Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 5, 2025, 132-138Original Article

DEVELOPMENT OF A METHOD FOR QUALITY CONTROL OF PEPTIDE DRUGS WITHOUT OPENING THE PRIMARY PACKAGING

OLEG V. LEDENEV1,2*, GLEB V. PETROV2, ALEXANDER SKRIPNIKOV1, ANTON V. SYROESHKIN2

1Department of Biology, Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow-119234, Russia. 2Department of Pharmaceutical and Toxicological Chemistry, Peoples Friendship University of Russia (RUDN University), 6 Miklukho-Maklaya St, Moscow-117198, Russia

*Corresponding author: Oleg V. Ledenev; *Email: ya@olegledenev.ru

Received: 28 Mar 2025, Revised and Accepted: 17 Jun 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: The purpose of our study is to search for a new express method for quality control of peptides and polypeptides based on their authenticity.

Methods: Aqueous solutions of animal and plant-derived regulatory peptides, experimental compounds and finished therapeutics, finished dosage forms of animal tissue extracts (a mixture of peptides and polypeptides from tissues) and drugs with active pharmaceutical ingredient in which solutions of anti-bodies to interferon γ were applied on a carrier in the fluidized bed chamber have been studied by methods such as: dynamic light scattering (DLS) for determining the size distribution of density heterogeneities, method of two-dimensional dynamic light scattering (2D-DLS) and method for determining radiothermal emission using a broadband radiometer to specific identification of peptides and polypeptides drugs without opening the packaging due to the individual data set of each biomolecule. Method of solid phase peptide synthesis based on the FMOC technology

Results: The data obtained indicate that biologically active peptides and polypeptides can induce heterogeneous densities within the submicron (100–1000 nm) and micron (5,000–6,000 nm) ranges. These specific induction patterns were used as individual characteristics of each peptide or active pharmaceutical agent. These were detected using the two-dimensional dynamic light scattering (2D-DLS) method. For example, peptides derived from the same plant (StSys1) and (StPep1) can be easily distinguished at nanomolar concentrations. This approach demonstrates the creation of a unique “fingerprint” for each peptide preparation.

In addition, it has been found that solutions containing peptides, which are biologically active nanoparticles with complex shapes, not only emit within the millimeter wavelength range but can also mimic their presence within cells by activating giant clusters.

Conclusion: The interaction of peptides and polypeptides with aqueous solutions leads to remote anomalous induction of water clusters. The spectrum of sizes of these giant heterophase water clusters, the kinetics of their flickering, and millimeter-wavelength radio emission open up the possibility of express control of peptide-based drugs by their "authenticity" characteristic without opening the packaging.

Keywords: Peptides, Aqueous solutions, Quality control of peptide agents, DLS, Diffuse reflection, Radiothermal emission, Peptides drugs, CPP

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i5.54386 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

The pool of biologically active animal and plant peptides is formed as a result of the catabolism of endogenous proteins [1], hydrolysis of exogenous polypeptides (from food) [2], de novo synthesis [3], and absorption of exogenous peptides [4].

There is a theory that defines the pool of peptides of diverse origin as the lower level of metabolism regulation [5]. The simplest example is the dipeptide carnosine, a classic antioxidant and participant in the buffer system for pH stabilization with pK=7.0. Biologically active peptides can play the role of participants in futile cycles in nitrogen metabolism, which allow regulating flows of nitrogen-containing heteroatomic compounds along various pathways of synthesis and disintegration, kinetically bypassing the thermodynamic restrictions of a simple reversal of the reaction sequence [6].

There are also specific receptors for bioactive peptides with subsequent generation of secondary messengers both in animals and plants, which makes the mechanism of action of these peptides similar to the response to hormones [7]. This is especially characteristic of neuropeptides, including enkephalins and endorphins [8].

Bioactive peptides can be either linear or cyclic oligopeptides [9], as well as glycosylated derivatives [10]. Peptides may include β-amino acids and D-enantiomers [11, 12].

Exogenous sources of bioactive peptides can be tissues of animals [13], plants [14], insects [15], or bacterial biomass [16]. For the purposes of pharmaceutical chemistry, it is very interesting that bioactive peptides have demonstrated clinically proven effects as nootropic agents (including those for post-stroke rehabilitation) [17], anti-infective activity [18], and anti-cancer activity [19].

The objects of this study are bioactive peptides and polypeptides of animal and plant origins, including finished dosage forms, which are characterized by the manifestation of biological activity at low concentrations 1 nM [20]. We demonstrated the application of a newly developed express quality control method for animal and plant peptide aquatic preparations based on diffuse reflection. This method, which we recently developed [21], was used to monitor isotope content in the anti-cancer adjuvant-deuterium-depleted water. We also proposed an explanation for the mechanism of action of peptides and polypeptides in the nM concentration range using a quality control method for biologically active nanoparticles by their intrinsic radiothermal emission.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Dynamic light scattering method

The size distribution of density heterogeneities and control of their dispersity were carried out using a Zetasizer Nano ZSP dynamic light scattering spectrometer (DLS) (MALVERN Instruments, UK). Applications: measurement of diluted samples, nanoparticle size distribution from 0.1 nm to 10 µm using patented NIBS (Non-Invasive Back Scattering) technology [22, 23]. The measurement principle is based on photon correlation spectroscopy, which is based on the analysis of the Brownian motion of particles of the dispersed phase in a dispersion medium, which leads to fluctuations in the local concentration of particles, local heterogeneities of the refractive index, and fluctuations in the intensity of scattered light. The characteristic relaxation time of intensity fluctuations is inversely proportional to the diffusion coefficient. Particle size is calculated using the Stokes-Einstein equation:

where: D is the diffusion coefficient, kB is the Boltzmann constant, T is the absolute temperature, η is the viscosity of the liquid, r is the radius of the particle.

Each solution of nanoparticles was controlled for monodispersity using the DLS method and the absence of impurities in the band of more than 190 nm. The buffer solutions and high-resistivity water (Millipore) were also controlled for impurities. Measurement conditions: the time of one measurement is 15 sec with 11 repetitions and 5 measurements for reproducibility. Every time, we controlled the refractive index (refract metrically) and the temperature of the solution. The refractive index of oligopeptide nanoparticles was taken to be 1.45. The solutions were studied in high-resistance water and in TNC buffer (0.01 M Tris (hydroxymethyl) aminomethane; 0.14 M NaCl; 0.01 M CaCl2; pH 7.2–7.4).

