Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 6, 2025, 49-56Reviewl Article

NANOTECHNOLOGY IN PAEDIATRIC DRUG DELIVERY: ADVANCES, CHALLENGES, AND REGULATORY CONSIDERATIONS-A REVIEW

GOWTHAM ANGAMUTHU1, GIRIDHARA MAHADEVSAMY2, GURUBARAN SIVANATHAN2, SANJAI RAJAGOPAL2, NAGASAMY VENKATESH DHANDAPANI*

1Department of Pharmaceutical Regulatory Affairs, JSS College of Pharmacy (JSS Academy of Higher Education and Research, Mysuru), Ooty - 643 001. The Nilgiris, Tamil Nadu, India. 2Department of Pharmaceutics, JSS College of Pharmacy (JSS Academy of Higher Education and Research, Mysuru), Ooty - 643 001. The Nilgiris, Tamil Nadu, India.*Department of Pharmaceutics, JSS College of Pharmacy (JSS Academy of Higher Education and Research, Mysuru), Ooty - 643 001. The Nilgiris, Tamil Nadu, India.

*Corresponding author: Nagasamy Venkatesh Dhandapani; *Email: nagasamyvenkatesh@jssuni.edu.in

Received: 27 Feb 2025, Revised and Accepted: 09 Aug 2025

ABSTRACT

Children's growth and physiology are basically different from that of adults, so paediatric pharmacotherapy is dissimilar in challenge. The traditional formulations of medicines are not suitable for children, as they face issues of poor taste, insusceptibility of dosage flexibility, and potential miscalculation of dosage. Nanotechnology of nanoscale dimensions holds great promise in solving paediatric drug delivery issues. In this article, the prospect of nanocarriers, such as liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles, and solid lipid nanoparticles, is discussed in paediatric medicine. Nanoformulations have been found to increase oral bioavailability by 60% and decrease dosing frequency by 50%, with improved therapeutic response in paediatric patients. Today, at least four FDA-approved nanoformulations are on the market for paediatric applications, such as liposomal amphotericin B for fungal infections and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin for paediatric oncology, showing the increasing clinical use of nanotechnology in paediatric medicine. However, there are huge challenges remaining: long-term safety of nanomaterials in developing organisms, scalable manufacturing, regulatory hurdles, and ethical considerations for paediatric clinical trials. The review will highlight the continued need for interdisciplinarity to overcome the challenges and reach the potential of nanotechnology for enhancing paediatric health outcomes. Future directions include stimuli-responsive and personalized nanocarriers, combination therapy, and theranostic nanoparticles. With further research and development, nanotechnology can potentially revolutionize paediatric pharmacotherapy with more effective, safer, and patient-compliant drug delivery.

Keywords: Nanotechnology, Paediatric drug delivery, Nanocarriers, Liposomes, Polymeric nanoparticles, Solid lipid nanoparticles, Paediatric pharmacotherapy, Controlled release, Targeted drug delivery and Nanomedicine applications

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i6.54077 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Paediatric pharmacotherapy is accompanied by challenges, which for decades confounded healthcare providers and drug researchers. Paediatric and adult population physiologic and developmental distinctions require unique drug formulation and delivery strategies [1]. Children are not 'little adults'; they have different pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic characteristics that may greatly affect the efficacy and safety of drugs. For instance, neonates and infants have undeveloped liver enzymes, diminished renal clearance, and varying rates of drug metabolism, which affect drug absorption and elimination kinetics [2]. These variations are particularly evident in neonates and infants, whose immature organ systems and fluctuating body compositions can significantly modify drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion [3].

Standard drug products are not suitable for paediatric application due to their properties, viz poor palatability, inflexibility in dose, and difficulty in measuring adequate and exact dosing. All these factors contribute to non-adherence to therapy, which ultimately results in less optimal therapeutic effects. Moreover, a dose reduction from the adult to paediatric dose suffers with erroneous dose and bioavailability and is exposed to safety risk [4]. Under these circumstances, nanotechnology provides a solution by offering pediatric-friendly formulations with enhanced solubility, targeted delivery, and controlled release to overcome these pharmacotherapy challenges better [5].

Over the last two decades, nanotechnology has emerged as one of the new promising frontiers to address long-standing issues in paediatric drug delivery. Nanoformulations, by definition, possess at least one dimension between 1-100 nm; such particles can have properties that are novel for exploitation to enhance drug delivery in children [6]. Nanoscale systems enhance drug solubility, enhance permeability across biological barriers, and offer the vehicle for targeted delivery to specific tissues or organs [7].

The advantages nanotechnology would offer to paediatric preparation is numerous. Nanocarriers can enhance the drug's poor solubility universal issue with paediatric pharmacotherapy since oral liquids are prevalent [8]. They would also facilitate control release profiles; this would mean reduced dosing frequency and increased patient compliance [9]. Moreover, nanoformulations can provide the potential for new drug delivery routes-like transdermal and pulmonary delivery-in a way potentially favourable to children [10].

But the application of nanotechnology in paediatric medicine is not without its challenges. The long-term safety of nanomaterials in developing organisms is a critical area of research [11]. Regulatory frameworks for nanomedicines, particularly for paediatric applications, are in development [12]. In addition, scalability and cost-effectiveness of nanoformulations are challenges to the large-scale clinical application of nanoformulations. Nanotechnology drug delivery systems have an added benefit in paediatric pharmacotherapy because they can promote bioavailability, allow targeted delivery, and lower systemic toxicity. For example, liposomal carriers can be used to encapsulate cytotoxic drugs, minimizing off-target toxicities in paediatric oncology. Likewise, polymeric nanoparticles can be made to release the drug in a controlled manner, minimizing the frequency of dosing and maximizing compliance in patients—essential elements in compliance in paediatric treatment [13].

This review aims to offer a comprehensive overview of the current situation of nanotechnology in paediatric drug delivery. It will compare different types of nanocarrier systems and their application in paediatric medicine, outline the regulatory climate, and examine the challenges and prospects of this rapidly evolving area. Synthesizing the latest research and clinical data will allow us to gain a clearer understanding of the ability of nanotechnology to revolutionize paediatric pharmacotherapy and promote health outcomes among children.

The selections of articles for the present review were searched from specialized databases (Range of years: 2014-2024) such as Elsevier, PUBMED, and Cambridge using the keywords Nanotechnology, paediatric drug delivery, nanocarriers, liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles, solid lipid nanoparticles, paediatric pharmacotherapy, controlled release, targeted drug delivery and nanomedicine applications. Other selections include articles from Springer, and Wiley, information from Internet sources, and online-published articles from The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, Medscape, and Statpearls.

