Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 6, 2025, 78-89Reviewl Article

RECENT ADVANCES IN NANOCARRIERS FOR TARGETED CANCER THERAPY

MAYUR R. DANDEKAR, UMESH B. TELRANDHE, YASH SALVE, ISHA MIRZAPURE

Department of Pharmaceutical Quality Assurances, Datta Meghe College of Pharmacy DMIHER (Deemed to be University), Wardha, Maharashtra-442001, India

*Corresponding author: Kiruba Mohandoss; *Email: mayurdandekar1727@gmail.com

Received: 26 Mar 2025, Revised and Accepted: 07 Oct 2025

ABSTRACT

One treatment option is detailed re-evaluating cancer for a very innovative and efficacious form of therapy. Nanocarrier-based delivery systems have offered an impetus in the form of targeted cancer drug delivery under better drug solubility, controlled release, and selective accumulation in tumour tissue. This review intends to address the major advances in applying nanocarrier-based cancer treatment, such as liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles, dendrimers, micelles, and carbon-and inorganic nanoparticle-based medication. Every type of nanocarrier has very clear and peculiar features that determine the increase in bioavailability and tumour targeting through passive (enhanced permeability retention effect) and active targeting (ligand-receptor interactions, pH-sensitive mechanisms, and stimuli-responsive drug release). Nanocarriers, including liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles, dendrimers, and micelles, have shown significant promise in targeted cancer therapy due to their ability to improve drug solubility, prolong circulation time, and enhance site-specific delivery while minimising systemic toxicity. Among the various platforms discussed, polymeric nanoparticles-particularly those utilising biodegradable polymers like PLGA-emerged as the most promising due to their tunable surface properties, sustained drug release profiles, and favorable biocompatibility. Despite their advantages, challenges such as biological heterogeneity, off-target accumulation, and regulatory barriers hinder clinical translation. Future efforts should focus on developing smart nanocarriers capable of stimuli-responsive release and patient-specific adaptability to overcome these limitations. The future of cancer therapy can, therefore, be expected to see a fantastic horizon in patient outcomes with the integration of such innovative platforms coming from nanocarrier with personalized medicine approaches.

Keywords: Nanocarriers, Cancer therapy, Drug delivery, Targeted Therapy, Clinical advances, Future perspectives

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i6.54347 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Cancer is indeed one of the most terrible enemies of modern medicine, killing millions each year across the globe. Despite being very developed in diagnosis and treatment, conventional therapies for cancer, such as chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery, still have certain limitations. One of the major challenges of conventional chemotherapy is the lack of specificity, which results in severe systemic toxicity, multi-drug resistance, and suboptimal therapeutic outcomes. Nanotechnology has changed the scope of cancer treatment by providing an effective and advanced drug-delivery system based on nanocarrier technology that promises better targeting of the drug, fewer side effects, and better therapeutic efficacy. Nanocarriers work at the nanoscale level to carry Tumor treatment directly with antineoplastic drugs, biomolecules, and imaging agents to the tumour tissues while minimizing damage to normal cells [1]. The integration of nanotechnology in oncology has significantly improved drug solubility, bioavailability, and site-specific targeting, particularly through platforms like PEGylated liposomes and magnetic nanoparticles [2]. Each of these nanocarriers expresses different sets of physicochemical properties that can be altered to optimize therapeutic efficacy while delivering the therapeutics. For example, liposomes are vesicles composed of lipids having relatively high biocompatibility and can encapsulate both hydrophilic and hydrophobic drugs. On the other hand, polymeric nanoparticles consist of biodegradable polymers, wherein, therapeutics are sustained and controlled for release."Dendrimers come with highly branched architecture that allows for precise conjugation of drugs and univalent functionalization, while micelles are used to enhance the solubility of hydrophobic drugs." [3] Apart from functioning as drug carriers, inorganic nanoparticles such as quantum dots and gold nanoparticles may also serve as imaging agents and photothermal therapy platforms. Overall, advances in design and functionalization of these carriers have been achieved in terms of stability, biocompatibility, and tumour-targeting efficiency." The targeting of drugs is one of the prime significant paradigm shifts in cancer therapy using nanocarrier systems. Targeted nanocarriers scare away from the earlier method in chemotherapy whereby the drugs are given all over the body. Nanocarriers to track and gather specifically within tissues were designed [4]. This could be done through primarily two pathways: passive targeting and active targeting. Passive targeting is based on the EPR effect-the phenomenon in which nanoparticles preferentially accumulate within tumours as a result of leakage in the tumour-associated vasculature and impaired drainage into the lymphatics. Although the EPR effect has shown to be promising, the effect is, unfortunately, dependent on tumour type, heterogeneity in the vascular arrangement as well and the patient's factors. Designed active targeting strategies are where nanocarriers are modified with ligands like antibodies, peptides, folic acid, or aptamers that bind to overexpressed receptors on cancer cells. This receptor-receptor endocytosis eventually enhances the accumulation of the drug inside cells [5].

