Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 6, 2025, 560-567Original Article

INVESTIGATING THE ROLE OF PROBIOTICS AND SHORT-CHAIN FATTY ACIDS (SCFAs) IN MODULATING LEPTIN FOR IMPROVED ANTI-DIABETIC EFFECTS IN STREPTOZOTOCIN-NICOTINAMIDE INDUCED TYPE II DIABETES IN RATS

P. RAJYALAKSHMI DEVI1, MOTE SRINATH2, B. MAHESHWARI REDDY3, KOPPALA R. V. S. CHAITANYA4, M. VINYAS1*

1*,Department of Pharmacology, GITAM School of Pharmacy, GITAM Deemed to be University, Hyderabad, India. 1*,4Department of Pharmacology, Sarojini Naidu Vanita Pharmacy Maha Vidyalaya Tarnaka, Secunderabad, India. 2Viral Research and Diagnostic Laboratory, Department of Microbiology, Osmania Medical College, Hyderabad, India. 3Joginapally B. R Pharmacy College, Yenkapally, Moinabad, India

*Corresponding author: M. Vinyas; *Email: vmayasa@gitam.edu

Received: 28 Mar 2025, Revised and Accepted: 17 Sep 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: The gut microbiota, such as Lactobacillus rhamnosus and Bifidobacteriumlongum produces short-chain fatty acids like acetate, propionate, and butyrate from fermentation of undigested fiber, holds promise for managing metabolic diseases, including type II diabetes and obesity. This study explores the potential of probiotics and short-chain fatty acids to modulate leptin for increased anti-diabetic action in rats, offering hope for future diabetes management strategies.

Methods: Rats weighing 150 and 200 g were chosen for the study, divided into multiple groups, and given a single dose of nicotinamide and streptozotocin to induce type II diabetes. Probiotics, butyrate, propionate, and glibenclamide were continually given to respective groups after the induction of Type II diabetes. Every week, the animal's body weight was determined. Following the study's conclusion, blood was drawn via retro-orbital puncture to test the following parameters: insulin, leptin, lipid, liver, and kidney profiles. Liver and pancreas were isolated for histopathological analysis.

Results: In rats with type II diabetes, fasting blood glucose levels were significantly increased (p<0.001) compared with the normal control group, accompanied by a marked reduction in fasting insulin and leptin levels (p<0.001). Treatment with selected probiotics, butyrate, and propionate caused a significant reduction in blood glucose (p<0.001) and a significant increase in fasting insulin and leptin levels (p<0.001), indicating improved pancreatic function relative to diabetic controls. Diabetic rats displayed severe diabetic dyslipidaemia, with elevated atherogenic lipoproteins and reduced HDL-C (p<0.001). Administration of probiotics, butyrate, and propionate led to a significant reduction in atherogenic lipid levels (p<0.01) and a marked increase in HDL-C compared with diabetic controls. Liver and kidney function markers were significantly elevated in diabetic control rats (p<0.01), whereas these elevations were notably reduced (p<0.01) in all treatment groups. Among these, the combination of butyrate and probiotics exhibited the most pronounced therapeutic benefits (p<0.001 vs. other treatments). Histopathological evaluation revealed severe hepatic and pancreatic abnormalities in diabetic controls, whereas treatment groups exhibited restoration of normal tissue architecture. Notably, butyrate-treated rats showed prominent β-cell hyperplasia and hypertrophy, further supporting enhanced pancreatic regeneration and overall therapeutic efficacy.

Conclusion: This finding suggested that butyrate, in combination with probiotics, has more anti-diabetic effects than individual treatment by increasing the levels of Leptin. These results could potentially lead to the development of novel therapeutic strategies for managing type II diabetes.

Keywords: Type II diabetes, Leptin, Probiotics, Butyrate, Wistar albino rats

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i6.54383 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a growing public health issue, particularly in low-and middle-income countries where urbanization, lifestyle changes, and dietary shifts have increased disease prevalence. Type 2 DM (T2DM), accounting for ~90% of DM cases, is marked by insulin resistance and progressive β-cell dysfunction, leading to chronic hyperglycemia and metabolic complications [1, 2]. By 2030, 80% of global diabetes cases are expected in low-and middle-income nations [3]. DM is among the top six global causes of death and is associated with multiple systemic complications. Recent interest has focused on the gut microbiome's role in T2DM, especially short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like acetate, propionate, and butyrate, which are produced by microbial fermentation of dietary fiber and influence metabolism, immunity, and gut integrity [4].

