Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 4, 2025, 290-298Original Article

POTENTIATION OF CIPROFLOXACIN ACTIVITY BY CHALCONES BY MODULATING EFFLUX PUMP AND BIOFILM REGULATORY GENE IN STAPHYLOCOCCUS AUREUS

BHAWANDEEP KAUR1, SHASHIKANTA SAU2, SUMAN K. JANA1, NITIN PAL KALIA2*, GOPAL LAL KATHIK3, ASHISH SUTTEE4, SARIKA SHARMA5, SANDEEP SHARMA1*

1Department of Medical Laboratory Sciences, School of Allied Medical Sciences Lovely Professional University Phagwara (Punjab), India. 2Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, National Institute of Pharmaceutical Education and Research. Hyderabad, India. 3Department of Medicinal Chemistry, National Institute of Pharmaceutical Education and Research, Raebareli, India. 4Department of Pharmacognosy, Lovely Professional University, India. 5Department of Sponsored Research, Lovely Professional University, India

*Corresponding author: Sandeep Sharma; *Email: sandeep.23995@lpu.co.in

Received: 18 Mar 2025, Revised and Accepted: 05 May 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: Natural and synthetic compounds with dual activity to inhibit efflux pumps and biofilm production in Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) were investigated in this study. Chalcones emerged as potential compounds with the possibility to inhibit efflux pump and biofilm production at once.

Methods: We performed pre-clinical screenings of different chalcones-ciprofloxacin combinations with a NorA overexpressing S. aureus strain. Chalcones inhibition of the NorA efflux pump and Agr gene expression, a major regulator of biofilm formation, were tested. In silico modeling was also used to confirm the dual inhibitory activity of chalcones.

Results: Chalcones effectively modulated the action of ciprofloxacin by reducing the MIC by 2-8 fold and improving the time kill study, also inhibiting the NorA efflux pump and suppressing Agr gene expression, resulting in increased antibacterial activity and decreased biofilm formation.

Conclusion: The present research brings to the limelight chalcones as dual-function inhibitors aiming at efflux-based antibiotic resistance and biofilm formation in S. aureus with a potential strategy to repress drug-resistant infections.

Keywords: Chalcones, Efflux pump inhibition, Biofilm inhibition, Antibiotic resistance, Agr gene expression, S. aureus

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i4.54253 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) is a significant human pathogen that causes a variety of infections, ranging from mild skin infection to life-threatening conditions like sepsis and endocarditis [1]. The difficulty of treating this infection has been compounded by the emergence of methicillin-resistant S. aureus strains [2-4]. S. aureus resistance primarily arises through Horizontal Gene Transfer (HZT) and spontaneous mutation, enabling bacteria to overcome the action of antibiotics [5, 6]. One major resistance mechanism involves efflux pumps, particularly the NorA pump, which actively exports diverse antimicrobial agents from the cell, which contributes to multidrug resistance [7]. Yet another key determinant in S. aureus virulence is the Accessory Gene Regulator (Agr) system, a quorum-sensing network that regulates virulence factor expression and biofilm promotion [8]. Biofilm serves to protect from hostile environment, from antibiotics, and sustaining the overexpression of efflux system such as NorA. Both NorA and Agr inhibition constitute a promising line of attack in novel antimicrobial development. Ciprofloxacin, a fluoroquinolone antibiotic used extensively, acts on bacterial DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV. Ciprofloxacin activity is compromised by resistance mechanisms such as NorA overproduction, target mutations and biofilm formation. For the improvement of ciprofloxacin efficacy, ciprofloxacin is combined with other drugs such as gentamicin, minocycline or plant compounds like rutin [9-11]. Avicennia marina and Salix alba plant extracts have also revealed promising anti S. aureus activity because of their bioactive compounds [12]. Chalcones, a vital class of flavonoids, have garnered significant interest due to their broad-spectrum pharmacological properties, including antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant activities. Their structural versatility enables interactions with various biological targets, making them promising candidates for combating antibiotic resistance [13]. Among these targets, bacterial NorA efflux pumps and Agr quorum sensing pathways play critical roles in antibiotic resistance and pathogenicity of S. aureus. NorA efflux pumps contribute to multidrug resistance by actively extruding antibiotics, while the Agr quorum sensing system regulates virulence factor expression, enhancing bacterial survival and infection potential.

This research study aims to investigate the role of chalcones in combating drug resistance mediated by the NorA efflux pump and the Agr system's role in biofilm formation when used in combination with ciprofloxacin against S. aureus. Among the various chalcones explored, chalcone C9 was selected based on its superior inhibitory activity observed in preliminary screenings. A systematic evaluation of multiple chalcone derivatives was conducted to assess their potency against NorA efflux pump inhibition and Agr quorum sensing disruption. Comparative analysis revealed that C9 exhibited the highest efficacy in inhibiting NorA-mediated efflux and significantly attenuated Agr-regulated virulence factor expression. Additionally, its structural attributes, such as enhanced hydrophobicity and favourable molecular interactions with target proteins, supported its selection for detailed analysis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The S. aureus ATCC 29213 strain was procured from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) located in Manassas, Virginia. Two additional strains of S. aureus were generously provided by Dr. Nitin Pal Kalia from the National Institute of Pharmaceutical Education and Research (NIPER) in Hyderabad, India: SA1199B, which overexpresses the NorA efflux pump and its wild-type counterpart, S. aureus 1199. All chemicals, including antibiotics, required for this research project were sourced from Hi Media Laboratories, India. Dr. Gopal Kathik from the Department of Medicinal Chemistry at NIPER Raebareli, Uttar Pradesh, synthesized and supplied the fully characterized chalcone derivatives. The primers and real-time PCR (RT-PCR) kit were procured from Invitrogen.

