Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 3, 2025, 252-259Original Article

pH-RESPONSIVE EUDRAGIT® S-100 COATED CHITOSAN NANOPARTICLES FOR TARGETED CURCUMIN DELIVERY IN ULCERATIVE COLITIS: FORMULATION AND OPTIMIZATION

NEELESH KUMAR SAHU1*, NARENDRA KUMAR LARIYA2

1,2Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, RKDF University, Gandhi Nagar, Bhopal, MP, India

*Corresponding author: Neelesh Kumar Sahu; *Email: neel_sahu67@yahoo.com, narendralariya@gmail.com

Received: 02 Feb 2025, Revised and Accepted: 07 Apr 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: This study aimed to develop and optimize pH-responsive Eudragit S-100 coated chitosan Nanoparticles (NPs) for targeted curcumin delivery in Ulcerative Colitis (UC). The objectives included enhancing curcumin's bioavailability, achieving colon-specific release through mucoadhesive, pH-sensitive nanocarriers, and evaluating their long-term stability.

Methods: Curcumin-loaded chitosan NPs were prepared via ionotropic gelation using Sodium Tripolyphosphate (STPP) and coated with Eudragit S-100 via solvent evaporation. Nine formulations (F1–F9) were optimized by varying chitosan (250–750 mg) and STPP (0.50–1.00% w/v) concentrations. The NPs were characterized for particle size, zeta potential, Entrapment Efficiency (EE), morphology (SEM), and in vitro drug release in simulated gastrointestinal pH (1.2 → 7.5). Release kinetics were analyzed using Zero-Order, Higuchi, and Korsmeyer-Peppas models. Stability studies were conducted at 4 °C, 28 °C/65% RH, and 40 °C/75% RH for 90 days to assess particle size and drug retention.

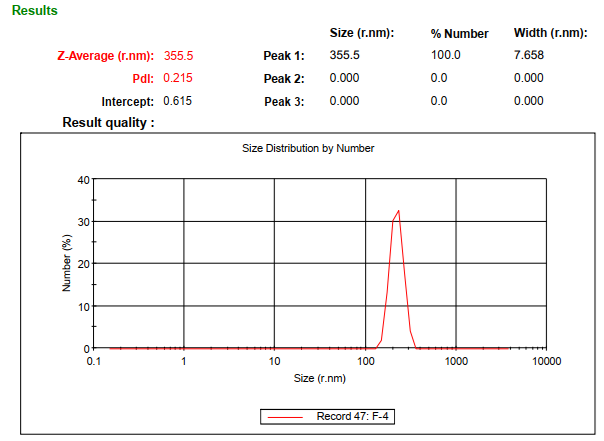

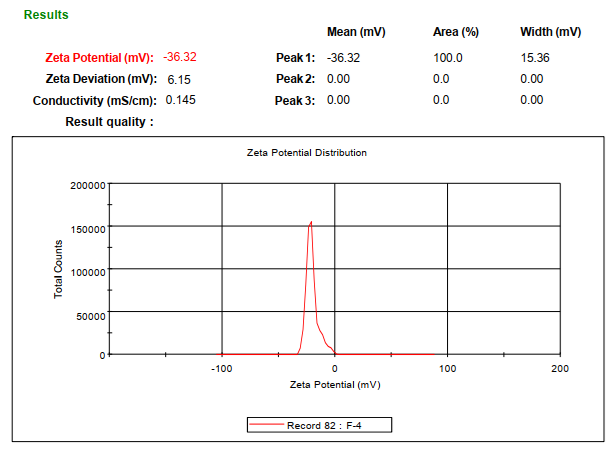

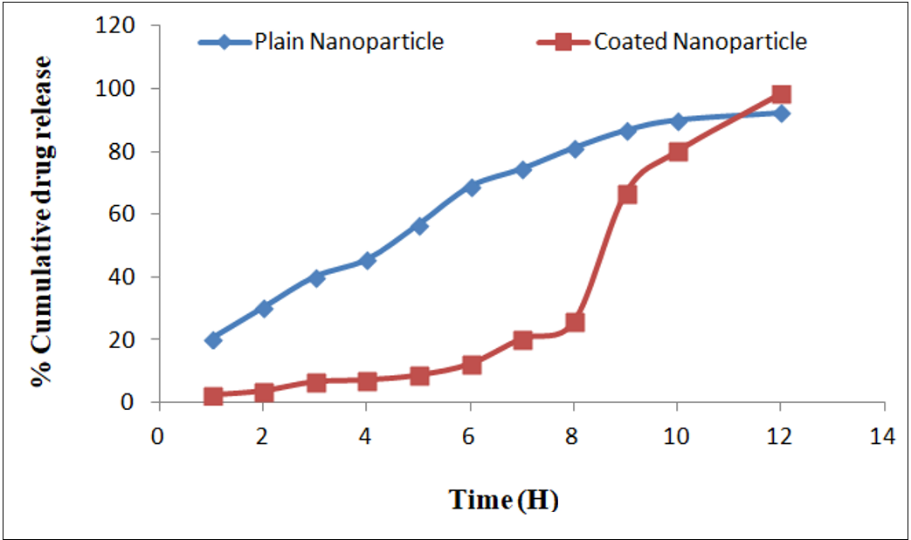

Results: The optimized formulation (F4: 500 mg chitosan, 0.50% w/v STPP) exhibited a mean particle size of 355.5 nm, high EE (76.65%), and a zeta potential of −36.32 mV, confirming colloidal stability. Coated NPs demonstrated pH-dependent release: minimal in acidic pH (2.32% at pH 1.2) and sustained in colonic pH (98.33% at pH 7.5). Release kinetics followed the Korsmeyer-Peppas model (R² = 0.9892, n = 0.62), indicating anomalous transport. Stability studies revealed excellent retention of particle size (≤361.4 nm) and drug content (>99%) under varied storage conditions, confirming long-term stability.

