Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 5, 2025, 481-487Original Article

COMPUTATIONAL INVESTIGATION OF THE INHIBITION OF CHK1 AND WEE1 PROTEINS BY CHEMICAL CONSTITUENTS OF AMARANTHUS GANGETICUS

ADE S. ROHANI1, HENNY S. WAHYUNI2*, EFFENDY DL PUTRA2, NAZLINIWATY3, CELINE AULETTA2, TIARA RASYIDA2

1Department of Pharmaceutical Pharmacology, Faculty of Pharmacy, Medan, Universitas Sumatera Utara, Indonesia. 2Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, Faculty of Pharmacy, Medan, Universitas Sumatera Utara, Indonesia. 3Department of Pharmaceutical Technology, Faculty of Pharmacy, Medan, Universitas Sumatera Utara, Indonesia

*Corresponding author: Henny S. Wahyuni; *Email: henny@usu.ac.id

Received: 10 Feb 2025, Revised and Accepted: 05 Jun 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: This study aimed to explore an alternative compound capable of inhibiting CHK1 (Checkpoint Kinase 1) and WEEl proteins in breast cancer using natural compounds derived from red spinach (Amaranthus gangeticus).

Methods: The experiment used SMILES and 3D structure of red spinach, PASS Online for biology activity, Lipinski's rule of five for physicochemical properties predictions, as well as validation, and molecular docking of active compounds.

Results: The results showed that CHK1 and WEE1 docking validation had RMSD values of 1.5 Å and 0.634 Å, respectively. The compounds 3,4,5-Trihydroxybenzoic acid, 3,5-Dimethoxy-4-hydroxybenzoic acid, 2,3,7,8-Tetrahydroxy-chromeno[5,4,3-cde]chromene-5,10-dione, 3-(3,4-Dihydroxycinnamoyl)quinic acid, 3-Methoxy-4-hydroxycinnamic acid, 4-Hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxycinnamic acid, 3-Phenylacrylic acid, 4′,5,7-Trihydroxyflavone, Catechin, and Quercetin exhibited favourable binding affinity values, molecular interactions, and predicted inhibitory effects against CHK1 by interacting with key residues LEU A 15, VAL A 23, and LEU A 137, and against WEE1 through interactions with GLU A 377, ILE A 305, VAL A 313, ALA A 326, and PHE A 433. While these findings highlight promising inhibitory potential, further in vitro and in vivo validation is needed to confirm the computational findings.

Conclusion: This study found that the active compounds of red spinach could be used as a functional inhibitor of CHK1 and WEE1.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Red spinach (Amaranthus gangeticus), CHK1, WEE1, In silico

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i5.53996 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Cancer is an illness resulting from the abnormal proliferation of cells in the tissues of the body due to mutations of genetic. It is a global health problem, and a leading cause of death worldwide, with breast cancer being the second most prevalent reason of death among women. In Indonesia, statistics provided by the Global Cancer Observatory showed that there were 65,858 (16.6%) new cases of breast cancer out of 396,914 with a total of 22,430 deaths (9.6%) in 2020 [1, 2].

Chemical drugs, such as doxorubicin, often cause resistance, specifically in T47D breast cancer cells, while long-term use leads to toxicity and side effects such as hair loss and low blood pressure. Consequently, natural ingredients are preferred due of their improved safety profile [3, 4].

Breast cancer arises from genetic mutations leading to uncontrolled cell proliferation, and it remains one of the leading causes of cancer-related death in women [5]. The associated risk factors include age at menarche, obesity, duration of using hormonal contraception, smoking, and history of breastfeeding [6]. High breast cancer incidence is partly attributed to limited awareness of risk factors and the importance of early examination [7].

A previous study showed that low vegetable consumption was associated with heightened cancer susceptibility [8]. Based on an in vitro investigation, water and ethanol extract from red spinach (Amaranthus gangeticus) had cytotoxic activity against several lines of cells derived from cancerous tissues [9]. Production demand for the plant reached 148,288 tons. The antioxidant content of red spinach is theorized to have anticancer (anti-mitotic) properties. Notably, kaempferol, a flavonoid present in red spinach, has been reported to suppress proliferation and induce cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, and DNA damage in breast cancer cells. However, direct inhibition of WEE1 or CHK1 kinases by kaempferol has not been demonstrated. Further research is needed to clarify its precise molecular targets and compare its efficacy with clinically used CHK1/WEE1 inhibitors [10-12].

CHK1 (Checkpoint Kinase 1) is a protein kinase that functions as a central genome surveillance system for replication and responding to DNA damage. The activation occurs when there is DNA damage, helping maintain genome stability. CHK1 inhibition slows the S phase by arresting cell replication, preventing entry into the M phase. It also activates WEE1 and MYT1, to preserve CDK1 in a dormant condition. In addition, CHK1plays an important role for controlling cycle of cell [13].

WEE1 is an essential component in G2/M checkpoint, regulating the replication and maintenance of DNA. The inhibition blocks CDK1 activity by initiating phosphorylation at Thr14 and Tyr15, activating the G2-M phase. DNA damage will cause WEE1 kinase to inactivate CDK1/2, thereby preventing cells from continuing mitosis by maintaining G2 arrest [13].

