Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 4, 2025, 30-37Review Article

METAL–ORGANIC FRAMEWORKS OVERVIEW: STATE OF THE ART

REEM MOHSIN KHALAF AL-UOBODY1, HAYDER A. HAMMOODI1, AMIRA AMIN2*

1Department of Pharmacy, Mazaya University College, Thi-Qar, Iraq. 2College of Pharmacy, Al-Ayen Iraqi University, Thi-Qar, Iraq

*Corresponding author: Amira Amin; *Email: amira.kassem@pharm.dmu.edu.eg

Received: 10 Mar 2025, Revised and Accepted: 19 May 2025

ABSTRACT

Metal-organic Frameworks (MOFs) are believed to be a cluster of complexes, metal ions or groups, synchronized with organic ligands. In addition to durable bonds between inorganic and organic groups, reticular synthesis creates MOFs, perfect election of ingredients of which can generate high thermal and chemical stability. Over the few years, the usage of MOFs in biomedical treatments has significantly increased because of their high loading capacities, high surface areas, and precision tunability. A broad range of drug delivery treatments are being investigated for MOFs. MOFs exhibit high drug loading capacities due to their large area and tunable pore sizes. MOFs were first employed to deliver small-molecule medications, then switched to deliver macromolecules, current developments in this area are needed to support this claim. Here, we examine how MOFs have been used historically for drug delivery, paying particular attention to the various ways that MOFs might be designed for certain drug delivery uses. These choices include drug loading, synthesis technique, and MOF structure. Cellular targeting, biocompatibility, tuning, alterations, and uptake are additional factors to consider. This review's overall goal is to direct MOF design toward innovative biological uses.

Keywords: Metal organic framework, Drug delivery, Zinc, Zeolite, Zirconium

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i4.54159 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Around the past 15 y, the study of Metal Organic Frameworks (MOFs) that acknowledged as porous polymers, has experienced enormous growth. Yaghi and colleagues have made significant contributions to this discipline. They came up with the word "MOF" in 1999 and used the "yellow-sphere" in their work to theoretically represent the level of free pore in their organization [1]. The "yellow-sphere" concept is critical because it symbolizes the coordination environment around metal centers, which are key to the stability and structure of the MOF. The metal centers (often transition metals like zinc or copper) are connected by organic linkers to form a highly ordered, three-dimensional network. The geometry of these "yellow spheres" influences the size and shape of the pores within the MOF. This coordination not only defines the pore size but also plays a vital role in stabilizing the framework. The precise arrangement of these metal-organic connections contributes to the structural integrity and thermal stability of MOFs, even under harsh conditions (e. g., high temperatures or aggressive solvents), which distinguishes them from more traditional porous materials like activated carbon or zeolites. By referencing the “yellow-sphere,” Yaghi highlighted the organized, regular nature of MOF frameworks, which contrasts with the more irregular structures seen in materials like activated carbon [1].

A unique chemical adaptability, a designable framework, and an unprecedentedly wide and everlasting interior porosity are all features of this intriguing family of crystalline hybrid materials, which are created by the connection of metal centers with an organic linker or linkers. Because of this, MOFs are a unique porous material that surpasses the limitations of previously recognized porous materials including activated carbon, mesoporous silica, and zeolites [2].

The two primary parts of MOFs are the metal inorganic clusters and the organic linkers. In the resulting MOF architecture, the linkers serve as "struts" that bind the metal ions, which in turn serve as "joints." Because of this, the synthesis of MOFs frequently relies on methods of trial and error. But there is a great need for "designable MOFs." The idea of isoreticular synthesis, which was first presented by O'Keeffe and Yaghi5 in 2002, is based on the connotation of inflexible secondary building units (SBU) that have been designed into determined ordered structures that are held together by strong bonds. They demonstrated this by employing comparable but different organic linkers to replicate the octahedral inorganic SBU of MOF-5 [3].

The tremendous tunability of the materials, structure, pore size, and functions is unquestionably the primary advantage of MOFs. Yaghi's introduction of isoreticular chemistry opens nearly limitless possibilities. In certain situations, the simplicity of synthesis is also advantageous. The utilization of certain undesirable metal ions, such (Chromium) Cr3+, is one of the biggest drawbacks. Even though Cr3+is not poisonous, businesses are unlikely to want to utilize it extensively because of the stringent laws governing the storage and disposal of Cr, particularly Cr6+. Ironically, a Cr-MOF is the best stable MOF (MIL-101(Cr)) [4].

Search strategy

Information were gathered from Scopus, Pubmed, Web of Science, and Google scholar, from 2001 to 2025. The keywords employed were Metal organic framework, drug delivery, zinc, zeolite, zirconium.

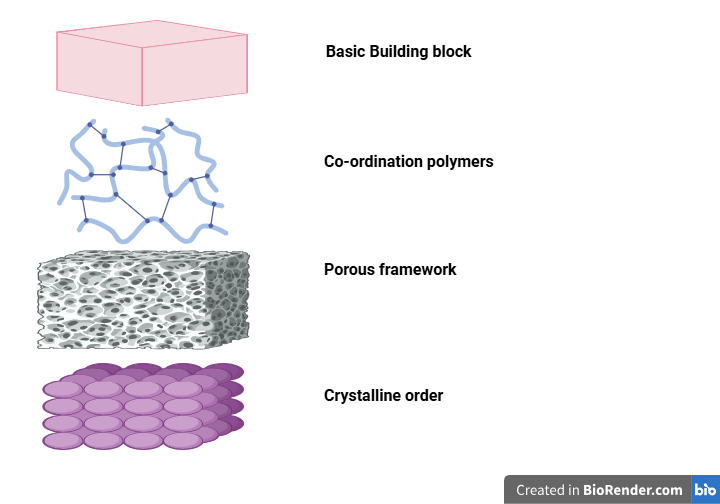

Structures and compositions of MOFs

MOF structures can be explained on four levels. A metal ion is the chemical components that make up the MOF at the first level. Although monovalent metal ions have also been utilized, multivalent metal is the most frequently utilized [5].

The most widespread ions utilized in MOFs for treatments are zirconium (IV), iron (III), and zinc (II). Multiple carboxyl groups are typically included in the ligands employed in MOF production. A crystal lattice is produced when the ligand and ion coordinate. Some MOFs are known to demonstrate some flexibility, even though the majority have rigid structures [6]. The SBU, the second level of structure, is where many ligands coordinate with a metal ion to form moderately stiff. In essence, SBUs acts as a unit or template that allows the MOF to expand. The internal framework is defined by the connection of numerous SBUs that connect two metals. The MOF’s void volume is integrated on this third level. With a metal ion and ligand, the pore structure might usually be ascertained beforehand. However, the coordinating metal and ligand largely dictate the first three layers of MOFs [7]. The growth of the internal framework determines the fourth structural of MOF, the outside morphology. The external morphology of the MOF will be influenced by the combination processes employed and whether compounds (such as medicines) are being encapsulated during synthesis [8]. Moreover, coordinatively unsaturated metal sites (CUSs) found in MOFs can behave as Lewis’s acids, help load molecules on the MOF. MOFs are especially appropriate for usage in drug delivery applications because of exquisite, multilayer control their structural and chemical characteristics.