Leptin resistance, a contributor to insulin resistance, impairs appetite and glucose regulation. SCFAs improve leptin sensitivity by reducing inflammation and restoring hypothalamic signalling [5], enhancing leptin receptor expression and gut barrier integrity [6]. Increasing butyrate-producing bacteria through diet or probiotics may reduce leptin resistance and improve glucose metabolism in T2DM [7]. This highlights the gut-brain-pancreas axis as a novel therapeutic target.

Clinical trials have shown that butyrate supplementation can improve insulin sensitivity and lipid profiles and reduce inflammation in T2DM patients. This underscores the potential of SCFAs, especially butyrate, in managing metabolic and inflammatory diseases, including T2DM, ulcerative colitis, and Crohn's disease. These findings offer optimism for the development of future treatments for T2DM.

SCFAs act through G-protein-coupled receptors (GPR41, GPR43) to regulate metabolism [13]. In adipose tissue, SCFAs promote leptin secretion [14] and, in the gut, stimulate GLP-1 and PYY release [15]. In hepatocytes, it activates PPARs, aiding cholesterol and triglyceride regulation [16]. Butyrate is primarily produced in the colon through fermentation of dietary fibers like resistant starch [17], with colonic concentrations of 10–20 mmol/kg and plasma levels of 50–200 µM, depending on diet and microbiota [18].

Fiber-rich diets enhance SCFA production, improving gut and metabolic health. Supplementation with butyrate has been shown to improve insulin sensitivity, reduce inflammation, and positively influence lipid profiles in T2DM [19]. These benefits emphasize SCFA potential in T2DM management, though further studies are needed to clarify mechanisms and optimize clinical use [20].

Probiotic strains such as Lactobacillus rhamnosus and Bifidobacteriumlongum boost SCFA production and microbial diversity [21]. Their growth is supported by prebiotics like inulin and resistant starch, enhancing SCFA synthesis [22]. These probiotics help maintain gut homeostasis via cross-feeding, immune modulation, and metabolic regulation, further supporting their therapeutic value. The present study aimed to investigate the effects of probiotics in combination with SCFAs (butyrate and propionate) on leptin modulation, glycemic control, lipid profile, and histopathological changes in a streptozotocin–nicotinamide-induced type II diabetes rat model, in order to explore their potential in enhancing anti-diabetic activity [23].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) SCFAs are organic monocarboxylic compounds with an aliphatic chain containing one to six carbon atoms, including propionate and butyrate. Highly soluble sodium salts of butyrate and propionate with 98.5% purity were procured from UV Scientifics (Telangana, India).

Probiotics

A selection of probiotic strains, including Bifidobacterium longum and Lactobacillus rhamnosus, were procured from INLIFE Health Care (Telangana, India). Each probiotic capsule contained a standardized concentration of 106 colony-forming units (CFU) per strain, administered orally daily once for 28 d [24, 25]. The viability of these strains was confirmed through colony formation on solid agar media, following established microbiological protocols [26, 27].

Experimental animals and diet

Wistar albino rats (150–200 g) were procured from Mahaveer Enterprises, Hyderabad, Telangana, India and acclimatized under standard laboratory conditions. The National Institute of Nutrition (NIN), Hyderabad, Telangana, India supplied a standard pellet diet. Animals were housed in polypropylene cages in a controlled environment with a 12:12 h light-dark cycle, ambient temperature maintained at 25±2 °C, and relative humidity of approximately 65%, as per the guidelines prescribed by the Committee for the Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals (CCSEA) [28]. Prior to the commencement of the experiment, all animals were allowed a 7 d acclimatization period with ad libitum access to food and water. This adaptation period stabilizes physiological parameters and minimizes experimental variability, critical for preclinical metabolic studies [29]. The standard pellet diet provided by NIN was specifically chosen for its balanced nutritional content and suitability for metabolic studies.

Every experimental protocol was approved by the IAEC of SNVPMV, which is situated in Tarnaka, Secunderabad, Telangana, India (registered under CCSEA No: 287/R/S/2000/CPCSEA, IAEC No: SNV/10/2023/PC/23).

Experimental design

The animals were randomly divided into six groups, each with six Wistar rats. Group 1 (G1) was administered a standard pellet diet formulated to meet the vitamin and mineral requirements according to the AIN-93 guidelines. Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) was induced in the remaining groups using a single intraperitoneal injection of streptozotocin (STZ; 55 mg/kg), followed by nicotinamide (120 mg/kg) administered after 15 min, as per validated models for mimicking insulin resistance and partial β-cell dysfunction in rodents [30]. To avoid hypoglycaemic shock, all rats received a 10% glucose solution orally six hours after the STZ injection [31]. Rats were fasted for 12 h prior to the induction protocol. Only those animals with fasting serum glucose levels ≥200 mg/dl after 72 h were considered diabetic and included in the experimental study [32].