CHK1 and WEE1 inhibition synergistically affects cycle of cell’s stability, triggering damage of DNA and promoting progressing death from cell rapidly. The inhibition of WEE1 makes the replication fork in cancer cells stop and break down. Co-inhibition of these two proteins blocks the ability of cells to repair damage, thereby inducing apoptosis or cell death [14].

Several CHK1 and WEE1 inhibitors are currently available on the market, including Adavosertib (AZD1775), a selective WEE1 inhibitor, and Prexasertib, a CHK1 inhibitor. Adavosertib has demonstrated potential in various clinical trials, often in combination with DNA-damaging agents such as chemotherapy. However, it is associated with significant side effects, including hematological toxicity, gastrointestinal distress, and fatigue [15, 16]. Similarly, Prexasertib induces DNA damage and apoptosis but can lead to severe myelosuppression, limiting its clinical application. Given these limitations, the search for novel, less toxic inhibitors remain crucial, highlighting the potential of natural compounds such as kaempferol as alternative candidates for CHK1/WEE1 inhibition [17, 18].

Computational method is used for predicting interactions between two molecules, producing a binding model that can predict the mechanism of action for active compounds [19]. Although in silico analysis is crucial, further in vitro stages on red spinach extract are necessary to determine the activity as an anticancer candidate by inhibiting CHK1 and WEE1 proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tools

Hardware: Computer with specification of Windows 11 Pro 64-bit (Build 22621.608), 12th Gen Intel® Core™ i7-12700H CPU @2.70 GHz (20CPUs), 16.0 GB memory.

Software: Molecular docking was conducted using AutoDock Tools 1.5.7 and AutoDock Vina 1.1.2 [20]. Visualization of docking interactions was performed using Biovia Discovery Studio Visualizer 4.5 [21] and PyMOL 2.5 [22]. Physicochemical properties were assessed using Lipinski’s rule of five via SCFBio-IITD (http://www.scfbio-iitd.res.in) [23]. Biological activity prediction was conducted using PASS Online via (http://way2drug.com/PassOnline/) [24]. Protein structures were obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB)via (www.rcsb.org) [25]. Chemical compound data were retrieved from PubChem via (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) [26].

Bioactive compounds of red spinach (Amaranthus gangeticus)

Based on several studies conducted by Kalanjati et al. (2014), Sarker and Ercisli (2022), as well as Sarker and Oba (2020, 2021), Amaranthus gangeticus has been identified as a rich source of bioactive compounds with significant nutritional and antioxidant properties. The active compounds included 3,4,5-Trihydroxybenzoic acid, 4-Hydroxy-3-methoxybenzoic acid, 3,5-Dimethoxy-4-hydroxybenzoic acid, 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid, 2-Hydroxybenzoic acid, 2,3,7,8-Tetrahydroxychromeno[5,4,3cde]chromene-5,10-dione, 3,4-Dihydroxybenzoic acid, 2,4-Dihydroxybenzoic acid, 2,5-Dihydroxybenzoic acid, 3,4-Dihydroxy-trans-cinnamate, 3-(3,4-Dihydroxycinnamoyl)quinic acid, 4-Hydroxycinnamic acid, 3-Methoxy-4-hydroxy cinnamic acid, 3-Hydroxycinnamic acid, 4-Hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxy cinnamic acid, 3-Phenylacrylic acid, Quercetin-3-O-glucoside, Quercetin-3-O-galactoside, Quercetin-3-O-rutinoside, Myricetin-3-O-rutinoside, 4′,5,7-Trihydroxyflavone, Kaempferol-3-O-rutinoside, Neoxanthin, Violaxanthin, Lutein, Zeaxanthin, β-carotene, Ascorbic acid, folic acid, Catechin, Narigenin, Quercetin, Betanin, Isobetanin, and Betalains [27-30].

Biology activity prediction using pass online (prediction of activity spectra substances)

Biological activity predictions were carried out using the PASS Online web server (http://way2drug.com/PassOnline/), which predicts pharmacological properties based on structure-activity relationships (SAR) using machine learning and Bayesian models [24]. SMILES representations of the compounds were obtained from PubChem before input into PASS Online [26].

Physiochemistry prediction (Lipinski’s rule of five)

Physiochemistry predictions were analyzed using Lipinski’s Rule of Five [23], implemented via the SCFBio-IITD web server (http://www.scfbio-iitd.res.in). The 3D molecular structures were obtained from PubChem, and analysis included molecular weight, hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, and logP values [26].

Proteins, native ligand, ligand preparation

Proteins were obtained from protein data bank (www.rcsb.org) [25], using CHK1 (2YEX resolution 1.30 Å) and WEE1 (1X8B resolution 1.81 Å). Proteins preparations were done using AutodockTools1.5.7 [20], with a 3D structure of CHK1 (2YEX) and WEE1 (1X8B) by removing water, polarizing the proteins, and adding Kollman charges. Proteins preparation using AutodockTools 1.5.7 determined the grid box in the area known to be the active site of the protein. The grid box was determined by setting the location of the box parameters and selecting the size using spacing (angstrom). In protein CHK1 (PDB ID: 2YEX), the results of setting the grid box are as follows: center_x = 1.229 center_y = 37.708 center_z = 10.367 with spacing (angstrom) determined by 1 Å. In protein WEE1 (PDB ID: 1X8B), the results of setting the grid box are as follows: center_x = 3.985 center_y = 53.976 center_z = 25.971, with spacing (angstrom) determined by 1 Å. Native ligand preparation from a compound of CHK1 native ligand, namely 5-Methyl-8-(1H-Pyrrol-2-YL)[1,2,4]Triazolo[4,3-A]Quinolin-1(2H)-One and a compound of WEE1 native ligand namely9-Hydroxy-4-Phenylpyrrolo[3,4-C]Carbazole-1,3(2H,6H)-Dione was performed with removing water, selecting the torsion, and setting the number of torsions. Furthermore, the ligand was obtained from website PubChem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) in sdf form [20]. Stages in ligand preparation using Biovia Discovery Studio Visualizer 4.5 started with converting the file into pdb form [21].

