Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 4, 2025, 387-394Original Article

COMPUTATIONAL DRUG DESIGN AND MOLECULAR DYNAMICS OF PHENYL BENZAMIDE DERIVATIVES AS PARP-1 INHIBITORS FOR BREAST CANCER THERAPY

PULLA PRUDVI RAJ1, DIVYA JYOTHI PALATI2, PRAVEEN T. K.3, GOWRAMMA B.1*

1,4Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, JSS College of Pharmacy, JSS Academy of Higher Education and Research, Ooty, Nilgiris, Tamil Nadu, India. 2Department of Pharmacognosy, JSS College of Pharmacy, JSS Academy of Higher Education and Research, Ooty, Nilgiris, Tamil Nadu, India. 3Department of Pharmacology, JSS College of Pharmacy, JSS Academy of Higher Education and Research, Ooty, Nilgiris, Tamil Nadu, India

*Corresponding author: Gowramma B.; *Email: gowrammb@rediffmail.com

Received: 23 Mar 2025, Revised and Accepted: 07 May 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP1) plays a vital role in Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA) repair and cell survival. Given its importance in cancer progression, PARP1 inhibitors are promising therapeutic agents. This study aims to design and evaluate 3-((3,4-dihydroisoquinolin-2(1H)-yl) sulfonyl)-N-phenyl benzamide derivatives as potential PARP1 inhibitors using computational approaches.

Methods: Molecular docking was performed to assess the binding affinity of the designed compounds with PARP1. Molecular Mechanics-Generalized Born Surface Area (MM-GBSA) calculations were used to validate binding free energy and stability. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations analyzed complex stability over time.

Results: Docking analysis showed that compound 2D had a Glide score of-6.53 kcal/mol, comparable to Olaparib (-6.46 kcal/mol). Key interactions with Tyr896, Arg878, Asp766, and Ser904 contributed to its stability. MD simulations confirmed minimal Root mean Square Deviation (RMSD) (1.2 to 2.7 Å) and Root mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) (0.5 to 0.9 Å) fluctuations, indicating strong binding stability. Binding free energy analysis showed that compound 2D (-87.20 kcal/mol) exhibited a binding affinity close to the standard drug (Olaparib) (-88.81 kcal/mol).

Conclusion: Compound 2D demonstrated strong and stable interactions with PARP1, comparable or superior to Olaparib. These findings suggest that compound 2D is a promising lead candidate for PARP1-targeted therapy, warranting further preclinical and biological validation.

Keywords: PARP1 inhibitors, Molecular docking, MM-GBSA, Molecular dynamics, ADMET, Breast cancer, Drug discovery

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i4.54313 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP1) is an essential enzyme involved in various physiological processes, including DNA repair, transcription regulation, cell proliferation, and apoptosis. Given its elevated expression in multiple cancers—such as ovarian, breast, skin, colorectal, and lung cancer—PARP1 has emerged as a significant therapeutic target [1-7]. DNA damage activates PARP1, facilitating the recruitment of repair proteins to restore single-strand DNA breaks. The enzyme comprises two primary functional domains: the N-terminal DNA-binding domain (DBD) and the C-terminal catalytic domain (CAT), which play crucial roles in DNA repair [8, 9]. The ADP-ribosyl transferase (ART) subdomain within the catalytic domain is responsible for Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide NAD+binding, with key residues such as glutamic acid, tyrosine, and histidine contributing to enzymatic activity [10-12]. The primary mechanism of action of PARP1 inhibitors (PARP1) involves binding to the NAD+recognition site of PARP1, thereby blocking its enzymatic function. This inhibition leads to DNA repair failure, accumulation of DNA damage, and, ultimately, cancer cell death [13-16]. The first-generation PARP1 inhibitors were designed to exploit this mechanism, particularly for cancers harbouring Breast Cancer gene BRCA1/2 mutations, such as ovarian and breast cancer [17]. According to clinicaltrials. gov, over 88 clinical trials have been completed, and multiple PARP1 inhibitors have been approved for treating BRCA-mutated ovarian, breast, and prostate cancers. Additionally, ongoing trials are investigating PARP1 in chemo-resistant tumours and other genetic alterations affecting DNA repair mechanisms [18, 19]. Clinical studies have demonstrated the therapeutic efficacy of PARP1 in breast and ovarian cancer treatment [20, 21]. However, challenges such as low specificity, weak binding affinity, and adverse side effects limit their clinical application [22]. The search for novel drug-like molecules with distinct binding mechanisms, improved selectivity, and enhanced potency remains a crucial aspect of current research. Several Food and Drug Administration (FDA) FDA-approved PARP1 inhibitors, including Olaparib (Lynparza, AstraZeneca), Rucaparib (Rubraca, Clovis Oncology), Niraparib (Zejula, Tesaro), and Talazoparib (Talzenna, Pfizer), have demonstrated efficacy in cancer therapy. Olaparib was the first PARP1 approved by the FDA and European Medicines Agency (EMA) for BRCA-mutated ovarian cancer, including maintenance therapy for primary peritoneal and fallopian tube cancers [23, 24]. Talazoparib, approved in 2018, is used for HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer with BRCA1/2 mutations [25]. Several nonselective PARP1 inhibitors—such as veliparib [26] and fluzoparib [27]-are also under investigation, demonstrating equal potency against PARP2. Beyond catalytic inhibition, PARP trapping has emerged as a crucial mechanism in clinical settings. Talazoparib, in particular, is 100 times more effective than Olaparib in trapping PARP1 at DNA damage sites, leading to cancer cell death [28]. This mechanism prevents DNA replication and transcription fork activity, resulting in increased cytotoxicity. Given these insights, the present study employs computational approaches to identify novel drug-like chemical scaffolds as potential substitutes for existing PARP1 inhibitors, particularly Talazoparib. A combination of ligand-based and structure-based methods was utilized to predict binding positions and molecular similarity, aiming to discover new, potent, and selective PARP1 inhibitors. By targeting PARP1 trapping and enzymatic inhibition, this research seeks to expand therapeutic options for cancer treatment [29].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of ligands

The structures of twelve different ligands were processed using the LigPrep module in the Maestro molecular modeling software, utilizing the Optimized Potentials for Liquid Simulations, version 3 (OPLS3) force field. Determining the appropriate protonation states of molecules under physiological conditions can be complex. To address this, the Epik module in the Maestro suite was employed to accurately predict the protonation states of strained molecules based on text-mining analyses. Additionally, this module generated stereoisomers of the compounds at neutral pH. Understanding the protonation states of these molecules provides valuable insights into their interactions with proteins and other small molecules within biological systems.

