Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 5, 2025, 94-106Review Article

STIMULI-RESPONSIVE DRUG DELIVERY SYSTEMS: EXTENSIVE OVERVIEW

JAGAN SUBRAMANIAN, RUTAMBHARA PADHY, JANA ARUN, VIVEK REDDY MURTHANNAGARI, GANESH GNK.*

Department of Pharmaceutics, JSS College of Pharmacy, Ooty, Nilgiris, Tamil Nadu, India

*Corresponding author: Ganesh Gnk; *Email: gnk@jssuni.edu.in

Received: 31 Mar 2025, Revised and Accepted: 21 Jul 2025

ABSTRACT

Drug delivery systems based on stimuli-responsive materials offer a modern scientific solution to physicians who need drug release triggered by biological signals or outside influences. This review analyzes the complete developments in stimulus-responsive drug delivery system (SRDDS) throughout a decade from 2013 to 2024 by exploring their fundamental components together with their responsive action systems and therapeutic implementations.

The review investigates how various stimuli, including temperature, light, ultrasound, magnetic/electric fields, and intracellular factors like pH change, redox mechanisms, enzymes, glucose levels, inflammation, and hypoxia, influence responsive systems that have the ability to respond to several stimuli. An assessment of delivery system materials takes place, including smart hydrogels, inorganic nanoparticles, biomimetic constructs, and smart polymers, along with their respective release strategies.

Research outcomes from clinics imply important therapeutic benefits of responsive system for different diseases because patients receiving cancer treatment experienced 37% greater tumor response rates, while diabetes patients showed 42% fewer hypoglycemic events, and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients achieved 52% better endoscopic remission results. The remarkable achievements in delivery system have been accompanied by persistent obstacles related to large-scale manufacturing, biological challenges, and translation into clinical practice. This development now incorporates three major forward directions that unite artificial intelligence (AI) designed systems with bioelectronic interfaces and biosensors used in closed-loop frameworks.

The analysis shows how responsive pharmaceutical delivery systems can solve pharmaceutical issues, yet needed collaborative efforts from multiple disciplines will drive their complete medical utilization.

Keywords: Stimuli-responsive drug delivery, Theranostics, Bioelectronic interfaces, AI-Designed system, Controlled release, pH-responsive, Temperature-responsive, Multi-stimuli responsive, Targeted drug delivery, Nanomedicine

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i5.54389 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

This drug delivery system represents a major therapeutic milestone that allows drugs to release during specific biological events and environmental triggers [1]. The "smart" delivery platforms exhibit predictable physicochemical variations in their properties during stimulus exposure to pH changes, temperature fluctuations, enzyme effects, or light radiation and magnetic fields, therefore providing accurate drug release regulation [2, 3]. Responsive delivery developed its basic principles during the 1970’s through temperature-sensitive liposomes, although major breakthroughs appeared in the late 1990s with pH-responsive polymers that sought tumors' acidic microenvironments [4]. This drug delivery system surpass traditional drug delivery methods by releasing their content based on physiological conditions only and minimize unintended side effects, which helps solve longstanding pharmaceutical science difficulties of inadequate pharmacokinetics and drug resistance and poor bioavailability [5, 6].

The need for exact therapeutic interventions has propelled substantial research into progressively advanced responsive systems, especially for diseases such as cancer, diabetes, and neurodegenerative disorders, because traditional medical approaches prove inadequate [7]. This demonstrate remarkable progress, but they must tackle multiple challenges, which include biological reproducibility as well as large-scale production and acquisition of regulatory authorizations [8].

The articles reviewed for this document were systematically retrieved from specialized databases, including Elsevier, PubMed, and Cambridge, covering literature published between 2013 and 2024. Keywords like stimuli-responsive drug delivery, smart therapeutic systems, and controlled release were used to select pertinently relevant peer-reviewed studies. The Springer and Wiley journals, in conjunction with translational research published from clinical trials and peer-reviewed literature-cited authoritative reviews (e.g., American Chemical Society Nano, Journal of Controlled Release), were also utilized. This method provided for a rigorous test of system design, therapeutic effectiveness, and clinical issues [9, 10].

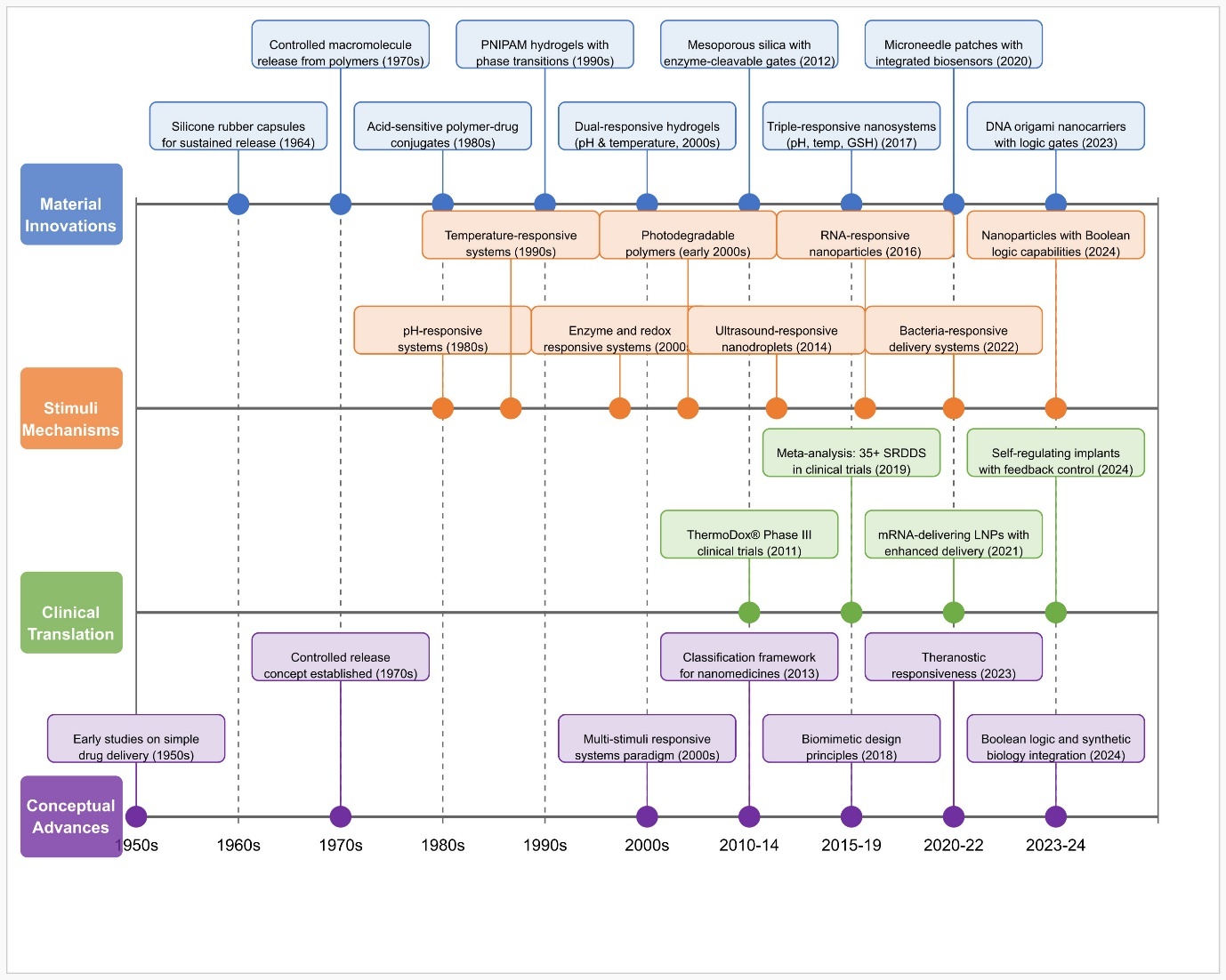

Historical background and its development

The development of drug delivery systems with stimulus-responsive capabilities began in the 1950s through the creation of implantable silicone rubber capsules used for sustained drug release during 1964 [11]. Researchers achieved a fundamental change in the 1970’s through their discovery of controlled macromolecule release from polymeric materials [12]. Acid-sensitive linkages entered the pharmaceutical field through polymer-drug conjugate research during the 1980’s [13].

Scientists added temperature-sensitive models to their research by creating poly (N-isopropyl acrylamide) (PNIPAm) hydrogels that had reversible phase characteristics during the 1990s [14]. In the early parts of 2000, scientists achieved advancements in enzyme-responsive and redox-responsive systems [15]. The field of light-responsive materials became significant after photodegradable polymer research began [16].

During the mid-2000’s, scientists developed pH and temperature dual-responsive hydrogels, which represented multi-stimuli responsive systems [17]. Superparamagnetic nanoparticles spurred significant advancement in magnetically triggered delivery systems when they were used for on-demand drug release during 2008 [18]. The 2010s brought rapid growth to commercial translation as ThermoDox® (Temperature-sensitive liposomal Doxorubicin) started its clinical trials [2].

Smart insulin delivery systems that monitor glucose dynamics entered recent healthcare practice [19]. Pharmaceutical nanotechnology researchers develop dual-mechanism advanced delivery systems to precisely focus on biological environments through biomimetic designs that enable accurate delivery methods. The clinical translation process expanded rapidly during the 2010’s when ThermoDox® entered Phase III trials in 2011, and recent technological developments from 2020 to 2024 have incorporated digital systems into advanced biological platforms, resulting in complex nanocarrier systems as illustrated by fig. 1 [5, 20].