Docking validation

Validation was completed by docking the proteins with a compound of CHK1 native ligand namely 5-Methyl-8-(1H-Pyrrol-2-YL)[1,2,4]Triazolo[4,3-A]Quinolin-1(2H)-One and a compound of WEE1 native ligand namely 9-Hydroxy-4-Phenylpyrrolo[3,4-C]Carbazole-1,3(2H,6H)-Dione, after setting the grid box, size, and centre coordinates. The docking procedure used Autodock Vina 1.1.2 [20], with each conformation outcome split and then visualized using Pymol 2.5 [22].

Ligand-protein docking

Molecular docking was conducted using the ligand and protein that had been prepared initially. Ligand was prepared by selecting a set number of torsions, then the grid box size, and centre coordinates were set. Molecular docking procedure was completed by using Autodock Vina 1.1.2 [20].

Visualization of docking result

Biovia Discovery Studio Visualizer 4.5 was used for visualizing the docking result by examining the ligand interaction and 2D diagram [21].

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

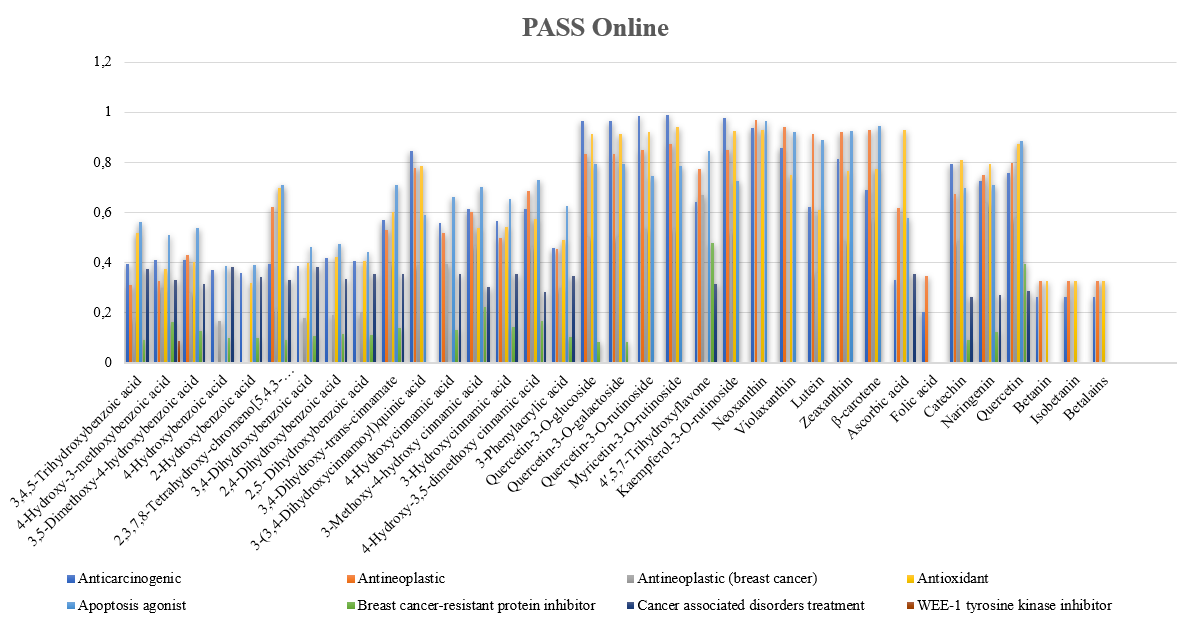

Biology activity prediction using pass online

PASS Online test, commonly used for predicting biology activity with 90% accuracy, has Pa (Probable active) and Pi (Probable inactive) numbers, Pa and Pi activity is considered possible for certain active compounds. The values of Pa and Pi are between 0.000-1.000 in general [31]. The results are shown in fig. 1.

The criteria used to determine the Pa (Probable activity) value are as follows: (1) Pa>0.7 suggests an analogous activity to a drug compound, (2) 0.5 Pa<0.7, indicates different forms, with less possibility of showing analogous activity, and (3) Pa<0.5, implies a lack of analogous activity. Therefore, PASS Online prediction activity is considered an intrinsic property of the compound [31].

Nine compounds had a Pa value<0.5, suggesting a lack of activity as a promising breast cancer drug candidate. When the Pa value is<0.5, the tested compound does not show analogous activity to the drug such as 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid,2-Hydroxybenzoic acid, 3,4-Dihydroxybenzoic acid, 2,4-Dihydroxybenzoic acid, 2,5-Dihydroxybenzoic acid, Folic Acid, Betanin, Isobetanin, Betalains.

