Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 5, 2025, 308-314Original Article

COLOUR STABILITY OF COMPOSITE RESINS IN THE PRESENCE OF HERBAL TEAS: A SPECTROPHOTOMETRIC STUDY

GOWRISH S., VANDANA SADANANDA*, MURTAZA HATIM ZAKIYUDDIN

Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics, Deralakatte, Mangaluru-575018, Karnataka, India

*Corresponding author: Vandana Sadananda; *Email: drvandanasadananda@nitte.edu.in

Received: 21 Mar 2025, Revised and Accepted: 24 Jun 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: This study aimed to evaluate and compare the effects of four herbal teas, Amla (Emblica officinalis), Hibiscus (Hibiscus sabdariffa), Moringa (Moringa oleifera), and Tulsi (Ocimum sanctum) on the colour stability of three composite restorative materials, nanohybrid composite resin, bulk-fill flowable composite and nanohybrid composite resin with SphereTEC fillers, over 60 d using spectrophotometric analysis.

Methods: A total of 150 disc-shaped composite specimens were fabricated and divided into three groups: Nanohybrid composite resin (Group I), bulk-fill flowable composite (Group II) and nanohybrid composite resin with SphereTEC fillers (Group III). Each group was further divided into five subgroups (n=10), which were immersed daily in Amla, Hibiscus, Moringa, Tulsi tea, and in artificial saliva (control), for 15 min over 60 d. Colour changes were assessed at baseline, day 30, and day 60 using a digital reflectance spectrophotometer, and ΔE* values were calculated according to the CIELAB system.

Results: At day 60, Tulsi tea induced the highest discolouration across all composite resins, with mean ΔE values of 36.21±0.37 (Group I), 37.39±0.40 (Group II), and 37.83±0.60 (Group III). Hibiscus and Amla teas also produced notable staining (ΔE up to 34.29), while Moringa tea caused the least discolouration (ΔE ≈ 30). The artificial saliva subgroups remained near baseline (ΔE<30). No statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) were observed between composite resin types, indicating that resin matrix hydrophilicity may play a more dominant role than filler morphology in staining susceptibility.

Conclusion: Herbal teas demonstrated a potential for staining composite restorative materials, with Tulsi tea showing the greatest discolouration effect. These findings highlight the importance of material selection and patient counselling regarding dietary habits to maintain the aesthetic longevity of dental restorations.

Keywords: Composite resins, Dental materials, Colour stability, Spectrophotometry, Dental Restoration, Permanent, Staining and discoloration, Herbal teas, Health education, Health Care, Global health, Knowledge

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i5.54294 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Composite resins have transformed restorative dentistry by offering superior aesthetics and functional durability [1]. Their ability to bond adhesively to tooth structures enables conservative cavity preparations and minimizes the risk of secondary caries. Additionally, composites can replicate the translucency and shade of natural dentition, making them ideal for anterior and posterior restorations [2]. However, maintaining their long-term colour stability remains a clinical challenge, as discolouration is a primary reason for restoration replacement. Discolouration of composites results from both intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Intrinsic changes involve oxidation of polymeric components, hydrolytic degradation of the filler-resin interface, and polymer aging due to thermal and enzymatic stress, leading to refractive index alterations and yellowing. Residual unreacted monomers can further oxidize over time, exacerbating internal discoloration [3, 4].

Extrinsic staining occurs via absorption or adsorption of chromogenic agents found in foods, beverages, and oral hygiene products. Surface roughness and porosity play crucial roles, with rougher surfaces retaining more pigments [5, 6]. Polishing protocols significantly influence this, as well; polished surfaces offer greater resistance to staining. Resin matrix hydrophilicity also contributes to water absorption, allowing deeper penetration of staining molecules. Composites with higher water sorption exhibit greater colour instability due to pigment diffusion through the water phase [7-9].

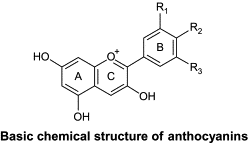

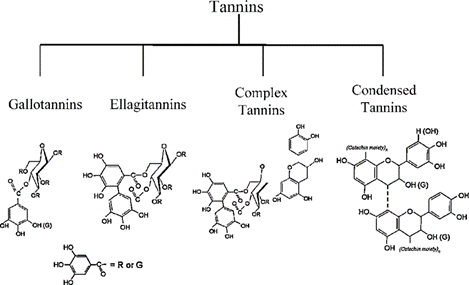

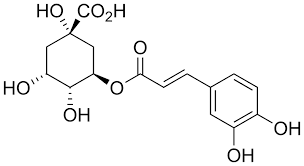

Studies have extensively evaluated the staining effects of coffee, black tea, red wine, and soft drinks, which are rich in chromogens like tannins and anthocyanins. These compounds interact with resins through hydrogen bonding and π-π interactions [10]. In contrast, the effects of herbal teas on composites remain underexplored, despite their growing popularity for health benefits. Herbal teas contain distinct bioactive compounds, hydrolysable tannins, flavonoids, anthocyanins, and chlorophylls that may interact differently with resin matrices [11].