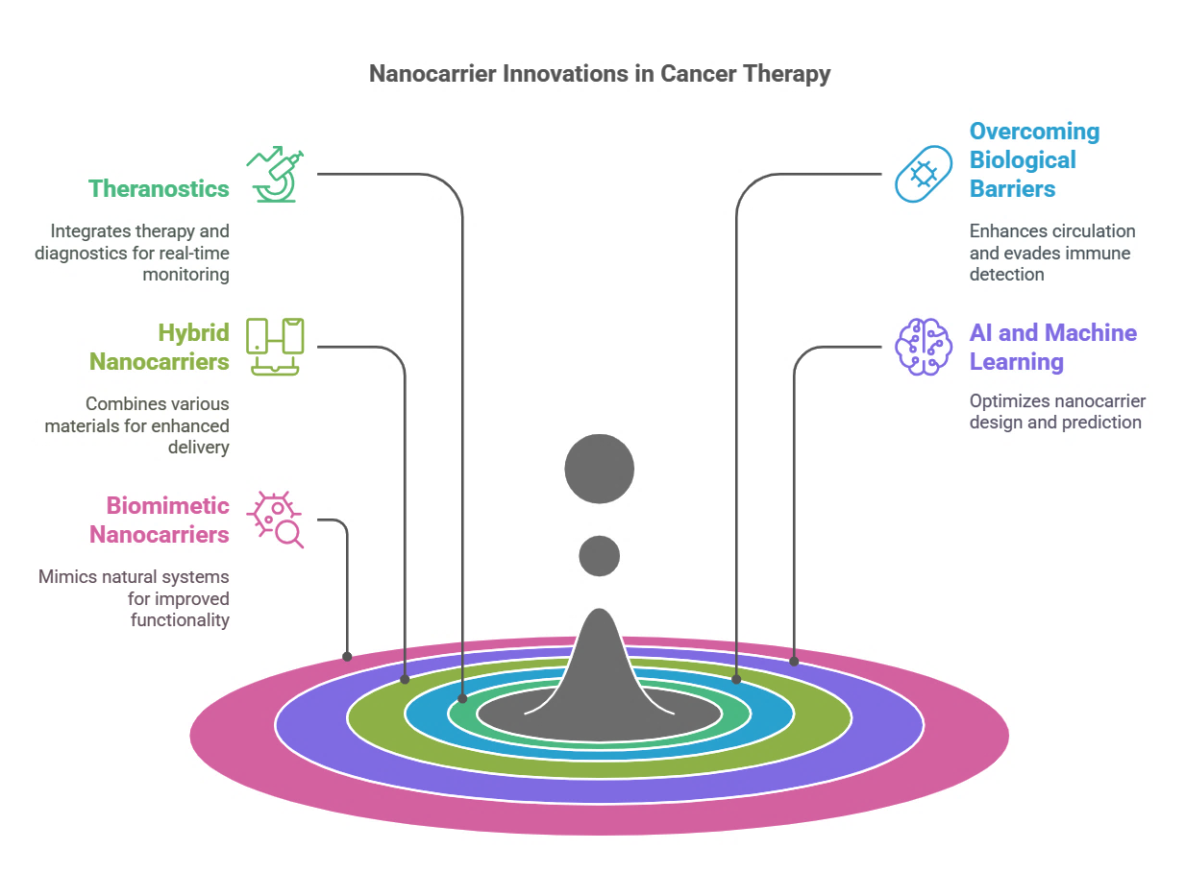

Cancer remains one of the leading causes of mortality worldwide, and conventional therapies-such as chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery-face significant limitations including non-specific toxicity, drug resistance, and poor therapeutic index. These limitations have prompted the exploration of nanocarrier-based drug delivery systems, which offer targeted delivery, enhanced bioavailability, and reduced systemic side effects [63]. It responds to various tumour microenvironment-specific stimuli such as pH, redox potential, enzymes, or temperature. For instance, there are pH-sensitive nanoparticles that can release their drug payload upon going to the acidic tumour microenvironment. The carriers will respond to elevated levels of glutathione in cancer cells in addition to triggering drug release through enzyme-sensitive nanoparticles that degrade upon contact with tumour-associated proteases. Being smart, it could acquire very precise damage for drug delivery and off-target damage [6]. This way, multifunctionality in nanocarrier designs can push nanomedicine toward the correct future for cancer therapy. The modern nanocarrier will now be designed to enable multiple therapies and diagnostics in what are called theranostics. Theranostic nanocarriers could capitalize on the drug delivery and imaging functionalities, allowing such things as real-time monitoring of drug distribution, tumour progression, and therapeutic response. For instance, gold nanoparticles can serve the function of drug delivery and photothermal properties, thereby producing localized heat by laser irradiation, which ablates tumour cells. Likewise, there are uses of targeted drug delivery as well as MRI with magnetic nanoparticles for better tracking of therapeutic outcomes. It only shows that this kind of multifunctional nanocarrier has great potential in personalizing cancer therapy, wherein the treatment would be tailored based on real-time imaging feed [7]. Targeting drugs is the most important breakthrough in this new paradigm shift in cancer therapy based on a nanocarrier system. Targeted nanocarriers avoid the earlier method in chemotherapy, in which drugs were distributed all over the body. They have been designed to track and gather specifically within tissues. This could be done through primarily two pathways: passive targeting and active targeting. Passive targeting is based on the EPR effect phenomenon in which nanoparticles preferentially accumulate within tumours as a result of leakage in the tumour-associated vasculature and impaired drainage into the lymphatics [8]. Though the EPR effect has shown to be promising, unfortunately, the effect depends on tumour type, patient factors, and heterogeneity regarding the arrangement of the vasculature. Designed active targeting strategies are where nanocarriers are modified with ligands like antibodies, peptides, folic acid, or aptamers that bind to overexpressed receptors on cancer cells. This receptor-receptor endocytosis eventually enhances the accumulation of the drug inside cells [9]. Another new idea towards nanocarrier-based cancer therapy regarding the type of different approaches is the stimulating development of highly controllable or "smart" nanocarriers. Such nanocarriers respond to specific stimuli changes occurring in the tumour microenvironment, for example, pH, redox potential, enzymes, or temperature. For instance, there are pH-sensitive nanoparticles that can release their drug payload upon going to the acidic tumour microenvironment [10]. The carriers will respond to elevated levels of glutathione in cancer cells in addition to triggering drug release through enzyme-sensitive nanoparticles that degrade upon contact with tumour-associated proteases. Being smart, it could acquire very precise damage for drug delivery and off-target damage [11]. In this context, the multifunctionality in nanocarrier design has added more avenues toward the future of nanomedicine in cancer therapy. Modern nanocarriers are now developed to help deliver multiple therapies as well as diagnostics, termed theranostics. Theranostic nanocarriers could capitalize on the drug delivery and imaging functionalities, allowing such things as real-time monitoring of drug distribution, tumour progression, and therapeutic response, such as may happen in the photothermal property of gold nanoparticles within laser irradiation ablating cells. Likewise, there are uses of targeted drug delivery as well as MRI with magnetic nanoparticles for better tracking of therapeutic outcomes. It only shows that this kind of multifunctional nanocarrier has great potential in personalizing cancer therapy, wherein the treatment would be tailored based on real-time imaging feed [12]. Even though nanoparticle carriers have made significant advances, until now, many issues have to be resolved for successful transfer to the clinics. Foremost among them is the biological fate of nanocarriers, including circulation time, biodistribution, and clearance. The human immune system is critical in the ability to recognize and remove foreign and unwanted particles [13]. With that, clearance is rapidly performed via the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS). So,defence against this can be carried out either by introducing surface characteristics, one of which is PEGylation (coating with polyethene glycol), to enhance the property of stealth, prolong naive circulation, and avoid immune detection by the host. Also, there are other challenges like stability, scalability, and even regulatory approval associated with nanocarriers, which remain a barrier to their successful translation [14]. All tumours exhibit structural differences and the dynamics of their microenvironments. For example, they differ in vascular density, hypoxia, and extracellular matrix composition, all influence their penetration by nanoparticles and drugs. Novel concepts that showed promising therapeutic efficacy incorporated recent advances in research with hybrid nanocarriers composed of various materials, thus being capable of such synergistic drug-delivery strategies. Some examples of hybrid nanocarriers include lipid-polymer hybrids and metal-organic frameworks, and they incorporate the advantages of other platforms regarding enhanced stability, targeting efficiency, and controlled drug release [15].

Fig. 1: Nanocarrier innovations in cancer therapy

The future in cancer treatment is bright with the newly developed nanocarriers, which now integrate artificial intelligence with machine learning for optimized nanocarrier design. The computational models, which are AI-driven, were able to predict with a high level of accuracy the properties regarding physicochemical characteristics, biodistribution, and therapeutic potential of the nanocarrier developed [16]. All that is left now is to make sure that nanomedicine becomes personalised and faster to develop. Coupled with that, one can also see the increased interest in biomimetic nanocarriers inspired by natural biological systems like exosomes and nanoparticles coated with cell membranes. These will also pave new ways to promote immune evasion and biocompatibility. Thus, these biomimetic routes employ the natural properties of the cellular component toward better functionality of the nanocarrier, prolonged circulation, and provide targeting [17]. Despite extensive research, several critical challenges persist in nanocarrier technology, including limited tumour penetration, variability in patient response, and scale-up manufacturing difficulties. There is a pressing need for more robust, clinically translatable nanocarriers with enhanced targeting specificity, real-time tracking capabilities, and minimal off-target effects.

Literature survey approach

To ensure a comprehensive and up-to-date review on nanocarrier-based strategies for target-specific cancer therapy, a systematic search of the literature was made. Primary databases searched were PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. Keywords and Boolean operators were the same as follows: ("nanocarriers" OR "nanoparticles") AND ("targeted drug delivery") AND ("cancer therapy" OR "oncology") AND ("liposomes" OR "dendrimers" OR "polymeric nanoparticles" OR "exosomes").

The search was confined to articles published between January 2015 and March 2025. Only peer-reviewed articles published in English were selected. Inclusion criteria encompassed studies on the recent advances, targeting mechanisms, clinical applications, and safety profiles of nanocarriers in cancer therapy. Exclusion criteria excluded non-English publications, editorials, conference abstracts, and articles lacking experimental or clinical data. The fig. used in this article have been made using data from cited literature or adapted from published sources, wherever necessary, with due credit given, or from the written permission of the copyright holders.

Search criteria

To be sure that the review provided here gives the most up-to-date and exhaustive insights, the systematic literature search was conducted via varied electronic databases such as PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and even Google Scholar. The time frame ranged from January 2015 to March 2025. The search terms consisted of combined keywords such as nanocarriers, targeted drug delivery, cancer therapy, liposomes, dendrimers, polymeric nanoparticles, and exosomes joined by Boolean operators. Only peer-reviewed English articles that offered experimental or clinical data were accepted into the review. Editorials, non-English material, and conference abstracts, on the other hand, were excluded.

Types of nanocarriers in cancer therapy

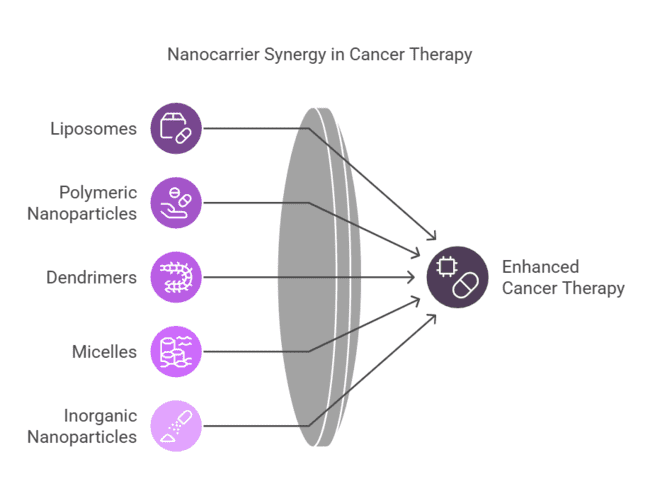

Drug delivery systems based on nanocarriers have heralded a new era of cancer therapeutics to improve solubility, optimise drug targeting, lower systemic toxicity, and provide a controlled release of therapeutic agents. The development of various types of nanocarrier platforms has enabled the delivery of chemotherapeutics, biomolecules, and imaging agents at precise sites within tumours, thus solving many of the shortcomings associated with conventional chemotherapy. Different types of studied nanocarriers include liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles, dendrimers, micelles, and inorganic nanoparticles for targeted cancer therapy. Each type of nanocarrier has dissimilar physicochemical properties that affect stability, drug-loading capacity, targeting ability, and biocompatibility; thus, design and functionalization have been continuously improved to enhance their efficacy in treating cancer [18].

Fig. 2: Nanocarrier synergy in cancer therapy

Liposomes

Recent liposomal formulations, such as Doxil® (PEGylated liposomal doxorubicin), demonstrate prolonged circulation times and reduced cardiotoxicity. However, challenges remain in scale-up production and batch-to-batch consistency. With spherical vesicles of phospholipid bilayers mimicking biological membranes, liposomes promise very efficient encapsulation and controlled drug release. The main merit of liposomes is that they can alter the pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of chemotherapeutic agents by prolonging their circulation time and reducing off-target toxicity. Many liposomal formulations have been developed to improve this therapeutic intervention. Of these, PEGylated liposomes with their liposomal surface coated with polyethene glycol are used to evade immune system recognition and prolong their systemic circulation [19]. A clinically approved example of PEGylated liposomal formulations is Doxil®, a liposomal doxorubicin, which is widely used in the treatment of ovarian cancer and Kaposi's sarcoma. Moreover, tumour targeting was enhanced by functionalizing ligand-modified liposomes, which carried antibodies, peptides, or folic acid on their surfaces [20]. Such modifications facilitate receptor-mediated endocytosis to increase drug accumulation in cancer cells. There are also stimuli-responsive liposomes designed for drug release triggered by stimuli such as pH, temperature, or enzymatic activation [21]. This is an extra control over drug delivery. For example, a pH-sensitive liposome would discharge its payload when it reached the low acidic environment characteristic of the tumour, thus achieving drug targeting with minimum systemic damage [22].

