Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 5, 2025, 1-8Review Article

FAST-TRACKING DRUG APPROVALS: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW OF THE US FDA'S EXPEDITED REGULATORY PATHWAYS

PREETHAM NS1, SARATH MUNDRA2, NEIL MESSIAH LOPES1, AKHILESH DUBEY1*

1Nitte (Deemed to be University), NGSM Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Department of Pharmaceutics, Mangaluru, India. 2Astrazeneca, Global Regulatory Affairs, Bangalore, India

*Corresponding author: Akhilesh Dubey; *Email: akhilesh@nitte.edu.in

Received: 28 Mar 2025, Revised and Accepted: 17 Jun 2025

ABSTRACT

The current review explores the utilization and impact of the United States Food and Drug Administration’s (US-FDA) accelerated drug approval pathways over the past decade (2014–2024). Specifically, it evaluates five key programs: Orphan Drug Designation, Fast Track, Breakthrough Therapy, Priority Review, and Accelerated Approval. The primary aim is to assess how these expedited pathways influence drug development timelines and overall approval success rates. A comprehensive literature search was conducted using databases such as PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. The search yielded 200 articles, of which 110 met the inclusion criteria. From these, 25 key studies were selected for detailed analysis. The findings indicate that Priority Review accounted for the highest number of drug approvals (367 approvals, 55%), followed by Orphan Drug Designation (279 approvals, 42%) and Fast Track (215 approvals, 32%). Breakthrough Therapy and Accelerated Approval contributed to 124 (19%) and 103 (15%) approvals, respectively. These programs have significantly accelerated the availability of essential treatments, particularly in oncology and rare diseases. However, challenges persist. The reliance on surrogate endpoints raises concerns about long-term efficacy, and the need for rigorous post-marketing surveillance remains critical to ensure safety and therapeutic value. In conclusion, the increasing adoption of these accelerated pathways underscores their growing importance in meeting urgent medical needs. While they offer promising benefits in terms of faster access to life-saving therapies, a balanced approach that ensures thorough evaluation and long-term monitoring is essential for sustained public health outcomes.

Keywords: FDA, Expedited approval, Priority review, Orphan drug designation, Fast track, Breakthrough therapy, Accelerated approval

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i5.54440 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

To ensure the safety, efficacy, and quality of drugs and biologics available to the public, the pharmaceutical industry operates under stringent regulatory oversight. Traditionally, the approval of a new drug requires extensive and rigorous clinical trials, followed by a thorough review by regulatory authorities-a process that can span several years. However, in response to the urgent need for timely access to treatments for serious and life-threatening conditions, regulatory agencies worldwide have introduced expedited pathways for drug approval. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) oversees drug development and regulation. To accelerate the availability of promising therapies for conditions with limited or no existing treatment options, the FDA offers several special designation programs.

Currently, the FDA employs five primary programs to facilitate expedited drug development and review, such as orphan drug designation (ODD), fast track (FT), accelerated approval (AA), priority review (PR), breakthrough therapy designation (BTD)

These programs are designed to support innovation while maintaining the highest standards of safety and effectiveness.

While the fundamental requirements for drug approval-centered on safety and efficacy-have remained unchanged since 1962, expedited approval programs have introduced greater flexibility into the process. These programs modify traditional regulatory pathways by allowing alternative clinical trial designs and broader criteria for demonstrating a drug’s effectiveness. This flexibility enables more diverse methods for evaluating therapeutic benefits, especially in areas of high unmet medical need. Despite their intended benefits, the use of these accelerated pathways has sparked considerable debate among scientists, policymakers, and the public. Concerns have been raised about the appropriate use of such programs, with some critics arguing that they may be leveraged more for commercial advantage than for genuine patient benefit. Although these programs are designed to provide quicker access to potentially life-saving treatments for patients with limited options, questions persist about the rigor of the approval process and the long-term safety of these drugs.

One of the most scrutinized programs, AA, has been linked to post-market safety concerns, including adverse effects that were not evident during initial trials. This underscores the need for robust post-marketing surveillance, which, in practice, can sometimes be delayed or insufficient. Critics also argue that expedited approvals do not consistently lead to improved patient outcomes and may contribute to rising drug prices, placing additional burdens on healthcare systems. Given these challenges, it is crucial for pharmaceutical companies seeking to deliver innovative therapies to have a thorough understanding of expedited approval mechanisms.

This project aims to systematically review and analyze existing literature on the FDA’s accelerated drug approval pathways in the United States. It will examine key factors such as approval timelines, post-approval safety and efficacy, and the broader impact of these programs on the drug development process.

Methodology

This systematic review of existing research examines the FDA's accelerated drug approval processes over the last ten years. It seeks to understand how these programs, specifically ODD, FT, BT, PR, and AA, affect the speed of drug development, the regulatory procedures involved, and the final approval rates of new medications.

Data collection and extraction

Data were collected from several electronic databases, including PubMed, and Scopus, and Web of Science, along with Google Scholar, covering publications from 2014 to 2024. Also, the inclusion and exclusion criteria for data selection are given in the following section:

Inclusion criteria

The selected research papers were meticulously reviewed to gather comprehensive insights into several critical aspects of the U. S. FDA’s expedited drug approval programs, particularly the Fast Track Approval (FTA) pathway. The review focused on the historical development and background of these programs, patterns of drug approvals over the past decade (2014–2024), and a comparative analysis of different drug types and their respective approval rates under various expedited pathways. It also included a detailed examination of the timelines associated with each program, from the submission of applications to final approval, and assessed the broader implications of these programs on drug safety and efficacy. The review considered studies published in English between 2014 and 2024, including research articles, systematic reviews, and regulatory reports that specifically addressed the FDA’s expedited pathways and approval durations.

Exclusion criteria

Studies that were irrelevant to the FDA drug approval processes were excluded from the review. Additionally, papers that lacked sufficient methodological detail or did not provide relevant data were not considered. Duplicate studies identified across multiple databases were also removed to avoid redundancy and ensure the integrity of the review.

