Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 4, 2025, 117-126Review Article

RECENT INNOVATIONS IN MICROFABRICATION TECHNIQUES FOR ENHANCED MICROFLUIDIC CHIP PERFORMANCE IN DRUG DEVELOPMENT

ANKANA ROY1, VASANTHARAJU SG1, MUDDUKRISHNA BS1, BHARGAV ERANTI2, SACHIN DATTRAM PAWAR1, GUNDAWAR RAVI1*

1Department of Pharmaceutical Quality Assurance, Manipal College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, India. 2Raghavendra Institute of Pharmaceutical Education and Research-Autonomous, Anantapur-515721, Andhra Pradesh, India

*Corresponding author: Gundawar Ravi;*Email: gundawar.ravi@manipal.edu

Received: 17 Mar 2025, Revised and Accepted: 16 May 2025

ABSTRACT

An example of a mobile laboratory is microfluidic chip technology or lab-on-a-chip. It is one of the great breakthroughs in the pharmaceutical industry as it allows flexibility in controlling experiment conditions, minimizing sample and reagent waste, and allowing high-throughput screening. Microfluidics has roots in molecular analysis, microelectronics, biodefense, and even molecular biology; likewise, gas-phase chromatography and capillary electrophoresis are ancestors for it. Determining the use of this equipment in laboratories leads to automation, miniaturization of procedures, precision and uncertainty in drug creation, and repeatable experiments, which enhances the accuracy of results. Its merits are the performance of computerized simulation of organs, where it enhances the drug screen, toxicity testing, personalized medicine, and pharmacokinetics, which leads to the testing of thousands of candidate drugs being tested at once. Its performance is excellent; however, it cannot be denied that it has a disadvantage, which is in designing the chip and integrating it with the already existing system. It has yet to integrate widely used markers for patient samples and other markers to improve point-of-care diagnostics that aim to use the patient’s sample to work on to change the structure of future studies in the pharmaceutical industry.

Keywords: Lab-on-a-chip, High-throughput screening, Microelectronics, Microfluidic technology, Molecular biology, Drug delivery systems, Point-of-care diagnostics, Biomarkers

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i4.54228 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

The pharmaceutical industry is ever-changing and requires more sophisticated, accurate, and cost-effective solutions for drug development and testing. Of all the emerging technologies the industry has access to, microfluidic chip technology is arguably the most exciting. Microfluidic chips, also known as “lab-on-a-chip,” combine different reagent functions of a laboratory onto a single chip capable of processing minute fluid volumes. Technology has the power to revolutionize pharmaceutical analysis through unparalleled accuracy in control of experimental parameters, minimized consumption of both sample and reagents and enhanced throughput [1, 2]. The four key areas of microfluidics are molecular analysis, biodefense, molecular biology and microelectronics. Microfluidics originated from microanalytical technologies, including Gas-Phase Chromatography (GPC) [1], High-Pressure Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), and Capillary Electrophoresis (CE) [3]. High efficiency of the above techniques, especially when incorporated with laser optical detection, achieved high resolution and sensitivity with the use of little sample volume. This success paved the way to the development of compact and adaptable formats for the majority of the chemical and biochemical applications [4-6].

The second impetus was the post-Cold War need to respond to chemical and biological threats. The US Department of Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) funded research in the 1990s to create field-deployable microfluidic systems for their detection, significantly advancing the academic microfluidic technology [7]. Molecular biology provided the third thrust. The genomics revolution in the 1980s and the development of high-throughput DNA sequencing required higher throughput, sensitivity, and resolution analytical tools. Microfluidics offered solutions to these issues [8, 9].

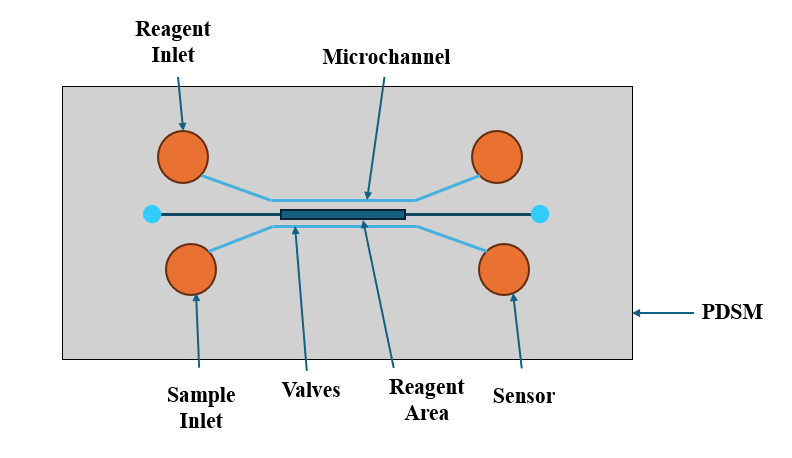

Fig. 1: Diagrammatic representation of a microfluidic chip

Finally, microelectronics added value by transferring photolithography and related technologies from silicon microelectronics and Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems (MEMS) to microfluidics [7]. Silicon and glass were employed in early microfluidic systems, but these were subsequently replaced primarily by plastics based on economic and practical reasons. Silicon, while expensive and UV and visible light opaque, was not ideally suited to standard optical detection techniques. Elastomers were more frequently employed for making components such as pumps and valves, as these are more in line with living cells [10-13].

Microfluidic chips, or "lab-on-a-chip" devices, have come a long way since their beginning. During the 1960s, the development started with microanalytical techniques such as gas-phase chromatography, high-pressure liquid chromatography, and capillary electrophoresis. The 1970s witnessed the introduction of miniaturized gas chromatograph analyzers using silicon wafers, whereas silicon micromachining technology paved the way for new microvalves and micropumps in the 1980s. The 1990s heralded the use of Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) in fabricating microfluidic chips and silicon-based microfluidic analysis chips. The 2000s experienced the emergence of soft lithography for PDMS, which supported the miniaturization and automation of lab processes. More recent literature on 2023-2024 emphasizes improvements in microfluidic-based vasculatures on chips for mimicking human blood vessel networks to be used in drug delivery and metabolism research.

Moreover, lab-on-a-chip technologies have advanced accessibility, usability, and manufacturability for enhancing clinical diagnostics and translational research. Some milestones include developing integrated circuits, photolithography, and organ-on-a-chip models with physiological mimicry of drug testing and disease modelling. Prospects include enhancing chip robustness, growing applications towards drug delivery systems and point-of-care diagnostics, and creating innovative fabrication methods to deal with the present limitations. Microfluidic technology continues to transform pharmaceutical research and development, streamlining drug discovery and making it more effective.

Microfluidic chips are very powerful tools for drug Research and Development (R and D). These tiny devices manipulate fluids with remarkable precision at the microscopic scale, enabling scientists to miniaturize and automate complex lab processes. All of this tech doesn’t only time accelerates the process of finding new drugs-it also allows for more consistent and reliable experiments, which will help us get even more accurate results. Microfluidic technology in conjunction with pharmaceutical analysis, has revealed new avenues for drug screening, toxicity testing, pharmacokinetic analysis, and personalized medicine [14, 15].

One of the key advantages of microfluidic chips is that they can conduct high-throughput screening. Since common drug screening methods are usually tedious and time-consuming, the small number of compounds that can be screened suggests that they are extremely limited. Microfluidic chips, on the other hand, have the potential to screen an ensemble of drug candidates simultaneously, significantly increasing the throughput of screening effective therapeutics. The high-throughput nature of such an assay has enabled vast compound libraries to be screened for biological activity in the early drug development phase [16, 17].

Microfluidic chips also play a fundamental role in drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics studies, in addition to high-throughput screening instrumentation. Microfluidic chips can simulate human organs' microenvironment and, thus, allow studying the drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion processes in the human body. These data are pivotal in determining the safety and efficacy profiles of new pharmacological agents. Microfluidic chips will also enable the creation of organ-on-a-chip systems with the ability to mimic the physiological response that is unique to human organs. These models are better representations of human biological systems than traditional cell culture or animal-based study designs, thus offering greater predictive sensitivity for preclinical research [18-21].