Table 1: Comparison of major nanocarriers for cancer therapy

| Nanocarrier type | Advantages | Limitations |

| Liposomes | Biocompatible, FDA-approved, capable of encapsulating hydrophilic/lipophilic drugs | Prone to leakage, short circulation time without PEGylation |

| Dendrimers | Highly branched, tunable surface, multivalent drug loading | Potential cytotoxicity, complex synthesis [65] |

| Polymeric nanoparticles | Controlled release, high stability, biodegradable (e. g., PLGA) | Possible immune response, scalability issues |

| Exosomes | Natural origin, low immunogenicity, intrinsic targeting abilities | Low yield, purification and loading challenges [66] |

Polymeric nanoparticles

Polymeric nanoparticles include biocompatible and biodegradable polymers like poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), polyethene glycol (PEG), and polycaprolactone (PCL), which have been of great interest for sustained and even controlled delivery of drugs [23]. These nanoparticles can carry a wide variety of drug molecules, such as chemotherapeutics, nucleic acids, and proteins, making them stable and bioavailable. The first and foremost advantage of polymeric nanoparticles is that their surfaces can be tailored according to requirements, which can, therefore, be functionalized with targeting ligands for enhancing specificity. For example, polymeric nanoparticles coated with transferrin or folic acid will enable selective uptake via overexpressed receptors in cancer cells, leading to targeted drug delivery [24]. pH-sensitive polymeric nanoparticles are also designed to release drugs because of the effect of the acidic tumour microenvironment, which not only improves therapeutic efficacy but also minimises off-target effects. It has also been established that polymeric nanoparticles are universal vehicles in combination therapy, where multiple drugs can be incorporated for the simultaneous delivery of therapeutic entities to overcome multidrug resistance (MDR) in cancer cells. For instance, by loading both chemotherapy drugs and small interfering RNA (sirna), drug delivery by the polymeric nanoparticle can simultaneously affect multiple oncogenic pathways and, therefore, improve the treatment outcome [25]. Recent studies indicate that there has also been much effort in introducing more functional polymeric nanocarriers based on stimulus-responsive systems, designed to release drugs under particular conditions involving tumour-associated enzymes or redox potential or external stimuli such as ultrasound or light [26]. Polymeric nanoparticles formulated with PLGA, chitosan, or PEG-PLA can encapsulate both hydrophilic (e. g., cisplatin) and hydrophobic drugs (e. g., paclitaxel), enabling controlled and sustained release profiles via degradation of the polymer matrix [61].

Dendrimers

Dendrimers comprise a class of well-defined, highly branched, nanoscale macromolecules with tunable surface chemistry suitable for delivering drugs. The well-defined structure offers a controlled method for drug encapsulation, a high drug-loading capacity, and multivalent functionalization to achieve increased targeting and controlled release. Dendrimers are engineered to carry several therapeutic agents at the same time, providing an important system for combination therapy [27]. One of the advantages of dendrimers is that they allow for the direct conjugation of drugs either covalently or non-covalently to their surface, thereby enhancing stability and bioavailability. With a multifunctional dendrimer system, drug delivery, imaging, and targeting are integrated into one platform [28]. For instance, folic acid, peptides, and antibodies have been used as targeting ligands on poly(amidoamine) (PAMAM) dendrimers to improve tumour selectivity. Also, the enzyme-responsive dendrimers will degrade in the presence of tumour-specific enzymes to achieve controlled drug release from the tumour site. Dendrimer-based drug delivery systems are currently also being developed for gene therapy, where nucleic acids such as sirna or plasmid DNA can be effectively delivered to cancer cells to silence oncogenes. Some pertinent issues, such as cytotoxicity, biodistribution, and large-scale synthesis, should be addressed to ensure suitable clinical translation of dendrimer-based nanocarriers, notwithstanding the prospects of their many applications [29].

Micelles

Polymeric micelles are self-assembled nanosized carriers obtained by amphiphilic block copolymers that have a hydrophobic core and a hydrophilic shell [30]. The nanocarriers are mainly efficient in solubilising poorly water-soluble drugs, leading to improved bioavailability and pharmacokinetics of the drug. Micelles furnish a protective environment for the hydrophobic drugs, preventing premature degradation and allowing for targeting tumour tissues. Stimuli-responsive micelles could be engineered to release drugs in response to changes in pH, redox potential, or temperature, hence improving site-specific drug delivery. Dual-targeted micelles possessing multiple targeting ligands have been designed to enhance cellular uptake and specificity [31]. Combination therapy using micelles is an emerging strategy where multiple chemotherapeutic drugs or a combination of drugs with siRNA are co-loaded into micelles to achieve a synergistic anticancer effect. Several micelle-based formulations have made it through to clinical trials with promising results in elevating therapeutic outcomes. Although much is promising, several challenges, including micelle stability, drug loading efficiency, and premature drug release, still need to be improved for clinical validation [32].

Inorganic nanoparticles

Polymeric micelles are self-assembled nanosized carriers obtained by amphiphilic block copolymers that have a hydrophobic core and a hydrophilic shell [33]. The nanocarriers are mainly efficient in solubilising poorly water-soluble drugs, leading to improved bioavailability and pharmacokinetics of the drug. Micelles furnish a protective environment for the hydrophobic drugs, preventing premature degradation and allowing for targeting tumour tissues. Stimuli-responsive micelles could be engineered to release drugs in response to changes in pH, redox potential, or temperature, hence improving site-specific drug delivery [34]. Dual-targeted micelles possessing multiple targeting ligands have been designed to enhance cellular uptake and specificity. Combination therapy using micelles is an emerging strategy where multiple chemotherapeutic drugs or a combination of drugs with siRNA are co-loaded into micelles to achieve a synergistic anticancer effect. Several micelle-based formulations have made it through to clinical trials with promising results in elevating therapeutic outcomes. Although much is promising, several challenges, including micelle stability, drug loading efficiency, and premature drug release, still need to be improved for clinical validation [35].

Exosomes as natural nanocarriers

Exosomes, nanosized extracellular vesicles secreted by most cell types, are increasingly recognised for their intrinsic targeting abilities and low immunogenicity. Their lipid bilayer structure allows them to carry diverse cargos, including proteins, mRNA, mirna, and small-molecule drugs. Unlike synthetic nanocarriers, exosomes can cross biological barriers and naturally home to specific tissues, making them attractive platforms for cancer drug delivery. However, challenges related to exosome heterogeneity, low production yield, and efficient cargo loading remain major bottlenecks for clinical translation [67].

Table 2: Targeting strategies in nanocarrier-based cancer therapy

| Targeting strategy | Mechanism | Examples | Advantages | Limitations | References |

| Passive targeting | The EPR effect enables nanocarrier accumulation in tumours | Liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles | Simple, widely used | Not effective in all tumours due to heterogeneity | [35] |

| Active targeting | Ligand-receptor interaction (e. g., folic acid, transferrin) | Antibody-conjugated nanoparticles | High specificity, improved efficacy | Costly, requires precise ligand selection | [36] |

| Stimuli-responsive targeting | pH, redox, enzyme-triggered drug release | pH-sensitive micelles | Controlled release at the tumour site | Complex design, potential off-target effects | [37] |

| Magnetic targeting | Magnetic nanoparticles guided by external fields | Iron oxide nanoparticles | Non-invasive, image-guided therapy | Requires an external magnetic field application | [38] |

| Gene therapy-based targeting | sirna, CRISPR-loaded nanoparticles | Lipid-based RNA nanocarriers | Potential for precise genetic modulation | Risk of immune response, delivery challenges | [39] |

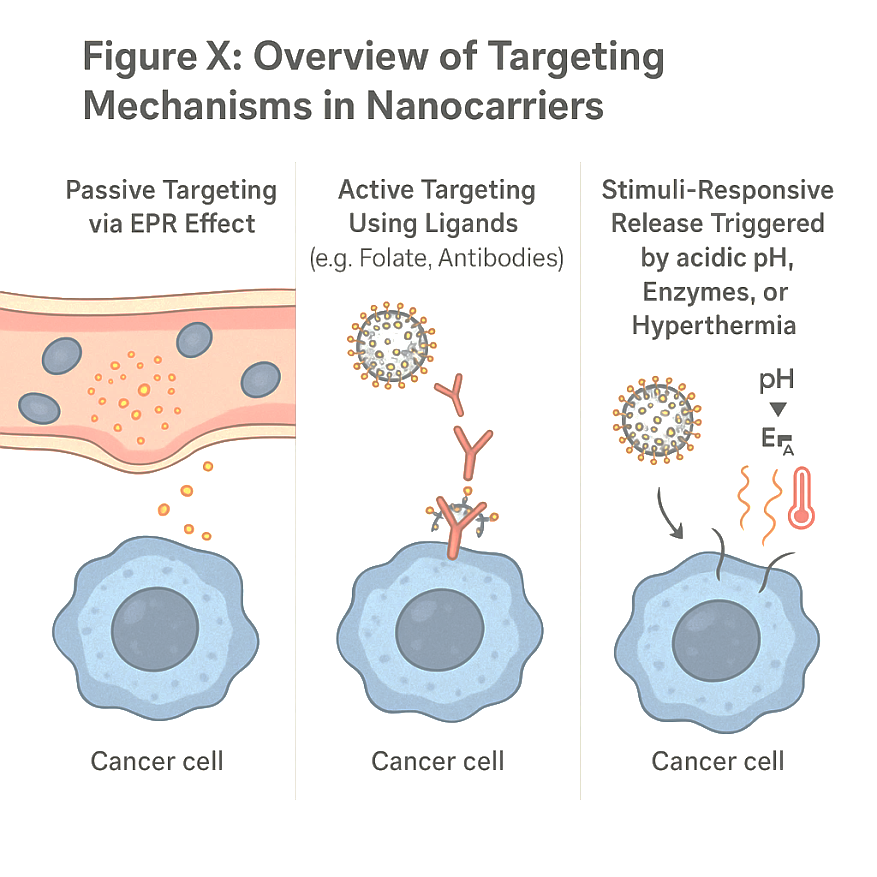

Fig. 3: Overview of targeting mechanisms in nanocarriers

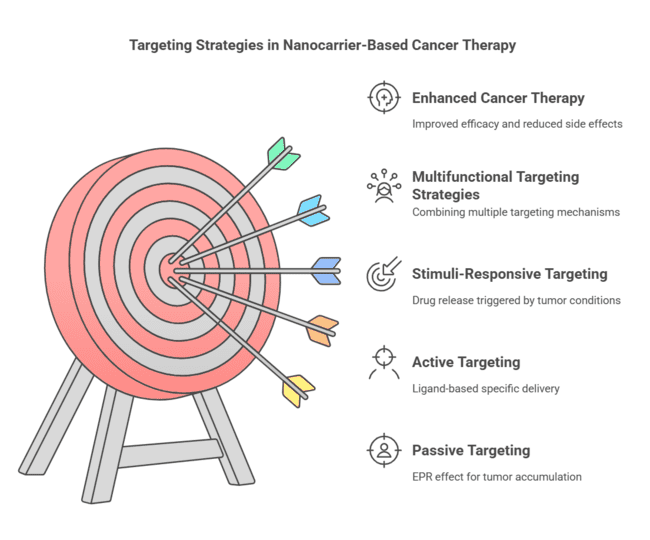

Targeting strategies in nanocarrier-based cancer therapy

Their efforts have borne much fruit so far, such as initiatives to establish a targeted drug delivery system that will provide effective cancer therapy while minimising side effects compared with conventional chemotherapy, which is non-discriminative and dispenses drugs throughout the whole body. The combination of these integrated strategies with multifunctional nanocarriers has further increased the precision and completion of cancer treatment in personalised approaches [36].

