Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 5, 2025, 74-84Review Article

COMPARATIVE EVALUATION OF FUSED DEPOSITION MODELING AND STEREOLITHOGRAPHY FOR 3D PRINTING OF PERSONALIZED ORAL DRUG DELIVERY SYSTEMS

HIMANSHU THAKUR, MEENAKSHI PATEL*, BHARGAVI MISTRY

Department of Pharmaceutics, School of Pharmacy, Parul University, Post Limda, Waghodia, Vadodara, Gujarat-391760, India

*Corresponding author: Meenakshi Patel; *Email: meenakshi.patel24771@paruluniversity.ac.in

Received: 24 Mar 2025, Revised and Accepted: 24 Jun 2025

ABSTRACT

Additive manufacturing, particularly three-dimensional printing (3DP), is rapidly transforming drug formulation and production in pharmaceutical sciences. This review focuses on two prominent 3DP techniques-fused deposition modeling (FDM) and stereolithography (SLA)-for the fabrication of solid oral dosage forms with controlled drug release. FDM offers advantages such as cost-effectiveness and compatibility with pharmaceutical-grade polymers, while SLA provides superior resolution and the ability to create complex, drug-loaded matrices. Despite these promising capabilities, challenges, including material limitations, regulatory hurdles, and the need for process optimization, hinder widespread clinical adoption. Recent advancements in material science and printing technology are beginning to address these issues, paving the way for more reliable and personalized drug delivery systems. This review summarizes the fundamental principles, key advantages, limitations, and ongoing innovations in FDM and SLA for pharmaceutical applications. Future directions include overcoming regulatory barriers, expanding material options, and integrating 3DP into mainstream personalized medicine.

Keywords: 3D printing, Additive manufacturing, Fused deposition modelling, Stereolithography, Personalized medicine

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i5.54326 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Additive manufacturing (AM), commonly known as three-dimensional printing (3DP), is a transformative technology that constructs products layer by layer using computer-aided design (CAD) models [1]. In recent years, the application of 3D printing in the pharmaceutical sector has revolutionized traditional drug manufacturing by converting conventional processes into digital workflows [2, 3]. This shift has enabled the production of highly customized medical products, paving the way for personalized medicine. 3D printing is significant in pharmaceuticals because it addresses the limitations of traditional manufacturing methods, which are often complex, costly, and inflexible [4-6].

Traditional pharmaceutical manufacturing typically relies on mass production techniques that offer limited scope for customization. In contrast, 3D printing offers exceptional versatility, allowing precise control over drug dosages, release profiles, and formulation geometry tailored to individual patient needs. This is particularly critical for managing chronic conditions such as diabetes, epilepsy, and cardiovascular diseases, where patient-specific dosing and adherence to complex regimens are essential [7, 8]. For example, Spritam® (levetiracetam), the first FDA-approved 3D-printed drug, demonstrates how this technology can improve disintegration rates and patient compliance [9].

Technical considerations for developing personalized medications using 3D printing include designing 3D structures using CAD software or 3D scanning to create STL files. These files define layer-by-layer printing instructions, which are further processed through slicing software, such as Ultimaker CURA, to generate g-code instructions for the printer [10]. Pharmaceutical "inks," containing active ingredients and excipients, are then precisely deposited to form complex drug delivery systems.

Moreover, 3D printing accelerates drug development by enabling rapid prototyping and iterative optimization of formulations. This leads to shorter timeframes for drug discovery and improved safety and efficacy through continual testing. Beyond drug formulation, 3D printing also facilitates the creation of advanced drug delivery systems. For instance, multilayered oral dosage forms have been developed to release different drugs at programmed intervals, simplifying treatment regimens for patients with multiple chronic conditions [10].

Overall, the integration of 3D printing into pharmaceuticals holds great promise for enhancing patient-centric care, improving therapeutic outcomes, and reducing healthcare costs. However, the widespread adoption of this technology also demands careful attention to regulatory standards, material selection, and manufacturing reproducibility, which are discussed in subsequent sections.

Data collection

In this review, a structured literature search was performed to gather relevant studies on the application of three-dimensional printing (3DP) technologies. The databases PubMed, Science Direct, Scopus, and Google Scholar were utilized for the search. Keywords such as "3D printing in pharmaceuticals," "additive manufacturing," "fused deposition modeling," and "stereolithography" were used in various combinations with Boolean operators (AND/OR) to ensure a comprehensive retrieval of articles. Studies published between 2014 and 2024 were considered. Inclusion criteria involved peer-reviewed original research articles and systematic reviews that focused on the pharmaceutical applications of 3D printing technologies. Studies that were unrelated to pharmaceutical applications of 3D printing and non-peer-reviewed sources, such as conference abstracts and opinion articles were excluded. An initial pool of studies was identified based on title and abstract screening, followed by a full-text review to ensure relevance to the topic. Only those studies meeting the inclusion criteria were synthesized and critically analyzed for this review.

History

In the early 1990s, the pharmaceutical sector began to develop 3D printing technology at MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA). Charles Hull is considered the pioneer of 3D printing, as he created, patented, and commercialized the first apparatus for the 3D printing of items in the mid-1980s [11, 12], as well as developed the CAD software that was compatible with the STL file format. Hull's method, known as stereolithography (SL), involves a laser moving across a liquid resin surface to cure it. The stage is then submerged to allow for the curing of the layer, and this process is repeated layer by layer until the desired geometry is produced [13].

In 1998, Scott Crump, co-founder of Stratasys, Ltd., filed a patent application for fused deposition modeling (FDM). Using this method, an object can be created by melting the object and then layering the hardening material until the required shape is achieved. This method can make use of materials including molten metals, thermoplastic resins, and self-hardening waxes [13, 14].

In 2015, Aprecia Pharmaceuticals created Spritam®, the first tablet to be officially 3D printed. The FDA authorized the tablet, which contained levetiracetam, an antiepileptic medication for kids with a rare form of epilepsy. The tablet's slow and constant release of medication makes it easier for kids to take and lowers the risk of seizures [14].

Challenges in implementing 3D printing technology in clinical practice

In order to produce a sufficient quantity of printed units, the printing length is essential. This could vary from 7 sec to 15 min when taking into account oral solid dose types. The compression of a conventional industrial tablet press, which can produce millions of tablets per hour, is still far more than this [15].

Additionally, the cost of printing needs to be considered because, for example, it is difficult to lower the price of 3D-printed solid dosage forms in comparison to generic compressed tablets. The production of medications via 3D printing must ensure that the final product meets quality standards and that an effective decontamination protocol is in place to prevent cross-contamination between batches. This poses a challenge for lower-cost FDM printers, which are priced around EUR 100 to 200, as they often lack the necessary features for stringent contamination control. To the best of our knowledge, the M3DIMAKER, a 3D printer for medications that is now available for purchase for around EUR~80,000, is the only one that follows good manufacturing practices (GMP). To address the problem of cross-contamination, FabRx has introduced printing in blister packaging [16].

Comparison between conventional drug manufacturing and 3D printing

The three main processes used in the pharmaceutical business to create traditional drugs are direct compression, wet granulation, and dry granulation. Solid dosage forms, like tablets, can be difficult to manufacture and require a number of sequential steps. The most common method is direct compression, which involves just mixing the API and the excipient before transferring the mixture to the tablet press machine. After compression, the solid pharmaceutical form might need to be coated. The weak compression qualities of the powdered material, however, make direct compression impractical in some situations, requiring a granulation step first.

Through the granulation process, we can bind the medicine with additional excipients to create granules with much-improved compaction and flow characteristics. The binder can be introduced when ethanol or water is present to cause granulation. This is referred to as wet granulation or dry granulation with compaction rollers. Granules are combined with other excipients, like lubricants or disintegrants, after the granulation process, and then they are tableted. Another stage can be the need for a coating layer. But with 3D printing, once the "pharmaceutical ink" is ready, just one step is needed [17, 18]. Selecting the right 3D printing technique depends on the kind of medication we wish to produce. The primary benefits and drawbacks of each method are discussed in order to determine which one best suit the needs of the particular API type.

Types of 3d printing technologies

The major types of 3D printing technologies used in pharmaceuticals include Fused Deposition Modelling (FDM), Stereolithography (SLA), Selective Laser Sintering (SLS), and Inkjet 3D Printing.

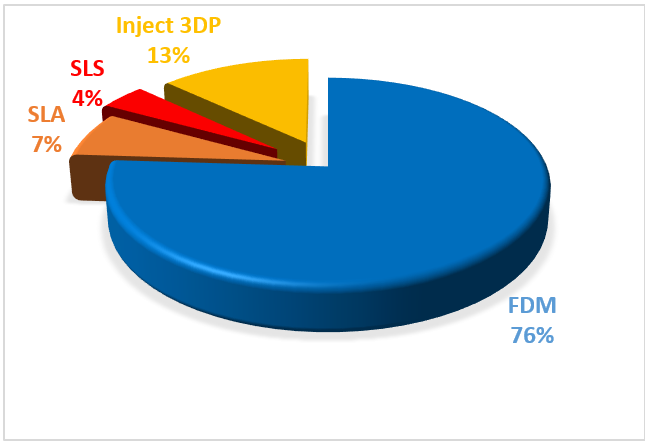

Fig. 1: Different 3DP techniques used for pharmaceutical applications [94]

Among the various techniques, this review highlights the FDM and SLA 3D printing techniques. Fig. 1 shows various technique uses for 3D printing.