Measurement of the radiothermal emission

The density of the radiothermal emission flux in the microwave band of wavelengths was determined using a TES-92 apparatus (TES Electrical Electronic Corp., Taipei, Taiwan) with the device tuned for anisotropic measurement along the Z axis [21]. The measurement results were recorded – the maximum average value of the flux density at a given point in time with stepwise averaging every 300 ms.

The powders or solutions were heated using a solid-state thermostat with Peltier elements (Termo 24-15 Biokom, Moscow, Russia) under the control over the temperature of the sample through a remote laser infrared thermometer (Bentech GM320, Shenzen Jumaoyuan Science and Technology Co., Ltd., Schenzen, China).

The samples were activated by light using LEDs of a new generation, which provide a power density of up to 50 mW/cm2 in the region of 407 nm at a spectral linewidth of up to 2–4 nm (including model AA3528LVBS/D, type C503B-BCN-CV0Z0461, manufacturer Cree LED, USA) [24].

All measurements were carried out on the unit strictly in the same geometry, located in a room, where the second TES-92 device controlled the distribution of the microwave background radiation with a height, width, and length pitch of 50 cm. The background radiation in the experimental room did not exceed 1 μW/m2 at all monitoring points.

Aqueous solutions were applied in drops of 100 µl to the bottom in the center of sterile 4 cm Petri dishes axially along the Z axis, 10 mm from the measuring head of the device. The powders were poured in doses of 30 g into 10 cm sterile Petri dishes with uniform shrinkage. All measurements were taken at least 7 times. The standard deviation is shown in the graphs of the Results section. TES-92, as an electric field meter, was calibrated with a relative error of 1 dB and has a low temperature error (0.2 dB in the range from 0 °C to 50 °C).

Diffuse reflection method (2D-DLS)

The registration of dynamic light scattering in two-dimensional space (2D-DLS) was carried out within the framework of the optical scheme for recording the kinetics of changes in the two-dimensional reflection pattern, as described earlier [25]. In addition to laser sources, new-generation LEDs were used to probe a section of the solution at a given depth. The LEDs provide a power density of up to 50 mW/cm2 in the 360-410 nm region with a spectral line width of up to 2-4 nm (including model AA3528LVBS/D, type C503B-BCN-CV0Z0461, manufacturer – Cree LED). The light signal reflected from the object was recorded on a high-resolution CCD matrix (16 Mp) and processed as a matrix of discrete elements with a certain signal intensity. The obtained light scattering patterns were processed using ten topological descriptors. Each descriptor is a topological convolution of the scattering matrix obtained by element-wise subtraction of the background. Therefore, the descriptor reflects not only spatial heterogeneities on the surface or color, but also the variability of light reflection. A two-dimensional light scattering pattern is a matrix of discrete elements with a certain signal intensity. The Vidan® and Atrium® software developed at our university was used to process the data.

Peptide, polypeptide and oligomeric protein drugs

Oligopeptide solutions

Biologically active peptide that induces delta sleep phase – DSIP (CAS No.: 62568-57-4), MEHFPGP – was received from the Russian Peptide company in the form of a 1 μM solution of the active pharmaceutical ingredient, excipients: purified water, sodium chloride, methylparaben (preservative).

Semax, a therapeutic (reg. No.: LP-002553 dated 30/12/2011), 1 μM solution, amino acid sequence of the active substance: WAGGDASGE, excipients: methyl parahydroxybenzoate (preservative), purified water.

Peptide KH9, an internalizable peptide cell penetrating peptide (CPP) with the amino acid sequence KHKHKHKHKHKHKHKHKHKHKLFKKILKYL (29 amino acids (5 hydrophobic and 24 hydrophilic ones)). The peptide was obtained by solid-phase synthesis based on the FMOC technology. After purification of the peptide by HPLC and lyophilization, the level of purity and identity of the peptide drug was confirmed to be 95% by HPLC and mass spectrometry – the calculated monoisotopic molecular ion with a mass of 3,808.33 [26].

Peptide StSys1 – defense signaling peptide of potato Solanum tuberosum (systemin)–with the amino acid sequence AVHSTPPSKRDPPKMQTD (18 amino acids (7 hydrophobic and 11 hydrophilic ones)). The peptide was obtained by solid-phase synthesis based on the FMOC technology, purified by HPLC and verified using mass spectrometry. The calculated mass for the two isotopes is 1,992.221 amu, and the calculated monoisotopic molecular ion has a mass of 1,990.979 [27].

Peptide StPep1 – plant defense elicitor peptide of potato Solanum tuberosum, amino acid sequence: ATERRGRPPSRPKVGSGPPPQNN (23 amino acids (11 hydrophobic and 12 hydrophilic ones)). The peptide was obtained by solid-phase synthesis based on the FMOC technology. After purification of the peptide by HPLC and lyophilization, the level of purity and identity of the peptide drug was confirmed to be 95% by HPLC and mass spectrometry, the calculated monoisotopic molecular weight of the peptide with one proton–2,455.29, with two protons–1,228.15 [27].

Therapeutics–mixtures of peptides and polypeptides of animal origin

Cortexin (reg. No.: LP-(000620)-(RG-RU) dated 9/3/2022) is a lyophilisate, where the active substance is polypeptides of the cerebral cortex of cattle, and the excipient is glycine (which acts as a stabilizer). Protein concentration: 1 mg/ml.

Retinalamin (reg. No.: LP-(000519)-(RG-RU) dated 21/1/2022) lyophilisate, active substance: polypeptides of the retina of cattle, excipient: glycine. Protein concentration: 1 mg/ml.

Renobrain SM (reg. No.: No.: LP-008298 dated 27/6/2022) lyophilisate, active substance: complex of water-soluble polypeptide fractions obtained from the cerebral cortex of cattle, excipient: glycine. Protein concentration: 1 mg/ml.

Cerebrolysin (reg. No.: P N013827/01 dated 8/7/2007) solution for injection, active substance: Cerebrolysin concentrate (a complex of peptides obtained from the pig brain), excipients: sodium hydroxide, water for injection. Protein concentration: 1 mg/ml.

