Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 4, 2025, 66-76Review Article

3D PRINTING TECHNOLOGIES IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF A BIORELEVANT IN VITRO MODEL OF THE NASAL CAVITY: NEW STEP OF INTRANASAL DRUGS QUALITY ASSESSMENT

ELENA BAKHRUSHINA1, IOSIF MIKHEL2*, SALMA ABUELEZ3, KSENIYA EREMEEVA4, XI YANG5, VALERIY SVISTUSHKIN6, OLGA STEPANOVA7, IVAN KRASNYUK JR.8, GLEB ZHEMERIKIN9, IVAN KRASNYUK10

1,2Department of Pharmaceutical Technology A. P. Nelyubin Institute of Pharmacy, I. M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University (Sechenov University), Moscow, Russia. 3I. M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University (Sechenov University), Moscow, Russia. 4,5,6Department for Ear, Nose and Throat Diseases N. V. Sklifosovskiy Institute of Clinical Medicine, I. M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University (Sechenov University), Moscow, Russia. 7Department of Pharmacology A. P. Nelyubin Institute of Pharmacy, I. M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University (Sechenov University), Moscow, Russia. 8Head of Department of Analytical, Physical and Colloidal Chemistry A. P. Nelyubin Institute of Pharmacy, I. M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University (Sechenov University), Moscow, Russia. 9Department of Faculty Surgery No.1 N. V. Sklifosovskiy Institute of Clinical Medicine, I. M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University (Sechenov University), Moscow, Russia. 10Head of Department of Pharmaceutical Technology, A. P. Nelyubin Institute of Pharmacy, I. M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University (Sechenov University), Moscow, Russia

*Corresponding author: Iosif Mikhel; *Email: mikheliosif@gmail.com

Received: 01 Mar 2025, Revised and Accepted: 31 May 2025

ABSTRACT

The intranasal route has been a subject of exploration for the delivery of active pharmaceutical ingredients across a wide range of chemical classes and pharmacological categories. Notwithstanding its therapeutic potential, the anatomical intricacy and physiological variability of the nasal cavity pose significant challenges to the precise evaluation of drug delivery. To address these challenges, in vitro studies employing anatomically and functionally relevant 3D models have become imperative. Advances in 3D printing technologies have enabled the creation of precise and reproducible nasal cavity replicas, which can support drug characterization, particularly in evaluating drug deposition patterns and predicting bioavailability.

This review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the current state-of-the-art methods and materials employed in 3D printing of nasal cavity models. Presently, the Koken LM-005 remains the sole commercially available model, underscoring the pressing need for more advanced and customizable alternatives. Experimental models are under development; however, they vary widely in anatomical fidelity and clinical applicability. The analysis emphasizes the necessity of incorporating anatomical accuracy and physiological relevance–such as airflow dynamics and mucosal properties–into the design of nasal cavity models for pharmaceutical testing.

The findings underscore the real-world utility of additive manufacturing in pharmaceutical research. The utilization of 3D printed models holds considerable promise in enhancing the quality assessment of intranasal dosage forms and can serve as valuable tools in both preclinical development and personalized medicine. As the technology advances, it holds the potential to reduce reliance on animal testing, streamline formulation development, and ultimately enhance therapeutic outcomes.

Keywords: 3D printing technology, Biorelevant model, Nasal cavity, In vitro studies, Biomedical application, 3D model, Nasal airflow

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i4.54101 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Intranasal administration of drugs has been used for therapeutic purposes for several centuries [1]. Over the past five years, the development of nasal drug delivery systems has become even more significant due to the numerous advantages of this route of administration [2]. In addition to the treatment of common nasal congestion or allergic rhinitis, there is a wide range of pathologies that can be treated by nasal drug administration. Low proteolytic activity, relatively large distribution area, and good blood supply to the mucous membrane allow for high drug bioavailability and open up new opportunities for systemic use of intranasal dosage forms [3]. Thus, brain-targeted drug delivery for the treatment of Сentral Nervous System (CNS) diseases is one of the most challenging and promising areas of research [4]. For instance, insulin deficiency can lead to serious neurodegenerative disorders, particularly Alzheimer’s disease [5, 6]. Intranasal administration of the hormone has potential to address the development of CNS diseases, improve cognitive function, and prevent memory impairment in diabetic or post-surgical patients [7]. In the long term, further development of intranasal drugs opens up new opportunities to struggle against diseases such as Parkinson's disease, acute migraine, panic attacks, and Coronary Heart Disease (CHD) [8]. Moving away from hypothetical examples and drugs in development, it is worth looking at significant developments that have entered the civil market. One recent development is NARCAN® Nasal Spray (Emergent Operations Ireland Limited), which is used to reverse opioid overdoses [9]. Opioids, like other narcotics, are known to have harmful effects on the brain, and in the event of an overdose, their effects must be reversed immediately. The quickest and easiest way to achieve this is through nasal administration for direct delivery from the nose to the brain. Other examples of successful registrations of nasal preparations for the delivery of APIs to the brain are mainly related to the treatment of migraine and headache. Numerous products containing zolmitriptan (ZOMIG Nasal Spray, Impax Specialty Pharma; Zolmist Nasal Spray, Cipla Ltd.), sumatriptan (Imigran, GlaxoSmithKline Pharmaceuticals; Imitrex, GlaxoSmithKline Pharmaceuticals) and ketorolac tromethamine (Ketorolac, Pharmamed; SPRIX®, Assertio Therapeutics, Inc.) have been registered worldwide [10-13].

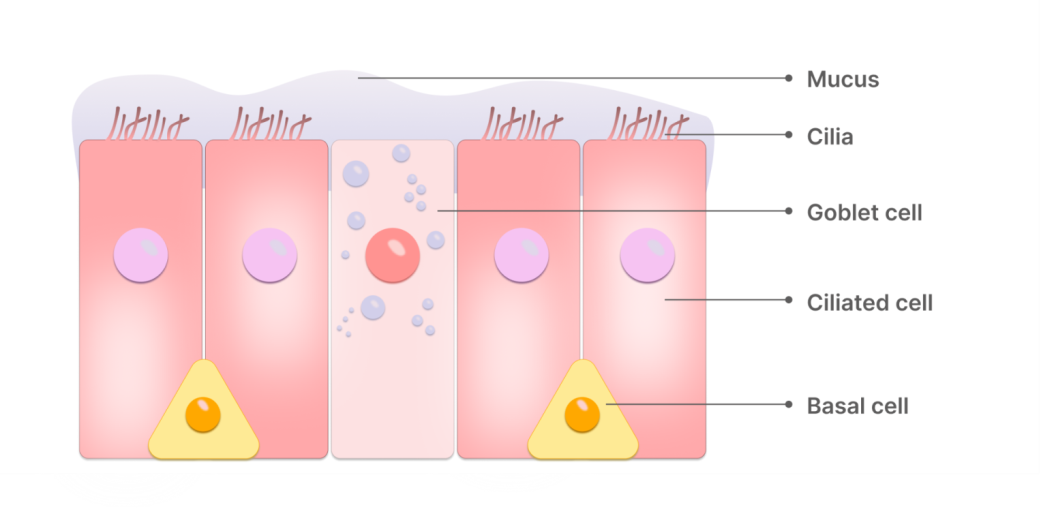

Although the intranasal route provides high bioavailability and allows for the administration of substances not suitable for oral use (small molecules, polar substances, peptides, proteins), there are several challenges associated with this route of drug delivery. On the one hand, the drug or Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) must overcome several natural barriers (epithelial layer, mucus layer, interstitial and basal membranes, and capillary endothelium (fig. 1)); on the other hand: a–the high mucociliary clearance rate leads to rapid drug elimination from the nasal cavity; b-there is low permeability for certain classes of molecules; c-there is a high risk of the drug reaching other organs of the respiratory system due to improper delivery technique [8, 14-18]. It should be recognised that the main limiting factor in nasal drug delivery is mucociliary clearance, which aims to rapidly remove foreign substances from the surface of the nasal mucosa. The intensity of mucociliary clearance can be influenced by many factors, including various diseases and addictions. In 2021, a team of scientists from Turkey conducted a study on the effect of coronavirus infection and smoking status on the rate of nasal clearance using the saccharin test. The results of the study confirmed that patients with COVID-19 and smokers had the fastest clearance rate, followed by smoking patients in the control group [19]. A long-term cohort study of patients who underwent radiotherapy showed that the clearance rate slows down significantly after radiotherapy [20]. All patients in the study group had a negative saccharin test result, while the control group had only positive results. Such studies provide a clear picture and help to consider the risks of intranasal drug delivery.

Despite such an impressive effect of clearance on excipients (including drugs), there are several methods to counteract the effect of clearance on the drug. These methods include the use of thicker dosage forms (gels, emulsions, suspensions) and the development of innovative in situ delivery systems [21–23].