Further, the explanation of SBU in MOFs is key to understanding their structure and function. Here’s how SBUs contribute to stability, porosity, and drug loading capacity. The SBU in a MOF refers to the metal clusters or nodes that act as the central building blocks around which organic linkers connect to form a framework. The type of metal used in the SBU (zinc, copper, aluminum) plays a role in determining the thermal, chemical, and mechanical stability of the MOF. This metal-organic coordination imparts strength to the framework, making MOFs more resistant to external stressors like high temperatures and solvents, contributing to their superior structural stability compared to other porous materials like zeolites or activated carbon [7]. The SBU influences the porosity of the MOF by determining the size, shape, and connectivity of the pores within the framework. The arrangement of the SBUs, combined with the size and flexibility of the organic linkers, dictates the overall pore structure. Thus, the type of SBUs and their spatial arrangement directly determine the pore size and porosity of the MOF, which is crucial for applications like gas storage and drug delivery [7]. Further, the SBUs affects drug loading by controlling the pore size and the nature of interactions within the framework [7].

Fig. 1: A graphic schematic of the MOF structural hierarchy

Advantages of drug delivery

MOFs have proven easy surface functionalization, high loading measurements, synergistic drug loading, protection of therapeutics, controlled release of drugs in biological surroundings, and exact control over their size, and pore dimensions. The pore diameters of the MOF can be changed to enhance loading or regulate release, or synthetic techniques can be modified to produce nanosized MOFs [9]. Furthermore, synthetic or post-synthetic alterations can be applied to enhance MOF loading and stability in biological settings [10]. MOFs can load medicine since they have some of the most porous architectures and greatest surface areas of any delivery vehicle that have been documented. This leads to high local drug concentrations when the drug is given from MOFs [11]. Controlled release from MOFs has also been determined [12] Stimuli (pH, Adenosine triphosphate, Ultraviolet-visible light, etc.) naturally cause release from certain frameworks, while moieties that regulate the release of medicines from the pores can readily be added to other frameworks [13]. The formulations triggered by these stimuli have been examined. Additionally, MOF pores can be engineered to either slow or speed up the therapeutic cargo's diffusion. By selecting different chemical ingredients, it is also possible to control the rate of MOF disintegration in biological contexts and, consequently, the rate of drug release [14]. Synergistic therapeutic impacts can be obtained by loading several therapies in a single MOF or by releasing the metal or ligand from the MOF together with the therapeutic, depending on the loading technique and MOF configuration. This synergy has been suggested for osteopathic applications, cancer, vaccinations, tendon and wound healing, and more [15]. Numerous macromolecular and small-molecule treatments can be encapsulated in MOFs. Their ability to encapsulate poorly-water-soluble cancer treatments and gas transmitter molecules (nitric oxide and hydrogen sulfide) is very helpful [16]. Additionally, it has been demonstrated that MOFs may maintain the structures of macromolecular cargos, enclose them, and shield them from deterioration in biological settings. Even bigger cargos have been investigated, such as cells and vaccinations [17].

The cytokine response to MOF-based vaccine delivery is a key indicator of the activation and modulation of the immune system upon antigen exposure. MOFs have shown potential not only in delivering antigens but also in influencing the immune microenvironment through adjuvant-like properties. MOFs may trigger the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, indicating an innate immune response, particularly if the MOFs act as adjuvants. Th1 cytokines like IFN-γ could be upregulated, promoting cell-mediated immunity, which is essential for protection against intracellular pathogens. On the other hand, Th2 cytokines like IL-4 or IL-5 could be activated if the response skews toward humoral immunity, essential for producing antibodies [18].

Further, MOF used enhanced the bioavailability of further drugs as previous study used nanocomposite constructed on MOF nanoparticle integrated microspheres for oral insulin delivery [19]. Moreover, another investigation improved the genistein bioavailability via its formulation into the metal–organic framework MIL-100(Fe) [20]. In addition, previous study enhanced the bioavailability of water-insoluble drug, valsartan, loaded by cyclodextrin metal organic framework [21].

Synthesis of MOFs

To create MOFs, metal salts and organic ligands are usually combined in solvothermal processes at comparatively low temperatures (beneath 300 ℃). The final structure is determined in large part by the ligand's properties. Furthermore, the structure of the MOF is influenced by the tendency of metal ions to take on geometries. High boiling, polar solvents such acetonitrile, dialkylformamides, dimethyl sulfoxide, or water are used to combine the reactants. Temperature, the quantities of the metal salt and ligand (vary widely), the degree of solubility of the reactants in the solvent, and the pH of the solution are the most crucial factors in solvothermal MOF production.

The literature describes a few other synthesis techniques in addition to this conventional one, such as the combination of non-miscible solvents [22], an electrochemical route [23], and a high-throughput approach [24]. Microwave irradiation (frequency range from 300 MHz to 300 GHz) is one of the best favorable substitutes since it offers access to a broad range of temperatures and may be utilized to adjust particle size distribution and face shape while reducing crystallization periods [25]. The usual absence of crystal formation big enough to get adequate structural data is a major drawback of this method.

Synthetic approaches of MOFs

Hydro (solvo) thermal method

When using a hydrothermal method, heterogeneous reaction occurs in the existence of aqueous solvents and mineralizers at high temperatures (150 °C to 220 °C) as the temperature often dictates reaction kinetics and particle formation, at reaction time 12 h to several days which may influence the morphology and size of the synthesized particles and pressures (2 to 10 MPa) [26]. Hydrothermal techniques have historically been used for producing big crystals and for extracting metals. More research has been done in current years on the advantages of using the hydrothermal approach in crystal engineering. For MOFs, hydrothermal synthesis is interesting for two purposes:

Foremost, it is probable to decrease the solubility of hard organic. Second, by employing equal investigational settings, the nucleation procedure can be initiated immediately to create uncommon complexes [27]. These conditions favor the action of precursor mobilization because they lower the viscosity. Phases of organization networks or MOFs that are thermodynamically metastable can be separated under these circumstances [28].