Medicinal substances made using gradual technology from antibodies to interferon (General Monograph of the State Pharmacopoeia of the Russian Federation No. OFS.1.7.0001)

Antibodies to interferon γ (AINFγ) (as an active pharmaceutical ingredient of the registered drug No.: LP-№(000023)-(RG-RU), manufactured by: OOO NPF MATERIA MEDICA HOLDING) were obtained from the manufacturer in the form of a powdered substance (on a carrier) saturated with hydroalcoholic AINFγ in the fluidized bed aerosol chamber, we described the characteristics of the substance earlier [28]. Placebos of antibodies to INFγ were also specially made in the aerosol chamber, AINFγ solutions were replaced in them by phosphate-buffered saline before being placed in the fluidized bed chamber [29]. The carrier was also investigated – intact powder of lactose monohydrate used for the manufacture of a pharmaceutical substance.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Inhomogeneous densities caused by oligopeptides or polypeptides in aqueous solutions

Earlier, we showed that D-stabilized pH-dependent giant (over 1 μm) density heterogeneities can be induced in aqueous solutions [30]. This phenomenon can be a source of errors in determining the true sizes of peptides using the DLS method in solutions with geochemically common isotopic composition (D/H ratio from 140 to 150 ppm) [31]. Many studies have been dedicated to the formation of long-lived nanobubble associates by gases dissolved in aqueous solutions, forming so-called bubstons [32, 33]. Indeed, dynamic light scattering of aqueous solutions of biologically active peptides clearly shows that the size spectrum of density heterogeneities in the solution is different at various concentrations of peptides (table 1). Density heterogeneities that can be detected at peptide concentrations from 10 nM to 1 μM are close in size to the hydrodynamic radius of the peptide. In the example given in table 1, bubstons, which the peptide can induce, are always detected in the concentration range from 1 nM to 1 μM or can be sorbed at the phase interface. Giant heterophase clusters appear at a peptide concentration below 1 μM. Such a particular redistribution of density heterogeneities specifically depends on the type of peptide drug and its concentration.

Table 1: Distributions of density heterogeneities by size in StSys1 peptide solutions according to DLS data

| Concentration | Peptides1 (0.1-10 nm) | Bubstons2 (10 nm – 1,000 nm) | GHC3 (over 1,000 nm) |

| 1 μM | - | + | - |

| 0.1 μM | + | + | + |

| 0.01 μM | + | + | + |

| 1 nM | - | + | + |

1Hydrodynamic radius, 2Bubstons are nanobubbles of gases dissolved in water that combine into micron-sized particles (clusters), 3GHC (Giant Heterophase Clusters) density heterogeneities with sizes up to 100 μ.

Specificity of size spectra of density heterogeneities induced by different peptide drugs

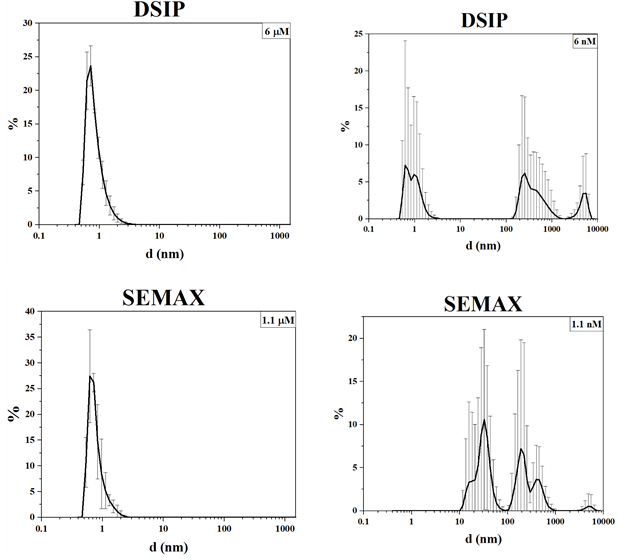

Taking into account the features of the redistribution of density heterogeneities of the StSys1 peptide, we studied the size spectra of water clusters in finished dosage forms of oligopeptides diluted to nM and μM concentrations. Concentrated oligopeptide drugs have similar size distribution patterns: the signal from peptide nanoparticles is dominant. With a 1,000-fold dilution, a specific spectrum is formed with the induction of submicron and micron clusters (fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Volume distribution of density heterogeneities of oligopeptide drugs

