Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 4, 2025, 91-116Review Article

BEYOND NEEDLES: INNOVATIONS IN TRANSDERMAL ANTIBIOTIC DELIVERY SYSTEMS

RAWANDM DAGHMASDa*, SHEREEN M. ASSAFb

aFaculty of Pharmacy, Middle East University, Amman, Jordan. bJordan University of Science and Technology, Irbid, Jordan

*Corresponding author: Rawandm Daghmasd; *Email: r.daghmash@meu.edu

Received: 09 Mar 2025, Revised and Accepted: 20 May 2025

ABSTRACT

As a substitution to traditional needle injections, other non-invasive treatments have lately evolved. Transdermal Drug Delivery Systems (TDDS) are the most appealing of these methods due to their low rejection rate, exceptional simplicity of application, and superior efficiency and endurance among patients. Because this strategy primarily includes local administration, it can could minimize local drug concentration accumulation and broad-spectrum drug distribution to tissues not specifically targeted by the medication. Furthermore, the physicochemical features of the skin translate to several hurdles and limitations in transdermal distribution, necessitating various studies to address these bottlenecks. In this study, we explain the many types of accessible TDDS approaches for delivering antibiotics, as well as a critical evaluation of each method's individual merits and limitations, characterization methodologies, and potential. Advancements in research on these alternative technologies are mentioned in this review.

Keywords: Transdermal antibiotics, Transdermal drug delivery system advantages, Limitations, Microneedles, Characterization

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i4.54157 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

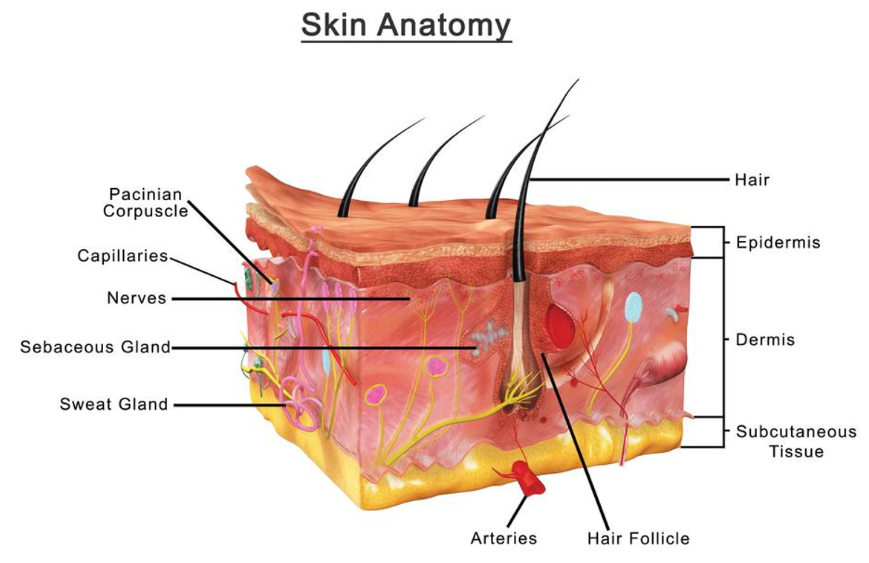

Skin is the outer lipid the body's layer, having a thickness about 2–3 mm [1, 2]. Aside from serving as a barrier, it also aids in the absorption of numerous medicinal and non-therapeutic substances [3]. The epidermis and the underlying dermis are two skin layers that play a vital role in percutaneous absorption. The hypodermis, or subcutaneous adipose tissue layer, serves as the primary food store, as well as offers a physical protection and thermal insulation. Stratum lies under the dermis and connects it to the underlying structures [4-7]. The cutaneous appendages, which cover just around 0.1 percent of the skin's surface, are made up of hair shafts and sebum glands, as well as sweat glands (eccrine and apocrine) [8, 9]. They provide crucial physiological activities and may also play a role in chemical transport through the skin [4-7]. Fig. 1 representing the anatomy of human skin.

The dermis is a complex structure that contains diverse cell types, including fibroblasts, endothelial cells, nerve cells, mast cells, endothelial cells, nerve cells, and blood cells [4-7]. In humans, this layer, which is primarily made of connective tissue, with a thickness ranges from 3–5 mm and contains important skin structures such as blood capillaries, a lymphatic network, and a network of sensory nerves [10, 11]. When a molecule is applied topically, it can permeate into the dermis layer and enter the central blood circulation [12]. The dermal vasculature provides sink conditions for a penetrant while also acting as a driving factor for percutaneous absorption. The epidermis is a multilayered membrane that has two compartments: the outermost Stratum Corneum (SC) layer and the viable epidermis [10, 12]. The basal epidermal layer produces epidermal cells (or keratinocytes), which migrate to the skin's surface. The epidermis is composed of melanocytes, Langerhans cells, migratory macrophages, and lymphocytes [10, 12-14]. The major obstacle to percutaneous absorption is located in the skin's outer layer, also known as the horny layer [10, 12]. The SC layer is roughly 10–20 µm thick and has a key plays an important function in preventing the movement of water and xenobiotics. The SC cells, known as corneocytes, are regularly supplied by the gradual upward migration of cells generated by the viable epidermis's bottom layer. Corneocytes are hexagonal anucleate cells made of insoluble keratins surrounded by crosslinked proteins and immersed in an intercellular lipid domain. Because the living skin layers and blood vessels are highly permeable and the peripheral circulation is relatively fast, and the rate-limiting step is the SC diffusion. Since SC cells are thought to be dead and have no metabolic action, diffusion across the stratum corneum is passive guided by physical and chemical rules. The composition and structure of SC can explain its barrier properties. The SC structure may be represented as a model of bricks (corneocytes) and mortar (intercellular lipids) [5]. The intercellular lipid domain is the sole continuous area in the stratum corneum [15, 16]. Ceramids, free fatty acids, cholesterol, and cholesterol esters are the primary components of intercellular lipids [17]. The structure of the lipid domains is thought to be critical for skin barrier function. The lack of phospholipids, which separates SC from other biological membranes, is a notable property of SC [4, 17]. The skin's extraordinary barrier characteristics are due to the SC's particular composition, which prevents the passage of highly polar, ionic, and macromolecules substances. Highly lipophilic compounds that quickly partition into the SC, on the other hand, do not easily diffuse into the hydrophilic epidermis and dermis, and their clearance is slowed [6].

Hair follicles, for example, are skin appendages supported by the dermis and may be responsible for passive medicine absorption via the transdermal route (fig. 1) [18]. Because substances like therapeutic agents may move into the systemic circulation immediately after passing the skin, this method has attracted pharmaceutical experts to conduct drug delivery studies for the previous twenty years [19]. Because of the avoidance of dosage variations, first-pass metabolized in the liver, and enhanced bioavailability, the transdermal route is regarded a preferable option than oral route of drug administration [20]. Due to being non-invasive and the simplicity of distribution of the drug, this enhances patient compliance [21]. Various issues should be addressed when designing transdermal drug delivery systems, such as the epidermal barrier, which only permits lipophilic substances with a molecular weights below 500 kDa (kilodaltons) to pass through [22]. The rate of drug entry over this barrier is extremely sluggish. However, efficient delivery of hydrophilic medicines via the skin remains a difficult challenge [23]. Also, skin is capable of absorption and excretion, as well as selectively transmitting chemical compounds required for bodily hemostasis.

Transdermal delivery is divided into two types: active and passive. Active approaches disturb the stratum corneum, while passive methods modulate drug-vehicle interactions to promote skin diffusion. Transdermal drug delivery technologies, including electroporation, phonophoresis, and laser-assisted procedures, enhance medication absorption and bioavailability by overcoming the skin's natural barrier [24, 25]. Studies had showed that Niosomes have the ability to improve drug solubility, bioavailability, and release, making them helpful in pharmaceutical applications [26].

Since the extensive antibiotics use began in the 1940s, concomitant Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) became a source of concern, due to the significant morbidity and mortality [27]. AMR has grown into a major hazard to worldwide global health, and controlling it is a top focus for public health officials [28].

gut microbiome is considered as an important AMR preventative factor by enhancing host colonization resistance [29, 30]. Alteration in taxonomic content have been linked to increased vulnerability to a variety of diseases, comprising diabetes, obesity, liver illness, colon cancer, and Inflammatory Bowel (IBD) [31-33].

Antibiotics has a major influence on the makeup of the gut microbiome, resulting in a significant decrease in the microbiota's taxonomic abundance and multiplicity diversity [34, 35]. The extensive use of antibiotics can lead to prolonged chronic infections such as vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) and Clostridium difficile, and bowel colonization is acknowledged to lead bloodstream infections in vulnerable people [36-39]. Due to antibiotic treatment, dysbiosis in the gut microbiome has been linked to a variety of disorders in neonates and preterm newborns, including allergies, asthma, atopy, obesity, and abnormalities with brain development [40, 41].