Based on the results, 35 compounds were predicted to have antioxidant activity, 30 demonstrated antineoplastic activity, 20 compounds had cancer-associated disorders treatment activity, 27 compounds were predicted to have antineoplastic (breast cancer) activity, five had breast cancer-resistant protein inhibitor activity, and one had WEE-1 tyrosine kinase inhibitor activity [31].

These computational predictions align with previous studies demonstrating the anticancer potential of Amaranthus gangeticus extracts. For instance, an aqueous extract of A. gangeticus inhibited the proliferation of liver (HepG2) and breast (MCF-7) cancer cell lines, with IC₅₀ values of 93.8 µg/ml and 98.8 µg/ml, respectively. In vivo studies on rats indicated that supplementation with A. gangeticus extract reduced tumour marker enzyme activities, suggesting potential chemopreventive properties [9]. Additionally, gold nanoparticles synthesized using phenolic-rich fractions of A. gangeticus exhibited potent anticancer activity against HeLa cells in vitro [32]. Additionally, the selection of key compounds was based not only on PASS Online predictions but also on docking scores and physicochemical properties, including Lipinski’s rule assessment, to ensure their potential as drug candidates.

Physiochemistry prediction using lipinski’s rule of five

The Lipinski’s rule of five is used to predict physicochemical properties of a compound. This website is used for assessing the bioavailability of oral potential of drug [33]. The results are shown in table 1.

Fig. 1: Biology activity prediction from Amaranthus gangeticus using PASS online

Table 1: Physiochemistry prediction from Amaranthus gangeticus using lipinski’s rule of five

| Active compound | Molecular weight | Log P | Hydrogen bond donor | Hydrogen bond acceptor | Molar refractivity | Number of violations |

| 3,4,5-Trihydroxybenzoic acid | 170 | 0.50 | 4 | 5 | 38.39 | 1 |

| 4-Hydroxy-3-methoxybenzoic acid | 168 | 1.10 | 2 | 4 | 41.62 | 0 |

| 3,5-Dimethoxy-4-hydroxybenzoic acid | 198 | 1.11 | 2 | 5 | 48.17 | 0 |

| 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid | 138 | 1.10 | 2 | 3 | 35.07 | 1 |

| 2-Hydroxybenzoic acid | 138 | 1.10 | 2 | 3 | 35.07 | 1 |

| 2,3,7,8-Tetrahydroxy-chromeno[5,4,3-cde]chromene-5,10-dione | 302 | 1.24 | 4 | 8 | 68.45 | 0 |

| 3,4-Dihydroxybenzoic acid | 154 | 0.80 | 3 | 4 | 36.73 | 1 |

| 2,4-Dihydroxybenzoic acid | 154 | 0.80 | 3 | 4 | 36.73 | 1 |

| 2,5-Dihydroxybenzoic acid | 154 | 0.80 | 3 | 4 | 36.73 | 1 |

| 3,4-Dihydroxy-trans-cinnamate | 180 | 1.19 | 3 | 4 | 46.44 | 0 |

| 3-(3,4-Dihydroxycinnamoyl)quinic acid | 354 | -0.64 | 6 | 9 | 82.52 | 1 |

| 4-Hydroxycinnamic acid | 164 | 1.49 | 2 | 3 | 44.78 | 0 |

| 3-Methoxy-4-hydroxy cinnamic acid | 194 | 1.50 | 2 | 4 | 51.33 | 0 |

| 3-Hydroxycinnamic acid | 194 | 0.98 | 3 | 4 | 50.70 | 0 |

| 4-Hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxy cinnamic acid | 224 | 1.51 | 2 | 5 | 57.88 | 0 |