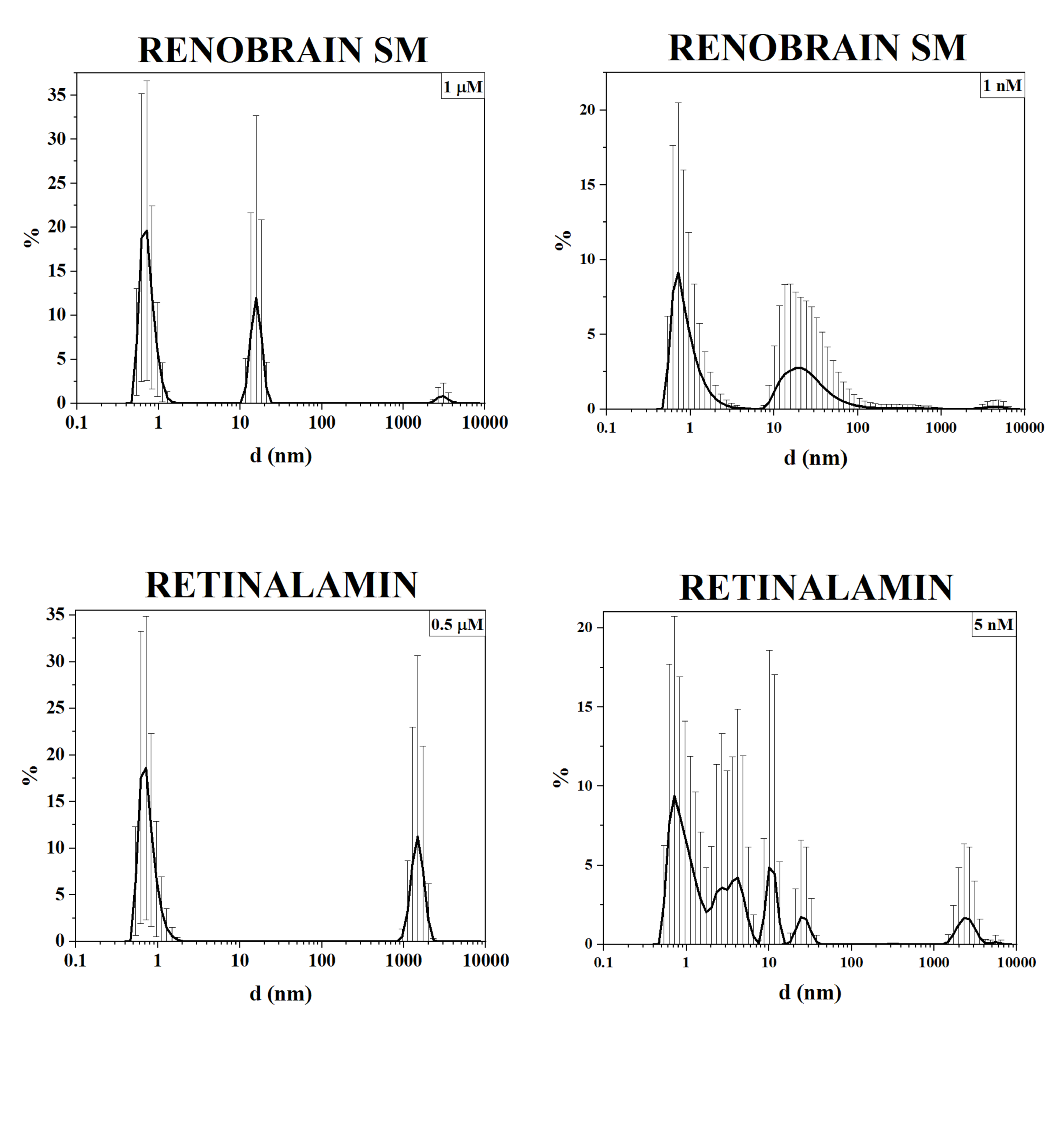

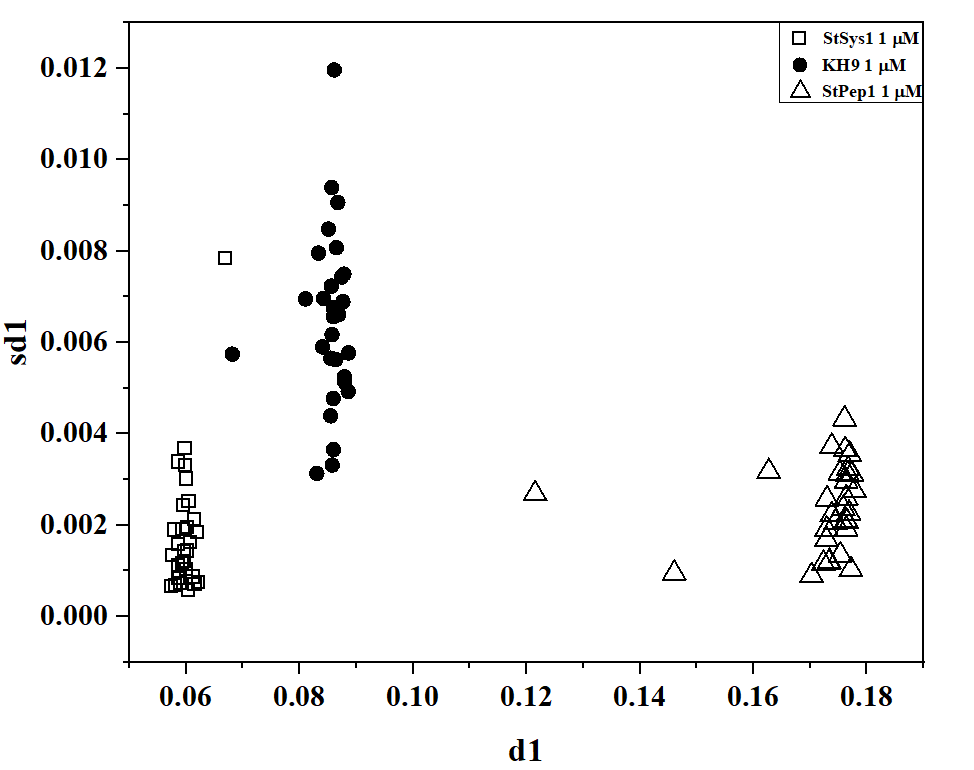

The induction of giant heterophase clusters in multicomponent polypeptide drugs is much less pronounced (fig. 2). The particle size distribution can be explained in different ways, in particular, by the formation and disintegration of protein associates.

Fig. 2: Volume distribution of density heterogeneities of multicomponent polypeptide and peptide drugs