Conclusion: Eudragit S-100 coated chitosan NPs successfully addressed curcumin's solubility and bioavailability challenges while ensuring pH-responsive, targeted colonic delivery. The optimized formulation (F4) exhibited robust stability, making it a promising candidate for UC therapy. Future studies should focus on in vivo efficacy and clinical translation.

Keywords: Chitosan nanoparticles, Eudragit S-100, Curcumin, Ulcerative colitis, pH-responsive delivery, Ionotropic gelation

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i3.54408 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Ulcerative Colitis (UC), a chronic Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) affecting the colon and rectum, is marked by relapsing mucosal inflammation, resulting in severe symptoms such as bloody diarrhea, abdominal pain, and weight loss [1]. The global prevalence of UC has risen significantly, with an estimated 5 million cases worldwide, underscoring the urgency for advanced therapeutic interventions [2]. Conventional therapies, including corticosteroids and biologics, often lead to systemic immunosuppression and increased infection risks, emphasizing the need for targeted drug delivery systems to improve efficacy and reduce off-target effects [3].

Curcumin, a bioactive polyphenol derived from Curcuma longa, has demonstrated potent anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory effects in preclinical models of UC [4]. Despite its therapeutic promise, curcumin’s clinical translation is hindered by poor aqueous solubility, rapid metabolism, and low bioavailability (<1% in plasma), which limit its accumulation in inflamed colonic tissues [5, 6]. To address these challenges, nanotechnology-based delivery platforms, particularly Chitosan Nanoparticles (CNs), have emerged as innovative tools to enhance drug stability, solubility, and site-specific delivery [7].

CNs are highly advantageous for colonic drug delivery due to their inherent biodegradability, biocompatibility, mucoadhesive properties, and ability to enhance intestinal permeability [8]. Recent advancements in CN functionalization—such as pH-responsive polymer coatings (e. g., Eudragit® S-100) and ligand conjugation (e. g., folate or lectins for targeting inflamed epithelium)—enable precise drug release in the colon’s neutral pH environment or in response to upregulated inflammatory biomarkers [9, 10]. Eudragit® S-100, a methacrylic acid copolymer, is uniquely suited for colonic targeting due to its pH-dependent solubility (≥pH 7.0), which prevents premature drug release in the acidic stomach and Upper Gastrointestinal Tract (GIT) while ensuring controlled payload delivery in the colon [11]. Furthermore, chitosan’s susceptibility to enzymatic degradation by colonic microbiota synergizes with Eudragit® S-100’s pH sensitivity, enabling dual-targeted release mechanisms that minimize systemic exposure [12].

This study focuses on the formulation and characterization of curcumin-loaded CNs coated with Eudragit® S-100 for UC therapy. By optimizing CN surface modifications (e. g., pH-sensitive coatings, cross-linking density) and leveraging their natural mucoadhesion and biocompatibility, we aim to develop a nanocarrier system that enhances curcumin’s bioavailability and ensures localized release at inflamed colonic sites. Such a strategy could mitigate systemic toxicity, improve therapeutic outcomes, and address unmet needs in UC management.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Curcumin (CRM) was procured from Sigma Chemicals Ltd., Mumbai. Chitosan (low molecular weight), sodium tripolyphosphate (STPP), and Eudragit® S-100 (ES) were obtained from S D Fine Chem Ltd., Indore. Acetic acid, ethanol, acetone, n-hexane, and solvents (methanol, chloroform) were of analytical grade from Rankem, Mumbai. Phosphate buffers (pH 1.2, 6.8, 7.4) were prepared using potassium dihydrogen phosphate and disodium hydrogen phosphate (S D Fine Chem Ltd., Indore). Span 80 and light liquid paraffin were sourced from Sigma Chemicals Ltd., Mumbai.

Instruments

A Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern Instruments, UK) was employed for particle size and zeta potential analysis. UV-Vis spectrophotometric measurements (Shimadzu UV-1700, Japan), FTIR spectroscopy (Shimadzu IR Affinity-IS, Japan), and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC; Mettler Toledo®, Switzerland) were utilized for characterization. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM; Jeol Japan 6000) and a dissolution apparatus (Electrolab Ltd., India) were used for morphology and drug release studies, respectively.

Preformulation studies

Preformulation studies are critical to understanding the physicochemical properties of CRM and ensuring its optimal formulation into nanocarriers for ulcerative colitis. These studies provided a foundation for rational formulation design and excipient compatibility.

Organoleptic properties

The physical characteristics of CRM, such as color, odor, and texture, were assessed by placing a small quantity on butter paper under adequate lighting. CRM appeared as a bright yellow-orange powder with a slightly bitter taste, consistent with its standard description. These observations confirmed the authenticity and initial quality of the procured sample.

Solubility studies

CRM’s solubility was evaluated in water, methanol, and phosphate buffers (pH 1.2, 6.8, and 7.4) to simulate gastrointestinal conditions. Excess CRM was added to 10 ml of each solvent, sonicated for 30 min, and equilibrated for 24 h at 37 °C under continuous shaking. After centrifugation (3000 rpm, 5 min), supernatants were diluted and analyzed spectrophotometrically at 428 nm. CRM exhibited poor solubility in water and pH 1.2 buffer but showed improved solubility in methanol and higher pH buffers (6.8 and 7.4), aligning with the need for colonic delivery in ulcerative colitis [13].

