Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 4, 2025, 159-165Original Article

ISOLATION, MANUFATURE AND QUALITATIVE TEST OF CELLULOSE MICROCRYSTALLIZATION POWDER FROM KETAPANG LEAVES (TERMINALIA CATAPPA L.) USING CHEMICAL DELIGNIFICATION AND HYDROLISIS METHODS

YUSPA, MUHAMMAD, FATIMAH, NUR MAULIDAH, RAIDAH LUTHFIA, YULIANITA PRATIWI INDAH LESTARI*

Departement of Pharmaceutics, Faculty of Pharmacy, Universitas Muhammadiyah Banjarmasin, Gubernur Syarkawi, Barito Kuala, Kalimantan Selatan, Indonesia

*Corresponding author: Yulianita Pratiwi Indah Lestari; *Email: yulianita.pratiwi@umbjm.ac.id

Received: 21 Feb 2025, Revised and Accepted: 28 May 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: This study aimed to synthesize and characterize Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) from ketapang leaves (Terminalia catappa L.) and compare it with commercial Avicel PH 102.

Methods: Ketapang leaves underwent delignification using sodium hydroxide (NaOH), followed by acid hydrolysis using optimized Hydrochloric Acid (HCl) concentrations. The resulting Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) was characterized through color reaction; organoleptic, solubility, pH, melting point, microscopic, and fourier transform infrared spectroscopy analyses, with Avicel PH 102 as the comparator.

Results: The α-cellulose yield from ketapang leaves was 24.13%, and Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) yield reached 83.70%. Hydrochloric Acid (HCl) 1 M gave the highest Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) yield of 96%. Microcrystalline Cellulose Ketapang Leaves (MCCKL) was a yellowish-white, odorless, tasteless crystalline powder, similar to Avicel PH 102. It was insoluble in water, alcohol, ether, and acids/bases, meeting Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) standards. The pH was 6.47 (standard: 5.0–7.5), and the melting point was 262 °C, comparable to Avicel PH 102. Microscopically, Microcrystalline Cellulose Ketapang Leaves (MCCKL) fibers appeared longer and larger but remained suitable as tablet excipients. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy confirmed the presence of O-H, C-H, C-OH, and β-glycoside groups, indicating structural similarity to commercial Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC).

Conclusion: This study demonstrates the successful synthesis of Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) from ketapang leaves with an 83.70% yield from 24.13% α-cellulose. The resulting Microcrystalline Cellulose Ketapang Leaves (MCCKL) showed comparable physicochemical properties to commercial Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) (Avicel PH 102), including pH, solubility, melting point, and functional groups. Additional tests showed favorable values for flow rate, moisture content, and compressibility, suggesting that Microcrystalline Cellulose Ketapang Leaves (MCCKL) has strong potential as a direct compression tablet filler.

Keywords: Characterization, Delignification, Hydrolysis, Ketapang leaves (Terminalia catappa L.), Microcrystalline cellulose

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i4.54021 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) is an important ingredient in the food, cosmetics, and pharmaceutical industries. In the pharmaceutical sector, Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) is commonly used as an excipient in tablet manufacturing, particularly in direct compression methods, which require ingredients of high quality and consistency [1]. However, to date, approximately 90% of drug raw materials in Indonesia, including Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC), still rely heavily on imports. According to data from the Central Statistics Agency recorded that in 2019, Indonesia imported 4,359,762 kg of MCC under HS Code 39129090, valued at US$ 27,309,530, indicating high demand for Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) in the country [2]. This dependence increases the cost of domestic production and makes the pharmaceutical industry vulnerable to fluctuations in global prices and supply. Therefore, developing Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) from local sources is essential to reduce import dependence and strengthen the independence of the domestic industry.

One of the most widely used Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) products in the pharmaceutical industry is Avicel PH 102, known for its large particle size, good flowability, and high tap index [3]. However, Avicel is still imported at a relatively high price, prompting the need for a more economical and locally available alternative [4]. Hence, the substitute alternative for this limitation is using natural ingredients such as cellulose. Cellulose is present in almost all parts of plants, such as Limpasu, Baby Orange, Kapok, and Ketapang (Terminalia catappa L.), a plant widely distributed in tropical regions including Southeast Asia, Northern Australia, and Polynesia. Ketapang is rich in secondary metabolites such as flavonoids, tannins, alkaloids, and saponins, which provide antioxidant benefits [5, 6]. Additionally, ketapang contains a high cellulose content, particularly in the stem and shell, reaching up to 41.80% [7, 8]. This makes ketapang a promising source for Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) production as a potential alternative to Avicel.