Study selection

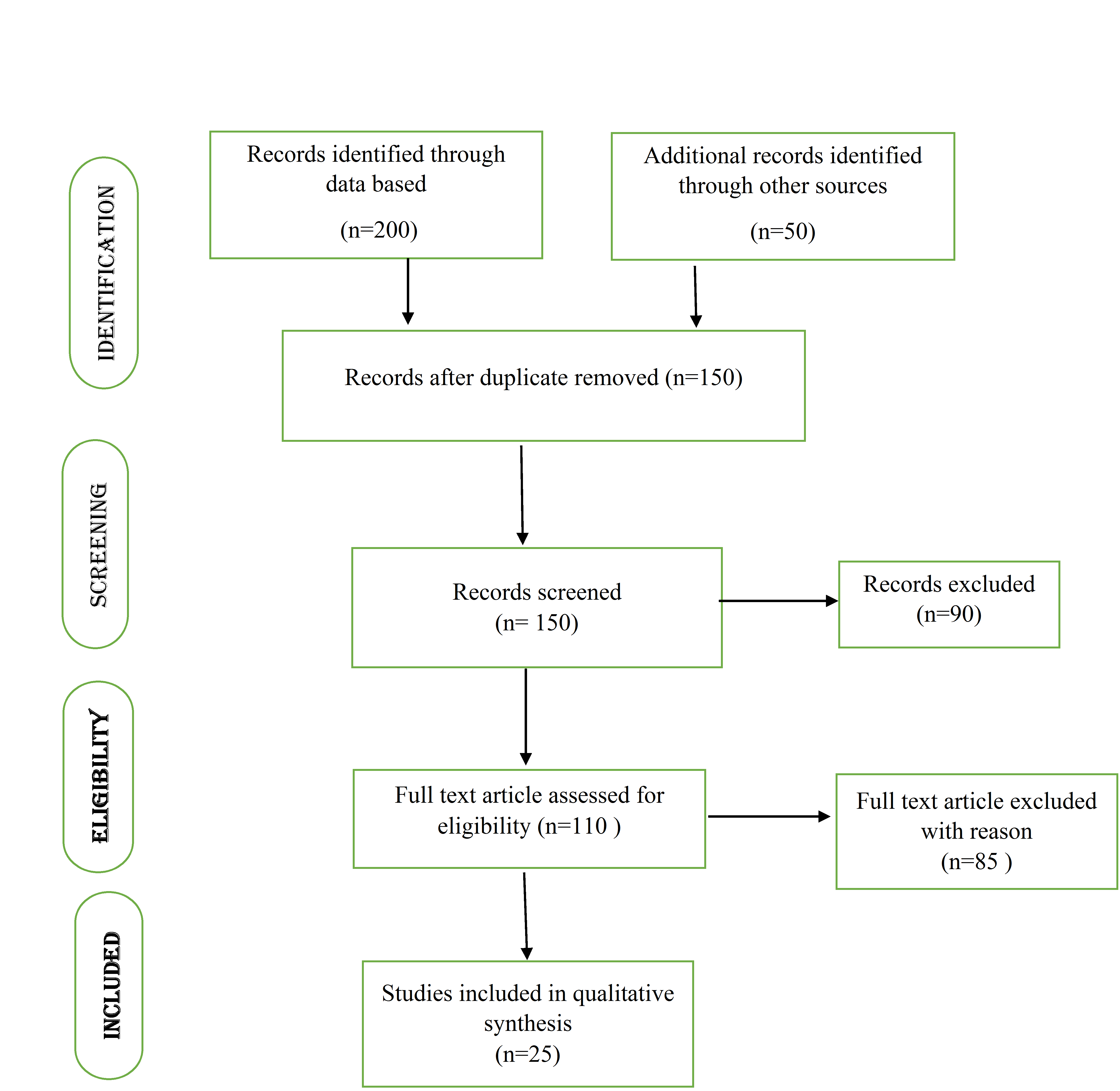

The initial database searches yielded 200 potential articles. Following a review to determine if the articles met the study's requirements, 110 of the original 200 were selected for closer examination. Of these, 25 papers were considered as base papers as shown in Prisma diagram fig. 1 and detailed insights into the specific FDA expedited pathways, including comparative analyses. The PRISMA flowchart outlines the systematic process used to select studies for this review. Initially, 200 articles were identified from databases such as PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science, with an additional 50 sourced manually. After removing duplicates, 150 unique records were screened based on titles and abstracts, resulting in 90 exclusions due to irrelevance. The remaining 110 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, of which 85 were excluded for reasons such as lack of methodological detail or insufficient relevance to FDA expedited pathways. Ultimately, 25 studies meeting all criteria were included in the qualitative synthesis as the core "base papers."

Fig. 1: PRISMA flow diagram of literature selection process

Table 1: FDA drug approval trends

| Year/Category | Number of approvals |

| Total Approvals (2013–2023) | 302 |

| Approvals (2015) | 45 |

| Approvals (2017) | 46 |

| Approvals (2020) | 59 |

| Total Approvals (2014–2020) | 209 |

| Therapeutic Area Distribution (2014–2020) | |

| -Cardiovascular Drugs | 9.09% (of 209) ≈ 19 drugs |

| -Neurological Drugs | 12.91% (of 209) ≈ 27 drugs |

| -Antibiotics | 5.26% (of 209) ≈ 11 drugs |

| -Antivirals | 5.74% (of 209) ≈ 12 drugs |

| -Anticancer Drugs | 11.96% (of 209) ≈ 25 drugs |

| -Biologics | 7.17% (of 209) ≈ 15 drugs |

| Biological Product Approvals (2023) | 17 products |

| -Monoclonal Antibodies (2023) | 12 |

| -Enzymes or Proteins (2023) | 5 |

RESULTS

This research examined the different accelerated drug approval processes used by the U. S. FDA, giving a clearer picture of their timelines, regulatory structures, and how they operate.

Current FDA expedited approval programs

The typical drug approval process in the U. S., overseen by the FDA, is known for its well-defined and stringent steps. It commences with "Discovery and Preclinical research," where a drug's safety and effectiveness are initially tested. This is followed by three phases of clinical trials: Phase 1 focuses on safety with a small group of people, Phase 2 determines the right dosage and continues to assess safety with a larger group, and Phase 3 confirms effectiveness and monitors side effects with a much larger group of participants.

FDA drug approval trends

The observed trends include a general increase in the number of drugs being approved, more frequent use of the FDA's accelerated approval programs, a heightened focus on developing and approving treatments for severe illnesses, such as cancer and rare diseases. In the last ten years, there has beena notable rise in the number of applications for new drugs (NDAs) and biological products (BLAs), resulting in 302 drug approvals. The table 1 illustrated the average number of drug approvals [7].

