Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 5, 2025, 238-252Original Article

IMPROVED WOUND HEALING ACTIVITY THROUGH SYNERGISTIC APPROACH OF PUMPKIN SEED OIL AND CURCUMIN LOADED MODEL IN MICROGEL

MARGRET CHANDIRA RAJAPPA1*, AJITH KANNAN1, NAGASUBRAMANIAN VENKATASUBRAMANIAM1, LOKESH VENKATACHALAM1, SELVARAGAVAN KARNAN1, DOMINIC ANTONYSAMY2

1Department of Pharmaceutics, Vinayaka Mission’s College of Pharmacy, Vinayaka Mission’s Research Foundation (DU), Ariyanoor, Salem-636308, India. 2Department of Engineering, Sona College of Technology, Salem-636005, India

*Corresponding author: Margret Chandira Rajappa; *Email: mchandira172@gmail.com

Received: 26 Mar 2025, Revised and Accepted: 02 Jul 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: This study aimed to develop a curcumin microgel with lipophilic encapsulation using pumpkin seed oil to enhance wound healing.

Methods: Curcumin was analyzed using ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectrophotometry, and microgels (CP1-CP6) were formulated with pumpkin seed oil encapsulation. Physicochemical tests were performed, and the optimized formulation was selected based on diffusion kinetics. The optimized formulation was subjected to wound healing studies through scratch wound heal assay.

Results: The calibration curve of curcumin showed a correlation coefficient>0.973. Drug-excipient studies revealed excellent compatibility. The optimized formulation, CP5 had the lowest zeta potential and highest viscosity, spreadability, and extrudability. CP5 released 94.59% of curcumin in 8 h, following the Korsmeyer-Peppas model. The minimum effective concentration promoting complete wound healing was 50µg/ml in L6 cell lines. CP5 remained stable for three months at 40±2 °C/75±5% RH.

Conclusion: Pumpkin seed oil effectively encapsulated curcumin, enhancing its wound healing potential. This microgel formulation showed promise for pharmaceutical applications, and future studies can investigate its pharmacodynamics and wound healing mechanisms.

Keywords: Curcumin, Wound healing, Lipophilic encapsulation, Microgel, Pumpkin seed oil

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i5.54322 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

External Wound healing is a multifaceted mechanism in human body including four main Phases, namely Hemostasis, Tenderness, Hyperplasia and Rejuvenation [1]. Duration of wound healing depends on the complexity and surface area of the inflicted wound. Major external factors include infection and necrosis of affected tissues [2]. In order to accelerate the development of wound healing, the selected active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) containing formulation must promote site-specific rapid blood coagulation. However, the role of an ideal wound healing agent does not cease there [3]. API must be able to attract monocytes and neutrophils in sufficient populations to the site of injury at the initial stages. Subsequently, the fibroblasts must be attracted after inflammation. It should be noted that the second phase of wound healing (Inflammation) must be restricted to a minimum, because, high pro-inflammatory stimuli can possibly lead to the formation of chronic wound [1, 4, 5]. Thus, it is ideal for an API to be anti-inflammatory in nature to assist wound healing [4, 5].

Curcumin, a natural polyphenol, is eminent for its anti-hyperplastic and anti-microbial effects. One of its key roles is in preventing the transformation of fresh wounds into chronic ones, providing reassurance about its effectiveness in wound healing [6, 7]. Despite its tendency to delay hemostasis due to its anti-coagulant activity, the promising aspect of Curcumin's ability to prevent microbial invasion at the affected site instills confidence in its wound healing properties [8].

On the other hand, Pumpkin seed oil possesses wound healing properties due to the presence of poly unsaturated fatty acids like oleic acid and linoleic acid. These compounds are known for its wound healing properties which is achieved by a pro-inflammatory mechanism. Other important phytochemicals in pumpkin seed oil involved in wound healing include phytosterols and tocopherols. Other than the antioxidant activity, γ-tocopherol can assist in reducing inflammation by inhibiting PGE2 accumulation at the inflammation site [9, 10].

This research introduces a novel approach by harnessing the unique properties of pumpkin seed oil to address the anti-coagulant activity of Curcumin. The encapsulation of Curcumin with pumpkin seed oil has the potential to keep its anti-platelet activity dormant, while the conversion of the Curcumin-loaded pumpkin seed oil globules into microstructures could achieve high permeability. Because, immediate release on the affected site can lead to anti-coagulation activity due to inhibitory nature of API for formation of thromboxane A2 [11]. Besides, uncontrolled release of curcumin can lead to cytotoxicity. Hence, there is a need to control the drug release of curcumin to establish effective wound healing. Adjusting the release of the drug controls reduces the re-inflammation ability [12, 13]. This innovative strategy could potentially revolutionize the process of hemostasis and is certain to pique the interest of professionals in the field of medical research [14-16].

Stimuli responsive hydrogels can be helpful in achieving the controlled release in a smart manner. The release is usually controlled through a external stimulus like pH and temperature of wound, such that the controlled 'smart' release provides safe healing of wound effectively. Innovations in microgel architecture-including core–shell configurations, multi-stimuli responsiveness, and mechanochemical synthesis methods—have opened new pathways for precise functional design and expanded applications [17, 18].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Active pharmaceutical ingredient (Curcumin) [CAS: 458-37-7; Laboratory grade, 99% pure] was procured from stabicon life science private limited. Pumpkin seed oil [CAS: 8016-49-7] was procured from MN Chemical and Scientific Instruments. Triethanolmaine [CAS: 102-71-6; Laboratory grade, 99% pure], Sodium alginate [CAS: 9005-38-3], Carbopol [CAS: 9003-01-4] were purchased from Loba Chemie.

Organoleptic investigation

The procured API and prepared microgel formulations were subjected to organoleptic Investigation. Color, odor, taste, physical nature and texture of API and excipients were investigated. This investigation was performed to understand the basic quality of API and excipients.

Solubility

The API (Curcumin) was dissolved in a range of solvents of varying polarity. Ethanol, Acetone Distilled Water, Glycerin were some of the solvents used in this experimental part. This was useful in identifying the solvent for UV-Vis spectral characterization of the API [19].

UV-Vis spectrophotometry

100 mg of API was dissolved in 100 ml of dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) to produce a concentration of 1 mg/ml. Then 10 ml of resultant solution was taken and diluted with DMSO to produce 100µg/ml solution. From this solution, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 ml of 100 µg/ml solution was taken and diluted up to 10 ml with DMSO. Thus, 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 µg/ml solutions were prepared and checked for λmax between 400 to 800 nm using UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Systronics UV-2202). Then, coordination with Beer-Lambert’s law was calculated [20].

Drug-Excipient compatibility studies

We analyzed the compatibility between API (Curcumin) and other excipients through Attenuated Total Reflection-Fourier Transform Infrared (ATR-FTIR) spectroscopy. ATR-FTIR spectroscopy was considered superior over FT-IR spectroscopy due to high precision and lack of rigorous sampling method. Samples were placed in ATR-FTIR spectrometer (Bruker Alpha-II) and spectrum analysis was performed in the range between 400 cm-1 and 4000 cm-1 [21].

Formulation of curcumin loaded microgel

The API was dissolved in sufficient quantity of ethanol and kept aside. Gel base was prepared by mixing swelling agent, polymer and preservative together with sufficient quantity of water to induce the swelling process. After proper mixing of the ingredients using a mechanical stirrer at a predetermined speed for a predetermined time, Pumpkin Seed oil was added to the resultant mixture and mixed thoroughly. The ratio of Pumpkin Seed oil and curcumin was always 1:1 in all microgel formulations. This ratio was selected in order to maintain a balance between anti-inflammatory (Curcumin) and wound healing (Pumpkin seed oil) properties. Finally, the ethanolic solution of Curcumin was uniformly distributed to the resultant mixture. Triethanolamine was employed as a pH stabilizer to carefully stabilize and achieve skin-compatible pH. Swelling agent was chosen between Sodium Alginate and Carbopol in three different concentrations (0.5%, 1%,1.5%) [22, 23].

Globule size measurement

This was performed using dynamic light scattering (DLS) using Zetasizer (Malvern Zetasizer ZSU3100). In this study, we placed a sample of microgel in a disposable cuvette and examined at 25 °C with a count rate of 151.3 kcps. This evaluation test was performed to understand the particle size distribution of microgel formulation [24].

Zeta potential

Zeta Potential was analyzed to understand the electrical property of microgel formulations (CP1-CP6). The electrodes of the Zetasizer (Malvern Zetasizer ZSU3100) were made in contact with the capillary cell containing the sample. The electrical charge of the sample was determined in millivolts (mV) [25].

pH determination

Digital pH meter (Remi Electronics) was applied to determine the pH level of microgel formulation (CP1-CP6). We successfully validated the equipment by triple point calibration technique using buffer solutions of different pH (3.9, 7.6 and 9.2). After calibration process, the electrode was immersed in each microgel formulation and the continuous reading was observed till a stable value was produced [26, 27].

Viscosity

Samples pre-incubated at 25 °C for 16 h were employed in this experimental process. Torque was maintained between the range of 10% and 90% under continuous incubation. Rotational Viscometer was operated at different pre-determined speeds (0.5, 1, 2.5, and 5 RPM). Viscosity of each formulation batch was expressed in centipoises (cps) [28, 29].

Spreadability

Sufficient quantity (2 gm) of each microgel formulation (CP1-CP6) was placed between two glass plates. The upper glass plate was mechanically connected through a pulley to a predetermined weight. The time taken for upper plate to reach the predetermined distance was carefully noted. The spreadability (S) was calculated using the following formula [30, 31]:

Where,

M-Weight tied to upper glass slide (g)

L-Length of Glass Slide (cm)

T-Time Taken (Sec)

Extrudability

500 gm of microgel formulation packed in a collapsible aluminum tube was placed between the glass plate without the cap. After applying predetermined weight on the formulation, the percentage of extruded gel was gathered and weighed. Minimum Extrudability must not be less than 70% [32, 33].

In vitro drug release profiling

Preparation of acetate buffer

7.35 gm of sodium acetate and 620.7 mg of acetic acid were mixed together. After adjustment of pH to 5.5, final volume was adjusted to 1000 ml using distilled water [29]. This buffer was selected on the basis of normal skin pH range. This also can be used as inflammatory skin models, because, pH increases only by 0.2-0.4 units in inflammatory conditions [34, 35].

Diffusion studies

The diffusion studies were performed using a Franz Diffusion cell. The receptor compartment was filled with 20 ml Acetate buffer (pH 5.5) and maintained at 37 °C. The microgel sample was retained in the donor compartment over a dialysis membrane. Small quantity of Aliquot (1 ml) was taken as sample and subsequently substituted with fresh Acetate buffer at regular sampling intervals up to 8 h. UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Systronics UV-2202) was applied to evaluate the resulting sample at 417 nm in triplicate [36].