Toxicity screening is an important application of microfluidic technology to drug evaluation. Microfluidic devices' capability to quantify the toxicological action of drug candidates on various cell types lessens dependence on animal testing and yields more meaningful data on human biological processes. In addition to being more ethical, this method strengthens the validity of toxicity testing. Microfluidic chips can design complex drug delivery systems, such as nanoparticles and liposomes, which can be accurately designed and delivered directly to tissue or cells to improve treatment efficiency and minimize side effects [22-24]. Microfluidic chips are also transforming point-of-care diagnosis. The handheld, portable chips can quickly test patient samples for a set of biomarkers, facilitating quick and precise diagnosis of disease. This feature is especially important in low-resource settings where well-equipped laboratory space is limited. By providing early diagnostic information, microfluidic chips can enhance patient management and treatment outcomes [25-28].

Microfluidic chips with organ-on-a-chip technology have been presented as better alternatives to animal testing in pharmaceutical studies. Microfluidic chips can recreate human organs and organ function in a controlled microenvironment, allowing for more reliable and human-relevant models for drug toxicity and efficacy studies. Microfluidic chips can culture the living organs in this physiological state while allowing researchers to study drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and, consequently in, excretion from the body. This alternative method raises ethical considerations and experimental accuracy since animal models are often not accurate predictors of human response. However, there are challenges in validating microfluidic-toxicity-based assays in response to regulations. Reproducibility and robustness are key concerns when moving ass or toxicity work to the marketplace. It is critical to make sure that a microfluidic toxicity assay would perform the same across laboratories and experiments would yield the same results regardless of the assay performance routine. The regulatory body is expected should provide extensive validation data because we need to be confident these assays will predict human outcomes consistently. For regulatory approval, microfluidic-based assays will need to go through significant validation to show that the results will be reliable and predictable. This requires showing the ability to reproducibly obtain results between labs and reproducibility related to predicting human responses to drugs with consistent outcomes. As regulatory agencies such as the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) begin to acknowledge these New Approaches Methodologies (NAMs) they are starting the journey to incorporate them into the process of drug development. The FDA Modernization Act 2.0 even allows the exploration of non-animal-based approaches within investigational new drug applications as they begin to modernize drug development and testing for more humane approaches. Ultimately, microfluidic chips allow for fewer animal testing efforts by allowing for more accurate human representation for models of drug toxicity and efficacy. The clinical data generated from these models will have an increasing role in the regulatory process and, subsequently, the drug development process, while there will continue to be inconsistencies reaching regulatory approval with these assays, the ongoing developments and supportive legislation with regulatory agencies will enable greater acceptance of microfluidic technology for pharmaceutical research.

Microfluidic chip fabrication techniques vary widely, each with its own set of advantages and limitations. Here’s a comparative analysis of some prominent methods:

In short, the application of microfluidic chip technology to pharmaceutical analysis is a significant advance toward more efficient and effective procedures in drug development. Herein, we review microfluidic chips for multi-purpose applications in pharmaceutical analysis and their potential to revolutionize the industry. In exploring the recent advancements and potential future of microfluidic technology, we will strive to give an overarching view of the contribution of microfluidic technology to the history of pharmaceutical R and D.

Drug delivery system

They provide well-controlled synthesis and microscale drug carrier delivery ability; thus, microfluidic chip-based drug delivery systems have revolutionized drug delivery systems [29]. These chips enable the production of nanoparticles and microparticles with uniform size and shape, which are crucial for effective drug delivery. Microfluidic technologies can alter the dynamics of fluids to create high efficiency of encapsulation and targeted delivery, hence lessening drug loss and degradation [1, 29-32]. Incorporation of biosensors with real-time monitoring inside microfluidic systems facilitates fine-tuning release profiles of drugs for increased therapeutic performance and decreased adverse effects [26]. Besides, microfluidic chips allow the development of multifunctional drug carriers. Inorganic substances, polymers, and lipids are introduced into the drug carriers for achieving controlled release and targeted delivery. Microfluidic technology offers high-throughput screening and rapid prototyping, which speed up the formulation and design of new drug formulations and delivery systems [33, 34]. Ongoing research attempts to deal with problems such as scalability and integrating with the existing manufacturing process by advancing microfabrication techniques and introducing artificial intelligence in the optimization of the process [35]. Microfluidic chips present a completely novel means of drug delivery systems which allow precise control, efficiency and scalability of delivery, which can improve patient results and advance medicine. These are the ways that drug delivery is achieved with the use of microfluidic chips:

Nanoparticle and microparticle fabrication

Microfluidic chips fabricate nanoparticles and microparticles for drug encapsulation. Those particles can release drugs at controlled rates that reach tissues or cells [22, 36]. Control over microfluidic flows is applied to fabricate uniform-sized and shape particles that are crucial to stable drug delivery [37].

Fabrication techniques

Several methods of particle fabrication have been performed in microfluidics, such as droplet, continuous flow, and segmented flow techniques. Droplet-based microfluidics creates uniform droplets serving as tiny reactors for creating particles [38, 39]. Continuous flow microfluidics enables the constant production of particles by continuously blending reactants within microchannels. Segmented flow techniques employ immiscible fluids to form distinct reaction zones, providing better control over particle formation [40-42].

Table 1: Different fabrication techniques, their advantages and limitations

| Fabrication technique | Advantages | Limitations |

| Soft lithography | -Flexibility in design -Cost-effective -Biocompatibility |

-Durability issues with PDMS -Limited resolution |

| CNC milling | -High precision -Material versatility |

-Higher initial setup costs -Complexity in fabricating intricate designs |

| 3D printing | -Design flexibility -Customization |

-Lower resolution -Limited printable materials |

| Laser ablation | -High precision -Rapid fabrication |

-Undesirable thermal effects -High equipment cost |

| Hot embossing | -High throughput -Material compatibility |

-Time-consuming setup -Resolution dependent on master mold quality |

| Paper-based microfluidics | -Extremely low-cost -Portability |

-Limited to simpler assays -Less durable |

Table 2: Properties of various microfluidic device materials [90]

| Property | Silicon/Glass | Elastomer | Thermoset | Thermoplastics |

| Young's Modulus | 130-180/50-90 | ~0.0005 | 2.0-2.7 | 1.4-4.1 |

| Microfabrication | Photolithography | Casting | Casting polymerization | Thermo-modling |

| Smallest Channel dimension | <100 nm | <1 µm | <100 nm | ~100 nm |

| Multilayer Channels | Hard | Easy | Easy | Easy |

| Thermos ability | Very High | Medium | High | Medium |

| Solvent Capability | Very High | Low | High | Moderate |

| Oxygen Permeability | <0.01 | ~500 | 0.03-1 | 0.05-5 |

| Optical Transparency | No/High | High | High | Medium to High |

Encapsulation efficiency

Microfluidics technology improves drug encapsulation efficiency into carriers. Compared to traditional methods, these microscale channels allow for efficient mixing and reaction conditions to produce higher capture efficiencies in the encapsulated structures to ensure a great deal of the drug reaches its target site [43-45]. The chips allow for well-controlled fluid dynamics in the microscale, producing high encapsulation efficiency into uniform and monodispersed particles. Varying microchannel geometries and multiphase fluid flow rates permit microfluidic devices to fabricate particles of the same size and shape, which is crucial for drug-delivery efficacy. The encapsulation efficiencies gained through microfluidic procedures frequently outperform those through traditional bulk processes in that the confined settings reduce drug losses and degradation [46]. This is particularly advantageous when developing nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems since keeping therapeutic agents stable and available for absorption is of high importance. Along with this, microfluidic chips open room for the incorporation of diverse materials such as polymers, lipids, and inorganic substances, thus creating multifunctional nanoparticles to effect targeted drug delivery and controlled release [47]. The deliberate tuning of the physicochemical properties of such particles adds to the therapeutic potency and minimizes adverse side effects. In addition to that, microfluidic platforms promote high-throughput screening and quick prototyping in accelerating the development of new drug formulations and delivery strategies [46]. Yet, despite the many advantages, scalability and integration with current manufacturing systems remain challenges. New family-based parallelized microfluidic systems and the use of artificial intelligence for optimized particle synthesis are being researched to deal with these problems. Overall, microfluidic chips present improved techniques of drug encapsulation efficiency in drug delivery systems and serve as a platform to explore modern-day therapies with maximized effects and diminished side effects, indeed, an amply promising perspective [48].