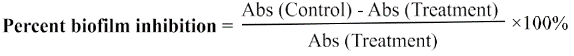

Time-kill studies of chalcones with ciprofloxacin

Time-kill kinetics approach was executed using the protocol previously released [14]. Ciprofloxacin coupled with chalcone C9 in Mueller Hinton Broth (MHB) was utilized to create a time-kill curve against the S. aureus strain SA-1199B. A bacterial suspension was made at a concentration of 1×106 CFU/ml. Separately, ciprofloxacin at a concentration of 2 mg/l [1/4×MIC] was examined separately and in combination with chalcone C9 at 25 mg/l [MEC of chalcone C9 determined earlier]. Moreover, MIC concentration of ciprofloxacin [8 mg/l] was evaluated. The bacterial suspensions were incubated at 37 °C. At set time periods, i. e., 0, 2, 4, 6, and 24 h, aliquots were collected, serial dilutions were made, and then it was spot plated on the media plates for the determination of bacterial colonies in CFU/ml [14]. The concentrations of ciprofloxacin (2 mg/l and 8 mg/l) and chalcone C9 (25 mg/l) were selected based on preliminary MIC assays and previously published studies on similar compounds. These concentrations were chosen to evaluate both the sub-inhibitory and inhibitory effects of ciprofloxacin, as well as potential synergistic interactions with chalcone C9.

Mutation prevention concentration and rate of mutation frequency

After an 18 h culture on trypticase soy agar, a bacterial solution containing 10[10] CFU/ml of S. aureus ATCC 29213 was created. 100 µl of this suspension was used as an aliquot and plated on MHA with ciprofloxacin at 4×, 8×, and 16× MIC concentrations. Chalcone and ciprofloxacin at 25 and 12.5 mg/l, respectively, were also examined at the same concentrations. Following a 48-hour incubation period at 37 °C, colonies were enumerated, mutation frequency was computed, and the concentration of mutation prevention was also ascertained [15].

Post-antibiotic effect (PAE) of effective combination

The PAEs of the ciprofloxacin alone and in combination with the chalcone were measured [16]. Ciprofloxacin was added at their MIC concentration to test tubes containing 106 CFU/ml each of the strain S. aureus 1199B. Chalcone C9 was also added in combination with ciprofloxacin at concentrations of 25 mg/l. Following a two-hour exposure to either chalcone C9 or the antibiotic ciprofloxacin, samples were diluted to a ratio of 1:1,000 in order to efficiently remove the medicines. Every 30 min, samples were collected for the CFU count until visible cloudiness was seen. The calculation of PAE was done with the following formula:

PAE = T− C Where T is the time to grow test culture by log10 CFU/ml above the count

That was seen right after the drug was removed and C is the time it takes for the count in the untreated control tube to rise by log10 CFU/ml.

Biofilm susceptibility of ciprofloxacin with chalcones (C9): biofilm inhibition (96 well plate)

The synergistic anti-biofilm activity of chalcone C9 when combined with ciprofloxacin antibiotic, was investigated with minor modifications as done in previously published relevant publications [17]. In a 96-well flat-bottom microtiter plate, 100 µl of SA-1199B bacterial culture (106 CFU/ml) and 100 µl of ciprofloxacin and chalcone C9 alone and in combination prepared as two-fold serial dilutions in tryptic soy broth supplemented with 2% sucrose, were added to each well and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. After incubation, each well was rinsed with 200 µl of Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS) to remove loosely attached, non-viable bacterial cells. Further, the plates were dried and stained with 0.1% Crystal Violet (CV) dye for 30 min under dark conditions at room temperature. Afterwards, the plates were washed three times with sterile PBS to remove unbound CV and finally solubilized in 33% glacial acetic acid. The absorbance at 595 nm was determined using a microplate spectrophotometer reader. The experiment was performed three times. The mean absorbance of each ciprofloxacin-chalcone combination was measured and percentage biofilm inhibition was calculated by using the formula,

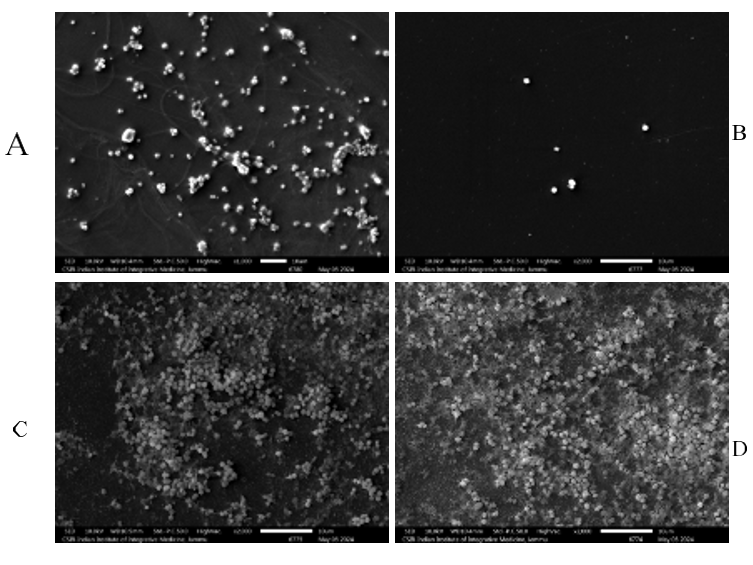

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) for biofilm inhibition

SEM was performed to observe the extent of biofilm inhibition and morphological changes induced within the bacterial cells upon treatment with ciprofloxacin and C9 alone as well as in combination. S. aureus SA-1199B cells were treated with C9 at concentration of 25 mg/l and ciprofloxacin at 1/4 × MIC concentration alone and in combination for 24h in 6-well plates containing thin films onto which biofilms were allowed to grow. After 24h incubation, the films were washed with sterile PBS solution (pH=7.4). Later fixation was done with 2.5% glutaraldehyde for a period of 24h by placing the plates containing the films at 4 °C. Next day; films were washed thrice with PBS and subjected to second fixation by 1% osmium tetroxide for 1h at 4 °C under dark conditions. Afterward, dehydration was done by employing ethanol at sequential concentrations of 10%, 50%, 70%, 80%, 90%, 95%, and 100% for 20 min each at a time. Final dehydration was carried out with isoamyl acetate and acetone (1:1) for 30 min followed by incubation with pure isoamyl acetate for 1h. Lastly, the films were kept in the desiccator until they were completely dry and finally, samples were mounted with gold before observation under the microscope [18].

Quantitative real-time study: expression studies to establish relation between AgrA and NorA genes in S. aurues: primer designing for qRT-PCR analysis

The sequences of all primers used in this study together with their amplicon length are listed in table 1. The Open Reading Frame (ORF) sequences of NorA, AgrA gene and 16S gene were taken from the genome sequence of S. aureus ATCC 29213. Primer pairs were designed using PRIMER3 software and synthesized by Eurofin. The housekeeping gene 16S was taken as an internal control for the normalization of mRNA levels in the samples as well as control RNA isolated from S. aureus ATCC 29213 grown in cation adjusted by MHB.