| 3-Phenylacrylic acid | 148 | 1.78 | 1 | 2 | 43.11 | 0 |

| Quercetin-3-O-glucoside | 464 | -0.73 | 8 | 12 | 106.27 | 2 |

| Quercetin-3-O-galactoside | 464 | -0.73 | 8 | 12 | 106.27 | 2 |

| Quercetin-3-O-rutinoside | 610 | -1.88 | 10 | 16 | 137.49 | 4 |

| Myricetin-3-O-rutinoside | 626 | -2.17 | 11 | 17 | 139.16 | 4 |

| 4′,5,7-Trihydroxyflavone | 270 | 2.42 | 3 | 5 | 70.81 | 0 |

| Kaempferol-3-O-rutinoside | 594 | -1.58 | 9 | 15 | 135.83 | 4 |

| Neoxanthin | 312 | -0.05 | 5 | 6 | 77.14 | 0 |

| Violaxanthin | 312 | -0.05 | 5 | 6 | 77.14 | 0 |

| Lutein | 568 | 10.40 | 2 | 2 | 184.10 | 3 |

| Zeaxanthin | 568 | 10.55 | 2 | 2 | 184.17 | 3 |

| β-carotene | 536 | 12.60 | 0 | 0 | 181.39 | 3 |

| Ascorbic acid | 176 | -1.41 | 4 | 6 | 35.26 | 1 |

| Folic acid | 441 | -0.17 | 7 | 13 | 110.31 | 3 |

| Catechin | 290 | 1.55 | 5 | 6 | 72.62 | 0 |

| Naringenin | 272 | 2.51 | 3 | 5 | 70.19 | 0 |

| Quercetin | 302 | 2.01 | 5 | 7 | 74.05 | 0 |

| Betanin | 550 | -2.73 | 8 | 15 | 125.42 | 3 |

| Isobetanin | 550 | -2.73 | 8 | 15 | 125.42 | 3 |

| Betalain | 550 | -2.73 | 8 | 15 | 125.42 | 3 |

Almost all red spinach active compounds meet the Lipinski rule of five, but there are some compounds that violate the rule because the compounds only met two of five requirements, which can cause drug bioavailability problems such as Quercetin-3-O-glucoside, Quercetin-3-O-galactoside, Quercetin-3-O-rutinoside, Myricetin-3-O-rutinoside, Kaempferol-3-O-rutinoside, Lutein, Zeaxanthin, β-carotene, Folic acid, Betanin, Isobetanin, Betalain. These violations impact the permeability and solubility of the compounds, as they are highly hydrophilic, indicated by negative logP values and the hydrogen bond donor and acceptor values. As a result, these compounds struggle to cross lipid membranes and have poor solubility in lipids. Similarly, Lutein, Zeaxanthin, β-carotene, Betanin, Isobetanin, and Betalain also violate Lipinski’s Rule, these compounds have molecular weights exceeding 500 Da, which further indicates that these compounds will have difficulty penetrating due to their large molecular size [33].

When a molecule violates one or more of these criteria, it is considered to have low bioavailability. The criteria including: molecular weight of the compound is below 500 Da, log P<5; hydrogen bond donors<5, hydrogen bond acceptors<10, and molar refractivity is 40-130 [34].

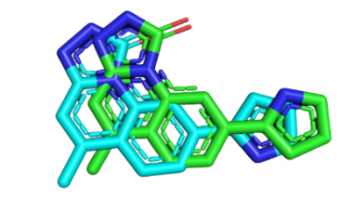

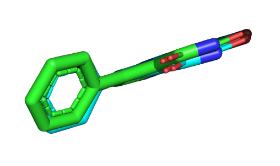

Docking validation

Docking validation result, Root mean Square Deviation (RMSD) value were computed using heavy atoms on CHK1 was 1.5 Å (fig. 2) and WEE1 was 0.634 Å (fig. 3), respectively, suggesting minimal error. The results of the molecular validation analysis were evaluated with RMSD value. Value below 2.00 A show that the molecular docking results are accurate. RMSD value close to zero is preferred as it guarantee greater dependability of ligand binding predictions and signifies a closer location of the ligand in binding site of protein [35].

Ligand-protein docking

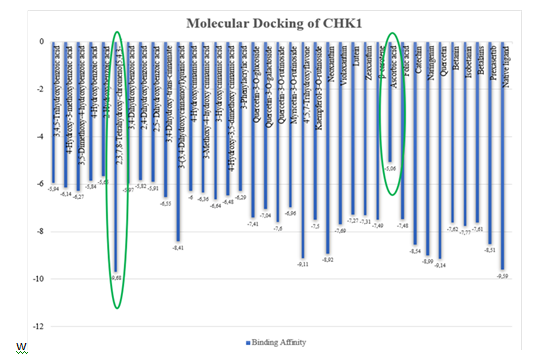

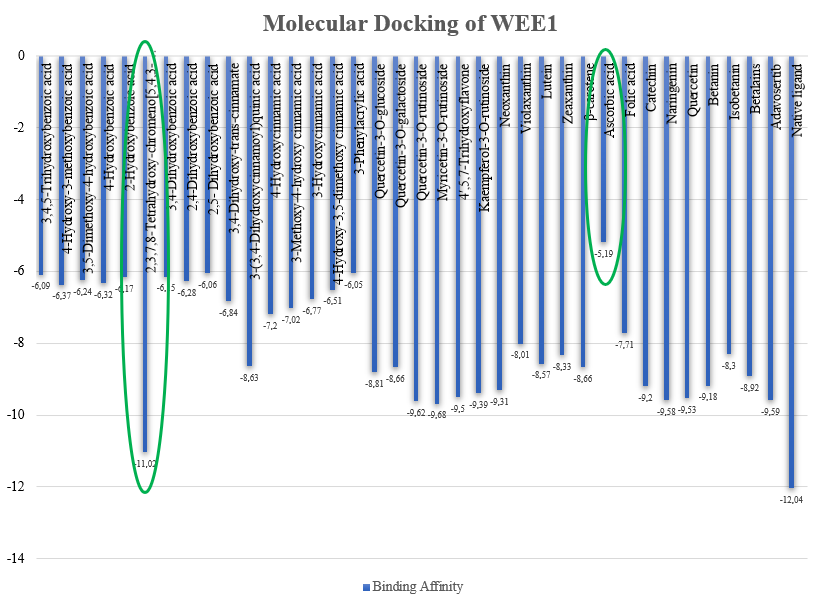

Based on ligand-protein docking with three repetitions show that the standard deviation values from CHK1 ranged from 0.001-0.37, Prexasertib has 0.01, and native ligand has 0.006 and WEE1 ranged from 0.002-0.12, Adavosertib has 0.08, and native ligand has 0.02. Standard deviation is used to measure the distribution of data in sample, which provides information about how far the value in a sample are spread out from average. If the standard deviation value is high, it indicates that the value in the sample is widely spread from average. On the other hand, if the standard deviation value is low, it indicates that the value in the sample is close to the average, this indicates a good data. Based on docking analysis, the binding affinity values were obtained to see the binding affinity between ligand and protein [36]. The results are shown in fig. 4 and fig. 5.