To deplete gut microbiota in Groups 4, 5, and 6, a combination of broad-spectrum antibiotics (ampicillin, neomycin, metronidazole) was administered orally for three consecutive days, commonly used to suppress intestinal bacterial populations [33]. Fecal samples were subsequently collected, homogenized in sterile PBS, and cultured on nutrient agar to confirm microbial depletion, with plates incubated at 37 °C for 24 h under aerobic conditions.

Table 1: Animal grouping anti diabetic activity

| Species | Group | Treatment | Dose and route of administration |

Wistar Albino rats (150-180g) 6 animals in each group |

1 | Saline (negative control) | PO |

| 2 | Streptozotocin+Nicotinamide (positive control) | 55 mg/kg ip+120 mg/kg ip | |

| 3 | Streptozotocin+Nicotinamide+Glibenclamide | 55 mg/kg ip+120 mg/kg ip+5 mg/kg PO | |

| 4 | Streptozotocin+Nicotinamide+Probiotics | 55 mg/kg ip+120 mg/kg, ip+106 CFU/PO | |

| 5 | Streptozotocin+Nicotinamide+Probiotics+Sod. Butyrate | 55 mg/kg ip+120 mg/kg ip+106 CFU/P. O+400 mg/kg/PO | |

| 6 | Streptozotocin+Nicotinamide+Probiotics+Sod. Propionate | 55 mg/kg ip+120 mg/kg ip+106 CFU/PO+400 mg/kg/PO | |

| 7 | Streptozotocin+Nicotinamide+Sod. Butyrate | 55 mg/kg ip+120 mg/kg ip+400 mg/kg/PO | |

| 8 | Streptozotocin+Nicotinamide+Sod. Propionate | 55 mg/kg ip+120 mg/kg ip+400 mg/kg/PO |

Evaluation of biochemical parameters

Blood samples were drawn from overnight-fasted animals using the retro-orbital puncture technique under 2% anesthesia, ensuring minimal stress during collection [35]. Blood samples were centrifuged at 2500 rpm for 15 min to obtain plasma and serum in two separate vials [36]. The collected serum was stored at-20 °C for subsequent biochemical analysis. Parameters evaluated included BGL, insulin, HbA1C, haemoglobin, lipid profile (LDL, HDL, total cholesterol, and VLDL), liver function markers, renal profile, and leptin levels, which serve as key indicators of metabolic alterations in obesity and diabetes models.

Measurement of liver marker

Liver function markers, including Aspartate Aminotransferase (AST), Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT), and Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP), were quantified using analytical kit-based techniques with a semi-auto analyser, strictly following the manufacturer’s protocol. These markers are essential for evaluating hepatic damage and metabolic dysfunction associated with obesity and insulin resistance [37].

Evaluation of serum leptin and insulin levels

To estimate fasting insulin and serum leptin levels, rats were subjected to overnight fasting, and blood samples were obtained through retro-orbital puncture. The collected samples were sent to Micron Life Sciences (Hyderabad, Telangana, India) for quantitative analysis, aiding in assessing adiposity and insulin sensitivity in experimental models of obesity and diabetes.

Histopathological studies

Histopathological analyses were performed on organs such as the pancreas and liver. The main organs were removed surgically and submerged in a 10% formalin solution. Samples were sent to R R Histology, Peerzadiguda, Hyderabad, Telangana, India, for histopathological estimation.

Statistical analysis

Mean±Standard Deviation was the display of the computation's findings. The collected information was assessed using a one-way ANOVA to find significant differences. Significant group differences were assessed using Dunnett's t-test. The results showed a significant p<0.05. Graph Pad in Stat Version 3.06 (Graph Pad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) and Microsoft Excel 2013 Standard (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA) were used for data visualization and statistical analysis.

RESULTS

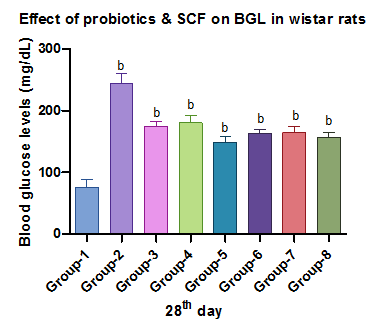

Blood glucose level

This study evaluated probiotics and SCFAs in STZ-nicotinamide-induced diabetic rats, showing significant glucose reduction over 28 d. The butyrate-probiotic combo had the most potent effect, comparable to early glibenclamide response.

