Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 5, 2025, 253-262Original Article

FROM ALGORITHMS TO EVIDENCE: ASSESSING ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE CHATBOTS AND DRUG DATABASES FOR DETECTING CARDIO-DIABETIC DRUG INTERACTIONS

AFTAB ALAM1,3, ANUKRITI SARAN2, RADHIKA JOSHI1,2, SATHVIK B. SRIDHAR3, SWAPNIL SHARMA1*, SARVESH PALIWAL1

1Department of Pharmacy, Banasthali Vidyapith, Rajasthan-304022, India. 2Department of Bioscience and Biotechnology, Banasthali Vidyapith, Rajasthan-304022, India. 3Department of Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology, RAK College of Pharmacy, RAK Medical and Health Sciences University, Ras Al Khaimah-11172, United Arab Emirates

*Corresponding author: Swapnil Sharma; *Email: skspharmacology@gmail.com

Received: 31 Mar 2025, Revised and Accepted: 09 Jun 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: Electronic drug information resources are widely accessible and commonly used by healthcare professionals for identifying drug-drug interactions (DDIs). With the rapid advancements in artificial intelligence (AI), AI-powered chatbots have demonstrated their potential in detecting DDIs. However, variations exist in the scope, completeness, and consistency of information provided by different resources. This study aims to conduct a comparative evaluation of drug interaction databases and AI chatbots to assess their reliability in DDI identification.

Methods: A total of three databases, namely Lexicomp, Drugs.com, DrugBank and AI-powered chatbots such as ChatGPT, Copilot and Gemini were used for comparative evaluation. The percentage of interactions that had an entry in each drug information resource was used to score each resource for scope. For each resource that described clinical effects, severity, mechanism, clinical management, and risk factors, a completeness score was calculated. The consistency of the information was assessed using the Fleiss' Kappa (κ) score, estimated with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 29.0 (IBM, USA).

Results: A total of 150 drug pairs were selected in the present study. The scope score was highest (100%) for Lexicomp, ChatGPT and Gemini. The completeness score was highest (100%) in all the AI-powered chatbots, followed by Drugs.com (90%) and Lexicomp (85.2%). Fleiss' kappa coefficient was used to determine the inter-resource agreement on DDI severity classification and the overall agreement was categorized as fair (κ=0.28, p<0.001). Cohen’s kappa coefficients were calculated to evaluate pairwise agreement among the resources and the overall mean kappa coefficient (κ=0.51, p<0.01) indicated a moderate level of agreement among the resources.

Conclusion: Significant differences amongst the resources were observed in terms of severity classification. Using Lexicomp as reference, accuracy assessment was done and variable sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values among resources were observed. A moderate overall agreement in the inter-resource agreement on DDI presence-absence, with traditional databases showed stronger pairwise agreement than AI chatbots.

Keywords: Artificial intelligence, Drug interactions, Patient safety, Drug databases, Drug information resources

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i5.54398 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) and diabetes mellitus (DM) are leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide, often coexisting in patients and necessitating polypharmacy for optimal disease management. The concomitant use of cardio-diabetic medications increases the risk of Drug-Drug Interactions (DDIs), which may lead to Adverse Drug Reactions (ADRs), reduced therapeutic efficacy, or enhanced toxicity. Identifying and mitigating these interactions is crucial for ensuring patient safety and optimizing clinical outcomes [1].

According to a report from the World Health Organization, around 1.28 billion adults worldwide between the ages of 30 and 79 suffer from hypertension [2] The International Diabetes Federation estimated that 537 million adults had diabetes in 2021; by 2030, that fig. is expected to increase to 643 million, and by 2045, it will reach 783 million [3].

Diabetes and hypertension often occur together due to shared underlying pathogenic mechanisms. The coexistence of these conditions is not by chance. People with diabetes have twice the risk of having hypertension as people without the disease, and people with hypertension have a higher chance of developing diabetes than people with normal blood pressure [4]. Studies show that 20% of patients with hypertension also have diabetes, while more than 50% of those with diabetes also have hypertension [5].

Several medications are used in tandem to manage both diabetes and hypertension together. Risk factors such as gender, advanced age, multiple pharmacological therapy, and length of hospital stays influence the likelihood of DDIs in patients with such comorbidities. According to research, the potential DDIs linked to a particular antihypertensive or antidiabetic treatment vary depending on the patient's physiological characteristics, the condition being treated, and the level of drug exposure [6].

In the past, pharmacology textbooks or standard electronic drug information (DI) resources like drug databases and clinical decision support systems (CDSS) have been used by medical professionals to recognize and handle DDIs [7]. Information on drug interactions, including severity ratings and clinical management techniques, is organized and supported by evidence in these resources [8]. These resources frequently have restrictions despite their worth. They might not always reflect the subtleties of specific patient characteristics that can affect the clinical importance of a DDI, such as age, comorbidities, and genetic predispositions [9]. Additionally, the sheer amount of data in databases can be daunting, making it difficult for physicians to effectively and efficiently evaluate the overall risk of DDIs in intricate polypharmacy regimens [10]. However, new methods that promise to improve DDI identification and management using sophisticated data analytics and (ML) algorithms have been presented by the quick advances in artificial intelligence (AI) [11].

Recently, in order to improve the detection of ADRs and DDIs, AI has been integrated into pharmacovigilance systems [12, 13]. Studies have shown the capability of Large Language Models (LLMs) including chatbots to extract the information from biomedical literature, regulatory reports, and electronic health records. These chatbots can rapidly detect and analyze DDIs [14, 15]. ultiple previous investigations have revealed the ability of chatbots in identifying and detecting therapeutically important DDIs [16, 17]. A comparative analysis studied the performance of AI-driven and traditional drug interaction software and concluded that AI systems, particularly ChatGPT-3.5, demonstrate significant potential to identify DDIs. Nevertheless, the study also indicated some restrictions, i. e., intermittent nature of the errors and partial mechanistic elucidation [18]. Another recent study contrasted the performance of ChatGPT-3.5 in DDI detection. The results indicated that the model's sensitivity significantly varied depending on the prompt wording style, with better performance when the words "drug interaction" were explicitly written. In spite of this, ChatGPT-3.5 yielded low true positive and high true negative rates [14].

Despite their encouraging performance, the reliability of AI-generated drug interaction data remains to be validated against established authoritative databases. These findings highlight the need to assess AI chatbots for their scope, completeness and diagnostic accuracy in the detection of DDIs. The current study aims to address this gap by systematically comparing traditional DDI databases with newer AI-based tools in the context of cardio-diabetic pharmacotherapy, a domain marked by high polypharmacy risk.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and site

In order to assess how well traditional databases and AI tools identify and manage cardio-diabetic drug interactions, this study uses a systematic review and comparative analysis methodology. The study was carried out at drug information centre, department of clinical pharmacy and pharmacology, RAK College of Pharmacy (RAKCOP), RAK Medical and Health Sciences University (RAKMHSU), Ras Al Khaimah, United Arab Emirates.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was not necessary for this study because it is based on secondary data and does not involve human subjects. However, all DDI pairs were selected based on real-world clinical practice to ensure relevance and applicability to patient care.