Fig. 2: Validation of native ligand (green) and ligand docking (blue) CHK1

Fig. 3: Validation of native ligand (green) and ligand docking (blue) WEE1

Fig. 4: Binding affinity values from the active compound of red spinach (Amaranthus gangeticus) from CHK1

CHK1 and WEE1 have the same strongest binding affinity namely 2,3,7,8-Tetrahydroxy-chromeno[5,4,3-cde]chromene-5,10-dione and the weakest binding affinity namely ascorbic acid. Binding affinity is a parameter in regulating the bond between ligand and receptor. The binding affinity values obtained for the active compound of red spinach ranged from-9.68 to-5.06 and-11.02 to-5.19 for CHK1 and WEE1. The stronger connection between the protein and the ligand, the lower the binding affinity value [36].

Fig. 5: Binding affinity values from the active compound of red spinach (Amaranthus gangeticus) from WEE1

Visualization experiment was used to observe the outcomes of docking for both the reference and experimental ligand with CHK1 protein. Docking visualization results between the active compound from red spinach, the native ligand, and the drug showed the amino acid residues formation. Between hydrogen bond of native ligand and reference, the same amino acid residue was obtained, namely SER A 147. In contrast, three identical amino acid residues were derived in the hydrophobic and other bonds, namely LEU A 15, LEU A 137, ALA A 36, and VAL A 23. Yin et al. (2019) identified potential CHK1 inhibitors with amino acid residues LEU A 15, VAL A 23, GLY A 90 and LEU A 137 in the hydrophobic bond and hydrogen GLU A 85 and CYS A 87 [37]. The results can be seen in Fig. 6.

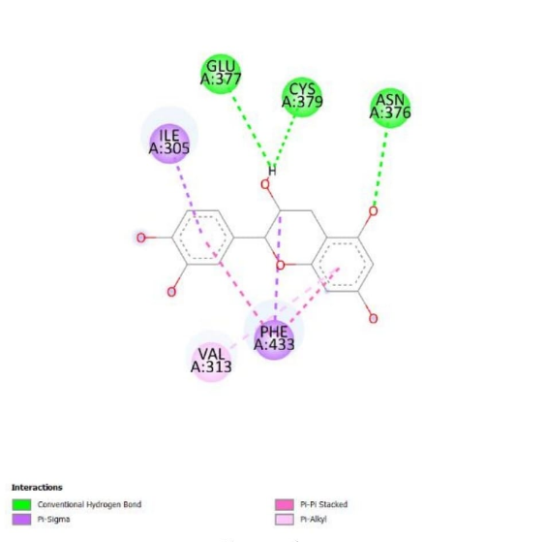

Docking visualization results between the active compound of red spinach, native ligand, and drug indicated the types of interactions formed between WEE1 protein. The conserved binding interactions among the comparator and native ligand were derived in the hydrogen bonds, namely GLU A 377, TYR A 378, hydrophobic bonds, including ILE A 305, VAL A 313, ALA A 326, LYS A 328, VAL A 360, PHE A 433. Similarly, Squire et al. (2005) obtained hydrogen bonds, namely GLU A 377, as well as hydrophobic bonds of ILE A 305, VAL A 313, ALA A 326, and PHE A 433 [38].

On CHK1, five compounds, namely 3,4,5-Trihydroxybenzoic acid, 3-Methoxy-4-hydroxy cinnamic acid, 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid, 3-Phenyl acrylic acid, and 3-(3,4-Dihydroxy cinnamoyl)quinic acid, were found to have identical hydrophobic amino acid residues as native ligand and drug. Meanwhile, on WEE1, the native ligand, the comparator, and the results by Squire et al. (2005) share the same hydrophobic and hydrogen bonding with eleven active compounds. These include3,4,5-Trihydroxybenzoic acid, 3,5-Dimethoxy-4-hydroxybenzoic acid, 2,3,7,8-Tetrahydroxy-chromeno[5,4,3-cde]chromene-5,10-dione,3-(3,4-Dihydroxy-cinnamoyl)quinic acid, 3-Methoxy-4-hydroxy cinnamic acid, 4-Hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxy cinnamic acid, 4′,5,7-Trihydroxyflavone, Catechin, Quercetin, Betanin, and Isobetanin. Docking of red spinach compounds showed conventional and carbon-hydrogen bonds. An increased number of hydrogen bonds contributes to a more stable connection between the ligand and the protein. Both the hydrophobic and hydrogen bonds formed served as indicators of interaction intensity between the protein and ligand [35].

CHK1 WEE1

Fig. 6: Molecular docking results showing key hydrogen bond and hydrophobic interactions between CHK1, WEE1 and selected red spinach compounds

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the validation of proteins CHK1 (2YEX) and WEE1 (1X8B) had RMSD 2 Å. Based on PASS Online test prediction, 26 compounds have an anticancer activity, while evaluation of drug-likeness suggested that 26 compounds have potential oral bioavailability according to Lipinski's rule of five. Furthermore, docking analysis showed that the active compound of red spinach had a binding pocket on LEU A 15, VAL A 23, and LEU A 137 signifying the inhibitory side of CHK1. There was also a binding pocket on GLU A 377, ILE A 305, VAL A 313, ALA A 326, and PHE A 433, implying the inhibitory side of WEE1. These findings suggest that red spinach compounds may serve as potential CHK1 and WEE1 inhibitors, warranting further in vitro and in vivo validation.