Protein preparation

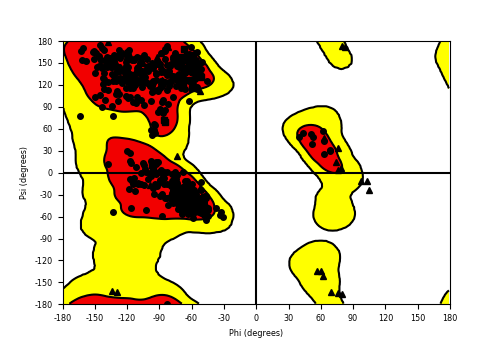

Protein structure information was obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). The selected target consists of 355 residues, and we utilized the structure with PDB ID: 4ZZZ. Using the default settings, the entire structure was pre-processed with Maestro’s Protein Preparation module. Missing loops, atoms, and side chains in the backbone were reconstructed using the Prime module in Maestro. The Ramachandran plot analysis indicated that 99% of the residues fall within the allowed regions [30] (fig. 1). Additionally, molecular modeling was performed to simulate the influence of water molecules on the catalytic domain.

Fig. 1: Ramachandran plot has 99% of residues in the permitted area

Molecular docking

Molecular docking was conducted using the Schrödinger Suite 2020-21, specifically the Glide module in the Extra Precision (XP) mode, to predict ligand interactions within the allosteric site of the target protein. The selected molecules, along with the PARP1 substrate, were docked using Glide to generate poses with high docking scores. Glide’s scoring function evaluates retrieved conformations to assign docking scores [31]. For each molecule, ten bioactive conformers were generated by placing sequences within the allosteric sites of ten co-crystallized molecules. Docking simulations were carried out using the XP Visualizer in the Maestro molecular modeling suite, a grid-based docking program, to identify optimal binding poses in the PARP1 allosteric site. Genetic algorithms and docking algorithms were utilized to refine and select the most suitable conformations based on top docking scores. The selected target protein (PDB ID: 4ZZZ) and the identified molecules were used as inputs for molecular docking. The XP Visualizer [32] was employed to analyze docking outcomes. Docking simulations were conducted using the Glide module, with the XP mode applied throughout. The target enzyme molecules were set with a scaling factor of 0.8 and a partial atomic charge threshold of 0.15. The best-docked complex was determined based on Glide docking scores, and the interactions of these docked configurations were further analyzed using the XP Visualizer [33].

Molecular dynamics

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were performed using the Desmond module in Schrödinger. The simulations employed the simple point-charge (SPC) explicit water model, ensuring a minimum spacing of 10 Å between the protein surface and the solvent boundary. An orthorhombic simulation box was constructed to encapsulate the system. Protein-ligand docked complexes were solvated using the orthorhombic SPC water model [34]. The solvated system was neutralized with counter ions, maintaining a physiological salt concentration of 0.15 M. The OPLS3 force field [35] was applied to describe the receptor-ligand complex. The MD simulation was conducted using the NPT ensemble (Isothermal-Isobaric ensemble), which maintains constant pressure, temperature, and particle number [36]. The simulation was executed for 100 ns under a temperature of 300 K and an atmospheric pressure of 1.013 bar, with relaxation parameters set accordingly. The system, comprising 49,339 atoms and 14,079 water molecules, was subjected to MD simulation for 100 ns. To assess the stability of the complex during the simulation, the protein backbone structures were aligned with the initial frame's backbone. The simulated interaction trajectory was analyzed by incorporating the _out. selecting Root mean Square Deviation (RMSD) and Root mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) for evaluation. RMSD and RMSF plots were generated to illustrate the system’s stability over the simulation period.

RESULTS

Molecular docking results and analysis

Docking studies were performed using the crystal structure of Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP1) (PDB ID: 4ZZZ) with Schrödinger Suite 2021-4. The virtual screening approach ensured that ligand conformations maintained a root mean square deviation (RMSD) of 1.5 Å relative to the co-crystallized structure. To eliminate functional groups that could negatively impact ligand interactions, Lipinski's rule of five was applied. Several Glide XP-docking parameters, including the Glide score, e-model, van der Waals energy (E_vdw), Coulomb energy (E_coul), and overall docking energy (Energy), were considered to evaluate the screening results.

Docking analysis demonstrated that all compounds exhibited favorable binding activity, with some showing superior activity compared to Olaparib. Notably, compounds 2D, 2K, and 2M achieved the highest Glide scores of -6.53 kcal/mol,-5.94 kcal/mol, and -5.93 kcal/mol, respectively, indicating strong binding affinity. Although compounds 2O and 2N had slightly lower Glide scores of -5.85 kcal/mol and -5.68 kcal/mol than 2D, 2K, and 2M, they still exhibited significant binding potential.

Conversely, weaker binding interactions were observed for compounds 2G and 2I, with Glide scores of -4.00 kcal/mol and-3.16 kcal/mol, respectively. The standard drug Olaparib displayed a Glide score of -6.46 kcal/mol, representing the highest binding affinity among all tested compounds. Among them, 2D exhibited particularly strong interaction parameters, including a van der Waals energy (E_vdw) of-49.48 kcal/mol, Coulomb energy (E_coul) of-2.59 kcal/mol, total docking energy (E_energy) of-52.07 kcal/mol, and an e-model (Gemodel) score of-82.44 kcal/mol. These results highlight 2D as the most promising compound, demonstrating a binding affinity comparable to or even superior to Olaparib, making it a strong candidate for further studies targeting PARP1.

Table 1: The XP-docking scores for compounds in PARP 1 catalytic pocket (PDB ID: 4ZZZ)

| S. No. | Comp | Gscore | Gvedw | Gecou | Genergy | Gemodel |

| 1. | 2A | -5.18796 | -46.2358 | -10.4985 | -56.7343 | -92.2944 |

| 2. | 2C | -5.45184 | -43.6474 | -5.59104 | -49.2384 | -74.6452 |

| 3 | 2D | -6.531 | -49.4885 | -2.59052 | -52.0791 | -82.4477 |

| 3. | 2I | -3.1625 | -43.173 | -9.7942 | -52.9672 | -78.0674 |

| 4. | 2F | -4.61917 | -47.1043 | -10.344 | -57.4483 | -86.3811 |

| 5. | 2G | -4.00013 | -61.958 | 0.760757 | -61.1973 | -90.8688 |

| 7. | 2K | -5.94962 | -42.2908 | -5.57731 | -47.8681 | -76.8953 |

| 8. | 2L | -5.13339 | -49.3747 | -8.80726 | -58.182 | -92.4896 |

| 9. | 2M | -5.9351 | -44.9449 | -4.75337 | -49.6982 | -73.7303 |

| 10. | 2N | -5.6814 | -43.529 | -10.3043 | -53.8333 | -84.484 |

| 11. | 2O | -5.85882 | -58.6131 | -1.59525 | -60.2084 | -92.9172 |

| 12. | 2T | -4.87412 | -51.0727 | -6.08821 | -57.1609 | -82.7953 |

| Standard | Olaparib | -6.46344 | -58.3568 | -9.24811 | -67.6049 | -121.306 |

aGlide Score, bGlide E-model, cGlide Van der Waals Energy, dGlide Coulomb Energy, eGlide Energy.