Fig. 1: Effect of probiotics and SCFAs on BGL, Each value represents mean ±SD with n=6. Data were analyzed using ANOVA, followed by Dunnett's multiple comparison test. Positive control was compared with other groups: b indicates p<0.001

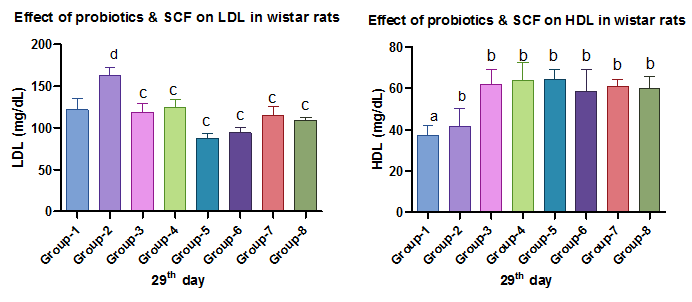

Lipid profile

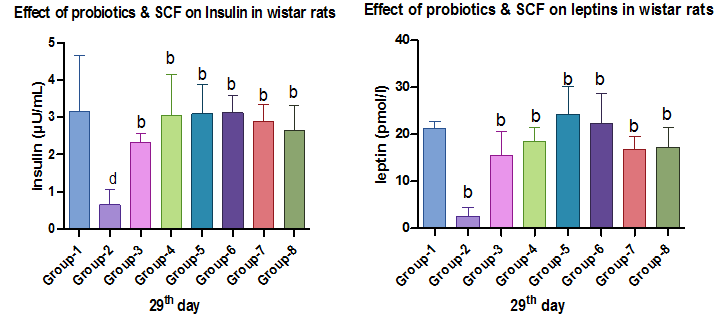

Diabetic rats showed dyslipidaemia with elevated TC, TG, LDL-C, VLDL-C, and reduced HDL-C. SCFAs and probiotics, especially in combination, significantly improved lipid profiles, renal profile, and liver markers, increasing the levels of insulin, serum leptin, a significant decrease in HbA1c, increasing the levels of hemoglobin, indicating a synergistic effect.

Fig. 2 and 3: Effect of probiotics and SCFAs on triglycerides and cholesterol

Fig. 4 and 5: Effect of Probiotics and SCFAs on LDL and HDL, Each value represents mean ±SD, with n= 6. Data were analyzed by using ANOVA followed by Dunnett's multiple comparison tests. Positive control was compared with other groups: a represents p<0.0001, b indicatesp<0.001, c indicates p<0.01, d indicates p<0.05

Fig. 6 and 7: Effect of probiotics and SCFAs on SGOT and SGPT

Fig. 8 and 9: Effect of Probiotics and SCFAs on creatinine and urea, each value represents mean ±SD, with n=6 data were analyzed by using ANOVA followed by Dunnett's multiple comparison tests. Positive control was compared with other groups: a represents p<0.0001, c indicates p<0.01, d indicates p<0.05

Fig. 10 and 11: Effect of probiotics and SCFAs on insulin and leptin

Fig. 12 and 13: Effect of probiotics and SCFAs on HbA1c and hemoglobin, Each value represents mean ±SD, with n=6. Data was analyzed using ANOVA, followed by Dunnett's multiple comparison tests. Positive control was compared with other groups: b indicates p<0.001, d indicates p<0.05

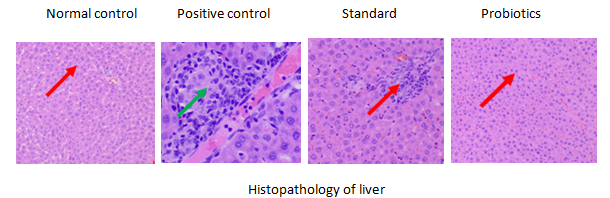

Fig. 14: Histopathology of the liver in groups 1, 2, 3, 4, Group 1: Normal histological architecture of the liver was observed (red arrow), Group 2: Marked hepatic inflammation was evident, characterized by hepatocellular swelling and significant leukocyte infiltration within the liver parenchyma (green arrow), Group 3 and 4: Restoration of normal liver architecture was observed, with hepatocytes retaining their normal morphology and arrangement. Notably, animals treated with a combination of SCFAs and probiotics showed the most preserved hepatic structure (red arrow)

Fig. 15: Histopathology of the liver in groups 5, 6, 7 and 8, Group 5,6: Red arrow indicates a well-preserved liver structure with normal hepatocyte arrangement, Group 7 and 8: The red arrow points to the liver area where normal cell structure and arrangement are best maintained

Fig. 16: Histopathology of pancreas in groups 1, 2, 3 and 4, Group 1: Normal histology of pancreas was observed (yellow arrow), Group 2: Degeneration of β-cells accompanied by mild inflammatory changes (red arrow), Group 3, and 4: Marked restoration of pancreatic architecture was observed in group 3 (green arrow) anddistinct β-cell hyperplasia and hypertrophy in group 4 (red arrow)