Microwave and ultrasonic methods

With the benefits of lowering crystallization timeframes, controlling shape, and distributing particle size, microwave irradiation has been improved to produce inorganic or organic solid resources. Synthetic organic chemistry has made vast manipulation of electromagnetic-radiation. Crystals formed by microwave synthesis exhibit good physical and textural similarities to those produced by conventional hydrothermal synthesis. The first MOF to effectively be entirely synthesized by MW irradiation was MIL-100.

The X-ray diffraction pattern of Materials Institute Lavoisier (MIL 100) formed by MW irradiation and the identical sample produced by hydrothermal heating (reaction conditions: 493K, 4days) agreed. Additionally, the yields were rather equivalent. This work exhibits that the microwave irradiation approach might synthesize MOF materials in a short time [29].

The fundamental idea of microwave-aided synthesis is the interaction of electric charges with electromagnetic radiation, which might involve solid ions and electrons or polar solvent and molecules in solution. The solid's electrical resistance causes an electric current to flow through it.

When temperature rises (above 300℃) in the liquid phase, molecules' kinetic energy rises as well, increasing the likelihood of polar molecules colliding when frequency is applied in an electromagnetic field. Examples of metal-organic polymers produced using this technique are Ferric-MIL-100, Cr-MIL-101, and MOF-5. Ionic liquids are excellent microwave absorption agents in addition to traditional solvents because of their distinctive polarizability and conductivity, which make them the best solvent options for microwave synthesis [29, 30].

Electrochemical synthesis (EC)

EC synthesis poses a diverse method that is reasonable. Since metal doesn’t suppress counter ions as nitrate, this method's major advantages are its purity. This technique encompasses establishing metal ions as an alternative for metal salt at the anode, while hiring an organic linker at the cathode and supplying the electrochemical-cell with salt [31]. The material produced by an electrochemical procedure employing copper plates as the anode and benzene tricarboxylate as the cathode in methanol is named Cupper-MOF. Within 150 min, a greenish-blue Cu-MOF precipitate appeared (reaction conditions: 12–19V, 1.3A), Zinc-imadazolate, HKUST-1, MOFs have manufactured by employing this approach [32].

Mechanochemical synthesis

Volatile organic solvents are environmental contaminants with numerous consequences for green chemistry. Based on two significant advantages, namely, synthesis under solvent-free conditions, which eliminates the need for organic solvents, and short reaction (30 min to 6 h) with quantitative yield mechanic chemical synthesis was proposed as an explanation to the solvent-related issues in the manufacture of porous MOF materials. The current density values used in the synthesis process (e. g., 1 mA/cm² to 10 mA/cm²). Mechanical force can cause chemical reactions as well as physical changes, which developed the foundation of mechanochemical synthesis. Mechanochemical method employs metal precursors and bridging organic ligands construct detached coordination complexes with reorientation of intramolecular bonds, leading to reaction. One potential drawback of mechanochemical synthesis is the possible generation of particles with a broad size distribution. Due to the nature of the mechanical forces (grinding or milling), particles can sometimes vary in size, which may affect the uniformity of the final product. This issue could be exacerbated by factors such as milling time, pressure, or the type of grinding media used. Another limitation is the potential for reduced crystallinity in the synthesized materials. The mechanical energy applied during the process can cause the amorphization of materials, leading to lower crystallinity. This can affect the properties of the final product, such as its stability or functionality. For some applications, this reduction in crystallinity may be undesirable. Although mechanochemical synthesis can be energy-efficient, the energy input required can vary depending on the type of equipment used and the specific reaction. In some cases, high-energy inputs can be necessary to achieve the desired reaction, which may negate some of the green chemistry advantages.

Diffusion method

The solutions encompassing metal salts and organic ligands are blended to create microcrystals of powder that are improper for X-ray diffraction. Diffusion techniques are utilized to defeat the manufacture of polycrystalline powder. Larger crystals that are suitable for X-ray diffraction analysis are generated by the two solutions diffusing slowly and steadily. Three discrete layers are formed, which leads to the growth of the crystal. Precipitant solvent exists in the first layer, product solvent is offered in the second, and a third layer separates the two layers and enables low-rate diffusion. The development of crystals occurs at the interface among the layers because of the migration of solvents between them. The gradual diffusion of reactants through gels is an additional method [33].

Solvent evaporation and ionothermal

By enhancing the mother liquor's substance, crystals are fabricated employing this procedure at temperature range of 100 °C to 300 °C with reaction time of several hours to a few days. Reactants are merged in the solvent while being blended to create a clear solution. The reaction mixture is shielded with parafilm. Crystal growth might be established by chilling the solution, eliminating excess solvent. Zhang et al. employed this solvent evaporation approach to create copper (II)–lanthanide (III) MOF. MOFs were also engineered and synthesized by means of flexible and beneficial ionothermal techniques. The hydrothermal synthesis, which employs water, is equivalent to the ionothermal approach. Because of their unique characteristics, which comprise low volatility, weak coordination, and high ionic conductivity, ionic liquids are thought of as safe and innovative solvents for the process [34].

When crystalline solids are being arranged, ionic liquids act as both solvents and template, guiding. The design of MOFs may combine elements as structural directing, chiral induction impacts, and anion control because of using ionic liquids as solvents in the combination [35].

Influence of experimental conditions on MOF

The coordination geometry of metal ions, the organic linker's nature (ligand length, bulkiness, etc.), the organic linker ratio, pH, solvent worked, and the choice of precursor materials all affect the overall structure and are subjective factors in engineering. As mentioned before, altering the solvent and reaction temperature has resulted in a variety of coordination topologies [36]. In order to construct and develop new metal–organic ligand bonds, a great effort has been put into selecting organic linkers and improving the reaction conditions. Because of their exceptional rigidity, stability, and variety of coordination modes, ligands especially multidentate ligands like aromatic carboxylates and N-containing carboxylates like pyridyl, pyrozole, azolate, and thiazole groups. Apart from the coordination bonding, they can also be thought of as hydrogen bond donors and acceptors in the construction of MOFs, based on the deprotonation of their carboxylic groups [37].

Application and challenges of MOF

Electronic devices and sensors

A few variables, including reduced cost, increased functional complexity, and the potential for device downsizing in the direction of Moore's law, are driving the microelectronics industry's shift from inorganics to organic-based materials. Although most MOFs are electrical insulators, in recent years, design techniques for creating electronically conductive MOFs have surfaced [38].

Electronic conductivity is essential for the use of MOFs in digital circuits and thermoelectric devices; however, it is not a requirement for all MOF-devices. Through-bond conduction and other techniques are used to build electronically conductive MOFs, and conduction helped by guest molecules. However, a few obstacles need to be addressed before MOFs are widely used in commercial electronics applications. A recent thorough analysis discusses a high-level strategy for tackling the wider range of issues related to integrating MOFs with electronic devices and sensors [39]. Only a few of the major issues in relation to MOF mechanical properties are presented here. The phase at which the MOF is integrated into the device will determine the mechanical property criteria that need to be fulfilled from the perspective of device manufacture. Thin film deposition, patterning, doping, etching are the steps that make up microfabrication procedures, like those utilized for integrated circuits. For example, when the MOF coating is subjected to unpredictable climatic conditions, its resistance to abrasion will be important. A proven method for determining this characteristic is nano-scratching, which can also reveal information on adhesion characteristics by defining the employed force necessary for delamination [40].