Based on this background, this study aims to synthesize microcrystalline cellulose from ketapang leaves, characterize its physicochemical properties, and compare it with commercial Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC), namely Avicel PH 102. This research is expected to contribute to the development of local Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) sources that can reduce import dependence and support the self-sufficiency of Indonesia’s pharmaceutical industry.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

The tools used in this study included sterile gloves (GEA), masks (ONEMED), a blender (PHILIPS), capillary pipes, parchment paper, glass jars, sieves, head caps (SENSI), digital scales, electric stoves, ovens, pH sticks, pH meters, an Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) instrument (BRUKER), a melting point apparatus, and various laboratory glassware (PYREX). The main ingredients in this study were ketapang leaves collected from Banjarmasin City, South Kalimantan. The chemical materials used included Avicel PH 102 (as reference), 70% ethanol, distilled water (aquadest), nitric acid (HNO₃), sodium nitrite (NaNO₂), hydrochloric acid (HCl), sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl), potassium iodide (KI), sodium hydroxide (NaOH), zinc chloride (ZnCl₂), and iodine (I₂).

Research procedures

Ketapang leaves (Terminalia catappa L.) collection

The ketapang (Terminalia catappa L.) leaves used in this study were collected from Banjarmasin City, South Kalimantan, Indonesia (Geographical coordinates:-3.3274° S, 114.5908° E). The plant material was authenticated at the Laboratory of the Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Lambung Mangkurat University. The specimen was assigned voucher number III-24-003 for documentation and verification purposes. This determination ensured the plant species’ accuracy in this research, aligning with its taxonomic classification.

Ketapang leaves (Terminalia catappa L.) simplicia preparation

Once collected, the ketapang leaves were sorted while still wet to remove any dirt or foreign objects. They were then thoroughly washed under running water, drained, and chopped into smaller pieces. The leaves were left to air dry in a shaded area protected from direct sunlight to prevent degradation of active compounds. After drying, the leaves were ground using a blender and then sieved using a 60-mesh sieve to obtain uniform particle size for further processing [9].

Insulation of α-cellulose from ketapang leaves (Terminalia catappa L.)

A total of 150 g of ketapang leaf simplicia powder was placed in a container and mixed with 2L of sodium hydroxide solution and 3.5% nitric acid containing 20 mg of sodium nitrite. The subsequent procedure followed the method described in our previous research [10].

Delignification process of ketapang leaves (Terminalia catappa L.)

Following the insulation of α-cellulose from ketapang leaves, the resulting material was subjected to hydrolysis using hydrochloric acid at varying concentrations (1M, 2M, and 3M). For each g of α-cellulose, 20 ml of the respective acid concentration was added. The hydrolysis process was carried out at 105 °C for 30 min using a hot plate equipped with a digital thermometer and temperature controller. To ensure consistency and prevent excessive evaporation or temperature fluctuations, the reaction was conducted in a sealed container. After the hydrolysis process, the residue was filtered and washed with distilled water until the pH of the filtrate matched that of the washing solution, indicating neutrality. The final residue was then dried to obtain Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) derived from ketapang leaves. The resulting yield was subsequently calculated to determine the optimum conditions based on the hydrolysis data [11] (with modifications).

Synthesis of microcrystalline cellulose from ketapang leaves (Terminalia catappa L.)

Following the delignification process, chemical hydrolysis was conducted to convert α-cellulose powder into Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC). This process involved heating Hydrochloric Acid (HCl) to an optimal concentration in a beaker. The reaction was maintained at 105 °C for 15 min using a hot plate equipped with a digital thermometer and temperature controller. After hydrolysis, 25 ml of cold distilled water was added to the mixture, followed by stirring. The solution was then allowed to rest on the hot plate for an additional 1 hour. The resulting Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) was filtered and washed overnight using distilled water until the pH of the wash water reached a neutral value. The purified Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) was then dried in an oven at 105 °C until a constant weight was achieved [9, 12].

Evaluation of ketapang leaves (Terminalia catappa L.) microcrystalline cellulose (MCC)

The organoleptic examination

Organoleptic testing includes an assessment of solubility, taste, odor, color, and shape of the Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) sample.

Microscopic testing

Microscopic examination was conducted to observe specific plant fragment structures. The cellulose fiber morphology of Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) derived from ketapang leaves was compared to Avicel PH 102 using 10× magnification to identify structural differences [9].

Qualitative identification using iodinated zinc-chloride

A solution was prepared by dissolving 6.5 g of potassium iodide and 20 g of zinc chloride in 10.5 ml of water. Subsequently, 0.5 g of iodine was added, and the mixture was shaken for 15 min. Approximately 10 mg of Microcrystalline Cellulose Ketapang Leaves (MCCKL) was placed on a watch glass and mixed with 2 ml of the zinc chloride solution. The appearance of a blue-purple color indicated a positive identification for cellulose [13].

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) analysis

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was conducted on Microcrystalline Cellulose Ketapang Leaves (MCCKL) to identify functional groups and compare structural similarities with commercial Avicel PH 102.

Solubility testing

Solubility was tested using several solvents: 95% ethanol, ether, distilled water, 2N Hydrochloric Acid (HCl), and 1N sodium hydroxide (NaOH), to assess the compound’s physicochemical behavior [14].