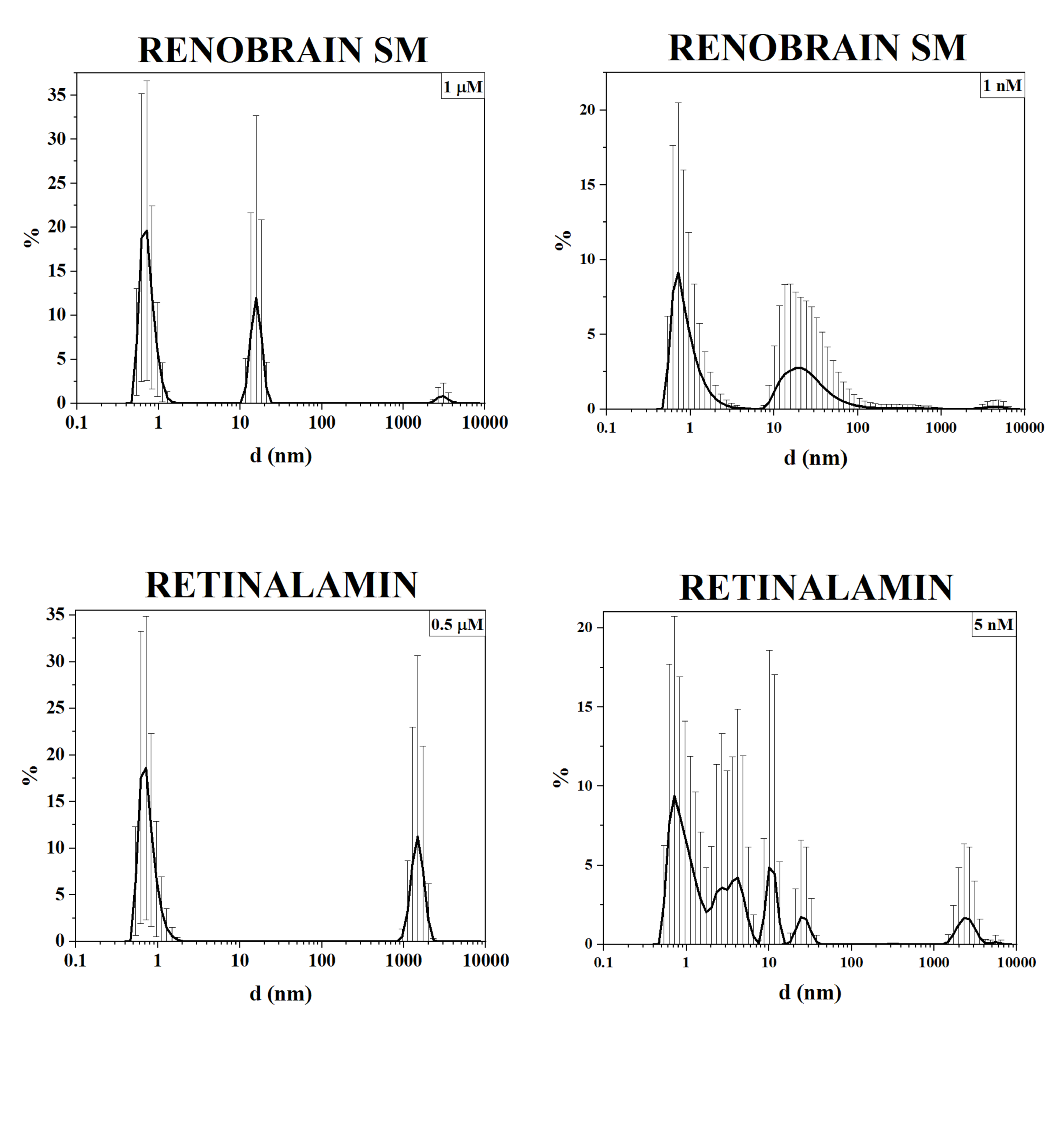

Possibility of specific determination of the oligopeptide type in aqueous solution without opening the packaging

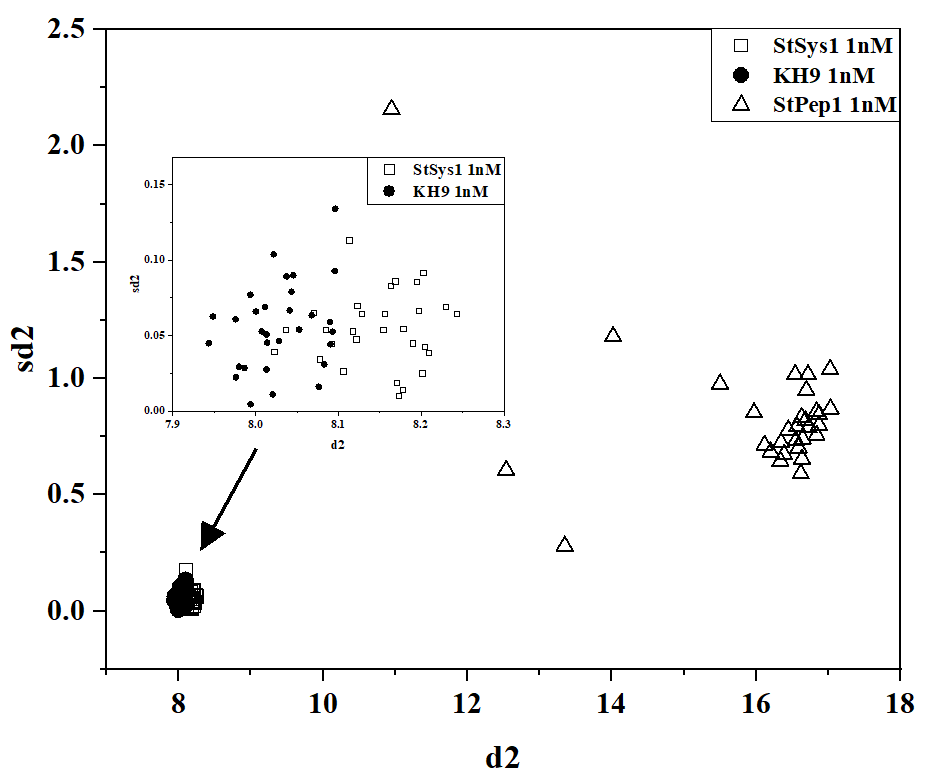

The kinetics of formation/disintegration of density heterogeneities formed by peptides also turned out to be specific. Fig. 3 shows the binary diagram data for two topological descriptors obtained through the 2D-DLS method in the setup of diffuse scattering kinetics. Qualitative identification of peptide types can be achieved at concentrations of 1 μM and 1 nM.

Since the dynamics of light scattering is recorded and the data are processed using a topological model, strict requirements for standard optics of absorption spectroscopy or conventional light scattering are not applied in this method. The shape of the vial does not affect the result since the flickering speed of giant clusters is recorded [31, 34]. This allows the 2D-DLS method to be applied to any transparent vials. If the design of the primary packaging (color, turbidity, stickers) does not allow probing the contents with a light beam, another approach can be used. This approach is based on the radiothermal emission by biologically active nanoparticles [35], that is, all the drugs investigated in this study.

Possibility of specific control of the authenticity of the type of peptide and polypeptide drugs in opaque primary packaging.

As shown [21, 35], biologically active nanoparticles can spontaneously emit in the millimeter band, and the amplification of this emission can be achieved both by heating the drugs and by irradiating them in the visible band. Indeed, all the drugs we studied are capable of radiothermal emission (table 2), and the flux density and the stimulation coefficient of the radio emission flux density form together a pair of numbers that unambiguously characterize the type of drug.

|

|

| (a) | (b) |

Fig. 3: Pairwise diagram of d1-sd1 descriptors for 1 μM solution (a) and d2-sd2 descriptors for 1 nM solution (b) of StPep1, StSys1, and KH9 peptides

Table 2: Radiothermal emission coefficient of peptide drugs without opening the primary packaging. The background did not exceed 1 µW/m2

| Name | 27 ˚CF (μW/m2) | Kt = (34 ˚CF/27 ˚CF) | |

| oligopeptides | DSIP | 34 ±2 | 1.30 |

| Semax | 17 ±1 | 1.80 | |

| medicinal substance based on antibodies to interferon | AINFγ* | 26 ±2 | 1.55 |

| Placebo* | 2 ±0.5 | 1.1 | |

| Intact lactose* | |||

| mixtures of peptides and polypeptides | Cerebrolysin | 17 ±2 | 1.27 |

| Renobrain SM | 30 ±3 | 1.11 | |

| Retinalamin | 52 ±5 | 0.80 | |

| Cortexin | 34 ±3 | 0.90 |

#-solution received from the manufacturer without opening the primary packaging. *-5% solution of powdered substance, 7 ml in a 4 cm Petri dish

If necessary, the reverse problem can be solved: determine 27 ˚CF and Kt to confirm the authenticity of the drug. The feature of this setup is that it is technically carried out without opening the primary packaging, since the radio emission from these objects largely overcomes glass or plastic with a thickness of less than 1 mm.