FUNDING

The research was financed by the Faculty of Pharmacy, Universitas Sumatera Utara of 2023, with research contract number 222/UN5.2.1.11/SK/KPM/2023, awarded on September 18th, 2023.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: ASR, HSW, EDLX, NAZ; table Work: ASR, HSW, EDLX, NAZ, CA, TR; Supervision: ASR, HSW, EDLX, NAZ; Revisions: HSW, CA, TR; Writing and Editing: CA, TR; Proofreading: HSW, CA, TR.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The author has no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

Adam R, Dell Aquila K, Hodges L, Maldjian T, Duong TQ. Deep learning applications to breast cancer detection by magnetic resonance imaging: a literature review. Breast Cancer Res. 2023;25(1):87. doi: 10.1186/s13058-023-01687-4, PMID 37488621.

Sanganna B, Chitme HR, Vrunda K, Jamadar MJ. Antiproliferative and antioxidant activity of leaves extracts of Moringa oleifera. Int J Curr Pharm Sci. 2016 Oct 18;8(4):54. doi: 10.22159/ijcpr.2016v8i4.15278.

Elias A, Habbu PV, Iliger S. Preparation, characterization and screening of silver nanoparticles using phenolic-rich fractions of Amaranthus gangeticus L. for its in vitro antioxidant anti-diabetic and anticancer activities. RGUHS J Pharm Sci. 2021;11(3):32-8. doi: 10.26463/rjps.11_3_5.

Junedi S, Hermawan A, Fitriasari A, Setiawati A, Susidarti RA, Meiyanto E. The doxorubicin-induced induced G2/M arrest in breast cancer cells modulated by natural compounds naringenin and hesperidin. Indones J Cancer Chemoprevent. 2021 Oct 18;12(2):83-9. doi: 10.14499/indonesianjcanchemoprev12iss2pp83-89.

Dey S, Roychoudhury R, Malakar S, Sarkar R. Screening of breast cancer from thermogram images by edge detection aided deep transfer learning model. Multimed Tools Appl. 2022 Jan 8;81(7):9331-49. doi: 10.1007/s11042-021-11477-9, PMID 35035264.

Lukasiewicz S, Czeczelewski M, Forma A, Baj J, Sitarz R, Stanislawek A. Breast cancer epidemiology risk factors, classification prognostic markers and current treatment strategies an updated review. Cancers. 2021 Aug 25;13(17):4287. doi: 10.3390/cancers13174287, PMID 34503097.

Solikhah S, Promthet S, Hurst C. Awareness level about breast cancer risk factors barriers, attitude and breast cancer screening among Indonesian Women. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2019 Mar 26;20(3):877-84. doi: 10.31557/APJCP.2019.20.3.877, PMID 30912407.

Tavani A, La Vecchia C. Fruit and vegetable consumption and cancer risk in a mediterranean population. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995;61(6)Suppl:1374S-7S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/61.6.1374S, PMID 7754990.

Sani HA, Rahmat A, Ismail M, Rosli R, Endrini S. Potential anticancer effect of red spinach (Amaranthus gangeticus) extract. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2004;13(4):396-400. PMID 15563447.

Zhu L, Xue L. Kaempferol suppresses proliferation and induces cell cycle arrest apoptosis and DNA damage in breast cancer cells. Oncol Res. 2019 Jun 21;27(6):629-34. doi: 10.3727/096504018X15228018559434, PMID 29739490.

Song W, Dang Q, Xu D, Chen Y, Zhu G, Wu K. Kaempferol induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in renal cell carcinoma through EGFR/p38 signaling. Oncol Rep. 2014;31(3):1350-6. doi: 10.3892/or.2014.2965, PMID 24399193.

Bruyer A, Dutrieux L, De Boussac H, Martin T, Chemlal D, Robert N. Combined inhibition of Wee1 and Chk1 as a therapeutic strategy in multiple myeloma. Front Oncol. 2023 Dec 6;13:1271847. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1271847, PMID 38125947.

Song X, Wang L, Wang T, Hu J, Wang J, Tu R. Synergistic targeting of CHK1 and mTOR in MYC-driven tumors. Carcinogenesis. 2021 Apr 17;42(3):448-60. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgaa119, PMID 33206174.

Ghelli Luserna Di Rorà AG, Bocconcelli M, Ferrari A, Terragna C, Bruno S, Imbrogno E. Synergism through WEE1 and CHK1 inhibition in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancers. 2019 Oct 25;11(11):1654. doi: 10.3390/cancers11111654, PMID 31717700.

Cole KA, Pal S, Kudgus RA, Ijaz H, Liu X, Minard CG. Phase I clinical trial of the Wee1 inhibitor adavosertib (AZD1775) with irinotecan in children with relapsed solid tumors: a COG phase I consortium report (ADVL1312). Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(6):1213-9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-3470, PMID 31857431.

Liu JF, Xiong N, Campos SM, Wright AA, Krasner CN, Schumer ST. A phase II trial of the Wee1 inhibitor adavosertib (AZD1775) in recurrent uterine serous carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(15Suppl):6009. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2020.38.15_suppl.6009.