Over the past decade, FDA approvals for new drugs (NDAs) and biologics (BLAs) have increased, total of 302, with a peak of 59 in 2020. Between 2014 and 2020, 209 drugs were approved across key therapeutic areas: anticancer (11.96%), neurological (12.91%), cardiovascular (9.09%), antibiotics (5.26%), antivirals (5.74%), and biologics (7.17%) [6]. While cancer and neurological drug approvals align with disease burden, areas like antibiotics show underrepresentation despite rising resistance. In 2023, the FDA approved 17 biologics, including 12 monoclonal antibodies, highlighting their growing importance in addressing complex, high-need conditions and advancing therapeutic innovation.

Orphan drug designation (ODD)

The process for developing orphan drugs mirrors the standard drug development pathway, which includes: initial discovery and preclinical testing, followed by Phase 1, Phase 2, and Phase 3 clinical trials, then FDA review, and finally, Phase 4, which involves monitoring the drug's safety and effectiveness after it's been released to the market [7]. The ODD program offers incentives that can substantially reduce the time it takes to develop a drug. While standard drug development usually takes 8 to 12 years, the expedited timelines for orphan drugs can vary depending on the specifics of each drug development project [7]. Orphan drug approvals have considerably increased in recent years. Since 2014, the approval rate has significantly climbed, showing a consistent upward trend [8]. To encourage the development of drugs for rare diseases affecting fewer than 200,000 U. S. patients, a specialized regulatory framework provides incentives. This framework, known as the ODD, aims to address unmet medical needs, as seen with Spinraza for spinal muscular atrophy. Orphan-designated drugs receive regulatory support that eases their development, such as adaptable clinical trials and enhanced FDA collaboration [7]. To simplify their development, drugs with orphan designation benefit from regulatory assistance, including flexible clinical trial designs and improved FDA cooperation [9]. The ODD program has demonstrably succeeded in securing numerous orphan designations and FDA approvals, with over 6,000 designations and 1,000 approvals by 2021. However, a significant gap remains, as only a small percentage (5%) of rare diseases have approved treatments [7].

FastTrack (FT)

To expedite the development and approval of treatments for severe illnesses with unmet medical needs, particularly in response to the 1980s AIDS crisis, the U. S. established the Fast Track Designation in 1988. This process enables pharmaceutical companies to maintain ongoing communication with the FDA after a successful Phase 1 trial, which helps in designing Phase 2 trials that may be sufficient for drug approval [10]. The Fast Track process is characterized by consistent and timely communication between the FDA and drug developers, enabling the phased submission and review of drug applications. The Fast Track designation has had a notable effect, especially in oncology, by accelerating the approval of innovative cancer treatments [7]. In 2017, over a quarter (12 out of 46) of the drugs approved were for cancer, demonstrating the program's effectiveness in addressing critical medical needs [10]. Between 2014 and 2022, roughly one-third of New Drug Approvals (NDAs) utilized this program, demonstrating its increasing significance in drug development [7].

This method seeks to accelerate the availability of treatments to patients, sometimes leading to approvals within 6 to 10 mo, particularly when coupled with PR. This timeline is considerably quicker than the typical 10 to 12 mo, or even longer, required for standard reviews [7]. Some critics contend that the accelerated approval process is overly permissive, as it relies on insufficient data [11]. Even with these criticisms, the FDA has sustained a strong approval rate, granting 41 and 45 approvals in 2014 and 2015, respectively, of which 14 benefited from FTD.

The FTD regulatory structure is designed to quickly provide patients with new therapies that address critical medical needs. This is especially important for drugs that offer substantial improvements over current treatments, such as increased effectiveness or safety [11]. Despite the expedited process, some drugs approved through Fast Track have exhibited significant safety issues after reaching the market. Ocrelizumab, for example, which received FTD in 2017 for multiple sclerosis, is one such case. Despite persisting safety concerns, fast-track designations continue, with 18 out of 46 ND sin 2017 and 12 [12] out of 37 in 2022 [7] receiving this status. Despite the benefits of accelerated access, several drugs approved through the FTD have raised post-marketing safety concerns. Ocrelizumab, approved in 2017 for multiple sclerosis, exemplifies this, with ongoing safety issues surfacing after approval. In 2017, 18 of 46 novel drugs and in 2022, 12 of 37 received FTD, reflecting continued reliance on this pathway. However, a more robust analysis is needed to evaluate how frequently expedited approvals are followed by safety-related withdrawals, black-box warnings, or label modifications. Such insights are critical to assessing whether regulatory flexibility compromises long-term patient safety.

Accelerated approval pathway (AA)

To expedite the availability of promising treatments, the AA Pathway permits the use of surrogate endpoints. These endpoints serve as indicators of likely clinical benefit, offering a faster route to approval compared to traditional methods that rely on direct measurements of survival or disease progression. This expedited review process typically reduces the approval timeline to approximately 6 to 10 mo following NDA submission, in contrast to the standard 10 to 12-month review, thereby facilitating quicker access to therapies for severe or life-threatening illnesses [13]. The approval process mandates standard initial clinical trials, allows for accelerated approval using surrogate endpoints, and crucially, demands post-market studies to verify the drug's real-world clinical effectiveness and long-term safety [13]. However, 6 (13%) were granted accelerated approval, like benznidazole for Chagas disease [22].

Expanding upon previous oncology research, a 2023 study demonstrated that the AA Program successfully reduces the time needed for a drug to achieve standard approval or be withdrawn, contingent upon the initiation of confirmatory trials prior to the accelerated process. Crucially, the study revealed that the likelihood of a drug being withdrawn after approval was similar, regardless of whether it followed the accelerated or traditional approval routes. In 2022, the AA pathway led to the approval of the following NDAs: Elahere, Krazati, Lunsumio, Lytgobi, Tecvayli, and Vonjo. In the 30years since its inception, the FDA has utilized the AA Program to grant approval to 278 medications [7]. While the AA Program was initially designed to quickly bring HIV treatments to market, it has more recently prioritized the approval of cancer medications [13]. Recent accelerated approvals have largely focused on cancer and blood-related conditions, spurred by progress in targeted treatments and well-defined surrogate endpoints within oncology [14].

By the end of 2021, 38% of drugs approved through the AA program (107 medications) were still awaiting traditional approval, dependent on the results of ongoing confirmatory studies. Of those drugs, 77 had been available for less than 3.2 y, which is the current median time for accelerated approvals to convert to traditional approvals, and were therefore excluded from further analysis [15, 7]. The analysis focuses on 30 drugs that have been on the market for more than 3.2 y. Out of these, 22 are meeting their planned timelines. Five are classified as 'dangling' approvals. Three are labeled as 'delinquent,' indicating delays or issues in meeting their milestones. Dangling approval refers to a drug approval that was granted through an accelerated or conditional regulatory pathway, typically based on surrogate endpoints or limited clinical data with the requirement that confirmatory post-marketing studies be conducted. Delinquent approvals refer to drugs granted accelerated or conditional approval by regulatory agencies such as the FDA with a mandatory requirement to complete post-marketing (confirmatory) clinical trials by a specified deadline, but where the sponsor has missed the agreed-upon timelines for these studies without adequate justification [15].