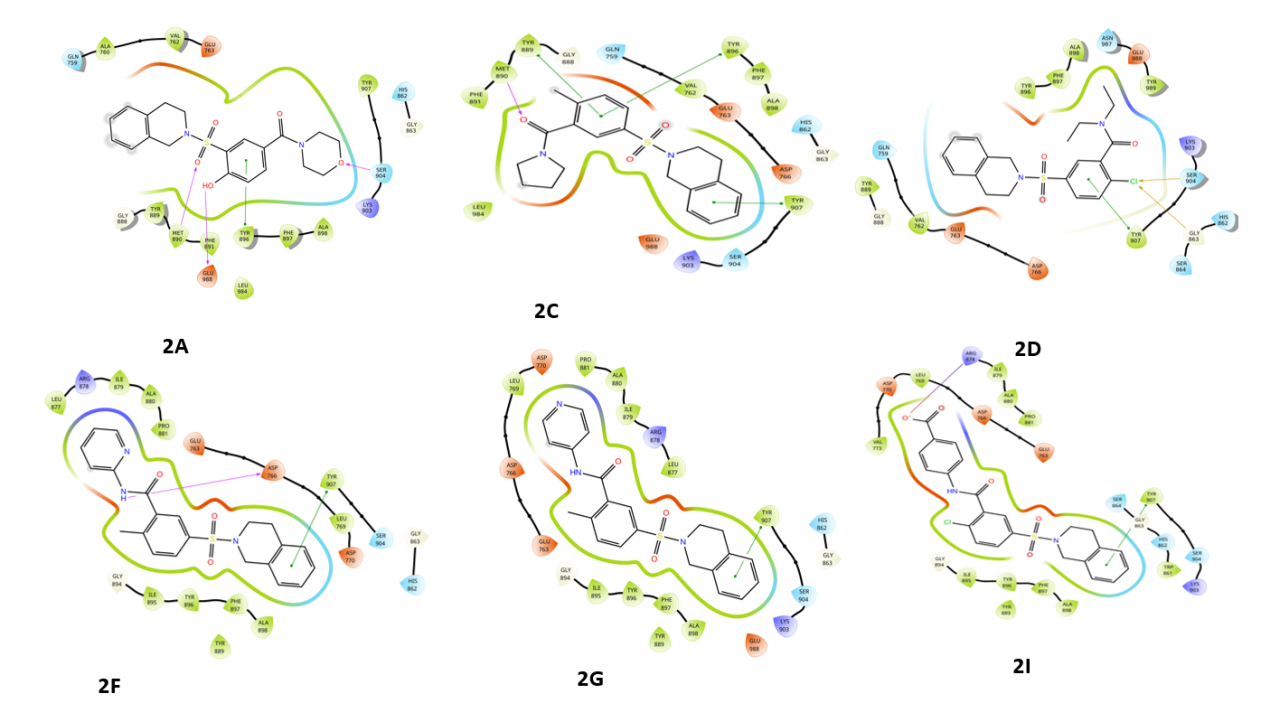

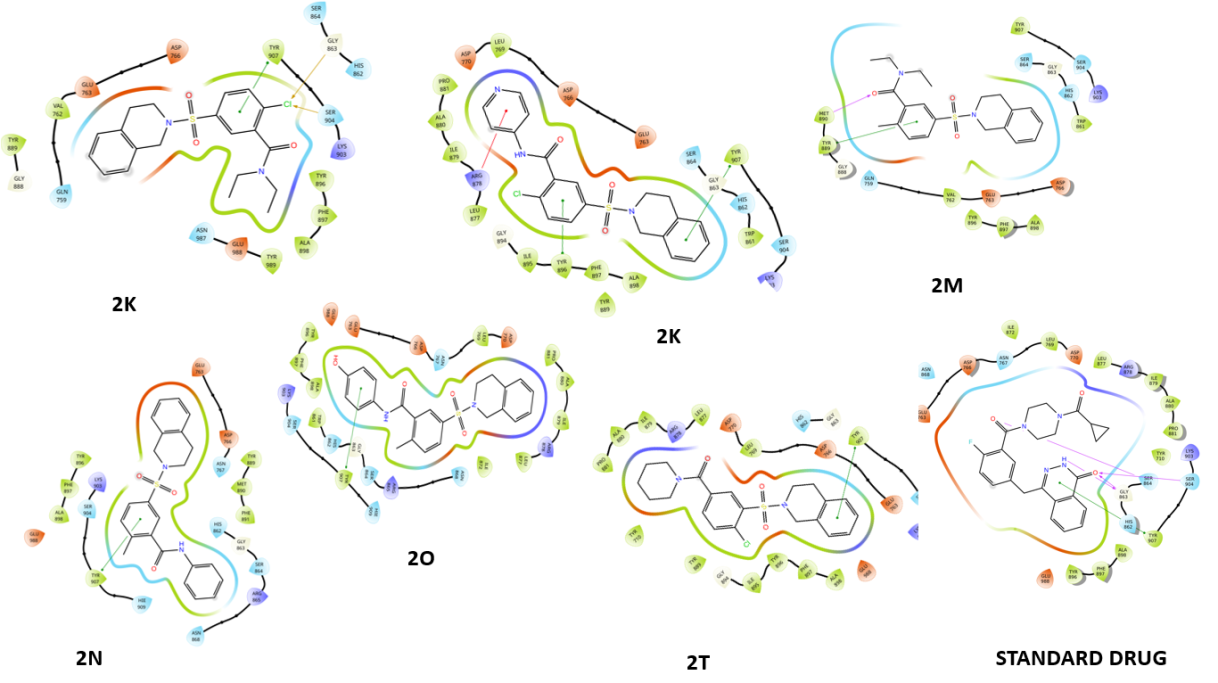

Fig. 2: Compounds 2D interaction diagrams in the PARP1 catalytic pocket (1-12) with standard