Likely mechanism of anomalous interaction of peptides with water clusters

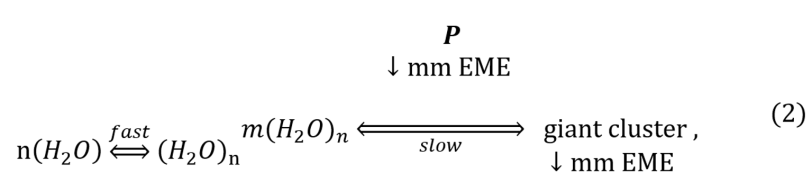

We assumed that the ability of peptides to induce water clusters (as seeds of a kind of water colloids) was associated with their ability to spontaneously emit radio waves. Indeed, spontaneous emission from peptide solutions, exceeding the thermal background, can be considered as an analogue of plasma nanoformations [36]. Moreover, the radio emission of these nanoantennas will act as a known synchronizer of van der Waals interactions [21] of induced dipoles on colloidal particles (oligopeptides, polypeptides, water clusters). In the presence of such a radio emitter, it is possible to explain the long-range effect – the induction of an ordered chiral water cluster with dimensions greater than 1 μm by a nano-object [34]. This model can be described by the following kinetic equation:

It is well known that water molecules spontaneously form short-lived (relaxation time less than 1 ns) subnanometer clusters [37]. The peptide (P in the diagram) enhances the ordering of nanoclusters into giant heterophase clusters emitting the same spectrum as the original peptide due to plasma-like generation of millimeter emission (mm EME).

A recent review of the literature on nanoparticles [38] lends support to our theory that peptide drugs, as irregularly shaped nanoparticles, are capable of emitting radiation in the millimetre range. The review also provides a graphical model of equation 2. This model suggests that water D-stabilized giant clusters will act as a kind of amplifiers of emission from a peptide or polypeptide. Indeed, with a thousand-fold dilution, the flux density (linearly dependent on the concentration of emitters – nanoparticles in non-aqueous media [21]) drops by 2-3 times, and it increases significantly for peptides of plant origin (table 3). This phenomenon explains well why it is possible to use such low therapeutic doses for bioactive peptides (in phytopathology as well [27]). If the calculated concentrations in the pharmacokinetics of peptides in blood plasma reach at least 1 nM, the dissociation constant of the potential receptor must be 100 pM. This affinity to oligopeptides cannot be explained since it suggests quasi-irreversible binding.

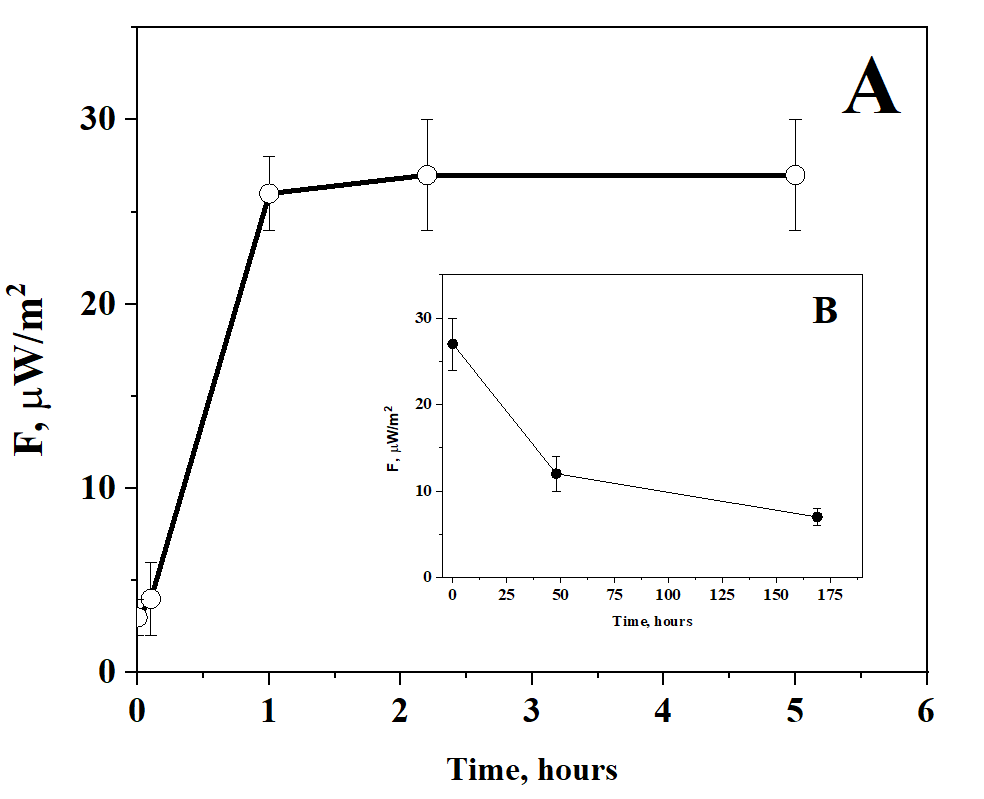

Taking into account the radio amplification of the signal from peptides on water clusters, a kind of mimicry is possible, when the effect on the receptor is dispersion-imitated in terms of the organization of flickering dipoles and conformational transformations [39]. We tested this possible remote mechanism on the simplest setup. 7 ml of 5% AINFγ solution was placed in a 4 cm Petri dish. A Petri dish with 7 ml of a 5% placebo solution (i.e., one that contained no active pharmaceutical ingredient) was placed on top. With one-hour kinetics, the placebo solution acquired the properties of emitting in the mm-band (fig. 4, A). If the activator (AINFγ solution) is removed, the activated placebo solution relaxes to background values of radio emission with one-day kinetics (fig. 4, B). It is interesting that, in this case, the signal transmission is possible only to the placebo that underwent the sample preparation stage in the fluidized bed chamber, like the active pharmaceutical ingredient. Such slow remote activation kinetics based on the model according to diagram 1 could be applied to explain the gradual technology (General Monograph of the State Pharmacopoeia of the Russian Federation No. OFS.1.7.0001) for the preparation of a new class of medicinal substances [40].