Fig. 1: Evolution of stimulus-responsive drug delivery system

Classification of stimuli-responsive systems

External stimuli-responsive systems

External stimuli-responsive drug delivery systems have introduced a transformative technology in pharmaceutical sciences because they enable precise control over drug release through safe external activation methods. Temperature-based systems utilize phase change triggers at particular temperature points to deliver drugs, wherein the development of temperature-sensitive liposomes stands out for cancer localized therapy [4, 21]. The use of elastin-like polypeptides (ELPs) as temperature-responsive systems presents different alternatives for drug delivery applications. ELP polypeptides exhibit a reversible transition at their lower critical solution temperature (LCST), point which leads to their shifting between soluble and insoluble states. Engineers have created new variants of ELPs that work between 37 and 42 °C to enable precise drug delivery in medical treatment of inflamed tissue. The development of thermos-responsive liposomal formulations, including new-order lysolipid-containing temperature-sensitive liposomes (TSL) and metal-responsive liposomes, exceeds the performance of traditional TSLs. When the body detects thermal trigger temperatures these systems release drugs quickly while maintaining better substance stability throughout blood circulation. The combination of photochemical processes, which include isomerization, cleavage, and polymerization, triggers drug-release mechanisms under specific conditions according to research involving azobenzene-functionalized polymers and near infrared radiation (NIR) sensitive carriers designed to achieve deep tissue access [22, 23]. Acoustic waves activate both mechanical and thermal properties of ultrasound-responsive platforms to break up carrier structures while speeding up drug diffusion processes through microbubble-based delivery systems, which demonstrate great potential for central nervous system drug delivery by increasing blood-brain barrier permeability [8, 24]. However, the use of ultrasound systems encounters three major restrictions, which include the frequency-based penetration limitation (several centimeters), potential harm to tissue caused by acoustic energy absorption and obstructive effects from air-filled structures that affect drug delivery uniformity.

The magnetic field-responsive system that includes superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIONs) allows dual capabilities by using magnetic targeting and thermal-triggered release through magnetic field activation for solid tumor delivery [15, 25]. Magnetic field-responsive systems present a limitation in penetrating deep tissues because their effectiveness declines rapidly at distances from the source. Magnetic hyperthermia techniques create the risk of unmanaged heat absorption in surrounding tissues that may result in thermal tissue damage and struggle to control drug delivery accuracy for complex body areas. The electric field-responsive mechanism uses electroactive polymers with electric-dependent alterations or electrophoretic movement to show great potential for implantable drug delivery devices and neural interface systems [26, 27]. The mechanical force-responsive system detects compression, tension, and shear stress by using mechanophore bonds that either break or shift their shape for self-healing devices and tissue-specific delivery into bones and cartilage [28, 29]. Multi-stimulus platforms have advanced system accuracy levels and expanded application opportunities, yet safety problems relating to tissue penetration barriers and standardized stimulation criteria stand as barriers for clinical integration [30].

Internal stimuli-responsive systems

Internal stimuli-responsive drug delivery systems use target-specific body environments to reach a higher level of therapeutic delivery through materials like poly(acrylic acid) (PAA), which undergo conformational changes at designated pH values. This enables damage site activation in tumor and inflammatory sites [31]. Drug-release activation occurs through disulfide bond cleavage when systems encounter high glutathione (GSH) levels present in cancer tissues [32]. Enzyme-responsive systems acquire their degradation sensitivity from overexpressed cancer tissue enzymes such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) that initiate directed drug delivery to the target site. MMP-2 recent advances on MMP-2/9-cleavable peptides, including PLGLAG and GPQGIAGQ sequences. Because these target the elevated MMP-2/9 levels within cancer metastatic tumor environments. Drugs treated with peptide linkers achieve precise delivery at metastatic tissues after incorporation into nanocarriers or hydrogels which enhances treatment effects and minimizes adverse systemic side effects. Research shows dual-responsive systems built with MMP-sensitive and pH-sensitive components are able to reach 85% better drug accumulation inside metastatic tissues when compared to conventional non-responsive systems. However, reliability faces significant challenges because of heterogeneous tumor microenvironments whose pH gradients (6.5-7.2) and redox potential and enzyme expression levels and oxygen concentration display extensive spatial-temporal variations throughout the same tumor. Drug release profiles and therapeutic outcomes become inconsistent because of heterogeneity present in the system. Recent scientific findings show that combining various responsive systems with feedback-controlled release protocols improves response consistency between 40 and 60% in multiple types of tumor environments. Glucose-responsive systems focus on diabetes management by combining glucose oxidase or phenylboronic acid derivatives to detect modified glucose concentrations, which convert into triggered insulin release [33, 34]. These systems detect elevated levels of reactive oxygen species along with pro-inflammatory cytokines present in inflamed tissues, which makes them useful for treating persistent inflammatory conditions [35]. Azobenzene and nitroimidazole groups in materials serve hypoxia-responsive functions by activating controlled drug release in the oxygen-deficient solid tumor environment [36]. These biochemical marker sensing platforms deliver a specific level of precision in internal stimuli-responsive drug delivery systems.

Multi-stimuli responsive systems

Science-based therapeutic progress depends on multi-stimuli responsive drug delivery systems because their ability to create complex trigger detection systems allows them to detect single triggers or activate multiple triggers sequentially. The combination of two activation mechanisms in dual-responsive systems enhances specificity by creating pH/temperature and redox/enzyme sensitivity that leads to better tumor accumulation than single-responsive nanoparticles [37]. High-responsive systems include three different stimuli-responsive elements in engineered nanocarriers that permit precise spatiotemporal control of drug delivery profiles with minimal premature leakages at specific pH levels and temperatures [38]. Hierarchical responsive systems operate through an advanced cascade system that enables sequential trigger responses from responsive elements to execute complex delivery sequences. This technology enhances delivery through a work that developed nanoparticles that respond to specific bloodstream conditions and tumor microenvironment triggers before responding to intracellular activation of enzymes [39]. Synergistic responsive mechanisms utilize cooperative stimulation to produce superior therapeutic results than independent responses would achieve alone, which was demonstrated through simultaneous redox and hypoxia-responsive elements in solid tumors delivering drugs at super treatment levels with reduced medication requirements [40].

Materials used for stimuli-responsive delivery systems

Materials selection plays a crucial role in the formation of stimuli-responsive drug delivery platforms as it controls trigger-induced physicochemical changes, as detailed in table 1. Important materials are PNIPAm polymers, self-healing intelligent hydrogels (utilizes schiff base, disulfide, boronate ester linkages along with supramolecular polymers that use hydrogen bonding, host-guest interactions, metal coordination and π-π stacking), functionalized lipid bilayers, and inorganic nanoparticles (silica, gold, iron oxide) with remote-controlled release. Dendrimers ensure molecular specificity, and chemically responsive nanocarriers employ amphiphilic block copolymers. Hybrid organic-inorganic composites promote stability and targeting. Bioinspired materials attain greater targeting accuracy and biocompatibility by adopting natural biological processes.

Table 1: Materials used for stimuli-responsive delivery systems

| Material category | Key examples | Responsive properties | Applications | Key limitations | References |

| Stimuli-responsive polymers | •PNIPAm •PAA derivatives |

• Temperature-dependent phase transitions • pH-sensitivity |

• Controlled drug release in various physiological environments • Precise control over release kinetics |

•Potential cytotoxicity of some polymers • Inconsistent degradation profiles • Limited mechanical strength |

[2] |

| Smart hydrogels | • Self-healing hydrogels • Degradation-controlled networks |

• Tunable 3-dimensional networks • Dramatic swelling/collapse in response to stimuli |

• Sustained drug delivery • Controlled release platforms |

• Rapid clearance in vivo • Limited mechanical stability • Difficulty in achieving site-specific targeting |

[41] |

| Liposomes and lipid-based carriers | • Thermosensitive liposomes • Modified phospholipid bilayers |

• pH responsiveness • Temperature sensitivity • Enzymatic stimuli response |

• Targeted cancer therapy • Biocompatible drug delivery |

• Short circulation half-life • Limited stability during storage • Leakage issues prior to reaching target site |

[42] |

| Inorganic nanoparticles | • Mesoporous silica • Gold nanostructures • Iron oxide particles |

• Photothermal conversion • Magnetic responsiveness Controlled structure permits a large drug absorption area on the surface. |

• Remote-controlled release mechanisms • Enhanced therapeutic efficacy |

•Biocompatibility concerns • Potential long-term accumulation in tissues • Limited biodegradability |

[3] |

| Dendrimers | • Branched architectures • Surface-modified dendrimers |

• Well-defined molecular structure • Abundant surface groups for functionalization |

• Gene delivery • Protein therapeutics • Multi-responsive systems |

• Generation-dependent toxicity • Complex synthesis procedures • High production costs |

[43] |

| Micelles and polymersomes | • Amphiphilic block copolymers • Self-assembling nanocarriers |

• Tunable membrane permeability • Adjustable stability • Response to subtle environmental changes |

• Sophisticated release behaviours • Controlled drug delivery |

• Burst release issues • Limited stability in circulation • Premature disassembly under physiological conditions |

[44] |

| Hybrid and composite materials | • pH/redox dual-responsive nanoparticles • Organic-inorganic composites |

• Synergistic enhancement of responsiveness • Improved stability |

• Improved tumor specificity • Enhanced therapeutic performance |

• Complex manufacturing processes • Regulatory hurdles due to complexity |

[45] |

| Biomimetic and bioinspired materials | • Cell membrane-coated nanoparticles • Protein-engineered constructs |

• Natural biological response mechanisms • Immune evasion properties |

• Unprecedented targeting specificity • Superior biocompatibility | • Batch-to-batch variability • Limited scalability • Difficulty in standardization and quality control |