Nanocarrier systems in paediatric formulations

Nanocarrier systems are a promising field of research towards overcoming the challenges of drug delivery in paediatric patients. The nano-carriers contain various benefits concerning the enhancement of bioavailability, site-specific drug delivery, and reduced dosing cycles. In the next section, we will discuss three major types of nanocarriers that hold promise in paediatric formulation, namely liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles, and solid lipid nanoparticles.

Table 1: Comparative physicochemical properties, stability, and clinical applications of nanocarriers in paediatric drug delivery

| Nanocarrier type | Physicochemical properties | Stability | Advantages in paediatrics | Clinical applications | References |

| Liposomes | Size: 50–200 nm Amphiphilic structure | Moderate stability | Reduced toxicity, enhanced bioavailability | Liposomal amphotericin B for fungal infections | 14 |

| Polymeric nanoparticles | Size: 10–1000 nm Hydrophobic/hydrophilic core | High stability | Controlled drug release, surface functionalization (e. g., PEGylation) | Paediatric oncology (targeted chemotherapy) | 19 |

| Solid Lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) | Size: 50–400 nm Lipid-based matrix | Excellent stability | Long-term stability, controlled release | Topical paediatric formulations (e. g., anti-inflammatory drugs) | 20 |

Liposomes

Liposomes are round vesicles made up of one or more phospholipid bilayers which contain an aqueous interior. Their unique structure enables the encapsulation of hydrophilic or hydrophobic drugs, making them extremely versatile carriers for therapeutic compounds in their numerous applications [14].

In paediatric application, liposomes have the potential to enhance drug delivery with decreased toxicity. For example, a study in 2015 by Ladavière and Gref demonstrated that liposomal preparations of amphotericin B minimized nephrotoxicity in children infected with fungi, thus enabling higher doses and improved therapeutic response [15]. This is extremely critical in paediatric patients where organ toxicity has long-term developmental implications.

Another important use is in the treatment of paediatric cancers. Liposomal doxorubicin has been investigated to reduce cardiotoxicity, a great concern in children who undergo anthracycline chemotherapy. In children with relapsed or refractory solid tumours, a phase I trial by Völler et al. (2015) concluded that liposomal doxorubicin had an acceptable toxicity profile versus standard formulations [16].

Liposomes have also been explored for vaccine delivery in paediatric populations. Schwendener (2014) discussed the application of liposomes as adjuvants and delivery vehicles for vaccines, noting their potential to improve immune responses and possibly decrease the number of doses for immunization [17]. This may be very useful in enhancing vaccination compliance among paediatric patients.

Polymeric nanoparticles

Solid colloidal particles of biodegradable or biocompatible polymers with sizes ranging from 10-1000 nm are polymeric nanoparticles. Effective encapsulation, along with controlled release properties, positions polymeric nanoparticles as good candidates for drug targeting. Their surfaces can be modified using biocompatible polymers, like polyethene glycol (PEGylation), in order to increase the circulation lifetime, decrease immunogenicity, and enhance the capability of targeting in paediatric preparations. For instance, PEGylated polymeric nanoparticles have demonstrated enhanced blood circulation and decreased renal clearance, making them well-suited for long-term paediatric cancer treatment [18].

Polymeric nanoparticles have been investigated in paediatric oral drug delivery and targeted cancer therapy in paediatric cancers. Yadav et al. (2019) published a review of polymeric nanoparticles in paediatric drug delivery wherein they hold promise in improving poor water-solubility drugs oral bioavailability, as well as sustained release formulation [19].

Solid lipid nanoparticles

SLNs are colloidal carriers that are made up of physiological lipids, which are usually solid at room and body temperatures. Such nanocarriers can have numerous benefits, such as a high drug-loading capacity, enhancement of the stability of entrapped drugs, and the ability for controlled release [20].

SLNs have been known to enhance the oral bioavailability of highly water-insoluble drugs and to provide long-lasting release preparations in paediatric drugs. Pinto and Müller (1999) were the pioneers to suggest the use of SLNs in children, highlighting the role of the latter in enhancing the palatability of oral preparations and also imparting control release characteristics [21].

Also, SLNs have promising applications in paediatrics in topical drugs. Jain et al. (2017) formulated aceclofenac SLN-based gel for the topical administration of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Their research revealed that higher skin permeation and greater anti-inflammatory action happen with SLN compared to conventional gels [22].

Applications in paediatric medicine

The use of nanotechnology in paediatrics crosses a broad spectrum of therapeutic fields. This chapter will discuss in some detail three major areas in which nanoformulations have indicated specific potential: cancer treatment, respiratory diseases, and infectious diseases.

Table 2: Clinical applications of nanocarriers in paediatric medicine

| Drug/Nanocarrier | Type | Paediatric indication | Clinical outcomes | References |

| Liposomal Amphotericin B (Ambisome) | Liposome | Fungal infections | Improved efficacy, reduced nephrotoxicity | 30 |

| Doxorubicin (Doxil) | Liposome | Paediatric oncology | Reduced cardiotoxicity, enhanced targeting | 23 |

| Efavirenz-loaded SLNs | Solid Lipid Nanoparticle | Paediatric HIV therapy | Enhanced bioavailability, reduced dosing | 30 |

| Polymeric Micelles (Paclitaxel) | Polymeric Micelles | Paediatric tumours | Increased drug accumulation at tumor sites | 61 |

Cancer therapy

Children's cancers are particular challenges because treatment may have lasting effects on development and growth. Nanoformulations hold the promise of more localized therapies with decreased systemic toxicity, an important issue in paediatric oncology. One of the most well-studied paediatric cancer nanoformulations is liposomal doxorubicin. Doxorubicin is an anthracycline antibiotic that is a standard treatment for many paediatric solid tumours and hematologic malignancies. It is, however, dose-limited by cardiotoxicity, which is a special concern in children [23]. Doxorubicin's pharmacokinetics have been changed by liposomal encapsulation, with a theoretical reduction in cardiotoxicity and a preservation of activity. A phase I trial by Dorr et al. (2007) studied pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in children with relapsed or refractory solid tumours. It proved that liposomal formulation could accommodate greater doses of doxorubicin on a cumulative scale with reduced cardiotoxicity over standard formulations [24]. Another possible application of nanotechnology in paediatric oncology is brain tumours. A primary obstacle to drug delivery for CNS tumours is the blood-brain barrier (BBB). Polymeric nanoparticles have been examined as a tool for enhancing the penetration of drugs across the BBB. Zhao et al. (2018) demonstrated in a study that transferrin-conjugated docetaxel-loaded PLGA nanoparticles exhibited improved penetration across BBB and enhanced antitumor activity in a mouse model of glioblastoma [25]. Nanocarriers have exhibited a piovital role in the biological applications, especially in the field of cancer drug targeting. These drug delivery systems have demonstrated a significant improvement with reference to its drug efficacy, enhanced circulation time and controlled and targeted drug release over the conventional treatment regime [26].