Selection of drug interaction pairs

A systematic literature review was conducted to identify potential DDI pairs relevant to the pharmacological management of patients with both CVD and DM. The following inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied:

The inclusion criteria for the study comprised drug pairs that involved at least one antihypertensive or one antidiabetic agent, with drug-drug interactions (DDIs) documented in standard pharmacological references and classified as clinically relevant. Additionally, only interactions supported by human-based evidence, such as clinical studies, case reports, or expert-reviewed references, were considered. On the other hand, the exclusion criteria ruled out drug pairs involving non-cardiovascular and non-diabetic medications, interactions derived solely from animal or in vitro studies, theoretical interactions lacking clinical consequence, and redundant pairs, such as different salts or forms of the same drug combination.

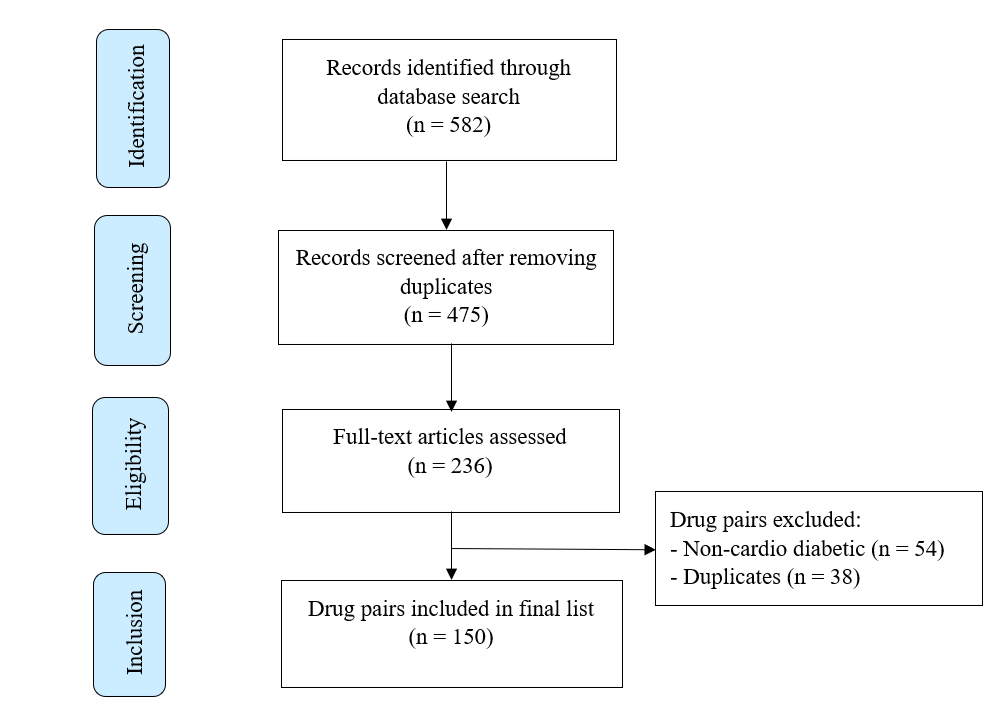

Sources reviewed included clinical pharmacology textbooks, therapeutic guidelines, and indexed databases such as PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science. Search terms included combinations of: “cardiovascular drug interactions,” “antidiabetic DDIs,” “polypharmacy in diabetes,” “CVD-DM drug interactions,” and “clinical relevance of drug interactions. ”Following screening and expert committee review (comprising two academicians, one clinical pharmacist, one community pharmacist, and one physician), 150 drug pairs were finalized for inclusion based on clinical frequency, severity, and prescribing relevance (fig. 1, table 1).

Fig. 1: Selection process of drug interaction pairs

Selection of databases and AI chatbots

Databases

Three established and widely used drug interaction databases were selected as comparators. Among these three databases, one was subscription-based (Lexicomp), while the other two, Drugs.com and DrugBank, were freely accessible. Lexicomp was selected as the reference standard due to its widespread clinical adoption, comprehensive interaction classification, and structured severity grading (major, moderate, minor). Lexicomp is frequently used in CDSS and hospital formularies globally and has been validated in previous drug interaction studies as a benchmark tool [18, 19]. Despite limitations such as subscription-based access that may restrict its availability in low-resource settings, Lexicomp remains one of the most authoritative and evidence-based DDI resources, making it a suitable gold-standard comparator for this study.

AI Chatbots

Three different AI chatbots were selected for evaluation. The selection criteria included availability, accessibility, and reported capabilities in providing drug information. The specific chatbots used were free version of ChatGPT, Copilot and Gemini.