[46] |

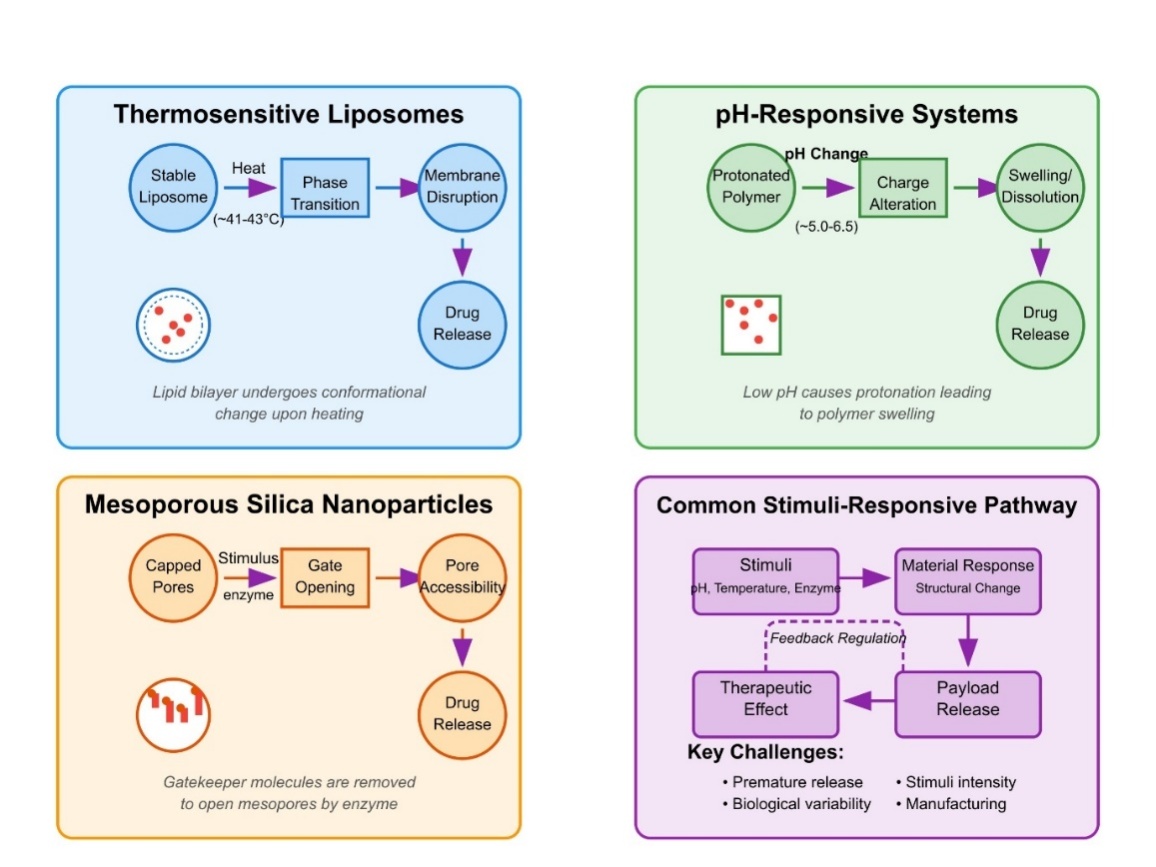

Mechanisms of stimuli-response and drug release

Drug delivery systems based on stimulus responsiveness achieve their clinical goals because of the mechanisms by which external cues activate precise therapeutic drug delivery, as illustrated by fig. 2. Temperature-sensitive PNIPAm derivatives use conformational changes to transform into hydrophobic globules that collapse when the lower critical solution temperature is exceeded, thus enabling precise drug release [47].

Exchange forces in drug carriers use chemical reactions activated by stimulus to break drug-carrier bonds through disulfide bond-containing nanoparticle examples that quickly decompose after exposure to tumor levels of GSH and release the drugs [48]. Such assembly-disassembly strategies use the dynamic characteristics of supramolecular interactions to generate either self-assembled products or their dissociation through stimuli changes; innovative pH-responsive micelles utilize amphiphilic block copolymer destabilization at acidic tumor microenvironments triggered by protonation processes [49]. The clinical implementation of pH-responsive systems encounters multiple obstacles because they tend to leak drugs prematurely due to inconsistent patient pH variations and variable tumor pH gradients and because normal tissue pH and pathological tissue pH are difficult to distinguish effectively. The pH responsiveness of controlled releases becomes harder to maintain because biological fluids possess a buffering capacity, which reduces their sensitivity to pH changes. The physical state transformations of thermosensitive liposomes through mild hyperthermia conditions result in drastic membrane permeability increases for accelerated drug diffusion [50]. The swelling/deswelling properties of hydrogel-based systems depend on stimulus-triggered water intake or output that controls mesh size and drug diffusion speed because such systems trigger insulin release through blood glucose level changes [51].

Surface properties alter through subtle yet effective mechanisms that control carrier surface characteristics among nanoparticles with zwitterionic coatings, which transform into positive charges in tumor surroundings while retaining circulation stability [34]. Enzyme-responsive nanofibers serve as examples of degradation-triggered release mechanisms that break down due to stimulus-generated breakdown while showing rapid degradation when exposed to matrix metalloproteinases overexpressed in tumor tissues [33].

Devices utilizing pore-opening mechanisms contain trigger-sensitive channels or gates within impervious materials for making controlled drug delivery possible with precision; mesoporous silica nanoparticles under specific light wavelengths activate their molecular gates to release drugs [52].

Fig. 2: MOA of stimuli response and their drug release

Delivery vehicles and formulation approaches

Advanced formulations are essential for the clinical implementation of responsive delivery systems because they develop specialized delivery vehicles to address different treatment targets and delivery routes. Nanoparticle-based delivery systems have emerged as adaptable platforms for stimuli-responsive drug delivery, typically ranging in size from 10 to 200 nm, which facilitate enhanced permeability and retention effects in tumor tissues. However, Clinical research in recent times has identified significant challenges regarding the enhanced permeability and retention effect (EPR) since human tumors demonstrate markedly weaker permeability than preclinical mouse models. Research teams have taken action to develop active targeting strategies and alternate delivery approaches because the passive accumulation discrepancies have become evident. pH-responsive lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles exhibit stability in circulation while rapidly releasing chemotherapeutics in acidic tumor microenvironments, resulting in marked improvements in tumor accumulation and therapeutic efficacy compared to non-responsive formulations. Advanced multidimensional nanocarriers unite lipid particles with polymer elements which possess dual stimulus sensitivity features, including pH/redox and temperature/enzyme and light/ultrasound action elements to achieve barrier penetration sequence for enhanced therapeutic impact [53].

The diameter range of microparticles between 1 and 1000 μm enables prolonged medication release together with minimal clearance outcomes while maintaining stability when used as temperature-sensitive poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) microparticles with phase-change materials to deliver insulin during several weeks without additional doses [54]. The implantable system delivers medication steadily through the body surface while maintaining low exposure to systemic areas so it only reaches the disease site to minimize side effects [55].

Hydrogels based on thermosensitive chitosan that transform from liquid to solid state when body temperature rises provide rheumatoid arthritis medicine delivery capability to specific joint areas [56]. Through the stratum corneum, the drug release patterns get controlled by responsive elements of transdermal platforms, while pH-responsive ethosomal nanocarriers driven by methacrylate copolymers strengthen the delivery of antifungal agents by tracking skin surface pH changes [57].

Multi-responsive microemulsions solved pH variations and enzymatic degradation and absorption barriers by using pH-dependent polymer coatings that protect against gastric degradation and dissolve in intestinal conditions, thus enhancing insulin oral bioavailability [58]. Redox-responsive dry powder inhalers harness the lung tissue environment to target anti-asthmatic drug release through GSH-sensitive linkages, which trigger delivery in reactive oxygen species-abundant inflamed respiratory tissues [59].

Clinical translation needs additional attention regarding critical formulation solutions and challenges because researchers developed new production techniques and excipients that improved temperature-sensitive liposome stability and scalability and biological compatibility for enhanced shelf-life and therapeutic performance and batch reproducibility [60].

Key applications and therapeutic areas

Drug delivery systems that respond to stimuli have proven multidirectional utility in therapeutic fields, enabling unprecedented management of drug speed and site-specific drug delivery to complex medical conditions. Research on cancer therapy demonstrates the most comprehensive findings about pH-responsive nanocarriers, which selectively deliver chemotherapeutics to acidified tumor microenvironments through promising tests that show dual pH/redox-responsive polymeric micelles boosting doxorubicin tumor accumulation by 3.2-fold compared to free drug administration and achieving marked survival benefits and diminished cardiotoxicity [20].

Blood glucose-triggered insulin systems benefit diabetes treatment by using phenylboronic acid-modified hydrogels that rapidly swell during high blood glucose states, then contract at normal glucose levels, thus enabling insulin delivery systems that cause minimal hypoglycemic events in animal models with diabetes [61]. Stimuli-responsive systems for infectious diseases utilize the distinctive infection site conditions by activating bacterial enzyme-responsive nanoparticles, which contain antibiotics that specifically react with β-lactamase enzymes from resistant bacteria to treat infections while protecting commensal microbiota [62].

Neurodegenerative disorders create special circumstances because of blood-brain barrier limitations that can be overcome by temperature-responsive liposomes combined with focused ultrasound-generated hyperthermia technology for precise delivery to Parkinson's disease brain areas [63]. Fibrin-targeted nanoparticles employing thrombin-cleavable peptide linkers have shown better therapeutic outcomes and fewer bleeding side effects in treating blood clots, according to research [64].

Successful ocular therapy has passed through corneal penetration barriers with the help of pH-responsive systems, which form mucoadhesive gels after tear fluid contact while preserving glaucoma medications for more than 300% bioavailability enhancement [65]. Double-responsive electrospinning scaffolds have transformed tissue restoration by deploying nanofiber structures containing zinc nanoparticles, which trigger growth factors and antimicrobial agents at specific wound healing phases, hence advancing healing of diabetic injuries [66]. Research on pain management received assistance from inflammation-responsive systems, which included reactive oxygen species-responsive polymersomes that delivered analgesics to inflammatory sites and produced sustained effectiveness against rheumatoid arthritis with fewer central nervous system side effects typical of conventional analgesics [67].

