22±3.0 | 84.44 |

| 15 | 3 | 2.5 | 2 | 210.5±1.6 | 208.17 | 73.42±2.25 | 73.69 | 84.14±3.7 | 84.44 |

*A=Total lipid (%), B=Solid lipid: Liquid lipid, C=Surfactant (%); Y1=Particle size (nm), Y2=Entrapment efficiency, Y3=Drug release (for 24 h.), all the results are presented as mean±SD, n=3.

Table 3: Results of regression analysis for response in box-behnken experimental design

| Model | R² | Adjusted R² | Predicted R² | Std. Dev. | % CV | Remark |

| Response Y1 | ||||||

| Linear | 0.8365 | 0.7919 | 0.6521 | 16.11 | - | - |

| 2FI | 0.8447 | 0.7282 | 0.1826 | 18.41 | - | - |

| Quadratic | 0.9971 | 0.9919 | 0.9977 | 3.18 | 1.51 | Suggested |

| Response Y2 | ||||||

| Linear | 0.2640 | 0.0633 | -0.4011 | 6.95 | - | - |

| 2FI | 0.2908 | -0.2411 | -2.0409 | 8.00 | - | - |

| Quadratic | 0.9984 | 0.9955 | 0.9933 | 0.47 | 0.59 | Suggested |

| Response Y3 | ||||||

| Linear | 0.2754 | 0.0778 | -0.5359 | 9.26 | - | - |

| 2FI | 0.6049 | 0.3086 | -1.0375 | 8.02 | - | - |

| Quadratic | 0.9989 | 0.9970 | 0.9906 | 0.5321 | 0.650 | Suggested |

| Regression equation-Y1 = 208.07+41.37A+10.60B – 1.13C-0.300AB+1.95AC+5.65BC-18.88A2+15.42B2+8.52C2, Y2= 73.69+4.54A+1.61B-0.7662C-2.06AB+0.6925AC+0.32BC+3.17A2+11.09B2-2.10C2, Y3 = 84.44-6.42A-0.0763B+1.91C+2.30AB+4.61AC-8.99BC+7.24A2-4.55B2-7.54C2 |

Fig. 2: Linear correlation plots between actual and predicted values of: (A) Particle size; (B) Entrapment efficiency and (C) Percentage drug release (24 h)