Respiratory diseases

The advantages of nanotechnology for the treatment of respiratory diseases in children are enhancing drug delivery to the lungs and increasing the efficacy of inhaled therapy.

Inhalation is one of the most prevalent chronic childhood illnesses: asthma. Traditional inhaled corticosteroids have demonstrated their effectiveness; however, they tend to be marred by inefficient lung deposition and fast clearance. Nanocarriers have the possibility of improving these limitations.

The efficacy of chitosan nanoparticles as a carrier in pulmonary delivery for theophylline in treating asthma was tested by Nafee et al. (2014). Improved lung deposition with sustained release and reduced systemic bioavailability was exhibited by the nanoformulation, as compared to conventional formulations. In vivo rat studies showed more pronounced bronchodilation effects; thus, such a formulation is worth considering for the management of asthma in paediatric patients [27].

Another area of interest is the treatment of cystic fibrosis, a genetic disorder that affects the lungs and other organs. Effective delivery of antibiotics to combat chronic lung infections is critical in CF management. Cipolla et al. (2016) developed a liposomal formulation of amikacin for inhalation in CF patients. Their phase II clinical trial in paediatric and adult CF patients demonstrated improved lung function and reduced bacterial density compared to placebo, with a favourable safety profile [28].

Nanocarriers have also been quite promising in the delivery of vaccines against respiratory infections. Recently, Kunda et al. (2013) reported on the formulation of pneumococcal vaccines in the form of dry powder inhalers using PGA-co-PDL nanoparticles [29]. The nanoformulation proved to be more stable and immunogenic compared to liquid formulations and thus promises to allow needle-free vaccination for paediatric populations.

Infectious diseases

Nanotechnology may revolutionize the treatment of infectious diseases in paediatric patients, with the improved efficacy of antimicrobial agents and overcoming drug resistance mechanisms. Nanoantibiotics present a major benefit in the fight against bacterial resistance mechanisms, especially in paediatric infections. Nanocarriers are promising in drug delivery as they circumvent bacterial efflux pumps, minimize enzymatic degradation, and enhance intracellular drug levels. PLGA nanoparticles with encapsulated gentamicin, for instance, have shown enhanced intracellular penetration and sustained release, which was able to completely eradicate Brucella melitensis from macrophages. This improved bioavailability decreases the dose of required antibiotic and diminishes toxicity and is most especially beneficial for use in bacterial infection in paediatric populations where dosage accuracy and safety are of foremost concern. Further, rifampicin-lipid nanoparticles have demonstrated augmented effectiveness against drug-resistant (MDR) Mycobacterium tuberculosis through precluding efflux-driven resistance with prospects for uses in the paediatric therapy of tuberculosis.

Of utmost research, areas include the development of nanocarriers in antibiotic delivery. An example was seen in Lecaroz et al.'s (2007) report in which PLGA nanoparticles of gentamicin are used as nanoformulations to treat brucellosis. Results in the in vitro model indicate intracellular penetration as well as potent antimicrobial activity against Brucella melitensis with such nanoformulations, where an application has also been mentioned to paediatric patients affected by intracellular bacterial infection [30].

Nanoformulations also have been demonstrated to be of promise in the treatment of viral infections. Mahajan et al. (2012) developed efavirenz-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles for enhanced oral bioavailability in paediatric HIV treatment. Their in vivo studies in rats showed significantly higher plasma concentrations and improved pharmacokinetic profiles compared with the free drug, suggesting the possibility of a reduced dose and better therapeutic results in paediatric HIV patients. In the clinical setting, nanoformulations have shown enhanced performance in paediatric infectious diseases. For instance, liposomal amphotericin B, an FDA-approved drug, is extensively applied to children suffering from systemic fungal infections and has proven to be more efficacious and less toxic than traditional amphotericin B. Such clinical uses exemplify the developing role of nanomedicine in the management of paediatric infectious diseases, from preclinical promise to real-world application [31].

There's another thrilling field of nanotechnology in paediatric infectious disease: application in vaccine delivery. Nanoparticles can behave as delivery vehicle and adjuvants possibly enhancing immune response and lowering the dose number required to immunize, as exemplified in a study by Dhakal et al., 2018, developing the nanoparticle-based intranasal vaccine for a major cause of respiratory illness of infants: Respiratory Syncytial Virus. The nanoformulation caused strong mucosal and systemic immunity in mice, thereby suggesting a potential for needle-free RSV vaccination of paediatric populations [32].

In conclusion, nanotechnology holds promise for a range of applications in paediatric medicine, from cancer therapy to respiratory and infectious diseases. The nanoformulations may be used to enhance drug delivery and therapeutic effect with reduced side effects in paediatric patients. Further studies, such as large-scale clinical trials, will be required to establish the safety and efficacy of nanoformulations in paediatric patients.