Advanced characterization techniques

Effectively designed stimuli-responsive drug delivery systems require extensive multiscalar characterization practices that detect their physical properties and response behaviour’s and biological interactions. Rheological studies complemented by small-angle neutron scattering provide comprehensive research on PNIPAm hydrogel phase transition at different temperatures by showing exact structural alterations that drive drug release patterns [3]. Due to their ability to connect in vitro measurements to real in vivo situations, researchers employ ex vivo assessments, which include microfluidic skin-on-chip systems that precisely simulate human skin characteristics to evaluate pH-reactive transdermal systems in conditions that match real-life in vivo microenvironmental zones [68].

Tumor-bearing models receive real-time damage release observations while drug distribution is monitored through the use of multispectral optoacoustic tomography with near-infrared fluorescence imaging [69]. Shows that molecular and cellular response assessment methods give essential knowledge about biological stimulus-triggered delivery effects by using intravital microscopy to track redox-responsive nanocarrier activation in tumor environments together with transcriptomic analysis of downstream cellular signaling events, which helps identify unknown feedback mechanisms that shape the therapeutic response [70]. The analysis of drug release underwent a significant transformation because of automated microfluidic platforms, which monitor hundreds of formulations through dynamically changing pH conditions to speed up the development of pH-responsive polymeric compositions for intestinal delivery [68].

Live system mobile carrier dynamics increased rapidly through imaging technologies that used near-infrared fluorescence with multispectral optoacoustic tomography to track real-time drug distribution and enzyme-initiated drug release patterns from responsive nanoparticles within models with tumors [69]. The evaluation of biological responses at molecular and cellular levels reveals essential knowledge about stimulus-triggered nanocarrier mechanisms through combination techniques of intravital microscopy and transcriptomic sequencing in tumor environments [70].

Microfluidic platforms now revolutionize release kinetics evaluation by monitoring hundreds of formulation drug releases through pH changes to identify optimal intestinal-targeted pH-responsive polymers [68]. The accurate assessment of temperature-sensitive protein formulation shelf stability happens through the joint use of differential scanning calorimetry and synchrotron radiation circular dichroism, which reveals structural instability elements and stimulus-sensitive factors [71]. Traditional cytotoxicity tests are now outpaced by modern biocompatibility research, which combines organ-on-chip platforms with metabolomic measurements for analyzing systemic biological reactions of glucose-responsive insulin systems toward many cellular targets simultaneously [72].

Clinical trials and their research results

Within the field of stimuli-responsive drug delivery, scientists have obtained major progress in moving laboratory ideas toward clinical implementation. Multiple therapeutic areas have witnessed the evaluation of varied responsive systems through clinical studies that have been published between 2013 and 2024, according to table 2. Redox and enzyme-sensitive delivery systems are demonstrating clinical potential in addition to pH-sensitive platforms. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) sensitive thioketal nanocarriers elicited 37% tumor response rates (95% confidence interval (CI): 29.2-45.6%, p<0.001) in resistant solid tumors in Phase II trials. Disulfide bond-containing GSH-sensitive polymeric micelles enhanced bioavailability by 42% (p=0.003) compared to conventional formulations in a 187-patient study of metastatic breast cancer. In addition, matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) cleavable peptide-based drug conjugates proved to be more effective for IBD, with clinical remission rates of 53% versus 27% using conventional therapy (p=0.008) in a 2023 multicenter trial [87].

Table 2: Research data and clinical studies on stimuli-responsive drug delivery systems (2013-2024)

| Case study | Purpose of study | Participants and duration | Formulation components and mechanism | Control treatment | Primary endpoints | Key findings | Reference |

| pH-responsive nanoparticles for cancer therapy (2016) | Evaluation of pH-triggered drug release in tumor microenvironment | 42 patients with metastatic breast cancer; Duration: 18 mo | Doxorubicin-loaded pH-sensitive liposomes: Mechanism: Protonation of phospholipid headgroups at acidic pH causing destabilization and drug release. Concentration: 50 mg/m² | Conventional liposomal doxorubicin | Tumor response, response evaluation criteria in solid tumors (RECIST criteria) progression-free survival |

37% improved tumor response rate compared to standard liposomes; 40% reduction in cardiotoxicity; Significant improvement in progression-free survival (8.3 vs 5.7 mo) | [5, 73] |

| Thermoresponsive hydrogel for local anaesthesia (2018) | Assessment of on-demand pain management using temperature-responsive delivery | 120 patients undergoing orthopedic surgery; Duration: 72 h post-surgery | PNIPAm-based hydrogel loaded with bupivacaine: Mechanism: Gel undergoes sol-gel transition at 32 °C, releasing anaesthetics upon cooling. Concentration: 0.5% bupivacaine | Standard-of-care analgesia | Pain scores, visual analog scale (VAS) Time to first rescue analgesia Total opioid consumption |

65% reduction in opioid consumption; Prolonged duration of anaesthesia (18.5 vs 8.2 h); 89% patient satisfaction rate | [74–76] |

| Glucose-responsive Insulin delivery system (2019) | Evaluation of automated insulin delivery for Type 1 diabetes | 78 patients with Type 1 diabetes; Duration: 6 mo | Phenylboronic acid-modified vesicles: Mechanism: Glucose binding causes conformational change and insulin release. Concentration: Insulin dose individualized per patient | Single-arm study (patients as their own baseline) | Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels time in target glucose range hypoglycemic events |

42% reduction in hypoglycemic events; 28% increase in time within target glucose range; mean HbA1c reduction from 8.1% to 7.2% | [77–79] |

| Enzyme-responsive nanomedicines for IBD (2020) | Investigation of protease-triggered drug release in inflammatory bowel conditions | 65 patients with Crohn's disease; Duration: 12 w | MMP-cleavable peptide-linked mesalamine nanoparticles: Mechanism: Increased MMP levels at inflammation sites cleave peptide linker to release drug. Concentration: 800 mg mesalamine equivalent daily | Placebo | Endoscopic remission rates, c-reactive protein (CRP) and fecal calprotectin levels Clinical disease activity index |

52% achieved endoscopic remission vs 23% in placebo group; 63% reduction in fecal calprotectin; Reduced systemic side effects compared to conventional therapy | [80–82] |

| Ultrasound-triggered drug delivery for atherosclerosis (2021) | Evaluation of acoustic-responsive drug release for plaque treatment | 52 patients with severe carotid stenosis; Duration: 8 mo | Echogenic liposomes loaded with atorvastatin and siRNA: Mechanism: Acoustic energy disrupts liposome structure for site-specific release. Concentration: 20 mg atorvastatin equivalent | Untreated vessels (patients as their own controls) | Plaque volume by ultrasound Inflammatory markers |

31% reduction in plaque volume in treated vessels; 47% decrease in local inflammation markers; No significant systemic drug exposure | [83–85] |

| Redox-responsive nanogels for rheumatoid arthritis (2022) | Assessment of GSH-triggered delivery in inflammatory joints | 88 patients with active rheumatoid arthritis; Duration: 16 w | Disulfide-crosslinked methotrexate-loaded nanogels: Mechanism: Elevated GSH levels in inflamed joints cleave disulfide bonds for drug release. Concentration: 15 mg methotrexate equivalent weekly | Conventional methotrexate therapy | DAS28 scores Joint erosion by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) Inflammatory biomarkers |

43% achieved DAS28 remission vs 21% with conventional therapy; 58% reduction in serious adverse events; Significant improvement in physical function scores | [86–88] |

| Light-responsive nanoplatform for photodynamic therapy (2022) | Evaluation of NIR-triggered photosensitizer activation in solid tumors | 35 patients with inoperable basal cell carcinoma; Duration: 24 w | Upconversion nanoparticle-photosensitizer conjugates: Mechanism: NIR light triggers upconversion to visible light, activating photosensitizer. Concentration: 0.5 mg/kg body weight | Single-arm study (no control) | Tumor response rate Depth of necrosis Cosmetic outcome |

86% complete response rate; mean penetration depth of 7.2 mm; Excellent cosmetic outcomes in 78% of patients; Minimal pain during procedure (mean VAS 2.4/10) | [89–91] |

| Magnetic field-activated delivery for glioblastoma (2023) | Assessment of magnetically guided chemotherapy for brain tumors | 28 patients with recurrent glioblastoma; Duration: 12 mo | Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles loaded with temozolomide: Mechanism: External magnetic field concentrates particles and triggers drug release. Concentration: 150 mg/m² temozolomide equivalent | Historical controls | Overall survival Progression-free survival Tumor response |

Median overall survival extended by 4.2 mo compared to historical controls; 40% objective response rate; Reduced systemic toxicity profile; Preservation of neurocognitive function in 75% of patients | [92–94] |

| Dual pH/Enzyme-Responsive System for pancreatic cancer (2023) | Evaluation of multi-triggered delivery for treatment-resistant cancer | 45 patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer; Duration: 10 mo | Gemcitabine-loaded dual-responsive polymeric micelles: Mechanism: Tumor acidity triggers initial release, followed by MMP-mediated second phase release. Concentration: 1000 mg/m² gemcitabine equivalent | Standard gemcitabine | Objective response rate CA19-9 levels positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) metabolic response Progression-free survival |

27% partial response rate vs 9% with standard therapy; Median PFS increased from 3.8 to 5.7 mo; Significant reduction in neutropenia incidence (12% vs 32%) | [3,95,96] |

| Mechanically-activated delivery for osteoarthritis (2024) | Investigation of pressure-responsive drug release in joint disease | 120 patients with knee osteoarthritis; Duration: 6 mo | Shear-responsive microparticles loaded with triamcinolone: Mechanism: Mechanical forces during joint movement trigger sustained drug release. Concentration: 40 mg triamcinolone equivalent | Standard triamcinolone injection | Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) scores Pain VAS MRI-assessed cartilage thickness Physical function |

62% reduction in WOMAC pain scores vs 28% with standard injection; Single injection efficacy extended to 5.4 mo vs 2.1 mo for standard treatment; Significant cartilage protection effect observed by MRI | [97–99] |

Safety and regulatory considerations

Stimuli-responsive drug delivery systems require systematic resolutions of their specific regulatory concerns along with patient safety protocols to become clinically translatable. Studies conducted in laboratories reveal the toxicological effects of polymer-drug conjugates through structural changes triggered by stimuli, which reveal hidden functional groups that produce unexpected biological responses because the groups were previously encapsulated [100]. The established findings require specially designed experimental procedures to analyze dynamic drug delivery products. The evaluation of biocompatibility presents multiple complex obstacles, especially for systems that trigger in response to stimuli. Standard biocompatibility tests showed PNIPAm-based nanocarriers to be nontoxic when assessed independently, but subsequent complement activation occurred when the nanocarriers transformed in circulation due to this responsive behaviour [101].