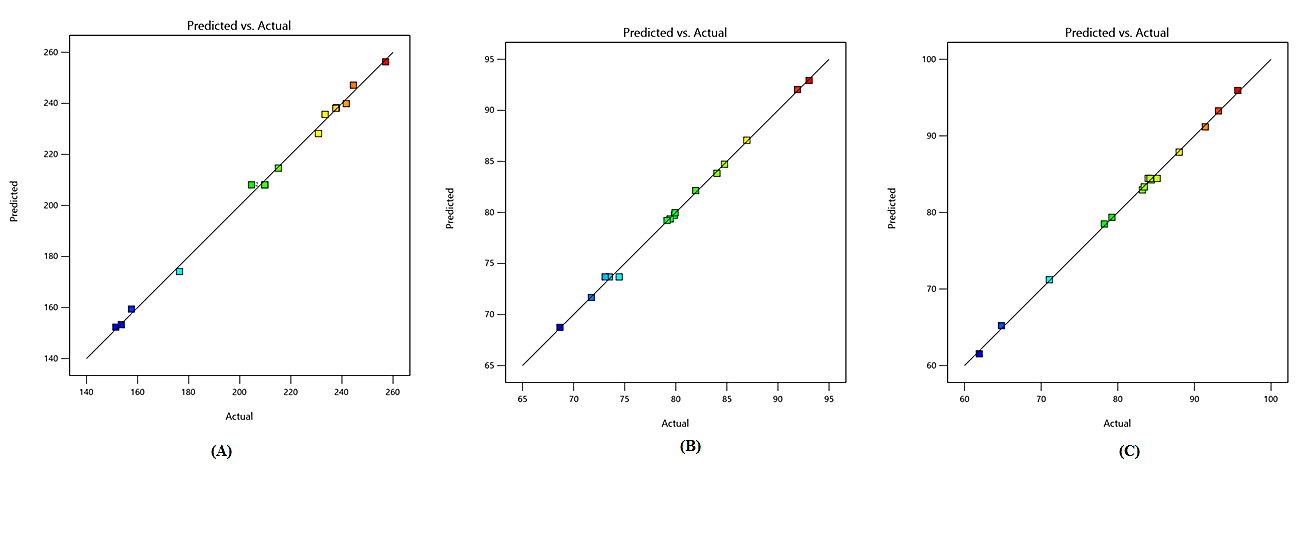

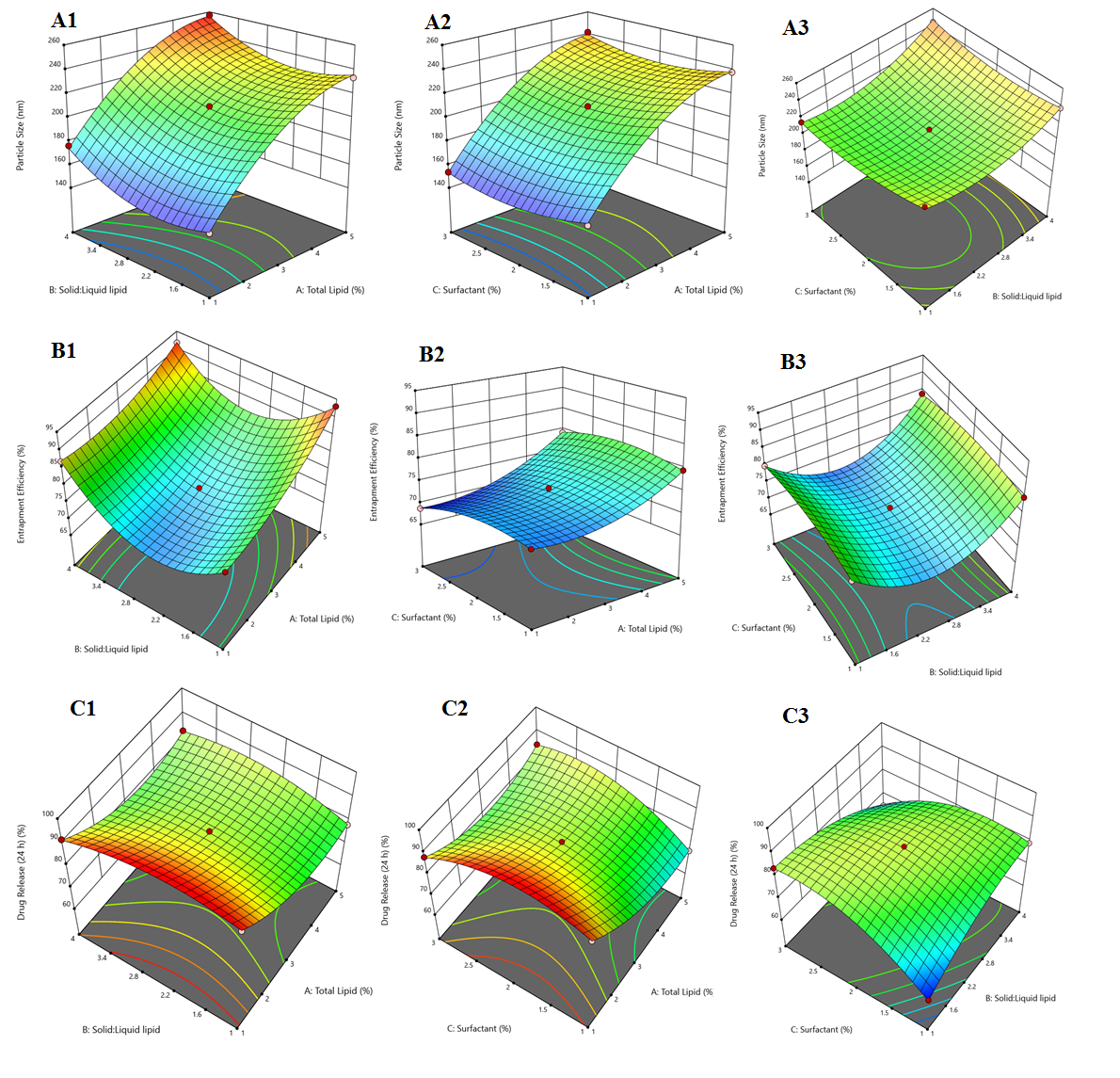

Effect of independent variables on particle size

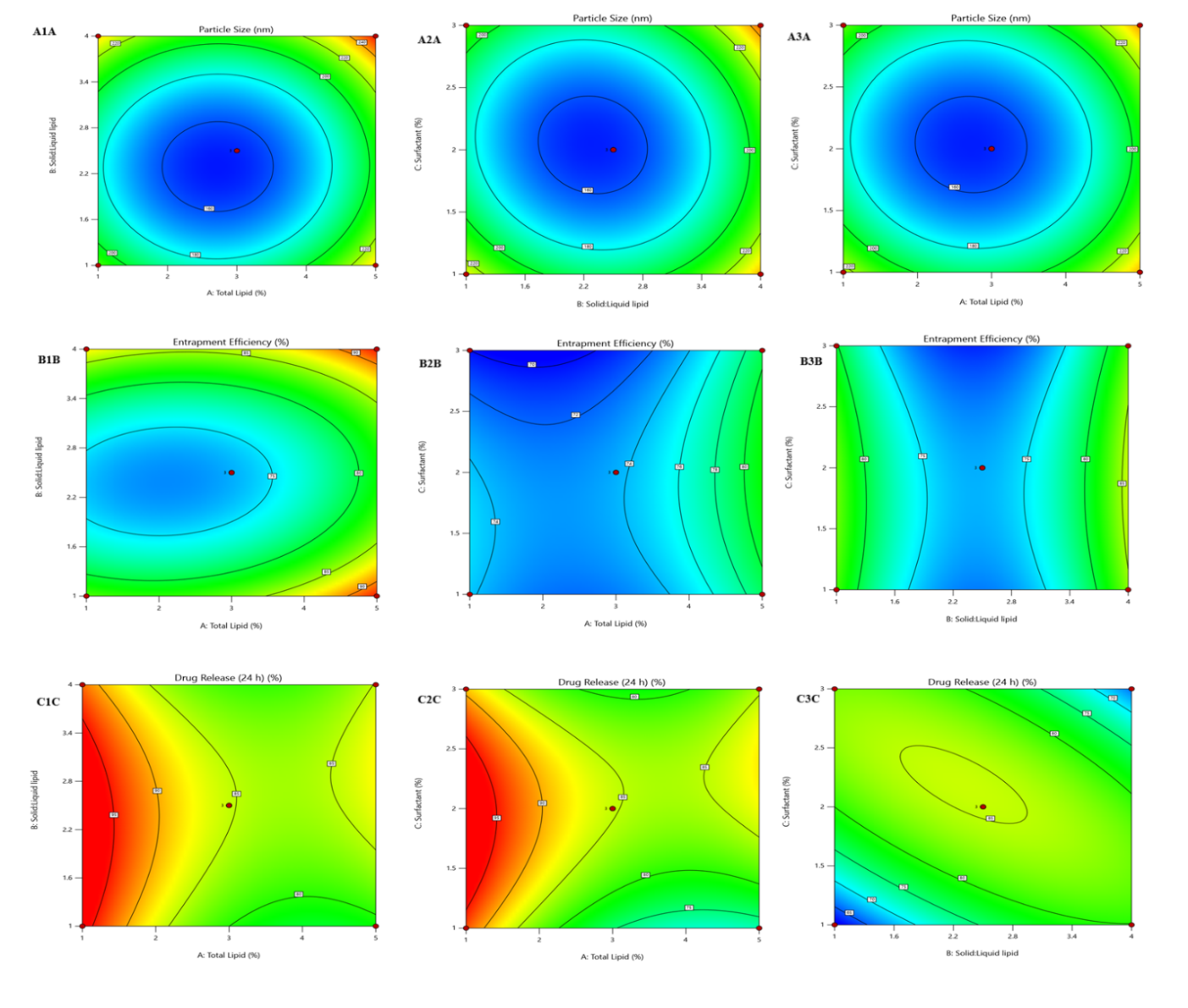

Since particle size in the nano range enhances interfacial interaction and hence improves drug absorption, particle diameter is the most important metric for characterizing NLCs [66, 67]. Table 3's equation unequivocally demonstrated that particle size (Y1) was positively impacted by both total lipid concentration (A) and solid: liquid lipid concentration (B), whereas surfactant concentration (C) had an inverse relationship with it. A three-dimensional (3D) surface plot analysis (fig. 3 (A1-3)) showed that a rise in the formulation's lipid proportion significantly increased the particle size and that the total lipid (%) concentration independently had a positive effect on it. This resulted in the conclusion that vehicle building, which created aggregates and ultimately increased size, caused particle size to rise as lipid concentrations varied from low to high. It was discovered that when surfactant concentration increased, particle size decreased, as evidenced by the negative individual influence of surfactant concentration on particle size. Further, in this study, the influence of lipid concentration, solid: liquid lipid ratio, and surfactant concentration were analyzed using contour plots. These contour plots provide a top-down view of 3D surface response plots, enabling a clearer understanding of the interaction between variables. To achieve the ideal nanoparticle size, a moderate lipid concentration and a carefully balanced surfactant-to-lipid ratio are required. As shown in the fig. 4 (A1A-3A), particle size was highest in regions with high total lipid (%). Higher solid lipid content increases viscosity and can lead to larger particle formation. In the fig. 4 (A3A) plot, areas with higher surfactant concentration (right side) show smaller particle sizes (deep blue region) [68].

Effect of independent variables on entrapment efficiency

Better EE minimizes drug loss during NLC manufacture, making it an important pharmacoeconomic factor to take into account [69]. A quadratic model was created by interpreting equation (Y2) in table 3. Equation (Y2) and fig. 3 (B1-3) showed that increasing total lipid (%) and lipid ratio resulted in an increase in EE. This can be due to the availability of additional matrix material to contain the medication. However, at some levels, increasing the lipid ratio resulted in a drop in EE. This might be related to the creation of an improper crystal structure. Individual surfactant percentages have a detrimental influence on EE. Up to a certain point, though, increasing surfactant concentration led to a loss in EE; beyond that, an increase in EE was seen. The contour plots (fig. 4 (B1B-3B)) visually represent these trends. The deep blue regions indicate the highest EE, which occurs when lipid concentration is optimized. However, in areas where lipid or surfactant concentrations deviate significantly from the optimal ratio, EE decreases (lighter regions), supporting the hypothesis of an unstable lipid structure affecting drug loading.