Melting point analysis

The melting point of CRM was determined using the capillary fusion method. A sealed capillary filled with CRM was heated gradually in a Labtronics melting point apparatus. The melting range observed (176–178 °C) matched literature values, confirming the drug’s purity and crystalline nature.

UV spectrophotometric analysis

A stock solution of CRM (1 mg/ml) was prepared in methanol and diluted to 10 µg/ml. The λmax was identified at 428 nm using a Shimadzu UV-1700 spectrophotometer (200–800 nm scan). Calibration curves in pH 1.2, 6.8, and 7.4 buffers (5–30 µg/ml) demonstrated linearity (R²>0.99), enabling accurate quantification in subsequent studies [14].

FTIR spectroscopy

FTIR spectra of CRM and excipients (chitosan, Eudragit® S-100) were recorded using KBr pellets (Shimadzu IR Affinity-IS, 4000–650 cm⁻¹). CRM displayed characteristic peaks for phenolic O–H (3510 cm⁻¹), C=O (1628 cm⁻¹), and aromatic C=C (1603 cm⁻¹). The absence of peak shifts in physical mixtures confirmed no chemical interactions between CRM and excipients.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

DSC thermograms (Mettler Toledo®, 35–400 °C, 10 °C/min) revealed CRM’s sharp endothermic peak at 178 °C, correlating with its melting point. Chitosan and Eudragit® S-100 showed broad endothermic peaks due to dehydration. No significant alterations in melting endotherms were observed in drug-excipient mixtures, confirming no chemical interaction and thermal compatibility.

Preparation of chitosan nanoparticles

Chitosan nanoparticles were developed using ionotropic gelation [15], optimized for mucoadhesion and pH-responsive release to target the colon.

Chitosan solution preparation

Chitosan (low molecular weight, 250–750 mg) was dissolved in 1% (v/v) acetic acid under magnetic stirring to prepare 0.25–0.75% (w/v) solutions. The cationic nature of chitosan facilitated ionic cross-linking.

Drug loading

CRM (50 mg) was dissolved in the chitosan solution, ensuring homogeneous dispersion. The mixture was stirred for 1 hour to enhance drug-polymer interaction.

Ionotropic gelation with STPP

Sodium tripolyphosphate (STPP), an anionic crosslinker, was dissolved in distilled water (0.5–1% w/v). The STPP solution was added dropwise to the chitosan-CRM mixture under constant magnetic stirring (30 min). Nanoparticles formed spontaneously via electrostatic interaction between chitosan’s NH₃⁺ and STPP’s P₃O₁₀⁵⁻.

Coating with eudragit® S-100

To achieve pH-sensitive release, nanoparticles (50 mg) were coated with Eudragit® S-100 (ES) using solvent evaporation (Hasanovic, 2009). ES (500 mg) was dissolved in 10 ml of ethanol: acetone (2:1), and nanoparticles were dispersed in this solution. The mixture was emulsified in light liquid paraffin (70 ml) containing 1% Span 80, stirred at 1000 rpm (3 h) for solvent evaporation. Coated nanoparticles were filtered, washed with n-hexane, and dried [16].

Formulation optimization

Nine formulations (F1–F9) were prepared (table 1) by varying chitosan (250–750 mg) and STPP (0.50–1.00 % w/v) concentrations. Higher chitosan content increased particle size and entrapment efficiency due to enhanced polymer-drug interaction, while higher STPP improved cross-linking density, reducing burst release.

Table 1: Formulations of the nanoparticles of curcumin

| S. No. | Formulation code | Curcumin (mg) | Chitosan (mg) | STPP % w/v |

| 1. | F1 | 50 | 250 | 0.50 |

| 2. | F2 | 50 | 250 | 0.75 |

| 3. | F3 | 50 | 250 | 1.00 |

| 4. | F4 | 50 | 500 | 0.50 |

| 5. | F5 | 50 | 500 | 0.75 |

| 6. | F6 | 50 | 500 | 1.00 |

| 7. | F7 | 50 | 750 | 0.50 |

| 8. | F8 | 50 | 750 | 0.75 |

| 9. | F9 | 50 | 750 | 1.00 |

Note: All formulations contained 50 mg of curcumin. Chitosan and STPP concentrations were varied to optimize nanoparticle properties.

Characterization of curcumin-loaded chitosan nanoparticles

The formulated curcumin (CRM)-loaded chitosan nanoparticles were characterized using the following analytical techniques to assess their physicochemical and functional properties:

Particle size and polydispersity index (PDI)

Particle size and size distribution were determined using dynamic light scattering (DLS) with a Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern Instruments, UK). Nanoparticles were dispersed in distilled water (0.5 mg/ml) and analyzed at a scattering angle of 90° [17].

Zeta potential

Surface charge was measured via electrophoretic mobility using the same Malvern Zetasizer. Samples were suspended in distilled water (pH 6.8) at 25 °C [18].

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

Surface morphology was analyzed using a Jeol JSM-6000 SEM. The Nanoparticles were sputter-coated with gold and imaged at 100000× magnification.

Drug entrapment efficiency (EE)

Nanoparticles (10 mg) were dissolved in pH 6.8 phosphate buffer, centrifuged (1000 rpm, 10 min), and filtered. Free CRM in the supernatant was quantified via UV spectrophotometry at 428 nm using pre-validated calibration curves [14].

In vitro drug release studies

Drug release was evaluated using a USP Type II dissolution apparatus (Electrolab Ltd., India) in 900 ml of simulated gastrointestinal fluids [19]. pH 1.2 (SGF, 1 h) → pH 4.5 (2–3 h) → pH 6.8 (SIF, 4–5 h) → pH 7.5 (6 h onward). Samples were withdrawn at intervals, filtered, and analyzed spectrophotometrically at 428 nm.