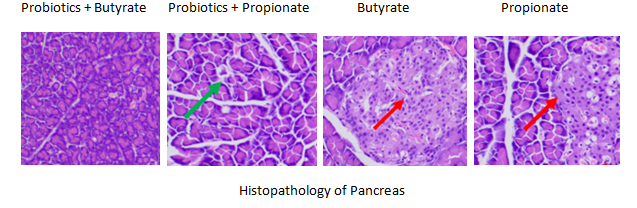

Fig. 17: Histopathology of pancreas in groups 5, 6, 7 and 8, Group, 5, 6, 7 and 8: Marked restoration of pancreatic architecture was observed in group 6 (green arrow) and distinct β-cell hyperplasia and hypertrophy in group 7 and 8 (red arrow)

Histopathology

Liver histology in the positive control group showed hepatocellular swelling and leukocyte infiltration (fig. 14, green arrow). In contrast, SCFAs-probiotic treatment preserved standard liver architecture with intact hepatocyte morphology (fig. 15, red arrow).

DISCUSSION

Diabetes-associated dyslipidemia is characterized by elevated TC, TG, LDL-C, VLDL-C, and reduced HDL-C factors contributing to cardiovascular risks. In this study, diabetic rats treated with SCFAs, and probiotics for 28 d showed significant improvements in serum lipid parameters. These included TC, TG, LDL-C, VLDL-C reductions, and elevated HDL-C. The combination therapy yielded the most pronounced effects, likely through synergistic actions on lipid metabolism via gut microbiota modulation and PPAR pathway activation [38]. Diabetic rats exhibited elevated liver enzymes (ALT, AST, ALP), indicating hepatic stress and dysfunction. Supplementation with SCFAs (400 mg/kg) and probiotics (10⁶ CFU) significantly reduced these levels, suggesting hepatoprotection and improved metabolic function. The observed benefits are consistent with previous studies showing that SCFAs and probiotics enhance insulin sensitivity, reduce inflammation, and support gut-liver axis homeostasis [39-42]. Diabetic nephropathy was confirmed by elevated BUN and serum creatinine, indicators of renal impairment. SCFA and probiotic treatment significantly reduced these markers, reflecting renoprotective effects. This aligns with previous findings that SCFAs, especially butyrate, reduce oxidative stress and inflammation and enhance renal homeostasis via gut-kidney axis modulation [43-45]. Over 28 d, all treatment groups exhibited significant reductions in BGL, with the butyrate-plus-probiotic group showing the most substantial glucose-lowering effect. Glibenclamide was most effective early on, though the final glucose levels remained slightly elevated. Probiotics also produced a sustained decrease in BGL, likely through enhanced GLP-1 secretion and improved microbiota composition [46]. Butyrate, especially when combined with probiotics, marked BGL improvement during the later treatment phases, consistent with its role in promoting insulin sensitivity and modulating inflammation [47].

Insulin levels were significantly lower in diabetic controls, indicating pancreatic dysfunction. Treatment groups showed markedly improved insulin concentration, suggesting improved secretion or sensitivity. Prior research supports this outcome, noting that SCFAs and probiotics stimulate pancreatic β-cells and reduce systemic inflammation [48]. Supplementation with SCFAs and probiotics also increased serum leptin levels, indicating improved energy regulation and metabolic balance. This study's findings align with prior research highlighting the interplay between insulin, leptin, and lipid metabolism in type 2 diabetes. Insulin deficiency disrupts lipid storage and reduces leptin secretion [49, 50], consistent with the reduced leptin levels observed in diabetic models [51]. The increased levels of leptin in SCFA-and probiotic-treated groups may result from improved insulin function and gut barrier integrity [52]. Leptin's role in enhancing insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance [53] supports these outcomes, though chronic hyperleptinemia could induce leptin resistance [54]. Thus, maintaining leptin balance is crucial. Overall, SCFAs and probiotics promise to improve metabolic markers by modulating gut microbiota and enhancing hormone regulation, though long-term studies are needed to confirm their clinical relevance.

This study found that SCFA and probiotic treatment significantly reduced HbA1c and improved hemoglobin levels in diabetic rats, indicating enhanced long-term glycemic control. These effects likely result from improved insulin sensitivity, gut microbiota modulation, and enhanced glucose metabolism. Combined therapy showed superior benefits over individual treatments or standard drugs. Further human studies are needed to confirm these therapeutic effects.