Melting point testing

Melting point was evaluated using a capillary method with a gradual temperature increase of 1–2 °C per minute until the powder melted or thermally degraded. The typical melting range for MCC is 260–270 °C, which reflects its purity and thermal stability [14].

pH testing

A 1 g sample was dispersed in 2 ml of CO₂-free distilled water. The pH was measured using a pH stick. The ideal Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) pH range is 5.0–7.5 [14].

Physical characterization of ketapang leaves (Terminalia catappa L.) microcrystalline cellulose ketapang leaves (MCCKL)

Drying loss test

Drying loss should not exceed 7%. It was determined gravimetrically by weighing 1 g of Microcrystalline Cellulose Ketapang Leaves (MCCKL), drying it at 105 °C for 30 min, and repeating until a constant weight was achieved [14].

Moisture content testing

According to the Handbook of Pharmaceutical Excipients, Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) moisture content should be below 5%. The test was conducted using a moisture balance, weighing 10 g of Microcrystalline Cellulose Ketapang Leaves (MCCKL) into the device [1].

Flow time and angle of repose measurement

100 g of Microcrystalline Cellulose Ketapang Leaves (MCCKL) was poured into a closed funnel. The time required for the entire sample to flow out was recorded. The angle of repose was calculated using the formula:

Where H is cone height and r is cone radius [15].

Compressibility index measurement

To evaluate flow properties, 25 g of Microcrystalline Cellulose Ketapang Leaves (MCCKL) was poured into a graduated cylinder to measure bulk volume (V₁). After 400 taps using a tapped density tester, the new volume (V₂) was recorded.

Bulk density

Tapped density

Compressibility indeks

Good Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) typically demonstrates a true density of 1.512–1.668 g/cm³, a bulk density of 0.337 g/cm³, and a tapped density of 0.478 g/cm³ [16].

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The Ketapang leaves (Terminalia catappa L.) was used in this study. The leaves were collected from the Banjarmasin City area, South Kalimantan Province, Indonesia. The initial stages involved collecting fresh plant simplicia, followed by the preparation of simplicia, extraction, delignification, isolation of α-cellulose, synthesis of Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC), and its subsequent identification and characterization. One essential step in this process was transforming the simplicia into powder before maceration. To obtain fine simplicia powder, the leaves underwent washing, cutting, drying, grinding, and sieving using a 60-mesh sieve. The maceration process was performed using 70% ethanol, applied in three separate 24 h periods. After maceration, the active compounds were separated from the plant residue through filtration and drying.

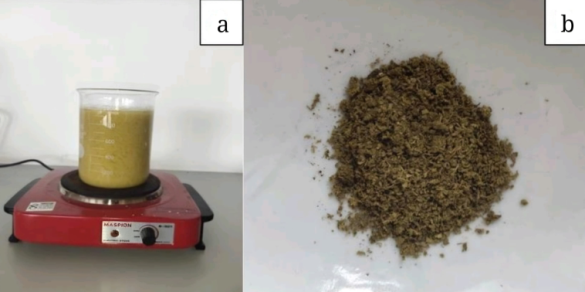

Fig. 1: (a) Bleaching process; (b) ketapang leaves (Terminalia catappa L.) simplicia powder

After the extraction process, the active compounds are separated from the residue through filtration and drying. The next step involves isolating α-cellulose, which begins with the chemical delignification process aimed at removing lignin. To achieve this, the residue from the extraction is treated with a 10% NaOH solution. Following this, sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) is used for the bleaching step. When sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) is dissolved in water, it produces hydroxyl ions and hypochlorous acid (HOCl), both of which are strong oxidizing agents. These substances are capable of breaking ether and lignocellulosic bonds in the lignin structure, thereby contributing to the whitening of fibers and cellulose powder. The bleaching process effectively removes residual lignin from the pulp, resulting in a brighter and whiter product [17].

After bleaching, the residue is rinsed thoroughly with distilled water until the rinsing water reaches a neutral pH. The cleaned pulp is then dried in an oven at 50 °C for 12 to 24 h, yielding α-cellulose powder with a recovery rate of 24.13% based on the initial simplicia weight. To obtain Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC), a chemical hydrolysis method using dilute hydrochloric acid (HCl) is applied. The concentration of HCl significantly affects the final yield. A higher concentration of hydrochloric acid (HCl) promotes more extensive hydrolysis reactions, which leads to the formation of more soluble glucose monomers during washing. This, in turn, may decrease the overall Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) yield [11, 13].

The results of the hydrochloric acid (HCl) concentration optimization and its effect on yield are presented in table 1 below.