Regulatory considerations

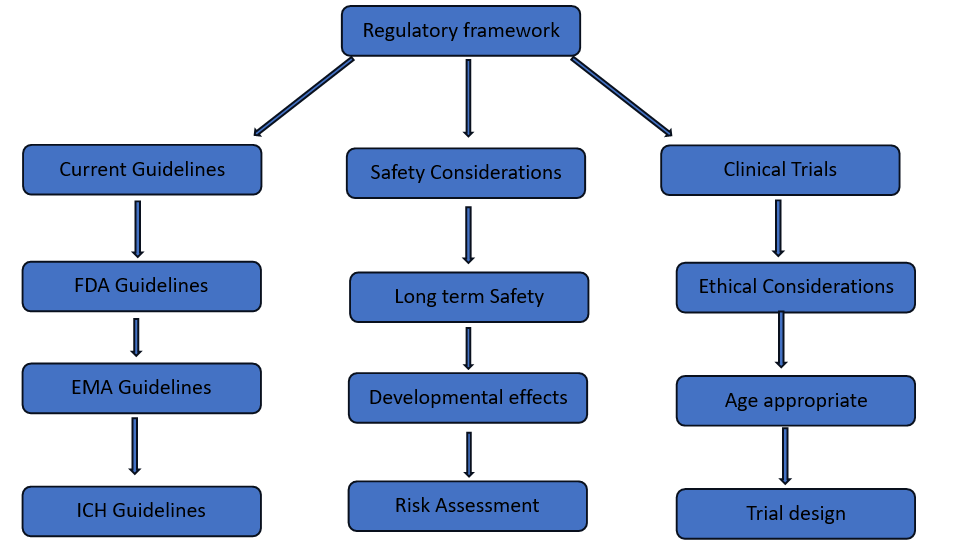

Paediatric formulations are being made and approved that are nanoformulations, but that also impose specific regulatory complexities. Those range from the complexities of nanomaterials themselves, special precautions for paediatric age groups, to an ever-developing regulatory paradigm in terms of nanotechnology-based medicine. That is what the current regulatory model looks like now, and the following considerations for how the regulatory void might be fulfilled are special thoughts for paediatric-specific nanoformulations. Regulatory frameworks for paediatric nanomedicines vary significantly across regions, with the FDA, EMA, and ICH adopting distinct approaches. The FDA’s 2017 guidance on nanomaterials emphasizes a product-specific, risk-based assessment, focusing on physicochemical characterization, biological interactions, and long-term safety. In contrast, the EMA employs a more comprehensive risk assessment framework, incorporating both product-specific and general safety evaluations, including immunotoxicity and long-term biocompatibility considerations. The EMA's reflection paper on intravenous liposomal products (2013) highlights the need for enhanced pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic modelling in paediatric trials, which is less explicitly detailed in the FDA guidance. The ICH guidelines, particularly ICH E11 (clinical investigation of medicinal products in the paediatric population), provide a globally harmonized framework for paediatric drug development. The ICH approach promotes the use of age-appropriate formulations, pharmacokinetic modelling, and adaptive trial designs, influencing both FDA and EMA paediatric regulatory standards. However, nanomedicine-specific regulations remain fragmented, with no unified international guidelines, highlighting the need for further harmonization in paediatric nanomedicine regulation.

Fig. 1: Regulatory framework for clinical trials and safety guidelines

Current regulatory framework

Regulatory agencies across the world, including the U. S. Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency, have recognized an imperative for specific guidance on nanomedicine development and assessment. Yet to date, nanomedicines do not have a distinct path for regulation but are typically incorporated into current drugs, biologics, or medical devices regulatory systems [33].

FDA has released a series of guidance reports on nanotechnology in drug products. In 2017, the FDA published a draft guidance titled "Drug Products, Including Biological Products, that Contain Nanomaterials," which details the agency's current thinking on the development of drug products containing nanomaterials [34]. This guidance highlights a risk-based approach to evaluating nanomedicines, including material properties, biological interactions, and desired use.

Similarly, the EMA has published reflection documents on nanomedicine production, with specific regards to intravenous liposomal and block copolymer micelle products [35]. The reports provide information on the quality, safety, and efficacy aspects of nanomedicines, commenting on the need for unique characterization techniques and safety assessments.

Paediatric-specific regulatory considerations

Additional regulatory requirements also exist for paediatric formulations. PREA in the United States mandates that pharmaceutical firms determine the safety and efficacy of new drugs and biologics in paediatric populations [36]. The Paediatric Regulation was established by the European Union to make available and develop medicines for children [37]. The regulatory agencies recommend the following parameters as mandate conditons for the administration of nanoformulations in case of paediatrics patients such as formulations and dosage form appropriate to age of the paediatric, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies to be conducted in all paediatric age groups, establishing long-term safety, including the potential impact on growth and development and final ethical considerations in the design of clinical trials for paediatric populations.

The regulatory issues in the development of nanomedicines for paediatric applications have been recently discussed by Germain et al. (2020), calling for standardized protocols in safety evaluation, paediatric pharmacokinetic modelling, and age-related clinical trials. It was noted that there is a need to harmonize definitions of nanomedicines by different regulatory agencies and further development of a paediatric investigation plan in earlier stages of drug development [38].

Safety considerations and risk assessment

In paediatric populations, nanoformulations require very special attention due to their potential long-term effects during growth and development. Preclinical studies are usually extensive and usually required by regulators before clinical trials can proceed in paediatric populations.

A review by Tinkle et al. (2014) presented the safety considerations for nanomedicines in paediatric populations. They referred to the necessity of specific toxicology studies to assess the developmental toxicity, immunotoxicity, and genotoxicity of nanoformulations [39]. The authors also called attention to the point that nanoparticles' biodistribution and clearance would be crucially different in developing organisms from their adult counterparts.

The FDA guidelines on nanomaterials in drug products are to be evaluated using a risk-based approach toward safety assessment. The considerations include, physicochemical characteristics of the nanomaterial, the possibility of changed biodistribution relative to traditional formulations, the possibility of long-term tissue accumulation, immunological impact of the nanomaterial and finally the possibility of developmental toxicity in paediatric populations.

Challenges in clinical trial design

It is difficult to plan clinical trials on nanoformulations in paediatric groups. Ethical implications, endpoints appropriate for the age group, and long-term follow-up are some of the foremost concerns that must be taken into account.

A review by Riehemann et al. (2018) addressed issues of clinical translation of nanomedicines, including considerations for paediatric trials. In this context, authors discussed novel trial designs such as adaptive trials and basket trials that can assess nanoformulations for multiple paediatric indications cost-effectively [40].

The ICH has provided general guidelines for the clinical investigation of medicinal products in children (ICH E11). In the context of nanomedicine, such ICH guidelines that are generally provided for any formulation are essential points to be addressed in paediatric trials [41].

Efforts to address regulatory gaps

Given an appreciation of the need for more details about nanomedicines in children, several initiatives have been established to fill regulatory gaps:

1. The FDA's Nanotechnology Task Force was established to develop science-based approaches for nanomaterials in FDA-regulated products [42].

2. The European Technology Platform on Nanomedicine (ETPN) created a working group on regulatory issues to have a platform for dialogue between industry, researchers, and regulators [43].

3. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has launched several programs to establish internationally harmonized guidelines for testing risks of nanomaterials [44].

A review by Tinkle et al. in 2014 summarized the scientific and regulatory gaps in nanomedicine development. They underlined the importance of collaboration between researchers, industry, and regulators to start formulating appropriate regulatory frameworks for nanomedicines with certain prospects for paediatric use.

In summary, regulatory environments for nanoformulations of paediatric medicine are still highly complex and constantly evolving. While current regulatory schemes offer a broad platform for the evaluation of nanomedicines, considerable space is left for a more focused body of guidelines, particularly for paediatric indications. Harmonized approaches to gap-filling and delivering regulatory convergence across different areas will go far toward making safe and effective nanoformulations for paediatric indications a reality.

Challenges and future perspectives

Although nanotechnology holds a lot of promise in enhancing paediatric drug formulations, numerous challenges need to be addressed to achieve its full potential. This section discusses the most important challenges in the development and application of nanoformulations in paediatric medicine, as well as future directions and upcoming trends in the field.