Table 1: List of the sequences of all primers with their amplicon length

| Gene | Primer sequences | Annealing temp |

| 16s | F: TGAGTAACACGTGGATAACCTAC | |

| R: CGGATCCATCTATAAGTGACAG | 62 °C | |

| norA | F: CAGCTATTAAACCTGTCACACC | 62 °C |

| R: AGCTATTAAACCTGTCACACCAG | ||

| agrA | F: TGTCTACAAAGTTGCAGCGATG | 62 °C |

| R: TAAATGGGCAATGAGTCTGTGAG |

RNA extraction

MHB was used to cultivate overnight cultures of S. aureus ATCC 29213, for planktonic and biofilm formation (described in biofilm section), which were harvested by centrifugation into 10 ml aliquots. Following centrifugation, the cell pellets were transferred to tubes holding a mixture of 0.2 ml glass beads, 0.2 ml chloroform, and 1 ml TRIZOL Reagent (Invitrogen, CA, USA). The tubes were vortexed and violently shaken for 15 to 30 seconds before being incubated for 5 to 15 min at room temperature. Following that, the samples were centrifuged for 15 min at 4 °C at 12,000 × g. After carefully removing the top aqueous phase containing the total RNA and transferring it to a fresh 1.5 ml centrifuge tube, each sample received 0.5 ml of isopropyl alcohol. After 10 min of room temperature incubation, the tubes were centrifuged for 8 min at 4 °C at 12,000 × g. After twice washing the pellet with 1 cc of Merck's 75% ethanol, it was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. The RNA pellet was dissolved in water that was free from DNase and RNase contamination, it was heated to 55 °C for 10 min.

Quantification of RNA

Quantification of RNA was done using nanodrop. The sterile Milli Q Water (MQ water) was used to set blank. A ratio of 2.1 of 260/280 wavelengths is an indication of good quality of RNA. All the RNA quantification was done using the same procedure.

First-strand cDNA synthesis

Takara Bio Inc.'s PrimeScript 1st Strand cDNA synthesis kit was used to synthesis cDNA. To successfully eliminate contaminating genomic DNA, 1µg of pure sample of RNA was quickly treated in gDNA wipeout buffer at 42 °C for 2 min. The RNA sample was processed for reverse transcription using a master mix made from Primescript Reverse Transcriptase, oligo dT and random 6-mer primers included in the kit after genomic DNA was removed. After 15 min of incubation at 42 °C, the reaction tubes were inactivated for 3 min at 95 °C. The same procedure was followed for all cDNA synthesis process.

Relative expression studies

Two sets of primer pairs amplifying portions of the Nora and agrA ORF were used in SYBR Green quantitative PCR on the resultant cDNA and the negative control (without cDNA) in a Bio-Rad CFX Opus 96 System. The critical Threshold Cycle (CT) is the cycle number at which fluorescence exceeds background levels and is inversely proportional to the logarithm of the initial template concentration. A standard curve was plotted for the 16S rRNA gene as previously mentioned. In a 20 μl reaction volume, a two-step real-time PCR was conducted.

10 pmol of each primer (2 µl), 10 µl of SYBR Green I master mix, 2 µl of cDNA (1:10 dilution of cDNA from 1 µg of total RNA), and a reaction volume made up of nuclease-free water comprised the RT-PCR mixture. The methodology for the real-time PCR run included a 45-cycle amplification process (10 s at 95 °C, 20 s at 62 °C, and 20 s at 72 °C), with a single fluorescence reading acquired at the conclusion of each cycle. The PCR was activated at 95 °C for 10 min. The 16S rRNA gene was used as an endogenous reference to normalize the quantitative data for NorA and AgrA. The expression of both genes was measured in S. aureus ATCC 29213 planktonic cell relative to Biofilm. Each experiment was performed in triplicate. The effect of proposed Chalcone (a known NorA EPI) on expression of NorA and agrA genes was compared.

In silico studies

Preparation of the NorA target via homology modelling

To better comprehend the binding relationship with a NorA MFS protein, a 3D homology model was constructed using Uniport Q5HHX4 protein sequence with UniParc-UPI00000522D0 and contrasted to EmrD MFS from E. coli with pdb ID: 2G as described in previous studies with slight modifications [19, 20]. It was further assessed employing the Swiss Model [20], and the binding site was chosen as described in two research publications [21, 22].

Molecular docking C9 compared with capsaicin for NorA and Agr inhibition

Autodock vina (a molecular docking software) was utilized for investigating the interaction of modeled NorA protein with Capsaicin and C9. Likewise, both the ligands were evaluated on Agr, a gene cascade that governs biofilm development in S. aureus. An accessible pdb 4bxi was downloaded from RCSB and made ready for the docking analysis.

Statistical analysis

For every experiment, three duplicates of each experiment were carried out. The data is shown as mean±SD. Statistical comparisons between two group means were performed using the student’s t-test, whereas one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed for multiple group comparisons, with a significance threshold set at P<0.05

RESULTS

Time-kill studies of chalcones with ciprofloxacin

The time-kill curve analysis of S. aureus mutant SA-1199B was used to evaluate the bactericidal efficacy of ciprofloxacin alone and in combination with chalcone C9. Ciprofloxacin had no inhibitory effect on cell growth when employed at a sub-inhibitory concentration of 2 mg/l (1/4 × MIC), but at 8 mg/l, it showed bactericidal efficacy (99.9% kill) within 6 h. Moreover, bactericidal activity was reported when the combination of ciprofloxacin at 2 mg/l and chalcone C9 at 25 mg/l was evaluated. The combined bactericidal activity was comparable to that obtained with 8 mg/l ciprofloxacin. Despite the pathogen recovery after 24h in all the test groups, the combination of ciprofloxacin and Chalcone C9 maintained its bacteriostatic action, holding the final log10 CFU below the initial inoculum at the time of commencement of the experiment (0h) (fig. 1). These results imply that chalcone C9 can enhance ciprofloxacin action against mutant S. aureus strain 1199B, thus providing a novel strategy for combating antibiotic resistance in this bacterium.