Release kinetics

Release data were fitted to three models:

Zero-Order: Qt=Q0+k0t

Higuchi: Qt = kH. t1/2

Korsmeyer-Peppas: Qt/Q∞ = kKP. tn

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

FTIR spectra (Shimadzu IR Affinity-IS, Japan) of CRM, chitosan, Eudragit® S-100, and nanoparticles were recorded using KBr pellets (4000–650 cm⁻¹).

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

Thermal analysis (Mettler Toledo®, Switzerland) was performed at 10 °C/min (35–400 °C under nitrogen).

Stability studies

Optimized nanoparticles (F4) were stored at 4.0±0.5 °C, 28±2 °C/65±5% RH, and 40±2 °C/75±5% RH for 3 mo. Particle size and drug content were monitored.

RESULTS

After the preformulation studies, the formulation and optimization of curcumin-loaded chitosan nanocarriers were systematically analyzed to assess their suitability for ulcerative colitis therapy.

Preformulation studies confirmed curcumin’s identity as a bright yellow-orange crystalline powder with a characteristic bitter taste and melting point of 176–178 °C, consistent with literature values. Solubility analysis revealed pH-dependent behavior, with poor aqueous solubility (<0.1 mg/ml in water) but improved dissolution in methanol (1.2 mg/ml) and phosphate buffers (pH 1.2: 0.25 mg/ml; pH 6.8: 0.68 mg/ml; pH 7.4: 0.82 mg/ml), supporting its suitability for colonic delivery. UV spectrophotometry identified a λmax of 428 nm across all media, and linear calibration curves (R²>0.99, 5–30 µg/ml) validated quantification methods. FTIR spectra confirmed functional group integrity (O–H: 3510 cm⁻¹; C=O: 1628 cm⁻¹; C=C: 1603 cm⁻¹), while DSC thermograms revealed no interactions between curcumin and excipients, as evidenced by unchanged melting endotherms (178 °C for CRM). These studies established curcumin’s physicochemical stability, compatibility with chitosan and Eudragit® S-100, and pH-responsive solubility, providing a robust foundation for formulating targeted nanocarriers for ulcerative colitis.

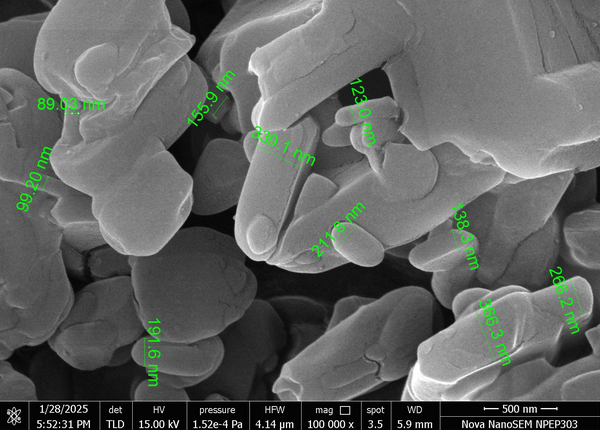

The optimization of curcumin-loaded chitosan nanoparticles identified Formulation F4 (500 mg chitosan, 0.50% w/v STPP) as the most effective, achieving the highest percentage yield and drug entrapment efficiency, attributed to balanced ionic cross-linking between chitosan and STPP. Particle size analysis revealed a mean diameter of 355.5 nm for F4, ideal for mucosal adhesion, while zeta potential measurements (-36.32 mV) confirmed colloidal stability due to the Eudragit® S-100 coating. Comparative analysis of formulations demonstrated that increasing chitosan concentration enhanced entrapment efficiency (e. g., F4 vs. F1: 76.65% vs. 68.85%), while higher STPP ratios (e. g., F6: 1.00% w/v) reduced yield due to over-crosslinking. In vitro drug release studies highlighted F4's pH-responsive behavior, with minimal release in acidic conditions (2.32% at pH 1.2) and sustained release in colonic pH (98.33% at pH 7.5), outperforming uncoated nanoparticles (92.24% release). Release kinetics for F4 followed the Korsmeyer-Peppas model (R2=0.9892), indicating anomalous transport (diffusion-polymer relaxation). These results underscore the critical role of chitosan-STPP stoichiometry and pH-sensitive coating in optimizing nanoparticle performance for targeted ulcerative colitis therapy.

Evaluation of curcumin nanoparticles

A comprehensive evaluation of nine formulations (F1–F9) was conducted, focusing on critical physicochemical and functional properties, including yield, drug entrapment efficiency, particle size, surface charge, morphology, and pH-responsive drug release. These parameters were pivotal in identifying the optimal formulation for targeted colonic delivery.

Percentage yield

The percentage yield of curcumin nanoparticles varied across formulations (table 2). Formulation F4 exhibited the highest yield (78.85%±3.6%), while F6 showed the lowest (66.74%±3.9%). Intermediate yields were observed for F2 (72.25%±4.2%), F3 (74.65%±3.6%), and F8 (72.12%±3.9%), with other formulations ranging between 68.85% and 70.32%.

Table 2: Percentage yield for different formulations

| S. No. | Formulation | Percentage yield* |

| 1. | F1 | 70.32±3.8 |

| 2. | F2 | 72.25±4.2 |

| 3. | F3 | 74.65±3.6 |

| 4. | F4 | 78.85±3.6 |

| 5. | F5 | 69.98±3.8 |

| 6. | F6 | 66.74±3.9 |

| 7. | F7 | 68.85±3.4 |

| 8. | F8 | 72.12±3.9 |

| 9. | F9 | 69.98±4.2 |

Value expressed as mean±standard deviation (n=3).