Table 1: List of drug pairs studied

| Drug A | Drug B | ||

| Aliskiren | Sacubitril | ||

| Amiloride | Azilsartan | Olmesartan | Spironolactone |

| Amlodipine | Azilsartan | Atenolol | Bisoprolol |

| Carvedilol | Prazosin | ||

| Atenolol | Clonidine | Chlorthalidone | Diltiazem |

| Furosemide | Losartan | Nicardipine | |

| Telmisartan | Torsemide | Valsartan | |

| Verapamil | |||

| Bisoprolol | Chlorthalidone | Furosemide | Glibenclamide |

| Glimepiride | Glipizide | Insulin aspart | |

| Rilmenidine | |||

| Captopril | Glibenclamide | Losartan | Metformin |

| Spironolactone | |||

| Carvedilol | Canagliflozin | Dapagliflozin | Empagliflozin |

| Furosemide | Losartan | Nicardipine | |

| Spironolactone | Telmisartan | Valsartan | |

| Chlorthalidone | Losartan | Metoprolol | Metformin |

| Telmisartan | Valsartan | ||

| Clonidine | Metoprolol | Prazosin | |

| Enalapril | Eplerenone | Furosemide | Glimepiride |

| Glipizide | Glyburide | Losartan | |

| Metformin | Spironolactone | Telmisartan | |

| Torsemide | |||

| Furosemide | Canagliflozin | Dapagliflozin | Empagliflozin |

| Glimepiride | Hydralazine | Insulin glargine | |

| Lisinopril | Metformin | Metoprolol | |

| Ramipril | Spironolactone | Telmisartan | |

| Hydrochlorothiazide | Atenolol | Canagliflozin | Dapagliflozin |

| Empagliflozin | Glimepiride | Losartan | |

| Metformin | Metoprolol | Pioglitazone | |

| Telmisartan | Valsartan | ||

| Metoprolol | Amlodipine | Canagliflozin | Dapagliflozin |

| Diltiazem | Empagliflozin | Losartan | |

| Insulin glargine | Prazosin | Valsartan | |

| Verapamil | Telmisartan | ||

| Nebivolol | Rilmenidine | ||

| Ramipril | Eplerenone | Glimepiride | Glipizide |

| Losartan | Metformin | Spironolactone | |

| Torsemide | Valsartan | ||

| Spironolactone | Azilsartan | Candesartan | Irbesartan |

| Losartan | Metformin | Olmesartan | |

| Perindopril | Telmisartan | Valsartan | |

| Acarbose | Glipizide | Metformin | Pioglitazone |

| Gliclazide | Linagliptin | Metformin | Vildagliptin |

| Glimepiride | Insulin Regular | Linagliptin | Metformin |

| Pioglitazone | |||

| Glipizide | Canagliflozin | Dapagliflozin | Empagliflozin |

| Metformin | Pioglitazone | ||

| Metformin | Amlodipine | Canagliflozin | Dapagliflozin |

| Empagliflozin | Glibenclamide | Insulin Regular | |

| Nifedipine | Pioglitazone | ||

| Insulin Glargine | Canagliflozin | Dapagliflozin | Empagliflozin |

| Insulin Regular | Linagliptin | Lisinopril | Nebivolol HCl |

| Telmisartan | |||

| Insulin aspart | Candesartan | ||

| Canagliflozin | Amlodipine | Lisinopril | Losartan |

| Dapagliflozin | Amlodipine | Lisinopril | Losartan |

| Empagliflozin | Amlodipine | Lisinopril | Losartan |

| Glyburide | Telmisartan | ||

| Pioglitazone | Nifedipine |

Standardization of AI chatbot queries

To ensure consistency and minimize variability in responses, a standardized prompt was developed for querying AI-based chatbots. The questions asked in the prompt was prepared based on the information available in the Lexicomp. The prompt was carefully structured to elicit comprehensive DDI-related information, including severity classification, clinical effects, mechanisms, risk factors, and management strategies. The following standardized prompt was used across all chatbot queries for each drug pair:

“Act as a database and explain the following drug-drug interaction-related information:

Is there an interaction between Drug A and Drug B?

If yes, check for clinical effects, severity (major/moderate/minor), mechanism, clinical management, and risk factors.”

This prompt was customized only by inserting the relevant drug pair (e. g., Metformin and Ramipril), and a new session was initiated for each query to avoid memory carryover in AI models [18].

In cases where chatbots generated vague or unclear responses, a set framework was applied in order to maintain uniformity in methodology. For example, in response to query of some drug pairs, the chatbot generated answer such as “no direct interaction”. Such responses were recorded as “non-interacting”. The drug pair was marked as “interacting” only when it was clearly stated that there is an interaction between the two drugs.

Drug-drug interaction evaluation process

Each of the 150 DDI pairs was assessed using the selected DI databases and AI chatbots to evaluate their scope, completeness, and accuracy in identifying and characterizing DDIs [18, 20]. Each DDI pair was entered into each of the three databases, and three chatbots using standardized prompt. The standardized prompt used for DDI detection included the names of the two drugs in the pair and requested information about potential interactions. A new conversation was initiated for each drug interaction query [18]. The key information, such as clinical effects, severity, mechanism, clinical management, and risk factors retrieved from all the resources were recorded.

The number of drug pairs with entries in each Drug Information (DI) resource was used to grade each resource for scope. The drug pairs were divided into three groups for scoring purposes, interacting drug pairs, (drug pairs with an interaction that was recorded in the provided DI resource), non-interacting drug pairs, (drug pairs without an interaction that was recorded in the provided DI resource), and not-listed drug pairs (drug pairs without an entry in the provided DI resource). Drug pairs in the not-listed category received a score of zero, while drug pairs that interacted and those that did not received a score of one [20].

To determine the completeness score, five factors were evaluated: the clinical effects, severity, mechanism, clinical management, and risk factors of the drug interactions that were found. For every component recorded, each interacting drug pair received a score of one. The total number of interacting drug pairings in that specific resource was then divided by the sum of the individual scores to determine the overall completeness score [20].

These datasets and the AI chatbots evaluating encounters were analyzed to ascertain their true positive (TP), true negative (TN), false positive (FP), and false negative (FN) values. Lexicomp (Wolters Kluwer, USA), was used as a reference database and accessed through the library of RAK Medical and Health Sciences University. If a drug interaction that is classified as major or moderate in Lexicomp is also classified as such in other databases, it is called a TP; if it is classified as minor or non-existent in other databases, it is called a FN. Conversely, a minor interaction found in Lexicomp is classified as FP if it is a major/moderate interaction in other databases, and as TNif it is a minor/no interaction in other databases [18].

Statistical evaluation

The database's ability to consistently detect major or moderate drug interactions is known as sensitivity, while its ability to ignore minor interactions is known as specificity. The positive predictive value (PPV) is the probability that an interaction identified by the database is a significant interaction. The probability that interactions not found in the database are not significant is known as the negative predictive value (NPV). These metrics are widely used in pharmacovigilance. To evaluate the diagnostic performance of each resource, the following standard diagnostic metrics were calculated [16, 18]:

Sensitivity =

Specificity =

PPV =

NPV =

These metrics provide a more nuanced and clinically relevant understanding of the tools' abilities to detect true interactions and avoid false alerts. Instead of using a composite “accuracy score,” each parameter was reported and interpreted independently to reflect real-world applicability.

Sensitivity and PPV indicate how well a resource identifies and confirms clinically relevant interactions. Specificity and NPV measure the tool’s ability to rule out non-significant interactions, thereby avoiding false alarms [16].

Additionally, using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 29.0, IBM, USA), kappa (κ) coefficients were employed to evaluate the consistency of severity among the resources. The agreement among the databases and chatbots about the severity of drug interactions was evaluated using Fleiss' kappa coefficient. To compare the resources pairwise, Cohen's kappa coefficient was calculated [20, 21].

A kappa coefficient of 0 denotes agreement that would be expected by chance,-1 denotes perfect disagreement, and 1 denotes perfect agreement. The value of kappa coefficient of<0.0 indicates poor agreement, 0.0-0.2 slight agreement, 0.21-0.40 fair agreement, 0.41-0.60 moderate agreement, 0.61-0.80 substantial agreement, and 0.81-1.00 near perfect agreement. The calculated p-value of kappa coefficients less than 0.05 denotes that the agreement between drug interaction tools and chatbots is unlikely to be due to chance [18].

The decision to employ both pairwise and overall agreement statistics was guided by the need to comprehensively evaluate the consistency and reliability of severity classifications across drug interaction tools. This dual approach allowed for quantification of internal consistency, highlighting the extent to which individual tools aligned with one another in categorizing interaction severity. Additionally, it facilitated the identification of specific resources that most frequently deviated from the reference standard, thereby pinpointing potential gaps in classification accuracy. These insights are critical for informing actionable recommendations regarding the clinical reliability of severity-based decision support systems and their utility in ensuring safe prescribing practices.