Fused deposition modelling

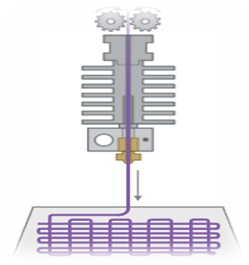

The most popular 3D printing method for creating solid oral dosage forms right now is fused deposition modeling (FDM); this trend has been brought about due to the accessibility of low-cost equipment that can even be connected to traditional pharmaceutical procedures like hot melt extrusion (HME) and film coating [19]. Introduced in 1988, the RepRap (replicating rapid prototype) project made FDM 3D printing accessible to the general public in 2005 [20]. Thermoplastic filament is used as the feedstock material in FDM 3D printers. The product is solidified and given the necessary geometry by melting it and then extruding it through a heated nozzle (fig. 2).

Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) filaments loaded with model drugs by passive diffusion were reported in early attempts to use FDM 3D printing to manufacture solid oral dosage forms [21-23]. PVA is a water-soluble polymer that has the advantage of being classified among Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) excipients [24] and a commercially available material for FDM 3D printing [25]. Additionally, a novel PVA specifically designed for HME, known as Parteck® MXP, is available [26]. However, PVA filament has a low drug loading capacity by passive diffusion, which limits its use to low active ingredient dosages [23, 27].

The FDM technique uses thermoplastic polymers like polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), polylactic acid (PLA), and acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS). Some commonly used polymers can be easily fed into FDM by being coiled and sold commercially as pre-processed filaments. Fused filament modeling (FFM) is another name for this procedure. To enable extrusion via the nozzle tip, the filament is heated by heating elements or a liquefier into a molten state as the rollers feed it. The substance cools or is chilled and solidifies during deposition [28].

A hot melt extruder (HME) can be added upstream from the printer nozzle for greater flexibility [29, 30]. This setup makes it possible to create unique formulations for use as printing material, such as amorphous solid dispersions. Instead of using prefabricated filaments like PVA filament, typical FDM equipment, precision extrusion deposition (PED), allows for powder or granule feed by incorporating a small extruder directly before the nozzle [31, 32]. Although PED has been used to create tissue scaffolds, there is currently no literature describing its application in the creation of medicinal dosage forms. FDM has recently been used to refer to the deposition of any material that may pass through a syringe or nozzle and solidify or be solidified to create a finished product [33, 34].

Fig. 2: Fused deposition modeling (FDM) 3D printer [19]

SLA (Stereolithography 3D printing)

SLA is the first and oldest of all possible 3D printing methods. Still, because of its high printing resolution and widespread use, it can print complicated geometries and components with smooth surfaces. The words stereo (solid) and "photolithography" suggest "writing with light"[35]. The materials used in SLA are photopolymerizable; they solidify when exposed to light, especially ultraviolet light. The object's size and shape are managed by employing a spatially controlled laser to reveal the light selectively [36]. The comparison between SLA and FDM is given in table 1.

SLA 3D printing uses a laser to create photopolymerization, which solidifies a liquid resin. The area to be densified is the focus of the laser. The desired free form is created by repeating the solidification layer by layer (Fig. 3).

Stereolithography (SLA) is another 3DP technique that is commonly used in tissue engineering [37, 38]. Here, the final product is created using photopolymerization, which solidifies a liquid resin. A laser pointed at a specific depth in a resin vat causes localized polymerization, which leads to solidification.

A solid, three-dimensional object is created by repeating the solidification process layer by layer [39]. The laser's energy imparted in SLA printing is crucial and depends on the light source's strength, scanning speed, exposure duration, and polymer and photoinitiator concentration [40]. The primary advantage of SLA printing is its versatility; drugs can be mixed with the photopolymer prior to printing and become trapped in the hardened matrices. Additionally, SLA has a higher resolution (20 µm compared to 50-200 µm for other manufacturing technologies) than other 3DP techniques, which are only constrained by the concentrated laser's width [39]. Another benefit is that less localized heating takes place during printing, which would make the technique more suitable for producing dosage forms containing thermolabile medications.

The primary issue with this technique is that SLA technology is limited by a small number of photocrosslinkable polymers that are not on the Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) list. Many photocrosslinkable polymers have been created in recent years, including poly(ethylene glycol) dimethacrylate (PEGDMA) [40, 41] andpoly(propylene fumarate)/diethyl fumarate (PPF/DEF) [42].

To the best of our knowledge, not much effort has been made to explore the possibility of using SLA printing to fabricate oral modified-release, unit-dose dosage forms. Thus, the specific objective of this study was to evaluate the viability of producing drug-loaded tablets by SLA printing. 4-ASA and paracetamol were chosen as model pharmaceuticals because of their considerable deterioration and thermal instability when printed using FDM technology [21], whereas the other medication was chosen because of its thermal stability and previous experience with FDM printing [43]. Furthermore, the effect of polymer composition on drug release kinetics was investigated.

There are two ways to use stereolithography for 3D printing: top-down and bottom-up. When the solid layers are formed and the printing is completed, the platform inside the resin tank will move downward from top to bottom since the UV light beam is above the tank [16]. To construct the initial layer of solid, immerse the platform in the surface at a distance equal to the desired thickness. UV light can now reach the surface as a result. Only when the substance is exposed to UV light does resin solidify. Because the UV laser beam is so tiny, this technique can yield high resolution. After the first layer has been printed, the platform covers the solid layer made with additional liquid resin, which will be the subsequent layer to be polymerized. As a result, the platform is lowered by an extra distance equal to the thickness required by the next layer. Using the alternate bottom-up printing technique, the UV light beam would be placed underneath the resin tank, which would have a clear window that would allow light to enter. In this case, the platform rises progressively as the layers are generated, according to the dimensions of each layer that must be printed [44–46].

In order to solidify the structure and conclude the polymerization process, the SLA printing technology necessitates a post-printing step that involves cleaning the final result with isopropyl alcohol to remove excess resin and curing it with UV radiation. This stage is crucial because the polymer that is created no longer contains free radicals, which are present in excess liquid resin and have been found to be genotoxic [47-49].

Fig. 3: Stereolithography (SLA) 3D printer [36]

Table 1: Comparison between FDM and SLA

| Parameter | FDM (Fused deposition Modeling) | SLA (Stereolithography) | Reference |

| Printing mechanism | Extrudes heated thermoplastic filaments layer by layer | Uses UV laser to cure liquid photopolymer resin layer by layer | [60-61] |

| Material compatibility | Limited to thermoplastics; challenges with heat-sensitive drugs due to high processing temperatures | Suitable for heat-sensitive drugs; limited availability of biocompatible, photo-curable resins | |

| Resolution and surface finish | Lower resolution (~100–300 µm); visible layer lines | High resolution (~25–50 µm); smooth surface finish | |

| Drug loading and release profiles | Lower drug loading capacity; potential for incomplete drug release | Higher precision in drug placement; potential for controlled and sustained release | |

| Post-processing requirements | Minimal; may require support removal | Requires washing and additional UV curing; handling of uncured resin necessary | |

| Cost and throughput | Lower cost; faster production times | Higher cost; longer production times due to post-processing | |

| Environmental and safety considerations | Uses biodegradable or recyclable materials like PLA; simpler waste management | Resins can be hazardous; requires careful handling and disposal |

Materials used for FDM and SLA

Among all the materials utilized in these 3DP technologies, polymers are the most preferred since they are thermoplastic matrices that mix well with other chemical ingredients. These materials' low melting points improve their manufacturing feasibility, and flexible materials are needed for various applications [50–52].

Polymers are used as building blocks for the development of tailored dosage forms because they can be chosen to change the drug's rate of release into the medium and provide the medication with physical stability. Additionally, enhancing pharmacokinetics, decreasing adverse interactions with the host tissue, and dissolving the device after its operation all depend on the polymer's biocompatibility [53]. Because it doesn't trigger inflammatory responses in individual tissues or generate harmful by products during breakdown, a biopolymer is preferred for biocompatibility and biodegradability [54].

DDS 3D printing allows for the utilization of a variety of natural and chemically engineered polymers. Due to their superior physicochemical properties, cost-benefit analysis, and established interactions with drug molecules, synthetic polymers like polylactic acid (PLA), polyvinyl pyrrolidone (PVP), polyethylene glycol (PEG), polyurethane (PU), and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) have recently attracted interest in this field [55]. Furthermore, utilizing 3DP techniques, natural polymers like collagen, gelatin, alginate, and chitosan are also used to create novel DDSs [56].