Unlike black tea and red wine, which primarily contain condensed tannins and metal-polyphenol complexes, herbal teas have variable solubility profiles and chemical compositions. This biochemical distinction justifies the present investigation. The influence of herbal infusions, especially Tulsi, Amla, Hibiscus, and Moringa on composite resins warrants scientific attention given their increasing consumption in health-focused populations [12]. Contemporary composite technologies, such as nanohybrids and bulk-fills, offer improved optical and mechanical performance. Nanohybrids incorporate nanoscale and microscale fillers, enhancing polishability and reducing pigment adherence [14, 15]. Bulk-fill composites allow deep curing in a single increment due to advanced photoinitiators, but may be more prone to staining due to their higher resin content and larger filler particles. Sphere TEC-based composites use pre-polymerized spherical fillers for better handling and surface finish [16-19]. Despite these advancements, differences in filler systems may not overcome staining susceptibility if resin matrix composition remains hydrophilic. Herbal teas like Amla (Emblica officinalis), Hibiscus (Hibiscus sabdariffa), Moringa (Moringa oleifera), and Tulsi (Ocimum sanctum) contain plant-derived pigments and polyphenols capable of staining dental materials [20-23]. Their staining mechanisms may involve hydrogen bonding, van der Waals interactions, and complexation with polar resin groups [11, 24]. Fig. 1 illustrates key staining molecules.

(A) (B)

(C)

Fig. 1: Chemical structures of representative staining molecules such as (A) delphinidin (anthocyanin), (B) Tannic acid, and (C) Chlorogenic acid

This study evaluates the staining potential of these four herbal teas on three types of composites: nanohybrid, bulk-fill flowable, and nanohybrid with SphereTEC fillers. Spectrophotometric analysis will quantify ΔE over time, aiding clinical decisions on material selection and dietary counselling to maintain aesthetic restoration longevity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This in vitro study was conducted to evaluate the staining potential of four commercially available herbal teas, Amla (Emblica officinalis) (Caramel Organics), Hibiscus (Hibiscus sabdariffa) (Sitara Foods), Moringa (Moringa oleifera) (Saptamveda), and Tulsi (Ocimum sanctum) (Saptamveda) on the colour stability of three different composite materials. The composite materials used in this study were:

Group I – Nanohybrid composite resin (Beautifil II, Shofu Inc., Kyoto, Japan)

Group II – Bulk-fill flowable composite (SDR Flow+, Dentsply Sirona, USA)

Group III – Nanohybrid composite resin with SphereTEC fillers (TPH Spectra ST, Dentsply Sirona, USA)

These materials were specifically selected based on their differences in filler morphology, resin matrix composition, and degree of hydrophilicity, which are known to affect water sorption and staining susceptibility. Previous studies have shown that nanohybrid composite resins, due to their fine filler distribution, offer smoother surfaces and better polishability, potentially leading to reduced pigment retention [14]. Bulk-fill composite resins, in contrast, are designed for deeper polymerization but may be more prone to staining due to higher resin content and lower filler loading. SphereTEC-based materials utilize spherical pre-polymerized fillers that improve handling and aesthetics, yet limited literature exists on their resistance to staining agents. Hence, their inclusion allows a broader assessment of composite resin behaviour under exposure to herbal chromogens.

Sample preparation

A total of 150 disc-shaped composite samples were prepared, with 50 specimens per group. Each group was further divided into five subgroups (n=10), assigned to immersion in one of the four herbal teas or artificial saliva (control).

Samples were fabricated using a standardized Teflon mould of 10 mm diameter and 2 mm thickness. The composite resin material was incrementally packed into the mold, covered with a Mylar strip and a glass slide, and then light-cured.

The polymerization was performed using an LED curing unit (Elipar S10, 3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, USA), with a light intensity of 1200 mW/cm² measured using a radiometer, and a curing time of 20 seconds per sample. The curing tip was held perpendicular and in direct contact with the Mylar strip to ensure uniform polymerization. These parameters were selected in accordance with the manufacturers’ recommendations and validated in prior studies to minimize the presence of residual monomers, which can significantly increase the composite resin’s susceptibility to water sorption and staining [4, 14].

To eliminate inconsistencies arising from post-cure polymerization or early moisture absorption, all specimens were stored in artificial saliva at 37 °C for 24 h before baseline colour measurements were performed.

Preparation of herbal tea solutions

The herbal tea solutions were freshly prepared daily by steeping two tea bags (2 g each) of Amla, Hibiscus, Moringa, or Tulsi tea in 300 ml of boiling distilled water for 3 min, following standard infusion protocols for herbal beverages. After steeping, the tea bags were removed, and the solutions were allowed to cool to a standardized temperature of 37±1 °C, mimicking intraoral temperature during beverage consumption [35].

Each solution's pH was measured immediately after preparation using a calibrated digital pH meter (Eutech pH 700, Thermo Scientific). The mean pH values were as follows: Tulsi tea: 5.2±0.1, Hibiscus tea: 3.4±0.1, Amla tea: 3.8±0.1 and Moringa tea: 6.1±0.1.