RESULTS

Scope score of the resources studied

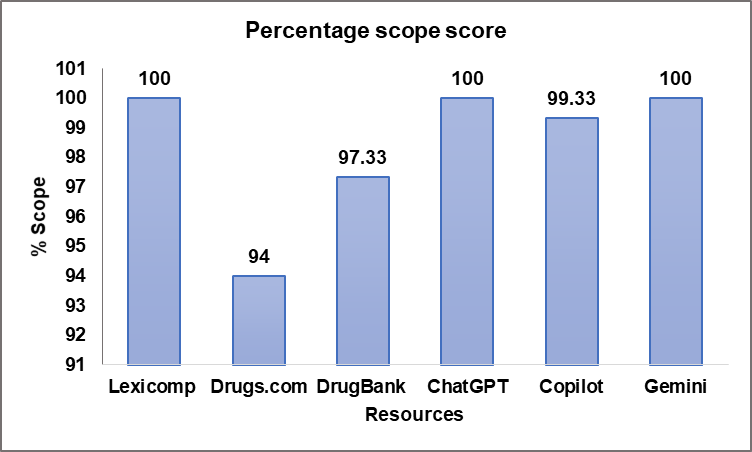

The scope score of the evaluated resources, which determines their ability to list interacting and non-interacting drug pairs, varied across databases and chatbots are seen table 2. All three chatbots (ChatGPT, Copilot, and Gemini) demonstrated the highest scope score of 100%, 99.33%, and 100%, respectively. ChatGPT and Copilot generated “no direct interaction” for 1 and 7 drug pairs respectively. Such responses were classified as “non-interacting” during the scope scoring process. Among the databases, DrugBank achieved a scope score of 97.33%, followed by Drugs.com at 94%, and Lexicomp with a full score of 100% (fig. 2). While all resources showed high coverage, chatbots demonstrated a more comprehensive scope in identifying drug interaction pairs with minimal omissions compared to traditional drug databases.

Table 2: Scope score of the resources studied

| Resources | No. of interacting drug pairs (X) |

No. of non-interacting drug pairs (Y) |

No. of drug pairs not listed |

Total No. of drug pairs [n= 150] | Scope score (X+Y) |

| Lexicomp | 105 | 45 | 0 | 150 | 150 |

| Drugs. com | 117 | 24 | 9 | 150 | 141 |

| DrugBank | 122 | 24 | 4 | 150 | 146 |

| ChatGPT | 145 | 5 | 0 | 150 | 150 |

| Copilot | 137 | 12 | 1 | 150 | 149 |

| Gemini | 150 | 0 | 0 | 150 | 150 |

Fig. 2: Percentage scope score of the resources studied

Completeness score of the resources studied

Completeness was evaluated by assessing the clinical effects, severity, mechanism, clinical management, and risk factors affecting DDIs. As depicted in table 3, chatbots consistently outperformed traditional databases, achieving a 100% completeness score across all parameters. Among databases, Drugs.com exhibited the highest completeness score of 90%, followed by Lexicomp (85.2%). DrugBank had a considerably lower completeness score of 61.6%, primarily due to its limited reporting on clinical management (2.46%) and risk factors (5.74%). These findings highlight a disparity in the comprehensiveness of information provided by drug interaction resources, with chatbots excelling in offering holistic data.

Table 3: Completeness score of the resources studied, (No. of interacting drug pairs [X]; Clinical effects [A]; Severity [B]; Mechanism [C]; Clinical Management [D]; Risk Factors affecting DDIs [E])

| Resources | X | A (%) | B (%) | C (%) | D (%) | E (%) | Overall completeness score [A+B+C+D+E/X] =Z | Overall % completeness score [Z/5×100] |

| Lexicomp | 105 | 105 (100) | 105 (100) | 105 (100) | 105 (100) | 27 (25.71) | 447/105 = 4.26 | 85.2 |

| Drugs.com | 117 | 117 (100) | 117 (100) | 117 (100) | 116 (99.14) | 59 (50.43) | 526/117 = 4.5 | 90 |

| DrugBank | 122 | 122 (100) | 122 (100) | 122 (100) | 3(2.46) | 7 (5.74) | 376/122 = 3.08 | 61.6 |

| ChatGPT | 145 | 145 (100) | 145 (100) | 145 (100) | 145 (100) | 145 (100) | 725/145 = 5 | 100 |

| Copilot | 137 | 137 (100) | 137 (100) | 137 (100) | 137 (100) | 137 (100) | 685/137 = 5 | 100 |

| Gemini | 150 | 150 (100) | 150 (100) | 150 (100) | 150 (100) | 150 (100) | 750/150 = 5 | 100 |

Severity score of DDIs across different resources

Severity categorization of DDIs revealed notable differences among resources mentioned in table 4. Among chatbots, Gemini reported the highest proportion of major interactions (27.33%), followed by Copilot (18.98%) and ChatGPT (15.86%). Conversely, traditional drug databases exhibited varied reporting trends: Drugs.com identified the highest percentage of major interactions (20.51%), whereas Lexicomp (13.34%) and DrugBank (12.30%) reported lower frequencies. The classification of interactions as moderate was predominant across all resources, with Lexicomp (83.80%) and ChatGPT (82.76%) displaying the highest proportion. Minor interactions were more frequently reported by DrugBank (24.59%) and Gemini (16.67%), suggesting a wider stratification of interaction severity. These variations imply potential inconsistencies in severity assessment across different resources, necessitating a standardized approach to classification.

Table 4: Severity score of DDIs across different resources

| Resources | Total severity (Number) | Major n (%) | Moderate n (%) | Minor n (%) |

| Lexicomp | 105 | 14 (13.34) | 88 (83.80) | 3 (2.86) |

| Drugs. com | 117 | 24 (20.51) | 90 (76.92) | 3 (2.57) |

| DrugBank | 122 | 15 (12.30) | 77 (63.11) | 30 (24.59) |

| ChatGPT | 145 | 23 (15.86) | 120 (82.76) | 2 (1.38) |

| Copilot | 137 | 26 (18.98) | 108 (78.83) | 3 (2.19) |

| Gemini | 150 | 41 (27.33) | 84 (56) | 25 (16.67) |

Diagnostic performance of the resources studied

Using Lexicomp as the reference standard, we evaluated the diagnostic performance of each drug interaction resource by calculating four key parameters: sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV as shown in table 5. These metrics reflect the resources’ capacity to correctly identify (TP) or exclude (TN) clinically significant DDIs, specifically those classified as moderate or major.

Among the AI-driven chatbots, ChatGPT showed the highest sensitivity (0.98), followed closely by Copilot (0.96) and Gemini (0.87). This indicates that AI tools are capable of detecting the majority of clinically relevant interactions. However, their specificity was notably.

Low-particularly for Gemini (0.02) and ChatGPT (0.10)-indicating a high false-positive rate.

Traditional databases showed more balanced but moderate

specificity of 0.38, while DrugBank reported a sensitivity of 0.70 and specificity of 0.48. This reflects a more conservative detection pattern with fewer false alerts but a greater likelihood of missing true interactions.

The PPVs observed in the study ranged from 0.65 (Gemini) to 0.75 (Drugs.com and DrugBank), while NPVs were highest for Copilot (0.73) and ChatGPT (0.71), reflecting their strength in confidently ruling out interactions when no alerts are raised.

These results demonstrate a distinct performance trade-off: AI chatbots tend to favor sensitivity at the cost of specificity, often flagging more interactions—many of which may not be clinically meaningful. On the other hand, traditional databases, while avoiding over-alerting, may under-report significant interactions and compromise patient safety.