Kinetic profiling studies

Based on the diffusion studies, pharmacokinetic profiling was performed to understand the release kinetics. Models for Zero-order kinetics, First-order kinetics, Korsemeyer-Peppa’s plot, Higuchi plot and Hixson-Crowell plot were modelled systematically for each microgel formulation batch [36, 37].

Evaluation studies for optimized formulation

Scanning electron microscopy

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) was performed to understand the particle size distribution of the microgel formulation (CP5). The sample was prepared by sputter coating a dried sample of microgel placed on an aluminum stub with gold (Au) for 30 seconds under vacuum conditions. Sample was placed in the sample holder of Scanning Electron Microscope (Carl Zeiss JSM 6400, Japan) and observed at different levels of magnification (1.94, 4.98, 5.00, 7.99, 11.26, and 16.54 kx) [29, 38, 39].

In vitro cell line assay

Incubation of cell lines

The cell line studies for the optimized Curcumin loaded pumpkin seed microgel (CP5) were performed at Athmik Biotech Solutions, Thiruvananthapuram, India. Scratch Wound heal assay was performed to understand the mechanism, efficacy and pharmacodynamics of the optimized microgel. Dulbecco’s Modified Eagles Medium was augmented with 10% heat inactivated Foetal Bovine Serum (FBS) and 1% antibiotic cocktail composing of Penicillin (100U/ml), Streptomycin (100µg/ml), and Amphotericin-B (2.5µg/ml). Predetermined surface area of L6 (Rat Skeletal muscle) Cell line (25 m2) was cultured in Tissue Culture Flasks under CO2 free environment maintained at 37 °C.

Sample inoculation in cell lines

The cells (10,00,000 cells/well) were seeded on six well plates and allowed to acclimatize to the culture conditions such as 37 °C and 5% CO2 environment in the incubator for 24 h. The test samples were prepared in cell culture grade DMSO (10 mg/ml) and filter sterilized using 0.2 µm Millipore syringe filter. The sample was added to the wells at different concentrations (25, 50, 100 µg/ml) containing cultured cells of at least 80% confluence keeping untreated wells as control.

Determination of wound healing activity

Cell line monolayer was scrapped linearly to stimulate a scratch using a 200uL pipette tip. Removal of debris was performed by washing cells with growth medium. Proper precaution was taken to produce precise scratch marks on subsequent screening. Wound healing activity of the optimized microgel formulation (CP5) was monitored under Phase Contrast Microscopy by capturing photomicrographs at 12 h interval up to 36 h.

Determination of cell line migration rate

Cell migration rate was determined by analyzing the images (ImageJ software) and percentage of the closed area with the value obtained before the process. The percentage of closed area representing the migration of cells is directly proportional to the efficacy of wound healing activity [40, 41].

Stability studies

Accelerated Stability Studies were conducted per International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) guidelines by placing the optimized formulation in a Humidity Chamber (Rashmi Technology). Assay, Physical Description, disintegration time, and content uniformity were fixed as the parameters to analyze the quality of the tablet for 3 mo [42, 43].

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using Jamovi (Version 2.3.28) mean and standard deviation (mean±SD) was determined for other evaluation tests. One way Analysis of variance (ANOVA) single factor was performed for the evaluation tests (Zeta potential, Viscosity, pH, spreadability, extrudability). Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) was performed as a post-hoc test to understand the statistically significant difference between groups. Two-way ANOVA test was performed for the in vitro release studies, with Tukey’s HSD as the post-hoc test. For in vitro wound healing studies, Shapiro-Wilk test was initially applied to understand the normality of the distribution. Friedman’s test was performed due to small sample size (n=4) followed by Durbin-Conover test.

RESULTS

Organoleptic inspection

We observed that API (Curcumin) exhibited yellow color, aromatic odor and distinctive spicy taste.

Solubility studies

Curcumin exhibited high solubility with ethanol and Acetone. However, it was sparingly (or) almost insoluble in water and other hydrophilic solvents due to polyphenolic structure.

UV-Vis spectrophotometry

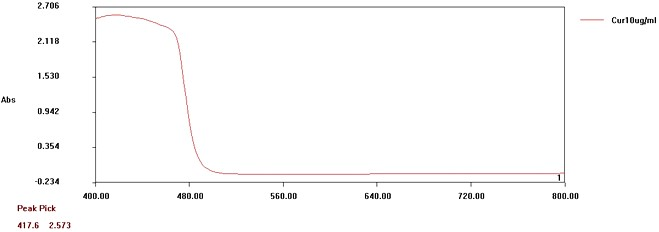

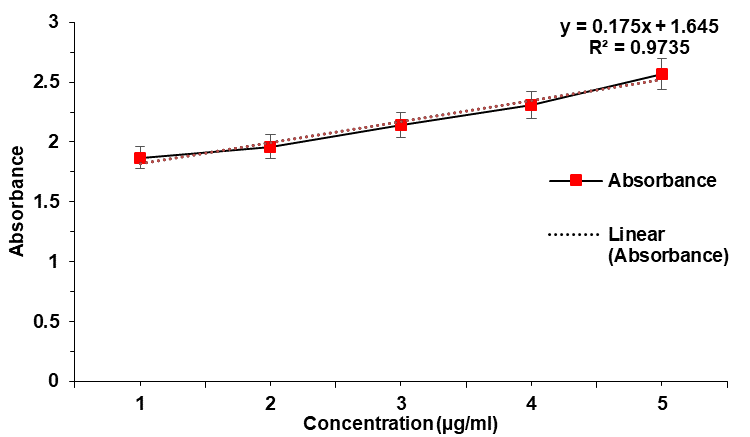

Curcumin exhibited a smooth peak (λmax) at 417.6 nm in the visible region. The graph of absorbance of Curcumin is displayed in fig. 1. The calibration curve of API is shown in fig. 2 and table 1.

Fig. 1: Absorbance graph of curcumin under UV-Vis conditions. It exhibited a peak of 417.6 nm

Fig. 2: Calibration graph of curcumin, error bars indicate SD values

Besides, the API exhibited a correlation co-efficient (R2)>0.973 with a slope (m) of 0.175 in the calibration curve of curcumin. A maximum absorbance of 2.57 was observed at 10 μg/ml. Maximum absorbance difference of 0.26 was observed between 8μg/ml and 10μg/ml. The Limit of Detection and Limit of Quantification were 0.288μg/ml and 0.873μg/ml respectively (σ=0.0153).

Table 1: Calibration of curcumin at different concentrations by absorbance at 418 nm

| Conentration (µg/ml) | Absorbance at 418 nm |

| 2 | 1.87±0.05 |

| 4 | 1.96±0.05 |

| 6 | 2.14±0.03 |

| 8 | 2.31±0.06 |

| 10 | 2.57±0.05 |

Results are expressed as mean±SD, n=3

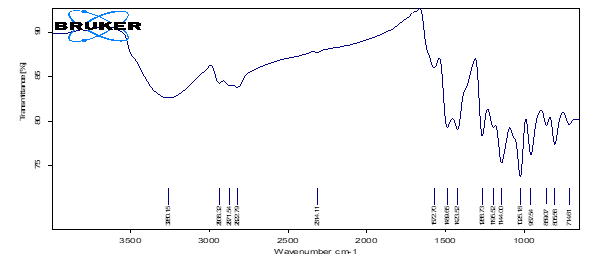

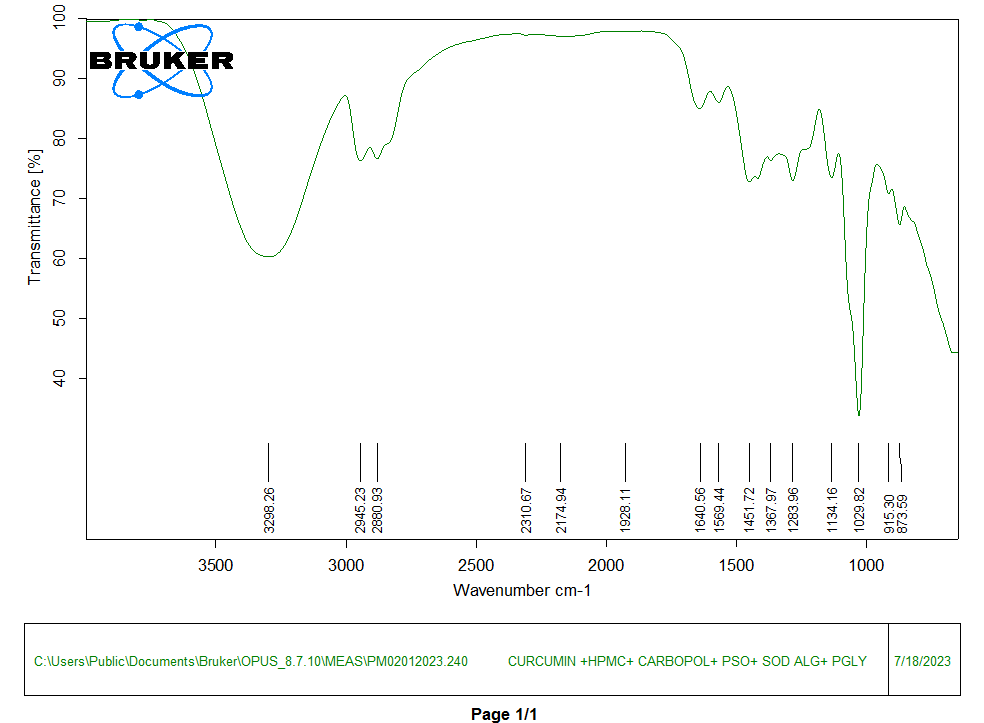

Drug-excipient compatibility studies

A total of 16 distinct peaks were observed in the API. Subsequently, 15 peaks are observed in a physical mixture containing API and excipients. The sharpest peak was observed to be 1125 cm-1 and 1030 cm-1 for API and physical mixture respectively. There was a distinct peak at 1424 cm-1 submissive of the presence of enolic bond. Besides, we observed a broad peak at 3260 cm-1, which had curved towards lower transmittance forming easily visible plateau in the physical mixture. The sharp peaks in the range between 1400 cm-1and 1500 cm-1 (1424 cm-1, 1490 cm-1) confirmed the presence of both aromatic nucleus and a strong carboxylate group. The peak at 1144 cm-1 with intermediate intensity was noteworthy for interpretation and confirmation of chemical structure of API. The ATR-FTIR spectrum of API (Curcumin) was displayed in fig. 3 and fig. 4.

Fig. 3: ATR-FTIR spectrum of curcumin

Fig. 4: ATR-FTIR spectrum of physical mixture (API and excipients)

10 out of 11 significant peaks were visible in the physical mixture indicating the chemical integrity of the mixture. The table 2 provides the comparison of significant peaks of curcumin and physical mixture.