Fig. 4: Targeting strategies in nanocarrier-based cancer therapy

Passive targeting

Passive targeting is the basic principle of the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, which plays a role in the preferential accumulation of nanoparticles in tumour tissues because of their unusual architecture of tumour vasculature. Unlike normal blood vessels that contain highly regulated endothelial junctions for entry of nanoparticles from the blood into the tumour interstitium, tumour blood vessels are highly disorganised and have large fenestrations that allow nanoparticles to extravasate and accumulate in the tumour interstitium. Added to that, tumours are lymphatically poorly drained, which further contributes to the retention of the particles in the tumour site [37]. This has been consequently seen in the case of EPR-induced passive accumulation of NP-based drugs such as liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles, and micelles, and the use of homogeneous approaches to their passive accumulation in solid tumours. Some of the already clinically approved nanomedicines include Doxil® (liposomal doxorubicin) and Abraxane® (albumin-bound paclitaxel), which depend on passive targeting for their therapeutic efficacy [38]. Passive targeting leverages the Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect, characterised by leaky vasculature and poor lymphatic drainage in tumour tissues. However, its efficiency varies across tumour types and is often limited in poorly vascularized tumours [62]. Hybrid combinations of passive targeting with active and stimuli-responsive strategies are emerging to outwit this limitation by improving tumour-targeting capacity and drug delivery efficiency [39].

Active targeting

Active targeting involves functionalizing nanocarriers with ligands such as monoclonal antibodies (e. g., trastuzumab), aptamers, or peptides that bind to specific tumour-associated receptors like HER2, EGFR, or folate receptors, thereby enhancing cellular uptake via receptor-mediated endocytosis.[62] The ligand-receptor interaction thereby promotes an efficient route in the endocytosis of the receptor, ensuring effective drug delivery into the cells. Many targeting ligands, such as antibodies, peptides, aptamers, and small molecules, have been employed to enhance the specificity of nanocarrier drug delivery [40].

Antibody-based targeting

Immunonanoparticles are antibody-functionalized nanocarriers that have been proven to be good for the improvement of cancer cell recognition and uptake. The conjugation of certain mAbs to these nanoparticles improves tumour targeting. Trastuzumab (Herceptin ®) is an anti-human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) monoclonal antibody that has been used in liposomal and polymeric nanoparticle formulations to improve the treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer. Similarly, cetuximab, an anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) antibody, has been used to functionalize the nanocarrier for therapeutics targeting colorectal and head-and-neck cancers [41].

Peptide-based targeting

In reasonable speculation, one could presume that peptides change the targeting approach just because they are smaller, with very high binding affinity, and amenable to modification. There have been many studies done on peptide-functionalized carriers to target cancer cells, one of the widely studied peptides being arginine-glycine-aspartic acid (RGD). RGD-functionalized nanoparticles utilise integrins for targeting, especially αvβ3 integrins, which are highly concentrated on the tumour vasculature and cancer cells. They give nanoparticles enhanced tumour penetration and cellular uptake, leading to the maximum efficacy of the treatments. Other peptide-based targeting ligands include transferrin, folic acid, and bombesin, which have also been introduced for the selective targeted delivery of drugs into cancer cells [42].

Aptamer-based targeting

Aptamers are single-stranded DNAS or RNAs that have the potential to bind with high-affinity forces to molecular targets in a specific manner. With all the mentioned properties, such as stability, low immunogenicity, and the possibility of recognising a variety of tumour markers, aptamer-functionalized nanocarriers have been well-placed to give a good strategy for targeted cancer therapy. AS1411, an aptamer that binds nucleolin, found to be overexpressed on cancer cells, has been conjugated to nanoparticles for the selective delivery of a drug in breast and glioblastoma surgery. Aptamers against prostate-specific membrane antigens (PSMA) have likewise been integrated into nanocarriers for the targeted treatment of prostate cancer. Aptamers are versatile and very specific, thus making them promising candidates for active targeting strategies in nanomedicine [43].

Stimuli-responsive targeting

Stimuli-responsive or smart nanocarriers are those meant to release their drug payload through specific tumour microenvironmental cues such as ph, redox potential, enzymes, or even light and heat. These nanocarriers will make drug-selective delivery and, thus, therapeutic efficacy much better as it is ensured that release will occur mainly from the tumour site [44]. Stimuli-responsive nanocarriers represent a dynamic and intelligent strategy for enhancing drug delivery specificity and efficiency in cancer therapy. These systems respond to endogenous or exogenous triggers such as pH, enzymes, or temperature, exploiting the unique tumour microenvironment (TME) features.

pH-responsive nanocarriers

The acidic pH (6.5–6.8) environment of the tumour arises due to increased glycolysis accompanied by poor perfusion. Using this acidic environment as an advantage, pH-sensitive nanocarriers have acid-triggered drug release with acid-labile linkers or pH-sensitive polymers. For example, nanoparticles based on poly(β-amino ester) degrade upon exposure to acidic pH for the selective release of their drug payload in tumours. Likewise, in acidic conditions, pH-sensitive liposomes and micelles undergo destabilisation to promote site-specific drug release, thereby enhancing therapeutic efficacy [45]. Tumour tissues exhibit a slightly acidic extracellular pH (~6.5–6.8) compared to normal tissues (~7.4). pH-sensitive carriers use acid-labile bonds (e. g., hydrazone, imine, or orthoester linkages) or protonatable polymers (e. g., poly(histidine), poly(L-histidine)) to trigger drug release in acidic TME or endosomal/lysosomal compartments [68].

Temperature-sensitive nanocarriers

These systems release their cargo when exposed to elevated temperatures (~40–42 °C), typically induced by local hyperthermia. Thermoresponsive polymers like poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAM) undergo a phase transition at the target temperature, triggering controlled release [69].

Redox-responsive nanocarriers

Cancer cells tend to have higher levels of intracellular glutathione (GSH) that can be used to trigger drug release from redox-responsive nanocarriers. These nanocarriers contain disulfide linkages that are cleaved in the presence of excess GSH concentration, triggering the fast release of the encapsulated drug. Redox-responsive polymeric nanoparticles and dendrimers have been engineered for intracellular drug delivery to mitigate systemic toxicity and maximise treatment efficacy [46].

Enzyme-responsive nanocarriers

Tumour tissues typically overexpress particular enzymes, like matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and cathepsins, which can be exploited with these enzymes for enzyme-specific drug release. MMP-sensitive nanoparticles degrade in MMPs, allowing the localized targeted release of drugs at the places within the tumour. Enzyme-sensitive polymeric micelles and liposomes have also been created to improve the selectivity and penetration of drugs [47]. Certain proteases (e. g., matrix metalloproteinases, cathepsins) are overexpressed in cancer. Nanocarriers can be engineered with enzyme-cleavable peptide linkers (e. g., GPLGVRG, PLGLAG) or coatings that release drugs selectively in tumour regions with high enzymatic activity [68].

Light and heat-responsive nanocarriers

External stimuli-responsive nanocarriers present another dimension to the control of drug release. Light-responsive nanoparticles, such as gold nanoparticles and upconversion nanoparticles, release drugs under near-infrared (NIR) light exposure, allowing for specific spatio-temporal control of drug delivery. Heat-sensitive liposomes release their drug payload under mild hyperthermia (40-45 °C), thereby increasing drug accumulation at tumour sites. These strategies can be beneficial in combination therapies, such as photothermal and photodynamic therapy [48].

Multifunctional targeting strategies

In response, to enhance therapeutic efficacy, researchers have been developing multifunctional nanocarriers that possess multiple targeting mechanisms. Hybrid nanoparticles combining passive targeting, active targeting, and stimuli-responsive properties are engineered to improve the precise delivery of drugs. For example, PEGylated liposomes conjugated with various targeting ligands and pH-sensitive mechanisms of drug release offer superior tumour specificity. This class of theranostic nanocarriers is those that combine therapeutic with imaging functionality-allowing real-time monitoring of drug distribution and tumour response and supporting personalised treatment strategies [49].

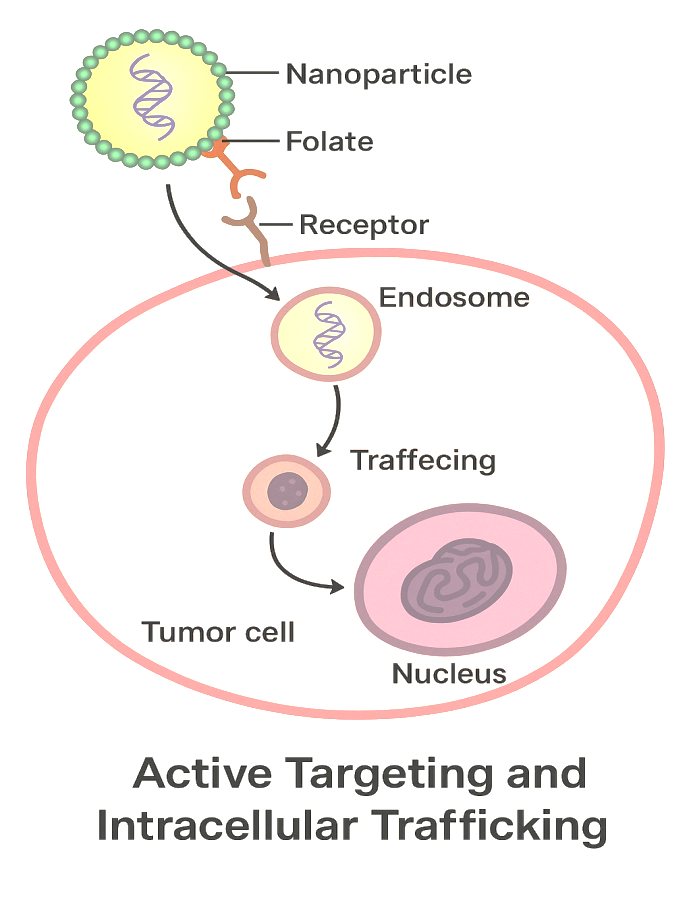

The image depicts the active targeting and intracellular trafficking of a novel nanoparticle-based drug delivery system designed to deliver therapeutic molecules directly into diseased tissue. The surface-conjugated folate ligands confer specificity for the folate receptors, which are overexpressed in tumour cells and trigger endocytosis, leading to internalisation into endosomes. Within the acidic endosomal environment, the nanoparticle escapes the endosome and liberates its therapeutic cargo-such as siRNA-into the cytoplasm. The liberated siRNA is translocated to its cell-specific site of action, such as the nucleus, for gene-silencing action. With this targeted delivery, the therapeutic effect can be increased while minimising off-target effects, making this a very promising strategy for precision cancer treatment.