Long-term safety concerns

One of the significant challenges of the application of nanotechnology in paediatric formulation is the growth and development effects over a long time. One of the advantages that make nanoparticles well suited for delivery purposes is one of the same features that poses safety risks for long-term exposure to developing organisms.

A systematic review by Suk et al. (2016) highlighted the need for long-term safety assessments of nanoformulations in children. The authors emphasized that developing organs and tissues of children could be more vulnerable to possible toxicities of nanomaterials and that conventional toxicological studies in adult animals might fail to reflect fully such risks [45].

Of particular concern are:

1. Opportunities for nanoparticle accumulation in developing organs

2. Impact on the developing immune system

3. Possibility of genotoxicity and carcinogenicity

4. Impact on reproductive development

In 2021, Teng C et al. conducted a study on the long-term effects of titanium dioxide nanoparticles on the reproductive system of a mouse model. According to the study, nanoparticles have the potential to cause minimal reproductive parameter changes at early stages, thereby requiring meticulous evaluation of nanoformulations aimed for paediatrics use [46].

To overcome these issues, scientists are formulating novel methods to evaluate the long-term safety of nanoformulations. For instance, Bhattacharya et al. (2017) suggested employing in vitro organoid models that are derived from human pluripotent stem cells to evaluate the developmental toxicity of nanomaterials [47]. These models would yield significant insights into the long-term impact of nanoformulations on human development.

Scale-up and manufacturing issues

Another significant challenge in the scale-up and manufacturing of nanoformulations for paediatric applications is ensuring consistency, stability, and sterility during large-scale production of nanoformulations. It can be technically demanding and expensive.

Patra et al. (2018) reviewed the challenge of scale-up in the manufacturing of nanoformulations. The authors pointed out challenges, including:

1. Ensuring uniform particle size distribution during scale-up

2. Total elimination of organic solvents employed in the manufacturing process

3. Stability of encapsulated drug during manufacturing and storage

4. Economical production techniques that are amenable to commercial-scale manufacture [48]

To conquer such challenges, researchers are seeking new ways of production. As an example, microfluidic devices' utilization in the continuous manufacturing of polymeric nanoparticles was explored by Vanhoorne et al. (2019). The method provided enhanced control of particle size and drug loading compared to batch-like strategies. It promises greater homogenous large-scale nanoformulation production [49].

Need for age-appropriate dosage forms

Preparations suitable for a certain age are of special concern in paediatrics, and the problem is the same for nanoformulations. Several ages within the paediatric range offer specific requirements and abilities in terms of drug delivery.

Lopez et al. (2015) summarized the difficulties in the preparation of age-suitable oral dosage forms for children. The authors highlighted the importance of flexible dosing, palatability, and suitable excipients to be used across various age group [50]. The same is crucial for nanoformulations as well.

Researchers are also attempting to devise creative solutions. For instance, Preis et al. (2015) laboured over electrospinning to create nanofiber-based oral films that contain nanoparticles. This strategy could provide a flexible, simple-to-administer dosage form suitable for use across all paediatric age groups [51].

Ethical considerations in paediatric clinical trials

Carrying out clinical trials of nanoformulations in children is the most challenging ethically. These involve issues of informed consent, keeping the risk to participants as low as possible, and making sure that such trials are well planned to provide meaningful information but not put undue burden on children.

Rieder and Hawcutt (2016) discuss the ethical issues in paediatric drug trials. The authors noted that novel trial designs are required that can extract maximum information with minimal risk and discomfort to the paediatric subjects [52]. This factor is particularly important for nanoformulations, where the long-term impact may be unforeseeable.

Adaptive clinical trial designs and modelling strategies are also being researched to counter these challenges. For example, Hampson et al. (2014) suggested the application of Bayesian adaptive designs to paediatric clinical trials. It will enable more economical usage of data and possibly lower the number of participants involved, which is a valuable concern in paediatric trials of nanoformulations [53].

Future perspectives and emerging trends

Despite these challenges, the field of nanotechnology in paediatric formulations continue to advance rapidly. Several emerging trends and future directions show promise:

1. Personalized Nanomedicine: As a consequence of the recent progress in genomics and precision medicine, individual nanoformulationsby a patient's genetic make-up have gained renewed interest of late. Egusquiaguirre et al. (2015) showed a review highlighting the promise of nanomedicine for cancer therapy in children in a personalized way by specifically attacking tumor-specific changes at the genomic level via the use of nanocarriers [54].

2. Stimuli-responsive Nanocarriers: Scientists are designing "intelligent" nanocarriers that release the payload upon responding to certain stimuli, e. g., pH, temperature, or enzymes. The strategy could afford more precise regulation of drug delivery in paediatric patients. For instance, Gu et al. (2016) created glucose-stimulated insulin-releasing nanoparticles, which hold promise for diabetic management in children [55].

3. Combination Therapies: Nanocarriers have been increasingly explored for delivering two or more therapeutic compounds simultaneously. This may prove extremely useful in paediatric oncology. Singh et al. (2015) showed the promise of nanoparticles co-delivering chemotherapy drugs and siRNA for the therapy of drug-resistant paediatric brain tumours [56].

4. Theranostic Nanoparticles: Theranostic-nanoparticles with diagnostic and therapeutic capabilities-are very promising for paediatric use. In Baetke et al.'s (2015) review, the potential of theranostic nanoparticles in paediatric oncology can be observed, as "real-time monitoring of drug delivery and therapeutic response" with them is feasible [57].

Though obstacles remain in creating and applying nanoformulations to be used in paediatric environments, ongoing research and technological developments are introducing novel solutions to this issue. Ongoing collaboration between researchers, clinicians, regulators, and the pharmaceutical community will facilitate the overcoming of present obstacles in nanotechnology research and development. Finally, the application of nanotechnology holds great promise to enhance drug and therapeutic delivery in children and enhance the clinical outcomes for the paediatric population.

Persistent challenges

In spite of these limitations, nanotechnology in paediatric formulations keeps pace at a rapid rate. A few new trends and directions of the future hold promise:

1. Personalized Nanomedicine: Due to the recent advancements in genomics and precision medicine, patient-specific nanoformulations based on a patient's genetic profile have re-emerged in the focus of late. Egusquiaguirre et al. demonstrated a review with the emphasis on the potential of nanomedicine for paediatric cancer therapy in a personalized manner by targeting specifically tumor-specific alterations at the genomic level through the utilization of nanocarriers [58].

2. Regulatory barriers: The nanoscale preparations and special considerations for paediatric patients present regulatory issues. Harmonized definitions and particular guidance on paediatric nanomedicines are in dire need, as stated by Sainz et al. [59].