Table 2: Comparison of significant peaks of curcumin with physical mixture

| S. No. | Curcumin (cm-1) | Physical mixture (cm-1) | Vibration assignment | Possible functional group |

| 1 | 3260.15±7.23 | 3298.26±8.42 | O-H stretching | Phenolic –OH groups |

| 2 | 2938.32±4.70 | 2945.23±6.23 | C–H asymmetric stretching | Aliphatic –CH₃ and-CH₂ groups |

| 3 | 2871.54±2.35 | 2880.93±8.01 | C–H symmetric stretching | Aliphatic –CH₃ and –CH₂ groups |

| 4 | 1572.70±3.32 | 1569.44± 5.92 | C-O stretching | Aromatic rings |

| 5 | 1489.65±1.86 | - | C=C aromatic stretching | Aromatic rings |

| 6 | 1456.00±2.47 | 1451.72±5.12 | CH₂ bending or scissoring | Methylene groups in the alkyl chain |

| 7 | 1266.73±1.03 | 1283.96±3.31 | C=C stretching | Phenolic C–O group |

| 8 | 1144.00±1.68 | 1134.16± 4.67 | C–O–C stretching | Ether linkage in the aromatic structure |

| 9 | 1025.18±4.98 | 1029.82±0.95 | C–H bending or C–O stretching | Alkoxy or phenolic group vibrations |

| 10 | 957.54±5.15 | 915.30±3.26 | C–H bending (Out-of-plane) | Substituted aromatic rings |

| 11 | 889.37±3.37 | 873.59±2.24 | C–H bending (Out-of-plane) | Aromatic rings |

Mean±SD (n = 3)

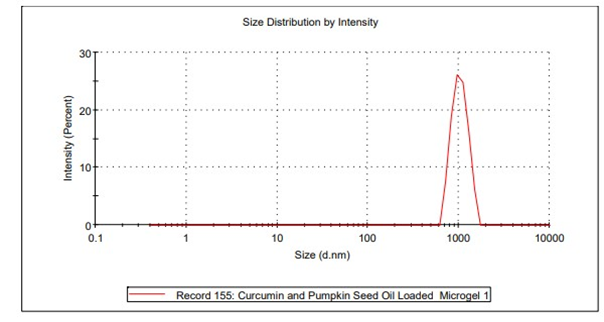

Globule size measurement

An intensity of 25% was observed at a size of 1000 nm. There was no other peak or plateau obtained in the evaluation study. Globule size determination of the microgel is displayed in fig. 5.

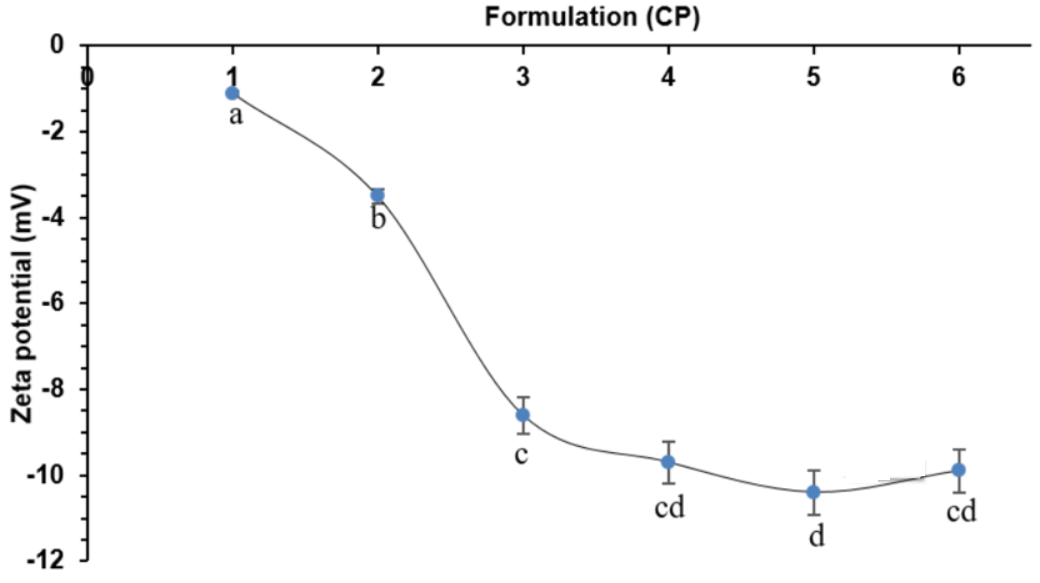

Zeta potential

Every microgel formulation exhibited Zeta potential not more than-1 mV. The highest and least Zeta potentials were exhibited by CP1(-1.1 mV) and CP5 (-10.4 mV) respectively. Four of the six micro gel formulations (CP3 to CP6) expressed Zeta potential more than-5 mV. Zeta potential of different microgel formulations (CP1-CP6) are shown in fig. 6.

One-way ANOVA test exhibited statistical insignificance (p<0.01) with a F-statistic of 2299.2. Under Tukey HSD test, all the pairs exhibited statistical significant difference (p<0.05) except one pair (CP4 vs. CP6; p-value: 0.654). Out of all the statistical pairs, all pairs expressed highly statistical significant difference (p<0.01) except two pairs (CP4 vs CP5; CP5 vs CP6). These two pairs expressed p-value lesser than only 0.05.

Fig. 5: Globule size determination of curcumin loaded microgel formulation

Fig. 6: Zeta potential of curcumin microgel formulation batches (CP1-CP6). The formulations with the same letter (a,b,c,d) indicate the statistically insignificance to each other under Tukey’s HSD test. Error bars indicate SD values

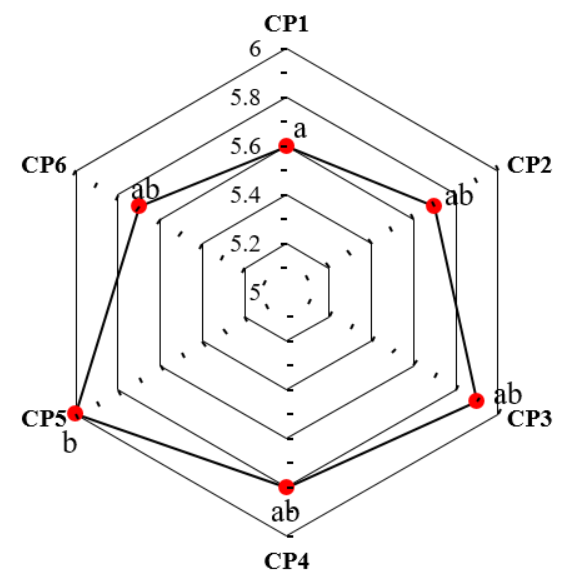

pH

We observed that the prepared microgel formulations (CP1-CP6) were weakly acidic. The pH of microgel formulations arranged between 5.6 to 6. The pH of various microgel formulations (CP1-CP6) is displayed in fig. 7.

Fig. 7: pH of various curcumin loaded microgel formulations (CP1-CP6). The formulations with the same (a or b or ab) indicate the statistically insignificance to each other under Tukey’s HSD test

One-way ANOVA test expressed the statistically significance within the microgel formulations (p<0.01). Post-hoc test exhibited statistically significant difference between CP1 and CP5.

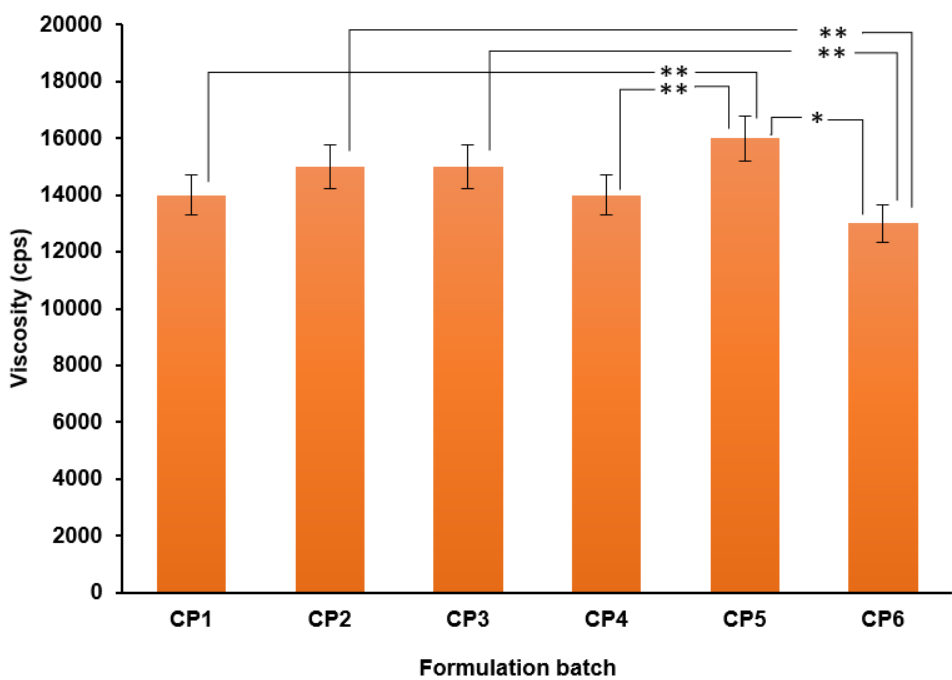

Viscosity

The highest viscosity was expressed by CP5 (16000 cps). Fig. 8 displays the viscosity of various microgel formulations (CP1-CP6).

The formulations (CP1-CP6) were statistically significant (p<0.001) in one-way ANOVA test. Tukey’s HSD test performed as a post-hoc test revealed five statistically significant pairs. CP5 and CP6 were statistically different from three formulations (fig. 8).

Spreadability

We observed that the highest spreadability was expressed in CP5. On the contrary, CP1 exhibited the least spreadability of 18.18 g. cm/sec. The statistical analysis revealed statistical significance (p<0.05) between groups in one-way ANOVA. Under post-hoc test, there were four pairs with statistically significant difference (p<0.05). CP5 constituted three of the four pairs (CP1 vs CP5; CP2 vs CP5; CP3 vs CP5), while the remaining pair included CP1 vs CP6.

Extrudability

The highest extrudability was expressed by CP5 (48.88 kPa) due to excellent viscosity and spreadability. Geometric improvement of extrudability in microgel formulations containing Sodium Alginate (CP1-CP3). There was statistically significant difference (p<0.01) between the groups (CP1-CP6). Under post-hoc study, 7 pairs were observed to possess statistically significant differences out of which CP5 was found to have statistically significant differences with four formulations (CP1, CP2, CP3, CP4). CP6 was observed to express statistically significant differences with two formulations (CP1, CP2). The results are shown in table 3.