Table 2: Binding free energy (MM-GBSA) contribution (kcal/mol) for compounds 12 in PARP1 complexes

| S. No. | Compound code | aΔGBind | bΔGCoul | cΔGHB | dΔGLip | eΔGVdW |

| 1 | 2A | -76.0391 | -11.2165 | -1.3766 | -30.2542 | -60.0614 |

| 2 | 2C | -73.6328 | -10.1458 | -0.83856 | -29.4561 | -58.3218 |

| 3 | 2D | -87.2057 | -29.7099 | -1.06884 | -28.0152 | -67.9406 |

| 3 | 2I | -79.6788 | 34.50773 | -1.46966 | -29.5327 | -62.8198 |

| 4 | 2F | -62.0739 | 34.27471 | -2.07267 | -17.9552 | -68.45 |

| 5 | 2G | -68.0857 | 13.97248 | -0.96544 | -28.6317 | -76.0226 |

| 7 | 2K | -68.2183 | 33.79907 | -2.35843 | -30.0885 | -66.5585 |

| 8 | 2L | -60.181 | -10.99765 | -0.78922 | -27.2901 | -69.135 |

| 9 | 2M | -77.4534 | -8.17007 | -0.56643 | -28.7012 | -55.5661 |

| 10 | 2N | -81.6378 | -31.0081 | -2.47251 | -23.1227 | -54.5112 |

| 11 | 2O | -72.934 | -5.30678 | -0.88614 | -19.563 | -62.0459 |

| 12 | 2T | -74.4674 | -10.2257 | -1.79178 | -22.6874 | -61.5877 |

| Standard | Olaparib | -88.819 | -42.086 | -2.438 | -30.6646 | -42.427 |

aFree Energy of Binding, bCoulomb Energy, cHydrogen Bonding Energy, dHydrophobic Energy (non-polar contribution estimated by solvent accessible surface area), e Van der Waals Energy.

Compound 2D demonstrated the highest binding free energy of-87.20 kcal/mol, primarily driven by significant contributions from Coulombic energy (-29.70 kcal/mol), hydrophobic energy (Lipo,-28.01 kcal/mol), and van der Waals energy (-67.94 kcal/mol), indicating strong binding potential. Similarly, compound 2N exhibited a comparable binding free energy of -81.63 kcal/mol, with a major Coulombic energy contribution of -31.00 kcal/mol and a lower hydrophobic contribution of -23.13 kcal/mol. Compound 2L displayed notable characteristics with a binding free energy of-60.18 kcal/mol, supported by a positive Coulombic energy of-10.99 kcal/mol, a high hydrophobic energy of-27.29 kcal/mol, and a lower van der Waals energy of-69.13 kcal/mol. In comparison, the standard drug exhibited a binding free energy of -88.81 kcal/mol. Among the tested compounds, 2D showed the highest binding affinity, comparable to or even surpassing Olaparib, reinforcing its potential as a strong candidate for further investigation.

Hydrogen bonding and amino acid interactions

Fig. 2 provides a detailed representation of the hydrogen bonds formed between each compound and the amino acid residues within the catalytic pocket of PARP1 (PDB ID: 4ZZZ). These interactions play a crucial role in determining the binding affinity and stability of the protein-ligand complexes, significantly influencing overall molecular interactions and the potential inhibitory effectiveness of the compounds.

Fig. 2 presents the 2D interaction diagrams of the 12 studied compounds, illustrating their interactions within the PARP1 catalytic pocket (PDB ID: 4ZZZ). The diagrams highlight key molecular interactions: hydrogen bonding occurs between sulfonyl (S=O), hydroxyl (OH), and oxygen (O) groups with MET 890, GLU 988, and SER 904 residues, while amine (NH) and carbonyl (C=O) groups form bonds with ASP 766 and MET 890, contributing to ligand-receptor complex stability. Hydrophobic interactions between the non-polar groups of the compounds and the receptor's hydrophobic regions further enhance stability. Additionally, aromatic residues in the receptor engage in π-π stacking with aromatic rings of the compounds, while chlorine (Cl) atoms form halogen bonds with SER 904 and GLY 863. These visual representations in fig. 2 provide a clear understanding of how functional groups facilitate effective binding to PARP1, emphasizing the specific residues involved in each interaction.

MD simulation study

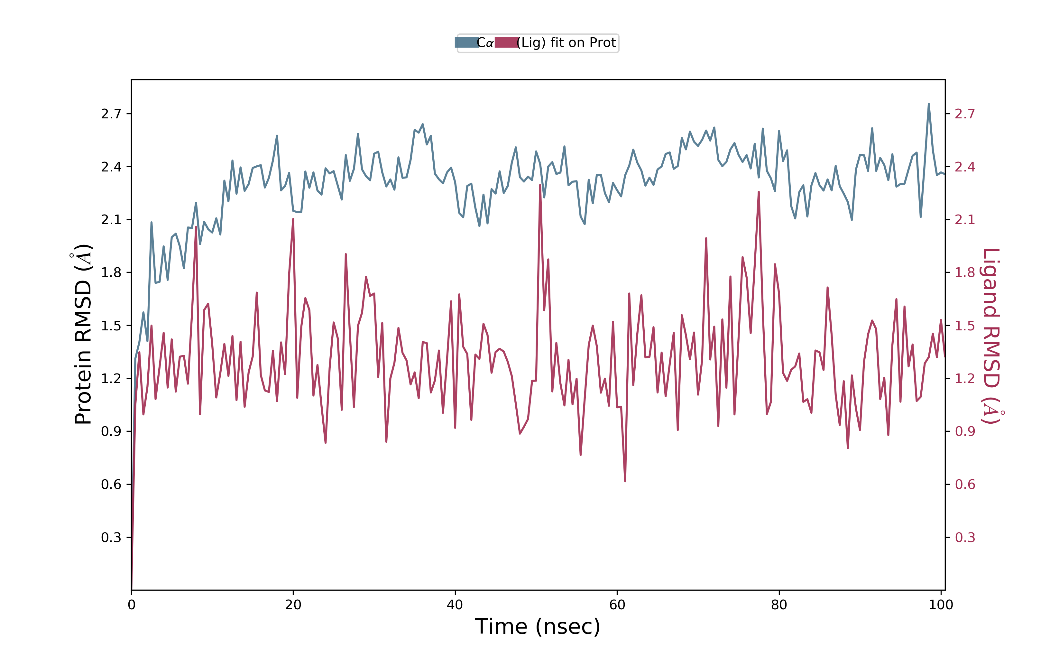

The docking pose of the ligand 2-chloro-5-((3,4-dihydroisoquinolin-2(1H)-yl)-N, N-diethyl benzamide (Compound 2D) within PARP1 (PDB ID: 4ZZZ) was subjected to a 100 ns molecular dynamics simulation. This study provided a detailed analysis of various parameters, including protein-ligand interaction fractions, protein-ligand contact durations, root mean square deviation (RMSD), and root mean square fluctuations (RMSF). Additionally, a 2D interaction diagram was generated, offering a visual representation of the key interactions stabilizing the complex.