Polymers used for FDM 3D printing

Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)

In 1927, Hermann Staudinger became the first researcher to synthesize polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) [57]. With a focus on the manufacturing of food, industrial components, and medicinal disposables, this polymer has since been used in a wide range of applications [58]. PVA is a polymer that dissolves in water, but it does not dissolve in ethanol or other organic solvents [59]. It is also a synthetic polymer with low reactivity, high-temperature stability, thermoplastic qualities, and a semi-crystalline molecular structure. When it comes to biocompatibility, PVA degrades biologically. It is also a synthetic polymer with low reactivity, high-temperature stability, thermoplastic qualities, and a semi-crystalline molecular structure. PVA has very low toxicity and has a strong biological degradation potential in terms of biocompatibility [60, 61].

This polymer's mechanical characteristics include poor mechanical strength and considerable malleability and adhesion. However, these properties can be changed by mixing PVA with different polymers or additives [62]. Because PVA is an appropriate commercial polymer for FDM 3D printing, the FDA has classed this material as a generally recognized safe (GRAS) substance [24]. This polymer's high-water solubility is crucial for its application because it makes cleaning simple. Furthermore, the temperature degradation occurs between 350 and 450 degrees Celsius, whereas the PVA glass transition temperature (Tg) is 85 degrees [63]. These features make it possible to use PVA 3D-printed filaments for medication administration [64]. Hot-melt extrusion is the most effective technique for creating PVA drug-delivery filaments and the most effective way to create drug-delivery filaments using 3D printing. Krause et al. claim that PVA wires can be used to transport medications; however, further investigation is needed to ascertain the impact of PVA on the performance of FDM 3D-printed medication delivery systems. This study discovered different release characteristics on PVA drug delivery devices, which could be related to the PVA's quality. Different manufacturers' synthesis and quality control procedures may have an impact on this release profile [65].

Poly(vinylpyrrolidone) (PVP)

PVP has a melting point of 150 °C. PVP dissolves in water and a variety of organic solvents. PVP is also chemically stable, biocompatible, and nontoxic. The proper usage of PVP for the manufacturing of drug-loaded disposables is greatly aided by these chemical and physical properties [55]. It has several applications in the creation of nanoparticle devices. This is because PVP's non-ionic nature and significant hydrophilicity and hydrophobicity improve its ability to associate with a wide range of substances.

According to recent studies, PVP can be used for developing oral drug carrier systems with fast release (about 30 min to release 85% of the medication loaded). This polymer is completely eliminated by the kidneys. This led the FDA to classify PVP as a safe chemical. Furthermore, prior studies have demonstrated that PVP's physical and chemical properties make it appropriate for 3D printing using FDM, the most widely used method for creating oral drug delivery devices [66]. In order to describe different drug release profiles with the same volume-to-surface area ratio, Windolf et al. created a geometric model of oral tablets [67]. The models were made using FDM 3D printing with a combination of PVA, pramipexole (therapeutic agent, 5 %), mannitol (plasticizing agent), and fumed silica (as a glidant). PVA and praziquantel (the active medicinal ingredient, 5 weight percent) were combined to create a secondary formulation. The results show that different dosages of a single standard filament can customize the therapeutic response to the patient's therapy requirements. Even when many medications were taken together, the medical treatment had no effect on the blood plasma profile following oral ingestion of the printed tablets [56].

Polyethylene glycol

Polyethylene glycol (PEG) has been used extensively in numerous industrial processes since the 1950s, such as an additive to lower the temperature at which liquids solidify. As an ingredient for processed foods, PEG is used in the pharmaceutical sector to produce oral tablets, capsules, and pills, as well as solutions and suppositories for intradermal or transdermal use [68]. In addition, PEG is hydrophilic, lipophilic, and flexible and has a significant water absorption capacity. Numerous chemical and inorganic solvents can dissolve PEG. As the polarity of this polymer increases, its hydrophilicity also increases, making it more soluble in water. In order to increase the process ability of various polymers, including PCL, PLA, PLGA, PU, and PVA, PEG is commonly utilized as an addition (plasticizer) [56, 69].

Poly(lacticacid) (PLA)

This has been used in medical treatment to manufacture biomedical equipment and biodegradable drug delivery systems. For those goals, this usability is linked to advantageous properties like biocompatibility and bioabsorbability [70]. Fused deposition modeling (FDM) and stereolithography (SLA) are the most suitable techniques for the 3D printing of PLA for drug delivery. PLA is semicrystalline, hydrophobic, and shows a glass transition temperature and mechanical strength that are comparable to those of other biocompatible polymers.

Poly(lactide-co-glycolide)

Polyglycolic acid (PGA) and polylactic acid (PLA) copolymerize to form polylactide-co-glycolic acid (PLGA). Glycolide (GA) and lactide (LA) ring-opening polymerization was the initial synthesis of this polymer in the 1970s [71]. PLGA is a biomaterial that is very feasible and biocompatible for use in the production of disposable medication delivery devices. This polymer is safe for use in human bodies and has been classified by the FDA and the European Medicines Agency (EMA). The remarkable repeatability of PLGA is in contrast to the majority of natural polymers. This polymer has superior reproductivity and purity because it is a synthetic substance and is not dependent on environmental variables. A sustained drug release that can last months is ensured by PLGA's higher stability compared to PGA and PLA [72].

Polycaprolactone

A commercial polymer with remarkable biodegradability, biocompatibility, and process ability is PCL. Because ester linkage hydrolysis causes the toxic chemicals carbon dioxide and water to degrade, PCL breakdown in human beings is slow. These features support the use of PCL in 3D printing DDSs, which need a polymeric matrix to release the integrated material over an extended period of time [53]. Additionally, the FDA cleared PCL for safe human usage [55]. When a lengthy duration of degradation is required, PCL is a practical polymer. PCL takes between two and five years to completely degrade as compared to other polymers, particularly PLA. A key element in PCL's chemical properties is its partial crystallinity in the atomic microstructure and strong hydrophobicity [55]. Additionally, PCL has a glass transition temperature of-60 °C and a melting temperature of 59 °C to 64 °C [73]. PCL is a viable option for 3D printing because the polymer melts with less energy at these temperatures. Additionally, PCL exhibits strong mechanical strength and flexibility, both of which are important characteristics for its application in hot-melt filament extrusion [55].

Polymers used for SLA 3D Printing

Poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) (pHEMA)

PHEMA, also referred to as hydrogel material, is a biocompatible polymer. A polymer made of three-dimensional cross-linked polymeric networks based on HEMA that can hold onto water content inside its structure is known as PHEMA hydrogel [74]. PHEMA is regarded as a thermoplastic substance. In addition to their low cost, PHEMA hydrogels are non-biodegradable, have high water content, low thrombogenicity, cytocompatibility, plenty of copolymer options, soft materials with excellent temperature stability, resistance to acid and alkaline hydrolysis, adjustable mechanical properties, and an optically transparent hydrophilic polymer that is desirable for a variety of biomedical applications [75-77]. In dry conditions, PHEMA is a hard and brittle substance. When wetted with water, it becomes pliable and soft, making it easily cuttable. The density and glass transmission (Tg) of PHEMA are 1.15–1.34 g/ml and 358–393 K, respectively. The polymer becomes insoluble in water due to HEMA. Great transparency, transmission, and refraction index make PHEMA hydrogels a great choice for ophthalmologic applications in terms of optical qualities. The water content of PHEMA ranges from 20% to 80% in volume, making it appropriate for use in contact lenses. Oxygen can pass through the cornea because of the material's high oxygen permeability, softness, and flexibility. Hydrogel soft contact lenses are thin, improve comfort while wearing, and avoid corneal physiological changes while maintaining acceptable optical transparency for retinal imaging [78]. Other biomedical uses for PHEMA include wound healing, bone tissue regeneration, cancer treatment, drug delivery systems, breast augmentation, kidneys, endodontic fillings in dentistry, intrauterine inserts, prosthetics, implants, and replacement of damaged articularcartilage [79, 80].

Poly(ethylene-glycol)-Dimethacrylate (PEGDMA)

Acrylate terminals are found in PEGDA, whereas methacrylate terminals are found in PEGDMA. Acrylate monomers have been found to be more hazardous than methacrylate monomers [81], while PEGDMA is less reactive than PEGDA due to the inclusion of a methyl group. PEGDMA is non-cytotoxic and allows for cellular adhesion without peptide alterations, according to earlier studies [82, 83]. Because of these qualities, PEGDMA is a viable option for a synthetic polymer in a bioink for SLA bioprinting [82].

PEGDMA's well-characterized material characteristics, lack of immunogenicity, established cytocompatibility, and ease of manufacturing have led to its widespread use in a variety of tissue engineering applications [85, 86]. Additionally, the PEGDMA material qualities can be easily altered by varying the chain length, the hydrogel's weight percentage of the macromer, and the addition of additional materials to form a hydrogel composite. Despite the fact that PEGDMA and related hydrogels have many benefits and have generated a lot of interest thus far, their application as a foundation for 3D printing While the impact of SLA on the material characteristics of PEGDMAs has not yet been thoroughly investigated, SLA has been primarily focused on the feasibility of the 3Dprinting technology [87].

Poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate PEGDA

(Polyethylene glycol diacrylate (PEGDA), a synthetic polymer with strong water solubility and biocompatibility, has been certified by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in medical device manufacturing. PEGDA is chemically adaptable and offers considerable processing capabilities. When exposed to a certain wavelength of light, it undergoes a cross-linking reaction that turns it from a tiny, low-viscosity monomer (liquid) into a stable polymer (solid), creating specimens with high precision. Ester bond hydrolysis is one way that PEGDA can break down while being used in vivo. PEGDA is therefore crucial for biomedical applications, including medication delivery and wound healing.

Pure PEGDA, on the other hand, readily loses water when used as a hydrogel. Additionally, proteins are not effectively adsorbable by the flat surface of cured PEGDA, which leads to poor cell adsorption and cell growth. According to some research, PEGDA is a photosensitive resin pre-polymer that is utilized to create bio-ceramics through UV curing. Its pyrolysis during later degreasing, however, has prevented PEGDA's biological activity from being effectively used [88].

Analytical characterisation for 3D printed formulation

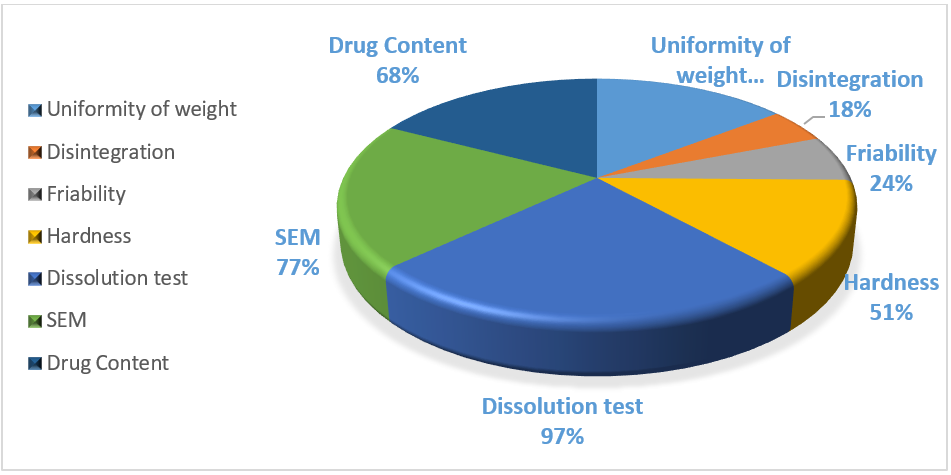

A range of characterization tests were used to evaluate the FDM 3DP compositions' physical-mechanical properties (fig. 4). Furthermore, every test was conducted to investigate particular elements and characteristics, including the drug release profile, the disintegration time, the tablet breaking force, the 3D structure, the porosity, and whether or not the medication(s) degraded during 3D printing.

The drug content test, which was conducted in 68% (n = 69) of the publications that were included in the systematic review, showed that there was no drug degradation during the FDM process. In the majority of these, the drug content value was near the theoretical one. For example, in the study by Genina et al., the drug's actual content was 62.2±1.4%, whereas the theoretical content was 70% w/w. The authors proposed that this little discrepancy was caused by the drug's stickiness during the manufacturing process when it was in powder form [89]. On the other hand, Goyanes et al. found that the heated extruder's temperature of 210 °C caused half of the medication (4-ASA) to deteriorate. The drug's initial weight percentage of 0.24% rose to 0.12% after extrusion. 4-ASA melted and broke down at 130 and 145 °C. This implied that choosing the right medication based on its physical characteristics was important [22]. As shown in fig. 4, 77% (n = 79) of the included publications underwent SEM analysis, with varying outcomes. For example, Skowyra et al. observed that at the conclusion of the extrusion process, irregular pores and spaces between layers appeared on the surface of the extruded filaments due to the evaporation of the water content and evaporable additives. Additionally, the surface appeared rough and uneven due to the partially connected filaments [23]. Additionally, a second study by Goyanes et al. found that the internal patterns were influenced by the infilling percentage. The tablets seemed denser when the infilling percentage was increased [45]. The dissolution test (fig. 4), which was used in 97% of the articles (n = 99) to determine how long it took for a drug to dissolve in the dissolution media and whether the drug release profile was instantaneous or sustained, was the most common characterization test among the FDM articles that were part of the systematic review (fig. 5).

Fig. 4: Various numbers of characterization tests were conducted in accordance with the British pharmacopeia for FDM items

Fig. 5: Illustration of two distinct drug release profiles achieved through FDM 3D printing technology in various articles

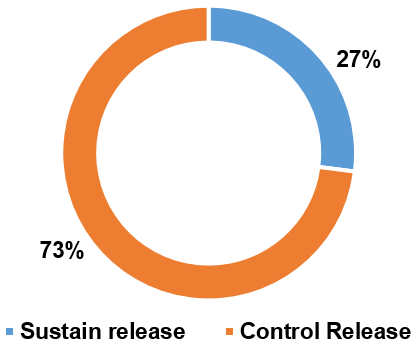

Many researchers claim that a number of factors can affect the drug dissolving profile and that most 3DP formulations (73%, n = 70) had a sustained drug release profile. For instance, Shin et al. discovered that the size and shape of the 3DP formulations had an impact. Moreover, smaller tablets had a quicker drug release due to a larger surface area/mass ratio, whereas larger tablets, defined also as printlets, presented a slower drug release because the SA/V ratio was smaller [90].

Skowrya et al., for instance, found that after 12 and 18 h, the majority of the drug (>80%) was released at dosages of 4, 5, 7.5, and 10 mg. Furthermore, because of a lower SA/V ratio, the full drug release was accomplished in 16 h for smaller tablets and in 20–24 h for larger ones [23]. The only formulations that met the BP acceptable level had an immediate drug release profile.

Another essential British Pharmacopeia requirement was the hardness test, which was carried out in half of the studied trials (51%, n = 52). Furthermore, as it is one of the requirements set forth by BP, this diminished assessment may be a drawback. In certain instances, as in the studies of Goyanes et al. and Chen et al., this parameter was not assessed because the tablets' hardness strength exceeded the highest values that the hardness tester could measure (800 N) [45, 87]. On the one hand, the hardness values of the 3DP FDM formulations were lower. For example, in the study by Khaled et al., the mesh tablets had 224.67 N and the ring tablets had 24.72 N. In both cases, the hardness values were too small [91, 92].

A third BP requirement was represented by the friability test, which was carried out only in 24% of the FDM-included articles, possibly due to the reduction of the hardness values of the formulations. Moreover, considering the publications where this analysis was performed, all of them met the BP requirements, having a friability parameter minor or equal to one. In some cases, the friability was 0%, such as in the works conducted by Okwuosa et al. and Goyanes et al. [45, 93].

Considering fig. 4, only 18% (n = 18) of the articles tested the fourth BP criteria, the disintegration time. As said regarding the friability, this could be a limitation and a factor that requires more investigation in later research. Only a small number of formulations, such as those in the studies by Jeong et al. and Khaled et al. [94], could be classified as an ODT (complete disintegration underwent in less than 3 min (European Pharmacopeia) or if less than 30 s by the FDA), when taking into consideration the articles where the disintegration time was evaluated. Each of these articles met the BP criteria, and the total disintegration time ranged from 5 to 15 min in the other examples. Furthermore, Palekar et al. [95] found a direct correlation between the infill percentage and the disintegration time. In actuality, a larger infill percentage resulted in a faster disintegration period and less water penetration in the formulation.

Furthermore, BP had to consider weight homogeneity, whose acceptable range was determined by average mass. For example, the maximum deviation percentage was 10% if the average weight was 84 mg or less, 7.5 if the weight was between 84 and 250 mg, and 5% if the average weight was greater than 250 mg.

As shown in fig. 7 above, this test was conducted in 57% (n = 58) of the available papers, and only a small portion of them met the BP limits. If, for example, three different tablets with three different infilling percentages (30%, 50%, and 70%) were manufactured in the work by Li et al. and the average weight was greater than 250 mg and the deviation percentage was 2% in each of the three cases, it was possible to determine that all of the formulations met the specification [96].

Different drug formulated by 3D printing technology

Drugs classification

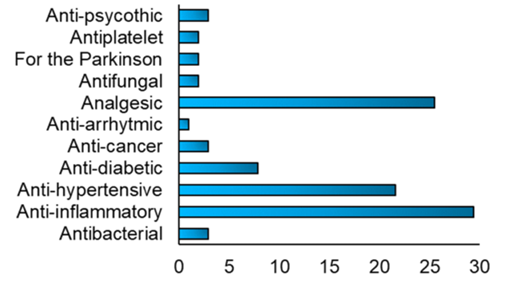

According to reports, the FDM 3DP formulations contained a variety of drugs (fig. 6), and the administration of each medication differed depending on the condition that required treatment. In the FDM 3DP formulations, the most commonly employed drug types were anti-inflammatory medications like acyclovir and prednisolone, analgesics like paracetamol and aspirin, and antihypertensive medications like nifedipine and carvedilol [86].