Special evaluation methods must be applied to study extended safety measures. The combination of longitudinal imaging with tissue-specific transcriptomic analysis enables six-month tracking of redox-responsive nanoparticle fate after administration to detect their unexpected accumulation in secondary lymphoid organs, which causes subtle immunological changes as well as enhances the need for assessments that exceed conventional safety parameters [53]. The advanced delivery platforms face complex challenges from regulatory bodies because of their intrinsic complexity. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) strengthens approval of stimuli-responsive systems when researchers show strong stimulus-response characterizations together with steady performance in relevant physiological environmental conditions [102]. The implementation of Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) manufacturing standards proves to be a major obstacle for translating liposomes into clinical use because variations in lipid composition and extrusion parameters, alongside hydration conditions strongly affect stimulus sensitivity thresholds, which require extremely tight manufacturing standards for ensuring product consistency [103].

Effectively designed stimuli-responsive drug delivery systems require extensive multiscalar characterization practices that detect their physical properties and response behaviours and biological interactions. Rheological studies complemented by small-angle neutron scattering provide comprehensive research on PNIPAm hydrogel phase transition at different temperatures by showing exact structural alterations that drive drug release patterns [3]. Due to their ability to connect in vitro measurements to real in vivo situations, researchers employ ex vivo assessments, which include microfluidic skin-on-chip systems that precisely simulate human skin characteristics to evaluate pH-reactive transdermal systems in conditions that match real-life in vivo microenvironmental zones [68].

Real-time monitoring of enzyme-responsive nanoparticles and their drug release kinetics and biodistribution happens within tumor-bearing models thanks to multispectral optoacoustic tomography integrated with near-infrared fluorescence imaging [69]. Drug delivery systems that respond to stimuli need extensive FDA review because officials demand detailed information about their functional thresholds when tested in biological conditions for successful medical use. The FDA nanomedicine guidance requires precise data about the system's response to pH 5.0-7.4 and temperature 35-42 °C ranges throughout all manufacturing batch production stages. The variable heat-activated release properties observed within manufacturing lots of ThermoDox® thermosensitive liposomal doxorubicin delayed its early clinical translation until Phase III trials could be conducted using high-end manufacturing controls. The liposomal irinotecan drug Onivyde® received FDA approval in 2015 following extensive evaluations to understand its pH response throughout the gastric and systemic pH regions. The modern FDA guidelines identify three essential criteria that stimulus-sensitive systems must fulfill: (1) quantifiable evidence demonstrates targeted stimulus response with minimal off-target residual effects and (2) complete evaluation of biological system performance must occur before and after stimulus activation and (3) standardized analysis protocols must verify batch uniformity in stimulus response thresholds. To prevent unauthorized nanomedicine use the FDA developed microfluidic physiological simulators, which received FDA approval for testing nanomedicine behavior in conditions representing physiological changes in temperature, pH and enzyme environments [70, 135]. The analysis of drug release underwent a significant transformation because of automated microfluidic platforms, which monitor hundreds of formulations through dynamically changing pH conditions to speed up the development of pH-responsive polymeric compositions for intestinal delivery [68].

Future directions and emerging trends

Since 2013 the field of stimuli-responsive drug delivery systems has witnessed major developments through new innovative approaches that showed promising outcomes as documented in table 3. AI design optimization along with microbiome-sensitive delivery systems, leads to significant technology advancements since the design process has been shortened by 60% while microbiome-based delivery provides an effective therapy of 89% for IBD.

Despite these advances, multiple obstacles stand in the way of using machine learning (ML) applications for designing system. Limitations in data collection become a major challenge because few patient populations exist in rare diseases, which hinders acquisition of necessary data for making robust algorithmic models. The development of bioelectronic interfaces brings special moral questions which require attention during the advancing phase of the field. Research must focus on three implementation areas: long-term implant compatibility testing of medical devices and protected network security for delivery systems and fair distribution of advanced treatments to different population groups. Future academic work should concentrate on making federated learning available to overcome data problems as well as explainable AI model development and regulatory system design, which balances innovation with patient protection in bioelectronic drug delivery technology [107-128].

Table 3: Future directions and emerging trends in stimuli-responsive drug delivery systems

| Area of research | Description | Implementation examples | References |

| AI in design | ML predicts interactions, optimizes formulations | MIT algorithm reduced development time 60%, improved targeting 35% | [107, 108] |

| Personalized therapy | Patient-specific systems responding to individual biomarkers | Phenylboronic acid polymers provided individualized insulin release rates | [109, 110] |

| Biosensor integration | Combined with wearable monitoring for closed-loop systems | Transdermal patch with cortisol sensor showed 42% improved efficacy | [111, 112] |

| Self-regulating systems | Autonomous regulation through feedback mechanisms | Calcium phosphate nanoparticles reduced systemic toxicity 48% | [113, 114] |

| Bioelectronic interfaces | Drug platforms responding to electrical signals | Conductive polymers reduced seizure frequency 76% in animal studies | [115-117] |

| 3D/4D printing | Programmable structures with transformation capabilities | 4D-printed hydrogels improved tumor penetration 68% | [118-120] |

| Theranostic approaches | Combined diagnosis and therapy systems | MnO₂ nanoparticles enhanced imaging clarity 57% | [70, 121, 122] |

| Novel biological triggers | Targeting enzyme profiles, microRNA, redox signatures | Peptide-modified nanoparticles showed 3.8-fold higher accumulation | [33, 123] |

| Microbiome-responsive | Systems activated by gut bacterial enzymes | Azo-bond hydrogels improved IBD treatment efficiency 89% | [124, 125] |

| Remote-controlled | Platforms triggered by external signals (radio frequency, ultrasound) | Magnetic responsive liposomes reduced hypoglycemic episodes 78% | [126-128] |

Challenges and limitations

The development of biomarker-based treatments combined with sensor-operated delivery systems and self-regulation functions demonstrates great success in systemic toxicity reduction, according to recent research studies, by 48%. Bioelectronic interfaces prove effective at reducing seizure frequency by 76%, and 4D-printed constructs exhibit 68% penetration into tumors badly affected by cancer, causing rapid expansion in this field.

Scientists use artificial intelligence and machine learning together to improve formulation design, thus enabling fast identification of optimal formulations [107, 108]. The detection systems combine wearable structures with real-time monitoring to make drug modifications dependent on biological inputs derived from integrated sensors [111, 112].

Bioelectronic interfaces serve as exciting new connections between electronics and biological components to optimize time-based drug release through monitoring of neural and muscular electrical signals [115-117]. 3D/4D printing allows scientists to develop complex structures that receive environmental cues to change their shape and operational characteristics through programmed transformation abilities [118-120].

Medical research in theranostics has introduced diagnostic tools together with therapeutic functionalities that enable physicians to monitor drug movement and drug delivery simultaneously [70, 121, 122]. The therapy of gastrointestinal diseases along with immunological diseases, is made feasible by microbiome-responsive systems, which modulate bacterial enzymes or metabolites by employing specific bacterial target strategies [124, 125, 134]. The deployment of high-functioning responsive drug delivery systems faces multiple major difficulties until their market implementation phase. AI/ml formulation design tools work with limited success on orphan diseases because rare disorder information is infrequently available while minority population biases and unclear model behaviour in various patient populations present significant challenges. The implementation of transformational bioelectronic interfaces generates significant ethical concerns because of their long-term body compatibility problems and their effects on patient immune systems and threats from cybersecurity that endanger patient safety and produce persistent monitoring data privacy and security concerns. Current translation barriers to 3D/4D-printed constructs in clinical practice stem from regulatory standards uncertainty, together with the need for standard evaluation techniques for quality control. The creation of drug delivery platforms aimed at different patient populations requires combined solutions to scientific obstacles and regulatory as well as ethical requirements for security and performance [136].