Histopathological analysis revealed severe liver and pancreatic damage in diabetic rats, including hepatocellular necrosis and beta-cell destruction, consistent with oxidative stress and inflammation induced by chronic hyperglycemia. Treatment with SCFAs and probiotics significantly preserved hepatic and pancreatic architecture, reduced inflammation, and enhanced beta-cell integrity. The combination therapy showed near-complete restoration of pancreatic tissue, likely through anti-inflammatory actions, HDAC inhibition, and gut microbiota modulation. These findings highlight the potential of SCFAs and probiotics to protect against diabetes-induced tissue damage and support metabolic homeostasis.

CONCLUSION

This study provides compelling evidence for the therapeutic potential of SCFAs and probiotics in managing Type 2 diabetes, particularly through modulation of leptin regulation. Combining SCFAs and probiotics significantly improved glycemic control, lipid metabolism, insulin sensitivity, and renal function. A key finding was the enhancement of leptin secretion and sensitivity, underscoring the role of gut microbiota in systemic metabolic regulation. The synergistic effects suggest that these interventions preserve pancreatic and hepatic integrity and restore hormonal balance critical for energy and glucose homeostasis. Maintaining leptin homeostasis is essential to prevent resistance and ensure sustained metabolic benefits. These results support the inclusion of SCFA and probiotic strategies as complementary therapies in diabetes management. Further clinical studies are essential to validate these preclinical findings and explore long-term efficacy and safety in human populations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors acknowledge GITAM School of Pharmacy and Sarojini Naidu Vanitha Pharmacy MahaVidyalaya for providing the facilities required to finish the study. Special thanks to BVRIT for organizing the international conference PRANATHI 2024-INPHE, allowing me to publish my research work.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Designing the study, Planning the research, carrying out the project, and writing the manuscript: P. Rajyaakshmi Devi and Koppala R. V. S Chaitanya, Statistical analysis: M. Vinyas; Biochemical evaluation and Manuscript drafting: Mote Srinath, and B. Maheshwari Reddy. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

There are no conflicts of interest to disclose in this research

REFERENCES

Rajyalakshmi Devi P, Vinyas M, Vinod Kumar N, Srinath M, Mote. Comparative anti-obesity activity of probiotics with short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) through GLP 1 and PYY activity in high-fat diet-induced obesity in rats. TexilaInt J Public Health. 2024;12(3):Art.007. doi: 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.12.03.

Devi PR, Srinath M, Venu T, Nelson VK, Vinyas M. Acute and sub-acute toxicological study of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) in rats. IJASE. 2025;11(4):4424-34. doi: 10.29294/IJASE.11.4.2025.4424-4434.

Ezenabor EH, Adeyemi AA, Adeyemi OS. Gut microbiota and metabolic syndrome: relationships and opportunities for new therapeutic strategies. Scientifica. 2024;2024:4222083. doi: 10.1155/2024/4222083, PMID 39041052.

Zhou Y. Gut microbiota derived SCFAs regulate leptin signaling and improve leptin resistance in obesity and type 2 diabetes models. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2023;20:23. doi: 10.1186/s12986-023-00694-2.

Huang X. Modulating gut microbiota and leptinsignaling pathways by butyrate improves metabolic parameters in high fat diet induced diabetic mice. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:918456. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.918456.

Zhao L. Butyrate supplementation improves insulin sensitivity and modulates inflammation in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized double blind placebo controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2022;45(8):1864-72. doi: 10.2337/dc21-1634.

Bailey CJ. Metformin: historical overview. Diabetologia. 2017;60(9):1566-76. doi: 10.1007/s00125-017-4318-z, PMID 28776081.

Ekblad LL, Rinne JO, Puukka P, Laine H, Ahtiluoto S, Sulkava R. Response to comment by Ayubi and Safiri. Insulin resistance predicts cognitive decline: an 11-y follow-up of a nationally representative adult population sample. Diabetes Care 2017;40:751-758. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(9):e136. doi: 10.2337/dci17-0023, PMID 28830969.

Den Besten G, Van Eunen K, Groen AK, Venema K, Reijngoud DJ, Bakker BM. The role of short chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet gut microbiota and host energy metabolism. J Lipid Res. 2013;54(9):2325-40. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R036012, PMID 23821742.

Canfora EE, Jocken JW, Blaak EE. Short chain fatty acids in control of body weight and insulin sensitivity. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015;11(10):577-91. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2015.128, PMID 26260141.

Kimura I, Inoue D, Hirano K, Tsujimoto G. The SCFA receptor GPR43 and energy metabolism. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2014;5:85. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2014.00085, PMID 24926285.

Heimann E. Butyrate increases leptin production in adipocytes. J Nutr Biochem. 2015;26(7):702-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2015.02.009.