Effect of independent variables on drug release

According to equation (Y3) in table 3 and fig. 3 (C1-3), drug release from the NLC formulations was high on increasing surfactant concentration followed by total lipid (%) and solid: liquid lipid. Our results revealed that an increase in total lipid (%) decreased drug release while an increase in lipid ratio enhanced the drug release. This may be due to less migration of drug from the lipid matrix. The interaction between surfactant and lipid ratio also improved drug release. The contour plots (fig. 4 (C1C-3C)) further illustrate this relationship. Red regions represent areas with maximum drug release, primarily observed when surfactant concentration is high. Green and blue regions indicate lower drug release, seen at elevated total lipid concentrations due to strong drug entrapment. Additionally, the interaction between surfactant and lipid ratio plays a role in optimizing release characteristics.

Fig. 3: 3D response surface plot showing different effect on (A) Particle size; (B) Entrapment efficiency; and (C) Drug release (24 h)

Fig. 4: Contour plots showing different effect on (A) Particle size; (B) Entrapment efficiency; and (C) Drug release (24 h)

Optimization of final SMV-NLC formulation

Particle size, EE (%), and drug release (24 h) percentage were all constrained to "minimize," "maximize," and "maximize," respectively, in order to get the optimum possible formulation (table 1). The composition for the preparation of SMV-NLC was anticipated by the numerical optimization part of Box-Behnken design to be 2.9% total lipid, 2.61 solid: liquid lipid, and 2.85% surfactant based on the applicable restrictions. There were also predictions for the matching particle size, entrapment efficiency, and drug release (24 h) of 208.17 nm, 73.69%, and 84.44%, respectively. Particle size, EE, and drug release (24 h) were assessed in triple-independent duplicates to verify the efficacy of the optimization method and the predictive power of the resultant model. The actual and anticipated values for a number of factors are compared in table 4. The validity of this experimental design was supported by the observed responses, which agreed with the expected values. The next investigations provided characterizations of this enhanced formulation.

Table 4: Optimal levels of the independent variable, together with the predicted and observed responses at each level

| Optimized formula | Optimized level | Response | Observed±SD (n=3) | Predicted | Prediction error (%) |

| Total Lipid (%) | 2.9 | Y1 Particle Size (nm) | 209.8±1.8 | 208.17 | 3.67 |

| Solid: liquid lipid | 2.61 | Y2 Entrapment Efficiency (%) | 73.51±4.2 | 73.69 | 0.55 |

| Surfactant (%) | 2.85 | Y3 Drug Release (24 h) | 86.97±1.7 | 84.44 | 0.61 |

Characterization of optimized SMV-NLC formulation

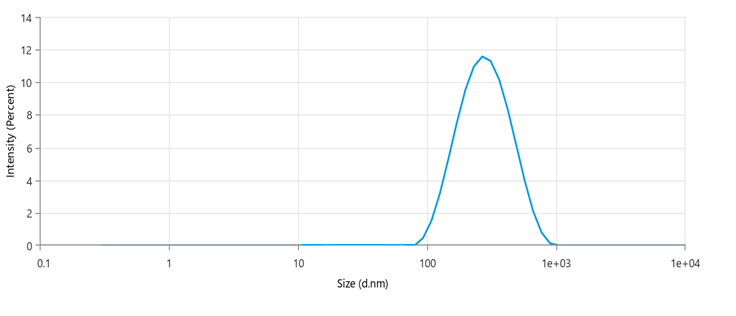

Particle size and PDI

The optimized formulation's mean particle size and PDI were determined to be 209.8 ±1.8 nm (fig. 5) and 0.319±0.14, respectively. Nanometer-sized particles (~200 nm) ensure deep lung penetration and efficient drug absorption in pulmonary drug delivery. Smaller particles can interact more effectively with lung epithelial cells, enhancing bioavailability [70]. The size that was achieved demonstrated the formulation's potential for penetrating the lung's cellular milieu. Low PDI of the optimized formulation confirms the need for dose consistency in pharmaceutical dosage forms and shows that the created NLC system was uniform in particle size. These findings are consistent with previously reported studies involving beclomethasone dipropionate-loaded NLCs, which showed equivalent particle size, low PDI value, and improved drug delivery to the lungs. The alignment of the present results with those from earlier research further strengthen the effectiveness of NLCs for pulmonary drug delivery [71].

Entrapment efficiency

Entrapment efficiency of optimized formulation was determined to be 73.51±4.2% (mean±SD, n=3), means a greater proportion of SMV was encapsulated within the lipid matrix. Higher entrapment of the SMV showed more drug will be available for sustained release characteristics. Non-entrapped drug will be available immediately, followed by sustained action from entrapped drugs. This combination of immediate and sustained release enhances drug efficacy [72].

Fig. 5: Particle size distribution graph of optimized SMV-NLC

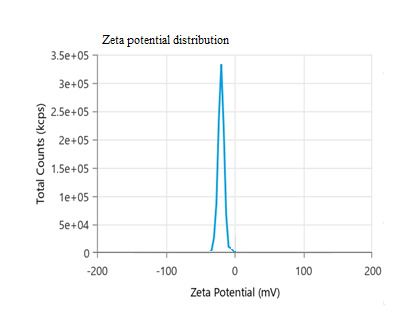

Zeta potential

Zeta potential is the build-up of net negative or positive charges surrounding individual particles. This helps in the electrostatic repulsion of individual particles, which prevents the nanoparticles form aggregation. The optimized formulation's zeta potential, as shown in fig. 6, was –20.35 mV, indicating that the formed SMV-NLC will remain stable over storage. The negative surface charge indicates substantial electrostatic repulsion in between the NLC particles to prevent particle agglomeration during storage. This not only protects the NLC particles but also enables homogenous dispersion of the formulation, which is essential for reproducible drug delivery and consistent therapeutic outcomes. Furthermore, the presence of a net negative charge on the nanoparticles aids in improving their dispersion within lung fluids, enhancing mucosal permeation and interaction with pulmonary epithelial cells. This results in improved drug penetration in the deep lung regions. A stable zeta potential also helps in maintaining the physicochemical integrity of the formulation over time, reducing degradation risks and extending shelf life [73].

Fig. 6: Zeta potential distribution graph of optimized SMV-NLC

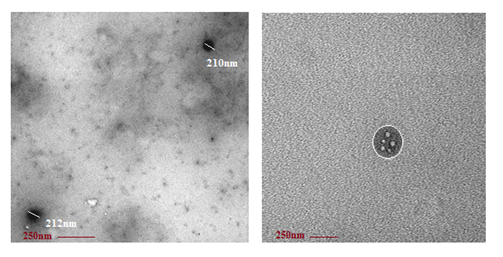

TEM analysis

Morphology is important as it determines the biological fate of NLC. Transmission electron microscopy examines outer and inner appearance of particles. Spherical structures are required for long circulation time and better extravasation from cardiovascular system. The optimized formulation's TEM picture (fig. 7) revealed that the SMV-NLC had smooth surfaces and a spherical shape. The size observed via TEM (210.6 nm±1.42, mean±SD (n=3)) closely matches the results from dynamic light scattering (DLS), validating the optimization process.