Fig. 6: Fig. depicting various types of drugs incorporated into FDM 3D printed formulations [94]

Test for SLA (Stereolithography) 3D printing technique

The drug dissolution test was another crucial test used to assess the efficacy of the SLA approach, and it was carried out in 100% (n=8) of the publications. In particular, the researchers evaluated the correlation between a number of variables, such as the proportion of cross-linkable polymers in the tablets, the shape and structure of the tablets, and the effect of excipient addition on the rate of drug release. The scientists concluded that the dissolving profile can be influenced by the geometry of the tablets as well as the addition of excipients and that it was important to choose an appropriate quantity of photocrosslinkable polymer to control the drug release rate [94].

Wang et al. investigated the possible impacts of the cross-linkable polymers in the tablets' PEDGA/PEG 300 ratio on the dissolving profile. On the one hand, they discovered an indirect correlation between the amount of PEDGA and the drug release rate. For example, after 10 h, 100% of the paracetamol was released when the PEDGA content was 35%, but 84% and 76% of the paracetamol was released when the PEDGA content was 65% and 90%, respectively. However, there was a direct association between the amount of PEG 300 and the medication release rate, meaning that if the first increased, the second would also increase [97].

Furthermore, Heavy et al.'s investigation examined the connection between drug release rate and cross-linkable polymers. Furthermore, Wang et al. and these authors came to the conclusion that choosing the right photocross linkable polymer was important in order to control drug release because, on the one hand, surface cure issues could arise if the polymer concentration was too low. However, if it was very high, this concentration might decrease the amount of UV radiation that would reach the bottom layers, resulting in insufficient curing. Moreover, the formulations were characterised by a sustained drug release rate profile over the 24 h [18]. The homogeneity of weight, another characterization test mandated by the British Pharmacopeia, was assessed in 50% (n = 4) of the trials. All of the printlets in the Heavy et al. investigation had weight uniformity between 81.7 and 118%, with a 36.3% percentage deviation. Given that the average mass was 1621 mg and the British Pharmacopeia's recommended weight limit varies, these values did not adhere to the recommended limits [88].

Likewise, the weight of the tablets in the Kadry et al. research varied between 133.70 mg and 174.23 mg. With a variance of 26.2%, the weight ranged from 86.8 to 113%, with an average of 154.0 mg. In light of the British Pharmacopeia's recommended weight fluctuation restrictions, these pills did not satisfy the Pharmacopeia Specifications [98]. With a percentage of variation greater than that specified by the British Pharmacopeia, both formulations failed to satisfy Pharmacopeia requirements.

Quantifying which of the several 3DP methodologies assessed was utilized most frequently in the included papers was the main goal of the first study. The most popular 3DP technique for creating solid oral drug delivery systems was FDM, with a 76% (n = 102) value. High resolution, good mechanical strength, and the ability to create 3D formulations with a particular drug release profile while achieving different printing conditions were also the primary benefits of this technology [94]. Only the FDM approach had a little lower result than the others (68%), but the majority of the techniques examined assessed the drug content with a percentage above 90%.

Table 2: Schematic summaries of the two characterisation tests performed with the two 3DP techniques (FDM, SLA)

| Different 3DP technique | Drug content | Dissolution profile | Hardness | Friability | Disintegration | Uniformity of weight | Reference |

| FDM | 68% | 97% | 51% | 24% | 18% | 57% | [94] |

| SLA | 100% | 100% | 37.5% | 0% | 0% | 50% |

Determining whether the drug release profile was immediate or sustained, as well as the amount of drug released in a specific amount of time, were the goals of the drug dissolution test. It was performed with a percentage value of 100% for each of the four strategies assessed in practically all of the included papers. Furthermore, tablets are the recommended 3DP forms because they have superior mechanical and physical qualities, like hardness and friability, as compared to the other formulations. This test was only conducted in half of the cases (51%), taking into account the FDM 3DP process [94].

The primary factors that influenced the hardness were the number of excipients added to the formulation and the laser scanning speed [98], as indicated by the fact that Allahham et al. observed an inverse relationship between the breaking force values and the laser scanning speed [99]. Given the importance of this parameter, this test must be carried out in future studies to ascertain whether the 3DP drug delivery system meets BP requirements and is suitable for its intended purpose. A relatively small number of publications (17–24%) used the friability test in three of the four 3DP approaches, but not SLA. The reason for this might be that the 3DP formulations' limited hardness values prevented them from passing this kind of test. This lower evaluation of friability is a component that needs to be improved in subsequent studies, as it is one of the tests mandated by the British Pharmacopeia (BP). Additionally, according to Infanger et al., the porosity of the binder particles was the primary factor influencing the friability and was directly correlated with the friability values [100]. Likewise, all of the FDM 3DP formulations had friability values of 1%, meeting the BP requirements. The summary of the characterization test performed on FDM and SLA techniques is given in Table 2.

Nevertheless, it is not possible to determine which 3DP technique is best for printing oral solid formulations because each one has pros and cons, and the choice of printing method relies on the kind of formulation that needs to be produced as well as the physical-mechanical characteristics that must be met, like hardness, friability, or drug dissolution profile. The 3DP of medicine is a young field that is confronted with several obstacles. The appropriateness of the 3DP procedures is one barrier because several of them may hinder the stability of medications that are thermolabile. Making tablets that adhere to pharmacopeia and regulatory organizations' legal standards is also still difficult. Another problem is that there aren't many ink materials that are appropriate and compatible with making oral drugs [101].

Regulatory aspects

To regulate the use of 3D printing (additive manufacturing) in the production of medical devices, the U. S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) released a draft guidance titled “Technical Considerations for Additive Manufactured Devices” in May 2016 [102]. This document emphasizes the need for detailed documentation at every stage of the 3D printing process, including material selection, device design, printing parameters, and post-processing procedures. It also highlights the unique advantage of 3D printing in creating customized devices tailored to the individual patient's anatomy [103]. According to the guidance, manufacturers must justify the use of additive manufacturing and explain how variations in processing parameters influence the final product’s properties. Importantly, all materials used must have a traceable origin, and alternative sourcing options should be considered to ensure supply chain robustness. Material characteristics that impact interlayer bonding must be critically evaluated, as they can significantly influence device performance.

Moreover, the FDA underscores the importance of validating the software used for device design and manufacturing, given the risks associated with software-driven errors in 3D printing workflows. In recent years, the FDA has approved several 3D-printed devices for biomedical applications, including orthopedic implants and dental prostheses, with regulatory expectations for material quality and device performance becoming increasingly stringent [104].

Beyond devices, regulatory frameworks for 3D-printed pharmaceuticals are still evolving. The FDA's approval of Spritam® (levetiracetam), the first 3D-printed drug by Aprecia Pharmaceuticals in 2015, marked a significant milestone. However, regulatory authorities such as the FDA and European Medicines Agency (EMA) recognize critical challenges specific to 3D-printed drugs, particularly concerning quality control, reproducibility, and batch-to-batch consistency [105]. Unlike traditional manufacturing, where large uniform batches are produced, 3D printing often involves small-scale, patient-specific production, making conventional quality assurance models less applicable.

Ensuring consistent drug content, dissolution profiles, mechanical strength, and sterility across individualized units is complex and demands the development of novel in-process monitoring and validation strategies [106]. Moreover, patient-specific risks - such as dosing errors, altered pharmacokinetics due to customized dosage forms, and individual biocompatibility responses - require thorough safety assessments during both preclinical and clinical evaluation phases. Regulatory agencies are thus encouraging the use of risk-based approaches, design controls, and robust validation protocols to safeguard patient health while supporting innovation.

In conclusion, while 3D printing offers unprecedented opportunities for personalized medicine, its regulatory landscape must continue to adapt to address unique challenges in quality assurance, reproducibility, patient safety, and software validation to ensure consistent and safe therapeutic outcomes.

CONCLUSION

3D printing (3DP) has emerged as a transformative technology in the pharmaceutical sector, offering a novel approach to personalized medicine. However, selecting the optimal 3DP technique for manufacturing oral solid dosage forms remains a complex task, as each method possesses distinct advantages and limitations. Despite its promising potential, 3DP faces several significant challenges in pharmaceutical manufacturing. The key challenges include maintaining thermolabile drug stability, limited pharmaceutical-grade printable materials, and evolving regulatory requirements. The FDA has introduced guidelines focusing on quality control and traceability to support 3DP integration. Future studies should prioritize the development of thermally stable drug formulations, the synthesis of novel biocompatible and regulatory-compliant printing materials, and the refinement of low-temperature printing techniques. A collaborative approach, involving academia, industry stakeholders, and regulatory agencies, will be pivotal in advancing material sciences, optimizing printing methodologies, and strengthening the regulatory framework. With sustained innovation and cross-sector partnerships, 3DP holds the potential to revolutionize drug delivery systems and realize the vision of truly personalized, on-demand therapeutics.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Himanshu Thakur prepared the initial draft of the manuscript. Meenakshi Patel guided the overall development of the review article by outlining its structure and providing critical insights throughout the process. Bhargavi Mistry verified the content and made necessary corrections to refine the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Hsiao WK, Lorber B, Reitsamer H, Khinast J. 3D printing of oral drugs: a new reality or hype? Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2018 Jan;15(1):1-4. doi: 10.1080/17425247.2017.1371698, PMID 28836459.