Fig. 1: Nasal cavity epithelium structure

Among other issues, to ensure proper absorption of the substance, prevent its premature removal from the nasal cavity, and enhance the bioavailability of the API, additional methods of changing the deposition profile of the substance are required. In particular, it is necessary to enhance the mucoadhesive and absorption properties of the drug [8, 24, 25].

Since the anatomy and function of the nasal cavity require careful study of parameters such as drug release and deposition, mucoadhesion and aerodynamic characteristics, in vitro studies become the optimal solution for evaluating the biopharmaceutical properties of intranasal dosage forms [26, 27]. They allow for screening in easily controlled conditions with high speed and efficiency at a lower cost, compared to in vivo methods of analysis.

Today, screening of intranasal drugs is performed by ex vivo and in vivo diagnostic methods. However, due to the cost and complexity of validating study processes, there is a need for accessible in vitro analysis methods [28]. 3D modeling of the nasal cavity is a relatively simple and cost-effective method that can be an optimal solution for conducting in vitro studies. When properly constructed, a biorelevant model can not only reproduce the geometry of the nasal cavity but also replicate most of the physiological processes occurring in it.

Although in vitro studies cannot completely replace in vivo studies, they serve as a valuable tool in the design and optimization of intranasal dosage forms, providing important preliminary data that can guide further research and development [29, 30].

Biorelevant models should replicate the physiological environment of the area. While a number of approaches exist to create pH, mucosa and airflow, it is quite difficult to reproduce the movement of epithelial cilia.

The aim of this review is to evaluate existing techniques for creating 3D models of the nasal cavity to analyze the quality of intranasal drugs in vitro and to propose a new model with the most relevant characteristics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A comprehensive analysis of PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, and ResearchGate databases was performed. The main dataset was obtained from medical publication databases. The search was conducted using the keywords: 3D printing technology, biorelevant model, nasal cavity, in vitro studies, biomedical application, 3D model, nasal airflow. Due to the specificity of the topic under study and, in general, its modernity, we analyzed almost the entire volume of published data for the period from 1997 to 2025.

Anatomy of the nasal cavity: architectonics, critical points of analysis

Biorelevant in vitro model is a widely used tool for in vitro studies of various dosage forms [31, 32]. It allows both the design of near-realistic drug delivery conditions and the prediction of subsequent in vivo analyses. However, the nasal cavity has several features that can be an obstacle to the development of a biorelevant model.

The primary issue with the nasal cavity is that its anatomy is unique for each individual. The anatomical characteristics of each patient can greatly alter the distribution of the drug on the mucosal surface. Even minor anatomical variations can significantly affect the effectiveness of therapy in a particular patient. Therefore, in order for the model to be geometrically accurate, it is not enough to use the architectonics of the nasal cavity of only one person. Analysis of a patient cohort enables the construction of an "ideal patient" model characterized by averaged anatomical parameters. This approach allows for the consideration of interindividual variations in the anatomy and architectonics of the nasal cavity.

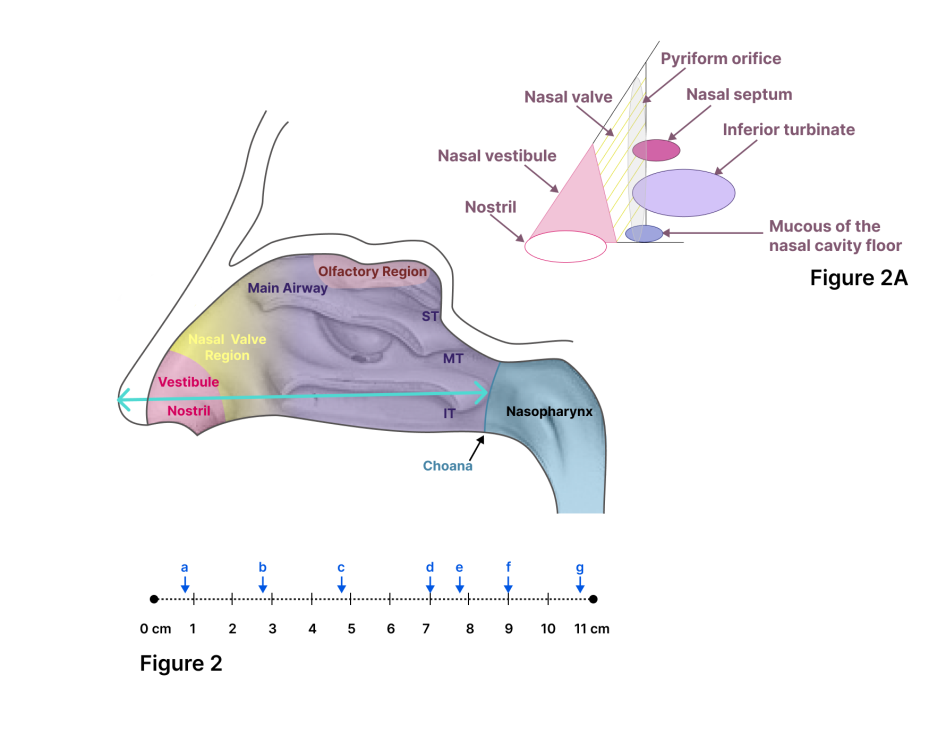

The architectonics of the nasal cavity represents a complex geometric model. The anterior ¾ of the nasal cavity are divided by the nasal septum into two mirror-symmetrical halves, right and left [33]. The nasal septum is the medial wall of the nasal cavity and consists of anterior chondral and posterior bone parts. The lateral wall of the nasal cavity is lined with three conchae, which are the superior, middle, and inferior nasal turbinates. These structures divide the nasal passage vertically into the corresponding areas: dorsal, medial, and ventral. Two nasal passages merge into one at the level of the posterior end of the nasal septum and the posterior end of the inferior nasal turbinate; this is the area of the entrance to the nasopharynx [34].

The cross-section in the coronal projection of the nasal cavity varies significantly in shape at different levels. The entrance through the two nostrils (usually taken as the zero point) leads to the vestibule of the nasal cavity, which extends approximately 1.5 cm to the level of the nasal valve. The nasal valve region represents the narrowest part of the nasal cavity, with the angle of the nasal valve between the caudal edge of the superior lateral cartilage and the nasal septum being 10-15°, opening downward. It is also an important airflow regulator, with this region accounting for more than half of the nasal resistance [35, 36]. The boundary of the nasal valve is formed by the floor of the nasal cavity from below and the anterior end of the inferior nasal turbinate from behind.

The distance between the nasal valve and the nasopharynx is the main nasal airway. Thus, linear measurements in the nasal cavities are generally taken in three dimensions: 1–the length of the nasal septum from the tip of the nose to the nasal septal end point; 2–the height of the nasal cavity at the same nasal septal end point; 3–the width of the nasal cavity at the same location. These criteria were chosen to minimize the risk of artifacts [3].

The nose is not a static anatomical structure, but a dynamic organ with asymmetric airflow [37]. It has been determined that the regularity of changes in airflow is contingent upon the condition of the erectile tissues of the inferior nasal turbinate. Thus, each half of the nose functions with full load alternately, alternating rest with resistance to the airflow [38]. Close reflex interconnection of both halves, the nasal cycle, is only possible in the absence of anatomical changes leading to narrowing of the nasal passages, such as deviated nasal septum or hypertrophy of the nasal turbinate.

The majority of intranasal drugs necessitate the use of specialized spray delivery systems to ensure effective administration into the nasal cavity. Upon inhalation, the airstream entering the nasal passages initially becomes turbulent at the level of the nasal valve, subsequently transitioning into a more linear, laminar flow as it progresses through the cavity.

Numerous studies on the aerodynamics of nasal breathing demonstrate that the majority of the inhaled air, given the normal structure of the nasal valve, nasal septum, and nasal turbinate, passes through the common nasal passage along the middle nasal turbinate, while a small amount enters the dorsal part and olfactory region [39, 40]. During exhaling, the airflow from the nasopharynx enters the nasal cavity through the choana, an oval-shaped opening, and, without turbulence, diffusely spreads mainly through the common and inferior nasal passages. Turbulent airflow inevitably affects the geometry of drug atomisation in the cavity. Depending on the airflow velocity during inhalation, the area of drug droplet deposition on the mucosal surface changes. Laminar airflows during inhalation and exhalation do not affect drug distribution as much but may generally affect drug removal from the mucosal surface. The modelling of airflow increases the similarity of 3D models to real physiological conditions.

The area of the nasal cavity is approximately 160-180 сm2, nasal cavity volume is about 15 ml, length 12-14 cm, and the pH 5.5-6.5 [41]. The temperature in the nasal cavity is slightly lower than body temperature and ranges between 33-35 °C. Different parts of the nasal cavity are covered by 4 different types of epithelia. The predominant type is ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium, also known as respiratory mucosa. The nasal vestibule is primarily covered with squamous epithelium, transitional epithelium is located in the narrow zone between the first two types, and olfactory epithelium is in its corresponding zone.