Gut identified as a key pool for Antimicrobial Resistance Genes (ARGs), that pass in feces and so, they contribute to the antibiotic resistome of other environments [42-44]. Geographic variations in antibiotic resistomes of fecal material support the link among antibiotic usage and the evolution of resistance through the gut. ARG profiles from various nations correspond with antibiotic usage in particular locations, both in terms of antibiotic type and quantity of antibiotic utilized. The longer the duration of use of antibiotics clinically, like cephalosporins and tetracycline the more ARGs [42, 45].

The detected dysbiosis and fast accumulation of ARGs emerge from an antibiotic challenge to gut microbes, leading in enhanced buildup and transmission of these genes [46]. The mutations are more noticeable with increased concentrations of antibiotic exposure in the stomach, which is largely determined by dosage, length of therapy, and, importantly, mode of administration of the antimicrobial drug. Decreasing the quantity of antibiotic that enters the stomach is likely to reduce AMR advancement. As a result, medication delivery mode, particularly patient-convenient delivery methods that limit unnecessary antibiotic exposure to the gut microbiota, should be addressed as a major tactic, which is a smaller segment of larger antimicrobial stewardship program. The field of AMR is at a crossroads. This rising issue quickly turns into a disaster, and significant antimicrobial stewardship efforts are required to protect world health. The manner in which antibiotics are administered might be a crucial component of any such program, and medication delivery mechanisms play a vital role in the battle against AMR. Numerous studies have investigated transdermal administration techniques for antibiotics, which could enhance therapeutic results and possibly slow the emergence of AMR: such as Microemulsion-Based Bacteriophage Transdermal administration: Using a microemulsion technology, an ex vivo and in vivo investigation examined the transdermal administration of a T4 bacteriophage specific to Escherichia coli. According to the results, this method might be a useful substitute for conventional antibiotic therapy in the treatment of bacterial infections [47]. Dissolving Microneedle Arrays for Gentamicin Delivery: Studies on the transdermal administration of gentamicin using dissolving microneedle arrays showed promise in the treatment of neonatal sepsis. This technique might offer a less invasive way to give antibiotics, which could increase compliance and decrease misuse [47]. Vancomycin Hydrochloride Nano-Ethosomes and Iontophoresis: A study investigated the use of iontophoresis and nano-ethosomes in conjunction to improve transdermal delivery of vancomycin hydrochloride. Better medication penetration and bioavailability were shown by the in vitro and in vivo studies, indicating a potential substitute for traditional delivery methods [47]. Vancomycin Hydrochloride Polymeric Microarray Patches: The creation and assessment of polymeric microarray patches for transdermal administration of vancomycin hydrochloride revealed encouraging pharmacokinetic characteristics. This strategy might make dosing more constant and possibly lower the chance that resistance will arise as a result of inadequate dosage [47]. Although these trials demonstrate novel transdermal delivery strategies for antibiotics, more clinical investigations are required to prove a link between TDDS and a decrease in the emergence of AMR. More conclusive proof that transdermal antibiotic distribution is an important part of AMR prevention would come from extensive clinical trials evaluating the long-term effects of this approach on resistance trends [47].

The claim that TDDS can prevent antibiotic resistance by reducing disruptions to the gut flora is now being investigated. There are currently few direct comparative clinical studies examining microbiome changes in people treated with TDDS versus oral antibiotics. However, indirect data suggests that the method of antibiotic delivery may impact gut microbiota makeup. For example, a study published in Nature found that neonates who were directly treated with antibiotics had lower amounts of good gut bacteria, such as Bifid bacterium, which led to worse immunological responses to immunizations later in infancy. This effect was not detected in newborns whose mothers were given antibiotics during birth, implying that direct antibiotic exposure had a greater influence on the infant gut flora [48]. While this study does not directly compare TDDS to oral antibiotic delivery, it does highlight the importance of antibiotic exposure pathways for gut microbiota integrity. Transdermal administration skips the gastrointestinal route, which may reduce direct interactions with gut flora. As a result, it is likely that TDDS could attenuate gut microbiome disruptions caused by oral antibiotics, potentially lowering the development of antibiotic resistance connected to microbiome imbalances. Additional research is required to support this notion. Comparative clinical research comparing microbiota changes in TDDS patients against those receiving oral antibiotics would give more conclusive data about the influence of transdermal delivery on gut microbiome composition and its involvement in antibiotic resistance prevention [48].

This review focuses on antibiotic transdermal delivery techniques that manage to prevent AMR. These precautions include avoiding the stomach and adopting customized delivery routes, as well as reducing avoidable antimicrobial challenge that might cause development of AMR.

This review will cover the advantages of TDDS, challenges faced while using TDDS, transdermal delivery of antibiotics, new technologies used for transdermal antibiotics delivery, and characterization methods.

Search criteria

A thorough literature search was conducted using predetermined keywords to find all pertinent articles published up to 2025 in Web of Science (http://www.webofknowledge.com), ResearchGate (https://www.researchgate.net), PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), and Google Scholar (https://scholar.google.com). Both phrase and text words were used. Among the most popular terms were “Transdermal antibiotics, Transdermal drug delivery system advantages, Limitations, Microneedles, and lastly Characterization of Transdermal drug delivery systems ".

Transdermal drug delivery system (TDDS) advantages

TDD provides offers huge advantages including: bypassing the gastrointestinal tract, and thus, eliminating the effect of the first pass metabolism, no interference with the PH, enzymes, and the bacteria of the intestine, so this will enhance the bioavailability [50-52], and this had been supported by the study which investigated the transdermal administration of vancomycin hydrochloride utilizing nano-ethosomes and iontophoresis. The study found a maximal transdermal flow of 550 µg/cm²/h, demonstrating efficient systemic administration. In vivo tests revealed equivalent bacterial count decreases between intramuscular and transdermal injection, implying similar treatment efficacy [53]. Also, a study of a cationic nanoemulsion gel for transdermal administration of rifampicin indicated considerable improvements in pharmacokinetic characteristics. The study found a 4.34-fold rise in Maximum Plasma Concentration (Cmax) and a 4.74-fold increase in Area Under The Curve (AUC) when compared to oral delivery, showing significantly increased bioavailability [54]. Furthermore, a study looked into the usage of transfersomal nanoparticles for transdermal delivery of clindamycin phosphate. The data revealed a much larger cumulative amount of medication penetration and flux than typical gel formulations, implying improved transdermal absorption [55].

A more uniformly distributed plasma levels of molecules, and a decrease frequency of dosing due to prolongation the duration of action, so, this will lead to a reduction in side effects, as well as, maintaining a more stable plasma concentrations, so this will improve therapy, decreasing in first-pass drug metabolism. Furthermore, a reduction in the side effect, which might be due to the continual usage of medication, such as, liver damage or renal failure [56]. Using TDDS enhances the compliance of the patients by eliminating of the bad taste of the antibiotics. TDDS are often less expensive on a monthly basis when compared to conventional methods, as patches aim to administer medications for 1 to 7 d. Another advantage of TDDS is that with programmable systems, multiple dosage dosing, when needed or at different rate drug administration is conceivable, adding extra benefits to traditional patch dosage forms [57, 58].

Fig. 1: A graph representing the anatomy of human skin[49]

Challenges faced while using transdermal drug delivery system

Skin permeation

Because of the specific environment of the epidermal skin layer, only a limited number of medicines may be given for systemic therapy meaningful rates. The whole section of the transdermal medication industry is made up of about 15 medicines. Aside from high potency, the physicochemical properties of drugs that are frequently cited as beneficial for percutaneous administration they comprise of modest hydrophobicity and low molecular weight [59]. However, a significant proportion of pharmacological substances do not fit these standards. This is more accurate for macromolecules such as insulin, human growth hormone, or cyclosporine, which pose significant drug delivery challenges. Overcoming poor skin miscibility to xenobiotics can be accomplish through a number of methods, and this is an active area of research. Their efficacy and applicability will differ based on the physicochemical nature of the component. So, skin permeability can be solved by either chemical method, physical methods, and a prodrug approach [59].

Overcoming the skin permeation barrier: challenges and solutions

Due to the unique properties of the epidermal layer, the choice of medicines that can be given systemically are restricted to a few. Potency and physicochemical properties are important features to study when the drug is chosen for percutaneous administration. Some of the physicochemical properties include adequate lipophilicity and small size (low molecular weight). Many drugs do not comply with these needs. The techniques of how to overcome bad skin permeability are an area for research. According to the physicochemical properties of the xenobiotics, the efficacy and applicability are determined [59].