Agreement analysis on interaction severity

Fleiss' kappa coefficient was used to determine the inter-resource agreement on DDI severity classification (table 6). The overall agreement was categorized as fair (κ=0.28, p<0.001). Agreement on major interactions was slight (κ=0.15), indicating considerable variability in their classification across resources. For moderate interactions, the agreement was fair (κ=0.35), reflecting some level of consistency but still highlighting discrepancies. Minor interactions exhibited the lowest agreement (κ=0.10, p=0.12), suggesting significant inconsistency in their identification. These findings underscore the need for harmonized severity definitions across different DDI resources.

Pairwise agreement on DDI presence and absence

Cohen’s kappa coefficients were calculated to evaluate pairwise agreement among Lexicomp, Drugs.com, DrugBank, and chatbots as shown in table 7. The highest agreement was observed between DrugBank and Gemini (κ=0.71), followed by Drugs.com and DrugBank (κ=0.68). Lexicomp exhibited moderate agreement with DrugBank (κ=0.61) and Drugs. com (κ=0.52), while showing lower agreement with ChatGPT (κ=0.32), Copilot (κ=0.45), and Gemini (κ=0.58). The overall mean kappa coefficient (κ=0.51, p<0.01) indicated a moderate level of agreement among resources. However, the variation in pairwise agreement highlights inconsistencies in the detection of DDIs across resources, emphasizing the need for more standardized methodologies in drug interaction databases and chatbots.

Table 5: Diagnostic performance of drug interaction resources compared to lexicomp as the reference standard

| Resources | TP | FN | TN | FP | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV |

| Drugs. com | 87 | 16 | 18 | 29 | 0.84 | 0.38 | 0.75 | 0.52 |

| DrugBank | 73 | 30 | 23 | 24 | 0.7 | 0.48 | 0.75 | 0.43 |

| ChatGPT | 100 | 2 | 5 | 43 | 0.98 | 0.1 | 0.69 | 0.71 |

| Copilot | 98 | 4 | 11 | 37 | 0.96 | 0.22 | 0.72 | 0.73 |

| Gemini | 89 | 13 | 1 | 47 | 0.87 | 0.02 | 0.65 | 0.07 |

(TP: True Positive; FN: False Negative; FP: False Positive; TN: True Negative; PPV: Positive Predictive Value; NPV: Negative Predictive Value.

Table 6: Fleiss' kappa coefficients for the interaction severity agreements of the resources studied

| Severity | Kappa coefficient | p-value | Strength of agreement |

| Major | 0.15 | <0.001 | Slight |

| Moderate | 0.35 | <0.001 | Fair |

| Minor | 0.10 | 0.12 | Slight |

| Overall | 0.28 | <0.001 | Fair |

Table 7: Cohen’s Kappa coefficients for pairwise agreement on DDI presence-absence

| Lexicomp | Drugs.com | DrugBank | ChatGPT | Copilot | Gemini | |

| Lexicomp | 0.52 | 0.61 | 0.32 | 0.45 | 0.58 | |

| Drugs. com | 0.68 | 0.28 | 0.37 | 0.63 | ||

| DrugBank | 0.41 | 0.49 | 0.71 | |||

| ChatGPT | 0.56 | 0.33 | ||||

| Copilot | 0.65 | |||||

| Overall mean Kappa | 0.51<0.01 Moderate |

DISCUSSION

Hypertension and diabetes mellitus are among the most prevalent chronic conditions globally. The present study was focussed on the clinically important and frequently prescribed antihypertensive and antidiabetic drug pairs, which makes this study different from the other studies done so far. Several studies have been published where the selection of drug pairs was limited to COVID-19 medications in pregnancy and lactation [21], psychiatric drugs [22], oral oncolytics [23] and drug-ethanol drug-tobacco [24], etc.

The comparison of LLMs with traditional DI resources is an emerging area of research. However, only a limited number of studies have explored the discrepancies between these LLMs and online drug databases in accurately identifying DDIs. Using natural language processing methods to help with DDI prediction and explanation has gained popularity in recent years [25, 26]. The three most commonly used Chatbots has been used in the present study. The three databases used in the study are most widely used in the clinical settings. One of these databases was Lexicomp, a subscription-based tool well known to perform best for detecting DDI [18, 23, 24]. Another important reason for selection of these databases was that all the databases classified severity as major, moderate and minor. This formed the basis to include severity as major, moderate and minor in the prompt for asking questions to the AI tools.

The highest-scoring resource in terms of scope was Lexicomp among the other databases. This finding was similar to the other studies done previously [25-29]. On comparative analysis of databases and AI Chatbots it was observed that AI-supported tools performed better in listing interacting and non-interacting pairs compared to traditional databases. The discrepancies observed in the current findings could be due to variations in data sources, update frequency, and inclusion criteria for DDIs.

The differences in scope scores have direct clinical implications. A lower scope score, as seen in Drugs.com (94%), suggests the possibility of missing critical DDIs, potentially leading to medication errors. On the other hand, chatbots, particularly ChatGPT and Gemini, demonstrated higher scope score, which may provide an advantage in real-time clinical decision-making. However, the accuracy of these AI-generated interactions requires validation [30].

Each AI chatbot demonstrated 100% completeness scores across five domains (clinical effects, severity, mechanism, clinical management, and risk factors). To ensure methodological integrity, each parameter was only credited if it was explicitly mentioned in the chatbot’s response. No component was inferred from context, assumed by default, or extrapolated by the evaluators. Each DDI response from chatbots and databases was independently reviewed by two researchers. These findings indicate that chatbots consistently provided comprehensive information, surpassing traditional databases in terms of completeness. This result aligns with recent studies suggesting that AI models, particularly LLMs, can provide complete DDI information retrieval [31].

The finding that Gemini identified DDIs for all 150 drug pairs raises important questions. On the one hand, this could reflect strong comprehensiveness and robust training on large biomedical corpora, potentially making it a reliable first-line screening tool. However, the extremely high sensitivity paired with very low specificity (0.02) suggests that this coverage comes at the cost of high FP rates. This over-alerting may reflect a cautious approach but increases the risk of alert fatigue, which can desensitize healthcare providers to clinically meaningful warnings and result in unnecessary therapeutic modifications or anxiety in patients [14]. Therefore, while the scope is impressive, the accuracy of its predictions must be critically assessed before clinical implementation.

Despite their high scope and completeness scores, AI-based tools such as ChatGPT, Gemini, and Copilot are susceptible to limitations that affect their clinical reliability. One notable concern is the phenomenon of AI hallucinations, where the model generates factually incorrect information that appears plausible, especially in the absence of verifiable source citation. Studies have shown that LLMs may fabricate references, misattribute clinical outcomes, or exaggerate risks without robust backing [32]. This is particularly problematic in high-stakes domains like pharmacovigilance and DDI screening, where misleading information can result in inappropriate clinical decisions.