The mucous membrane of the nasal cavity, especially of the inferior nasal turbinate, carries out the most active transport of secretion, which occurs along two main directions: from the anterior end of the inferior nasal turbinate forward (at a distance of 1-1.5 cm) and along the surface of the inferior nasal turbinate behind and down to the floor of the nasal cavity and into the nasopharynx. Thus, when modeling the nasal cavity, it is often necessary to take into account not only geometry but also complex aerodynamics, mucociliary clearance, and other physiological processes occurring in the nasal cavity [42]. The critical points and parameters of the model to meet the requirements of biorelevance are shown in fig. 2 and 2A.

Fig. 2: Lateral view of the human nose. Linear measurements of the nose: septum length from the tip of the nose to the closest endpoint of the nasal septum. ST, MT, and IT refer to the superior, middle, and inferior turbinate, respectively. Fig. 2A. Nasal valve drawing

Requirements and limitations for model construction

Before creating a 3D model, it is necessary to determine the optimal parameters of the printed sample as well as the most suitable manufacturing technology [43]. The quality of the printed object directly defines the scope of possibilities of using the 3D model for in vitro studies of intranasal drug forms.

3D model characteristics

Surface finish

One of the common problems with many 3D printing methods is that they produce models with rough and uneven surfaces. These irregularities increase friction and cause turbulence, making it harder to accurately simulate airflow in the nasal cavity [44, 45]. The surface of the model should possess a moderate degree of roughness. Certain printing techniques, due to their layer-by-layer material deposition, result in a significant number of pores and surface irregularities. When a drug is administered, these pores may retain a substantial amount of the substance, thereby compromising the reliability of the study. Conversely, a completely smooth surface would prevent even Simulated Nasal Fluid (SNF) from adhering, which is essential for replicating the internal conditions of the nasal cavity. To achieve a physiologically relevant model, the most straightforward approach involves fabricating initially smooth models followed by surface treatment of the internal cavity to attain an optimal level of roughness consistent with nasal physiology.

Precision

Each person's nasal cavity is individualized. Therefore, when developing a model, there are difficulties in reproducing a geometry that is as close as possible to the real anatomy of the human nasal cavity [44].

Porosity

Porosity occurring on 3D printed models can be related to both the peculiarities of the printing material itself and the manufacturing technology. Due to the overlapping of one layer on another or improper temperature selection, depressions may be created in the model, interfering with the interpretation of the end results of in vitro analysis of the intranasal drug [44].

Selection of the relevant mucosal surface

The 3D model allows reproducing the geometry but does not reflect the physiological properties of the nasal cavity. The interaction between the drug particles and the walls of the model directly depends on whether the surface is wet or dry [46]. In this regard, it is also necessary to select an artificial mucus that will simulate the mucosal surface of the nasal cavity [47]. The artificial mucosa should not react with the model material and should not contain components that would interfere with the determination of APIs during spectroscopic or chromatographic analysis of the deposition of the intranasal drug form. Generally, there are three options for replicating the mucosal surface: 1-using liquids-water or propylene glycol and isopropanol (1:1); 2–application of glycerol or ethanol combined with surfactants; and 3–mucin solutions [48–50]. To simplify experiments, many research groups choose for simulating SNF water, glycerol, buffer solutions, and other simple liquids that lack sufficient biorelevance. Since one of the most important properties of an intranasal drug is its mucoadhesive capacity, mucin becomes the key component of SNF in the simulation of nasal secretions. Despite its essential role in such studies, recent years have seen the development of alternative methods aimed at replacing mucin. Ethical and financial considerations are prompting a shift toward the use of synthetic mucin analogues [51–53].

In addition to mucin, nasal secretions contain ions such as sodium, potassium, and calcium, which can influence drug bioavailability and the behavior of various API delivery systems. Therefore, modeling only the rheological properties of nasal mucus is insufficient to ensure the reliability of the study [53].

In a recent validation study of swabs for sampling on SARS-CoV-2, a different approach was used [54]. The 3D model was lined with a silk sponge to recreate the tissue structure of the nasal cavity, and then approximately 0.1 ml of polyethylene oxide solution was applied as artificial mucus. The concentration of polyethylene oxide was selected to mimic the viscosity of both healthy and inflamed mucosa (0.5% and 3%, respectively).

Printing materials

3D printing uses a wide range of materials to create biorelevant in vitro models. The choice of material will depend on both the manufacturing technology and the desired characteristics of the model [55].

Silicones

Silicones are a group of hydrophobic transparent polymers containing silicon, hydrogen, and oxygen. Unlike other polymers, the main chain is composed of silicon rather than carbon, and the side chains consist of fluorinated, aromatic, and aliphatic groups. Silicones can be used at temperatures ranging from-100 to 250 °C. Since these polymers have low surface free energy and therefore, do not bond well together, adhesives (acrylates, UV curing adhesives) are often used to form stronger bonds [56].

Acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS)

Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene (ABS) is an opaque thermoplastic used in Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) technology. Compared to other polystyrenes, it has greater impact strength and resistance to thermal and chemical attacks [56].

Biopolymers

Biopolymers are materials that either occur naturally (proteins, sugars) or are synthesized from naturally occurring biological materials such as sugars, fats, oils, and starch.

Polylactic acid (PLA)

Polylactic Acid (PLA) is an insoluble, synthetic biodegradable polymer [57]. It is the most widely studied and used material for FDM technology and has been approved by the FDA (Food and Drug Administration, USA) as a material for implants and as a component of prolonged drug delivery systems [58, 59].

Polyethylene glycol (PEG)

PEG is a water-soluble, biocompatible, and amphiphilic polymer. Due to its highly crystalline nature, polyethylene glycol is one of the most chemically stable biopolymers [56]. PEGDA (PEG diacrylate/polyethylene glycol diacrylate) is a polymer that is a derivative of polyethylene glycol. Due to the formation of cross-links, PEGDA is mechanically more stable than PEG [60].

Table 1: Comparative characterization of the most common materials

| Material | Advantages | Disadvantages | Ref. |

| Silicones | -stability over a wide temperature range (-100 to+250 °C) -resistance to oxidation and degradation -UV resistance -chemically inert |

-high permeability to gases and liquids -relatively fragile -high abrasion -difficult to bond |

[56] |

| ABS | -thermoplastic -high-strength -easy to process |

-opaque -exposed to UV radiation |

[56] |

| PLA (polylacticacid) | -thermoplastic -high-strength -non-toxic -more environmentally friendly |

-does not undergo plastic deformation -hygroscopic |

[57–59] |

| PEG (polyethyleneglycol) | -chemically resistant | -toxic | [56, 60] |

| Epoxyresins | -chemically resistant -corrosion resistance -flexible |

-susceptible to damage from sunlight exposure -relatively brittle -low thermal conductivity |

[61, 62] |

Epoxy resins

Epoxy resins are widely used in additive manufacturing technology. They are thermosetting or photosensitive materials that cure by reaction with an agent–UV radiation (PIs-Photoinitiating Systems) [61]. Epoxy resins belong to the family of monomeric or oligomeric materials and have good mechanical and electrical insulating properties, corrosion and chemical resistance, particularly to alkaline environments [62]. A comparative characterization of the most common materials is presented in table 1.

3D printing technologies

Since the structure of each individual's nasal cavity is unique, additive manufacturing techniques are widely used to develop a relevant 3D model [63, 64].

Additive manufacturing, also known as rapid prototyping, is the process of joining materials together to create objects based on 3D model data, usually layer by layer, as opposed to a substrate manufacturing methodology [65].

Fused deposition modeling (FDM)

Fused Deposition Modeling (material extrusion method) is a simple and relatively cheap additive manufacturing technology. FDM is based on melting a polymer material and then extruding it from the nozzle of a 3D printer using oppositely moving rollers. The material is applied to the plate layer by layer, moving the nozzle in different planes by G-code commands [66].

Polymers such as polylactic acid (PLA), polycaprolactone (PCL), polypropylene (PP), polyethylene (PE), polybutylene terephthalate (PBT), acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) are used as printing materials [67]. Since polypropylene is solvent-resistant, it is most commonly used to form the desired model.

Despite the simplicity and high speed of the technology, FDM is rarely used to print in vitro models. This additive manufacturing method does not allow printing thin layers due to the low resolution of the printer. The temperature required for printing can affect the quality of the material and lead to thermal shrinkage of the layers and their overlapping. As a consequence, there is a high probability of obtaining a rough and uneven model, which limits the range of in vitro studies conducted to assess the quality of intranasal dosage forms [68].

Stereolithography (SLA)

Fused deposition modeling (material extrusion method) is a simple and relatively cheap additive Stereolithography (SLA), also known as solid freeform fabrication (SFF), is based on the polymerization of a photopolymer material using UV radiation. The layer-by-layer printing of the model occurs in a vat containing a liquid polymer resin [69]. The printer platform is also immersed in the vat and due to its gradual lifting and spot exposure to UV radiation, the object is formed. Different types of photopolymer resin (acrylic, epoxy) are used as photopolymer material, as well as soft silicone, which is widely used in printing models for medical applications. Due to the fact that the method does not involve the use of temperature, the probability of thermal shrinkage is drastically reduced. Moreover, this method of layer-by-layer printing of an object allows the formation of thin layers, which doesn’t increase models’ porosity [70].