Chemical methods

Permeation enhancers improve drug penetration over epidermis by two mechanisms: either by boosting drug partitioning into the stratum corneum's barrier region, or, they increase drug diffusivity in this region, or by both mechanisms [60]. It is known that stratum corneum is made of up multilamellar layers, which compose of intercellular continuous lipid ‘mortar' and keratin 'bricks' [61-63]. Medication nature plays a major role in permeation and of which these two mechanisms might influence the percutaneous transport (rate limiting). As a result, it is expected that the extent of permeability enhancement acquired with a particular permeation enhancer will differ amongst lipophilic and hydrophilic medicines. Many mechanisms are involved in enhancing skin permeation by increasing the humidity of stratum corneum, extracting intercellular lipids, enhancing drug thermodynamic action, increasing stratum corneum hydration, altering proteinaceous corneocyte composition [64, 65]. Permeation enhancers are traditionally classified into categories depend on the chemical structure more than their method of activity. This is owing in part to the lack of ability in in distinguishing whether they have a main or multiple method of activity. Furthermore, chemicals from the same class might exert their impact via several methods. More than 300 chemicals have been found to be skin permeability enhancers.

Enhancers are divided into categories: Alcohols such as, ethanol, pentanol, lauryl alcohol, benzyl alcohol, glycerol, and propylene glycols. Amines such as, diethanolamine and triethanolamine. Esters such as, ethyl acetate, isopropyl palmitate, and isopropyl myristate. Fatty acids such as, valeric acid, linoleic acid, oleic acid, and lauric acid. Amides such as, pyrrolidone derivatives, 1-dodecylazacycloheptane-2-one[Azone®]urea, dimethylacetamide, and dimethylformamide. Surfactants such as, sodium laureate, cetyltrimethylammonium bromide, Brij®, Tween® and sodium cholate. Hydrocarbons such as, alkanes and squalene. Terpenes such as, D-limonene, carvone and anise oil. Phospholipids such as, lecithine. Sulfoxides such as, dimethyl sulfoxide.

SC hydration level cannot be overstated. The diffusional resistance to xenobiotics is much lower in case of completely hydrated stratum corneum than in a dehydrated one. Skin discomfort is the most prevalent disadvantages. Skin irritation is caused by the same processes that cause increased drug transport, by breaking lipid bilayers of the stratum corneum [66]. One approach to addressing this challenge is to discover permeation enhancer mixes with synergistic effects [67].

Karande et al. 2004 effectively tested 5000 binary chemical mixes using a screening technique [68]. The majority of transdermal products exploit the occlusion effect, which may be categorized as enhancers functioning through increasing the fluidity of the stratum corneum.

Enhancers have traditionally been employed to augment small-molecule delivery, with relatively little effectiveness in increasing the penetration of macromolecules. Overall, while chemical treatments are successful, they cannot compete with physical augmentation procedures that produce a larger degree of skin permeabilization [68].

Physical methods

Hypodermic needles are the earliest and the most prevalent methods of physically bypassing the epidermal barrier. Throughout many circumstances, it is the only practical means of delivering substances that are poorly absorbable or unstable. This method of administration leads in the rapid distribution of huge volumes of medicine [69]. This method has many drawbacks being painful, and need to be administered with the help of professionals. Also it would be problematic to be used with patients suffering from phobia. So, several methods are being developed to be used instead of using needles (physical skin enhancement methods) like jet injections, laser, thermal ablation, dermabrasion, iontophoresis, MNs (MNs), ultrasound, electroporation, and combinations of the of the previous methods. These approaches are considered as convenient. Also affords a more controlled drug delivery pattern [69].

Prodrugs

The prodrug administration comprises various domains of concern, including skin permeability, chemical and enzymatic stability, and potential of skin irritation. Those factors must be addressed in order to build a good prodrug, the major rationale for using this strategy is to change the physicochemical characteristics main drug and thus entry of the main drug is greater than parent molecule. A chemical alteration of the component of interest provides an excellent chance to change its capacity to pass the stratum corneum when the diffusional barrier (lipid region) and the parent medication is moderately hydrophilic, increasing its lipophilicity can result in increased percutaneous flow. On the other hand, is paid for by increasing the size of the permeant. By producing more hydrophilic prodrugs, it was feasible to enhance the flow of very hydrophobic substances (which undergo viable tissue-controlled diffusion as opposed to stratum corneum-controlled diffusion) [70].

Skin irritation

The decrease in systemic adverse effects is a significant benefit of topical and transdermal medication administration. On the other hand, medication distribution via these channels introduces the possibility of other certain adverse reactions such as skin irritation at the site of action. Irritating contact dermatitis (ICD), an inflammatory response generated by repetitive or direct contact of the skin with mild irritants, and allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), a delayed, T-cell-mediated inflammatory reaction to a particular allergen, are two types of skin irritation responses. ICD reactions include erythema, scaling, and burns causing necrosis necrotic burns, whereas ACD reactions include erythema, edema, and, on rare occasions, vesiculation. Furthermore, the beginning of ACD responses is very diverse and depends on the irritant that triggered the response as well as the individual who exhibits the allergic response physiological pH changes is the major cause of skin irritation due to, hydration, delipidization, and disruption of lipid packing in stratum corneum. Also, bacteria proliferation, physiological and immunological reactions, as well drug (active pharmaceutical ingredient (API)) or vehicles or excipients used or the formulation used may influence skin irritation. As well, duration of TDDS application [71].

During the device design phase, the risk of generating skin irritation could be reduced by managing the device itself and formulation components. Additional methods for reducing adverse skin reactions was described by using a corticosteroid before applying the transdermal antibiotic, inclusion of corticosteroids in the formulation, and structural changes to chemical permeation enhancers, to name a few. Later, we'll go through the factors that have been discovered to cause skin irritation, and also the as well as techniques for preventing or treating these responses [72].

The role of drug features in skin irritation

The API was identified as the primary reason for ACD in individuals [79]. Therapeutic agents cause moderate-to-severe irritability in animal trials are frequently deemed out for usage in topical preparations. Predicting a drug's irritation potential without first studying it in an animal or cell model is challenging. It has been observed, for example, that the dissociation constant (pKa) of an API might change the dermal pH, causing cutaneous discomfort. Berner et al.1988 demonstrated that benzoic acid analogues that has a pKa values of 4 or less induced skin irritation in individuals after 24 h of exposure [73, 74]. Additionally, medicines with pKa values greater than 8 have been reported to cause dermal irritation. A number of studies found an increase in irritation with increasing pKa. According to this research, medicines with pKa values between 4 and 8 should cause the least amount of skin irritation. Furthermore, rather than omitting potentially irritating medications, by reducing their concentration in a topical or transdermal formulas may minimize the ensuing irritation to harmless and acceptable levels [75, 76].

The role of vehicle and devices in skin irritation

Skin's surface pH of the has been found between 5.4 to 5.9, which is critical for maintaining the defensive role of the skin against microbes and illnesses [77]. The skin is capable of producing buffers that prevent major pH shifts. However, external stimuli such as bathing and rubbing on solutions, medications, and cosmetics to the skin's surface can change its pH and hence aggravate or provoke dermal irritation. Alkaline solutions with a pH of 9 or higher, for example, have been known to induce skin irritation. Also, this investigation, aqueous solutions with pH levels of 5 and 7 did not irritate the skin [78].

Other investigation done by, Ananthapadmanabhan et al. 2003 discovered that applying a pH 10 solution to the skin, as opposed to a pH 4 or 6.5 solution, raised the transition temperature of stratum corneum lipids [79]. Enlargement and inflammation of the stratum corneum and the loss of the primary function of the skin as a barrier is known to give a rise in water loss through the epidermis. As a result, it is critical for the skin products to have a pH that is very near to the skins pH. In order to minimize skin irritation. Some universal medicinal solvents are skin irritants and so should not be utilized in topical treatments. Before in vivo testing is done, the solvents should be substituted with solvents that have tolerable irritation limits and good safety. To a certain extent, topical solvents approved safe for usage comprise of isopropyl alcohol, propylene glycol, isopropyl myristate, and polyethylene glycols (up to 60 percent are available commercially) [80].

A wide range of transdermal and local topical methods need extended skin occlusion in dosage forms of a cream, lotion or patches, etc., medicinal formulations. Non permeable skin occlusions for water have shown to raise the pH and warmth of the skin's surface while also retaining moisture and perspiration to produce a humid atmosphere. These circumstances encourage bacterial and yeast proliferation on the skin's surface. Sweat has been proven in studies to cause occlusion-induced irritation [81]. ICD responses are prevalent following skin occlusion, and their frequency has been observed to rise with occlusion time [71, 82].

Furthermore, occlusion may enhance the irritability of the topically applied API. Van der Valk and Maibach, for example, demonstrated that postexposure occlusion improved the irritation response to frequent temporary exposure sodium lauryl sulfate in ten healthy participants [83]. Occlusion has also been shown to cause functional impairment to the skin barrier, as measured by trans epidermal water loss [84].