Priority review (PR)

The Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA) in 1992 established the PR process, which speeds up the FDA's evaluation of NDA’s. This system offers a faster review compared to the standard process, while still following the same basic evaluation structure [16]. The Priority Review designation mandates that the FDA complete its review and make a decision on a drug application within 6 mo, significantly faster than the standard 10-month timeframe. This accelerated process applies to both NDA’s and supplemental applications concerning drug effectiveness, all while maintaining the same rigorous safety and efficacy standards [15].

In 2021, PR became the most common accelerated designation, with over two-thirds (68%) of new drug applications receiving this expedited review [15]. Typically, around 55% of new drug applications are granted PR status. In 2020, aducanumab was granted PR to treat Alzheimer’s disease [17]. Additionally, 28 (61%) obtained PR, including dupilumab (atopic dermatitis) and midostaurin (acute myeloid leukemia) [17]. In 2022, 57% of the 37 newly approved drugs, specifically 21 medications, received PR status. The Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) assigns a Priority Review to drugs that show promise in treating serious conditions, and if approved, offer a significant improvement in safety or effectiveness compared to existing treatments, diagnoses, or preventative measures [7, 18]. A Priority Review application triggers an expedited review process by the CDER, aiming for a decision within six months, significantly faster than the standard ten-month review timeline. The drugs that were scheduled for PR in 2022 are Cibinqo, and Elahere, and Elucirem, and Enjaymo, and Kimmtrak, and Lunsumio, and Lytgobi, and Opdualag, and Pluvicto, and Pyrukynd, and Relyvrio, and Spevigo, and Sunlenca, and Tecvayli, and Terlivaz, and Tzield, and Vivjoa,and Vonjo, and Voquezna Triple Pak, and Xenpozyme, along with Ztalmy [19].

Breakthrough therapy (BT)

BTD shares similarities with the Fast Track program, but provides a more comprehensive level of assistance during the drug development process. BTD includes all the benefits of the FT program and adds more in-depth FDA guidance throughout the drug development and review stages, including direct involvement from high-level agency personnel [21].

Cancer drugs that received BTD saw their clinical development time reduced by two to three years on average, compared to cancer drugs without this designation [7, 20]. Breakthrough therapies frequently represent entirely new drug categories, address previously untreatable diseases, utilize cutting-edge mechanisms of action, and encompass innovative drug types like antibody-drug conjugates, gene therapies, and cell therapies [20]. Since its introduction in 2012, the use of BTD has increased significantly, with the number of drug approvals rising from 3 in 2015 to 17 in 2017. The growing number of BTD shows how the seprograms speed up drug development and review, leading to more new drug approvals by the CDER in recent years. In 2022, 35% of the 37 new drug approvals, or 13 drugs, were granted Breakthrough Therapy status [6, 7]. In 2020, the following drugs received BTD for their approved uses: Camzyos, Cibinqo, Enjaymo, Kimmtrak, Lunsumio, Tzield, Krazati, Lytgobi, Spevigo, Pluvicto, Tecvayli, Sunlenca, and Xenpozyme. In 2018, the oral medication fingolimod was approved for the treatment of relapsing multiple sclerosis in children and adolescents older than 10 y [21].

There's been a notable rise in the use of accelerated FDA review pathways lately. In 2018, 37% of the newly approved drugs, specifically 17 medications, received Breakthrough Therapy designation, including ribociclib for breast cancer and niraparib for ovarian cancer [22].