Cu (CHDA) (CHDA = trans-cyclohexane-1,4-dicarboxylate) was the structure with the highest Young's modulus and hardness, the greatest scratch and wear resistance, and an elastic recovery comparable to that of organic polymers and nanocomposites, according to the results of this characterization method applied to a few dense, electrochemically grown MOF [41].

The elastic recovery of Cu (INA)2 (INA = isonicotinate) was like that of a scratched zeolite mordenite framework inverted (MFI) film. Because MOFs often have less hardness than pure inorganics, more care must be taken during any postprocessing manufacturing stages. Additionally, consideration should be given to the potential interfacial stresses that may arise between layers when MOFs are integrated into devices using a layer-by-layer microfabrication technique. For example, tensile strain from mechanical stress can cause film debonding or cracking, which can result in device failure [42].

Memory resistors have undergone bending experiments utilizing Aurum/CuBTC/Au and silver/ZIF-8/Au on PET (PET = polyethylene terephthalate) to assess such effects. The conformable character of the MOF film in these situations led to devices functioning below bending conditions that would be challenging to achieve with their inorganic substances, the authors noted with promise.

However, the effects of MOF reactions to temperature and stimulation caused by guests on device stability properties are still unknown. In these situations, strain among the MOF and its interfaced layers may emerge from the ensuing change in lattice properties. Temperature variations, for instance, might result in residual strains because the MOF's and its substrate's coefficients of thermal expansion differ, which can lead to cracking, buckling, or film delamination.

Negative thermal expansion is anticipated in some MOFs, containing the extensively researched CuBTC structure, whereas popular electronic device substrates like copper and silver shows positive thermal expansion [43]. Such effects should be considered because of the temperature variations that will occur during the growth and processing of MOF films. Moreover, temperature variations during sensor operation, such as microcantilevers, can produce interfacial tensions that impede the anticipated sensor response [44].

Gas separation and storage

The scale of stability of MOFs in the existence of moisture was thought to be a barrier to their use in gas-separation and storage applications. Design techniques for enhancing MOF chemical stability through structural elements including ligand functionalization, hydrophobicity, and metal-ligand coordination interactions that are inert toward water, have since been discovered, building on the results of research conducted as early as the 2000s. These efforts have led to the development of numerous hydrothermally stable structures that retain their surface area and crystallinity in both basic and acidic solutions [45].

Since comparatively few characterization studies have been conducted, the same level of understanding is still lacking in MOF mechanical properties. This is probably due to the large single crystals required for characterization in some cases as well as the inaccessibility of the necessary characterization equipment.

However, the quantity of mechanical classification studies is increasing gradually, and their significance is emphasized by the fact that mechanical properties will determine the modifications that MOFs go through during the processing of converting them from their as-synthesized to their application-ready state. The synthesized substance might be designed into various forms for gas separation and storage applications, such as monolith-based structures, mixed-matrix membranes, or pellets or granulates (which are frequently compacted with the help of binders or lubricants). Monoliths are practical options because of their enhanced mass and heat transfer properties and reduced pressure drops at high flow rates, even though fixed beds are frequently used to assess MOF separation effectiveness in laboratory settings [46]. The production of MOF coatings with appropriate mechanical adhesion aspects to overcome the activation heating treatment was found to be an obstacle in the investigation of CO2 capture from simulated flue gas using amine-functionalized MOF films [47]. In order to prevent film delamination, cordierite's low coefficient of thermal expansion makes it a desirable material for monoliths. The first entirely MOF-based monolith was created by Kaskel and colleagues using an extrusion method with CuBTC, methoxy functionalized siloxane ether, and methyl hydroxyl propyl cellulose as additions. After activation, this monolith demonstrated remarkable mechanical capabilities, with a strength of 320 N, or about 3× that of a commercial cordierite honeycomb. Mixed matrix membranes are particularly appealing as scalable and energy-efficient separation technologies because they can combine the separation capabilities of MOFs with the processability of polymers [47]. The consequences of adding MOFs to composite polymer systems are still a significant unanswered question because many of the flexibility-driven adsorption of MOFs have been seen in their single crystal forms. A recent theoretical investigation on this subject used finite element modeling to predict the macroscopic properties of MOF integrated into mixed matrix membranes with different characteristics [48].

It was determined that soft matrix polymers, which are softer than the adsorbent itself growth in the adsorbent's effective bulk modules occur because of the variation in the adsorbent's effective bulk modulus caused by different thicknesses and encapsulating matrix properties. The adsorption community would be very interested in future research examining the circumstances under which elasticity-induced properties, including the gate opening and breathing behaviors seen in MOFs, can be maintained in their polymer matrix form. Onboard fuel tanks that store hydrogen and natural gas are volume-limited applications that necessitate some sculpting of the MOF from its as-synthesized state. The material's porosity, crystallinity, and gas storage properties may be jeopardized by this densification. For example, it has been demonstrated that compacting CuBTC into wafers significantly reduces its competence because of partial structural collapse, even if it is a highly effective material for room-temperature volumetric methane storage [49]. Müller and colleagues investigated the effects of powder densification on the hydrogen storage capacity of MOF-5 in a study with implications for hydrogen storage. They found that the ideal material density was ≈0.5 g cm−3. Its gravimetric excess capacity is reduced to higher densities because of significant decreases in pore volume and surface area as well as amorphization. Llewellyn and colleagues recently conducted a comprehensive investigation that examined the effects of employing a polyvinyl-based binder to shape powders into spheres. While the materials' gravimetric uptakes declined in the sphere compared to powder form, the volumetric uptake based on the bulk density exhibited the opposite trend, according to the adsorption isotherms and enthalpies of adsorptions for eight distinct gases. The porosity and crystallinity aspects brought on by compression will probably determine the proper degree of densification for a particular storage application, and as a result, it will be heavily influenced by the mechanical properties of the structure. This emphasizes the significance of further characterization studies to determine the mechanical structure-property of MOFs [50].