These pH values indicate that most herbal teas tested were moderately to highly acidic, a factor known to contribute to resin matrix softening, water sorption, and increased pigment diffusion. Artificial saliva, used as the control solution, was prepared to simulate physiological salivary conditions and maintained at the same temperature (37±1 °C). All immersion solutions were replaced daily to maintain chemical stability and uniformity.

Immersion protocol

Each subgroup (n = 10 per composite resin type) was subjected to daily immersion for 15 min over a period of 60 consecutive days, representing an average herbal tea consumption pattern in clinical settings. The 15 min immersion duration was chosen to approximate cumulative exposure from drinking one to two cups of herbal tea per day, as supported by previous in vitro immersion studies simulating dietary staining habits [24].

To mimic intraoral dynamic fluid conditions and enhance the interaction between staining agents and the specimen surfaces, the tea solutions were gently agitated on an orbital shaker (IKA KS 130) at 60 rpm during immersion. This simulated mild oral movements, such as sipping and tongue contact, which can affect staining kinetics.

After each immersion cycle, the samples were rinsed with distilled water for 30 seconds, blotted dry with lint-free tissue, and then stored in fresh artificial saliva at 37 °C until the next immersion. This storage condition preserved the moisture content of the specimens and simulated intraoral hydration.

Colour measurement

Colour changes were assessed at three time points: baseline (prior to immersion), day 30, and day 60. A digital reflectance spectrophotometer (X-Rite i1PRO, X-Rite, USA) was used to measure colour variations based on the CIELAB system, which quantifies colour in three dimensions:

L* (lightness), a* (red-green spectrum), b* (yellow-blue spectrum)

The total colour change (ΔE*) was calculated using the formula:

ΔE = √(ΔL*)²+(Δa*)²+(Δb*)²

Where ΔL*, Δa*, and Δb* represent changes in the respective colour parameters from baseline to subsequent time points.

To enhance clinical applicability, colour differences were interpreted using well-established perceptibility thresholds:

ΔE>1.1: Considered perceptible under strict aesthetic dentistry standards, particularly in the anterior region.

ΔE>3.3: Recognized as visibly perceptible to the average human eye under normal viewing conditions.

Accordingly, all ΔE values reported in this study were evaluated against both thresholds to provide a dual perspective, aesthetic sensitivity and general clinical visibility.

Calibration of the spectrophotometer was performed prior to each session using the manufacturer-provided white calibration tile. Measurements were conducted under standardized D65 illumination conditions (daylight simulation at 6500 K), in accordance with CIE guidelines for consistent chromaticity.

Each specimen was positioned on a neutral grey background, and the same operator performed all measurements to eliminate inter-observer variability. The spectrophotometer probe was held perpendicular to the specimen surface, and three consecutive readings were taken at the centre of each disc, with the mean value recorded as the representative ΔE* for that time point. This protocol ensured measurement reproducibility and minimized angle-induced optical distortions.

Statistical analysis

The collected data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to assess significant differences in ΔE values among composite groups and immersion solutions. Post-hoc Tukey tests were used for pairwise comparisons to identify statistically significant differences between specific subgroups. A p-value<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

This statistical approach aimed to determine the extent to which herbal teas contributed to composite staining and whether significant differences existed between the composite materials tested.

RESULTS

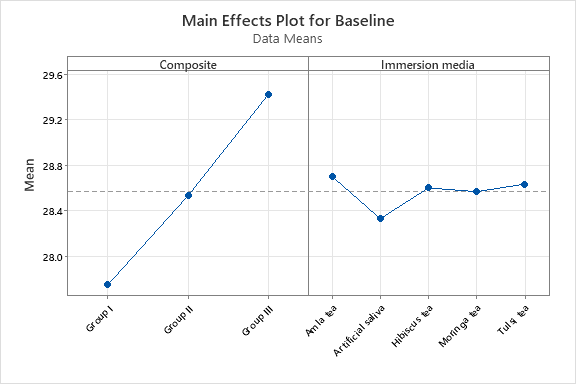

The intra-group comparison revealed that all three composite groups exhibited a progressive and statistically significant increase in ΔE values from baseline to day 60 across all immersion media, including the artificial saliva control group. As shown in table 1, the greatest colour changes were consistently observed in the Tulsi tea subgroups across all materials, followed by Hibiscus, Amla, and Moringa teas. Specimens stored in artificial saliva showed minimal discolouration (ΔE~28–30), remaining below thresholds of visual perceptibility.