Fig. 5: Active targeting and intracellular trafficking

Table 3: Recent advancements in nanocarrier-based drug delivery (2022–2024)

| Nanocarrier type | Key advancement | Study findings | Clinical stage | Reference |

| Liposomes | HER2-targeted PEGylated liposomes | 50% tumour growth inhibition in HER2+breast cancer (vs. 20% for non-targeted) | Phase II (NCT05219370) | [52] |

| Polymeric NPs | Folate-conjugated PLGA nanoparticles | 3-fold higher tumour accumulation in ovarian cancer xenografts | Phase I (NCT04879728) | [54] |

| Dendrimers | PAMAM-siRNA dendrimers | 80% oncogene silencing in liver tumours with reduced hepatotoxicity | Preclinical | [55] |

| Inorganic NPs | Gold NPs for photothermal therapy | 70% tumour regression in murine models under NIR irradiation | Phase I/II (NCT05115642) | [56] |

| Hybrid NPs | Lipid-polymer hybrids (Patisiran-like) | Improved stability (shelf-life>18 mo) and 90% drug loading efficiency | [57] |

Recent clinical advances in nanocarrier-based cancer therapy

Over the years, there are great advancements made in nanocarrier-based cancer therapy, with many formulations having moved from preclinical research into clinical trials and regulatory approvals. It addresses the urgent requirement for targeted, effective, and less toxic cancer therapies. Liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles, micelles, dendrimers, and inorganic nanoparticles have shown improved drug delivery, bioavailability, therapeutic efficacy, and reduced systemic toxicity. Approved nanomedicines benefiting this progress include Doxil® (liposomal doxorubicin), Abraxane® (albumin-bound paclitaxel), and Onivyde® (liposomal irinotecan) [70]. Nano-carrier-based cancer therapy has advanced clinically, with a few nanomedicines making their way from preclinical research to clinical trials and regulatory approval. This advancement responds to the urgent need for effective, targeted, and less-toxic cancer therapies. Liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles, micelles, dendrimers, and inorganic nanoparticles, referred to as nanocarriers, have been reported to be effective in enhancing drug delivery, bioavailability, and therapeutic efficacy while limiting systemic toxicity. Regulatory approval and clinical success have thus fostered the development of next-generation nanocarriers with enhanced functionalities, such as Doxil® (liposomal doxorubicin), Abraxane® (albumin-bound paclitaxel), and Onivyde® (liposomal irinotecan). Among the most prominent recent clinical advancements, targeted nanocarrier systems employ active targeting ligands and stimuli-responsive drug release and combination therapy approaches. Various clinical trials employ ligand-functionalized nanocarriers directed toward improving tumour selectivity. One example is HER2-targeted liposomes conjugated with trastuzumab (anti-HER2 antibody), currently being evaluated for potential breast cancer treatment. Equally, folate-conjugated polymeric nanoparticles seem promising toward improving drug delivery to folate receptor-overexpressing tumours, especially ovarian and lung cancers. Aptamer-functionalized nanoparticles utilising nucleic acid-based targeting ligands have also entered clinical trials for the selective delivery of drugs in different types of cancers. Another breakthrough in clinical nanomedicine involves the design of stimuli-responsive nanocarriers that preferentially release drugs in response to environmental cues that are tumour-specific. In addition, inorganic nanoparticles, particularly gold and mesoporous silica nanoparticles, have been clinically evaluated for PTT and theranostics. Gold nanoparticles were validated in clinical trials for their efficacy in localised hyperthermia upon near-infrared (NIR) irradiation for non-invasive cancer therapy. Theranostic nanoparticle carrier systems, which allow for the integration of diagnosis and therapy within one platform, are being tested for personalised medicine for real-time tracking of drug homing and tumour response. The challenges, however, include scaling up production, overcoming immune clearance, and navigating through regulatory barriers. Further scope of clinical success in nanocarrier-based cancer therapies is expected with the advancement of nanomedicine spurred by advanced material sciences, artificial intelligence-based drug design, and personalised medicine [51].

Critical evaluation of promising developments

Recently, the clinical trials herald advancements in nanocarriers. HER2-targeted liposomes conjugated with trastuzumab (anti-HER2 antibody) for breast cancers are now under study and display encouraging signs in improving tumour selectivity and limiting off-target effects. Furthermore, in the case of ovarian and lung cancers are folate-conjugated polymeric nanoparticles that exploit the overexpression of folate receptors in these tumours. Also, aptamer-functionalized nanoparticles using an AS1411 aptamer have moved into clinical trials for glioblastoma and breast cancer, revealing high specificity and low immunogenicity. Stimuli-responsive nanocarriers indeed belong to another breakthrough. Ph-sensitive nanoparticles and redox-responsive systems are presently being studied in early-phase trials for the selective release of drugs in the tumour microenvironment. Consequently, gold nanoparticles in photothermal therapy (PTT) have been shown efficacious for localised hyperthermia during near-infrared (NIR) irradiation and hence potential non-invasive treatment. Nonetheless, barriers still lie ahead in these advancements. Heterogeneity in the EPR effect among tumour types limits the universal applicability of passive targeting. Immune clearance and scaling concerns compromise clinical translation. For example, although PEGylation prolongs circulation time, anti-PEG immune responses have been documented, which raises questions of clinical translation towards alternative designs [70].

The role of artificial intelligence in nanocarrier design

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are emerging as powerful tools for the development of nanocarriers. AI models can predict properties of nanocarriers, including biodistribution, drug release kinetics, and tumour accumulation, and thus speed the design of optimised formulations. For example, ML algorithms analyse extensive datasets to pinpoint the best ligand-receptor pairs for active targeting or to predict the biocompatibility of new materials. AI aids personalised nanomedicine by integrating patient-specific tumour profiles in designing nanocarriers [71].

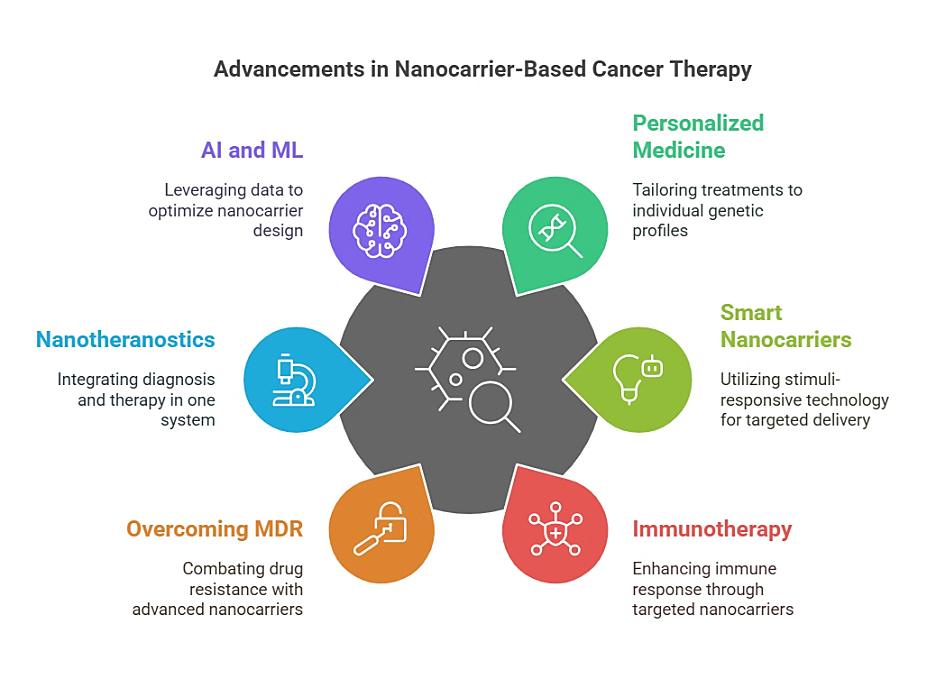

Future perspectives

However, by also including discussions on how to fund AI and nanotechnology, they offer future perspectives for overcoming existing limitations, including tumour heterogeneity and immune evasion. Other typical examples of future perspectives include biomimetic nanocarriers inspired by existing natural systems, such as exosomes, and hybrid platforms with multiple functionalities, such as in theranostics. Future advances will rely heavily on continued interdisciplinary collaboration and the resolution of regulatory hurdles, which facilitate translation into clinical practice [72].

Future perspectives in nanocarrier-based cancer therapy

Nanocarrier drug delivery systems have changed the paradigm of cancer therapy by achieving better targeting, lower systemic toxicity, and enhanced therapeutic efficacy. Despite the advances made, problems such as tumour-targeting heterogeneity, immune system interaction, large-scale manufacturing, and regulatory impediments remain to be resolved. Future studies in nanocarriers are expected to prioritise the elimination of these impediments and the incorporation of innovative technologies to improve treatment accuracy and, hence, patient outcomes. Several relevant future perspectives regarding nanocarrier-based cancer interventions are discussed in detail below.