Choosing the matrix-type patch vs a reservoir-type patch for the therapeutic agent administration might influence the likelihood of skin irritation. Each system's constituent have been observed to cause skin responses when used. Skin responses to the adhesive, hydroxypropyl cellulose, and ethanol in the original TDS have been recorded in the case of transdermal distribution of estradiol. Also, methacrylate reactions in the transdermal nicotine patch have been described [85]. Because most patch reactions are ACD reactions, predicting the irritation potential of particular patch components is challenging. Moreover, investigations comparing discomfort produced by matrix vs reservoir-type patches are inconsistent. Nevertheless, according to one source, matrix patches that are loaded with drug induce fewer cutaneous responses than reservoir release patches [86]. In contrast, comparable skin irritation was found after applying a fentanyl matrix or reservoir patch to the skin of healthy human individuals [87].

Formulation impact on skin irritation

The formulation used to distribute a medicine has been demonstrated to alter the appearance and severity of skin irritation. For example, hydrogels have been shown to minimize skin irritation by water absorption from the surface of skin [71]. Research that compared the safety and effectiveness of a lotion comprising benzoyl peroxide encapsulated in polymeric microspheres to a lotion containing free benzoyl peroxide found that controlled release of benzoyl peroxide from the microspheres decreased skin irritation in people while maintaining effectiveness. Depending on these findings, researchers hypothesized that controlled-release devices might be effective in minimizing discomfort caused by medicines used locally on the skin. medications [88]. Liposomes have also demonstrated to help with skin irritation. Liposomes' proposed methods for reducing skin irritation include increasing the moisture of the skin, hydration of the epidermis and prolonged drug release, and thus, prevent reaching dangerous drug concentrations in the skin [89]. When delivered to patients, tretinoin encapsulated in liposomes revealed less skin irritation than the equipotent gel formulation [90]. Employing a hydrogel or a cream containing a medicine encapsulated in liposomes or microspheres will reduce dermal irritation possibility of formulas used topically on the skin.

The addition of a soothing agent to the dermal products to topical formulations has been demonstrated to avoid or minimize skin irritation by reinforcing the skin's protective barrier. Zhai et al., 1998 for example, demonstrated that rubbing the skin with a cream having paraffin wax in cetyl alcohol before applying creams containing prior to treatment with sodium lauryl sulfate or ammonium hydroxide avoided irritation generated by these recognized irritants [91]. Furthermore, Wigger-Albeti et al. 1997 demonstrated that putting petrolatum to the skin prior to the irritating agent inhibited the irritating action of recognized irritants sodium hydroxide, toluene, and lactic acid on human skin. Petrolatum was shown to be less efficient in protecting against toluene-induced irritation [92].

Chemical permeation enhancers

The stratum corneum is an impenetrable wall external substances such as medicines. As a result, permeation-enhancing compounds are frequently used to help medications pass through the stratum corneum. Fatty acids, organic solvents (such as acetone and ethanol), alcohols, esters, and surfactants, and several others are permeation-enhancing substances. It is often assumed that higher efficacy of challenging to reduce the irritation induced these substances since the same processes that generate penetration also cause irritation. While powerful enhancers can temporarily compromise the rigidity of the stratum corneum barrier, their impact is not fully restricted to the stratum corneum, and interactions with living epidermal cells that can produce cytotoxicity and irritation. Investigations have been conducted with some success with the goal of minimizing the irritation capability of recognized permeation enhancers without diminishing their strength. Mixing permeation enhancers (synergistic combinations) and manipulating their chemical structures are two published ways for minimizing skin irritation caused by permeation enhancers. Ben-Shabat, Baruch, and Sintov created propylene glycol mono-and di-ester derivatives of saturated and unsaturated fatty acids to advance permeation without causing excessive irritation [93]. None of the studied derivatives improved penetration more than the corresponding fatty acid, while propylene glycol conjugates of oleic and linoleic acid reduced skin irritation while maintaining similar enhancing potential as compared to the free fatty acid. Sintov and Ben-Shabat have also reported on the creation of fatty acid–drug conjugates to improve penetration while maintaining safety [94]. Finally, Karande and Mitragotri analyzed several permeation enhancer combinations, their safety, and their synergistic enhancement in improving drug permeability [95]. One example offered was a cyclodextrin–enhancer combination that lowered the enhancer's adverse effects while retaining its permeability ability. In conclusion, it appears that a mix of permeability enhancers, solvents, and medicines may be capable of increasing potency without causing excessive irritation.

Anti-irritants and corticosteroids in reducing skin irritation

Steroids applied to the skin before irritant formulations have been shown to lessen skin responses. In humans, applying 0.1 percent triamcinoloneacetonide cream to the skin have demonstrated to reduce the occurrence and/or extreme skin responses related to with TDS exposure. This was found by comparing cumulative irritation scores obtained in individuals who received steroid pretreatment vs those who did not get pretreatment [96]. Finally, it has been demonstrated that including anti-irritants into irritating formulations reduces unfavorable skin responses [97]. Glycerol [98, 99], triamcinolone acetonide [99], lobetasol, and diphenhydramine are some anti-irritants that have been found to reduce adverse effects induced by irritants [100]. These solutions were demonstrated to minimize skin irritation caused by nonanoic acid, sodium lauryl sulfate, and captopril gel.

Transdermal drug delivery of antibiotics

Active transdermal drug delivery

Exterior stimulation, like electrical, physical stimulation, or mechanical, are known to improve skin permeability for molecules [101]. Active transdermal delivery is TDDS enhanced by using suitable equipment that is known to deliver molecules in a faster way. Additionally, this technique of improved TDDS has the potential to expedite the therapeutic effectiveness of administered medications (fig. 2) [102-104].

Microneedle (MN)

The MNs are considered to be a novel DDS, were drugs can be directly administered to blood circulation [105]. Needles in micro size are used to pierce the skin, reaching the epidermis, in order to deliver drugs. MNs are small and thin in order to be painless and to be able to transport medicines directly to the blood circulation region for active absorption, reducing pain [106]. Many attempts has been done by scientist in order to optimize MNs in order to obtain an effective insertion throw the skin [106].

MNs fabrication has been extensively studied, taking into account the purpose, drug type, dosage, and usage targets [107]. Till now, laser-mediated methods and photolithography have been used to create the metal MNs, typically achieve penetration depths of 700–1,500 µm. These MNs provide strong mechanical properties but can cause discomfort if penetration is too deep. A microneedle's 3D shape is created by cutting or ablating a flat metal/polymer exterior with a laser [108, 109].

Photolithography is a process of intricately constructing MNs that has the benefit of being able to produce needles of diverse forms and substances. This approach is mostly employed in creatinga dissolving/hydrogel MNs or silicon MNs by etching photoresist to create an inverse mold based on the microneedle structure. Since photolithography enables fine control over MN dimensions and forms, resulting in highly homogeneous arrays. Such precision can improve mechanical strength and ensure uniform skin penetration. However, the materials commonly employed, such as silicon, can be brittle, potentially restricting mechanical robustness. Drug loading capacity in photolithography-fabricated MNs is frequently limited by the material characteristics and fabrication technique. Silicon MNs produced through photolithography often penetrate the skin at depths ranging from 500–1,000 µm, making them effective for transdermal delivery while minimizing deep tissue discomfort [110].

Also, advanced 3D printing processes, including as two-photon polymerization and microstereolithography, have transformed MN manufacture, allowing for the creation of sophisticated and personalized shapes. According to studies, 3D-printed MNs have higher mechanical strength and better drug delivery effectiveness. For example, morphology-customized MNs improved not only mechanical strength but also drug loading capacity and release behavior, thanks to their highly customizable topologies. Furthermore, magnetic field-aided 3D printing (MF-3DP) has been used to create MNs with increased mechanical properties, surpassing limitations of existing production methods.3D-printed polymer MNs generally penetrate between 300–800 µm, with some custom designs reaching up to 1,200 µm, allowing for tunable drug release based on depth [111, 112]. Microstereolithography are widely investigated to produce MNs, the penetration depth of MNs varies based on fabrication method and material properties, typically ranging between 500 µm and 1,500 µm [113].

There are many types of MNs such as solid MNs which it role to pierce the skin to produce pores to make drug absorption much easier, coated MNs enhance the delivery of drugs which they are deposited at the surface of MNs, dissolving MNs which are constructed of medication formulations that dissolve once it gets in to contact with the interstitial fluid naturally administered melting needles that incorporate drug storage in hollow needles followed by delivery, and microneedle patches paired with various patch [114, 115].