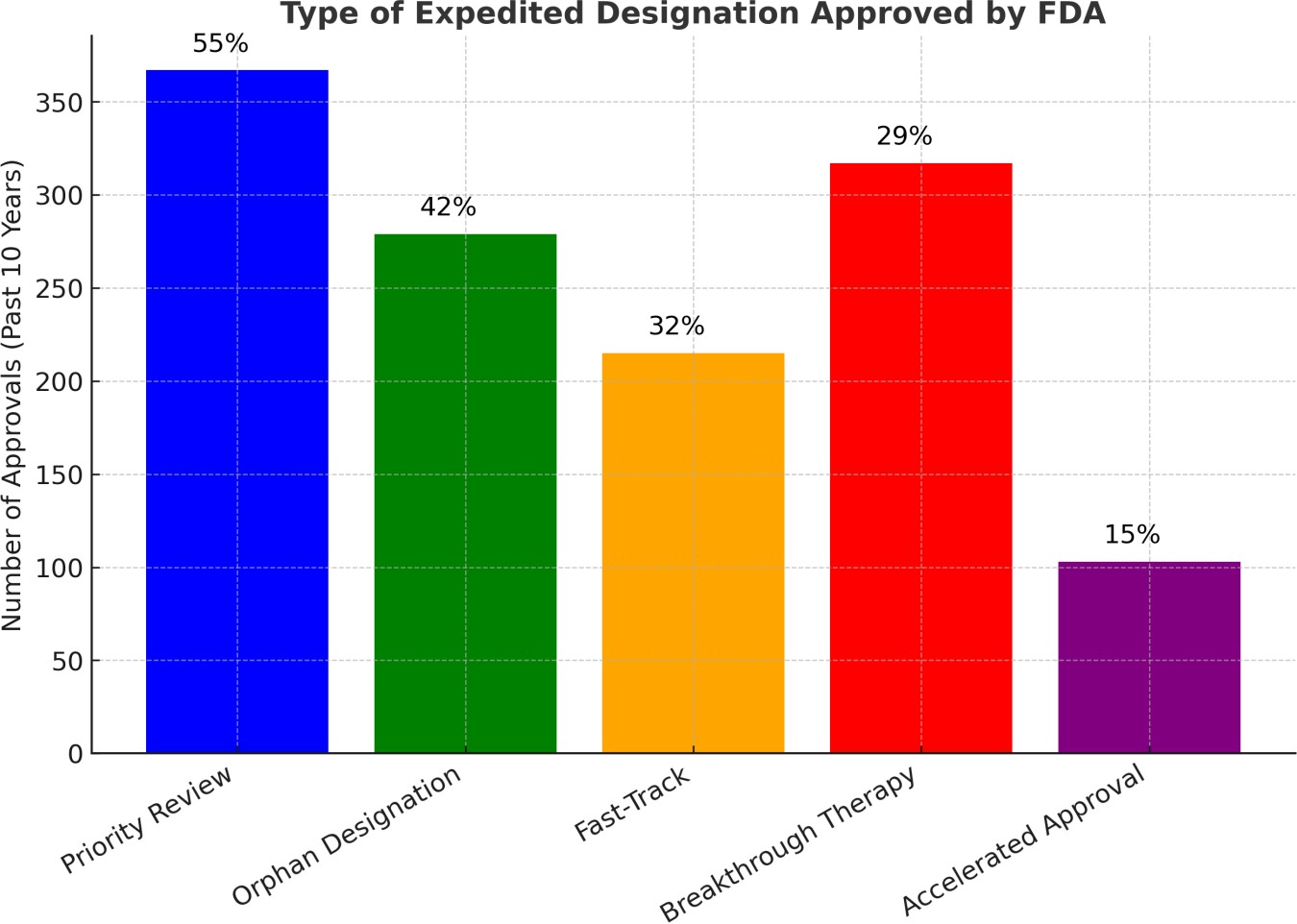

Expedited review status

These expedited review categories can overlap, allowing a single drug to qualify for and benefit from multiple accelerated programs simultaneously (fig. 3) illustrates the breakdown of expedited review designations for FDA-approved drugs from2010to 2019. As an example, in 2019, out of the 48 drugs the FDA approved, 17 received FTD (35%), 13 received BTD (27%), 28 PR (58%), and 9 received AA (19%). PR is the most frequently used expedited review pathway, accounting for over half of all annual drug approvals since 2014, as shown in fig. 2. Over the ten-year period, excluding 2010, the percentage of FDA-approved drugs receiving FTD stayed fairly consistent, averaging around 35%. Following the introduction of the BTD in 2012, there has beena steady increase in the number of drugs receiving it, now accounting for approximately 25% of all approved drugs [23].

Combinations of FDA expedited regulatory pathways

Each expedited review pathway has its own set of requirements and advantages, and the overall impact can change depending on which combination of pathways is applied to a specific drug. The analysis indicates that using a combination of FDA expedited review programs leads to the greatest reduction in both drug development and approval timelines. Studies indicate that when a drug receives a combination of PR, BTD, and AA, it results in the short Est median development time, averaging 1,458 d, and the fastest approval time, averaging 166 d. This combination creates a strong system for significantly speeding up both the drug development and regulatory review processes [22]. Studies show that when a drug is granted PR, FT, BT, and AA designations simultaneously, it results in the quickest median approval time, with drugs being approved in just 145 days.

This suggests that utilizing all eligible expedited review pathways together leads to the most efficient and rapid approval process [21]. In general, using PR, BTD, and AA together seems to be the most efficient method for speeding up both drug development and the approval process [21]. This particular combination of review pathways maximizes efficiency by capitalizing on each pathway's unique advantages, including faster reviews, enhanced support, and the use of surrogate endpoints to demonstrate efficacy. Combining expedited regulatory pathways accelerates drug approvals by streamlining development, reducing delays, and enhancing early regulatory engagement and confidence.

Applying for expedited programs for serious conditions

To have their Investigational New Drug (IND) application considered for any of the FDA's expedited programs, drug developers must submit a formal request and adhere to specific guidelines and criteria set by the FDA. For Fast Track Designation (FTD), companies can request it when they initially submit their IND application, and ideally, no later than their meeting with the FDA before submitting a NDA or Biologics License Application (BLA). FTD requests should include a cover letter and supporting documentation that adequately capture how the drug is intended to treat a serious condition with an unmet medical need, as well as how its therapeutic potential will be evaluated in the planned clinical development program. Furthermore, if a drug developer wants FTD for more than one specific use or condition, they must submit individual requests for each one.

For PR, the FDA independently determines if a drug application qualifies for expedited review when the NDA is submitted, regardless of whether the drug developer has specifically requested it. Each application is evaluated individually. A drug developer can formally request PR by submitting a cover letter explaining how the drug treats a serious condition and providing evidence showing it offers a significant improvement in safety or effectiveness compared to existing treatments. For BTD, drug developers can request it when they initially file their IND application or at any later point. However, this request should only be made when there is compelling early clinical evidence demonstrating the drug's potential. Typically, the necessary clinical evidence for BTD is not available until after the initial human trials are completed. Therefore, a request for BTD is usually submitted as an update to the original IND application. The formal BTD request should include a cover letter that outlines the proposed use of the drug and supporting documents that explain how the drug treats a serious condition and how early clinical data shows it offers a significant advantage over existing treatments. Similar to FTD requests, drug developers must submit individual requests if they are seeking Breakthrough Therapy Designation for multiple intended uses of the drug.