Scoutaris N, Ross S, Douroumis D. Current trends on medical and pharmaceutical applications of inkjet printing technology. Pharm Res. 2016 Aug;33(8):1799-816. doi: 10.1007/s11095-016-1931-3, PMID 27174300.

Zhang J, VO AQ, Feng X, Bandari S, Repka MA. Pharmaceutical additive manufacturing: a novel tool for complex and personalized drug delivery systems. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2018 Nov;19(8):3388-402. doi: 10.1208/s12249-018-1097-x, PMID 29943281, PMCID PMC6283689.

Wang S, Chen X, Han X, Hong X, Li X, Zhang H. A review of 3D printing technology in pharmaceutics: technology and applications now and future. Pharmaceutics. 2023 Jan 26;15(2):36839738. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics15020416.

Abbasi M, Vaz P, Silva J, Martins P. Head to head evaluation of FDM and SLA in additive manufacturing: performance cost and environmental perspectives. Appl Sci. 2025 Feb 19;15(4):2245. doi: 10.3390/app15042245.

Deshmane S, Kendre P, Mahajan H, Jain S. Stereolithography 3D printing technology in pharmaceuticals: a review. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2021 Sep;47(9):1362-72. doi: 10.1080/03639045.2021.1994990, PMID 34663145.

Lambert KF, Whitehead M, Betz M, Nutt J, Dubose C. An overview of 3-D printing for medical applications. Radiol Technol. 2022 Mar;93(4):356-67. PMID 35260484.

Andreadis II, Gioumouxouzis CI, Eleftheriadis GK, Fatouros DG. Correction: andreadis. The advent of a new era in digital healthcare: a role for 3d printing technologies in drug manufacturing? Pharmaceutics. 2022;14(12):2782. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14122782, PMID 36559340.

Reddy CV, VB, Venkatesh MP, Pramod Kumar TM. First FDA approved 3D printed drug paved new path for increased precision in patient care. ACCTRA. 2020;7(2):93-103. doi: 10.2174/2213476X07666191226145027.

Serrano DR, Kara A, Yuste I, Luciano FC, Ongoren B, Anaya BJ. 3D printing technologies in personalized medicine nanomedicines and biopharmaceuticals. Pharmaceutics. 2023 Jan 17;15(2):313. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics15020313, PMID 36839636, PMCID PMC9967161.

PubChem. Bethesda (MD): national library of medicine (US) national center for biotechnology information. Pubchem patent summary for us-6027324-a apparatus for production of three dimensional objects by stereolithography; 2004. Available from: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/patent/US-6027324-A. [Last accessed on 30 Apr 2025].

Husna A, Ashrafi S, Tomal AA, Tuli NT, Bin Rashid AB. Recent advancements in stereolithography (SLA) and their optimization of process parameters for sustainable manufacturing. Hybrid Adv. 2024 Oct 11;7:100307. doi: 10.1016/j.hybadv.2024.100307.

Hull CW, Spence ST, Albert DJ. Method and apparatus for production of high resolution three dimensional objects by stereolithography; 1993.

Prasad LK, Smyth H. 3D Printing technologies for drug delivery: a review. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2016;42(7):1019-31. doi: 10.3109/03639045.2015.1120743, PMID 26625986.

Tan YJ, Yong WP, Kochhar JS, Khanolkar J, Yao X, Sun Y. On demand fully customizable drug tablets via 3D printing technology for personalized medicine. J Control Release. 2020 Jun 10;322:42-52. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.02.046, PMID 32145267.

Lanno V, Vurpillot S, Prillieux S, Espeau P. Pediatric formulations developed by extrusion-based 3D printing: from past discoveries to future prospects. Pharmaceutics. 2024 Mar 22;16(4):441. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics16040441. PMID: 38675103.

Nashed N, Lam M, Ghafourian T, Pausas L, Jiri M, Majumder M. An insight into the impact of thermal process on dissolution profile and physical characteristics of theophylline tablets made through 3D printing compared to conventional methods. Biomedicines. 2022 Jun 6;10(6):1335. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10061335, PMID 35740357, PMCID PMC9219830.

Khosravani MR, Reinicke T. On the environmental impacts of 3D printing technology. Appl Mater Today. 2020 May 17;20:100689. doi: 10.1016/j.apmt.2020.100689.

Dumpa N, Butreddy A, Wang H, Komanduri N, Bandari S, Repka MA. 3D printing in personalized drug delivery: an overview of hot melt extrusion based fused deposition modeling. Int J Pharm. 2021 May 1;600:120501. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.120501, PMID 33746011, PMCID PMC8089048.

Skowyra J, Pietrzak K, Alhnan MA. Fabrication of extended-release patient-tailored prednisolone tablets via fused deposition modelling (FDM) 3D printing. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2015 Feb 20;68:11-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejps.2014.11.009. PMID: 25460545

Basa B, Jakab G, Kallai Szabo N, Borbas B, Fulop V, Balogh E. Evaluation of biodegradable PVA-based 3D printed carriers during dissolution. Materials (Basel). 2021 Mar 11;14(6):1350. doi: 10.3390/ma14061350, PMID 33799585, PMCID PMC7998734.

Sun X, Zhou J, Wang Q, Shi J, Wang H. PVA fibre reinforced high strength cementitious composite for 3D printing: mechanical properties and durability. Addit Manuf. 2022 Jan;49:102500. doi: 10.1016/j.addma.2021.102500.

Skowyra J, Pietrzak K, Alhnan MA. Fabrication of extended-release patient-tailored prednisolone tablets via fused deposition modelling (FDM) 3D printing. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2015 Feb 20;68:11-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejps.2014.11.009. PMID: 25460545.

Paccione N, Guarnizo Herrero V, Ramalingam M, Larrarte E, Pedraz JL. Application of 3D printing on the design and development of pharmaceutical oral dosage forms. J Control Release. 2024 Sep;373:463-80. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2024.07.035, PMID 39029877.

Gultekin HE, Tort S, Acarturk F. Fabrication of three dimensional printed tablets in flexible doses: a comprehensive study from design to evaluation. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2022 Jun 21;74:103538. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2022.103538.

Merck, 2023. Candurin Gold Sheen Specification. Available: https://surface-portal.merckgroup.com/BR/en/product/PM/120608

Zhou LY, Fu J, He Y. A review of 3D printing technologies for soft polymer materials. Adv Funct Materials. 2020 Apr 29;30(28). doi: 10.1002/adfm.202000187.

Nukala PK, Palekar S, Solanki N, Fu Y, Patki M, Shohatee AA. Investigating the application of FDM 3D printing pattern in preparation of patient tailored dosage forms. J 3D Print Med. 2019;3(1):23-37. doi: 10.2217/3dp-2018-0028.

Curti C, Kirby DJ, Russell CA. Current formulation approaches in design and development of solid oral dosage forms through three dimensional printing. Prog Addit Manuf. 2020 Mar 21;5(2):111-23. doi: 10.1007/s40964-020-00127-5.

Wang J, Zhang Y, Aghda NH, Pillai AR, Thakkar R, Nokhodchi A. Emerging 3D printing technologies for drug delivery devices: current status and future perspective. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2021 Jul;174:294-316. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2021.04.019, PMID 33895212.

Patel A, Taufik M. Extrusion based technology in additive manufacturing: a comprehensive review. Arab J Sci Eng. 2024;49(2):1309-42. doi: 10.1007/s13369-022-07539-1.

Jin Z, He C, Fu J, Han Q, He Y. Balancing the customization and standardization: exploration and layout surrounding the regulation of the growing field of 3D-printed medical devices in China. Biodes Manuf. 2022;5(3):580-606. doi: 10.1007/s42242-022-00187-2, PMID 35194519, PMCID PMC8853031.

Li L, McGuan R, Isaac R, Kavehpour P, Candler R. Improving precision of material extrusion 3D printing by in situ monitoring & predicting 3D geometric deviation using conditional adversarial networks. Addit Manuf. 2021 Feb;38:101695. doi: 10.1016/j.addma.2020.101695.

Borandeh S, Van Bochove B, Teotia A, Seppala J. Polymeric drug delivery systems by additive manufacturing. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2021 Jun;173:349-73. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2021.03.022, PMID 33831477.

Jadhav A, Jadhav VS. A review on 3D printing: an additive manufacturing technology. Mater Today Proc. 2022 Jan 1;62:2094-9. doi: 10.1016/j.matpr.2022.02.558.

Kaul RP, Sagar S. Role of 3D Image Processing and Printing in the Diagnosis and Treatment Planning for Maxillofacial Surgery, 2025. DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.1009516.

Lakkala P, Munnangi SR, Bandari S, Repka M. Additive manufacturing technologies with emphasis on stereolithography 3D printing in pharmaceutical and medical applications: a review. Int J Pharm X. 2023 Jan 3;5:100159. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpx.2023.100159, PMID 36632068, PMCID PMC9827389.