Table 1: Intra-group comparison of the mean ΔE values at baseline, day 30, and day 60 for all composite materials across immersion media value are presented as mean±standard deviation (SD); n = 10 specimens per subgroup

| Composite | Immersion media | ΔE baseline (±SD) | ΔE 30th day (±SD) | ΔE 60th day (±SD) |

| Group I | Artificial saliva Amla tea Hibiscus tea Moringa tea Tulsi tea |

27.66±0.35 27.72±0.46 27.84±0.49 27.95±0.39 27.61±0.44 |

28.01±0.39 31.83±0.49 30.19±0.56 28.45±0.50 33.98±0.39 |

28.49±0.33 33.73±0.36 32.54±0.39 29.17±0.40 36.21±0.37 |

| Group II | Artificial saliva Amla tea Hibiscus tea Moringa tea Tulsi tea |

28.18±0.50 28.95±0.38 28.76±0.35 28.37±0.42 28.41±0.48 |

28.86±0.51 33.69±0.40 32.41±0.42 29.16±0.36 34.02±0.39 |

28.91±0.39 34.99±0.52 33.18±0.49 30.11±0.45 37.39±0.40 |

| Group III | Artificial saliva Amla tea Hibiscus tea Moringa tea Tulsi tea |

29.16±0.49 29.44±0.56 29.21±0.64 29.39±0.52 29.89±0.62 |

29.69±0.50 33.90±0.49 33.57±0.53 30.02±0.52 34.95±0.47 |

30.03±0.53 35.06±0.45 34.29±0.41 30.18±0.56 37.83±0.60 |

Interpretation and comparative analysis

Group I

In Group I, the specimens immersed in Tulsi tea demonstrated the greatest colour change (ΔE = 36.21±0.37 at 60 d), while the Moringa tea group exhibited the least colour change (ΔE = 29.17±0.40 at 60 d). The control group (artificial saliva) showed minimal discolouration over 60 d (ΔE = 28.49±0.33 at 60 d)

Group II

Similar trends were observed in Group II, where the Tulsi tea subgroup exhibited the highest ΔE value (ΔE = 37.39±0.40 at 60 d), while Moringa tea caused the least staining (ΔE = 30.11±0.45). The artificial saliva control group showed relatively minor colour changes (ΔE = 28.91±0.39).

Group III

In Group III, Tulsi tea again caused the highest staining (ΔE = 37.83±0.60 at 60 d), followed by Hibiscus and Amla teas. The artificial saliva control group showed the lowest ΔE values (ΔE = 30.03±0.53 at 60 d).

Statistical analysis using one-way ANOVA and post-hoc Tukey’s test showed that the type of herbal tea had a significant effect on ΔE values (p<0.05), while the differences between the three composite materials were not statistically significant (p>0.05). This finding suggests that all three resin types were equally susceptible to staining, despite their differences in filler type, size, and loading.

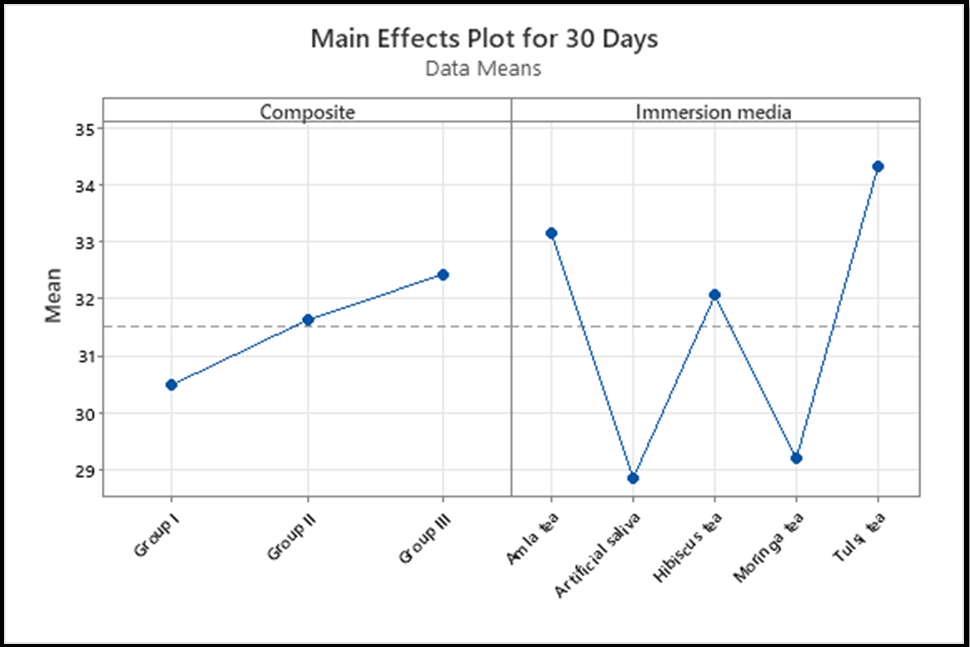

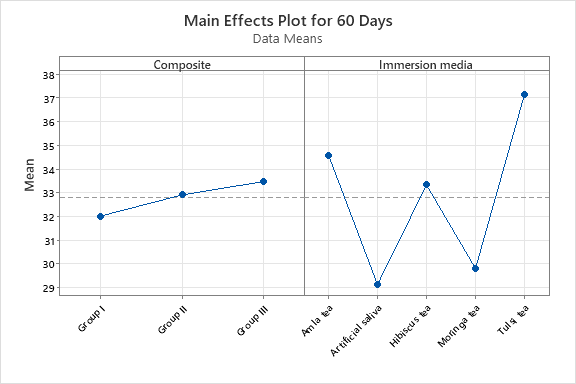

As illustrated in fig. 2, 3, and 4, the main effects plot shows a consistent increase in ΔE values over time across all materials, with Tulsi tea demonstrating the steepest trajectory by day 60. Moringa tea maintained the flattest ΔE progression in all composite groups.