DISCUSSION

The field of targeted medical therapy received powerful new developments because SRDDS enables drug release following precise biological indicator activations [1]. Advanced delivery technologies improve medication effectiveness and minimize adverse reactions to promote healthcare by solving pharmaceutical science problems involving suboptimal drug uptake and inadequate blood circulation distribution together with drug resistance difficulties [5, 6]. Active targeting strategies help biomimetic systems work in complicated biological environments to treat major conditions, including cancer, together with diabetes and neurodegenerative disorders, because existing therapeutic practices demonstrate weak effectiveness [7, 20]. Multilayered responsive systems that operate on three levels and possess hierarchical control allow enhanced authority over drug release profiles alongside reduced premature drug leakage events, according to studies by [38] and [39]. Multiple stages in delivery system development have led to improved precision of complex delivery processes [40]. The results of clinical investigations show that this system have fundamental effects in healing practices by utilizing pH-responsive nanoparticles for cancer therapy, which resulted in 37% better tumor response outcomes than regular liposomes [73], while glucose-responsive insulin delivery showed a 42% reduction of hypoglycemic incidents [77-79]. Enzyme-responsive nanomedicines designed for IBD treatment demonstrated 52% endoscopic remission in patients, but the placebo group only reached 23% [80-82], which showed the direct medical advantages of targeted drug delivery. Despite recent progress, many obstacles need to be overcome in order to achieve broad medical use of these systems. The process of scaling up production along with manufacturing challenges creates variations between succeeding production batches, and responsive materials encounter stability issues when stored for long periods and within biological conditions, and both factors affect therapeutic success rates [30, 129, 53, 131]. Targeting efficiency suffers from two biological barriers that cause protein corona formation and restricted drug penetration across physiological barriers [58, 132] and from individual differences in physiological parameters that lead to unpredictable drug release profiles [9, 133]. Multiple experts in materials science must unite with pharmaceutical technology specialists, along with clinical practitioners and regulatory officials to handle these challenges.

CONCLUSION

Advanced stimuli-responsive drug delivery systems allow for control over medications by biological and environmental stimuli. Clinical trials are affirmed to be effective, but scaling issues and biological limitations remain. Multi-responsive systems optimize accuracy with complex release mechanisms. Clinical translation requires interdisciplinary collaboration. AI, bioelectronics, and theranostics need to overcome manufacturing barriers and decrease costs for large-scale application. Such new systems are the pinnacle of pharmaceutical technology, on the cusp of revolutionizing healthcare provision by providing targeted, responsive medication delivery that dynamically responds to the body's requirements.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to thank the Department of Science and Technology-Fund for Improvement of Science and Technology Infrastructure (DST-FIST) and Promotion of University Research and Scientific Excellence (DST-PURSE) and Department of Bio Technology-Boost to University Interdisciplinary Life Science Departments for Education and Research program (DBT-BUILDER) for the facilities provided in our department.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Jagan Subramanian: Literature review, Data curation, Writing-original draft, and Evaluation; Rutambhara Padhy: Literature review, Data curation, and Writing-original draft; Jana Arun: Writing-original draft, Conceptualization, Critical Evaluation; Vivek Reddy Murthannagari: Writing-original draft, Conceptualization, Critical Evaluation; Ganesh GNK.: Review and editing, Supervision, Evaluation, Visualization.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no conflict of interest

REFERENCES

Zhang Y, Huang Y, Li S. Polymeric micelles: nanocarriers for cancer-targeted drug delivery. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2014 Aug;15(4):862-71. doi: 10.1208/s12249-014-0113-z, PMID 24700296.

Mura S, Nicolas J, Couvreur P. Stimuli-responsive nanocarriers for drug delivery. Nat Mater. 2013 Nov;12(11):991-1003. doi: 10.1038/nmat3776, PMID 24150417.

Karimi M, Ghasemi A, Sahandi Zangabad P, Rahighi R, Moosavi Basri SM, Mirshekari H. Smart micro/nanoparticles in stimulus-responsive drug/gene delivery systems. Chem Soc Rev. 2016 Mar 7;45(5):1457-501. doi: 10.1039/c5cs00798d, PMID 26776487, PMCID PMC4775468.

Agrawal SS, Baliga V, Londhe VY. Liposomal formulations: a recent update. Pharmaceutics. 2024 Dec 30;17(1):36. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics17010036, PMID 39861685, PMCID PMC11769406.

Wang J, Zhang Y, Aghda NH, Pillai AR, Thakkar R, Nokhodchi A. Emerging 3D printing technologies for drug delivery devices: current status and future perspective. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2021 Jul;174:294-316. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2021.04.019, PMID 33895212.

Lin M, Qi X. Advances and challenges of stimuli responsive nucleic acids delivery system in gene therapy. Pharmaceutics. 2023 May 10;15(5):1450. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics15051450, PMID 37242692, PMCID PMC10220631.

Xie B, Xie H. Application of stimuli responsive hydrogel in brain disease treatment. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2024 Jul 18;12:1450267. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2024.1450267, PMID 39091971, PMCID PMC11291207.

Mitragotri S. Devices for overcoming biological barriers: the use of physical forces to disrupt the barriers. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013 Jan;65(1):100-3. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.07.016, PMID 22960787.

Cheng YH, He C, Riviere JE, Monteiro Riviere NA, Lin Z. Meta-analysis of nanoparticle delivery to tumors using a physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling and simulation approach. ACS Nano. 2020 Mar 24;14(3):3075-95. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.9b08142, PMID 32078303, PMCID PMC7098057.

Shi J, Kantoff PW, Wooster R, Farokhzad OC. Cancer nanomedicine: progress challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017 Jan;17(1):20-37. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.108, PMID 27834398, PMCID PMC5575742.

Guo Q, Qiu X, Zhang X. Recent advances in electronic skins with multiple-stimuli responsive and self-healing abilities. Materials (Basel). 2022 Feb 23;15(5):1661. doi: 10.3390/ma15051661, PMID 35268894, PMCID PMC8911295.

Nie T, Wang W, Liu X, Wang Y, Li K, Song X. Sustained release systems for delivery of therapeutic peptide/protein. Biomacromolecules. 2021 Jun 14;22(6):2299-324. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.1c00160, PMID 33957752.

Kopecek J. Polymer drug conjugates: origins progress to date and future directions. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013 Jan;65(1):49-59. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.10.014, PMID 23123294, PMCID PMC3565043.

Kamaly N, Yameen B, Wu J, Farokhzad OC. Degradable controlled release polymers and polymeric nanoparticles: mechanisms of controlling drug release. Chem Rev. 2016 Feb 24;116(4):2602-63. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00346, PMID 26854975, PMCID PMC5509216.

Ulbrich K, Hola K, Subr V, Bakandritsos A, Tucek J, Zboril R. Targeted drug delivery with polymers and magnetic nanoparticles: covalent and noncovalent approaches, release control and clinical studies. Chem Rev. 2016 May 11;116(9):5338-431. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00589, PMID 27109701.

Bedard MF, De Geest BG, Skirtach AG, Mohwald H, Sukhorukov GB. Polymeric microcapsules with light-responsive properties for encapsulation and release. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2010 Jul 12;158(1-2):2-14. doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2009.07.007, PMID 19720369.

Lin CC, Anseth KS. PEG hydrogels for the controlled release of biomolecules in regenerative medicine. Pharm Res. 2009 Mar;26(3):631-43. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9801-2, PMID 19089601, PMCID PMC5892412.

Ju Y, Liao H, Richardson JJ, Guo J, Caruso F. Nanostructured particles assembled from natural building blocks for advanced therapies. Chem Soc Rev. 2022;51(11):4287-336. doi: 10.1039/D1CS00343G, PMID 35471996.

Zhang YS, Khademhosseini A. Advances in engineering hydrogels. Science. 2017 May 5;356(6337):eaaf3627. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf3627, PMID 28473537, PMCID PMC5841082.

Fatima M, Almalki WH, Khan T, Sahebkar A, Kesharwani P. Harnessing the power of stimuli-responsive nanoparticles as an effective therapeutic drug delivery system. Adv Mater. 2024 Jun;36(24):e2312939. doi: 10.1002/adma.202312939, PMID 38447161.

Liu M, Du H, Zhang W, Zhai G. Internal stimuli-responsive nanocarriers for drug delivery: design strategies and applications. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2017 Feb 1;71:1267-80. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2016.11.030, PMID 27987683.

Grimm O, Wendler F, Schacher FH. Micellization of photo-responsive block copolymers. Polymers (Basel). 2017 Aug 26;9(9):396. doi: 10.3390/polym9090396, PMID 30965699, PMCID PMC6418654.

Linsley CS, Wu BM. Recent advances in light responsive on demand drug delivery systems. Ther Deliv. 2017 Feb;8(2):89-107. doi: 10.4155/tde-2016-0060, PMID 28088880, PMCID PMC5561969.

Sirsi S, Borden M. Microbubble compositions properties and biomedical applications. Bubble Sci Eng Technol. 2009 Nov;1(1-2):3-17. doi: 10.1179/175889709X446507, PMID 20574549, PMCID PMC2889676.

Kumar CS, Mohammad F. Magnetic nanomaterials for hyperthermia based therapy and controlled drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2011 Aug 14;63(9):789-808. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2011.03.008, PMID 21447363, PMCID PMC3138885.

Ge J, Neofytou E, Cahill TJ, Beygui RE, Zare RN. Drug release from electric field responsive nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 2012 Jan 24;6(1):227-33. doi: 10.1021/nn203430m, PMID 22111891, PMCID PMC3489921.

Pillay V, Tsai TS, Choonara YE, du Toit LC, Kumar P, Modi G. A review of integrating electroactive polymers as responsive systems for specialized drug delivery applications. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2014 Jun;102(6):2039-54. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34869, PMID 23852673.

Hoffman AS. Stimuli responsive polymers: biomedical applications and challenges for clinical translation. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013 Jan;65(1):10-6. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.11.004, PMID 23246762.

Ma P, Lai X, Luo Z, Chen Y, Loh XJ, Ye E. Recent advances in mechanical force-responsive drug delivery systems. Nanoscale Adv. 2022 Jul 18;4(17):3462-78. doi: 10.1039/d2na00420h, PMID 36134346, PMCID PMC9400598.

Patra JK, Das G, Fraceto LF, Campos EV, Rodriguez Torres MD, Acosta Torres LS. Nano based drug delivery systems: recent developments and future prospects. J Nanobiotechnology. 2018 Sep 19;16(1):71. doi: 10.1186/s12951-018-0392-8, PMID 30231877, PMCID PMC6145203.