Microfluidic chips have transformed High-Throughput Screening (HTS) in drug discovery by allowing rapid screening of thousands of compounds while dramatically increasing precision. Microfluidic chips process very small fluid volumes with precise control of experimental conditions, increased assay sensitivity and decreased reagent requirements. Compared to the traditional approach (96-or 384-well plates), which screens thousands of compounds per day, microfluidic HTS platforms can screen tens of thousands of compounds daily, mostly due to smaller assay volumes and automated systems. This 16-fold increase in throughput is made possible by the reduced assay volumes, which affords the luxury of time for chemical and protein libraries and reduces the overall demand on costly reagents. Smaller assay volumes allow for greater sensitivity when studying the interactions between compounds and test systems via the confinement of interactions on a small scale, ultimately producing data with better accuracy and repeatability. Ultimately, real-world applications of microfluidic chips, such as perfusion flow platforms and droplet-based systems, have shown they can effectively facilitate drug discovery by dismantling the bottlenecks in pharmaceutical research. These platforms allow for detailed information on the specificity of compounds and pharmacological activity throughout primary screening [16].

Continuous production

Microfluidic chips do great revolutions in continuous production by enabling real-time control of fluid dynamics at the micro-scale. This enables continuous, efficient manufacture of particles and compounds of exact size and shape, with applications in pharma, diagnostics, and materials science. With microfluidic devices, continuous-flow techniques allow the continuous production of high-quality material at a steady rate to ensure uniform quality and maximum output. That minimizes the waste generated and the long post-processing typically required, thus being more cost-and eco-friendly compared to the traditional batch counterparts [49, 50]. Furthermore, microfluidic systems with sensing and online automated controls provide real-time monitoring and tuning of the parameters affecting production, leading to improved reliability and efficiency. Another solution for the scalability problem is parallelization in terms of microfluidic channels for ramping up production, which is suitable for industrial applications. However, it also has several challenges, such as integrating with existing manufacturing processes and retrofitting a microfluidic system to be robust on a larger scale. The research conducted to date is directed at overcoming these challenges by building on advances in micro-manufacturing and enhancing it by imgding artificial intelligence technology for optimized process control. To highlight, microfluidic chips are a step toward, if not necessarily the solution, to continuous production with high precision, efficiency, and scalability in industrial applications [51, 52].

Integration with diagnostic tools

Microfluidic chips have rearranged continuous production processes by enhancing fluid dynamics control at the microscale level, thereby manufacturing particles and compounds of similar size and shape. These characteristics are important in pharmaceuticals, diagnostics, and material science. By using microfluidics in continuous-flow technologies, production rates are maintained at continuous levels, ensuring uniform quality at high output. This lessens wastage and the need for extensive post-processing, thus cheaper and more environmentally friendly in comparison to traditional batch methods [49, 50]. Also, integration of sensors and automation into microfluidic systems allows real-time monitoring and correction of production parameters, increasing the reliability and efficiency of the process. Besides, addressing scalability issues for onward industrial applications through upwards parallelization of microfluidic channels has provided the promise of successful scaling up of production processes. Unfortunately, despite their advantages, there are issues regarding interfacing current implementation methods into manufacturing processes and building reliable, large-scale microfluidic systems. Ongoing research seeks to overcome these barriers through one or multiple ways by modernizing microfabrication methods and coupling artificial intelligence for optimized process control. Microfluidic chips have a lot of promise in terms of continuous production, offering precision, efficiency, and scalability for many kinds of industrial applications [51, 52].

The implementation of qualification tools into microfluidic chips has considerably accelerated the phase of medical diagnostics, mainly toward rapid, accurate, and cost-effective fulfillment. Also known as lab-on-chip devices, microfluidic chips allow for miniaturization and automation in the optimization of lab processes, performing different task operations in one chip [53]. By the incorporation of biosensors, optical detectors, and electrochemical sensors, these chips can highly sensitively and specifically further detect and quantify certain biomarkers. Such integration makes it suitable for real-time monitoring and analysis of biological samples, which reduces diagnosis time while enabling point-of-care testing. Controlling the flow of fluids in precise as well as clear microfluidic channels is such that it allows perfect mixing, good separation, and good reactions of the analytes so as to enhance reliability in the diagnostic results [53, 54]. In addition, microfluidic systems use small sample volumes, thereby creating a different kind of diagnosis that is less invasive and friendly to the patients. The ability to fit different modalities onto a single chip also creates the potential for multiplexed assays, enabling the detection of many biomarkers in a single run. With several challenges, including scalability and integration with existing health infrastructure, researchers are keen to find a way around these bottlenecks. In summary, the integration of diagnostic tools into microfluidic chips presents a game-changing avenue in medical diagnostics with promises of making them more efficient, accurate, and available [55, 56].

Microfluidic pumps and valves

Microfluidic pumps and valves are core building blocks that take control of fluids at the microscale. Therefore, the open and directed flow of the fluids is key to chemical synthesis, biological assays, and medical diagnosis. A microfluidic pump that has peristaltic, diaphragm and electroosmotic principles can produce a continuous or pulsatile flow, ensuring constant and reliable delivery of fluid. Valves allow precise on-off control and flow modulation through solenoid, pneumatic, and elastomeric types, thereby increasing versatility and function in microfluidic devices [57, 58]. By integrating these pumps and valves with microfluidic systems, it is possible to automate complex processes needing little manual intervention, increasing throughput. The miniaturized nature of these components allows for their imgding into portable and point-of-care devices, bringing advanced medical diagnosis within reach. Although there has been logic to challenge the integration of microfluidic knowledge with existing technologies, research is still fostered to support improvements concerning performance, reliability, and cost as far as microfluidic pumps and valves are concerned. Microfluidic pumps, valves, and chips, in summary, are core to any other research and development that works within the purview of microfluidics [57, 59, 60].

In a nutshell, microfluidic chips represent a very flexible and efficient platform from which the next generation of drug delivery systems can be constructed, allowing for extremely accurate tuning of the drug form, encapsulation, or release.

Case studies on microfluidic chip applications in pharmaceutical R and D

Jiksak bioengineering: ALS drug development

Microfluidic chips have shown great promise in drug development as evidenced by numerous real-world examples. One of the more notable applications has been to advance pharmaceutical development in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) by Jiksak Bioengineering (Jiksak Bioengineering). Jiksak Bioengineering is using microfluidic chips to create neurons by mimicking the body's environment and growing nerve tissue in three-dimensional space. In providing an organ-on-a-chip model it provides a much more useful approach to an accurate testing model for potential treatments and has significantly advanced drug development for ALS [61]. Another application of microfluidic chips is through droplet-based microfluidics that have been advanced for drug screening and drug formulation applications. This system can provide precise control and solid manipulation of small droplets, allowing for high-throughput screening and more efficient testing of multiple drug candidates.

Microfluidic chips can also be used to simulate human organ environments to study drug metabolism and the pharmacokinetics effect. By simulating the organ environment, animal testing can become less relied upon and provide human-centric results (more pertinent and relevant for research and development efforts), which can create more accurate outcomes for drug development [1]. Overall, these case study examples demonstrate the ever-increasing ways that the microfluidic chip can change pharmaceutical research and development through efficiencies in drug discovery.

Personalized medicine

Microfluidics chip promotes personalized medicine, as it features accurate and efficient solutions for individualized treatment for a patient. The chips allow complex processes in laboratories to miniaturize and automated, performing fast analysis on biological samples from patients, which are patient-oriented. It is also through the use of biosensors and online monitoring that microfluidic devices can carry out the detection and measurement of biomarker activities with high sensitivity, providing the required information for a personalized treatment plan [61]. This offers the potential to use customized drug formulations and delivery systems based on patients' genetic and biochemical profiles. There are, however, some other microfluidic chips that enhance high-throughput screening, thus allowing testing of multiple drug candidates and combinations within a fraction of the time to find the right treatment for each patient [62]. On the plus side, it also assists the production of point-of-care diagnostic devices, taking personalized medicine closer to everyone while minimizing diagnosis time and adjustments to the treatment. Challenges such as scalability and integration into existing health systems might be tackled with ongoing research that aims to develop microfabrication technology while simultaneously integrating AI for optimized process control. Simply put, microfluidic chips are transforming personalized medicine with high precision, efficiency, and adaptability, such as improving patient outcomes and healthcare advancement [55, 63].

AI-driven microfluidic platforms further enhance personalized medicine by tailoring patient-specific drug treatments. These platforms integrate microfluidic technology with artificial intelligence to analyze complex data sets and predict optimal therapeutic strategies. For instance, AI can process high-throughput data from microfluidic assays to determine the most effective drug combinations and dosages for individual patients. In Chronic Myeloid Leukaemia (CML) treatment, AI-driven microfluidic systems have been used to select the most suitable BCR: ABL1 Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors (TKIs) based on patient-specific biological and genetic factors. This integration allows for real-time monitoring and adjustment of treatment plans, improving therapeutic outcomes and minimizing adverse effects.