Cash T, Fox E, Liu X, Minard CG, Reid JM, Scheck AC. A phase 1 study of prexasertib (LY2606368) a CHK1/2 inhibitor in pediatric patients with recurrent or refractory solid tumors including CNS tumors: a report from the childrens oncology group pediatric early phase clinical trials network (ADVL1515). Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2021;68(9):e29065. doi: 10.1002/pbc.29065.

Konstantinopoulos PA, Lee JM, Gao B, Miller R, Lee JY, Colombo N. A phase 2 study of prexasertib (LY2606368) in platinum-resistant or refractory recurrent ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2022;167(2):213-25. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2022.09.019, PMID 36192237.

Agu PC, Afiukwa CA, Orji OU, Ezeh EM, Ofoke IH, Ogbu CO. Molecular docking as a tool for the discovery of molecular targets of nutraceuticals in diseases management. Sci Rep. 2023 Aug 17;13(1):13398. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-40160-2, PMID 37592012.

Trott O, Olson AJ. Autodock vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization and multithreading. J Comput Chem. 2010 Jan 30;31(2):455-61. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334, PMID 19499576.

Dassault systemes. BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer; 2016.

Schrodinger LL. The PyMOL molecular graphics system. Version 2.5; 2015.

Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001 Mar 1;46(1-3):3-26. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0, PMID 11259830.

Lagunin A, Stepanchikova A, Filimonov D, Poroikov V. Pass: prediction of activity spectra for biologically active substances. Bioinformatics. 2000;16(8):747-8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.8.747, PMID 11099264.

Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat TN, Weissig H. The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000 Jan 1;28(1):235-42. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235, PMID 10592235.

Kim S, Thiessen PA, Bolton EE, Chen J, Fu G, Gindulyte A. Pubchem substance and compound databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016 Jan 4;44(D1):D1202-13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv951, PMID 26400175.

Kalanjati V, Pratiwi MP, Syakdiyah NH, Widiasi ED, Anggraeni MR, Pratiwi IA. Pengaruh ekstrak bayam merah (Amaranthus gangeticus) terhadap morfologi stratum hipokampus model anak mencit pascasapih induk yang terpapar timbal selama masa kehamilan. MKB. 2014;46(3):125-9. doi: 10.15395/mkb.v46n3.116.

Sarker U, Ercisli S. Salt eustress induction in red amaranth (Amaranthus gangeticus) augments nutritional phenolic acids and antiradical potential of leaves. Antioxidants (Basel). 2022 Dec 9;11(12):2434. doi: 10.3390/antiox11122434, PMID 36552642.

Sarker U, Oba S. Color attributes betacyanin and carotenoid profiles bioactive components and radical quenching capacity in selected Amaranthus gangeticus leafy vegetables. Sci Rep. 2021 Jun 2;11(1):11559. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-91157-8, PMID 34079029.

Sarker U, Oba S. Polyphenol and flavonoid profiles and radical scavenging activity in leafy vegetable Amaranthus gangeticus. BMC Plant Biol. 2020 Nov 2;20(1):499. doi: 10.1186/s12870-020-02700-0, PMID 33138787.

Matin MM, Roshid MH, Bhattacharjee SC, Azad AK. Pass predication antiviral in vitro antimicrobial and ADMET studies of rhamnopyranoside esters. Med Res Arch. 2020 Jul 22;8(7):1-13. doi: 10.18103/mra.v8i7.2165.

Elias A, Habbu PV, Iliger S. Preparation characterization and screening of gold nanoparticles using phenolic-rich fractions of Amaranthus gangeticus L. for its in vitro antioxidant, anti-diabetic and anti-cancer activities. J Pharm Res Int. 2021;33(57A):425-39. doi: 10.9734/jpri/2021/v33i57A34016.

Roskoski R. Rule of five violations among the FDA-approved small molecule protein kinase inhibitors. Pharmacol Res. 2023;191:106774. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2023.106774, PMID 37075870.

VM. In silico molecular screening and docking approaches on antineoplastic agent irinotecan towards the marker proteins of colon cancer. Int J Appl Pharm VP. 2023;15(5):84-92. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2023v15i5.48523.

Shamsian S, Sokouti B, Dastmalchi S. Benchmarking different docking protocols for predicting the binding poses of ligands complexed with cyclooxygenase enzymes and screening chemical libraries. BioImpacts. 2024;14(2):29955. doi: 10.34172/bi.2023.29955, PMID 38505677.

Nguyen NT, Nguyen TH, Pham TN, Huy NT, Bay MV, Pham MQ. Autodock vina adopts more accurate binding poses but Autodock4 forms better binding affinity. J Chem Inf Model. 2020 Jan 27;60(1):204-11. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.9b00778, PMID 31887035.

Yin K, Zhao G, Xu C, Qiu X, Wen B, Sun H. Prediction of Toxoplasma gondii virulence factor ROP18 competitive inhibitors by virtual screening. Parasit Vectors. 2019 Mar 13;12(1):98. doi: 10.1186/s13071-019-3341-y, PMID 30867024.

Squire CJ, Dickson JM, Ivanovic I, Baker EN. Structure and inhibition of the human cell cycle checkpoint kinase WEE1A kinase: an atypical tyrosine kinase with a key role in CDK1 regulation. Structure. 2005;13(4):541-50. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.12.017, PMID 15837193.