Table 1 (Organoleptic test) shows that Microcrystalline Cellulose Ketapang Leaves (MCCKL) produced using 1 M, 2 M, and 3 M hydrochloric acid (HCl) have similar characteristics in terms of shape, color, and odor. The physical appearance of the final Microcrystalline Cellulose Ketapang Leaves (MCCKL) product remains consistent despite the variation in acid concentration. Among the three, the Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) obtained using 1 M hydrochloric acid (HCl) yielded the highest cellulose content at 96%, making it the optimal concentration for large-scale production. In the subsequent step, Microcrystalline Cellulose Ketapang Leaves (MCCKL) is produced through chemical hydrolysis, where the dried α-cellulose pulp is heated in 1 M hydrochloric acid (HCl) solution. Although higher hydrochloric acid (HCl) concentrations can accelerate the hydrolysis process, they tend to generate more dissolved glucose monomers during leaching, which reduces the overall yield of Microcrystalline Cellulose Ketapang Leaves (MCCKL (Lestari et al., 2022) [13, 18]. Therefore, using 1 M hydrochloric acid (HCl) is considered ideal for cellulose hydrolysis due to its balance of effectiveness and yield. The hydrolysis process and resulting Microcrystalline Cellulose Ketapang Leaves (MCCKL) can be seen in fig. 2 below.

Table 1: HCl optimization results in ketapang leaves (Terminalia catappa L.) microcrystalline cellulose ketapang leaves (MCCKL)

| Evaluation | HCl | ||

| 1 M | 2 M | 3 M | |

| Initial mass (gr) | 1±0.008 | 1±0.008 | 1±0.008 |

| Final mass (gr) | 0.961±0.020 | 0.74±0.030 | 0.54±0.040 |

| Yield (%) | 96% | 74% | 54% |

| Organoleptic | Powdery, white colored, odorless, tasteless | Powdery, white colored, odorless, tasteless | Powdery, white colored, odorless, tasteless |

Mean±SD (Standard Deviation), *n = 3 replications; HCl yield concentration 1 M = 96%, 2 M = 74%, 3 M = 54%, at the highest HCl yield concentration at HCl 1 M (96% result).

Fig. 2: (a) Hydrolsis process of α-cellulose from ketapang leaves (Terminalia catappa L.); (b) Results of microcrystalline cellulose ketapang leaves (MCCKL)

During the hydrolysis process, the cellulose microfibrils are partially broken down, particularly in their amorphous regions. These disordered areas degrade first, leaving behind the crystalline regions, tightly packed cellulose molecules arranged in an orderly structure. This transformation results in Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) with a lower degree of polymerization, approximately n ≈ 220.

As shown in the evaluation table, the starting weight for all hydrochloric acid (HCl) concentrations (1 M, 2 M, and 3 M) was 1±0.008 g. However, the final weight and yield varied significantly: 0.96±0.020 g (96%) for 1 M HCl, 0.74±0.030 g (74%) for 2 M, and 0.54±0.040 g (54%) for 3 M. Despite these differences in yield, the organoleptic properties remained the same, white, odorless, and tasteless powder.

After filtration, the resulting Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) is dried in an oven at 57–60 °C for approximately one hour or until fully dried. The dried Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) is then crushed and stored at room temperature in a desiccator. The final yield of Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) from ketapang leaves through chemical hydrolysis reached 83.70%, while the yield of α-cellulose from the delignification of simplicia powder was 24.13%. The α-cellulose isolation method is illustrated in fig. 1.

Table 3: Yield of α-cellulose and ketapang leaves (Terminalia catappa L.) microcrystalline cellulose ketapang leaves (MCCKL)

| Plant | Simplicia weight (g) | α-Cellulose | Weight α-cellulose for hydolisis (g) | Microcrystalline cellulose | ||

| Weight (g) | Yield (%) | Weight (g) | Yield (%) | |||

| Ketapang leaves | 300±0.816 | 36.19±1.087 | 24,13 | 10±0.146 | 8.37±0.091 | 83,70 |

Mean±SD (Standard Deviation), *n = 3 replications

The yield values are presented as mean±SD (standard deviation), with n = 3 replicates. For α-cellulose obtained from ketapang leaves, the initial weight was 36.19 g with a yield of 24.13%. Meanwhile, the microcrystalline cellulose (MCC) produced weighed 8.37 g, corresponding to a yield of 83.70%.

The yield of Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) from ketapang leaves obtained through chemical hydrolysis is 83.70%, while the yield of α-cellulose from the chemical delignification of simplicia powder is 24.13%. These results demonstrate that ketapang leaves have potential as an alternative raw material for tablet production.

Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) yield can vary depending on the source of raw material, extraction methods, and chemical treatments used. Several studies have reported Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) yields from different plant sources. For example, Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) derived from water hyacinth after 2 h of hydrolysis showed a yield of 95% [10]. Similarly, Lestari et al. [19] reported an 80% Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) yield from kapok fruit peel using enzymatic hydrolysis.

Moreover, Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) from empty oil palm bunches, produced through a multistage delignification process involving HNO₃ and NaNO₂ followed by HCl hydrolysis, achieved an optimal yield of 80.73% at 3 M HCl concentration after 30 min [20]. Research on the white lotus plant (Nymphaea nuchal) by Lestari et al. (2023) [9] found that the highest Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) yield came from the leaves (97%), followed by petioles (89%), flowers (88%), and flower stalks (83%).