Fig. 8: Viscosity of various microgel formulations (CP1-CP6). *means the p<0.01 and **means p<0.001 in Tukey’s HSD test. Error bars indicate SD values

Table 3: Spreadability and extrudability of microgel formulations (CP1-CP6). The formulations with the same (a or b or ab) indicate the statistically insignificant to each other under Tukey’s HSD test

| Formulation code | Spreadability (g. cm/sec) | Extrudability (kPa) |

| CP1 | 18.18±1.03a | 36.32±8.73a |

| CP2 | 19.00±3.59ab | 38.45±15.51ab |

| CP3 | 19.58±0.42ab | 42.22±12.99bc |

| CP4 | 20.21±3.39ab | 41. 57±6.94bc |

| CP5 | 22.03±1.38b | 48.88±12.50d |

| CP6 | 21.34±1.09b | 47.11±4.32cd |

Results are expressed as mean±SD, n=3. Formulations with different letters (a, b, c, d, e) are not significantly different (p<0.05) according to Tukey's HSD test

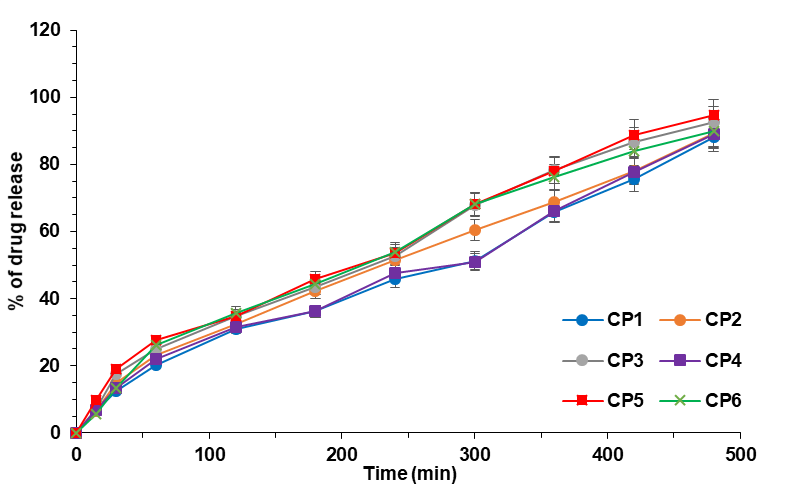

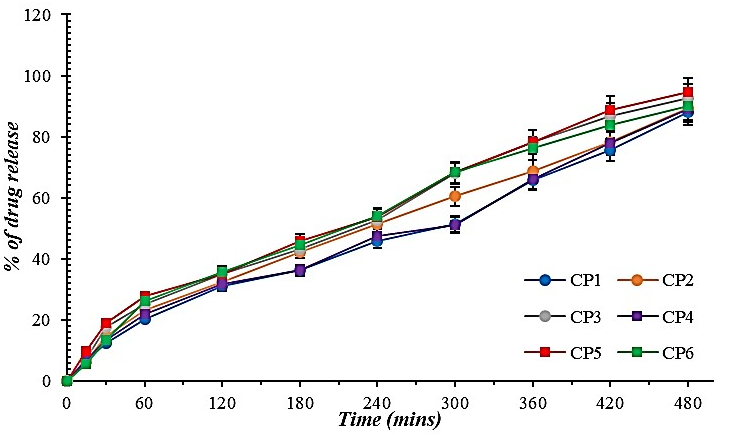

In vitro drug release profile

CP1 and CP4 were the microgel formulations not to show 50% API diffusion in 4 h. All the microgel formulations (CP1-CP6) revealed a drug release of over 85% within 8 h. The microgel formulation (CP5), which was theoretically strong in other evaluation tests, demonstrated a similarly strong impact in diffusion release by releasing a staggering 94.59% of Curcumin in 8 h. The in vitro release studies of pumpkin seed oil encapsulated curcumin microgel formulations are shown in fig. 9 and table 4.

Table 4: In vitro dissolution release of pumpkin seed oil-encapsulated curcumin loaded microgel formulations (CP1-CP6)

| S. No. | Time (min) | Cumulative percentage of drug release (%) | |||||

| CP1 | CP2 | CP3 | CP4 | CP5 | CP6 | ||

| 1 | 0 | 0±0.00 | 0±0.00 | 0±0.00 | 0±0.00 | 0±0.00 | 0±0.00 |

| 2 | 15 | 6.42±3.07a | 6.54±2.18a | 7.17±3.02ab | 6.77±2.87ab | 9.75±1.84b | 5.66±3.78a |

| 3 | 30 | 12.44±3.12a | 14.77±3.03ab | 17.65±3.33c | 13.46±2.10ab | 18.89±2.14c | 13.33±3.75ab |

| 4 | 60 | 20.19±5.75a | 23.24±2.56ab | 25.09±2.01bc | 21.88±2.67ab | 27.67±3.69c | 26.22±4.19bc |

| 5 | 120 | 31.02±4.65a | 32.32±4.09ab | 34.87±3.96bc | 31.65±3.61ab | 34.86±4.13bc | 35.77±2.96c |

| 6 | 180 | 36.24±3.23a | 42.23±3.42b | 43.32±2.95bc | 36.19±2.63a | 45.76±3.92c | 44.44±4.05bc |

| 7 | 240 | 45.72±4.01a | 51.44±3.91b | 52.66±1.99bc | 47.51±4.07ab | 53.53±2.96c | 53.88±3.05bc |

| 8 | 300 | 51.34±2.52a | 60.44±2.90b | 67.94±3.35d | 51.01±4.26a | 68.32±3.89d | 68.32±2.48d |

| 9 | 360 | 65.89±2.97a | 68.87±3.25b | 78.35±3.62d | 66.17±3.58ab | 78.12±2.77d | 76.22±4.08c |

| 10 | 420 | 75.66±3.07a | 78.12±4.01b | 86.71±4.26d | 77.77±2.88bc | 88.87±4.26d | 83.89±2.89c |

| 11 | 480 | 88.15±2.23ab | 89.45±3.62b | 92.57±2.80c | 89.11±3.44b | 94.59±3.92c | 89.88±3.67b |

Results are expressed as mean±SD, n=3. Formulations with different letters (a, b, c, d, e) are not significantly different (p<0.05) according to Tukey's HSD test.

Fig. 9: In vitro diffusion release of curcumin loaded pumpkin seed oil loaded microgels (CP1-CP6). Error bars indicate SD values

CP5 showed significant differences with other formulations consistently at different time points. Besides, CP5 also expressed higher mean value of drug release than the other formulations. This proves that the formulation CP5 exhibited the highest drug release with statistical significance compared to other formulations.

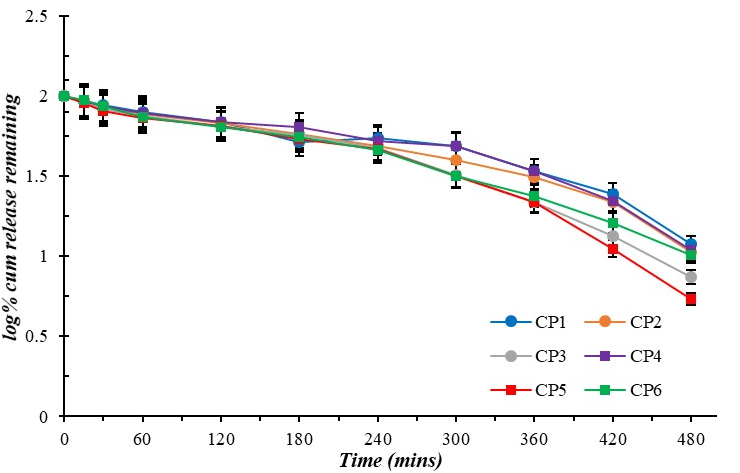

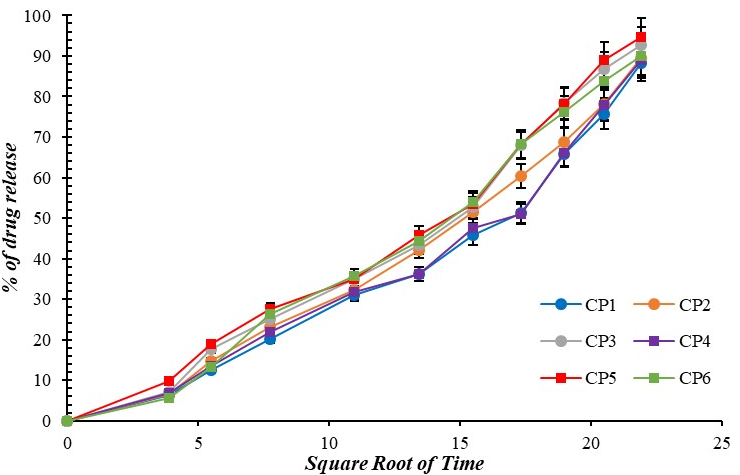

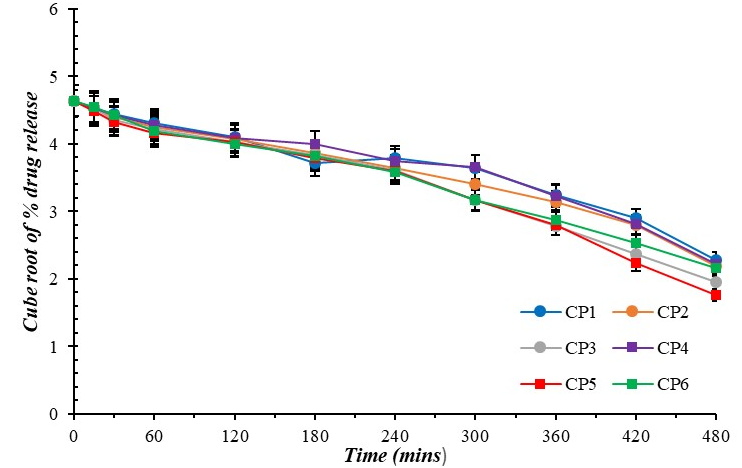

Kinetic profiling

Maximum slope range was observed between 3.8 to 4.4 for all microgel formulations under the Higuchi release model. Meanwhile, the minimum slow range was in almost zero (0.001-0.002) for microgel formulations under First Order kinetics. The kinetic models are shown in fig. 10 to fig. 14.

Fig. 10: Zero order kinetics for curcumin-loaded microgel formulations (CP1-CP6). Error bars indicate SD values

Fig. 11: First order kinetics for curcumin-loaded microgel formulations (CP1-CP6). Error bars indicate SD values

Fig. 12: Higuchi diffusion model for curcumin-loaded microgel formulations (CP1-CP6), Error bars indicate SD values

Fig. 13: Hixson-crowell plot for curcumin-loaded microgel formulations (CP1-CP6), error bars indicate SD values

Fig. 14: Korsmeyer-peppas plot for curcumin-loaded microgel formulations (CP1-CP6). Error bars indicate SD values

The Release exponent (n) of the optimized formulation (CP5) was calculated to be 0.707. This indicates anomalous transport (0.43<n<0.85) and is also the best fit (R2=0.985) for the optimized batch (CP5) compared to Hixson-Crowell (R2=0.975) and Higuchi plots (R2=0.971).