3. Ethical concerns in nanoformulation clinical trials: Clinical trials of nanoformulations in paediatric populations need to be conducted with due consideration of ethical concerns. The Rieder and Hawcutt highlighted the necessity of novel trial designs to optimize the information obtained while limiting risk to paediatric subjects [60].

Overall, liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles, and solid lipid nanoparticles are promising nanocarrier systems for paediatric drug formulations. These systems are viable options for many of the problems involved with paediatric drug delivery, such as poor bioavailability, high frequencies of dosing requirements, and toxic effects. More research is required to confirm their long-term safety profiles and to tailor their formulations to a particular paediatric use.

Aside from liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles, and solid lipid nanoparticles, pharmaceutical nanocrystals have also proven to be a promising nanocarrier system in paediatric drug delivery. Nanocrystals are sub-micron colloidal dispersions of pure drug particles surfactant-stabilised. They improve the solubility and bioavailability of poorly water-soluble drugs by increasing the surface area and saturation solubility of the drug.

Nanocrystals may be prepared by top-down methods such as high-pressure homogenization and media milling, or bottom-up methods such as precipitation. Their enhanced dissolution rates render them especially suitable for paediatric oral and parenteral products, where solubility constraints tend to restrict therapeutic effectiveness.

Although they have their strengths, there are challenges which include physical stability issues, likelihood of particle agglomeration, and scalability of manufacturing processes. Nonetheless, with ongoing research, nanocrystals are very promising in paediatric pharmacotherapy, especially for drugs characterized by low aqueous solubility.

Dendrimers: These branched, tree-shaped polymers provide exact control over size and surface functionality and are well suited to targeted drug delivery. Their multivalent surface allows for ligand or therapeutic agent attachment, which increases tissue-specific delivery and minimizes off-target effects. Dendrimer-based carriers in paediatric oncology have been found promising for delivering chemotherapies with increased tumor specificity and less system toxicity.

Micelles: Micelles are formed by amphiphilic molecules and result in a hydrophobic center and hydrophilic exterior, thus being appropriate for the delivery of poorly soluble drugs. Polymeric micelles have shown better pulmonary drug retention and less dosing frequency in paediatric respiratory disease.

Nanoemulsions: Oil-in-water or water-in-oil surfactant-stabilized dispersions with enhanced solubility and hydrophobic drug bioavailability. Their tiny particle size increases mucosal absorption making them attractive for oral and nasal paediatric dosage forms [61-64].

CONCLUSION

Nanotechnology in paediatric drug products is a fascinating field in pharmaceutical science with the potential to address most of the long-standing issues in paediatric medicine. The review will consider the state of the art, pointing out some of the significant advances, challenges, and future directions. The area of nanotechnology in paediatric drug delivery is at a crossroads. While important advances have been made in the creation of nanocarrier systems and the proof of concept of their potential advantage, much work remains to address safety issues, resolve manufacturing hurdles, and traverse regulatory challenges. Interdisciplinary teamwork will be the future. Nanoformulations are multifaceted and call for multidisciplinary expertise across materials science, pharmaceutics, paediatrics, toxicology, and regulatory science. Additionally, interaction with patients, caregivers, and physicians will be essential to guarantee that nanoformulations address the true needs of children in the real world. As studies are evolving in this sector, innovation has to be countered by caution. Extensive prospects loom for nanoformulations within paediatrics; and immense liabilities for therapy to reach the most vulnerable members of our populace. Finally, lots of possibilities remain for nanotechnology to transform paediatric medicine into a more child-friendly but more effective and safe form of drug development. This will only be realized by way of future studies, proper safety assessments, and careful consideration of regulatory and ethical issues that need to be in place. A lot can be added by nanotechnology in the form of better therapeutic outcomes and quality of life for the majority of paediatric patients due to the treatment of different medical conditions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to thank the Department of Science and Technology-Fund for Improvement of Science and Technology Infrastructure (DST-FIST) and Promotion of University Research and Scientific Excellence (DST-PURSE) and Department of Biotechnology-Boost to University Interdisciplinary Life Science Departments for Education and Research program (DBT-BUILDER) for the facilities provided in our department.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Gowtham Angamuthu: Literature review, Data curation, Writing-original draft, and Evaluation; Sanjai Rajagopal: Literature review, Data curation, and Writing-original draft; Giridhara Mahadevaswamy: Writing-original draft, Conceptualization, Critical Evaluation; Gurubaran Sivanathan: Writing-original draft, Conceptualization, Critical Evaluation; Nagasamy Venkatesh Dhandapani: Review and editing, Supervision, Evaluation, Visualization.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no conflict of interest

REFERENCES

Kearns GL, Abdel Rahman SM, Alander SW, Blowey DL, Leeder JS, Kauffman RE. Developmental pharmacology drug disposition action and therapy in infants and children. N Engl J Med. 2003 Sep 18;349(12):1157-67. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035092, PMID 13679531.

Fernandez E, Perez R, Hernandez A, Tejada P, Arteta M, Ramos JT. Factors and mechanisms for pharmacokinetic differences between pediatric population and adults. Pharmaceutics. 2011 Feb 7;3(1):53-72. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics3010053, PMID 24310425, PMCID PMC3857037.

Allegaert K, Verbesselt R, Naulaers G, Van Den Anker JN, Rayyan M, Debeer A. Developmental pharmacology: neonates are not just small adults. Acta Clin Belg. 2008 Jan-Feb;63(1):16-24. doi: 10.1179/acb.2008.003, PMID 18386761.

Batchelor HK, Marriott JF. Formulations for children: problems and solutions. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015 Mar;79(3):405-18. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12268, PMID 25855822, PMCID PMC4345951.

Standing JF, Tuleu C. Paediatric formulations getting to the heart of the problem. Int J Pharm. 2005 Aug 26;300(1-2):56-66. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2005.05.006, PMID 15979830.

Patra JK, Das G, Fraceto LF, Campos EV, Rodriguez Torres MD, Acosta Torres LS. Nano based drug delivery systems: recent developments and future prospects. J Nanobiotechnology. 2018 Sep 19;16(1):71. doi: 10.1186/s12951-018-0392-8, PMID 30231877, PMCID PMC6145203.

Hua S. Advances in nanoparticulate drug delivery approaches for sublingual and buccal administration. Front Pharmacol. 2019 Nov 5;10:1328. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.01328, PMID 31827435, PMCID PMC6848967.

Yang S, Wallach M, Krishna A, Kurmasheva R, Sridhar S. Recent developments in nanomedicine for pediatric cancer. J Clin Med. 2021 Apr 1;10(7):1437. doi: 10.3390/jcm10071437, PMID 33916177, PMCID PMC8036287.