Recommendations for MOF synthesis

Surface modification is one of the most effective ways to enhance both stability and biocompatibility of MOFs. By introducing specific functional groups onto the surface of the MOFs, we can modify their interactions with the environment and surrounding biological systems. Surface functionalization can alter the hydrophobicity or hydrophilicity of the MOF surface, which in turn influences aqueous stability. Hydrophilic functional groups such as carboxylates or amines can improve the dispersion of MOFs in aqueous solutions and reduce aggregation, which is often a cause of instability. Aromatic groups or polyethylene glycol (PEG): The attachment of hydrophilic groups like PEG can reduce the toxicity of MOFs by creating a protective shell around the MOF particles, minimizing direct contact with cells and reducing cytotoxicity. PEGylation also enhances the biocompatibility and solubility of MOFs in physiological conditions [51].

Further, coating MOFs with biocompatible polymers can enhance their stability and biocompatibility. Polymeric coatings provide a protective barrier around MOFs, shielding them from environmental factors like pH fluctuations or oxidative conditions and preventing the release of toxic byproducts into the surrounding medium. Common coatings include polymers such as polylactic acid (PLA), polyethylene glycol (PEG), polylactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA), and chitosan. These coatings can improve the aqueous stability of MOFs and also facilitate their controlled release of encapsulated drugs or antigens. Polymer coatings can improve the structural integrity of MOFs in biological systems by preventing moisture absorption or solvent-induced degradation, which is particularly critical for MOFs that are sensitive to water or pH changes. The polymeric shell also helps in reducing the cytotoxic effects of MOFs by providing a biocompatible surface for interaction with cells, thus preventing direct contact with the metal centers or organic linkers that could trigger toxicity [52].

Modifying the ligands attached to the metal centers in MOFs is another effective strategy to enhance both stability and cytotoxicity. The ligand plays a role in controlling the chemical properties, stability, and solubility of MOFs. By introducing functional groups such as amine, carboxyl, or phosphine groups, the stability of MOFs can be improved, as these modifications can reduce the solubility of metal ions in aqueous environments, preventing their leaching into the surrounding medium. Ligand modification can also reduce the toxicity of the MOFs by preventing metal ion release, which could otherwise cause cellular damage. Additionally, biocompatible ligands like amino acids or polysaccharides can be used to replace traditional organic linkers, offering better biocompatibility [53].

Future applications

Recent developments in synthetic methods to produce modular MOF-Nanoparticles (NPs) [54], with control over particle size, and surface aspects were compiled here [55], MOF-NPs will become a favorable class of functional nanomaterials with the potential to have a major impact on the domains of catalysis [56], separations [57], and nanomedicine [58] thanks to these developments as well as further advancements in synthesis and characterization techniques. Despite the impressive advancements, there is still much space for improvement in our comprehension of the essential aspects of MOF-NP synthesis. Specifically, it is still mostly speculative to explain the early mechanisms of particle nucleation and how variables like temperature, solvent, and modulators impact these fundamental events. Therefore, better mechanistic knowledge of nucleation and crystal development will significantly enhance our capacity to transform MOF-NP synthesis from a discipline based on conjecture to one that is highly predictable. Enhancing the capacity to consistently synthesize MOF-NPs with excellent homogeneity and at desirable sizes between 10 and 200 nm should continue to be a key objective for this sector. Two primary factors make NPs in this size range appealing:

1) Large exterior surface area and quick diffusion kinetics are linked to site-isolated catalysis and 2) size-dependent bioavailability for use as biological probes and possibly even as therapeutic agents. The development of seed-mediated MOF NP synthesis techniques and the ongoing refinement of strategies to successfully separate nucleation and growth processes are examples of potential advancements in these domains [59].

Beyond gaining a better understanding of particle growth, there are other opportunities to make significant contributions to this field, such as: developing MOF-NPs with large pores (>3 nm) that can encapsulate and deliver biomolecules; improving diffraction-based techniques for in situ characterization; and modulating the chemical stability MOF-NPs via surface functionalization, creating MOF-NPs that can transport and encapsulate biomolecules with large holes (>3 nm) [60], and systematically evaluating MOF NP pharmacokinetics in vivo.

Although medical applications (table 1) have received most of the attention in the development of MOF NPs thus far, the usage of MOF NP as building blocks in mixed-matrix membranes and colloidal crystal fabrication of ordered 3D metamaterials and devices offers an intriguing alternative [61].

For example, by utilizing the exceptionally high surface areas of MOF NPs and the desirable mechanical qualities of polymeric matrices, uniform MOF NPs could be incorporated into membranes to optimize their potential separation and catalysis capabilities [62]. Because MOFs and polymers have tunable chemistry, such pairings will unavoidably result in a wide range of material characteristics and functionalities [63].

We believe that a wide variety of stimuli-responsive materials generated from MOF NP will become crucial building blocks for artificial skin, with flexible sensors and adaptable membranes [64]. Furthermore, because of their porosity, customizable host-guest interactions, and chemical and physical modularity’s, hierarchical materials made of self-assembled MOF NP building blocks are thought to have characteristics distinct from those shown by typical inorganic NPs [65]. For, MOF NP building blocks-all of which are entropically driven to form closed-packed assemblies, have not been used to create many examples of organized structures [66]. Conversely, inorganic NPs can be assembled into a vast library of well-defined structures using enthalpically driven assembly techniques, which are reliable and modular tools. This has mostly been accomplished by surface functionalizing NP with programmable ligands, like oligonucleotides, which allows for the creation of hybrid superstructures with many functional units, enthalpically favorable topologies, and adjustable interparticle distances [67].

Table 1: Summary of metal-organic framework nano-system utilized in drug delivery

| MOF | Drug delivered | Pore size | Release profile | Cytotoxicity | References |

| ZIF-8 | doxorubicin | 12 | 35.6% even after 60 h at pH = 7.4. | MTT assay results confirm that the PAA@ZIF-8 NPs are nearly nontoxic against MCF-7 cells and can be applied in the biomedical field with good biocompatibility. | [68] |

| MIL-100 | Brimonidine tartrate | 25 and 29 | 3-5 d | Cytotoxicity tests using retinal photoreceptor cells (661W) showed the safety of MOF. | [69] |

| MIL-101 | Cisplatin | 29 and 34 | 6 d | Treatment of HT-29 cells with nanoparticles of 1c@silica showed appreciable cytotoxicity (IC50=29μM); however, it was slightly less cytotoxic than cisplatin under the same conditions (IC50=20 μM). | [70] |

| NU-1000 | Insulin | 12 and 30 | In (pH = 1.29), only 10% of insulin was released after 60 min | - | [71] |