Evaluation studies for optimized formulation

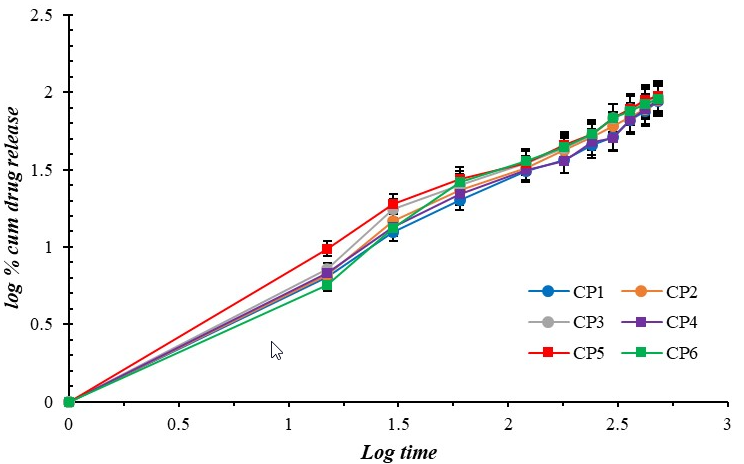

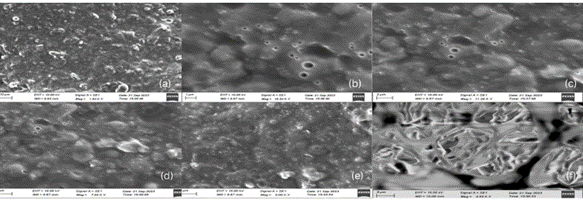

SEM

SEM Analysis for the optimized formulation (CP5) depicted the globule size in the range of 5-10 µm. Most of the lipophilic encapsulated globules were spherical or ovoid. The SEM images at different resolutions for the optimized formulation (CP5) are sequentially displayed in fig. 15.

At lower magnifications (e. g., images (a) and (d)), the surface appears rough and heterogeneous, indicating that the formation of microgels leads to a non-uniform surface. Image (c) displays some level of particle aggregation, which may indicate that the microgel particles tend to clump together. This could potentially hinder drug release by limiting the effective surface area available for interaction with the surrounding medium. However, the compact and denser regions observed in image (f) suggest strong crosslinking or polymer network formation. Crosslinking density can influence the release rate of curcumin by controlling the network's ability to swell and release the drug.

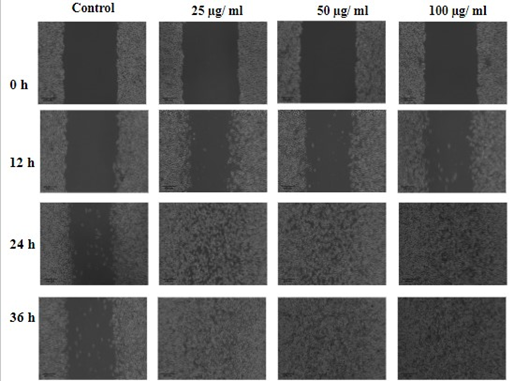

In vitro cell line studies

The wound was clearly visible with a dark black background. Furthermore, the cell migration rate was almost close to zero even after 24 h in control group. However, cell migration rate increased significantly after 24 h at all concentrations of optimized Curcumin loaded pumpkin seed microgel formulation (CP5). By the end of 36th h, the wound area was nil at 50 µg/ml and 100 µg/ml. It was also observed that the Minimum Effective Concentration (MEC) promoting complete wound healing within the predetermined time was observed to be 50µg/ml. The photomicrographs of wound healing are shown collectively in fig. 16.

Fig. 15: Scanning electron microscopic images for the optimized microgel (CP5) at (a) 1.94 kx, (b) 16.54 kx, (c) 11.26 kx, (d) 7.99 kx, (e) 5.00 kx, (f) 4.98 kx

Table 5: Average wound area of L6 cell line (Rat skeletal muscle) over period of time for the optimized microgel (CP5)

| Concentration | Average wound area (Arbitrary units) | |||

| 0 h | 12 h | 24 h | 36 h | |

| Control | 37 | 34.9 | 26.5 | 25 |

| 25µg/ml | 37 | 27.6 | 8.2 | 2 |

| 50µg/ml | 37 | 27.6 | 5.1 | 0 |

| 100µg/ml | 37 | 27.2 | 2.1 | 0 |

The wound healing activity of curcumin hydrogel were statistically significant (p<0.05) in Friedman’s test indicating at least one pair of treatment groups showed statistically significant difference. In order to identify the groups, pairwise comparisons were performed by Durbin-Conover test, which exhibited statistically significant difference (p<0.05) at all concentrations except 25µg/ml with control. The Z-score and p-value are shown in Durbin-Conover test is shown in table 5.

Fig. 16: Cell migration rate of L6 cell line under control and different microgel concentrations (25, 50 and 100 μg/ml), the wound healing rate based on concentration of microgel is expressed in table 5

Table 6: Pairwise comparisons of treatment groups for the optimized formulation (CP5) in Durbin-Conover test. The symbol *indicates the statistically significant difference between the treatment groups

| Treatment group-1 | Treatment group-2 | Z-score | P-value |

| Control | 25 µg/ml | 1.83 | 0.101 |

| Control | 50 µg/ml | 3.13 | 0.012* |

| Control | 100 µg/ml | 4.44 | 0.002* |

| 25 µg/ml | 50 µg/ml | 1.31 | 0.224 |

| 25 µg/ml | 100 µg/ml | 2.61 | 0.028* |

| 50 µg/ml | 100 µg/ml | 1.31 | 0.224 |

*p<0.05

Stability studies

The percentage deviation of assay and disintegration time was not more than 3% and 5 seconds respectively when stored under temperatures of 40±2 °C and 75±5% RH. This indicates the physical and chemical quality of optimized curcumin microgel formulation (CP5). The stability studies conducted for the optimized formulation (CP5) is tabulated in table 7.

Table 7: Stability studies of the optimized microgel formulation (CP5)

| S. No. | Tests | Initial | 1 Mo | 2 Mo | 3 Mo |

| 1 | Colour | Yellow | Yellow | Yellow | Yellow |

| 2 | Odour | Pleasant | Pleasant | Pleasant | Pleasant |

| 3 | Nature | Opaque | Opaque | Opaque | Opaque |

| 4 | pH | 6.0±0.5 | 6.0±0.55 | 5.8 ±0.3 | 5.7±0.4 |

| 5 | Viscosity | 16000±500 | 15500±620 | 15000±580 | 14000 ±600 |

| 6 | Spreadability (g. cm/sec) | 22.03±1.38 | 22.1 ±1.67 | 21.01 ±1.82 | 20.22 ±2.01 |

| 7 | Extrudability (kPa) | 48.88 ±12.50 | 45.36 ±13.05 | 43.13±12.68 | 38.27±12.99 |

| 8 | Assay (%) | 98.22 ±1.80% | 97.78 ±2.06% | 97.76 ±2.35% | 97.11±02.72% |

Results are expressed as mean±SD, n=3.

DISCUSSION

All the microgel formulations (CP1-CP6) were yellow, viscous, lumpless formulations with smooth texture and zero transparency [6, 7, 44]. In this current research, we developed microgel containing curcumin with variation in concentrations between two swelling agents: Sodium Alginate and Carbopol-934. The API was encapsulated with the lipophilic substance. Pumpkin seed oil was considered for this encapsulation purpose, because it also possesses a hemostatic effect, thereby effectively assisting in wound healing [14, 45].

Prior to the development of microgel, a series of preformulation examinations was conducted. The solubility of curcumin was similar to Zheng et al. [45]. Lipophilic nature of the curcumin made it difficult to dissolve in aqueous media, confirming the quality of the API. When dissolved in organic solvents, it exhibited yellow colour without precipitating. The lack of orange colour shows that the API was not auto-oxidised. Because, auto oxidised product of curcumin (Bicyclopentadione) is an orange colour compound and is similar in solubility, but can be differentiated from the colour shade [45, 46].

The UV graph of pure curcumin in ethanol was similar to that of methanol, however a mild hypsochromic shift was observed. Because the lambda Max of curcumin in methanol was in the range of 420-422 nm. Besides, the UV spectrum obtained in this study complied with Mondal et al, which described the maximum shift in the blue wavelength range under DMSO [47-49].

The peak near 958 cm⁻1 is associated with the out-of-plane bending of C–H bonds in the enol form of curcumin, a common feature in its tautomeric forms. Besides, ATR-FTIR studies confirmed the aromatic hydroxyl group around 3500 cm-1. This is due to the conjugation of hydroxyl groups with aromatic rings farming extensive hydrogen bonding which is both intramolecular and intermolecular in nature [50-52].

On the contrary, β-di-ketone moiety was confirmed by showing a peak in the range of 1625-1650 cm-1. However, the compound does not exist in keto form since the reported peak in the mentioned range was faint. Furthermore, the transmittance of the di-keto form peak (>85%) was higher than that of enolic bond (<80%). However, it does suggest that there is single ketone group considering the C=O Stretching [53-56]. Ethereal and aromatic moieties were confirmed by C-O stretching (1573 cm-1) and C=C stretching (1266 cm-1) respectively [57, 58].

Lipophilic encapsulation was performed for the API with pumpkin seed oil. Swelling is a basic important phenomenon by which the API can be effectively released into the wound. Hence, variation in the type and concentration of swelling agents is given [59].

Particle size is a critical factor for the bioavailability and stability of curcumin. Smaller particles tend to possess increased surface area and enhance the interaction with biological tissues, which could enhance the absorption of curcumin [60] Structural integrity is excellent when the microparticles within the gel lie in the particle size range between 500 to 1500 nm [61, 62].

The Zeta potential of the microgel followed a decline with successive formulation batch (CP1-CP6). The microgel performed using Sodium Alginate as swelling agent exhibited poor zeta potential at low concentrations. However, sodium alginate at a concentration of 1.5% showed a drastic improvement in the electronegativity of the microgel formulation (CP3). Sodium alginate did not help in increasing the electronegativity. This indicates the deflocculated state. Generally, deflocculation is an ideal property for certain semi-solid dosage formulations including gels. Because, it helps in the maintenance of texture, content uniformity and physical stability. Furthermore, it prevents aggregation of microparticles from clumping. Consistency in gel formulation may be considered as an indirect parameter of the zeta potential. As a result, CP5 exhibited the most ideal consistency and visual perfection after formulation stage [63, 64]. Generally, decrease in intensity of zeta potential (<±10mV) leads to increase in viscosity. Because, formation of big particles occur upon collision of smaller particles due to poor electrostatic repulsion. The relationship between zeta potential and viscosity is clearly established in the Henry equation. While, electrophoretic mobility has a direct relationship with zeta potential, it has an inverse relationship with viscosity [65, 66].