Tolhurst G, Heffron H, Lam YS, Parker HE, Habib AM, Diakogiannaki E. Short-chain fatty acids stimulate glucagon like peptide-1 secretion via the G-protein–coupled receptor FFAR2. Diabetes. 2012;61(2):364-71. doi: 10.2337/db11-1019, PMID 22190648.

Gao Z, Yin J, Zhang J, Ward RE, Martin RJ, Lefevre M. Butyrate improves insulin sensitivity and increases energy expenditure in mice. Diabetes. 2009;58(7):1509-17. doi: 10.2337/db08-1637, PMID 19366864.

Louis P, Flint HJ. Formation of propionate and butyrate by the human colonic microbiota. Environ Microbiol. 2017;19(1):29-41. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13589, PMID 27928878.

Hamer HM, Jonkers D, Venema K, Vanhoutvin S, Troost FJ, Brummer RJ. Review article: the role of butyrate on colonic function. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27(2):104-19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03562.x, PMID 17973645.

Slavin JL. Dietary fiber and body weight. Nutrition. 2005;21(3):411-8. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2004.08.018, PMID 15797686.

Li Z, Yi CX, Katiraei S, Kooijman S, Zhou E, Chung CK. Butyrate reduces appetite and activates brown adipose tissue via the gut-brain neural circuit. Gut. 2018;67(7):1269-79. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314050, PMID 29101261.

O Callaghan A, Van Sinderen D. Bifidobacteria and their role as members of the human gut microbiota. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:925. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00925, PMID 27379055.

Riviere A, Selak M, Lantin D, Leroy F, De Vuyst L. Bifidobacteria and butyrate-producing colon bacteria: importance and strategies for their stimulation in the human gut. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:979. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00979, PMID 27446020.

Koh A, De Vadder F, Kovatcheva Datchary P, Backhed F. From dietary fiber to host physiology: short-chain fatty acids as key bacterial metabolites. Cell. 2016;165(6):1332-45. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.041, PMID 27259147.

Hirten RP, Grinspan A, Fu SC, Luo Y, Suarez Farinas M, Rowland J. Microbial engraftment and efficacy of fecal microbiota transplant for Clostridium difficile in patients with and without inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25(6):969-79. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izy398, PMID 30852592.

Smith PM, Howitt MR, Panikov N, Michaud M, Gallini CA, Bohlooly YM. The microbial metabolites short chain fatty acids regulate colonic treg cell homeostasis. Science. 2013;341(6145):569-73. doi: 10.1126/science.1241165, PMID 23828891.

Liu H, Wang J, He T, Becker S, Zhang G, Li D. Butyrate: a double edged sword for health? Adv Nutr. 2018;9(1):21-9. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmx009, PMID 29438462.

Patterson E, Ryan PM, Cryan JF, Dinan TG, Ross RP, Fitzgerald GF. Gut microbiota obesity and diabetes. Postgrad Med J. 2016;92(1087):286-300. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2015-133285, PMID 26912499.

Zhang C, Li S, Yang L, Huang P, Li W, Wang S. Structural modulation of gut microbiota in life-long calorie-restricted mice. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2163. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3163, PMID 23860099.

Fava F. The type and quantity of dietary fat and carbohydrate alter faecal microbiome and short chain fatty acid excretion in a metabolic ward study. Gut. 2013;62(12):1913-21. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303953.

Nishita M, Park SY, Nishio T, Kamizaki K, Wang Z, Tamada K. Ror2 signaling regulates golgi structure and transport through IFT20 for tumor invasiveness. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):1. doi: 10.1038/s41598-016-0028-x, PMID 28127051.

Machate DJ. The gut microbiota as a target for nutritional therapies. Nutrients. 2020;12(5):1127. doi: 10.3390/nu12051127.

Gerritsen J, Smidt H, Rijkers GT, De Vos WM. Intestinal microbiota in human health and disease: the impact of probiotics. Genes Nutr. 2011;6(3):209-40. doi: 10.1007/s12263-011-0229-7, PMID 21617937.

Lee GO, Paz Soldan VA, Riley Powell AR, Gomez A, Tarazona Meza C, Villaizan Paliza K. Food choice and dietary intake among people with tuberculosis in Peru: implications for improving practice. Curr Dev Nutr. 2020;4(2):nzaa001. doi: 10.1093/cdn/nzaa001, PMID 32025614.

Zeng H. Dietary fiber and gut microbiota interactions. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2019;59(2):186-96. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2017.1364811.

Louis P, Flint HJ. Diversity metabolism and microbial ecology of butyrate-producing bacteria from the human large intestine. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2009;294(1):1-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01514.x, PMID 19222573.