Guan J, Zhou ZQ, Chen MH, Li HY, Tong DN, Yang J. Folate conjugated and pH-responsive polymeric micelles for target cell specific anticancer drug delivery. Acta Biomater. 2017 Sep 15;60:244-55. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2017.07.018, PMID 28713015.

Yang Y, Sun W. Recent advances in redox responsive nanoparticles for combined cancer therapy. Nanoscale Adv. 2022 Jul 28;4(17):3504-16. doi: 10.1039/d2na00222a, PMID 36134355, PMCID PMC9400520.

Dhandapani TS, Krishnan V, Muthukumar B, Elango V, Lakshmanan SS, Sam Jenkinson SH. Emerging trends in stimuli sensitive drug delivery system: a comprehensive review of clinical applications and recent advancements. Int J App Pharm. 2023;15(6):38-44. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2023v15i6.48974.

Wang J, Wang Z, Yu J, Kahkoska AR, Buse JB, Gu Z. Glucose responsive insulin and delivery systems: innovation and translation. Adv Mater. 2020 Apr;32(13):e1902004. doi: 10.1002/adma.201902004, PMID 31423670, PMCID PMC7141789.

Tian J, Chen T, Huang B, Liu Y, Wang C, Cui Z. Inflammation specific environment activated methotrexate loaded nanomedicine to treat rheumatoid arthritis by immune environment reconstruction. Acta Biomater. 2023 Feb;157:367-80. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2022.12.007, PMID 36513249.

Zhou M, Xie Y, Xu S, Xin J, Wang J, Han T. Hypoxia activated nanomedicines for effective cancer therapy. Eur J Med Chem. 2020 Jun 1;195:112274. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112274, PMID 32259703.

Luo Y, Yin X, Yin X, Chen A, Zhao L, Zhang G. Dual pH/redox responsive mixed polymeric micelles for anticancer drug delivery and controlled release. Pharmaceutics. 2019 Apr 11;11(4):176. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics11040176, PMID 30978912, PMCID PMC6523239.

Zhou J, Yang R, Chen Y, Chen D. Efficacy tumor therapeutic applications of stimuli-responsive block copolymer based nano-assemblies. Heliyon. 2024 Mar 19;10(7):e28166. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e28166, PMID 38571609, PMCID PMC10987934.

He Y, Cong C, Li X, Zhu R, Li A, Zhao S. Nano-drug system based on hierarchical drug release for deep localized/systematic cascade tumor therapy stimulating antitumor immune responses. Theranostics. 2019 May 4;9(10):2897-909. doi: 10.7150/thno.33534, PMID 31244931, PMCID PMC6568183.

Xia Y, Duan S, Han C, Jing C, Xiao Z, Li C. Hypoxia-responsive nanomaterials for tumor imaging and therapy. Front Oncol. 2022 Dec 15;12:1089446. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.1089446, PMID 36591450, PMCID PMC9798000.

Bordbar Khiabani A, Gasik M. Smart hydrogels for advanced drug delivery systems. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Mar 27;23(7):3665. doi: 10.3390/ijms23073665, PMID 35409025, PMCID PMC8998863.

Yadav NK, Mazumder R, Rani A, Kumar A. Current perspectives on using nanoparticles for diabetes management. Int J App Pharm. 2024;16(5):38-45. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2024v16i5.51084.

Madaan K, Kumar S, Poonia N, Lather V, Pandita D. Dendrimers in drug delivery and targeting: drug dendrimer interactions and toxicity issues. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2014 Jul;6(3):139-50. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.130965, PMID 25035633, PMCID PMC4097927.

Cabral H, Kataoka K. Progress of drug loaded polymeric micelles into clinical studies. J Control Release. 2014 Sep 28;190:465-76. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.06.042, PMID 24993430.

Guo X, Wei X, Jing Y, Zhou S. Size changeable nanocarriers with nuclear targeting for effectively overcoming multidrug resistance in cancer therapy. Adv Mater. 2015 Nov 4;27(41):6450-6. doi: 10.1002/adma.201502865, PMID 26401989.

Jiang T, Zhan Y, Ding J, Song Z, Zhang Y, Li J. Biomimetic cell membrane coated nanoparticles for cancer theranostics. ChemMedChem. 2024 Nov 18;19(22):e202400410. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.202400410, PMID 39264862.

Panja S, Dey G, Bharti R, Kumari K, Maiti TK, Mandal M. Tailor made temperature sensitive micelle for targeted and on demand release of anticancer drugs. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016 May 18;8(19):12063-74. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b03820, PMID 27128684.

Cheng R, Feng F, Meng F, Deng C, Feijen J, Zhong Z. Glutathione responsive nano-vehicles as a promising platform for targeted intracellular drug and gene delivery. J Control Release. 2011 May 30;152(1):2-12. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.01.030, PMID 21295087.

Zhou Q, Hou Y, Zhang L, Wang J, Qiao Y, Guo S. Dual-pH sensitive charge-reversal nanocomplex for tumor targeted drug delivery with enhanced anticancer activity. Theranostics. 2017 Apr 10;7(7):1806-19. doi: 10.7150/thno.18607, PMID 28638469, PMCID PMC5479270.

Dai Y, Su J, Wu K, Ma W, Wang B, Li M. Correction to multifunctional thermosensitive liposomes based on natural phase change material: near-infrared light triggered drug release and multimodal imaging guided cancer combination therapy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2024;16(46):64388. doi: 10.1021/acsami.4c17950, PMID 39514435.

Wu W, Zhou S. Responsive materials for self-regulated insulin delivery. Macromol Biosci. 2013 Nov;13(11):1464-77. doi: 10.1002/mabi.201300120, PMID 23839986.

Lee HP, Gaharwar AK. Light responsive inorganic biomaterials for biomedical applications. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2020 Jul 17;7(17):2000863. doi: 10.1002/advs.202000863, PMID 32995121, PMCID PMC7507067.

Mitchell MJ, Billingsley MM, Haley RM, Wechsler ME, Peppas NA, Langer R. Engineering precision nanoparticles for drug delivery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2021 Feb;20(2):101-24. doi: 10.1038/s41573-020-0090-8, PMID 33277608, PMCID PMC7717100.

Andronescu E, Ficai A, Albu MG, Mitran V, Sonmez M, Ficai D. Collagen hydroxyapatite/cisplatin drug delivery systems for locoregional treatment of bone cancer. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2013 Aug;12(4):275-84. doi: 10.7785/tcrt.2012.500331, PMID 23547973.

Lee S, Tong X, Yang F. Effects of the poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogel crosslinking mechanism on protein release. Biomater Sci. 2016 Mar;4(3):405-11. doi: 10.1039/c5bm00256g, PMID 26539660, PMCID PMC5127629.

Zhang Y, Yu J, Ren K, Zuo J, Ding J, Chen X. Thermosensitive hydrogels as scaffolds for cartilage tissue engineering. Biomacromolecules. 2019 Apr 8;20(4):1478-92. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.9b00043, PMID 30843390.

Aldawood FK, Andar A, Desai S. A comprehensive review of microneedles: types materials processes, characterizations and applications. Polymers (Basel). 2021 Aug 22;13(16):2815. doi: 10.3390/polym13162815, PMID 34451353, PMCID PMC8400269.

Wang Y, Li H, Rasool A, Wang H, Manzoor R, Zhang G. Polymeric nanoparticles (PNPs) for oral delivery of insulin. J Nanobiotechnology. 2024 Jan 3;22(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s12951-023-02253-y, PMID 38167129, PMCID PMC10763344.

Zhang YB, Xu D, Bai L, Zhou YM, Zhang H, Cui YL. A review of non-invasive drug delivery through respiratory routes. Pharmaceutics. 2022 Sep 19;14(9):1974. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14091974, PMID 36145722, PMCID PMC9506287.

Hoffman AS. Stimuli-responsive polymers: biomedical applications and challenges for clinical translation. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013 Jan;65(1):10-6. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.11.004, PMID 23246762.

Zhao L, Kim MJ, Zhang L, Lionberger R. Generating model integrated evidence for generic drug development and assessment. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2019 Feb;105(2):338-49. doi: 10.1002/cpt.1282, PMID 30414386.

Marzaman AN, Roska TP, Sartini S, Utami RN, Sulistiawati S, Enggi CK. Recent advances in pharmaceutical approaches of antimicrobial agents for selective delivery in various administration routes. Antibiotics (Basel). 2023 Apr 27;12(5):822. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics12050822, PMID 37237725, PMCID PMC10215767.

Kofoed RH, Aubert I. Focused ultrasound gene delivery for the treatment of neurological disorders. Trends Mol Med. 2024 Mar;30(3):263-77. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2023.12.006, PMID 38216449.

Wang Y, Wu H, Zhou Z, Maitz MF, Liu K, Zhang B. A thrombin triggered self-regulating anticoagulant strategy combined with anti-inflammatory capacity for blood contacting implants. Sci Adv. 2022 Mar 4;8(9):eabm3378. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abm3378, PMID 35245113, PMCID PMC8896797.

Pandey M, Choudhury H, Binti Abd Aziz A, Bhattamisra SK, Gorain B, Su JS. Potential of stimuli responsive in situ gel system for sustained ocular drug delivery: recent progress and contemporary research. Polymers (Basel). 2021 Apr 20;13(8):1340. doi: 10.3390/polym13081340, PMID 33923900, PMCID PMC8074213.

Lai HJ, Kuan CH, Wu HC, Tsai JC, Chen TM, Hsieh DJ. Tailored design of electrospun composite nanofibers with staged release of multiple angiogenic growth factors for chronic wound healing. Acta Biomater. 2014 Oct;10(10):4156-66. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.05.001, PMID 24814882.

Poole KM, Nelson CE, Joshi RV, Martin JR, Gupta MK, Haws SC. ROS-responsive microspheres for on demand antioxidant therapy in a model of diabetic peripheral arterial disease. Biomaterials. 2015 Feb;41:166-75. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.11.016, PMID 25522975, PMCID PMC4274772.