Fig. 6: Advances in nanocarrier-based cancer therapy

Personalised nanomedicine for precision oncology

One of the most promising future avenues in nanocarrier-based cancer therapy is the much-needed integration of personalised medicine approaches. Cancer treatment is often dictated by a traditional one-size-fits-all methodology that tends to yield diminished efficacy and increased adverse effects on the treatment, mainly due to interpatient variability. With the coming of genomics, proteomics, and advanced diagnostic tools, nanocarrier constructs could be personalised to individual patients according to their tumour molecular profile-based characteristics. It essentially means designing nanocarriers with specificity for unique genetic mutations, signalling pathways, or characteristics of the tumour microenvironment for any given patient's cancer. Such an approach integrates patient-specific biomarkers with artificial intelligence (AI)-driven predictive models, enabling clinicians to tailor nanocarrier formulations to a high degree of specificity to optimise drug delivery and therapeutic response, ultimately translating into enhanced patient benefit.

Smart and stimuli-responsive nanocarriers

In the future, nanocarrier systems will become more advanced with beneficial "smart" attributes that undoubtedly target specific tumour microenvironmental cues or outside stimuli for improving drug transport. Stimuli-responsive nanocarriers can be pH-dependent, enzyme-active, redox-reductive, or respond to external forces, such as ultrasound, magnetic fields or light irradiations, to deliver therapeutically effective quantities of drugs only at the appropriate time. For example, pH-sensitive nanoparticles release their payload in the acidic environment of the tumour, thus avoiding any premature leakage of their drug content. There are redox-responsive nanoparticles that would take advantage of the high glutathione levels typically associated with cancer cells for targeted drug release within these cells. Further improvement in precision and reduction in off-target effects will be achieved by the design of dual or multi-responsive nanocarriers that will be triggered by the presence of more than one stimulus [52].

Nanocarriers for immunotherapy enhancement

Immunotherapy for cancer is an exploding field in which checkpoint inhibitors, tumour cell vaccines, and CAR T-cell therapies are changing the paradigm of cancer treatment. However, factors like tumour immune evasion and systemic immune-related adverse reactions restrict their widespread clinical applications. Nanocarriers could be one way to solve the problem by permitting the direct and accurate delivery of immunotherapeutic agents to the tumour microenvironment. For example, LNPS could encapsulate mRNA vaccines, eliciting an anti-tumour immune response. Furthermore, polymeric nanoparticles may co-deliver immune checkpoint inhibitors (anti-PD-1, anti-CTLA-4) and immunostimulatory agents that activate T cells and infiltrate the tumour. The combination of nanocarriers with immunotherapy is expected to enhance the efficacy of the treatment while reducing immune-related toxicity, ultimately leading to more successful and safer treatment strategies for malignant tumours [53].

Overcoming multidrug resistance (MDR) with advanced nanocarriers

Multidrug-resistant tumours have become a bane in cancer therapy due to their high rate of treatment failure and disease progression. Cancer cells develop multidrug resistance (MDR) mechanisms through drug efflux pumps, altered apoptosis pathways, and metabolic reprogramming. Future nanocarriers will be designed specifically to overcome this kind of functional resistance by co-encapsulating two or more therapeutic agents in a single formulation. For example, chemotherapeutic drugs and siRNA co-loaded in the nanoparticles were meant to inhibit resistance genes and induce cell death at the same time. In addition, targeting anti-MDR markers, such as P-glycoprotein (P-gp), using ligand-functionalized nanocarriers should help to increase the accumulation of drugs in resistant tumours. The combination of this nanocarrier-based delivery with a gene-editing tool like CRISPR-Cas9 presents another exciting avenue for directly modifying resistance-related genes to obtain better therapeutic outcomes.

Nanotheranostics: integrating diagnosis and therapy

Theranostic nanoparticles are nanoparticles that are used for both the diagnosis and treatment of diseases. This is a step towards real-time monitoring and personalised treatment. Such theranostic nanocarriers can be defined as nanoparticles incorporating imaging agents, quantum dots, for example, or magnetic nanoparticles or radionuclides within drug-loaded nanoparticles for simultaneous tumour imaging and therapy. Therefore, this dual property of the theranostic nanocarrier has allowed clinicians to track drug distribution and treatment response and make timely corrections. Gold nanoparticles functionalized with chemotherapeutic agents and radiolabels will provide high-resolution imaging while delivering targeted therapy. Transforming nanotheranostics will steadily and continuously lead to precision oncologies with early diagnoses in conjunction with the real-time monitoring of treatment and thus better conditions of intervention by ensuring the reproduction of better stratification results on patients for therapy optimisation [54].

Integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning

Future developments of nanocarrier-based cancer therapies will be guided by way of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML). AI models predict the drug release kinetics, biodistribution, and patterns of tumour accumulation, which will assist in the design of optimised nanocarrier formulations. ML algorithms could also analyse large datasets created from patients responding to a range of different monotherapies, identifying what might be some of the most efficacious formulations for different cancer types. It will also develop real-time treatment efficacy feedback by integrating imaging data with nanotheranostic systems using AI-powered diagnostic tools. The incorporation of AI and ML into nanomedicine research promises to fast-track the discovery and clinical translation of next-generation nanocarriers that will outshine current possibilities in terms of safety, efficacy, and personalisation [55].

Overcoming biological barriers to nanocarrier delivery

Another area of challenge in nanocarrier-based therapeutics is the mobility of biological barriers like those given by the immune system, tumour ECM, and the blood-brain barrier. Usually, using the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS), they are cast away as foreign nanoparticles by the immune system, which will ultimately reduce their therapeutic effectiveness. Future research efforts are intended at stealth nanocarriers that will be fabricated with biomimetic materials such as cell membrane camouflage or polyethene glycol (PEG) coatings to avoid immune recognition and at strategies such as enzymatic degradation of ECM components and size-switchable nanoparticles that enhance penetration through dense ECM in solid tumours to improve tumour penetration and drug delivery. For instance, novel nanocarriers that can cross the blood-brain barrier by receptor-mediated transcytosis or can be guided magnetically could prove to be a great asset in treating glioblastoma and other central nervous system malignancies [56].

Scalable manufacturing and regulatory challenges

However, to turn nanocarrier-based treatments into widespread use, much effort must go into scaling up production and seeking regulatory approval. Uniformity in the size and shape of nanocarriers, along with efficiency in drug loading, is indispensable for clinical usefulness. Microfluidics, automatic synthesis of nanoparticles, and 3D bioprinting should ensure easier, large-scale, reproducible production. The FDA and the EMA are engaged in establishing appropriate guidelines to evaluate nanomedicines. During this process, characterisation methods, toxicity assays, and long-term stability evaluation should be developed to pave the way for regulatory approval and commercialisation of new cancer therapies based on nanocarriers [57].

Bioinspired and biomimetic nanocarriers

Bio-inspired and biomimetic nanoformulations have been developed to deliver drugs toward the tumour, avoid the immune response, and enhance biocompatibility. Nanoparticles with a coating of cell membranes derived from red blood cells, platelets, or cancer cells show greater circulation stability and immune evasion properties. Exosome-based nanocarriers, vehicles for the natural transfer of biomolecules between cells, provide a very promising way for targeted drug delivery or gene therapy. Future research will continue toward biomimetic nanocarriers recreating nature's biological functions for highly efficient and specific cancer treatment [58].

Combination therapy using multi-functional nanocarriers

The merging of several types of therapy within a single nanocarrier system is an emerging method to elevate effectiveness and overcome drug resistance [59]. Multi-functional nanocarriers capable of co-delivering cells, drugs, and agents carrying one or more therapeutic modalities, including chemotherapy, immunotherapy, phototherapy, and gene therapy agents, may achieve the synaptic effect of effectively eradicating cancer. For example, a nanocarrier combining chemotherapy and PTT may promote drug penetration via hyperthermia-induced vasodilation and improved tumour drug accumulation. Future work will target the optimisation of combination therapy regimens to enable control over drug release kinetics while limiting undesired side effects using selective targeting mechanisms [60].

Regulatory progress and challenges

Translation of nanocarrier-based therapies from bench to bedside faces significant regulatory hurdles. Although many nanomedicines were approved by the FDA, such as Doxil® (liposomal doxorubicin), Abraxane® (albumin-bound paclitaxel), and Onivyde® (liposomal irinotecan), approval is a thorny path because unique characterisation requirements and safety remain part of the considerations involved [73].

The road ahead in clinical pipelines

Current clinical trials are identifying next-generation nanocarriers: NBTXR3 hefnium oxide nanoparticles are now under Phase III trial for head and neck cancers. CRLX101 polymer nanoparticles are in Phase II for ovarian cancer. These candidates target more effectively and have minimised side effects compared to classical chemotherapy methods [74].

Safety and toxicity concerns

Some of the major safety issues that require more attention are: Immunity against PEG in 40-60% of individuals. Accumulation of metal nanoparticles in the liver/spleen. Cationic polymers contribute to the activation of complement. Currently, chronic toxicity studies would be required for 6 to 12 mo to investigate this issue [74].

Innovative solutions

Becoming newer approaches that were set to combat these obstacles include: Polysarcosine coating instead of PEG. Hybridised lipid-polymer nanoparticle constructs. Improved in vitro/in vivo correlational methods. They were set to enhance safety without losing a therapeutic effect.

Future regulatory directions

Recent developments include: Updated FDA nanotechnology guidance 2023. EMA harmonisation. Standardised characterisations. These changes will allow the global development of safer and effective nanocarriers.