Fig. 4. Kinetics of remote activation of 5% placebo solution by 5% AINFγ solution (A) followed by relaxation after removal of the activator (B)

Table 3: Change in the flux density of radiothermal emission of aqueous solutions of peptide drugs upon dilution. Aliquot – 100 µl

| Name | 33 ˚CF (μW/m2) | ||

| Stock solution | 1,000-fold diluted solution | ||

Oligopeptides: of animal And plant origin |

DSIP | 37 ±2 | 19 ±2 (52%**) |

| StPep1* | 8 ±1 | 15 ±1 (187%) | |

| mixtures of peptides and polypeptides | RENOBRAIN SM | 37 ±2 | 14 ±1 (38%) |

*Initial concentration – 1 μM, **As a percentage of the concentrated solution

CONCLUSION

Aqueous solutions of peptides and polypeptides induce density heterogeneities in the submicron and micron bands, which can characterize the type of bioactive pharmaceutical and experimental peptide ingredient based on the type of size distribution spectra. The kinetics of formation/disintegration of density heterogeneities allows the identification of peptides without opening the primary packaging. Solutions of peptides, as biologically active nanoparticles of complex shapes, not only emit in the mm wavelength band themselves, but can mimic their presence due to the specific activation of giant clusters. The interaction of peptides and polypeptides with aqueous solutions leads to remote anomalous induction of water clusters. The spectrum of sizes of these giant heterophase water clusters, the kinetics of their flickering, and millimeter-wavelength radio emission open up the possibility of express control of peptide-based drugs by their "authenticity" characteristic without opening the packaging.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This paper has been supported by the RUDN University Strategic Academic Leadership program.

FUNDING

This publication has been supported by the RUDN University Scientific Projects Grant System, project № 033323-2-000.

ABBREVIATIONS

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

StPep1: Plant defense elicitor peptide of potato Solanum tuberosum, StSys1: Defense signaling peptide of potato Solanum tuberosum (systemin), KH9: Internalizable peptide (CPP), DSIP: Delta sleep-inducing peptide, AINFγ: Antibodies to interferon γ, GHC: Giant heterophase clusters density heterogeneities with sizes up to 100 μ, INFγ: Interferon γ, DLS: Dynamic light scattering, 2D-DLS: Dynamic light scattering in two-dimensional space, FMOC: Fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl protecting group, HPLC: High performance liquid chromatography, mm EME: Millimeter emission

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization, O. V. L., G. V. P., A. Y. S. and A. V. S.; methodology, A. V. S., O. V. L., G. V. P. and A. Y. S.; investigation, O. V. L.; validation, O. V. L. and A. V. S.; data curation, A. V. S., A. Y. S.; formal analysis, O. V. L.; writing—original draft preparation, O. V. L.; writing—review and editing, O. V. L., A. V. S., A. Y. S., G. V. P. All the authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

Serebrenik YV, Mani D, Maujean T, Burslem GM, Shalem O. Pooled endogenous protein tagging and recruitment for systematic profiling of protein function. Cell Genomics. 2024;4(10):100651. doi: 10.1016/j.xgen.2024.100651, PMID 39255790.

Toldra F, Reig M, Aristoy MC, Mora L. Generation of bioactive peptides during food processing. Food Chem. 2018 Nov 30;267:395-404. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.06.119, PMID 29934183.

Merz ML, Habeshian S, Li B, David JG, Nielsen AL, Ji X. De novo development of small cyclic peptides that are orally bioavailable. Nat Chem Biol. 2024;20(5):624-33. doi: 10.1038/s41589-023-01496-y, PMID 38155304.

Yarandi SS, Hebbar G, Sauer CG, Cole CR, Ziegler TR. Diverse roles of leptin in the gastrointestinal tract: modulation of motility absorption growth and inflammation. Nutrition. 2011;27(3):269-75. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2010.07.004, PMID 20947298.

Karelin AA, Blishchenko EY, Ivanov VT. A novel system of peptidergic regulation. FEBS Lett. 1998;428(1-2):7-12. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(98)00486-4, PMID 9645464.

Boldyrev AA, Aldini G, Derave W. Physiology and pathophysiology of carnosine. Physiol Rev. 2013;93(4):1803-45. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00039.2012, PMID 24137022.

Smith NK, Hackett TA, Galli A, Flynn CR. GLP-1: molecular mechanisms and outcomes of a complex signaling system. Neurochem Int. 2019 Sep;128:94-105. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2019.04.010, PMID 31002893.

Kamm K. CGRP: from neuropeptide to the therapeutic target (background and pathophysiology). Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr. 2024;92(7-8):267-76. doi: 10.1055/a-2331-0783, PMID 39025056.

Li T, Li T, Wang Z, Jin Y. Cyclopeptide-based anti-liver cancer agents: a mini-review. Protein Pept Lett. 2023;30(3):201-13. doi: 10.2174/0929866530666230217160717, PMID 36799423.

Angata K, Wagatsuma T, Togayachi A, Sato T, Sogabe M, Tajiri K. O-glycosylated HBsAg peptide can induce specific antibody neutralizing HBV infection. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj. 2022;1866(1):130020. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2021.130020, PMID 34582939.

Kiss L, Mandity IM, Fulop F. Highly functionalized cyclic β-amino acid moieties as promising scaffolds in peptide research and drug design. Amino Acids. 2017;49(9):1441-55. doi: 10.1007/s00726-017-2439-9, PMID 28634827.

Lander AJ, Jin Y, Luk LY. D-peptide and D-protein technology: recent advances, challenges and opportunities. ChemBioChem. 2023;24(4):e202200537. doi: 10.1002/cbic.202200537, PMID 36278392.

Gomazkov OA. Cortexin. Molecular mechanisms and targets of neuroprotective activity. Zh Nevrol Psikhiatr Im SS Korsakova. 2015;115(8):99-104. doi: 10.17116/jnevro20151158199-104, PMID 26356623.

Kaufmann C, Sauter M. Sulfated plant peptide hormones. J Exp Bot. 2019;70(16):4267-77. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erz292, PMID 31231771.

Yi HY, Chowdhury M, Huang YD, Yu XQ. Insect antimicrobial peptides and their applications. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98(13):5807-22. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5792-6, PMID 24811407.

Suchi SA, Nam KB, Kim YK, Tarek H, Yoo JC. A novel antimicrobial peptide YS12 isolated from Bacillus velezensis CBSYS12 exerts anti-biofilm properties against drug-resistant bacteria. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng. 2023;46(6):813-28. doi: 10.1007/s00449-023-02864-7, PMID 36997801.