PubChem. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US). National center for biotechnology information. PubChem patent summary for US-6027324-a apparatus for production of three dimensional objects by stereolithography; 2004. Available from: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/patent/US-6027324-A. [Last accessed on 30 Apr 2025].

Mukhtarkhanov M, Perveen A, Talamona D. Application of stereolithography based 3D printing technology in investment casting. Micromachines (Basel). 2020 Oct 19;11(10):946. doi: 10.3390/mi11100946, PMID 33086736, PMCID PMC7589843.

Quan H, Zhang T, Xu H, Luo S, Nie J, Zhu X. Photo-curing 3D printing technique and its challenges. Bioact Mater. 2020 Jan 22;5(1):110-5. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2019.12.003.

Ge Q, Li Z, Wang Z, Kowsari K, Zhang W, He X. Projection micro stereolithography based 3D printing and its applications. Int J Extreme Manuf. 2020 Apr 27;2(2):22004. doi: 10.1088/2631-7990/ab8d9a.

Ananth KP, Jayram ND. A comprehensive review of 3D printing techniques for biomaterial based scaffold fabrication in bone tissue engineering. Annals of 3D Printed Medicine. 2023 Nov 23;13:100141. doi: 10.1016/j.stlm.2023.100141.

Maines EM, Porwal MK, Ellison CJ, Reineke TM. Sustainable advances in SLA/DLP 3D printing materials and processes. Green Chem. 2021 Jan 1;23(18):6863-97. doi: 10.1039/D1GC01489G.

Zennifer A, Manivannan S, Sethuraman S, Kumbar SG, Sundaramurthi D. 3D bioprinting and photocrosslinking: emerging strategies and future perspectives. Biomater Adv. 2022 Mar;134:112576. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2021.112576, PMID 35525748, PMCID PMC10350869.

Goyanes A, Robles Martinez P, Buanz A, Basit AW, Gaisford S. Effect of geometry on drug release from 3D printed tablets. Int J Pharm. 2015 Oct 30;494(2):657-63. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2015.04.069, PMID 25934428.

Pawar R, Pawar A. 3D printing of pharmaceuticals: approach from bench scale to commercial development. Futur J Pharm Sci. 2022;8(1):48. doi: 10.1186/s43094-022-00439-z, PMID 36466365, PMCID PMC9702622.

Konta AA, Garcia Pina M, Serrano DR. Personalised 3D printed medicines: which techniques and polymers are more successful? Bioengineering (Basel). 2017 Sep 22;4(4):79. doi: 10.3390/bioengineering4040079, PMID 28952558, PMCID PMC5746746.

Arrigoni C, Gilardi M, Bersini S, Candrian C, Moretti M. Bioprinting and organ on chip applications towards personalized medicine for bone diseases. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2017 Jun;13(3):407-17. doi: 10.1007/s12015-017-9741-5, PMID 28589446.

Karakurt I, Aydogdu A, Cikrıkcı S, Orozco J, Lin L. Stereolithography (SLA) 3D printing of ascorbic acid loaded hydrogels: a controlled release study. Int J Pharm. 2020 Jun 30;584:119428. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.119428, PMID 32445906.

Wickramasinghe S, Do T, Tran P. FDM based 3D printing of polymer and associated composite: a review on mechanical properties defects and treatments. Polymers (Basel). 2020 Jul 10;12(7):1529. doi: 10.3390/polym12071529, PMID 32664374, PMCID PMC7407763.

Kafle A, Luis E, Silwal R, Pan HM, Shrestha PL, Bastola AK. 3D/4D printing of polymers: fused deposition modelling (FDM) selective laser sintering (SLS) and stereolithography (SLA). Polymers (Basel). 2021 Sep 15;13(18):3101. doi: 10.3390/polym13183101, PMID 34578002, PMCID PMC8470301.

Stansbury JW, Idacavage MJ. 3D printing with polymers: challenges among expanding options and opportunities. Dent Mater. 2016 Jan;32(1):54-64. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2015.09.018, PMID 26494268.

Ligon SC, Liska R, Stampfl J, Gurr M, Mulhaupt R. Polymers for 3D printing and customized additive manufacturing. Chem Rev. 2017 Aug 9;117(15):10212-90. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00074, PMID 28756658, PMCID PMC5553103.

Puza F, Lienkamp K. 3D printing of polymer hydrogels from basic techniques to programmable actuation. Adv Funct Materials. 2022 Jul 24;32(39). doi: 10.1002/adfm.202205345.

Bose S, Ke D, Sahasrabudhe H, Bandyopadhyay A. Additive manufacturing of biomaterials. Prog Mater Sci. 2018 Apr;93:45-111. doi: 10.1016/j.pmatsci.2017.08.003, PMID 31406390.

Prajapati SK, Jain A, Jain A, Jain S. Biodegradable polymers and constructs: a novel approach in drug delivery. Eur Polym J. 2019 Aug 16;120:109191. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2019.08.018.

Jain A, Bansal KK, Tiwari A, Rosling A, Rosenholm JM. Role of polymers in 3D printing technology for drug delivery an overview. Curr Pharm Des. 2018;24(42):4979-90. doi: 10.2174/1381612825666181226160040, PMID 30585543.

Cardoso PH, Araujo ES. An approach to 3D printing techniques polymer materials and their applications in the production of drug delivery systems. Compounds. 2024 Jan 17;4(1):71-105. doi: 10.3390/compounds4010004.

Pugliese R, Beltrami B, Regondi S, Lunetta C. Polymeric biomaterials for 3D printing in medicine: an overview. Annals of 3D Printed Medicine. 2021 Apr 9;2:100011. doi: 10.1016/j.stlm.2021.100011.

Mallakpour S, Tabesh F, Hussain CM. A new trend of using poly(vinyl alcohol) in 3D and 4D printing technologies: process and applications. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2022 Mar;301:102605. doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2022.102605, PMID 35144173.

Peng H, Han B, Tong T, Jin X, Peng Y, Guo M. 3D printing processes in precise drug delivery for personalized medicine. Biofabrication. 2024 Apr 17;16(3). doi: 10.1088/1758-5090/ad3a14, PMID 38569493, PMCID PMC11164598.

Musa BH, Hameed NJ. Study of the mechanical properties of polyvinyl alcohol/starch blends. Mater Today Proc. 2020;20:439-42. doi: 10.1016/j.matpr.2019.09.161.

Peng Z, Kong LX. A thermal degradation mechanism of polyvinyl alcohol/silica nanocomposites. Polymer Degradation and Stability. 2007 Jun 1;92(6):1061-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2007.02.012.

Crișan AG, Porfire A, Ambrus R, Katona G, Rus LM, Porav AS, Ilyés K, Tomuță I. Polyvinyl alcohol-based 3D printed tablets: novel insight into the influence of polymer particle size on filament preparation and drug release performance. Pharmaceuticals. 2021 May 1;14(5):418. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph14050418.

Krause J, Bogdahn M, Schneider F, Koziolek M, Weitschies W. Design and characterization of a novel 3D printed pressure controlled drug delivery system. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2019 Dec 1;140:105060. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2019.105060, PMID 31499171.

Bianchi M, Pegoretti A, Fredi G. An overview of poly(vinyl alcohol) and poly(vinyl pyrrolidone) in pharmaceutical additive manufacturing. J Vinyl Addit Technol. 2023 Feb 7;29(2):223-39. doi: 10.1002/vnl.21982.

Windolf H, Chamberlain R, Quodbach J. Dose independent drug release from 3D printed oral medicines for patient-specific dosing to improve therapy safety. Int J Pharm. 2022 Mar 25;616:121555. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2022.121555, PMID 35131358.

D’souza AA, Shegokar R. Polyethylene glycol (PEG): a versatile polymer for pharmaceutical applications. Expert opinion on drug delivery. 2016 Sep 1;13(9):1257-75. https://doi.org/10.1080/17425247.2016.1182485. PMID: 27116988.

Kuhn AM. Optimizing the mechanical properties of a PLA/PCL thin film through the inclusion of PEG as a plasticizing agent (Master's thesis, University of Cincinnati).

Masutani K, Kimura Y. Chapter 1: PLA synthesis. From the monomer to the Polymer. Jimenez A, Peltzer M, Ruseckaite R, editors. Poly(lactic acid) science and technology. Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry; 2014. p. 1-36. doi: 10.1039/9781782624806-00001.

Silva AT, Cardoso BC, Silva ME, Freitas RF, Sousa RG. Synthesis characterization and study of PLGA copolymer in vitro degradation. J Biomater Nanobiotechnol. 2015;6(1):8-19. doi: 10.4236/jbnb.2015.61002.

Samantaray PK, Little A, Haddleton DM, McNally T, Tan B, Sun Z, Huang W, Ji Y, Wan C. Poly (glycolic acid)(PGA): A versatile building block expanding high performance and sustainable bioplastic applications. Green Chemistry. 2020;22(13):4055-81. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0GC01394C.

Jenkins M, Stamboulis A. Durability and reliability of medical polymers. Woodhead Publishing Limited; 2012. doi: 10.1533/9780857096517.