Additionally, a study on Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) production from baby orange peel (Citrus sinensis) via acid hydrolysis yielded 82.53% MCC from α-cellulose [13]. Collectively, these studies illustrate that Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) produced from various natural sources such as baby orange peel (82.53%), white lotus (83–97%), empty oil palm bunches (80.73%), water hyacinth, and kapok fruit peels (enzymatic hydrolysis) exhibit characteristics comparable to commercial Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) (Avicel).

This evidence supports the viability of using microcrystalline cellulose (MCC) derived from these natural materials as alternative raw materials in pharmaceutical and other industrial applications.

Table 3: Ketapang leaves (Terminalia catappa L.) powder quality test results

| Variable | Microcrystalline cellulose ketapang leaves (MCCKL) | Avicel® PH 102 | Literature |

| Organoleptic | Powdery, white colored crystals almost yellow, odorless, and tasteless | Powdery, white colored crystals, odorless, and tasteless | Powdery, white colored crystals, odorless, and tasteless |

| Qualitative identification | Violet-blue | Violet-blue | Violet-blue |

| Solubility |

|

|

|

| Melting Point | 262 °C±0.816 | 262 °C±0.816 | 260 °C-270 °C |

| pH | 6.47±0.123 | 6.0±0.244 | 5-7.5 |

Mean±SD (Standard Deviation), *n = 3 replications

The quality tests of Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) leaf powder were conducted with n = 3 replicates and are presented as mean±SD (standard deviation). The results indicate that the Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) leaf powder meets quality standards comparable to commercial Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) Avicel. The melting point was found to be 262 °C, identical to that of Avicel PH 102, and the pH value was within the range of 5.0 to 7.5, also matching Avicel PH 102.

Organoleptic properties, including shape, color, odor, and taste, are summarized in table 3 alongside their respective test applications. Solubility tests were performed using various solvents such as ether, water, 2 N HCl, 1 N NaOH, and 95% ethanol. Solubility refers to the ability of a substance, whether solid, liquid, or gas, to dissolve in another substance, resulting in a homogeneous solution. The Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) from ketapang leaves was found to be insoluble in water, 95% ethanol, 2 N HCl, and ether and exhibited poor solubility in 1 N NaOH.

The pH of Microcrystalline Cellulose Ketapang Leaves (MCCKL) was measured using pH indicator strips, resulting in a value of 6.27. According to Rowe et al. (2009) [14], the acceptable pH range for Avicel PH 102 is between 5.0 and 7.5. Melting point determination tests revealed that both Microcrystalline Cellulose Ketapang Leaves (MCCKL) and Avicel PH 102 have melting points of approximately 262 °C, consistent with the Handbook of Pharmaceutical Excipients (2009), which lists Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) melting points between 260 °C and 270 °C.

Based on these findings, it can be concluded that Microcrystalline Cellulose Ketapang Leaves (MCCKL) fulfills the required quality standards, as its test results closely resemble those of commercial Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) Avicel.

Further characterization of Microcrystalline Cellulose Ketapang Leaves (MCCKL) and Avicel PH 102 included tests for angle of repose, moisture content, drying shrinkage, flow rate, and compressibility. The comparative results are detailed in table 4.

Table 4: Comparison of microcrystalline cellulose ketapang leaves (MCCKL) and Avicel PH 102 evaluation after characterization

| S. No. | Evaluation | Microcrystalline cellulose ketapang leaves (MCCKL) | Avicel® PH 102 | Reference |

| 1. | Angle of repose | 30.60°±0.081 | 29.15°±0.694 | 34.4° |

| 2. | Flow rate | 0.48 g/s±0.004 | 0.88 g/s±0.008 | 1.41 g/s |

| 3. | Drying shrinkage | 4%±0.816 | 4%±0.816 | <7% |

| 4, | Compressibility | 20%±0.141 | 21%±0.816 | <21% |

| 5. | Water content | 5.13%±0.124 | 5.08%±0.016 | <5% |

Mean±SD (Standard Deviation), *n = 3 replications

The characterization tests of microcrystalline cellulose (MCC) from ketapang leaves were conducted with n = 3 replicates, and results are expressed as mean±SD (standard deviation). Overall, the Microcrystalline Cellulose Ketapang Leaves (MCCKL) met several reference standards, though some parameters did not fully comply with literature requirements. Specifically, the results showed that the angle of repose and flow rate did not meet the expected standards, drying shrinkage met the requirements, compressibility was acceptable (below 21% as per reference), and moisture content was slightly above the recommended limit.

In detail, the angle of repose for Microcrystalline Cellulose Ketapang Leaves (MCCKL) and commercial Avicel PH 102 were 30.60° and 29.15°, respectively. Flow rates were 0.48 g/s for Microcrystalline Cellulose Ketapang Leaves (MCCKL) and 0.88 g/s for Avicel PH 102. Both flow rates are within acceptable limits since 100 g of powder flowed in less than 10 sec. Moisture content was determined by weighing 1 g of Microcrystalline Cellulose Ketapang Leaves (MCCKL) powder and drying it at 105 °C for 30 min until a constant weight was achieved, resulting in an average moisture content of 5.13%, compared to 5.08% for Avicel PH 102. These values exceed the acceptable moisture content of less than 5%, indicating room for improvement. The drying shrinkage of Avicel PH 102 was less than 7%, and compressibility values were 20% for Microcrystalline Cellulose Ketapang Leaves (MCCKL) and 21% for Avicel PH 102, both meeting the qualification criteria.