Personalized customization of medical treatment for the unique characteristics of each patient is gaining prominence and prominence in recent times. Microfluidic chips, also known as lab-on-a-chip devices, represent perhaps the most important technological development in the personalization of medicine today. Designed to allow precise control and manipulation of small volumes of fluid, these chips will be used to engineer personalized treatment strategies mirroring an individual's unique genetic and biochemical profile [21, 61]. This is how microfluidic chips are affecting changes in personalized medicine.

Table 3: Comparison of microfluidic approaches vs. conventional methodologies

| Aspect | Microfluidic approaches | Conventional methodologies |

| Precision | High precision in isolating and analyzing single cells | Bulk analysis of cell populations, less precise |

| Sensitivity | Enhanced sensitivity due to miniaturization and integration of biosensors | Lower sensitivity, often requiring larger sample volumes |

| Throughput | High-throughput screening capabilities, processing thousands of samples simultaneously | Limited throughput, slower processing times |

| Cost | Reduced reagent consumption and operational costs | Higher reagent consumption, more expensive |

| Personalization | Tailored treatments based on individual genetic profiles and cellular responses | Generalized treatments, less personalized |

| Regulatory approval | Requires extensive validation and standardization for regulatory approval | Established methodologies with existing regulatory frameworks |

Genetic analysis and mutation detection

Microfluidic chips have revolutionized genetic analysis and mutation discovery via accurate, rapid, and efficient processing of biological samples in very high numbers. With these chips, complex procedures that are normally encountered in laboratories are intricate and automated, thus providing the ability to analyze more than one or many genetic markers at once. High-sensitivity and high-specificity genetic mutation detection and quantification with microfluidic devices can be achieved when made by integrating biosensing with real-time monitoring. This function is of great importance in cancer diagnosis because early detection of oncogenic mutations leads to the best-informed treatment and consequently to patient welfare. However, the relevant mixing, separation, and amplification of nucleic acids all occur at a microscale through the control of fluid dynamics, which serves to optimize the accuracy and reliability of genetic analyses [64, 65]. Furthermore, microfluidic chips allow for the realization of point-of-care diagnostic tools, which enhance the accessibility of genetic testing and reduce the turnaround time for results. Although scalability and integration into the current healthcare systems are significant issues, investigations that intend to tackle such complications still receive ongoing support via the enhancement of microfabrication technologies and the integration of artificial intelligence, enabling optimized process management shortly. Very briefly put, microfluidic chips offer an emerging methodology to genetic testing and mutation detection, combining high precision, efficiency, and versatility to enrich diagnosis capabilities while enhancing personalized medicine [61, 66, 67].

Drug Testing with Organoids: The area of organoid-based drug testing saw a major leap through the development of microfluidic-enabled chips, allowing precise control over the microenvironment and rapid, high-throughput drug screening. Such chips help to perform complex lab processes in miniature and more automated ways, leading to efficient organoid culture and manipulation, given that organoids are three-dimensional cell structures that replicate the architecture and function of human organs. Microfluidic devices, with their integrated biosensors and real-time monitoring, may now assess the drug candidate-induced effects on organoids with high specificity and sensitivity. Such assessments are extremely valuable when determining the oncological efficacy and toxicity of the treatment by visualizing the cellular responses in a controllable and reproducible manner. In addition, drug-testing capacity in microfluidics is augmented by the formation and maintenance of concentration gradients in the channels that mimic in vivo environments [61, 68, 69]. Moreover, microfluidic chips can be instrumental to personalized medicine by allowing the testing of patient-derived organoids mapping individual decisions to treatment. Meanwhile, there are specific challenges, just like those of scalabilities to the modes and emulations in existing drug developments; further research would stand against such barriers by developing microfabrication techniques with artificial intelligence for inside purposes to initiate further control [69, 70]. To summarize, microfluidic chips provide a transformative approach to organoid-based drug testing, allowing for greatness in precision, efficiency, and versatility-imaging factually new aspects of drug discovery and development.

Single-cell analysis

Microfluidic chips have allowed for single-cell analysis precise and rapid high-throughput processing of single cells. In general, this type of small lab work allows the automation of such miniaturization of isolation, manipulation, and analysis of single cells, which is resolved. By integrating the powerful response sensitivity and specificity in cellular analysis and quantification of response with microfluidic devices, along with biosensors and real-time monitoring, the method could achieve ultra-sensitive responses to various types of cells. This field presents a vast number of questions of relevance in a broad scope regarding cellular heterogeneity related to cancer, immunology, and developmental biology [16]. With microscale fluid dynamics, efficient mixing, separation, and amplification of cellular components can be achieved, which further enhances the accuracy and reliability of single-cell analyses. Also, microfluidic chips enable high-throughput screening, which allows thousands of individual cells to be analysed simultaneously, in turn expediting the search for new biomarkers and therapeutic targets [71, 72]. Some major challenges include scalability and integration into existing lab workflows, but research is underway to overcome these hurdles, focusing on the improvement of microfabrication technologies and integrating artificial intelligence for optimized process control. Microfluidic chips could truly revolutionize the field of single-cell analysis with high precision, efficiency, flexibility, and insights into cellular biology and biomedical research [33, 72, 73].

Point-of-care diagnostics

Point-of-care diagnostics (POCD) with microfluidic devices have taken a massive leap into medical diagnostics and have paved the way for fast, accurate, and cheap testing at the location of the patient. They are also termed lab-on-a-chip devices, as they put together the multitude of laboratory functions onto one chip, by means of microchannels that deal with a small volume of fluid. This innovation allows detection of a wide variety of biomarkers and pathogens with almost total accuracy and sensitivity for a much shorter timeframe than that required by conventional lab methodology. Recent improvements in the incorporation of biosensors into Microfluidic (MF) chips have greatly improved real-time diagnostics. MF with biosensors incorporate the sensitivity and specificity of biosensors with fluidic regulation and miniaturization that MF provides to allow rapid, accurate, and cost-effective analysis of clinical samples at the point of care. Significant advances which may occur in the future will include highly sensitive electrochemical and optical (bio)sensors that can detect low levels of biomarker(s), novel materials aimed at improved stability and biocompatibility and inexpensive, speedily automated processing of samples. The process miniaturization and automation are enhancing the diagnostic procedures' efficiency, thereby making them possible to function credibly in resource-limited environments. Applications of microfluidic POCD include glucose monitoring, infectious disease diagnosis, and cancer biomarker testing. In essence, these chips could bring immediate results that make it possible to make timely clinical decisions, improving patient outcomes while at the same time lowering healthcare costs. Continuous innovations in microfluidics are widening the horizons and promising broader horizons to personalized medicine and global health [74-76].

Microfluidic chips have been successfully used in cancer diagnostics, particularly in liquid biopsy applications. These chips can isolate and analyze Circulating tumor cells (CTCs) from blood samples, providing a non-invasive method for cancer detection and monitoring. The integration of biosensors enhances the detection of specific cancer biomarkers, improving the accuracy and reliability of the diagnosis [77, 78].

One of the greatest hurdles facing the mass production of lab-on-chip diagnostics is the scalability of production. Manufacturing methods such as photolithography and soft lithography, while reliable and accurate techniques are not necessarily affordable for high volume. While 3D printing, injection modelling, etc., can potentially be more efficient, these still require additional optimization steps to achieve sufficient precision and reproducibility. Moreover, the overall costs of materials and fabrication can be substantial, decreasing the chances of lab-on-chip devices becoming affordable [79-81]. This has led individuals to seek low-cost materials while simplifying fabrication as much as possible, while maintaining device quality. Furthermore, as many lab-on-chip diagnostics can have automated components that replace the actions (auxiliary equipment) of operating these diagnostics, this would also help lower operational costs. For microfluidic-based diagnostics to obtain commercial approval, they must also undergo rigorous validation standards to ensure reliability and validity. The regulations for doing this can be lengthy and expensive, acting as a barrier against the rapid commercialization of new designs. Collaborating with regulatory boards and creating standardized processes for testing and commercialization will expedite the production of new designs [82].