CONCLUSION

MOFs have a lot of potential for delivering cellular and bio-macromolecular treatments. Using MOFs as part of a delivery system that is specifically designed to load and protect biomolecules or cells is easy to imagine. The final treatment would then be formulated using post-loading changes, such as membrane coating or polymeric nanoparticle encapsulation. In vivo, these kinds of composite vehicle strategies are starting to show potential. Lastly, to guarantee appropriate intracellular handling of the transported load, more research on MOF therapies will be needed, particularly for nucleic acid treatments. Given the distinctions between in vitro and in vivo testing, it is imperative that future research focuses on in vivo assessment of MOF drug delivery agents. Similarly, a lot of work has been done with simulated drug molecules. To hasten the transition to clinical applications, future research should concentrate on real medicinal molecules. Since the transport of these species is currently poorly understood, more proof-of-concept research is still required for vaccines and cell-based treatments. Additionally, more research is required to determine whether MOFs and medications can work in concert. It will also be necessary to investigate other disease target specifically, those other than cancer—and maybe new targeting techniques to produce MOFs for clinical use. More thorough research is also required to determine MOFs' immunogenicity. The use of MOFs for drug delivery has led to studies focusing on the creation of treatments that use gas transmitters and catalytic nanomedicine. Since MOFs are especially suited for certain applications, hence in vivo research, MOF-biomolecule interactions, and clinical translation techniques are expected to for further studies.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization, Reem Mohsin Khalaf Al-Uobody, Hayder A. Hammoodi and Amira Amin. Formal analysis, Reem Mohsin Khalaf Al-Uobody, Hayder A. Hammoodi and Amira Amin. Investigation, Reem Mohsin Khalaf Al-Uobody, Hayder A. Hammoodi and Amira Amin. Resources Writing-original draft preparation, Reem Mohsin Khalaf Al-Uobody, Hayder A. Hammoodi and Amira Amin. Writing—review and editing, Reem Mohsin Khalaf Al-Uobody, Hayder A. Hammoodi and Amira Amin. Supervision, Amira Amin. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Betard A, Fischer RA. Metal organic framework thin films: from fundamentals to applications. Chem Rev. 2012;112(2):1055-83. doi: 10.1021/cr200167v, PMID 21928861.

Kitagawa S, Kitaura R, Noro SI. Functional porous coordination polymers. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2004;43(18):2334-75. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300610, PMID 15114565.

Eddaoudi M, Kim J, Rosi N, Vodak D, Wachter J, O Keeffe M. Systematic design of pore size and functionality in isoreticular MOFS and their application in methane storage. Science. 2002;295(5554):469-72. doi: 10.1126/science.1067208, PMID 11799235.

Leus K, Bogaerts T, De Decker J, Depauw H, Hendrickx K, Vrielinck H. Systematic study of the chemical and hydrothermal stability of selected stable metal organic frameworks. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials. 2016 May 15;226:110-6. doi: 10.1016/j.micromeso.2015.11.055.

Han Y, Liu W, Huang J, Qiu S, Zhong H, Liu D. Cyclodextrin-based metal organic frameworks (CD-MOFs) in pharmaceutics and biomedicine. Pharmaceutics. 2018;10(4):271. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics10040271, PMID 30545114.

McKinlay AC, Eubank JF, Wuttke S, Xiao B, Wheatley PS, Bazin P. Nitric oxide adsorption and delivery in flexible MIL-88(Fe) metal organic frameworks. Chem Mater. 2013;25(9):1592-9. doi: 10.1021/cm304037x.

Kalmutzki MJ, Hanikel N, Yaghi OM. Secondary building units as the turning point in the development of the reticular chemistry of MOFs. Sci Adv. 2018;4(10):eaat9180. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aat9180, PMID 30310868.

Liang K, Ricco R, Doherty CM, Styles MJ, Bell S, Kirby N. Biomimetic mineralization of metal organic frameworks as protective coatings for biomacromolecules. Nat Commun. 2015;6(1):7240. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8240, PMID 26041070.

Teplensky MH, Fantham M, Poudel C, Hockings C, Lu M, Guna A. A highly porous metal-organic framework system to deliver payloads for gene knockdown. Chem. 2019;5(11):2926-41. doi: 10.1016/j.chempr.2019.08.015.

Chen TT, Yi JT, Zhao YY, Chu X. Biomineralized metal organic framework nanoparticles enable intracellular delivery and endo-lysosomal release of native active proteins. J Am Chem Soc. 2018;140(31):9912-20. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b04457, PMID 30008215.

Luo Z, Jiang L, Yang S, Li Z, Soh WM, Zheng L. Light-induced redox-responsive smart drug delivery system by using selenium-containing polymer@MOF Shell/Core nanocomposite. Adv Healthc Mater. 2019;8(15):e1900406. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201900406, PMID 31183979.

Serhan M, Sprowls M, Jackemeyer D, Long M, Perez ID, Maret W. Total iron measurement in human serum with a smartphone. IEEE J Transl Eng Health Med. 2020;8:1-9.

Chen WH, Yu X, Liao WC, Sohn YS, Cecconello A, Kozell A. ATP-responsive aptamer-based metal organic framework nanoparticles (NMOFs) for the controlled release of loads and drugs. Adv Funct Materials. 2017;27(37):1702102. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201702102.

Horcajada P, Chalati T, Serre C, Gillet B, Sebrie C, Baati T. Porous metal organic framework nanoscale carriers as a potential platform for drug delivery and imaging. Nat Mater. 2010;9(2):172-8. doi: 10.1038/nmat2608, PMID 20010827.

Chen J, Sheng D, Ying T, Zhao H, Zhang J, Li Y. MOFs-based nitric oxide therapy for tendon regeneration. Nanomicro Lett. 2020;13(1):23. doi: 10.1007/s40820-020-00542-x, PMID 34138189.

Filippousi M, Turner S, Leus K, Siafaka PI, Tseligka ED, Vandichel M. Biocompatible Zr-based nanoscale MOFs coated with modified poly(ε-caprolactone) as anticancer drug carriers. Int J Pharm. 2016;509(1-2):208-18. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2016.05.048, PMID 27235556.

Zhu W, Guo J, Amini S, Ju Y, Agola JO, Zimpel A. Supra cells: living mammalian cells protected within functional modular nanoparticle-based exoskeletons. Adv Mater. 2019;31(25):e1900545. doi: 10.1002/adma.201900545, PMID 31032545.

Ding LG, Shi M, Yu ED, Xu YL, Zhang YY, Geng XL. Metal organic framework-based delivery systems as nanovaccine for enhancing immunity against porcine circovirus type 2. Mater Today Bio. 2025;32:101712. doi: 10.1016/j.mtbio.2025.101712, PMID 40230641.

Zhou Y, Liu L, Cao Y, Yu S, He C, Chen X. A nanocomposite vehicle based on metal organic framework nanoparticle incorporated biodegradable microspheres for enhanced oral insulin delivery. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2020;12(20):22581-92. doi: 10.1021/acsami.0c04303, PMID 32340452.