The penetration depth of MNs is an important determinant in both efficacy and patient satisfaction. MNs penetrate the stratum corneum, reaching the epidermis or upper dermis at depths of 500 µm to 1,500 µm. Shorter MNs (≤500 µm) typically generate mild discomfort and do not stimulate deeper pain receptors. However, when MN duration increases, pain perception rises significantly. One study found that increasing MN length from 480 µm to 1,450 µm led to a sevenfold increase in pain ratings. As a result, while greater penetration can improve drug delivery to specific skin layers, it may also cause increased discomfort and systemic consequences. Balancing penetration depth is critical for improving treatment effects while reducing unpleasant feelings [116].

Fig. 2: Difference between various transdermal delivery systems in depth of dermal penetration [117]

Hydrogel-forming MNs

Hydrogel MNs arrays are fabricated using a process cold crosslinking of polymers in an aqueous [118].

These kinds of MNs are mainly made up of baseplate where micron-scale needles are organized. Drugs are mainly kept in a tank linked to the top of the base plate. The release mechanism is by releasing the drug from the reservoir to the blood circulation [119]. Several researches [119-122] demonstrated that hydrogel-forming MN arrays can efficiently distribute a range of compounds, including hydrophilic, hydrophobic, high molecular, and high dosage chemicals [119-122]. Hydrogel MNs have many advantages of being biodegradable and biocompatible, so no accumulation of ruminants in the skin. They are also not confined to the delivery of medications inside the needles [121].

In order to overcome the problems associated with oral therapies for tuberculosis (TB), such as liver damage, hydrogel-forming microneedles (MNs) were created. Four TB medications—isoniazid, pyrazinamide, ethambutol, and rifampicin-were manufactured in MN arrays using various tablet forms, including lyophilized, directly compressed, and poly (ethylene glycol) tablets. Polymers (S-97, PVA, and PVP) were used to make hydrogel films, which were then cross-linked at various temperatures. According to in vitro research, the characteristics of the medication affected its ability to permeate the hydrogel sheets. The two drugs with the highest penetration rates were ethambutol (46.99 mg) and rifampicin (3.64 mg). This method showed how hydrogel-forming MN arrays might be used to effectively distribute TB drugs transdermally [123].

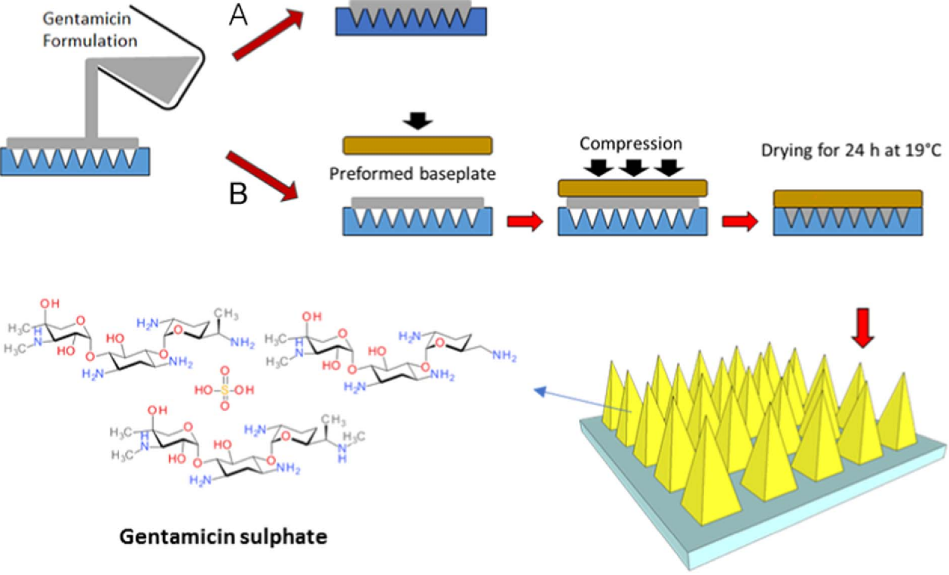

Infection is a major cause of death for infants and young children in less developed nations. The WHO suggests oral amoxicillin and injectable gentamicin as treatments; however, gentamicin must be administered by medical personnel, which can be difficult in rural regions. This was addressed by the development of a novel transdermal delivery system for gentamicin that uses polymeric microneedle (MN) arrays. The MN arrays were created using two polymers, PVP and sodium hyaluronate, along with 30% gentamicin. These arrays, which have 19 × 19 needles and a height of 500 μm, are robust and have a 378 μm skin penetration capacity, making them a simpler and safer option for outpatient therapy [124].

The synthesis of dissolving MNs starting First with the selection of the polymers starts, which are then blended with gentamicin and dissolved in deionized water. Mixing and sonification are done at 37 °C for 1–2 h. The resulting preparation was then dispensed in 100 mg into the MN mold at positive pressure (3–4 bar) for 15 min, until the mold was filled properly. Further, MNs array were dried at 19 °C for 24 h. As they are dry, they are evaluated through a Leica EZ4D digital light microscope [124].

A study of gentamicin-loaded dissolving Microneedle (MN) arrays gives a thorough assessment of their potential for transdermal medication administration. However, no direct comparison of in vitro release data between this unique technology and conventional administration procedures is provided, making it difficult to completely evaluate the MN system's therapeutic potential. In vitro permeation investigations revealed that dissolving MNs supplied 14.85% (4.45 mg) of the gentamicin load over a 6-hour period. Furthermore, approximately 75% of the gentamicin contained in the MN array was successfully administered within 24 h. This suggests a prolonged release profile, with the medicine delivered constantly from both the needle tips and the baseplate of the MN array. In vivo studies in animal models demonstrated that the Cmax of gentamicin reached with MN administration ranged from 2.21±1.46 μg/ml to 5.34±4.23 μg/ml, depending on the dose administered. The time required to achieve these peak concentrations (Tmax) ranged between 1 and 6 h, showing a dose-dependent absorption profile. Notably, the Area Under the Curve (AUC) values for MN delivery were larger than for Intramuscular (IM) injection, indicating that the MN approach provides more prolonged drug release. While the study sheds light on the pharmacokinetics of gentamicin administered by dissolving MNs, it does not provide a direct comparison of in vitro release patterns between the MN system and traditional administration methods, such as intramuscular injection. Comparative data would be useful in completely clarifying the therapeutic potential and efficiency of the MN delivery method relative to established procedures [124].

Fig. 3: A graph representing hydrogel films synthesis and crosslinking [123]

Fig. 4: The synthesis of MNs (A) one-step and (B) two-step [124]

In another study, a composite pharmaceutical system consisting of dry reservoirs of Cefazolin (CFZ) and hydrogel-forming microneedles (MNs) had been developed. Gantrez® S-97 and Carbopol® 974P NF crosslinked with PEG 10,000 were used to create the hydrogel system. According to swelling kinetic experiments, the hydrogel system that was created could achieve 4000% swelling in PBS with a pH of 7.4. Additionally, CFZ was able to achieve ≈100% cumulative penetration across the swollen hydrogel sheet, according to the results of a solute diffusion analysis. Optical coherence tomography demonstrated that the hydrogel system could penetrate the stratum corneum when formed into MNs, allowing the hydrogel-forming MNs to be inserted intradermally into the skin of an ex vivo neonatal pig. Furthermore, two distinct dry reservoirs filled with CFZ were created and characterized using Lyophilized (LYO) wafers and Directly Compressed Tablets (DCT). In less than a minute, these dry reservoir systems dissolved in phosphate buffer saline pH 7.4 demonstrating rapid dissolution. Full-thickness ex vivo neonatal pig skin was used in in vitro permeation experiments. According to HPLC analysis, the dry reservoir combination of DCT and hydrogel-forming MNs could transfer up to 80 µg of CFZ into the epidermis in just two hours after application. Furthermore, at 24 h, CFZ up to 1.8 mg may be delivered into and across the skin using a DCT reservoir in conjunction with hydrogel-forming MNs [125].

The current work focuses on employing Smart Film technology to improve solubility when delivering the hydrophobic antibiotic rifampicin. Unlike earlier methods, a one-step procedure can be used to create smart drug reservoirs (Smart Reservoirs) for hydrophobic substances. HF-MNs and three distinct rifampicin Smart Films (SFs) concentrations were generated in this investigation by fabricating SFs using a blend of polymers, specifically 15% w/w Poly Methyl Vinyl Ether-alt-Maleic Acid (PMVE/MA) and 5% w/w PEG with a molecular weight of 10,000 Da. This combination was chosen to achieve the desired mechanical strength and swelling properties necessary for effective skin penetration and drug delivery. In order to enhance the structural integrity of the HF-MNs, the polymer mixture underwent a crosslinking process. This involved thermal treatment at 80 °C for 24 h, facilitating the formation of a robust hydrogel network capable of efficient drug delivery. The physicochemical and mechanical characteristics, morphology, Raman surface mapping, interaction with the cellulose matrix, and maintenance of the loaded drug in the amorphous state of both HF-MNs and SFs were then thoroughly characterized. Their transdermal penetration effectiveness and medication loading were also investigated. The resultant SFs demonstrated that the majority of the medication was in the amorphous state and that the API was intact inside the cellulose matrix. The release kinetics of rifampicin from Smart Reservoirs were studied over a 24 h period. The study found that rifampicin had a consistent and regulated release profile, with 500±22 μg permeating the skin and 80±7 μg remaining inside the layers. This persistent discharge indicates that the system has the potential to provide long-term therapeutic benefits. The HF-MNs and SFs combination effectively delivers rifampicin transdermally. The formulation's success depends on the polymer ratios, crosslinking circumstances, and drug release kinetics [126].