Fig. 3: RMSD graph for compound 2D/4ZZZ complex

The RMSD analysis of the Cα atoms revealed fluctuations ranging from 1.2 to 2.7 Å for the ligand's docking pose, while the ligand’s fit to the protein exhibited values between 1.2 and 1.5 Å. Throughout the 100 ns simulation, the ligand’s Cα atoms remained stable for 90 ns, with notable stability during the final 10 ns. Specifically, from 10 to 100 ns, the ligand maintained stability within the 2.1 to 2.7 Å range, while moderate fluctuations were observed between 1.2 and 2.1 Å during the last 10 ns. Similarly, the ligand’s fit to the protein demonstrated stability for 90 ns, with the highest stability observed in the middle 10 ns. During this period, the ligand remained within the 1.2 to 1.8 Å range, whereas moderate fluctuations occurred between 0.9 and 2.2 Å during the initial 10 ns. Fig. 3 illustrates these findings, providing a comprehensive view of the ligand’s stability and interactions throughout the simulation.

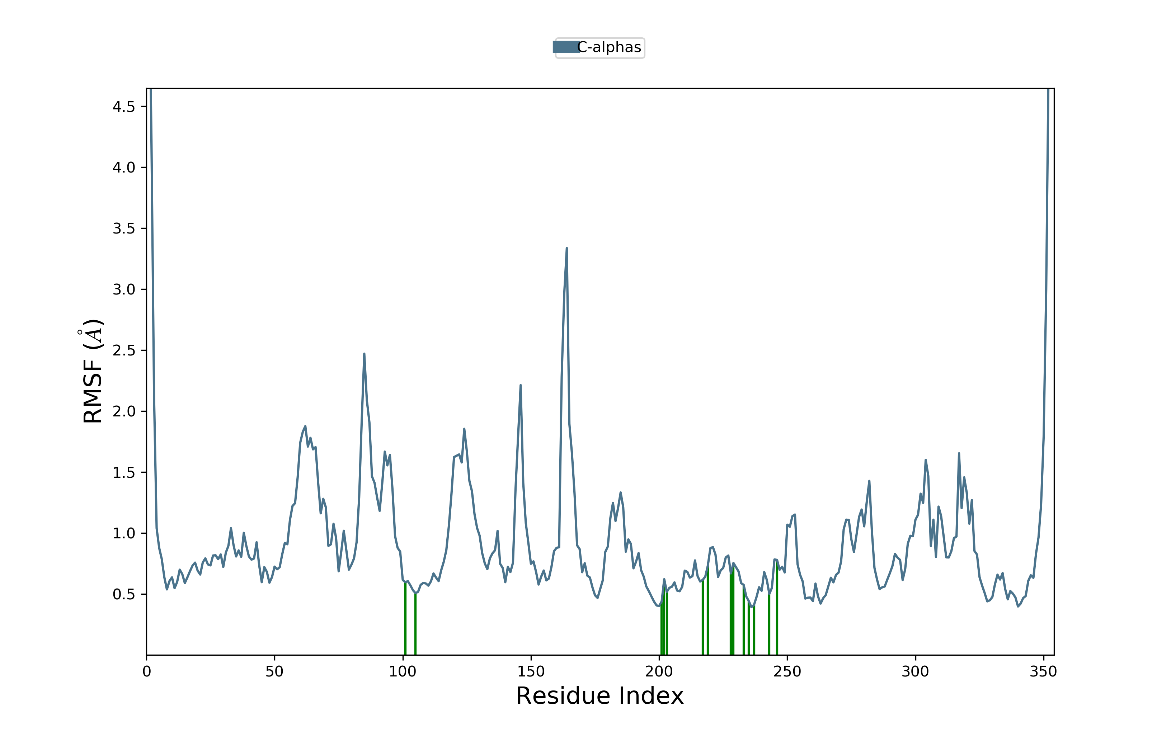

Fig. 4: RMSF diagram for compound 2D/4ZZZ complex

The RMSF analysis revealed minimal fluctuations throughout the simulation. As depicted in fig. 4, the Cα atoms initially exhibited variations between 0.5 and 0.9 Å, maintaining stability throughout the simulation. Notable adjustments in ligand interactions with amino acid residues were observed, though these variations remained minor, particularly between 100 ns and 200 to 250 ns. During these intervals, the RMSF values for the amino acids ranged from 0.5 to 0.6 Å and 0.6 to 0.9 Å, respectively. Overall, the protein-ligand complex remained fully stable, demonstrating a well-maintained interaction.