Fig. 7: TEM image of optimized SMV-NLC

FTIR analysis

To elucidate the molecular structure of the optimized SMV-NLC formulation and highlight the interactions between the medication and the excipient, FTIR research was carried out. As seen in fig. 8 and table 5, the FTIR spectra of SMV, GMS, physical mixture (SMV+GMS), and SMV-NLC were captured and analyzed. Typical bands were seen in the spectra of pure SMV and GMS, corresponding to the – C = O and – O = H stretch vibrations of the aliphatic chain at 1721 and 3123 cm−1, respectively [74]. Similar peaks were discovered in the SMV-GMS physical combination. The FTIR spectra of SMV-NLC revealed GMS peaks, proving that the SMV is trapped inside the NLC structures. The formulation was stable and compatible, ensuring effective drug delivery [75].

Table 5: FTIR spectra data of SMV, GMS and their combination

| Type of vibration | Reported frequency (cm-1) | SMV (cm-1) | GMS (cm-1) | Physical mixture (SMV+GMS) (cm-1) | SMV-NLC (cm-1) |

| 0 – H bonded (H – bonded) | 3500-3200 | 3198.82 | 3199.82 | 3196.30 | 3123 |

| -C = O (ketone) | 1725-1705 | 1713.61 | 1718.34 | 1717.43 | 1721 |

| Inference | Stable | Stable | Stable and Compatible | Stable and Compatible |

Fig. 8: FTIR spectra of pure SMV, GMS, physical mixture and SMV-NLC

In vitro drug release studies

An in vitro drug release characterization was conducted on SMV suspension and the optimized SMV-NLC formulation. Using the dialysis bag approach, an in vitro drug release experiment was conducted at 37±0.5 0C and human physiological pH 7.4. The dialysis bag acts as a barrier, allowing only drug molecules (not lipid carriers) to diffuse out. The total percentage of drug released from SMV-suspension and SMV-NLC over a 24 h period was determined to be 29.50±1.5% and 86.97±1.7%, respectively. The improved SMV-NLC formulation exhibited a biphasic profile with a 13.87% initial burst release and a 24 h sustained release (fig. 9). The burst release of SMV may have resulted from the breakdown of a liquid lipid close to the NLC boundary, whereas the persistent release of SVM was caused by its steady diffusion from the combined solid and liquid lipid matrix. The first burst release will aid in achieving the intended plasma concentration, while the continuous release helps to sustain the SMV dosage for an extended amount of time [76, 77]. After doing additional analysis on the in vitro release data using zero-order, first-order, Higuchi's and Korsmeyer’s models, the correlation coefficients (R2) that were discovered were 0.9351, 0.9930 and 0.9945, in that order. Higuchi's model provided the greatest match for the release, suggesting that the test sample adhered to matrix diffusion-based release kinetics. The Korsmeyer-Peppas model helped to determine the release mechanism using the n-value (release exponent) [78]. In the SMV-NLC formulation, the experimentally obtained n-value was determined to be 0.49. This suggested that the drug release was governed by a Fickian diffusion-controlled release mechanism. This release pattern is beneficial for controlled drug delivery, ensuring steady drug levels over time. This study confirmed that SMV-NLC was a more effective formulation than SMV-suspension for prolonged lung cancer therapy, as it allowed enhanced drug release, better absorption, and sustained therapeutic action.

Fig. 9: In vitro drug release profile of SMV-NLC. (Data is presented as mean±SD, n=3, where ***p<0.001)

In vitro anticancer cell line studies

The in vitro cytotoxic activity of optimized SMV-NLC was determined against A549 cancer cell lines (lung cancer) by incubating with different concentrations of the formulation for 24 h (fig. 10). In vitro cytotoxic activity results showed a direct relationship between SMV concentrations versus exposure time. After 24 h of exposure, SMV-NLC and SMV-suspension showed the IC50 of 11.34±0.12 and 30.26±0.14 µg/ml, respectively. The formulation's IC50 value is the concentration at which the number of viable cells is halved. SMV-NLC was found to be more cytotoxic (2.67 times) than SMV-suspension, suggesting that the nanostructured lipid carrier (NLC) system plays a crucial role in improving drug delivery and therapeutic efficiency. This may be due to more penetration efficiency and cellular uptake of SMV-NLC by A549 cell lines in comparison to SMV suspension. Nanoparticles accumulate more in tumor tissues due to the Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect. SMV-NLC remains inside cancer cells longer, leading to sustained drug release and prolonged cytotoxicity. SMV-NLC undergoes endocytosis, where cancer cells engulf the nano-formulation through clathrin-mediated or caveolae-mediated pathways [79]. This allows higher intracellular SMV concentration, leading to greater cytotoxic effects. A p-value of<0.01 suggests that the differences between SMV-NLC and SMV-suspension are statistically significant, confirming that the enhanced cytotoxicity of SMV-NLC is not due to chance. These properties make SMV-NLC a promising candidate for lung cancer therapy.

Fig. 10: MTT assay profile of SMV-NLC formulation and SMV-suspension. (Data is presented as mean±SD, n=3, where **p<0.01)

These results align with previous studies on NLC-based pulmonary systems of paclitaxel-loaded formulations, emphasizing the advantages of NLCs in enhancing lung deposition and therapeutic efficacy [45]. Supporting these results, a parallel study on celecoxib-loaded NLCs further confirmed the benefits of NLC-based pulmonary delivery systems. Collectively, these findings, in line with SMV-NLC results, highlight the potential of NLCs for controlled drug release and enhanced lung drug delivery [80].

DISCUSSION

As a potential lung cancer therapeutic platform, the current work suggests the development and optimization of SMV-loaded NLCs. A cutting-edge method for creating targeted drug delivery systems, especially for the treatment of cancer, is the formulation of SMV-loaded NLCs utilizing a Box-Behnken design. The main objective of employing nanostructured lipid carriers in cancer treatment is to increase the therapeutic efficacy, stability, and bioavailability of medications while reducing adverse effects. The benefits of both SLNs and conventional liposomes are uniquely combined in NLCs, a category of nanoparticles made up of a liquid lipid phase and a solid lipid core [81, 82]. Due to its ability to block certain pathways implicated in the growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis of cancer cells, SMV, a statin frequently used to treat excessive cholesterol, has also been investigated for possible anticancer effects. SMV's pharmacokinetics, cellular absorption, and sustained drug release are all intended to improve its therapeutic effects when added to NLCs [83, 84].