Based on these results, Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) derived from ketapang leaves shows potential as a raw material for tablet production, given that several key parameters align with those of commercial Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) (Avicel PH 102).

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy analysis further supported this potential. The Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectrum of Microcrystalline Cellulose Ketapang Leaves (MCCKL) closely resembled that of commercial Avicel Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC), revealing characteristic functional groups. A broad band at approximately 3500 cm⁻¹ corresponds to hydroxyl (OH) groups. Peaks at 2895.25 cm⁻¹ indicate aliphatic C–H bonds, while 1647.26 cm⁻¹ represents CH₂ deformation vibrations. The glycosidic C–O–C linkages are observed at 1419.66 cm⁻¹, and the β-glycosidic bonds appear at 898.86 cm⁻¹.

Literature reports for Avicel identify cellulose vibration peaks as follows: 3445 cm⁻¹ (intramolecular OH stretching and hydrogen bonding), 2898 cm⁻¹ (CH and CH₂ stretching), 1650 cm⁻¹ (absorbed water OH bending), 1430 cm⁻¹ (CH₂ symmetrical bending), 1375 cm⁻¹ (CH bending), 1330 cm⁻¹ (OH plane bending), 1161 cm⁻¹ (asymmetric C–O–C stretching), 1061 cm⁻¹ (C–O–C stretching), and 898 cm⁻¹ (asymmetric vibration of C1 β-glycosidic linkages) [21].

Fig. 3: (a) Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) test results of microcrystalline cellulose ketapang leaves (MCCKL); (b) Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) test results of avicel PH 102

Table 5: Comparison of microcrystalline cellulose ketapang leaves (MCCKL) and Avicel PH 102 functional groups

| Functional groups | Microcrystalline cellulose ketapang leaves (MCCKL) (/cm) | Avicel PH 102 (/cm) |

| -OH | 3324.45 | 3333.01 |

| C-H Stretching | 2906.30 | 2901.65 |

| OH from absorbed water | 1633.44 | 1639.61 |

| C-OH, C-H, CH2 | 1373.62 | 1315.64 |

| C-O-C asymmetric | 1156.79 | 1160.48 |

| β-glycoside | 894.05 | 896.71 |

Based on the Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) analysis, Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) derived from ketapang leaves exhibits properties similar to those of commercial Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) (Avicel PH 102). The infrared spectrum reveals several characteristic functional groups. For instance, a broad band at around 3500 cm⁻¹ indicates the presence of hydroxyl (OH) groups. The aliphatic C–H bonds appear at 2895.25 cm⁻¹, while CH₂ deformation vibrations are observed at 1647.26 cm⁻¹. The band at 1419.66 cm⁻¹ corresponds to glycosidic C–O–C linkages, and the β-glycosidic bonds are indicated by the band at 898.86 cm⁻¹.

The Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) spectrum from ketapang leaves closely matches the commercial Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) spectrum in key regions such as 3400 cm⁻¹ (OH), 2900 cm⁻¹ (C–H), and 1050 cm⁻¹ (C–O–C), confirming that the chemical structure of ketapang leaf Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) is comparable to the standard. Consequently, the Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) obtained from ketapang leaves can be considered equivalent in purity and functional characteristics for various industrial applications.

According to Effendi et al. (2018) [20], Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectrum analysis confirms that the produced Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) is a pure cellulose compound. Their study showed a decrease in absorbance at 3375.43 cm⁻¹ and 2899.01 cm⁻¹, indicating a reduction in C–H and O–H stretching vibrations, which suggests an increase in crystalline regions within the MCC. Similarly, the Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) from ketapang leaves showed C–H stretching at 2906.30 cm⁻¹ and O–H stretching at 3324.45 cm⁻¹, supporting the conclusion of enhanced crystallinity.

In tablet formulation, this increased crystallinity generally strengthens the tablets but may negatively affect powder flowability and slow disintegration. However, such characteristics are advantageous for direct compression tablet manufacturing.

The compressibility test of ketapang leaf Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) powder yielded a value below 21%, indicating good powder flow consistent with the flow rate test results. Nawangsari et al. (2018) [22] stated that the flowability of Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) in tablet presses is influenced by compressibility, Hausner ratio, and angle of repose. A compressibility value greater than 21% indicates poor flow properties due to high powder density, which hampers flow rate. Since the compressibility of ketapang leaf Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) is below 21%, it exhibits good flowability, aligning with the characterization findings.