The limiting factor of stereo lithography is the fragility of printed models, large losses due to possible incomplete polymerization of the material used, and the need for long cleaning with the selection of a relevant solvent that will not damage the surface of the object itself.

Powder bed fusion (PBF)

This method is categorized into 4 groups: Selective Laser Sintering (SLS), Selective Laser Melting (SLM)/Direct Metal Laser Sintering (DMLS), Electron Beam Melting (EBM) and Multi Jet Fusion (MJF) [71–75]. PBF technology is based on forming patterns through a combination of elevated temperature and thermal energy sources. The material used is a powder bed (particularly nylon) through which, depending on the technology, different types of energy are passed [76]. For example, SLS, SLM, and DML involve the use of a laser beam, EBM involves an electron beam, and MJF works with an infrared lamp. Thermal energy heats the powder bed until the powder particles are partially or completely sintered/melted, and then a new portion of material is placed on top [77]. The method allows simultaneous processing of multiple parts; however, it is more costly compared to other additive manufacturing technologies. Furthermore, the surface of the model is solid and porous due to the temperature and the difficulty of creating a perfect fusion of the powder bed particles [76].

Material jetting process (MJP)

Multi-jet printing is one of the most precise additive manufacturing technologies. The method is based on dispersing photopolymer material through the printer head onto specific points of the pallet, with polymerization using UV exposure [64]. In many ways, the principle of operation is similar to stereolithography technology. However, unlike SLA, in multi jet printing the pallet moves back and forth, which allows the photopolymer material to overlap evenly along the axis layer by layer. This technology reduces losses and improves the accuracy and smoothness of the resulting models [78].

Nevertheless, the method has its drawbacks. Besides being an expensive technology, the acrylic photopolymer resin used in MJP is not durable [64]. As a consequence, the models printed using this technology are fragile and easily deform even when slightly heated.

A brief comparative assessment of reproducible parameters of different 3D printing methods is summarized in table 2.

Table 2: Brief comparative evaluation of reproducible parameters of different 3Dprinting methods

| Printing technology | Surface finish | Strength | Thermal shrinkage | Porosity | Precision | Ref. |

| Fused deposition modeling (FDM) | Rough and uneven | High | High | High | Not achieved | [66–68] |

| Stereolithography (SLA) | Flexible and smooth | Low | No shrinkage | Low | High | [69, 70] |

| Powder bed fusion (PBF) | Rough and uneven | High | High | High | Not achieved | [71, 76] |

| Material jetting process (MJP) | Flexible and smooth | Low | No shrinkage | Low | Highest | [64] |

Existing in vitro models of the nasal cavity and their comparative characterization

Transparent nasal cavity model LM-005, Koken Co, Japan

The Koken nasal cavity model (Koken LM-005) is the only currently commercially available nasal cavity model derived from CT images of the nasal cavity of an Asian human cadaver [79]. The Koken LM-005 is made of silicone and is divided into two halves. Due to the removable septum and transparent material, it is possible to visualize the internal structures of the nose. Since the model is easily accessible, it has been widely used to study the deposition of intranasal dosage forms. In particular, it has been used to study the deposition profile of melatonin-loaded pectin/hypromellose microspheres as well as the deposition of in situ gels of fluticasone containing various polymers (sodium hyaluronate, pectin, and gellan gum) [80, 81].

The KOKEN-LM is positioned as a geometrically accurate educational model. However, the model is developed based on the nasal cavity structure of a single individual, which precludes the validation of in vitro studies based on analyses conducted with this model. In the comparative analysis of KOKEN-LM with its analog (Optinose nasal cavity model-OptiNose AS, Oslo, Norway) it was not confirmed that the parameters of the model correspond to the real geometry of the human nasal cavity [82]. Moreover, despite the advantages of the transparency of the model, this material creates increased smoothness of the sample surface.

As a consequence, for the accuracy of studies conducted on the model, it is necessary to create additional conditions to achieve viscosity similar to the real nasal mucosa.

To conduct the study, the Koken model was used with slight modification [83]. Specifically, the nasal cavity model was placed on a stand and connected to a respiratory pump (Respiratory Pump Model 613, Harvard Apparatus). The pump provided a respiratory simulation at an inspiratory flow rate of 0 l/min (no breathing) or 20 l/min (human moderate inhalation rate). To achieve a more accurate simulation of inspiration in the nasal cavity, the volumetric flow rate was measured using an inspiratory flow meter (In-Check Nasal). During the test, the powder formulation was sprayed to a depth of 5 mm into the unobstructed nostril at an angle of 60° from the horizontal plane and 0° from the vertical plane, with one nostril blocked. For qualitative assessment of the deposition profile, the model was photographed against a dark background. For quantification, the deposited particles were collected, and their content was calculated from the total dose of drug administered.

Another study on the commercially available KOKEN-LM model aimed to evaluate the gelation efficacy of PecSys (an in situ system containing low-methoxyl esterified pectin (LM)) in contact with nasal cavity mucosal components [81]. The method involved applying a medical lubricant containing calcium (a physiologically significant electrolyte) to the inner surface of the nasal cavity model in a quantity of 3g. Other mucosal cations do not have a significant effect on the in situ gelation of the system; thus, in order to prevent undesirable interaction of components, they were not taken into account in the study. The model was then placed on a flat surface at an angle of 10° from the horizontal plane. The dispensing nozzle was inserted 1 cm into the nostril at an angle of 45° from the horizontal plane.

Nasal cavity model for comparative study of aerosol deposition in vitro and in vivo

This model was designed from CT scans using fused deposition modeling (FDM) of acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) [84]. During the analysis, a respiratory pump was connected to the nasal cavity model so that the airflow was reproduced. The results showed that due to the rough surface, the model is able to cause disruption of drug flow and increase the collision of aerosol droplets. It was also found that the cast geometry was not accurate enough to reproduce aerosol deposition in vivo.

In the in vitro study, two types of nebulizers for drug administration (jet and mesh) and two nasal cavity models, a 3D model and a plastinated cast of the head, were used. Both models were connected to a respiratory pump (Harvard Arraratusch) via rhinopharynx (tidal volume (TV) = 500 ml, inspiratory to expiratory ratio (I/E) = 40/60, 15 breaths/min). A special one-way valve equipped with an absolute filter, a tube (15 cm) and a second absolute filter were placed between the respiratory pump and the model to simulate the soft palate and mouth, trachea, and lungs, respectively. The in vitro experiments were designed to reproduce the in vivo conditions of aerosol administration with both nebulizers: nasal inspiration and mouth breathing with the jet nebulizer and only mouth breathing with the mesh nebulizer.

Nasal cavity model for studying nasal aerosol deposition patterns

A replica of the nasal cavity was created from synthetic polymer epoxy resin using stereolithography based on 3D cadaver files of a 33 y old woman without nasal disease. The nasal part of the model was made of flexible silicone so that the most accurate reproduction of the intranasal insertion was possible [85]. This material enables clear distinction between the hyperdensity of the droplets and the X-ray image of the anatomical structure of the plaster cast.

The aim of the study by Sartoretti et al. was to develop an in vitro approach based on CT combined with the aqueous phase of an iodinated contrast agent (ICA)-labeled nasal spray to qualitatively and quantitatively assess its deposition in the nasal cavity [85]. The results of qualitative and quantitative assessment were processed in free CT image processing programs and showed promise in using this method to analyze drug deposition in the nasal cavity.

Comparative characterization of existing models is given in table 3.