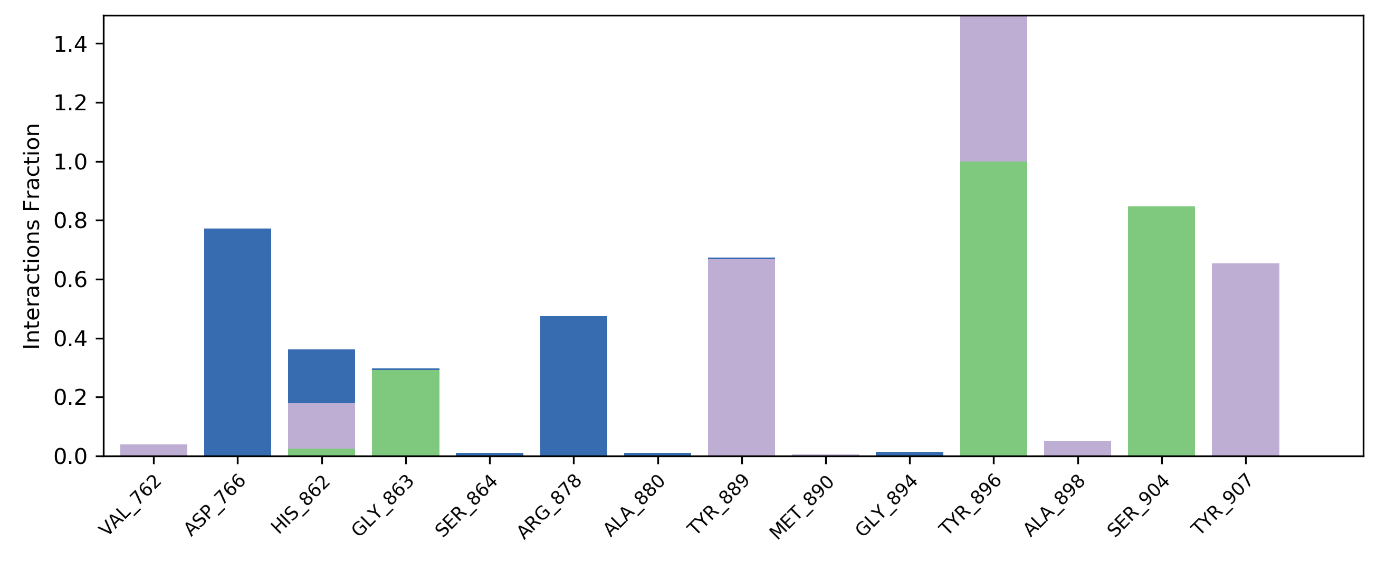

Fig. 5: Protein-ligand contacts profile for compound 2D/4ZZZ complex

As illustrated in fig. 5, the ligand consistently interacts with amino acids through various bond types, including hydrophobic, hydrogen, and water bridge interactions. The ligand formed water bridge bonds with Asp766 and Arg878, maintaining these interactions at 0.8% out of 1.4%. Additionally, hydrophobic interactions were observed with Val762, Tyr889, Ala898, and Tyr907, with a stability of 0.7% out of 1.4%. Hydrogen bonds were established with Gly863 and Ser904, maintaining an interaction rate of 0.9% out of 1.4%. Moreover, the ligand exhibited multiple interactions with His862 and Tyr896, sustaining these bonds at a complete 1.4%, highlighting its strong binding affinity.

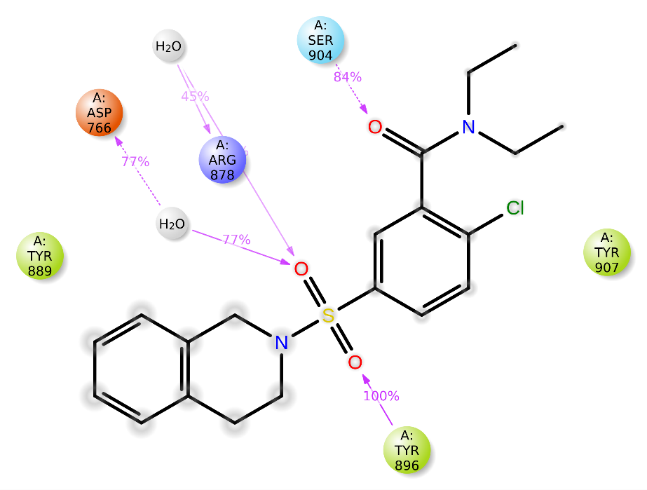

Fig. 6: 2D diagram for compound 2D/4ZZZ complex

Fig. 6 presents a 2D diagram illustrating the protein-ligand interactions. Tyr896 maintained constant hydrogen bonding with the sulfonyl group, achieving 100% stability. Additionally, Arg878 and Asp766 consistently interacted with the oxygen atom of the sulfonyl group through hydrogen bonds, exhibiting stabilities of 45% and 77%, respectively. Ser904 also formed a stable hydrogen bond with the carbonyl group, maintaining 84% stability. These findings suggest that compound 2D demonstrates strong binding affinity, highlighting its potential as a promising candidate for the development of novel anti-Alzheimer agents.

DISCUSSION

The molecular docking and dynamics studies of compound 2D against PARP1 (PDB ID: 4ZZZ) revealed its strong binding affinity, with interactions comparable to or even superior to the standard drug Olaparib. The docking results demonstrated that 2D exhibited a Glide score of -6.53 kcal/mol, which was competitive with Olaparib (-6.46 kcal/mol). Further, 2D showed enhanced interaction metrics, including van der Waals energy (-49.48 kcal/mol), Coulomb energy (-2.59 kcal/mol), and total docking energy (-52.07 kcal/mol), indicating its stable binding within the catalytic pocket of PARP1. The Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation further validated the binding stability of 2D, with RMSD fluctuations ranging between 1.2 to 2.7 Å. The Root mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) analysis indicated minimal deviations (0.5 to 0.9 Å), confirming that 2D maintained stable interactions throughout the simulation. Additionally, hydrogen bond interactions were highly stable, with Tyr896 exhibiting 100% stability and Arg878, Asp766, and Ser904 showing consistent interactions (45%, 77%, and 84% stability, respectively). When compared with previous studies, Olaparib and similar PARP1 inhibitors have shown Glide scores in the range of -5.5 to -7.0 kcal/mol, with key interactions involving Asp766, Ser904, and Tyr896 [37]. The strong hydrophobic and hydrogen bonding interactions observed in compound 2D align with previous findings on benzamide and is quinoline-based PARP1 inhibitors, which exhibit similar binding patterns with MET 890, GLU 988, and ASP 766 [38]. Furthermore, recent studies on halogen-substituted inhibitors suggest that chlorine interactions with SER 904 and GLY 863 enhance stability, which was also observed for 2D [39]. Additionally, previous studies on MD simulations of PARP1 inhibitors indicate that ligands with RMSD values below 3 Å exhibit stable interactions [40]. Our RMSD findings for 2D fall within this range, reinforcing its potential stability as a drug candidate. The Coulombic energy (-29.70 kcal/mol) and van der Waals interactions (-67.94 kcal/mol) of 2D are comparable to earlier studies on benzamide derivatives, which reported binding free energies between-80 and-90 kcal/mol [41]. The strong molecular interactions and high stability of compound 2D suggest that it could serve as a potential lead compound for developing novel PARP1 inhibitors. Further experimental validation through enzyme inhibition assays and in vivo studies is essential to confirm its therapeutic potential.