Pulmonary drug delivery aims to deliver drugs directly to the lungs, improving bioavailability, reducing systemic side effects, and enhancing therapeutic efficacy. GMS, OA, and Tween 80 selected for further formulation development was based on their highest solubility values among the tested excipients. High solubility ensures better drug loading capacity. The selected excipients i. e. GMS, OA and Tween 80, play a crucial role in formulating inhalable drug carriers such as lipid nanoparticles. GMS is a monoglyceride consisting of glycerol and one stearic acid molecule, whereas OA is a C18 monounsaturated fatty acid. GMS was used as a solid lipid matrix for controlled release, while OA enhances drug solubility and absorption. Their combination used in lipid-based drug delivery i. e. NLCs, improved solubility, stability, and drug absorption. Tween 80 was used a non-ionic surfactant. It helped in reducing surface tension, making drug particles more suitable for aerosolization and lung deposition. Drug-excipient compatibility studies ensure stability and effectiveness of the final pharmaceutical formulation. The drug-excipient compatibility study demonstrated that SMV and GMS are physically and chemically stable over the storage period. No significant changes in colour or texture over 4 w suggest physical compatibility between SMV and excipients. No major shifts in FTIR peaks indicate chemical compatibility of SMV with GMS. The study confirms that SMV and GMS can be used together without compromising drug stability, making them ideal for formulation development. The NLCs were successfully formed using the emulsification-probe sonication technique. This method ensures uniform particle size, high drug loading, and stability of the formulation [85]. The produced NLCs were suitable for enhanced drug delivery, improved bioavailability, and controlled release of SMV.

The Box-Behnken design was used to optimize a number of formulation parameters, including surfactant concentration (%), solid lipid: liquid lipid, and total lipid (%), which were considered independent variables in the context of SMV-loaded NLCs. The main dependent variables were considered to be the percentage of drug release, particle size, and entrapment efficiency. Lipids and surfactants directly influence drug entrapment, particle size, and drug release. Optimizing these factors ensures an ideal formulation with high efficacy and stability. The selected variables cover all key aspects of NLC formulation i. e., size, stability, and drug release. The box-behnken design efficiently analyzed these effects with minimal experiments. The quadratic model was statistically significant (p<0.0001), ensuring accurate prediction of optimal formulation parameters. The three independent and three dependent variables were chosen because they were critical to optimizing the NLC formulation. They ensured that the final product was efficient stable and provided sustained drug delivery, making it suitable for applications such as pulmonary drug delivery or other targeted therapies [86]. The observed responses closely matched the predicted values, proving the accuracy and reliability of the experimental design model. For better cellular uptake and increased penetration through biological barriers, smaller particles are frequently preferred in drug delivery systems. NLCs with a small particle size are more able to target tumor tissues in the treatment of lung cancer. Particles between 100–500 nm can easily reach the alveolar region, enabling sustained drug release. Nanoparticles (~200 nm) are efficiently absorbed by pulmonary epithelial cells via endocytosis, ensuring better drug absorption. Particles larger than 500 nm tend to be trapped in the upper respiratory tract, reducing therapeutic effectiveness. The small particle size (~210 nm) of the optimized formulation confirms effective lung targeting. The PDI value of 0.319 suggests that the particle size distribution is narrow, meaning uniform particle size in the formulation. A PDI<0.3 is considered ideal for nanosystems, indicating a well-dispersed and homogeneous formulation. Low PDI prevents particle aggregation, which could lead to inconsistent drug dosing. Entrapment efficiency of 73.51% ensured a balanced release profile (immediate+sustained action). The higher entrapment efficiency means more drug was retained within the NLC system, reducing premature drug degradation. Zeta potential of –20.35 mV ensures good nanoparticle stability and prevents aggregation. A negative zeta potential prevents aggregation by electrostatic repulsion between individual particles. This ensures uniform distribution of particles in suspension, which was crucial for consistent drug dosing. Stable NLCs helped retain drug entrapment efficiency and prevent premature drug release. Negatively charged NLCs can interact with pulmonary mucus and lung epithelial cells, improving bioavailability. TEM studies a particle's internal and external appearance. TEM can show if NLCs are uniformly shaped and sized since they are usually spherical or unevenly shaped. SMV-NLC nanoparticles were confirmed to be spherical and smooth. Spherical nanoparticles have a lower surface area-to-volume ratio, reducing interaction with clearance mechanisms. This allows longer retention in systemic circulation, improving drug delivery efficiency. A smooth surface prevents aggregation, ensuring a consistent release profile. FTIR of SMV-NLC was performed to confirm molecular interactions between SMV and excipients in the developed formulation. The SMV-NLC spectrum exhibited peaks similar to GMS, suggesting that SMV was encapsulated within the lipid structure rather than existing freely. No major shifts or disappearance of peaks were observed in the SMV-NLC formulation, confirming no chemical instability or degradation of SMV.

In vitro drug release studies were conducted to compare drug release from SMV-NLC and SMV-suspension. SMV-Suspension represents a free drug, likely leading to faster and uncontrolled release. The SMV-suspension had limited solubility, leading to incomplete drug release. SMV-NLC exhibited a biphasic release, ensuring both immediate and prolonged therapeutic effects. SMV-NLC showed significantly higher drug release (p<0.001) compared to SMV-suspension. Mathematical models helped to optimize the formulation by revealing the release mechanism. Higuchi’s model had the highest R² value (0.9945), confirming a diffusion-controlled release mechanism. The Korsmeyer-Peppas analysis further describes an effective release kinetics. Since the release exponent 𝑛 is approximately 0.49, it indicates Fickian diffusion, as n ≈ 0.5 suggests that the drug release follows a diffusion-controlled mechanism. This type of release is typical for hydrophilic matrix systems where diffusion is the rate-limiting step. Kinetic constant (k = 0.195, since log k =-0.71), represents the drug release rate. A higher 𝑘 would indicate faster drug release. The drug diffuses out of the polymeric matrix primarily due to a concentration gradient. Because NLCs were made for controlled or sustained release, the drug would be released over a longer time span, which would lower toxicity and enhance therapeutic effects. Studies on in vitro cytotoxicity are crucial for assessing a medication formulation's possible anticancer efficacy. These investigations aided in comparing SMV-loaded NLCs to free SMV and determining how well they inhibited the growth of cancer cells. The efficacy of SMV-loaded NLCs and free SMV was compared using the IC50 value. SMV-loaded NLCs had a lower IC50 than free SMV, indicating that the encapsulation increased the drug's efficacy, possibly as a result of greater sustained release, cellular absorption, and drug delivery [87]. The significantly lower IC50 value of SMV-NLC suggests that the nanoformulation have a smaller size and higher surface area, allowing better interaction with cancer cells. This leads to enhanced internalization through endocytosis, allowing more SMV to enter A549 lung cancer cells. The nanocarrier system significantly improved drug delivery efficiency, making it a promising formulation for lung cancer therapy. Future studies could explore in vivo models to confirm the therapeutic efficacy and safety of SMV-NLC [88].

CONCLUSION

Simvastatin-loaded NLCs were successfully formulated using emulsification and probe sonication method, optimized and evaluated. The opted methodology was found to be simple, reproducible, and may be used for large-scale production. Statistical Box-Behnken design was found to be statistically significant for optimization and selection of final formulation. Optimization research found that the quantity of lipid (solid and liquid lipid) and surfactant had a significant impact on particle size, entrapment efficiency, and drug release. The characterization parameters showed the suitability of the developed formulation for lung cancer management. The in vitro release profile of optimized SMV-NLC indicated SMV’s sustained release profile compared to pure SMV-suspension. In vitro cytotoxicity activity results showed that SMV-NLC had a significant dose-dependent cytotoxic impact on A549 cancer cells than SMV-suspension. The study successfully demonstrates that SMV-NLC have significant potential in lung cancer treatment. However, several future directions must be explored to fully realize its clinical applications. Further in vivo and clinical translational studies are needed to guarantee the therapeutic potential of SMV-NLC.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to acknowledge the Faculty of Pharmacy, Integral University, Lucknow for continuous support and supervision during all the phases of this research work (Manuscript Communication Number: IU/RandD/2024-MCN0002833).