The absence of significant inter-group differences, despite varied filler systems, highlights the dominant role of the resin matrix in staining susceptibility. This may be attributed to the hydrophilicity of the methacrylate-based matrices used in all three composite resins, which facilitate water sorption and pigment diffusion. Water sorption creates micro-channels within the polymer network, enabling tannins, polyphenols, and anthocyanins to infiltrate and bind to the organic matrix.

Although all specimens were finished against a Mylar strip to standardize surface texture, surface roughness measurements (e.g., using SEM or AFM) were not conducted in this study. Such data could have helped correlate surface topography with pigment retention. The lack of statistically significant differences despite the advanced SphereTEC filler architecture may be partially explained by the overriding influence of resin chemistry and possibly subtle surface irregularities that were not quantified.

Fig. 2: Main effects plot graph at baseline showing uniformity across composite types prior to staining

Fig. 3: Main effects plot at 30 d showing progressive increase in ΔE for all tea subgroups, especially Tulsi

Fig. 4: Main effects plot at 60 d showing steep ΔE rise for Tulsi tea across all composite groups

DISCUSSION

The findings of this study provide strong evidence that herbal teas, particularly Tulsi (Ocimum sanctum), significantly impact the colour stability of composite resins over time. Discolouration remains a significant concern in restorative dentistry, particularly for anterior restorations where aesthetics is paramount. The staining behaviour observed in this study emphasizes the influence of chromogenic compounds found in herbal teas and their interactions with composite resin materials.

Composite resin discolouration is attributed to both intrinsic and extrinsic factors. In this study, extrinsic staining caused by herbal teas resulted in notable colour changes across all tested materials. The primary staining agents in herbal teas are polyphenols, tannins, and anthocyanins, which can penetrate the resin matrix through surface irregularities or hydrophilic pathways within the material [25, 26]. Tulsi tea, which exhibited the highest staining potential, is particularly rich in tannins. Tannins are polyphenolic compounds known for their strong affinity for proteins and biomaterials, including dental resins. Their ability to interact with and integrate into the resin matrix through water sorption pathways leads to persistent staining over time [23].

The CIELAB colour system used in this study is well-suited for detecting even subtle changes in colour, as it closely aligns with human visual perception [26]. Spectrophotometric analysis demonstrated a significant increase in ΔE values, reinforcing the cumulative staining effect of prolonged herbal tea exposure [10]. These results align with previous studies showing that beverages such as coffee and black tea cause similar degrees of staining. In fact, studies on black tea, coffee, and red wine report ΔE values ranging between 20 and 35, depending on duration and resin type [24]. Interestingly, the ΔE values for Tulsi tea (≥37) in this study exceeded the reported values for black tea in many previous studies, underscoring its high staining potential.

The three composite resin materials evaluated Beautifil II (nanohybrid composite), SDR Flow+(bulk-fill flowable composite), and TPH Spectra ST (nanohybrid composite with SphereTEC fillers) are commonly used in restorative dentistry due to their mechanical and aesthetic advantages. Despite differences in filler composition and resin matrix, all three materials exhibited similar susceptibility to staining. This finding suggests that, in this context, resin matrix composition and surface properties play a more dominant role in staining resistance than filler type alone.

Beautifil II (Group I), a nanohybrid composite resin, contains filler particles ranging from 0.4 to 1 μm and includes glass fillers with a polyacid-modified resin [13]. While nanohybrid composites are known for their smooth finish and excellent polishability, the staining observed in this study suggests that the resin matrix’s hydrophilic nature may have contributed to the absorption of chromogenic agents [8, 27]. Previous research has shown that composites with higher water sorption rates tend to exhibit greater colour instability due to their ability to act as a medium for pigment diffusion [28].

SDR Flow+(Group II) is a bulk-fill composite resin designed for deeper polymerization in a single increment, facilitated by enhanced photoinitiators [18]. Bulk-fill composite resins often incorporate larger filler particles, which could theoretically provide some resistance to staining by limiting the resin matrix’s direct exposure to chromogenic compounds [29]. However, the results indicate that the filler size in SDR Flow+did not offer substantial protection against staining. This suggests that the resin matrix composition is the primary determinant of staining susceptibility rather than filler morphology alone.

TPH Spectra ST (Group III) incorporates SphereTEC technology, which consists of spherically pre-polymerized fillers designed to improve handling and polishability. Despite these characteristics, this material also exhibited significant staining, further emphasizing the crucial role of resin composition in colour stability. The presence of advanced filler technology did not significantly reduce the staining effect, suggesting that composite resins require additional modifications, such as hydrophobic coatings, to improve their resistance to external staining agents [25, 30].