Table 3: Comparative characterization of existing models of the nasal cavity

| Model | Material | 3Dprintingtechnology | Artificialmucosa | Airflow | Conducted studies | Ref. |

| KOKEN-LM005 | Silicone | SLA | Medical lubricant containing physiologically relevant electrolytes | + | -deposition profile of melatonin-loaded pectin/hypromellose microspheres -deposition of in situ gels of fluticasone containing various polymers |

[79, 81–83] |

| Model for comparative study of aerosol deposition in vitro and in vivo | ABS | FDM | - | + | Comparative analysis of aerosol deposition in vitro and in vivo | [84] |

| Model for studying nasal aerosol deposition patterns | Epoxyresin | SLA | - | - | Qualitative and quantitative evaluation of aerosol deposition patterns in vitro | [85] |

Table 4: Expected characteristics of the 3D model of the nasal cavity

| Characteristic | Expected result | Justification | Ref |

| Surface finish | Moderate roughness | Moderate surface roughness allows the model to retain an adequate amount of SNF, thereby enabling a more accurate imitation of physiological conditions | [44, 45] |

| Porosity | Low | Low porosity will maintain the transparency of the model and prevent excessive retention of the tested drug on the surface | [44] |

| Transparency | Not fragile, but flexible enough | Transparency allows for monitoring the distribution of the drug at the time of administration and its behavior over time, as well as facilitates the assessment of the completeness and timing of elimination. | [53] |

| Printing and modeling data | CT scans; mathematical modeling. | The most reliable sources of information for achieving the highest degree of similarity between the model and real anatomical and physiological conditions | [84, 87] |

| Optimal printing technology | Stereolithography (SLA) | Among the described methods, SLA and MJP are the most suitable. SLA was chosen due to its relative cost-effectiveness and the durability of the produced models | [64, 69, 70] |

| Optimal material | Epoxyresin | Meets all the necessary characteristics-transparency, compatibility with SLA, and a surface that can be treated to achieve the required roughness. | [61, 62, 85] |

DISCUSSION

The abundance of printing methods and materials for creating 3D models enables the selection of the most optimal approach for fabricating any three-dimensional model of an internal organ. However, few studies address the issue of assessing the correlation and reliability of data when comparing in vitro models of the nasal cavity with in vivo trials. It is important to note that during the evaluation of nasal drugs in animal models, the medication is rarely sprayed into the nasal cavity; instead, it is typically administered via syringes or pipettes. The anatomical complexity of the nasal cavity and its high interspecies variability render most in vivo animal models unsuitable for studying the deposition of human nasal sprays. Therefore, clinical studies in humans are essential to fully validate the in vivo findings observed in nasal casts and other in vitro experiments [23, 86].

Based on the analyzed 3D printing methods and existing nasal cavity models, it is concluded that the proposed model should have the following characteristics (table 4).

According to the available data, it was determined that the primary test conducted on existing 3D models is the deposition analysis. The potential of this method suggests that other tests can also be reproduced on a geometrically accurate model.

For instance, in a study by Inoue D. et al., the researchers developed a simple dissolution tester to study the bioavailability of solid dosage forms for intranasal administration. The basis for the experiment was a cell printed on a 3D printer. In essence, this system repeats the principle of the Franz diffusion cell used to analyze the release of APIs from mild dosage forms [88]. The printed cell was placed in a medium that mimics the electrolyte composition of the human nasal mucosa. The solid dosage form (powder) still required dissolution in an appropriate volume of solvent before testing. After dissolution, the drug was placed on a semipermeable membrane, where the release of API occurred. This method allows estimation of bioavailability for both solid, mild, and liquid dosage forms.

To ensure that the in vitro model fully replicates all physiological conditions of the nasal cavity, it is necessary to simulate all processes occurring on the mucosa in addition to modeling the geometric features. Constant inhalation and exhalation, mucosal renewal, cilia movement, and mucus secretion can affect the rate of drug elimination from the mucosal surface. Before implementing appropriate equipment, it is necessary to build a mathematical model with preliminary calculations of the rate of mucus secretion, airflow and, other continuous processes in the nasal cavity.

Mucus flow modeling

To fully simulate mucus flow in the nasal cavity, scientists from China have created a computer model to fully account for the effects of mucociliary clearance on drugs. The movement of mucus on the human nasal cavity wall was modeled using computational fluid dynamics, involving the construction of two models: a 2D model with an expanded surface and a 3D surface model of the nasal cavity shell. The models were created using CT scans of a 48-year-old Asian male. As a result of their study, Shang, Y. et al. developed a working model that visualizes the distribution of mucus over the walls of the nasal cavity [87]. The expected outcome of the study was the superiority of the 3D model over the 2D model, which did not provide a sufficiently realistic picture of mucus distribution over the surface of the nasal cavity. Simulation of mucociliary clearance involves simulating the constant movement of cilia with a certain speed and frequency.

Organ-on-a-chiptechnology

In addition to the nasal cavity, various other organs in the human body are lined with mucosal epithelium, which serves both protective and secretory functions. One of the most promising approaches for modeling physiological processes-including nasal-specific phenomena-is the organ-on-a-chip system [89, 90]. Organ-on-a-chip is a microfluidic technology that represents an artificial testing platform closely mimicking the structure and function of human organs. The development of such chips involves culturing specific tissue cells (depending on the organ being modeled) under simulated physiological conditions such as pressure, flow rate, pH, osmotic pressure, nutrient content, and the presence of toxins. Under these conditions, the chip can achieve functional performance analogous to that of the actual organ.

Due to the frequent irrelevance of drug testing results obtained from animal models, there is a growing need to advance microfluidic technologies. Organ-on-a-chip systems offer a promising solution by progressively bridging the gap between in vitro and in vivo experimentation. These devices enable real-time observation of pharmacokinetic processes within a physiologically relevant environment, and the data generated can be utilized to develop mathematical models for predicting drug efficacy [89, 90].

In recent years, a significant number of fundamental studies have been conducted in this field. Organ-on-a-chip technologies have already been developed to model the liver, blood vessels, intestines, nasal cavity, lungs, heart, and even multi-organ systems representing the entire human body. These models provide valuable insights into the effects of pharmaceuticals, pathological conditions, and other external factors on the function of individual organs and systemic physiology [91–98].

From a pharmaceutical perspective, the primary advantage of organ-on-a-chip systems lies in their potential to analyze drug pharmacokinetics with high precision. With continued advancement, these systems may ultimately eliminate the need for pharmacokinetic and even toxicity testing on laboratory animals [98].

3D bioprinting

In addition to modeling techniques and simulated physiological environments, there are methods that allow for the complete reconstruction and utilization of actual biological tissues. The creation of tissues and organs has become feasible through the application of 3D bioprinting technologies. It is important to note that the use of 3D bioprinting extends far beyond organ fabrication. It also holds significant promise in less explored areas, such as the development of drug delivery matrices, the investigation of disease mechanisms, and the creation of personalized medications. Given the most evident limitation of standard 3D printing for organ models-namely, the inability to personalize-bioprinting emerges as a compelling alternative.

In 2023, Derman et al. developed a method for bioprinting nasal epithelium with the goal of tissue reconstruction [99]. The study accounted for a wide array of factors, allowing for the differentiation of five major epithelial cell populations: basal, suprabasal, goblet, club, and ciliated cells. A key advantage of the proposed approach lies in its ability to produce nasal tissue that accurately replicates the structure and function of native nasal epithelium. Furthermore, the findings reaffirm the potential of such systems to serve as a novel and effective tool in the advancement of personalized medicine, enabling the selection of the most appropriate treatment strategies from the earliest stages of disease [99].

Another research group from Spain focused on the challenges of bioprinting scaffolds for the reconstruction of nasal cartilage. Such developments have applications not only in modeling but also in plastic and reconstructive surgery [100]. The use of bioprinting can facilitate the correction of defects and the de novo creation of connective tissues. The integration of two bioprinting advancements-the fabrication of mucosal nasal epithelium and external connective tissue-opens the possibility of constructing a fully biomimetic nose, closely replicating the structural and functional characteristics of the human nasal cavity.

Simulation of continuous breathing

Airflows during inhalation and exhalation can affect the administered dosage form. There are few studies that provide a detailed understanding of airflow in the human airway. The most common approach to modeling airflow is the use of computational fluid dynamics. For instance, Corda et al., and Tan et al., studies used computational fluid dynamics for computer simulation of laminar flows [101, 102].

Another study by Chinese scientists analyzing nasal airflow characteristics in stenosis confirmed that numerical modelling can provide a direct and objective basis for estimating airflow [103]. Although the scientists neglected the effects of temperature and humidity changes in their modeling and replaced air with a liquid in their calculations, they were able to describe the biophysics of nasal airflow in detail.

CONCLUSION

Undoubtedly, 3D modeling offers numerous advantages and serves as an effective approach for addressing challenges that require comprehensive simulation of internal physiological conditions. Owing to these benefits, intranasal dosage forms are increasingly becoming a priority in the development and approval of new pharmaceuticals. Based on the results of the literature review, 3D printing technologies are emerging as a valuable tool for evaluating the properties of intranasal drug delivery systems, enabling the creation of accurate and reproducible models of the nasal cavity. Additive manufacturing allows the selection of materials and methods for printing depending on the specific goals of model construction, allowing flexibility and adaptability of the process. It is important to note that 3D modeling is not a panacea and has a significant drawback–the inability to optimize the model for each individual patient, and averaged data may not be applicable to certain patient groups. However, at the same time, these methods offer unlimited opportunities for simplifying the drug development process and evaluating the quality of pharmaceutical products.