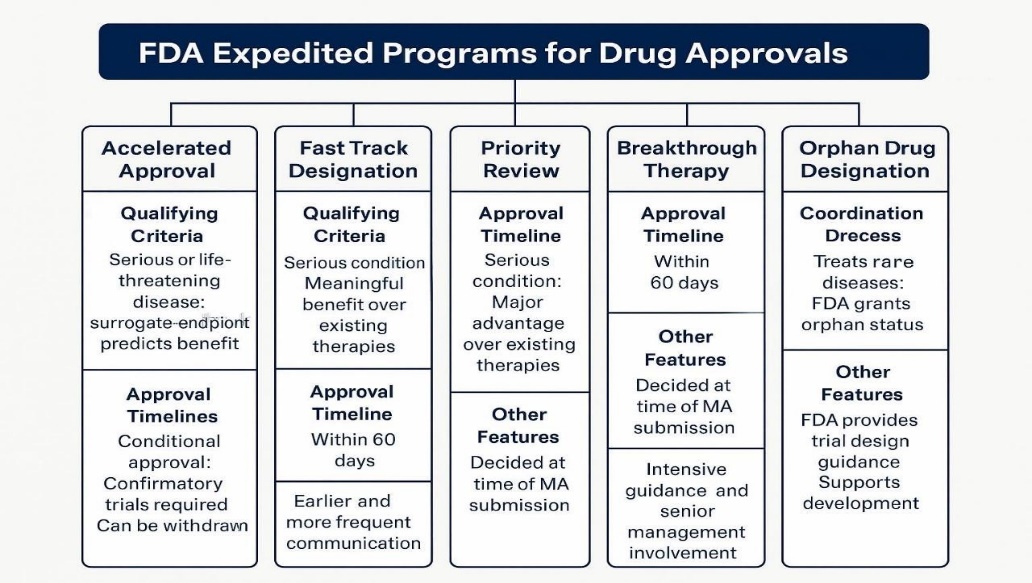

Drug developers who want their drug to receive orphan drug designation must formally apply to the FDA. Even if a drug has already been designated for a specific rare disease, companies seeking the same designation for their version of the drug must submit their own independent data and information to support their application. Receiving orphan drug designation is a distinct process, separate from the steps required to obtain drug approval or licensing. Drugs intended for rare diseases undergo the same strict scientific evaluation for approval and licensing as drugs for more common conditions [24]. The FDA offers four expedited programs FT, BT, AA, and PR, targeting different drug development stages and often combinable for faster approvals. In contrast, the EMA provides fewer options: PRIME (similar to Breakthrough Therapy), Accelerated Assessment, and Conditional Marketing Authorisation, with stricter use and greater emphasis on post-marketing data. Other regulators, like Japan’s PMDA (Sakigake) and Health Canada (NOC/c), also have expedited pathways. The FDA’s flexibility and high regulatory engagement, especially via Breakthrough Therapy, lead to faster timelines than the more conservative EMA. These structural and procedural differences influence global drug approval speed, standards, and evidence requirements. Fig. 2 and table 2 depicted the FDA expedited programs for drug approvals and comparison of US Food and Drug Administration Expedited Programs for Serious Conditions, respectively.

Fig. 2: FDA expedited programs for drug approvals

Table 2: Comparison of US food and Drug Administration expedited programs for serious conditions [24]

| Programs | AA | FTD | PR | BTD | ODD |

| Program type qualifying criteria | Treats serious or life-threatening diseases. | Treats a serious condition. | Treats a serious condition. | Treats serious or life-threatening diseases. | Treatments for rare diseases are a key priority. |

| Provides meaningful benefit over existing therapies. | Offers major advantage over existing therapies. | Offers major advantage over existing therapies. | Preliminary clinical evidence of substantial improvement on clinically significant endpoint over available therapies. | The FDA has authority to grant orphan drug designation to a drug to prevent, diagnose or treat a rare disease or condition. | |

| Surrogate endpoint to predict clinical benefit. | |||||

| Review process | MA submitted when completed; review of MA within 10 mo. | Option for rolling review of MA. | MA submitted when completed; Review of MA within 6 mo | Option for rolling review of MA; can qualify for “expedited review” of MA within 5 mo. | Coordination across the agency and review of FDA form 4035. |

| Timeline for the approval | 10 mo maximum. | Within 60 d. | 6 mo maximum. | Within 60 d. | Within 90 d. |

| Other features | Conditional approval; Confirmatory trials to verify expected clinical benefit. | Earlier, more frequent communication. | Decided at time of MA submission. | Intensive guidance and organizational commitment involving senior managers. | The FDA connects sponsors with the relevant review divisions, which can advise on the design of clinical trials. |

| Can be withdrawn. | Can be withdrawn. | Can be withdrawn. |

DISCUSSION

This research offers a thorough examination of the FDA's accelerated processes for drug applications and approvals, emphasizing their impact on drug development timelines and approval success. In a study by (Riberio et al., 2020) [25] show the data from 2015 to2020, the average annual drug approvals were 45 in 2015, and 46 in 2017. The approval of 59 new drugs by 2020 shows a clear link between the increasing number of NDAs submitted and the growing number of drug approvals annually. The research also examines the increasing utilization of the FDA's accelerated review programs, specifically ODD, FT, BT, PR, and AA. There's been a clear and substantial increase in the use of these expedited designations, indicating a deliberate move to accelerate the availability of innovative therapies for severe and uncommon diseases. For instance, studies (Michaeli et al., 2024) [26]-the transformative effect of the ODD on the development along with approval of drugs for rare diseases. ODD effectively reduces drug development time by offering various incentives, such as tax benefits, research funding, and waived application fees. While the average number of orphan drug approvals was approximately five per year between 2015 and 2020, there were significant spikes in specific years, with 21 approvals in 2015, 9 in 2016, and 18 in 2020 [27]. ODD has experienced significant growth, with 279 drugs receiving approval in the last ten years, representing 42% of all drug approvals during that period. The increase in orphan drug approvals from 22% in 2015 to 54% in 2022 demonstrates the FDA's growing emphasis on addressing rare diseases, where typical market force soften don’t encourage drug development.

Till now FTD has facilitated the approval of 215 drugs over the past ten years, representing 32% of total approvals [7]. As reported by (Franco, 2023) [29]. FDA represents a strategic acceleration between 2014 and 2022, approximately 33% of NDs benefited from FTD, demonstrating its growing significance in modern ODD. The designation notably shortens timelines, with some drugs receiving approval inside 6 to 10 mo likened to the standard 10 to 12 mo. According to (Liberti, 2017)[28], the FT process has faced scrutiny as accelerated approvals have sometimes been linked to later safety concerns, as seen with drugs like Dabigatran and Ezogabine, which were associated with serious adverse effects post-market. This highlights the need for ongoing vigilance even after expedited approval. Notably, 18 out of 46 NDs approved in 2017 received FTD (Liberti, 2017) [28], underscoring that the pathway is particularly valuable for drugs that address serious conditions with unmet medical needs, enabling earlier and more recurrent communication with the FDA and allowing for a rolling review process.

In the past one decade, AA has been granted to 103 drugs, comprising 15% of total approvals. Established in 1992, the FDA's AA Pathway speeds up the approval of drugs for serious illnesses by relying on surrogate endpoints, such as tumor shrinkage, rather than waiting for complete clinical results, reducing time to market by an average of 3.9 y for cancer drugs Franco et al.,2023) [29]. AA allows early access based on surrogate endpoints but often relies on delayed or inconclusive confirmatory trials. Around 30–40% fail to confirm benefit, raising safety and ethical concerns. Regulatory reforms now aim to strengthen oversight, ensuring timely evidence generation and withdrawal of ineffective drugs to maintain trust and patient safety. Over the past decade, the FDA’s Accelerated Approval (AA) pathway has been granted to 103 drugs, accounting for approximately 15% of total approvals. Established in 1992, AA is designed to expedite the availability of treatments for serious or life-threatening conditions by allowing approval based on surrogate endpoints-intermediate markers believed to predict clinical benefit. For instance, tumor response rate or progression-free survival is often used in oncology instead of overall survival. While this approach reduces the time to market by an average of 3.9 y for cancer drugs (Franco et al., 2023) [6], surrogate endpoints can be imprecise predictors of long-term outcomes. In some cases, drugs approved on these grounds fail to confirm actual clinical benefit in post-marketing trials, raising concerns about the reliability and robustness of such early indicators. Expanding post-approval oversight and refining surrogate selection are essential to maintaining the balance between expedited access and patient safety.