According to the literature, Avicel exhibits characteristic cellulose vibration peaks in the Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectrum as follows: 3445 cm⁻¹, corresponding to intramolecular OH stretching including hydrogen bonding; 2898 cm⁻¹, associated with CH and CH₂ stretching; 1650 cm⁻¹, due to OH groups from absorbed water; 1430 cm⁻¹, resulting from symmetrical CH₂ bending; 1375 cm⁻¹, from CH bending; 1330 cm⁻¹, attributed to OH plane bending; 1161 cm⁻¹, caused by asymmetric C–O–C stretching; 1061 cm⁻¹, due to symmetric C–O–C stretching; and 898 cm⁻¹, corresponding to asymmetric vibration (rocking) of the C1 β-glycosidic linkage out of the stretching plane [23].

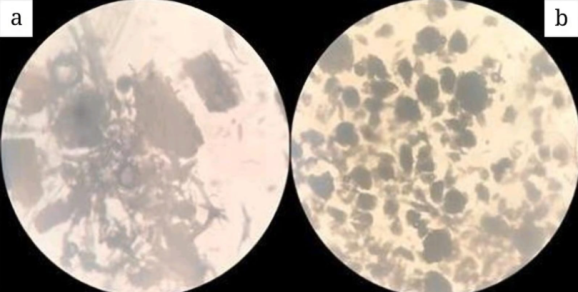

Microscopic analysis is used to confirm the sample’s identity by examining and recognizing specific morphological features of the plant fragments [9]. In this study, Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) was observed under 10x magnification to compare the shape and structure of cellulose fibers between the Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) from ketapang leaves and the commercial standard, Avicel PH 102.

Fig. 4: (a) Microcrystalline cellulose ketapang leaves (MCCKL) microscopic test results using magnification scale 10x; (b) Avicel PH 102 microscopic test results using magnification scale 10x

Microscopic examination revealed differences in the shape of cellulose fibers between Microcrystalline Cellulose Ketapang Leaves (MCCKL) and Avicel PH 102. The cellulose fibers of Avicel PH 102 are generally round, whereas those of Microcrystalline Cellulose Ketapang Leaves (MCCKL) are longer, larger, and exhibit more variability in shape. The size and morphology of the cellulose fibers influence the crystallinity of Microcrystalline Cellulose Ketapang Leaves (MCCKL). Despite having lower crystallinity, Microcrystalline Cellulose Ketapang Leaves (MCCKL) can still be produced from these larger cellulose fibers.

CONCLUSION

This study utilized ketapang leaves (Terminalia catappa L.) to produce Microcrystalline Cellulose Ketapang Leaves (MCCKL). The yield of Microcrystalline Cellulose Ketapang Leaves (MCCKL) was 83.70% following the extraction of 24.13% α-cellulose from the ketapang leaves. Characterization of the Microcrystalline Cellulose Ketapang Leaves (MCCKL powder including color, organoleptic properties, solubility, and pH exhibit close similarities to commercial Avicel PH 102. Key parameters included a melting point of 256 °C, angle of repose of 30.60°, flow rate of 0.48 g/s, drying shrinkage of 4%, compressibility of 21%, and moisture content of 5.13%. Based on these findings, the properties of Microcrystalline Cellulose Ketapang Leaves (MCCKL) powder are comparable to those of commercial Avicel PH 102. Furthermore, Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) analysis indicated that the C–H and O–H functional groups present in Microcrystalline Cellulose Ketapang Leaves (MCCKL) exhibit absorbance characteristics suitable for use as fillers in tablet manufacturing by direct compression, attributed to their high crystallinity.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We would like to express our gratitude to the Directorate General of Learning and Student Affairs, Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology, for providing the opportunity and funding through the Student Creativity Program Article Scientific (AI). We also thank Universitas Muhammadiyah Banjarmasin for their guidance and support throughout the research process.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Y. conducted data analysis, extraction processes, and prepared manuscript drafts. M. handled the preparation of extract residue powder and α-cellulose isolation from ketapang leaves. F. produced the Microcrystalline Cellulose from Ketapang Leaves (MCCKL). N. M. performed qualitative tests on Microcrystalline Cellulose from Ketapang Leaves (MCCKL), including organoleptic, microscopic, identification (color and odor), and Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) analysis. R. L. carried out solubility, pH, and physical property tests, as well as characterization of Microcrystalline Cellulose from Ketapang Leaves (MCCKL) powder. Y. P. I. L. provided research direction, experimental design, and manuscript supervision.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The author declares no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

Nawangsari D. Isolasi dan karakterisasi selulosa mikrokristal dari ampas tebu (Saccharum officinarum L.). Pharmacon. 2019;16(2):67-72. doi: 10.23917/pharmacon.v16i2.9150.

Visca R, Nurjanah S, Yuliana N. Study of characterization of skin-based cellulose microcrystalline (Artocarpus altilis) through the hydrolysis process. Technology. 2020;8(1):11-21.

Samran N, Khairiah U. Variation of hydrolysis time at 80 °C on the yield of microcrystalline cellulose from soybean rind (Glycine max L.) Merril. J Res Math Educ. 2018;3(1):1.