Antibiotic delivery methods that avoid the human gut have been proposed as a potential solution to this issue. An alternate antibiotic delivery method, the antibiotic Hydrogel-Forming Microarray Patch (HF-MAP) system, has been created in this work. With>600% swelling in PBS over a 24 h period, the Poly(Vinyl Alcohol)/Poly(Vinyl Pyrrolidone) (PVA/PVP) microarray demonstrated exceptional swelling properties. It was demonstrated that the HF-MAP's points could pierce a skin model that was thicker than the stratum corneum. The drug reservoir for the antibiotic tetracycline hydrochloride was mechanically strong and dissolved entirely in an aqueous media in a matter of minutes. Using a Sprague Dawley rat model, in vivo animal studies demonstrated that administering antibiotics via HF-MAP produced a sustained release profile with a transdermal bioavailability of 19.1% and an oral bioavailability of 33.5% when compared to animals receiving oral gavage and Intravenous (IV) injection. At 24 h, the HF-MAP group's maximum drug plasma concentration was 7.40±4.74 μg/ml, while the oral (5.86±1.48 μg/ml) and intravenous (8.86±4.19 μg/ml) groups' drug plasma concentrations peaked shortly after drug administration and had dropped to below the limit of detection. The outcomes showed that HF-MAP can deliver antibiotics over an extended period of time [127].

Hollow MNs

Hollow MNs(HMNs) have the same fundamental construction as traditional hypodermic needles, namely the hollow core contains the drug inside, but they are much shorter their length is less than 1000m [128, 129]. Due to application of HMNs, the drug can be diffuse passively or actively, either by osmoses pressure generated from the needle lumen [129].

Mainly, the role of HMNs is to perforate the skin to enable the drug to be released from the needle core [130]. When using HMNs, the medication flow rate can be purposefully regulated using standard apparatuses that control flow as syringes and micropumps [124]. solutions are employed, a fluid medication formula may be given directly into the skin without the need to dry the pharmaceuticals, preventing thermolabile chemicals from being damaged [124]. One advantage of employing HMs is that the time and quantity of medicine administered may be controlled, allowing for a wide range of drug concentration-time profiles [131]. Furthermore, the pressure in an HM may be altered, resulting in a change in flow rate [128]. This characteristic enables the administration of either a quick bolus injection or a gradual infusion [128].

A hollow MN array was manufactured through a Three-Dimensional (3D) printing technique. The design of the MN composed of an emptytank. The hollow MN array were also fabricated through conventional methods, such as Stereolithography (SLA) technology using class-I resin feature. Software was used to improve the location, direction, support, and position of the job to print. Printing consisted of fourfactors: The volume of the resin needed to print the hollow MNs, the resolution of each sheet, and the dimensions of supports touching edges, the positioning of the item to be printed in regards to the platform, and the temperature of the resin tank, which was 29.8 °C.

The resin, which is unpolymerized and is attached to the hollow MNs is rinsed softly with 99.9% IPA, to avoid damage to the printed object. The hollow MN was exposed to UV curing for 60 min. at 60 °C. to increase durability of the printed MN [132].

The HMNs array were found to be suitable for the delivery of high molecular weight antibiotics as in the case of rifampicin which has a molecular weight of 822.94 g/mol, and transdermal delivery is important for such drug, since its oral delivery presents problems as sensitivity to stomach acids, low bioavailability and the risk of toxicity to the liver. The synthesized hollow MNs were optimized by the addition of holes to the sub-apical parts at the side of the MN tip. These holes increased the durability and integrity. The quality of hollow MNs were assessed through optical and electronic microscopy. Moreover, the consistency of the array system and the ability to penetrate the skin are evaluated. Rifampicin delivery through hollow MN array systems was examined using ex vivo permeation studies and pig skin to evaluate bioavailability. The results showed that rifmbicin had good bioavailability when delivered using hollow MNs array [132].

Degradable MNs

Biodegradable polymers are used to produce this kind of MNs, such as polylactic acid, polyglycolic acid, Poly(Lactide-Co-Glycolide) (PLGA), and chitosan. The medication are mainly enclosed in side these polymers (acts like a matrix), then the release will start when the MNs interacts with the interstitial fluid. Because MNs are biodegradable, there will be no MN residues [133, 134].

Due to having benefits like accurate loading, complete dermal elimination, and attachment of the drug tank, biodegradable MNs have gained prominence over other MNs. Natural biopolymers have been utilized as a material in medicinal applications for millennia and have grown in relevance in medication delivery. The section that follows discusses the different polysaccharide and polypeptide-based biomaterials utilized to make biodegradable MNs. Furthermore, the biocompatibility and biodegradability of these biomaterials, as well as their use in transdermal medication administration [135].

Antifungal agents used orally or topically face many problems like low bioavailability, emergence of resistance and low sustainability. Transdermal delivery through polymeric MNs can provide a solution to these complications. One of the polymers used for the synthesis of MNs is Chitosan-Polyethylenimine (CP-Polymer), which is a ecofriendly and a biocompatible substance, and further, it has an antimicrobial activity, that is insusceptible to drug resistance and provides continuous drug release [136].

Production and characterization of CP-copolymer: The production method of CP-copolymer was done in reference to a technique that was formerly described in literature. After passing through the night, mixing until it dissolves and adjusting the pH to 7.0 by adding 1 M of NaOH. Afterwards, CDI was mixed well with the previously prepared solutions in a ratio of 1:2 (CDI: amines in chitosan), mixing is done for an hour. Consequently PEI was added using a dropper and under constant mixing and with a ratio of 2:1 (PEI: amines in chitosan) by molarity. The solution is allowed to stand overnight to complete the polymerization reaction. Then dialysis takes place on the produced solution against water for an extra 48 h to eliminate excess free PEI. Lastly, CP powder that was achieved by lyophilization and was characterized by 1H NMR spectroscopy. Afterwards, the zeta potential was calculated using a Malvern Nano-ZS Zeta Sizer machine. The pH was identified through a pH meter [136].

Synthesis of drug-loaded MN patches: MN patches were produced through a micromolding procedure. Poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS) mold was initially made by adding the mixture of PDMS and curing agent (weight ratio of 10:1) into a stainless-steel master assembly, that has 10×10 arrays of sharp-pointed pyramidal MNs with a base width of 300 μm, height of 1000 μm, and a space between them of 700 μm. Then, the gas was removed from the PDMS mold and dehydrated using an oven at a temperature of 70 °C for 1 h. Afterwards, dissolving CP powders was done in an aqueous solution with acetic acid (1%, v/v). To control pH at 6, dialysis then was performed on the CP solution (20 mg/ml) (MWCO: 10 kDa) against DI water to eliminate excess acetic acid. The next step was dehydrating CP solution in an oven at 37 °C tilla of the concentration of the CP solution is up to a maximum of 5 wt% and the solution becomes sticky. At this point the CP solution was ready for CP-MN patch synthesis. Drug loading starts with fluconazole (F) or amphotericin B (AB) which were dissolved in DMSO (40 mg/ml). An aliquot of 125 μl of the drug solution was taken and mixed well with 875 μL CP solution along the night. Afterwards, concentrated CP and CP+AB solution were added into PDMS mold and centrifuged at 4000 rpm, 10 min, and was let to stand all night. In the final steps of the MN patches synthesis, the HA solution was added into the moulds using centrifugation to allow support of the substrate of the MN patch, and the MN patch was left to dry overnight, and it was removed with caution from the molds. The CP/AB hydrogel after soaking into CP/AB MNs in buffer solution, was nearly 7 [136].

The mechanical durability of was checked through an Instron 5543 Tensile Meter. A constant force was added to the outermost of MNs, which were positioned uphill on a flat stainless-steel probe, till a dislocation of 400 μm was attained at a continuous speed of 0.5 mm/min.

The efficacy of the treatment using MN batches in vivo was tested through mice models with fungal infection and Mpatches loaded with Amphotericin B, which is an anti-fungal agent. The results of the in vivo study have proved that this approach has high potential in the treatment of fungal infections, especially that the MN patches were able to attain good bioavailability. The results were also attributed to the use of an anti-fungal polymer, which added to the effect of amphotericin B [136].