DISCUSSION

The area of nanoparticle-based cancer therapy has witnessed phenomenal advancements in the last few years, where research has thrived in designing drug delivery systems with better targeting, bioavailability, and control of the drug-release mechanisms. The development of liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles, dendrimers, micelles, carbon-based nanomaterials, and inorganic nanoparticles ensured multiple platforms for effective cancer treatment. While significant success on the clinical front of liposomes and polymeric nanoparticles has been achieved, there are newer hybrid nanocarriers with integrated functionalities and materials offering prospects for enhancement. Targeting has evolved into passive targeting using the enhanced permeability and retention effect in various active targeting mechanisms using receptor-mediated interactions, pH-sensitive mechanisms, and stimuli-responsive drug release. The use of antibody-functionalized nanoparticles, aptamer-based therapies, and gene delivery systems has radically improved tumour specificity to minimise off-target effects and systemic toxicity. Nonetheless, tumour heterogeneity, complex tumour microenvironments, and mechanisms of resistance remain problems to be overcome in obtaining optimal efficacy. The majority of the new advances in clinical medicine, giving us nanomedicines approved by the FDA, such as Doxil, Abraxane, or Onivyde, have not been able to seal the gap between research and clinic in terms of applying new nanocarriers, mainly because of concerns about regulations, manufacturing, and toxicity. The remaining tests on biodegradability, immunogenicity, and pharmacokinetics of nanocarriers will take a longer time before being considered safe and efficacious in patients. Furthermore, the cost and scalability of nanocarrier production present barriers to widespread clinical use. The future should hold multi-functional hybrid nanocarriers based on biodegradable materials, real-time imaging capabilities, and personalised medicine approaches for more specific treatment. This can then be supplemented with artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning knowledge to make drug formulations and optimise nanoparticle design for more effective drug delivery strategies. Personalised nanomedicine combining patient-specific tumour profiling with smart nanocarriers will also play a very important role in precision oncology. Overall, nanocarrier-based cancer therapies have shown tremendous progress thus far, but it is important to continue addressing issues concerning toxicity, large-scale production, patient-specific efficacy, and regulatory challenges for these therapies to be translated into successful clinical applications. Interdisciplinary collaborations among nanotechnologists, oncologists, and regulatory bodies will continue to be indispensable to realise the full potential of nanomedicine in oncology.

CONCLUSION

Advancements in cancer treatment using nanocarriers have shifted paradigms in oncology towards more precise, effective, and less toxic treatment modalities. These advancements in nanotechnology have provided much room to develop different kinds of nanocarriers, such as liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles, micelles, dendrimers, inorganic nanoparticles, and bioinspired carriers, all of which are showing great promise in drug delivery, bioavailability, and therapeutic efficacy. By surpassing the limitations of conventional forms of chemotherapy and radiotherapy, nanocarriers have added to the potency of specificity available in the targeting of a drug, thus guaranteeing that the therapeutic agent delivers towards the tumour site and shields the same agent from off-target effects and systemic toxicity. Advancements in nanocarrier systems-especially stimuli-responsive and targeted platforms-offer significant potential to overcome current limitations in cancer therapy. However, further studies focusing on long-term toxicity, tumour heterogeneity, and patient-specific responses are essential for successful clinical application. One of the outstanding achievements in nanocarrier-based therapy is the targeting of tumour cells through active ligand-functionalized nanoparticles. Monoclonal antibodies, peptides, aptamers, and folate receptors are laced into the nanoparticles to bind to cancer cells or permit the selective delivery of anticancer drugs to cancer cells while minimising exposure to healthy cells. Therefore, betterment in treatment outcomes and a reduction in side effects, which is one of the most critical challenges against conventional chemotherapy, can be achieved. Furthermore, these stimuli-responsive nanocarriers release their contents by specific activation from tumour-specific cues such as pH, enzyme activity, or redox conditions, hence sharpening the precision of drug delivery further. To achieve truly smart and personalised medicine, where drug release is controlled and optimised according to the tumour microenvironment, two-and multi-responsive nanocarrier platforms represent a significant step. Nanocarriers are designed to counter these mechanisms of resistance through the co-formulation of multiple therapeutic agents, in particular, chemotherapeutic drugs, small interfering RNA (sirna), and CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing components. Advanced nanocarriers targeted against MDR-related proteins such as P-glycoprotein (P-gp) are expected to increase drug accumulation in resistant tumours as well as restore drug sensitivity. Therefore, the possibility of merging gene-editing technology with nanocarriers is a paradigm shift in drug-resistant cancer treatment.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors have contributed equally

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Sahin U, Tureci O. Personalized vaccines for cancer immunotherapy. Science. 2018;359(6382):1355-60. doi: 10.1126/science.aar7112, PMID 29567706.

Brigger I, Dubernet C, Couvreur P. Nanoparticles in cancer therapy and diagnosis. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2002 Aug 29;54(5):631-51. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00044-3, PMID 12204596.

Ferrari M. Cancer nanotechnology: opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005 Mar;5(3):161-71. doi: 10.1038/nrc1566, PMID 15738981.

Shi J, Kantoff PW, Wooster R, Farokhzad OC. Cancer nanomedicine: progress challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017 Jan;17(1):20-37. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.108, PMID 27834398.

Alexis F, Pridgen E, Molnar LK, Farokhzad OC. Factors affecting the clearance and biodistribution of polymeric nanoparticles. Mol Pharm. 2008 Jul-Aug;5(4):505-15. doi: 10.1021/mp800051m, PMID 18672949.

Maeda H, Wu J, Sawa T, Matsumura Y, Hori K. Tumor vascular permeability and the EPR effect in macromolecular therapeutics: a review. J Control Release. 2000 Mar 1;65(1-2):271-84. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(99)00248-5, PMID 10699287.

Torchilin VP. Recent advances with liposomes as pharmaceutical carriers. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005 Feb;4(2):145-60. doi: 10.1038/nrd1632, PMID 15688077.

Allen TM, Cullis PR. Liposomal drug delivery systems: from concept to clinical applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013 Jan;65(1):36-48. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.09.037, PMID 23036225.

Wang AZ, Langer R, Farokhzad OC. Nanoparticle delivery of cancer drugs. Annu Rev Med. 2012;63:185-98. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-040210-162544, PMID 21888516.

Petros RA, De Simone JM. Strategies in the design of nanoparticles for therapeutic applications. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010 Aug;9(8):615-27. doi: 10.1038/nrd2591, PMID 20616808.

Dhar S, Gu FX, Langer R, Farokhzad OC, Lippard SJ. Targeted delivery of cisplatin to prostate cancer cells by aptamer functionalized Pt(IV) prodrug-PLGA-PEG nanoparticles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008 Nov 11;105(45):17356-61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809154105, PMID 18978032.

Tran S, De Giovanni PJ, Piel B, Rai P. Cancer nanomedicine: a review of recent success and perspectives. Cancer Nanotechnol. 2017;8(1):5. doi: 10.1186/s40169‑017‑0175‑0.

Hare JI, Lammers T, Ashford MB, Puri S, Storm G, Barry ST. Challenges and strategies in anti-cancer nanomedicine development: an industry perspective. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2017 Jul;108:25-38. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2016.04.025, PMID 27137110.

Fang J, Nakamura H, Maeda H. The EPR effect: unique features of tumor blood vessels for drug delivery factors involved and limitations and augmentation of the effect. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2011 Mar;63(3):136-51. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.04.009, PMID 20441782.

Blanco E, Shen H, Ferrari M. Principles of nanoparticle design for overcoming biological barriers to drug delivery. Nat Biotechnol. 2015 Sep;33(9):941-51. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3330, PMID 26348965.

Matsumura Y, Maeda H. A new concept for macromolecular therapeutics in cancer chemotherapy: mechanism of tumoritropic accumulation of proteins and the antitumor agent SMANCS. Cancer Res. 1986 Dec 1;46(12 Pt 1):6387-92. PMID 2946403.

Choi KY, Swierczewska M, Lee S, Chen X. Protease activated drug development. Theranostics. 2012;2(2):156-78. doi: 10.7150/thno.4068, PMID 22400063.

Min Y, Caster JM, Eblan MJ, Wang AZ. Clinical translation of nanomedicine. Chem Rev. 2015 Oct 14;115(19):11147-90. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00116, PMID 26088284.

Shi J, Votruba AR, Farokhzad OC, Langer R. Nanotechnology in drug delivery and tissue engineering: from discovery to applications. Nano Lett. 2010 Sep 8;10(9):3223-30. doi: 10.1021/nl102184c, PMID 20726522.

Bobo D, Robinson KJ, Islam J, Thurecht KJ, Corrie SR. Nanoparticle based medicines: a review of FDA-approved materials and clinical trials to date. Pharm Res. 2016 Oct;33(10):2373-87. doi: 10.1007/s11095-016-1958-5, PMID 27299311.

Kunjachan S, Ehling J, Storm G, Kiessling F, Lammers T. Noninvasive imaging of nanomedicines and nanotheranostics: principles progress and prospects. Chem Rev. 2015 Oct 14;115(19):10907-37. doi: 10.1021/cr500314d, PMID 26166537.

Bertrand N, Wu J, Xu X, Kamaly N, Farokhzad OC. Cancer nanotechnology: the impact of passive and active targeting in the era of modern cancer biology. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2014 Apr;66:2-25. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2013.11.009, PMID 24270007.

Wilhelm S, Tavares AJ, Dai Q, Ohta S, Audet J, Dvorak HF. Analysis of nanoparticle delivery to tumours. Nat Rev Mater. 2016 May 3;1(5):16014. doi: 10.1038/natrevmats.2016.14.

Sanna V, Pala N, Sechi M. Targeted therapy using nanotechnology: focus on cancer. Int J Nanomedicine. 2014;9:467-83. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S36654, PMID 24531078.

Wicki A, Witzigmann D, Balasubramanian V, Huwyler J. Nanomedicine in cancer therapy: challenges opportunities and clinical applications. J Control Release. 2015 Jul 28;200:138-57. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.12.030, PMID 25545217.

Jain RK, Stylianopoulos T. Delivering nanomedicine to solid tumors. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2010 Nov;7(11):653-64. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.139, PMID 20838415.

Bae YH, Park K. Targeted drug delivery to tumors: myths reality and possibility. J Control Release. 2011 Apr 10;153(3):198-205. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.06.001, PMID 21663778.

Kamaly N, Yameen B, Wu J, Farokhzad OC. Degradable controlled release polymers and polymeric nanoparticles: mechanisms of controlling drug release. Chem Rev. 2016 Jan 13;116(4):2602-63. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00346, PMID 26854975.