Puri A, Loomis K, Smith B, Lee JH, Yavlovich A, Heldman E. Lipid based nanoparticles as pharmaceutical drug carriers: from concepts to clinic. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carrier Syst. 2009;26(6):523-80. doi: 10.1615/critrevtherdrugcarriersyst.v26.i6.10, PMID 20402623, PMCID PMC2885142.

Moreno Sastre M, Pastor M, Salomon CJ, Esquisabel A, Pedraz JL. Pulmonary drug delivery: a review on nanocarriers for antibacterial chemotherapy. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015 Nov;70(11):2945-55. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv192, PMID 26203182.

Germain M, Caputo F, Metcalfe S, Tosi G, Spring K, Aslund AK. Delivering the power of nanomedicine to patients today. J Control Release. 2020 Oct 10;326:164-71. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.07.007, PMID 32681950, PMCID PMC7362824.

Tinkle S, McNeil SE, Muhlebach S, Bawa R, Borchard G, Barenholz YC. Nanomedicines: addressing the scientific and regulatory gap. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2014 Apr;1313:35-56. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12403, PMID 24673240.

Ventola CL. Progress in nanomedicine: approved and investigational nanodrugs. PT. 2017 Dec;42(12):742-55. PMID 29234213, PMCID PMC5720487.

Bulbake U, Doppalapudi S, Kommineni N, Khan W. Liposomal formulations in clinical use: an updated review. Pharmaceutics. 2017 Mar 27;9(2):12. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics9020012, PMID 28346375, PMCID PMC5489929.

Ladaviere C, Gref R. Toward an optimized treatment of intracellular bacterial infections: input of nanoparticulate drug delivery systems. Nanomedicine (Lond). 2015 Oct;10(19):3033-55. doi: 10.2217/nnm.15.128, PMID 26420270.

Chastagner P, Devictor B, Geoerger B, Aerts I, Leblond P, Frappaz D. Phase I study of non-pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in children with recurrent/refractory high grade glioma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2015 Aug;76(2):425-32. doi: 10.1007/s00280-015-2781-0, PMID 26115930.

Schwendener RA. Liposomes as vaccine delivery systems: a review of the recent advances. Ther Adv Vaccines. 2014 Nov;2(6):159-82. doi: 10.1177/2051013614541440, PMID 25364509, PMCID PMC4212474.

Patra JK, Das G, Fraceto LF, Campos EV, Rodriguez Torres MD, Acosta Torres LS. Nano based drug delivery systems: recent developments and future prospects. J Nanobiotechnology. 2018 Sep 19;16(1):71. doi: 10.1186/s12951-018-0392-8, PMID 30231877, PMCID PMC6145203.

Beach MA, Nayanathara U, Gao Y, Zhang C, Xiong Y, Wang Y. Polymeric nanoparticles for drug delivery. Chem Rev. 2024 May 8;124(9):5505-616. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.3c00705, PMID 38626459, PMCID PMC11086401.

Muller RH, Mader K, Gohla S. Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) for controlled drug delivery a review of the state of the art. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2000 Jul;50(1):161-77. doi: 10.1016/s0939-6411(00)00087-4, PMID 10840199.

Muller RH, Radtke M, Wissing SA. Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) and nanostructured lipid carriers (NLC) in cosmetic and dermatological preparations. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2002 Nov 1;54 Suppl 1:S131-55. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00118-7, PMID 12460720.

Dasgupta S, Ghosh SK, Ray S, Mazumder B. Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) gels for topical delivery of aceclofenac in vitro and in vivo evaluation. Curr Drug Deliv. 2013 Dec;10(6):656-66. doi: 10.2174/156720181006131125150023, PMID 24274634.

Moslehi JJ. Cardiovascular toxic effects of targeted cancer therapies. N Engl J Med. 2016 Oct 13;375(15):1457-67. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1100265, PMID 27732808.

Marina NM, Cochrane D, Harney E, Zomorodi K, Blaney S, Winick N. Dose escalation and pharmacokinetics of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil) in children with solid tumors: a pediatric oncology group study. Clin Cancer Res. 2002 Feb;8(2):413-8. PMID 11839657.

Sonali SRP, Singh RP, Singh N, Sharma G, Vijayakumar MR, Koch B. Transferrin liposomes of docetaxel for brain targeted cancer applications: formulation and brain theranostics. Drug Deliv. 2016 May;23(4):1261-71. doi: 10.3109/10717544.2016.1162878, PMID 26961144.

Bhosale RR, Janugade BU, Chavan DD, Thorat VM. Current perspectives on applications of nanoparticles for cancer management. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2023;15(11):1-10. doi: 10.22159/ijpps.2023v15i11.49319.

Nafee N, Husari A, Maurer CK, Lu C, De Rossi C, Steinbach A. Antibiotic free nanotherapeutics: ultra-small mucus penetrating solid lipid nanoparticles enhance the pulmonary delivery and anti-virulence efficacy of novel quorum sensing inhibitors. J Control Release. 2014 Oct 28;192:131-40. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.06.055, PMID 24997276.

Cipolla D, Blanchard J, Gonda I. Development of liposomal ciprofloxacin to treat lung infections. Pharmaceutics. 2016 Mar 1;8(1):6. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics8010006, PMID 26938551, PMCID PMC4810082.

Kunda NK, Somavarapu S, Gordon SB, Hutcheon GA, Saleem IY. Nanocarriers targeting dendritic cells for pulmonary vaccine delivery. Pharm Res. 2013 Feb;30(2):325-41. doi: 10.1007/s11095-012-0891-5, PMID 23054093.

Lecaroz C, Blanco Prieto MJ, Burrell MA, Gamazo C. Intracellular killing of Brucella melitensis in human macrophages with microsphere encapsulated gentamicin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006 Sep;58(3):549-56. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl257, PMID 16799160.

Mahajan SD, Roy I, Xu G, Yong KT, Ding H, Aalinkeel R. Enhancing the delivery of anti-retroviral drug “saquinavir” across the blood brain barrier using nanoparticles. Curr HIV Res. 2010 Jul;8(5):396-404. doi: 10.2174/157016210791330356, PMID 20426757, PMCID PMC2904057.

Dhakal S, Renu S, Ghimire S, Shaan Lakshmanappa Y, Hogshead BT, Feliciano Ruiz N. Mucosal immunity and protective efficacy of intranasal inactivated influenza vaccine is improved by chitosan nanoparticle delivery in pigs. Front Immunol. 2018 May 2;9:934. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00934, PMID 29770135, PMCID PMC5940749.

Muthu MS, Feng SS. Pharmaceutical stability aspects of nanomedicines. Nanomedicine (Lond). 2009 Dec;4(8):857-60. doi: 10.2217/nnm.09.75, PMID 19958220.