The optimal pH range of skin is generally between 4.1 and 5.8 depending on the region of the body. For instance, the skin pH on the forearm (5.4-5.9) is slightly acidic compared to toe inter digits (6.1-7.4). This is due to difference in acidic microdomains [67]. Besides, presence of alkaline pH in skin can generally lead to wound infections. This is caused mainly due to presence of blood, ammonia and other compounds which are alkaline in nature. The active nature of certain tissue degrading enzymes like elastase at alkaline pH ranges further retards the wound healing [68]. This research formulated curcumin microgel in accordance with skin pH. When applied to the wounds, other than the therapeutic action of the API, the pH of the microgel will prevent the growth of major microorganisms which grow at alkaline pH [69]. The pH must not be too acidic (pH<4), since, it may cause disruption of acid mantle of the skin by reducing the pH below the optimal range. As a result, clinical symptoms like redness of skin, pruritus, sensitivity occurs and causes progression of wound formation, instead of healing the wound [70, 71]. Triethanolamine (TEA) acts as pH stabilizer to adjust the formulation to slightly acidic state in which the wound healing is improved [72].

Viscosity is defined as the internal resistance of the particle to flow. This may impact on both extrudability and spreadability. However, application of external force may impact on these parameters beyond a threshold limit. Rigid network within the microgel formulation was present in CP1. Despite expression of least viscosity (13000 cps), CP6 failed to express the maximum spreadability. This infers that CP6 exhibited dilatant flow with thixotropic behaviour. The microgel formulation with the highest spreadability (CP5) was neither a pseudoplastic nor a Bingham fluid. This confirms that the microgel formulation behaves like a liquid upon applying pressure of predetermined mass. Besides, the geometric increase in extrudability for microgel formulations indicate that the employed swelling agent improves the dilatant flow in the formulation [73, 74]. The viscosity of the microgel in this research was in accordance with existing literature [75]. This high viscosity is highly necessary for impeding the run-off from the affected site. Besides, high viscosity of microgels is an ideal factor for providing sustained release, since it retards the drying rate [76]. Even though, high viscosity can cause an inconvenience in ease of application, the spreadability of CP5 was sufficiently good to overcome this problem [77]. Besides, patient counselling on sustained release microgels must be provided by the medical professionals. This must be focused on the reduction in administration frequency and the long-term support in wound healing by such microgels [78].

There was no major difference between the microgel formulation (CP1-CP6) showing a consistent diffusion with drug release>80%. The drug release of curcumin over time was relatively similar irrespective of the type and concentration of swelling agents. Patil et al. had reported that the diffusion rate of the drug was inversely proportional to the concentration of sodium alginate (swelling agent). A reduction in porosity of the biopolymeric swelling agent occurs when viscosity enhances, leading to a rigid network within the microgel [79, 80]. Other than the polymers, the pumpkin seed oil itself is an efficient release retardant and thus helps in preparation of sustained release formulations. Heikal et al. has successfully employed pumpkin seed oil as an encapsulating agent for sustained release of Atorvastatin in breast cancer therapy [81]. Pumpkin seed oil was also used in controlled release of UV filters and an antioxidant [82].

Nevertheless, the same theoretical aspect was applicable even in oral dosage forms and intranasal dosage forms [83, 84].

Contrary to Patil et al., this research shows a consistent release throughout the time. Lipophilic encapsulation of curcumin plays the major role in sustained release of the drug over a period of 8 h. Because, dissolution of the lipophilic shell takes place after which the drug is diffused slowly across the semipermeable membrane [79, 85].

The slow and sustained release with maximum drug release over 80% may be due to a low Flory-Huggins parameter (χ<0.5). The poor Flory-Huggins parameter (χ) can be confirmed by the high compatibility between biopolymer and Curcumin by ATR-FTIR studies. Because, no characteristic peak of curcumin disappeared upon mixing with polymer and other excipients [80, 81]. Sustained release of a drug depends on the electric charge of the polymer involved in the microgel formulations. Carbopol is capable of producing a more negative charged formulation compared to sodium alginate. This produces slow and sustained release through electrostatic interactions between the drug and carbopol [82, 83]. The optimized microgel formulation (CP5) followed an anomalous drug transport by non-fickian diffusion mechanism with a moderate release exponent (n=0.707), which is accordance with existing literature [86]. This diffusion is possible due to glassy polymer (Carbopol), which is converted to a rubbery texture under the presence of aqueous medium. This transitional mechanism leads to swelling of polymer. This retards the release rate and allows drug release in a sustained manner [87, 88]. Surface erosion mechanism is not possible since it occurs when the polymer is hydrophobic in nature [89].

There were no significant large cracks in the analysis of the optimised formulation (CP5) through SEM. This confirms the structural stability of lipophilic encapsulated in microparticles. The SEM results of this research were contrary to Sinha et al., which had reported spherical particles using sodium alginate without agglomeration. Moreover, both optimised microgel (CP5) and reported mucoadhesive beads followed zero order kinetics [90-92]. Aggregation of particles tend to slow down the drug release due to the reduction of surface area of the particles. In such cases, prolonged release kinetics is observed [91]. The quality of the sustained release can be verified using diffusion constant. Because, the diffusion constant decreases with decrease in surface area of particle. Ortiz et al. experienced particle agglomeration of small particles in the prepared formulation of Nanostructured Lipid Carrier containing Rhodamine 123. This expressed lesser release exponent (n=0.49) than that of this research (n=0.707). This indicates that particle agglomeration can possibly affect the drug release kinetics of the optimized microgel formulation (CP5). Future research must focus on reducing the risk of particle agglomeration such that it does not affect drug release kinetics [93, 94].

In vitro wound healing activity of the optimized microgel formulation (CP5) was similar to that of catholyte electrolysed water and exhibited better wound healing activity than that of slightly acidic electrolysed water [95]. Partial mediation of Dickkopf-1 (DKK-1) may be a possible factor for influencing the excellent wound healing activity of this optimised microgel. Besides, it is known for reducing inflammation by inhibiting Cycoloxygenase-II (COX-II) signaling. This will influence on Dkk-1 pathway through impact on Wingless-related integration site (Wnt) signaling. DKK-1, which inhibits wound healing, is inhibited by COX-II inhibition. This leads to prevention of growth suppression of epidermal melanocytes [22, 96]. These cells help in accelerated wound healing [97]. The pumpkin seed oil may provide a synergistic activity along with the API (Curcumin) by also promoting anti-inflammatory activity due to the presence of γ-tocopherol. Because, it promotes anti-inflammatory activity through Interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (TNF-α). As a result, it can potentially accelerate diabetic wound closure [98]. Limitations of this research include the wound healing assay being performed on a single cell line. Besides, cytotoxicity studies were not performed for understanding the safety of the formulation, since, the main objective was to provide the therapeutic efficacy. Hence, future studies must not be confined to a single cell line. However, pharmacodynamic studies and cytokine profiling in animal models and diabetic models must be performed to establish the confirmation of theoretical evidence behind the mechanism of wound healing activity of this microgel model [99, 100].

CONCLUSION

Encapsulated microgel is one of the emerging formulations in which the active pharmaceutical ingredient having the drawback is addressed by effective encapsulation of inert or therapeutically active lipophilic substance. The lipophilic compound aids in the enhanced permeation of API across dermal barriers and also assists in wound healing. While microgels generally focus on the permeability of drug across skin, this research focused on lipophilic encapsulation which is not restricted to a single factor (pH, temperature, etc.), but is naturally responsive to produce a synergistic effect on wound healing. However, future research can be performed on in vivo models to understand and confirm the mechanism of action behind the synergistic activity of pumpkinseed oil and curcumin in wound healing. Furthermore, cytotoxicity studies can help us interpret the safety nature of the formulation. It can be concluded that pumpkin seed oil plays a synergistic role in wound healing by successfully encapsulating Curcumin in the microgel formulation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We would like to sincerely thank our Registrar of VMRF (DU), Dr. A. Nagappan, for his immense support. We would also extend our sincere thanks to our Principal of Vinayaka Mission's College of Pharmacy, Prof. Kumar Mohan, for providing facilities and amenities for carrying out the research study.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Margret Chandira Rajappa–Conceptualization and approval of final draft, Ajith Kannan–Methodology, Writing initial draft, Nagasubramanian Venkatasubramaniam–Data Interpretation, Statistical analysis, reviewing and editing, Lokesh Venkatachalam–Prepared initial draft, Data Analysis, Selvaragavan Karnan–Methodology, Data Analysis, Dominic Antonysamy–Study Design, Statistical analysis.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Cui T, Yu J, Wang CF, Chen S, Li Q, Guo K. Micro‐gel ensembles for accelerated healing of chronic wound via pH regulation. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2022;9(22):e2201254. doi: 10.1002/advs.202201254, PMID 35596608.

Ferreira MC, Tuma P, Carvalho VF, Kamamoto F. Complex wounds. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2006;61(6):571-8. doi: 10.1590/s1807-59322006000600014, PMID 17187095.

Guo B, Dong R, Liang Y, Li M. Haemostatic materials for wound healing applications. Nat Rev Chem. 2021;5(11):773-91. doi: 10.1038/s41570-021-00323-z, PMID 37117664.

Criollo Mendoza MS, Contreras Angulo LA, Leyva Lopez N, Gutierrez Grijalva EP, Jimenez Ortega LA, Heredia JB. Wound healing properties of natural products: mechanisms of action. Molecules. 2023;28(2):598. doi: 10.3390/molecules28020598, PMID 36677659.

Holzer Geissler JC, Schwingenschuh S, Zacharias M, Einsiedler J, Kainz S, Reisenegger P. The impact of prolonged inflammation on wound healing. Biomedicines. 2022;10(4):856. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10040856, PMID 35453606.

Hussain Y, Alam W, Ullah H, Dacrema M, Daglia M, Khan H. Antimicrobial potential of curcumin: therapeutic potential and challenges to clinical applications. Antibiotics (Basel). 2022;11(3):322. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11030322, PMID 35326785.

Olas B. The antioxidant anti-platelet and anti-coagulant properties of phenolic compounds associated with modulation of hemostasis and cardiovascular disease and their possible effect on COVID-19. Nutrients. 2022;14(7):1390. doi: 10.3390/nu14071390, PMID 35406002.

Kumari A, Raina N, Wahi A, Goh KW, Sharma P, Nagpal R. Wound healing effects of curcumin and its nanoformulations: a comprehensive review. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14(11):2288. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14112288, PMID 36365107.