Microfluidic immunoassay

Microfluidic immunoassays are an important leap in diagnostics as an attractive platform for the detection of a wide array of biomarkers that is compact and cost-effective and has great sensitivity. Lab-on-chip devices use nanoliters of microchannels to push tiny volumes, producing fast and accurate immunoassay procedures that used to be confined to a larger area in a lab. By combining microfluidics with immunoassays, it should be possible to couple specific and sensitive detection of pathogens through antigen and antibody quantification using appropriate immunoassays to effect early diagnosis. This is of much use at a point of care, allowing for a rapid and accurate test that would facilitate vital interventions for treatment. Applications of microfluidic immunoassays indeed range from the detection of infectious diseases through cancer diagnostics to chronic disease monitoring. These systems are further cumulatively integrated with fluorescent, chemiluminescent, and electrochemical detection methods. In addition to the above-mentioned, it saves costs and reduces waste because of low consumption of samples and reagents, which is an advantage in all respects, both economically and environmentally. As research advances and enhances microfluidic immunoassays, the further fitting to incorporate these systems into wearables and smart technologies merely expands, thus showcasing a boon to reorienting personalized medicine and real-time health monitoring. This combination enhances patient outcomes with timely medical interventions that, in turn, reduce the pooled expenditure for health by reducing visits to clinical practice [83, 84].

The uses of microfluidic chips are opening wide, easily supported by wearable technology, hence allowing great strides to be made in chronic disease management, fitness monitoring, and remotely monitoring patients. This area of research and development further promises to revolutionize health and wellness, allowing for more personalized healthcare that is affordable and efficient.

EGFR and lung cancer

Microfluidic chips for the detection and analysis of EGFR mutations in lung cancer signify a great leap for personalized medicine [85]. Usually, mutations in non-small cell lung cancer and its enabling mutation is Adenocarcinoma; the mutations of EGFR are associated with the initiation and progression of the disease. These microfluidic chips provide a compact and efficient platform for an accurate and fast analysis of these mutations, also referred to as lab-on-a-chip devices. Using microchannels to manipulate small volumes of fluid, they are sensitive enough to identify mutated EGFR, providing early diagnosis and treatment. This is especially useful for point-of-care applications where rapid and accurate results may impact clinical decisions. The combination of the chips to advance detection systems-such as fluorescence and electrochemical techniques-greatly enhances their diagnostic performance [86]. As the research in this field advances, the integrated possibilities of microfluidic technology with wearable devices and smart technologies are growing, which could drastically improve the way health can be monitored and treated. To sum up, the introduction of microfluidic chips for EGFR mutation analysis presents a tremendous leap in the diagnosis of lung cancer and proves to be a significant tool for communication to improve patient outcomes and global health.

DISCUSSION

Microfluidics is leading the way toward personalized medicine, producing innovative mechanisms for tailoring treatments to each patient. With their genetic analysis capability, organoid-based drug testing, single-cell analysis, high-throughput screening, point-of-care diagnostics integration with wearable devices, and advanced drug delivery systems, microfluidic technologies are transforming the collection of care. Not only do these advancements enhance the efficacy and safety of treatments, but they also open the door towards a more personalized and patient-centric approach to medicine. These chips consist basically of a network of tiny channels developed in a material substrate such as glass, silicon, or polymers that allow targeted provision and manipulation of fluids at the microscale. For their pharmaceutical capability, microfluidic chips have several types of attractive features. One of the main benefits of microfluidic chips is minimized usage of reagents and samples. Traditional pharmaceutical processes generally employ very high volumes of sometimes expensive computed reagents, but microfluidic systems take on the least activity, therefore yielding a great economy on the reagents. In addition to limiting reagent waste and thus being environmentally friendly, techniques of reduction allow these systems to effect rapid reactions and analyses [84].

Scaling up a microfluidic system is compounded by the considerations required in transitioning from prototype to full-scale production. Fabrication methods, such as photolithography and soft lithography, are well established but can be costly when full-scale production is required. Other processes, such as 3D printing and injection moulding, are being shown to address the issues related to microfluidic devices but still require optimization to enable scale, precision, and reproducibility. The use of glass for prototyping may also restrict transition to full-scale production, as polymeric materials can be used for transition to full production more easily in many instances. Continuing to deliver consistent performance and quality in large batch sizes of microfluidic devices is a significant barrier to scaling efforts [86, 87]. Establishing analytic, clinical, and scientific validity will be necessary for regulatory compliance of microfluidic systems and is a complex and time-intensive process. The absence of specific guidance and standardized considerations for microfluidics adds to this complexity [100]. Regulatory processes generally outline expectations of manufacturing to validate the process to predict human outcomes reliably and safely while also validating efficacy [88]. This process usually requires testing and comparison to established methods, and is expensive and slow in getting new technology into use. AI and automation will change the way microfluidic technology is applied. AI-driven microfluidic platform will have the capabilities to process complex data sets, enabling predictions on appropriate therapeutic approaches that will improve precision and efficiency in diagnostics and treatment. For example, AI can analyze high-throughput data results from microfluidic assays to determine the most effective drug combinations and doses that are best for individual patients. Automation of microfluidic systems allows real-time monitoring and modulation of experimental parameters, thereby improving reproducibility and reducing human error. More specifically, these advancements are expected to allow quicker drug discovery, personalized medicine and point-of-care diagnostics [89].

Another considerable advantage is the precision and control offered by microfluidic chips. The microscale environment permits precise manipulation of fluids, leading to meticulous control of reaction conditions. In particular, it is very useful in nanoparticle formulation and drug delivery systems, wherein the particle sizes and their distribution could either assure or impair the efficacy of treatment and safety level. The microfluidic chips can generate extremely uniform particles, a near impossibility with any conventional methods, ensuring consistency in drug delivery and experimental reproducibility [85]. Besides, microfluidic chips allow the integration of multiple laboratory functions into one single device. This integration, named "lab-on-a-chip", enables different procedures like mixing, separation, and detection to take place simultaneously. Thereby, processes save time and minimize the risk of contamination and human error due to a reduced requirement for manual intervention. The small form factor rotationally opens take-away point-of-care tests and on-site drug analysis when working in isolated areas or limited-resource settings.

Future lines of research should involve: Firstly, improving fabrication methods by exploring and optimizing scalable methods, such as 3D printing and injection modelling, which will improve accuracy and reproducibility, and investigating the use of inexpensive, biocompatible materials that are appropriate for mass production. Secondly, establishing standardization and regulation with collaborations with governing bodies for unique guidelines and standardized evaluation for microfluidics devices and by providing strong validation methods to show reliability and predictive capability for microfluidic-based assays.

Thirdly, there is a need for increased integration of artificial intelligence and automation but working to enhance algorithms for AI to allow for data analyses and decision-making capability in real-time, especially in closed-loop microfluidic systems, and developing automated systems for sample processing, data collection, and data analysis to improve efficiency and reduce human errors [89]. Fourthly, expanded applications should include exploring new developments of microfluidic technology applications, including in environmental monitoring, synthetic biology, and drug delivery systems, as well as developing modular microfluidics systems that can be easily modified and deployed for unique applications. Finally, collaboration and interdisciplinary research work will be essential for continued growth in looking for ways to facilitate collaboration between engineers, biologists, chemists, and data scientists to provide an environment conducive to innovation in the microfluidics technologies and interdisciplinary research to help address some of the many challenges in developing and applying microfluidics systems.