US Food and Drug Administration. Drug products, including biological products that contain nanomaterials: guidance for industry. Retrieved from FDA Website; 2017.

European Medicines Agency. Reflection paper on the data requirements for intravenous liposomal products developed with reference to an innovator liposomal product. EMA/CHMP/806058/2009/Rev. Vol. 02; 2013.

Paediatric research equity act of 2003. Pub. L. Stat. 1936;117:108-55.

European Parliament and Council of the European Union. Regulation (EC) no 1901/2006 on medicinal products for paediatric use; 2006.

Sainz V, Conniot J, Matos AI, Peres C, Zupancic E, Moura L. Regulatory aspects on nanomedicines. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015 Dec 18;468(3):504-10. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.08.023, PMID 26260323.

Tinkle S, McNeil SE, Muhlebach S, Bawa R, Borchard G, Barenholz YC. Nanomedicines: addressing the scientific and regulatory gap. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2014 Apr;1313:35-56. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12403, PMID 24673240.

Riehemann K, Schneider SW, Luger TA, Godin B, Ferrari M, Fuchs H. Nanomedicine challenge and perspectives. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2009;48(5):872-97. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802585, PMID 19142939, PMCID PMC4175737.

International Council for Harmonisation. Clinical investigation of medicinal products in the paediatric population. Vol. E11. Retrieved from ICH website; 2000.

Nanotechnology task force report. US Food and Drug Administration; 2007.

European technology platform on nanomedicine. Contributing to the innovation of nanomedicine; 2019.

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. Safety of manufactured nanomaterials. Retrieved from OECD website; 2019.

Suk JS, Xu Q, Kim N, Hanes J, Ensign LM. PEGylation as a strategy for improving nanoparticle based drug and gene delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2016 Apr 1;99(A):28-51. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2015.09.012, PMID 26456916, PMCID PMC4798869.

Teng C, Jiang C, Gao S, Liu X, Zhai S. Fetotoxicity of nanoparticles: causes and mechanisms. Nanomaterials (Basel). 2021 Mar 19;11(3):791. doi: 10.3390/nano11030791, PMID 33808794, PMCID PMC8003602.

Boyd WA, Smith MV, Co CA, Pirone JR, Rice JR, Shockley KR. Developmental effects of the ToxCast™ phase I and phase II chemicals in Caenorhabditis elegans and corresponding responses in zebrafish rats and rabbits. Environ Health Perspect. 2016 May;124(5):586-93. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1409645, PMID 26496690, PMCID PMC4858399.

Patra JK, Das G, Fraceto LF, Campos EV, Rodriguez Torres MD, Acosta Torres LS. Nano based drug delivery systems: recent developments and future prospects. J Nanobiotechnology. 2018 Sep 19;16(1):71. doi: 10.1186/s12951-018-0392-8, PMID 30231877, PMCID PMC6145203.

Vanhoorne V, Vervaet C. Recent progress in continuous manufacturing of oral solid dosage forms. Int J Pharm. 2020 Apr 15;579:119194. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.119194, PMID 32135231.

Lopez FL, Ernest TB, Tuleu C, Gul MO. Formulation approaches to pediatric oral drug delivery: benefits and limitations of current platforms. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2015;12(11):1727-40. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2015.1060218, PMID 26165848, PMCID PMC4673516.

Preis M, Woertz C, Kleinebudde P, Breitkreutz J. Oromucosal film preparations: classification and characterization methods. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2013 Sep;10(9):1303-17. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2013.804058, PMID 23768198.

Rieder M, Hawcutt D. Design and conduct of early phase drug studies in children: challenges and opportunities. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016 Nov;82(5):1308-14. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13058, PMID 27353241, PMCID PMC5061783.

Hampson LV, Herold R, Posch M, Saperia J, Whitehead A. Bridging the gap: a review of dose investigations in paediatric investigation plans. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014 Oct;78(4):898-907. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12402, PMID 24720849, PMCID PMC4239983.

Egusquiaguirre SP, Igartua M, Hernandez RM, Pedraz JL. Nanoparticle delivery systems for cancer therapy: advances in clinical and preclinical research. Clin Transl Oncol. 2012 Feb;14(2):83-93. doi: 10.1007/s12094-012-0766-6, PMID 22301396.

Gu Z, Dang TT, Ma M, Tang BC, Cheng H, Jiang S. Glucose responsive microgels integrated with enzyme nanocapsules for closed loop insulin delivery. ACS Nano. 2013 Aug 27;7(8):6758-66. doi: 10.1021/nn401617u, PMID 23834678.

Singh JK, Simoes BM, Clarke RB, Bundred NJ. Targeting IL-8 signalling to inhibit breast cancer stem cell activity. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2013 Nov;17(11):1235-41. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2013.835398, PMID 24032691.

Baetke SC, Lammers T, Kiessling F. Applications of nanoparticles for diagnosis and therapy of cancer. Br J Radiol. 2015 Oct;88(1054):20150207. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20150207, PMID 25969868, PMCID PMC4630860.

Patra JK, Das G, Fraceto LF, Campos EV, Rodriguez Torres MD, Acosta Torres LS. Nano based drug delivery systems: recent developments and future prospects. J Nanobiotechnology. 2018 Sep 19;16(1):71. doi: 10.1186/s12951-018-0392-8, PMID 30231877, PMCID PMC6145203.

Sainz V, Conniot J, Matos AI, Peres C, Zupancic E, Moura L. Regulatory aspects on nanomedicines. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015 Dec 18;468(3):504-10. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.08.023, PMID 26260323.

Rieder M, Hawcutt D. Design and conduct of early phase drug studies in children: challenges and opportunities. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016 Nov;82(5):1308-14. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13058, PMID 27353241, PMCID PMC5061783.

Chauhan AS. Dendrimers for drug delivery. Molecules. 2018 Apr 18;23(4):938. doi: 10.3390/molecules23040938, PMID 29670005, PMCID PMC6017392.

Jain A, Bhardwaj K, Bansal M. Polymeric micelles as drug delivery system recent advances approaches applications and patents. Curr Drug Saf. 2024;19(2):163-71. doi: 10.2174/1574886318666230605120433, PMID 37282644.

Chauhan M, Mazumder R, Rani A, Mishra R, Pal RS. Preparations applications patents and marketed formulations of nanoemulsions a comprehensive review. Pharm Nanotechnol. 2024 Sep 27. doi: 10.2174/0122117385325186240912110731, PMID 39350420.

Sivanathan G, Rajagopal S, Mahadevaswamy G, Angamuthu G, Dhandapani NV. Pharmaceutical nanocrystals: an extensive overview. Int J Appl Pharm. 2024 Nov 7;16(6):1-9. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2024v16i6.52257.