Ziganshina LE, Abakumova T, Nurkhametova D, Ivanchenko K. Cerebrolysin for acute ischaemic stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023;10(10):CD007026. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007026.pub7, PMID 37818733.

Boparai JK, Sharma PK. Mini review on antimicrobial peptides sources, mechanism and recent applications. Protein Pept Lett. 2020;27(1):4-16. doi: 10.2174/0929866526666190822165812, PMID 31438824.

Qiao Y, Xu B. Peptide assemblies for cancer therapy. ChemMedChem. 2023;18(17):e202300258. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.202300258, PMID 37380607.

Ito Y, Nakanomyo I, Motose H, Iwamoto K, Sawa S, Dohmae N. Dodeca CLE peptides as suppressors of plant stem cell differentiation. Science. 2006;313(5788):842-5. doi: 10.1126/science.1128436, PMID 16902140.

Syroeshkin AV, Petrov GV, Taranov VV, Pleteneva TV, Koldina AM, Gaydashev IA. Radiothermal emission of nanoparticles with a complex shape as a tool for the quality control of pharmaceuticals containing biologically active nanoparticles. Pharmaceutics. 2023;15(3):966. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics15030966, PMID 36986826.

Dangi P, Op J. Green synthesis, characterization and in vitro antimicrobial efficacy of silver nanoparticles synthesized from Tectona Grandis wood flour. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2019;12(1):257. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2019.v12i1.28849.

Gokul M, GU, Esakki A. Green synthesis and characterization of isolated flavonoid mediated copper nanoparticles by using Thespesia populnea leaf extract and its evaluation of anti-oxidant and anti-cancer activity. Int J Chem Res. 2022;6(1):15-32. doi: 10.22159/ijcr.2022v6i1.197.

Petrov GV, Gaidashev IA, Syroeshkin AV. Physical and chemical characteristics of aqueous colloidal infusions of medicinal plants containing humic acids. Int J Appl Pharm. 2024;16(1):76-82. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2024v16i1.49339.

Koldina AM, Uspenskaya EV, Borodin AA, Pleteneva TV, Syroeshkin AV. Light scattering in research and quality control of deuterium-depleted water for pharmaceutical application. Int J Appl Pharm. 2019;11(5):271-8. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2019v11i5.34672.

Thagun C, Motoda Y, Kigawa T, Kodama Y, Numata K. Simultaneous introduction of multiple biomacromolecules into plant cells using a cell penetrating peptide nanocarrier. Nanoscale. 2020;12(36):18844-56. doi: 10.1039/D0NR04718J, PMID 32896843.

Skripnikov A. Bioassays for identifying and characterizing plant regulatory peptides. Biomolecules. 2023;13(12):1795. doi: 10.3390/biom13121795, PMID 38136666.

Uspenskaya EV, Pleteneva TV, Syroeshkin AV, Tarabrina IV. Preparation, characterization and studies of physicochemical and biological properties of drugs coating lactose in fluidized beds. Int J Appl Pharm. 2020;12(5):272-8. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2020v12i5.38281.

Morozova MA, Koldina AM, Maksimova TV, Marukhlenko AV, Zlatsky IA, Syroeshkin AV. Slow quasikinetic changes in water lactose complexes during storage. Int J Appl Pharm. 2021;13(1):227-32. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2021v13i1.39837.

Goncharuk VV, Lapshin VB, Burdeinaya TN, Pleteneva TV, Chernopyatko AS, Atamanenko ID. Physicochemical properties and biological activity of the water depleted of heavy isotopes. J Water Chem Technol. 2011;33(1):8-13. doi: 10.3103/S1063455X11010024.

Goncharuk VV, Syroeshkin AV, Pleteneva TV, Uspenskaya EV, Levitskaya OV, Tverdislov VA. On the possibility of chiral structure density submillimeter inhomogeneities existing in water. J Water Chem Technol. 2017;39(6):319-24. doi: 10.3103/S1063455X17060029.

Yurchenko SO, Shkirin AV, Ninham BW, Sychev AA, Babenko VA, Penkov NV. Ion-specific and thermal effects in the stabilization of the gas nanobubble phase in bulk aqueous electrolyte solutions. Langmuir. 2016;32(43):11245-55. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.6b01644, PMID 27350310.

Bunkin NF, Shkirin AV, Suyazov NV, Babenko VA, Sychev AA, Penkov NV. Formation and dynamics of ion-stabilized gas nanobubble phase in the bulk of aqueous NaCl solutions. J Phys Chem B. 2016;120(7):1291-303. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b11103, PMID 26849451.

Syroeshkin AV, Uspenskaya EV, Levitskaya OV, Kuzmina ES, Kazimova IV, Quynh HT. New approaches to determining the D/H ratio in aqueous media based on diffuse laser light scattering for promising application in deuterium-depleted water analysis in antitumor therapy. Sci Pharm. 2024;92(4):63. doi: 10.3390/scipharm92040063.

Petrov GV, Galkina DA, Koldina AM, Grebennikova TV, Eliseeva OV, Chernoryzh YYU. Controlling the quality of nanodrugs according to their new property, radiothermal emission. Pharmaceutics. 2024;16(2):180. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics16020180, PMID 38399241.

Kim DJ, Jo ES, Cho YK, Hur J, Kim CK, Kim CH. A frequency reconfigurable dipole antenna with solid-state plasma in silicon. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):14996. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-33278-1, PMID 30301910.

Meng X, Guo J, Peng J, Chen J, Wang Z, Shi JR. Direct visualization of concerted proton tunnelling in a water nanocluster. Nature Phys. 2015;11(3):235-9. doi: 10.1038/nphys3225.

Petrov GV, Koldina AM, Ledenev OV, Tumasov VN, Nazarov AA, Syroeshkin AV. Nanoparticles and nanomaterials: a review from the standpoint of pharmacy and medicine. Pharmaceutics. 2025;17(5):655. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics17050655, PMID 40430945.

Stepanov GO, Penkov NV, Rodionova NN, Petrova AO, Kozachenko AE, Kovalchuk AL. The heterogeneity of aqueous solutions: the current situation in the context of experiment and theory. Front Chem. 2024;12:1456533. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2024.1456533, PMID 39391834.

Epstein O. The supramolecular matrix concept. Symmetry. 2023;15(10):1914. doi: 10.3390/sym15101914.