One of the most notable discrepancies is in the domain of clinical management strategies and risk factors affecting DDIs. Traditional databases, especially Drug Bank, exhibited limitations in these aspects. In contrast, all chatbots provided complete coverage (100%) in these domains. This suggests that chatbots may offer significant guidance for real-world clinical decision-making, potentially improving medication safety and optimizing therapeutic outcomes.

The findings underscore the potential advantages of chatbots in clinical decision support. However, despite their completeness, chatbots may also generate inconsistent information, necessitating rigorous validation before clinical application [33].

On severity assessment, proportion of major interactions varied significantly across the resources. Gemini identified the highest proportion of major interactions (27.33%), whereas DrugBank reported the lowest (12.30%). This variation suggests that chatbots, particularly Gemini, may be more conservative in classifying interactions as major.

The majority of identified DDIs across the evaluated platforms were of moderate severity. Lexicomp and ChatGPT recorded the largest proportion of moderate-severity interactions. Notably, Gemini reported the fewest moderate interactions. The inconsistency might be attributed to the diversity in data sources and algorithmic frameworks across platforms.

Among all interaction types, minor ones were the least prevalent, spanning from 1.38% (ChatGPT) to 24.59% (DrugBank). DrugBank recorded the highest proportion of minor interactions, reflecting broader inclusion of less clinically impactful interactions. The relatively low percentage from ChatGPT (1.38%) hints at a possible underrepresentation of minor interactions, possibly due to an algorithmic focus on clinically significant findings.

The differences in the severity classification clearly shows that the algorithmic processing and categorization framework of databases are different from chatbots. The severity estimates of traditional databases can give more consistent severity parameters as their output is based on clinical evidence and literature reviews. On the other hand, chatbots use LLMs and their result can vary based on the sources they use.

Gemini displayed unusual pattern in severity classification when compared with other resources. It showed a comparatively higher rate of major and lower rate of minor interactions. Such risk interpretation indicates its natural inclination towards cautious risk assessment. Machine learning-enabled risk-sensitive behaviour might be the reason of this inconsistency.

Such variation in the severity grading, especially among standard databases and AI resources, can have meaningful clinical implications. For instance, labelling moderate interaction as major can lead to early discontinuation of a vital medication by the healthcare professional and replacement of the medication with another substitute, which might be less effective in that patient. On the other hand, if a major interaction is interpreted as minor, it can lead to serious ADR. This kind of discrepancy can compromise patient safety and increase healthcare costs.

In this study, accuracy was evaluated using standard diagnostic metrics rather than an aggregated score. Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV were assessed for each resource using Lexicomp as the reference standard.

Copilot and ChatGPT demonstrated elevated sensitivity values (0.96 and 0.98, respectively), reflecting their robust capability in identifying clinically relevant drug interactions. Conversely, both tools demonstrated low specificity (0.22 and 0.10), indicating a higher likelihood of overestimating interactions and generating false-positive alerts. Such a profile-marked by high sensitivity but limited specificity-indicates a cautious approach that favors risk minimization, even if it leads to excessive alerting. A recent study demonstrated that Microsoft Bing AI showcased enhanced performance relative to other assessed tools, including ChatGPT variants and Bard. Notably, Bing AI achieved the highest accuracy and specificity scores for detecting clinically meaningful DDIs [16].

On the other hand, conventional resources like Drugs.com and DrugBank showed relatively higher specificity (0.38 and 0.48), though their sensitivity values were lower (0.84 and 0.70). This pattern could indicate a tendency to under-detect interactions, thereby heightening the risk of overlooking clinically significant DDIs. Failing to detect these interactions can lead to avoidable treatment failures, ADRs, or even hospital admissions—especially among cardio-diabetic patients, who are already considered high-risk.

The observed trends point to a key distinction in performance characteristics between AI-driven platforms and traditional DDI databases. AI-based chatbots exhibit elevated sensitivity, indicating their ability to identify a wide spectrum of possible interactions, which aids in minimizing the risk of missing clinically important DDIs. Yet, this enhanced sensitivity is frequently accompanied by reduced specificity, leading to an abundance of alerts, some of which may lack clinical significance. The surplus of alerts may lead to “alert fatigue,” a condition where healthcare providers become habituated and start disregarding even critical notifications. Conversely, traditional DDI tools typically deliver more precise and evidence-backed alerts due to their higher specificity. Although this method minimizes the likelihood of alert burden, it may compromise sensitivity, leading to the omission of some under-reported but meaningful interactions. The interplay between sensitivity and specificity necessitates thoughtful evaluation in choosing and applying DDI resources in clinical settings.

From a clinical decision-making perspective, both extremes present safety challenges. Over-alerting can desensitize clinicians to meaningful alerts, while under-reporting poses direct risks to patient safety. These observations signify the need to optimize AI algorithms for improved specificity without compromising sensitivity, and for traditional tools to enhance comprehensiveness and detection sensitivity [16].

These results are supported by recent research by Gill et al. (2023), who discovered that because AI-powered methods rely on vast, uncurated datasets, they often overpredict DDIs [34].

The Fleiss' kappa coefficient, which gauges agreement beyond chance, was used to evaluate the inter-rater reliability of severity categorizations across the resources under study. For major interactions, the Fleiss' kappa coefficient was 0.15, suggesting that the resources were somewhat in agreement. This points to a significant discrepancy in how various databases and AI systems identify and categorize encounters as major. This diversity may result in varying clinical decision-making depending on the reference source utilized, since major interactions might have substantial clinical implications.

The kappa coefficient for moderate interactions was 0.35, which indicates fair agreement. Although this level of agreement is better than major interactions, it still shows discrepancies in how moderate DDIs are categorized. Moderate interactions typically require dose adjustments or monitoring, and discrepancies among resources may impact clinical judgment regarding necessary precautions [35].

Minor interactions exhibited the lowest agreement, with a kappa coefficient of 0.10 and a p-value of 0.12, suggesting no statistically significant agreement. The lack of consensus in classifying minor interactions indicates that these are more subjectively interpreted among different databases and AI tools. Since minor interactions are less clinically significant, their inconsistency may not have severe consequences, but it does reflect the underlying differences in database methodologies.

The overall agreement among all severity levels was fair (kappa = 0.28, p<0.001), reinforcing the observation that while some consistency exists, the discrepancies remain substantial. These findings highlight the necessity for standardization in the classification of drug interactions across different resources.

Among the electronic databases, the highest agreement was observed between Drugs.com and DrugBank (κ = 0.68), indicating substantial concordance in identifying DDIs. This suggests that these two databases share a relatively comprehensive and consistent dataset for evaluating interactions. Conversely, Lexicomp and Drugs.com (κ = 0.52) and Lexicomp and DrugBank (κ = 0.61) exhibited moderate agreement, signifying variations in their underlying datasets or interaction classification criteria. Notably, the mean Kappa for databases was 0.51, indicating moderate agreement overall.