Botet Carreras A, Tamames Tabar C, Salles F, Rojas S, Imbuluzqueta E, Lana H. Improving the genistein oral bioavailability via its formulation into the metal organic framework MIL-100(Fe). J Mater Chem B. 2021;9(9):2233-9. doi: 10.1039/d0tb02804e, PMID 33596280.

Zhang W, Guo T, Wang C, He Y, Zhang X, Li G. MOF capacitates cyclodextrin to mega-load mode for high efficient delivery of valsartan. Pharm Res. 2019;36(8):117. doi: 10.1007/s11095-019-2650-3, PMID 31161271.

Forster PM, Thomas PM, Cheetham AK. Biphasic solvothermal synthesis: a new approach for hybrid inorganic-organic materials. Chem Mater. 2002;14(1):17-20. doi: 10.1021/cm010820q.

Mueller U, Schubert M, Teich F, Puetter H, Schierle Arndt K, Pastre J. Metal organic frameworks: prospective industrial applications. J Mater Chem. 2006;16(7):626-36. doi: 10.1039/B511962F.

Stock N. High-throughput investigations employing solvothermal syntheses. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials. 2010;129(3):287-95. doi: 10.1016/j.micromeso.2009.06.007.

Jhung SH, Yoon JW, Hwang JS, Cheetham AK, Chang JS. Facile synthesis of nanoporous nickel phosphates without organic templates under microwave irradiation. Chem Mater. 2005;17(17):4455-60. doi: 10.1021/cm047708n.

Colak AT, Pamuk G, Yesilel OZ, Yuksel F. Hydrothermal synthesis and structural characterization of Zn(II) and Cd(II)-pyridine-2,3-dicarboxylate 2D coordination polymers {(NH4)2[M(μ-pydc)2]·2H2O}n. Solid State Sci. 2011;13(12):2100-4. doi: 10.1016/j.solidstatesciences.2011.08.006.

Gangu KK, Maddila S, Mukkamala SB, Jonnalagadda SB. A review on contemporary metal-organic framework materials. Inorg Chim Acta. 2016 May 1;446:61-74. doi: 10.1016/j.ica.2016.02.062.

ferey G, Mellot Draznieks C, Serre C, Millange F, Dutour J, Surble S. A chromium terephthalate based solid with unusually large pore volumes and surface area. Science. 2005;309(5743):2040-2. doi: 10.1126/science.1116275, PMID 16179475.

Jhung SH, Lee JH, Forster PM, Ferey G, Cheetham AK, Chang JS. Microwave synthesis of hybrid inorganic-organic porous materials: phase selective and rapid crystallization. Chemistry. 2006;12(30):7899-905. doi: 10.1002/chem.200600270, PMID 16871506.

Gangu KK, Maddila S, Mukkamala SB, Jonnalagadda SB. A review on contemporary metal organic framework materials. Inorg Chim Acta. 2016 May 1;446:61-74. doi: 10.1016/j.ica.2016.02.062.

Mueller U, Schubert M, Teich F, Puetter H, Schierle Arndt K, Pastre J. Metal organic frameworks prospective industrial applications. J Mater Chem. 2006;16(7):626-36. doi: 10.1039/B511962F.

Schlesinger M, Schulze S, Hietschold M, Mehring M. Evaluation of synthetic methods for microporous metal organic frameworks exemplified by the competitive formation of [Cu2(btc)3(H2O)3] and [Cu2(btc)(OH)(H2O)]. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials. 2010;132(1-2):121-7. doi: 10.1016/j.micromeso.2010.02.008.

Xue M, Ma S, Jin Z, Schaffino RM, Zhu GS, Lobkovsky EB. Robust metal-organic framework enforced by triple framework interpenetration exhibiting high H2 storage density. Inorg Chem. 2008;47(15):6825-8. doi: 10.1021/ic800854y, PMID 18582032.

Lin Z, Wragg DS, Warren JE, Morris RE. Anion control in the ionothermal synthesis of coordination polymers. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129(34):10334-5. doi: 10.1021/ja0737671, PMID 17676849.

Zhang J, Wu T, Chen S, Feng P, Bu X. Versatile structure directing roles of deep eutectic solvents and their implication in the generation of porosity and open metal sites for gas storage. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2009;48(19):3486-90. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900134, PMID 19343752.

Li JB, Dong XY, Cao LH, Zang SQ, Mak TC. N-donor ligand-mediated assembly of divalent zinc and cadmium coordination polymers based on 2,3,2′,3′-thiaphthalic acid: structures and properties. Cryst Eng Comm. 2012;14(13):4444-53. doi: 10.1039/c2ce06705f.

Zhou JM, Shi W, Li HM, Li H, Cheng P. Experimental studies and mechanism analysis of high sensitivity luminescent sensing of pollutional small molecules and ions in ln 4 o 4 cluster based microporous metal organic frameworks. J Phys Chem C. 2014;118(1):416-26. doi: 10.1021/jp4097502.

Sun L, Campbell MG, Dinca M. Elektrisch leitfahige porose metall organische gerustverbindungen. Angew Chem. 2016;128(11):3628-42. doi: 10.1002/ange.201506219.

Stassen I, Burtch N, Talin A, Falcaro P, Allendorf M, Ameloot R. An updated roadmap for the integration of metal organic frameworks with electronic devices and chemical sensors. Chem Soc Rev. 2017;46(11):3185-241. doi: 10.1039/c7cs00122c, PMID 28452388.

Wong M, Lim GT, Moyse A, Reddy JN, Sue HJ. A new test methodology for evaluating scratch resistance of polymers. Wear. 2004;256(11-12):1214-27. doi: 10.1016/j.wear.2003.10.027.

Van De Voorde B, Ameloot R, Stassen I, Everaert M, De Vos D, Tan JC. Mechanical properties of electrochemically synthesised metal-organic framework thin films. J Mater Chem C. 2013;1(46):7716-24. doi: 10.1039/c3tc31039f.

Lewis J. Material challenge for flexible organic devices. Materials Today. 2006;9(4):38-45. doi: 10.1016/S1369-7021(06)71446-8.

Peterson VK, Kearley GJ, Wu Y, Ramirez Cuesta AJ, Kemner E, Kepert CJ. Local vibrational mechanism for negative thermal expansion: a combined neutron scattering and first principles study. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2010;49(3):585-8. doi: 10.1002/anie.200903366, PMID 19998291.

Shen F, Lu P, O Shea SJ, Lee KH, Ng TY. Thermal effects on coated resonant microcantilevers. Sens Actuat A. 2001;95(1):17-23. doi: 10.1016/S0924-4247(01)00715-4.

Burtch NC, Jasuja H, Walton KS. Water stability and adsorption in metal-organic frameworks. Chem Rev. 2014;114(20):10575-612. doi: 10.1021/cr5002589, PMID 25264821.