Literature review shows that there is currently one commercially available nasal cavity model, the Koken LM-005, while other models are being developed directly for experimental purposes. Although both anatomical and physiological characteristics of the nasal cavity must be considered to construct a geometrically accurate model, the use of 3D printing remains a promising and effective in vitro method. This confirms the potential of additive manufacturing in providing highly accurate and biorelevant models, which contributes to improved quality assessment of intranasal drug products.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization-Elena Bakhrushina, Iosif Mikhel.; investigation-Iosif Mikhel, Salma Abuelez; resources-Elena Bakhrushina, Iosif Mikhel, Salma Abuelez, Kseniya Eremeeva, Xi Yang; data curation-Elena Bakhrushina, Kseniya Eremeeva, Valeriy Svistushkin, Ivan Krasnyuk Jr., Gleb Zhemerikin, Ivan Krasnyuk; writing-original draft preparation-Iosif Mikhel, Salma Abuelez, Kseniya Eremeeva, Xi Yang; writing-review and editing-Elena Bakhrushina, Valeriy Svistushkin, Olga Stepanova, Gleb Zhemerikin, Ivan Krasnyuk; project administration-Elena Bakhrushina, Iosif Mikhel. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTS

All authors have none to declare.

REFERENCES

Kim H, Lin Y, Tseng TL. A review on quality control in additive manufacturing. Rapid Prototyp J. 2018;24(3):645-69. doi: 10.1108/RPJ-03-2017-0048.

Laffleur F, Bauer B. Progress in nasal drug delivery systems. Int J Pharm. 2021 Sep;607:120994. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.120994, PMID 34390810.

Williams G, Suman JD. In vitro anatomical models for nasal drug delivery. Pharmaceutics. 2022 Jun 26;14(7):1353. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14071353, PMID 35890249.

Barnabas W. Drug targeting strategies into the brain for treating neurological diseases. J Neurosci Methods. 2019 Jan 1;311:133-46. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2018.10.015, PMID 30336221.

Surkova EV, Derkach KV, Bespalov AI, Shpakov AO. Prospects of intranasal insulin for correction of cognitive impairments in particular those associated with diabetes mellitus. Probl Endokrinol (Mosk). 2019 Feb;65(1):57-65. doi: 10.14341/probl9755.

Gizurarson S, Thorvaldsson T, Sigurdsson P, Gunnarsson E. Selective delivery of insulin into the brain: intraolfactory absorption. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 1997 Jan;146(1):135-41. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5173(97)97185-4.

Roque P, Nakadate Y, Sato H, Sato T, Wykes L, Kawakami A. Intranasal administration of 40 and 80 units of insulin does not cause hypoglycemia during cardiac surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Can J Anesth. 2021 Jul 15;68(7):991-9. doi: 10.1007/s12630-021-01969-5.

Rutvik K, Meshva P, Dinal P, Mansi D. The nasal route advanced drug delivery systems and evaluation: a review. Egypt J Chest Dis Tuberc. 2023 Feb;72(4):471-7. doi: 10.4103/ecdt.ecdt_122_22.

Lewis CR, Vo HT, Fishman M. Intranasal naloxone and related strategies for opioid overdose intervention by nonmedical personnel: a review. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2017 Oct;8:79-95. doi: 10.2147/SAR.S101700, PMID 29066940.

Snyder MB, Bregmen DB. SPRIX (ketorolac tromethamine) nasal spray: a novel nonopioid alternative for managing moderate to moderately severe dental pain. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2012 Feb;33(1):2-11. PMID 22428363.

Oskoui M, Pringsheim T, Holler Managan Y, Potrebic S, Billinghurst L, Gloss D. Practice guideline update summary: acute treatment of migraine in children and adolescents: report of the guideline development, dissemination, and implementation subcommittee of the american academy of neurology and the american headache society. Neurology. 2019 Sep 10;93(11):487-99. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000008095, PMID 31413171.

Marmura MJ, Silberstein SD, Schwedt TJ. The acute treatment of migraine in adults: the American Headache Society evidence assessment of migraine pharmacotherapies. Headache. 2015 Jan 20;55(1):3-20. doi: 10.1111/head.12499.

Kalebar RV, Gajare P, SN, Kalebar VU, Aladakatti RH. Synergistic drug compatibility of sumatriptan succinate and metoclopramide hydrochloride (in situ gel formulations) for nasal drug release optimization. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2024 Mar 7;17(3):132-8. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2024v17i3.48485.

Keller LA, Merkel O, Popp A. Intranasal drug delivery: opportunities and toxicologic challenges during drug development. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2022 Apr 25;12(4):735-57. doi: 10.1007/s13346-020-00891-5, PMID 33491126.

Merkus FW, Verhoef JC, Schipper NG, Marttin E. Nasal mucociliary clearance as a factor in nasal drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 1998 Jan;29(1-2):13-38. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(97)00059-8, PMID 10837578.

Casettari L, Illum L. Chitosan in nasal delivery systems for therapeutic drugs. J Control Release. 2014 Sep 28;190:189-200. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.05.003, PMID 24818769.

Alnasser S. A review on nasal drug delivery system and its contribution in therapeutic management. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2019 Jan 7;12(1):40. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2018.v12i1.29443.

Jaiswal PL, Darekar AB, Saudagar RB. A recent review on nasal microemulsion for treatment of cns disorder. Int J Curr Pharm Res. 2017 Jul 14;9(4):5. doi: 10.22159/ijcpr.2017v9i4.20963.

Cecen A, Bayraktar C, Ozgur A, Akgul G, Gunal O. Evaluation of nasal mucociliary clearance time in COVID-19 patients. J Craniofac Surg. 2021 Nov;32(8):e702-5. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000007699, PMID 33935140.

Stringer SP, Stiles W, Slattery WH, Krumerman J, Parsons JT, Mendenhall WM. Nasal mucociliary clearance after radiation therapy. Laryngoscope. 1995 Apr 4;105:380-2. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199504000-00008, PMID 7715382.

Mikhel I, Bakhrushina E, Stepanova O, Prilepskaya S, Kosenkov D, Belyatskaya A. Ribavirin in modern antitumor therapy: prospects for intranasal administration. Curr Drug Deliv. 2024 Aug 26;22(5):510-21. doi: 10.2174/0115672018305548240614113451, PMID 39192644.

Bakhrushina EO, Mikhel JB, Kondratieva VM, Demina NB, Grebennikova TV. In situ gels as a modern method of intranasal vaccine delivery. Vopr Virusol. 2022 Nov 19;67(5):395-402. doi: 10.36233/0507-4088-139, PMID 36515285.

Mikhel IB, Bakhrushina EO, Petrusevich DA, Nedorubov AA, Appolonova SA, Moskaleva NE. Development of an intranasal in situ system for ribavirin delivery: in vitro and in vivo evaluation. Pharmaceutics. 2024 Aug 26;16(9):1125. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics16091125, PMID 39339163.

Kelly JT, Asgharian B, Kimbell JS, Wong BA. Particle deposition in human nasal airway replicas manufactured by different methods. Part I: Inertial regime particles. Aerosol Sci Technol. 2004 Nov;38(11):1063-71. doi: 10.1080/027868290883360.

Shang Y, Inthavong K, Qiu D, Singh N, He F, Tu J. Prediction of nasal spray drug absorption influenced by mucociliary clearance. PLOS One. 2021 Jan 28;16(1):e0246007. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246007, PMID 33507973.

Wong CY, Baldelli A, Tietz O, Van Der Hoven J, Suman J, Ong HX. An overview of in vitro and in vivo techniques for characterization of intranasal protein and peptide formulations for brain targeting. Int J Pharm. 2024 Apr;654:123922. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2024.123922, PMID 38401871.

Deruyver L, Rigaut C, Lambert P, Haut B, Goole J. The importance of pre-formulation studies and of 3D-printed nasal casts in the success of a pharmaceutical product intended for nose-to-brain delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2021 Aug;175:113826. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2021.113826, PMID 34119575.

Bakhrushina EO, Demina NB, Shumkova MM, Rodyuk PS, Shulikina DS, Krasnyuk II. In situ intranasal delivery systems: application prospects and main pharmaceutical aspects of development. Drug Dev Regist. 2021 Nov 25;10(4):54-63. doi: 10.33380/2305-2066-2021-10-4-54-63.

Bakhrushina EO, Shulikina DS, Mikhel IB, Demina NB, Krasnyuk II. Development and aprobation of in vitro model of nasal cavity for stanadartisation of in situ drug delivery systems. Proceedings of the Voronezh State University. 2023;4:83-91.

Valtonen O, Ormiskangas J, Kivekas I, Rantanen V, Dean M, Poe D. Three-dimensional printing of the nasal cavities for clinical experiments. Sci Rep. 2020 Jan 16;10(1):502. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-57537-2, PMID 31949270.

Butler J, Hens B, Vertzoni M, Brouwers J, Berben P, Dressman J. In vitro models for the prediction of in vivo performance of oral dosage forms: recent progress from partnership through the IMI OrBiTo collaboration. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2019 Mar;136:70-83. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2018.12.010, PMID 30579851.

Andreas CJ, Chen YC, Markopoulos C, Reppas C, Dressman J. In vitro biorelevant models for evaluating modified-release mesalamine products to forecast the effect of formulation and meal intake on drug release. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2015 Nov;97(A):39-50. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2015.09.002, PMID 26391972.