Over the last ten years, the FDA's PR process has been the most common method for speeding up drug approvals, responsible for 55% of all expedited approvals, totaling 367 medications. In a study by Alqahtani et al.,(2015) [31] suggested PR designation expedites the FDA’s review timeline from the average 10 mo right to 6 mo, highlighting on drugs that offer substantial improvements in treatment of efficacy or safety. Research indicates that drugs receiving PR typically offer substantial improvements in health and are more frequently subject to safety updates after approval, highlighting both their beneficial potential and the need for rigorous monitoring [30].

While PR was the most common, the BTD, which began in 2012, facilitated the approval of 124 drugs over the last decade, representing 19% of total expedited approvals. This designation focuses on drugs offering a significant improvement over existing treatments for serious conditions. The BTD accelerates the approval process and offers extensive FDA support during drug development. Study by (Hotaki et al., 2023) [30] indicates that BT significantly shortens the clinical development timeline, often by 2–3 y, compared to non-breakthrough therapies. This expedited approval route is particularly helpful for new, innovative treatments, but like other fast-track methods, it requires careful monitoring after the drug is released to ensure its long-term effectiveness. Thus combination of pathways suggested in a study (Darrow, 2020) [32] indicates that combining different expedited pathways is most effective. Specifically, while FT speeds up development for severe illnesses, BT offers more support and quicker approvals, especially when paired with PR and AA, leading to the fastest and most efficient drug development and approval. The general trend in expedited drug approval programs reveals a strong move towards quicker approvals, fueled by scientific progress, especially in cancer and rare diseases. Regulatory changes have placed greater emphasis on rapidly delivering new treatments to patients, sometimes shortening the length of standard clinical trials. Multi-pathway drug approvals accelerate timelines and boost success rates but pose higher post-market safety risks, highlighting the need for robust surveillance and real-world evidence to ensure long-term patient safety.

Fig. 3: Type of expedited designation approved by FDA

Fig. 3 illustrated that expedited regulatory pathways have become essential tools in the evolving landscape of drug development, particularly for addressing serious or life-threatening conditions that require timely patient access to novel therapies. This study evaluates the frequency and utilization of the five major expedited drug approval programs used by the U. S. FDA over the past decade. These include PR, ODD, FTD, BTD, and AA. Fig. 3 presents the number and percentage of drug approvals granted under each program. Priority Review is the most commonly used designation, accounting for 55% of all expedited approvals. This reflects its role in accelerating access to therapies with significant clinical benefit. ODD, making up 42%, emphasizes the FDA’s strong commitment to incentivizing drug development for rare diseases, which typically lack effective treatments. FTD was granted in 32% of approvals, indicating its value in enabling more frequent communication with the FDA for serious conditions with unmet medical needs. BTD was used in 29% of cases, highlighting a shift toward highly innovative therapies supported by early evidence of substantial clinical improvement. In contrast, AA accounted for only 15% of approvals. While it enables earlier access to promising treatments based on surrogate endpoints, its use is tempered by the requirement for confirmatory post-marketing trials and increased regulatory oversight.

The study highlights that PR and ODD are the leading players in the landscape of expedited drug approvals, primarily due to their flexible requirements and significant incentives. AA, while still a crucial pathway, is applied more cautiously, reflecting a more rigorous approach. These findings provide valuable insights into the FDA’s regulatory strategy, emphasizing the delicate balance between ensuring rapid access to innovative therapies and maintaining safety standards in the evolving drug development process. However, it is important to note that FDA’s expedited approval programs do have several key limitations, which are outlined in table 2.

Table 3: FDA expedited programs for drug approvals (with key limitations)

| Program | Qualifying criteria | Approval timeline | Other features | Key limitations |

| AA | Serious or life-threatening disease; surrogate endpoint predicts benefit | Conditional approval; confirmatory trials required | Can be withdrawn if post-market trials fail | Heavy reliance on surrogate endpoints; post-marketing trials may be delayed or fail |

| FTD | Serious condition; meaningful benefit over existing therapies | Within 60 d | Earlier and more frequent communication with FDA | No guaranteed faster approval; requires sustained sponsor engagement |

| PR | Serious condition; major advantage over existing therapies | Review completed within 6 mo | Decided at time of marketing application (MA) submission | Shortened review may increase regulatory burden on FDA and sponsors |

| BT | Preliminary clinical evidence of substantial improvement over existing therapies | Within 60 d | Intensive guidance and senior FDA management involvement | Evidence often based on early-phase trials; may lead to approval before full validation |

| ODD | Treats rare diseases (affecting<200,000 people in the U. S.) | N/A | FDA provides trial design guidance; market exclusivity | Incentives may lead to high drug pricing; some drugs gain designation with limited evidence |

Finally, two illustrative case studies to highlight the differences in regulatory pathways. For example, Pembrolizumab (Keytruda), approved through multiple expedited pathways (BT, PR, and AA), demonstrated significantly reduced time-to-market for advanced melanoma. In contrast, Warfarin, a traditionally approved anticoagulant, underwent a standard and lengthy approval process despite its widespread clinical need. These contrasting examples will help underscore how regulatory flexibility can impact drug availability and patient outcomes.

CONCLUSION

In summary, the literature review shows that the FDA's expedited programs have greatly influenced how quickly drugs are developed and approved. In the last ten years, there's been a significant rise in applications and approvals for new drugs, particularly cancer treatments and biological medications. Fast Track speeds up drug development for serious illnesses, while BT offers thorough support throughout the entire development process. PR shortens the final review stage, and AA allows for trials using substitute markers of effectiveness. Furthermore, the data indicates that using PR, BTD, and AA together leads to the quickest drug development and approval, demonstrating how these pathways work together to get medications to patients faster. In essence, strategically combining these expedited approval pathways offers the best approach to quickly get new drugs to patients, meet critical medical needs, and promote the development of innovative treatments.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Phillips AT, Desai NR, Krumholz HM, Zou CX, Miller JE, Ross JS. Association of the FDA amendment act with trial registration publication and outcome reporting. Trials. 2017;18(1):333. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-2068-3, PMID 28720112.