Fig. 1: Time–kill curves of S. aureus SA-1199B demonstrating the bactericidal action of ciprofloxacin (1/4× MIC, 2 mg/l) combined with chalcone C9 (25 mg/l). The individual time point was the average log10+SD of the three readings

Mutation prevention concentration and rate of mutation frequency

The probability of mutant development against ciprofloxacin and its combination with C9 was investigated in S. aureus. S. aureus ATCC 29213, a wild-type strain lacking any known mutations in the NorA regulatory domain or drug target domain (which included DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV), was used in a mutant selection experiment. Since ciprofloxacin did not cause any mutant formation at a minimal concentration of 4 mg/l (16 × MIC), this value is known as the Mutant Prevention Concentration (MPC).

However, when ciprofloxacin was combined with chalcone C9 at doses of 12.5 mg/l and 25 mg/l, the MPC values dropped to 2 and 1 mg/l, respectively. Moreover, the combination’s MPC was lower than ciprofloxacin’s maximum concentration (i. e., Cmax value of 4 mg/l), implying that these combinations could be clinically significant in preventing the evolution of resistant bacterial mutants (table 2).

Table 2: Mutation frequency of S. aureus ATCC 29213

Chalcone (C-9) (mg/l) |

Mutation frequency with ciprofloxacin | |||

| 2 × MIC (0.5 mg/l) | 4 × MIC (1.0 mg/l) | 8 × MIC (2.0 mg/l) | 16 × MIC (4.0 mg/l) | |

| 0 | 4 × 10-8 | 1 × 10-8 | 2 ×<10-9 | <10-9 |

| 12.5 | 8 × 10-8 | 4.5 × 10-9 | <10-9 | <10-9 |

| 25 | 2.0 × 10-9 | <10-9 | <10-9 | <10-9 |

PAE of effective combinations

PAE studies revealed that in conjunction with chalcone C9, ciprofloxacin was able to suppress the pathogen growth for longer periods even after the removal of the antibiotic with longer suppression observed as the doses of antibiotic employed increased (table 3).

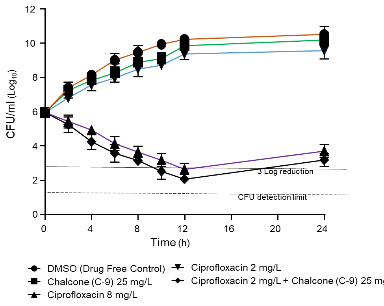

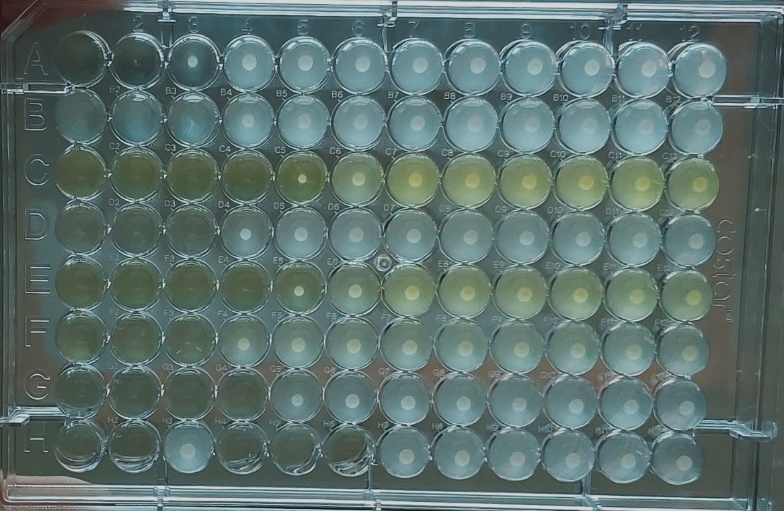

Biofilm susceptibility of ciprofloxacin in combination with chalcones (C9) biofilm inhibition (96 well plate)

The study investigated the impact of chalcone C9 on the Minimum Biofilm Inhibitory Concentration (MBIC50) of ciprofloxacin against S. aureus ATCC 29213. The results confirm a notable influence of C9 on the efficacy of ciprofloxacin in inhibiting biofilm formation (fig. 2). Although the chalcone on its own had no significant effect in biofilm inhibition at concentrations of 50 mg/l, 25 mg/l, and 12.5 mg/l, respectively, but in conjunction with ciprofloxacin, it was observed that lower dose concentration of C9 of 12.5 mg/l produced almost negligible potentiation of ciprofloxacin’s efficacy. At 25 mg/l of C9, MBIC50 of ciprofloxacin enhanced by 13%, whereas with 50 mg/l concentration of C9, most pronounced reduction in MBIC50 was obtained, potentiating the antibiotic’s biofilm inhibition potential by almost 58% (Data represented in table 4, fig. 3).

Table 3: Post-antibiotic effect with chalcone C-9 and ciprofloxacin

| Chalcone (EPI mg/l) | PAE’s(h) | |||

| ¼ ×MIC(2 mg/l) | ½ ×MIC(4 mg/l) | MIC(8 mg/l) | ||

| Without C-9 | 0.4±0.1 | 1.25±0.5 | 1.45±0.5 | |

| C-9(25 mg/l) | 1.0±0.3 | 1.45±1 | 2.5±0.25 | |

Fig. 2: 96 well plate showing a synergistic effect

Table 4: MBIC50 of ciprofloxacin against S. aureus ATCC 29213 when used in combination with Chalcone C9

| Chalcone C-9 (mg/l) | MBIC50 of ciprofloxacin against S. aureus ATCC 29213 in combination with C9 |

| 0 | 0.33 |

| 12.5 | 0.32 |

| 25 | 0.29 |

| 50 | 0.14 |

Fig. 3: MBIC50 of ciprofloxacin against S. aureus ATCC 29213 when used in combination with chalcone C9 (represented in terms of OD)

SEM for biofilm inhibition

The SEM micrographs were obtained to demonstrate that chalcone C9 at the sub-inhibitory dose of 25 mg/l had no discernible effect on suppressing the S. aureus SA-1199B bacterial biofilms (fig. 4C), but treatment with 1/4 × MIC concentration of ciprofloxacin resulted in a moderate reduction in biofilm cell mass (fig. 4A). However, when a combination of C9 (25 mg/l) and ciprofloxacin (1/4 × MIC) was evaluated, the SEM pictures revealed a significant inhibitory effect of this synergistic combination (fig. 4B) on S. aureus SA-1199B biofilm development compared to biofilms produced by untreated control (fig. 4D).