Among the herbal teas tested, Tulsi tea exhibited the most pronounced staining, followed by Hibiscus and Amla teas. The high tannin content in Tulsi tea likely contributed to its strong discolouration effect [31, 33]. Tannins have been extensively studied for their ability to form insoluble complexes with proteins and polymers, which can lead to visible staining over time. Similarly, Hibiscus tea, which is rich in anthocyanins and flavonoids, caused considerable staining, reinforcing prior research that highlights the strong pigmentation potential of anthocyanin-rich beverages [21, 32].

Interestingly, while Hibiscus tea is intensely coloured due to its anthocyanin content, its ΔE values were lower than Tulsi in this study. This could be attributed to differences in molecular weight, solubility, or diffusion characteristics of the pigments. Anthocyanins though strongly pigmented, may exhibit lower resin affinity compared to polyphenols or may be more easily washed off [34]. This contrast with prior assumptions highlights an unexpected trend, prompting further investigation.

Amla tea, despite containing notable amounts of tannins and polyphenols, exhibited comparatively lower staining than Tulsi and Hibiscus teas. This may be due to the structural variation of polyphenolic compounds or reduced binding affinity for the composite resin matrix [22]. Moringa tea, on the other hand, caused the least staining, suggesting that its lower concentration of chromophores and polyphenols, or the steric hindrance of chlorophyll molecules, may limit its staining ability. This finding may be of practical importance for patients desiring aesthetic preservation with herbal tea intake [35].

The findings of this study have significant clinical implications. Dentists should be aware of the staining potential of herbal teas, particularly for patients with anterior composite restorations. Patients who frequently consume Tulsi or Hibiscus tea should be advised about the potential for increased staining and may benefit from dietary modifications, such as using a straw or rinsing with water immediately after consumption. Additionally, preventive strategies such as regular polishing of restoration surfaces and the application of surface sealants or resin-based coatings could help minimize pigment adherence [36, 37].

Material selection also plays a pivotal role in preventing aesthetic deterioration. Although all composites in this study performed similarly, future formulations that incorporate hydrophobic monomers (e.g., UDMA, silorane-based systems) could enhance resistance to pigment infiltration. Studies have demonstrated that such systems exhibit lower water sorption and improved resistance to chromogenic agents [39, 40].

It is also important to consider that this study was conducted under in vitro conditions, and staining behaviours may differ in vivo. In the oral cavity, the formation of a salivary pellicle on composite resin surfaces can act as a protective barrier, modulating direct pigment interaction and possibly reducing discolouration [41]. Furthermore, salivary flow, enzymatic activity, pH buffering, and mechanical abrasion from oral hygiene practices all influence the extent and nature of staining in clinical scenarios. Therefore, while in vitro conditions allow controlled observation of staining patterns, the results should be interpreted with the understanding that in vivo exposure may alter the rate and intensity of composite resin discolouration.

Future research should explore the long-term effects of herbal tea consumption on composite resin restorations in vivo, accounting for the influence of salivary components, pellicle formation, and oral hygiene variables. Advanced analytical techniques such as Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), Raman spectroscopy, or X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) can help investigate the molecular interactions between chromogens and the resin matrix, elucidating mechanisms of pigment adhesion and penetration. Additionally, coating technologies, bioactive nanocomposites, or plasma-modified surfaces may offer innovative pathways for developing more stain-resistant composite resin materials [40].

Future research directions

To build upon the findings of this in vitro study and enhance their clinical relevance, future research should be directed toward comprehensive in vivo investigations. Longitudinal clinical trials are essential to assess the staining behaviour of composite resin restorations in the oral environment, considering factors such as salivary pellicle formation, pH fluctuations, mechanical wear from brushing and mastication, and enzymatic interactions that influence pigment adherence and penetration. Additionally, research into advanced surface coating technologies such as bioactive sealants, plasma-treated surfaces, and nanocomposite layers may contribute to the development of restorative materials with superior stain resistance without compromising aesthetic or mechanical properties. A focus on hydrophobic composite resin formulations, incorporating monomers like UDMA, silorane, or other low-sorption resin matrices, could further reduce water uptake and pigment infiltration, ultimately enhancing the long-term aesthetic performance of restorations. Moreover, the application of molecular-level analytical techniques, including Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), Raman spectroscopy, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), and scanning electron microscopy (SEM), will provide valuable insights into the chemical and surface interactions responsible for discolouration. These advanced characterizations can support the development of next-generation stain-resistant composite materials grounded in mechanistic understanding.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, this study confirms that herbal teas, particularly Tulsi tea, exhibit a significant staining effect on composite resin materials. Hibiscus and Amla teas also contribute to discolouration, though to a lesser extent, while Moringa tea demonstrated the lowest staining potential. No statistically significant difference in staining susceptibility was observed among the three composite materials tested, nanohybrid composite resin, bulk-fill flowable composite, and nanohybrid composite resin with SphereTEC fillers, suggesting that resin matrix composition and hydrophilicity have a more dominant influence on colour stability than filler type alone. These findings reinforce the importance of patient education regarding the aesthetic implications of dietary choices, especially for those with anterior composite restorations. Clinicians should consider preventive strategies, such as regular polishing, use of surface sealants, and advising moderation in consumption of chromogen-rich herbal teas like Tulsi.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization, G. S., V. S.; methodology, G. S., V. S.; software, V. S.; validation, G. S., V. S.; formal analysis, G. S., V. S., M. H. Z.; investigation, G. S., V. S., M. H. Z.; resources, V. S.; data curation, G. S, V. S.; writing-original draft preparation, G. S., V. S.; writing-review and editing, G. S., V. S., M. H. Z.; visualization, V. S.; supervision, G. S., V. S.; project administration, G. S., V. S.; funding acquisition, G. S., V. S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Demarco FF, Correa MB, Cenci MS, Moraes RR, Opdam NJ. Longevity of posterior composite restorations: not only a matter of materials. Dent Mater. 2012;28(1):87-101. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2011.09.003, PMID 22192253.