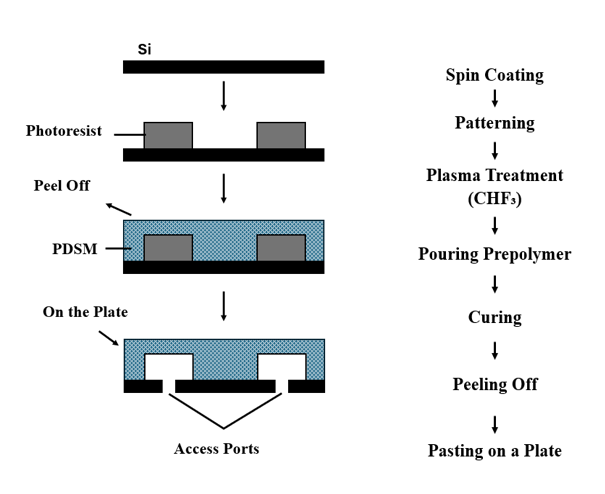

Fig. 2: Fabrication process of PDMS microchip [90]

Table 4: Comprehensive list of patents on microfluidic chip technology

| Patent number | Patent holder | Date | Title | Reference |

| US20080003142A1 | Darren l et al. | 2008-01-03 | Microfluidic devices | [91] |

| US10675619B2 | Gottfried R et al. | 2020-06-09 | Method for manufacturing a microfluidic device | [92] |

| US11187224B2 | Zheng X et al. | 2021-11-30 | Microfluidic chip | [93] |

| US11458474B2 | Joshua S et al. | 2022-10-04 | Microfluidic chips with one or more vias | [94] |

| US11759782B2 | Tiina M et al. | 2023-09-19 | Microfluidic chip and a method for the manufacture of a microfluidic chip | [95] |

| US20210113974A1 | Euan R et al. | 2024-03-26 | Continuous flow microfluidic system | [96] |

CONCLUSION

The exceptional advantage of microfluidic chips over others, from the point of view of the pharmaceutical industry, includes but is not limited to low reagent consumption, high accuracy, and the capability to incorporate several laboratory functions into one device, which would in turn facilitate drug discovery and development processes, enhance consistency in drug formulation, and also provide possibilities for point-of-care testing. Nevertheless, they pose major hurdles mostly due to complications in their design and fabrication, trouble of scale-up processes, and their ever-difficult integration into existing workflows. However, the viability of microfluidics in ushering pharmaceutical R and D forward gives a certain promise. Therefore, further microfluidic design and fabrication improvements-with special emphasis on addressing scale-up and practical integration problems-will make a strong difference in further fulfilling the promises of this technology in the pharmaceutical setting.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors are thankful to the management and leadership of Manipal College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, India, for providing all the necessary facilities.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Anakana Roy: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Writing–original draft. Ankana Roy, Gundawar Ravi: Investigation, Methodology, Writing–review and editing. Gundawar Ravi: Conceptualization, Data curation, Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing–review and editing. Muddukrishna BS: Formal analysis, Investigation, Supervision, Visualization. Riyaz Ali M. Osmani: Investigation, Methodology, Writing–review and editing. SG Vasantharaju: Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Review and editing.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no conflict of interest

REFERENCES

Pattanayak P, Singh SK, Gulati M, Vishwas S, Kapoor B, Chellappan DK. Microfluidic chips: recent advances critical strategies in design applications and future perspectives. Microfluid Nanofluidics. 2021 Dec;25(12):99. doi: 10.1007/s10404-021-02502-2, PMID 34720789.

Li X, Fan X, Li Z, Shi L, Liu J, Luo H. Application of microfluidics in drug development from traditional medicine. Biosensors. 2022 Oct 13;12(10):870. doi: 10.3390/bios12100870, PMID 36291008.

Whitesides GM. The origins and the future of microfluidics. Nature. 2006 Jul 27;442(7101):368-73. doi: 10.1038/nature05058, PMID 16871203.

Hajam MI, Khan MM. Microfluidics: a concise review of the history principles design applications and future outlook. Biomater Sci. 2024;12(2):218-51. doi: 10.1039/d3bm01463k, PMID 38108438.

Guo S, Imato T. Application of compact disc type microfluidic platform to biochemical and biomedical analysis review. FIA. 2013;30(1):29. doi: 10.24688/jfia.30.1_29.

Anwar N, Jiang G, Wen Y, Ahmed M, Zhong H, Ao S. Evaluating the potential of two-dimensional materials for innovations in multifunctional electrochromic biochemical sensors: a review. Moore More. 2024 Nov 25;1(1):12. doi: 10.1007/s44275-024-00013-0.

Whitesides GM. The origins and the future of microfluidics. Nature. 2006 Jul 27;442(7101):368-73. doi: 10.1038/nature05058, PMID 16871203.

Shendure J, Balasubramanian S, Church GM, Gilbert W, Rogers J, Schloss JA. DNA sequencing at 40: past present and future. Nature. 2017 Oct 19;550(7676):345-53. doi: 10.1038/nature24286, PMID 29019985.

Zubov VV, Chemeris DA, Vasilov RG, Kurochkin VE, Alekseev YI. Brief history of high throughput nucleic acid sequencing methods. Biomics. 2021;13(1):27-46. doi: 10.31301/2221-6197.bmcs.2021-4.

Becker H, Gartner C. Polymer microfabrication technologies for microfluidic systems. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2008 Jan;390(1):89-111. doi: 10.1007/s00216-007-1692-2, PMID 17989961.

Roy E, Galas JC, Veres T. Thermoplastics elastomers for microfluidics valving and mixing toward high throughput fabrication of multilayers devices. Rt-PA of the 14th international conference on miniaturized systems for Chemistry and life sciences Groningen; 2010. p. 1235-7.

Stavins RA, King WP. Three-dimensional elastomer bellows microfluidic pump. Microfluid Nanofluid. 2023 Feb;27(2):13. doi: 10.1007/s10404-023-02624-9.

Raj MK, Chakraborty S. PDMS microfluidics: a mini-review. J Appl Polym Sci. 2020 Jul 15;137(27):48958. doi: 10.1002/app.48958.

Kulkarni MB, Goel S. Microfluidic devices for synthesizing nanomaterials a review. Nano Express. 2020 Nov 30;1(3):32004. doi: 10.1088/2632-959X/abcca6.

Escobedo C, Brolo AG. Synergizing microfluidics and plasmonics: advances applications and future directions. Lab Chip. 2025;25(5):1256-81. doi: 10.1039/d4lc00572d, PMID 39774486.

Bhusal A, Yogeshwaran S, Goodarzi Hosseinabadi H, Cecen B, Miri AK. Microfluidics for high throughput screening of biological agents and therapeutics. Biomed Mater Devices. 2025;3(1):93-107. doi: 10.1007/s44174-024-00169-1.

Yoon S, Kilicarslan You D, Jeong U, Lee M, Kim E, Jeon TJ. Microfluidics in high throughput drug screening: organ on-a-chip and C. elegans based innovations. Biosensors. 2024 Jan 21;14(1):55. doi: 10.3390/bios14010055, PMID 38275308.

Fu J, Qiu H, Tan CS. Microfluidic liver on-a-chip for preclinical drug discovery. Pharmaceutics. 2023 Apr 21;15(4):1300. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics15041300, PMID 37111785.

Kimura H, Ikeda T, Nakayama H, Sakai Y, Fujii T. An on-chip-small intestine liver model for pharmacokinetic studies. J Lab Autom. 2015 Jun;20(3):265-73. doi: 10.1177/2211068214557812, PMID 25385717.

Nandy S, Thakur S, Saha S, Chhatrala KA, Agarwal Bansal A. Microfluidic organ-on-a-chip models of human organs in drug discovery. JETIR. 2024;11(3):h221-7.

Ingber DE. Human organs-on-chips for disease modelling drug development and personalized medicine. Nat Rev Genet. 2022 Aug;23(8):467-91. doi: 10.1038/s41576-022-00466-9, PMID 35338360.

Mehraji S, De Voe DL. Microfluidic synthesis of lipid-based nanoparticles for drug delivery: recent advances and opportunities. Lab Chip. 2024;24(5):1154-74. doi: 10.1039/d3lc00821e, PMID 38165786.

Piunti C, Cimetta E. Microfluidic approaches for producing lipid based nanoparticles for drug delivery applications. Biophys Rev. 2023 Sep 1;4(3):31304. doi: 10.1063/5.0150345, PMID 38505779.

Jung D, Jang S, Park D, Bae NH, Han CS, Ryu S. Automated microfluidic systems facilitating the scalable and reliable production of lipid nanoparticles for gene delivery. BioChip J. 2025;19(1):79-90. doi: 10.1007/s13206-024-00182-y.

Celik C, Akcay G, Ildız N, Ocsoy I. Microfluidic chips as point of care testing for develop diagnostic microdevices. In: Mandal AK, Ghorai S, Husen A, editors. Functionalized smart nanomaterials for point-of-care testing. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore; 2024. p. 115-28. doi: 10.1007/978-981-99-5787-3_6.

Arshavsky Graham S, Segal E. Lab-on-a-chip devices for point of care medical diagnostics. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol. 2022;179:247-65. doi: 10.1007/10_2020_127, PMID 32435872.

Yahng SA, Kim HJ, Lee SB, Yoo SH, Yoon JH, Lee JH. Development of a personalized microfluidic platform for improving treatment efficiency in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2024 Nov 5;144 Suppl 1:3604. doi: 10.1182/blood-2024-211827.