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

All the authors contributed to the study conception and design of this research work. Methodology, writing and data analysis were performed by Nargis Ara and Abdul Hafeez. Shom Prakash Kushwaha and Archita Kapoor shared in methodology and data analysis of the manuscript. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Nargis Ara, and Abdul Hafeez reviewed and commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All the authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

Thandra KC, Barsouk A, Saginala K, Aluru JS, Barsouk A. Epidemiology of lung cancer. Contemp Oncol (Pozn). 2021 Feb;25(1):45-52. doi: 10.5114/wo.2021.103829, PMID 33911981.

Leiter A, Veluswamy RR, Wisnivesky JP. The global burden of lung cancer: current status and future trends. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2023 Sep;20(9):624-39. doi: 10.1038/s41571-023-00798-3, PMID 37479810.

Lahiri A, Maji A, Potdar PD, Singh N, Parikh P, Bisht B. Lung cancer immunotherapy: progress pitfalls and promises. Mol Cancer. 2023 Feb;22(1):40. doi: 10.1186/s12943-023-01740-y, PMID 36810079.

Howlader N, Forjaz G, Mooradian MJ, Meza R, Kong CY, Cronin KA. The effect of advances in lung cancer treatment on population mortality. N Engl J Med. 2020 Aug;383(7):640-9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1916623, PMID 32786189.

Nooreldeen R, Bach H. Current and future development in lung cancer diagnosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Aug;22(16):8661. doi: 10.3390/ijms22168661, PMID 34445366.

Vestergaard HH, Christensen MR, Lassen UN. A systematic review of targeted agents for non-small cell lung cancer. Acta Oncol. 2018 Feb;57(2):176-86. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2017.1404634, PMID 29172833.

Tang L, Li J, Zhao Q, Pan T, Zhong H, Wang W. Advanced and innovative nano-systems for anticancer targeted drug delivery. Pharmaceutics. 2021 Jul;13(8):1151. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13081151, PMID 34452113.

Din FU, Aman W, Ullah I, Qureshi OS, Mustapha O, Shafique S. Effective use of nanocarriers as drug delivery systems for the treatment of selected tumors. Int J Nanomedicine. 2017 Oct 5;12:7291-309. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S146315, PMID 29042776.

Edis Z, Wang J, Waqas MK, Ijaz M, Ijaz M. Nanocarriers mediated drug delivery systems for anticancer agents: an overview and perspectives. Int J Nanomedicine. 2021 Feb 17;16:1313-30. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S289443, PMID 33628022.

Sarkar S, Osama K, Jamal QM, Kamal MA, Sayeed U, Khan MK. Advances and implications in nanotechnology for lung cancer management. Curr Drug Metab. 2017 Jan;18(1):30-8. doi: 10.2174/1389200218666161114142646, PMID 27842486.

Alshawwa SZ, Kassem AA, Farid RM, Mostafa SK, Labib GS. Nanocarrier drug delivery systems: characterization limitations future perspectives and implementation of artificial intelligence. Pharmaceutics. 2022 Apr;14(4):883. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14040883, PMID 35456717.

Singh N, Kushwaha P, Gupta A, Ved A, Swarup S. Development and evaluation of sesamol loaded self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery system for breast cancer. Pharmacogn Mag. 2022 Mar;18(77):94-102. doi: 10.4103/pm.pm_248_21.

Ansari MT, Ramlan TA, Jamaluddin NN, Zamri N, Salfi R, Khan A. Lipid-based nanocarriers for cancer and tumor treatment. Curr Pharm Des. 2020 Sep;26(34):4272-6. doi: 10.2174/1381612826666200720235752, PMID 32693760.

Fatima A, Naseem N, Haider MF, Rahman MA, Mall J, Saifi MS. A comprehensive review on nanocarriers as a targeted delivery system for the treatment of breast cancer. Intell Pharm. 2024;2(3):415-26. doi: 10.1016/j.ipha.2024.04.001.

S Pragati, S Kuldeep, S Ashok, M Satheesh. Solid lipid nanoparticles: a promising drug delivery technology. PCI- Approved-IJPSN. 2009;2(2):509-16. doi: 10.37285/ijpsn.2009.2.2.3.

Kim SJ, Puranik N, Yadav D, Jin JO, Lee PC. Lipid nanocarrier based drug delivery systems: therapeutic advances in the treatment of lung cancer. Int J Nanomedicine. 2023 Dec;18:2659-76. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S406415, PMID 37223276.

Kim CH, Lee SG, Kang MJ, Lee S, Choi YW. Surface modification of lipid-based nanocarriers for cancer cell-specific drug targeting. J Pharm Investig. 2017 May;47(3):203-27. doi: 10.1007/s40005-017-0329-5.

Viegas C, Patricio AB, Prata JM, Nadhman A, Chintamaneni PK, Fonte P. Solid lipid nanoparticles vs. nanostructured lipid carriers: a comparative review. Pharmaceutics. 2023 May;15(6):1593. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics15061593, PMID 37376042.

Sakellari GI, Zafeiri I, Batchelor H, Spyropoulos F. Formulation design production and characterisation of solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) and nanostructured lipid carriers (NLC) for the encapsulation of a model hydrophobic active. Food Hydrocoll Health. 2021 Aug 31;1:18. doi: 10.1016/j.fhfh.2021.100024, PMID 35028634.

Shaif M, Kushwaha P, Usmani S, Pandey S. Exploring the potential of nanocarriers in antipsoriatic therapeutics. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022 Oct;33(7):2919-30. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2022.2089616, PMID 35729857.

Otarola JJ, Alejandra Luna M, Mariano Correa N, Molina PG. Noscapine-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers as a potential topical delivery to bovine mastitis treatment. Chemistry Select. 2020 May;5(20):5922-7. doi: 10.1002/slct.202001138.

Selvamuthukumar S, Velmurugan R. Nanostructured lipid carriers: a potential drug carrier for cancer chemotherapy. Lipids Health Dis. 2012 Dec;11:159. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-11-159, PMID 23167765.

Borawake PD, Arumugam KA, Shinde JV. Formulation of solid dispersions for enhancement of solubility and dissolution rate of simvastatin. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2021 Jul;13(7):94-100. doi: 10.22159/ijpps.2021v13i7.41205.

Boccuzzi SJ, Bocanegra TS, Walker JF, Shapiro DR, Keegan ME. Long-term safety and efficacy profile of simvastatin. Am J Cardiol. 1991 Nov;68(11):1127-31. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(91)90182-K, PMID 1951069.

Pedersen TR, Tobert JA. Simvastatin: a review. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2004 Dec;5(12):2583-96. doi: 10.1517/14656566.5.12.2583, PMID 15571475.

Duarte JA, De Barros AL, Leite EA. The potential use of simvastatin for cancer treatment: a review. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021 Sep;141:111858. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111858, PMID 34323700.