Building upon these computational insights, benzamide derivatives such as compound 2D represent a structurally promising scaffold for selective PARP1 inhibition in breast cancer. PARP1 overexpression is frequently observed in BRCA1/2-deficient breast cancers, rendering this tumor particularly sensitive to synthetic lethality approaches using PARP inhibitors. The observed stable interactions of 2D with key catalytic residues (e. g., Asp766, Tyr896, Ser904) not only mirror the interaction profiles of clinically approved inhibitors but also suggest a potentially favorable binding conformation that could be translated into biological efficacy. Previous in vitro evaluations of benzamide analogues have demonstrated potent cytotoxicity in triple-negative breast cancer cell lines through PARP1-mediated DNA repair inhibition [42]. Considering these parallels, compound 2D merits further investigation through in vitro PARP1 enzymatic inhibition assays and breast cancer cell viability studies to determine its cytotoxic potential and specificity. Follow-up in vivo studies using breast cancer xenograft models will be crucial to evaluate pharmacokinetics, tumor penetration, and therapeutic efficacy. Moreover, understanding the compound’s ADMET profile and off-target effects will further inform its suitability as a lead candidate [43]. The integration of molecular modeling, cellular assays, and animal studies will provide a comprehensive assessment of 2D's clinical relevance as a benzamide-based PARP1 inhibitor in breast cancer therapeutics.

CONCLUSION

The present study explored the binding interactions and dynamic stability of compound 2D within the PARP1 catalytic pocket (PDB ID: 4ZZZ) using molecular docking and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. The docking results revealed strong hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic, and halogen interactions with key residues such as Tyr896, Arg878, Asp766, and Ser904, ensuring stable ligand-receptor binding. MD simulations confirmed that compound 2D maintained stability with minimal RMSD and RMSF fluctuations, demonstrating its potential as a lead PARP1 inhibitor. Comparative analysis with previously reported PARP1 inhibitors, including Olaparib and benzamide derivatives, indicated that compound 2D exhibits comparable or superior binding interactions and stability. Its highly stable hydrogen bonding interactions, significant van der Waals contributions, and favorable docking scores further support its potential as an effective PARP1-targeting agent. Based on these findings, compound 2D emerges as a promising candidate for further preclinical development in PARP1-targeted drug discovery. Future studies should focus on in vitro enzyme inhibition assays, cellular assays, and in vivo pharmacokinetics to validate its therapeutic efficacy. The insights gained from this study provide a strong foundation for designing novel anti-cancer agents targeting PARP1.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to thank the Department of Pharmacology and JSS College of Pharmacy, Ooty, and Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, Tamil Nadu, for providing facilities for conducting Research.

FUNDING

No funding was received for this work.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Prudvi Raj Pulla-Conceptualization, validation, original draft preparation, and data curation.

Divya Jyothi Palati-Data curation, methodology, and writing-review and editing.

Praveen T. K and Gowramma. B-Conceptualization, validation

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Sachdev E, Tabatabai R, Roy V, Rimel BJ, Mita MM. PARP inhibition in cancer: an update on clinical development. Target Oncol. 2019;14(6):657-79. doi: 10.1007/s11523-019-00680-2, PMID 31625002.

Mateo J, Lord CJ, Serra V, Tutt A, Balmana J, Castroviejo Bermejo M. A decade of clinical development of PARP inhibitors in perspective. Ann Oncol. 2019 Sep 1;30(9):1437-47. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz192, PMID 31218365.

Engbrecht M, Mangerich A. The nucleolus and PARP1 in cancer biology. Cancers. 2020 Jul 6;12(7):1813. doi: 10.3390/cancers12071813, PMID 32640701.

Wang L, Liang C, Li F, Guan D, Wu X, Fu X. PARP1 in carcinomas and PARP1 inhibitors as antineoplastic drugs. Int J Mol Sci. 2017 Oct 8;18(10):2111. doi: 10.3390/ijms18102111, PMID 28991194.

McCann KE, Hurvitz SA. Advances in the use of PARP inhibitor therapy for breast cancer. Drugs Context. 2018;7:212540. doi: 10.7573/dic.212540, PMID 30116283.

Raj PP, Lakshmanan K, Byran G, Rajagopal K, Krishnamurthy PT, Palati DJ. Recent PARP inhibitor advancements in cancer therapy: a review. Curr Enzyme Inhib. 2022 Jul 1;18(2):92-104. doi: 10.2174/1573408018666220321115033.

Jiang X, Li X, Li W, Bai H, Zhang Z. PARP inhibitors in ovarian cancer: sensitivity prediction and resistance mechanisms. J Cell Mol Med. 2019 Apr;23(4):2303-13. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14133, PMID 30672100.

Jagtap P, Szabo C. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase and the therapeutic effects of its inhibitors. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005 May 1;4(5):421-40. doi: 10.1038/nrd1718, PMID 15864271.

Langelier MF, Planck JL, Roy S, Pascal JM. Structural basis for DNA damage dependent poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation by human PARP-1. Science. 2012 May 11;336(6082):728-32. doi: 10.1126/science.1216338, PMID 22582261.

Tao Z, Gao P, Hoffman DW, Liu HW. Domain C of human poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 is important for enzyme activity and contains a novel zinc ribbon motif. Biochemistry. 2008 May 27;47(21):5804-13. doi: 10.1021/bi800018a, PMID 18452307.

Ray Chaudhuri A, Nussenzweig A. The multifaceted roles of PARP1 in DNA repair and chromatin remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2017 Oct;18(10):610-21. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.53, PMID 28676700.

Eustermann S, Wu WF, Langelier MF, Yang JC, Easton LE, Riccio AA. Structural basis of detection and signaling of DNA single-strand breaks by human PARP-1. Mol Cell. 2015 Dec 3;60(5):742-54. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.10.032, PMID 26626479.

Shall S. Proceedings: experimental manipulation of the specific activity of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. J Biochem. 1975 Jan 1;77(1):2. PMID 166073.

Purnell MR, Whish WJ. Novel inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) synthetase. Biochem J. 1980;185(3):775-7. doi: 10.1042/bj1850775.

Terada M, Fujiki H, Marks PA, Sugimura T. Induction of erythroid differentiation of murine erythroleukemia cells by nicotinamide and related compounds. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979 Dec;76(12):6411-4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.12.6411, PMID 230509.

Shen Y, Rehman FL, Feng Y, Boshuizen J, Bajrami I, Elliott R. BMN 673, a novel and highly potent PARP1/2 inhibitor for the treatment of human cancers with DNA repair deficiency. Clin Cancer Res. 2013 Sep 15;19(18):5003-15. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1391, PMID 23881923.

Rose M, Burgess JT, O Byrne K, Richard DJ, Bolderson E. PARP inhibitors: clinical relevance mechanisms of action and tumor resistance. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020 Sep 9;8:564601. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.564601, PMID 33015058.

Bhargavi Pulukuri D, Babu Penke V, Jyothi Palati D, Raj Pulla P, Kalakotla S, Lolla S. BRCA biological functions. In: T. Valarmathi M, editor. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations diagnostic and therapeutic implications. IntechOpen; 2023. doi: 10.5772/intechopen.107406.