Assaf C, Abou Samra P, Nahas P. Discoloration of resin composites induced by coffee and tomato sauce and subjected to surface polishing: an in vitro study. Med Sci Monit Basic Res. 2020;26:e923279. doi: 10.12659/MSMBR.923279, PMID 32536683.

Samra AP, Pereira SK, Delgado LC, Borges CP. Color stability evaluation of aesthetic restorative materials. Braz Oral Res. 2008;22(3):205-10. doi: 10.1590/s1806-83242008000300003, PMID 18949304.

Chandrasekhar V, Reddy LP, Prakash TJ, Rao GA, Pradeep M. Spectrophotometric and colorimetric evaluation of staining of the light-cured composite after exposure with different intensities of light-curing units. J Conserv Dent. 2011;14(4):391-4. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.87208, PMID 22144810.

Gupta G, Gupta T. Evaluation of the effect of various beverages and food material on the color stability of provisional materials an in vitro study. J Conserv Dent. 2011;14(3):287-92. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.85818, PMID 22025835.

Guler AU, Yilmaz F, Kulunk T, Guler E, Kurt S. Effects of different drinks on stainability of resin composite provisional restorative materials. J Prosthet Dent. 2005;94(2):118-24. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2005.05.004, PMID 16046965.

Reddy PS, Tejaswi KL, Shetty S. Surface roughness of nanofilled composite after polishing with one-step and multi-step systems: an in vitro study. J Conserv Dent. 2014;17(5):430-3.

Fontes ST, Fernandez MR, De Moura CM, Meireles SS. Color stability of a nanofill composite: effect of different immersion media. J Appl Oral Sci. 2009;17(5):388-91. doi: 10.1590/s1678-77572009000500007, PMID 19936513.

Khamverdi Z, Kasraei S, Rezaei Soufi L, Azarsina M. Comparison of colour stability of two resin-based composites in tea, coffee and chlorhexidine mouthwash. Dent Res J (Isfahan). 2013;10(4):525-31.

Mutlu Sagesen L, Ergun G, Ozkan Y, Semiz M. Color stability of a dental composite after immersion in various media. Dent Mater J. 2005;24(3):382-90. doi: 10.4012/dmj.24.382, PMID 16279728.

Dumitrescu R, Anghel IM, Opris C, Vlase T, Vlase G, Jumanca D. Investigating the effect of staining beverages on the structural and mechanical integrity of dental composites using Raman Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy and microhardness analysis. Medicina (Kaunas). 2025 Mar 25;61(4):590. doi: 10.3390/medicina61040590, PMID 40282881.

Nonaka GI, Sakai R, Nishioka I. Hydrolysable tannins and proanthocyanidins from green tea. Phytochemistry. 1984 Jan 1;23(8):1753-5. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)83484-6.

Itanto BS, Usman M, Margono A. Comparison of surface roughness of nanofilled and nanohybrid composite resins after polishing with a multi-step technique. J Phys Conf Ser. 2017;884(1):12059. doi: 10.1088/1742-6596/884/1/012091.

Senawongse P, Pongprueksa P. Surface roughness of nanofill and nanohybrid resin composites after polishing and brushing. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2007;19(5):265-73. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8240.2007.00116.x, PMID 17877626.

El Damanhoury H, Platt J. Polymerization shrinkage stress kinetics and related properties of bulk fill resin composites. Oper Dent. 2014;39(4):374-82. doi: 10.2341/13-017-L, PMID 23865582.

Kim EH, Jung KH, Son SA, Hur B, Kwon YH, Park JK. Effect of resin thickness on the microhardness and optical properties of bulk fill resin composites. Restor Dent Endod. 2015;40(2):128-35. doi: 10.5395/rde.2015.40.2.128, PMID 25984474.

Nasim I, Neelakantan P, Sujeer R, Subbarao CV. Color stability of microfilled microhybrid and nanocomposite resins an in vitro study. J Dent. 2010;38 Suppl 2:e137-42. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2010.05.020, PMID 20553993.

Schneider LF, Cavalcante LM, Silikas N. Shrinkage stresses generated during resin composite applications: a review. J Dent Biomech. 2010;2010:131630. doi: 10.4061/2010/131630, PMID 20948573.

Ferracane JL. Resin composite state of the art. Dent Mater. 2011;27(1):29-38. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2010.10.020, PMID 21093034.