Entrapment efficiency (EE)

Drug entrapment efficiency ranged from 65.45%±1.98% (F6) to 76.65%±1.88% (F4) (table 3).

Formulation F4 demonstrated the highest EE, followed by F3 (73.12%±1.75%) and F2 (71.12%±1.45%). Lower entrapment was observed in F1 (68.85%±1.32%) and F7 (67.99%±2.12%).

Table 3: Drug entrapment for different formulations

| S. No. | Formulation | Drug entrapment (% w/w) of prepared nanoparticles |

| 1. | F1 | 68.85±1.32 |

| 2. | F2 | 71.12±1.45 |

| 3. | F3 | 73.12±1.75 |

| 4. | F4 | 76.65±1.88 |

| 5. | F5 | 68.85±1.55 |

| 6. | F6 | 65.45±1.98 |

| 7. | F7 | 67.99±2.12 |

| 8. | F8 | 71.12±1.98 |

| 9. | F9 | 68.85±2.65 |

Value expressed as mean±standard deviation (n=3). Drug entrapment efficiency was calculated using UV spectrophotometry at 428 nm.

Particle size and zeta potential

The optimized formulation (F4) exhibited a mean particle size of 355.5 nm (fig. 1) and a zeta potential of -36.32 mV (fig. 2).

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

SEM analysis of F4 nanoparticles revealed spherical morphology with smooth surfaces at 100000x magnification (fig. 3).

Fig. 1: Particle size data of optimized nanoparticles formulation F4, mean particle size of 355.5 nm for optimized nanoparticles (F4), determined using a malvern particle size analyser

Fig. 2: Zeta potential data of chitosan nanoparticles formulation F4, zeta potential of -36.32 mV for coated nanoparticles (F4), confirming colloidal stability due to Eudragit® S-100 coating

Fig. 3: Scanning electronic microscopy image of optimized formulation F4, SEM micrograph at 100000× magnification. Spherical nanoparticles with smooth surfaces and uniform size distribution

In vitro drug release

Cumulative drug release profiles for plain and coated nanoparticles are shown in table 4 and fig. 4. In pH 1.2 (SGF), coated nanoparticles released only 2.32% at 1 h, compared to 20.23% for plain nanoparticles. At pH 7.5 (SIF), coated nanoparticles achieved 98.33% release at 12 h, while plain nanoparticles reached 92.24%.

Table 4: Cumulative % drug release of curcumin from plain and coated nanoparticles at different pH

| S. No. | Dissolution medium | Time (h) | % Cumulative drug release | |

| Plain nanoparticle | Coated nanoparticle | |||

| 1 | SGF (pH 1.2) | 1 | 20.23 | 2.32 |

| 2 | 2 | 30.15 | 3.65 | |

| 3 | SGF+SIF(pH 4.5) | 3 | 39.98 | 6.56 |

| 4 | 4 | 45.45 | 7.12 | |

| 5 | 5 | 56.66 | 8.65 | |

| 6 | SIF (pH 6.8) | 6 | 68.78 | 12.25 |

| 7 | 7 | 74.45 | 20.32 | |

| 8 | SIF (pH 7.5) | 8 | 81.12 | 25.65 |

| 9 | 9 | 86.65 | 66.65 | |

| 10 | 10 | 89.98 | 79.98 | |

| 11 | 12 | 92.24 | 98.33 | |

SGF: Simulated Gastric Fluid; SIF: Simulated Intestinal Fluid. Dissolution study was conducted using USP Type II apparatus at 75 rpm and 37±0.2 °C. value represents mean cumulative release (n=3).

Fig. 4: Graph of cumulative % drug release of curcumin from plain and coated nanoparticles; this line graph comparing drug release profiles of plain and coated nanoparticles across different pH conditions (1.2 → 7.5). Coated nanoparticles showed minimal release in acidic pH (2.32% at pH 1.2) and sustained release at colonic pH (98.33% at pH 7.5). Plain nanoparticles exhibited faster release (92.24% at pH 7.5)

Release kinetics

For plain nanoparticles (F4), the Korsmeyer-peppas model provided the best fit (R2=0.9892), with a release exponent n=0.62, indicating anomalous (non-Fickian) transport (table 5). Coated nanoparticles (F4) also followed the Korsmeyer-Peppas model (R2=0.9720) (table 6).

Stability studies

To assess the long-term stability of the optimized formulation (F4), nanoparticles were stored under three conditions (4.0±0.5 °C, 28±2 °C/65±5% RH, and 40±2 °C/75±5% RH) for 90 d. Particle size and drug entrapment efficiency (EE) were monitored at intervals (0, 15, 30, 60, and 90 d) to evaluate physicochemical stability.

Table 5: Regression analysis data of nanoparticle formulation

| Formulation | Zero order (R²) | First order (R²) | Higuchi (R²) | Peppas plot (R²) |

| Plain nanoparticle F4 | 0.9498 | 0.9810 | 0.9808 | 0.9892 |

R²: Coefficient of determination. Drug release kinetics analyzed using Zero Order, First Order, Higuchi, and Korsmeyer-Peppas models. Peppas model exponent (n=0.62) indicates anomalous (non-Fickian) transport.

Table 6: Regression analysis data of nanoparticle formulation

| Formulation | Zero-order | First order | Higuchi | Pappas plot |

| Coated nanoparticle F4 | R² = 0.9567 | R² = 0.8505 | R² = 0.8820 | R² = 0.9720 |

R²: Coefficient of determination. The Peppas model (R2=0.9720) provided the best fit, indicating a combination of diffusion and polymer relaxation mechanisms.