Jeon H, Park Y, Um E, Kim H, Jung CY, Kim DW. Novel microfluidic and AI-based approach for personalized drug selection in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) patients. Blood. 2024 Nov 5;144 Suppl 1:7482. doi: 10.1182/blood-2024-199886.

Zhuang J, Xia L, Zou Z, Yin J, Lin N, Mu Y. Recent advances in integrated microfluidics for liquid biopsies and future directions. Biosens Bioelectron. 2022 Dec 1;217:114715. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2022.114715, PMID 36174359.

Escobedo C, Brolo AG. Synergizing microfluidics and plasmonics: advances applications and future directions. Lab Chip. 2025;25(5):1256-81. doi: 10.1039/d4lc00572d, PMID 39774486.

Xie Y, Xu X, Wang J, Lin J, Ren Y, Wu A. Latest advances and perspectives of liquid biopsy for cancer diagnostics driven by microfluidic on-chip assays. Lab Chip. 2023;23(13):2922-41. doi: 10.1039/d2lc00837h, PMID 37291937.

Nakhod V, Krivenko A, Butkova T, Malsagova K, Kaysheva A. Advances in molecular and genetic technologies and the problems related to their application in personalized medicine. J Pers Med. 2024 May 23;14(6):555. doi: 10.3390/jpm14060555, PMID 38929775.

Liu X, Sun A, Brodsky J, Gablech I, Lednicky T, Voparilova P. Microfluidics chips fabrication techniques comparison. Sci Rep. 2024 Nov 20;14(1):28793. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-80332-2, PMID 39567624.

Ezzat HS, Faris RA, Taha M. Lab on-a-chip-based an integrated microfluidic device lo-cost, rapid and sensitive analysis of augmentin. AIP Conf Proc. 2024 Feb 16;3051(1)100025. doi: 10.1063/5.0191751.

Fabozzi A, Della Sala F, Di Gennaro M, Barretta M, Longobardo G, Solimando N. Design of functional nanoparticles by microfluidic platforms as advanced drug delivery systems for cancer therapy. Lab Chip. 2023;23(5):1389-409. doi: 10.1039/d2lc00933a, PMID 36647782.

Ferreira B, Faria P, Viegas J, Sarmento B, Martins C. Microfluidic technologies for precise drug delivery. In: Lamprou DA, Weaver E, editors. Microfluidics in pharmaceutical sciences: formulation drug delivery screening and diagnostics. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland; 2024 Jun 22. p. 313-33. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-60717-2_13.

Lin J, Hou Y, Zhang Q, Lin JM. Droplets in open microfluidics: generation manipulation and application in cell analysis. Lab Chip. 2025;25(5):787-805. doi: 10.1039/d4lc00646a, PMID 39774470.

Vladisavljevic GT, Kobayashi I, Nakajima M. Production of uniform droplets using membrane microchannel and microfluidic emulsification devices. Microfluid Nanofluid. 2012 Jul;13(1):151-78. doi: 10.1007/s10404-012-0948-0.

Jahn A, Reiner JE, Vreeland WN, DeVoe DL, Locascio LE, Gaitan M. Preparation of nanoparticles by continuous flow microfluidics. J Nanopart Res. 2008 Aug;10(6):925-34. doi: 10.1007/s11051-007-9340-5.

Iannone M, Caccavo D, Barba AA, Lamberti G. A low-cost push pull syringe pump for continuous flow applications. Hardware X. 2022 Apr 1;11(1):e00295. doi: 10.1016/j.ohx.2022.e00295, PMID 35509919.

Yao F, Zhu P, Chen J, Li S, Sun B, Li Y. Synthesis of nanoparticles via microfluidic devices and integrated applications. Mikrochim Acta. 2023 Jul;190(7):256. doi: 10.1007/s00604-023-05838-4, PMID 37301779.

Knauer A, Koehler JM. Screening of nanoparticle properties in microfluidic syntheses. Nanotechnol Rev. 2014 Feb 1;3(1):5-26. doi: 10.1515/ntrev-2013-0018.

Arruebo M, Sebastian V. Batch and microfluidic reactors in the synthesis of enteric drug carriers. In: Nanotechnology for oral drug delivery. Elsevier; 2020 Jan 1. p. 317-57. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-818038-9.00008-9.

Liu Y, Yang G, Hui Y, Ranaweera S, Zhao CX. Microfluidic nanoparticles for drug delivery. Small. 2022 Sep;18(36):e2106580. doi: 10.1002/smll.202106580, PMID 35396770.

Operti MC, Bernhardt A, Grimm S, Engel A, Figdor CG, Tagit O. PLGA based nanomedicines manufacturing: technologies overview and challenges in industrial scale-up. Int J Pharm. 2021 Aug 10;605:120807. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.120807, PMID 34144133.

Rawas Qalaji M, Cagliani R, Al Hashimi N, Al Dabbagh R, Al Dabbagh A, Hussain Z. Microfluidics in drug delivery: review of methods and applications. Pharm Dev Technol. 2023 Jan 2;28(1):61-77. doi: 10.1080/10837450.2022.2162543, PMID 36592376.

Sun Y, Jin F, Gao D. Microfluidic chip-based nano-carrier-based drug delivery systems and their efficacy assessment using tumor organ chips. BME Horiz. 2024 Dec 20;2(3):136. doi: 10.70401/bmeh.2024.136.

Tsai HF, Podder S, Chen PY. Microsystem advances through integration with artificial intelligence. Micromachines. 2023 Apr 8;14(4):826. doi: 10.3390/mi14040826, PMID 37421059.

Ahmed F, Yoshida Y, Wang J, Sakai K, Kiwa T. Design and validation of microfluidic parameters of a microfluidic chip using fluid dynamics. AIP Adv. 2021 Jul 1;11(7):75224. doi: 10.1063/5.0056597.

Deswal H, Yadav SP, Singh SG, Agrawal A. Flow sensors for on-chip microfluidics: promise and challenges. Exp Fluids. 2024 Dec;65(12):1-25. doi: 10.1007/s00348-024-03918-6.

Su F, Chakrabarty K, Fair RB. Microfluidics based biochips: technology issues implementation platforms and design automation challenges. IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems. 2006 Feb 21;25(2):211-23. doi: 10.1109/TCAD.2005.855956.

Aryal P, Henry CS. Advancements and challenges in microfluidic paper-based analytical devices: design manufacturing sustainability and field applications. Front Lab Chip Technol. 2024 Dec 20;3:1467423. doi: 10.3389/frlct.2024.1467423.

Yang SM, LV S, Zhang W, Cui Y. Microfluidic point-of-care (POC) devices in early diagnosis: a review of opportunities and challenges. Sensors (Basel). 2022 Feb 18;22(4):1620. doi: 10.3390/s22041620, PMID 35214519.

Baroud CN, Gallaire F, Dangla R. Dynamics of microfluidic droplets. Lab Chip. 2010;10(16):2032-45. doi: 10.1039/c001191f, PMID 20559601.

Akerele JI, Uzoka A, Ojukwu PU, Olamijuwon OJ. Improving healthcare application scalability through microservices architecture in the cloud. Int J Sci Res Updates. 2024 Nov;8(2):100-9. doi: 10.53430/ijsru.2024.8.2.0064.

Behera PP, Kumar N, Kumari M, Kumar S, Mondal PK, Arun RK. Integrated microfluidic devices for point-of-care detection of bio-analytes and disease. Sens Diagn. 2023;2(6):1437-59. doi: 10.1039/D3SD00170A.

Suzuki H, Yoneyama R. Integrated microfluidic system with electrochemically actuated on-chip pumps and valves. Sens Actuators B. 2003 Nov 15;96(1-2):38-45. doi: 10.1016/S0925-4005(03)00482-9.

Iakovlev AP, Erofeev AS, Gorelkin PV. Novel pumping methods for microfluidic devices: a comprehensive review. Biosensors. 2022 Nov 1;12(11):956. doi: 10.3390/bios12110956, PMID 36354465.

Melin J, Quake SR. Microfluidic large scale integration: the evolution of design rules for biological automation. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2007 Jun 9;36(1):213-31. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.36.040306.132646, PMID 17269901.

Prithvi J, Sreeja BS, Radha S, Joshitha C, Gowthami A. Critical review and exploration on micro-pumps for microfluidic delivery. In: Guha K, Dutta G, Biswas A, Srinivasa Rao K, editors. MEMS and microfluidics in healthcare: devices and applications perspectives. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore; 2023 Mar 14. p. 65-100. doi: 10.1007/978-981-19-8714-4_5.