Fig. 4: SEM images demonstrating the antibiofilm effect induced on the S. aureus ATCC 1199B treated with ciprofloxacin at 2 mg/l, (A)S. aureus ATCC 1199B treated with ciprofloxacin at 1/4×MIC(2 mg/l)(Reduced Biofilm Cell mass), (B) Combination[Ciprofloxacin(2 mg/l)+ChalconeC9(25 mg/l)](Significant Biofilm Inhibition), (C) Chalcone C9 at 25 mg/l alone(No Noticeable effect), (D) Untreated controlled (Dense biofilm formation)

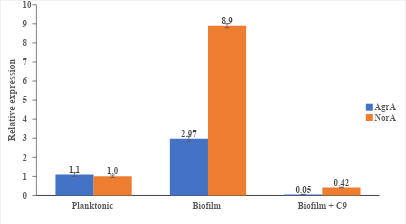

Fig. 5: Biofilm induced co-overexpression of AgrA and NorA and impact of chalcones on expression of both the genes

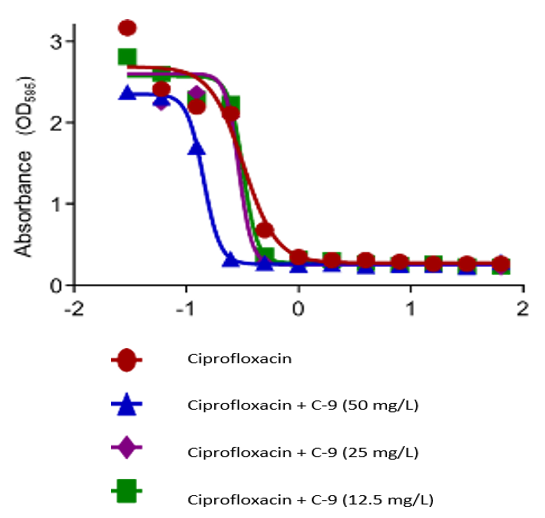

qRT PCR analysis

For the NorA and AgrA gene, S. aureus ATCC 29213 was grown in the presence and absence of C9 (at MEC). The results of the qRT-PCR research showed that AgrA and NorA expression considerably increased in biofilm-associated to 2.97 fold and 8.9 fold respectively, when compared to planktonic cells. However, the expression of both AgrA and NorA was significantly downregulated to decimal points in biofilm-associated cells in the presence of C9 when compared with planktonic cells (fig. 5).

In silico studies

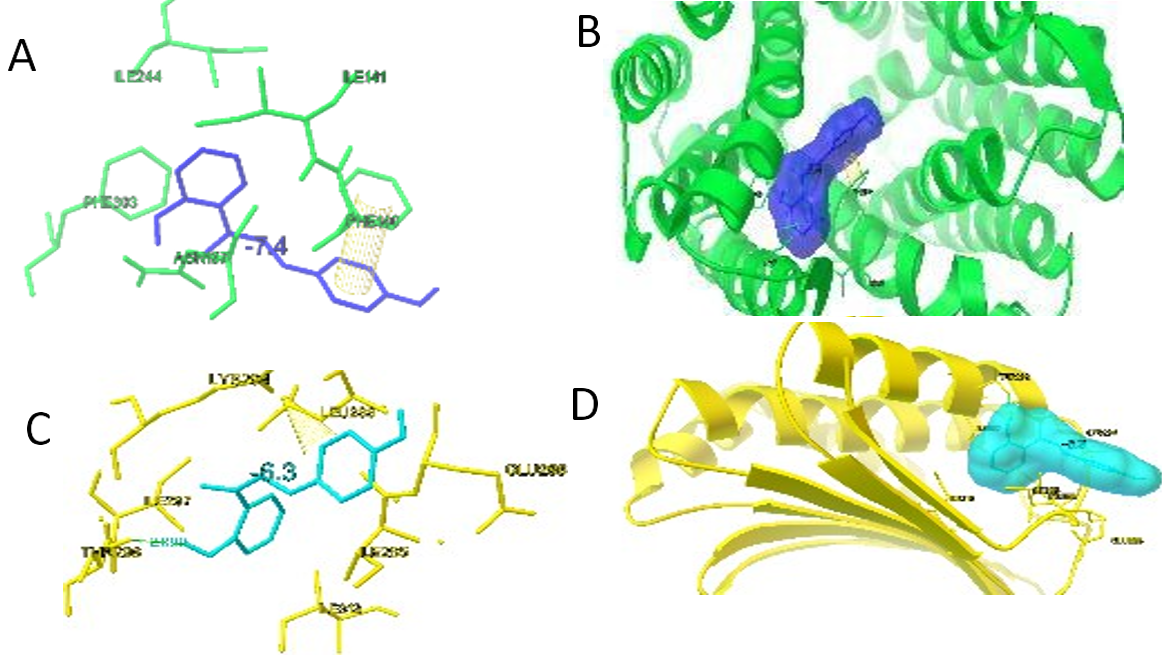

Molecular docking C9 compared with capsaicin for NorA and Agr inhibition

Finally, the interaction between capsaicin and C9 was analyzed for the NorA protein and the Agr gene of S. aureus. Autodock vina results showed that the binding site residues in NorAwere Phe16, Ile19, Ile23, Gln61, Met109, Glu222, Ile244, Phe303, Arg 310, Asn340, and Phe341. Capsaicin and C9 showed binding affinities of-6.7 kcal/mol and 7.4 kcal/mol, respectively, in the NorA protein (table 5) C9 is involved in hydrophobic interactions at amino acid residues such as Phe140, Ile141, and Ile244 and shows π-stacking of the aryl ring with Phe140 (fig. 6a and 6b).

The binding site residues observed in the Agr gene are Ile285, Glu286, Leu288, Lys294, Ile297, Thr298, and Ile313. The binding affinities of capsaicin and C9 to the Agr gene were 6.3 and -6.3 kcal/mol, respectively. C9 molecules were observed to have hydrophobic interactions with Ile285, Leu288, Ile297, and Ile313. It was also found to form a hydrogen bond with Thr298 and its hydroxyl functional group. Furthermore, a strong cation-π interaction was observed between the aryl ring and Lys294 (fig. 6d and 6c).