Turabi KS, Deshmukh A, Paul S, Swami D, Siddiqui S, Kumar U. Drug repurposing an emerging strategy in cancer therapeutics. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2022 Oct;395(10):1139-58. doi: 10.1007/s00210-022-02263-x, PMID 35695911.

Tripathi S, Gupta E, Galande S. Statins as anti‐tumor agents: a paradigm for repurposed drugs. Cancer Rep (Hoboken). 2024 May;7(5):e2078. doi: 10.1002/cnr2.2078, PMID 38711272.

Climent E, Benaiges D, Pedro Botet J. Hydrophilic or lipophilic statins? Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021 May;8:687585. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2021.687585, PMID 34095267.

Brito Raj S, Chandrasekhar KB, Reddy KB. Formulation in vitro and in vivo pharmacokinetic evaluation of simvastatin nanostructured lipid carrier loaded transdermal drug delivery system. Futur J Pharm Sci. 2019 Dec;5(1):1-14. doi: 10.1186/s43094-019-0008-7.

Devi A, Kumar M, Kumar M, Mandal UK. Review on disease dose destination and delivery aspects of simvastatin. Drug Deliv Lett. 2020 Dec;10(4):278-87. doi: 10.2174/2210303110999200730215812.

Ghasemiyeh P, Mohammadi Samani S. Solid lipid nanoparticles and nanostructured lipid carriers as novel drug delivery systems: applications advantages and disadvantages. Res Pharm Sci. 2018 Aug;13(4):288-303. doi: 10.4103/1735-5362.235156, PMID 30065762.

Sharma A, Baldi A. Nanostructured lipid carriers: a review. J Dev Drugs. 2018 Aug;7(2):1-15. doi: 10.4172/2329-6631.1000191.

Yousry C, Goyal M, Gupta V. Excipients for novel inhaled dosage forms: an overview. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2024 Feb;25(2):36. doi: 10.1208/s12249-024-02741-w, PMID 38356031.

Bandgar SA, Jadhav NR. Validated UV spectrophotometric method for estimation of simvastatin in bulk and pharmaceutical formulation. Res J Pharm Technol. 2019 Feb;12(12):5745-8. doi: 10.5958/0974-360X.2019.00994.6.

Negi LM, Jaggi M, Talegaonkar S. Development of protocol for screening the formulation components and the assessment of common quality problems of nano-structured lipid carriers. Int J Pharm. 2014 Jan;461(1-2):403-10. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.12.006, PMID 24345574.

Kovacevic AB, Muller RH, Keck CM. Formulation development of lipid nanoparticles: improved lipid screening and development of tacrolimus loaded nanostructured lipid carriers (NLC). Int J Pharm. 2020 Feb 25;576:118918. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2019.118918, PMID 31870954.

Saatkamp RH, Dos Santos BM, Sanches MP, Conte J, Rauber GS, Caon T. Drug excipient compatibility studies in formulation development: a case study with benznidazole and monoglycerides. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2023 Oct;235:115634. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2023.115634, PMID 37595356.

Bal T, Murthy PN. Studies of drug polymer interactions of simvastatin with various polymers. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2012 Feb;3(2):561-3. doi: 10.13040/IJPSR.0975-8232.3(2).561-63.

Jaiswal P, Gidwani B, Vyas A. Nanostructured lipid carriers and their current application in targeted drug delivery. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2016 Jan;44(1):27-40. doi: 10.3109/21691401.2014.909822, PMID 24813223.

Gomaa E, Fathi HA, Eissa NG, Elsabahy M. Methods for preparation of nanostructured lipid carriers. Methods. 2022 Mar;199:3-8. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2021.05.003, PMID 33992771.

Zhang W, Li X, Ye T, Chen F, Sun X, Kong J. Design characterization and in vitro cellular inhibition and uptake of optimized genistein loaded NLC for the prevention of posterior capsular opacification using response surface methodology. Int J Pharm. 2013 Sep;454(1):354-66. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.07.032, PMID 23876384.

Jafar GA, Salsabilla SY, Santoso RA. Development and characterization of compritol ato® base in nanostructured lipid carriers formulation with the probe sonication method. Int J App Pharm. 2022 Sep;14(4):64-6. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2022.v14s4.PP04.

Javed S, Mangla B, Almoshari Y, Sultan MH, Ahsan W. Nanostructured lipid carrier system: a compendium of their formulation development approaches optimization strategies by quality by design and recent applications in drug delivery. Nanotechnol Rev. 2022 Apr;11(1):1744-77. doi: 10.1515/ntrev-2022-0109.

Kaur P, Garg T, Rath G, Murthy RS, Goyal AK. Development optimization and evaluation of surfactant-based pulmonary nanolipid carrier system of paclitaxel for the management of drug resistance lung cancer using box-behnken design. Drug Deliv. 2016 Jul;23(6):1912-25. doi: 10.3109/10717544.2014.993486, PMID 25544602.

Agrawal M, Saraf S, Pradhan M, Patel RJ, Singhvi G, Ajazuddin. Design and optimization of curcumin-loaded nano lipid carrier system using box-behnken design. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021 Sep;141:111919. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111919, PMID 34328108.

Sherif AY, Harisa GI, Shahba AA, Alanazi FK, Qamar W. Optimization of gefitinib loaded nanostructured lipid carrier as a biomedical tool in the treatment of metastatic lung cancer. Molecules. 2023 Jan;28(1):448. doi: 10.3390/molecules28010448, PMID 36615641.

Alhalmi A, Amin S, Beg S, Al Salahi R, Mir SR, Kohli K. Formulation and optimization of naringin loaded nanostructured lipid carriers using box-behnken based design: in vitro and ex vivo evaluation. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2022 Aug;74:103590. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2022.103590.

Soni K, Rizwanullah MD, Kohli K. Development and optimization of sulforaphane loaded nanostructured lipid carriers by the box-behnken design for improved oral efficacy against cancer: in vitro, ex vivo and in vivo assessments. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2018 Oct;46 Suppl 1:15-31. doi: 10.1080/21691401.2017.1408124, PMID 29183147.

Magalhaes J, L Chaves L, C Vieira A, G Santos S, Pinheiro M, Reis S. Optimization of rifapentine loaded lipid nanoparticles using a quality by design strategy. Pharmaceutics. 2020 Jan;12(1):75. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics12010075, PMID 31963468.

Rahamathulla M, HG, Veerapu G, Hani U, Alhamhoom Y, Alqahtani A. Characterization optimization in vitro and in vivo evaluation of simvastatin proliposomes as a drug delivery. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2020;21(4):129. doi: 10.1208/s12249-020-01666-4, PMID 32405982.

Mainuddin KA, Kumar A, Ratnesh RK, Singh J, Dumoga S, Sharma N. Physical characterization and bioavailability assessment of 5-fluorouracil based nanostructured lipid carrier (NLC): in vitro drug release hemolysis and permeability modulation. Med Oncol. 2024 Mar;41(5):95. doi: 10.1007/s12032-024-02319-3, PMID 38526657.

Jahan S, Aqil M, Ahad A, Imam SS, Waheed A, Qadir A. Nanostructured lipid carrier for transdermal gliclazide delivery: development and optimization by box-behnken design. Inorg Nano Met Chem. 2024;54(5):474-87. doi: 10.1080/24701556.2021.2025097.