Qin J, Li R, Raes J, Arumugam M, Burgdorf KS, Manichanh C. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature. 2010;464(7285):59-65. doi: 10.1038/nature08821, PMID 20203603.

Lin HV, Frassetto A, Kowalik EJ, Nawrocki AR, Lu MM, Kosinski JR. Butyrate and propionate protect against diet-induced obesity and regulate gut hormones via free fatty acid receptor 3-independent mechanisms. PLOS One. 2012;7(4):e35240. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035240, PMID 22506074.

Haro C, Garcia Carpintero S, Alcala Diaz JF, Gomez Delgado F, Delgado Lista J, Perez Martinez P. The gut microbial community in metabolic syndrome patients is modified by diet. J Nutr Biochem. 2016;27:27-31. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2015.08.011, PMID 26376027.

Schwiertz A, Taras D, Schafer K, Beijer S, Bos NA, Donus C. Microbiota and SCFA in lean and overweight healthy subjects. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2010;18(1):190-5. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.167, PMID 19498350.

Chambers ES, Viardot A, Psichas A, Morrison DJ, Murphy KG, Zac Varghese SE. Effects of targeted delivery of propionate to the human colon on appetite regulation body weight maintenance and adiposity in overweight adults. Gut. 2015;64(11):1744-54. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307913, PMID 25500202.

De Vadder F, Kovatcheva Datchary P, Goncalves D, Vinera J, Zitoun C, Duchampt A. Microbiota generated metabolites promote metabolic benefits via gut brain neural circuits. Cell. 2014;156(1-2):84-96. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.016, PMID 24412651.

Meijer K. Butyrate modulates oxidative stress in adipocytes in a peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-γ–dependent manner. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(26):21191-9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.088385.

Wang W. Butyrate enhances the intestinal barrier by facilitating tight junction assembly via activating AMP-activated protein kinase in Caco-2 cell monolayers. J Nutr Biochem. 2012;23(4):388-96. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2011.01.007.

Lu Y. Sodium butyrate exerts anti-inflammatory effects on LPS-stimulated macrophages and dextran sulfate sodium induced colitis model. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2020;2020:8472639. doi: 10.1155/2020/8472639.

Canani RB, Costanzo MD, Leone L, Pedata M, Meli R, Calignano A. Potential beneficial effects of butyrate in intestinal and extraintestinal diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17(12):1519-28. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i12.1519, PMID 21472114.

Vinolo MA, Rodrigues HG, Nachbar RT, Curi R. Regulation of inflammation by short chain fatty acids. Nutrients. 2011;3(10):858-76. doi: 10.3390/nu3100858, PMID 22254083.

Ma X. Sodium butyrate modulates mucosal inflammation and intestinal barrier function in a mouse model of inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2012;47(5):463-72. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2012.658874.

Zhang L. Sodium butyrate inhibits inflammation and maintains epithelium barrier function in a TNBS-induced inflammatory bowel disease mice model. Int Immunopharmacol. 2016;36:70-7. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2016.04.006.

Ferreira Halder CV, Faria AV, Andrade SS. Action and function of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in health and disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;31(6):643-8. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2017.09.011.

Lopez Siles M, Duncan SH, Garcia Gil LJ, Martinez Medina M. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii: from microbiology to diagnostics and prognostics. ISME J. 2017;11(4):841-52. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2016.176, PMID 28045459.

Wang L. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii produces butyrate to maintain Th17/Treg balance and to ameliorate colorectal colitis by inhibiting histone deacetylase 1. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;91:107276. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.107276.

Martin R. The commensal bacterium Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is protective in a murine model of colitis. Gut. 2008;57(7):950-7. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.044834.

Chang G, Zhang K, Xu T, Jin D, Seyfert HM, Shen X. Feeding a high grain diet reduces the percentage of LPS clearance and enhances immune gene expression in goat liver. BMC Vet Res. 2015;11:67. doi: 10.1186/s12917-015-0376-y, PMID 25889631.

Rajilic Stojanovic M, De Vos WM. The first 1000 cultured species of the human gastrointestinal microbiota. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2014;38(5):996-1047. doi: 10.1111/1574-6976.12075, PMID 24861948.

Scott KP, Gratz SW, Sheridan PO, Flint HJ, Duncan SH. The influence of diet on the gut microbiota. Pharmacol Res. 2013;69(1):52-60. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2012.10.020, PMID 23147033.

Holscher HD. Dietary fiber and prebiotics and the gastrointestinal microbiota. Gut Microbes. 2017;8(2):172-84. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2017.1290756, PMID 28165863.