Zhang K, Xi J, Zhao H, Wang Y, Xue J, Liang N. A dual functional microfluidic chip for guiding personalized lung cancer medicine: combining EGFR mutation detection and organoid based drug response test. Lab Chip. 2024;24(6):1762-74. doi: 10.1039/d3lc00974b, PMID 38352981.

Cruz A, Fernandes E, Rodrigues RO, Catarino SO, Pinho D. Editorial: disease-on-a-chip: from point-of-care to personalized medicine. Front Pharmacol. 2023 Dec 11;14:1344379. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1344379, PMID 38146462.

Xing G, Ai J, Wang N, Pu Q. Recent progress of smartphone assisted microfluidic sensors for point of care testing. TrAC Trends Anal Chem. 2022 Dec 1;157:116792. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2022.116792.

Patel R, Tsan A, Tam R, Desai R, Spoerke J, Schoenbrunner N. Mutation scanning using MUT-MAP, a high throughput microfluidic chip-based multi-analyte panel. PLOS One. 2012 Dec 17;7(12):e51153. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051153, PMID 23284662.

Greenwood MP, Newton KM, Pepper KL, Hendrickson HL, Olsen RJ, Thomas JS. CALR frameshift mutation detection in myeloproliferative neoplasms by microfluidic chip analysis. Lab Med. 2024 Dec 24:lmae096. doi: 10.1093/labmed/lmae096, PMID 39719677.

Ohno KI, Tachikawa K, Manz A. Microfluidics: applications for analytical purposes in chemistry and biochemistry. Electrophoresis. 2008 Nov;29(22):4443-53. doi: 10.1002/elps.200800121, PMID 19035399.

Bein A, Shin W, Jalili Firoozinezhad S, Park MH, Sontheimer Phelps A, Tovaglieri A. Microfluidic organ-on-a-chip models of human intestine. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Jan 1;5(4):659-68. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2017.12.010, PMID 29713674.

Sekhwama M, Mpofu K, Sudesh S, Mthunzi Kufa P. Integration of microfluidic chips with biosensors. Discov Appl Sci. 2024 Aug 23;6(9):458. doi: 10.1007/s42452-024-06103-w.

Kim I, Kwon J, Rhyou J, Jeon JS. Microfluidic chips as drug screening platforms. JMST Adv. 2024 Jun 4;6(2):155-60. doi: 10.1007/s42791-024-00078-w.

Zhu Z, Cheng Y, Liu X, Ding W, Liu J, Ling Z. Advances in the development and application of human organoids: techniques applications and future perspectives. Cell Transplant. 2025 Jan;34:9636897241303271. doi: 10.1177/09636897241303271, PMID 39874083.

Yu L, Huang H, Dong X, Wu D, Qin J, Lin B. Simple fast and high throughput single cell analysis on PDMS microfluidic chips. Electrophoresis. 2008 Dec;29(24):5055-60. doi: 10.1002/elps.200800331, PMID 19130590.

Oksuz C, Bicmen C, Tekin HC. Dynamic fluidic manipulation in microfluidic chips with dead end channels through spinning: the spinochip technology for hematocrit measurement white blood cell counting and plasma separation. Lab Chip. 2025;25(8):1926-37. doi: 10.1039/d4lc00979g, PMID 39871622.

Zhou WM, Yan YY, Guo QR, Ji H, Wang H, Xu TT. Microfluidics applications for high throughput single cell sequencing. J Nanobiotechnology. 2021 Dec;19(1):312. doi: 10.1186/s12951-021-01045-6, PMID 34635104.

Mi F, Hu C, Wang Y, Wang L, Peng F, Geng P. Recent advancements in microfluidic chip biosensor detection of foodborne pathogenic bacteria: a review. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2022 Apr;414(9):2883-902. doi: 10.1007/s00216-021-03872-w, PMID 35064302.

Lehnert T, Gijs MA. Microfluidic systems for infectious disease diagnostics. Lab Chip. 2024;24(5):1441-93. doi: 10.1039/d4lc00117f, PMID 38372324.

Oushyani Roudsari Z, Esmaeili Z, Nasirzadeh N, Heidari Keshel S, Sefat F, Bakhtyari H. Microfluidics as a promising technology for personalized medicine. BioImpacts. 2025;15:29944. doi: 10.34172/bi.29944, PMID 39963565.

Apoorva S, Nguyen NT, Sreejith KR. Recent developments and future perspectives of microfluidics and smart technologies in wearable devices. Lab Chip. 2024;24(7):1833-66. doi: 10.1039/d4lc00089g, PMID 38476112.

Komalasari R. AI-powered wearables revolutionizing health tracking and personalized wellness management. Timor Leste J Bus Manag. 2024 Jul 23;6(1):42-50. doi: 10.51703/bm.v6i0.163.

Paul Kunnel BP, Demuru S. An epidermal wearable microfluidic patch for simultaneous sampling storage and analysis of biofluids with counterion monitoring. Lab Chip. 2022;22(9):1793-804. doi: 10.1039/d2lc00183g, PMID 35316321.

Shen H, Li Q, Song W, Jiang X. Microfluidic on-chip valve and pump for applications in immunoassays. Lab Chip. 2023;23(2):341-8. doi: 10.1039/d2lc01042a, PMID 36602133.

Pandey S, Gupta S, Bharadwaj A, Rastogi A. Microfluidic systems: recent advances in chronic disease diagnosis and their therapeutic management. Indian J Microbiol. 2025;65(1):189-203. doi: 10.1007/s12088-024-01296-5, PMID 40371020.

Liu Z, Zhou Y, Lu J, Gong T, Ibanez E, Cifuentes A. Microfluidic biosensors for biomarker detection in body fluids: a key approach for early cancer diagnosis. Biomark Res. 2024 Dec;12(1):153. doi: 10.1186/s40364-024-00697-4, PMID 39639411.

Kouhkord A, Naserifar N. Ultrasound assisted microfluidic cell separation: a study on microparticles for enhanced cancer diagnosis. Phys Fluids. 2025 Jan 1;37(1):12028. doi: 10.1063/5.0243667.

Zhao P, Wang J, Chen C, Wang J, Liu G, Nandakumar K. Microfluidic applications in drug development: fabrication of drug carriers and drug toxicity screening. Micromachines. 2022 Jan 27;13(2):200. doi: 10.3390/mi13020200, PMID 35208324.

Bokharaei M. Design and optimization of a microfluidic system for the production of protein drug loadable and magnetically targetable biodegradable microspheres (Doctoral dissertation, University of British Columbia); 1998.

Ren K, Zhou J, Wu H. Materials for microfluidic chip fabrication. Acc Chem Res. 2013 Nov 19;46(11):2396-406. doi: 10.1021/ar300314s, PMID 24245999.

Jenke D. Compatibility of pharmaceutical products and contact materials: safety considerations associated with extractables and leachables. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2009. doi: 10.1002/9780470459416.

Iyer V, Yang Z, KO J, Weissleder R, Issadore D. Advancing microfluidic diagnostic chips into clinical use: a review of current challenges and opportunities. Lab Chip. 2022;22(17):3110-21. doi: 10.1039/d2lc00024e, PMID 35674283.

Park J, Kim YW, Jeon HJ. Machine learning driven innovations in microfluidics. Biosensors. 2024 Dec 13;14(12):613. doi: 10.3390/bios14120613, PMID 39727877.

Fujii T. PDMS-based microfluidic devices for biomedical applications. Microelectron Eng. 2002 Jul 1;61-62:907-14. doi: 10.1016/S0167-9317(02)00494-X.

Darren L, Michael W. Microfluidic devices United States Patent US20080003142; 2008 Jan 3.

Gottfried R, Dario B. Method for manufacturing a microfluidic device United States Patent US10675619B2; 2020 Sep 9.

Zheng X, Yu Z. Microfluidic chip, United States Patent US11187224B2; 2021 Nov 30.

Joshua T, William L. Microfluidic chips with one or more vias, United States Patent US11458474B2; 2022 Oct 4.

Tiina M, Annukka K. Microfluidic chip and a method for the manufacture of a microfluidic chip, United States Patent US11759782B2; 2023 Sep 19.

Euan R, Robert T. Continuous flow microfluidic system, United States Patent US20210113974; 2024 Mar 26.