Yokozawa T, Kim HY, Kim HJ, Okubo T, Chu DC, Juneja LR. Amla (Emblica officinalis Gaertn.) prevents dyslipidaemia and oxidative stress in the ageing process. Br J Nutr. 2007;97(6):1187-95. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507691971, PMID 17506915.

McKay DL, Chen CY, Saltzman E, Blumberg JB. Hibiscus sabdariffa L. tea (tisane) lowers blood pressure in prehypertensive and mildly hypertensive adults. J Nutr. 2010;140(2):298-303. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.115097, PMID 20018807.

Aslam M, FA, RN, UR, TG, MN. Mineral composition of Moringa oleifera leaves and pods from different regions of Punjab, Pakistan. Asian J Plant Sci. 2005;4(4):417-21. doi: 10.3923/ajps.2005.417.421.

Singh N, Hoette Y, Tulsi MR. The mother medicine of nature. 2nd ed. Lucknow: International Institute of Herbal Medicine; 2010.

Catelan A, Briso AL, Sundfeld RH, Goiato MC, Dos Santos PH. Color stability of sealed composite resin restorative materials after ultraviolet artificial aging and immersion in staining solutions. J Prosthet Dent. 2011;105(4):236-41. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(11)60038-3, PMID 21458648.

Paravina RD, Roeder L, Lu H, Vogel K, Powers JM. Effect of finishing and polishing procedures on surface roughness, gloss and color of resin-based composites. Am J Dent. 2004;17(4):262-6. PMID 15478488.

Villalta P, Lu H, Okte Z, Garcia Godoy F, Powers JM. Effects of staining and bleaching on color change of dental composite resins. J Prosthet Dent. 2006;95(2):137-42. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2005.11.019, PMID 16473088.

Sideridou ID, Karabela MM, Vouvoudi ECH. Physical properties of current dental nanohybrid and nanofill light-cured resin composites. Dent Mater. 2011;27(6):598-607. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2011.02.015, PMID 21477852.

Dietschi D, Campanile G, Holz J, Meyer JM. Comparison of the color stability of ten new generation composites: an in vitro study. Dent Mater. 1994;10(6):353-62. doi: 10.1016/0109-5641(94)90059-0, PMID 7498599.

Yokoyama R, Inoue G, Ono T. Spectrophotometric evaluation of surface staining induced by coffee and tea on resin-based composites after surface treatments. Dent Mater J. 2014;33(6):720-8.

Wang R, Bai Y, Lu L. The three-body wear of nanofilled dental composite resin. J Biomed Mater Res B. 2012;100(4):1024-9.

Kaur C, Kapoor HC. Antioxidants in fruits and vegetables: the millennium’s health. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2001;36(7):703-25.

Telang A, Narayana IH, Madhu KS, Kalasaiah D, Ramesh P, Nagaraja S. Effect of staining and bleaching on color stability and surface roughness of three resin composites: an in vitro study. Contemp Clin Dent. 2018;9(3):452-6. doi: 10.4103/ccd.ccd_297_18, PMID 30166843.

Feroz M, Syed SB, Mohan D, Ramanan RM. Herbal formulation of green tea and tulsi ameliorates hepatic damage in albino rats. Biomed Aging Pathol. 2012;2(3):129-35.

Miletic V, Stasic JN, Komlenic V, Petrovic R. Multifactorial analysis of optical properties sorption and solubility of sculptable universal composites for enamel layering upon staining in colored beverages. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2021 Sep;33(6):943-52. doi: 10.1111/jerd.12679, PMID 33179862.

Usha G, Kumar MV, Arathi R. A comparative study to assess staining potential of six different herbal teas on anterior restorative materials: an in vitro study. J Conserv Dent. 2019;22(2):143-50.

Narkedamalli RK, Muliya VS, Pentapati KC. Staining ability of herbal tea preparations on a nano-filled composite restorative material an in vitro study. 2022;11:1376. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.128029.2, PMID 37638138.

Wang L, Garcia FC, Amarante de Araujo PA, Franco EB, Mondelli RF. Wear resistance of packable resin composites after simulated toothbrushing test. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2004;16(5):303-14. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8240.2004.tb00058.x, PMID 15726799.

Reis AF, Giannini M, Lovadino JR, dos Santos Dias CT. The effect of six polishing systems on the surface roughness of two-packable resin-based composites. Am J Dent. 2002;15(3):193-7. PMID 12469758.

Soares Geraldo D, Scaramucci T, Steagall Jr W, Braga SR, Sobral MA. Interaction between staining and degradation of a composite resin in contact with colored foods. Braz Oral Res. 2011;25(4):369-75. doi: 10.1590/s1806-83242011000400015, PMID 21860925.

Mutlu Sagesen L, Ergun G, Ozkan Y, Semiz M. Surface roughness and colour changes of different composite resins after immersion in tea and cola. J Dent Fac Ataturk Univ. 2017;27:10-9.

Lee YK, Powers JM. Influence of salivary organic substances on the discoloration of esthetic dental materials a review. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2006 Feb;76(2):397-402. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30380, PMID 16258957.