Dockery LE, Gunderson CC, Moore KN. Rucaparib: the past present and future of a newly approved PARP inhibitor for ovarian cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2017 Jun 19;10:3029-37. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S114714, PMID 28790837.

Curtin NJ, Szabo C. Therapeutic applications of PARP inhibitors: anticancer therapy and beyond. Mol Aspects Med. 2013 Dec 1;34(6):1217-56. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2013.01.006, PMID 23370117.

Murai J, Huang SY, Das BB, Renaud A, Zhang Y, Doroshow JH. Trapping of PARP1 and PARP2 by clinical PARP inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2012 Nov 1;72(21):5588-99. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2753, PMID 23118055.

Zhou Y, Tang S, Chen T, Niu MM. Structure-based pharmacophore modeling virtual screening molecular docking and biological evaluation for identification of potential poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1) inhibitors. Molecules. 2019 Nov 22;24(23):4258. doi: 10.3390/molecules24234258, PMID 31766720.

Griguolo G, Dieci MV, Guarneri V, Conte P. Olaparib for the treatment of breast cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2018 Jun 3;18(6):519-30. doi: 10.1080/14737140.2018.1458613, PMID 29582690.

Mirza MR, Monk BJ, Herrstedt J, Oza AM, Mahner S, Redondo A. Niraparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016 Dec 1;375(22):2154-64. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611310, PMID 27717299.

Litton JK, Rugo HS, Ettl J, Hurvitz SA, Goncalves A, Lee KH. Talazoparib in patients with advanced breast cancer and a germline BRCA mutation. N Engl J Med. 2018 Aug 23;379(8):753-63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1802905, PMID 30110579.

Coleman RL, Fleming GF, Brady MF, Swisher EM, Steffensen KD, Friedlander M. Veliparib with first-line chemotherapy and as maintenance therapy in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019 Dec 19;381(25):2403-15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1909707, PMID 31562800.

Wang L, Yang C, Xie C, Jiang J, Gao M, Fu L. Pharmacologic characterization of fluzoparib a novel poly(ADP‐ribose) polymerase inhibitor undergoing clinical trials. Cancer Sci. 2019 Mar;110(3):1064-75. doi: 10.1111/cas.13947, PMID 30663191.

Hopkins TA, Ainsworth WB, Ellis PA, Donawho CK, DiGiammarino EL, Panchal SC. PARP1 trapping by PARP inhibitors drives cytotoxicity in both cancer cells and healthy bone marrow. Mol Cancer Res. 2019 Feb;17(2):409-19. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-18-0138, PMID 30429212.

Kumar BK, Faheem N, Sekhar KV, Ojha R, Prajapati VK, Pai A. Pharmacophore-based virtual screening molecular docking molecular dynamics and MM-GBSA approach for identification of prospective SARS-CoV-2 inhibitor from natural product databases. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2022;40(3):1363-86. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1824814, PMID 32981461.

Govindarasu MY, Palani MA, Vaiyapuri MA. In silico docking studies on kaempferitrin with diverse inflammatory and apoptotic proteins functional approach towards the colon cancer. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2017;9(9):199. doi: 10.22159/ijpps.2017v9i9.20500.

Baqi MA, Jayanthi K, Rajeshkumar R. Molecular docking insights into probiotics SAKACIN P and SAKACIN a as potential inhibitors of the COX-2 pathway for colon cancer therapy. Int J App Pharm. 2025;17(1):153-60. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2025v17i1.52476.

Redhu S, Jindal A. Molecular modelling: a new scaffold for drug design. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2013;21:5(5 Suppl 1):5-8.

Shaikh SI, Zaheer Z, Mokale SN, Lokwani DK. Development of new pyrazole hybrids as antitubercular agents: synthesis biological evaluation and molecular docking study. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2017;9(10):50-6. doi: 10.22159/ijpps.2017v9i11.20469.

Jorgensen WL, Maxwell DS, Tirado Rives J. Development and testing of the OPLS all-atom force field on conformational energetics and properties of organic liquids. J Am Chem Soc. 1996 Nov 13;118(45):11225-36. doi: 10.1021/ja9621760.

Mark P, Nilsson L. Structure and dynamics of the TIP3P, SPC, and SPC/E water models at 298 K. J Phys Chem A. 2001 Nov 1;105(43):9954-60. doi: 10.1021/jp003020w.

Kalibaeva G, Ferrario M, Ciccotti G. Constant pressure constant temperature molecular dynamics: a correct constrained NPT ensemble using the molecular virial. Mol Phys. 2003 Mar 20;101(6):765-78. doi: 10.1080/0026897021000044025.

Hirlekar BU, Nuthi A, Singh KD, Murty US, Dixit VA. An overview of compound properties multiparameter optimization and computational drug design methods for PARP-1 inhibitor drugs. Eur J Med Chem. 2023 Apr 5;252:115300. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2023.115300, PMID 36989813.

Li J, Zhou N, Cai P, Bao J. In silico screening identifies a novel potential PARP1 inhibitor targeting synthetic lethality in cancer treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 2016 Feb 19;17(2):258. doi: 10.3390/ijms17020258, PMID 26907257.

Sofia MJ, Moore TW, Pomper MG. Annotated bibliography of Prof. John A. Katzenellenbogen, PhD. J Med Chem. 2025 Feb 27;68(4):3911-42. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5c00224, PMID 40012520.

Jayanthi K, Ahmed SS, BAQI MA, Afzal Azam MA. Molecular docking dynamics of selected benzylidene amino phenyl acetamides as TMK inhibitors using high throughput virtual screening (HTVS). Int J App Pharm. 2024;16(3):290-7. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2024v16i3.50023.

Cao R. Free energy calculation provides insight into the action mechanism of selective PARP-1 inhibitor. J Mol Model. 2016 Apr;22(4):74. doi: 10.1007/s00894-016-2952-x, PMID 26969680.

Ambur Sankaranarayanan R, Florea A, Allekotte S, Vogg AT, Maurer J, Schafer L. PARP targeted auger emitter therapy with [125I]PARPi-01 for triple-negative breast cancer. EJNMMI Res. 2022 Sep 14;12(1):60. doi: 10.1186/s13550-022-00932-9, PMID 36104637.

Li J, Zhou N, Cai P, Bao J. In silico screening identifies a novel potential PARP1 inhibitor targeting synthetic lethality in cancer treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 2016 Feb 19;17(2):258. doi: 10.3390/ijms17020258, PMID 26907257.