Bardaa S, Moalla D, Ben Khedir SB, Rebai T, Sahnoun Z. The evaluation of the healing proprieties of pumpkin and linseed oils on deep second degree burns in rats. Pharm Biol. 2016;54(4):581-7. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2015.1067233, PMID 26186459.

Reiter E, Jiang Q, Christen S. Anti-inflammatory properties of α-and γ-tocopherol. Mol Aspects Med. 2007 Jan 13;28(5-6):668-91. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2007.01.003.

Liu S, Liu J, He L, Liu L, Cheng B, Zhou F. A comprehensive review on the benefits and problems of curcumin with respect to human health. Molecules. 2022 Jul 8;27(14):4400. doi: 10.3390/molecules27144400, PMID 35889273.

Keihanian F, Saeidinia A, Bagheri RK, Johnston TP, Sahebkar A. Curcumin hemostasis thrombosis and coagulation. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233(6):4497-511. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26249, PMID 29052850.

Hamilton AE, Gilbert RJ. Curcumin release from biomaterials for enhanced tissue regeneration following injury or disease. Bioengineering (Basel). 2023 Feb 16;10(2):262. doi: 10.3390/bioengineering10020262, PMID 36829756.

Bardaa S, Ben Halima N, Aloui F, Ben Mansour R, Jabeur H, Bouaziz M. Oil from pumpkin (Cucurbita pepo L.) seeds: evaluation of its functional properties on wound healing in rats. Lipids Health Dis. 2016 Apr 11;15:73. doi: 10.1186/s12944-016-0237-0, PMID 27068642.

Simo G, Fernandez Fernandez E, Vila Crespo J, Ruiperez V, Rodriguez Nogales JM. Research progress in coating techniques of alginate gel polymer for cell encapsulation. Carbohydr Polym. 2017 Aug 15;170:1-14. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.04.013, PMID 28521974.

Plamper FA, Richtering W. Functional microgels and microgel systems. Acc Chem Res. 2017;50(2):131-40. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00544, PMID 28186408.

Hu C, Van Bonn P, Demco DE, Bolm C, Pich A. Mechanochemical synthesis of stimuli responsive microgels. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2023;62(34):e202305783. doi: 10.1002/anie.202305783, PMID 37177824.

Oberdisse J, Hellweg T. Recent advances in stimuli responsive core shell microgel particles: synthesis characterisation and applications. Colloid Polym Sci. 2020;298(7):921-35. doi: 10.1007/s00396-020-04629-0.

Sharma JB, Sherry S, Bhatt S, Saini V, Kumar M. Development and validation of UV-visible spectrophotometric method for the estimation of curcumin and tetrahydrocurcumin in simulated intestinal fluid. Res J Pharm Technol. 2021;14(6):2971-5. doi: 10.52711/0974-360X.2021.00520.

Hazra K, Kumar R, Sarkar BK, Chowdary YA, Devgan M, Ramaiah M. UV-visible spectrophotometric estimation of curcumin in nanoformulation. Int J Pharmacogn. 2015;2(3):127-30. doi: 10.13040/IJPSR.0975-8232.IJP.2(3).127-30.

Khan MI, Madni MA, Ahmad S, Khan A. ATR-FTIR based pre and post formulation compatibility studies for the design of Niosomal drug delivery system containing nonionic amphiphiles and chondroprotective drug. J Chem Soc Pak. 2015;37(3):527-33.

Torres O, Murray B, Sarkar A. Emulsion microgel particles: novel encapsulation strategy for lipophilic molecules. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2016 Sep;55:98-108. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2016.07.006.

Shukla SK, Sharma AK, Gupta V, Yashavarddhan MH. Pharmacological control of inflammation in wound healing. J Tissue Viability. 2019 Sep 14;28(4):218-22. doi: 10.1016/j.jtv.2019.09.002, PMID 31542301.

Petrochenko PE, Pavurala N, Wu Y, Yee Wong S, Parhiz H, Chen K. Analytical considerations for measuring the globule size distribution of cyclosporine ophthalmic emulsions. Int J Pharm. 2018;550(1-2):229-39. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.08.030, PMID 30125649.

Echlin P. Handbook of sample preparation for scanning electron microscopy and X-ray microanalysis. 1st ed. Berlin: Springer; 2011. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-85731-2.

Zhang Z, Zhang R, Zou L, Mc Clements DJ. Protein encapsulation in alginate hydrogel beads: effect of pH on microgel stability protein retention and protein release. Food Hydrocoll. 2016 Jul 1;58:308-15. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2016.03.015.

Feng R, Wang L, Zhou P, Luo Z, Li X, Gao L. Development of the pH responsive chitosan alginate based microgel for encapsulation of Jughans regia L. polyphenols under simulated gastrointestinal digestion in vitro. Carbohydr Polym. 2020 Dec;250:116917. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116917, PMID 33049889.

Ching SH, Bansal N, Bhandari B. Rheology of emulsion filled alginate microgel suspensions. Food Res Int. 2016 Feb;80:50-60. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2015.12.016.

Yadav P, Shah S, Tyagi CK. Formulation and evaluation of tinidazole microgel for skin delivery. Res J Top Cosmet Sci. 2021;12(1):43-50. doi: 10.52711/2321-5844.2021.00007.

Reddy Hv R, Bhattacharyya S. In vitro evaluation of mucoadhesive in situ nanogel of celecoxib for buccal delivery. Ann Pharm Fr. 2021;79(4):418-30. doi: 10.1016/j.pharma.2021.01.006, PMID 33515589.

Bhanja S, Kumar PK, Sudhakar M, Das AK. Formulation and evaluation of diclofenac transdermal gel. J Adv Pharm Educ Res. 2013;3(3):248-59. doi: 10.51847/xNRLNxi.

Patel HK, Barot BS, Parejiya PB, Shelat PK, Shukla A. Topical delivery of clobetasol propionate loaded microemulsion based gel for effective treatment of vitiligo: ex vivo permeation and skin irritation studies. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2013 Feb 1;102:86-94. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2012.08.011, PMID 23000677.

Kamath PP, Rajeevan R, Maity S, Nayak Y, Narayan R, Mehta CH. Development of nanostructured lipid carriers loaded caffeic acid topical cream for prevention of inflammation in Wistar rat model. J App Pharm Sc. 2022 Jan 1;13(1):64-75. doi: 10.7324/JAPS.2023.130106-1.

Proksch E. pH in nature humans and skin. J Dermatol. 2018 Jun 4;45(9):1044-52. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.14489, PMID 29863755.

Paarakh MP, Jose PA, Setty CM, Peterchristoper GV. Release kinetics-concepts and applications. Int Res J Pharm Technol. 2018;8(1):12-20. doi: 10.31838/ijprt/08.01.02.

Costa P, Sousa Lobo JM. Modeling and comparison of dissolution profiles. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2001;13(2):123-33. doi: 10.1016/s0928-0987(01)00095-1, PMID 11297896.

Patra D, Sleem F. A new method for pH triggered curcumin release by applying poly(l-lysine) mediated nanoparticle congregation. Anal Chim Acta. 2013 Aug 2;795:60-8. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2013.07.063, PMID 23998538.

Sharma M, Inbaraj BS, Dikkala PK, Sridhar K, Mude AN, Narsaiah K. Preparation of curcumin hydrogel beads for the development of functional KULFI: a tailoring delivery system. Foods. 2022 Jan 11;11(2):182. doi: 10.3390/foods11020182, PMID 35053917.

Chester D, Kathard R, Nortey J, Nellenbach K, Brown AC. Viscoelastic properties of microgel thin films control fibroblast modes of migration and pro-fibrotic responses. Biomaterials. 2018 Dec;185:371-82. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.09.012, PMID 30292092.

Li S, Dou W, Ji W, Li X, Chen N, Ji Y. Tissue adhesive stretchable and compressible physical double crosslinked microgel integrated hydrogels for dynamic wound care. Acta Biomater. 2024 Aug;184:186-200. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2024.06.030, PMID 38936752.

FZ, RR, KS. A review on stability testing guidelines of pharmaceutical products. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2020;13(10):3-9. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2020.v13i10.38848.

Chandira RM, Pethappachetty P, Venkatasubramaniam N, Antony Samy D. Formulation and comparison of glucomannan metallocomplexes made of cobalt and copper. Asian J Biol Life Sci. 2022;11(2):564-9. doi: 10.5530/ajbls.2022.11.76.

Akbik D, Ghadiri M, Chrzanowski W, Rohanizadeh R. Curcumin as a wound healing agent. Life Sci. 2014;116(1):1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2014.08.016, PMID 25200875.

Jin MJ, Han HK. Improvement of oral bioavailability of curcumin via a novel solid lipid based nanosuspension system. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2010;20:77-81.

Zheng B, Mc Clements DJ. Formulation of more efficacious curcumin delivery systems using colloid science: enhanced solubility stability and bioavailability. Molecules. 2020;25(12):2791. doi: 10.3390/molecules25122791, PMID 32560351.

Kadam PV, Bhingare CL, Nikam RY, Pawar SA. Development and validation of UV spectrophotometric method for the estimation of curcumin in cream formulation. Pharm Methods. 2013;4(2):43-5. doi: 10.1016/j.phme.2013.08.002.

Sharma M, Gulati D, Kamboj A, Arora S. Simultaneous estimation of curcumin and gentamicin by UV-vis spectrometric methods or derivative spectroscopic techniques. Biomed Pharmacol J. 2023;16(4):2283-91. doi: 10.13005/bpj/2804.

Mondal S, Ghosh S, Moulik SP. Stability of curcumin in different solvent and solution media: UV-visible and steady state fluorescence spectral study. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2016 May;158:212-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2016.03.004, PMID 26985735.

Gopi S, Amalraj A, Varma K. Curcumin and its formulations: a review of past decade research. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2020;11(12):5830-45.

Ahmed K, Li Y, Mc Clements DJ. Nanoemulsion and emulsion based delivery systems for curcumin: encapsulation and release properties. Food Hydrocoll. 2020;87:104449. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2018.08.037.

Suresh D, Gurudatt NG, Umesh M. Curcumin based formulations: infra-red spectroscopic investigation and in vitro evaluation of their chemopreventive potential. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2020;115:703-7.

Sharma RA, Steward WP, Gescher AJ. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of curcumin. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;595:453-70. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-46401-5_20, PMID 17569224.

Zhang H, Lin R, Zhang Y. Curcumin loaded nanoparticles for enhanced anti-cancer effects and physicochemical stability: ATR-FTIR and DSC studies. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2021;120:111774.

Anand P, Sundaram C, Jhurani S, Kunnumakkara AB, Aggarwal BB. Curcumin and cancer: an ‘old-age’ disease with an ‘age-old’ solution. Cancer Lett. 2008;267(1):133-64. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.03.025, PMID 18462866.