Table 5: Docking results using Autodock vina

| S. No. | Molecule | NorA | Agr |

| Binding residues | Binding affinity (kcal/mol) |

||

| 1 | Capsaicin | Phe16, Ile19, Ile23, Gln61, Met109,Ile244,Phe303, and Asn340 | -6.7 |

| 2 | C9 | Asn137,Phe140,Ile141, Ile244, and Phe303 | -7.4 |

C9 is possibly a promising inhibitor of the NorA and Agr genes compared to capsaicin, reflecting its potential to mitigate biofilm-assisted drug resistance in microbes.

Fig. 6: Binding interaction of C9 (a) ball and stick model NorA (green), C9 (blue), (b) ribbon structure NorA(green), C9 (blue), (c) ball and stick model Agr(yellow), C9 (blue), (d) ribbon structure Agr(yellow), C9 (blue)

DISCUSSION

The bacterial pathogen S. aureus, is popular for causing infectious illnesses of varying severity in animals and humans combined. The search for potent molecules, regardless of their source of origin (natural or synthetic), that can assist researchers to combat the spread of silent AMR pandemic by reversing the resistance is a daunting task [23, 24].

Chalcones are natural molecules containing two aromatic rings linked by an α, β-unsaturated carbonyl group. They exhibit numerous biologically essential properties, including antimalarial, antibacterial, anticancer, antifungal, antioxidant, neuroprotective action, anti-inflammatory, and much more [25]. Chalcones exert their antibacterial effect by obstructing the efflux pumps, which are in control of removing chemicals and drugs from the bacterial cells that are detrimental to them in nature [26]. Inhibiting the efflux pumps might boost antibiotic efficacy whilst reducing the issues of multidrug resistance. Moreover, the Chalcones have been shown to block NorA, an efflux pump found in S. aureus, a g-positive bacterium that is a causative agent for numerous illnesses in humans and animals. NorA is responsible for providing resistance to pathogens against numerous clinically important antibiotic classes, including fluoroquinolones, phenothiazines, quaternary ammonium compounds, and dyes [27]. Hence, chalcones offers promising prospects as an antibacterial agent against MRSA. Several studies have focused on the synthesis and assessment of chalcone derivatives as NorA inhibitors, as well as their modulatory activities towards ciprofloxacin since this drug is widely used to treat S. aureus-associated bacterial infections [27-29].

The investigation into the antibacterial properties of chalcone derivatives against S. aureus revealed significant findings regarding their potential as antibiotic adjuncts. The initial agar well diffusion assay results revealed that various chalcone derivatives that we tested in our study, i. e., Chalcone C1, C3, C4, C5, C7-11, C13, C15, and C16, did not show any Zone Of Inhibition (ZOI) when tested alone. This lack of intrinsic antibacterial activity suggests that these compounds may not be effective in combating S. aureus. This is consistent with previous research showing that many chalcones exhibit variable antibacterial activity depending on their structural characteristics and bacterial strains used [27, 30].

However, further testing of chalcones in conjunction with ciprofloxacin demonstrated a significant increase in antibacterial activity, particularly for chalcone C9. With ciprofloxacin at a dose concentration of 5 mg/l, C9 showed potentiation forming ZOI equal to 16.5 mm, 18 mm, and 20 mm at employed concentrations of 12.5 mg/l, 25 mg/l, and 50 mg/l, respectively. This synergistic impact highlights the ability of chalcone C9 to improve ciprofloxacin’s efficacy, particularly in the context of MRSA as reported earlier [28].

Moreover, the in vitro checkerboard results in our research work demonstrated that upon combining chalcone C9 with ciprofloxacin, the minimum inhibitory concentration of ciprofloxacin reduced 2-8 folds in the two strains of S. aureus, i. e., S. aureus ATCC 1199, and S. aureus ATCC 1199B. This synergistic interaction appears to be caused by chalcone C9's capacity to inhibit NorA, consistent with the findings [31], which also reported enhanced antibacterial activity upon NorA inhibition.

The time-kill curve assay confirmed the synergistic bactericidal action of Chalcone C9 in conjunction with ciprofloxacin. This combination had a 99.9% kill rate at sub-inhibitory concentrations, indicating that C9 can improve ciprofloxacin efficacy even at lower dosage concentrations, potentially reducing the life-threatening risks of toxicity associated when higher dosage concentrations are involved. Furthermore, the combination displayed a much longer PAE than ciprofloxacin alone, indicating persistent suppression of pathogen growth, which is very critical for optimizing the dosage regimens and minimizing the chances of resistance development.

Another critical feature of this study was the assessment of chalcone C9’s effect on biofilm development by S. aureus. Biofilms are complex bacterial populations concealed in a self-generated extracellular matrix that provide resistance to antimicrobial agents and immune responses and protecting against bacterial pathogens [32]. The development of bacterial biofilms is influenced by several factors, with quorum sensing being a critical one. This complex communication network allows bacteria to modulate gene expression in response to change in cell density, facilitating coordinated behaviour and adaptation. In the case of S. aureus, QS is mediated via the agr system, which regulates the production of bacteria’s virulence factors such as Alpha-Hemolysin (Hla) and biofilm-associated genes like icaA [33]. Biofilm inhibition studies predicted that Chalcone C9 possesses the potential to enhance ciprofloxacin’s capacity to penetrate or disrupt biofilm formation or it is likely that it may have direct role in the bacteria’s ability to form biofilms. The prediction was made based on the fact that with increasing concentrations of chalcone C9 used, the ciprofloxacin’s ability to inhibit biofilms produced by S. aureus ATCC 29213 strengthened with most pronounced effect produced at 50 mg/l concentration of C9. The association of agrA and norA gene was revealed during biofilm formation. The overexpression of norA and agrA in biofilm-associated cells made it clear the dependency of both the genes on expression of each other. Further, C9 a proposed NorA inhibitor, inhibited the expression of both the genes. (as depicted in fig. 5). Subsequently, the SEM imaging revealed that C9 when used at sub-inhibitory concentration of 25 mg/l had no obvious impact in suppressing S. aureus SA-1199B bacterial biofilms, whereas treatment with ¼ × MIC concentration of ciprofloxacin induced mild reduction in biofilm cell mass. However, in case combination of C9 (25 mg/l) with ciprofloxacin (1/4 × MIC) was tested, SEM images visually confirmed substantial inhibitory effect of this synergistic combination on the formation of S. aureus SA-1199B biofilms. These findings could have significant clinical implications, potentially allowing for lower doses of ciprofloxacin to be used in treating S. aureus biofilm-associated infections when combined with Chalcone C9.