Heck RM, Gulati S, Farrauto RJ. The application of monoliths for gas-phase catalytic reactions. Chem Eng J. 2001;82(1-3):149-56. doi: 10.1016/S1385-8947(00)00365-X.

Darunte LA, Terada Y, Murdock CR, Walton KS, Sholl DS, Jones CW. Monolith supported amine functionalized Mg2(dobpdc) adsorbents for CO2 capture. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9(20):17042-50. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b02035, PMID 28440615.

Evans JD, Coudert FX. Macroscopic simulation of deformation in soft microporous composites. J Phys Chem Lett. 2017;8(7):1578-84. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.7b00397, PMID 28325040.

Peng Y, Krungleviciute V, Eryazici I, Hupp JT, Farha OK, Yildirim T. Methane storage in metal organic frameworks: current records, surprise findings and challenges. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135(32):11887-94. doi: 10.1021/ja4045289, PMID 23841800.

Chanut N, Wiersum AD, Lee UH, Hwang YK, Ragon F, Chevreau H. Observing the effects of shaping on gas adsorption in metal organic frameworks. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2016;2016(27):4416-23. doi: 10.1002/ejic.201600410.

Figueroa Quintero L, Villalgordo Hernandez D, Delgado Marin JJ, Narciso J, Velisoju VK, Castano P. Post-synthetic surface modification of metal-organic frameworks and their potential applications. Small Methods. 2023;7(4):e2201413. doi: 10.1002/smtd.202201413, PMID 36789569.

Li C, Liu J, Zhang K, Zhang S, Lee Y, Li T. Coating the right polymer: achieving ideal metal organic framework particle dispersibility in polymer matrixes using a coordinative crosslinking surface modification method. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2021;60(25):14138-45. doi: 10.1002/anie.202104487, PMID 33856717.

Tao B, Zhao W, Lin C, Yuan Z, He Y, Lu L. Surface modification of titanium implants by ZIF-8@Levo/lBL coating for inhibition of bacterial-associated infection and enhancement of in vivo osseo integration. Chem Eng J. 2020 Jun 15;390:124621. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2020.124621.

Imam SS. Nanoparticles: the future of drug delivery. Int J Curr Pharm Sci. 2023;15(6):8-15. doi: 10.22159/ijcpr.2023v15i6.3076.

Abdellatif MM, Ahmed SM, El Nabarawi MA, Teaima M. Nano-delivery systems for enhancing oral bioavailability of drugs. Int J App Pharm. 2023;15(1):13-9. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2023v15i1.46758.

Lee J, Farha OK, Roberts J, Scheidt KA, Nguyen ST, Hupp JT. Metal organic framework materials as catalysts. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38(5):1450-9. doi: 10.1039/b807080f, PMID 19384447.

Bachman JE, Smith ZP, Li T, Xu T, Long JR. Enhanced ethylene separation and plasticization resistance in polymer membranes incorporating metal-organic framework nanocrystals. Nat Mater. 2016;15(8):845-9. doi: 10.1038/nmat4621, PMID 27064528.

He C, Liu D, Lin W. Nanomedicine applications of hybrid nanomaterials built from metal ligand coordination bonds: nanoscale metal organic frameworks and nanoscale coordination polymers. Chem Rev. 2015;115(19):11079-108. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00125, PMID 26312730.

Doherty CM, Buso D, Hill AJ, Furukawa S, Kitagawa S, Falcaro P. Using functional nano and microparticles for the preparation of metal organic framework composites with novel properties. Acc Chem Res. 2014;47(2):396-405. doi: 10.1021/ar400130a, PMID 24205847.

Shen K, Zhang L, Chen X, Liu L, Zhang D, Han Y. Ordered macro-microporous metal organic framework single crystals. Science. 2018;359(6372):206-10. doi: 10.1126/science.aao3403, PMID 29326271.

Fratzl P, Weinkamer R. Nature’s hierarchical materials. Prog Mater Sci. 2007;52(8):1263-334. doi: 10.1016/j.pmatsci.2007.06.001.

Seoane B, Coronas J, Gascon I, Etxeberria Benavides ME, Karvan O, Caro J. Metal organic framework based mixed matrix membranes: a solution for highly efficient CO2 capture? Chem Soc Rev. 2015;44(8):2421-54. doi: 10.1039/c4cs00437j, PMID 25692487.

Joshi P, Nainwal N, Morris S, Jakhmola V. A review on recent advances on stimuli-based smart nanomaterials for drug delivery and biomedical application. Int J App Pharm. 2023;15(5):48-59. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2023v15i5.48186.

Akifulhaque M, Shivacharan GR, Parveen MD, Shanthi Priya DK, Kumar Reddy Konatham T, Vallakeerthi N. Sensor applications in analysis of drugs and formulations. Int J Appl Pharm Sci Res. 2021;14(11):57-62. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2021v14i11.41134.

Wu HB, Lou XW. Metal organic frameworks and their derived materials for electrochemical energy storage and conversion: promises and challenges. Sci Adv. 2017;3(12):eaap9252. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aap9252, PMID 29214220.

Glotzer SC, Solomon MJ. Anisotropy of building blocks and their assembly into complex structures. Nat Mater. 2007;6(8):557-62. doi: 10.1038/nmat1949, PMID 17667968.

Park SY, Lytton Jean AK, Lee B, Weigand S, Schatz GC, Mirkin CA. DNA-programmable nanoparticle crystallization. Nature. 2008;451(7178):553-6. doi: 10.1038/nature06508, PMID 18235497.

Ren H, Zhang L, An J, Wang T, Li L, Si X. Polyacrylic acid@zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 nanoparticles with ultrahigh drug loading capability for pH-sensitive drug release. Chem Commun (Camb). 2014;50(8):1000-2. doi: 10.1039/c3cc47666a, PMID 24306285.

Gandara Loe J, Ortuno Lizaran I, Fernandez Sanchez L, Alio JL, Cuenca N, Vega Estrada A. Metal organic frameworks as drug delivery platforms for ocular therapeutics. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2019;11(2):1924-31. doi: 10.1021/acsami.8b20222, PMID 30561189.

Taylor Pashow KM, Della Rocca J, Xie Z, Tran S, Lin W. Postsynthetic modifications of iron carboxylate nanoscale metal organic frameworks for imaging and drug delivery. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131(40):14261-3. doi: 10.1021/ja906198y, PMID 19807179.

Chen Y, Li P, Modica JA, Drout RJ, Farha OK. Acid-resistant mesoporous metal-organic framework toward oral insulin delivery: protein encapsulation, protection and release. J Am Chem Soc. 2018;140(17):5678-81. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b02089, PMID 29641892.