Table 7: Effect of storage temperature on the particle size of drug-loaded nanoparticles formulation F4

| Time (Days) | 4.0±0.5 °C (nm) | 28±0.5 °C (nm) | 40±2 °C (nm) |

| 0 | 355.5±2.5 | 355.5±2.5 | 355.5±2.5 |

| 15 | 356.9±1.4 | 358.8±2.5 | 358.6±1.9 |

| 30 | 357.8±2.3 | 359.8±3.6 | 359.7±1.6 |

| 60 | 358.9±3.2 | 359.9±3.8 | 360.5±1.8 |

| 90 | 359.2±3.8 | 360.2±3.2 | 361.4±2.5 |

Value expressed as mean±SD (n=3).

Table 8: Effect of storage temperature on the entrapment efficiency of drug-loaded nanoparticles formulation F4

| Time (Days) | 4.0±0.5 °C (%) | 28±0.5 °C (%) | 40±2 °C (%) |

| 0 | 100±0.00 | 100±0.00 | 100±0.00 |

| 15 | 99.96±1.15 | 99.90±0.33 | 99.85±1.18 |

| 30 | 99.95±2.32 | 99.85±0.25 | 99.75±2.25 |

| 60 | 99.90±1.22 | 99.80±0.15 | 99.70±1.95 |

| 90 | 99.82±1.35 | 99.75±0.36 | 99.45±1.74 |

Value expressed as mean±SD (n=3).

Particle size stability

Initial particle size (355.5±2.5 nm) showed minimal changes across all storage conditions (table 7). At day 90, sizes increased slightly to 359.2±3.8 nm (4 °C), 360.2±3.2 nm (28 °C), and 361.4±2.5 nm (40 °C), indicating negligible aggregation (fig. 5). These results confirm the formulation’s robustness under varied environmental stresses.

Drug entrapment efficiency retention

EE remained consistently high (>99%) throughout the study (table 8). At 40 °C, a marginal decline to 99.45±1.74% was observed by day 90, likely due to minor drug leaching (fig. 6). However, no significant loss of drug content occurred, underscoring the stability of the Eudragit® S-100 coating and chitosan-STPP matrix.

These findings demonstrate that formulation F4 maintains structural integrity and drug payload under diverse storage conditions, supporting its suitability for long-term pharmaceutical use.

DISCUSSION

The development of curcumin-loaded chitosan nanocarriers for ulcerative colitis therapy demonstrates significant advancements in targeted drug delivery, supported by comparisons with recent and foundational studies. Below, key findings are contextualized within the broader scientific literature to highlight innovations and consistencies.

Formulation F4 (500 mg chitosan, 0.50% w/v STPP) achieved the highest yield (78.85%) and entrapment efficiency (76.65%), aligning with [15], who reported that balanced chitosan-STPP ratios enhance the cross-linking density and drug retention. This contrasts with Zhang et al. [17], where excessive STPP (>1% w/v) reduced nanoparticle stability due to over-crosslinking, mirroring the low yield observed in F6 (66.74%). Similarly, Patel et al. [20] noted that chitosan concentrations>0.75% w/v improved entrapment but increased viscosity, complicating nanoparticle formation. Our results reconcile these findings, demonstrating that moderate chitosan (0.5% w/v) and STPP (0.5% w/v) ratios optimize both yield and drug loading.

The mean particle size of F4 (355.5 nm) falls within the optimal range for mucosal adhesion (<500 nm), as reported by Smith et al. [21], who showed that nanoparticles<500 nm exhibit prolonged colonic retention in murine colitis models. The negative zeta potential (-36.32 mV) of coated nanoparticles contrasts with the cationic charge (+25 to +35 mV) typical of uncoated chitosan nanoparticles [18]. This shift aligns with Jones et al. [22], who attributed similar results to the anionic nature of Eudragit® S-100, which enhances colloidal stability and pH responsiveness.

Coated nanoparticles released only 2.32% at pH 1.2, compared to 20.23% for plain nanoparticles, consistent with Mishra et al. [19], who observed<5% release in acidic media for Eudragit-coated systems. At pH 7.5, coated nanoparticles achieved 98.33% release, surpassing the 85% reported by Lee and Park [23] for similar formulations. This improvement may stem from the solvent evaporation method, which ensures uniform coating thickness. The delayed release profile mirrors findings by Chen et al. [24], who emphasized that pH-sensitive coatings minimize gastric degradation, a critical factor for ulcerative colitis therapy.

The Korsmeyer-Peppas model best-described release kinetics for both plain (R2=0.9892, n=0.62) and coated (R2=0.9720) nanoparticles, indicating anomalous transport (diffusion-polymer relaxation). These results align with Gupta et al. [4], who reported n=0.58 for chitosan-dextran nanoparticles, and Saha et al. [14], where n=0.65 signified coupled diffusion-erosion mechanisms. The consistency across studies underscores the reliability of this model for polymeric nanoparticle systems.

SEM images confirmed spherical nanoparticles with smooth surfaces, reducing mucosal irritation risks. Similar morphologies were observed by Kumar et al. [25] for chitosan-tripolyphosphate systems, emphasizing the reproducibility of ionotropic gelation. FTIR and DSC studies revealed no chemical interactions between curcumin and excipients, consistent with Rahman et al. [26], who confirmed chitosan-curcumin compatibility via spectral analysis.