Importantly, Chalcone C9 demonstrated inadequate potential for generating resistant mutants in S. aureus. Ciprofloxacin’s MPC was reduced by 2-4 folds in the presence of chalcone C9, indicating that the combination may successfully prevent resistance in vitro. This discovery highlights the chalcone C9’s potential as an adjuvant for fighting MRSA infections and emerging antibiotic resistance.

The interaction of ligand capsaicin and C9 was analysed on NorA protein and Agr gene of S. aureus. The Autodock vina results showed the binding site residues at NorA are Phe16, Ile19, Ile23, Gln61, Met109, Glu222, Ile244, Phe303, Arg 310Asn340, and Phe341. Capsaicin, and C9 showed binding affinities of-6.7 kcal/mol, and-7.4 kcal/mol, respectively on NorA protein (table 5). C9 is involved in the hydrophobic interaction at the amino acid residues like Phe140, Ile141, Ile244 and also showed the π-stacking of the aryl ring with Phe140 (fig. 6a and 6b).

The binding site residues observed in the Agr gene are Ile285, Glu286, Leu288, Lys294, Ile297, Thr298 and Ile313. The binding affinities of Capsaicin, and C9 on the Agr gene were -6.3 kcal/mol, and-6.3 kcal/mol, respectively. C9 molecules were observed to have hydrophobic interaction with Ile285, Leu288, Ile297, and Ile313. It was also found to have a hydrogen bond with Thr298 and its hydroxyl functional group. Further a strong cation – π interaction was noted between aryl ring and Lys294 (fig. 6b and 6 c).

To summarize, the findings of this study emphasize the potential of chalcone C9 as a beneficial adjuvant in the treatment of MRSA infections, particularly through its ability to improve ciprofloxacin efficacy and regulate the resistance pathways. Further research, especially in vivo studies, is needed to fully understand the clinical significance of these findings and to investigate the therapeutic potential of the chalcone derivatives in combating antibiotic resistance.

CONCLUSION

The research indicates Chalcone C9 as a potential adjuvant to fight MRSA infection by maximizing ciprofloxacin potency and addressing the mechanisms of bacterial resistance. C9 had no direct antibacterial effect, yet it greatly improves bacterial susceptibility upon combination with ciprofloxacin, indicated by agar well diffusion, checkerboard and time-kill assays. Specifically, C9 blocked the NorA efflux pump and inhibited biofilm growth, lowering the MIC of ciprofloxacin and increasing bacterial eradication. Molecular docking validated high binding affinities of C9 to NorA and Agr genes, which also justified its use in overcoming antibiotic resistance. Moreover, C9 was able to suppress biofilm-associated gene expression and exhibited reduced potential for resistance development. These results highlight the therapeutic potential of chalcones derivatives in the treatment of MDR S. aureus infection.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The management of Lovely Professional University is acknowledged by the authors for providing the facilities required for the study.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

The inspiration for the topic is given by Dr. Sandeep Sharma, Dr. Nitin Pal Kalia, Dr. Sarika Sharma, Dr. Gopal Lal Kathik and Dr. Ashish Suttee. The framework was designed by Bhawandeep Kaur, Dr. Sandeep Sharma and Dr. Nitin Pal Kalia. A literature survey was done by Bhawandeep Kaur, Suman K Jana and Dr. Sandeep Sharma.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Taylor TA, Unakal CG. Staphylococcus aureus infection. In: Treasure Island, (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jul 17. PMID 28722898.

Karmakar A, Dua P, Ghosh C. Biochemical and molecular analysis of staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates from hospitalized patients. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2016;2016:9041636. doi: 10.1155/2016/9041636, PMID 27366185, PMCID PMC4904573.

C MB, Pv PB, Jyothi P. Drug resistance patterns of clinical isolates of staphylococcus aureus in Tertiary Care Center of South India. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2015 Jul;7(7):70-2.

Sharma S, Bhandari U, Oli Y, Bhandari G, Bista S, Gc G, Shrestha B, Bhandari NL. Identification and detection of biofilm-producing staphylococcus aureus and its antibiogram activities. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2021 Apr;14(4):150-6. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2021.v14i4.40728.

Michaelis C, Grohmann E. Horizontal gene transfer of antibiotic resistance genes in biofilms. Antibiotics (Basel). 2023 Feb 4;12(2):328. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics12020328, PMID 36830238, PMCID PMC9952180.

Ranjbar R, Alam M. Antimicrobial resistance collaborators (2022). Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Evid Based Nurs. 2023 Jul;27(1):2022-103540. doi: 10.1136/ebnurs-2022-103540, PMID 37500506.

Costa SS, Junqueira E, Palma C, Viveiros M, Melo Cristino J, Amaral L. Resistance to antimicrobials mediated by efflux pumps in staphylococcus aureus. Antibiotics (Basel). 2013 Mar 13;2(1):83-99. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics2010083, PMID 27029294, PMCID PMC4790300.

Sionov RV, Steinberg D. Targeting the holy triangle of quorum sensing biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance in pathogenic bacteria. Microorganisms. 2022 Jun 16;10(6):1239. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10061239, PMID 35744757, PMCID PMC9228545.

Kaatz GW, Seo SM. Effect of substrate exposure and other growth condition manipulations on nora expression. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004 Aug;54(2):364-9. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh341, PMID 15231765.

Dickgiesser N, In der Stroth S, Wundt W. Synergism of ciprofloxacin with beta-lactam antibiotics gentamicin minocycline and pipemidic acid. Infection. 1986;14(2):82-5. doi: 10.1007/BF01644449, PMID 2940188.

Mourad T, Alahmad S. A computational study of ciprofloxacin metabolites and some natural compounds against resistant methicillin staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2022 Aug;14(8):22-8. doi: 10.22159/ijpps.2022v14i8.44560.