Li G, Dobryden I, Salazar Sandoval EJ, Johansson M, Claesson PM. Load dependent surface nanomechanical properties of poly-HEMA hydrogels in aqueous medium. Soft Matter. 2019 Oct 14;15(38):7704-14. doi: 10.1039/c9sm01113g, PMID 31508653.

Zare M, Bigham A, Zare M, Luo H, Rezvani Ghomi E, Ramakrishna S. pHEMA: an overview for biomedical applications. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Jun 15;22(12):6376. doi: 10.3390/ijms22126376, PMID 34203608, PMCID PMC8232190.

De Nitto S, Serafin A, Karadimou A, Schmalenberger A, Mulvihill JJ, Collins MN. Development and characterization of 3D-printed electroconductive pHEMA-co-MAA NP-laden hydrogels for tissue engineering. Bio Des Manuf. 2024 Apr 25;7(3):262-76. doi: 10.1007/s42242-024-00272-8.

Hong KH, Jeon YS, Kim JH. Preparation and properties of modified PHEMA hydrogels containing thermo responsive pluronic component. Macromol Res. 2009 Jan 1;17(1):26-30. doi: 10.1007/BF03218597.

Sharma MB, Abdelmohsen HA, Kap O, Kilic V, Horzum N, Cheneler D. Poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) hydrogel based microneedles for bioactive release. Bioengineering (Basel). 2024 Jun 25;11(7):649. doi: 10.3390/bioengineering11070649, PMID 39061731, PMCID PMC11273839.

Zare M, Bigham A, Zare M, Luo H, Rezvani Ghomi E, Ramakrishna S. pHEMA: an overview for biomedical applications. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Jun 15;22(12):6376. doi: 10.3390/ijms22126376, PMID 34203608, PMCID PMC8232190.

Unagolla JM, Gaihre B, Jayasuriya AC. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of 3D printed poly(ethylene glycol) dimethacrylate based photocurable hydrogel platform for bone tissue engineering. Macromol Biosci. 2024 Apr;24(4):e2300414. doi: 10.1002/mabi.202300414, PMID 38035771, PMCID PMC11018466.

Burke G, Devine DM, Major I. Effect of stereolithography 3D printing on the properties of PEGDMA hydrogels. Polymers (Basel). 2020 Sep 3;12(9):2015. doi: 10.3390/polym12092015, PMID 32899341, PMCID PMC7564751.

Chang SY, Lee JZ, Sargur Ranganath AS, Ching T, Hashimoto M. Poly(ethylene-glycol)-dimethacrylate (PEGDMA) composite for stereolithographic bioprinting. Macromol Mater Eng. 2024 Aug 29;309(11). doi: 10.1002/mame.202400143.

Chang SY, Ching T, Hashimoto M. Bioprinting using PEGDMA-based hydrogel on DLP printer. Mater Today Proc. 2022 Jan 1;70:179-83. doi: 10.1016/j.matpr.2022.09.017.

Chang SY, Lee JZ, Ranganath AS, Ching T, Hashimoto M. 3D bioprinting using poly(ethylene-glycol)-dimethacrylate (PEGDMA) composite. bioRxiv. 2023 Oct 20. doi: 10.1101/2023.10.19.562790.

Killion JA, Kehoe S, Geever LM, Devine DM, Sheehan E, Boyd D. Hydrogel/bioactive glass composites for bone regeneration applications: synthesis and characterisation. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2013 Oct;33(7):4203-12. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2013.06.013, PMID 23910334.

Shah TV, Vasava DV. A glimpse of biodegradable polymers and their biomedical applications. e-Polymers. 2019 Jun 7;19(1):385-410. doi: 10.1515/epoly-2019-0041.

Chen Q, Zou B, Lai Q, Zhu K. SLA-3d printing and compressive strength of PEGDA/nHAP biomaterials. Ceramics International. 2022 Oct 15;48(20):30917-26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2022.07.047.

Healy AV, Fuenmayor E, Doran P, Geever LM, Higginbotham CL, Lyons JG. Additive manufacturing of personalized pharmaceutical dosage forms via stereolithography. Pharmaceutics. 2019 Dec 3;11(12):645. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics11120645. PMID: 31816898.

Genina N, Boetker JP, Colombo S, Harmankaya N, Rantanen J, Bohr A. Anti-tuberculosis drug combination for controlled oral delivery using 3D printed compartmental dosage forms: from drug product design to in vivo testing. J Control Release. 2017 Dec 28;268:40-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.10.003, PMID 28993169.

Shin S, Kim TH, Jeong SW, Chung SE, Lee DY, Kim DH. Development of a gastroretentive delivery system for acyclovir by 3D printing technology and its in vivo pharmacokinetic evaluation in Beagle dogs. PLOS One. 2019 May 15;14(5):e0216875. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0216875, PMID 31091273, PMCID PMC6519832.

Khaled SA, Alexander MR, Irvine DJ, Wildman RD, Wallace MJ, Sharpe S. Extrusion 3D printing of paracetamol tablets from a single formulation with tunable release profiles through control of tablet geometry. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2018 Nov;19(8):3403-13. doi: 10.1208/s12249-018-1107-z, PMID 30097806, PMCID PMC6848047.

Khaled SA, Alexander MR, Wildman RD, Wallace MJ, Sharpe S, Yoo J. 3D extrusion printing of high drug loading immediate release paracetamol tablets. Int J Pharm. 2018 Mar 1;538(1-2):223-30. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.01.024, PMID 29353082.

Okwuosa TC, Stefaniak D, Arafat B, Isreb A, Wan KW, Alhnan MA. A lower temperature FDM 3D printing for the manufacture of patient specific immediate release tablets. Pharm Res. 2016 Nov;33(11):2704-12. doi: 10.1007/s11095-016-1995-0, PMID 27506424.

Brambilla CRM, Okafor-Muo OL, Hassanin H, ElShaer A. 3DP Printing of Oral Solid Formulations: A Systematic Review. Pharmaceutics. 2021 Mar 9;13(3):358. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13030358. PMID: 33803163; PMCID: PMC8002067.

Palekar S, Nukala PK, Mishra SM, Kipping T, Patel K. Application of 3D printing technology and quality by design approach for development of age appropriate pediatric formulation of baclofen. Int J Pharm. 2019 Feb 10;556:106-16. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.11.062, PMID 30513398.

Bendicho-Lavilla C, Rodríguez-Pombo L, Januskaite P, Rial C, Alvarez-Lorenzo C, Basit AW, Goyanes A. Ensuring the quality of 3D printed medicines: Integrating a balance into a pharmaceutical printer for in-line uniformity of mass testing. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology. 2024 Feb 1;92:105337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jddst.2024.105337.

Wang J, Goyanes A, Gaisford S, Basit AW. Stereolithographic (SLA) 3D printing of oral modified-release dosage forms. Int J Pharm. 2016 Apr 30;503(1-2):207-12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2016.03.016. Epub 2016 Mar 11. PMID: 26976500.

Kadry H, Wadnap S, Xu C, Ahsan F. Digital light processing (DLP) 3D-printing technology and photoreactive polymers in fabrication of modified release tablets. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2019 Jul 1;135:60-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2019.05.008, PMID 31108205.

Allahham N, Fina F, Marcuta C, Kraschew L, Mohr W, Gaisford S. Selective laser sintering 3D printing of orally disintegrating printlets containing ondansetron. Pharmaceutics. 2020 Jan 30;12(2):110. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics12020110, PMID 32019101, PMCID PMC7076455.

Infanger S, Haemmerli A, Iliev S, Baier A, Stoyanov E, Quodbach J. Powder bed 3D-printing of highly loaded drug delivery devices with hydroxypropyl cellulose as solid binder. Int J Pharm. 2019 Jan 30;555:198-206. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.11.048. Epub 2018 Nov 17. PMID: 30458260.

Pitzanti G, Mathew E, Andrews GP, Jones DS, Lamprou DA. 3D Printing: an appealing technology for the manufacturing of solid oral dosage forms. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 2022 Oct 1;74(10):1427-49. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpp/rgab136. PMID: 34529072.

Center for Devices and Radiological Health. Technical considerations for additive manufactured medical devices. United States Food And Drug Administration; 2018. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/technical-considerations-additive-manufactured-medical-devices.

Ventola CL. Medical applications for 3D printing: current and projected uses. PT. 2014 Oct;39(10):704-11. PMID 25336867, PMCID PMC4189697.

Norman J, Madurawe RD, Moore CM, Khan MA, Khairuzzaman A. A new chapter in pharmaceutical manufacturing: 3D-printed drug products. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2017 Jan 1;108:39-50. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2016.03.001, PMID 27001902.

Bhise MG, Patel L, Patel K. 3D printed medical devices: regulatory standards and technological advancements in the usa, canada and singapore a cross-national study. Int J Pharm Investigation. 2024 Jul 1;14(3):888-902. doi: 10.5530/ijpi.14.3.99.

Minghetti P, Musazzi UM, Rocco P. Regulatory aspects of 3D printing systems in healthcare. In: fundamentals and future trends of 3D printing in drug delivery. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2025. p. 305-20. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-443-23645-7.00014-3.