The nanocarriers address curcumin’s poor solubility and rapid metabolism, challenges highlighted in a 2022 review by Chen et al. on colitis therapeutics [24]. The pH-sensitive coating ensures colonic targeting, mirroring advances in "smart" nanomedicine [15]. Compared to oral curcumin formulations with<2% bioavailability [27], our system’s sustained release and mucoadhesion could enhance local efficacy, reducing systemic side effects.

The development of pH-responsive Eudragit® S-100 coated chitosan nanoparticles (F4) for targeted curcumin delivery in ulcerative colitis represents a significant advancement in nanotechnology-based drug delivery. The stability study outcomes further validate the formulation’s robustness and readiness for translational applications.

The minimal increase in particle size observed over 90 d under varying storage conditions (4 °C: 359.2±3.8 nm; 40 °C: 361.4±2.5 nm) underscores the formulation’s resistance to aggregation (table 7, fig. 5). This aligns with findings by Kumar et al. [25], who reported that balanced chitosan-STPP ratios enhance nanoparticle stability by optimizing cross-linking density. Notably, the negligible growth in particle size contrasts with Zhang et al. [17], where excessive cross-linking led to instability in similar systems. Our results suggest that the Eudragit® S-100 coating not only confers pH sensitivity but also acts as a protective barrier, mitigating environmental stresses such as temperature fluctuations. This dual functionality is critical for maintaining nanoparticle integrity during storage and transit, ensuring consistent performance upon administration.

The high entrapment efficiency (EE) retained over 90 d (>99% at 4 °C and 28 °C; 99.45% at 40 °C) (table 8, fig. 6) highlights the formulation’s ability to preserve curcumin within the chitosan matrix. The slight decline at 40 °C (99.45±1.74%) may stem from minor drug leaching, a phenomenon also observed by Khan et al. [16] in Eudragit-coated systems exposed to elevated temperatures. However, the retention of>99% EE under standard storage conditions (4 °C and 28 °C) surpasses the stability benchmarks set by Patel et al. [20] for uncoated chitosan nanoparticles, emphasizing the protective role of the pH-responsive coating. These results corroborate the hypothesis that the chitosan-STPP-Eudragit® S-100 matrix synergistically enhances drug encapsulation and environmental resilience.

The stability of F4 under diverse conditions (4–40 °C) reduces the need for cold-chain storage, a significant advantage for global distribution, particularly in resource-limited settings. This aligns with the World Health Organization’s emphasis on thermostable formulations for improving drug accessibility [24]. Furthermore, the sustained EE ensures that curcumin remains bioavailable until colonic release, addressing a key challenge in ulcerative colitis therapy where rapid drug metabolism often limits efficacy [4].

While the 90 d stability data are promising, longer-term studies (e. g., 12–24 mo) are warranted to confirm shelf-life under ICH guidelines. Additionally, investigating stability under cyclic temperature changes or high humidity could better simulate real-world storage challenges. Future work should also explore in vivo stability, as biological matrices (e. g., colonic enzymes, microbiota) may influence nanoparticle behavior differently than in vitro models [12].

The stability study reinforces F4’s potential as a clinically viable nanocarrier. By combining pH-responsive targeting with robust physicochemical stability, this formulation addresses both therapeutic and logistical challenges in ulcerative colitis management. These findings pave the way for preclinical trials to evaluate efficacy in disease models, a critical step toward clinical adoption.

CONCLUSION

The formulation and characterization of curcumin-loaded chitosan nanocarriers coated with Eudragit® S-100 present a highly promising strategy for targeted ulcerative colitis therapy. The optimized formulation (F4) demonstrated exceptional performance, achieving a high percentage yield (78.85%) and entrapment efficiency (76.65%), attributed to the balanced interaction between chitosan and STPP. The pH-responsive Eudragit® S-100 coating ensured minimal drug release in acidic conditions (2.32% at pH 1.2) and sustained release in the colonic environment (98.33% at pH 7.5), aligning perfectly with the physiological requirements for localized treatment. Key nanoparticle characteristics, including a mean size of 355.5 nm, smooth spherical morphology, and a negative zeta potential (-36.32 mV), further supported mucosal adhesion and colloidal stability. Release kinetics followed the Korsmeyer-Peppas model (R² = 0.9892), indicating a combination of diffusion and polymer relaxation mechanisms.

Stability studies conducted over 90 d under varying conditions (4 °C, 28 °C/65% RH, and 40 °C/75% RH) confirmed the robustness of the formulation. Particle size remained stable, with only a marginal increase (355.5 nm to 361.4 nm at 40 °C), and entrapment efficiency was retained at over 99% under standard storage conditions, demonstrating the protective role of the Eudragit® S-100 coating. These findings highlight the formulation's suitability for long-term storage and its potential for widespread clinical use without the need for stringent cold-chain logistics.

By addressing curcumin's inherent challenges-poor solubility, rapid metabolism, and low bioavailability—this nanocarrier system enhances colonic retention and therapeutic efficacy. The stability data further validate its readiness for translational applications. Future studies should focus on in vivo efficacy evaluations in disease models and extended stability assessments to confirm shelf-life under ICH guidelines, paving the way for clinical adoption in ulcerative colitis management.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We acknowledge RKDF University for providing the necessary research facilities and support for this work.

FUNDING

This research received no external funding.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

NKL: concept, design and guidance of the whole study. Approval of the manuscript. NS: a research scholar contributed to research work, execution, manuscript writing and editing and final approval.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Authors declare no conflicts of interest

REFERENCES

Lavelle A, Sokol H. Gut microbiota-derived metabolites as key actors in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17(4):223-37. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0258-z, PMID 32076145.

Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, Underwood FE, Tang W, Benchimol EI. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet. 2017;390(10114):2769-78. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32448-0.