Sobiesk JL, Munakomi S. Anatomy head and neck nasal cavity. StatPearls; 2025.

Ogle OE, Weinstock RJ, Friedman E. Surgical anatomy of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2012 May;24(2):155-66. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2012.01.011, PMID 22386856.

Butaric LN, Nicholas CL, Kravchuk K, Maddux SD. Ontogenetic variation in human nasal morphology. Anat Rec (Hoboken). 2022 Aug 22;305(8):1910-37. doi: 10.1002/ar.24760, PMID 34549897.

Hamilton GS. The external nasal valve. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2017 May;25(2):179-94. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2016.12.010, PMID 28340649.

Van Valkenburgh B, Smith TD, Craven BA. Tour of a labyrinth: exploring the vertebrate nose. Anat Rec (Hoboken). 2014 Nov 14;297(11):1975-84. doi: 10.1002/ar.23021, PMID 25312359.

Patki A, Frank Ito DO. Characterizing human nasal airflow physiologic variables by nasal index. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2016 Oct;232:66-74. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2016.07.004, PMID 27431449.

Taylor DJ, Doorly DJ, Schroter RC. Airflow in the human nasal cavity: an inter-subject comparison. In: Proceedings of the ASME summer bioengineering conference, SBC2009; 2009. doi: 10.1115/SBC2009-206459.

Tian L, Dong J, Shang Y, Tu J. Detailed comparison of anatomy and airflow dynamics in human and cynomolgus monkey nasal cavity. Comput Biol Med. 2022 Feb;141:105150. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2021.105150, PMID 34942396.

Salade L, Wauthoz N, Goole J, Amighi K. How to characterize a nasal product. The state of the art of in vitro and ex vivo specific methods. Int J Pharm. 2019 Apr;561:47-65. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2019.02.026, PMID 30822505.

Rabinowicz AL, Carrazana E, Maggio ET. Improvement of intranasal drug delivery with intravail® alkylsaccharide excipient as a mucosal absorption enhancer aiding in the treatment of conditions of the central nervous system. Drugs RD. 2021 Dec 25;21(4):361-9. doi: 10.1007/s40268-021-00360-5, PMID 34435339.

Ho M, Goldfarb J, Moayer R, Nwagu U, Ganti R, Krein H. Design and printing of a low cost 3D-printed nasal osteotomy training model: development and feasibility study. JMIR Med Educ. 2020 Nov 17;6(2):e19792. doi: 10.2196/19792, PMID 33200998.

Godec D, Gonzalez Gutierrez J, Nordin A, Pei E, Urena J. A guide to additive manufacturing. Springer Tracts in Additive Manufacturing; 2022. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-05863-9.

Subramaniam Ravi P, Richardson Regina B, Kevin MT, Kimbell Julia S, Guilmette Raymond A. Computational fluid dynamics simulations of inspiratory airflow in the human nose and nasopharynx. Inhal Toxicol. 1998 Jan;10(2):91-120.

Shubber S, Vllasaliu D, Rauch C, Jordan F, Illum L, Stolnik S. Mechanism of mucosal permeability enhancement of criticalsorb® (Solutol® HS15) investigated in vitro in cell cultures. Pharm Res. 2015 Feb 5;32(2):516-27. doi: 10.1007/s11095-014-1481-5, PMID 25190006.

Ladel S, Schlossbauer P, Flamm J, Luksch H, Mizaikoff B, Schindowski K. Improved in vitro model for intranasal mucosal drug delivery: primary olfactory and respiratory epithelial cells compared with the permanent nasal cell line RPMI 2650. Pharmaceutics. 2019 Aug 1;11(8):367. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics11080367, PMID 31374872.

Thakkar SG, Warnken ZN, Alzhrani RF, Valdes SA, Aldayel AM, Xu H. Intranasal immunization with aluminum salt-adjuvanted dry powder vaccine. J Control Release. 2018 Dec;292:111-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2018.10.020, PMID 30339906.

Sawant N, Donovan MD. In vitro assessment of spray deposition patterns in a pediatric (12 y old) nasal cavity model. Pharm Res. 2018 May 26;35(5):108. doi: 10.1007/s11095-018-2385-6, PMID 29582159.

Porfiryeva NN, Zlotver I, Davidovich Pinhas M, Sosnik A. Mucus mimicking mucin-based hydrogels by tandem chemical and physical crosslinking. Macromol Biosci. 2024 Jul 28;24(7):e2400028. doi: 10.1002/mabi.202400028, PMID 38511568.

Eshel Green T, Eliyahu S, Avidan Shlomovich S, Bianco Peled H. PEGDA hydrogels as a replacement for animal tissues in mucoadhesion testing. Int J Pharm. 2016 Jun;506(1-2):25-34. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2016.04.019, PMID 27084292.

Hall DJ, Khutoryanskaya OV, Khutoryanskiy VV. Developing synthetic mucosa mimetic hydrogels to replace animal experimentation in the characterisation of mucoadhesive drug delivery systems. Soft Matter. 2011;7(20):9620. doi: 10.1039/c1sm05929g.

Su J, Liu Y, Sun H, Naeem A, Xu H, Qu Y. Visualization of nasal powder distribution using biomimetic human nasal cavity model. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2024 Jan;14(1):392-404. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2023.06.007, PMID 38261815.

Hartigan DR, Adelfio M, Shutt ME, Jones SM, Patel S, Marchand JT. In vitro nasal tissue model for the validation of nasopharyngeal and midturbinate swabs for SARS-CoV-2 testing. ACS Omega. 2022 Apr 12;7(14):12193-201. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.2c00587, PMID 35449955.

Konta AA, Garcia Pina M, Serrano DR. Personalised 3D printed medicines: which techniques and polymers are more successful? Bioengineering (Basel). 2017 Sep 22;4(4):79. doi: 10.3390/bioengineering4040079, PMID 28952558.

Sastri V. Other polymers: styrenics silicones thermoplastic elastomers biopolymers and thermosets; 2022. p. 287-342.

Yu W, Sun L, Li M, Li M, Lei W, Wei C. FDM 3D printing and properties of PBS/PLA blends. Polymers (Basel). 2023 Nov 2;15(21):4305. doi: 10.3390/polym15214305, PMID 37959985.

Tyler B, Gullotti D, Mangraviti A, Utsuki T, Brem H. Polylactic acid (PLA) controlled delivery carriers for biomedical applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2016 Dec;107:163-75. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2016.06.018, PMID 27426411.

Ligon SC, Liska R, Stampfl J, Gurr M, Mulhaupt R. Polymers for 3D printing and customized additive manufacturing. Chem Rev. 2017 Aug 9;117(15):10212-90. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00074, PMID 28756658.

Ulery BD, Nair LS, Laurencin CT. Biomedical applications of biodegradable polymers. J Polym Sci B Polym Phys. 2011 Jun 15;49(12):832-64. doi: 10.1002/polb.22259, PMID 21769165.

Naydenova I, Nazarova D, Babeva T, editors. Holographic materials and optical systems. InTech; 2017.

Peerzada M, Abbasi S, Lau KT, Hameed N. Additive manufacturing of epoxy resins: materials methods and latest trends. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2020 Feb;59(14):6375-90. doi: 10.1021/acs.iecr.9b06870.

Kim GB, Lee S, Kim H, Yang DH, Kim YH, Kyung YS. Three-dimensional printing: basic principles and applications in medicine and radiology. Korean J Radiol. 2016 Feb;17(2):182-97. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2016.17.2.182, PMID 26957903.

Salmi M. Additive manufacturing processes in medical applications. Materials (Basel). 2021 Jan 3;14(1):191. doi: 10.3390/ma14010191, PMID 33401601.

Martinez Garcia A, Monzon M, Paz Hernandez R. Standards for additive manufacturing technologies; 2021. p. 395-408.

Mwema F, Akinlabi E. Basics of fused deposition modelling (FDM); 2020. p. 1-15.

Grivet Brancot A, Boffito M, Ciardelli G. Use of polyesters in fused deposition modeling for biomedical applications. Macromol Biosci. 2022 Oct 22;22(10):e2200039. doi: 10.1002/mabi.202200039, PMID 35488769.

Warnken ZN, Smyth HD, Davis DA, Weitman S, Kuhn JG, Williams RO. Personalized medicine in nasal delivery: the use of patient-specific administration parameters to improve nasal drug targeting using 3D-printed nasal replica casts. Mol Pharm. 2018 Apr 2;15(4):1392-402. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.7b00702, PMID 29485888.

Deshmane S, Kendre P, Mahajan H, Jain S. Stereolithography 3D printing technology in pharmaceuticals: a review. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2021 Sep 2;47(9):1362-72. doi: 10.1080/03639045.2021.1994990, PMID 34663145.

Kumar H, Kim K. Stereolithography 3D bioprinting. Methods Mol Biol. 2020;2140:93-108. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-0520-2_6, PMID 32207107.