The DH/VEGF@Gelma-MNs are prepared in this work using high-quality biocompatible gelatin methacrylate (Gelma) and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), loading with Doxycycline Hydrochloride (DH) and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factors (VEGF). Gelma-MNs have conical features that are in alignment, good mechanical and swelling qualities, and the ability to enter the skin. DH/VEGF@Gelma-MNs exhibit biocompatibility and antibacterial activity to prevent Escherichia coli (E. coli) and Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) from growing. Additionally, DH/VEGF@Gelma-MNs strongly encourage human umbilical vein endothelial cells' (HUVECs') migration and tube formation. Compared to DH/VEGF@Gelma-plain patch (DH/VEGF@Gelma-PPs) flat patches and DH/VEGF solution injection, DH/VEGF@Gelma-PNs treatment speeds up diabetic wound closure in vivo. According to histological analysis, DH/VEGF@Gelma-MNs covering exhibits angiogenesis, increased collagen deposition and remodeling, follicle and sebaceous gland development, and intact wound re-epithelialization. In conclusion, DH/VEGF@Gelma-MNs present an interesting approach based on a synergistic MN therapeutic platform by releasing DH and VEGF to improve diabetic wound healing, which has antibacterial and angiogenic effects [137].

Another study aimed to create dissolving microneedle patches (CP) based on sorbitol and hyaluronic acid, microfiber-coated microneedle patches (MP), microfibers loaded with polyvinyl pyrollidone, and microfibers based on Eudragit S-100. Scanning electron microscopy and differential scanning calorimetry, X-ray diffraction, were used to analyze the formulations' morphology and phase, respectively. Antimicrobial assays, in vitro drug release, substrate liquefaction tests, and in vivo antibiofilm investigations were carried out. The surface of MF was uniform, and the network was interconnected. Microstructures with homogeneous surfaces and sharp tips were found by morphological study of CP. Clarithromycin was added as an amorphous solid to MF and CP. The liquefaction test revealed that hyaluronic acid was responsive to the hyaluronate lyase enzyme. The alkaline pH (7.4) responsive drug release from fiber-based formulations (MF, MB, and MP) was approximately 79%, 78%, and 81%, respectively, within 2 h. Around 82% of the medication was released by CP in just two hours. MP's inhibitory zone against Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) was approximately 13% greater than those of MB and CP. In comparison to MB and CP, MP was found to be effective for managing microbial biofilms because it was able to eradicate S. aureus from infected wounds reasonably quickly and cause skin regeneration after application [138].

Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) have been used to prepare antibacterial agents and have been shown to have low toxicity and antibacterial qualities. ZnO NPs have a few drawbacks, though, including poor dispersion in various mediums, which lessens their antibacterial activity. With organic cations and organic/inorganic anions, ionic liquids (ILs) are a type of low melting point salts that have good biocompatibility and the ability to both improve ZnO NP dispersion and have antibacterial qualities. A new transdermal drug delivery technology called microneedles (MNs) can efficiently create a transport channel in the epidermis and deliver the medication to a specific depth without causing discomfort, harm to the skin, or excessive stimulation. Dissolving Microneedles (DMNs) have advanced quickly due to a number of benefits. When compared to solitary ZnO NPs and a single IL, this study confirms that ZnO NPs dispersed in imidazolidinyl IL had superior and enhanced antibacterial activities. Consequently, the ZnO NPs/IL dispersion exhibited strong antibacterial properties. Then, to create DMNs, ZnO NPs/IL dispersions with complementary antibacterial qualities were employed as antibacterial agents. According to in vitro antibacterial studies, DMNs likewise possessed strong antibacterial qualities. Moreover, DMNs were used to treat infections in wounds. In order to cause microbial death and hasten wound healing, antibacterial DMNs were introduced into the infected site, dissolved, and then released [139].

Solid MNs

The "poke-and-patch" method is used for solid MNs. Solid MNs are mainly built of various metals such as silicon, titanium, stainless steel, and titanium. These MNs are used to produce micropores, after that the drug applied, so the drug entrance resistance is minimal [106, 140-142]. In one investigation, super-short solid silicon MNs (70–80 µm) outperformed sharp-tipped MNs in terms of skin permeability. In addition, they can be kept attached to the skin for a longer durations of time than sharp MNs [143]. Narayanan and colleagues created solid silicon MNs and gold-coated them to boost mechanical strength and biocompatibility. Solid MNs are considered as a promising approach for enhancing drug bioavailability in TDDS [144].

Human papillomavirus causes a skin infection called warts. The current therapy is based on mechanical obliteration of the wart, like cryotherapy and electrocautery. These therapies cause severe pain and mostly, the treatment either fails or the warts reoccur. This research compared between cryotherapy and modern bleomycin MB patch as therapy for warts, using 42 patients who suffer from warts. The efficacy of the two treatments was measured by the guidelines of the Physicians Global Assessment (PGA) and the Patients Global Assessment (PaGA). The results of the study showed no significance difference between cryotherapy and Bleomycin MN patch in the effectiveness in eliminating the wart, however the Bleomycin MN patch was extremely less painful when compared with cryotherapy. Furthermore, the MN patch treatment increased compliance in patients who were deterred by the pain of the cryotherapy [129].

The medical research community is searching for substitute antibiotics due to the global trend of growing antibiotic resistance to Gram-negative bacteria.

When used against gram-negative bacteria, antibiotics like polymyxin B (PMB) have high effectiveness and low resistance rates. However, the therapeutic constraints of topical PMB treatment, such as its short residence period, make its application in treating skin infections challenging. In order to administer PMB to the skin, we provide Porous Silicon Microneedle (pSi MN) patches. The fabrication of pSi MN patches involves first producing the projections using dry Si etching techniques, then electrochemically etching to produce porous layers surrounding the MNs. Gram-negative Escherichia coli's inhibition zone is measured to assess the antibacterial activity of pSi MNs. Next, chemical mapping employing matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization confirms that PMB is effectively transported into the epidermal layer of ex vivo skin models. Imaging using mass spectrometry (MALDI-MSI). The findings show that pSi MN patches are a useful and effective method for transdermal PMB delivery that preserves bioactivity and antibacterial efficiency, hence increasing the potential of existing transdermal drug delivery methods [145].

Photomechanical waves

Photodynamic waves enter subcutaneously (SC), permitting the medicine to flow via the temporarily created channel [146, 147]. The wave causes limited ablation, which is done through exposing the incident wave to a low radiation dose of around 5–7 J/cm2 in order to expand the depth to 50–400 m for effective transmission. This restricted ablation had a longer rise and duration than previous direct ablation procedures, necessitating the regulation of photodynamic wave characteristics to assure product delivery to the appropriate depth in the skin. Within minutes, the wave produced via laser pulse enhanced skin permeation, permitting the diffusion of macromolecules throw the skin [147].

For the treatment of acne, multiple antibiotics and photosensitizers are used. Treatment with antibiotic has its drawbacks like adverse reactions, drug resistance, and low efficacy due to small skin diffusion. A study was performed on a novel therapy in which erythromycin and branched polyethyleneimin-hematoporphyrin (bPEI-HPP) conjugates were filled into liposomes (cationic photosensitizer-erythromycin loaded liposomes) [148].

The formulation of bPEI-HPP conjugates starts with adding 1 g of HPP, bPEI and 100 mg of HPP, after dissolving each discretely with 20 ml DMSO for four hours. Then DCC and NHS were added as catalysts and a coupling reagent to HPP solution with molar ratio of bPEI to catalyst = 1:1.5. After 4 h the HPP is added by a dropper to the bPEI solution and was left all night under constant stirring. Through a dialysis membrane the bPEI-HPP conjugate (MWCO: 1000) was dialyzed against distilled water for 2 d. Removal of the solution of the membrane comes next, followed by filtration. Afterwards, lyophilization is performed. The geometry of the bPEI-HPP conjugate was measured by1 H NMR, spectrometer and Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrometry (FT-IR) [148].

CP-Ls prepared in the interior side of a round-bottom flask, a lipid film was formed through evaporating 10 ml of chloroform solution that contains a decent quantity of DPPC (7.5 mg), cholesterol (2.5 mg), erythromycin (1 mg) and bPEI-HPP (10 mg; CP-L 1 and 20 mg; CP-L 2) to attain a specific molar ratio in the liposome blend. Ammonium sulphate solution (10 ml, 1 mmol) is added to lipid film. Then, heating and sonification are applied to the solution [148].

Penetration studies are performed using Franz cell diffusion system and fluorescence microscopy. The effectiveness in the penetration of the CP-L was found to be higher than that of the bPEI-HPP, the penetration efficiency of CP-Ls was greater than that of bPEI-HPP, unloaded cationic photosensitizer and free HPP since CP-Ls, since CP-Ls contained of a phospholipid that share great similarities between the cell membrane lipid composition. To evaluate the efficacy of antibacterial in vitro, the bacteria, Propionibacterium acnes (P. acnes) was used.