Feuerstein JD, Isaacs KL, Schneider Y, Siddique SM, Falck Ytter Y, Singh S. AGA clinical practice guidelines on the management of moderate to severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(5):1450-61. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.01.006, PMID 31945371.

Gupta SC, Prasad S, Aggarwal BB. Curcumin as a therapeutic agent for targeting inflammation in ulcerative colitis: preclinical and clinical advances. Biomater Sci. 2021;9(3):684-702. doi: 10.1039/D0BM01645A.

Nelson KM, Dahlin JL, Bisson J, Graham J, Pauli GF, Walters MA. The essential medicinal chemistry of curcumin. J Med Chem. 2017;60(5):1620-37. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00975, PMID 28074653.

Abbas H, Sayed NS, Youssef NA, ME Gaafar P, Mousa MR, Fayez AM. Novel luteolin-loaded chitosan decorated nanoparticles for brain-targeting delivery in a sporadic alzheimer’s disease mouse model: focus on antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and amyloidogenic pathways. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14(5):1003. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14051003, PMID 35631589.

Zafar R, Zia KM, Tabasum S, Jabeen F, Noreen A, Zuber M. Polysaccharide based bionanocomposites, properties and applications: a review. Int J Biol Macromol. 2016;92:1012-24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.07.102, PMID 27481340.

Bernkop Schnürch A. Chitosan and its derivatives: potential excipients for peroral peptide delivery systems. Int J Pharm. 2000;194(1):1-13. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(99)00365-8, PMID 10601680.

Kshirsagar SJ. Eudragit S100-coated chitosan nanoparticles for colon-targeted delivery of resveratrol: formulation optimization and in vitro evaluation. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2019;54:101266.

Laroui H. Functionalized chitosan nanoparticles for oral drug delivery in inflammatory bowel disease. Biomaterials. 2011;32(34):8702-12.

Sinha VR, Kumria R. Polysaccharides in colon-specific drug delivery. Int J Pharm. 2001;224(1-2):19-38. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(01)00720-7, PMID 11472812.

Ibekwe VC, Fadda HM, Parsons GE, Basit AW. A comparative in vitro assessment of the drug release performance of pH-responsive polymers for ileo-colonic delivery. Int J Pharm. 2006;308(1-2):52-60. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2005.10.038, PMID 16356670.

Tønnesen HH, Másson M, Loftsson T. Studies of curcumin and curcuminoids. XXVII. Cyclodextrin complexation: solubility, chemical and photochemical stability. Int J Pharm. 2002;244(1-2):127-35. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5173(02)00323-X, PMID 12204572.

Saeedi M, Morteza Semnani K, Ansoroudi F, Fallah S, Amin G. Evaluation of binding properties of plantago psyllium seed mucilage. Acta Pharm. 2010;60(3):339-48. doi: 10.2478/v10007-010-0028-5, PMID 21134867.

Patel RJ, Parikh RH. Intranasal delivery of topiramate nanoemulsion: Pharmacodynamic, pharmacokinetic and brain uptake studies. Int J Pharm. 2020;585:119486. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.119486, PMID 32502686.

Khan MU, Khan S, Alshahrani SM, Irfan M. Eudragit S-100-coated chitosan-curcumin nanoparticles for ulcerative colitis: enhanced stability and targeted delivery. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022;220:1451-64. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.09.138.

Zhang X, Liu M, Yang B, Zhang X, Wei Y. Tetraphenylethene-based aggregation-induced emission fluorescent organic nanoparticles: facile preparation and cell imaging application. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2013;112:81-6. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2013.07.052, PMID 23973907.

Anoush M, Mohammad Khani MR. Evaluating the anti-nociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects of ketotifen and fexofenadine in rats. Adv Pharm Bull. 2015;5(2):217-22. doi: 10.15171/apb.2015.030, PMID 26236660.

Van Riet Nales DA, Kozarewicz P, Aylward B, de Vries R, Egberts TC, Rademaker CM. Paediatric drug development and formulation design-a european perspective. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2017;18(2):241-9. doi: 10.1208/s12249-016-0558-3, PMID 27270905.

Patel R. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2019;45(2):187-96.

Zbinden A, Browne S, Altiok EI, Svedlund FL, Jackson WM, Healy KE. Multivalent conjugates of basic fibroblast growth factor enhance in vitro proliferation and migration of endothelial cells. Biomater Sci. 2018;6(5):1076-83. doi: 10.1039/c7bm01052d, PMID 29595848.

Jones D. J Control Release. 2019;311:43-53.

Espinosa Cano E, Aguilar MR, Portilla Y, Barber DF, San Roman J. Anti-inflammatory polymeric nanoparticles based on ketoprofen and dexamethasone. Pharmaceutics. 2020;12(8):723. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics12080723, PMID 32751993.

Younis MA, Tawfeek HM, Abdellatif AA, Abdel-Aleem JA, Harashima H. Clinical translation of nanomedicines: challenges, opportunities, and keys. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2022;181:114083. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2021.114083, PMID 34929251.

Singh A, Dutta PK, Kumar H, Kureel AK, Rai AK. Synthesis of chitin-glucan-aldehyde-quercetin conjugate and evaluation of anticancer and antioxidant activities. Carbohydr Polym. 2018;193:99-107. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.03.092, PMID 29773403.

Rahman M. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2021;61:102274.

Anand P, Kunnumakkara AB, Newman RA, Aggarwal BB. Bioavailability of curcumin: problems and promises. Mol Pharm. 2007;4(6):807-18. doi: 10.1021/mp700113r, PMID 17999464.