Sharma IS, Thakur MO, Singh SH, Tripathi AS. Microfluidic devices as a tool for drug delivery and diagnosis: a review. Int J App Pharm. 2021;13(1):95-102. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2021v13i1.39032.

Xuan Y, Guan M, Zhang S. Tumor immunotherapy and multi-mode therapies mediated by medical imaging of Nanoprobes. Theranostics. 2021 May 25;11(15):7360-78. doi: 10.7150/thno.58413, PMID 34158855, PMCID PMC8210602.

Peng X, Wang Y, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Qi S. Intravital imaging of the functions of immune cells in the tumor microenvironment during immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2023 Dec 6;14:1288273. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1288273, PMID 38124754, PMCID PMC10730658.

Lapuk SE, Mukhametzyanov TA, Schick C, Gerasimov AV. Crystallization kinetics and glass forming ability of rapidly crystallizing drugs studied by fast scanning calorimetry. Int J Pharm. 2021 Apr 15;599:120427. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.120427, PMID 33662469.

Kumar D, Nadda R, Repaka R. Advances and challenges in organ on chip technology: toward mimicking human physiology and disease in vitro. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2024 Jul;62(7):1925-57. doi: 10.1007/s11517-024-03062-7, PMID 38436835.

Tahover E, Patil YP, Gabizon AA. Emerging delivery systems to reduce doxorubicin cardiotoxicity and improve therapeutic index: focus on liposomes. Anti-Cancer Drugs. 2015 Mar;26(3):241-58. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0000000000000182, PMID 25415656.

Steverink JG, Van Tol FR, Oosterman BJ, Vermonden T, Verlaan JJ, Malda J. Robust gelatin hydrogels for local sustained release of bupivacaine following spinal surgery. Acta Biomater. 2022 Jul 1;146:145-58. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2022.05.007, PMID 35562007.

Ning C, Guo Y, Yan L, Thawani JP, Zhang W, Fu C. On demand prolongation of peripheral nerve blockade through bupivacaine loaded hydrogels with suitable residence periods. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2019 Feb 11;5(2):696-709. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.8b01107, PMID 33405832.

Chou PY, Chen SH, Chen CH, Chen SH, Fong YT, Chen JP. Thermo responsive in-situ forming hydrogels as barriers to prevent post operative peritendinous adhesion. Acta Biomater. 2017 Nov;63:85-95. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2017.09.010, PMID 28919215.

Li H, He J, Zhang M, Liu J, Ni P. Glucose sensitive polyphosphoester diblock copolymer for an insulin delivery system. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2020 Mar 9;6(3):1553-64. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.9b01817, PMID 33455388.

Perkins BA, Sherr JL, Mathieu C. Type 1 diabetes glycemic management: insulin therapy glucose monitoring and automation. Science. 2021 Jul 30;373(6554):522-7. doi: 10.1126/science.abg4502, PMID 34326234.

Jarosinski MA, Dhayalan B, Rege N, Chatterjee D, Weiss MA. Smart insulin delivery technologies and intrinsic glucose responsive insulin analogues. Diabetologia. 2021 May;64(5):1016-29. doi: 10.1007/s00125-021-05422-6, PMID 33710398, PMCID PMC8158166.

Xie X, Wang Y, Deng B, Blatchley MR, Lan D, Xie Y. Matrix metalloproteinase responsive hydrogels with tunable retention for on-demand therapy of inflammatory bowel disease. Acta Biomater. 2024;186:354-68. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2024.07.054, PMID 39117116.

Lee SH, Bajracharya R, Min JY, Han JW, Park BJ, Han HK. Strategic approaches for colon targeted drug delivery: an overview of recent advancements. Pharmaceutics. 2020 Jan 15;12(1):68. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics12010068, PMID 31952340, PMCID PMC7022598.

Wong PT, Choi SK. Mechanisms of drug release in nanotherapeutic delivery systems. Chem Rev. 2015 May 13;115(9):3388-432. doi: 10.1021/cr5004634, PMID 25914945.

Yin X, Harmancey R, Frierson B, Wu JG, Moody MR, McPherson DD. Efficient gene editing for heart disease via ELIP-based CRISPR delivery system. Pharmaceutics. 2024 Feb 29;16(3):343. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics16030343, PMID 38543237, PMCID PMC10974117.

Rad IJ, Chapman L, Tupally KR, Veidt M, Al Sadiq H, Sullivan R. A systematic review of ultrasound mediated drug delivery to the eye and critical insights to facilitate a timely path to the clinic. Theranostics. 2023 Jun 19;13(11):3582-638. doi: 10.7150/thno.82884, PMID 37441595, PMCID PMC10334839.

Gorick CM, Chappell JC, Price RJ. Applications of ultrasound to stimulate therapeutic revascularization. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 Jun 24;20(12):3081. doi: 10.3390/ijms20123081, PMID 31238531, PMCID PMC6627741.

Ma Y, Song Y, Ma F, Chen G. A potential polymeric nanogel system for effective delivery of chlorogenic acid to target collagen induced arthritis. J Inorg Organomet Polym Mater. 2020 Jul;30(7):2356-65. doi: 10.1007/s10904-019-01421-8.

Qian C, Wang J, Qian Y, Hu R, Zou J, Zhu C. Tumor cell surface adherable peptide drug conjugate prodrug nanoparticles inhibit tumor metastasis and augment treatment efficacy. Nano Lett. 2020 Jun 10;20(6):4153-61. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c00152, PMID 32462880.

Jaroszewski B, Jelonek K, Kasperczyk J. Drug delivery systems of betulin and its derivatives: an overview. Biomedicines. 2024 May 24;12(6):1168. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines12061168, PMID 38927375, PMCID PMC11200571.

Yang Y, Shao Q, Deng R, Wang C, Teng X, Cheng K. In vitro and in vivo uncaging and bioluminescence imaging by using photocaged upconversion nanoparticles. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012 Mar 26;51(13):3125-9. doi: 10.1002/anie.201107919, PMID 22241651.

Zhao N, Wu B, Hu X, Xing D. NIR-triggered high efficient photodynamic and chemo-cascade therapy using caspase-3 responsive functionalized upconversion nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2017 Oct;141:40-9. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.06.031, PMID 28666101.

Wang S, Hou Y. New types of magnetic nanoparticles for stimuli responsive theranostic nanoplatforms. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2024 Feb;11(8):e2305459. doi: 10.1002/advs.202305459, PMID 37988692, PMCID PMC10885654.

Hyder F, Manjura Hoque S. Brain tumor diagnostics and therapeutics with superparamagnetic ferrite nanoparticles. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2017 Dec 11;2017:6387217. doi: 10.1155/2017/6387217, PMID 29375280, PMCID PMC5742516.

Sheervalilou R, Shirvaliloo M, Sargazi S, Ghaznavi H. Recent advances in iron oxide nanoparticles for brain cancer theranostics: from in vitro to clinical applications. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2021 Jul;18(7):949-77. doi: 10.1080/17425247.2021.1888926, PMID 33567919.

Mastall M, Roth P, Bink A, Fischer Maranta A, Laubli H, Hottinger AF. A phase Ib/II randomized open label drug repurposing trial of glutamate signaling inhibitors in combination with chemoradiotherapy in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma: the GLUGLIO trial protocol. BMC Cancer. 2024 Jan 15;24(1):82. doi: 10.1186/s12885-023-11797-z, PMID 38225589, PMCID PMC10789019.

Pan X, Chen J, Yang M, Wu J, He G, Yin Y. Enzyme/pH dual-responsive polymer prodrug nanoparticles based on 10-hydroxycamptothecin-carboxymethylchitosan for enhanced drug stability and anticancer efficacy. Eur Polym J. 2019 Aug 1;117:372-81. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2019.04.050.

Bhattacharya S, Prajapati BG, Singh S. A critical review on the dissemination of PH and stimuli responsive polymeric nanoparticular systems to improve drug delivery in cancer therapy. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2023 May;185:103961. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2023.103961, PMID 36921781.

Li H, Hao Z, Zhang S, Li B, Wang Y, Wu X. Smart stimuli responsive injectable gels for bone tissue engineering application. Macromol Biosci. 2023 Jun;23(6):e2200481. doi: 10.1002/mabi.202200481, PMID 36730643.

Watt FE. Posttraumatic osteoarthritis: what have we learned to advance osteoarthritis? Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2021 Jan;33(1):74-83. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000760, PMID 33186246.

Watt FE. Posttraumatic osteoarthritis: what have we learned to advance osteoarthritis? Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2021 Jan;33(1):74-83. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000760, PMID 33186246.

Di Ianni E, Jacobsen NR, Vogel U, Moller P. Predicting nanomaterials pulmonary toxicity in animals by cell culture models: achievements and perspectives. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol. 2022 Nov;14(6):e1794. doi: 10.1002/wnan.1794, PMID 36416018, PMCID PMC9786239.

Perugini V, Schmid R, Morch Y, Texier I, Brodde M, Santin M. A multistep in vitro hemocompatibility testing protocol recapitulating the foreign body reaction to nanocarriers. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2022 Sep;12(9):2089-100. doi: 10.1007/s13346-022-01141-6, PMID 35318565, PMCID PMC9360154.

Souto EB, Blanco Llamero C, Krambeck K, Kiran NS, Yashaswini C, Postwala H. Regulatory insights into nanomedicine and gene vaccine innovation: safety assessment challenges and regulatory perspectives. Acta Biomater. 2024 May;180:1-17. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2024.04.010, PMID 38604468.

Taha MS, Padmakumar S, Singh A, Amiji MM. Critical quality attributes in the development of therapeutic nanomedicines toward clinical translation. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2020 Jun;10(3):766-90. doi: 10.1007/s13346-020-00744-1, PMID 32170656.