CP-l 2 had caused losing viability rate of the bacteria by 95% from the Colony Forming Unit (CFU) assay, and was 2.4-times greater than erythromycin-loaded liposomes (39%) and 1.9-fold higher than bPEI-HPP-loaded liposomes (50%). As a result, it was recommended that polycationic photosensitizer and antibiotic-loaded liposomes together can be a novel therapy for the treatment of acne [148].

Passive transdermal drug delivery

With the purpose of improving the effectiveness of TDDS drug molecules must attain the following criteria, having a low MW (less than 1 kDa), low skin irritation probability, have both hydrophilic and lipophilic affinity, and short half-life [149]. Skin permeation might be influenced by several factors like, the species used, site and age of skin, moisture content, temperature, exposure duration, application area, methods used for pretreatment, and penetrant physical characteristics [149].

Multiple trials have been performed to enhance the efficiency of TDDs by either using chemical enhancers to improve the spread ability of the medicine through the dermal layers, or by increasing the solubility of the drug molecules, so this can be achieved by using microemulsions, super-strong formulations, and vesicles [57, 150]. Penetration enhancers can be either used with other penetration enhancer or alone used to obtain superior permeability throw the skin. Eutectic combinations and nanoparticle composite self-assembled vesicles are examples of synergistic systems.

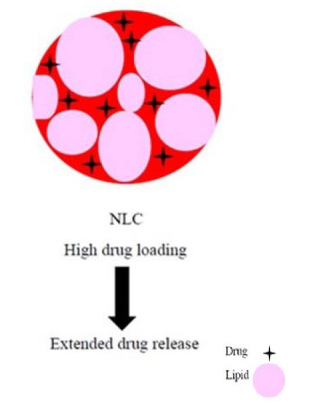

Vesicles

Vesicles are water-filled colloidal carriers made up of amphiphilic bilayer structure. To accomplish transdermal absorption, vesicles can transport both hydrophilic and lipophilic and molecules. Vesicles can be employed to produce extended release of drug molecule in case of TDDS. Thus, vesicles can also be used to modulate the absorption rate via its multilayered structure. Vesicles can be classified in to liposomes, ethosomes, Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLN), and nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs) based on the features of the component molecules [151].

Liposome

Liposomes are soft spherical vesicles bilayer structure (can either single or multiple layer). Their primary constituents are generally phospholipids, and cholesterol. Phospholipid mostly made up two parts of polar head and two hydrophobic hydrocarbon chains. The polar head has groups that have a positive or a negative charge. The lengths and extent of unsaturation of hydrocarbon chain molecules vary. Liposomes arise spontaneously when a dried lipid film is reconstituted in an aqueous solution. Liposomes may be both hydrophilic and hydrophobic due to their unique configuration that permits encapsulation of both hydrophilic and hydrophobic compounds. Nevertheless, other researchers have discovered that liposomes can only stay on the skin's surface and cannot penetrate through the epidermis, this will lead to reducing the quantity of medicine taken into the bloodstream. This characteristic improves medication retention on the skin, extending their action at the injury site, and allowing for long-term sustained release. Liposomes are thus the ideal approach for the local therapy of skin disorders [152].

Transfersomes are highly flexible liposomes (deformable liposomes, or elastic). Elasticity is the most important criteria, which is due to the presence of surfactants having only one chain. The surfactants increase the fluidity of the phospholipid bilayer vesicles become extremely malleable, transforming them into first-generation transfersomes. Second-generation transfersomes have evolved throughout time, with a minimum of a single primary bilayer building block (usually fluid-phase phosphatidylcholine lipids) and at least two or more polar lipophilic molecules. Third-generation transfersomes are composed of amphiphilic surfactants that can posses phospholipids. The capability of deformation has aided in the construction of transfersomes that are able of piercing skin pores 5 to 10 times smaller than their size, allowing for the administration of skin-piercing medicines with MWs of up to 1000 kDa. Furthermore, TDDS utilizing transfersomes enables the delivery of macromolecular medicines like as peptides or proteins [153].

A research aimed to apply and formulate Ethosomal Gels (EGs) to be used in TDDs thatgained significantattention, since they have good solubility in water and known for being biocompatible. Another goal of this research is to characterize ethosomes of antileprotic medicine, which is Dapsone (DAP) along with an antibiotic Cloxacillin Sodium (CLXS). This approach increases the drug delivery at the site of action, more than that of the conventional method through gel formula of DAPS, and reduces the related issues of oral administration [154].

Ethosomes were formulated using cold method. Ethosomes were formulated through modified cold technique. The preparation starts with dissolving Phospholipid (3-5% w/v) and cholesterol (0.5-1% v/v) in ethanol (30-40% v/v) at room temperature and with forceful stirring. Through the process of stirring propylene glycol (5-10% v/v) at a water bath with temperature of the drug is dissolved in distilled water to form a solution of (1% w/v solution), that is heated up to 30±1 °C. Gradual addition of the solution on ethanolic lipid solution with constant stirring on a rate of 900 rpm. The resultant mixture was in the form of a dispersion of vesicles that were permitted to cool at room temperature for 45 min [154].

Characterization was done through four aspects; particle size, entrapment Efficiency (EE), zeta potential and permeation studies. Particle size (Vesicular size) was examined by the SEM and the results ranged between 127±9.01 to 215±7.23 nm, which is reliant on soya lecithin and ethanol concentrations.

The mean (as an entrapment) efficiency of preparations was in-between 52.31% and 73.51% and 49.07% to 71.91% for DAP and CLXS respectively. The vesicular charge was affected by the profound ethanol concentration in ethosomes which moved the vesicular charge from positive to negative. It was detected that F1 and F2 preparations have zeta potential of-25.08±1.03 mV and-50.11±1.97 mV respectively and do not accumulate quickly. The drug release of ethosomes ranged from 84.68% to 96.58% and 64.89% to 84.21% for DAP and CLXS respectively. Ethosomal gel was formulated using optimum ethosomes, in which the physical and chemical properties and the release characteristics were investigated. The results of the study showed that G5 ethosomes allowed the antileprotic agent to have higher efficacy and stability, with decreased adverse reactions and lower toxicity linked with the antileprotic agent [154].

Investigating flexible nanoliposomes for topical daptomycin administration and recording penetration rates and bacteriostatic efficacy against skin infections were the goals of this investigation. The daptomycin-laden flexible nanoliposomes (DAP-FL) were optimized using response surface methods, and the investigation index was the quantity of drug loaded into the particles. Lecithin to sodium cholate (17:1 (w/w)) and lipid to medication (14:1 (w/w)) were the ideal lipid ratios. The ultrasonic therapy lasted 20 min, and the hydration temperature was fixed at 37 °C. The resulting DAP-FL exhibited a narrow size distribution (polydispersity index of 0.15), and a modest mean particle size (55.4 nm). The average drug loading percentage was 5.61%±0.14%, and the average entrapment efficiency was 87.85%±2.15%. The percentage and amount of cumulative daptomycin penetration from DAP-FL within 12 h were determined using skin mounted between the donor and receptor compartments of a modified Franz diffusion cell. These results directly demonstrated quick and effective antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus, at 96.28%±0.70% and (132.23±17.73) μg/cm2 *5 = 661.15±88.65 μg/cm2. Daptomycin was found in the mouse's multilayer skin tissues and underlying structures in the dorsal skin after local application of DAP-FL. Significant inhibition of bacterial growth and injury-induced biofilms was observed at effective therapeutic concentrations that were sustained for several hours. These findings show that daptomycin can more effectively penetrate the skin, where it has a potent antibacterial effect and activity against biofilms, when the DAP-FL is present. There may be a new way to use daptomycin in clinical settings with this innovative formulation [155].

Another work investigates the in vivo action of Chrysomycin A (CA) and develops a transdermal liposomal formulation of CA for the concurrent treatment of cutaneous Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA) infection and cutaneous melanoma. With an IC50 value of less than 0.1 μm in B16-F10 cells, the produced liposomes (TD-LP-CA) have a potent anticancer effect. They also inhibit MRSA proliferation with a Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) of 1 μm and eliminate established MRSA biofilms at 10× MIC in vitro. More significantly, TD-LP-CA exhibits superior subcutaneous tumor penetration following skin application in vivo and improved Stratum Corneum (SC) penetration, reaching more than 500 μm beneath the skin's surface as a result of alteration with the TD peptide. After topical dermal application, TD-LP-CA exhibits a moderate inhibitory impact on subcutaneous melanoma with a 75% tumor suppression rate, as well as a good therapeutic effect against intradermal MRSA infection in mice. Because they can penetrate the skin barrier, the liposomes made here may be a potential vehicle for transcutaneous CA transfer in the treatment of superficial conditions such infections and skin cancers [156].

Ethosomes