Torres O, Murray B, Sarkar A. Emulsion microgel particles: novel encapsulation strategy for lipophilic molecules. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2016 Sep;55:98-108. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2016.07.006.

Yallapu MM, Jaggi M, Chauhan SC. Curcumin nanoformulations: a future nanomedicine for cancer. Drug Discov Today. 2012;17(1-2):71-80. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2011.09.009, PMID 21959306.

Allen TM, Cullis PR. Liposomal drug delivery systems: from concept to clinical applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013;65(1):36-48. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.09.037, PMID 23036225.

Cerra S, Salamone TA, Sciubba F, Marsotto M, Battocchio C, Nappini S. Study of the interaction mechanism between hydrophilic thiol capped gold nanoparticles and melamine in aqueous medium. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2021 Jul;203:111727. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2021.111727, PMID 33819818.

Dixit N, Malipeddi VR. Effect of charge on drug encapsulation and release kinetics from microgels. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2021;12(5):2305-12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsr.2021.01.004.

Meenach SA, Anderson KW, Hilt JZ. Sustained release drug delivery from thermosensitive microgels. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2010;74(2):243-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2009.10.010.

Kosmulski M, Maczka E. Zeta potential and particle size in dispersions of alumina in 50-50 w/w ethylene glycol-water mixture. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects. 2022 Sep 13;654:130168. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2022.130168.

Wang H, Adeleye AS, Huang Y, Li F, Keller AA. Heteroaggregation of nanoparticles with biocolloids and geocolloids. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2015 Jul 22;226(A):24-36. doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2015.07.002, PMID 26233495.

Lukic M, Pantelic I, Savic SD. Towards optimal pH of the skin and topical formulations: from the current state of the art to tailored products. Cosmetics. 2021 Aug 4;8(3):69. doi: 10.3390/cosmetics8030069.

Das IJ, Bal T. pH factors in chronic wound and pH-responsive polysaccharide based hydrogel dressings. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024 Aug 28;279(1):135118. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.135118, PMID 39208902.

Jones EM, Cochrane CA, Percival SL. The effect of pH on the extracellular matrix and biofilms. Adv Wound Care. 2015;4(7):431-9. doi: 10.1089/wound.2014.0538, PMID 26155386.

Safitri FI, Nawangsari D, Febrina D. Overview: application of carbopol 940 in gel. Adv Health Sci Res. 2021 Jan 1;34:80-4. doi: 10.2991/ahsr.k.210127.018.

Mijaljica D, Townley JP, Klionsky DJ, Spada F, Lai M. The origin intricate nature and role of the skin surface pH (PHSS) in barrier integrity eczema and psoriasis. Cosmetics. 2025 Feb 3;12(1):24. doi: 10.3390/cosmetics12010024.

Nnamani P, Kenechukwu F, Okoye C, Attama A. Surface engineered oral sub-micron particles and topical microgels matrixed with transcutol-HP/Capra hircus composite for amplification of piroxicam delivery and anti-inflammatory activity. Lett Appl Nanobiosci. 2024 Mar 30;13(1):15. doi: 10.33263/LIANBS131.015.

Ansel HC, Popovich NG, Allen LV. Pharmaceutical dosage forms and drug delivery systems. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011.

Manavalan R, Ramasamy C. Physical pharmaceutics. 11th ed. Hyderabad: Pharmamed Press; 2017.

PP, MP, KM, Rkkvv S, NT. Formulation and evaluation of tylophora indica extract loaded topical herbal microgel for rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Drug Deliv Technol. 2024 Dec;14(4):1139-47. doi: 10.25258/ijddt.14.4.31.

Binder L, Mazal J, Petz R, Klang V, Valenta C. The role of viscosity on skin penetration from cellulose ether based hydrogels. Skin Res Technol. 2019 May 6;25(5):725-34. doi: 10.1111/srt.12709, PMID 31062432.

Oliveira R, Almeida IF. Patient centric design of topical dermatological medicines. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2023 Apr 19;16(4):617. doi: 10.3390/ph16040617, PMID 37111373.

Mu Y, Zhao L, Shen L. Medication adherence and pharmaceutical design strategies for pediatric patients: an overview. Drug Discov Today. 2023 Sep 13;28(11):103766. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2023.103766, PMID 37708932.

Patil PB, Chaudhari PD. Formulation and evaluation of mucoadhesive microspheres of propranolol hydrochloride using sodium alginate. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2015;7(9):421-6.

McClements DJ. Designing biopolymer microgels to encapsulate protect and deliver bioactive components: physicochemical aspects. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2017 Feb;240:31-59. doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2016.12.005, PMID 28034309.

Heikal LA, Ashour AA, Aboushanab AR, El Kamel AH, Zaki II, El Moslemany RM. Microneedles integrated with atorvastatin loaded pumpkisomes for breast cancer therapy: a localized delivery approach. J Control Release. 2024 Oct 19;376:354-68. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2024.10.013, PMID 39413849.

Lacatusu I, Arsenie LV, Badea G, Popa O, Oprea O, Badea N. New cosmetic formulations with broad photoprotective and antioxidative activities designed by amaranth and pumpkin seed oils nanocarriers. Ind Crops Prod. 2018 Jul 17;123:424-33. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2018.06.083.

Madhavi BR, Murthy TE, Rani AP. Design and evaluation of controlled release oral matrix tablet formulations of zidovudine using hydrophilic polymers. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2011;3(3):101-6.

Jaiswal M, Kumar A, Sharma S. Nanoemulsions loaded carbopol® 934 based gel for intranasal delivery of neuroprotective Centella asiatica extract: in vitro and ex-vivo permeation study. J Pharm Investig. 2016;46(1):79-89. doi: 10.1007/s40005-016-0228-1.

Popova EV, Morozova PV, Uspenskaya MV, Radilov AS. Sodium alginate and carbopol microcapsules: preparation polyphenol encapsulation and release efficiency. Russ Chem Bull. 2021;70(7):1335-40. doi: 10.1007/s11172-021-3220-5.

Smith PA. Carbon fiber reinforced plastics properties. In: Kelly A, Zweben C, editors. Comprehensive composite materials. Oxford: Elsevier; 2000. p. 107-50. doi: 10.1016/B0-08-042993-9/00072-3.

Suhail M, Vu QL, Wu PC. Formulation characterization and in vitro drug release study of Β-cyclodextrin based smart hydrogels. Gels. 2022;8(4):207. doi: 10.3390/gels8040207, PMID 35448108.

Singh B, Singh J, Sharma V, Sharma P, Kumar R. Functionalization of bioactive moringa gum for designing hydrogel wound dressings. Hybrid Advances. 2023 Dec;4:100096. doi: 10.1016/j.hybadv.2023.100096.

Song Z, Wen Y, Teng F, Wang M, Liu N, Feng R. Carbopol 940 hydrogel containing curcumin loaded micelles for skin delivery and application in inflammation treatment and wound healing. New J Chem. 2022 Jan 1;46(8):3674-86. doi: 10.1039/D1NJ04719A.

Ali HH, Hussein AA. Oral nanoemulsions of candesartan cilexetil: formulation characterization and in vitro drug release studies. AAPS Open. 2017 Jun 2;3(1):2-16. doi: 10.1186/s41120-017-0016-7.

Gomez Carracedo A, Alvarez Lorenzo C, Gomez Amoza JL, Concheiro A. Glass transitions and viscoelastic properties of Carbopol® and Noveon® compacts. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 2004;274(1-2):233-43. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2004.01.023.

Varma MV, Kaushal AM, Garg A, Garg S. Factors affecting mechanism and kinetics of drug release from matrix-based oral controlled drug delivery systems. Am J Drug Deliv. 2004 Jan 1;2(1):43-57. doi: 10.2165/00137696-200402010-00003.

Kamaly N, Yameen B, Wu J, Farokhzad OC. Degradable controlled release polymers and polymeric nanoparticles: mechanisms of controlling drug release. Chem Rev. 2016 Feb 8;116(4):2602-63. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00346, PMID 26854975.

Kelly SM, Upadhyay AK, Mitra A, Narasimhan B. Analyzing drug release kinetics from water soluble polymers. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2019;58(18):7428-37. doi: 10.1021/acs.iecr.8b05800.

Qian F, Zhang F, Tao X, Taylor LS. ATR-FTIR spectroscopy to study amorphous dispersions: polymer interactions and physical stability. J Pharm Sci. 2011;100(7):2800-15.

Sinha P, Ubaidulla U, Nayak AK. Okra (Hibiscus esculentus) gum alginate blend mucoadhesive beads for controlled glibenclamide release. Int J Biol Macromol. 2015 Jan;72:1069-75. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014.10.002, PMID 25312603.

Singh R, Lillard JW. Nanoparticle based targeted drug delivery. Exp Mol Pathol. 2009 Jan 8;86(3):215-23. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2008.12.004, PMID 19186176.

Ortiz AC, Yanez O, Salas Huenuleo E, Morales JO. Development of a nanostructured lipid carrier (NLC) by a low energy method comparison of release kinetics and molecular dynamics simulation. Pharmaceutics. 2021 Apr 10;13(4):531. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13040531, PMID 33920242.

Arkhipov VP, Arkhipov RV, Petrova EV, Filippov A. Abnormal diffusion behavior and aggregation of oxyethylated alkylphenols in aqueous solutions near their cloud point. J Mol Liq. 2022 Apr 22;358:119203. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2022.119203.

Reis R, Sipahi H, Dinc O, Kavaz T, Charehsaz M, Dimoglo A. Toxicity mutagenicity and stability assessment of simply produced electrolyzed water as a wound healing agent in vitro. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2021;40(3):452-63. doi: 10.1177/0960327120952151, PMID 32909829.

Sun Q, Rabbani P, Takeo M, Lee SH, Lim CH, Noel ES. Dissecting Wnt signaling for melanocyte regulation during wound healing. J Invest Dermatol. 2018 Feb 8;138(7):1591-600. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2018.01.030, PMID 29428355.

Gupta R, Priya A, Chowdhary M, Batra VV, Jyotsna N, Nagarajan P. Pigmented skin exhibits accelerated wound healing compared to the nonpigmented skin in guinea pig model. iScience. 2023 Oct 7;26(11):108159. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2023.108159, PMID 37927554.

Shin J, Yang SJ, Lim Y. Gamma tocopherol supplementation ameliorated hyper-inflammatory response during the early cutaneous wound healing in alloxan-induced diabetic mice. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2017;242(5):505-15. doi: 10.1177/1535370216683836, PMID 28211759.

Dai X, Liu J, Zheng H, Wichmann J, Hopfner U, Sudhop S. Nano-formulated curcumin accelerates acute wound healing through Dkk-1-mediated fibroblast mobilization and MCP-1-mediated anti-inflammation. NPG Asia Mater. 2017;9(3):e368. doi: 10.1038/am.2017.31.