The agreement between databases and chatbots varied significantly, demonstrating discrepancies in how DDIs are interpreted by AI-driven models versus structured databases. The highest chatbot agreement with a database was Gemini with DrugBank (κ = 0.71), suggesting that this chatbot might rely on a dataset similar to DrugBank or apply an algorithm that aligns closely with it. ChatGPT and Lexicomp (κ = 0.32) and Copilot with Drugs.com (κ = 0.37) showed lower agreement levels, indicating inconsistencies in identifying or classifying interactions. The mean agreement between databases and chatbots was moderate but showed high variation, with some chatbot-database pairs nearing fair agreement levels.

AI chatbots demonstrated varied levels of agreement with each other, reflecting differences in their training data and algorithms. Copilot and Gemini (κ = 0.65) exhibited the highest inter-chatbot agreement, implying similarities in their data sources or processing mechanisms. ChatGPT and Copilot (κ = 0.56) showed moderate agreement, while ChatGPT and Gemini (κ = 0.33) had the lowest agreement, indicating diverse methodologies in DDI identification.

Moderate overall agreement (κ = 0.51) suggests variability in DDI identification across different platforms. Compared to chatbots, structured databases typically agree more, suggesting that AI-driven tools may still have consistency issues. When chatbots use similar algorithms or data sources, they show greater agreement with one another. Potential areas for improvement in AI-enabled DDI evaluation are highlighted by the reduced chatbot-database agreement, which increases the possibility that AI models may interpret interactions differently or rely on different reference sources.

The low agreement on major and minor classifications (κ = 0.15 and 0.10, respectively) further points out the potential for misaligned clinical decisions depending on the resource used. For example, a physician relying on Gemini might classify an interaction as major and avoid a therapy, whereas another using DrugBank may proceed with the same regimen, assuming lower risk. Such variation calls for harmonized severity classification frameworks across drug interaction platforms, and reinforces the need for human oversight when incorporating AI tools into clinical workflows.

CONCLUSION

This study identified notable differences in the scope, completeness, accuracy, and severity classification of DDIs between chatbots and traditional DI databases. While AI tools offered high sensitivity and data completeness, they lacked specificity and consistency in severity ratings, raising concerns about over-alerting. Traditional databases were more balanced but risked under-reporting clinically relevant interactions. As such, chatbots should be used for secondary screening or cross-validation rather than as a primary source for clinical decision-making. We recommend that initial DDI evaluations be conducted using validated and clinically trusted databases such as Lexicomp or Drugs.com. In cases involving complex pharmacotherapy or unclear interaction mechanisms, AI tools may be employed to explore additional dimensions, such as mechanism, patient-specific risk factors, or potential management strategies. Importantly, all AI-generated outputs should be reviewed and interpreted under the supervision of qualified clinical pharmacists or prescribers to ensure clinical appropriateness and patient safety. Looking ahead, the integration of curated reference databases with generative AI models may yield robust hybrid systems that harness the strengths of both approaches-offering improved accuracy, depth, and clinical utility in DDI management.

To enhance clinical decision-making, a hybrid human–AI framework is recommended, combining the strengths of AI and curated resources. The study also emphasizes the need for regulatory oversight to standardize validation protocols and DDI severity classification across platforms. Establishing globally accepted frameworks and pursuing real-world clinical validation and explainable AI approaches will be essential for the safe and effective integration of AI into pharmacovigilance.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors sincerely express their gratitude to the president, the vice president-academic affairs, the vice president-research and postgraduate studies and acting dean of RAKCOP, and the chairperson of the department of clinical pharmacy and pharmacology at RAKMHSU, Ras Al Khaimah, United Arab Emirates. Their invaluable support, guidance, and encouragement have been instrumental in the successful completion of this work.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Aftab Alam: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing-original draft. Anukriti Saran: Data curation, Visualization. Radhika Joshi: Formal analysis, Data curation. Sathvik B. Sridhar: Methodology, Writing-Review and Editing, Validation, Supervision. Swapnil Sharma: Conceptualization, Writing-review and editing, Validation, Supervision, Project administration. Sarvesh Paliwal: Validation.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Corrigendum to: facing the challenge of polypharmacy when prescribing for older people with cardiovascular disease. A review by the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on cardiovascular pharmacotherapy. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2023;9(3):291. doi: 10.1093/ehjcvp/pvad013, PMID 36786239.

World Health Organization. Hypertension. In: Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023 Mar 16. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hypertension. [Last accessed on 10 Feb 2025].

Soomro MH, Jabbar A. Diabetes etiopathology classification, diagnosis and epidemiology. In: Shera AS, Jawad F, editors. BIDE’s diabetes desk book. 1st ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2024. p. 19-42. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-443-22106-4.00022-X.

Wang Z, Yang T, Fu H. Prevalence of diabetes and hypertension and their interaction effects on cardio cerebrovascular diseases: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2021 Jun 25;21(1):1224. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11122-y, PMID 34172039, PMCID PMC8229421.

Tatsumi Y, Ohkubo T. Hypertension with diabetes mellitus: significance from an epidemiological perspective for Japanese. Hypertens Res. 2017 Sep;40(9):795-806. doi: 10.1038/hr.2017.67, PMID 28701739.

Lati MS, David NG, Kinuthia RN. The predictors of potential drug-drug interactions among diabetic hypertensive adult outpatients in a Kenyan referral hospital. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2020 Nov 2;12(12):63-7. doi: 10.22159/ijpps.2020v12i12.38810.

Khodadadeh M. Exploring strategies for designing drug interaction clinical decision support systems: a qualitative study. Minneapolis: Capella University; 2020.

Scheife RT, Hines LE, Boyce RD, Chung SP, Momper JD, Sommer CD. Consensus recommendations for systematic evaluation of drug-drug interaction evidence for clinical decision support. Drug Saf. 2015 Feb;38(2):197-206. doi: 10.1007/s40264-014-0262-8, PMID 25556085, PMCID PMC4624322.

Sumayli AA, Daghriry AI, Sharahili MA, Alanazi AA, Alanazi AA, Alharbi IF. An in-depth examination of drug-drug interaction databases: enhancing patient safety through advanced predictive models and artificial intelligence techniques. Journal of Medical and Life Science. 2024 Dec 16;6(4):553-65. doi: 10.21608/jmals.2024.410645.

Munsaka M, Liu M, Xing Y, Yang H. Leveraging machine learning natural language processing and deep learning in drug safety and pharmacovigilance. In: Ghahramani Z, editor. Data science AI and machine learning in drug development. 1st ed. New York: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2022 Oct 3. p. 193-229. doi: 10.1201/9781003150886-9.

Mutha RE, Bagul VS, Tade RS, Vinchurkar K. An overview of artificial intelligence (AI) in drug delivery and development. In: Vinchurkar K, editor. AI innovations in drug delivery and pharmaceutical sciences; advancing therapy through technology. Singapore: Bentham Science Publishers; 2024 Nov 18. p. 1-27. doi: 10.2174/9789815305753124010004.

Belagodu Sridhar S, Karattuthodi MS, Parakkal SA. Role of artificial intelligence in clinical and hospital pharmacy. In: Bhupathyraaj M, editor. Application of artificial intelligence in neurological disorders. Singapore: Springer Nature; 2024 Jul 1. p. 229-59. doi: 10.1007/978-981-97-2577-9_12.