Permatasari L, Muliasari H, Rahman F. Characterization of isolated crystals from mangrove leaves (Avicennia marina and Sonneratia alba) and their antibacterial activity against staphylococcus aureus. Int J App Pharm. 2024;16(5):77-82. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2024v16s5.52480.

Salehi B, Quispe C, Chamkhi I, El Omari N, Balahbib A, Sharifi Rad J. Pharmacological properties of chalcones: a review of preclinical including molecular mechanisms and clinical evidence. Front Pharmacol. 2020 Jan 18;11:592654. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.592654, PMID 33536909, PMCID PMC7849684.

Talia JM, Debattista NB, Pappano NB. New antimicrobial combinations: substituted chalcones oxacillin against methicillin resistant staphylococcus aureus. Braz J Microbiol. 2011 Apr;42(2):470-5. doi: 10.1590/S1517-838220110002000010, PMID 24031657, PMCID PMC3769842.

Xedzro C, Tano Debrah K, Nakano H. Antibacterial efficacies and time-kill kinetics of indigenous ghanaian spice extracts against Listeria monocytogenes and some other food-borne pathogenic bacteria. Microbiol Res. 2022 May;258:126980. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2022.126980, PMID 35158300.

Sharma S, Kumar M, Sharma S, Nargotra A, Koul S, Khan IA. Piperine as an inhibitor of Rv1258c, a putative multidrug efflux pump of mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010 Aug;65(8):1694-701. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq186, PMID 20525733.

Nair S, Desai S, Poonacha N, Vipra A, Sharma U. Antibiofilm activity and synergistic inhibition of staphylococcus aureus biofilms by bactericidal protein P128 in combination with antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016 Nov 21;60(12):7280-9. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01118-16, PMID 27671070, PMCID PMC5119008.

Chino T, Nukui Y, Morishita Y, Moriya K. Morphological bactericidal fast acting effects of peracetic acid a high-level disinfectant against staphylococcus aureus and pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms in tubing. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2017 Dec 1;6:122. doi: 10.1186/s13756-017-0281-1, PMID 29214017, PMCID PMC5709933.

Letters. Corrections and clarifications. Science. 2007;317(5845):1682. doi: 10.1126/science.317.5845.1682.

Zarate SG, Morales P, Swiderek K, Bolanos Garcia VM, Bastida A. A molecular modeling approach to identify novel inhibitors of the major facilitator superfamily of efflux pump transporters. Antibiotics (Basel). 2019 Mar 15;8(1):25. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics8010025, PMID 30875968, PMCID PMC6466568.

Waterhouse A, Bertoni M, Bienert S, Studer G, Tauriello G, Gumienny R. Swiss Model: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018 Jul 2;46(W1):W296-303. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky427, PMID 29788355, PMCID PMC6030848.

Kalia NP, Mahajan P, Mehra R, Nargotra A, Sharma JP, Koul S. Capsaicin a novel inhibitor of the nora efflux pump reduces the intracellular invasion of staphylococcus aureus. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012 Oct;67(10):2401-8. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks232, PMID 22807321.

Costa LM, De Macedo EV, Oliveira FA, Ferreira JH, Gutierrez SJ, Pelaez WJ. Inhibition of the nora efflux pump of staphylococcus aureus by synthetic riparins. J Appl Microbiol. 2016 Nov;121(5):1312-22. doi: 10.1111/jam.13258, PMID 27537678.

CM, SAS, VPA, PPN. Factors that favour the spread of bacterial resistance. Int J Curr Pharm Sci. 2021 Sep;13(5):108-9. doi: 10.22159/ijcpr.2021v13i5.1905.

Rammohan A, Reddy JS, Sravya G, Rao CN, Zyryanov GV. Chalcone synthesis properties and medicinal applications: a review. Environ Chem Lett. 2020;18(2):433-58. doi: 10.1007/s10311-019-00959-w.

Holler JG, Slotved HC, Molgaard P, Olsen CE, Christensen SB. Chalcone inhibitors of the nora efflux pump in staphylococcus aureus whole cells and enriched everted membrane vesicles. Bioorg Med Chem. 2012 Jul 15;20(14):4514-21. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.05.025, PMID 22682300.

Da Silva PT, Da Cunha Xavier J, Freitas TS, Oliveira MM, Coutinho HD, Leal AL. Synthesis spectroscopic characterization and antibacterial evaluation of chalcones derived from acetophenone isolated from croton anisodontus mull. Arg. J Mol Struct. 2021;1226(B):129403. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.129403.

Siqueira MM, Freire PT, Cruz BG, De Freitas TS, Bandeira PN, Silva Dos Santos H. Aminophenyl chalcones potentiating antibiotic activity and inhibiting bacterial efflux pump. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2021 Mar 1;158:105695. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2020.105695, PMID 33383131.

Rezende Junior LM, Andrade LM, Leal AL, Mesquita AB, Santos AL, Neto JS. Chalcones isolated from arrabidaea brachypoda flowers as inhibitors of NorA and MepA multidrug efflux pumps of staphylococcus aureus. Antibiotics (Basel). 2020 Jun 20;9(6):351. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9060351, PMID 32575738, PMCID PMC7345224.

Rana P, Supriya MS, Kalam A, Eedulakanti C, Kaul G, Akhir A. Synthesis and antibacterial evaluation of new naphthalimide coumarin hybrids against multidrug-resistant S. aureus and M. tuberculosis. J Mol Struct. 2024 Jul 5;1307:137957. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2024.137957.

Nargotra A, Sharma S, Koul JL, Sangwan PL, Khan IA, Kumar A. Quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) of piperine analogs for bacterial NorA efflux pump inhibitors. Eur J Med Chem. 2009 Oct;44(10):4128-35. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2009.05.004, PMID 19523722.

Aboelnaga N, Elsayed SW, Abdelsalam NA, Salem S, Saif NA, Elsayed M. Deciphering the dynamics of methicillin resistant staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation: from molecular signaling to nanotherapeutic advances. Cell Commun Signal. 2024 Mar 22;22(1):188. doi: 10.1186/s12964-024-01511-2, PMID 38519959, PMCID PMC10958940.

Wang B, Muir TW. Regulation of virulence in staphylococcus aureus: molecular mechanisms and remaining puzzles. Cell Chem Biol. 2016 Feb 18;23(2):214-24. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2016.01.004, PMID 26971873, PMCID PMC4847544.