Midekessa G, Godakumara K, Ord J, Viil J, Lattekivi F, Dissanayake K. Zeta potential of extracellular vesicles: toward understanding the attributes that determine colloidal stability. ACS Omega. 2020 Jun;5(27):16701-10. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.0c01582, PMID 32685837.

Guimaraes D, Cavaco Paulo A, Nogueira E. Design of liposomes as drug delivery system for therapeutic applications. Int J Pharm. 2021 May;601:120571. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.120571, PMID 33812967.

Rawal S, Bora V, Patel B, Patel M. Surface-engineered nanostructured lipid carrier systems for synergistic combination oncotherapy of non-small cell lung cancer. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2021 Oct;11(5):2030-51. doi: 10.1007/s13346-020-00866-6, PMID 33215254.

Orgul D, Eroglu H, Tiryaki M, Pınarlı FA, Hekimoglu S. In vivo evaluation of tissue scaffolds containing simvastatin-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers and mesenchymal stem cells in diabetic wound healing. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2021 Feb;61:102140. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2020.102140.

Huguet Casquero A, Moreno Sastre M, Lopez Mendez TB, Gainza E, Pedraz JL. Encapsulation of oleuropein in nanostructured lipid carriers: biocompatibility and antioxidant efficacy in lung epithelial cells. Pharmaceutics. 2020 May;12(5):429. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics12050429, PMID 32384817.

Wu IY, Bala S, Skalko Basnet N, Di Cagno MP. Interpreting non-linear drug diffusion data: utilizing korsmeyer peppas model to study drug release from liposomes. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2019 Oct;138:105026. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2019.105026, PMID 31374254.

Zhang Y, Huo M, Zhou J, Zou A, Li W, Yao C. DDSolver: an add-in program for modeling and comparison of drug dissolution profiles. AAPS J. 2010 Sep;12(3):263-71. doi: 10.1208/s12248-010-9185-1, PMID 20373062.

Van Meerloo J, Kaspers GJ, Cloos J. Cell sensitivity assays: the MTT assay. Methods Mol Biol. 2011 Mar;731:237-45. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-080-5_20, PMID 21516412.

Tihauan BM, Berca LM, Adascalului M, Sanmartin AM, Nica S, Cimponeriu D. Experimental in vitro cytotoxicity evaluation of plant bioactive compounds and phytoagents. Rom Biotechnol Lett. 2020 Feb;25(4):1832-42. doi: 10.25083/rbl/25.4/1832.1842.

Shete H, Patravale V. Long chain lipid-based tamoxifen NLC. Part I: preformulation studies formulation development and physicochemical characterization. Int J Pharm. 2013 Sep;454(1):573-83. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.03.034, PMID 23535345.

Doktorovova S, Shegokar R, Souto EB. Role of excipients in formulation development and biocompatibility of lipid nanoparticles (SLNs/NLCs). In: Nanostructures for novel therapy. Elsevier; 2017. p. 811-43. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-323-46142-9.00030-X.

Munir A, Ahmad M, Malik MZ, Minhas MU. Analysis of simvastatin using a simple and fast high-performance liquid chromatography ultraviolet method: development validation and application in solubility studies. Trop J Pharm Res. 2014 Feb;13(1):135-9. doi: 10.4314/tjpr.v13i1.19.

Khan FM, Ahmad M, Idrees HA. Simvastatin nicotinamide co-crystals: formation pharmaceutical characterization and in vivo profile. Drug Des Dev Ther. 2020 Oct 19;14:4303-13. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S270742, PMID 33116417.

Shah VA, Patel JK. Optmization and characterization of doxorubicin-loaded solid lipid nanosuspension for nose to brain delivery using design expert software. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2021 Feb;13(5):45-57. doi: 10.22159/ijpps.2021v13i5.41137.

Madupoju B, Areti A, Malothu N, Chamakuri K. Optimization characterization and in vivo hepatoprotective evaluation of nac-loaded nanoparticles using QbdAndImagej® software. Int J App Pharm. 2025 Jan;17(2):339-51. doi: 10.22159/IJAP.2025V17I2.52384.

Choi KO, Choe J, Suh S, Ko S. Positively charged nanostructured lipid carriers and their effect on the dissolution of poorly soluble drugs. Molecules. 2016 May;21(5):672. doi: 10.3390/molecules21050672, PMID 27213324.

Garbuzenko OB, Mainelis G, Taratula O, Minko T. Inhalation treatment of lung cancer: the influence of composition size and shape of nanocarriers on their lung accumulation and retention. Cancer Biol Med. 2014 Mar;11(1):44-55. doi: 10.7497/j.issn.2095-3941.2014.01.004, PMID 24738038.

Khan I, Hussein S, Houacine C, Khan Sadozai SK, Islam Y, Bnyan R. Fabrication characterization and optimization of nanostructured lipid carrier formulations using beclomethasone dipropionate for pulmonary drug delivery via medical nebulizers. Int J Pharm. 2021 Apr;598:120376. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.120376, PMID 33617949.

Zeng XM, Martin GP, Marriott C. The controlled delivery of drugs to the lung. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 1995 Oct;124(2):149-64. doi: 10.1016/0378-5173(95)00104-Q.

Chishti N, Jagwani S, Dhamecha D, Jalalpure S, Dehghan MH. Preparation optimization and in vivo evaluation of nanoparticle based formulation for pulmonary delivery of anticancer drug. Medicina (Kaunas). 2019 Jun;55(6):294. doi: 10.3390/medicina55060294, PMID 31226865.

Baba H, Bunu SJ. Spectroscopic and molecular docking analysis of phytoconstituent isolated from solenostemon monostachyus as potential cyclooxygenase enzymes inhibitor. Int J Chem Res. 2025 Jan;9(1):1-6. doi: 10.22159/ijcr.2025v9i1.241.

Brito Raj S, Chandrasekhar KB, Reddy KB. Formulation in vitro and in vivo pharmacokinetic evaluation of simvastatin nanostructured lipid carrier loaded transdermal drug delivery system. Futur J Pharm Sci. 2019 Dec;5(1):1-14. doi: 10.1186/s43094-019-0008-7.

Brito Raj S, Chandrasekhar KB, Reddy KB. Formulation in vitro and in vivo pharmacokinetic evaluation of simvastatin nanostructured lipid carrier loaded transdermal drug delivery system. Futur J Pharm Sci. 2019 Dec;5(1):1-14. doi: 10.1186/s43094-019-0008-7.

Kumbhar PS, Manjappa AS, Shah RR, Nadaf SJ, Disouza JI. Nanostructured lipid carrier based gel for repurposing simvastatin in localized treatment of breast cancer: formulation design development and in vitro and in vivo characterization. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2023 Apr;24(5):106. doi: 10.1208/s12249-023-02565-0, PMID 37085596.

Alam M, Ahmed S, Moon G, Aqil M, Sultana Y. Chemical engineering of a lipid nano-scaffold for the solubility enhancement of an antihyperlipidaemic drug simvastatin; preparation optimization physicochemical characterization and pharmacodynamic study. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2017;46(8):1-12. doi: 10.1080/21691401.2017.1396223.