TS, T CT, Marpaka S, KS. Aspects of utilization and limitations of artificial intelligence in drug safety. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2021 Aug;14(8):34-9. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2021.v14i8.41979.

Radha Krishnan RP, Hung EH, Ashford M, Edillo CE, Gardner C, Hatrick HB. Evaluating the capability of ChatGPT in predicting drug-drug interactions: real-world evidence using hospitalized patient data. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2024 Dec;90(12):3361-6. doi: 10.1111/bcp.16275, PMID 39359001.

Shamim MA, Shamim MA, Arora P, Dwivedi P. Artificial intelligence and big data for pharmacovigilance and patient safety. Journal of Medicine Surgery and Public Health. 2024 Aug 1;3:100139. doi: 10.1016/j.glmedi.2024.100139.

Al Ashwal FY, Zawiah M, Gharaibeh L, Abu Farha R, Bitar AN. Evaluating the sensitivity specificity and accuracy of ChatGPT-3.5, ChatGPT-4, bing AI, and bard against conventional drug-drug interactions clinical tools. Drug Healthc Patient Saf. 2023 Dec 31;15:137-47. doi: 10.2147/DHPS.S425858, PMID 37750052.

Sulaiman DM, Shaba SS, Almufty HB, Sulaiman AM, Merza MA. Screening the drug-drug interactions between antimicrobials and other prescribed medications using google bard and Lexicomp® Online™ database. Cureus. 2023 Sep 9;15(9):e44961. doi: 10.7759/cureus.44961, PMID 37692178, PMCID PMC10492649.

Aksoyalp ZS, Erdogan BR. Comparative evaluation of artificial intelligence and drug interaction tools: a perspective with the example of clopidogrel. Ankara Ecz Fak Derg. 2024;48(3):22. doi: 10.33483/jfpau.1460173.

Rambaran KA, Huynh HA, Zhang Z, Robles J. The Gap in electronic drug information resources: a systematic review. Cureus. 2018 Jun 22;10(6):e2860. doi: 10.7759/cureus.2860, PMID 30148013, PMCID PMC6107040.

Shariff A, Belagodu Sridhar S, Abdullah Basha NF, Bin Taleth Alshemeil SS, Ahmed Aljallaf Alzaabi NA 4th. Assessing the consistency of drug-drug interaction-related information across various drug information resources. Cureus. 2021 Mar 8;13(3):e13766. doi: 10.7759/cureus.13766, PMID 33842142, PMCID PMC8025801.

Shareef J, Sridhar SB, Bhupathyraaj M, Shariff A, Thomas S, Salim Karattuthodi M. Assessment of the scope completeness and consistency of various drug information resources related to COVID-19 medications in pregnancy and lactation. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2023 Apr 27;23(1):296. doi: 10.1186/s12884-023-05609-2, PMID 37106456, PMCID PMC10134615.

Liu X, Hatton RC, Zhu Y, Hincapie Castillo JM, Bussing R, Barnicoat M. Consistency of psychotropic drug-drug interactions listed in drug monographs. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2017 Aug 23;57(6):698-703.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2017.07.008, PMID 28844584.

Marcath LA, Xi J, Hoylman EK, Kidwell KM, Kraft SL, Hertz DL. Comparison of nine tools for screening drug-drug interactions of oral oncolytics. J Oncol Pract. 2018 Jun;14(6):e368-74. doi: 10.1200/JOP.18.00086, PMID 29787332, PMCID PMC9797246.

Abhisek PA, Pradhan SS. Possible drug-drug interactions of hydroxychloroquine with concomitant medications in prophylaxis and treatment of COVID-19: multiple standard software-based assessment. J Clin Diagn Res. 2020 Dec 1;14(12):OC01-4. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2020/45273.14392.

Beckett RD, Stump CD, Dyer MA. Evaluation of drug information resources for drug-ethanol and drug-tobacco interactions. J Med Libr Assoc. 2019 Jan;107(1):62-71. doi: 10.5195/jmla.2019.549, PMID 30598650, PMCID PMC6300238.

Patel RI, Beckett RD. Evaluation of resources for analyzing drug interactions. J Med Libr Assoc. 2016 Oct;104(4):290-5. doi: 10.3163/1536-5050.104.4.007, PMID 27822150, PMCID PMC5079490.

Alkhalid ZN, Birand N. Determination and comparison of potential drug-drug interactions using three different databases in northern Cyprus community pharmacies. Niger J Clin Pract. 2022 Dec;25(12):2005-9. doi: 10.4103/njcp.njcp_448_22, PMID 36537458.

Pehlivanli A, Eren Sadioglu R, Aktar M, Eyupoglu S, Sengul S, Keven K. Potential drug-drug interactions of immunosuppressants in kidney transplant recipients: comparison of drug interaction resources. Int J Clin Pharm. 2022 Jun;44(3):651-62. doi: 10.1007/s11096-022-01385-9, PMID 35235113.

Bossaer JB, Eskens D, Gardner A. Sensitivity and specificity of drug interaction databases to detect interactions with recently approved oral antineoplastics. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2022 Jan;28(1):82-6. doi: 10.1177/1078155220984244, PMID 33435823.

Juhi A, Pipil N, Santra S, Mondal S, Behera JK, Mondal H. The capability of ChatGPT in predicting and explaining common drug-drug interactions. Cureus. 2023 Mar 17;15(3):e36272. doi: 10.7759/cureus.36272, PMID 37073184, PMCID PMC10105894.

Askr H, Elgeldawi E, Aboul Ella H, Elshaier YA, Gomaa MM, Hassanien AE. Deep learning in drug discovery: an integrative review and future challenges. Artif Intell Rev. 2023;56(7):5975-6037. doi: 10.1007/s10462-022-10306-1, PMID 36415536, PMCID PMC9669545.

Liu XH, Lu ZH, Wang T, Liu F. Large language models facilitating modern molecular biology and novel drug development. Front Pharmacol. 2024 Dec 24;15:1458739. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2024.1458739, PMID 39776586, PMCID PMC11703923.

Naik D, Naik I, Naik N. Imperfectly perfect AI chatbots: limitations of generative AI, large language models and large multimodal models. In: Naik N, Jenkins P, Prajapat S, Grace P, editors. Contributions presented at the international conference on computing communication cybersecurity and AI, July 3-4, 2024, London, UK. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland; 2024. p. 43-66. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-74443-3_3.

Gill J, Moullet M, Martinsson A, Miljkovic F, Williamson B, Arends RH. Evaluating the performance of machine learning regression models for pharmacokinetic drug-drug interactions. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 2023 Jan;12(1):122-34. doi: 10.1002/psp4.12884, PMID 36382697, PMCID PMC9835131.

Xiong G, Yang Z, Yi J, Wang N, Wang L, Zhu H. DDInter: an online drug-drug interaction database towards improving clinical decision making and patient safety. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022 Jan 7;50(D1):D1200-7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab880, PMID 34634800, PMCID PMC8728114.