Charoo NA, Barakh Ali SF, Mohamed EM, Kuttolamadom MA, Ozkan T, Khan MA. Selective laser sintering 3D printing an overview of the technology and pharmaceutical applications. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2020 Jun 2;46(6):869-77. doi: 10.1080/03639045.2020.1764027, PMID 32364418.

Gao B, Zhao H, Peng L, Sun Z. A review of research progress in selective laser melting (SLM). Micromachines (Basel). 2022 Dec 25;14(1):57. doi: 10.3390/mi14010057, PMID 36677118.

Laverty DP, Thomas MB, Clark P, Addy LD. The use of 3D metal printing (direct metal laser sintering) in removable prosthodontics. Dent Update. 2016 Nov 2;43(9):826-35. doi: 10.12968/denu.2016.43.9.826, PMID 29152953.

Gokuldoss PK, Kolla S, Eckert J. Additive manufacturing processes: selective laser melting electron beam melting and binder jetting selection guidelines. Materials (Basel). 2017 Jun 19;10(6):672. doi: 10.3390/ma10060672, PMID 28773031.

Raz K, Chval Z, Thomann S. Minimizing deformations during HP MJF 3D printing. Materials (Basel). 2023 Nov 28;16(23):7389. doi: 10.3390/ma16237389, PMID 38068133.

Awad A, Fina F, Goyanes A, Gaisford S, Basit AW. Advances in powder bed fusion 3D printing in drug delivery and healthcare. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2021 Jul;174:406-24. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2021.04.025, PMID 33951489.

Kusoglu IM, Donate Buendia C, Barcikowski S, Gokce B. Laser powder bed fusion of polymers: quantitative research direction indices. Materials (Basel). 2021 Mar 2;14(5):1169. doi: 10.3390/ma14051169, PMID 33801512.

Taczala J, Czepulkowska W, Konieczny B, Sokolowski J, Kozakiewicz M, Szymor P. Comparison of 3D printing MJP and FDM technology in dentistry. Arch Mater Sci Eng. 2020 Feb;1(101):32-40. doi: 10.5604/01.3001.0013.9504.

Kundoor V, Dalby RN. Assessment of nasal spray deposition pattern in a silicone human nose model using a color based method. Pharm Res. 2010 Jan 10;27(1):30-6. doi: 10.1007/s11095-009-0002-4, PMID 19902337.

Nizic Nodilo L, Perkusic M, Ugrina I, Spoljaric D, Jakobusic Brala C, Amidzic Klaric D. In situ gelling nanosuspension as an advanced platform for fluticasone propionate nasal delivery. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2022 Jun;175:27-42. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2022.04.009, PMID 35489667.

Castile J, Cheng YH, Simmons B, Perelman M, Smith A, Watts P. Development of in vitro models to demonstrate the ability of PecSys®, an in situ nasal gelling technology, to reduce nasal run-off and drip. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2013 May 17;39(5):816-24. doi: 10.3109/03639045.2012.707210, PMID 22803832.

Djupesland PG, Messina JC, Mahmoud RA. Role of nasal casts for in vitro evaluation of nasal drug delivery and quantitative evaluation of various nasal casts. Ther Deliv. 2020 Aug 30;11(8):485-95. doi: 10.4155/tde-2020-0054, PMID 32727298.

Nizic L, Potas J, Winnicka K, Szekalska M, Erak I, Gretic M. Development characterisation and nasal deposition of melatonin loaded pectin/hypromellose microspheres. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2020 Jan;141:105115. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2019.105115, PMID 31654755.

Le Guellec S, Le Pennec D, Gatier S, Leclerc L, Cabrera M, Pourchez J. Validation of anatomical models to study aerosol deposition in human nasal cavities. Pharm Res. 2014 Jan 25;31(1):228-37. doi: 10.1007/s11095-013-1157-6, PMID 24065586.

Sartoretti T, Mannil M, Biendl S, Froehlich JM, Alkadhi H, Zadory M. In vitro qualitative and quantitative CT assessment of iodinated aerosol nasal deposition using a 3D-printed nasal replica. Eur Radiol Exp. 2019 Dec 21;3(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s41747-019-0113-6, PMID 31432300.

Le Guellec S, Ehrmann S, Vecellio L. In vitro in vivo correlation of intranasal drug deposition. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2021 Mar;170:340-52. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2020.09.002, PMID 32918968.

Shang Y, Inthavong K, Tu J. Development of a computational fluid dynamics model for mucociliary clearance in the nasal cavity. J Biomech. 2019 Mar;85:74-83. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2019.01.015, PMID 30685195.

Iliopoulos F, Caspers PJ, Puppels GJ, Lane ME. Franz cell diffusion testing and quantitative confocal raman spectroscopy: in vitro in vivo correlation. Pharmaceutics. 2020 Sep 18;12(9):887. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics12090887, PMID 32961857.

Ingber DE. Human organs on chips for disease modelling drug development and personalized medicine. Nat Rev Genet. 2022 Aug 25;23(8):467-91. doi: 10.1038/s41576-022-00466-9, PMID 35338360.

Izadifar Z, Sontheimer Phelps A, Lubamba BA, Bai H, Fadel C, Stejskalova A. Modeling mucus physiology and pathophysiology in human organs-on-chips. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2022 Dec;191:114542. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2022.114542, PMID 36179916.

Nalayanda DD, Puleo C, Fulton WB, Sharpe LM, Wang TH, Abdullah F. An open access microfluidic model for lung-specific functional studies at an air-liquid interface. Biomed Microdevices. 2009 Oct 30;11(5):1081-9. doi: 10.1007/s10544-009-9325-5, PMID 19484389.

Lee SA, No DY, Kang E, Ju J, Kim DS, Lee SH. Spheroid-based three-dimensional liver-on-a-chip to investigate hepatocyte hepatic stellate cell interactions and flow effects. Lab Chip. 2013;13(18):3529-37. doi: 10.1039/c3lc50197c, PMID 23657720.

Yoon No D, Lee KH, Lee J, Lee SH. 3D liver models on a microplatform: well-defined culture engineering of liver tissue and liver-on-a-chip. Lab Chip. 2015;15(19):3822-37. doi: 10.1039/c5lc00611b, PMID 26279012.

Bavli D, Prill S, Ezra E, Levy G, Cohen M, Vinken M. Real-time monitoring of metabolic function in liver-on-chip microdevices tracks the dynamics of mitochondrial dysfunction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016 Apr 19;113(16):E2231-40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1522556113, PMID 27044092.

Gunther A, Yasotharan S, Vagaon A, Lochovsky C, Pinto S, Yang J. A microfluidic platform for probing small artery structure and function. Lab Chip. 2010;10(18):2341-9. doi: 10.1039/c004675b, PMID 20603685.

Cheng W, Klauke N, Sedgwick H, Smith GL, Cooper JM. Metabolic monitoring of the electrically stimulated single heart cell within a microfluidic platform. Lab Chip. 2006;6(11):1424-31. doi: 10.1039/b608202e, PMID 17066165.

Sin A, Chin KC, Jamil MF, Kostov Y, Rao G, Shuler ML. The design and fabrication of three-chamber microscale cell culture analog devices with integrated dissolved oxygen sensors. Biotechnol Prog. 2004;20(1):338-45. doi: 10.1021/bp034077d, PMID 14763861.

Afonicheva PK, Bulyanitsa AL, Evstrapov AA. Organ-on-a-chip materials and methods of creation. NP. 2019;29(4):3-18. doi: 10.18358/np-29-4-i318.

Derman ID, Yeo M, Castaneda DC, Callender M, Horvath M, Mo Z. High throughput bioprinting of the nasal epithelium using patient-derived nasal epithelial cells. bioRxiv. 2023 Aug 14;15(4):2023.03.29.534723. doi: 10.1101/2023.03.29.534723, PMID 37034627.

Chiesa Estomba CM, Aiastui A, Gonzalez Fernandez I, Hernaez Moya R, Rodino C, Delgado A. Three-dimensional bioprinting scaffolding for nasal cartilage defects: a systematic review. Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2021 Jun 17;18(3):343-53. doi: 10.1007/s13770-021-00331-6, PMID 33864626.

Corda JV, Shenoy BS, Ahmad KA, Lewis L, KP, Khader SM. Nasal airflow comparison in neonates infant and adult nasal cavities using computational fluid dynamics. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2022 Feb;214:106538. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2021.106538, PMID 34848078.

Tan J, Han D, Wang J, Liu T, Wang T, Zang H. Numerical simulation of normal nasal cavity airflow in Chinese adult: a computational flow dynamics model. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2012 Mar 22;269(3):881-9. doi: 10.1007/s00405-011-1771-z, PMID 21938528.

Wang T, Chen D, Wang PH, Chen J, Deng J. Investigation on the nasal airflow characteristics of anterior nasal cavity stenosis. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2016;49(9):e5182. doi: 10.1590/1414-431X20165182, PMID 27533764.