Dai L, Zhou R, Zhang J, Wang Q, Meng M, Jin G. Redox responsive polymeric nanomedicine for cancer therapy. Front Chem. 2021 Jan 22;8:746.

Luo YL, Shiao YS, Huang YF. Release of photoactivatable drugs from plasmonic nanoparticles for targeted cancer therapy. ACS Nano. 2011 Nov 22;5(10):7796-804. doi: 10.1021/nn201592s, PMID 21942498.

Karimi M, Sahandi Zangabad P, Baghaee Ravari S, Ghazadeh M, Mirshekari H, Hamblin MR. Smart nanostructures for cargo delivery: uncaging and activating by light. J Am Chem Soc. 2017 Mar 29;139(13):4584-610. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b08313, PMID 28192672.

Wang X, Niu D, Li P, Wu Q, Bo X, Hou Y. Multifunctional mesoporous silica nanocomposites for magnetic targeted and pH-sensitive drug delivery. J Mater Chem B. 2015;3(22):4691-703.

Agrawal U, Gupta M, Vyas SP. Cancer nanotechnology: barriers challenges and misconceptions. Ther Deliv. 2011 Dec;2(12):1515-34.

Ma X, Yao M, Gao Y, Yue Y, Li Y, Zhang T. Functional immune cell derived exosomes engineered for the trilogy of radiotherapy sensitization. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2022;9(23):e2106031. doi: 10.1002/advs.202106031, PMID 35715382.

Ghosh PS, Kim CK, Han G, Forbes NS, Rotello VM. Efficient gene delivery vectors by tuning the surface charge density of amino acid functionalized gold nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 2008 Nov 25;2(11):2213-8. doi: 10.1021/nn800507t, PMID 19206385.

Blanco E, Kessinger CW, Sumer BD, Gao J. Multifunctional micellar nanocarriers for tumour-targeted drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2009 Mar;6(3):343-54. doi: 10.3181/0808-MR-250.

Farokhzad OC, Jon S, Khademhosseini A, Tran TN, Lavan DA, Langer R. Nanoparticle aptamer bioconjugates: a new approach for targeting prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2004 Aug 1;64(21):7668-72. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2550, PMID 15520166.

Ruan S, Xie R, Qin L, Yu M, Xiao W, Hu C. Aggregable nanoparticles enabled chemotherapy and autophagy inhibition combined with anti-PD-L1 antibody for improved glioma treatment. Nano Lett. 2019 Feb 13;19(11):8318-32. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.9b03968, PMID 31610656.

Zhang RX, Wong HL, Xue HY, Eoh JY, Wu XY. Nanomedicine of synergistic drug combinations for cancer therapy strategies and perspectives. J Control Release. 2016 Jan 28;240:489-503. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.06.012, PMID 27287891.

Xu X, Ho W, Zhang X, Bertrand N, Farokhzad OC. Cancer nanomedicine: from targeted delivery to combination therapy. Trends Mol Med. 2015 Apr;21(4):223-32. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2015.01.001, PMID 25656384.

Zhuang J, Young AP, Xiong MP. Development of anticancer peptide drug conjugates for targeted drug delivery. Ther Deliv. 2016 Jan;7(1):9-26.

Kim JY, Choi WI, Kim M, Tae G. Tumour homing size tunable clustered nanoparticles for anticancer therapeutics. ACS Nano. 2014 Jan 28;8(1):935-45.

Lammers T, Aime S, Hennink WE, Storm G, Kiessling F. Theranostic nanomedicine. Acc Chem Res. 2011 Oct 18;44(10):1029-38. doi: 10.1021/ar200019c, PMID 21545096.

Kelkar SS, Reineke TM. Theranostics: combining imaging and therapy. Bioconjug Chem. 2011 Oct 19;22(10):1879-903. doi: 10.1021/bc200151q, PMID 21830812.

Fan W, Yung B, Huang P, Chen X. Nanotechnology for multimodal synergistic cancer therapy. Chem Rev. 2017 Jan 11;117(22):13566-638. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00258, PMID 29048884.

Conde J, Dias JT, Grazu V, Moros M, Baptista PV, De La Fuente JM. Revisiting 30 years of biofunctionalization and surface chemistry of inorganic nanoparticles for nanomedicine. Front Chem. 2014 Apr 28;2:48. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2014.00048, PMID 25077142.

Park J, Choi Y, Chang H, Um W, Ryu JH, Kwon IC. Alliance with EPR effect: combined strategies to improve the EPR effect in the tumor microenvironment. Theranostics. 2019;9(26):8073-90. doi: 10.7150/thno.37198, PMID 31754382.

Albanese A, Tang PS, Chan WC. The effect of nanoparticle size shape and surface chemistry on biological systems. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2012 Aug 15;14:1-16. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-071811-150124, PMID 22524388.

Li SD, Huang L. Pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of nanoparticles. Mol Pharm. 2008 May-Jun;5(4):496-504. doi: 10.1021/mp800049w, PMID 18611037.

Harris JM, Chess RB. Effect of pegylation on pharmaceuticals. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003 Mar;2(3):214-21. doi: 10.1038/nrd1033, PMID 12612647.

Ventola CL. The nanomedicine revolution: part 1: Emerging concepts. PT. 2012 Oct;37(9):512-25. PMID 23066345.

Parveen S, Misra R, Sahoo SK. Nanoparticles: a boon to drug delivery therapeutics diagnostics and imaging. Nanomedicine. 2012 Jan;8(2):147-66. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2011.05.016, PMID 21703993.

Wang Y, Kohane DS, Langer R. Smart and multifunctional nanocarriers for precision oncology. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2022;21(7):524-47. doi: 10.1038/s41573-022-00403-y.

Riehemann K, Schneider SW, Luger TA, Godin B, Ferrari M, Fuchs H. Nanomedicine challenge and perspectives. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2009;48(5):872-97. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802585, PMID 19142939.

Zhang L, Gu FX, Chan JM, Wang AZ, Langer RS, Farokhzad OC. Nanoparticles in medicine: therapeutic applications and developments. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008 May;83(5):761-9. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100400, PMID 17957183.

Ferrari M. Cancer nanotechnology: opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005 Mar;5(3):161-71. doi: 10.1038/nrc1566, PMID 15738981.

Brannon Peppas L, Blanchette JO. Nanoparticle and targeted systems for cancer therapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2004;56(11):1649-59. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2004.02.014, PMID 15350294.

Chen G, Roy I, Yang C, Prasad PN. Theranostic nanomedicine for cancer. Nat Biomed Eng. 2023;7(2):113-28. doi: 10.1038/s41551-022-00963-2.

Davis ME, Chen ZG, Shin DM. Nanoparticle therapeutics: an emerging treatment modality for cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008 Sep;7(9):771-82. doi: 10.1038/nrd2614, PMID 18758474.

Duncan R, Gaspar R. Nanomedicine(s) under the microscope. Mol Pharm. 2011 Oct 3;8(6):2101-41. doi: 10.1021/mp200394t, PMID 21974749.

Farokhzad OC, Langer R. Impact of nanotechnology on drug delivery. ACS Nano. 2009 Jan 27;3(1):16-20. doi: 10.1021/nn900002m, PMID 19206243.

Cheng CJ, Tietjen GT, Saucier Sawyer JK, Saltzman WM. A holistic approach to targeting disease with polymeric nanoparticles. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2015 Apr;14(4):239-47. doi: 10.1038/nrd4503, PMID 25598505.

Blanco E, Shen H, Ferrari M. Principles of nanoparticle design for overcoming biological barriers to drug delivery. Nat Biotechnol. 2015 Sep;33(9):941-51. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3330, PMID 26348965.

Zhang L, Chan JM, Gu FX, Rhee JW, Wang AZ, Radovic Moreno AF. Self-assembled lipid polymer hybrid nanoparticles: a robust drug delivery platform. ACS Nano. 2008 Aug 26;2(8):1696-702. doi: 10.1021/nn800275r, PMID 19206374.

Park K. Facing the truth about nanotechnology in drug delivery. ACS Nano. 2013 Sep 24;7(9):7442-7. doi: 10.1021/nn404501g, PMID 24490875.

Petros RA, DeSimone JM. Strategies in the design of nanoparticles for therapeutic applications. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010 Aug;9(8):615-27. doi: 10.1038/nrd2591, PMID 20616808.

Bobo D, Robinson KJ, Islam J, Thurecht KJ, Corrie SR. Nanoparticle based medicines: a review of FDA-approved materials and clinical trials to date. Pharm Res. 2016 Oct;33(10):2373-87. doi: 10.1007/s11095-016-1958-5, PMID 27299311.

Panyam J, Labhasetwar V. Biodegradable nanoparticles for drug and gene delivery to cells and tissue. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2003 Feb 10;55(3):329-47. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00228-4, PMID 12628320.

Allen TM, Cullis PR. Liposomal drug delivery systems: from concept to clinical applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013 Dec;65(1):36-48. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.09.037, PMID 23036225.

Immordino ML, Dosio F, Cattel L. Stealth liposomes: review of the basic science rationale and clinical applications existing and potential. Int J Nanomedicine. 2006;1(3):297-315. PMID 17717971.

Zhang Y, Chan HF, Leong KW. Advanced materials and processing for drug delivery: the past and the future. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013 Dec;65(1):104-20. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.10.003, PMID 23088863.

Torchilin VP. Recent advances with liposomes as pharmaceutical carriers. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005 Feb;4(2):145-60. doi: 10.1038/nrd1632, PMID 15688077.

Mehnert W, Mader K. Solid lipid nanoparticles: production characterization and applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001 Apr 23;47(2-3):165-96. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00105-3, PMID 11311991.

Dontha S. A review on antioxidant methods. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2016 Oct;9(2):14-32. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2016.v9s2.13092.

Kumar A, Kumar B, Singh SK, Kaur B, Singh S. A review on phytosomes: novel approach for herbal phytochemicals. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2017 Oct 1;10(10):41-7. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2017.v10i10.20424.