Kholisoh I, Darojjah Z, Firmania E, Natijah H, Hartati I. Effect of cooking time and microwave-assisted acetic acid ratio on the organosolv pulping process of bagasse (Saccharum officinarum L.). Natl Sci Technol Proc. 2016;1(1):28-32.

Triana E, Nurhidayat N. The assessment of ketapang (Terminalia catappa L.) leaves water extract as a natural cleaning agent using the clean-in-place (CIP) method. Chemistry. 2016;3(1):143-55.

Herli MA, Wardaniati I. Phytochemical screening of ethanol extract and fraction of ketapang leaves growing around Univ. Abdurrab Pekanbaru. J Pharm Sci (JOPS). 2019;2(2):38-42.

Sukma AA, Bahri S, Aman. Thermal conversion of ketapang wood (Terminalia catappa L.) into bio-oil by pyrolysis technology using NiMo/NZA catalysts. Studies. 2019;1(1):1-14.

Yuniarti PS, Bayu HT. A kinetics review of the pyrolysis reaction of ketapang seed shells to produce charcoal briquette fuel. Yogyakarta: Gadjah Mada University; 2016.

Lestari YP, Patimah R, Yuspa, Muhammad HR, Aldeina S, Mursyidah S. Processing pharmaceutical grade microcrystalline cellulose from some parts of the white lotus plant (Nymphaea nuchal Burm. F.): preparation andqualitative powder tests. Pharm Pharmacol Mag. 2023;27(3):119-24.

Suryadi H, Indah Lestari YP, Mirajunnisa YA, Yanuar A. Potential of cellulose of chaetomium globosum for preparation and characterization of microcrystalline cellulose from water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes). Int J Appl Pharm. 2019;11(4):140-6. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2019v11i4.31081.

Lestari YP. Optimization of HCl concentration in the hydrolysis process for manufacturing cellulose microcrystalline from hyacinths (Eichhornia crassipes). J Innov Res Knowl. 2022;1(10):1335-44.

Lestari YP, Patimah R, Muthaharah M, Miranti RM, Mulyani T, Purwanto A. Antioxidant activity test on ethanol extract 70% white lotus plant (Nymphaea nouchali L). J Innov Res Knowl. 2023;3(4):1-8.

Falya LY Y, Chasanah U, Kusomo DW, Bethasari M. Α cellulose isolation manufacture and characterization of cellulose microcrystalline from baby orange peel waste (Citrus sinensis). Pharm Pharmacol Mag. 2022;26(3):119-23.

Rowe RC, Sheskey PJ, Quinn ME. Handbook of pharmaceutical excipients. 6th ed. London: Pharmaceutical Press American Pharmacists Association; 2009.

Ningsi S, Iklasita N, Wahyuddin M, Syakri S. Characterization of cellulose microcrystalline from glutinous corn husks (Zea mays l var certain rules). Health. 2020:53-9.

Widia I, Wathoni N. Review of microcrystalline cellulose articles: isolation characterization and pharmaceutical applications. J Pharmacol. 2018;15(2):127-43.

Rachmawaty R, Meriyani M, Priyanto S. Synthesis of cellulose diacetate from hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) and its potential for membrane manufacturing. J Chem Ind Technol. 2013;2(3):8-16.

Edison E, Diharmi A, Sari ED. Characteristic of microcrystalline cellulose from red seaweed eucheuma cottonii. Jurnal PHPI. 2019;22(3):483-9. doi: 10.17844/jphpi.v22i3.28946.

Lestari YP, Suryadi H, Mirajunnisa MW, Mangunwardoyo W, Sutriyo, Yanuar A. Characterization of kapok pericarpium microcrystalline cellulose produced of enzymatic hydrolysis using purified cellulase from termite (Macrotermes Gilvus). Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2020;2(3):7-14. doi: 10.22159/ijpps.2020v12i3.36468.

Effendi E, Elvia R, Amir H. Preparation and characterization of microcrystalline cellulose made from empty oil palm bunches. J Educ Chem Sci. 2018;2(1):52-7.

Rojas J, Lopez A, Guisao S, Ortiz C. Evaluation of several microcrystalline celluloses obtained from agricultural by products. J Adv Pharm Technol Res. 2011;2(3):144-50. doi: 10.4103/2231-4040.85527, PMID 22171310.

Nawangsari D, Yohana Chaerunisaa AY, Abdassah M, Sriwidodo S, Rusdiana T, Apriyanti L. Isolation and phisicochemical characterization of microcristalline cellulose from ramie (Boehmeria nivea l. gaud) based on pharmaceutical grade quality. Indonesian J Pharm Sci Technol. 2018;5(2):55-61. doi: 10.24198/ijpst.v5i3.15040.

Suryadi H, Sutriyo M, Junnisa M, Lestari YP. Potential of cellulase of penicillium vermiculatum for preparation and characterization of microcrystalline cellulose produced from α-cellulose of kapok pericarpium (Ceiba pentandra). Int J Appl Pharm. 2019;11(4):92-7. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2019v11i4.31094.