Miller JE, Wilenzick M, Ritcey N, Ross JS, Mello MM. Measuring clinical trial transparency: an empirical analysis of newly approved drugs and large pharmaceutical companies. BMJ Open. 2017;7(12):e017917. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017917, PMID 29208616.

Wolford JE, Tewari KS. US FDA oncology drug approvals in 2014. Future Oncol. 2015;11(13):1931-45. doi: 10.2217/fon.15.106, PMID 26039742.

Vaggelas A, Seimetz D. Expediting drug development: FDA’s new regenerative medicine advanced therapy designation. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2019;53(3):364-73. doi: 10.1177/2168479018779373, PMID 29895180.

US Food and Drug Administration. Novel drug approvals for 2018. In: Silver Spring, MD: FDA; 2018 Jul 12. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs. [Last accessed on 11 Dec 2018].

Batta A, Kalra BS, Khirasaria R. Trends in FDA drug approvals over last 2 decades: an observational study. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2020;9(1):105-14. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_578_19, PMID 32110574.

Michaeli DT, Michaeli T, Albers S, Boch T, Michaeli JC. Special FDA designations for drug development: orphan fast track accelerated approval priority review and breakthrough therapy. Eur J Health Econ. 2024;25(6):979-97. doi: 10.1007/s10198-023-01639-x, PMID 37962724.

Puthumana J, Miller JE, Kim J, Ross JS. Availability of investigational medicines through the US food and drug administration’s expanded access and compassionate use programs. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(2):e180283. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0283, PMID 30646072.

Williams CT. Food and drug administration drug approval process: a history and overview. Nurs Clin North Am. 2016;51(1):1-11. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2015.10.007, PMID 26897420.

Kepplinger EE. FDA’s expedited approval mechanisms for new drug products. Biotechnol Law Rep. 2015;34(1):15-37. doi: 10.1089/blr.2015.9999, PMID 25713472.

G De La Torre B, Albericio F. The pharmaceutical industry in 2018. An analysis of FDA drug approvals from the perspective of molecules. Molecules. 2019;24(4):809. doi: 10.3390/molecules24040809, PMID 30813407.

Kepplinger EE. FDA’s expedited approval mechanisms for new drug products. Biotechnol Law Rep. 2015;34(1):15-37. doi: 10.1089/blr.2015.9999, PMID 25713472.

Cross S, Rho Y, Reddy H, Pepperrell T, Rodgers F, Osborne R. Who funded the research behind the Oxford-AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine? BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6(12):e007321. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-007321, PMID 34937701.

Cama J, Leszczynski R, Tang PK, Khalid A, Lok V, Dowson CG. To push or to pull? In a post-COVID world supporting and incentivizing antimicrobial drug development must become a governmental priority. ACS Infect Dis. 2021;7(8):2029-42. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.0c00681, PMID 33606496.

Ardal C, Rottingen JA, Opalska A, Van Hengel AJ, Larsen J. Pull incentives for antibacterial drug development: an analysis by the transatlantic task force on antimicrobial resistance. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(8):1378-82. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix526, PMID 29017240.

Alexander GC, Knopman DS, Emerson SS, Ovbiagele B, Kryscio RJ, Perlmutter JS. Revisiting FDA approval of aducanumab. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(9):769-71. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2110468, PMID 34320282.

Mandl KD, Kohane IS. Data citizenship under the 21st Century Cures Act. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(19):1781-3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1917640, PMID 32160449.

Hudson KL, Collins FS. The 21st century cures act a view from the NIH. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(2):111-3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1615745, PMID 27959585.

US Food and Drug Administration. Development and approval process. Silver Spring, MD: FDA Drugs; 2021. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs. [Last accessed on 13 Dec 2021].

Ballreich J, Bennet C, Moore TJ, Alexander GC. Medicare expenditures of atezolizumab for a withdrawn accelerated approved indication. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(11):1720-1. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.4757, PMID 34554196.

Mullard A. FDA drug approvals. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020;20:85-90.

Puthumana J, Wallach JD, Ross JS. Clinical trial evidence supporting FDA approval of drugs granted breakthrough therapy designation. JAMA. 2018;320(3):301-3. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.7619, PMID 30027239.

Brown DG, Wobst HJ. A decade of FDA-approved drugs (2010-2019): trends and future directions. J Med Chem. 2021;64(5):2312-38. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01516, PMID 33617254.

Kwok M, Foster T, Steinberg M. Expedited programs for serious conditions: an update on breakthrough therapy designation. Clin Ther. 2015;37(9):2104-20. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2015.07.011, PMID 26297571.

Ribeiro TB, Buss L, Wayant C, Nobre MR. Comparison of FDA accelerated vs regular pathway approvals for lung cancer treatments between 2006 and 2018. PLOS One. 2020;15(7):e0236345. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0236345, PMID 32706800.

Michaeli DT, Michaeli T. Breakthrough therapy cancer drugs and indications with FDA approval: development time innovation trials clinical benefit, epidemiology and price. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2024;22(4):e237110. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2023.7110, PMID 38648855.

Shepshelovich D, Tibau A, Goldvaser H, Molto C, Ocana A, Seruga B. Postmarketing modifications of drug labels for cancer drugs approved by the US food and Drug Administration between 2006 and 2016 with and without supporting randomized controlled trials. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(18):1798-804. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.5593, PMID 29641296.

Liberti L, Bujar M, Breckenridge A, Hoekman J, McAuslane N, Stolk P. FDA facilitated regulatory pathways: visualizing their characteristics, development and authorization timelines. Front Pharmacol. 2017 Apr 3;8:161. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00161, PMID 28420989.

Franco P, Jain R, Rosenkrands Lange E, Hey C, Koban MU. Regulatory pathways supporting expedited drug development and approval in ICH member countries. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2023;57(3):484-514. doi: 10.1007/s43441-022-00480-3, PMID 36463352.

Hotaki LT, Shrestha A, Bennett MP, Valdes IL, Lee SH, Wang Y. Comparative expedited regulatory programs of U.S food & Drug Administration and Project Orbis Partners. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2023;57(4):875-85. doi: 10.1007/s43441-023-00522-4, PMID 37072651.

Alqahtani S, Seoane Vazquez E, Rodriguez Monguio R, Eguale T. Priority review drugs approved by the FDA and the EMA: time for international regulatory harmonization of pharmaceuticals? Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2015;24(7):709-15. doi: 10.1002/pds.3793, PMID 26013294.

Darrow JJ, Avorn J, Kesselheim AS. FDA approval and regulation of pharmaceuticals, 1983-2018. JAMA. 2020;323(2):164-76. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.20288, PMID 31935033.